Abstract

Large-scale cultural events generate substantial greenhouse gas emissions, raising increasing concerns regarding carbon neutrality. In Taiwan, long-standing forest conservation policies have largely restricted commercial logging since the early 1990s, resulting in extensive secondary forests where active management options are limited. Within this policy context, improved forest management (IFM) provides a potential pathway to enhance carbon sequestration while maintaining conservation objectives. This study evaluates the feasibility of using afforestation combined with IFM to offset the carbon emissions of the Taipei Biennial 2020, estimated at approximately 390 t CO2-e. Carbon sequestration was assessed using the Verified Carbon Standard (VCS) methodology (VM0005 v1.2) under the principles of Measurement, Reporting, and Verification (MRV). A total area of 52.70 ha was assessed, with 10.11 ha designated as the project activity area. Over a 25-year period, projected CO2 sequestration across four baseline scenarios ranged from 3816 to 4523 tons, indicating that event-related emissions could be offset within 8–9 years. Uncertainty remains due to hypothetical management assumptions, highlighting the need for continuous monitoring and adaptive management.

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

Large-scale cultural events have increasingly been scrutinized for their environmental impacts, particularly greenhouse gas emissions associated with venue operation, transportation, and exhibition production [1,2,3]. In recent years, achieving carbon neutrality has become an important objective in the planning and implementation of major exhibitions and public-sector events. Carbon neutrality generally refers to achieving a balance between carbon emissions and carbon reductions or removals within a defined period, typically through a combination of emission reduction measures and carbon offset mechanisms [2,4].

Based on an internal carbon footprint assessment conducted as part of a separate research project commissioned by the Taipei Biennial organizers, total greenhouse gas emissions associated with the Taipei Biennial 2020 were estimated at approximately 390 t CO2-e., including emissions from exhibition hall operations, personnel transportation, and the production and transportation of artworks. As this assessment was conducted for internal planning purposes, the detailed inventory report is not publicly available. Although conventional mitigation strategies—such as energy conservation, efficiency improvements, and the substitution of fossil fuels with low-carbon energy sources—can reduce emissions, they are often insufficient to fully offset emissions associated with large-scale cultural events. As a result, nature-based solutions, particularly forest-based carbon sequestration, have been increasingly considered as complementary carbon offset approaches [5,6].

Afforestation and forest regeneration contribute to carbon sequestration through biomass accumulation and ecosystem productivity, especially in young or secondary forests where growth rates typically exceed mortality rates [4,7,8,9]. However, carbon sequestration capacity is strongly influenced by forest structure, stand density, and management practices. As secondary forests mature, growth rates may decline, and carbon uptake efficiency can decrease, highlighting the importance of active but ecologically compatible forest management to sustain long-term carbon sequestration [10,11].

In Taiwan, forest management practices have been strongly shaped by long-standing forest conservation policies [12]. Since the early 1990s, commercial logging in natural forests has been largely prohibited, with strict restrictions also applied to secondary forests. These policies were implemented in response to widespread concerns over deforestation, landslides, and ecosystem degradation, and they have played a critical role in preventing large-scale forest loss. Similar conservation-oriented policy trajectories have been observed in other regions where forest protection has been prioritized over timber production.

However, international experience has shown that prolonged restrictions on active forest management can also lead to extensive areas of overstocked secondary forests with limited structural diversity and constrained natural regeneration [3]. High stand density and insufficient structural differentiation may reduce forest vitality, increase susceptibility to disturbances, and limit long-term carbon sequestration efficiency. Within such policy contexts, forest management approaches relying on clear-cutting or large-scale forest conversion are neither socially acceptable nor institutionally feasible.

Consequently, improved forest management (IFM), emphasizing selective thinning, structural enhancement, and the development of multi-storied forest stands, has emerged as a pragmatic pathway to reconcile forest conservation objectives with carbon sequestration and broader ecosystem service goals [13,14]. IFM allows incremental improvements in forest structure and carbon uptake while remaining consistent with strict forest conservation frameworks and social expectations [15,16].

Within this policy and ecological context, a public woodland located in the Cuishan section of Shilin District, Taipei City, Taiwan, was selected as the study site. The area is primarily composed of secondary forest and is managed using environmentally friendly practices that avoid heavy machinery and rely largely on manual operations. From the total woodland area of 52.70 ha, a 10.11 ha management unit was designated as the project activity area. Afforestation and forest structure enhancement were planned using native tree species, integrating newly planted trees, retained canopy trees, and future understory vegetation to improve carbon sequestration potential while maintaining ecological integrity.

Despite growing interest in forest-based carbon offset strategies, empirical research examining the application of IFM in small-scale urban or peri-urban secondary forests as a carbon offset mechanism for cultural events remains limited [17]. In particular, the integration of afforestation planning, forest management practices, and standardized carbon accounting methodologies within a strict forest conservation policy context has been insufficiently explored.

1.2. Objective

This study applies afforestation-based carbon reduction practices in combination with improved forest management to evaluate their feasibility as a carbon offset mechanism for a large-scale cultural exhibition. By integrating forest management planning with an internationally recognized carbon accounting framework, this research aims to assess whether event-related carbon emissions can be offset within the constraints of long-standing forest conservation policies.

The specific objectives of this study are as follows:

- To apply an improved forest management (IFM) approach to a small-scale public woodland, emphasizing sustainable management principles and compatibility with strict forest conservation policies.

- To develop a multi-storied forest structure through afforestation and structural enhancement and to quantitatively assess forest carbon sequestration outcomes under different baseline scenarios.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Target Area

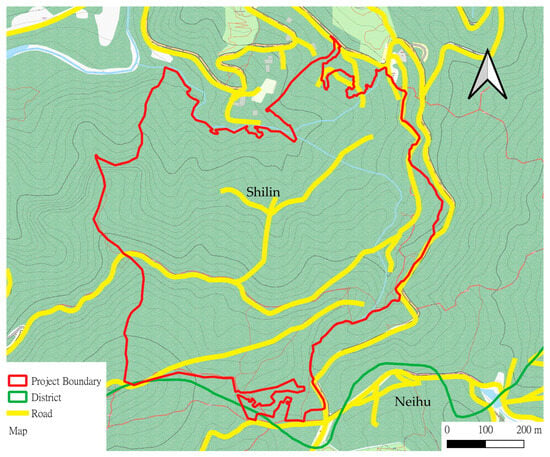

The target area is public land located at No. 81, a subsection of the Cuishan Section, Shilin District, Taipei City, with a total area of 52.70 ha (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The planned implementation site and the surrounding traffic conditions.

Three hiking trails are present within the target area, including the Bao Dalun Touwei Mountain Trail, Cuishan Trail, and Bixi Trail. These trails are primarily composed of gravel surfaces and wooden planks and have gentle slopes. Due to their proximity to major roads and recreational areas, the site has relatively high accessibility and visitor frequency. Basic recreational facilities, such as observation and lookout decks, are distributed along the trails.

2.2. Climate

The target area is located in Shilin District, Taipei City, and has a subtropical climate. The average annual temperature is approximately 23.4 °C, and the average annual precipitation is about 3186.5 mm. The perhumid period generally extends from March to December, while January and February constitute a relatively drier period.

2.3. Woodland Utilization

Woodland conditions in the target area were evaluated using the most recent aerial photographs. The area was originally developed for afforestation and agricultural use and has gradually evolved into a broad-leaved secondary forest. It is classified as non-protected forest land, with slopes below 35° and tree canopy coverage exceeding 70%.

As an early successional forest, the estimated stand density of trees with diameters greater than 5 cm was approximately 1660 stems/ha. Dominant species included Diospyros morrisiana, Ardisia quinquegona, Randia canthioides, and Schefflera octophylla, which were relatively evenly distributed across the plot. Due to high stand density, many trees exhibited slender and elongated growth forms. More than 50% of sampled trees had diameters between 5 and 15 cm, while approximately one-sixth of individuals had a diameter at breast height (DBH) below 5 cm.

High stand density and limited understory development suggest constrained air circulation and reduced groundcover regeneration. These structural characteristics were considered in subsequent analyses of forest management potential and carbon sequestration capacity.

2.4. Data

This study adopted a scenario-based forest management framework to evaluate the potential effects of small-scale selective thinning and afforestation on forest structure and carbon sequestration. The proposed management approach involves selectively removing poorly formed and poorly growing trees in an environmentally friendly manner, followed by afforestation and tending using native tree species, including Calocedrus formosana, Liquidambar formosana, and Acacia confusa, to facilitate the development of a multi-storied forest. When seedling availability was insufficient, additional native species suitable for site conditions were considered. We used Microsoft Excel to calculate the results and produced figures in this study.

The primary components of this study included forest management planning, resource analysis and field investigation of the target area, development planning for a multi-storied forest structure, and scenario-based estimation of carbon sequestration outcomes and monitoring requirements.

2.4.1. Planning Forest Management and Resource Analysis and Investigation in the Target Area

Basic environmental and forest resource data for the target area were analyzed to support forest management planning and to inform subsequent scenario-based evaluations.

Management Planning in the Target Area

Forest management planning aimed to enhance carbon sequestration potential while maintaining consistency with site conditions and environmental constraints. Areas with slopes exceeding 35° were designated as reserved areas, and buffer zones of 20 m were established along streams and trails. Proposed selective thinning activities were designed to be adjusted according to site-specific conditions.

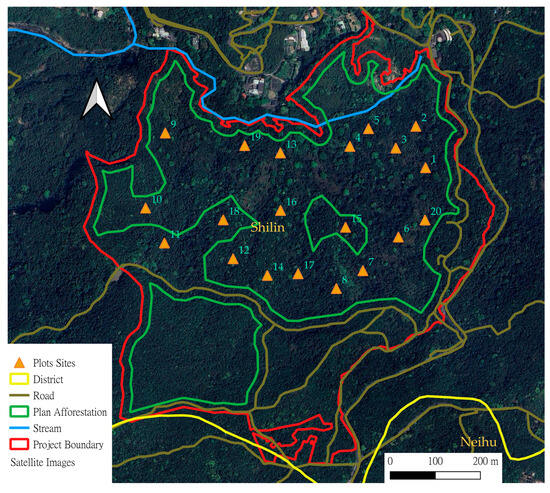

Investigation of the Target Area Forest Resource Situation

Representative locations within the target area were selected based on topography, slope, and aspect. A total of approximately 10 ha was designated for potential selective thinning and afforestation activities using a small-scale block approach. Temporary sample plots covering 10% of the afforested area were established, with each plot measuring 0.05 ha, resulting in 20 plots and a total sampled area of 1 ha. Survey variables included tree species, diameter at breast height (DBH), and tree height. These data were used to characterize forest structure and species composition for management planning purposes.

2.4.2. Planning and Development of the Multi-Storied Forest

Planning for the development of a multi-storied forest in the afforested area was based on the principle of enhancing carbon sequestration while maintaining ecological integrity. Forest stand density was reduced through selective thinning (also referred to as improvement cutting) rather than clear-cutting. This approach targeted suppressed, poorly formed, or low-vigor individuals to improve stand structure, light availability, and long-term forest growth, while retaining healthy trees and existing canopy cover. Selective thinning is a commonly applied silvicultural practice in secondary forest management and is consistent with the objective of enhancing carbon sequestration without compromising ecological functions [18].

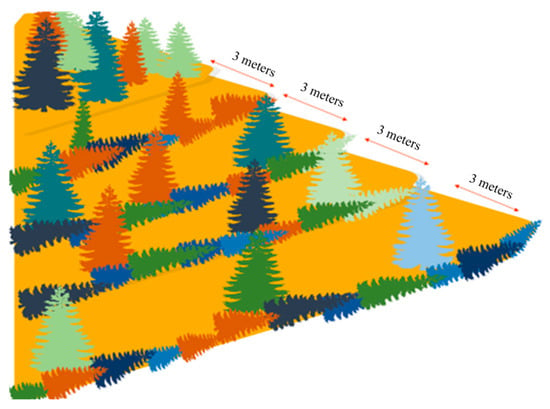

The development of the multi-storied forest was implemented in small-scale blocks to minimize disturbance to soil and residual vegetation. Trees selected for removal were primarily small-diameter, suppressed, or poorly formed individuals, whereas future crop trees were retained. Felled trees were cut into sections (approximately 1.0–1.5 m) and stacked along retention strips following contour lines to enhance soil and water conservation. Soil preparation and planting layouts were adjusted on-site based on slope, rock exposure, and existing vegetation conditions.

Planning of Multi-Storied Forest Development

The analysis of basic data was used to develop the multi-storied forest planned for the target area, and the location of the actual construction area was determined by a site survey.

Selective Thinning and Soil Preparation

Within the proposed management framework, poorly formed or damaged trees were designated for removal, while trees with favorable growth potential were retained. Felled trees were processed into 1.0–1.5 m sections and stacked along retention strips to support soil and water conservation. Soil preparation and planting layout followed contour lines to reduce erosion risk.

Afforestation Operation

Suitable tree species were selected that were consistent with the management goals of the woodland and its environmental conditions, and the afforestation was conducted using the principle of suitable species.

Management

The management primarily included mowing, removing vines, and pruning. The new planting procedure was to mow the grass every year for 1–6 years after the new planting. However, because the affected area is in the north, and the northern area is prone to weeds owing to abundant rainfall, the frequency of mowing was increased depending on the conditions, and the plants were pruned in a timely manner within the 6-year tendering period.

2.4.3. Estimation of Carbon Sequestration and Monitoring of the Planning

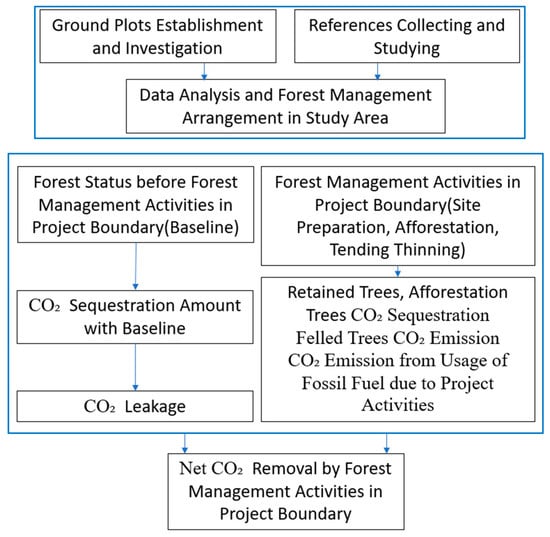

Carbon emissions associated with the Taipei Biennial 2020 were estimated at approximately 390 t CO2-e. Scenario-based carbon sequestration estimates were conducted using methodologies from the Verified Carbon Standard (VCS), including afforestation/reforestation (AR) and improved forest management (IFM) frameworks. In particular, VM0005 was adopted as the primary methodological reference for evaluating the conversion of low-yield forests to higher-yield conditions, with additional consideration of extended rotation principles where applicable [19]. Carbon accounting followed the principles of Measurement, Reporting, and Verification (MRV). The analytical workflow of the study is summarized in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

The operation process of CO2 removal calculation.

Baseline Calculation

Due to the absence of long-term site-specific growth records, baseline growth rates were not treated as a single deterministic value but were instead represented using a scenario-based framework derived from published growth ranges for secondary forests [6]. The baseline calculation estimates the net baseline carbon emissions and carbon removal based on the ground plot survey data before the project was initiated. The parameters of this method include the aboveground biomass, belowground biomass, and dead wood.

To comply with the operational method of this study, 10.11 ha out of the total area of 52.70 ha was used as the baseline area. Since the target area had no long-term growth monitoring data in the past, the re-examination plan and previous report of the Fushan Forest Dynamic Plot (Forestry Agency, Taiwan), which were close to the geographical location and forest ratio, were used. The methods of [20] were used as proxy data to estimate the baseline CO2 net removal under assumed baseline scenarios for this study (Equation (1)):

where is the net CO2 removal under the baseline scenario in year t (t CO2-e yr−1); is the change in above- and belowground tree biomass carbon stock under the baseline scenario in year t (t CO2-e yr−1); is the greenhouse gas emissions within the project boundary under the baseline scenario in year t (t CO2-e yr−1).

ΔCBSL,t = ΔCBSL,tree,t − GHGBSL−E,t

Project Calculations

Greenhouse gas emissions from project activities were estimated based on recorded fossil fuel consumption associated with forest management operations. These activities primarily involved the use of chainsaws and brush cutters during selective thinning, soil preparation, and planting operations. Fuel consumption was recorded on a per-hectare basis and converted to CO2 emissions using a standard emission factor of 2.26 kg CO2 per liter of gasoline. No heavy machinery was used, as all operations were conducted manually to minimize environmental disturbance.

The project calculations were conducted under assumed IFM implementation scenarios within the defined project boundary, including the aboveground and underground biomass of the trees affected, carbon changes in the fallen trees after they had been removed, and carbon emissions caused by the implementation of project activities.

∆CBSL in Equation (1) is calculated, and the formula is as follows (Equation (2)):

where is the annual change in tree carbon stock under the baseline scenario in year t (t CO2-e yr−1); and represent the carbon stock of above- and belowground tree biomass in years t and t − 1, respectively (t CO2-e).

ΔCBSL,tree,t = CBSL,tree,t − CBSL,tree,t−1

The calculation of C(BSL,tree,t) is divided into the aboveground and belowground biomass of the tree, and the biomass expansion coefficient method was used to determine the DBH of the tree and its height (H). The trunk volume of a single tree was calculated based on the volume formula (Equation (3)).

V = 0.00008626 × D1.8742 × H0.8671

Next, based on the formula of IPCC specifications to calculate the changes in amounts of carbon, the change in storage of carbon caused by the increase in biomass was estimated based on the growth of the standing forest volume. The biomass conversion and expansion factor (BCEF), shoot ratio (R), and carbon fraction (CF) of the tree species were related, i.e., the “net growth of tree trunk volume” per hectare of standing forest was multiplied by (BCEF × [1 + R] × CF) to calculate its annual change in carbon per hectare. The BCEF can also be obtained by multiplying the base density (D) by the biological expansion factor (BEF) (Equation (4)):

where is the estimated carbon stock (t C); is the stem volume of an individual tree (m3); is the biomass expansion factor; is the basic wood density (t m−3); is the root-to-shoot ratio; is the carbon fraction of dry biomass; and n is the number of trees within the assessment unit.

C = sum_{i=1}^{n} Vi × BEF × D(1 + R) × CF

The amount of carbon sequestration per plant was calculated using Equation (4), and the carbon content was then converted to CO2 equivalents using the CO2 to carbon molecular weight (44/12) ratio, which is C(BSL,tree,t); GHG(BSL-E,t), which were assumed to be negligible under the defined baseline scenarios.

In this study, within the planned area of 52.7 ha, 10.11 ha was established as the project area, and the forest management activities were conducted. The actual net removal of CO2 after the implementation of the project was calculated using Equation (5):

where is the net CO2 removal under the project scenario in year t (t CO2-e yr−1); is the change in carbon stock of retained and newly planted trees in year t (t CO2-e yr−1); represents CO2 emissions from felled biomass due to decay in year t (t CO2-e yr−1); is greenhouse gas emissions from project-related activities in year t (t CO2-e yr−1).

ΔCP,t = ΔCP,tree,t − CCut,tree,t − GHGP,t

In this study, we referred to the data of [21,22] to conduct an annual estimation of the emissions of CO2 from fallen trees. Ref. [21] proposed that the conversion factor of biomass placed in the forest to CO2 emission was 0.485, while [22] studied the rate of CO2 emissions from fallen broad-leaved trees placed in the forest and found that the CO2 emission decreased yearly at a rate of 15% per year.

Leakage

Carbon leakage was assumed to be zero in this study. This assumption is justified because the project did not involve commercial timber harvesting, displacement of timber production, or market-driven land-use change. All felled biomass remained within the project boundary and was not removed for external use. As the management activities were implemented within a publicly owned forest and did not alter surrounding land-use practices, no indirect emissions outside the project boundary were expected.

Here, is the net CO2 removal resulting from IFM activities in year t (t CO2-e yr−1); is the net CO2 removal under the project scenario; is the net CO2 removal under the baseline scenario; and represents carbon leakage outside the project boundary (t CO2-e yr−1).

ΔCFM,t = ΔCP,t − ΔCBSL,t − LK

Monitoring

The monitoring plan must include monitoring changes in carbon storage and carbon emissions under the baseline scenarios, monitoring carbon storage changes and carbon emissions after project activities, and estimating post-event net carbon storage changes and carbon emissions.

3. Results

3.1. Forest Resource Characteristics of the Target Area

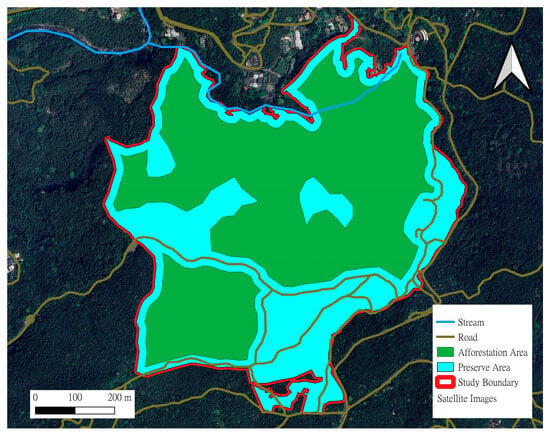

Field observations and plot surveys indicated the presence of several small grassland patches within the target area Figure 3. These patches may be associated with small-scale slope disturbances that occurred prior to the study period. The dominant tree species included tung tree (Vernicia fordii), mountain tallow tree (Triadica cochinchinensis), Myrsine seguinii, Japanese bay tree (Machilus thunbergii), and Schefflera octophylla. Secondary dominant species included rough-leaved holly (Ilex asprella) and Randia canthioides. The shrub layer was primarily composed of Ilex asprella and Schefflera octophylla.

Figure 3.

Forest land use zoning plan in the study area.

Ground vegetation composition varied with canopy closure. In areas with high canopy closure, the tree fern Alsophila podophylla was the dominant understory species, whereas Dicranopteris pedata dominated areas with lower canopy closure.

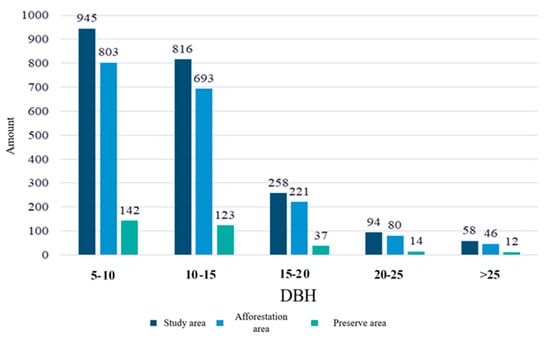

Plot-level analysis indicated that the diameter at breast height (DBH) distribution of the standing forest was dominated by small-diameter trees, primarily within the 5–10 cm class. Only a small proportion of trees exhibited DBH values greater than 25 cm. The mean DBH of the standing forest was estimated at 11.75 ± 6.54 cm, and the mean tree height was approximately 6.54 ± 1.84 m. The estimated standing timber volume was approximately 96.18 m3 ha−1 (Table 1). The forest structure characteristics are further illustrated in Figure 4.

Table 1.

Forest resource plots in the target area.

Figure 4.

Plots in the target area.

Aerial imagery and field surveys conducted in 2019 indicated that the woodland within the target area, which was historically used for afforestation and agriculture, has gradually developed into a broad-leaved secondary forest. The forest is classified as non-protected forest with slopes below 35° and a canopy cover exceeding 70%. Tree density for individuals with DBH > 5 cm was estimated at approximately 1660 stems ha−1. Dominant species included Diospyros morrisiana, Ardisia quinquegona, Randia canthioides, and Schefflera octophylla, which were relatively evenly distributed (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

DBH-level distribution of the target area, to-be-afforested area, and the planned reserve.

The high stand density resulted in slender and tall tree forms. More than 50% of sampled trees had DBH values between 5 and 15 cm, while approximately one-sixth of individuals exhibited DBH values below 5 cm. These stand characteristics were associated with limited air permeability, reduced groundcover regeneration, and comparatively low carbon sequestration potential. Similar structural characteristics were reported in previous ground-based surveys conducted in the Daluntou Mountain area, which documented high stand density (showed in Figure 6) and limited structural differentiation [20,23].

Figure 6.

Woodland situation before the felling operation.

3.2. Implementation Outcomes of Multi-Storied Forest Management

Implementation of multi-storied forest management in the project area was conducted using a small-scale block-based selective thinning approach. Site inspections indicated substantial spatial heterogeneity across the affected area, including the presence of surface stones, creek crossings, and slope stabilization structures. These site constraints limited soil preparation feasibility in certain locations.

Following on-site adjustments, the total target area remained 52.70 ha, while the afforested project area was delineated as 10.11 ha. The resulting thinning intensity was estimated at 16.92%, calculated as the ratio of basal area removed within the afforested area to the total basal area of the target area.

Selective thinning primarily targeted small-diameter broad-leaved secondary forest trees exhibiting poor form or limited growth potential. Felled trees were processed into segments of approximately 1.0–1.5 m in Figure 7 and retained on-site within designated buffer zones to support soil and water conservation. Soil preparation followed contour-based strip planting, with planting belts exceeding 1.5 m in width and inter-row belts maintained below 1.5 m.

Figure 7.

Woodland situation after the felling operation was finished.

Afforestation species were selected based on site suitability and management objectives, with native species such as Calocedrus formosana, Acacia confusa, and Liquidambar formosana prioritized. Planting density within the afforested area was approximately 1000 trees ha−1, excluding retained trees, allowing sufficient growing space for long-term stand development. Species composition and spatial configuration of the afforested area are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Afforestation area, tree species, and quantity.

Post-planting management practices included mowing, vine removal, and pruning during the initial establishment period. As canopy closure progresses, periodic pruning and moderate thinning are expected to facilitate structural adjustment and maintain forest health, particularly in areas managed for recreational and ecological functions.

3.3. Estimated Carbon Sequestration Under Baseline and Project Scenarios

Baseline carbon dynamics were estimated using ground plot survey data collected prior to project implementation, with aboveground biomass, belowground biomass, dead wood, and forest products considered as primary carbon pools. Due to the absence of long-term site-specific growth records, baseline growth rates were represented using a scenario-based framework derived from published growth ranges for secondary broad-leaved forests.

Based on literature and proxy data from regional dynamic plots, four baseline growth scenarios were defined: Scenario A (0.5 m3 ha−1 yr−1), Scenario B (1.0 m3 ha−1 yr−1), Scenario C (2.0 m3 ha−1 yr−1), and Scenario D (2.5 m3 ha−1 yr−1). These scenarios were intended to represent plausible growth ranges rather than deterministic predictions.

Project-related carbon sequestration was estimated by incorporating the growth of retained trees, carbon dynamics of felled biomass, and emissions associated with management activities. Under managed conditions, secondary forest growth was estimated at approximately 3.7 m3 ha−1 yr−1. Given that retained trees represented approximately 49% of the project area, the annual growth of retained trees within the 10.11 ha project area was estimated at approximately 17.96 m3 yr−1 and converted to CO2 equivalents (Table 3).

Table 3.

Growth of the retained trees by project year, carbon storage, and CO2 storage scale.

Carbon emissions from felled trees were estimated based on published decay rates for broad-leaved species. Total CO2 emissions from felled biomass were calculated using a biomass-to-carbon conversion factor of 0.485, with an annual decay-related emission rate of approximately 15%, decreasing over time (Table 4).

Table 4.

Carbon sequestration, carbon storage, and CO2 emission by the fallen trees.

Fossil fuel-related emissions associated with project activities were estimated based on recorded fuel consumption during soil preparation, thinning, planting, and subsequent management operations. Total fuel consumption was estimated at 110 L ha−1 for initial operations and 25 L ha−1 for subsequent mowing activities, with emissions calculated using a conversion factor of 2.26 kg CO2 per liter of fuel.

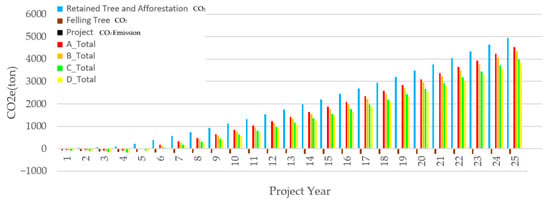

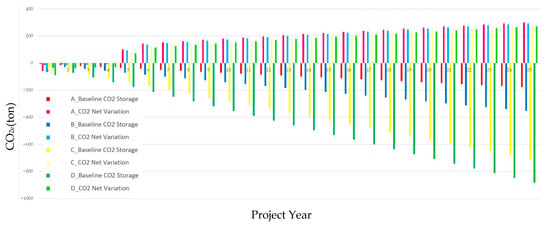

Net CO2 removal under project scenarios was estimated by subtracting baseline carbon dynamics and project-related emissions from total project carbon gains. Modeled results for Scenario A indicated that cumulative CO2 sequestration was estimated to reach approximately 4523.39 t CO2-e by year 25 (Figure 8). Under this scenario, offsetting the CO2 emissions associated with the Taipei Biennial 2020 (approximately 390 t CO2-e) was estimated to occur at approximately year eight.

Figure 8.

Changes in CO2 over 25 years from the project activities with total amount.

Under Scenario B, cumulative CO2 sequestration was estimated at approximately 4346.64 t CO2-e by year 25, with modeled offset occurring at approximately year eight. Scenario C yielded an estimated cumulative sequestration of approximately 3993.15 t CO2-e by year 25, with offset estimated at approximately year nine. Under Scenario D, cumulative sequestration was estimated at approximately 3816.40 t CO2-e by year 25, with offset similarly estimated at approximately year nine.

Across all four scenarios, modeled results suggested that cumulative CO2 sequestration over the 25-year assessment period exceeded 3800 t CO2-e. Under the assumed baseline conditions, exhibition-related carbon emissions were estimated to be potentially offset within approximately nine years(Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Comparison between baseline and project changes in CO2 over 25 years from the project activities.

Uncertainty is inherent in carbon sequestration assessments due to limitations in data availability, model assumptions, and future environmental variability. The use of multiple baseline scenarios in this study was intended to explicitly reflect such uncertainty and provide a bounded range of possible carbon offset trajectories rather than precise predictions. Detailed numerical outputs for all baseline and project scenarios are available in the Supplementary Materials.

4. Discussion

4.1. Interpretation of Forest Management and Carbon Sequestration Outcomes

This study evaluated the potential of improved forest management (IFM) and afforestation in a secondary forest to offset carbon emissions associated with a large-scale cultural event. The results indicate that selective thinning, combined with the establishment of a multi-storied forest structure, can substantially enhance long-term carbon sequestration under a range of baseline growth scenarios. Compared with unmanaged secondary forest conditions, managed stands exhibited higher estimated carbon sequestration potential over the 25-year assessment period.

Forests provide multiple ecosystem services beyond carbon sequestration, including biodiversity conservation, climate regulation, soil and water conservation, and recreational benefits. The concept of forest ecosystem services (FES) emphasizes the multifunctionality of forest systems and the need for management approaches that balance ecological, social, and economic objectives [24,25,26,27,28]. In this context, the IFM approach adopted in this study aligns with multi-objective forest management paradigms by integrating carbon sequestration with ecological conservation and landscape functions.

Differences between project areas (with IFM activities) and non-project areas (without active management) highlight both opportunities and risks associated with forest interventions. While management activities can enhance carbon uptake and structural diversity, they may also introduce ecological trade-offs if not carefully implemented. The scenario-based framework used in this study provides a means to explore these trade-offs while maintaining flexibility under varying baseline assumptions.

4.2. Carbon Neutralization Through Afforestation: Comparison with Previous Studies

Carbon neutralization aims to balance anthropogenic carbon emissions through reductions or removals, including carbon storage in forest ecosystems. Forest carbon pools encompass aboveground and belowground biomass, litter, dead wood, and soil organic matter [8,29]. A growing body of literature has demonstrated the role of forest management in climate change mitigation through carbon conservation, sequestration, and substitution strategies [3,24,28].

Meta-analyses and life-cycle assessments have shown that managed and planted forests generally exhibit higher long-term carbon sequestration potential than unmanaged secondary forests, particularly when harvested wood products and biomass substitution effects are considered [6,15,16]. For example, planted forests have been reported to sequester substantially greater amounts of CO2 over multi-decadal timeframes compared with semi-natural secondary forests, due to enhanced growth rates and active management interventions [9].

The results of this study are consistent with these findings, indicating that afforestation and IFM practices in secondary forests can significantly increase carbon sequestration relative to baseline conditions. However, unlike purely production-oriented plantations, the multi-storied forest approach adopted here emphasizes ecological structure, species diversity, and landscape compatibility, thereby balancing carbon objectives with broader ecosystem services.

4.3. Species Selection and Site Suitability Considerations

Although Calocedrus formosana is typically distributed at elevations between approximately 300 and 1900 m in Taiwan, its use in this study at a lower-altitude site reflects a management decision balancing site suitability, species adaptability, and long-term forest structure. In northern Taiwan, Calocedrus formosana has been observed at relatively lower elevations due to local climatic conditions and historical planting practices. In this study, the species was introduced in limited proportions and integrated within a mixed-species, multi-storied forest design rather than as a monoculture.

This approach aims to enhance vertical structure and long-term carbon sequestration potential while minimizing ecological trade-offs associated with species–site mismatch. By combining Calocedrus formosana with native broad-leaved species in a secondary forest context, the management strategy prioritizes structural diversity, ecosystem resilience, and adaptive capacity over short-term productivity.

4.4. Uncertainty, Monitoring, and Robustness of Carbon Sequestration Estimates

Monitoring is proposed in this study as a mechanism to reduce uncertainty and refine carbon sequestration estimates over time, rather than as a means to ensure accuracy or certainty of projected outcomes. Long-term field observations are intended to support adaptive management and periodic revision of carbon accounting assumptions.

Uncertainty is inherent in forest carbon sequestration assessments due to limitations in measurement accuracy, variability in growth rates, model assumptions, and future environmental change [6,30]. In this study, uncertainty was explicitly addressed through the use of multiple baseline growth scenarios and literature-based proxy data, reflecting plausible ranges of secondary forest development under different conditions.

To enhance robustness and support adaptive management, a comprehensive monitoring framework was incorporated into the study design. Monitoring focused on two primary dimensions: (1) changes in carbon storage and emissions within forest carbon pools and (2) changes in ecological conditions, including vegetation structure, groundcover dynamics, and soil and water conservation indicators.

Permanent monitoring plots were established within both reserved secondary forest areas and afforested project areas to track long-term changes in tree growth, species composition, and carbon storage. In reserved areas, monitoring data provide reference information for adjusting baseline carbon storage estimates, while in afforested areas, plot-based measurements of diameter at breast height (DBH), tree height, and species composition support evaluation of project-related carbon sequestration outcomes.

Monitoring intervals were designed to be more frequent during early project stages and gradually reduced over time, reflecting expected changes in forest growth dynamics. This adaptive monitoring approach is consistent with Measurement, Reporting, and Verification (MRV) principles and allows for periodic refinement of carbon sequestration estimates as empirical data become available.

4.5. Implications for Carbon-Neutral Events and Forest Policy in Taiwan

The application of afforestation and IFM as a carbon offset mechanism for cultural events highlights both opportunities and challenges within the Taiwanese policy context [17]. Although afforestation is recognized by the Forest Service as a carbon reduction approach, uncertainties remain regarding institutional recognition, certification mechanisms, and transaction costs within existing carbon trading frameworks [31]. These factors may limit private-sector participation despite growing interest in nature-based solutions.

The findings of this study suggest that locally implemented afforestation projects, supported by transparent MRV frameworks and adaptive monitoring, can provide credible carbon offset opportunities while delivering co-benefits for biodiversity, recreation, and ecosystem resilience [32]. By integrating forest management with carbon accounting methodologies, such projects may contribute to bridging the gap between environmental policy objectives and practical implementation.

Overall, this study suggests that afforestation-based carbon offset strategies, when combined with improved forest management and long-term monitoring, can play a meaningful role in achieving carbon-neutral objectives for large-scale events under conditions of acknowledged uncertainty. Continued policy support, methodological refinement, and empirical monitoring will be essential to enhance confidence and scalability of such approaches in Taiwan and similar contexts.

5. Conclusions

This study suggests the feasibility of applying afforestation and improved forest management (IFM) strategies in secondary forests as a carbon offset mechanism for large-scale cultural events. In contrast to conventional economic forestry practices based on clear-cutting and monoculture plantations, the proposed approach emphasizes ecological integrity through the development of a mosaic, multi-storied forest structure. Key management considerations include the preservation of biological corridors and habitat spaces, the use of diverse native tree species, and the integration of afforestation with natural forest regeneration processes.

Rather than adopting a purely production-oriented forestry model, forest development in this study was based on existing stand structures, with management interventions designed to enhance long-term forest health and resilience. Although some planted species may have economic value under appropriate management, afforestation and IFM practices were implemented primarily to support ecological functions and carbon sequestration potential. Selective thinning and understory enrichment are recognized as important components of adaptive forest management to maintain structural complexity and ecosystem stability.

From a carbon accounting perspective, this research provides one of the early empirical applications of afforestation-based carbon offset assessment in secondary forests in Taiwan. Carbon sequestration was estimated using the Verified Carbon Standard methodology (Approved VCS Methodology VM0005 v1.2) in accordance with Measurement, Reporting, and Verification (MRV) principles. Across four baseline growth scenarios, projected CO2 sequestration over a 25-year assessment period ranged from approximately 3816 to 4523 t CO2-e. Under the modeled scenarios, carbon emissions associated with the Taipei Biennial 2020 (approximately 390 t CO2-e) were estimated to be offset between the eighth and ninth years of forest management.

To enhance robustness and address uncertainty, a long-term monitoring framework was incorporated into the study design. Permanent sample plots are planned across the entire 52.70 ha study area, encompassing both management and conservation zones, to track forest dynamics and carbon sequestration trajectories. Monitoring data will enable periodic updates of carbon offset estimates and support adaptive management through a rolling revision process, providing a practical reference for public forest management and carbon offset planning in Taipei City.

Accordingly, the estimated carbon offset timelines should be interpreted as scenario-dependent outcomes subject to uncertainty, rather than fixed or guaranteed targets. Despite these contributions, several limitations should be acknowledged. Carbon sequestration estimates at the current stage rely on scenario-based assumptions and proxy growth data, and uncertainties remain regarding long-term forest growth, disturbance regimes, and policy implementation. Future research should incorporate probabilistic modeling approaches, confidence intervals, and sensitivity analyses to further strengthen the robustness of empirical findings. Expanding similar assessments to other urban and peri-urban forest contexts would also help clarify the broader applicability of afforestation and IFM strategies for achieving carbon neutrality in cultural events and public-sector activities.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/f17020169/s1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.C. (Chihua Chang), C.C. (Chaurtzuhn Chen) and J.C.; methodology, H.L. and C.C. (Chihua Chang); software, H.L.; validation, C.W., C.C. (Chaurtzuhn Chen) and J.C.; formal analysis, C.C. (Chihua Chang), and H.L.; investigation, H.L. and C.C. (Chihua Chang); resources, J.C.; data curation, C.C. (Chaurtzuhn Chen); writing—original draft preparation, C.C. (Chihua Chang); writing—review and editing, C.C. (Chihua Chang) and J.C.; visualization, C.C. (Chihua Chang); supervision, C.C. (Chaurtzuhn Chen) and J.C.; project administration, J.C.; funding acquisition, C.C. (Chaurtzuhn Chen). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Taipei Fine Arts Museum.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Some data are derived from internal project reports and field surveys and are not publicly available.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Berndes, G.; Abt, B.; Asikainen, A.; Cowie, A.; Dale, V.; Egnell, G.; Lindner, M.; Marelli, L.; Paré, D.; Pingoud, K.; et al. Forest biomass, carbon neutrality and climate change mitigation. Sci. Policy 2016, 3, 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Pacala, S.; Socolow, R. Stabilization wedges: Solving the climate problem for the next 50 years with current technologies. Science 2004, 305, 968–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, L.J.R.; Meireles, C.I.R.; Gomes, C.J.P.; Ribeiro, N.M.C.A. Forest contribution to climate change mitigation: Management oriented to carbon capture and storage. Climate 2020, 8, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lal, R. Sequestration of atmospheric CO2 in global carbon pools. Energy Environ. Sci. 2008, 1, 86–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.H.; Costedoat, S.; Sterling, E.J.; Chamberlain, C.; Jagadish, A.; Lichtenthal, P.; Nowakowski, A.J.; Taylor, A.; Tinsman, J.; Canty, S.W.; et al. What evidence exists on the links between natural climate solutions and climate change mitigation outcomes in subtropical and tropical terrestrial regions? A systematic map protocol. Environ. Evid. 2022, 11, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook-Patton, S.C.; Leavitt, S.M.; Gibbs, H.K.; Harris, N.L.; Lister, K.; Anderson-Teixeira, K.J.; Briggs, R.D.; Chazdon, R.L.; Crowther, T.W.; Ellis, P.W.; et al. Mapping carbon accumulation potential from global natural forest regrowth. Nature 2020, 585, 545–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonner, M.T.; Schmidt, S.; Shoo, L.P. A meta-analytical global comparison of aboveground biomass accumulation between tropical secondary forests and monoculture plantations. For. Ecol. Manag. 2013, 291, 73–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. 2006 IPCC Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories; IPCC/IGES: Hayama, Japan, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Forster, E.J.; Healey, J.R.; Dymond, C.; Styles, D. Commercial afforestation can deliver effective climate change mitigation under multiple decarbonisation pathways. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 3831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Requena Suarez, D.; Rozendaal, D.M.A.; De Sy, V.; Phillips, O.L.; Alvarez-Dávila, E.; Anderson-Teixeira, K.; Araujo-Murakami, A.; Arroyo, L.; Baker, T.R.; Bongers, F.; et al. Estimating aboveground net biomass change for tropical and subtropical forests: Refinement of IPCC default rates using forest plot data. Glob. Change Biol. 2019, 25, 3609–3624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brienen, R.J.W.; Phillips, O.L.; Feldpausch, T.R.; Gloor, E.; Baker, T.R.; Lloyd, J.; Lopez-Gonzalez, G.; Monteagudo-Mendoza, A.; Malhi, Y.; Lewis, S.L.; et al. Long-term decline of the Amazon carbon sink. Nature 2015, 519, 344–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Zheng, Q. Differences between forest and conservation experts’ perceptions of forest management models in Taiwan. Q. J. Chin. For. 2005, 38, 437–447. [Google Scholar]

- Schulze, E.D.; Bouriaud, O.; Irslinger, R.; Valentini, R. The role of wood harvest from sustainably managed forests in the carbon cycle. Ann. For. Sci. 2022, 79, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kauppi, P.E.; Stål, G.; Arnesson-Ceder, L.; Hallberg Sramek, I.; Hoen, H.F.; Svensson, A.; Wernick, I.K.; Högberg, P.; Lundmark, T.; Nordin, A. Managing existing forests can mitigate climate change. For. Ecol. Manag. 2022, 513, 120186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaarakka, L.; Cornett, M.; Domke, G.M.; Ontl, T.A.; Dee, L.E. Improved forest management as a natural climate solution: A review. Ecol. Solut. Evid. 2021, 2, e12090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griscom, B.W.; Busch, J.; Cook-Patton, S.C.; Ellis, P.W.; Funk, J.; Leavitt, S.M.; Lomax, G.; Turner, W.R.; Chapman, M.; Engelmann, J.; et al. National mitigation potential from natural climate solutions. Nat. Clim. Change 2020, 10, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, P.W.; Gopalakrishna, T.; Goodman, R.C.; Putz, F.E.; Roopsind, A.; Umunay, P.M.; Zalman, J.; Ellis, E.A.; Moh, K.; Gregoire, T.G.; et al. Reduced-impact logging for climate change mitigation (RIL-C) can halve selective logging emissions from tropical forests. For. Ecol. Manag. 2019, 438, 255–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fantini, A.C.; Cristiano, S.; Alexandre, S.; Ilyas, S. Small-scale management of secondary forests in the Brazilian Atlantic Forest. Floresta e Ambient. 2019, 26, e20170690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verra. VM0005: Conversion from Low-Productivity Forest to High-Productivity Forest (v1.2). In Verified Carbon Standard (VCS) Methodology; Verra: Washington, DC, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Elias, F.; Ferreira, J.; Lennox, G.D.; Berenguer, E.; Ferreira, S.; Schwartz, G.; Melo, L.O.; Reis Júnior, D.N.; Nascimento, R.O.D.; Ferreira, F.N.; et al. Assessing the growth and climate sensitivity of secondary forests in highly deforested Amazonian landscapes. Ecology 2020, 101, e02954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, A.R.; Domke, G.M.; Doraisami, M.; Thomas, S.C. Carbon fractions in the world’s dead wood. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seibold, S.; Rammer, W.; Hothorn, T.; Seidl, R.; Ulyshen, M.D.; Lorz, J.; Cadotte, M.W.; Lindenmayer, D.B.; Adhikari, Y.P.; Aragón, R.; et al. The contribution of insects to global forest deadwood decomposition. Nature 2021, 597, 77–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poorter, L.; Bongers, F.; Aide, T.M.; Almeyda Zambrano, A.M.; Balvanera, P.; Becknell, J.M.; Boukili, V.; Brancalion, P.H.S.; Broadbent, E.N.; Chazdon, R.L.; et al. Biomass resilience of Neotropical secondary forests. Nature 2016, 530, 211–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, R.; He, H.; Zhang, L.; Ren, X.; Williams, M.; Yu, G.; Smallman, T.L.; Zhou, T.; Li, P.; Xie, Z.; et al. Climate sensitivities of carbon turnover times in soil and vegetation: Understanding their effects on forest carbon sequestration. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosciences 2022, 127, e2020JG005880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ninan, K.N.; Kontoleon, A. Valuing forest ecosystem services and disservices: Case study of a protected area in India. Ecosyst. Serv. 2016, 20, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J. Definition and characteristics of ecosystem services. Spec. News For. Res. 2014, 21, 54–57. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, J.; Liu, Y. Evaluation of economic benefits of water conservation of Taiwan’s state-owned forest resources. Collect. Appl. Econ. 2018, 104, 185–228. [Google Scholar]

- Rai, R.K.; Nepal, M.; Karky, B.S.; Timalsina, N.; Khadayat, M.S.; Bhattarai, N. Opportunity costs of forest conservation in Nepal. Front. For. Glob. Change 2022, 5, 857145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersson, H.; Ellison, D.; Mensah, A.A.; Berndes, G.; Egnell, G.; Lundblad, M.; Lundmark, T.; Lundström, A.; Stendahl, J.; Wikberg, P.; et al. On the role of forests and the forest sector for climate change mitigation in Sweden. GCB Bioenergy 2022, 27, 793–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, Q.; Li, M. Study on Decision-Making Mechanism in Response to Climate Change Uncertainty in the Field of Water Resources; Water Resources Planning Test Institute of Water Resources Administration of the Ministry of Economy: Taichung City, Taiwan, 2013; p. 400. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, J.; Wang, P.; Li, J. Analysis on demand orientation and participation ways of afforestation carbon reduction in Taiwan. Q. J. For. Res. 2010, 32, 49–58. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, S.; Khan, S.M.; Siddiq, Z.; Ahmad, Z.; Ahmad, K.S.; Abdullah, A.; Hashem, A.; Al-Arjani, A.-B.F.; Abd_Allah, E.F. Carbon sequestration potential of reserve forests present in the protected Margalla Hills National Park. J. King Saud Univ.-Sci. 2022, 34, 101978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.