Abstract

This paper proposes a method for the on-site localization of autonomous vehicles in large-scale outdoor environments, where a single sensor cannot achieve the high precision for localization. The method is based on an improved Kalman filter by fusion of odometry and LiDAR, and it is intended to address the challenge of localization in large-scale environments. Given the complex nature of such environments and the difficulty of identifying natural features at the worksite accurately, the paper uses artificial landmarks to model the working environment. The Iterative Closest Point (ICP) algorithm matches local features of landmarks that were scanned by LiDAR at the current time with local landmark features from the past to obtain the vehicle’s on-site pose. Within the extended Kalman filter (EKF) framework, odometry information is fused with the pose information obtained by the ICP algorithm to further enhance the accuracy of the vehicle’s localization. Simulation results demonstrate that the localization accuracy of unmanned vehicles optimized by the EKF algorithm improves by 9.21% and 53.91% compared to the ICP algorithm and odometry, respectively. This reduces the noise error of measurements, which improves the precise movement and on-site localization performance of unmanned vehicles in large-scale outdoor environments.

1. Introduction

Faced with the midst of the Artificial Intelligence (AI) and digitalization revolution, the construction industry is one of the key areas for industrial digitalization. Among these, autonomous vehicles can replace workers in performing repetitive, high-load, and high-risk mobile tasks, such as transporting construction materials, laying materials, and cleaning, thereby effectively shortening the construction lifecycle and driving the digitalization and intelligent upgrading of the construction industry []. Reliable localization in large-scale outdoor environments is the foundation for the stable operation of autonomous or semi-autonomous mobile unmanned vehicles. However, a single sensor typically cannot meet the on-site localization accuracy requirements of unmanned vehicles. If reliance is solely on measurement feedback from odometry, mobile unmanned vehicles will experience cumulative errors, leading to increasing movement deviations over time, and the limited environmental data obtained is insufficient for mobile operations. If only LiDAR is used to obtain pose information, sudden changes in environmental noise, LiDAR noise, and algorithm matching errors can lead to significant localization errors in the vehicle. Therefore, designing a multi-sensor fusion localization system to achieve on-site localization for unmanned vehicles is a comprehensive solution to explore.

The current mainstream localization technologies for autonomous vehicles primarily include: Simultaneous Localization and Mapping (SLAM) technology []; multi-sensor fusion localization technology []; GPS localization technology []; ultrasonic navigation localization technology [], among others. Among these, feature-based matching methods in SLAM can accurately determine the spatial relationships between autonomous vehicles, such as the ICP algorithm and its variants. However, these methods must address issues such as noise interference in point cloud data, incomplete information, and uneven sampling density []. Filter-based techniques can rapidly and effectively estimate the state of unmanned vehicles, just as the Finite Impulse Response (FIR) structure state estimator and Generalized Minimum Variance FIR (GMVF) filter are developed [,]. Additionally, the Kalman filter is commonly applied in target tracking and localization, and it is regarded as the optimal linear state estimator. The nonlinearity of the system model limits the effective application of the Kalman filter, leading to the development of EKF and unscented Kalman filter (UKF) for nonlinear models [,,]. The EKF introduces the concept of linearization based on the classical Kalman filter, making it more suitable for solving nonlinear models. The UKF provides accurate estimates for nonlinear systems under ideal conditions, but modeling errors may accumulate, which typically leads to filter divergence. State estimation methods based on Gaussian approximation have gained increasing attention due to their advantages of good estimation accuracy, moderate computational complexity, and ease of implementation []. Pak designed an extended MVF filter and combined it with Horizon Group Shift (HGS) to form the HGS-FIR filter []. Compared to the UKF, the HGS-FIR filter takes 60 times longer to compute the estimated values and has weaker resistance to external noise interference. To overcome the design flaws of the HGS-FIR filter, the TLNF filter and the fused TLNF/UK filter are further designed []. To enhance the real-time positioning performance of unmanned vehicles, the integrated Global Positioning System (GPS) and Inertial Measurement Unit (IMU) navigation scheme serves as the fundamental positioning solution. However, in GPS-denied environments such as urban canyons, this method suffers from significant cumulative errors. Meanwhile, LiDAR-based SLAM can achieve positioning and mapping without GPS, yet it involves high costs and demands substantial computational resources for processing feature-rich point clouds. Although visual SLAM offers a low-cost alternative for positioning, it is prone to failure in outdoor settings with poor lighting or insufficient texture details. Therefore, adopting a multi-sensor fusion positioning approach can improve rapid localization and robustness for unmanned vehicles in outdoor environments.

The localization performance of outdoor autonomous vehicles is closely related to the measurement values of sensors, which are susceptible to various external interferences, faults, and attacks, such as false measurements, missing measurements, delayed measurements, and non-Gaussian measurement noise. Developed for autonomous vehicle steering systems, a fault-tolerant path-tracking controller utilizing static output-feedback and linear parameter varying techniques is presented []. Its operational framework employs dual-mode coordination between steering and torque-vectoring control to preserve vehicle stability in the presence of steering actuator gain faults. Among them, Intentional Electromagnetic Interference (IEMI) comprises the conducted interference and radiated interference []. Conducted interference infiltrates vehicular electronic systems through physical conductors such as power lines and communication cables, while radiated interference involves attackers projecting high-frequency electromagnetic waves toward vehicles from a distance via directional antennas or high-power electromagnetic pulse devices. These emissions can couple into critical sensor systems and Controller Area Network (CAN) bus lines of unmanned vehicles. The specific impacts manifest as follows: IEMI can induce sensor failure across multiple modalities. In LiDAR systems, strong electromagnetic noise generates substantial artifacts in point cloud data, potentially causing complete distortion; for imaging sensors, electromagnetic saturation may produce entirely white or streaked output frames; regarding high-precision GPS/IMU integrated navigation systems, electromagnetic interference directly disrupts high-frequency circuitry and signal reception, leading to significant positioning deviations or complete navigation failure. Concurrently, IEMI induces communication interruptions and protocol violations in CAN. Furthermore, when IEMI power exceeds electronic components’ tolerance thresholds, it can cause thermal breakdown or electrical overstress damage to sensor chips, main processors, and power components. The Minimum Mean Square Error (MMSE) criterion is employed in state estimation using nonlinear Kalman filters, and a Huber–Kalman filter (HKF) that suppresses outliers in both the system and observation data is proposed []. The robust Student’s t-based Kalman filter (RSTKF) utilizes the Student’s t-distribution to model heavy-tailed non-Gaussian noise, thereby generating robust posterior estimates []. Additionally, Information Theory Language (ITL) [] has been applied to counteract non-Gaussian noise, incorporating metrics such as the Maximum Correntropy Criterion (MCC) from ITL into adaptive filtering theory to capture higher error statistics. Replacing the MMSE criterion in the Kalman filter with the MCC, the maximum correntropy Kalman filter (MCKF) [] and the maximum correlation entropy unscented Kalman filter (MCUKF) [,,] are also developed for combating non-Gaussian noise.

For the uncertainty noise data generated by multiple sensors of autonomous vehicles, a line feature SLAM algorithm is combined with EKF, and the EKF is used to estimate the robot’s position state []. The UKF is combined with Pedestrian Dead Reckoning (PDR) to fuse the results of Wi-Fi localization, which achieved localization results superior to those obtained by the single sensor of Wi-Fi or PDR []. A Kalman filter algorithm based on the maximum entropy correlation criterion is proposed and applied to address the issue of non-Gaussian distribution data in UWB indoor localization under complex environmental conditions []. The BIM-based indoor navigation using end-to-end visual localization and ARCore is proposed, which enhances robot localization through BIM’s map [].

Based on the above, although existing research has made progress in improving the accuracy and robustness of outdoor positioning for unmanned vehicles, further exploration is still required to achieve a balance between high performance and low cost while maintaining reliable positioning performance in construction scenarios characterized by GPS signal obstruction and lack of natural features. In addition, the large-scale outdoor environments typically feature uneven terrain, which can cause autonomous vehicles to slip, resulting in significant discrepancies between the odometry-measured speed and the actual speed. Therefore, it is essential to realize the fusion estimation by LiDAR and odometry. In our paper, the term “large-scale” primarily refers to the fact that the working area for outdoor material handling tasks is substantially larger than the structural dimensions of the unmanned vehicle itself, and the vehicle must move to complete the transportation tasks. The term “large-scale” herein does not carry a strict quantitative value. Additionally, the Kalman filter, as a mature probabilistic localization technique, significantly reduces the interference of various uncertainty errors while ensuring computational efficiency and minimal memory usage, thereby enhancing localization accuracy and real-time performance. Therefore, in conjunction with outdoor material handling tasks, this paper proposes LiDAR sensors and odometry to design a localization optimization system for an unmanned vehicle based on an extended Kalman filter in an outdoor construction environment.

The main innovations of this paper are as follows:

- (1)

- Due to the mixed features of the large-scale construction environment that are difficult to identify and extract effectively, this paper proposes an artificial landmark to build the construction map, which realizes on-site localization of the unmanned vehicle based on the landmark map.

- (2)

- Considering the rapid and robust localization performance of on-site, the paper provides an extended Kalman filter framework to combine the current pose of the unmanned vehicle by odometry information, and the ICP algorithm is adopted to match the current landmark feature with that scanned at the previous moment.

- (3)

- Simulation experiments were conducted to validate the fused localization solution of an unmanned vehicle based on the operational path that considers the flatness of the on-site environment, and the results from odometry, ICP matching, and EKF-fused methods are obtained and compared.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 provides model descriptions of the environment map and the unmanned vehicle. Section 3 describes the on-site localization methods of unmanned vehicles based on an improved framework of the EKF algorithm. Section 4 presents the simulation experiments and discusses the results. Finally, the conclusion and future work are presented in Section 5.

2. Model Descriptions

For the outdoor handling tasks, unlike indoor service robots, unmanned vehicles rely heavily on good localization performance, which is crucial for them to perform tasks efficiently and accurately in outdoor environments. Considering that the operating areas in outdoor scenarios have obvious undulations and complex time-varying characteristics, it is difficult for unmanned vehicles to extract effective environmental features for localization.

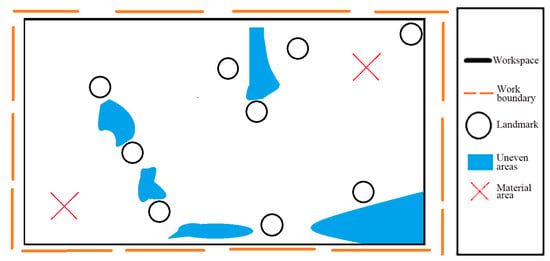

This makes the method based on landmark arrangement a simple and reliable solution. Specifically, on-site localization of the unmanned vehicle is achieved by arranging artificial landmarks on-site and extracting data through LiDAR scanning, and the specific operating environment is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Two-dimensional plan of the large-scale outdoor environment.

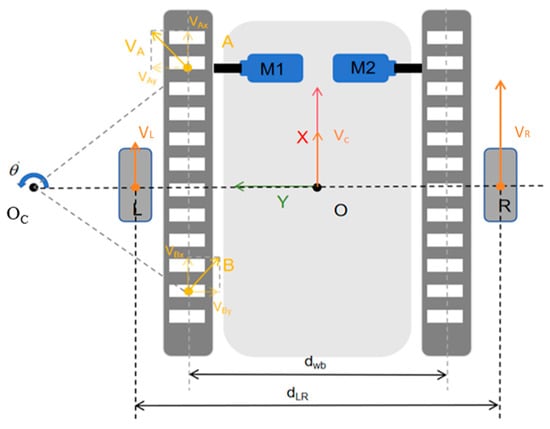

In this paper, the tracked unmanned vehicle is simplified into the motion model of a two-wheeled differential drive robot, where and represent the linear velocities of the left and right wheels, respectively; dLR denotes the wheel spacing, and rC and VC represent the rotation radius of point O and total velocity of vehicle, which are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Motion model for an equivalent two-wheeled differential-drive unmanned vehicle.

Taking O-OL as the horizontal axis and the X-axis as the vertical axis, the positions of the equivalent virtual left and right wheels are at points L and R, respectively. By calculating the velocity of center O through the velocities of the left and right driving wheels, the forward kinematics model of the unmanned vehicle can be obtained as follows:

By decomposing the velocity of the centroid O, the velocities of the left and right driving wheels are derived, and the inverse kinematics model is simplified as follows:

Since the distance between the equivalent left and right wheels (denoted as ) of the unmanned vehicle is not necessarily equal to the actual distance between the two tracks, and is dynamically variable, a dimensionless parameter is introduced. Through derivation, the virtual wheel spacing can be expressed as:

where represents the wheel spacing of the unmanned vehicle; is the coefficient of the wheel spacing, which is related to the relative friction coefficient between the unmanned vehicle’s tracks and the ground, total load, turning radius, and centroid position.

Thus, the forward kinematics model of the unmanned vehicle can be obtained as:

The inverse kinematics model is as follows:

Finally, the system state equation of the unmanned vehicle can be derived from the linear velocity and angular velocity as follows:

where parameter is a state vector containing the displacement in the x-axis direction, the displacement in the y-axis direction, the angle r, and the linear velocity v; the parameter dt is the time interval for sensor data acquisition, and the parameter represents the process noise vector of the system.

3. Localization Framework of Unmanned Vehicle in Large-Scale Outdoor Environment

The research object is an unmanned vehicle equipped with a 2D LiDAR and odometry, and the global landmark map and initial pose information of the unmanned vehicle are also known. Based on the global point cloud map, the unmanned vehicle can scan the current local map in real time and match it with the global map to obtain the current pose of the robot. It is assumed that the initial pose of the unmanned vehicle satisfies the rough matching condition of the ICP algorithm, which avoids the matching from falling into a local optimal solution, and the transformation matrix for each subsequent frame of ICP is derived from the previous frame.

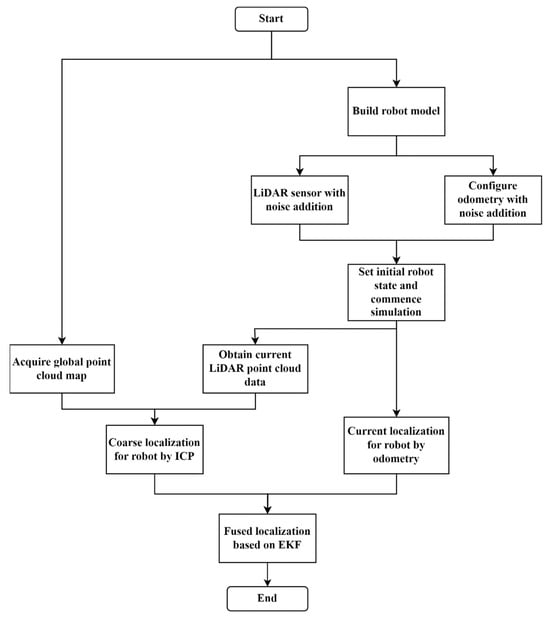

Therefore, this paper proposes an improved Kalman localization optimization scheme based on the fusion of LiDAR and odometry. The specific global localization optimization framework flow of the unmanned vehicle is shown in Figure 3. First, the current XOY coordinate position and angle r of the robot are calculated based on the odometry. Considering the existence of cumulative errors in long-term odometry measurements, the reliability of the pose information fed back by the odometry will decrease, which is corrected and compensated for by the LiDAR measurement results. Meanwhile, with time frames as the unit, each time frame is designed to have an interval of 0.1 s, and each frame includes odometry information collection, point cloud information from LiDAR, point cloud matching based on ICP, and localization results from the improved Kalman filter, to obtain the optimized pose of the robot in each time frame in real time. In the improved Kalman filter framework, a prediction model is established to enable the prediction and estimation of the pose from the previous frame to the current frame. Then, the pose information (X, Y) from odometry and the fused pose results of the x and y axes matched by the ICP algorithm are used as the optimized estimation results of the current frame, which are applied to the prediction and estimation of the next frame.

Figure 3.

Flowchart of the global localization framework for the unmanned vehicle.

3.1. Localization of Unmanned Vehicle Based on Feature Matching of Artificial Landmarks

The rough localization of the unmanned vehicle is realized based on the ICP matching algorithm, that is, to solve the transformation matrix T that minimizes the distance between the target point cloud and the source point cloud . The source point cloud is the local point cloud information acquired by the laser radar, and the target point cloud is the global point cloud map, so , and the relationship between target point cloud Q and source point cloud P before matching is , thus obtaining . Then, the corresponding homogeneous transformation matrix T (Rotation matrix R, Translation matrix t) can be solved based on the parameters and .

Also, the objective function of the point cloud matching error can be obtained as:

where the parameter n represents the number of point clouds acquired by the laser radar, and it belongs to [1, Np].

The basic matching steps of the specific ICP algorithm are as follows:

- (1)

- Take the source point cloud P, denote its point cloud set as , and detect potential landmark arc feature points;

- (2)

- Generate a descriptor for each feature point, and obtain the subset in the target point cloud Q that satisfies ;

- (3)

- Take and as input quantities, and obtain the rotation matrix R and translation matrix t that minimize E(R,t) through the similarity of feature vector matching;

- (4)

- Obtain a new point cloud set based on the rotation and translation matrices R and t;

- (5)

- Calculate the average distance from to again;

- (6)

- When the average distance is less than the set threshold or the number of iterations exceeds the maximum set number of iterations, stop the iteration, jump out of the loop, and output the current transformation matrix;

- (7)

- When the condition in step 6 is not met, return to step 2 and continue the iteration.

3.2. Optimization of Localization for Unmanned Vehicle by an Improved Kalman Filter

The extended Kalman filter algorithm, as an improved filtering method for nonlinear systems, has state-space equations that can be expressed as:

where and are the nonlinear function equations, respectively; and represent normal distributions with an expected value of 0; Qc and Rc are the a priori process noise and a priori measurement noise of the covariance matrix, respectively; represents the measurement of point cloud features of artificial landmarks acquired by LiDAR; and the nonlinear function computes the theoretical coordinates of the landmarks observed from the vehicle’s pose and which represent the additive measurement noise of the LiDAR system.

However, the calculation of the nonlinear model is complex and time-consuming. To improve the on-site performance of the unmanned vehicle, this paper solves the nonlinear model through a linearization method. It is assumed that when linearizing at , the higher-order terms in the series expansion are ignored, and the error near the point is set to 0. Thus, at time k, the nonlinear functions f() and h() are expanded in a first-order Taylor series, and the posterior state estimate after ignoring the higher-order terms is used to obtain an approximate linearized model as follows:

where and are the Jacobian matrices obtained by differentiating the function f with respect to the parameters x and w at time k + 1, respectively.

Finally, the nonlinear EKF algorithm is transformed into the classic Kalman filtering algorithm for calculation, and the state estimation value X[k+1] at the next moment k + 1 is predicted through the prediction and update steps. The specific implementation process is as follows:

Initialize the initial values of parameters, mainly including the initial state estimation value and the covariance matrix of the initial state estimation error.

Calculate the a priori state estimation:

Then, calculate the corresponding Jacobian matrices and , and the specific equations are:

Based on the covariance matrix of the previous state estimation error and the Jacobian matrix calculated from the process noise matrix , the covariance matrix of the a priori state estimation error can be obtained:

At the same time, its Jacobian matrix is calculated as:

The calculation of the Kalman gain can be obtained as:

The calculation of its posterior state estimation is:

Update the covariance of the state estimation error, and the specific equation is depicted as:

4. Simulation Experiment and Analysis

4.1. Experimental Preparation

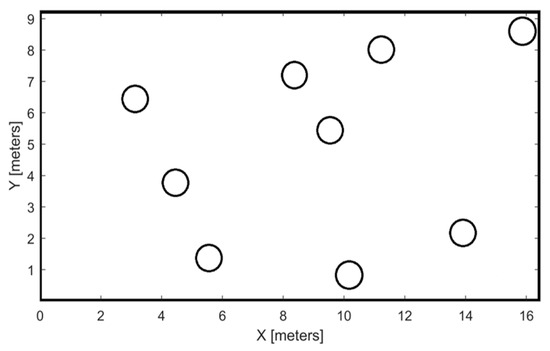

According to the transportation task in a large-scale outdoor environment, artificial landmarks are randomly arranged to construct a prior map to avoid its symmetry. The specific scene model is shown in Figure 4. A large-scale transportation working scene is designed according to the operation task, and the path for the mobile unmanned vehicle to carry out the transportation operation is also designed.

Figure 4.

Specific scene model with placement of artificial landmarks.

Among them, the design of the prior map needs to consider in advance factors such as building tunnels, equipment obstacles, and fences in the working area, and the information about positions with obvious depressions, protrusions, and so on in the construction area is known, which effectively prevents the unmanned vehicle from slipping and feature mismatching caused by unevenness. Under the above condition, a total of nine cylindrical landmarks are arranged, and it is assumed that the unmanned vehicle can achieve self-localization at any location on its movement route.

To confirm the measurement characteristics of actual sensors in this experiment, the LiDAR sensor noise that made by SLAMTEC of china is modeled using a Gaussian distribution, with the measurement noise parameters calibrated based on robotic localization data from another study [] to simulate real-world localization of an unmanned vehicle. As a result, Gaussian noise with a mean of 0 is added to construct the point cloud data of LiDAR. For odometry, cumulative translation noise with a signal-to-noise ratio of 35 and cumulative rotation noise with a signal-to-noise ratio of 30 are added to prevent the unmanned vehicle from drifting. In addition, Gaussian noise is added to the input quantities of the velocity and angular velocity that control the robot to simulate process noises such as crosswind and frictional sliding.

4.2. Effect of On-Site Localization

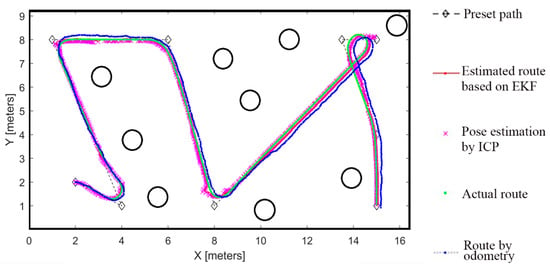

To effectively verify the optimization effect of the proposed algorithm in this paper on the on-site localization of the unmanned vehicle, under the simulated landmark map, this paper compares the actual travel route of the unmanned vehicle, the feedback route based on the odometry, the estimated route based on ICP, and the estimated route after fusing the extended Kalman filter. The specific routes are shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Global view of the autonomous planning route for the unmanned vehicle.

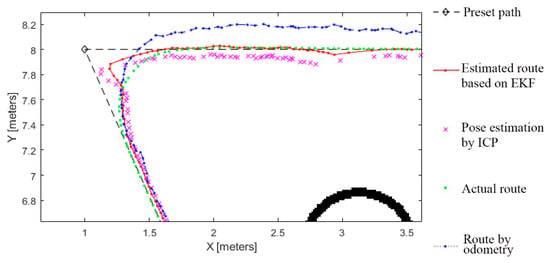

As can be seen in Figure 5, specific routes are represented by different parameter symbols, mainly including the preset path of the unmanned vehicle (black “◇” dotted line), the odometry route (blue dotted line), the ICP-based estimated route (pink “×” line), the EKF-based estimated route (red dot-dash line), and the actual movement route of the unmanned vehicle (green dotted line). From the partially enlarged view of Figure 6, the unmanned vehicle’s route optimized by EKF is closer to the actual route compared with the estimated route by ICP and the feedback route of odometry. When the ICP has a large map-matching error, the movement route fused with the EKF algorithm can significantly reduce the impact caused by the unmanned vehicle’s matching error.

Figure 6.

Partially enlarged view of the autonomous planning route for the unmanned vehicle.

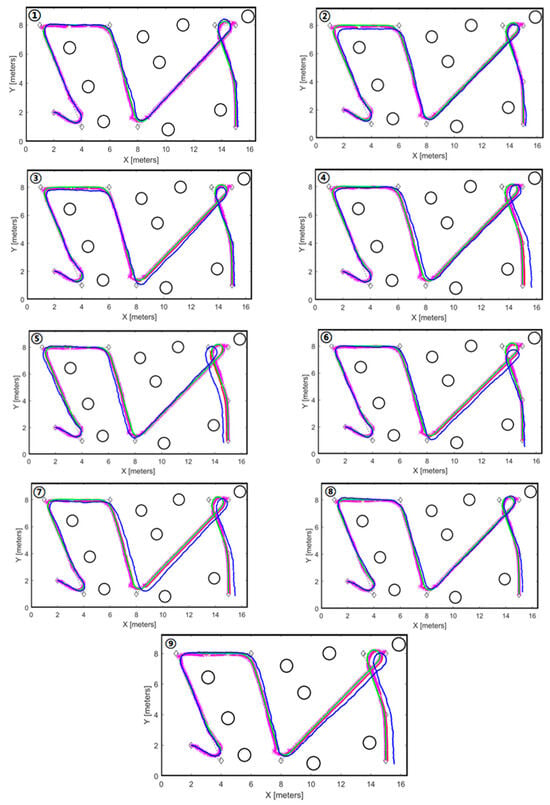

To effectively verify the localization effect of an unmanned vehicle optimized based on EKF, this paper conducts 10 simulations on the same route. Through random noise generation, different movement routes of the unmanned vehicle are obtained, and the other simulated routes of nine numbers are shown in Figure 7. As a result, the preset path, estimated route based on EKF, pose estimation by ICP, the actual route and route by odometry are represented as the diamond-shaped dashed lines, red dotted solid lines, cross marks with pink, green dots and blue dotted dashed lines, respectively.

Figure 7.

Schematic diagram of repeated operation routes performed nine times by an unmanned vehicle.

4.3. Results and Discussion

From the above tests, it can be concluded that even under the influence of cumulative odometry errors, the unmanned vehicle route optimized based on EKF can effectively correct the deviation from the actual route.

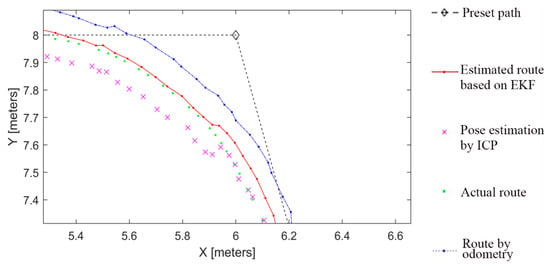

As shown in Figure 8, when the process noise is consistent with the measurement noise in the simulation experiment, the covariance matrices for them are represented as Q and R, respectively, and the estimation results based on EKF can offset the excessively varying measurement noise. In this paper, assuming the initial values of Q and R are diagonal matrices and approximately equivalent. After the parameters for them are obtained by numerous simulation experiments and verification, the values of parameters Q and R are set as follows:

Figure 8.

Enlarged comparison diagram of local routes for an unmanned vehicle.

Even when there is a large error between the source point cloud and target point cloud, the route optimized based on EKF can effectively correct the movement trajectory of the unmanned vehicle, thereby reducing the impact caused by a sudden increase in matching errors.

To further verify the superiority of each method, this paper quantitatively analyzes the localization effect of the unmanned vehicle by calculating the Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE) in the x and y axis directions. The specific formula for the RMSE is:

where n is the number of samples, is the true value, and is the predicted value.

Then, the total localization error of the unmanned vehicle is obtained as:

where n is the number of samples, are the true values, and are the predicted values, respectively.

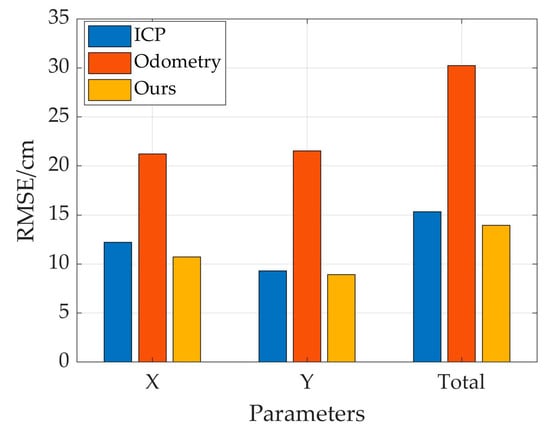

As it is depicted in Table 1, the feedback localization error based on odometry is the largest, and it is significantly higher than the pose errors based on ICP and the extended Kalman filter. After 10 simulation tests, the RMSE results of localization for the unmanned vehicle are obtained, and they are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Results of the simulation experiment based on three methods.

Due to the high-noise characteristic of odometry, when designing the noise measurement matrix, the covariance corresponding to odometry is significantly larger than the localization covariance based on ICP, which makes the final motion route estimated based on EKF closer to the estimated route based on ICP. The comparative results of localization errors for an unmanned vehicle based on three methods are shown in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

Comparative results of localization errors for an unmanned vehicle based on three methods.

5. Conclusions

This paper fully considers the measurement errors of sensors in real environments, adds appropriate process noise and measurement noise, and quantitatively evaluates the optimization effects of various localization algorithms through Root Mean Squared Error under multiple simulation experiment comparisons. The experimental results show that the localization effect based on the EKF framework is significantly better than that of single-sensor measurement. Compared with the matching effect based on ICP, it effectively reduces the localization Root Mean Squared Error by 1 cm, and when there is an obvious sudden error in the ICP matching results, this algorithm can also effectively reduce the impact of sudden errors on the localization estimation of the unmanned vehicle. At the same time, the localization accuracy of the unmanned vehicle based on the extended Kalman filter is improved by 9.21% and 53.91%, respectively, compared with the localization results based on the ICP algorithm and the feedback pose based on the odometry. This effectively reduces the noise error of LiDAR scanning and improves the mobile operation effect of the unmanned vehicle in large-scale outdoor environments. In future work, we will explore the optimization algorithms to systematically tune the Q and R parameters of the Kalman filter and adopt a deep learning algorithm to improve the matching efficiency and localization accuracy of the unmanned vehicle. Also, we will establish a systematic fault injection experimental platform to quantitatively analyze the fault tolerance boundaries for concurrent multi-sensor failures under electromagnetic interferences []. Furthermore, we will design and construct a physical unmanned vehicle platform integrating LiDAR and odometry and validate the proposed algorithm in a controlled outdoor condition.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.Y.; methodology, L.X.; software, J.Y.; validation, J.Y., H.F. and H.Z.; formal analysis, H.F.; investigation, H.Z.; resources, L.X.; data curation, J.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, J.Y. and L.X.; writing—review and editing, L.X.; visualization, H.F.; supervision, L.X.; project administration, L.X.; funding acquisition, L.X. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by Research and Application of Key Technology Integration for Intelligent Operation and Maintenance of Rail Transit under grant number ZJXL-SJT-202315A2.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Jianbiao Yan, Lizuo Xin, Hongjin Fang, and Hanxiao Zhou are employees of Zhejiang Rail Transit Operation Management Group Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Alandoli, E.A.; Fan, Y.; Liu, D. A review of extensible continuum robots: Mechanical structure, actuation methods, stiffness variability, and control methods. Robotica 2025, 43, 764–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, H.; Zhao, X.; Liu, B.; Jia, Y.; Wang, G.; Wang, C. Enhancing Real-Time Visual SLAM with Distant Landmarks in Large-Scale Environments. Drones 2024, 8, 586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, H.; Zhao, Y.; Lin, T.; Wu, J. Research on Multi-Sensor Simultaneous Localization and Mapping Technology for Complex Environment of Construction Machinery. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 8496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raja, M.; Guven, U. Design of obstacle avoidance and waypoint navigation using global position sensor/ultrasonic sensor. INCAS Bull. 2021, 13, 149–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.C.; Chen, H.C.; Wong, C.C.; Lai, C.Y. Omnidirectional Ultrasonic Localization for Mobile Robots. Sens. Mater. 2022, 34, 453–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Li, G.; Wang, R.; Li, L. Wheeled Robot Visual Odometer Based on Two-dimensional Iterative Closest Point Algorithm. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2023, 2504, 012002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jazwinski, A. Limited memory optimal filtering. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control. 1968, 13, 558–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, W.H.; Han, S. Receding Horizon Control: Model Predictive Control for State Models; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Khodarahmi, M.; Maihami, V. A review on Kalman filter models. Arch. Comput. Methods Eng. 2023, 30, 727–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.R.; Sul, S.K.; Park, M.H. Speed sensor less vector control of induction motor using extended Kalman filter. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 1994, 30, 1225–1233. [Google Scholar]

- Sarkka, S. On unscented Kalman filtering for state estimation of continuous-time nonlinear systems. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control. 2007, 52, 1631–1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, B.; Xin, M. Grid-Based Nonlinear Estimation and Its Applications; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Pak, J.M.; Ahn, C.K.; Lim, M.T.; Song, M.K. Horizon group shift FIR filter: Alternative nonlinear filter using finite recent measurements. Measurement 2014, 57, 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.E.; Kang, H.H.; Ahn, C.K. Two-Layer Nonlinear FIR Filter and Unscented Kalman Filter Fusion with Application to Mobile Robot Localization. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 87173–87183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meléndez-Useros, M.; Viadero-Monasterio, F.; Jiménez-Salas, M.; López-Boada, M.J. Static Output-Feedback Path-Tracking Controller Tolerant to Steering Actuator Faults for Distributed Driven Electric Vehicles. World Electr. Veh. J. 2025, 16, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jie, H.; Zhao, Z.; Zeng, Y.; Chang, Y.; Fan, F.; Wang, C.; See, K.Y. A review of intentional electromagnetic interference in power electronics: Conducted and radiated susceptibility. IET Power Electron. (PEL) 2024, 17, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Hawary, F.; Jing, Y. Robust regression-based EKF for tracking underwater targets. IEEE J. Ocean. Eng. 1995, 20, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, N.; Chambers, J. Robust student’s t based nonlinear filter and smoother. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2016, 52, 2586–2596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Príncipe, J.C. Information Theoretic Learning: Renyi’s Entropy and Kernel Perspectives; Springer Science Business Media: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, B.; Liu, X.; Zhao, H.; Príncipe, J.C. Maximum correntropy Kalman filter. Automatica 2017, 76, 70–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Qu, H.; Zhao, J.; Yue, P.; Wang, M. Maximum correntropy unscented Kalman filter for spacecraft relative state estimation. Sensors 2016, 16, 1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Li, N.; Zhang, Y. Maximum correntropy unscented Kalman and information filters for non-Gaussian measurement noise. J. Frankl. Inst. 2017, 354, 8659–8677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Qu, H.; Zhao, J.; Yue, P. Maximum correntropy square-root cubature Kalman filter with application to SINS/GPS integrated systems. ISA Trans. 2018, 80, 195–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, J.; Guo, J.; Li, Y. Simultaneous localization and mapping (SLAM)-based robot localization and navigation algorithm. Appl. Water Sci. 2024, 14, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, I.; Shen, Y.; Su, X.; Esposito, C.; Choi, C. A Localization Based on Unscented Kalman Filter and Particle Filter Localization Algorithms. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 2233–2246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Zhang, H.; Ding, W.; Shi, P.; Chen, H. UWB/IMU integrated indoor positioning algorithm based on robust extended Kalman filter. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2025, 36, 016303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Chen, J.Y.; Sun, T.; Fan, W.; Sun, X.Y.; Shao, Y.; Guo, G.Q.; Wang, H.L. Robotic motion planning for autonomous in-situ construction of building structures. Autom. Constr. 2025, 171, 105993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Yan, Z.X.; Song, T.; Xu, Z.; Zeng, L.D. Improvement of localization with artificial landmark for mobile manipulator. Int. J. Adv. Robot. Syst. 2019, 16, 172988141986298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jie, H.; Zhao, Z.; Li, H.; Gan, T.H.; See, K.Y. A Systematic Three-Stage Safety Enhancement Approach for Motor Drive and Gimbal Systems in Unmanned Aerial Vehicles. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2025, 40, 9329–9342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the World Electric Vehicle Association. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).