Abstract

Although deep reinforcement learning has achieved great success in the field of autonomous driving, it still faces technical obstacles, such as balancing safety and efficiency in complex driving environments. This paper proposes a deep reinforcement learning multi-vehicle safety enhancement framework that integrates a safety barrier function (SBF-DRL). SBF-DRL first provides independent monitoring assurance for each autonomous vehicle through redundant functions and maintains safety in local vehicles to ensure the safety of the entire multi-autonomous vehicle driving system. Secondly, combining the safety barrier function constraints and the deep reinforcement learning algorithm, a meta-control policy using Markov Decision Process modeling is proposed to provide a safe logic switching assurance mechanism. The experimental results show that SBF-DRL’s collision rate is controlled below 3% in various driving scenarios, which is far lower than other baseline algorithms, and achieves a more effective trade-off between safety and efficiency.

1. Introduction

In recent years, with the improvement of communication technology and the enhancement of on-board computing capabilities, there has been an increasing focus on collaborative control among multiple traffic participants, or using the experience of other participants to optimize the performance of one’s own vehicle. With the development of the field of machine learning (ML), an increasing number of ML algorithms are being applied to all stages of environmental perception, behavioral decision-making, and control execution of autonomous multi-vehicle systems, especially deep reinforcement learning (DRL) [1,2] algorithms. Behavioral decision-making plays a vital role in realizing high-level autonomous vehicle actions. Its main function is to select appropriate actions in a limited action space to achieve the desired expected position, speed, lane, etc., based on upstream environmental information [3]. At present, the DRL algorithm has been widely used in research on the autonomous decision-making of autonomous vehicles due to its outstanding advantages in processing complex tasks, resulting in a remarkable performance. However, the DRL algorithm mainly learns based on a large amount of data. When the data are insufficient, the learning process of the decision-making algorithm model is unreasonable, and the model decisions often show a high uncertainty, leading to unpredictable safety issues [2,4].

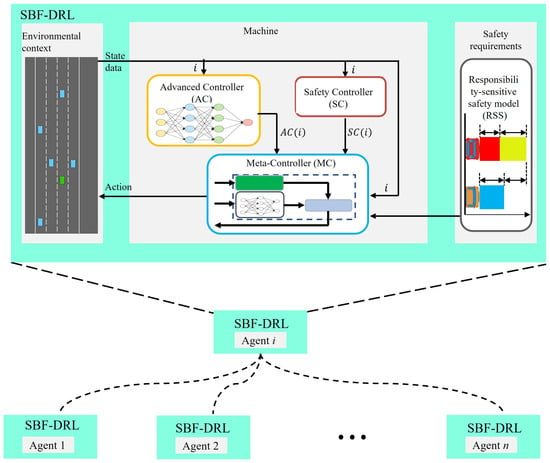

To solve the above problems, this paper integrates the safety barrier function deep reinforcement learning multi-vehicle safety enhancement framework (SBF-DRL), which is a new runtime assurance technology that provides safety assurance for multi-autonomous vehicles. SBF-DRL consists of a deep neural network-based Advanced Controller (AC), a Recoverable Safety Controller (SC), and a meta-controller (MC) that performs switching between the AC and SC. When the MC is triggered, the system will deploy the SC for control. The SC is designed to be safe but is likely to undermine the operational goals of the driving system, so the MC must balance safety and efficiency. We use the Markov Decision Process (MDP) framework to design MC and use DRL to solve it, ensuring safety policy output by utilizing barrier function safety constraints, that is, monitoring potential realistic risks through the identification of trigger conditions, insufficient functional states, etc., and providing safety assurance through authority transfer without excessively sacrificing performance. This paper contributes as follows:

- We bypass the formal verification of AC (black boxes) by introducing runtime safety assurance as a mechanism to ensure safety.

- We design MC through MDP, combining safety constraints and DRL optimization policies to achieve a more effective trade-off between safety and efficiency.

- We tested and evaluated SBF-DRL in a driving task using two environmental states: a single autonomous vehicle and multiple autonomous vehicles.

2. Related Work

Currently, DRL technology [1] has gradually penetrated into the research frontier of autonomous driving behavior decision-making. In addition to basic tasks such as controller optimization, path planning, trajectory optimization, motion planning, and dynamic path planning, it can also formulate advanced driving policies in complex scenarios, which cover driving tasks such as lane keeping [5,6], lane changing [7], or overtaking [8] in various driving scenarios from highways [9] to ramps [10], intersections, or roundabouts [2]. El Sallab et al. [5] proposed a lane keeping policy for autonomous driving based on DRL. This policy uses a convolutional neural network to extract features from sensor information and discretize action information. The policy is optimized based on the Deep Q network (DQN) in the TORCS simulation environment. Perot et al. [6] optimized the autonomous driving lane keeping policy based on the asynchronous advantage Actor–Critic algorithm. This policy uses images as a state input, outputs continuous control actions, and conducts experimental verification in the TORCS multi-scenario simulation environment. Wang et al. [7] proposed a lane changing policy for autonomous driving based on DQN, which uses physical information as a state representation, outputs continuous action behaviors, and conducts experimental tests in a highway environment. Foerster et al. [11] proposed a method using centralized critics to estimate the asynchronous advantage policy gradient in multi-agent reinforcement learning. By using asynchronous baselines to solve the challenge of multi-agent credit allocation, the learning efficiency and performance of the centralized controller were significantly improved. Desjardins et al. [12] proposed a multi-vehicle decision-making method based on a centralized reinforcement learning algorithm, which enhances the safety and driving efficiency of autonomous driving during adaptive cruises by paying attention to the vehicle’s longitudinal safety distance. Chen et al. [13] used a distributed multi-intelligence reinforcement learning algorithm for collaborative decision-making between two vehicles. They improved the multi-intelligence reinforcement learning algorithm by introducing fairness measurement and other technologies, and significantly improved the collaboration between vehicles while maintaining efficient driving in various random dynamic highway environments. Santini et al. [14] proposed a vehicle formation longitudinal control system based on distributed consensus, which not only improves system stability and safety, but also greatly simplifies the complexity of the overall system design. Fabiani et al. [15] proposed a distributed hybrid decision-making framework based on game theory and found an equilibrium solution as the optimal decision for autonomous vehicles given safety constraints. Although DRL has achieved fruitful research results in autonomous single-vehicle or multi-vehicle behavioral decision-making by virtue of the powerful function approximation capabilities of neural networks, the unexplainability or uncertainty caused by its black-box characteristics still brings serious safety issues to autonomous driving decision-making.

One of the most prominent challenges of autonomous decision-making methods for autonomous driving based on DRL is the unexplainability or uncertainty caused by its black-box characteristics, which raises human concerns about safety [2]. Therefore, a series of safety-enhanced DRL methods have been proposed to solve the autonomous driving decision-making problem. Ye et al. [16] used a proximal policy optimization algorithm to optimize the policy and added a penalty term to the reward function to ensure the minimum safe distance. Hu et al. [17] proposed a reward function that comprehensively considers the impact of the rear vehicle target type, safety gap, and vehicle roll stability on rear-end collisions to improve the safety of DRL decision-making. Tang et al. [18] designed two driving policies, aggressive and conservative, to study the balance between vehicle safety and efficiency performance by adjusting the weight of the reward function. Kamran et al. [19] proposed a distributed DRL adaptive safety verification policy method to verify the safety of operations through active safety verification methods, while encouraging policies to minimize safety interference and produce more comfortable behaviors. Jafari et al. [20] proposed a hierarchical autonomous driving trajectory planning policy, which first uses a logical decision maker based on a decision tree to extract the environmental state and then uses DRL to generate strategic intentions such as turning, following, and passing intersections. Finally, the rule-based safety checker integrates DRL and rule-based methods to enhance the safety of decisions. Our recent work [21], RTA-IR, leverages imitation learning to optimize AC (reinforcement learning agent) policies through expert demonstration data and provides safety oversight based on a responsibility-sensitive safety (RSS) [22] model as a safety checker. Hwang et al. [23] and Yang et al. [24] studied similar works, adopting finite state machines as safety checkers. The research work of this paper is similar to external checkers [20,21,22,23,24] for safety enhancement. Checkers are usually used to filter unsafe behaviors based on learning policies in driving scenarios, thereby improving safety. Compared with using rule-based methods such as finite state machines as policy safety assessment, this paper uses a deep reinforcement learning method that integrates safety constraints to train meta-control policies to represent the logical relationship between policy performance estimation and safety policy responses in dangerous states, so as to better balance driving efficiency and safety.

3. SBF-DRL Framework System Design

In this paper, we propose a deep reinforcement learning multi-vehicle safety enhancement framework incorporating a safety barrier function (SBF-DRL). The SBF-DRL framework shown in Figure 1 is a necessary extension of our previous work [21,25], including extending its application scope to multi-vehicle autonomous driving systems. In SBF-DRL, for each autonomous vehicle, there is an independent runtime assurance framework which consists of an Advanced Controller (AC), a Safety Controller (SC), and a meta-controller (MC) that monitors the system’s operational behavior and enables switching between the AC and SC. The DRL-based AC is expected to perform driving tasks effectively and continuously update and optimize its own policy, but its decision-making is uncertain. SC is a highly reliable strategy that maintains driving stability in a known domain of the vehicle state space. To achieve this, it should be accepted that SC may not be efficient when performing driving tasks. MC needs to evaluate the security of the vehicle state space and select control commands between AC and SC based on the evaluation results. SBF-DRL allows each autonomous vehicle to independently switch between its control modes, and at any given time some autonomous vehicles may be operating in the AC control, while other autonomous vehicles operate in SC mode. Another key issue to address is determining how to decide when to switch from AC to SC and when to return control to AC while balancing the tradeoffs between safety and efficiency.

Figure 1.

The structure of SBF-DRL.

There is a trade-off between safety and efficiency: a very conservative MC will switch to SC too often, which will lead to a very safe but inefficient driving policy. In contrast, an MC that fails to recognize potentially hazardous conditions may be effective in most situations but may lead to hazards occurring. In previous work, we evaluated vehicle safety guidelines and validated controller switching logic using domain expertise and ergonomics such as Safe Field Models (SF) [26] or RSS, which are not black boxes, leading to safety and allowing for easy verification and interpretation. While the above models show good performance, designing the switching module in an automated driving runtime assurance framework is challenging and remains at the heart of the problem.

In SBF-DRL, for each independent runtime assurance framework, the MC continuously monitors the status of the system and switches control to SC when necessary; otherwise, it will cause driving risks. The MC can also switch control back to AC while ensuring safety to minimize the loss of efficiency. For each runtime assurance framework, we define AC as a black box that performs driving tasks efficiently. Regarding the AC and the design or implementation, we will not describe it in detail here; its design principle is similar to that of the graph attention reinforcement learning controller in the work [25], which uses an attention mechanism to preprocess the joint state of the vehicle, provides it as an input to the RL intelligences, and outputs the optimal policy in the current state. It is often easier to design SCs compared to ACs, which are designed to be simple and secure but often cannot or inefficiently perform the tasks designed for ACs. For example, the work described in [25] involves autonomous vehicles with SCs, where the controller decelerates at an appropriate deceleration rate to avoid driving risks by attenuating kinetic energy. In the following sections, we focus on describing how the MC is determined to decide when to switch from the AC to the SC and when to return control to the AC while balancing the trade-off between safety and efficiency.

4. Meta-Controller

In the SBF-DRL framework, we design the MC not only to ensure safety through forward switching (FSC, switching from AC to SC), but also to minimize efficiency loss through reverse switching (RSC, switching from SC to high AC). Another advantage of RSC is that it reduces the burden of SC implementation performance and makes SC design easier and more secure. This section first reviews the Markov Decision Process (MDP) framework to facilitate its use in this problem. We then describe in detail the design and implementation process of how to use Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL) algorithms as a method for designing MC switching policies.

4.1. Markovian Decision Process Modeling

MDP has been used to model autonomous systems such as self-driving cars [27] and unmanned aircraft systems [28]. In this chapter’s work, we use the MDP framework to model how the policy decisions of autonomous vehicles are affected when the MC is coupled with the AC and SC.

In the SBF-DRL framework, for each runtime assurance framework, we model the behavioral planning of MC-equipped autonomous vehicles by defining the following MDP: , where the elements are defined as follows.

- The state space represents a vector of environment and vehicle states. The MDP state space consists of a concatenated list of state features of the observed vehicles, including autonomous vehicles and nearby neighboring vehicles. For each autonomous vehicle, its state is modeled as a 5-tuple list of features:where presence is a 0–1 variable that indicates if the vehicle is included in the feature list (the ego vehicle is always included; a surrounding vehicle may be included if it falls within a user-defined perception distance, subject to the constraint of the total number of nearby vehicles ); and are its and coordinates, respectively; and are its speeds in the and directions, respectively. We set in our experiments, which is the default value in highway-env. Therefore, the initial state input of the AC for each autonomous vehicle has 5 5 = 25 dimensions to encode the overall system state of the five vehicles during training and validation.

- Action space determines whether the SC or AC is kept in control by FSC or RSC. FSC corresponds to “switching to SC control” in the action space; that is, when the MC detects that the current state does not meet the safety constraints, it triggers the transfer of control from AC to SC. RSC corresponds to “switching back to AC control” in the action space; that is, when the MC verifies that the current state meets the safe recovery conditions, the transfer of control rights from SC to AC is triggered.

- is the transfer probability function of taking action in one state to obtain the next state , .

- denotes the discount factor.

- Reward is the reward received corresponding to a state transfer. Achieving the desired policy behavior is guided by rewards.

In this model, the MC is considered as an agent, while the state corresponds to the position, speed, and other relevant information of the autonomous and neighboring vehicles, and the action corresponds to whether or not to execute the control output using AC or SC. The agent receives a large negative reward for a collision with the autonomous vehicle and a smaller negative reward for switching control to the SC when it is not required. This reward structure is designed to severely penalize autonomous vehicles for generating collisions while discouraging unnecessary deployment of the SC. The rewards at each step are weighted by a discount factor so that current rewards are more valuable than future rewards.

Policy is a function that determines which action to perform in each state . The utility of following a policy from the state is denoted and is often referred to as the value function. Solving the MDP corresponds to formulating a policy that maximizes the expected utility [28]:

For those MDPs with discrete and small state and action spaces, where the transfer dynamics are known and have a closed form, they can be solved accurately using techniques derived from dynamic programming, such as policy iteration algorithms. However, the state space of the multi-autonomous vehicle behavior planning problem studied and analyzed in this chapter is high-dimensional because it includes all the variables needed to simulate vehicle dynamics, sensor readings, and environmental conditions (lanes), and the transfer model is very complex. Furthermore, we consider the AC to be a black box. Therefore, we must operate under the assumption that the transfer probability function is unknown and that we do not have access to it. However, we do have access to the simulator, and by providing state and action and obtaining the next state and the associated reward we can query the simulator for the experience trajectory . In this case, we can learn the policy from the experience of the DRL.

4.2. Iterative Generation of Secure Deep Reinforcement Learning Controllers Based on Barrier Functions

In our context, we have an AC policy and an SC policy . The goal is to learn the optimal policy that switches control back and forth, and , when needed to provide a strong safety assurance while minimizing the loss of efficiency. It follows that the system controller policy has the following form:

We use the DRL algorithm to learn policy . The agent needs to learn to choose actions that maximize their long-term cumulative rewards by observing the outcomes of their actions in the form of state transitions and rewards. Recently, DRLs have been successfully applied in many domains thanks to the powerful function approximation capabilities of neural networks (DNNs), but they suffer from a fundamental drawback in our setting: they are treated as black boxes. Given the difficulty of formally verifying the behavior of DNNs [28], it is unlikely that we will be able to implement the switching mechanism in the SBF-DRL architecture through DRL algorithms alone. We propose a deep reinforcement learning controller iterative framework algorithm with barrier function safety constraints for designing our MC architecture. As shown in Figure 2, the algorithm constructs a cyclic iterative verification framework between the learner and the verifier. The learner uses DRL to train the controller policy and passes the trained policy to the validator, and the validator verifies the safety of the trained DRL controller policy via the barrier function (BF).

Figure 2.

Safety DRL controller generation framework.

- (1)

- Learner component

This subsection will focus on the learner component in Figure 2 and show how to generate secure DNN controllers using the Double DQN (DDQN) [29] algorithm. DDQN is a classical model-free DRL algorithm that combines DNNs and Q-learning. DDQN incorporates ideas from DQN and empirical replay mechanisms in its design, which breaks the correlation between samples, and the training samples have enough independence, thus better reflecting the effect of reinforcement learning. Meanwhile, DDQN extends DQN. DDQN is mostly the same as DQN, and only one step is different; that is, in the process of choosing , DQN always chooses the maximum output value of the Target Q network. This design approach makes the over-estimation of DQN well controlled, and more stable and smaller variance policies can be learned. In the DDQN algorithm, the main network is divided into two parts: the Q network and the Target Q network. Where the Q network is used to predict the estimated Q value and the Target Q network is used to predict the realistic Q value, the two networks have the same structure with different parameters. The DDQN training updates the Q network and synchronizes the Q network parameters to the Target Q network every episodes; this method can make the training more stable and accelerate the speed of convergence. The equation for updating the value function of DDQN is as follows:

where denotes the main Q-network and denotes the target Q-network. is the action with the highest Q-value in the next state obtained from the main Q-network, and denotes the learning rate.

Our goal is to design a reasonable reward function that achieves the goal of safety controller synthesis through a reinforcement learning DDQN algorithm. The task of safety controller synthesis is to synthesize a DNN controller such that the trajectory of each autonomous vehicle cannot evolve to the unsafe state region . We first define the reward function initially as follows:

In our reward function design, there is no cost associated with operating the vehicle under safe conditions, an cost associated with using the SC control vehicle system, and a fixed negative cost associated with exiting the safe set . The cost associated with using the SC control vehicle system is a fixed negative cost. We can control the trade-off between safety and efficiency by assigning different values to . Larger values of will hinder the deployment of . This allows us to adjust the behavior of the meta-controller and later analyze whether it always dominates the baseline meta-controller.

- (2)

- Validator component

The secure DRL controller approach proposed in this paper uses iterative generation, i.e., the generated controller is continuously corrected by the safety guidance of the BF based on the RSS model [22], and the action reset of the DRL controller is performed to provide safety for the vehicle if necessary. Therefore, we also need to characterize the RSS-based BF.

The RSS model formalizes the human concept of safe driving into a logically demonstrable and verifiable model. Definitions of “safe distance”, “hazardous situation and blame time”, and “appropriate response” ensure that self-driving cars will always make safe decisions and will do everything possible to avoid being involved in unsafe situations caused by other factors. The use of RSS is advocated in the current effort to realize the IEEE 2846 standard [30].

RSS provides a strict mathematical form of safety rules for the safety assurance of autonomous driving, and Definition 1 relates to Rule 1, “Do not hit the car in front of you (longitudinal distance)”, in RSS [22].

Definition 1

(Safe distance—same direction). A longitudinal distance between a rear vehicle that drives behind another front vehicle , where both vehicles are driving in the same direction, is safe with respect to a reaction time if, for any braking of at most performed by , if will accelerate by at most during the reaction time , and from there on will brake by at least until a full stop, it will not collide with .

Lemma 1.

Let be the vehicle behind in the longitudinal direction. , , , and are the same as in Definition 1. Let and be the longitudinal speeds of the car. Then, the minimum safe longitudinal distance between the foremost point of and the last point of is as follows:

Lemma 1 calculates the safe distance as a function of the velocities of and and the parameters in Definition 1.

As the trusted backup controller of the system, SC’s core design goal is to provide deterministic safety guarantees in dangerous situations while minimizing the impact on driving efficiency. The design of the SC should follow the following operations to meet RSS requirements: (1) After detecting a dangerous state, the autonomous vehicle will accelerate at most within the reaction time . After the reaction time , it will start braking with an acceleration of until it comes to a complete stop. After that, any non-positive acceleration is allowed. (2) The acceleration of the vehicle in front of the autonomous vehicle must be at least until a complete stop, after which any non-negative acceleration is allowed. Based on the above rules, the SC we design controls the autonomous vehicle to brake by decelerating at least until the vehicle comes to a complete stop, or, more likely, when the current inter-vehicle distance increases above () and an RSC operation is performed to return control to AC—whichever comes first.

To ensure safe decision-making by the learner, we use BF to guide the learner in policy optimization. The current environment condition is evaluated by the minimum safe distance (calculated by Equation (6)) as BF. Ensure that the SBF-DRL’s behavioral planning is within the safe range. The validator component monitors and guards the learner’s policy by calculating BF at each control iteration cycle, and for each autonomous vehicle the learner policy action is reset (controlled by the SC system) as soon as the current inter-vehicle distance does not satisfy the BF safety requirement (). In this process, the learner DRL policy still obtains training samples from the experience pool to continue training, except that the output action is not output as a policy, and the samples generated by the execution are not counted in the experience pool. Meanwhile, the learner’s current policy behavior will be punished, a negative feedback reward will be given, and this sample will be added to the experience pool and the reward function will be updated as described in Equation (7). Until the current distance between vehicles is detected to meet BF safety requirements (), control will be taken over by AC.

Algorithm 1 shows the pseudo-code used to train the iterative generation framework for secure deep reinforcement learning controllers with barrier functions.

| Algorithm 1: Barrier Functions Guides DDQN to Train MC Agents |

| 1: Initialize: ; empty empirical pool ; 2: for episode = 1, 2, …, M do 3: for t = 0, 1, …, T do 4: Get the current state and calculate the BF in the current state; 5: Select an action in the set of actions or policy; 6: if meets BF safety requirements then 7: ; 8: to ; 9: else 10: ; 11: to ; 12: end 13: Randomly sample small batches of experience from ; 14: Update and via Equation (4); 15: end 16: end |

5. Experiment and Analysis

5.1. Experimental Setup

We use the open source gym-based simulator highway-env [31] for our experiments. All experiments are implemented based on PyTorch 1.12.1, which provides flexible support for the construction of graph attention networks, the implementation of DDQN algorithms, and the processing of large-scale experimental data. In the experiments, we assign different numbers of environmental vehicles in different numbers of autonomous vehicle driving environments and have simulated autonomous vehicles sharing road scenarios with human-driven vehicles to increase the complexity of the environment and to test the adaptive and generalization capabilities of autonomous vehicles. As shown in Figure 3, we trained and evaluated SBF-DRL in a highway driving task environment, where the highway environment consists of four one-way lanes in one direction, with green squares representing autonomous vehicles, blue squares representing environmental vehicles, and all vehicles driving from left to right. The task of the self-driving vehicle is to travel as fast as possible without colliding with other vehicles. Under the execution of the highway environment task, the episode ends when any of the autonomous vehicles collide with another vehicle (autonomous or environment) or when the maximum episode length is reached, whichever comes first. The ambient vehicle is designed according to the Vehicle Kinematics Cycling Model, with lateral control by low-level steering to track the target path, longitudinal control using a smart driver model, and a random initialization of position and speed.

Figure 3.

The highway simulation environment.

We set in our experiments the number of autonomous vehicles in the environment task to be n and the number of ambient vehicles to be m. For each autonomous vehicle, its MDP state space S consists of a concatenation of a list of state features of N observed vehicles, including the current autonomous vehicle and N-1 nearby surrounding vehicles, with the state of each vehicle modeled as a list of features in a 5-tuple (Equation (1)). We set , which is the default value in the highway environment, in our experiments. Thus, during training and validation, the AC and MC state inputs of each autonomous vehicle have 5 × 5 = 25 dimensions to encode the aggregated system states of the five vehicles.

In the work of this chapter, our AC and MC are trained in a vehicle density environment with n = 1 and m = 49. In the validation phase, multiple autonomous vehicles share the above AC and MC model parameters and make decisions based on their current state. Each autonomous vehicle AC model has an action space of size 5 to choose among 5 possible driving actions, , and the MC model has an action space of size 2 to keep SC or AC under control via FSC or RSC. Of particular note, we set an environmental reward function for driving demands and criteria for training the AC policy as well as for evaluating individual algorithmic model performance metrics as a validation below, and the MC training reward function is shown in Equation (7). The reward function is of the following form:

At each time step, is the (negative) reward when the autonomous vehicle collides with another vehicle (which ends the current turn); is the (positive) reward when the autonomous vehicle is traveling in the rightmost lane; and is the (positive) reward proportional to the speed of the autonomous vehicle, defined as follows:

equals , and the current speed when the autonomous vehicle is traveling at its maximum speed and 0 when it is traveling at its minimum speed, , with a linear interpolation between the two. Evaluating the DRL agent reward function definition in highway environments, .

In SBF-DRL, the AC and MC training networks have the same neural network architecture except for the output layer: the input layer has 25 neurons to encode the 25-dimensional input shown in Equation (1), followed by the attention network layer, and then 2 hidden layers with 256 neurons each. The MC intelligences have 2 neurons in their output layer, which corresponds to an action space of their size 2. The AC intelligences have 5 neurons in their output layer, corresponding to an action space of their size 5. We use the Adam optimizer with a learning rate of 0.001 and a minimum batch size of 128. The AC is trained in the environment for M = 4000 episodes, with a speed range of [0, 24] m/s for the autonomous vehicle and a maximum round length of T = 40. The MC is trained in the environment for M = 8000 episodes, with a maximum round length of T = 40. In the reward function setup parameter of MC we define and . The RSS parameters in Equation (6) are set as follows: , , , and .

For multi-vehicle dynamic driving tasks under different scene conditions, the following algorithms were compared in the experiment:

- MDDQN: This policy uses the most commonly used model-free DRL algorithm. DDQN [29] to train based on the reward function . DDQN is an offline policy algorithm for discrete action spaces. This policy did not adopt MC safety constraints when testing.

- GAT-MDDQN: This policy uses the DDQN algorithm with a graph attention mechanism state representation network to be trained based on and as an AC. This policy does not adopt MC safety constraints when testing.

- GAT-MDDQN-MC: This policy uses GAT-MADDQN for experimental testing and uses MC for safety assurance, which is the SBF-DRL policy proposed in this chapter. The overall structure is shown in Figure 1.

For a fair comparison, the DDQN algorithm based on the same hyperparameters among the three policy algorithms of MDDQN, GAT-MDDQN, and GAT-MDDQN-MC is trained. The network structure consists of a Q network and a target Q network with the same structure. In the following test experiments, each policy environment was run for 1000 rounds. We recorded the following indicators to measure the driving performance of each model algorithm:

- Cumul. Reward: Cumulative reward per episode.

- Episode Avg Speed: Average speed of the ego vehicle in each episode.

- Episode Length: Number of time steps of each episode.

- Collision Rate: Proportion of episodes that end with a collision.

- Distance Traveled: Total distance that the ego vehicle travels in each episode in the Highway environment.

These metrics were further averaged over 1000 episodes during the test period and are reported in Table 1, Table 2 and Table 3.

Table 1.

Switching logic performance metrics based on various methods. (Bold font indicates the best performing metrics).

Table 2.

Performance metrics of each algorithm in different autonomous vehicle density driving environments. (Bold font indicates the best performing metrics).

Table 3.

Performance metrics of each algorithm under different complexity driving environments. (Bold font indicates the best performing metrics).

The metric “Avg Cumul. Reward” is the comprehensive metric that measures the overall performance according to the reward function defined in Equation (8); the metrics “Avg Collision Rate” and “Avg Episode Length” mainly measure the level of safety; the metric “Avg Episode Avg Speed” mainly measures the level of efficiency; the metric “Avg Distance Traveled” for the highway environment, equal to the product of “Avg Episode Avg Speed” and “Avg Episode Length”, serves as a more balanced metric. In the data tests below, the lower the “Collision Rate” the better, and the higher the better for all other indicators.

5.2. Experimental Results and Analysis

We compare several design approaches for safety specification and switching logic for runtime assurance frameworks, including the policy method (GAT-MDDQN-SR) based on safety rules (GAT-MDDQN-SR) [24], the DRL policy method (GAT-MDDQN-RL) used in the work [28], the SF Model (GAT-MDDQN-SF) used in our previous work [25], the RSS model method (GAT-MDDQN-RSS) used in the work [21], and the MC based on BF and DRL constraints (GAT-MDDQN-MC) used in this paper, and their performance was verified in the highway driving environment of n = 20, m = 30.

Table 1 shows the average performance metrics of the safety specification and switching logic designed by the above methods over 1000 episodes (bold entries indicate the best performers), and Figure 4 shows the average “Cumul. Reward” visualization graph over 1000 episodes. From the “Episode Avg Speed” metric, the GAT-MDDQN-RL achieves a high level of efficiency, highlighting the natural advantages of RL in optimizing multi-vehicle traffic efficiency—reducing ineffective deceleration by maximizing immediate rewards. However, the safety index has obvious shortcomings, exposing the core problem of traditional RL single reward functions as having difficulty balancing “efficiency–safety”, and it is easy to ignore potential collision risks in multi-vehicle dynamic interactions due to short-term efficiency pursuit. The methods GAT-MDDQN-SF, GAT-MDDQN-RSS, and GAT-MDDQN-MC all achieve a high level of safety. Among them, GAT-MDDQN-MC uses an MC based on BF and DRL as the safety switching logic. While maintaining a high safety, other performance indicators are also superior. The key lies in BF’s prediction and classification of vehicle interaction behaviors, which provides accurate decision-making guidance for DRL and solves the “safety–efficiency trade-off” problem. It is more in line with the needs of real autonomous driving scenarios and provides an effective technical path for the safety–efficiency collaborative optimization of multi-autonomous vehicle decision-making.

Figure 4.

Cumulative reward performance metrics based on various switching logic design methods.

In order to be more suitable for the training environment of the algorithm, the total number of vehicles in the environment was set to 50, and a fusion experiment was conducted by changing the number of two types of vehicles to evaluate the overall performance of GAT-MDDQN-MC, GAT-MDDQN, and MDDQN. The experiment was tested and verified using the above policy for 1000 episodes, and its starting state was randomly initialized in each experiment. Table 2 shows the average performance indicators of each policy algorithm. The experimental results in Table 2 show the performance differences between GAT-MDDQN-MC, GAT-MDDQN, and MDDQN. The specific analysis shows that GAT-MDDQN performs best when considering the Episode Avg Speed. Although GAT-MDDQN performs well in terms of speed, its safety still needs to be improved due to the lack of safety assurance constraints to ensure safety when interacting closely with other vehicles, and this problem is more serious for the MDDQN algorithm. In contrast, GAT-MDDQN-MC has the lowest collision rate in each set of tests and also has obvious advantages in other performance indicators. As the number of autonomous vehicles increases, the Episode Avg Speed indicators of each policy have significantly improved. This is because, as the proportion of autonomous vehicles increases, the overall vehicle intelligence is improved, and driving efficiency will be greatly improved. In contrast, the MDDQN algorithm fails to understand the relationship between vehicles well, resulting in a significant increase in the collision rate. The performance indicators of GAT-MDDQN-MC are always maintained in a stable state, which can reduce the loss of efficiency as much as possible under a strong safety assurance. Therefore, it can be concluded that GAT-MDDQN-MC achieves the highest level of safety and is able to trade off safety and efficiency more effectively. This shows that using safety assurance for decision-making in regular traffic scenarios has a safer performance than GAT-MDDQN based only on learning.

In order to further verify the performance advantages of GAT-MDDQN-MC, 1000 episodes of verification tests were conducted on the three policies of GAT-MDDQN-MC, GAT-MDDQN, and MDDQN in a highway environment with 20 autonomous vehicles based on the allocation of different numbers of environmental vehicles. As the number of vehicles in the environment increases, the driving environment will become more complex. Table 3 shows the average performance indicators of each model in different complex driving environments. From the analysis of the experimental results in Table 3, as the complexity of the environment increases, each performance index of GAT-MDDQN-MC decreases slightly, and this decrease is more serious for GAT-MDDQN and MDDQN. This can be partly attributed to the environment in which safe distances between vehicles are shrinking, resulting in a higher-than-expected number of collisions. Although there are certain similarities in the performance degradation of the three policies GAT-MDDQN-MC, GAT-MDDQN, and MDDQN, GAT-MDDQN-MC exhibits a lower collision rate and longer distance traveled than GAT-MDDQN and MDDQN, which means that it is more stable and reliable when dealing with complex environments. In the test, although the average Cumul. Reward of all policies showed a downward trend, GAT-MDDQN-MC still performed the best, which shows that GAT-MDDQN-MC is still able to maintain its excellent comprehensive performance even in the face of complex driving environments. The experimental results show that GAT-MDDQN-MC has a strong robustness in the face of changing traffic environments and can maximize driving efficiency while ensuring safety.

6. Conclusions

This paper aims at DRL to solve the safety issues caused by multi-vehicle behavior decision-making. A deep reinforcement learning multi-vehicle safety enhancement framework that integrates safety barrier functions (SBF-DRL) is proposed. SBF-DRL uses redundant functional modules to provide an independent runtime assurance framework for each autonomous vehicle and maintains safety in local vehicles to ensure the safety of the entire single- and multi-autonomous vehicle driving system. We then demonstrate a new approach to safety specification and switching logic by designing a meta-controller aligned with human values, modeling its behavioral planning using an MDP framework and solving it using an iterative framework algorithm for deep reinforcement learning controllers with safety constraints on barrier functions. Finally, we conducted experimental verification in a highway environment. The experimental results show that the algorithm designed based on the SBF-DRL framework can control the collision rate below 3% while maintaining a high efficiency in various traffic scenarios, which is far lower than other baseline algorithms, achieving a more effective trade-off between safety and efficiency.

In the future, we can further explore the deep integration of the SBF-DRL framework with the human-in-the-loop control system and optimize the human value alignment accuracy of the meta-controller by building a human–computer interaction decision-making feedback mechanism. At the same time, we can study the adaptive improvement of the framework for multi-heterogeneous vehicle collaboration in complex urban road networks for large-scale real-world implementation scenarios to further verify its safety–efficiency balance capability and engineering implementation potential in a wider range of traffic environments.

Author Contributions

Y.P. contributed to the conceptualization, data curation, methodology, software, validation, visualization, writing the original draft, writing the review, and editing. W.Y. and F.M. contributed to the data curation, formal analysis, and investigation. W.H. contributed to the funding acquisition, resources, supervision, writing the review, and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported in part by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant No. 62103060.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. Since the data of subsequent research work are not made public for the time being.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Mnih, V.; Kavukcuoglu, K.; Silver, D.; Rusu, A.A.; Veness, J.; Bellemare, M.G.; Graves, A.; Riedmiller, M.; Fidjeland, A.K.; Ostrovski, G.; et al. Human-level control through deep reinforcement learning. Nature 2015, 518, 529–533. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J.; Huang, C.; Huang, H.; Lv, C.; Wang, Y.; Wang, F.-Y. Recent advances in reinforcement learning-based autonomous driving behavior planning: A survey. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2024, 164, 104654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Shao, W.; Sun, C.; Yang, K.; Cao, D.; Li, J. A Survey on an Emerging Safety Challenge for Autonomous Vehicles: Safety of the Intended Functionality. Engineering 2024, 33, 17–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigorescu, S.; Trasnea, B.; Cocias, T.; Macesanu, G. A survey of deep learning techniques for autonomous driving. J. Field Robot. 2020, 37, 362–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Sallab, A.; Abdou, M.; Perot, E.; Yogamani, S. Deep reinforcement learning framework for autonomous driving. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1704.02532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perot, E.; Jaritz, M.; Toromanoff, M.; De Charette, R. End-to-end driving in a realistic racing game with deep reinforcement learning. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops, Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 3–4. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, P.; Chan, C.Y.; de La Fortelle, A. A reinforcement learning based approach for automated lane change maneuvers. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE Intelligent Vehicles Symposium (IV), Changshu, China, 26–30 June 2018; pp. 1379–1384. [Google Scholar]

- Lillicrap, T.P. Continuous control with deep reinforcement learning. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1509.02971. [Google Scholar]

- Mirchevska, B.; Pek, C.; Werling, M.; Althoff, M.; Boedecker, J. High-level decision making for safe and reasonable autonomous lane changing using reinforcement learning. In Proceedings of the 2018 21st International Conference on Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITSC), Maui, HI, USA, 4–7 November 2018; pp. 2156–2162. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, D.; Hajidavalloo, M.R.; Li, Z.; Chen, K.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, L.; Wang, Y. Deep multi-agent reinforcement learning for highway on-ramp merging in mixed traffic. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2023, 24, 11623–11638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foerster, J.; Farquhar, G.; Afouras, T.; Nardelli, N.; Whiteson, S. Counterfactual multi-agent policy gradients. Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell. 2018, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desjardins, C.; Chaib-Draa, B. Cooperative adaptive cruise control: A reinforcement learning approach. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2011, 12, 1248–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Wang, M.; Song, W.; Yang, Y.; Fu, M. Multi-agent reinforcement learning-based decision making for twin-vehicles cooperative driving in stochastic dynamic highway environments. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2023, 72, 12615–12627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santini, S.; Salvi, A.; Valente, A.S.; Pescape, A.; Segata, M.; Cigno, R.L. Platooning maneuvers in vehicular networks: A distributed and consensus-based approach. IEEE Trans. Intell. Veh. 2018, 4, 59–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabiani, F.; Grammatico, S. Multi-vehicle automated driving as a generalized mixed-integer potential game. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2019, 21, 1064–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, F.; Cheng, X.; Wang, P.; Chan, C.Y.; Zhang, J. Automated lane change policy using proximal policy optimization-based deep reinforcement learning. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE Intelligent Vehicles Symposium (IV), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 19 October–13 November 2020; pp. 1746–1752. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, W.; Li, X.; Hu, J.; Song, X.; Dong, X.; Kong, D.; Xu, Q.; Ren, C. A rear anti-collision decision-making methodology based on deep reinforcement learning for autonomous commercial vehicles. IEEE Sens. J. 2022, 22, 16370–16380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Huang, B.; Liu, T.; Lin, X. Highway decision-making and motion planning for autonomous driving via soft actor-critic. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2022, 71, 4706–4717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamran, D.; Engelgeh, T.; Busch, M.; Fischer, J.; Stiller, C. Minimizing safety interference for safe and comfortable automated driving with distributional reinforcement learning. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Prague, Czech Republic, 27 September–1 October 2021; pp. 1236–1243. [Google Scholar]

- Jafari, R.; Ashari, A.E.; Huber, M. CHAMP: Integrated Logic with Reinforcement Learning for Hybrid Decision Making for Autonomous Vehicle Planning. In Proceedings of the 2023 American Control Conference (ACC), San Diego, CA, USA, 31 May–2 June 2023; pp. 3310–3315. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, Y.F.; Tan, G.Z.; Si, H.W. RTA-IR: A runtime assurance framework for behavior planning based on imitation learning and responsibility-sensitive safety model. Expert Syst. Appl. 2023, 232, 120824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shalev-Shwartz, S.; Shammah, S.; Shashua, A. On a formal model of safe and scalable self-driving cars. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1708.06374. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, S.; Lee, K.; Jeon, H.; Kum, D. Autonomous vehicle cut-in algorithm for lane-merging scenarios via policy-based reinforcement learning nested within finite-state machine. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2022, 23, 17594–17606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Pei, X.; Xu, J.; Zhang, X.; Xi, W. Decision-making in autonomous driving by reinforcement learning combined with planning & control. In Proceedings of the 2022 6th CAA International Conference on Vehicular Control and Intelligence (CVCI), Nanjing, China, 28–30 October 2022; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, Y.; Tan, G.; Si, H.; Li, J. Drl-gat-sa: Deep reinforcement learning for autonomous driving planning based on graph attention networks and simplex architecture. J. Syst. Archit. 2022, 126, 102505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wu, J.; Li, Y. The driving safety field based on driver vehicle road interactions. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2015, 16, 2203–2214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouton, M.; Nakhaei, A.; Isele, D.; Fujimura, K.; Kochenderfer, M.J. Reinforcement learning with iterative reasoning for merging in dense traffic. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITSC), Rhodes, Greece, 20–23 September 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus, C.; Lopez, J.G.; Kochenderfer, M.J. Runtime Safety Assurance Using Reinforcement Learning. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/AIAA 39th Digital Avionics Systems Conference (DASC), San Antonio, TX, USA, 11–15 October 2020; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Van Hasselt, H.; Guez, A.; Silver, D. Deep reinforcement learning with double q-learning. Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell. 2016, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEEE VT. White paper-literature review on kinematic properties of road users for use on safety-related models for automated driving systems. In Literature Review on Kinematic Properties of Road Users for Use on Safety-Related Models for Automated Driving Systems; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2022; pp. 1–35. [Google Scholar]

- Leurent, E. An Environment for Autonomous Driving Decision-Making. 2018. Available online: https://github.com/eleurent/highway-env (accessed on 2 December 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the World Electric Vehicle Association. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.