Abstract

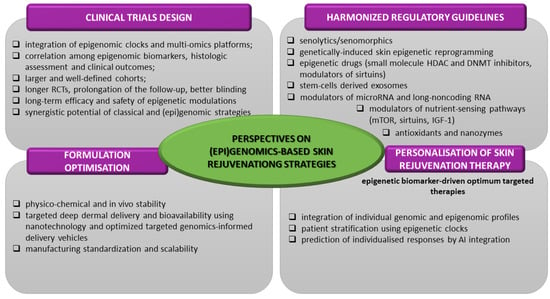

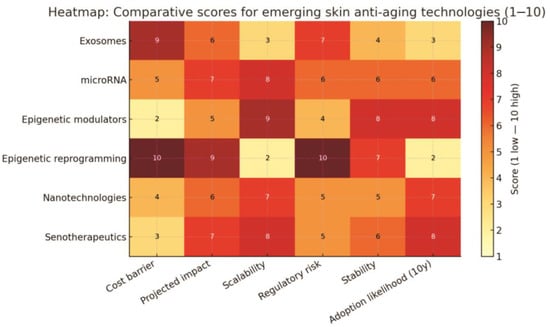

This article aims to point out new perspectives opened by genomics and epigenomics in skin rejuvenation strategies which target the main hallmarks of the ageing. In this respect, this article presents a concise overview on: the clinical relevance of the most important clocks and biomarkers used in skin anti-ageing strategy evaluation, the fundamentals, the main illustrating examples preclinically and clinically tested, the critical insights on knowledge gaps and future research perspectives concerning the most relevant skin anti-ageing and rejuvenation strategies based on novel epigenomic and genomic acquisitions. Thus the review dedicates distinct sections to: senolytics and senomorphics targeting senescent skin cells and their senescent-associated phenotype; strategies targeting genomic instability and telomere attrition by stimulation of the deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) repair enzymes and proteins essential for telomeres’ recovery and stability; regenerative medicine based on mesenchymal stem cells or cell-free products in order to restore skin-resided stem cells; genetically and chemically induced skin epigenetic partial reprogramming by using transcription factors or epigenetic small molecule agents, respectively; small molecule modulators of DNA methylases, histone deacetylases, telomerases, DNA repair enzymes or of sirtuins; modulators of micro ribonucleic acid (miRNA) and long-non-coding ribonucleic acid (HOTAIR’s modulators) assisted or not by CRISPR-gene editing technology (CRISPR: Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats); modulators of the most relevant altered nutrient-sensing pathways in skin ageing; as well as antioxidants and nanozymes to address mitochondrial dysfunctions and oxidative stress. In addition, some approaches targeting skin inflammageing, altered skin proteostasis, (macro)autophagy and intercellular connections, or skin microbiome, are very briefly discussed. The review also offers a comparative analysis among the newer genomic/epigenomic-based skin anti-ageing strategies vs. classical skin rejuvenation treatments from various perspectives: efficacy, safety, mechanism of action, evidence level in preclinical and clinical data and regulatory status, price range, current limitations. In these regards, a concise overview on senolytic/senomorphic agents, topical nutrigenomic pathways’ modulators and DNA repair enzymes, epigenetic small molecules agents, microRNAs and HOTAIRS’s modulators, is illustrated in comparison to classical approaches such as tretinoin and peptide-based cosmeceuticals, topical serum with growth factors, intense pulsed light, laser and microneedling combinations, chemical peels, botulinum toxin injections, dermal fillers. Finally, the review emphasizes the future research directions in order to accelerate the clinical translation of the (epi)genomic-advanced knowledge towards personalization of the skin anti-ageing strategies by integration of individual genomic and epigenomic profiles to customize/tailor skin rejuvenation therapies.

1. Skin Ageing: Classification and Main Hallmarks

Skin ageing is a multifactorial process mediated by both intrinsic factors (such as time, genetics, hormones) and extrinsic environmental factors (i.e., lifestyle, nutrition, pollution, drugs, UV exposure) which accelerate the chronological (intrinsic/calendar) ageing [1,2]. Types of ageing including those referring to skin are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Types of age(ing).

The main physiological and histological changes in aged skin phenotype might be described as follows: reduced elasticity and hydration; formation of wrinkles; sagging; itching; significant thinning and atrophy of the dermis and epidermis; altered barrier function; increased vulnerability to injury and disease; delayed wound healing; subcutaneous fat loss; uneven pigmentation; flattening of the epidermis–dermal connection; declining proliferative potential of the epidermal stem cells; collagen fragmentation and loss (approximately 1% yearly decline in collagen content in the dermis caused by parallel reduction in synthesis and increased degradation of existing collagen); disruption of the elastic fibre network; reduction in glycosaminoglycans and proteoglycans; impaired cell division of the melanocytes, of the cells in the germinative layer and those located in epidermis [2,10,11,12,13,14]. Similar genetic, biochemical and cellular disfunctions are involved in the visible signs of both chronologically aged and photoaged skin.

Intrinsic ageing and photoageing both share mechanisms like oxidative stress, senescence, and extracellular matrix (ECM) degradation, but photoageing accelerates these processes via UV-specific pathways involving stimulation of the matrix metalloproteases (MMP) activation and inflammation. Chronic localized inflammation in photoaged skin, with elevated cytokine expression (interleukin IL-6, tumour necrotic factor TNF α) and reactive oxygen species (ROS), contrasts with the low-grade, systemic inflammageing observed in chronological ageing; in addition, deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) damage and cellular senescence accumulate more rapidly in UV-exposed skin areas [15]. Photoaged skin exhibits severe clinical signs (deep wrinkles, pigmentation, vascular changes) and histological alterations (solar elastosis, collagen fragmentation and degradation, faster ECM decline) that exceed those seen in chronological ageing [15,16,17]. Comparative insights on various features of the intrinsic aged and photoaged skin are illustrated in Table 2.

Table 2.

Comparative insights into intrinsic aged versus photo-aged skin.

The main hallmarks of accelerated skin ageing are: (a) cellular senescence and the emergence of the Senescence-Associated Secretory Phenotype (SASP) associated with the accumulation of the senescent fibroblasts in the dermis, which are responsible for collagen degradation by the secreted matrix metalloproteases (MMP) and for secretion of pro-inflammatory factors; (b) genomic instability, due to the increased accumulation of DNA damage, mutations and genomic rearrangements; (c) telomere attrition (the gradual shortening of telomeres limiting the regeneration capacity); (d) epigenetic changes, like: DNA methylation, histone modifications, non-coding ribonucleic acid (RNA) regulation and heterochromatin-modifying gene expression patterns; (e) stem cell exhaustion, affecting tissue repair and renewal; (f) dysregulation of nutrient-sensing pathways, like mammalian target of rapamycin, (mTOR), insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) and IGF-1 signalling (IIS) pathway, AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK, an energy-sensing enzyme), which alter metabolism and energy balance; (g) mitochondrial dysfunction, leading to impaired energy production and increased oxidative stress; (h) altered proteostasis, with the accumulation of misfolded proteins and Advanced Glycation End Products (AGEs), which is highly correlated to cellular senescence and plays a role in photoageing due to abnormal aggregation of glycated elastin fibres; (i) inflammageing; (j) altered intercellular communication and disconnectivity of the transcriptional networks; (k) microbiome disturbance; (l) compromised macro-autophagy [10,18,19,20,21,22].

Personalized and effective topical and systemic skin anti-ageing and rejuvenation strategies should target the above mentioned cellular, metabolic and (epi)genomic hallmarks, combined with minimally invasive procedures and nanotechnology, and are currently focused especially on: senotherapeutics (senolytics and senomorphics); regenerative medicine in order to restore skin-resided stem cells, based on mesenchymal stem cells or cell-free products (platelet-rich fibrin, autologous conditioned serum); epigenetic partial reprogramming; various epigenetic drugs (DNA methyltransferase inhibitors, histone deacetylase inhibitors, microRNAs, modulators of sirtuins and of long-non-coding RNA HOTAIR, telomeric repeat binding factor 2 TRF2); antioxidants (resveratrol, topical or oral use of various polyphenol-rich plants); pharmacological activation of autophagy; restoration of mitochondrial integrity essential for metabolism homeostasis [11,19,20,23,24,25].

The aim of this review is to concisely discuss: the clinical relevance of the most important clocks and biomarkers used in skin anti-ageing strategy evaluation, the fundamentals, the main illustrating examples preclinically and clinically tested, the critical insights on knowledge gaps and future research perspectives concerning the most relevant skin anti-ageing and rejuvenation strategies based on novel epigenomic and genomic acquisitions. Thus, the review dedicates distinct sections to senotherapeutics; stimulators of the DNA repair enzymes and of the proteins essential for telomeres’ recovery and stability; regenerative medicine based on stem-cells exosomes, genetically and chemically induced skin epigenetic reprogramming, modulators of microRNA and long-non-coding RNA (HOTAIR’s modulators) assisted or not by CRISPR-gene editing technology (CRISPR: Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats), small molecule modulators of DNA methylases, histone acetylases, telomerases or of sirtuins, as well as modulators of the most relevant altered nutrient-sensing pathways and of mitochondrial dysfunctions and oxidative stress levels. The possibilities to positively influence skin inflammageing, proteostasis, (macro)autophagy and intercellular connections or skin microbiome, are also very briefly presented. Moreover, this review points out a comparative analysis among the newer genomic/epigenomic-based skin anti-ageing strategies vs. classical skin rejuvenation treatments from various perspectives: efficacy, safety, mechanism of action, price range, current limitations, evidence level in preclinical and clinical data and regulatory status. In these regards, a concise overview on senolytic/senomorphic agents, topical nutrigenomic pathways’ modulators and DNA repair enzymes, epigenetic small molecules agents, microRNAs and HOTAIRS’s modulators, assisted or not by CRISPR gene-editing technology, is illustrated in comparison to classical approaches such as tretinoin and peptide-based cosmeceuticals, topical serum with growth factors, intense pulsed light, laser and microneedling combinations, chemical peels, botulinum toxin injections, dermal fillers. Finally, this review emphasizes the future research directions in order to accelerate the clinical translation of the (epi)genomic-advanced knowledge towards personalization of the skin anti-ageing strategies by integration of individual genomic and epigenomic profiles to customize/tailor skin rejuvenation therapies.

2. Clocks and Biomarkers in Skin Anti-Ageing Strategy Evaluation: Description and Clinical Relevance

Chronological age is fixed and does not reflect skin health; biological age is more insightful for assessing rejuvenation [3]. The main biomarkers for estimating the biological age and assessment of anti-ageing interventions efficacy are integrated into epigenetic and non-epigenetic clocks, comprising DNA methylation-based biomarkers (epigenetic clock); analysis of key age-associated genes; cellular ageing hallmarks (SASP, altered macromolecules, genomic instability and shortened telomeres; senescence-associated heterochromatin foci SAHF) [26,27,28].

Among the skin-ageing biomarkers, DNA methylation-based (DNAm) epigenetic clocks, developed by regression models based on the increasing relationship with age of chosen groups of CpGs, are considered the gold standard in primary and accurate candidate metric at the molecular level and are highly reproducible and validated by most studies, both in ageing prediction and in skin rejuvenation research [29,30,31]. Such “epigenetic clocks” based on CpGs profile in skin fibroblasts, keratinocytes, endothelial cells, as well as in blood samples, would enable a better prediction and personalization of the skin rejuvenating topical and systemic senotherapeutics [29,32,33,34].

Based on a large-scale epigenome-wide association study (EWAS), altered DNA methylation patterns at CpG sites near ECM genes, such as elastin (ELN), lysyl oxidase (LOX), collagen type VIII alpha 1 chain (COL8A1), and matrix metallopeptidase 3 (MMP3) genes, have been associated with perceived/visibly aged skin [35]. These genes are interconnected within phenotypic/biological ageing of skin. The ELN gene encodes tropoelastin, an essential protein of the elastin fibres in the connective tissue. LOX encodes the enzyme responsible for crosslinking elastin and collagen fibres which strengthen ECM and play a key role in skin remodelling and wound healing. COL8A1 contributes to collagen synthesis and thus slows down the ageing process, whilst MMP3 catalyzes collagen degradation [34,36]. Boroni M. et al. have calculated skin-specific DNAm age based on the 2266 CpG sites within hundreds of cultured cells and human skin biopsies. Their model has enabled a highly accurate chronological age prediction, which is also sensitive to skin disorders, cell passage, or therapy with senotherapeutics. The tissue-specific DNAm age predictors are endowed with superior prediction power over the similar pan- or multi-tissue tests [36]. What remains to be further established is either the causal or the consequential relationship between DNAm profile and the skin ageing process/status. Initially regarded as a valuable tool to estimate chronological age at the molecular level, DNAm of biological samples has been recently reconsidered as a powerful tool to assess also the lifespan, longevity, the overall health status and mortality risk, due to its dependence both on time and additional factors, such as lifestyle and some genetic, inflammatory, metabolic and infectious disorders [34,35,36].

The epigenetic clocks are classified into generations, the first generation being mainly represented by Horvath clock, which is a universal clock detecting DNAm at 353 CpGs across tissues, without optimization for skin anti-ageing or short-term interventions [6]. Systemic epigenetic clocks (like GrimAge) are less useful for localized skin ageing evaluation but remain valuable in broader ageing-related drug development where skin is one of multiple targeted tissues [37]. The skin-optimized epigenetic clocks from second generation (e.g., Skin and Blood Clock, GrimAge, PhenoAge) and third generation (e.g., DunedinPACE, miRNA Skin Clock, Rayan Clock) provide measurable and sensitive biomarkers for skin-targeted interventions and they are most clinically valuable in dermatology and regenerative applications [4,5,6,26,27,28]. The Skin and Blood Clock is currently the most accurate skin-specific biological age tool, it provides the most clinically relevant and accurate measure of biological skin age, making it ideal for assessing the efficacy of cosmeceuticals, laser-based treatments, and cellular therapies targeting dermal rejuvenation; so, it is regarded as the benchmark for evaluating dermatological and regenerative therapies [6,26].

Pace-of-ageing clocks (e.g., DunedinPACE) enable monitoring of responsive treatment effects over short periods. DunedinPACE complements skin strategies by offering real-time insights into ageing velocity, especially in trials involving nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide NAD+ boosters or gene therapies; it also enables short-term tracking of intervention response [7]. Micro-ribonucleic acid (miRNA)-based Skin clocks show promise for non-invasive, patient-compliant diagnostics and testing, particularly in cosmetic dermatology [27]. Thus, emerging third generation clocks such as DunedinPACE and miRNA-based skin clocks offer novel value in the efficacy’s evaluation of skin rejuvenation strategies.

The last developed skin epigenetic clock by Rayan and collaborators represents a significant advancement by providing a tissue-specific biomarker that accurately reflects biological ageing and rejuvenation in human facial skin through DNA methylation profiling of epidermal and dermal fibroblasts. Its strength lies in sensitivity to reversible ageing changes following esthetic interventions, offering an objective measure for evaluating skin anti-ageing therapies. However, its reliance on invasive skin biopsies, limited commercial availability, and current validation primarily in lighter skin phototypes pose challenges for broader clinical application [26,28].

Mean Absolute Error (MAE) in skin epigenetic clocks quantifies the average difference between predicted skin biological age and the actual chronological age, serving as a key metric to evaluate the clock’s accuracy and reliability in measuring skin ageing. Among skin clocks and related ageing biomarkers, the Rayan Skin clock ranks highest with the lowest MAE (~3–4 years), outperforming earlier models like the Horvath Skin and Blood clock, thus reflecting its superior precision in assessing biological skin age. Within the MAE hierarchy, the Rayan clock is followed by the Horvath Skin and Blood clock (~5–7 years) and the blood-based clocks (like PhenoAge and GrimAge) which typically have higher MAEs when applied to skin (often >8 years) due to tissue specificity limitations. miRNA-based skin ageing clocks, still emerging, show moderate accuracy with MAEs around 8–10.9 years, but require further validation. This hierarchy highlights the importance of tissue-specific design for precise skin ageing measurement. Epigenetic biomarkers of (skin) ageing require further studies on inter-individual variability and also validation across diverse populations [26,28,34,35].

Besides epigenetic clock estimating cellular ageing by DNA methylation variations, non-epigenetic biomarkers, like telomeres’ length, senescence-associated proteins or inflammageing biomarkers, serve as mechanistic or histological adjuncts, not standalone age clocks, and they lack quantitative replication across patient cohorts, and the sensitivity and specificity needed for precision monitoring of clinical skin rejuvenation outcomes [8,9]. Among non-epigenetic senescent biomarkers might be considered: (a) p21, p53 (biomarkers of cell cycle arrest); (b) p16INK4A—its enhanced expression significantly correlates to chronological human epidermis ageing, older facial perception and to the age-changed elastin morphology in the dermal papilla (for instance, higher proportion of p16INK4A- positive melanocytes is associated with more facial wrinkles); (c) senescence-associated β-galactosidase (SAβGAL)—the mostly used histochemical biomarker in human dermal fibroblasts; (d) nuclear matrix protein lamin B1—a quantitative biomarker of skin senescence, decreasing with age; (e) acH4 (acetylated histone H4) and H4K20me1 (histone H4 monomethylated on lysine 20), which are altered histone biomarkers during skin senescence (correlated to delayed differentiation of keratinocytes and epidermal hyperplasia). Histones are DNA bound proteins with an essential role in chromatin organization, differentiation of epidermal stem cell niche into sebocytes and interfollicular epidermis, as well as in skin homeostasis [20,32,38,39]. In addition, the GlycanAge analysis measures changes in glycosylation patterns of immunoglobulins (IgG) which could trigger systemic chronic inflammageing and age-associated disorders [40,41].

Comparative insights on various epigenetic and non-epigenetic clocks/ biomarkers relevant to skin rejuvenation strategies’ evaluation are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Comparative insights on various epigenetic and non-epigenetic clocks/biomarkers relevant to skin rejuvenation strategies’ evaluation.

In conclusion, although photoageing remains a critical clinical concern with distinct histopathological markers which molecular clocks do not yet fully encompass, the integration of the biological age clocks, particularly epigenetic clocks, has revolutionized the evaluation of skin rejuvenation strategies, from topical interventions and energy-based devices to regenerative medicine and epigenetic drugs. A combined approach using validated epigenetic clocks with skin-specific calibration and complementary biomarkers offers the most powerful and practical framework for quantifying and validating the biological effects of anti-ageing interventions on the skin. These tools will be essential in personalizing dermatologic care, evaluating anti-ageing compounds, and guiding regenerative therapies in both clinical trials and esthetic medicine [26,28,34,35]. Precise biomarkers of ageing and rejuvenation for whole-body, at cellular and molecular levels, are prospecting the current advanced spatiotemporal multi-omics approaches, including transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics, gene signatures, and epigenomics, which can offer in-depth understanding of the complexities and relationships regarding molecular dynamics, cellular interactions and signalling pathways, inherent in ageing and regeneration, thus supporting new potential therapeutic innovations [20,30,43].

3. Senotherapeutics Targeting Senescent Skin Cells

3.1. Senolytics and Senomorphics—Mechanisms of Action

The senescent skin cells are characterized by: resistance to apoptosis; permanent loss of mitotic capacity; lower cell motility; over-activated focal adhesion kinases; activation of altered/inflammatory secretome (i.e., Senescence-Associated Secretory Phenotype, SASP); degradation of nuclear envelope lamina which anchors heterochromatin; remodelling of chromatin; reduced histone methylation (H3K9me3 and H3K27me3) with re-activation of silent DNA within highly condensed heterochromatin domains; the emergence of senescence-associated heterochromatin foci (SAHF); genomic instability and shortened telomeres; mitochondrial disturbances; morphological alterations. [10,14].

SASP might be triggered by multiple genome-related factors (DNA mutations, telomeres’ shortening, activated oncogenes, etc.) and consists of the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines (mainly interleukin IL-6 and IL-8), growth factors, proteases, bioactive lipids, metabolites, extracellular vesicles. All these secreted molecules will further promote chronic inflammation, degradation of ECM, avoidance of immune clearance of the senescent cells; moreover, it will enhance SASP secretion by an autocrine effect. The contribution of SASP to cellular senescence seems to be highly dependent on cell-type and stimuli [12,44]. Besides the altered secretome, skin cell senescence is also characterized by dysregulation of lipid metabolism with increased uptake and accumulation of lipids (presumably due to up-regulated p53 pathway and fatty acid synthase, which seems to be correlated to SASP), especially with increased levels of lysophosphatidylcholines and sphingolipids in human dermal fibroblasts [44,45]. In addition, in senescent cells there is an up-regulation of anti-apoptotic pathways, such as p53, Bcl-2 (B-cell lymphoma 2), the heat shock protein 90 HSP90, nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (inflammation pathway) (NF-kB), or nuclear transcription factor 2. For example, NF-κB is regarded as an essential transcription factor that controls the expression of multiple genes encoding SASP and pro-inflammatory cytokines and that is positively or negatively correlated with many other pathways involved in ageing, like mTOR, sirtuins, insulin/insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1), DNA damage response. Therefore, the genetic down-regulation of NF-κB or its pharmacological inhibition by senomorphics have diminished cell senescence in mouse models. For instance, the compound SR12343 is an NF-κB inhibitor that has reduced in vivo SASP factors in senescent fibroblast cells and has prolonged lifespan in both chronologically aged and photoaged mice [10,12,44].

3.2. Main Senotherapeutic Agents Preclinically and Clinically Tested

Senotherapeutics can be divided in two classes: senolytics which selectively eliminate senescent cells by re-activating their apoptotic pathways, and senomorphics which mitigate the SASP without killing senescent cells; the latter are regarded as safer and more effective than senolytics [12,44,46]. The differentiation between two classes seems difficult in vivo and dependent on cell type and agent’s concentration [44].

A comparative analysis regarding the main outcomes and limitations of the most important senomorphic and senolytic agents tested for skin rejuvenation is presented in Table 4. In mice transplanted with human aged skin xenograft and treated for 30 days with the oral senolytic cocktail composed of dasatinib (a tyrosine kinase inhibitor) and the flavonoid quercetin (D + Q), the following results were reported: a substantial decrease in SASP factors (IL-6, MMP-1, MMP-3) and an enhanced dermal collagen proportion, in the absence of noticeable inflammatory reaction or side effects [47]. Mohammad IS et al. has found that a single dose of D + Q was able to induce temporary chromatin changes in young vascular smooth muscle cells and durable anti-senescent effects in senescent cells, the single dose being more selective than triple dosing; however, the off-target effects, especially on healthy cells, are not addressed [48]. In a clinical trial, after 3 days of oral administration, the senolytic cocktail D + Q lowered the expression of some biological age biomarkers, such as p16 and p21 in epidermis, as well as p16, p21, SAβGAL and SASP factors in adipose tissues; these effects were maintained even 11 days post-therapy [12,49]. To date, clinical trials have not assessed D + Q effects on visible or structural skin parameters (e.g., elasticity, wrinkle count), the potential off-target effects (dasatinib may temporarily induce senescence-like features in healthy cells), long-term toxicity (dasatinib might cause pleural effusion, cytopenias and immunosuppression); in addition, current clinical studies have open-label designs, short intervention duration (most were over 3–7 days, with only one study lasting 6 months), and enrolled small cohorts (on average 20 participants) without placebo controls [47,50].

The senolytic agent ABT737 is a specific inhibitor of Bcl-2 anti-apoptotic pathway and was able to induce ~65% cell death and to reduce the expression levels of SAβGAL, p16, p21, besides to an increased epidermal concentrations of the pro-apoptotic protein cleaved caspase-3 in cultures of human and mouse senescent skin fibroblasts with DNA mutations. Moreover, its derivative ABT263 (navitoclax), applied topically to mice, reduced the senescence biomarker p16INK4A, enhanced collagen network and dermal thickness, while attenuating hyperpigmentation, by selective elimination of fibroblasts in a murine model of senile lentigo [51,52]. The flavonoid fisetin is another promising senolytic that reduced MMPs and transepidermal dehydration in a mouse model of skin photoageing [33,53,54].

Rapamycin (sirolimus), an immunosuppressive drug, acts also as senomorphic by inhibition of mTOR and NF-κB, suppressing SASP factors. In topical administration, rapamycin reduced wrinkles, decreased the p16INK4A biomarker of skin cells’ senescence to subjects over 40 years old with photoageing and loss of dermal volume [55,56,57]. As senomorphics, metformin, apigenin and kaempferol significantly decrease SASP in senescent fibroblasts [58,59]. The first-choice biguanide in type 2 diabetes, metformin suppresses SASP expression and SAβGAL activity in different senescent cell types, including human diploid fibroblasts. Furthermore, metformin modulates many of the interconnected pathways of biological ageing by: activation of AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) and sirtuin SIRT1; down-regulation of insulin/IGF-1 and mTOR; stimulation of DNA repair mechanisms and mitochondrial functions; reduction in oxidative damage, genome instability and telomeres’ shortening; stimulation of macroautophagy and proteostasis; reduction in epigenetic histone alterations. Metformin expands the lifespan in mouse models and has entered in TAME (Targeting Ageing by Metformin) clinical trial [33,60,61]. Some statins (atorvastatin, pravastatin, pitavastatin) inhibit oxidative stress-induced endothelial senescence and up-regulate endothelial nitric oxide synthase and SIRT1; simvastatin acts as senomorphic by decreasing SASP expression in senescent human fibroblasts [11,22,52]. Inhibitors of p38MAPK pathways such as UR13756 and BIRB796 have been very efficient in blocking the SASP, since p38MAPK is activated by various senescent-inducing factors and is also greatly involved in promoting cellular senescence [19,33].

The senotherapeutic peptide OS-01 (also known as Pep 14), the active ingredient in OneSkin’s topical products which have been patented since April 2025, acts both by preventing cells from entering into the senescent state and as senolytic against the existent senescent cells, in a similar way as topical rapamycin [62,63]. In randomized clinical trials (RCT), OS-01 has thickened the skin barrier, enhanced skin radiance and texture, and has also diminished the wrinkles’ depth. Moreover, in the OS-01-topically treated female volunteers group, there were recorded a significant decrease in the blood concentrations of the pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-8, as well as a reduced progression rate in biological age (measured by GlycanAge analysis) [64]. Clinical trials for the pipeline senotherapeutic peptide OS-01 have also underscore the skin’s essential role within both the systemic ageing network and the chronic inflammatory disorders, thus emphasizing the importance of integrating the skin-focused antiageing strategies within other pro-longevity ones [64,65].

BPTES, bis-2-(5-phenylacetamido-1,3,4-thiadiazol-2-yl)ethyl sulphide, is a selective inhibitor of glutaminase-1 (GLS1), enzyme that plays a critical role in survival of human senescent cells; inhibition of GLS1 could remove senescent cells and stimulate skin repair mechanisms [66]. In an interesting mouse/human chimeric model (skin grafts of senescence-induced human dermal fibroblasts collected from male volunteers which were subcutaneously transplanted to nude mice), BPTES, given as intraperitoneal (i.p.) injections, has demonstrated a significant and selective senolytic activity against aged human dermal fibroblasts, which was maintained up to 30 days post-therapy. BPTES has increased collagen’s density in the dermis, while it has reduced SASP biomarkers (SAβGal, p16, p21, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, MMP-1, MMP-3, MMP-9). Since glutaminase-1 and glutaminolytic pathways are also shared by the activation of immune T cells in response to cancer cells proliferation, their inhibition by BPTES might be associated with the risk of long-term carcinogenesis. Other limitations of this study are also presented in Table 4 [67,68].

FOXO4-DRI peptide (FOXO4-D-retro-inverso-isoform peptide) has selectively down-regulated p53-serine15 phosphorylation (p53-pS15) responsible for apoptosis resistance in keloid fibroblasts and has also promoted p53-pS15 translocation from the nucleus to the cytoplasm. Its promising anti-ageing effects and limitations into clinical translation are also depicted in Table 4 [69,70]. Other clinical trials are investigating the anti-senescence activity of procyanidin C1 (PCC1) and its senolytic complex PCC1 + Cellumiva™ (procyanidin C1 + pterostilbene + spermidine), as well as of cycloastragenol (CAG), 25-hydroxycholesterol, nordihydroguaiaretic acid (NDGA), rutin, Silybum marianum extract, urolithin A and ergothioneine, which are summarized also in Table 4 [60,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81].

Table 4.

Comparative analysis of the main senomorphic and senolytic agents preclinically and clinically tested for skin rejuvenation. (the arrow ↓ means decrease; the arrow ↑ means increase).

Table 4.

Comparative analysis of the main senomorphic and senolytic agents preclinically and clinically tested for skin rejuvenation. (the arrow ↓ means decrease; the arrow ↑ means increase).

| Substance | Model and Dose Regimen | Mechanism/ Modified Biomarkers | Main Results and Limitations | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SENOLYTICS | ||||

| Dasatinib + Quercetin (D + Q) | Mice model; oral 5 mg/kg D + 50 mg/kg Q, intermittent dosing; | ↓ p16, p21 ↓ SAβGAL ↓ SASP Bcl-2 inhibition | Attenuated fibrosis, cognitive decline, osteoarthritis, diabetic complications; Limited administration period, small size cohorts; no data on visible or structural skin parameters; no long-term safety data (especially on healthy cells); | [12,47,49] |

| Navitoclax (ABT263) | Preclinical/animal studies; early-stage topical formulation development: topical application of ABT-263 (Navitoclax) in aged mice; 5 day treatment; Murine models of lung fibrosis, osteoarthritis; 50 mg/kg/day for 2 weeks; | Bcl-xL/Bcl-2 inhibitor; ↓ senescent cell viability; ↓ p16INK4A | Improved dermal thickness and collagen organization; reduction in skin senescence markers; improved wound healing in aged mice; improved tissue function; Toxicity concerns; human topical safety/efficacy not established; thrombocytopenia as adverse effect in systemic administration; | [51,52,72] |

| BPTES | Mouse/human chimeric model (skin grafts of senescent human dermal fibroblasts were subcutaneously transplanted to nude mice); mice treated with BPTES or vehicle, intraperitoneal, for 30 days | ↓ SAβGal; ↓ p16, p21; ↓ IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8; ↓ MMP-1, MMP-3 and MMP-9 | Selective senolytic effects on aged dermal fibroblasts, sustained 1 month post-therapy; increased collagen density; increased cell proliferation in the dermis; decreased SASP. Limitations: small sample size; only male human skin grafts collected; unknown effects on the surface properties of human skin; risk of suppression of the skin T lymphocytes’ proliferation and risk of carcinogenesis | [66,67,68] |

| FOXO4-DRI peptide (FOXO4-D-retro- inverso-isoform peptide) | Preclinical animal studies; Clinical trial: 10 keloid skin samples (females); 7 normal skin samples (female participants) | Peptide-induced senescent cell apoptosis: disruption of FOXO4–p53 interaction | Mechanistic insights into FOXO4-DRI: down-regulation of p53-serine15 phosphorylation (p53-pS15); p53-pS15 translocation into cytoplasm; selective agents to induce apoptosis of senescent fibroblasts in both keloid fibroblast and organ culture senescent models. Improved skin regeneration and reduced ageing biomarkers; rejuvenate epidermal stem cell function, leading to improved skin barrier integrity and repair capacity; Delivery challenges; small cohorts | [69,70] |

| Fisetin | C57BL/6 mice; 100 mg/kg/day, 1 week on/1 week off | ↓ p16INK4A; Bcl-2 family inhibition | Improved vascular endothelial function and arterial stiffness | [54] |

| Cycloastragenol (CAG) | Aged mice; oral, 50 mg/kg/day for 2 weeks | ↓ Bcl-2, PI3K/AKT/mTOR axis inhibition | Selective senescent cell clearance; improved cardiac and muscle function | [75] |

| 25-Hydroxycholesterol | Aged mice; i.p., 50 mg/kg/day 5 consecutive days | ↓ p16INK4A, ↓ IL-6, ↓ TNF-α | Reduced arterial stiffness and improved vascular reactivity | [76] |

| SENOMORPHICS | ||||

| Rapamycin/ sirolimus | Skin explants and 3D models; Human subjects, photoaged skin: topical; Mice model: intermittent or lifelong oral dosing (e.g., rapamycin 14 ppm in diet); | Inhibition of mTOR, NF-κB and SASP; ↓ p16INK4A ↓ IL-6, IL-8 in plasma; ↓ MMP-1 | Reduced wrinkles; improved ECM remodelling; extended lifespan, improved cardiac and cognitive function (mice model); Small cohort; reduced administration period | [55,56,57,62,63] |

| Metformin | HUVEC cells in vitro (0.5–2 mM); aged mice 50 mg/kg daily | ↑ AMPK, ↓ NF-κB, ↓ ROS | Reduced SASP, improved endothelial function | [60,61] |

| Nordihydroguaiaretic acid (NDGA) | C57BL/6 male mice: 15 mg/kg/day oral | LOX inhibition, ↑ PPARα, ↑ AMPK | ~8–10% lifespan extension, improved metabolic parameters | [81] |

| Rutin | Aged mice; 50 mg/kg/day oral | Inhibits ATM–HIF1α–TRAF6 axis; ↓ IL-6 | Reduced vascular inflammation, enhanced chemotherapy efficacy | [77] |

| SENOMORPHIC AND SENOLYTIC (DUAL ACTION) | ||||

| OS-01 (Pep 14) | RCT | ↓ SASP ↓ IL-8 ↓ glycated IgG | Thickened the skin barrier, enhanced skin radiance/texture, diminished the wrinkles’ depth. Limited cohorts | [64,65] |

| Procyanidin C1 (PCC1) | ageing-related skin-fibrosis, murine models | inhibition of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) phosphorylation and suppression of multiple downstream signalling cascades (ERK/MAPK, AKT/mTOR and TGFβ/SMAD pathways) | Significant anti-fibrotic skin effects: reduced epidermal hyperplasia and thickness; reduced abnormal collagen deposition; restored the collagen I/III ratio human translation needs validation | [71,72,73] |

| PCC1 + Cellumiva™ (senolytic complex = procyanidin C1 + pterostilbene + spermidine) | Open-label RCT on 75 female healthy volunteers, aged 45–65; oral dietary supplement; once daily; 12 weeks | imaging technologies; feedback questionnaires | Good effects on skin barrier function and texture/radiance, while diminishing wrinkles; Limited safety data | [73,80] |

3.3. Critical Insights on Senotherapeutics as Skin Rejuvenating Strategy

Senolytics and senomorphics can mitigate chronic senescence in aged skin by removal or modulation of senescent cells via targeting senescence pathways and can also rejuvenate tissue microenvironment, but they can be associated with the risk of excessive, unintended normal tissue clearance or inflammation [44,50,51,59]. Although more than 20 senotherapeutics are now in clinical trials, it remains to further investigate their efficacy’s dependency on the cellular type, concentration and stress factors (like for aspirin’s effects on senescence), thus guiding the choice of these agents in specific age-related skin diseases [10,19,82]. Moreover, it remains to elucidate: (a) the adverse effects of senotherapeutics on various proliferating or quiescent cell-types which share critical pathways with those in targeted senescent cells; (b) their dysregulatory potential of other critical cellular processes, as well as (c) their effects on many ageing biomarkers, in order to more precisely elucidate their mechanisms of action and to establish the best choice between senolytics and senomorphics (given the role of senescent cells in wound healing, tissue regeneration, cancer prevention) [12]. Synergistic effects of senotherapeutics with existing treatments (such as retinoids or antioxidants) might enhance the efficacy on skin rejuvenation but require future evidence-proof human trials [83]. Current limitations and future research directions on senotherapeutics as skin rejuvenators are depicted in Table 5.

Table 5.

Knowledge gaps and future research directions in senotherapeutics as skin rejuvenating strategy.

4. Skin Anti-Ageing Strategies Targeting Genomic Instability and Telomere Attrition

Nuclear genome instability is mainly caused by the accumulation of DNA mutations and by the decline in the efficiency of the DNA damage repair (DDR) mechanisms. Nuclear genome instability is significanty correlated to an accelerated progression of age-related changes, as noticed also in progeroid Werner and Cockayne syndromes [84,85]. Telomeres are repetitive DNA sequences acting as protective caps at the extremities of linear eukaryotic chromosomes with a crucial role in genomic stability. During ageing and consecutive of multiple cell divisions, telomeres become progressively shorter; beyond a critical length of the telomeres, the cell cycle will be irreversibly stopped, thus triggering cell apoptosis. The parallel processes of telomeres’ shortening and of cell senescence, respectively, represent an essential hallmark of ageing called “life clock” [34,86]. Besides genomic instability, telomere attrition is viewed as a main contributor to fibroblast senescence in aged skin and disease-related ageing skin. Excessive telomere attrition in the progenitor cells of the highly proliferative tissues (haematopoietic system, gastrointestinal tract, skin) ultimately triggers DDR such as cell cycle arrest, apoptosis, differentiation disorders and senescence, while in hypoproliferative tissues (heart, brain and liver) oxidative stress might further increase telomere sequence damage and attrition [87]. DDR signalling pathways are activated in response to few critically short telomeres and comprise the following steps: the overexpression of p53 and p21 (cell cycle inhibitory biomarkers); the altered secretome SASP, which modify the ECM composition and propagates the senescent phenotype to surrounding cells; finally, systemic chronic inflammation [88,89].

The protective approaches to overcome telomere attrition tested so far could be illustrated by:

- stimulation of reverse transcriptase telomerase, an enzyme responsible for biosynthesis of new telomeric DNA based on RNA template in highly proliferative skin cells like stem cells, using for instance as telomerase activator the compound TA-65 [8,42]. Moreover, liposomes with xenogenic DNA repair enzymes like photolyase isolated from microalgae Anacystis nidulans and T4 endonuclease from Micrococcus luteus have proven efficient due to a significant decrease in telomere shortening rates [11,33]; as well as liposomes with 8-oxoguanine glycosylase photolyase (OGG1) which have demonstrated an essential role in reducing the biomarker 8-oxo-7,8-dihydro-2′-deoxyguanosine of oxidative DNA damage and mitochondrial dysfunctions [58,84];

- recovering of the multi-protein shelterin complex that is essential for stabilization of chromosomes and for their protection against being detected as double-stranded breaks. The TRF2 protein of shelterin complex is involved in telomere capping and DDR inhibition; TRF2 deficiency triggers the activation of p53 signalling pathway and cellular apoptosis. In this regard, topical application of TRF2 might have a protective role in telomeric DNA [58,85,87];

- nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide NAD+ boosters (such as NAD+ precursors: nicotinamide riboside and nicotinamide mononucleotide), which, like telomerase activators (e.g., compound TA-65), support DNA integrity and cellular longevity, help slow DNA damage accumulation; however, direct evidence in human skin is limited and their effects may be systemic [59].

5. Regenerative Medicine Targeting Skin Stem Cell Exhaustion: Fundamentals and Clinical Progress

Mesenchimal stem cells (MSCs) have an essential role in tissue repair and homeostasis, due to their multipotency and self-renewal ability. Aged skin is marked by stem cells’ pool declining, correlated with skin atrophy, fragility and hyperpigmentation [86,90]. Regenerative therapeutic approaches in skin rejuvenation are designed upon the current understanding of the main mechanisms and molecules involved in the physiological regeneration of skin. Using either endogenous stem cells, such as adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells (AD-MSCs), amniotic membrane stem cells (AMSCs), human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells (hUC-MSCs), tissue-induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), or extracellular vesicles/exosomes derived from endogenous MSCs, the following beneficial anti-ageing effects were reported: stimulation of mitosis, proliferation and differentiation, especially of human dermal fibroblasts; up-regulation of local immunological defence mechanisms; release of the angiogenesis-modulatory cytokines, antibacterial peptides and anti-inflammatory molecules; release of the growth factors and cytokines essential for skin trophicity, tissue re-epithelization, wound healing, biosynthesis of elastin and collagen fibres in the ECM; inhibition of proteins’ glycation; inhibition of oxidative stress [38,45,84,91]. The stem cells have the advantage of being easily obtained and abundant. Other advantages, especially of AMSCs, rely on: multipotency, low immunogenicity, facil isolation from the placenta, unapplicable ethical issues like those imposed to embryonic stem cells [18,92].

Regenerative medicine-based skin therapies used alone or in combination to conventional treatments might offer more promising, efficient and safe solutions in facial rejuvenation, in comparison to conventional approaches (such as cosmeceuticals, microneedle, dermal fillers, injectables, fractional laser) [12,92,93]. For instance, topical application of AMSC with vitamin E to photoaged human subjects have significantly decreased wrinkles, ultraviolet spots and pores. Injected into the dermis, ADSCs have improved skin vascularization, hydration and density. In topical use, hUC-MSCs-conditioned media associated with microneedling significantly improved skin brightness and texture in comparison to microneedling alone [18,93].

On the other hand, as an alternative to stem cell-based skin rejuvenation, regenerative cell-free approaches might use: (1) topical platelet concentrates, such as: platelet-rich plasma (PRP), platelet-rich fibrin (PRF), and injectable platelet-rich fibrin (i-PRF); and (2) blood cell secretome (BCS). PRP, an autologous and highly concentrated preparation of platelets, is extensively applied in skin anti-ageing because it has shown to boost: (a) skin rejuvenation through the great proportion of growth factors (i.e., platelet-derived growth factor PDGF, transforming growth factor TGF, vascular endothelial growth factor VEGF, and IGF-1), which are essential for fibroblasts’ proliferation and for biosynthesis of the dermal collagen and elastine fibres; (b) thickening of epidermal layers and of dermal–epidermal junction; (c) wound healing; (d) recovery of oxidative homeostasis [22,38,53]. Regarded as second- and third-generation platelet concentrates, PRF and i-PRF have been so far applied in limited clinical trials to establish their effectiveness in skin rejuvenation [85]. BCS, also called autologous conditioned serum (ACS), is obtained by the enrichment of blood serum with anti-inflammatory cytokines, growth factors, lipid mediators, and exosomes. In a clinical study, topical application during 12–24 weeks of BCS significantly enhanced skin hydration and firmness [31,91].

In preclinical and clinical studies, stem-cells-derived exosomes (extracellular vesicles, EVs) as rejuvenation therapies have demonstrated the ability to modulate the expression of some longevity-associated genes (i.e., Klotho, FOXO3, FGF23) or collagen-related genes (COL1A1); to stimulate ECM remodelling, to increase collagen synthesis and elastin fibre density, thus enhancing dermal thickness; to modulate inflammation and to promote angiogenesis via PI3K/AKT, Notch pathways; to improve skin hydration, elasticity, tone and pigmentation (usually within 6–12 weeks) and to reduce wrinkles. Adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cell (AD-MSC) secretome or other stem-cells-derived exosomes investigated for facial skin rejuvenation have gained more effective transdermal delivery when coupled to microneedling, intradermal injections or fractional laser; moreover, these adjunctive methods have enabled an increased collagen production, ECM remodelling and more profound biological impact than topical-only applications. The choice among these delivery methods is dependent on the side effects’ risks, patient preferences and costs. Stem-cells-derived exosomes are well-tolerated, with minimal erythema or petechiae from microneedling or laser. For instance, microneedling is associated with fewer reported adverse reactions (transient erythema, edema, pain and discomfort for several hours post-treatment), is cheaper and more accessible than fractional laser [94,95,96]. All these above-mentioned efficacy and tolerability data are confirmed and validated mainly from a cosmetic-dermatologic perspective. In addition, most clinical trials enrolled small cohorts (n < 60 participants), with short-term follow-up (≤12 weeks) and lacked robust controls (e.g., placebo, double-blind, randomized large size arms), therefore restricting their generalizability and statistical power of results [94,95,97]. Moreover, few clinical trials directly assess biomarkers specific for epigenetic age (e.g., DNA methylation), therefore the epigenetic profiling still remains an unmet opportunity in human skin rejuvenation trials [95,97].

The main aspects of the clinical trials on stem-cells derived exosomes (EV) as skin anti-ageing strategy are described in Table 6, comprising study design, the principal results and limitations. analyzing the preliminary results of the clinical interventions for stem-cell-based exosomes used alone or in combination with traditional methods, we can conclude that stem cell-derived EVs are the most clinically advanced biologic interventions in skin anti-ageing and rejuvenation, demonstrating improvements in skin texture, pigmentation and acne-scars’ healing. Their regenerative and therapeutic potential in skin anti-ageing or skin repair is worthing further investigations in larger-scale RCTs, with better standardization of the study’s design and optimized formulations. Current obstacles in regenerative therapies translation into clinic are related to tissue sources, isolation technology, production control over batches, limited large clinical trials for efficacy and potential adverse reactions, lack of standardized protocols, as well as ethical legislation [92,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108].

Table 6.

Clinical trials on stem-cells derived exosomes (EV) as skin anti-ageing strategy (the arrow ↓ means decrease; the arrow ↑ means increase).

6. Regenerative Medicine Focused on Epigenetic Reprogramming and Epigenetic Drugs

6.1. Fundamentals of Epigenetic Reprogramming as (Skin) Rejuvenation Strategy

Progressive and persistent epigenetic alterations are regarded as primary drivers of the accelerated skin ageing process and somatic cells heterogeneity. Deciphering the dynamics and molecular mechanisms of epigenetic modifications during ageing is essential for therapeutic interventions’ design in skin rejuvenation and age-related diseases treatment, such as transient in vivo reprogramming [91,109]. Research on various models and species of ageing-related phenotypes and age-related diseases from yeast to human cells have identified the main age-related epigenetic alterations:

- ✓

- changes in DNA methylation pattern at cytosine residues, which are highly tissue-and age-specific;

- ✓

- post-translational covalent alterations of histones (i.e., methylation, acetylation, phosphorylation), decreased proportion of core histones and the incorporation of non-canonical histones;

- ✓

- reduced global heterochromatin and heterochromatin structural modifications with accumulation of senescence-associated heterochromatin foci (SAHF);

- ✓

- dysregulation of non-coding RNA’s expression pattern (ncRNA, i.e., microRNAs miRNAs, long non-coding RNAs lncRNA, and circular RNAs circRNA), which is correlated to alterations of the expression of genes involved in inflammation and oxidative stress-mediated cellular senescence [85,89,109].

Epigenetic reprogramming is one of the most promising emerging in vivo and in vitro skin-rejuvenation strategies able to reverse the transcriptome of the senescent cells in aged skin, by concomitantly ameliorating multiple skin-ageing hallmarks: telomere size, gene expression profiles, oxidative stress levels, mitochondrial morphology and metabolism, and nuclear envelope integrity. Epigenetic reprogramming-induced rejuvenation can be mediated either by transcription factors (genetically induced reprogramming) or by small molecules (chemically induced reprogramming, for instance by DNA methyltransferase inhibitors and histone deacetylase inhibitors) [84,86,87].

Having a huge potential in regenerative medicine, epigenetic reprogramming-induced rejuvenation might be complete or partial, although for anti-ageing strategies the partial reprogramming is much more adequate. Complete reprogramming converts any type of somatic cells into iPSCs, which have self-renewal ability and the potential to redifferentiate into fully rejuvenated various cell types. These features are mediated by complex and interconnected networks of transcription factors, signalling molecules and genes expression profiles, which make the process of ageing strongly linked to cellular differentiation [88,89]. Since complete dedifferentiation is also a common oncogenetic process, partial epigenetic rejuvenation aims to avoid the risk of tumorigenesis and to separate the rejuvenative properties and the safe age-reverse of reprogramming from full dedifferentiation, thus preserving the original cell phenotype, instead of regaining pluripotency [51,93,110,111].

6.2. Genetically Reprogramming-Induced (Skin) Rejuvenation Strategies

Genetically reprogramming-induced rejuvenation strategies currently involve the transient overexpression of four transcription factors called Yamanaka factors or OSKM factors (4F: OCT4, SOX2, KLF4 and c-Myc) able to trigger dedifferentiation in any type of somatic cell and reverse their ageing clocks, while preserving the cellular identity. In order to avoid the tissue-specific dysplasias reported for continuous expression of the OSKM/4F during 4–7 days, as well as the high risk of tumorigenesis (teratomas in mammalians) reported for in vivo 4F expression longer than 8 days, the epigenetic rejuvenation is applied as transient and shorter 4F induction cycles [45,88]. In addition to multiple short cycles of OSKM expression, there is a safe timeframe of reprogramming-induced rejuvenation and also a critical recovery period after treatment (since many biomarkers of transcriptome reversal occurred weeks later), not to mention that reprogrammed cells secrete soluble factors able to rejuvenate non-reprogrammed cells [38,84,85].

In the physiologically ageing mice, a single period or short cycles of OSKM expression have induced, in various tissues (including skin) and at body level, reversal of epigenetic clock, transcriptomic and metabolic effects, such as: DNA methylation changes, as well as lower expression of genes mediating inflammation, senescence and stress response pathways [38,112]. For instance, ubiquitous multiple transient cycles of 4F expression (2 days of expression followed by 5 days of rest) have reversed epigenetic clock, reseted telomeres’ length over critical threshold and have also extended the life expectancy in a mouse model of accelerated ageing (Hutchinson Gilford Progeria Syndrome); these effects might also be applicable to supercentenarians [53,84].

Other proven effects of Yamanaka 4F overexpression in aged mice were: remarkable reduction in p53 binding protein 1 (53BP1) involved in the DNA damage; downregulation of the expression of p53-mediated age-related stress response genes and senescence-associated metalloproteases (MMP13), interleukins IL-6 and IL-8; restored level of methylated histones H3K9me3 and H4K20me3; restored skin histologic appearance and thickening; significant life-span increase. It has been hypothesized that Yamanaka 4F also reset the epigenetic clock of the stem cells, thus diminishing the stem cell pool exhaustion during ageing [45,91].

Moreover, transient overexpression for 4 days of combined transcription factors OSKMLN (OSKM+ LIN28+ NANOG) in adult human dermal fibroblasts and endothelial cells, as well as in progeroid mouse fibroblasts, has revealed significant rejuvenating effects and diminished cells age, due to the reduction of senescence biomarkers of DNA and nuclear envelope damage, dysregulation of histones, mitochondrial ROS production, SAβGAL and SASP. Moreover, OSKMLN has restored telomeres’ length, mitochondrial membrane potential, and increased sirtuin SIRT1 protein levels, extended mice lifespan, in the absence of teratomas formation [89,113].

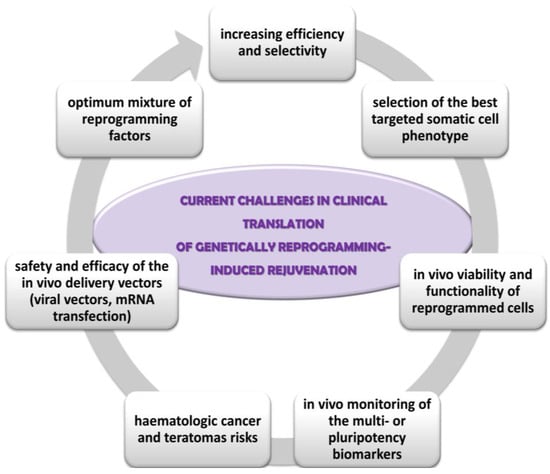

However, since the great majority of successful rejuvenation studies have been performed on animal tissues without taking into account species-specific differences, there are some challenges for clinical translations of genetically reprogramming-induced rejuvenation, such as (Figure 1):

Figure 1.

Current challenges in clinical translation of genetically reprogramming-induced rejuvenation.

- ✓

- the optimum mixture of reprogramming factors for each cell phenotype; low efficiency (about 25% of cells in culture being partially reprogrammed); lack of selective rejuvenation by reprogramming expression of genes which are not essential to ageing; lack of influence on some ageing hallmarks, such as mitochondrial DNA mutations, intracellular and extracellular metabolic aggregates [85,93];

- ✓

- the selection of the somatic cell type targeted for reprogramming; fibroblasts are best candidates due to their proportion in the skin, supportive role, proliferative capacity, the implication of their contractile form (myofibroblasts) in the non-functional persistent scars [51];

- ✓

- integration of the reprogrammed cells into the tissue physiology, especially in age diseases context; the persistence and the degree of the functionality of reprogrammed cells within the in vivo tissue microenvironment [87];

- ✓

- insufficient optimization and monitoring of the reprogramming techniques; for instance, in vivo monitoring of the multi- or pluripotency biomarkers in order to minimize long-term tumorigenesis risk, the stability and viability of the rejuvenated cells in culture and in vivo, the rate of ageing of the younger phenotype cells in comparison with the normal, un-reprogrammed skin cells [91];

- ✓

- carcinogenic risks: activation of oncogenes, point mutations in coding DNA associated with genomic instability and teratomas’ development; phenotypic mosaicism of partially reprogrammed stem cells can cause lineage bias, dysfunctional stem cell and higher haematologic cancer and teratomas risks [86,112];

- ✓

- the safety and efficacy of the in vivo delivery vectors of the reprogramming transcriptional factors. For instance, viral vectors are associated with increased cancer risk because they can cause insertional mutagenesis, residual expression or re-activation of reprogramming factors, or might have broad organ-tropism [84,109,114]. Other safer delivery methods already tested are transient transfection with non-integrating viral vectors, mRNA transfection, or chemically induced reprogramming by small molecules and growth factors.

6.3. Chemically Reprogramming-Induced Skin Rejuvenation Strategies

Since multiple epigenetically regulated pathways have been involved in skin ageing, epigenetic skincare has become an emerging field in the design of small molecule active ingredients. Chemical-based epigenetic reprogramming comprises: inhibitors of DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs); inhibitors of the histone deacetylases (HDACs) or of the histone methylases; activators of sirtuin SIRT6; microRNAs (miRNAs) and miRNA’s inhibitors, as well as modulators of the long non-coding RNA (lncRNA) HOTAIR (HOX Transcript Antisense RNA), assisted or not by CRISPR-gene editing technology [57,89,115,116,117,118]. Currently, epigenetic drugs applied by chemical-based reprogramming approach avoid the use of oncogene c-Myc (one of the Yamanaka factors 4F) and have been validated in mice experiments and more than 20 have entered clinical trials [114].

6.3.1. Small-Molecule Epigenetic Drugs: Main Inhibitors of HDAC and DNMT, and Activators of Sirtuin SIRT6

DNMT inhibitors, like 5-azacytidine, facilitate the reprogramming of human fibroblast into iPSCs, up-regulate their pluripotency gene expression and differentiation capacity towards other germ layers, confer human dermal fibroblasts a relaxed chromatin structure and short plasticity [89,93]. Histone methylation inhibitors also stimulate pluripotency-related gene expression. For instance, 3-deazaneplanocin A, an H3K27me3 and H4K20me3 inhibitor, activates OCT4 during iPSC reprogramming [114]. HDAC inhibitors reverse the deacetylation of histone tails and trigger the specific gene expression related to epigenetic clock. They could be illustrated by the following examples. Rapamycin, that is also a senomorphic, might stimulate epigenetic reprogramming since it maintains the level of some histone biomarkers which are decreasing with age (i.e., H3R2me2, H3K27me3, H3K79me3, H4K20me2) [55,57]. Moreover, in a clinical trial, topically applied rapamycin has reduced p16INK4A biomarker levels in ageing skin and DNAm age, after 6 months of therapy [57,62]. The isoflavone equol (formed by gut bacteria from soy isoflavone daidzein), topically applied for 8 weeks, decreases biomarkers of global DNA methylation and of telomere attrition, with visible improvements in skin roughness, texture, hydration and smoothness [88,112,117]. Sulforaphane from cauliflower, anacardic acid from Anacardium occidentale (cashew) nutshells, epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG) from green tea, and palmitoyl-KVK-L-ascorbic acid conjugate, function as inhibitors of the DNA methyltransferase 1 (DNMT1, the most abundant enzyme responsible for DNA methylation) or of the enzyme HDAC, and they have stimulated the synthesis of procollagen, that is greatly involved in matrix repair, skin elasticity and strength [34,115].

Topical epigenetic skincare agents (e.g., equol, sulforaphane, retinoids, oligopeptides, etc.) are increasingly favoured for their safe, non-invasive and epigenome-targeted effects, although their clinical efficacy remains slow and moderate [117,118,119]. The main knowledge gaps in topical epigenetic modulators which must be further elucidated and validated are related to: (a) long-term safety; (b) optimal delivery systems; (c) bioavailability and penetration into deep dermal layers; (d) off-target epigenomic effects; (e) large randomized human trials [57,105,117,119,120].

Sirtuins are intensively investigated as HDAC modulators in epigenetic skin rejuvenating attempts [87]. Sirtuins are encoded by Sir-2 gene, considered one of the longevity gene besides p66shc, ink4a, FOXO and daf-2 genes, and have double catabolic activity both in deacetylation and ADP-ribosylation coupled to NAD+ hydrolysis. Among SIRT1-7 protein family, nuclear sirtuin SIRT6 is mostly studied for the prevention of immune skin dendritic cells’ (Langerhans cells) senescence [22]. Nuclear SIRT6 is classified as histone deacetylase whose activity significantly improves upon binding of fatty acids and whose major histone substrates comprise H3K9, H3K56 and H3K18; SIRT6 has also non-histone targets, such as: tumour protein p53, histone acetyltransferase GCN5, and tumour necrosis factor TNF-α. SIRT6 increases nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD) levels by its ADP-ribosyltransferase activity for mono-ADP-ribosylate nuclear proteins [51,89,114,121].

SIRT6 directly or indirectly control the promoters of the genes for main transcription factors and thus mediate crucial pathways for DNA repair, heterochromatin relaxation and compaction, antioxidant defence, epigenome maintenance, transcriptional regulation of metabolic processes, endothelial cell function and cellular ageing. Furthermore, SIRT6 overexpression efficiently activates and restores DNA repair of single-strand breaks and double-strand breaks, especially under oxidative stress conditions, thus contributing to longevity. In photoageing induced either by UV irradiation or genotoxic chemicals, SIRT6 facilitates the excision of bulky DNA adducts by nucleotide excision repair pathway [22,34,113,121]. SIRT6 is also significantly inversely correlated to human primary skin fibroblasts ageing; furthermore, SIRT6 overexpression expands by 27% the median lifespan in male mice and by 15% in female mice compared to wild type mice [22,113]. In addition, SIRT6 enhances: the integrity of telomeric chromatin and TRF2; epigenetic reprogramming efficiency in human dermal fibroblasts; preservation of repetitive sequences of heterochromatin organization; as well as maintenance of youthful epigenetic clock in correlation to lamin A/C (i.e., a nuclear scaffold protein involved in chromatin packaging and whose mutations were identified in Hutchison-Gilford progeria) [90,105,109,112,119].

Activators of SIRT6 as potential epigenetic skincare tested so far might be illustrated by: resveratrol and trans-polydatin (a more active glycosidic derivative of resveratrol isolated from Polygonum cuspidatum); MDL-800, an allosteric SIRT6 modulator promoting DNA repair and genomic stability [45,114]; cyanidin, a quercetin derivative that activates the in vitro SIRT6 deacetylase activity (by 55-fold increase); the alkaloid licorine (stimulates SIRT-mediated DNA repair in human fibroblasts); brown algae-isolated polysaccharide fucoidan (a strong in vitro activator of SIRT6) [22,45,53,121]; ergothioneine, that stimulates SIRT1 and SIRT6 expression, reduces mitochondrial oxidative stress and hyperglycemia; “SIRTfood”/sirtuin diet (food rich in sirtuins’ activators such as resveratrol) [113,121,122]. However, sirtuins’ uncontrolled overexpression can promote epithelial–mesenchymal dysplasia and therapeutic resistance, therefore further research on many experimental models, in a hormesis approach, is still needed [105,112,113,119].

Comparative insights into the most relevant emerging studies on small molecule epigenetic drugs as skin rejuvenation strategy, their principal outcomes in restoring epigenetic balance and their challenges towards clinical translation are summarized in Table 7. Small-molecule epigenetic drugs, such as inhibitors of HDAC and DNMT, or activators of sirtuin SIRT6, have proven to be a promising route to shift gene expression toward a youth-like state, in both systemic and topical application, thus enabling biological rejuvenating effects by reversing epigenetic clocks. However, they are currently limited by non-specific targeting, possible risk of epigenomic instability, systemic toxicity and dose sensitivity; they also lack robust clinical anti-ageing trials in human skin ageing, since most findings derive from animal models (e.g., remetinostat), cosmetic contexts or from skin cancer clinical interventions [84,105,119,120,123,124,125,126,127,128,129].

Table 7.

Comparative insights into the main emerging clinical and preclinical studies on small molecule epigenetic agents as skin strategies.

6.3.2. MicroRNAs (miRNAs)-Based Modulators in Skin Rejuvenation

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are gaining increasing interest as skin rejuvenating alternatives due to their potential of regulating the expression of some essential genes involved in ageing. MicroRNAs are small (~22 nucleotides) non-coding RNA molecules able to bind to messenger RNAs (mRNAs), either degrading them or inhibiting the translational process [116]. miRNA-based interventions, delivered via exosomes, nanoparticles or topical formulations, have high tissue specificity enabling skin-selective regulation of key ageing biomarkers of inflammation and senescence and also of collagen production; but they encounter great limitations and challenges related to the efficiency of transdermal delivery, stability, durability of effects, and off-target undesired regulatory reactions [118,130].

The great majority of miRNA-based therapeutics as skin rejuvenators is still in early preclinical studies as topical formulations with the potential to post-transcriptionally regulate the expression of genes associated with senescence. In early-stage clinical trials for skin rejuvenation there are tested some topical formulations and miRNA delivery systems, such as miR-21- and miR-146a-loaded nanoparticles [118,131]. The miRNAs and miRNA’s inhibitors which are mostly advanced in preclinical and clinical tests for skin anti-ageing purposes are summarized in Table 8:

- ✓

- miR-29 family (miR-29a, miR-29b, miR-29c), which suppress the expression of MMPs within ECM, thus decreasing collagen degradation and maintaining skin’s collagen levels; they also upregulate the expression of collagen genes (COL1A1, COL3A1) [132];

- ✓

- miR-146a, that interferes the NF-κB inflammatory pathway by targeting IL-1 receptor-associated kinase 1 (IRAK1) and TNF receptor-associated factor 6 (TRAF6); in mice models with UVB (ultraviolet B)-induced photoageing and inflammation, topical or injected miR-146a has reduced erythema, skin senescence markers and improved skin healing [133];

- ✓

- inhibitors of miR-34a, which up-regulate the expression of the sirtuin 1 (SIRT1) gene involved in longevity and DNA repair; in vitro, inhibitors of miR-34a have stimulated proliferation of cultured fibroblasts and have diminished senescence biomarkers [134];

- ✓

- inhibitors of miR-155, which have demonstrated the capacity to reduce the levels of inflammatory cytokines and pigmentation associated with chronic inflammation in aged human skin biopsies; inhibitors of miR-155 up-regulate the expression of the suppressor of cytokine signalling SOCS1 gene; SOCS1 protein inhibits the JAK/STAT pathway (Associated Janus Kinases/Signal Transducers and Activators of Transcription) and therefore it has a crucial role as negative regulator of cytokine signalling in immune disorders, cancer and inflammation [132];

- ✓

- miR-21, that targets inhibitors of skin regeneration and wound healing, such as phosphatase and tensin homologue (PTEN) and sprouty homologue 1 (SPRY1); miR-21 has stimulated fibroblasts’ division, collagen synthesis, keratinocyte migration and dermal matrix restoration, in in vivo murine wounds models [134];

- ✓

- miR-200c, that has reduced the levels of oxidative stress and has regulated epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) in in vitro studies, due to its capacity to target zinc finger transcription factors (E-box-binding homeobox 1 and 2, ZEB1 and ZEB2) [134].

Current hurdles in clinical progress of the miRNA-based skin anti-ageing therapies are related to:

- ✓

- targeted and efficient delivery across stratum corneum into dermal layers, using as carriers exosomes, lipid nanoparticles, hydrogels [135];

- ✓

- undesired gene silencing effects due to non-selective binding to genes responsible for essential cellular pathways [118,134];

- ✓

- limited long-term safety data [136];

- ✓

- in vivo rapid metabolic degradation by ribonucleases (RNases), requiring chemical modulations (e.g., 2′-O-methylation) [131,135];

- ✓

- lack of data on inter-individual variability of miRNA efficacy due to age, race, hormonal status and previous skin diseases [116,118,132].

Table 8.

The main microRNAs-based interventions preclinically and clinically tested as skin anti-ageing therapies (the arrow ↓ means decrease/inhibition; the arrow ↑ means increase/stimulation).

Table 8.

The main microRNAs-based interventions preclinically and clinically tested as skin anti-ageing therapies (the arrow ↓ means decrease/inhibition; the arrow ↑ means increase/stimulation).

| miRNA Approach | Regulation of Principal Target Gene(s) | Main Results | Stage | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| miR-21 | ↓ PTEN ↓ SPRY1 | ↑ fibroblast proliferation and healing; ↑ collagen synthesis; ↑ keratinocyte migration and dermal matrix restoration | Preclinical, in vivo murine wounds models | [134] |

| topical application of miR-21: improved skin elasticity and moisture; no major adverse effects | early clinical-phase I | [135] | ||

| miR-29a/b/c | ↓ MMPs ↑ COL1A1 | ↓ ECM degradation; ↑ collagen production; ↑ dermal structure; ↓ wrinkles | Preclinical: in vitro/human dermal fibroblasts; animal models | [132] |

| miR-146a | NF-κB inflammatory pathway: ↓ IRAK1 ↓ TRAF6 | topical or injected miR-146a: anti-inflammatory; ↓ UVB damage; ↓ erythema, skin senescence markers; ↑ skin healing | Preclinical: mice models of UVB-induced ageing | [133] |

| topical application of miR-146a-loaded nanoparticles: ↑ skin elasticity and moisture; no major adverse reactions | early clinical—Phase I | [135] | ||

| inhibitors of miR-34a | ↑ SIRT1 gene | ↑ fibroblasts’ proliferation and longevity; ↓ senescence biomarkers | Preclinical: in vitro fibroblasts cultures | [134] |

| inhibitors of miR-155 | ↑ SOCS1 | ↓ chronic inflammation; ↓ inflammatory cytokines; ↓ skin pigmentation | Preclinical: aged human skin samples | [132] |

| miR-200c | zinc finger E-box-binding homeobox ZEB1, ZEB2 | ↓ oxidative stress; ↑ epithelial–mesenchymal transition | Preclinical: in vitro | [94,130,134] |

6.3.3. Modulators of the Long Non-Coding RNA (lncRNA) HOTAIR in Skin Rejuvenation

HOTAIR (HOX Transcript Antisense RNA) is a long non-coding RNA (lncRNA) involved in chromatin remodelling, gene expression’s silencing by promoting histone H3K27 methylation, transcriptional regulation in specific genomic regions via interaction with EZH2, a catalytic subunit of the Polycomb Repressive Complex 2 (PRC2) [137,138]. The relevance of HOTAIR’s modulation for skin ageing derives from its involvement in dermal fibroblast senescence, wound healing impairment, skin cancer progression and epigenetic reprogramming resistance. Overexpression of HOTAIR is associated with fibroblast senescence, impaired ECM remodelling, fibrosis and pro-inflammatory signalling—features common to chronological ageing, photoageing and sclerotic skin conditions. High levels of HOTAIR contribute to UV-induced damage by promoting keratinocyte apoptosis and inflammatory cytokine expression [137,138,139]. However, in burn wound healing, HOTAIR supports regeneration by enhancing angiogenesis via miR126/Wnt/VEGF axis (Wnt/beta-catenin/Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor), indicating a context-dependent function [137,140]. Thus, inhibiting HOTAIR in acute injury may hinder recovery, highlighting the need for precise application and understanding of biological context and timing in therapeutic targeting [140].

HOTAIR is emerging as a multifunctional epigenetic regulator in the skin and its modulation, especially its inhibition in dermal fibroblasts and keratinocytes, may hold promise for anti-ageing skin strategies, particularly in photoaged and fibrotic skin [137,141]. Targeting HOTAIR by various means is illustrated in Table 9, besides of those featured by skin anti-ageing interventions assisted by gene-editing (CRISPR)-technology, and may restore youthful gene expression, reduce fibrosis and inflammatory signalling, enhance tissue regeneration pathways supporting skin rejuvenation [130,137,138,139,140,141,142,143].

Table 9.

Modulators of HOTAIR with anti-ageing relevance (the arrow ↓ means decrease/inhibition; the arrow ↑ means increase/stimulation).

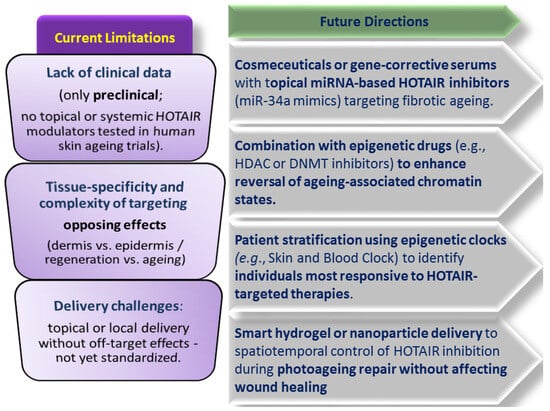

The role of HOTAIR modulators in skin rejuvenation strategies lies in their precision in targeting the age- and damage-associated epigenetic dysregulation in skin cells. Recent studies suggest that topical or systemic HOTAIR inhibitors might be integrated into epigenetic skin anti-ageing strategies, although most are still in preclinical (cellular or animal) stages [130]; human trials for topical or systemic HOTAIR modulators in skin ageing or rejuvenation are not yet reported. The clinical translation of the HOTAIR modulators will depend on topical delivery technologies, improved tissue specificity and the integration with epigenetic diagnostic tools. Current limitations and future research directions on integrating HOTAIR modulators into epigenetic skin rejuvenating strategies are illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

HOTAIR modulators in skin rejuvenation—current limitations and future research.

6.3.4. Gene Editing by CRISPR-Based Approaches in Skin Rejuvenation

Although not a therapy itself, Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR)-based technology is part of gene therapy and it has demonstrated precision in genome editing and epigenetic remodelling, as well as rejuvenation potential. Gene-editing by CRISPR acts by direct modification of ageing-related genes or regulatory sequences. CRISPR-direct (CRISPRd) controls gene expression by precisely blocking specific transcription factor binding sites on DNA, without cutting/altering the DNA sequence. CRISPRd uses a deactivated Cas9 protein (dCas9) guided to a specific DNA site by an RNA molecule, where it physically prevents the binding of the transcription factors to that particular DNA site. For instance, ex vivo CRISPR/Cas9 is able to edit ageing-related genes in fibroblasts by targeting p16INK4A or FOXO pathways. On the other hand, CRISPR-activation (CRISPRa) increases the expression of a specific gene by guiding an inactive CRISPR-Cas9 system (dCas9) fused with transcriptional activators to that gene’s promoter region, thus boosting its transcription and increasing the production of the gene’s encoded protein, also without altering the DNA sequence [144].

Although targeting transcriptional regulators (e.g., SOX5) via CRISPR have shown encouraging efficacy on correcting mutations and modulating ageing-related genes or rejuvenation pathways, the current data are largely preclinical, experimental as human skin applications, or are investigated in non-skin systems [144,145,146]. Furthermore, CRISPR/Cas9 faces critical ethical, regulatory, delivery and safety barriers before translation into dermatologic applications. Therefore, gene editing, although revolutionary, is still experimental in dermatology, requiring extensive safety and ethical evaluation [147]. Their combination with novel delivery methods like microneedles could further enhance gene editing specificity and safety, but need human clinical validation [144,145]. The main examples of the CRISPR-gene editing approaches in skin rejuvenation and a comparative analysis of this innovative approach are illustrated in Table 10 [127,144,145,146].

Table 10.

Comparative insights into main CRISPR- gene editing approaches in skin rejuvenation.

7. Skin Anti-Ageing Strategies Targeting Dysregulated Nutrient Sensing Pathways

Nutrient-sensing pathways comprising sirtuins, mTOR, IGF-1 and IGF-1 signalling (IIS) pathway, and AMPK, have a crucial role in mediating skin ageing [25,88]. Sirtuins, a family of signalling proteins essential in regulating metabolism, decline in aged subjects in parallel to reduced proliferation of dermal fibroblasts. Sirtuins have become especially activated during calorie/diet restriction and by the water-soluble form of vitamin B3—NAD. Applied topically, NAD has induced the expression of sirtuins and increased mitochondrial energetic chain, clinically reflected in improvement of skin ECM barrier and skin pigmentation [88,122].