Abstract

This study addresses the critical issue of high casualty rates in frontal collisions by proposing structural optimization methods for the energy-absorbing box of lightweight electric vehicles. A small pure electric car was selected as the research object. A finite element model for frontal collision was established in HyperMesh and solved using the LS-DYNA explicit dynamics solver. The parameters such as the acceleration of the B-pillar of the vehicle, the compression distance of the energy absorption box and the energy absorption are analyzed in this study. Energy absorption was used as the primary crashworthiness indicator while ensuring that the peak collision force, compression distance of the energy-absorbing box, and acceleration of the B-pillar complied with safety standards. Results demonstrate that Scheme 2 (featuring reduced wall thickness and a single induced groove) outperformed other designs, increasing energy absorption by 3% and reducing mass by 17% compared to the baseline model. This conclusion can provide a reference basis for the subsequent vehicle collision analysis.

1. Introduction

According to the Ministry of Public Security (2025), by the end of 2024, the national stock of new energy vehicles reached 31.4 million units, accounting for 8.90% of the total vehicle fleet, and this represents a 51.49% increase compared to 2023, demonstrating a trend of rapid growth. Against the backdrop of rapid NEV industry development, enhancing passive safety performance is particularly crucial. Relevant studies indicate that the highest casualty rate is caused by the frontal collisions in road traffic accidents, followed by side impacts []. When a vehicle collides, the maximum deformation usually occurs at the front end, and the energy absorber is precisely the core component at the front end that absorbs collision energy. To improve the energy absorption efficiency of the energy absorber and further reduce collision-induced injuries to occupants, scholars at home and abroad have conducted relevant research in this field. In a finite element study by E Kösedağ [], crash boxes of four different geometries were analyzed under the condition of constant cross-sectional area. The study revealed the following order of energy-absorption performance, from highest to lowest: hexagonal, circular, square, and triangular. Xianjun Song [] took the compression displacement and specific energy absorption of the circular-section cone-shaped energy-absorbing box as the optimization goals, calculating the section thickness of the energy-absorbing box and the distance between the induction grooves and the cone angle of the energy-absorbing box to improve the impact resistance and energy absorption. Mr. Wu X and Zhang J [] studied the influences of the conical bottom angle, tube-wall thickness, the number, position, height and depth of induction grooves, and the parameters of gradient foam on the energy absorption properties of the EABes under axial low-velocity impact. Li Q Q and Li E [] obtained the optimal design solutions for front rail cross-sections through multi-objective optimization according to the key information of benchmark vehicles and high-strength steels, aiming to enhance vehicle crash performance while reducing structural mass. Djamaluddin F [] and Renreng I [] proposed to develop a new type of foam-filled crash box with a different design based on the double-tube construction. While foam-filled structures enhance energy absorption, their full application is often limited by weight, cost, and manufacturing complexity, as noted in the prior literature. Furthermore, many existing studies on energy-absorbing boxes utilize designs or multi-objective optimization schemes that are inconsistent with actual vehicle structures or are difficult to manufacture. Consequently, these methods have rarely been applied to small pure electric vehicles. To address this gap, this study conducts an optimized design for a small pure electric vehicle. A corresponding finite element model is established, and the explicit dynamics finite element method is employed. This approach is chosen for its ability to accurately simulate material nonlinearity and failure during collisions [] and effectively evaluate the dynamic mechanical properties of the energy-absorbing box [].

The method of optimizing the thickness of the energy-absorbing box and the position parameters of the induction groove has produced good optimization results []. Three structural optimization schemes of the energy-absorbing box are proposed with two parameters referred to from the above methods in this study. The original simulation model was established according to the regulations. The deformation law of the energy-absorbing box and the occupant protection performance of the original model were evaluated. The energy absorption of the energy-absorbing box is regarded as the final evaluation index under the condition that the collision peak force and compression distance of the energy-absorbing box and the acceleration of the B-pillar accord with the safety standards. Scheme 2 is defined as the optimal scheme to effectively improve the energy absorption of the energy-absorbing box while achieving the lightweight effect. This study provides a reference for the development of new models in the future, especially small pure electric vehicles.

This paper makes three key contributions to the field of electric vehicle crash safety:

- Innovative Structural Design and Optimization Method

By proposing three gradient optimization schemes (wall thickness reduction, single-induced groove design, and double-induced groove design), the crashworthiness of the energy absorber in electric vehicles is systematically improved. Among these schemes, Scheme 2 increases the energy absorption value by 3% while maintaining lightweight performance.

- 2.

- Specialized Solution for Small-Sized Battery Electric Vehicles

This is the first dedicated study on small-sized battery electric vehicles. Considering the layout characteristics of their under-chassis battery packs (which differ from the engine protection requirements of traditional fuel vehicles), a structure with a longer energy absorption stroke is designed.

- 3.

- Establishment of a Multi-Dimensional Evaluation System

With energy absorption as the core indicator, a multi-index evaluation system covering B-pillar acceleration, energy absorber compression distance, and cross-sectional force is established, forming a comprehensive crash safety assessment framework.

2. Establishment of the Finite Element Model

In order to effectively enhance the impact resistance of the car body, the structure of an integral body was adopted by this model. High-strength steel is used in key stress areas such as A-pillars, B-pillars and threshold beams, supplemented by some aluminum alloy components []. A front-mounted permanent magnet synchronous motor was adopted by the powertrain, while the lithium iron phosphate battery pack was integrated beneath the chassis with a single-speed fixed-ratio transmission. The measured curb weight of the vehicle reached 1240 kg. The engine of the front end of the diesel locomotive was mainly protected by the energy-absorbing box. The energy-absorbing box of the pure electric vehicle is to protect the battery pack in the center of the chassis. The front cabin space of the pure electric vehicle is more open, and a longer energy-absorbing stroke can be designed. Generally, the energy-absorbing box is longer than that of the diesel locomotive.

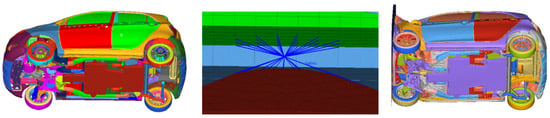

2.1. Geometry Simplification and Meshing

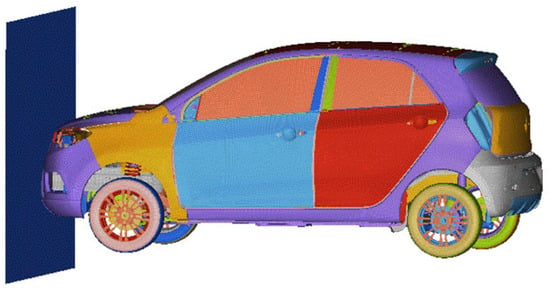

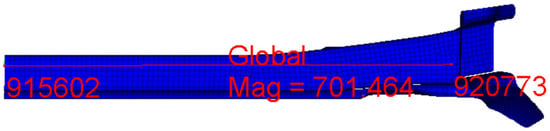

For the purpose of achieving the accuracy and efficiency of simulation calculation, the geometric model was simplified reasonably, and the mesh was divided with high quality [,]. The complex three-dimensional geometric structure of the energy-absorbing box of the small pure electric vehicle was necessarily simplified in this study. Firstly, minor features that had negligible impact on mechanical properties were eliminated, such as fillets and small apertures, and the primary load-bearing structures and critical connection points were retained. Simultaneously, contact regions like bolted connections were equivalently treated to significantly reduce model complexity while maintaining computational accuracy. Meshing was completed by the software of HyperMesh 14.0 and the partition strategy was implemented according to the structural characteristics []. The quadrilateral mesh and a very small number of triangular meshes used for transition were adopted by the energy-absorbing box, and the size of the element mesh was controlled within 5 mm. Critical deformation regions like the energy-absorbing boxes were made for local refinement with a minimum element size of 2 mm. A size of 10 mm × 10 mm was employed by secondary components such as the roof and rear body. To ensure the accuracy and reliability of the simulation results, approximately 939,000 mesh elements were generated, and the quality of these elements was checked to meet quality control standards such as Jacobi matrix > 0.7 and warping angle < 5°. Finally, the model shown in Figure 1 is established, and different parts of the vehicle are distinguished by different colors.

Figure 1.

Full-vehicle crash finite element model.

2.2. Material Properties, Connections, and Contact Settings

The control parameters such as the initial conditions, contact modes and constraints of the model were accurately set in the modeling process, and the key parameters such as the material properties (such as Poisson’s ratio, elastic modulus, etc.) and sheet thickness of the component were set with the aim of ensuring the accuracy of the simulation results. For example, in order to improve the structural strength and deformation behavior of the vehicle, the actual vehicle performance and process require that the thickness parameters of the components be set accurately []. The friction coefficient, material surface state and other factors were considered for the setting of contact parameters to ensure the simulation accuracy. The material of the energy absorption box and some parameters of the model are shown in Table 1. In addition, the constraint setting was required to conform to the actual working conditions to avoid model distortion caused by excessive or insufficient constraints. Scientific and reasonable parameter configuration can effectively enhance the reliability and engineering applicability of simulation results. The vehicle drive motor material was modeled as a rigid body and rigidly connected to the body structure. According to the Chinese national standard GB 11551-2014, known as “Occupant protection in frontal impacts for passenger cars”, it sets requirements for protecting car occupants in frontal crashes. The initial vehicle velocity was set to 50 km/h for a 100% frontal impact against a rigid wall. The gravitational acceleration parameter was set to 9.8 m/s2, and the total collision duration was configured as 0.1 s in the whole process.

Table 1.

Parameters of energy-absorbing box material and model.

3. Finite Element Analysis of Full-Vehicle 50 km/h Frontal Collision

3.1. Simulation Reliability Analysis

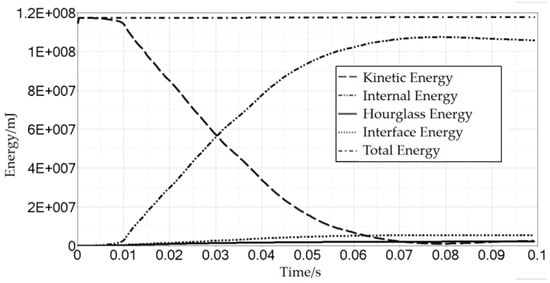

The mass increase and energy change caused by mass scaling and hourglass effect are focused on whether they are in a reasonable range during the simulation process to ensure the credibility of the frontal crash simulation results. The energy change data in the simulation process can be extracted through the HyperView 14.0 post-processing software, including key parameters such as total system energy, vehicle kinetic energy, vehicle internal energy, slip interface energy and hourglass energy []. The dynamic evolution process of the whole vehicle energy is presented during the collision process in Figure 2. The kinetic energy of the whole vehicle decreases rapidly at the initial stage of the collision, while the internal energy of the whole vehicle increases accordingly, and then both tend to be stable. The total energy of the system remains stable without abnormal fluctuations and accords with the law of conservation of energy.

Figure 2.

Full-vehicle frontal impact energy variation curve.

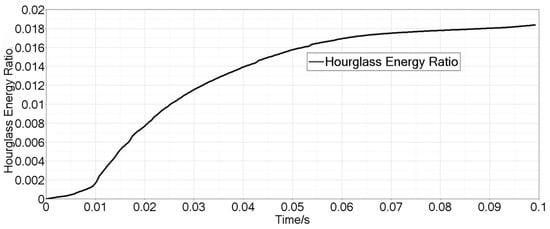

The hourglass energy ratio (the ratio of hourglass energy to total energy) is required to increase within 5% during the simulation process to avoid the influence of hourglass energy on the simulation accuracy []. The dynamic change curve of the hourglass energy ratio of this model is revealed in Figure 3. The results show that the hourglass energy ratio is less than 2%, which is much lower than the critical threshold of 5%. Since the hourglass energy ratio meets the industry-recognized standards, the established finite element model is proven to have high reliability, and the simulation results can be used for subsequent analysis.

Figure 3.

Hourglass energy ratio curve.

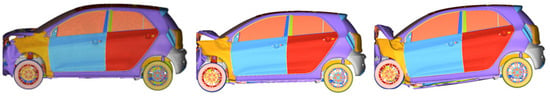

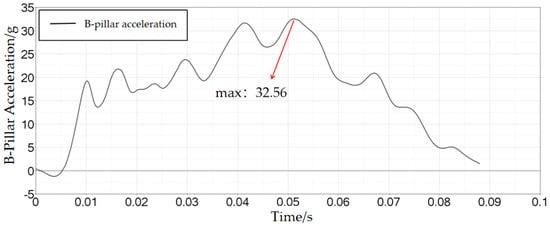

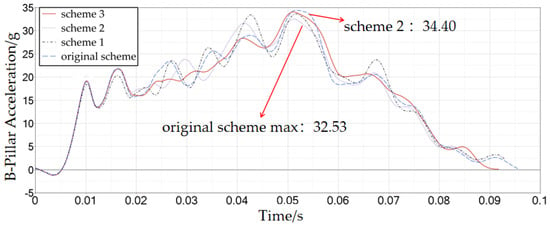

3.2. B-Pillar Acceleration Analysis

The deformation state of the body of the pure electric car is shown at different times (20 ms, 40 ms, 80 ms) during frontal collision in Figure 4. The damage to the front structure of the vehicle is caused by the collision. The front hood is significantly bent and uplifted upward, and the surrounding area of the front wheel is obviously folded and deformed for collapse, while the passenger compartment area maintains high structural integrity. As illustrated in Figure 5, the power battery is installed at the vehicle’s bottom. It connects to the vehicle body through a rigid joint mechanically equivalent to the actual bolted connection, ensuring negligible deformation of the power battery even in vehicle collisions. To ensure that the occupants in the vehicle are not caused by secondary damage due to the violent fluctuation of acceleration, which is studied in depth for the variation laws. The acceleration value of the lower end of the B-pillar is the key reference index, which can accurately reflect the acceleration characteristics of the passenger compartment [] in the optimization design of the occupant restraint system. As shown in Figure 6, the curve of the acceleration at the lower part of the left B-pillar is filtered by the SAE J211 Class 60 filter, and the peak acceleration is shown to rise first and then fall. If the peak value is too high, this will directly affect the safety protection effect of the occupant. If the actual peak value exceeds 60 g [], unqualified evaluations may occur because the impact of local instantaneous far exceeds the limit for the human body to bear (such as the risk of head and chest injury surge). The vehicle collision of this model stops at about 70 milliseconds under the condition of 50 km/h collision; the maximum peak acceleration of the left B-pillar is 32.56 g.

Figure 4.

Strain diagrams at 20 ms, 40 ms, and 80 ms.

Figure 5.

Installation location and connection mode of power battery.

Figure 6.

B-pillar acceleration curve.

4. Analysis of Energy-Absorbing Box Deformation Results

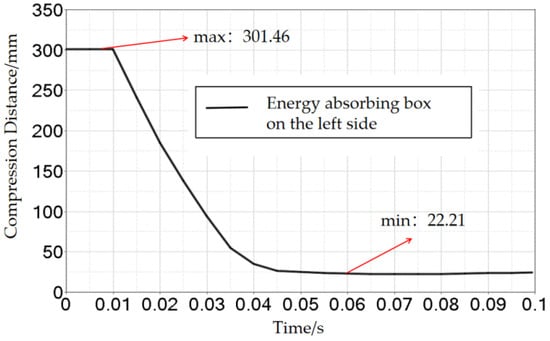

4.1. Compression Distance

As a key bridge between the anti-collision beam and the load-bearing body, the compression distance of the energy-absorbing box is evaluated to avoid the deformation and intrusion of the longitudinal beam for the passenger compartment caused by the impact between the front panel and the longitudinal beam. The automobile energy-absorbing box is the key energy-absorbing component of the automobile bumper system. The impact force is uniformly transmitted to the front longitudinal beam through its own structural deformation for frontal collision; in this way, the safety of passengers and other important structures of the vehicle is protected [,]. The average impact force caused by the insufficient crushing of the longitudinal beam is too large, but the deformation of the passenger compartment is caused by excessive compression. As illustrated in Figure 7, the compression distance of the energy-absorbing box is 279.25 mm. The deformation of the front panel before and after the collision is displayed in Figure 8. The results display that the deformation degree of the front panel is effectively controlled within the safety threshold after the collision, and there is no invasive impact on the living space of occupants and potential injury risk.

Figure 7.

Compression distance curve of the energy absorption box.

Figure 8.

Forward bulkhead strain diagram before and after collision.

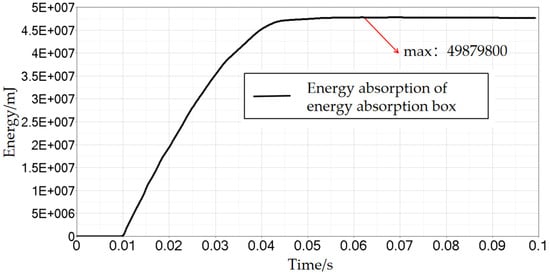

4.2. Energy Absorption

The energy absorption is utilized as the core evaluation index to quantitatively evaluate the crashworthiness of the energy-absorbing box in this study []. The energy absorption box is the core energy absorption device in the design of vehicle collision safety, and its structural design directly affects the collision safety of the vehicle []. The research shows that the energy absorption performance of the energy-absorbing box is significantly improved by optimizing the structural design. The peak of the energy absorption of the left box reaches 49.88 kilojoules from the curve during the collision process as shown in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

Energy absorption curve of the left energy-absorbing box.

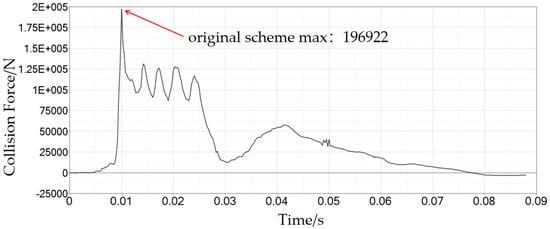

4.3. Cross-Section Force

The peak value of the cross-section force curve is one of the indicators to evaluate the crashworthiness of the energy-absorbing box, which determines the impact strength of the collision [,]. The risk of internal organ injury is increased by the excessive peak value of the cross-section force curve. The reasonable design of the cross-section force curve can ensure that more than 70% of the kinetic energy is absorbed by the energy-absorbing box and effectively avoids the damage of residual kinetic energy to the passenger compartment []. The section force curve (also known as the collision force curve) of the energy-absorbing box describes the relationship between the instantaneous collision force and the deformation of the energy-absorbing box during the axial compression process. The characteristics of the section force (collision force) curve of the left energy-absorbing box are shown in Figure 10. The maximum load of the energy-absorbing box reaches 196,922 N from the curve during the collision process, which illustrates that its performance is at a high level.

Figure 10.

Cross-section force curve of the left energy-absorbing box.

5. Optimization Design of Energy-Absorbing Box

5.1. Design Principles

In order to improve the performance of the energy-absorbing box and the frontal crash safety performance of the vehicle, safety and economy are considered in this optimization design, the following core criteria are established.

- (1)

- The energy dissipation mechanism of hierarchy is constructed for collision mechanics [], the energy of the front longitudinal beam is orderly absorbed under the guidance of the plastic deformation of the energy-absorbing box, and the progressive buffer system is formed.

- (2)

- The key is the control of the deformation mode of the energy-absorbing box. Non-ideal failure modes such as bending and rolling are avoided through structural design and material selection for dissipating collision energy along the preset path.

- (3)

- The crushing characteristics of the energy-absorbing box are optimized under low-speed collision conditions. Progressive deformation is required to be stable and uniform under axial load to avoid premature failure caused by local stress concentration. The deformation space of the energy-absorbing box is precisely designed and reasonably installed to reduce the occupation of the surrounding space under the premise of satisfying the manufacturing process and ensuring sufficient energy absorption [,].

- (4)

- The peak value of the collision force of the energy-absorbing box is strictly limited within the threshold range to reduce the cost of collision maintenance; the key components such as suspension and power system are protected from excessive load [].

- (5)

- The design concept of lightweight is adopted to achieve the goal of structural simplification, cost control and quality reduction under the condition of safety standards for low-speed collision [,].

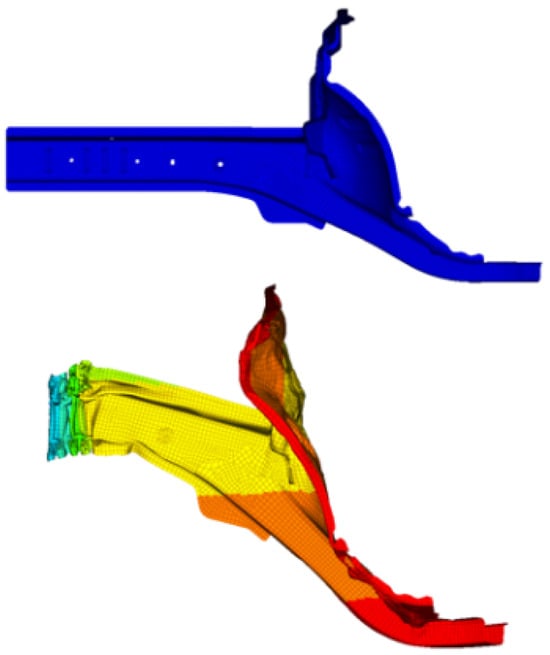

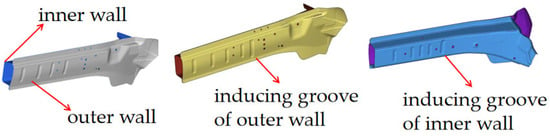

5.2. Scheme Design

Three gradient optimization schemes were proposed to further improve the energy absorption of the energy absorption box for vehicle frontal crash under the principle of structure optimization of the energy absorption box and the evaluation index of crashworthiness. The thickness of the outer wall of the energy-absorbing box in Scheme 1 was reduced from the original 1.8 mm to 1.5 mm to decrease the material redundancy and optimize the response of plastic deformation during collision under the condition of a lightweight design idea. The mass of the energy-absorbing box has decreased by 17%. In Scheme 2, a single induced groove structure was introduced under the condition that the thickness of the outer wall was decreased, and the crushing deformation path was guided through the design of local geometric weakening. In Scheme 3, the double induction groove was added under the condition of Scheme 1 to strengthen the possibility of axial progressive crushing of the energy-absorbing box. The specific structure of Scheme 1, Scheme 2 and Scheme 3 is shown in Figure 11. On the outer wall, a new induction groove with a length of 98 mm and a width of 20 mm has been added, and it is 30 mm away from the nearest induction groove on its left. On the inner wall, a new induction groove with a length of 75 mm and a width of 25 mm has been added, and it is 40 mm away from the nearest induction groove on its left. All the energy-absorbing box of design schemes meet the requirements of stiffness, process, assembly and the requirements of serial production and processing through pre-research.

Figure 11.

Optimization schemes curve of the energy-absorbing box.

6. Optimization Simulation Analysis

6.1. B-Pillar Acceleration Comparison

The acceleration of the left B-pillar of the original scheme and the three optimization schemes is compared in Figure 12. The results indicate that the left B-pillar accelerations of the three optimized schemes are 33.64 g, 34.46 g and 34.08 g, respectively, which are slightly higher than the original scheme. The maximum acceleration of these four schemes is very good to meet the requirements within the safe range of 60 g and far less than 60 g.

Figure 12.

Left B-pillar acceleration curve of four schemes.

6.2. Compression Distance Comparison

From an energy absorption perspective, a longer controlled crush distance is beneficial as it results in a lower average collision force. This force management is a key principle for ensuring occupant safety. Figure 13 shows that the change in the distance between the two points of the energy-absorbing box is recorded to obtain the compression distance. Table 2 presents simulation data on the compression distance for the four schemes. Further analysis indicates that front plate deformation in all four schemes does not reach the critical threshold for occupant injury—meaning that it is not the dominant factor contributing to occupant injury. A comparison of the compression distance metric across the four schemes reveals that the second scheme performs optimally, achieving a significantly lower compression distance than the other three.

Figure 13.

Compression distance measurement points curve of the energy-absorbing box.

Table 2.

Compression distance of the energy-absorbing box for four schemes.

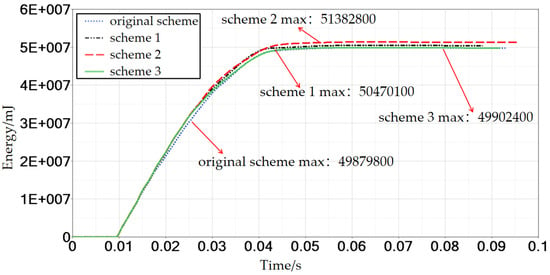

6.3. Energy Absorption

The energy absorption of the energy-absorbing box directly affects the crashworthiness performance of the vehicle and is the key factor for vehicle safety. The energy absorption performance of the original scheme and the three improved schemes is compared in Figure 14. The energy absorption value of the second scheme is 51.38 KJ higher than other schemes from the data in the figure. The energy absorption effect of the original scheme and Scheme 3 is similar (49.89 KJ and 49.90 KJ, respectively), and the absorbed energy is 50.5 KJ in Scheme 1, but the three are significantly lower than that of Scheme 2.

Figure 14.

Energy absorption curve of the energy-absorbing box for four schemes.

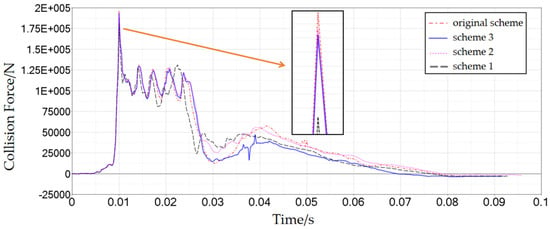

6.4. Cross-Section Force

A comparative study on the cross-section force response of the left energy-absorbing box of the original design scheme and the three modified schemes was carried out to systematically evaluate the mechanical properties of the optimization scheme for the energy-absorbing box. The peak values of the cross-section forces of each scheme are significantly different as summarized in Figure 15 and Table 3. The appearance of the peak is caused by the initial impact force. From high to low: original scheme, Scheme 2, Scheme 3, Scheme 1. Comparative analysis reveals that the synergistic design of wall thickness optimization and single-trigger groove yields superior cross-sectional force response with the baseline under low-speed impact conditions, and the cross-sectional force of Scheme 1 is the smallest among other solutions, which provides a reference for engineering design for the energy-absorbing box.

Figure 15.

Cross-section force curve for four schemes.

Table 3.

Cross-section force for four schemes.

6.5. Comparative Analysis of Optimization Results

The values of key performance indicators (such as total energy absorption value and compression displacement) are compared and analyzed under the condition of low-speed collision to evaluate the collision performance of the four optimization schemes more directly. The original design scheme has the worst performance in the index of collision peak force from the data in Table 4. The performance of the second scheme is significantly better than other schemes in terms of total energy absorption value and compression displacement. Compared with the original scheme, the total energy absorption is increased by 1,503,000 mJ, the compression distance is increased by 9.95 mm, the maximum acceleration of the left B-pillar is increased by 1.9 g, and the peak value of the collision force is reduced by 2711 N. In short, Scheme 1 performs worse in terms of collision peak force, and the second scheme is evaluated to achieve the best optimization effect from the perspective of total energy absorption value and compression displacement.

Table 4.

Crashworthiness indices for four schemes.

7. Conclusions

Three structural optimization schemes for the energy-absorbing box were proposed in this study to enhance the energy absorption efficiency of the energy-absorbing box and the safety performance of the vehicle collision. The results of this study echo Kösedağ’s exploration of geometric shapes and Song et al.’s application of induced slots but further reveal that there is an optimal solution for the number of induced slots, and over-design (such as Scheme 3) has little benefit. Compared with Djamaluddin’s foam filling scheme, the main advantage of the second scheme proposed in this study is to achieve a balance between lightweight (17% weight loss) and performance improvement, and the structure is simpler and easier to produce. Although the reliability of the simulation model is verified by the hourglass energy ratio (<2%), the results still need to be verified by experiments under a variety of working conditions.

Scheme 1 performs better than other schemes from the perspective of collision peak force. The original design performs worse than other schemes in this index. Scheme 2 achieves a better optimization effect from the perspective of total energy absorption value and compression displacement. Compared with the original scheme, the total energy absorption in Scheme 2 increased by 1,503,000 mJ, and the compression distance increased by 9.95 mm under the condition of quantitative analysis. More sufficient space is provided for dissipation of the collision energy, which reduces the transmission of impact load to the key components of the vehicle body, while the mass of the energy-absorbing box has decreased by 17%. Scheme 2 is defined as the optimal scheme to effectively improve the energy absorption of the energy-absorbing box while achieving the lightweight effect. Future research can be expanded in three directions: one is to explore multi-material (such as composite materials) hybrid structures to further improve efficiency; second, the optimization target is extended to complex conditions such as occupant injury index and offset collision. The third is to combine machine learning to achieve more intelligent and efficient design.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.T., Z.S., Y.Z. and J.L.; methodology, G.T., R.F. and H.S.; software, G.T., Z.S. and H.S.; formal analysis, G.T., Z.S., J.L. and R.F.; investigation, G.T., Y.Z. and J.L.; resources, G.T. and R.F.; data curation, G.T., Z.S. and Y.Z.; writing—original draft, G.T.; writing—review and editing, G.T.; project administration, G.T.; funding acquisition, G.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors acknowledge the financial support from Sichuan Tongchuan Electronic Technology Co., Ltd. (No. NCZYHX202525) and the key project of science and technology research program of Chongqing Education Commission of China (No. KJZD-K202201103).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Huiqiang Shu was employed by the company Guangzhou Xiaopeng Motors Technology Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that this research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. The authors declare that this study received funding from Sichuan Tongchuan Electronic Technology Co., Ltd. The funder was not involved in the study design, collection, analysis, interpretation of data, the writing of this article or the decision to submit it for publication.

References

- Hu, W.; Monfort, S.S.; Cicchino, J.B. The association between passenger-vehicle front-end profiles and pedestrian injury severity in motor vehicle crashes. J. Saf. Res. 2024, 90, 115–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kösedağ, E.; İşler, D. Effect of section geometry and material type on energy absorption capabilities of crash boxes. Karaelmas Fen. Mühendislik Derg. 2023, 13, 42–51. [Google Scholar]

- Song, X.; Liang, W.; Zhou, Y.; Tian, Z. Multi-objective Optimization of Energy-absorbing Box Based on ABAQUS Conical Addition of Induced Grooves. World Sci. Res. J. 2022, 8, 770–779. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, X.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, J.; He, R.; Liu, Q. Low-velocity impact of square conical gradient aluminium foam-filled automobile energy-absorbing boxes. Int. J. Crashworthiness 2024, 29, 330–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.Q.; Li, E.; Chen, T.; Wu, L.; Wang, G.Q.; He, Z.C. Improve the frontal crashworthiness of vehicle through the design of front rail. Thin-Walled Struct. 2021, 162, 107588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djamaluddin, F. Optimization of foam-filled crash-box under axial loading for pure electric vehicle. Results Mater. 2024, 21, 100505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renreng, I.; Djamaluddin, F.; Mar’uf, M.; Li, Q. Optimization of crashworthiness design of foam-filled crash boxes under oblique loading for electric vehicles. Front. Mech. Eng. 2024, 10, 1449476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalinsky, M.; Sykora, M.; Markova, J.; Maňas, P. Nonlinear dynamic finite element analysis of vehicle impacts into road restraint systems. Results Eng. 2024, 23, 102726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Z.; Li, Q.; Yao, L.; Hu, X. Stiffness Optimization for Hybrid Electric Vehicle Powertrain Mounting System in the Context of NSGA II for Vibration Decoupling and Dynamic Reaction Minimization. World Electr. Veh. J. 2025, 16, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vignesh, S.K.; Mayakrishnan, J.; Konig, P. Optimization of Energy Absorption and Deformation Characteristics of Aluminium Crash Box with the Effect of Groove along with a Screw. SAE Int. J. Adv. Curr. Pract. Mobil. 2024, 6, 2234–2242. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, J.; Pang, Q.; Hu, Z.; Sun, Q. Recent progress on regulating strategies for the strengthening and toughening of high-strength aluminum alloys. Materials 2022, 15, 4725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.; Dong, Y.; Zhang, D.; Su, X.; Yang, Y.; Lee, I. Review of three-dimensional model simplification algorithms based on quadric error metrics and bibliometric analysis by knowledge map. Mathematics 2023, 11, 4815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Gu, F.; Wang, L.; Ma, S.; Golmohammadi, A.-M.; Zhang, S. The Design and Optimization of a Novel Hybrid Excitation Generator for Vehicles. World Electr. Veh. J. 2024, 15, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, A.; Lu, C.; Liu, W. Lightweight design and analysis of steering knuckle of formula student car using topology optimization method. World Electr. Veh. J. 2023, 14, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuliano, G.; Polini, W. Strain state in metal sheet axisymmetric stretching with variable initial thickness: Numerical and experimental results. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 8265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Wen, R.; Chen, L.; Zhou, Y.; Duan, L.; Wang, W. Study on Dynamic Response and Anti-Collision Measures of Aqueduct Structure Under Vehicle Impact. Buildings 2025, 15, 851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Wang, Z.; Du, X.; Wang, N. Design of a New Energy Absorbing Box with Honeycomb Structure for Vehicles and Research on Vehicle Crashworthiness. Iran J. Sci. Technol. Trans. Mech. Eng. 2025, 49, 1813–1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, M.; Li, Z.; Li, M. Investigation on the mechanical uncertainty of resistance spot weldings and its effect on structure crashworthiness of automotive B-pillars under side impacts. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part D J. Automob. Eng. 2024, 239, 6559–6574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Zuriaga, A.M.; Dols, J.; Nespereira, M.; García, A.; Sajurjo-De-No, A. Analysis of the consequences of car to micromobility user side impact crashes. J. Saf. Res. 2023, 87, 168–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeshanew, E.S.; Ahmed, G.M.S.; Sinha, D.K.; Badruddin, I.A.; Kamangar, S.; Alarifi, I.M.; Hadidi, H.M. Experimental investigation and crashworthiness analysis of 3D printed carbon PA automobile bumper to improve energy absorption by using LS-DYNA. Adv. Mech. Eng. 2023, 15, 16878132231181058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noorsumar, G.; Rogovchenko, S.; Robbersmyr, K.G.; Vysochinskiy, D. Mathematical models for assessment of vehicle crashworthiness: A review. Int. J. Crashworthiness 2022, 27, 1545–1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshahrani, H.; Sebaey, T.A.; Hegazy, D.A.; El-Baky, M.A.A. Development of efficient energy absorption components for crashworthiness applications: An experimental study. Polym. Adv. Technol. 2022, 33, 2921–2942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, J.; Zhou, J.; Wang, J.; Xi, X.; Liu, X.; Duan, Y.; Guan, Z.; Cantwell, W.J. Energy-absorbing characteristics of hollow-cylindrical hierarchical honeycomb composite tubes under conditions of dynamic crushing. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2023, 243, 110254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, S.; Yuan, M.; Zheng, B.; Peng, X.; Zhang, X. Mechanisms of chest injuries from steering wheel intrusion in frontal collisions. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part D J. Automob. Eng. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X. Speed Relation to Energy Dissipation in Vehicle Collisions Based on Three-Dimensional Deformation. Master’s Thesis, California State University, Sacramento, CA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.-C.; Liu, N.-N.; An, C.-C.; Wu, H.-X.; Li, N.; Hao, K.-M. Dynamic crushing behaviors and enhanced energy absorption of bio-inspired hierarchical honeycombs with different topologies. Def. Technol. 2023, 22, 99–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saber, A.; Amer, A.M.; Shehata, A.I.; El-Gamal, H.A.; Abd_Elsalam, A. Recent Developments in Additively Manufactured Crash Boxes: Geometric Design Innovations, Material Behavior, and Manufacturing Techniques. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 7080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wesselmecking, S.; Kreins, M.; Dahmen, M.; Bleck, W. Material oriented crash-box design–Combining structural and material design to improve specific energy absorption. Mater. Des. 2022, 213, 110357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaikumar, M.; Koenig, P.; Vignesh, S.; Bentgens, F.; Hariram, V. Impact of vehicle collision using modified crash box in the crumple zone-A perspective assessment. Int. J. Veh. Struct. Syst. 2022, 14, 524–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Wang, Q.; Lu, W.; Li, Y. Integrated uncertain optimal design strategy for truss configuration and attitude–vibration control in rigid–flexible coupling structure with interval uncertainties. Nonlinear Dyn. 2025, 113, 2215–2238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edel, F.; Pulkus, C.; Kim, S.; Erhardt, J.; Kuijpens, S. Investigation and development of textile lightweight bodies for urban logistic vehicles. World Electr. Veh. J. 2023, 14, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the World Electric Vehicle Association. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).