Cracking the Skin Barrier: Models and Methods Driving Dermal Drug Delivery

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Dermal Delivery as an Alternative Route

The Skin: A Complex Barrier to Drug Delivery

3. Biological Models for Assessing Dermal Absorption

3.1. Ex Vivo Human Skin Models

Ex Vivo Human Skin in Bioequivalence Studies

3.2. Animal and Cell-Based Models in Dermal Research

4. Synthetic Skin Substitutes for Permeation Testing

4.1. Cultured Synthetic Human Skin

4.2. Strat-M® Membranes

5. Methods for Evaluating Drug Permeation

5.1. Quantitative Methods

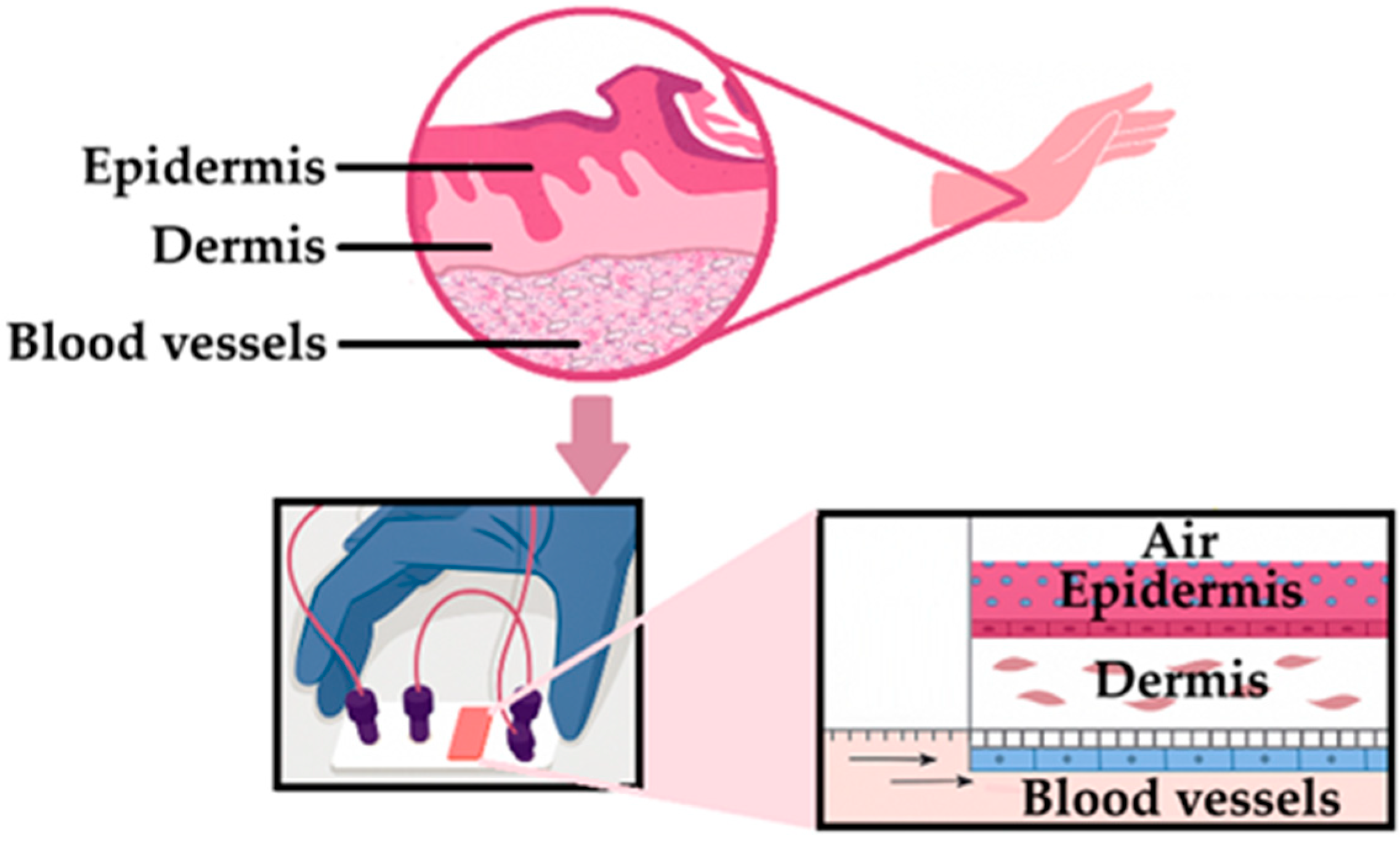

5.1.1. Diffusion Chambers

5.1.2. Skin Parallel Artificial Membrane Permeability Assay (Skin-PAMPA)

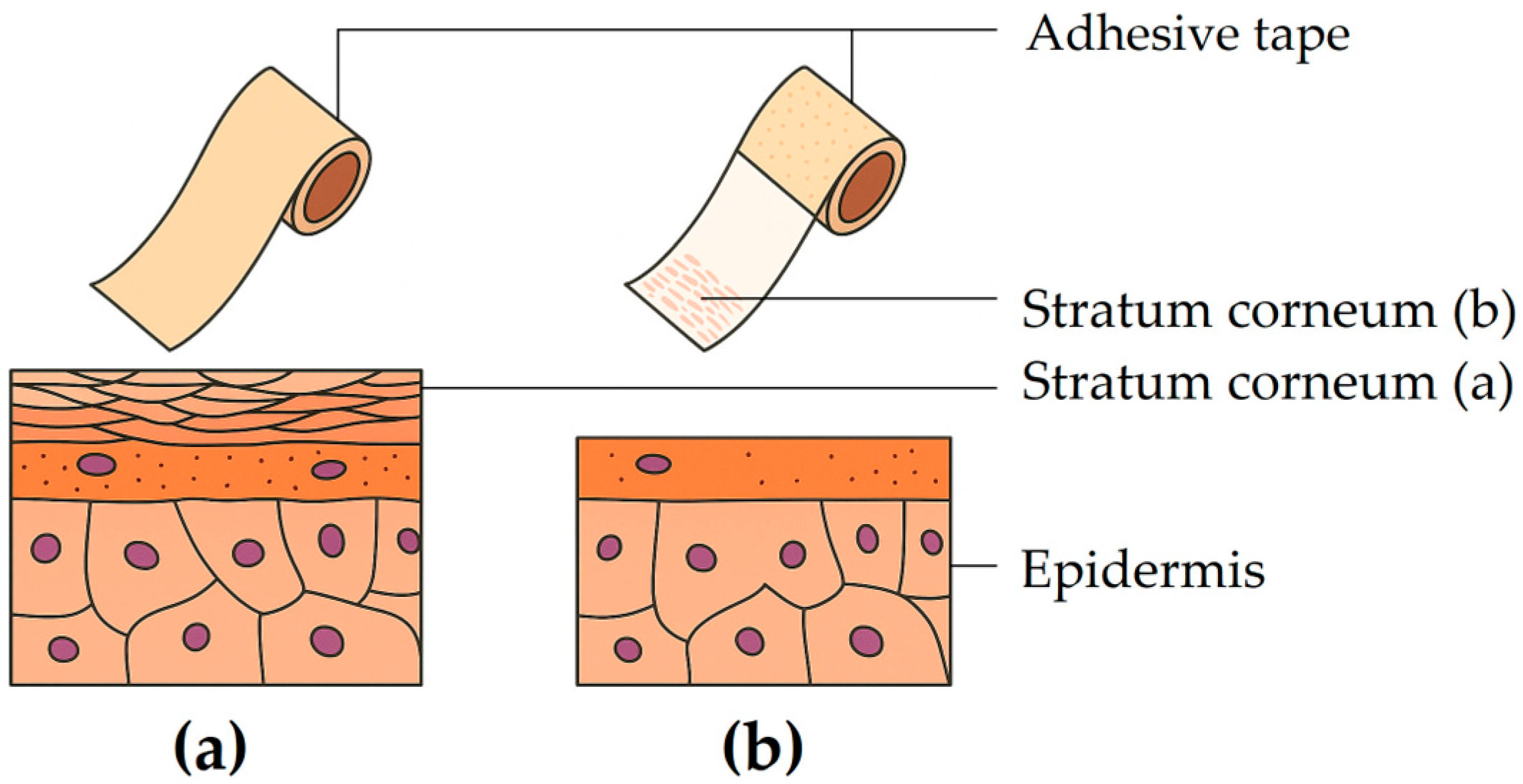

5.1.3. Tape Stripping

5.2. Semi-Quantitative or Qualitative Methods

5.2.1. Two-Photon Fluorescence Microscopy (2-PFM)

5.2.2. Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy (CLSM)

5.2.3. Confocal Raman Spectroscopy

5.2.4. Attenuated Total Reflectance–Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (ATR-FTIR)

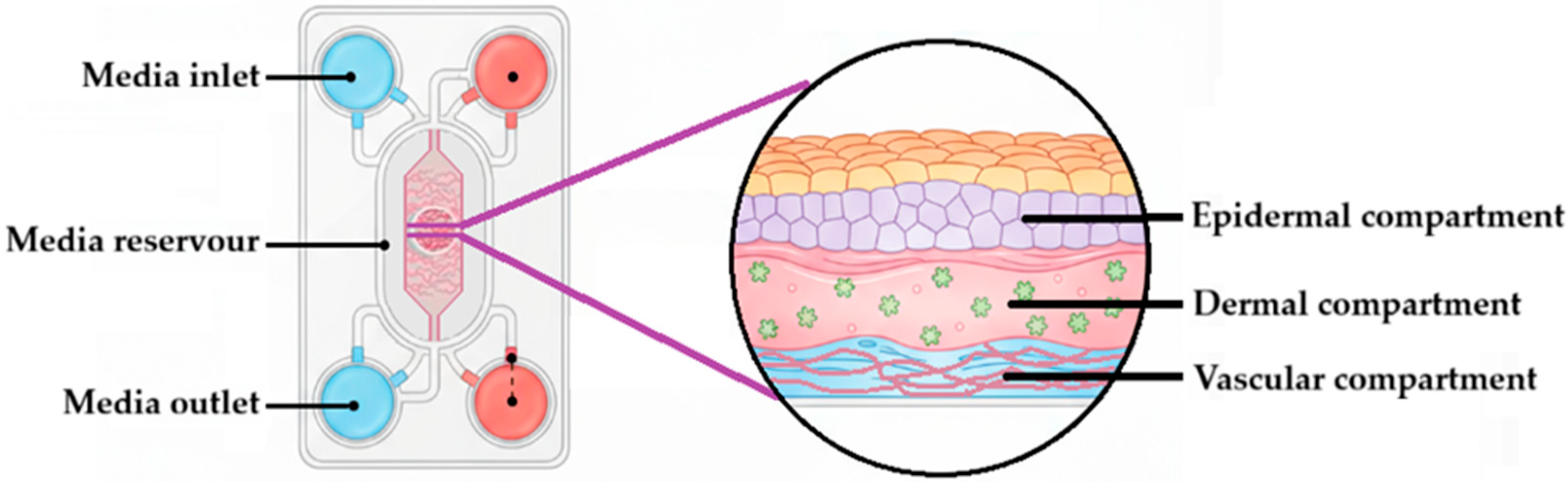

6. Recent Advances in Skin Models

7. Concluding Remarks

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ATR-FTIR | Attenuated Total Reflectance Fourier Transform Infrared |

| CLSM | Confocal laser scanning microscopy |

| CTB | Cutaneous tuberculosis |

| EMA | European Medicines Agency |

| FTSE | Full-thickness human skin equivalent |

| HPLC | High-pressure performance liquid chromatography |

| IPM | Isopropyl myristate |

| IVPT | In vitro skin permeation test |

| IVRT | In vitro release test |

| JSS | Steady-state flux |

| LPP | Long periodicity phase |

| LSE | Living skin equivalent |

| OECD | Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development |

| PAMPA | Parallel Artificial Membrane Permeability Assay |

| PEG | Polyethylene glycol |

| RHE | Reconstructed human epidermis |

| RSM | Reconstructed skin model |

| SC | Stratum corneum |

| SPP | Short periodicity phase |

| TB | Tuberculosis |

| 2-PFM | Two-photon fluorescence microscopy |

| US-EPA | United States Environmental Protection Agency |

| US FDA | United States Food and Drug Administration |

| ZnSe | Zinc selenide |

References

- Naik, A.; Kalia, Y.N.; Guy, R.H. Transdermal drug delivery: Overcoming the skin’s barrier function. Pharm. Sci. Technol. Today 2000, 3, 318–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellefroid, C.; Lechanteur, A.; Evrard, B.; Piel, G. Lipid gene nanocarriers for the treatment of skin diseases: Current state-of-the-art. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2019, 137, 95–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, T.; Talukder, M.M.U. Chemical Enhancer: A Simplistic Way to Modulate Barrier Function of the Stratum Corneum. Adv. Pharm. Bull. 2018, 8, 169–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jepps, O.G.; Dancik, Y.; Anissimov, Y.G.; Roberts, M.S. Modeling the human skin barrier—Towards a better understanding of dermal absorption. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2013, 65, 152–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franz, T.J.; Lehman, P.A.; Raney, S.G. Use of Excised Human Skin to Assess the Bioequivalence of Topical Products. Skin Pharmacol. Physiol. 2009, 22, 276–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abd, E.; Yousef, S.A.; Pastore, M.N.; Telaprolu, K.; Mohammed, Y.H.; Namjoshi, S.; Grice, J.E.; Roberts, M.S. Skin models for the testing of transdermal drugs. Clin. Pharmacol. 2016, 8, 163–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, E.C.; Maibach, H.I. Animal models for percutaneous absorption. J. Appl. Toxicol. 2015, 35, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kichou, H.; Bonnier, F.; Dancik, Y.; Bakar, J.; Michael-Jubeli, R.; Caritá, A.C.; Perse, X.; Soucé, M.; Rapetti, L.; Tfayli, A.; et al. Strat-M® positioning for skin permeation studies: A comparative study including EpiSkin® RHE, and human skin. Int. J. Pharm. 2023, 647, 123488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinkó, B.; Garrigues, T.M.; Balogh, G.T.; Nagy, Z.K.; Tsinman, O.; Avdeef, A.; Takács-Novák, K. Skin-PAMPA: A new method for fast prediction of skin penetration. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2012, 45, 698–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruela, A.L.M.; Perissinato, A.G.; de Sousa Lino, M.E.; Mudrik, P.S.; Pereira, G.R. Evaluation of skin absorption of drugs from topical and transdermal formulations. Braz. J. Pharm. Sci. 2016, 52, 527–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragicevic, N.; Maibach, H.I. Percutaneous Penetration Enhancers Drug Penetration Into/Through the Skin, 1st ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klang, V.; Schwarz, J.C.; Lenobel, B.; Nadj, M.; Auböck, J.; Wolzt, M.; Valenta, C. In vitro vs. in vivo tape stripping: Validation of the porcine ear model and penetration assessment of novel sucrose stearate emulsions. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2012, 80, 604–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.W.; Monteiro-Riviere, N.A. Use of confocal microscopy for nanoparticle drug delivery through skin. J. Biomed. Opt. 2012, 18, 061214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Förster, M.; Bolzinger, M.A.; Montagnac, G.; Briançon, S. Confocal Raman microspectroscopy of the skin. Eur. J. Dermatol. 2011, 21, 851–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreiner, V.; Gooris, G.S.; Pfeiffer, S.; Lanzendörfer, G.; Wenck, H.; Diembeck, W.; Proksch, E.; Bouwstra, J. Barrier characteristics of different human skin types investigated with X-ray diffraction, lipid analysis, and electron microscopy imaging. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2000, 114, 654–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofland, H.E.; Bouwstra, J.A.; Boddé, H.E.; Spies, F.; Junginger, H.E. Interactions between liposomes and human stratum corneum in vitro: Freeze fracture electron microscopical visualization and small angle X-ray scattering studies. Br. J. Dermatol. 1995, 132, 853–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh Malik, D.; Mital, N.; Kaur, G. Topical drug delivery systems: A patent review. Expert. Opin. Ther. Pat. 2016, 26, 213–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhowmik, D.; Gopinath, H.; Kumar, B.P.; Duraivel, S.; Kumar, K.P.S. Recent Advances in Novel Topical Drug Delivery System. Pharma. Innov. J. 2012, 1, 12–31. [Google Scholar]

- Godin, B.; Touitou, E. Dermal and Transdermal Delivery. In Encyclopedia of Nanotechnology; Bhushan, B., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 517–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, T.C.; Gelain, A.B.; Rosa, J.; Cardoso, S.G.; Caon, T. Cocrystallization as a novel approach to enhance the transdermal administration of meloxicam. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2018, 123, 184–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anjani, Q.K.; Sabri, A.H.B.; Hutton, A.J.; Cárcamo-Martínez, Á.; Wardoyo, L.A.H.; Mansoor, A.Z.; Donnelly, R.F. Microarray patches for managing infections at a global scale. J. Control. Release 2023, 359, 97–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozińska, M.; Augustynowicz-Kopéc, E.; Gamian, A.; Chudzik, A.; Paściak, M.; Zdziarski, P. Cutaneous and pulmonary tuberculosis—Diagnostic and therapeutic difficulties in a patient with autoimmunity. Pathogens 2023, 12, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, K.H.; Alcantara, C.A.; Glassman, I.; May, N.; Mundra, A.; Mukundan, A.; Urness, B.; Yoon, S.; Sakaki, R.; Dayal, S.; et al. Cutaneous Manifestations of Mycobacterium tuberculosis: A Literature Review. Pathogens 2023, 12, 920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brito, A.C.; Oliveira, C.M.M.; Unger, D.A.; Bittencourt, M.J.S. Cutaneous tuberculosis: Epidemiological, clinical, diagnostic and therapeutic update. An. Bras. Dermatol. 2022, 97, 129–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopalaswamy, R.; Dusthackeer, V.N.A.; Kannayan, S.; Subbian, S. Extrapulmonary Tuberculosis—An Update on the Diagnosis, Treatment and Drug Resistance. J. Respir. 2021, 1, 141–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, A. Advancements in tuberculosis treatment: From epidemiology to innovative therapies. Int. J. Sci. Res. 2024, 13, 206–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, N.; Song, H.; Li, H.; Wen, J.; Tan, Y.; Zheng, W. Design, characterization and comparison of transdermal delivery of colchicine via borneol-chemically-modified and borneol-physically-modified ethosome. Drug Deliv. 2019, 26, 70–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezike, T.C.; Okpala, U.S.; Onoja, U.L.; Nwike, C.P.; Ezeako, E.C.; Okpara, O.J.; Okoroafor, C.C.; Eze, S.C.; Kalu, O.L.; Odoh, E.C.; et al. Advances in drug delivery systems, challenges and future directions. Heliyon 2023, 9, e17488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gratieri, T.; Alberti, I.; Lapteva, M.; Kalia, Y.N. Next generation intra- and transdermal therapeutic systems: Using non- and minimally-invasive technologies to increase drug delivery into and across the skin. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2013, 50, 609–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prausnitz, M.R.; Mitragotri, S.; Langer, R. Current status and future potential of transdermal drug delivery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2004, 3, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nan, L.; Liu, C.; Li, Q.; Wan, X.; Guo, J.; Quan, P.; Fang, L. Investigation of the enhancement effect of the natural transdermal permeation enhancers from Ledum palustre L. var. angustum N. Busch: Mechanistic insight based on interaction among drug, enhancers and skin. Eur. J. Pharm Sci. 2018, 124, 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ita, K. Transdermal Delivery of Drugs with Microneedles—Potential and Challenges. Pharmaceutics 2015, 7, 90–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez-Ojeda, W.; Pandey, A.; Alhajj, M.; Oakley, A.M. Anatomy, Skin (Integument). In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2022. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK441980/ (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Murphy, G.F. Histology of the skin. In Lever’s Histopathology of the Skin; Elenitsas, R., Jaworsky, C., Johnson, B., Eds.; Lippincott-Raven: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1997; pp. 5–50. [Google Scholar]

- Mathers, A.R.; Larregina, A.T. Professional antigen-presenting cells of the skin. Immunol. Res. 2006, 36, 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, D.H. Overview of Biology, Development, and Structure of Skin. In Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine, 8th ed.; Wolff, K., Goldsmith, L.A., Katz, S.I., Gilchrest, B.A., Paller, A.S., Leffell, D.J., Eds.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 57–73. [Google Scholar]

- James, W.D.; Berger, T.G.; Elston, D.M. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology, 10th ed.; Elsevier Saunders: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, S.M.; Williams, M.L.; Feingold, K.R.; Elias, P.M. Pathobiology of the stratum corneum. West. J. Med. 1993, 158, 279–285. [Google Scholar]

- Haake, A.R.; Hollbrook, K. The Structure and Development of Skin. In Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine, 5th ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1999; pp. 70–111. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Xu, W.; Liang, Y.; Wang, H. The application of skin metabolomics in the context of transdermal drug delivery. Pharmacol. Rep. 2017, 69, 252–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, A.; Ahmed, A.B. Natural permeation enhancer for transdermal drug delivery system and permeation evaluation: A review. Asian J. Pharm. Clin. Res. 2017, 10, 5–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burger, C.; Gerber, M.; du Preez, J.L.; du Plessis, J. Optimised transdermal delivery of pravastatin. Int. J. Pharm. 2015, 496, 518–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Staden, D.; Haynes, R.K.; Viljoen, J.M. Adapting Clofazimine for Treatment of Cutaneous Tuberculosis by Using Self-Double-Emulsifying Drug Delivery Systems. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panico, A.; Serio, F.; Bagordo, F.; Grassi, T.; Idolo, A.; De Giorgi, M.; Guido, M.; Congedo, M.; De Donno, A. Skin safety and health prevention: An overview of chemicals in cosmetic products. J. Prev. Med. Hyg. 2019, 60, E50–E57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, J.; Maibach, H.I. Experimental Models in Predicting Topical Antifungal Efficacy: Practical Aspects and Challenges. Skin Pharmacol. Physiol. 2009, 22, 231–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walters, K.A.; Watkinson, A.C.; Brain, K.R. In vitro skin permeation evaluation: The only realistic option. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 1998, 20, 307–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Manda, P.; Pavurala, N.; Khan, M.A.; Krishnaiah, Y.S.R. Development and validation of in vitro-in vivo correlation (IVIVC) for estradiol transdermal drug delivery systems. J. Control. Release 2015, 210, 58–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandby-Møller, J.; Poulsen, T.; Wulf, H.C. Epidermal Thickness at Different Body Sites: Relationship to Age, Gender, Pigmentation, Blood Content, Skin Type and Smoking Habits. Acta Derm. Venereol. 2003, 83, 410–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marrakchi, S.; Maibach, H.I. Biophysical parameters of skin: Map of human face, regional, and age-related differences. Contact Dermat. 2007, 57, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shriner, D.L.; Maibach, H.I. Regional Variation of Nonimmunologic Contact Urticaria: Functional Map of the Human Face. Skin Pharmacol. 1996, 9, 312–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lampe, M.A.; Burlingame, A.L.; Whitney, J.; Williams, M.L.; Brown, B.E.; Roitman, E.; Elias, P.M. Human stratum corneum lipids: Characterization and regional variations. J. Lipid Res. 1983, 24, 120–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boer, M.; Duchnik, E.; Maleszka, R.; Marchlewicz, M. Structural and biophysical characteristics of human skin in maintaining proper epidermal barrier function. Postepy. Dermatol. Alergol. 2016, 33, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Küchler, S.; Strüver, K.; Friess, W. Reconstructed skin models as emerging tools for drug absorption studies. Expert Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 2013, 9, 1255–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdayem, R.; Roussel, L.; Zaman, N.; Pirot, F.; Gilbert, E.; Haftek, M. Deleterious effects of skin freezing contribute to variable outcomes of the predictive drug permeation studies using hydrophilic molecules. Exp. Dermatol. 2015, 24, 972–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahlström, L.A.; Cross, S.E.; Mills, P.C. The effects of freezing skin on transdermal drug penetration kinetics. J. Vet. Pharmacol. Ther. 2007, 30, 456–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Liang, K.; Meng, X.; Ma, C.; Wang, Q. The Influence of various freezing-thawing methods of skin on drug permeation and skin barrier function. AAPS J. 2024, 26, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dancik, Y.; Kichou, H.; Eklouh-Molinier, C.; Soucé, M.; Munnier, E.; Chourpa, I.; Bonnier, F. Freezing Weakens the Barrier Function of Reconstructed Human Epidermis as Evidenced by Raman Spectroscopy and Percutaneous Permeation. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbero, A.M.; Frasch, H.F. Effect of frozen human epidermis storage duration and cryoprotectant on barrier function using two model compounds. Skin Pharmacol. Physiol. 2016, 29, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sintov, A.C. Cumulative evidence of the low reliability of frozen/thawed pig skin as a model for in vitro percutaneous permeation testing. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2017, 102, 261–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sintov, A.C.; Greenberg, I. Comparative percutaneous permeation study using caffeine-loaded microemulsion showing low reliability of the frozen/thawed skin models. Int. J. Pharm. 2014, 471, 516–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne, O.J.; Graham, S.J.; Dalton, C.H.; Spencer, P.M.; Mansson, R.; Jenner, J.; Azeke, J.; Braue, E. The effects of sulfur mustard exposure and freezing on transdermal penetration of tritiated water through ex vivo pig skin. Toxicol. In Vitro 2013, 27, 79–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicoli, S.; Santi, P. Suitability of excised rabbit ear skin—Fresh and frozen—For evaluating transdermal permeation of estradiol. Drug Deliv. 2007, 14, 195–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sintov, A.C.; Botner, S. Transdermal drug delivery using microemulsion and aqueous systems: Influence of skin storage conditions on the in vitro permeability of diclofenac from aqueous vehicle systems. Int. J. Pharm. 2006, 311, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdanian, M. The effect of freezing on cattle skin permeability. Int. J. Pharm. 1994, 103, 93–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadzija, B.W.; Ruddy, S.B.; Ballenger, E.S. Effect of freezing on iontophoretic transport through hairless rat skin. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 1992, 44, 387–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemppainen, B.W.; Riley, R.T.; Pace, J.G.; Hoerr, F.J. Effects of skin storage conditions and concentration of applied dose on [3H]T-2 toxin penetration through excised human and monkey skin. Food Chem. Toxicol. 1986, 24, 221–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Messager, S.; Hann, A.C.; Goddard, P.A.; Dettmar, P.W.; Maillard, J.Y. Assessment of skin viability: Is it necessary to use different methodologies? Skin Res. Technol. 2003, 9, 321–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wester, R.C.; Christoffel, J.; Hartway, T.; Poblete, N.; Maibach, H.I.; Forsell, J. Human cadaver skin viability for in vitro percutaneous absorption: Storage and detrimental effects of heat-separation and freezing. Pharm. Res. 1998, 15, 82–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cross, S.E.; Magnusson, B.M.; Winckle, G.; Anissimov, Y.; Roberts, M.S. Determination of the effect of lipophilicity on the in vitro permeability and tissue reservoir characteristics of topically applied solutes in human skin layers. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2003, 120, 759–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haigh, J.M.; Smith, E.W. The selection and use of natural and synthetic membranes for in vitro diffusion experiments. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 1994, 2, 311–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cross, S.E.; Roberts, M.S. Use of in vitro human skin membranes to model and predict the effect of changing blood flow on the flux and retention of topically applied solutes. J. Pharm. Sci. 2008, 97, 3442–3450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Täuber, A.; Müller-Goymann, C.C. In vitro model of infected stratum corneum for the efficacy evaluation of poloxamer 407-based formulations of ciclopirox olamine against Trichophyton rubrum as well as differential scanning calorimetry and stability studies. Int. J. Pharm. 2015, 494, 304–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anissimov, Y.G.; Roberts, M.S. Diffusion modeling of percutaneous absorption kinetics: 3. Variable diffusion and partition coefficients, consequences for stratum corneum depth profiles and desorption kinetics. J. Pharm. Sci. 2004, 93, 470–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anissimov, Y.G.; Roberts, M.S. Diffusion modelling of percutaneous absorption kinetics: 4. Effects of a slow equilibration process within stratum corneum on absorption and desorption kinetics. J. Pharm. Sci. 2009, 98, 772–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raney, S.G.; Franz, T.J.; Lehman, P.A.; Lionberger, R.; Chen, M.L. Pharmacokinetics-Based Approaches for Bioequivalence Evaluation of Topical Dermatological Drug Products. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2015, 54, 1095–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehman, P.A.; Franz, T.J. Assessing topical bioavailability and bioequivalence: A comparison of the in vitro permeation test and the vasoconstrictor assay. Pharm. Res. 2014, 31, 3529–3537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skelly, J.P.; Shah, V.P.; Maibach, H.I.; Guy, R.H.; Wester, R.C.; Flynn, G.; Yacobi, A. FDA and AAPS Report of the Workshop on Principles and Practices of In Vitro Percutaneous Penetration Studies: Relevance to Bioavailability and Bioequivalence. Pharm. Res. 1987, 4, 265–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). In Vitro Permeation Test Studies for Topical Products Submitted in ANDAs—Guidance for Industry; Draft Guidance; U.S. FDA: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2022. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/media/162475/download (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- European Medicines Agency (EMA). Guideline on Quality and Equivalence of Locally Applied, Locally Acting Cutaneous Products; EMA/CHMP/QWP/708282/2018; European Medicines Agency: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/quality-equivalence-locally-applied-locally-acting-cutaneous-products-scientific-guideline (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- Shah, V.P. Topical Dermatological Drug Product NDAs and ANDAs: In Vivo Bioavailability, Bioequivalence, In Vitro Release and Associated Studies; US Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration: Rockville, MD, USA, 1998; pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Alberti, I.; Kalia, Y.N.; Naik, A.; Bonny, J.D.; Guy, R.H. In vivo assessment of enhanced topical delivery of terbinafine to human stratum corneum. J. Control. Release 2001, 71, 319–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicoli, S.; Bunge, A.L.; Delgado-Charro, M.B.; Guy, R.H. Dermatopharmacokinetics: Factors influencing drug clearance from the stratum corneum. Pharm. Res. 2009, 26, 865–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holbrook, K.A.; Odland, G.F. Regional differences in the thickness (cell layers) of the human stratum corneum: An ultrastructural analysis. J. Investig. Dermatol. 1974, 62, 415–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lintzeri, D.A.; Karimian, N.; Blume-Peytavi, U.; Kottner, J. Epidermal thickness in healthy humans: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2022, 36, 1191–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, S.M.; Pandey, K.; Lahoti, A.; Rao, P.K. Evaluation of skin and subcutaneous tissue thickness at insulin injection sites in Indian, insulin naïve, type-2 diabetic adult population. Indian J. Endocrinol. Metab. 2013, 17, 864–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro-Riviere, N.A.; Bristol, D.G.; Manning, T.O.; Rogers, R.A.; Riviere, J.E. Interspecies and Interregional Analysis of the Comparative Histologic Thickness and Laser Doppler Blood Flow Measurements at Five Cutaneous Sites in Nine Species. J. Investig. Dermatol. 1990, 95, 582–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dittus, W.P.; Gunathilake, K.A. Validating skinfold thickness as a proxy to estimate total body fat in wild toque macaques (Macaca sinica) using the mass of dissected adipose tissue. Am. J. Primatol. 2015, 77, 618–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicoli, S.; Padula, C.; Aversa, V.; Vietti, B.; Wertz, P.W.; Millet, A.; Falson, F.; Govoni, P.; Santi, P. Characterization of rabbit ear skin as a skin model for in vitro transdermal permeation experiments: Histology, lipid composition and permeability. Skin Pharmacol. Physiol. 2008, 21, 218–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacha, N.; Weisbach, N.; Pöhler, A.S.; Demmerle, N.; Haltner, E. Comparisons of the Histological Morphology and In Vitro Percutaneous Absorption of Caffeine in Shed Snake Skin and Human Skin. Slov. Vet. Res. 2020, 57, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, G.M.; Yardley, H.J. Lipid compositions of cells isolated from pig, human, and rat epidermis. J. Lipid Res. 1975, 16, 434–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobi, U.; Kaiser, M.; Toll, R.; Mangelsdorf, S.; Audring, H.; Otberg, N.; Sterry, W.; Lademann, J. Porcine ear skin: An in vitro model for human skin. Skin Res. Technol. 2007, 13, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wester, R.C.; Maibach, H.I. In vivo methods for percutaneous absorption measurements. J. Toxicol. Cutaneous Ocul. Toxicol. 2001, 20, 411–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lademann, J.; Richter, H.; Meinke, M.; Sterry, W.; Patzelt, A. Which skin model is the most appropriate for the investigation of topically applied substances into the hair follicles? Skin Pharmacol. Physiol. 2010, 23, 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caussin, J.; Gooris, G.S.; Janssens, M.; Bouwstra, J.A. Lipid organization in human and porcine stratum corneum differs widely, while lipid mixtures with porcine ceramides model human stratum corneum lipid organization very closely. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2008, 1778, 1472–1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldsmith, L.A. Physiology, Biochemistry, and Molecular Biology of the Skin, 2nd ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Dick, I.P.; Scott, R.C. Pig ear skin as an in-vitro model for human skin permeability. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 1992, 44, 640–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, S.; Zhao, K.; Singh, J. In vitro permeability and binding of hydrocarbons in pig ear and human abdominal skin. Drug Chem. Toxicol. 2002, 25, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, K.; Sugibayashi, K.; Morimoto, Y. Species differences in percutaneous absorption of nicorandil. J. Pharm. Sci. 1991, 80, 104–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scheuplein, R.J.; Blank, I.H. Permeability of the skin. Physiol. Rev. 1971, 51, 702–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todo, H. Transdermal permeation of drugs in various animal species. Pharmaceutics 2017, 9, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y. Research on transdermal penetration of rotigotine transdermal patch. Trans. Mater. Biotechnol. Life Sci. 2025, 8, 501–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barber, E.D.; Teetsel, N.M.; Kolberg, K.F.; Guest, D. A comparative study of the rates of in vitro percutaneous absorption of eight chemicals using rat and human skin. Fundam. Appl. Toxicol. 1992, 19, 493–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chowhan, Z.T.; Pritchard, R. Effect of surfactants on percutaneous absorption of naproxen I: Comparisons of rabbit, rat, and human excised skin. J. Pharm. Sci. 1978, 67, 1272–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hughes, M.F.; Edwards, B.C. In vitro dermal absorption of pyrethroid pesticides in human and rat skin. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2010, 246, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmook, F.P.; Meingassner, J.G.; Billich, A. Comparison of human skin or epidermis models with human and animal skin in in-vitro percutaneous absorption. Int. J. Pharm. 2001, 215, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Ravenzwaay, B.; Leibold, E. A comparison between in vitro rat and human and in vivo rat skin absorption studies. Hum. Exp. Toxicol. 2004, 23, 421–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicoli, S.; Cappellazzi, M.; Colombo, P.; Santi, P. Characterization of the permselective properties of rabbit skin during transdermal iontophoresis. J. Pharm. Sci. 2003, 92, 1482–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, R.C.; Corrigan, M.A.; Smith, F.; Mason, H. The influence of skin structure on permeability: An intersite and interspecies comparison with hydrophilic penetrants. J. Investig. Dermatol. 1991, 96, 921–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicoli, S.; Rimondi, S.; Colombo, P.; Santi, P. Physical and chemical enhancement of transdermal delivery of triptorelin. Pharm. Res. 2001, 18, 1634–1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artusi, M.; Nicoli, S.; Colombo, P.; Bettini, R.; Sacchi, A.; Santi, P. Effect of chemical enhancers and iontophoresis on thiocolchicoside permeation across rabbit and human skin in vitro. J. Pharm. Sci. 2004, 93, 2431–2438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Best, A.; Kamilar, J.M. The evolution of eccrine sweat glands in human and nonhuman primates. J. Hum. Evol. 2018, 117, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rigg, P.C.; Barry, B.W. Shed snake skin and hairless mouse skin as model membranes for human skin during permeation studies. J. Investig. Dermatol. 1990, 94, 235–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Megrab, N.A.; Williams, A.C.; Barry, B.W. Oestradiol permeation through human skin and silastic membrane: Effects of propylene glycol and supersaturation. J. Control. Release 1995, 36, 277–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neupane, R.; Boddu, S.H.S.; Renukuntla, J.; Babu, R.J.; Tiwari, A.K. Alternatives to Biological Skin in Permeation Studies: Current Trends and Possibilities. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ponec, M. In vitro cultured human skin cells as alternatives to animals for skin irritancy screening. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 1992, 14, 245–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Gele, M.; Geusens, B.; Brochez, L.; Speeckaert, R.; Lambert, J. Three-dimensional skin models as tools for transdermal drug delivery: Challenges and limitations. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 2011, 8, 705–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wever, B.D.; Petersohn, D.; Mewes, K.R. Overview of human three-dimensional (3D) skin models used for dermal toxicity assessment Part 1. Househ. Pers. Care Today 2013, 8, 18–22. [Google Scholar]

- Varga-Medveczky, Z.; Kocsis, D.; Naszlady, M.B.; Fónagy, K.; Erdő, F. Skin-on-a-Chip Technology for Testing Transdermal Drug Delivery-Starting Points and Recent Developments. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 1852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MatTek. Available online: https://www.mattek.com/reference-library/epiderm-full-thickness-epiderm-ft-a-dermal-epidermal-skin-model-with-a-fully-developed-basement-membrane/ (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- EPISKIN L’ORÉAL Research & Innovation. Available online: https://www.episkin.com/About-us (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- Cultured Human Tissue for Research Use LabCyte EPI-MODEL. Available online: https://www.jpte.co.jp/en/business/LabCyte/epi-model/index.html (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- StratiCELL Reconstructed Human Epidermis. Available online: https://straticell.com/reconstructed-human-epidermis/ (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- Organogenesis Apligraf® Living Cellular Skin Substitute. Available online: https://www.apligraf.com/ (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- Tfayli, A.; Bonnier, F.; Farhane, Z.; Libong, D.; Byrne, H.J.; Baillet-Guffroy, A. Comparison of structure and organization of cutaneous lipids in a reconstructed skin model and human skin: Spectroscopic imaging and chromatographic profiling. Exp. Dermatol. 2014, 23, 441–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakoersing, V.S.; Gooris, G.S.; Mulder, A.; Rietveld, M.; El Ghalbzouri, A.; Bouwstra, J.A. Unraveling barrier properties of three different in-house human skin equivalents. Tissue Eng. Part C Methods 2012, 18, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klicks, J.; von Molitor, E.; Ertongur-Fauth, T.; Rudolf, R.; Hafner, M. In vitro skin three-dimensional models and their applications. J. Cell. Biotechnol. 2017, 3, 21–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teimouri, A.; Yeung, P.; Agu, R. 2D vs. 3D Cell Culture Models for In Vitro Topical (Dermatological) Medication Testing. In Cell Culture; Mehanna, R.A., Ed.; IntechOpen: Rijeka, Croatia, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niehues, H.; Bouwstra, J.A.; El Ghalbzouri, A.; Brandner, J.M.; Zeeuwen, P.L.J.M.; van den Bogaard, E.H. 3D skin models for 3R research: The potential of 3D reconstructed skin models to study skin barrier function. Exp. Dermatol. 2018, 27, 501–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haq, A.; Goodyear, B.; Ameen, D.; Joshi, V.; Michniak-Kohn, B. Strat-M® synthetic membrane: Permeability comparison to human cadaver skin. Int. J. Pharm. 2018, 547, 432–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arce, F.J.; Asano, N.; See, G.L.; Itakura, S.; Todo, H.; Sugibayashi, K. Usefulness of Artificial Membrane, Strat-M®, in the Assessment of Permeation from Complex Vehicles in Finite Dose Conditions. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchida, T.; Kadhum, W.R.; Kanai, S.; Todo, H.; Oshizaka, T.; Sugibayashi, K. Prediction of skin permeation by chemical compounds using the artificial membrane, Strat-M™. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2015, 67, 113–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anjani, Q.K.; Nainggolan, A.D.C.; Li, H.; Miatmoko, A.; Larrañeta, E.; Donnelly, R.F. Parafilm® M and Strat-M® as skin simulants in in vitro permeation of dissolving microarray patches loaded with proteins. Int. J. Pharm. 2024, 655, 124071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zsikó, S.; Csányi, E.; Kovács, A.; Budai-Szűcs, M.; Gácsi, A.; Berkó, S. Methods to Evaluate Skin Penetration In Vitro. Sci. Pharm. 2019, 87, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Zhiti, A.; Barba-Bon, A.; Hennig, A.; Nau, W.M. Real-Time Parallel Artificial Membrane Permeability Assay Based on Supramolecular Fluorescent Artificial Receptors. Front. Chem. 2020, 8, 597927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anissimov, Y.G.; Jepps, O.G.; Dancik, Y.; Roberts, M.S. Mathematical and pharmacokinetic modelling of epidermal and dermal transport processes. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2013, 65, 169–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anissimov, Y.G.; Roberts, M.S. Diffusion modeling of percutaneous absorption kinetics: 2. Finite vehicle volume and solvent deposited solids. J. Pharm. Sci. 2001, 90, 504–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anissimov, Y.G.; Roberts, M.S. Diffusion modeling of percutaneous absorption kinetics. 1. Effects of flow rate, receptor sampling rate, and viable epidermal resistance for a constant donor concentration. J. Pharm. Sci. 2000, 88, 1201–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todo, H.; Oshizaka, T.; Kadhum, W.R.; Sugibayashi, K. Mathematical model to predict skin concentration after topical application of drugs. Pharmaceutics 2013, 5, 634–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crank, J. The Mathematics of Diffusion, 2nd ed.; Clarendon Press: Oxford, UK, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Ueda, C.T.; Shah, V.P.; Derdzinski, K.; Ewing, G.; Flynn, G.; Maibach, H.; Marques, M.; Rytting, H.; Shaw, S.; Thakker, K.; et al. Topical and Transdermal Drug Products. Dissolution Technol. 2009, 17, 12–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serpe, L.; Muniz, B.V.; Santos, C.P.D.; da Silva, C.B.; Volpato, M.C.; Groppo, F.C.; Lopez, R.F.V.; Franz-Montan, M. Full-Thickness Intraoral Mucosa Barrier Models for In Vitro Drug- Permeation Studies Using Microneedles. J. Pharm. Sci. 2019, 108, 1756–1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, W.R.; Hsiao, C.Y.; Huang, T.H.; Wang, C.L.; Alalaiwe, A.; Chen, E.L.; Fang, J.Y. Post-irradiation recovery time strongly influences fractional laser-facilitated skin absorption. Int. J. Pharm. 2019, 564, 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kansy, M.; Senner, F.; Gubernator, K. Physicochemical high throughput screening: Parallel artificial membrane permeation assay in the description of passive absorption processes. J. Med. Chem. 1998, 41, 1007–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ottaviani, G.; Martel, S.; Carrupt, P.A. Parallel Artificial Membrane Permeability Assay: A New Membrane for the Fast Prediction of Passive Human Skin Permeability. J. Med. Chem. 2006, 49, 3948–3954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinkó, B.; Pálfi, M.; Béni, S.; Kökösi, J.; Takács-Novák, K. Synthesis and characterization of long-chain tartaric acid diamides as novel ceramide-like compounds. Molecules 2010, 15, 824–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinkó, B.; Vizserálek, G.; Takács-Novák, K. Skin PAMPA: Application in practice. ADMET DMPK 2015, 2, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Selzer, D.; Abdel-Mottaleb, M.M.A.; Hahn, T.; Schaefer, U.F.; Neumann, D. Finite and infinite dosing: Difficulties in measurements, evaluations and predictions. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2013, 65, 278–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mojumdar, E.H.; Pham, Q.D.; Topgaard, D.; Sparr, E. Skin hydration: Interplay between molecular dynamics, structure and water uptake in the stratum corneum. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 15712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morin, M.; Ruzgas, T.; Svedenhag, P.; Anderson, C.D.; Ollmar, S.; Engblom, J.; Björklund, S. Skin hydration dynamics investigated by electrical impedance techniques in vivo and in vitro. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 17218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahinfar, S.; Maibach, H. In vitro percutaneous penetration test overview. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1102433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, H.; Maibach, H.I. Effects of skin occlusion on percutaneous absorption: An overview. Skin Pharmacol. Appl. Skin Physiol. 2001, 14, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treffel, P.; Muret, P.; Muret-D’Aniello, P.; Coumes-Marquet, S.; Agache, P. Effect of occlusion on in vitro percutaneous absorption of two compounds with different physicochemical properties. Skin Pharmacol. 1992, 5, 108–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhai, H.; Maibach, H.I. Occlusion vs. skin barrier function: Occlusion versus skin barrier function. Skin Res. Technol. 2002, 8, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franz, T.J. Percutaneous absorption on the relevance of in vitro data. J. Investig. Dermatol. 1975, 64, 190–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franz, T.J. The finite dose technique as a valid in vitro model for the study of percutaneous absorption in man. Curr. Probl. Dermatol. 1978, 7, 58–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sesto Cabral, M.E.; Ramos, A.N.; Cabrera, C.A.; Valdez, J.C.; González, S.N. Equipment and method for in vitro release measurements on topical dosage forms. Pharm. Dev. Technol. 2015, 20, 619–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza Teixeira, L.; Vila Chagas, T.; Alonso, A.; Gonzalez-Alvarez, I.; Bermejo, M.; Polli, J.; Rezende, K.R. Biomimetic Artificial Membrane Permeability Assay over Franz Cell Apparatus Using BCS Model Drugs. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, J.E.; Kim, S.; Kim, B.H. In vitro skin absorption tests of three types of parabens using a Franz diffusion cell. J. Expo. Sci. Environ. Epidemiol. 2017, 27, 320–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartos, C.; Szabó-Révész, P.; Horváth, T.; Varga, P.; Ambrus, R. Comparison of Modern In Vitro Permeability Methods with the Aim of Investigation Nasal Dosage Forms. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-Campos, F.; Clares, B.; Rodríguez-Lagunas, M.J.; Jauregui, O.; Casals, I.; Calpena, A.C. Ex-Vivo and In-Vivo Assessment of Cyclamen europaeum Extract After Nasal Administration. Pharmaceutics 2019, 11, 426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toffoletto, N.; Chauhan, A.; Alvarez-Lorenzo, C.; Saramago, B.; Serro, A.P. Asymmetry in Drug Permeability through the Cornea. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lancina III, M.G.; Shankar, R.K.; Yang, H. Chitosan Nanofibers for Transbuccal Insulin Delivery. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2017, 105, 1252–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, R.S.; Billa, N.; Morris, A.P. Optimizing In Vitro Skin Permeation Studies to Obtain Meaningful Data in Topical and Transdermal Drug Delivery. AAPS PharmSciTech 2025, 26, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borbás, E.; Balogh, A.; Bocz, K.; Müller, J.; Kiserdei, É.; Vigh, T.; Sinkó, B.; Marosi, A.; Halász, A.; Dohányos, Z.; et al. In vitro dissolution-permeation evaluation of an electrospun cyclodextrin-based formulation of aripiprazole using μFlux™. Int. J. Pharm. 2015, 491, 180–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Introduction to NaviCyte Warner Instruments. Available online: https://www.warneronline.com/introduction-to-navicyte (accessed on 14 September 2025).

- García, J.; Méndez, D.; Álvarez, M.; Sanmartin, B.; Vázquez, R.; Regueiro, L.; Atanassova, M. Design of novel functional food products enriched with bioactive extracts from holothurians for meeting the nutritional needs of the elderly. LWT 2019, 109, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramsay, E.; Del Amo, E.M.; Toropainen, E.; Tengvall-Unadike, U.; Ranta, V.P.; Urtti, A.; Ruponen, M. Corneal and conjunctival drug permeability: Systematic comparison and pharmacokinetic impact in the eye. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2018, 119, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bejgum, B.C.; Donovan, M.D. Uptake and Transport of Ultrafine Nanoparticles (Quantum Dots) in the Nasal Mucosa. Mol. Pharm. 2021, 18, 429–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Córdoba-Díaz, M.; Nova, M.; Elorza, B.; Córdoba-Díaz, D.; Chantres, J.R.; Córdoba-Borrego, M. Validation protocol of an automated in-line flow-through diffusion equipment for in vitro permeation studies. J. Control. Release 2000, 69, 357–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cordoba Díaz, D.; Losa Iglesias, M.E.; Becerro de Bengoa Vallejo, R.; Cordoba Diaz, M. Transungual Delivery of Ciclopirox Is Increased 3–4-Fold by Mechanical Fenestration of Human Nail Plate in an In Vitro Model. Pharmaceutics 2019, 11, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, J.; Fang, X.; Li, X. Transbuccal delivery of 2′,3′-dideoxycytidine: In vitro permeation study and histological investigation. Int. J. Pharm. 2002, 231, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, Y.; Singh, A.K.; Mishra, S.; Gurule, S.J.; Khuroo, A.H.; Tiwari, N.; Bedi, S. Comparison of In Vitro Release Rates of Diclofenac Topical Formulations Using an In-Line Cell Automated Diffusion System. Dissolution Technol. 2019, 26, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Medicines Agency: EMA/CHMP/QWP/708282/2018. Draft Guideline on Quality and Equivalence of Topical Products; European Medicines Agency: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration (US FDA). In Vitro Release Test Studies for Topical Drug Products Submitted in ANDAs. Guidance for Industry. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/media/162476/download (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- Avdeef, A. Absorption and Drug Development: Solubility, Permeability, and Charge State, 1st ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2003; ISBN 9780471423652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avdeef, A.; Bendels, S.; Di, L.; Faller, B.; Kansy, M.; Sugano, K.; Yamauchi, Y. PAMPA—Critical factors for better predictions of absorption. J. Pharm. Sci. 2007, 96, 2893–2909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avdeef, A.; Tsinman, O. PAMPA—A drug absorption in vitro model 13. Chemical selectivity due to membrane hydrogen bonding: In combo comparisons of HDM-, DOPC-, and DS-PAMPA models. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2006, 28, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsinman, O.; Tsinman, K.; Sun, N.; Avdeef, A. Physicochemical Selectivity of the BBB Microenvironment Governing Passive Diffusion—Matching with a Porcine Brain Lipid Extract Artificial Membrane Permeability Model. Pharm. Res. 2011, 28, 337–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, C.T.; Lee, M.H.; Weng, C.F.; Leong, M.K. In Silico Prediction of PAMPA Effective Permeability Using a Two-QSAR Approach. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balázs, B.; Vizserálek, G.; Berkó, S.; Budai-Szűcs, M.; Kelemen, A.; Sinkó, B.; Takács-Novák, K.; Szabó-Révész, P.; Csányi, E. Investigation of the Efficacy of Transdermal Penetration Enhancers Through the Use of Human Skin and a Skin Mimic Artificial Membrane. J. Pharm. Sci. 2016, 105, 1134–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vizserálek, G.; Balogh, T.; Takács-Novák, K.; Sinkó, B. PAMPA study of the temperature effect on permeability. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2014, 53, 45–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vizserálek, G.; Berkó, S.; Tóth, G.; Balogh, R.; Budai-Szűcs, M.; Csányi, E.; Sinkó, B.; Takács-Novák, K. Permeability test for transdermal and local therapeutic patches using Skin PAMPA method. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2015, 76, 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geinoz, S.; Guy, R.H.; Testa, B.; Carrupt, P.A. Quantitative structure-permeation relationships (QSPeRs) to predict skin permeation: A critical evaluation. Pharm. Res. 2004, 21, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, L.; Patel, A.; Sinko, B.; Bell, M.; Wibawa, J.; Hadgraft, J.; Lane, M.E. A comparative study of the in vitro permeation of ibuprofen in mammalian skin, the PAMPA model and silicone membrane. Int. J. Pharm. 2016, 505, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Csizmazia, E.; Erős, G.; Berkesi, O.; Berkó, S.; Szabó-Révész, P.; Csányi, E. Pénétration enhancer effect of sucrose laurate and Transcutol on ibuprofen. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2011, 21, 411–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Lane, M.E.; Hadgraft, J.; Heinrich, M.; Chen, T.; Lian, G.; Sinko, B. A comparison of the in vitro permeation of niacinamide in mammalian skin and in the Parallel Artificial Membrane Permeation Assay (PAMPA) model. Int. J. Pharm. 2019, 556, 142–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köllmer, M.; Mossahebi, P.; Sacharow, E.; Gorissen, S.; Gräfe, N.; Evers, D.H.; Herbig, M.E. Investigation of the Compatibility of the Skin PAMPA Model with Topical Formulation and Acceptor Media Additives Using Different Assay Setups. AAPS PharmSciTech 2019, 20, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Escobar-Chávez, J.J.; Merino-Sanjuán, V.; López-Cervantes, M.; Urban-Morlan, Z.; Piñón-Segundo, E.; Quintanar-Guerrero, D.; Ganem-Quintanar, A. The Tape-Stripping Technique as a Method for Drug Quantification in Skin. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 2008, 11, 104–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramadon, D.; McCrudden, M.T.C.; Courtenay, A.J.; Donnelly, R.F. Enhancement strategies for transdermal drug delivery systems: Current trends and applications. Drug Deliv. Transl. Res. 2022, 12, 758–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pailler-Mattei, C.; Guerret-Piécourt, C.; Zahouani, H.; Nicoli, S. Interpretation of the human skin biotribological behaviour after tape stripping. J. R. Soc. Interface 2011, 8, 934–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lademann, J.; Jacobi, U.; Surber, C.; Weigmann, H.J.; Fluhr, J.W. The tape stripping procedure—Evaluation of some critical parameters. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2009, 72, 317–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volz, P.; Boreham, A.; Wolf, A.; Kim, T.Y.; Balke, J.; Frombach, J.; Hadam, S.; Afraz, Z.; Rancan, F.; Blume-Peytavi, U.; et al. Application of single molecule fluorescence microscopy to characterize the penetration of a large amphiphilic molecule in the stratum corneum of human skin. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 16, 6960–6977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- König, K.; Ehlers, A.; Stracke, F.; Riemann, I. In vivo Drug Screening in Human Skin Using Femtosecond Laser Multiphoton Tomography. Skin Pharmacol. Physiol. 2006, 19, 78–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashtikar, M.; Matthäus, C.; Schmitt, M.; Krafft, C.; Fahr, A.; Popp, J. Non-invasive depth profile imaging of the stratum corneum using confocal Raman microscopy: First insights into the method. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2013, 50, 601–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caspers, P.J.; Lucassen, G.W.; Carter, E.A.; Bruining, H.A.; Puppels, G.J. In vivo confocal Raman microspectroscopy of the skin: Noninvasive determination of molecular concentration profiles. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2001, 116, 434–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, K.W.; Young, P.A. Principles of multiphoton microscopy. Nephron Exp. Nephrol. 2006, 103, e33–e40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imanishi, Y.; Lodowski, K.H.; Koutalos, Y. Two-photon microscopy: Shedding light on the chemistry of vision. Biochemistry 2007, 46, 9674–9684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verma, D.D.; Verma, S.; Blume, G.; Fahr, A. Liposomes increase skin penetration of entrapped and non-entrapped hydrophilic substances into human skin: A skin penetration and confocal laser scanning microscopy study. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2003, 55, 271–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alvarez-Román, R.; Naik, A.; Kalia, Y.N.; Fessi, H.; Guy, R.H. Visualization of skin penetration using confocal laser scanning microscopy. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2004, 58, 301–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vardaxis, N.J.; Brans, T.A.; Boon, M.E.; Kreis, R.W.; Marres, L.M. Confocal laser scanning microscopy of porcine skin: Implications for human wound healing studies. J. Anat. 1997, 190, 601–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Ji, C.; Miao, M.; Yang, K.; Luo, Y.; Hoptroff, M.; Collins, L.Z.; Janssen, H.G. Ex-vivo measurement of scalp follicular infundibulum delivery of zinc pyrithione and climbazole from an anti-dandruff shampoo. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2017, 143, 26–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Binder, L.; SheikhRezaei, S.; Baierl, A.; Gruber, L.; Wolzt, M.; Valenta, C. Confocal Raman spectroscopy: In vivo measurement of physiological skin parameters—A pilot study. J. Dermatol. Sci. 2017, 88, 280–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakagawa, N.; Matsumoto, M.; Sakai, S. In vivo measurement of the water content in the dermis by confocal Raman spectroscopy. Skin Res. Technol. 2010, 16, 137–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sigurdsson, S.; Philipsen, P.A.; Hansen, L.K.; Larsen, J.; Gniadecka, M.; Wulf, H.C. Detection of skin cancer by classification of Raman spectra. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2004, 51, 1784–1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakonyi, M.; Gácsi, A.; Kovács, A.; Szűcs, M.B.; Berkó, S.; Csányi, E. Following-up skin penetration of lidocaine from different vehicles by Raman spectroscopic mapping. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2018, 154, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkó, S.; Zsikó, S.; Deák, G.; Gácsi, A.; Kovács, A.; Budai-Szűcs, M.; Pajor, L.; Bajory, Z.; Csányi, E. Papaverine hydrochloride containing nanostructured lyotropic liquid crystal formulation as a potential drug delivery system for the treatment of erectile dysfunction. Drug Des. Devel. Ther. 2018, 12, 2923–2931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ilchenko, O.; Pilgun, Y.; Makhnii, T.; Slipets, R.; Reynt, A.; Kutsyk, A.; Slobodianiuk, D.; Koliada, A.; Krasnenkov, D.; Kukharskyy, V. High-speed line-focus Raman microscopy with spectral decomposition of mouse skin. Vib. Spectrosc. 2016, 83, 180–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyatski, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Mendelsohn, R.; Flach, C.R. Effects of permeation enhancers on flufenamic acid delivery in Ex vivo human skin by confocal Raman microscopy. Int. J. Pharm. 2016, 505, 319–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos, L.; Téllez S, C.A.; Sousa, M.P.J.; Azoia, N.G.; Cavaco-Paulo, A.M.; Martin, A.A.; Favero, P.P. In vivo confocal Raman spectroscopy and molecular dynamics analysis of penetration of retinyl acetate into stratum corneum. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2017, 174, 279–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, G.P.S.; McGoverin, C.M.; Fraser, S.J.; Gordon, K.C. Raman imaging of drug delivery systems. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2015, 89, 21–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franzen, L.; Windbergs, M. Applications of Raman spectroscopy in skin research—From skin physiology and diagnosis up to risk assessment and dermal drug delivery. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2015, 89, 91–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wartewig, S.; Beubert, R.H.H. Pharmaceutical applications of Mid-IR and Raman spectroscopy. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2005, 57, 1144–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Haaren, C.; De Bock, M.; Kazarian, S.G. Advances in ATR-FTIR Spectroscopic Imaging for the Analysis of Tablet Dissolution and Drug Release. Molecules 2023, 28, 4705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arndt, N.; Bolwien, C.; Sulz, G.; Kühnemann, F.; Lambrecht, A. Diamond-Coated Silicon ATR Elements for Process Analytics. Sensors 2021, 21, 6442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Kelani, M.; Buthelezi, N. Advancements in medical research: Exploring Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy for tissue, cell, and hair sample analysis. Skin Res. Technol. 2024, 30, e13733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baij, L.; Hermanus, J.J.; Keune, K.; Iedema, P.D. Time-Dependent ATR-FTIR Spectroscopic Studies on Solvent Diffusion and Film Swelling in Oil Paint Model Systems. Macromolecules 2018, 51, 7134–7144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wynne, A.C.; Abbott, B.S.; Niazi, R.; Foley, K.; Walters, K.B. Experimental and modeling approaches to determine drug diffusion coefficients in artificial mucus. Heliyon 2024, 10, e38638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Carro, E.; Angenent, M.; Gracia-Cazaña, T.; Gilaberte, Y.; Alcaine, C.; Ciriza, J. Modeling an Optimal 3D Skin-on-Chip within Microfluidic Devices for Pharmacological Studies. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohamadali, M.; Ghiaseddin, A.; Irani, S.; Amirkhani, M.A.; Dahmardehei, M. Design and evaluation of a skin-on-a-chip pumpless microfluidic device. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 8861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sutterby, E.; Thurgood, P.; Baratchi, S.; Khoshmanesh, K.; Pirogova, E. Microfluidic Skin-on-a-Chip Models: Toward Biomimetic Artificial Skin. Small 2020, 16, e2002515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhee, S.; Xia, C.; Chandra, A.; Hamon, M.; Lee, G.; Yang, C.; Guo, Z.; Sun, B. Full-Thickness Perfused Skin-on-a-Chip with In Vivo-Like Drug Response for Drug and Cosmetics Testing. Bioengineering 2024, 11, 1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, S.W.; Malick, H.; Kim, S.J.; Grattoni, A. Advances in skin-on-a-chip technologies for dermatological disease modeling. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2024, 144, 1707–1715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, S.; Vilas-Boas, V.; Lebre, F.; Granjeiro, J.M.; Catarino, C.M.; Moreira Teixeira, L.; Loskill, P.; Alfaro-Moreno, E.; Ribeiro, A.R. Microfluidic-based skin-on-chip systems for safety assessment of nanomaterials. Trends Biotechnol. 2023, 41, 1282–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoio, P.; Oliva, A. Skin-on-a-Chip Technology: Microengineering Physiologically Relevant In Vitro Skin Models. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, M.S.; Jang, J.; Jo, H.J.; Kim, W.H.; Kim, B.; Chun, H.J.; Lim, D.; Han, D.W. Advances and Innovations of 3D Bioprinting Skin. Biomolecules 2022, 13, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Zhang, C.; Li, Z.; Fu, X.; Huang, S. Advances in 3D skin bioprinting for wound healing and disease modeling. Regen. Biomater. 2022, 10, rbac105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Derman, I.D.; Rivera, T.; Garriga Cerda, L.; Singh, Y.P.; Saini, S.; Abaci, H.E.; Ozbolat, I.T. Advancements in 3D skin bioprinting: Processes, bioinks, applications and sensor integration. Int. J. Extrem. Manuf. 2025, 7, 012009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros, N.R.; Kang, R.; Kim, J.; Ermis, M.; Kim, H.J.; Dokmeci, M.R.; Lee, J. A human skin-on-a-chip platform for microneedling-driven skin cancer treatment. Mater. Today Bio 2024, 30, 101399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Species | Anatomic Region | Stratum Corneum (µm) | Epidermis (µm) | Whole Skin (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human | Forearm | 17 | 36 | 1.5 |

| Human | Abdomen | 6.9–9.8 | 64.7–95.5 | 1.5–3 |

| Monkey | Abdomen | 5.33 ± 0.40 | 17.14 ± 2.22 | 1.5 ± 0.7 |

| Mouse | Dorsal | 5 | 13 | 0.8 |

| Porcine | Ear | 10 | 50 | 1.3 |

| Porcine | Dorsal | 26 | 66 | 3.4 |

| Rabbit | Ear | 11.7 ± 0.5 | 17 ± 1.2 | 0.2764 ± 0.01 |

| Rat | Dorsal | 18 | 32 | 2.09 |

| Snake | Shed (cornified layer) | 10–20 | N/A | N/A |

| Product | Manufacturer |

|---|---|

| RHE | |

| EpiCS® | CellSystems, Troisdorf, Germany (HENKEL), Phenion |

| EpiDerm™ | MatTek Corporation, Ashland, MA, USA |

| EpiSkin™ RHE | EpiSkin, L’Oréal Research and Innovation, Lyon, France |

| LabCyte EPI-MODEL 12 | Japan Tissue Engineering Co. Ltd., Gamagori, Japan |

| LabCyte EPI-MODEL 24 | Japan Tissue Engineering Co. Ltd., Gamagori, Japan |

| SkinEthic™ RHE | EpiSkin, L’Oréal Research and Innovation, Lyon, France |

| SkinEthic™ RHPE | EpiSkin, L’Oréal Research and Innovation, Lyon, France |

| Straticell RHE | StratiCELL, Les Isnes, Belgium |

| Straticell RHE-MEL | StratiCELL, Les Isnes, Belgium |

| FTSE | |

| EpiDerm-FT™ | MatTek Corporation, Ashland, MA, USA |

| Apligraf® | Organogenesis Inc., Canton, MA, USA |

| Phenion® FT Skin Model | Phenion, Düsseldorf, Germany |

| Phenion® FT AGED | Phenion, Düsseldorf, Germany |

| Phenion® FT LONG-LIFE | Phenion, Düsseldorf, Germany |

| StrataGraft® | Mallinckrodt Pharmaceuticals, Madison, WI, USA |

| Method | Benefits | Drawbacks |

|---|---|---|

| Franz cell |

|

|

| Skin-PAMPA |

|

|

| Tape stripping |

|

|

| Microscopy and spectroscopy |

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bouwer, F.; Brits, M.; Viljoen, J.M. Cracking the Skin Barrier: Models and Methods Driving Dermal Drug Delivery. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 1586. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics17121586

Bouwer F, Brits M, Viljoen JM. Cracking the Skin Barrier: Models and Methods Driving Dermal Drug Delivery. Pharmaceutics. 2025; 17(12):1586. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics17121586

Chicago/Turabian StyleBouwer, Francelle, Marius Brits, and Joe M. Viljoen. 2025. "Cracking the Skin Barrier: Models and Methods Driving Dermal Drug Delivery" Pharmaceutics 17, no. 12: 1586. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics17121586

APA StyleBouwer, F., Brits, M., & Viljoen, J. M. (2025). Cracking the Skin Barrier: Models and Methods Driving Dermal Drug Delivery. Pharmaceutics, 17(12), 1586. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics17121586