1. Introduction

The global transition toward sustainable transportation has accelerated rapidly over the past decade, with electric vehicles (EVs) emerging as a key solution for mitigating Greenhouse Gas (GHG) emissions and reducing dependence on fossil fuels. According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), global EV stock surpassed 10 million units in 2020, marking an annual growth rate of approximately 43% [

1,

2]. This momentum is projected to continue, with global EV sales expected to reach nearly 60 million units by 2025 [

2]. Technological advancements, declining battery costs, and stringent environmental regulations have collectively fueled this expansion. Manufacturers such as BYD exemplify this trend, increasing production from fewer than 500,000 units between 2019 and 2021 to nearly 4.5 million units in 2024 through strategic investment in energy management and battery technologies [

3,

4].

The ongoing electrification of transportation, however, presents new challenges for power systems. In countries where electricity generation is still dominated by fossil fuels, the large-scale adoption of EVs risks shifting emissions from the transportation sector to the power sector. Therefore, integrating renewable energy into EV charging infrastructure is essential for achieving genuine decarbonization and supporting global net-zero targets [

1].

In Kuwait and across the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) region, the adoption of EVs presents both opportunities and challenges. The increased demand for electricity associated with EV charging may intensify pressure on national grids, which are currently dependent on fossil fuels—over 90% of Kuwait’s electricity generation is derived from oil and natural gas [

5,

6]. Projections suggest that by 2030, Kuwait’s total electricity demand could nearly triple, amplifying the urgency to diversify the national energy mix [

5]. To address this, Kuwait has committed to producing 15% of its electricity from renewable sources by 2030, consistent with the country’s long-term sustainable development framework under Kuwait Vision 2030 [

7,

8].

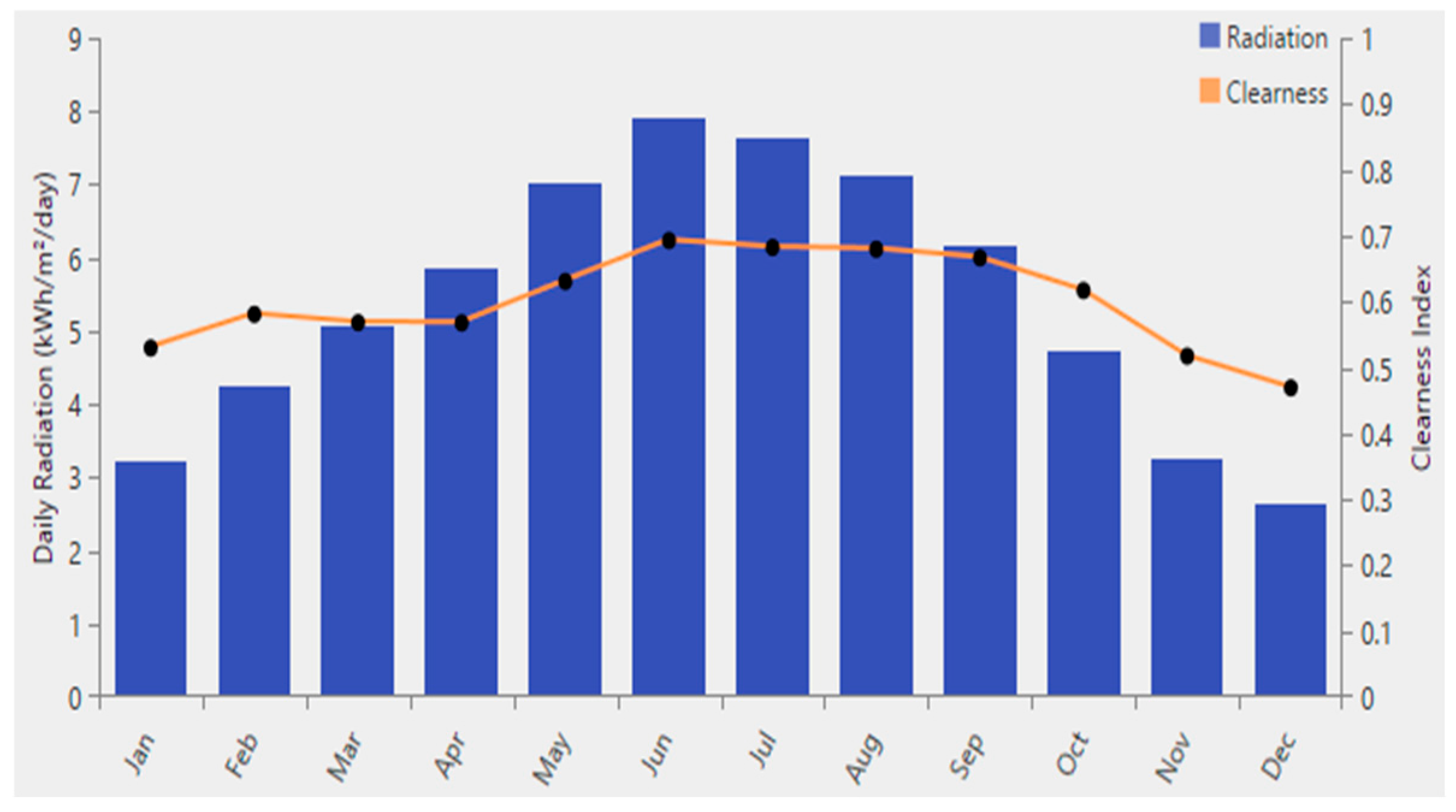

Kuwait’s climatic and geographic conditions offer significant potential for renewable energy integration. The nation receives more than 2600 h of sunlight annually, with average Global Horizontal Irradiance (GHI) values between 5.2 and 5.8 kWh/m

2/day [

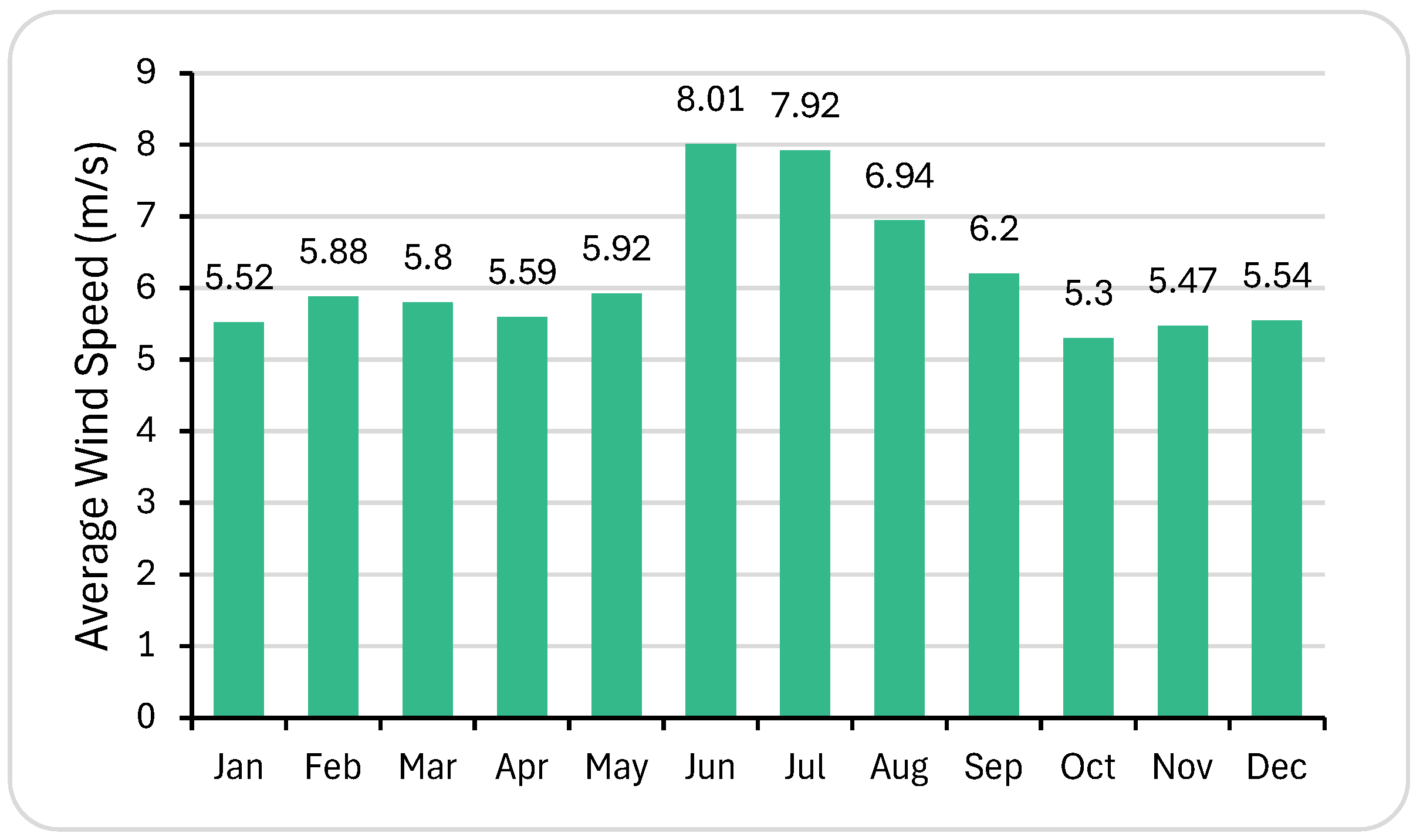

9]. Additionally, moderate to strong wind resources, particularly in coastal and desert areas, provide opportunities for complementary solar–wind hybrid systems. Similar renewable expansion targets are observed across other GCC states: the United Arab Emirates aims to generate 50% of its electricity from clean energy by 2050 [

10]; Saudi Arabia plans to install more than 58 GW of renewable capacity, primarily solar and wind, under Vision 2030 [

11]; and Qatar continues to invest in solar power while exploring alternative low-carbon technologies [

12].

Despite these advancements, fossil fuels remain the dominant source of energy across the region, leading to high per capita emissions and environmental concerns [

13]. The deployment of renewable-powered EV charging infrastructure thus presents a practical approach to reducing emissions while supporting grid stability and energy diversification. However, large-scale adoption requires comprehensive feasibility studies addressing technical, economic, and environmental aspects under local conditions.

Achieving Kuwait’s renewable energy target of 15% by 2030 will depend on the successful integration of multiple renewable sources and effective system optimization. Hybrid systems combining solar photovoltaic (PV) and wind power, supported by smart grid management and potential energy storage, offer a promising solution for reliable, clean, and cost-effective EV charging [

14]. This study, therefore, investigates and compares four grid-connected configurations: grid-only, grid–solar, grid–wind, and grid–solar–wind hybrid systems, focusing on their techno-economic feasibility and environmental performance using HOMER Pro 3.18.4 software.

The motivation behind this research arises from the pressing need to develop sustainable EV charging infrastructure tailored to Kuwait’s unique climatic and economic conditions. Although numerous global studies have investigated renewable-based EV charging systems, few have conducted a detailed techno-economic comparison between grid-only, solar-assisted, wind-assisted, and hybrid solar–wind configurations specifically for Kuwait. The country’s high solar irradiance and strong seasonal winds present an exceptional opportunity for hybrid renewable integration, yet these resources also pose operational challenges due to extreme heat and environmental conditions. The innovation of this work lies in applying a comprehensive HOMER-based optimization to quantify the economic, technical, and environmental trade-offs among these four configurations while incorporating Kuwait-specific data on irradiance, wind speed, and grid tariffs. Unlike prior regional studies that focused exclusively on solar-powered EV charging, this research introduces a comparative hybrid framework that evaluates renewable fraction, Levelized Cost of Energy, Net Present Cost, and CO2 emission reductions under realistic grid-connected scenarios. The outcomes provide a scientifically grounded foundation for designing efficient, cost-effective, and sustainable EV charging systems aligned with Kuwait Vision 2030 and the broader decarbonization goals of the GCC region.

2. Literature Review

Hybrid Renewable Energy Systems (HRESs) have gained significant attention as a practical and sustainable approach to combining multiple renewable sources for enhanced efficiency, reliability, and economic performance. Such systems are particularly effective in offsetting the intermittency of individual energy resources, such as solar or wind, through hybrid integration and intelligent energy management [

15].

Several comprehensive reviews have analyzed hybrid system architectures, energy management strategies, and control approaches. Vivas et al. [

16] and Indragandhi et al. [

17] provided detailed analyses of hybrid renewable systems that integrate solar PV, wind, and hydrogen-based storage technologies. Their work covered the design, control, and operational strategies of key components—including wind turbines, PV arrays, batteries, fuel cells, and electrolysers—emphasizing that optimal control methods are critical for improving system reliability and lowering life-cycle costs.

The HOMER (Hybrid Optimization of Multiple Energy Resources) software developed by the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) has been widely adopted for the modelling and optimization of HRESs [

18,

19]. HOMER enables techno-economic simulations of complex hybrid systems by optimizing the balance between renewable generation, grid contribution, and operational cost under varying conditions of load, resource availability, and financial parameters.

Kelthom et al. [

18] used HOMER to evaluate a PV/Wind/Diesel/Battery hybrid system for rural telecommunication centres in Adrar, Algeria. Their results indicated that hybrid configurations can substantially reduce fuel consumption and carbon emissions compared to diesel-only systems, achieving a Cost of Energy (COE) of USD 0.468/kWh. Similarly, Chaleekure et al. [

20] applied HOMER Pro to evaluate a grid-connected hybrid system serving a sports stadium in Chaiyaphum, Thailand. The authors found that on-grid systems were significantly more cost-effective than off-grid alternatives, mainly due to the high cost of battery storage. The grid-connected system achieved a COE of USD 0.0115/kWh and a Net Present Cost (NPC) of USD 27,307, whereas the off-grid system required extensive battery capacity (962 kWh) and was therefore economically unfeasible.

Beyond conventional optimization, Artificial Intelligence (AI) and advanced control strategies have also been introduced to improve the efficiency of hybrid systems. Phan and Lai [

21] proposed a reinforcement learning-based control framework that incorporated hybrid Maximum Power Point Tracking (MPPT) algorithms within a Q-learning structure. Their study, validated through MATLAB/Simulink and HOMER simulations, demonstrated enhanced system stability and faster convergence under dynamic weather conditions compared to conventional MPPT techniques. Fotopoulou et al. [

22] developed a day-ahead optimization model that integrated Vehicle-to-Grid (V2G) technology into a smart grid context, achieving 82% self-consumption and 15% V2G participation. Their results highlighted the importance of forecasting accuracy and demand-side management for maximizing renewable utilization in hybrid systems.

In Kuwait, Alazemi et al. [

23] assessed a mobile solar charging station for mini electric vehicles using HOMER software. Their model, based on a daily load of 15.2 kWh and a peak demand of 7.98 kW, demonstrated that a solar-based system could achieve technical and economic viability under Kuwait’s high solar irradiance of approximately 5.475 kWh/m

2/day. Alrajhi et al. [

24] further analyzed private EV charging stations integrating a 7 kW PV array and a 25 kW inverter. Their results indicated that solar integration could meet 82.9% of annual charging demand, reduce carbon emissions by 1908 kg/year, and achieve an NPC of USD 6653.

Baidas et al. [

25] investigated the feasibility of employing hybrid renewable energy systems (PV, wind turbines, batteries, and backup diesel generators) to power off-grid 4G/5G cellular base stations in two rural Kuwaiti sites. They found that depending on local resource profiles—higher wind speeds versus higher solar irradiance—various configurations can deliver 100% renewable energy supply with minimal land footprint and zero CO

2 emissions, while significantly reducing NPC compared to diesel-only systems. Their work demonstrates a practical application of renewable system design with detailed economic modelling via HOMER and highlights the critical role of localized resource data and techno-economic optimization in system selection for remote infrastructure.

The literature collectively demonstrates that hybrid renewable configurations, particularly those utilizing HOMER software, provide a reliable methodology for techno-economic analysis of renewable integration. However, despite several global and regional studies, few investigations have directly compared grid-only, solar, wind, and hybrid solar–wind systems for EV charging applications under Kuwait’s specific climatic conditions. This research addresses this gap by performing a comparative techno-economic and environmental evaluation of these four configurations using HOMER software, with the aim of identifying the optimal solution for sustainable EV charging in Kuwait.

3. Methods and Study Objectives

3.1. Methodology Overview

This study employs a simulation-based approach using HOMER Pro software to evaluate the techno-economic and environmental feasibility of grid-connected solar and wind energy systems for private EV charging stations in Kuwait. HOMER was selected for its ability to perform multi-objective optimization of hybrid renewable systems, simultaneously assessing energy balance, economic performance, and environmental impacts under site-specific conditions. The simulation aimed to identify the optimal system configuration that minimizes both the NPC and carbon emissions, while maintaining a reliable electricity supply for private EV charging applications.

Compared with previous studies that primarily analyzed single renewable configurations or generalized case studies, the present methodology introduces several improvements over the state of the art. First, it integrates four distinct grid-connected configurations—grid-only, grid–solar, grid–wind, and hybrid grid–solar–wind—within a unified optimization framework using HOMER Pro, enabling direct techno-economic and environmental comparison under identical operating conditions. Second, unlike earlier works that employed generic global resource datasets, this study incorporates Kuwait-specific hourly solar irradiance and wind-speed data, as well as locally subsidized grid tariffs and component cost structures, improving contextual accuracy. Third, the inclusion of a multi-parameter sensitivity analysis (±10% irradiance, ±15% wind speed, ±20% cost variation, and 3–7% discount rate) provides a more robust evaluation of system performance and resilience under uncertainty—an aspect often omitted in prior GCC studies. Finally, by quantifying renewable fraction, LCOE, NPC, and CO2 emission reductions simultaneously, the proposed approach delivers a more comprehensive decision-making tool for planners seeking optimal renewable EV integration under Kuwait’s climatic and economic conditions.

3.2. Simulation Setup

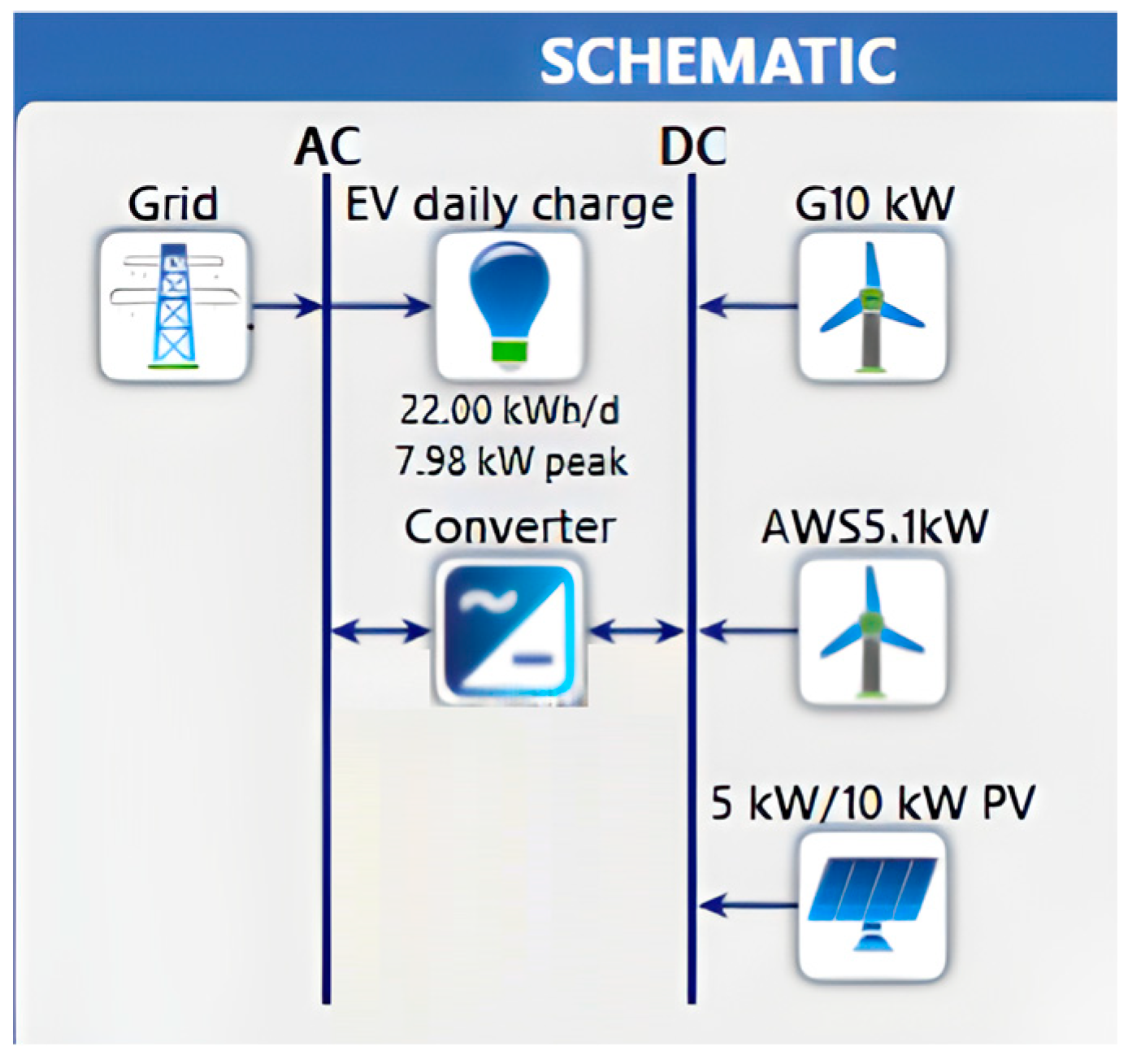

The analysis considered four distinct configurations:

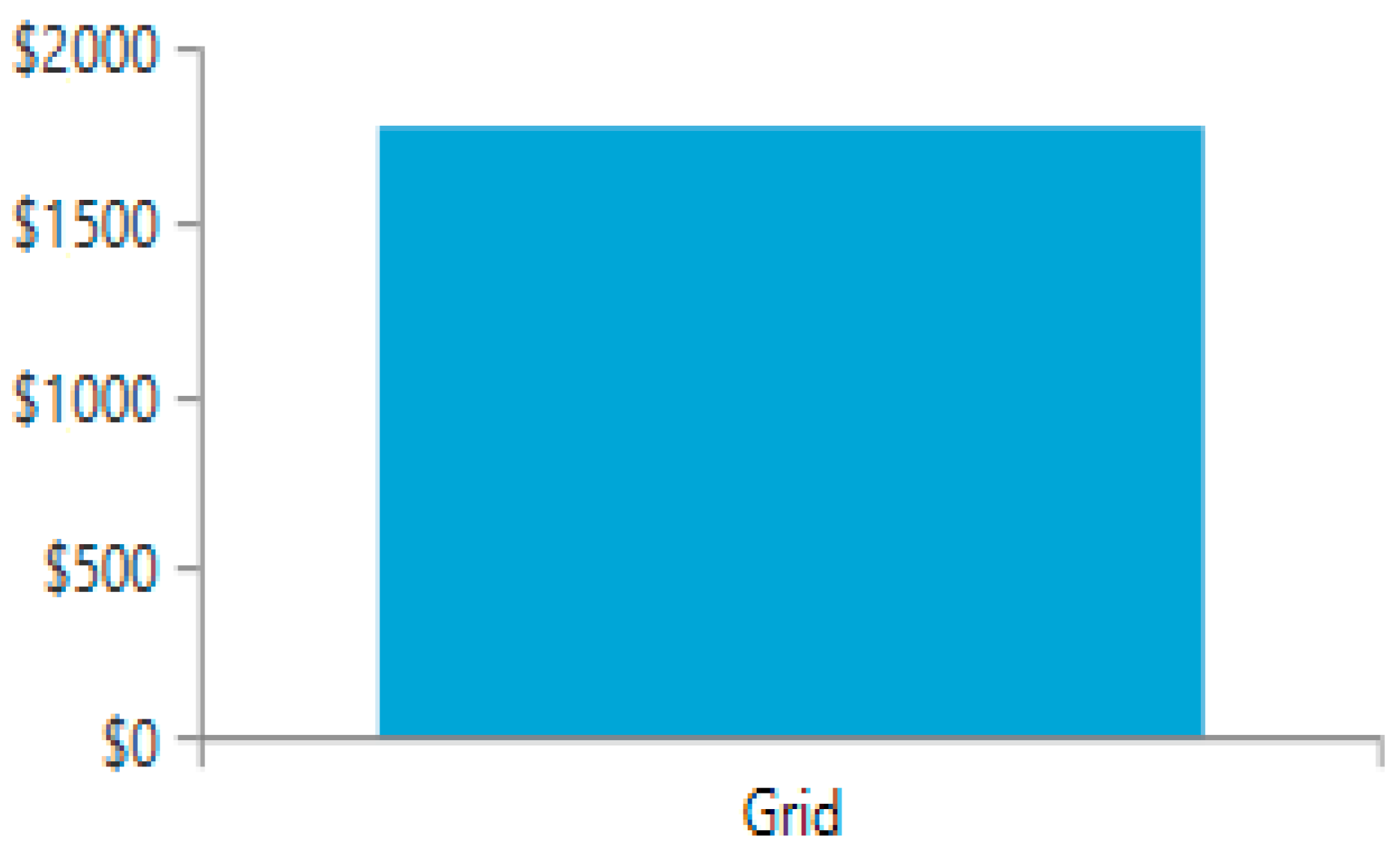

System 1—Grid-only: Conventional charging station powered entirely by grid electricity.

System 2—Grid–Solar: Grid electricity supplemented with a 5 kW PV array.

System 3—Grid–Wind: Grid electricity supported by a 5.1 kW wind turbine (AWS model).

System 4—Grid–Solar–Wind: Hybrid configuration combining both 5 kW PV and 5.1 kW wind turbine units.

Each configuration included a 5 kW inverter to ensure bidirectional power conversion between DC (renewable) and AC (grid/charging) systems. Default component lifespans, efficiencies, and maintenance schedules were adopted from the HOMER component database.

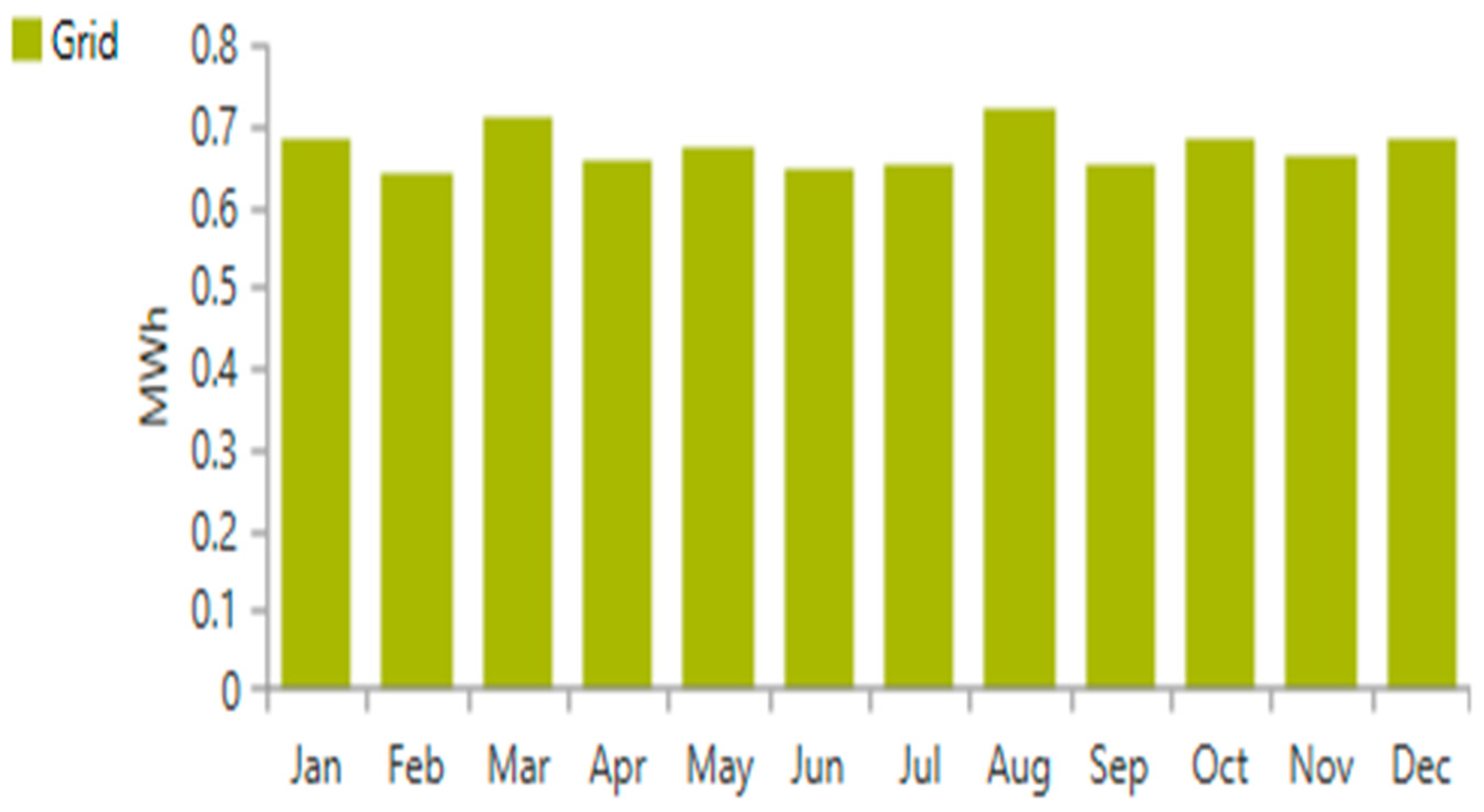

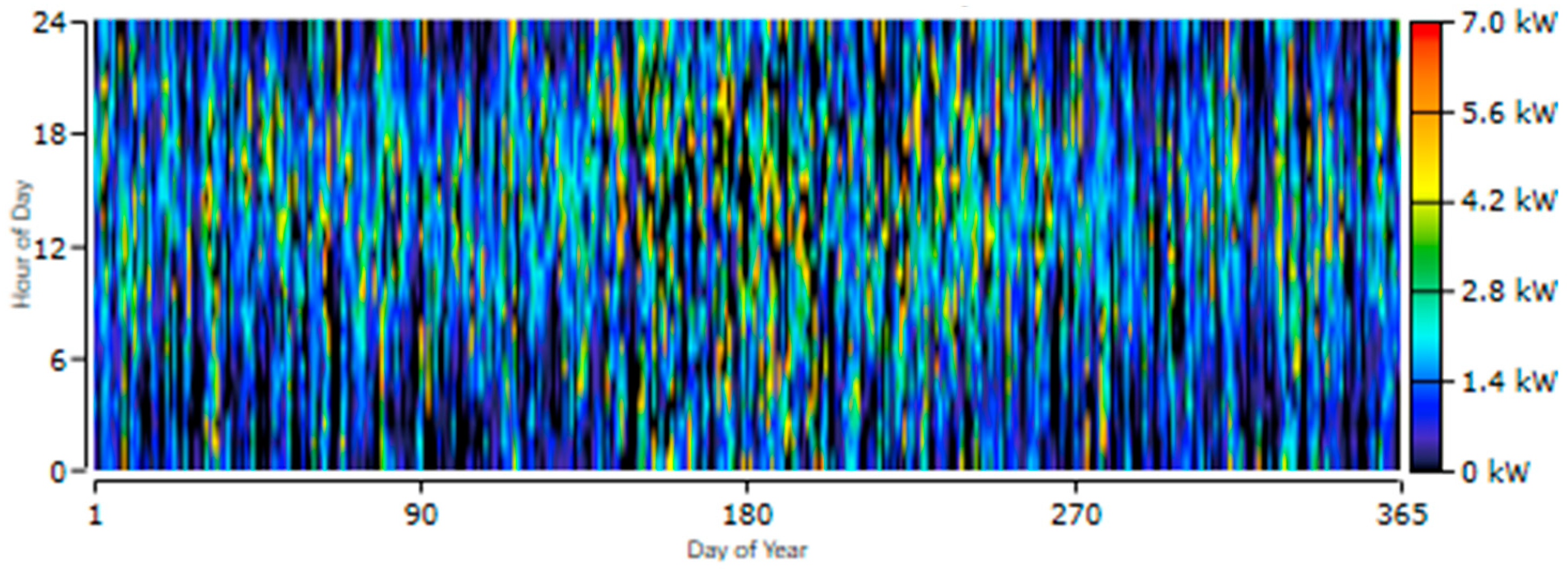

Hourly solar irradiance and wind-speed data were sourced from Kuwait’s Meteorological Department, while EV charging load profiles were modelled based on typical residential charging behaviour. The simulated charging demand was approximately 22 kWh per day with a peak load of 7.98 kW, equivalent to charging a mid-sized EV battery of 36–40 kWh capacity. In this study, a constant hourly load profile was adopted in HOMER to represent the average daily charging energy demand of a single residential EV user. This simplification assumes uniform power consumption throughout the day, equivalent to a total of 22 kWh/day, as HOMER’s primary objective was to compare renewable configurations under identical energy demands. While this static load approach omits temporal variations in charging behaviour, it provides a baseline for economic comparison. Future work will incorporate time-varying load profiles reflecting actual residential charging patterns in Kuwait. All simulations were performed assuming Kuwait’s ambient climate conditions and a project lifetime of 25 years.

State of Charge (SoC) Assumptions for EV Batteries

In this study, the EV charging load was modelled in HOMER as a constant daily energy demand of 22 kWh/day with a peak power of 7.98 kW, equivalent to a single mid-sized EV battery capacity of 36–40 kWh. Although individual vehicle battery characteristics were not explicitly simulated, typical SoC operating limits were adopted based on manufacturer specifications for private EVs used in Kuwait.

Table 1 summarizes representative SoC limits for common vehicle categories considered when estimating daily charging energy.

These SoC ranges were used to ensure realistic charging energy demand and battery-health preservation assumptions consistent with standard EV operation [

31,

32]. Futurework may integrate detailed dynamic SoC modelling for multiple vehicle types to refine energy-management strategies within HOMER simulations.

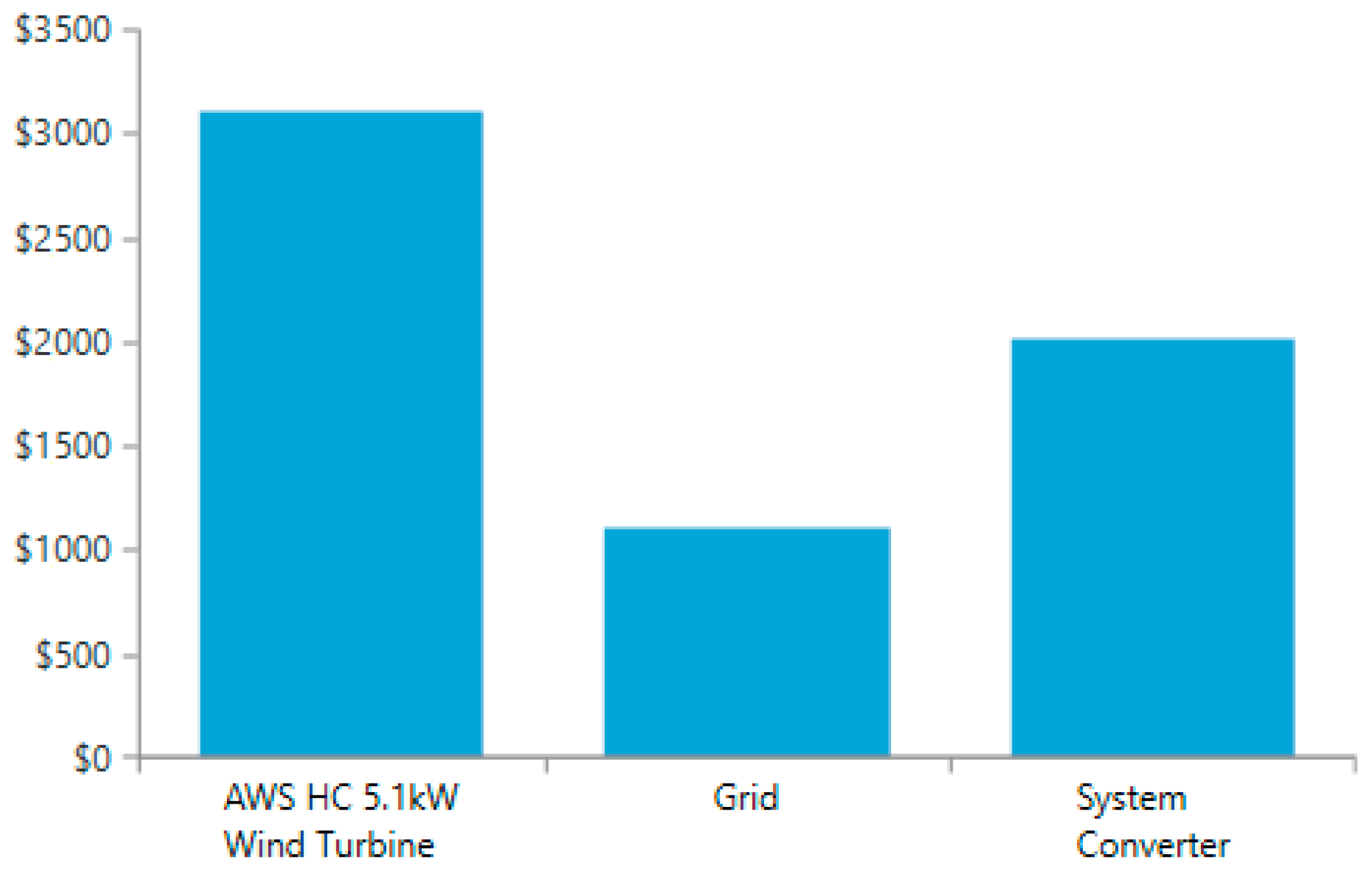

3.3. Component Technical and Economic Parameters

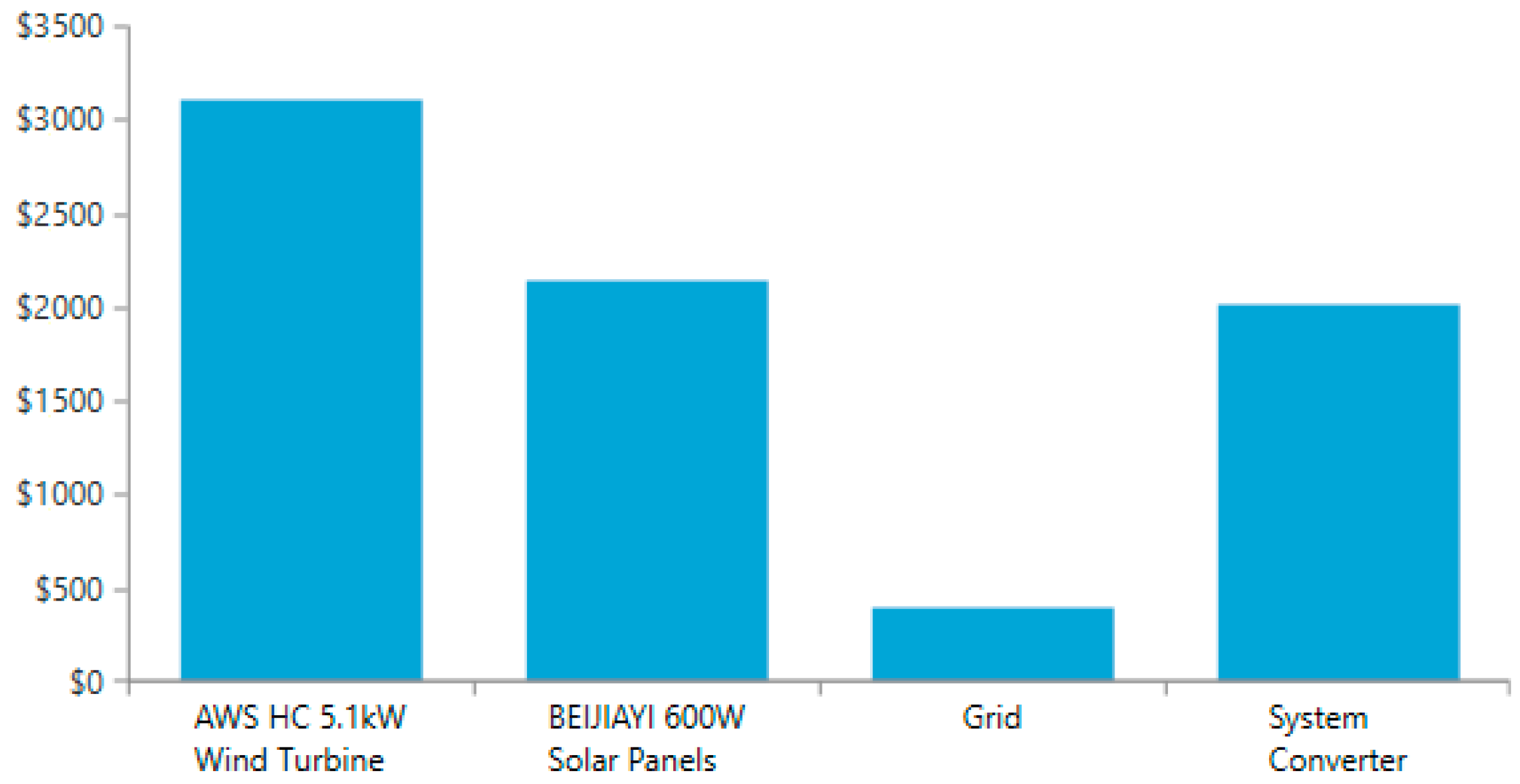

The HOMER simulation incorporated detailed techno-economic parameters for each system component based on manufacturer data and the HOMER component database.

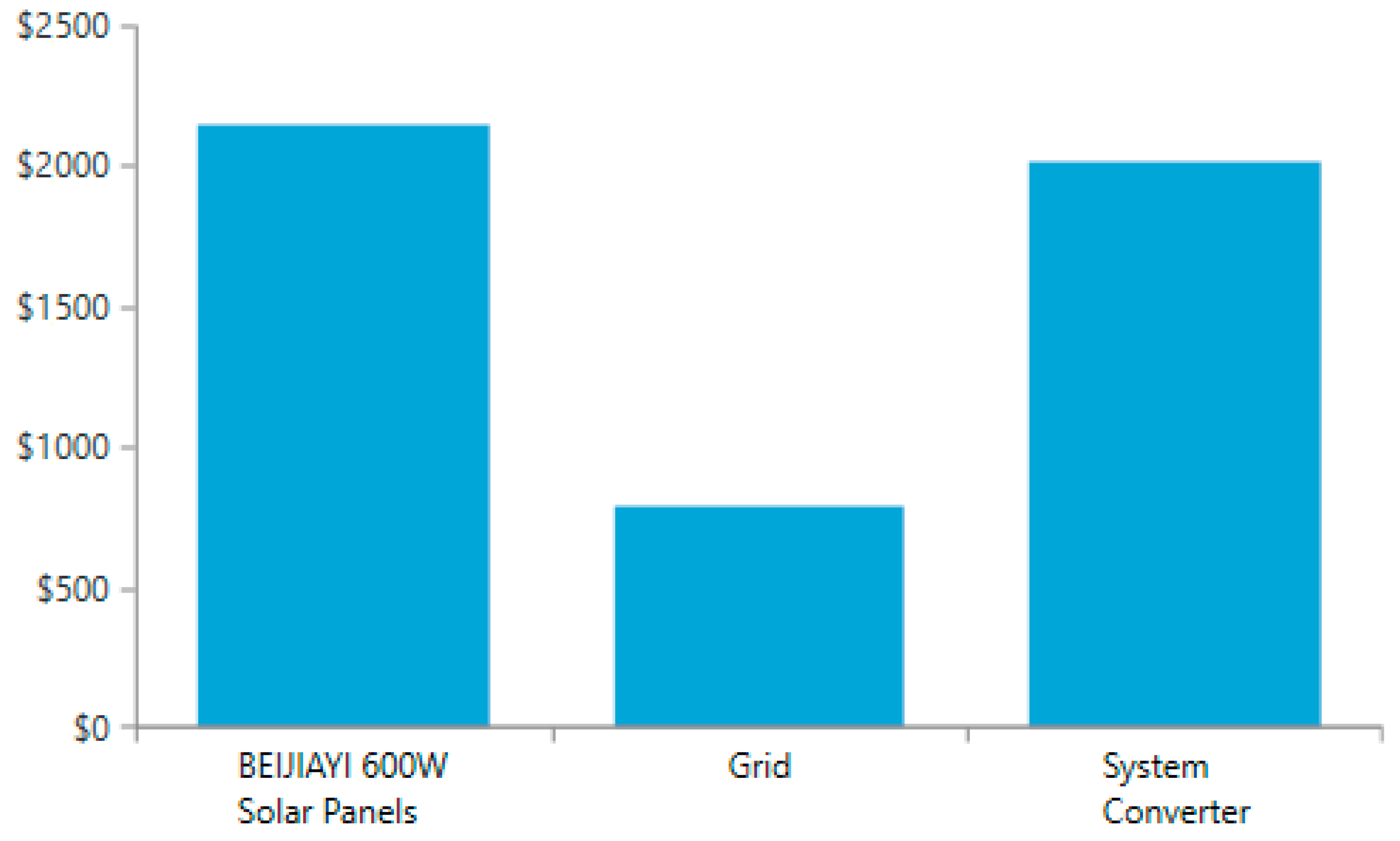

Table 2 summarizes the main technical and cost assumptions used for the BEIJIAYI 600 W solar PV modules, the AWS 5.1 kW wind turbine, and the 5 kW inverter. The BEIJIAYI monocrystalline PV modules were modelled with a nominal efficiency of 21.2%, temperature coefficient of −0.38%/°C, and a lifetime of 25 years.

The component ratings and system configurations summarized in

Table 2 were selected to represent realistic small-scale private EV charging applications in Kuwait, consistent with prior regional studies by Alazemi et al. [

23] and Alrajhi et al. [

24]. A 5 kW PV array and 5.1 kW wind turbine were chosen as typical residential-to-commercial scale capacities that balance technical feasibility, installation space, and investment cost. These capacities correspond to common single-phase inverter ratings (≈5 kW) used in grid-connected systems and ensure equitable comparison among the four configurations by maintaining identical total power ratings. The BEIJIAYI 600 W PV modules and AWS 5.1 kW turbine were selected because both models are commercially available, widely tested in similar arid climates, and included in the HOMER component database with validated performance parameters.

Limiting the study to these four configurations—grid-only, grid–solar, grid–wind, and grid–solar–wind—allows direct comparison of renewable contributions under identical load and climatic conditions while avoiding the confounding effects of differing system scales. This approach provides a fair and representative assessment of how each renewable source individually and jointly influences techno-economic and environmental performance for private EV charging scenarios in Kuwait.

These input parameters were used in HOMER to compute energy production, COE, and NPC. Because HOMER’s optimization results are highly sensitive to these variables, all values were validated against typical ranges reported in the recent literature for small-scale hybrid systems deployed in arid climates. The capital cost was set at USD 420/kW, with annual Operation and Maintenance (O&M) costs of USD 10/kW and a replacement cost equal to 80% of the initial investment. The AWS 5.1 kW horizontal axis wind turbine was assumed to operate between 3 m/s (cut-in) and 25 m/s (cut-out) with a rated speed of 12 m/s and a lifetime of 20 years. The turbine cost was set at USD 610/kW, with O&M costs of USD 25/kW/year and a replacement cost of 70% of the initial investment. The inverter efficiency was 95%, with a lifetime of 15 years and replacement cost of 60% of its initial capital value (USD 300/kW). These assumptions were drawn from HOMER’s internal database and verified against data from Alazemi et al. [

23] and Alrajhi et al. [

24]. To ensure model reproducibility and transparency,

Table 3 summarizes the key simulation input parameters used in HOMER, including efficiency assumptions, resource data sources, load details, grid parameters, and economic settings. These parameters define the baseline conditions for evaluating each system configuration and reflect Kuwait’s local climatic and economic context.

3.4. Consideration of Energy Storage

Although battery energy storage systems (BESSs) are widely recognized as effective complements to PV installations, they were intentionally excluded from this study. Kuwait’s grid-connected electricity tariff (≈0.03 USD/kWh) and high ambient temperatures make battery storage economically unattractive for small private charging stations. Preliminary HOMER test simulations with a 10 kWh lithium-ion battery increased the Net Present Cost by over 30% while offering negligible improvement in renewable fraction because the grid already provides full backup reliability. Therefore, this study focuses on grid-supported hybrid systems. Nevertheless, PV-plus-storage systems represent a promising future scenario, particularly if Kuwait adopts time-of-use pricing, feed-in tariffs, or net-metering incentives to enhance the economic viability of distributed storage.

3.5. Economic and Environmental Evaluation

For each configuration, HOMER calculated the following key performance metrics:

Total Capital Cost (USD);

Operating and Maintenance Cost (USD/year);

NPC;

COE;

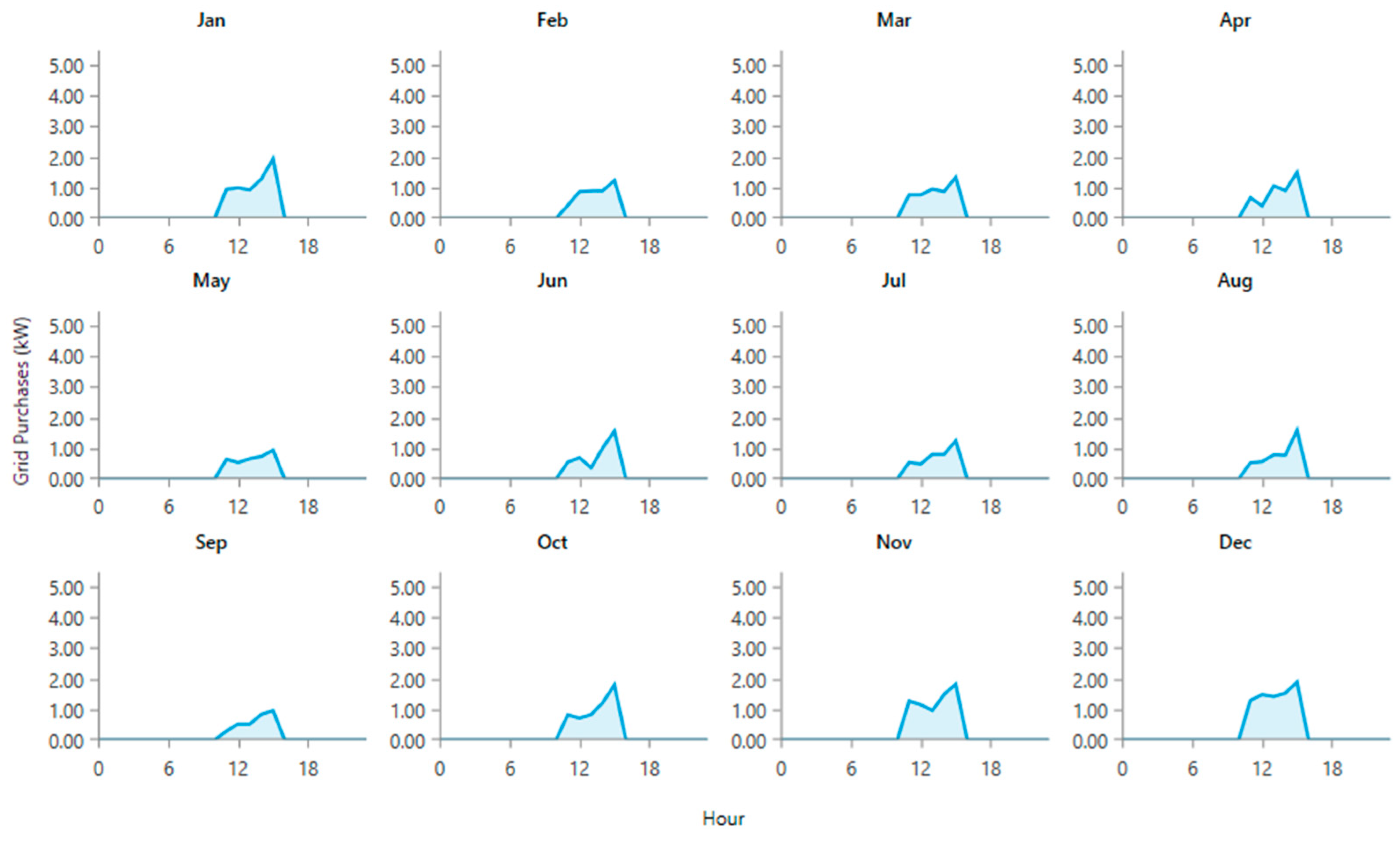

Annual Grid Purchases (kWh/year);

Renewable Fraction (%);

CO2 Emissions (kg/year).

A real discount rate of 5% was assumed, with the Kuwaiti electricity tariff and component pricing data reflecting 2025 market conditions. CO2 emissions were estimated using HOMER’s built-in emission factors for Kuwait’s grid mix, dominated by oil and natural gas combustion.

3.6. Sensitivity Analysis

To evaluate system robustness under changing environmental and economic conditions, a sensitivity analysis was conducted. Key parameters varied included

Solar radiation intensity (±10% of baseline values);

Wind-speed variation (±15%);

PV and turbine capital costs (±20%);

Discount rate (3–7%).

This analysis assessed how fluctuations in renewable resource availability and economic conditions affect the NPC, COE, and renewable fraction, thereby identifying the most resilient configuration for Kuwait’s conditions.

3.7. Study Objectives

The primary objectives of this study are to

Evaluate the technical and economic feasibility of integrating renewable energy sources—solar PV and wind turbines—into private EV charging stations in Kuwait;

Compare four grid-connected configurations (grid-only, grid–solar, grid–wind, and grid–solar–wind) in terms of energy output, cost, and emissions;

Quantify the potential reduction in grid dependency and carbon emissions achieved through renewable integration;

Identify the most cost-effective and environmentally sustainable configuration suitable for Kuwait’s climatic and economic conditions;

Provide practical recommendations to support Kuwait’s Vision 2030 goals for renewable energy expansion and sustainable transportation.

6. Discussion

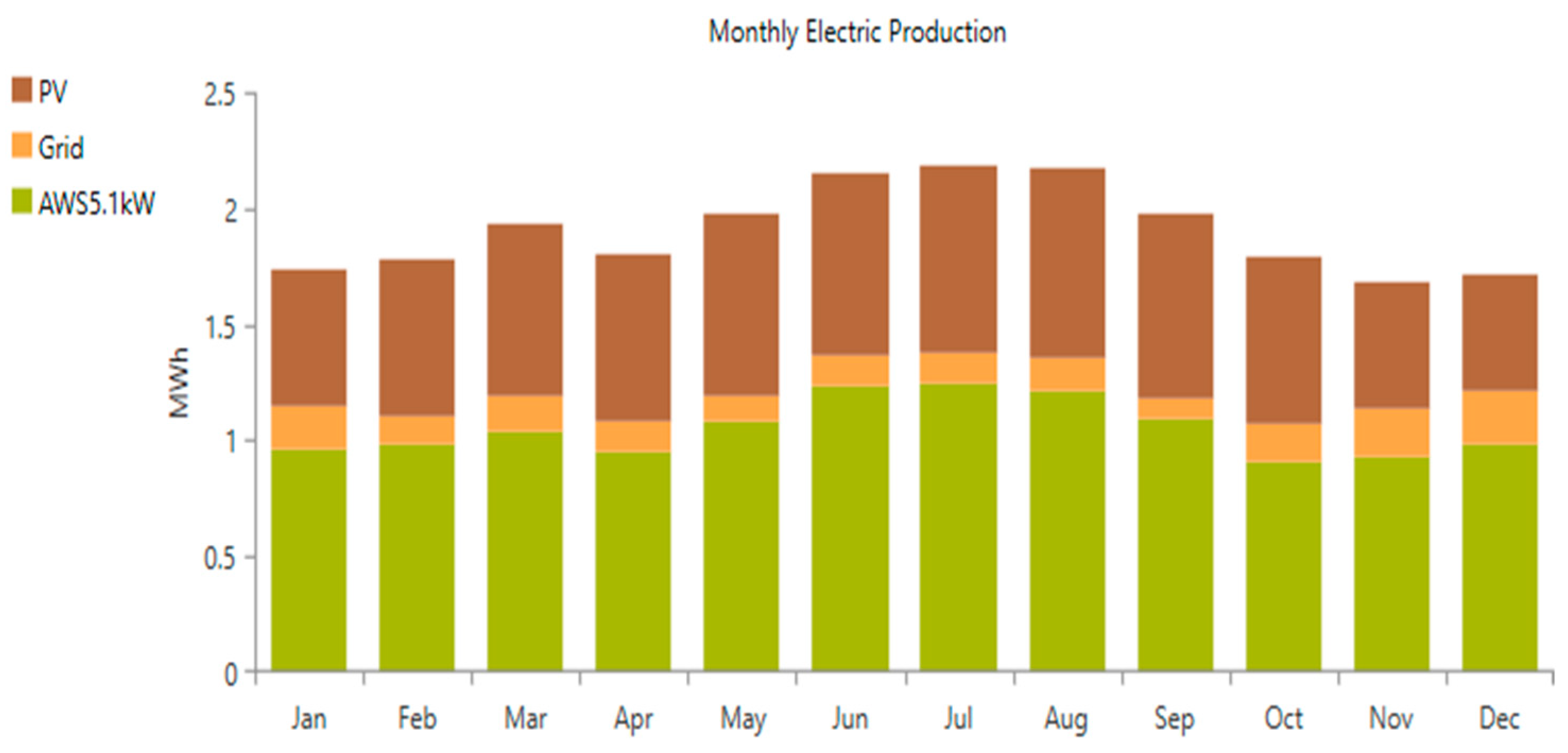

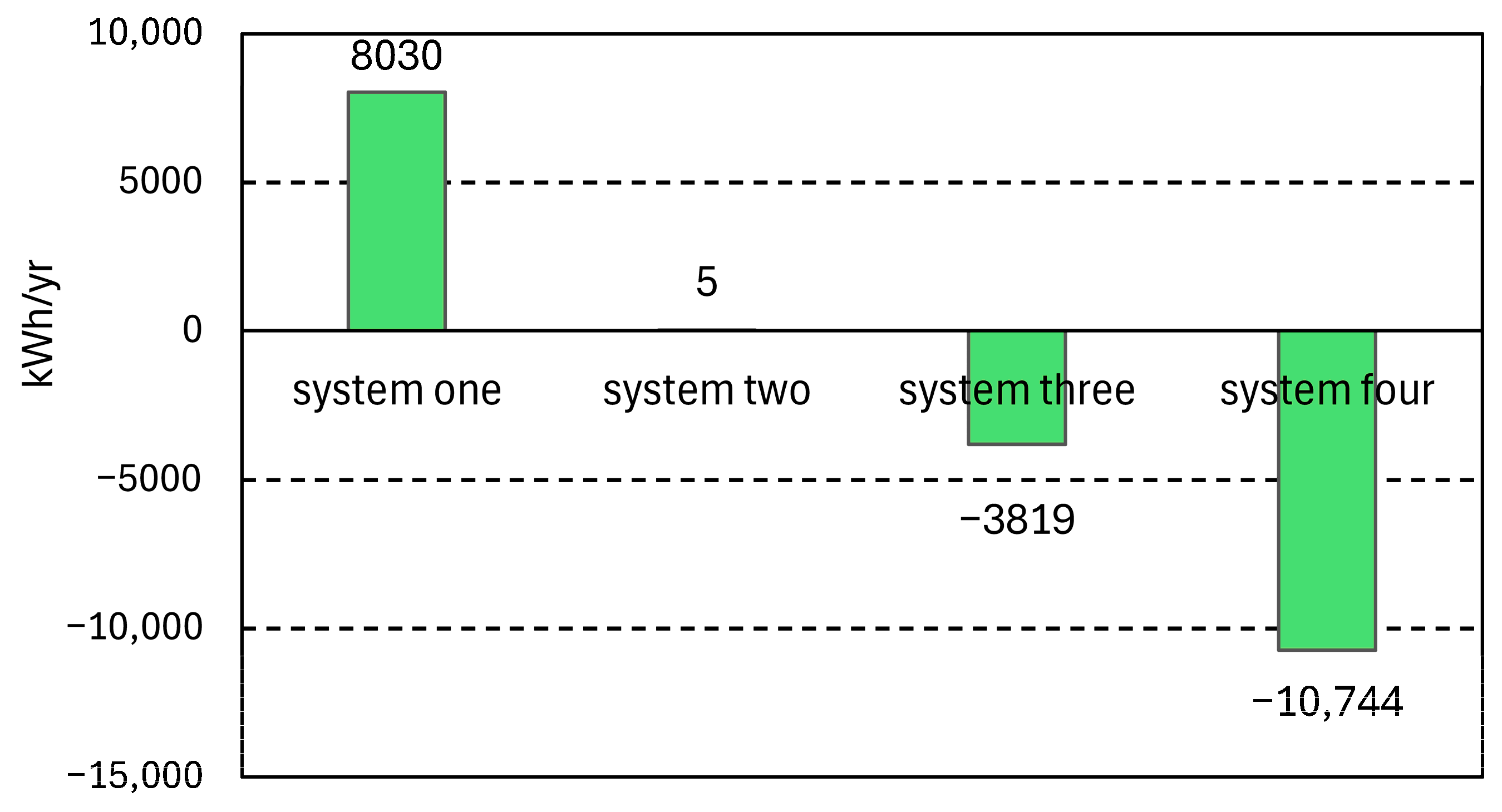

The simulation results clearly demonstrate that integrating renewable energy sources—particularly through hybrid solar–wind configurations—offers substantial economic and environmental advantages over conventional grid-only systems. The grid–solar–wind hybrid configuration (System 4) achieved the best overall performance, with a renewable fraction of approximately 78%, minimal grid dependence, and the lowest life-cycle cost among all simulated systems. This finding reinforces the growing consensus that hybridization of renewable sources provides a viable pathway toward sustainable energy generation in regions with complementary solar and wind resources.

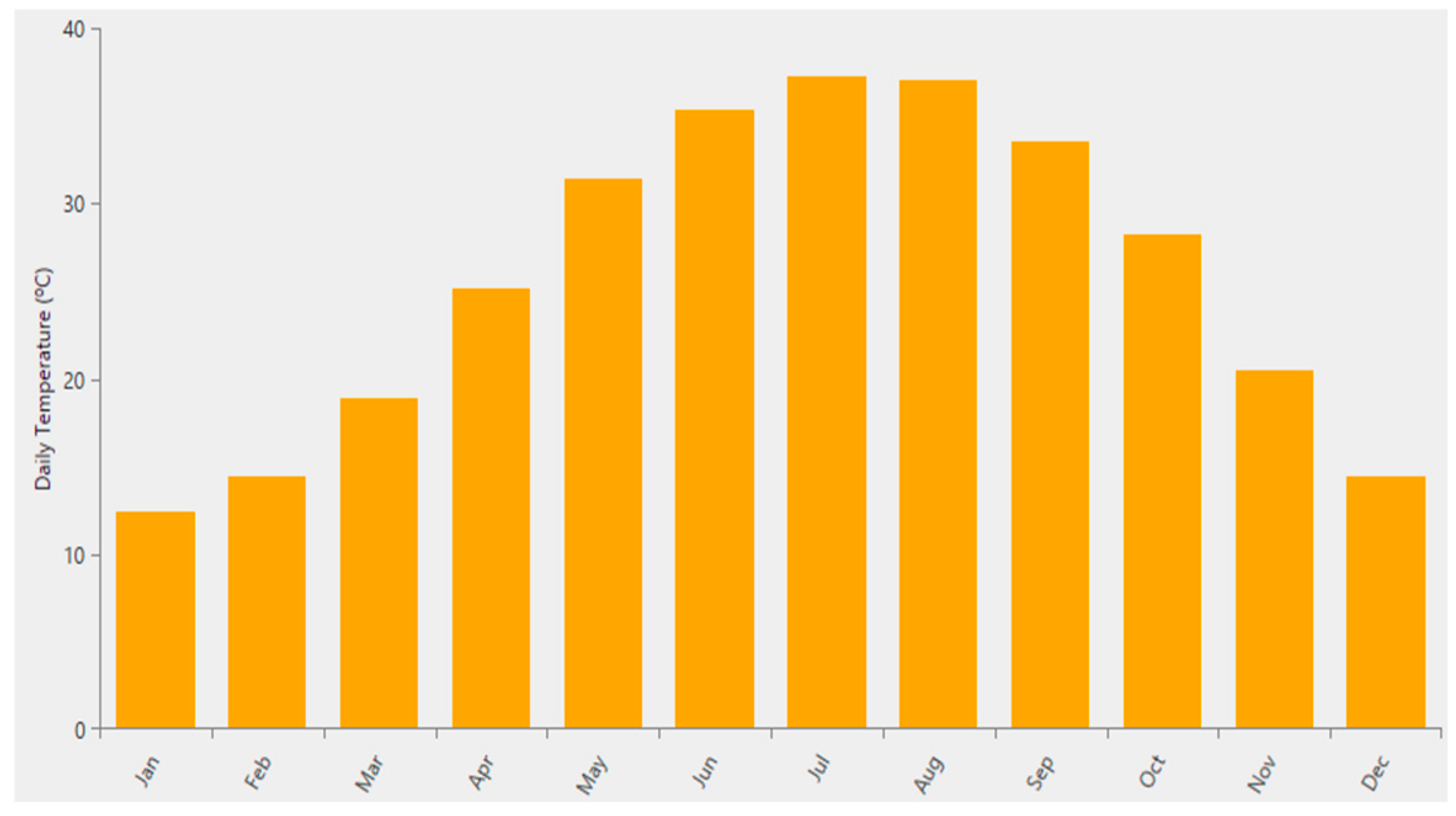

Although Kuwait experiences its highest solar irradiance levels during June and July, the PV system’s power output during these months is slightly lower than expected. This counterintuitive result arises from the temperature sensitivity of photovoltaic modules. When cell temperatures exceed the standard test condition (25 °C), PV efficiency declines due to increased semiconductor resistance and reduced open-circuit voltage. For the BEIJIAYI 600 W monocrystalline modules used in this study, the temperature coefficient is approximately −0.38%/°C, meaning that each 10 °C rise in temperature can reduce output power by about 3.8%. During Kuwait’s summer months, ambient temperatures often exceed 45 °C, and the corresponding cell temperature can surpass 65–70 °C, leading to 10–15% output derating despite peak solar irradiance. This effect explains the observed decrease in summer PV generation compared with transitional months such as April and October. These findings highlight the importance of integrating passive cooling measures, proper ventilation, and periodic cleaning to sustain PV performance in high-temperature desert environments.

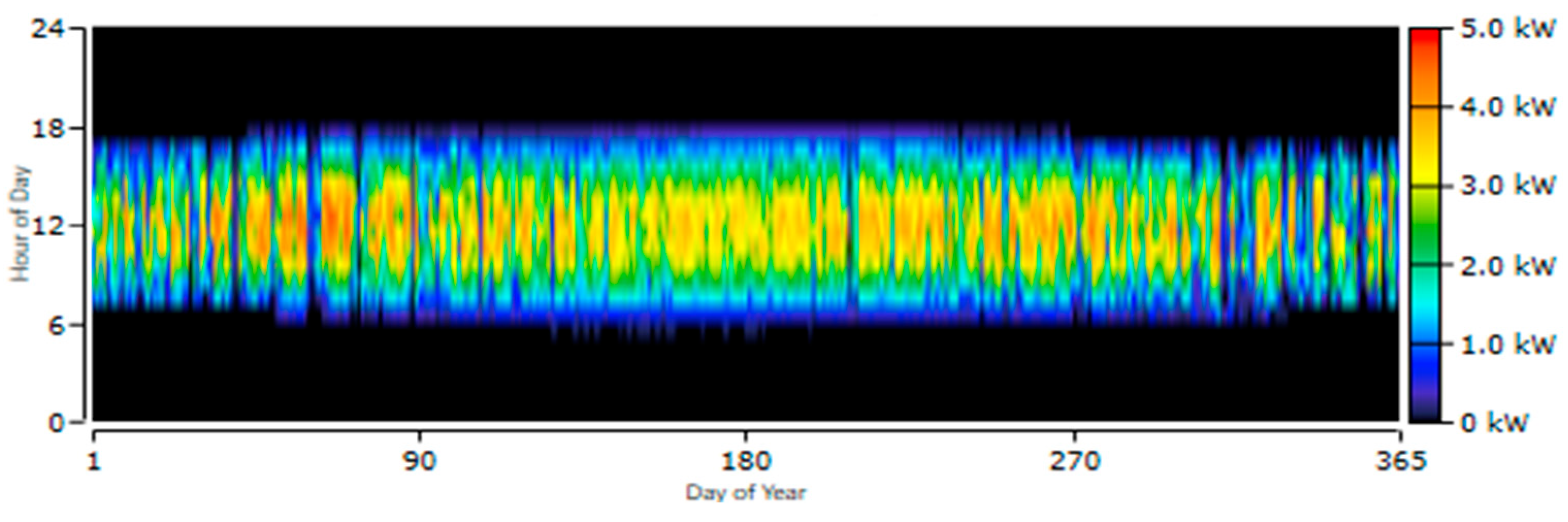

From a technical standpoint, the combination of solar PV and wind energy effectively compensates for each resource’s intermittency. Kuwait’s climatic pattern—characterized by high solar irradiance during the summer and strong winds in the late afternoon and evening—creates ideal conditions for hybrid operation. The diurnal and seasonal complementarity ensures continuous renewable electricity supply, even in the absence of large-scale storage systems. Such stability is critical for EV charging stations, where uninterrupted operation directly affects user confidence and adoption rates.

While both solar and wind resources in Kuwait exhibit seasonal peaks during the summer, their true complementarity is more pronounced on a diurnal (24 h) timescale. Solar PV generation occurs exclusively during daytime hours, typically between 06:00 and 18:00 h, whereas wind speeds in Kuwait often intensify during the late afternoon, evening, and early-morning hours, sustaining generation when solar output drops. This day–night alternation enables the hybrid system to provide a smoother total power profile and reduce reliance on grid energy. Although the present analysis focused on monthly averages, HOMER’s hourly data confirm that wind production extends overnight, complementing the solar resource within each daily cycle. Future work will include explicit hourly generation plots for hybrid systems to visualize this diurnal complementarity and to quantify its contribution to system reliability.

Beyond the dynamic behaviour of charging loads, aligning the system configuration with realistic use scenarios is essential for assessing practical feasibility. In this study, the simulated daily load of 22 kWh and peak demand of 7.98 kW represent a typical single residential EV charging point corresponding to one mid-sized electric vehicle with a 36–40 kWh battery. In an actual multi-parking installation, aggregate load would scale proportionally with the number of serviced vehicles, and concurrent charging sessions could shift the overall demand profile toward the evening peak between 18:00 and 22:00 h, coinciding with residents’ household electricity peaks. Conversely, off-peak or overnight charging (22:00–06:00 h) would coincide with grid valley periods, reducing tariff costs and stress on the distribution network. Different EV models also exhibit distinct charging powers—from 3.7 kW for plug-in hybrids to over 22 kW for fast home chargers—which influence both instantaneous load and total energy demand. Incorporating these scenario variations in future modelling would enable a more accurate evaluation of infrastructure sizing, energy-management strategies, and tariff optimization for Kuwait’s residential charging sector.

In addition to the resource complementarity between solar and wind power, understanding the dynamic characteristics of private EV charging loads is essential for optimal system design. Private home charging in Kuwait typically follows evening demand peaks between 18:00 and 22:00 h, when most users return from work. This timing often coincides with reduced solar output, creating a temporal mismatch between renewable generation and consumption. Conversely, daytime charging events, especially in commercial or institutional settings, better align with solar PV production. Seasonal variations also influence charging behaviour, with higher air-conditioning loads and increased driving activity during summer months contributing to elevated electricity demand. By correlating these temporal load patterns with renewable resource availability, the study underscores the importance of integrating smart charging strategies, time-of-use pricing, and potential V2G functionality to enhance system flexibility. Such adaptive load-management mechanisms can dynamically balance renewable generation and charging demand, reducing grid dependency and improving overall energy efficiency.

The economic assessment highlights that, although the hybrid configuration entails the highest initial capital investment (USD 7662), it delivers superior long-term cost savings through reduced reliance on grid electricity and lower operating costs. The NPC and COE results confirm that hybrid systems can achieve a competitive COE compared with traditional grid-only setups when analyzed over a 25-year project lifetime. These findings are consistent with earlier studies in the GCC region that emphasize the cost-effectiveness of hybrid renewable systems for distributed generation applications [

23,

24].

To better illustrate the comparative performance of the systems, the numerical results can be expressed as relative improvements over the grid-only baseline. The grid–solar configuration reduced the NPC by approximately 35%, while the grid–wind system achieved a reduction of around 20%. The fully hybrid grid–solar–wind system further lowered the NPC by nearly 55% compared with the grid-only case. Similarly, the LCOE decreased from 0.0486 USD/kWh in the baseline to 0.017 USD/kWh in the hybrid system, representing a 65% reduction in lifetime energy cost. In terms of environmental impact, the hybrid system achieved a 78% reduction in annual CO2 emissions relative to the grid-only setup. These percentage-based comparisons confirm that integrating both renewable sources not only minimizes long-term energy costs but also substantially enhances environmental performance.

In terms of environmental performance, the grid–solar–wind system achieved a remarkable reduction of approximately 7027 kg CO2 per year, equivalent to offsetting more than 130 barrels of oil annually. This level of mitigation directly supports Kuwait’s national sustainability agenda, which aims to cut carbon emissions and diversify the energy mix under Kuwait Vision 2030. The transition from fossil fuel-dominated power generation toward renewable integration not only reduces environmental impact but also enhances national energy security by decreasing dependence on oil-fired electricity production.

Furthermore, the analysis demonstrates that grid-connected renewable systems are more economically and operationally feasible than standalone off-grid options in Kuwait’s context. The availability of the national grid as a backup mitigates intermittency risks, while net-metering or feed-in mechanisms (if implemented) could allow surplus renewable energy export, improving system profitability. Future expansion of Kuwait’s smart grid infrastructure would further enable dynamic load balancing and integration of V2G technologies, enhancing system flexibility and resilience.

Despite the promising results, certain challenges remain. High ambient temperatures can reduce PV efficiency, and dust accumulation may require regular maintenance to sustain optimal performance.

Although Kuwait’s climate offers abundant solar and wind resources, the extreme environmental conditions necessitate technical adaptation to maintain long-term system reliability. High summer temperatures, sandstorms, and high humidity can degrade PV module efficiency and mechanical integrity over time. Therefore, mitigation measures such as passive air cooling, elevated mounting, and the use of anti-soiling or hydrophobic coatings are essential to sustain PV performance. For wind turbines, employing corrosion-resistant materials, sealed bearings, and optimized yaw control can improve durability under dusty, high-wind conditions. Additionally, weather-adaptive control algorithms and real-time monitoring should be integrated to dynamically adjust power conversion efficiency and ensure stable operation under varying irradiance and wind conditions. These adaptive design and operational strategies enhance overall system resilience and extend component lifespan in Kuwait’s harsh desert environment.

Moreover, while small-scale wind turbines perform effectively in open desert areas, urban noise restrictions and zoning regulations could limit installation in dense residential zones. These constraints highlight the importance of site-specific design optimization and policy support to scale renewable-based EV infrastructure effectively.

Beyond the numerical findings, the results highlight broader implications for renewable energy integration and EV-infrastructure planning in arid regions. The hybrid system’s high renewable fraction (≈78%) demonstrates that decentralized charging stations can operate reliably with minimal grid dependence, provided that system sizing is optimized for Kuwait’s distinctive diurnal and seasonal resource variations. Similar hybrid-system studies in Saudi Arabia and the UAE reported renewable contributions of 70–80% under comparable conditions [

24,

25] validating the technical robustness of such configurations in desert climates. The findings also emphasize that energy diversification and infrastructure decentralization can substantially enhance energy security. By reducing reliance on grid imports, private hybrid EV charging stations could relieve stress on Kuwait’s electricity network during summer peaks—aligning with Vision 2030’s decarbonization targets and demand-management goals. The projected CO

2 emission reduction of more than 7 tons per year per station may appear modest, but large-scale deployment across thousands of charging sites could yield a significant cumulative impact on national emissions.

From an economic standpoint, the declining cost of PV modules and small wind turbines (<1000 USD/kW) further strengthens the financial attractiveness of hybrid systems. The LCOE achieved in this study (0.017 USD/kWh) is substantially lower than Kuwait’s residential electricity tariff, confirming cost competitiveness even without subsidies. However, policy instruments such as net-metering, feed-in tariffs, and low-interest green financing could accelerate private investment in renewable-based EV infrastructure.

Finally, it must be noted that the present analysis assumes ideal equipment performance and simplified load behaviour. Future research should incorporate dynamic charging load profiles, battery-storage integration, and hourly meteorological variability to capture real-world operational dynamics more precisely. Incorporating these refinements would provide policymakers and investors with even stronger evidence for large-scale implementation.

Overall, this study establishes that hybrid renewable energy systems can significantly improve the economic viability, environmental sustainability, and energy independence of EV charging stations in Kuwait. The outcomes provide a strong foundation for policy formulation, investment decisions, and pilot implementation projects, guiding Kuwait toward a more diversified and low-carbon energy future.

7. Conclusions and Recommendations

This study conducted a comparative techno-economic and environmental analysis of four grid-connected configurations—grid-only, grid–solar, grid–wind, and grid–solar–wind—for powering private EV charging stations in Kuwait. Using HOMER Pro simulation, each configuration was evaluated for total cost, renewable energy contribution, and carbon emission reduction under local climatic conditions.

The results confirmed that hybridization of renewable sources substantially improves both economic and environmental performance. The grid–solar–wind configuration demonstrated the highest renewable fraction (≈78%), minimal grid dependence, and the lowest life-cycle cost despite its higher capital investment. It achieved an annual CO2 emission reduction of approximately 7027 kg, outperforming all other systems and reinforcing the potential of hybrid renewable systems to meet Kuwait’s clean-energy objectives.

Conversely, the grid-only configuration, while least expensive initially, exhibited the greatest environmental impact and full reliance on fossil fuel electricity. The solar-assisted system reduced grid usage by more than 50%, whereas the wind-assisted system provided seasonal support and moderate savings.

Overall, the findings highlight that hybrid solar–wind systems offer the most practical and sustainable pathway for EV charging infrastructure in Kuwait, balancing cost-effectiveness, reliability, and carbon mitigation. These results are directly aligned with the goals of Kuwait Vision 2030, which emphasizes diversification of the national energy mix and the transition toward low-carbon development.

To build on this work, several recommendations are proposed:

Pilot Deployment: Implement small-scale hybrid solar–wind EV charging stations in strategic urban and industrial zones (e.g., Sulabiya and Abdullah Al-Mubarak) to validate field performance and refine technical parameters.

Policy Incentives: Establish feed-in tariffs, net-metering schemes, or investment subsidies to encourage private-sector participation in renewable-powered EV infrastructure.

Smart Grid Integration: Develop V2G and demand-response frameworks to enhance grid flexibility and enable surplus renewable-energy export.

Environmental Monitoring: Introduce dust-mitigation and PV-cooling technologies to improve long-term system efficiency under Kuwait’s desert climate.

Future Research: Extend the analysis to include energy-storage systems, life-cycle cost assessment, and multi-site comparisons to optimize hybrid configurations for large-scale implementation.

By adopting these measures, Kuwait can accelerate its progress toward a sustainable transportation ecosystem, reduce dependence on oil-based electricity, and demonstrate regional leadership in renewable energy integration for EV charging.