Abstract

Ectomycorrhizal (ECM) fungi form key symbioses with forest trees, strongly regulating plant nutrition and stress tolerance. This review synthesizes how ECM fungi redistribute plant-fixed carbon (C) in soil, interact with soil organic matter (SOM), and mediate the uptake and allocation of nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P) and other macro- and micronutrients. We highlight mechanisms underlying ECM enhanced organic and mineral N and P mobilization, including oxidative decomposition, enzymatic hydrolysis, and organic acid weathering. Beyond C-N-P dynamics, ECM fungi also enhance acquisition and homeostasis of elements such as K, Ca, Mg, Fe, and Zn, reshaping host nutrient stoichiometry, productivity, and soil microbial community composition. We further summarize multi-layered mechanisms by which ECM improve host plant resistance to pathogens, drought, salinity–alkalinity, and heavy metal stresses via physical protection, ion regulation, hormonal signaling, aquaporins, and antioxidant and osmotic adjustment. Finally, we outline research priorities, such as using trait-based, multi-omics, and microbiome-integrated approaches to better harness ECM in forestry and ecosystem restoration.

1. Introduction

Ectomycorrhiza (ECM) is a widespread fungus–plant symbiotic structure in forest ecosystems, primarily formed by mycorrhizal fungal hyphae and plant root systems [1]. Ectomycorrhizal fungi (ECMF), via their specialized symbiotic associations with plant roots, serve as indispensable components of forest ecosystems [2]. A typical ECM structure consists of two main components: the mantle and the Hartig net. The fungal mantle envelops the root surface, extending the effective absorptive area and enhancing water and mineral nutrient uptake [3]. The Hartig net lies between the root cortex cells. Its dense, complex network enables nutrient exchange between the host plant and the fungus [4]. While the Hartig net is the primary site for exchange, the mantle protects root tips from soil stress. Together, these structures boost plant resilience to environmental changes [5,6]. ECMF exhibit high species diversity, with approximately several thousand known fungal species engaging in this symbiotic system globally [7]. Evolutionarily, this symbiosis arose independently multiple times from saprotrophic ancestors (e.g., Basidiomycota and Ascomycota). This diverse origin explains the immense functional variety seen in modern ECM lineages [8,9]. These fungi mainly inhabit coniferous and broad-leaved forests, as well as some tropical and subtropical regions [1]. These fungi form symbiotic relationships with numerous keystone forest tree species, including pines (Pinus spp.), birches (Betula spp.), oaks (Quercus spp.), poplars (Populus spp.), and others [10,11].

ECM play crucial physiological and ecological roles, particularly in plant nutrient acquisition and stress tolerance. This review synthesizes current progress on how ECMF regulate tree nutrition and stress resistance across scales. It covers processes ranging from cellular sugar and nutrient transport to ecosystem-level functions like SOM transformation. We summarize how ECMF redistribute plant-fixed carbon (C) into soils, noting that hosts allocate up to ~30% of photosynthate to ECMF to sustain hyphal growth. We also review mechanisms by which ECMF mobilize organic and mineral nitrogen (N) and phosphorus (P) and transport these nutrients to host plants. Furthermore, we discuss the mechanisms enhancing plant resistance to pathogens, drought, salinity, and heavy metals. These include physical protection by the mantle, defense priming, water regulation, ion homeostasis, and detoxification. Finally, we identify key knowledge gaps regarding ECMF function under interacting environmental drivers (e.g., drought combined with nutrient changes) and outline priorities like trait-based frameworks and multi-omics to better harness ECMF for forestry and restoration (Figure 1).

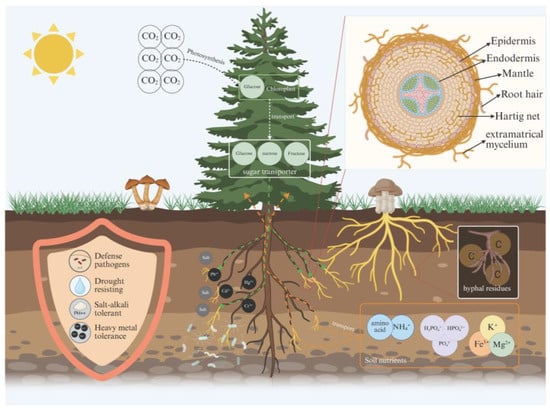

Figure 1.

Conceptual schematic of how ECM symbiosis regulates tree growth and soil processes. Trees fix atmospheric CO2 via photosynthesis and transport recent photoassimilates (e.g., sucrose/fructose) to roots through the phloem. At root tips, C–nutrient exchange occurs across the symbiotic interface, where host-derived carbohydrates sustain fungal mantle formation and growth of extramatrical mycelium. The extramatrical hyphae extend into soil to mobilize and absorb multiple nutrients, which are then transferred to the host, including inorganic N (NH4+), organic N (amino acids), inorganic P (Pi) (H2PO4−/HPO42−), and other macro- and micronutrients (e.g., K+, Mg2+, Fe3+), thereby improving host nutrition and growth. ECM symbiosis can also increase host tolerance to biotic and abiotic stresses (e.g., pathogens, drought, salinity/alkalinity, and heavy metals) through modulated rhizosphere processes and altered plant defense responses. Hyphal turnover produces hyphal residues/necromass that enter soil C pools and contribute to SOM formation and stabilization. The inset cross-section illustrates the spatial organization of ECM structures, including the epidermis, endodermis, mantle, Hartig net, and extramatrical mycelium. (Created in BioRender. Wang, Yuanhao. (2026) https://BioRender.com/1vq8j5h.).

Despite the rapidly growing literature on ECM fungi, existing studies remain fragmented across nutrient cycling, plant physiology, and stress ecology, and a unified synthesis linking nutrient acquisition mechanisms with plant stress tolerance under global change is still lacking. In this review, we aim to (1) synthesize current knowledge on how ECM fungi regulate plant acquisition of C, N, P, and other essential nutrients; (2) summarize multi-layered mechanisms by which ECM enhance host tolerance to biotic and abiotic stresses; and (3) identify key knowledge gaps and future research directions, particularly in the context of interacting environmental drivers such as nutrient limitation, drought, and anthropogenic disturbance. Key unresolved issues include the following: (1) how ECM functions shift under simultaneous nutrient limitation and climate stress; (2) the extent to which functional traits of ECM fungi determine nutrient–stress trade-offs across ecosystems; and (3) how interactions between ECM fungi, associated bacteria, and host plants jointly regulate nutrient mobilization and stress resilience.

This review is based on a comprehensive survey using Web of Science, Scopus, and Google Scholar. We retrieved publications from 2000 to 2025 using keywords such as “ectomycorrhizal fungi”, “nutrient acquisition”, “carbon cycling”, “nitrogen”, “phosphorus”, “stress tolerance”, “drought”, “salinity”, and “heavy metals”. Priority was given to peer-reviewed articles, reviews, and analyses focusing on forest tree species and experimentally validated ECM systems. Studies were screened for their focus on ECM-related plant–soil nutrient cycling and ECM regulatory effects on plant stress tolerance, with representative works across diverse ecosystems synthesized for balanced coverage.

2. Effects of ECM on Soil Nutrient Cycling and Plant Nutrient Uptake

ECM associations can shift soil and plant C-N-P dynamics in two opposing directions. They can either slow decomposition to enhance soil organic C and N storage, or accelerate turnover to reduce C and nutrient retention. The net effects primarily depend on nutrient status, host identity, and fungal functional traits [12,13] (Figure 2). Long-term field evidence links root–mycorrhizal inputs to a substantial fraction of stored soil C in boreal forests, while seedling experiments report weaker or neutral effects of ECM on soil C compared with arbuscular mycorrhiza (AM) [11,14]. Furthermore, the impacts of ECM on litter decomposition and labile C/N cycling are strongly site- and host-dependent [15]. For N, studies showed that ECM fungi can mobilize organic N via proteolysis coupled to oxidative (Fenton-type) chemistry, whereas experimental N enrichment can shift fungal communities and reduce extracellular enzyme activities, potentially weakening organic N mobilization [16,17]. For P and other minerals, experiments demonstrate that ECM drives mineral P release (e.g., apatite weathering) and creates distinct soil P partitioning compared to AM-dominated stands. Meanwhile, plant uptake responses vary. These range from enhanced P acquisition in specific hosts (e.g., Pinus and Fagus) to variable effects on base cations linked to weathering and K transport [18,19]. ECM can directly enhance plant nutrient uptake by building extensive extraradical hyphae that explore soil beyond the root depletion zone, often increasing host P acquisition under P limitation [20]. They can also improve host N nutrition by mobilizing organic N and transferring it to roots across the Hartig net [21].

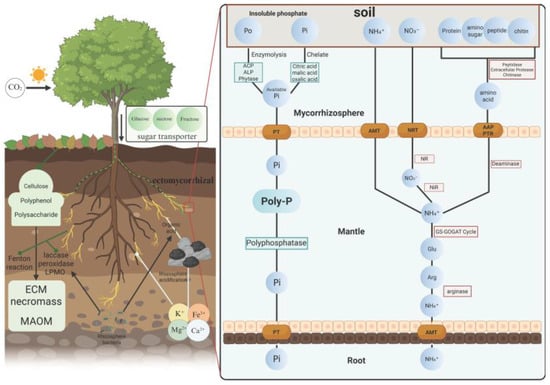

Figure 2.

Conceptual model of ECM-mediated nutrient mobilization, acquisition, and transfer. ECM hyphae decompose SOM (cellulose, polysaccharides, and polyphenols) through oxidative reactions (e.g., Fenton chemistry, laccases, peroxidases, and lytic polysaccharide monooxygenases (LPMOs)), recruiting rhizosphere bacteria, exuding organic acids that acidify the rhizosphere, and mobilize mineral cations (K+, Mg2+, Fe3+, and Ca2+). Hyphal necromass contributes to mineral-associated organic matter (MAOM). Right: In the mycorrhizosphere, ECM fungi mobilize Pi and organic P (Po) via extracellular phosphatases (acid phosphomonoesterase, ACP; alkaline phosphomonoesterase, ALP; phytase) and chelating organic acids (citric, malic, and oxalic); then, through fungal phosphate transporters (PT) to take up Pi, store it as polyphosphate (poly-P) in the mantle, and hydrolyze it via polyphosphatase before transfer to root. In parallel, ECM access inorganic N (NH4+, NO3−) and organic N (proteins, amino sugars, peptides, and chitin) using peptidases, proteases, and chitinases; nitrate is reduced by nitrate reductase (NR) and nitrite reductase (NiR) to NH4+, which is then assimilated through the glutamine synthetase/glutamate synthase (GS–GOGAT) pathway and amino acid metabolism (Glu, Arg, and arginase). Nitrogenous compounds are then delivered across the fungal mantle and transferred to root cells via ammonium transporters (AMT), nitrate transporters (NRT), amino acid permeases (AAP), and peptide transporters (PTR). (Created in BioRender. Wang, Yuanhao. (2026) https://BioRender.com/zbj7luj).

2.1. The Effects of ECMF on Soil C Cycling and Plant C Fixation

In forest ecosystems, ECM symbiosis profoundly affects the fate of C by regulating both the flow of plant C into soils and the subsequent stabilization or transformation of that C (Figure 1). Host trees allocate a substantial share of recent photosynthate to ECM fungi through the symbiotic interface. This allocation is supported by sugar transporters and sustains mantle formation and extraradical hyphal growth [21]. Importantly, ECM colonization can also enhance C fixation in host plants. In pine seedlings, ECM symbionts can increase net photosynthetic C fixation and lower the light compensation point, accompanied by higher needle chlorophyll concentrations, indicating enhanced photosynthetic performance under limiting conditions [22]. In P. sylvestris L., different ECM fungi were shown to affect host photosynthesis via changes in N and water economy, highlighting that photosynthetic responses depend on fungal identity and resource status [23]. Under drought, ECM inoculation can improve gas exchange parameters and increase non-structural carbohydrate pools in host tissues, implying plant C accumulation and partitioning [24]. Field and culture studies indicate that this C investment can be large. ECM fungi receive a substantial fraction of net assimilates, up to 30% under some nutrient-poor conditions, although the exact proportion varies with host identity, forest stand nutrient status, and fungal community compositions [6,25]. Because there is no single standardized metric for “ECMF-driven C sequestration,” studies typically quantify ECM effects using method-specific endpoints (global observational contrasts, field exclusion respiration, radiocarbon source partitioning, or mycelial production/turnover). For example, a global synthesis compared ecosystems dominated by ECM versus AM plants. It reported ~70% higher soil C per unit soil N in ECM-dominated systems. This finding held true even after accounting for climate, clay content, and productivity [26]. Field exclusion experiments that removed ECM roots/hyphae quantified ECM impacts via soil CO2 efflux, showing up to ~67% lower soil respiration when ECM roots and hyphae were present, consistent with strong ECM–saprotroph competition under some conditions [27]. Finally, ECM contributions are also quantified as extraradical mycelium (EMM) production and turnover; in a Free-Air CO2 Enrichment (FACE) × N-fertilization experiment, EMM production was modeled at ~238 kg C ha−1 yr−1 in controls and declined to ~122 kg C ha−1 yr−1 under N addition (≈51% of control), based on ingrowth bag/chitin approaches combined with production–turnover modeling [28].

Climate sensitivity of ECM-mediated C pathways is increasingly evident. Long-term soil warming experiments show that fungal communities shift in diversity and composition and that decomposition-related functional potentials can change, with implications for soil CO2 efflux and the persistence of mycorrhizal-derived C inputs. In particular, warming can alter the balance between rapid respiratory losses and slower necromass-mediated stabilization by modifying hyphal turnover rates and the expression of oxidative versus hydrolytic decomposition genes. These results suggest that ECM effects on soil C cycling should be interpreted under interacting drivers, such as warming, moisture limitation, and shifting nutrient supply, rather than under static baseline conditions [26,29,30]. A portion of this C is rapidly returned to the atmosphere via fungal and mycorrhizal root respiration, meaning that ECM are an active component of soil CO2 efflux rather than a purely storage pathway [31].

Crucially, ECM also generate a slower, more persistent C pathway through biomass turnover. Hyphal necromass is chemically distinctive, often enriched in chitin and melanized. These traits reduce decomposability and enhance binding to mineral surfaces, thereby promoting the formation of stable mineral-associated organic matter (MAOM) [32,33,34]. The stabilizing effect is trait-dependent: melanized ECM tissues decay slower and contribute disproportionately to mineral-protected pools, suggesting that shifts in ECM community composition can alter soil C persistence by changing necromass composition [33,34].

Comparative genomics show that some ECM lineages, especially those from white-rot ancestors, retain oxidative and hydrolytic enzymes. These include class II peroxidases, laccases, and lytic polysaccharide monooxygenases. These enzymes enable the modification of lignocellulose and polyphenol-rich SOM, often as part of nutrient-mining strategies [35,36]. These enzymes do not necessarily support broad saprotrophic C acquisition; rather, they can decompose complex substrates sufficiently to access organically bound nutrients, thereby coupling plant-supplied C to fungal investment in SOM processing [31,36]. At the rhizosphere scale, ECM-derived C inputs also reconfigure root exudation patterns and microbial community structure, which can feed back on SOM turnover and nutrient release, linking host C economy to soil microecology [1,6].

Finally, ECM–C interactions in tropical and subtropical forests remain underrepresented in the C cycling literature. Tropical ECM systems differ in litter chemistry, climate constraints, and soil mineralogy. These differences may lead to distinct balances between nutrient mining, decomposition, and C stabilization compared with boreal forests. Expanding biome coverage will improve the generality of ECM–C frameworks under global change [37,38].

2.2. The Effects of ECMF on Soil N Cycling and Plant N Uptake

Building on the premise that trees invest substantial photosynthate into ECMF, the first level of ECM-N coupling operates at the scale of soil N cycling, where many ECMF shift from a purely mineral N uptake strategy toward organic N mobilization as a core foraging mode [39] (Figure 2). In the extraradical hyphal zone, ECMF produce suites of extracellular proteases, peptidases, and chitinases. These enzymes depolymerize proteins, oligopeptides, and chitin into assimilable small N compounds [40,41]. In lignin-rich horizons, species such as Paxillus involutus (Batsch) Fr. deploy a trimmed brown-rot-like Fenton system. In this system, hydroxyl radicals generated by Fe-catalyzed reactions oxidatively modify aromatic structures. This process exposes organic N to subsequent enzymatic action [16,42]. This targeted oxidative hydrolytic strategy underpins the view that ECMF are potential decomposers that oxidize SOM mainly to secure N. At the community scale, variation in the prevalence of such organic N foraging traits among ECMF helps explain why stands dominated by fungi with strong SOM-N mining capacity show pronounced positive growth responses and strengthened C sinks under elevated CO2, whereas communities adapted to inorganic N regimes exhibit neutral fertilization responses [43]. Conversely, anthropogenic N inputs can erode this organic N-centered nutrient economy. Field experiments and regional gradients show that N deposition and fertilization often reduce ECM diversity and shift exploration types. These changes suppress the potential activities of N-acquiring extracellular enzymes, thereby weakening the capacity of ECM communities to tap the organic N pool [44,45,46].

A second level of coupling centers on plant N acquisition and allocation, in which ECMF act as processors and vectors integrating multiple N sources into host nutrition. Once inorganic or organic N has been mobilized in the soil, it enters the fungal N metabolism via high-affinity transporters and is assimilated predominantly through the glutamine synthetase/glutamate synthase (GS-GOGAT) pathway, with arginine functioning as a principal long-distance transport and storage form within hyphae and rhizomorphs [39,40,47]. At the Hartig net, arginine is catabolized via arginase–urease reactions to release ammonium, and both NH4+ and amino acids are transferred across the fungus–root interface to the plant, while host trees reciprocally supply carbohydrates through sugar transporters [47,48]. Genomic analyses of Laccaria bicolor (Maire) P.D. Orton and other ECMF reveal repertoires of N transporters. For instance, the fHANT-AC gene family in L. bicolor is not repressed by glutamine. This allows simultaneous utilization of nitrate and organic N, enabling fungi to integrate NO3− uptake with organic N foraging in N-poor soils [41,49]. On the host side, ECM colonization modulates the expression of plant N transporter genes and improves N uptake efficiency, but chronic N deposition can downregulate this symbiotic machinery by decreasing ECM colonization, altering fungal community composition, and changing the expression of root N transporters, ultimately constraining tree N acquisition and its coupling to belowground C allocation [46]. Host identity can strongly modulate the magnitude of ECM-mediated N acquisition. Using a 15N pulse–chase approach at an alpine treeline, Larix decidua obtained ~0–35% of its total N uptake via ECM delivery. In contrast, P. mugo Turra reached up to 41% under the same conditions, indicating species-specific dependence on fungal N supply [50]. The chemical form of N further interacts with this host dependence, and the uptake capacity varied among ECM morphotypes, implying that “N-form preference” and transfer efficiency are contingent on the particular host–fungus pairing. By contrast, nitrate can constitute an important N currency in some broad-leaved ECM systems; in Fagus–Laccaria mycorrhizas, transport-based evidence resolved active NO3− acquisition and transfer. This supports the view that NO3− use is system- and host-dependent rather than universally constrained [51]. In addition, the chemical form of N (NH4+ vs. NO3−) can influence ECM–host interactions by changing uptake routes and metabolic demands. Nitrate acquisition typically requires reduction before assimilation, whereas ammonium can be assimilated more directly; these differences affect the C/energy costs of N acquisition and may therefore modulate C-for-N exchange under ECM symbiosis [47,52]. These findings indicate that ECMF shift forests from a passive “mineralization-uptake” mode toward an active, trait-dependent “acquisition–allocation” N economy, in which the stability of C sinks is tightly linked to both organic N mobilization in soils and the efficiency of fungal–plant N transfer.

2.3. The Effects of ECMF on Soil P Cycling and Plant P Acquisition

ECMF significantly enhance soil P availability through a stepwise continuum that begins with P mobilization and proceeds to fungal P uptake (Figure 2). At the mobilization level, many ECMF mobilize mineral-bound inorganic phosphate by excreting low-molecular-weight organic acids, especially oxalic acid. These acids acidify microsites, compete for sorption surfaces, and chelate Fe, Al, or Ca to release inorganic P (Pi) from apatite and metal oxides [53]. Beyond Pi, many ECMF also mobilize organic P (Po) pools by releasing extracellular phosphatases (e.g., phosphomonoesterases and phosphodiesterases, and, in some cases, phytase), which hydrolyze soil Po compounds and liberate Pi for uptake [54]. Recent work also revises the classical view of Po decomposition by showing that several ECM taxa exhibit limited adaptive expansion of secreted phosphatases, while ECM-associated bacteria and endofungal bacteria supply key phytase and phosphatase functions that enhance Po hydrolysis and host P uptake, revealing a tripartite fungal–bacterial complementarity in ECM-enhanced P nutrition [55,56,57]. Mineral-specific oxalate exudation and oxalate crystallization by species such as P. involutus demonstrate that ECMF weathering and release of Pi are strongly constrained by mineralogy rather than being a uniform trait across substrates [58]. However, P bioavailability and the associated fungal mobilization strategies are strictly governed by soil type and pedogenesis. In acidic soils, such as Ferralsols, P is predominantly fixed by iron and aluminum oxides, necessitating the exudation of organic ligands (e.g., oxalate, citrate) for ligand exchange, whereas in alkaline or calcareous soils, fungal proton efflux is the dominant mechanism required to solubilize calcium-bound P [20]. Furthermore, soil mineralogy imposes varying constraints on P accessibility; for instance, Andosols, characterized by amorphous short-range-order minerals (e.g., allophane), exhibit extreme P sorption capacity, creating a distinct bioavailability threshold that demands higher metabolic investment from the ECM community compared to crystalline mineral matrices [59]. Following mobilization, P uptake is mediated by high-affinity H+/Pi symporters expressed on extraradical hyphae and at symbiotic interfaces, and their transcription is strongly induced under low-P supply [60,61]. In the Hebeloma cylindrosporum Romagn.–P. pinaster Aiton model, HcPT1.1 and HcPT1.2 primarily function in soil-side uptake, whereas HcPT2 is enriched at intraradical hyphae and Hartig net regions. Together, they enable directional Pi movement from soil into colonized roots. Overexpression of HcPT1.1 increases host P accumulation while reshaping HcPT2 distribution, providing direct functional evidence of transporter partitioning and synergy [2,62].

After uptake, ECMF transport P through long-distance transport, interfacial allocation, and ecosystem-level utilization. At the transport level, absorbed Pi is rapidly polymerized into polyphosphate within hyphae and rhizomorphs. This is often counter-balanced with cations such as K+, allowing efficient long-term movement and short-term buffering before depolymerization near root tips [60,63]. This Pi-poly-P interconversion and its spatial regulation are governed by the fungal PHO signaling and metabolism pathway, which coordinates poly-P turnover with external Pi status and symbiotic demand [39]. The Pht1 family of transporters in host plants plays a crucial role in P acquisition, particularly under low-P conditions. For example, Pht1.1 and Pht1.2 are primarily involved in the uptake of Pi from the soil into plant roots, while Pht1.3 is involved in the movement of Pi from the root to the xylem [64]. At the P allocation and utilization levels, Pi efflux from fungal hyphae in the Hartig net is tightly coupled to host high-affinity PHT1 transporters, and ECM symbiosis induces strong PHT1 expression in plant roots, including Pinus associated with L. bicolor, establishing the molecular basis of net Pi delivery to plants [48,65]. Community trait variation further modulates these pathways: ECM species differ markedly in oxalate release, phosphatase production, and transporter deployment, and field gradients show that enzyme allocation tracks host P deficit and soil P scarcity in a manner consistent with optimal partitioning theory [66,67]. While laboratory models elucidate these mechanisms, field-scale validation remains essential to confirm their ecological significance. In situ 33P labeling and ecosystem-level budgeting in temperate forests have demonstrated that ECM-mediated pathways account for the majority of annual P uptake. This validates that the high-affinity transport observed in vitro translates to dominant ecosystem fluxes [68]. Moreover, field observations indicate that the spatial decoupling of phosphatase activity from root biomass is driven by hyphal exploration into bulk soil, confirming that ECM fungi expand the effective P depletion zone far beyond the rhizosphere in natural settings [57]. Under long-term N deposition, many ECM forests shift toward secondary P limitation, with declined foliar P and increased N: P ratio, and restructured ECM fungal community functional traits and altered P-acquisition investment [57,69,70]. These layered mechanisms imply that future soil aging, warming, and N enrichment will increasingly select ECM communities with stronger mineral weathering, higher phosphatase investment, faster poly-P cycling, and more efficient interfacial transfer, making conservation of ECM diversity and soil chemical buffering central to sustaining forest resilience under chronic P limitation.

2.4. ECM Coordination of C-N-P Fluxes in Forest Soils

Rather than operating in isolation, the cycles of C, N, and P are tightly coupled. This coupling occurs through metabolic stoichiometry and resource optimization constraints within ECM symbiosis (Table 1). The “Gadgil effect”—the suppression of saprotrophic decomposition by ECM fungi—is fundamentally a manifestation of C-N competition. Recent evidence suggests that this interaction is not static but depends on soil stoichiometry. ECM fungi suppress decomposition primarily when they are N-limited and compete intensely with saprotrophs for organic N. By doing so, they effectively bank soil C to secure N returns [71,72]. However, this trade-off shifts under N enrichment. As N availability increases, the metabolic cost of N acquisition declines. This potentially alleviates competitive pressure on saprotrophs but simultaneously drives the system toward N-induced P limitation [73]. This C-N-P stoichiometric imbalance is becoming a critical driver of ecosystem function. Long-term N deposition datasets reveal that as N: P ratios widen, ECM communities reallocate C investment. They shift from N-mining traits (e.g., oxidative enzymes) toward P-mining strategies (e.g., phosphatases and hyphal exploration). This creates a “functional succession” to maintain stoichiometric homeostasis [57,74]. This reallocation follows optimal partitioning theory: trees allocate C to fungal partners only when the marginal benefit of nutrient return (N or P) outweighs the C cost [75]. Interestingly, the C cost of acquiring P appears to differ from that of N. Recent syntheses indicate that P mining via extensive hyphal foraging requires higher specific C investment per unit nutrient compared to mineral N uptake. This implies that P-limited forests may become larger C sinks belowground, provided that the host can sustain the high C demand of fungal partners [76,77].

P acquisition is integrated into the same C-funded framework and closely interacts with N mining. A concrete example of C–P–microbe coupling comes from Tuber melanosporum Vittad.–Q. mongolica Fisch. ex Ledeb. symbiosis in sterilized peat. In this system, mycorrhization increased seedling photosynthesis and rhizospheric P, altered root exudate sugars (e.g., galactose), reduced organic anions, and restructured rhizobacterial communities. These changes indicate that ECM can optimize host C economy while re-engineering rhizosphere P cycling [78]. Long-term N deposition frequently pushes ECM forests toward secondary P limitation and reorganizes community functional traits and P acquisition investment [69,70]. Plants supply C, fungi extract N, and bacteria release P. They function as an integrated system at the root interface. However, future N enrichment and climate stress will reshape ECM trait distributions. This will determine whether forests maintain strong C sinks or shift into more P-limited, lower-efficiency regimes.

Table 1.

Summary of ECM C-N-P coupling mechanisms and interdependencies.

Table 1.

Summary of ECM C-N-P coupling mechanisms and interdependencies.

| Coupling Type | Key Mechanism | Functional Description | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| C-N Exchange | Bidirectional Transport | Host photosynthates (sucrose) are exchanged for fungal-derived N (NH4+/amino acids) at the Hartig net interface. | [79] |

| C-N Trade-off | Gadgil Effect | ECM fungi utilize host C to immobilize soil N, limiting N availability to free-living saprotrophs and suppressing litter decomposition. | [26,80] |

| C-N Mining | Oxidative Mobilization | Fungi invest host C into extracellular oxidative enzymes (e.g., peroxidases) to liberate organic N from recalcitrant SOM. | [13] |

| N-P Stoichiometry | Functional Shift | High N availability (high N:P ratio) downregulates N-mining enzymes and upregulates P-mining strategies (e.g., phosphatase secretion). | [57,81] |

| C-P Allocation | Cost–Benefit Investment | P acquisition via extensive hyphal exploration requires higher C investment per unit nutrient compared to local N uptake, increasing belowground C allocation under P limitation. | [77] |

2.5. The Effects of ECMF on Other Nutrients

Beyond the stoichiometric regulation of C, N, and P, ECM fungi function as critical gatekeepers for rock-derived cations (K, Ca, and Mg), micronutrients (Fe and Zn), and sulfur (S). These processes involve targeted fungal weathering strategies and precise homeostatic mechanisms (Table 2). For base cations, ECM hyphae actively accelerate the dissolution of silicate minerals (e.g., biotite and feldspars) through the exudation of organic acids. This process effectively bridges the disconnect between primary minerals and tree roots [82,83]. At the molecular interface, potassium (K) uptake is further mediated by specific high-affinity transporters (e.g., HcTrk1) and outward-rectifying channels (e.g., HcTOK1). These proteins regulate K+ flux driven by the host’s demand [84]. For iron, ECM fungi employ Fenton chemistry to oxidize organic carriers or secrete siderophores to acquire Fe under limiting conditions [16]. Genomic analysis in Suillus luteus (L.) Roussel reveals that this detoxification relies on the overexpression of CDF family transporters (e.g., SlZnT1) responsible for vacuolar compartmentalization [85]. Regarding zinc (Zn), which functions as an essential micronutrient rather than a mere pollutant, ECM fungi exhibit a strict homeostatic control. Under nutrient-poor conditions, they utilize high-affinity transporters to supply the host with essential Zn. However, under excess conditions, specific fungal genotypes (e.g., Suillus) sequester surplus Zn in the fungal mantle or vacuoles to prevent phytotoxicity [86]. Regarding sulfur, ECM fungi express specific sulfate permeases (e.g., LbSul1 and LbSul2 in L. bicolor) to rapidly uptake inorganic sulfate, complementing the host’s nutritional needs [87]. We summarize these diverse elemental interactions and their representative host–fungus systems in Table 2.

Table 2.

Mechanisms and representative systems of ECM-mediated acquisition of other key nutrients.

3. ECM Enhances Plant Stress Tolerance

ECM play a crucial role in enhancing plant stress resistance. Across diverse host–fungus systems, ECM colonization is consistently associated with recognizable stress-tolerant phenotypes, supporting a broad protective function [5,88] (Figure 3). Under pathogen pressure, ECM plants commonly show fewer disease symptoms, including smaller lesions, reduced root necrosis or rot severity, and higher survival or faster recovery after infection [5,89]. Under drought, ECM seedlings often show delayed wilting, higher leaf water status, and greater biomass retention compared with non-mycorrhizal controls. Meanwhile, field observations indicate that drought frequently favors hydrophobic, rhizomorph-forming ECM taxa [90,91]. Under salinity–alkalinity stress, ECM plants typically exhibit less leaf chlorosis, reduced tissue damage, and better growth. Mechanistically, they improve ionic homeostasis by lowering sodium accumulation and maintaining a higher K-to-sodium ratio [92,93]. Under heavy metal stress, ECM symbiosis is often linked to weaker toxicity symptoms, higher biomass, and lower metal accumulation in shoots. This is consistent with metal retention on the fungal side, which restricts transfer to aboveground tissues [94,95].

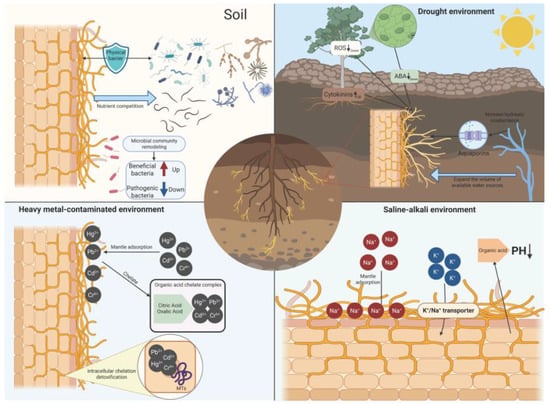

Figure 3.

Schematic model of ECM-enhanced host stress tolerance. ECM protect roots against soil-borne pathogens by forming a physical barrier, increasing nutrient competition, and remodeling the rhizosphere microbial community (enriching beneficial bacteria while suppressing pathogenic bacteria). Under drought stress, ECM may improve water acquisition by expanding the exploitable soil water volume and by regulating aquaporins, increasing hydraulic conductance, and coordinating stress signaling involving abscisic acid (ABA), cytokins, and reactive oxygen species (ROS). In heavy metal-contaminated soils (e.g., Pb2+, Cd2+, Hg2+, Cr6+), ECM can reduce metal toxicity via mantle adsorption and chelation, including the formation of organic acid (citric/oxalic acid) chelate complexes, coupled with intracellular metallothionein (MT)-mediated chelation/detoxification. In saline–alkali environments, ECM may contribute to ion homeostasis through mantle adsorption and regulation of K+/Na+ transport, and may modify rhizosphere pH via hyphae exudations. (Created in BioRender. Wang, Yuanhao. (2026) https://BioRender.com/xr3bh28).

3.1. Disease Resistance: Structural–Chemical–Immune Synergy

ECM enhance host disease resistance across multiple pathogen types and biological scales (Figure 3). At the root and rhizosphere levels, ECM reduce infection by diverse soil-borne pathogens, including oomycetes and fungi; studies have shown that ECM fungi inhibit root rot agents such as P. cinnamomi Rands in both confrontation cultures and inoculated seedlings. Quantitative studies have established that a fully formed fungal mantle can reduce the infection rate of P. cinnamomi by nearly 100% in Pinus seedlings compared to non-mycorrhizal controls through physical exclusion [96]. In forest systems, ECM can also mitigate basidiomycete diseases. For example, in the S. luteus–P. densiflora Siebold & Zucc. model, symbiosis lowers host susceptibility to Heterobasidion annosum (Fr.) Bref. and reprograms defensive gene expression. This indicates functional protection against root decay threats [89]. ECM may extend aboveground, where systemic defense priming increases resistance to foliar herbivores. However, this systemic immunity often involves a trade-off: the upregulation of the jasmonic acid (JA) pathway to resist root pathogens can suppress the salicylic acid (SA) pathway, potentially increasing susceptibility to biotrophic foliar pathogens [97]. At the community scale, common mycorrhizal networks may extend disease protection beyond the directly colonized host by facilitating belowground signal transfer and defense priming in neighboring plants, including non-host species [98]. Host-supported ECM hyphae can access non-host roots without forming typical mycorrhizal structures. Such “non-typical” colonization is often associated with enhanced induced systemic resistance in non-host plants. This implies a CMN-mediated spillover of disease resistance across plant communities [98]. For instance, in a tripartite co-culture system, ECM hyphae colonization of non-host plants activated plant–pathogen interactions and defense hormone response genes in non-host leaves, consistent with systemic defense priming [99]. Physiologically, protection begins with a combined physical and ecological filter. The mantle and Hartig net form a continuous sheath around fine roots, occupying infection sites and altering the root surface microenvironment. These physical barriers limit pathogen contact with cortical tissues and suppress early establishment. Priority occupation of space and resources by ECM hyphae at root tips further constrains pathogen colonization through niche pre-emption [96,100]. In addition, some ECM fungi release antagonistic secondary metabolites that inhibit spore germination or hyphal growth of soil pathogens, adding a chemical defense layer in the root-adjacent zone [96]. ECM also reshape rhizosphere microbial communities. Hyphal exudates and C inputs can enrich plant-beneficial or antagonistic bacteria, which indirectly narrow pathogen invasion windows and modify disease trajectories [1,101].

At the molecular scale, ECM prime host systemic immunity. In L. bicolor symbiosis, fungal chitin signals trigger root-to-shoot defense via the host CERK1 receptor and induce resistance to insects; however, jasmonic acid–salicylic acid crosstalk may generate context-dependent trade-offs, including systemic susceptibility to certain foliar bacteria [97,102]. Mechanistic syntheses show that ECM-induced defenses overlap with SAR/ISR frameworks, relying on chitin perception, JA/SA/ethylene coordination, and long-distance signal integration [103]. Yet, ECM protection is not universal; suppression is often stronger against native pathogens than exotic congeners. Host–fungus–pathogen transcriptional responses differ accordingly, implying phylogenetic and co-evolutionary specificity [5]. Overall, ECM-mediated disease resistance arises from layered physical–chemical shielding, microbiome reassembly, and systemic immune priming, while its magnitude and direction depend on symbiont–pathogen matching, host immune background, and environmental context.

3.2. Drought Tolerance: Water Acquisition and Metabolic Buffering

ECM symbiosis is widely regarded as a potential enhancer of tree drought tolerance, but the benefit depends on the “C-for-water” exchange efficiency [104]. Across nursery and short-term drought experiments, ECM colonization often improves seedling performance under water deficit. It helps maintain higher gas exchange, leaf water status, or growth relative to non-mycorrhizal controls [90] (Figure 3). However, synthesis work emphasizes that these effects are not universally positive; neutral or even negative outcomes occur in some fungus–host combinations or under mild stress, reflecting strong species and environmental contingencies [105]. Physiologically, the first line of ECM-mediated drought tolerance relates to water acquisition. Unlike AM fungi that rely mainly on hyphal surface area, many ECM fungi (e.g., Suillus) form thick, hydrophobic rhizomorphs that act as long-distance conduits, transporting water from soil micropores inaccessible to roots [106]. Drought-surviving plants frequently harbor ECM taxa with long-distance exploration types and hydrophobic rhizomorphs. These structures reduce water leakage along fungal cords and allow spatial reallocation of resources under patchy moisture [91,106]. Large-scale surveys further show that hydrophobic, rhizomorph-forming exploration types are more common in drier regions, consistent with a trait-based selection for fungal water-foraging strategies [107]. When T. indicum Cooke & Massee colonizes P. armandii Franch., it regulates key signaling molecules such as trans-2-hexenal. This alleviates oxidative damage while maintaining photosynthetic function. Consequently, the fungus plays a regulatory role in enhancing plant adaptation to abiotic stresses, including drought [108].

A second layer involves signaling and membrane transport. Split-root experiments indicate that stomatal behavior and plant water status under mild drought are governed primarily by local ABA and cytokinin balances together with host aquaporin activity, and ECM effects are therefore constrained by the host hormonal and hydraulic network [109]. Complementing this plant-side control, direct fungal regulation has been demonstrated. For instance, overexpression of a L. bicolor aquaporin increases root hydraulic conductance in Picea glauca (Moench) Voss, providing molecular evidence that fungal water channels enhance host water transport [110,111].

A third layer is metabolic protection. Under drought, ECM symbiosis often elevates antioxidant capacity and osmotic adjustment. This preserves soluble sugars and non-structural carbohydrates, thereby limiting oxidative damage and sustaining photosynthetic function [112]. These physiological buffers align with transcriptomic evidence that both partners upregulate pathways linked to redox homeostasis and osmolyte control during water deficit [113]. Finally, drought tolerance is shaped by community and genotype matching. Severe droughts tend to favor hydrophobic, rhizomorph-rich ECM lineages (e.g., suilloid fungi), which can become dominant after heat–drought events [91,114,115]. Additionally, host genetic background modulates outcomes, with ECM benefits being stronger in some genotypes than others [116]. However, these benefits come with a metabolic cost. Under severe drought, if the C cost of fungal maintenance exceeds the photosynthetic benefit preserved via water supply, the symbiosis may accelerate mortality in C-starved hosts [38].

3.3. Salt–Alkaline Tolerance: Ion Homeostasis and Interface Regulation

Under saline and saline–alkaline conditions, ECM seedlings typically display a consistent stress-tolerant phenotype compared with non-mycorrhizal controls: higher survival and biomass, better photosynthetic performance, and improved ion homeostasis. In Q. mongolica, ECM inoculation increases growth and salt tolerance, accompanied by higher chlorophyll content and stronger seedling vigor [117] (Figure 3). A hallmark response is reduced Na+ translocation to shoots and the maintenance of a higher K+/Na+ ratio. For example, P. involutus ECMs on Populus × canescens actively constrain Na+ influx and sustain K+ retention. This stabilizes Ca2+ nutrition and prevents salt-induced ionic toxicity [118]. Molecular evidence suggests that this is mediated by the selective regulation of cation transporters (e.g., HKT1-like transporters) at the fungal plasma membrane. These transporters actively modulate Na+/K+ exchange under stress [119]. Consistently, ECM symbiosis reshapes leaf physiology toward enhanced salt tolerance, including improved gas exchange and osmotic adjustment [120]. Similar phenotypes occur across systems; e.g., Scleroderma bermudense Coker improves host growth by lowering Na accumulation while promoting K and Ca uptake in saline soils [121].

Under salt–alkaline stress, ECM enhance host tolerance through multiple layers of mechanisms: ion homeostasis, tissue interface buffering, water conduction and signal regulation, and metabolic reprogramming. At the ionic level, ECM can reduce Na+ loading into the xylem and increase the K+/Na+ ratio in roots and leaves, thereby alleviating ionic toxicity and osmotic imbalance [118,122] (Figure 3). At the physiological–structural level, the extraradical and intercellular channels provided by the mantle and Hartig net can serve as a “buffering and distribution” interface for ions and water. These channels cooperate with transmembrane transport across fungal and host cell membranes. Collectively, they stabilize root water potential and water conduction function [110]. Regarding metabolic regulation, ECM symbiosis often remodels osmoprotectant and hormone levels. This process is coupled with maintaining a sufficient K+ supply. Together, these mechanisms counteract NaCl-induced oxidative stress and photosynthetic impairment [118,123]. At the whole-plant level, experimental evidence from Populus and Pinus systems shows that ECM inoculation can maintain relatively high chlorophyll content, stable root respiration, and root hydraulic conductivity under salt treatment, manifesting as improved growth and resilience. However, the magnitude of these effects depends on the fungus–host combination and salt stress intensity [92,93]. In the context of saline–alkaline soils, ECM effects are strongly constrained by substrate pH and electrical conductivity (EC). Both field and soil-controlled studies have shown that alkaline–saline conditions can select more adaptable ECM communities, and inoculation benefits exhibit distinct pH dependence and species specificity [88,124]. ECM enhance the host’s salt–alkaline tolerance by restricting Na+ upward transport and maintaining K+ supply. Additionally, they implement ion and water buffering at the mantle interface, mobilize aquaporin and hormone pathways, and remodel osmotic and antioxidant metabolism. However, these benefits exhibit significant strain–host matching and environmental dependence, which necessitates empirical screening and validation under target forest stand and substrate conditions. However, inhibition thresholds exist: fungal protection collapses when salinity exceeds toxicity limits (e.g., >150 mM NaCl), leading to the breakdown of the symbiotic interface [125].

3.4. Heavy Metal Alleviation: Sequestration and Detoxification

As rhizosphere-adjacent “biological filters”, the mantle and Hartig net prioritize metal sequestration on the fungal side. This reduces upward translocation to the xylem, thereby significantly minimizing shoot accumulation and toxicity. This “low translocation, nutrient preservation” protective strategy has been systematically demonstrated in metal-tolerant ECMF, such as the genus Suillus [94] (Figure 3). Inoculated seedlings can exhibit >50% reduction in shoot metal concentrations compared to non-mycorrhizal plants, allowing survival in lethal soils [94]. At the whole-plant level, ECM symbiosis can improve the growth and nutritional status of pine seedlings under conditions containing Pb, Zn, and Cd, and can still maintain relatively high biomass and low leaf metal burden even under high-concentration metal exposure [95]. Second, ECM mediate the complexation and precipitation of metals via extracellular organic acids (e.g., oxalic acid, citric acid, and malic acid). ECM cooperate with the high-affinity adsorption of chitin and melanin in fungal cell walls. This immobilizes metals in the extracellular space or cell wall compartment, reducing the activity of free metal ions entering the symbiotic interface [126]. Metal sulfides can be deposited on melanin-containing fungal cell walls and septa, thus providing direct evidence for the role of melanin in metal chelation and deposition [127]. For intracellular detoxification, ECMF express cysteine-rich binding proteins such as metallothioneins (MTs) and transmembrane transport systems to chelate, sequester, and efflux excess metals. For example, HcMT1 and HcMT2 in the bolete-like H. cylindrosporum have been functionally identified as key metallothioneins responding to Cu and Cd [128]. Additionally, L. bicolor and Suillus taxa have also been reported to possess multiple copies of metallothioneins and metal-responsive transcriptional characteristics [129,130]. At the population and evolutionary scales, heavy metal mining habitats select genetically tolerant ECM ecotypes. For instance, different isolates of S. luteus exhibit distinct tolerance variations to Zn, Cd, Cu, and Ni; tolerant isolates can reduce metal translocation to the host while maintaining nutrient supply [131]. Importantly, this protective effect exhibits dose and phylogenetic dependence. High-concentration metals can directly inhibit the growth and symbiotic activity of some ECMF. Furthermore, there are significant differences in tolerance and inhibition thresholds among different species and isolates. This necessitates “fungus–host–metal phylogenetic lineage” matching screening in remediation and afforestation practices [132]. Collectively, ECM alleviate plant heavy metal stress through several mechanisms. These include prioritizing metal sequestration on the fungal side and achieving biochemical deposition via cell walls and melanin. Additionally, they accomplish intracellular detoxification through metallothioneins and transport systems, while optimizing trade-offs at the community level.

4. Conclusions

ECM symbioses play a crucial role as a key interface linking host C allocation with belowground nutrient acquisition and plant stress resilience. ECM fungi form mantles and extend extraradical hyphal networks, modifying soil C, N, and P cycling, thereby influencing plant nutrient uptake. These effects may vary depending on host identity, fungal traits, and site conditions, with positive, neutral, or negative outcomes observed.

Recent advances have connected plant phenotypes more directly with mechanistic explanations. These include ECM-mediated nutrient mobilization, rhizosphere reassembly, and stress protection across various environmental pressures, such as pathogen infections, drought, salinity, and heavy metal exposure. The literature underscores the context-dependent nature of these interactions. It highlights the necessity of considering functional traits and environmental gradients when predicting outcomes.

Future work should prioritize deeper mechanistic insights, particularly under changing global conditions. This could be achieved by integrating long-term field experiments with trait-based frameworks, isotope tracing, multi-omics, and microbiome approaches. Key research directions include understanding ECM function under combined stresses, such as drought and nutrient deficiency. Another priority is developing robust host–fungus trait matching for partner selection. Finally, research should scale processes from root interfaces to stand- and landscape-level outcomes. Such work is critical for advancing practical applications in forestry, ecosystem restoration, and contaminated soil remediation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.H. and Y.W. (Yuanhao Wang); Methodology, J.Y.; Software, S.W.; Validation, S.Y., Z.Y., and C.Y.; Data Curation, D.D. and X.S.; Writing—Original Draft, Y.W. (Yuanhao Wang); Writing—Review and Editing, X.H., J.P.-M., F.Y., and Y.W. (Yanliang Wang). Y.W. (Yuanhao Wang) and L.H. contributed equally to this paper. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (2024YFF1306703), the Yunnan Technology Innovation Program (202205AD160036), the Yunnan Provincial Department of Education Basic Research Project for Young Talents (2026J0838), and the Yunnan Revitalization Talent Support Program to Jesús Pérez-Moreno and Xinhua He.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments and suggestions that improved the quality of this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Mello, A.; Balestrini, R. Recent insights on biological and ecological aspects of ectomycorrhizal fungi and their interactions. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becquer, A.; Garcia, K.; Amenc, L.; Rivard, C.; Doré, J.; Trives-Segura, C.; Szponarski, W.; Russet, S.; Baeza, Y.; Lassalle-Kaiser, B. The Hebeloma cylindrosporum HcPT2 Pi transporter plays a key role in ectomycorrhizal symbiosis. New Phytol. 2018, 220, 1185–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blasius, D.; Feil, W.; Kottke, I.; Oberwinkler, F. Hartig net structure and formation in fully ensheathed ectomycorrhizas. Nord. J. Bot. 1986, 6, 837–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kottke, I.; Oberwinkler, F. Root–fungus interactions observed on initial stages of mantle formation and Hartig net establishment in mycorrhizas of Amanita muscaria on Picea abies in pure culture. Can. J. Bot. 1986, 64, 2348–2354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonthier, P.; Giordano, L.; Zampieri, E.; Lione, G.; Vizzini, A.; Colpaert, J.V.; Balestrini, R. An ectomycorrhizal symbiosis differently affects host susceptibility to two congeneric fungal pathogens. Fungal Ecol. 2019, 39, 250–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuart, E.K.; Plett, K.L. Digging Deeper: In Search of the Mechanisms of Carbon and Nitrogen Exchange in Ectomycorrhizal Symbioses. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 10, 1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Der Heijden, M.G.; Martin, F.M.; Selosse, M.A.; Sanders, I.R. Mycorrhizal ecology and evolution: The past, the present, and the future. New Phytol. 2015, 205, 1406–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedersoo, L.; May, T.W.; Smith, M.E. Ectomycorrhizal lifestyle in fungi: Global diversity, distribution, and evolution of phylogenetic lineages. Mycorrhiza 2010, 20, 217–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohler, A.; Kuo, A.; Nagy, L.G.; Morin, E.; Barry, K.W.; Buscot, F.; Canbäck, B.; Choi, C.; Cichocki, N.; Clum, A. Convergent losses of decay mechanisms and rapid turnover of symbiosis genes in mycorrhizal mutualists. Nat. Genet. 2015, 47, 410–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.-L.; Wang, Y.-L.; Guerin-Laguette, A.; Wang, R.; Zhang, P.; Li, Y.-M.; Yu, F.-Q. Ectomycorrhizal synthesis between two Tuber species and six tree species: Are different host-fungus combinations having dissimilar impacts on host plant growth? Mycorrhiza 2022, 32, 341–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemmensen, K.; Bahr, A.; Ovaskainen, O.; Dahlberg, A.; Ekblad, A.; Wallander, H.; Stenlid, J.; Finlay, R.; Wardle, D.; Lindahl, B. Roots and associated fungi drive long-term carbon sequestration in boreal forest. Science 2013, 339, 1615–1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hicks Pries, C.E.; Lankau, R.; Ingham, G.A.; Legge, E.; Krol, O.; Forrester, J.; Fitch, A.; Wurzburger, N. Differences in soil organic matter between EcM-and AM-dominated forests depend on tree and fungal identity. Ecology 2023, 104, e3929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindahl, B.D.; Tunlid, A. Ectomycorrhizal fungi—Potential organic matter decomposers, yet not saprotrophs. New Phytol. 2015, 205, 1443–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wurzburger, N.; Brookshire, E.N.J. Experimental evidence that mycorrhizal nitrogen strategies affect soil carbon. Ecology 2017, 98, 1491–1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandez, C.W.; See, C.R.; Kennedy, P.G. Decelerated carbon cycling by ectomycorrhizal fungi is controlled by substrate quality and community composition. New Phytol. 2020, 226, 569–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rineau, F.; Roth, D.; Shah, F.; Smits, M.; Johansson, T.; Canbäck, B.; Olsen, P.B.; Persson, P.; Grell, M.N.; Lindquist, E.; et al. The ectomycorrhizal fungus Paxillus involutus converts organic matter in plant litter using a trimmed brown-rot mechanism involving Fenton chemistry. Environ. Microbiol. 2012, 14, 1477–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Op De Beeck, M.; Troein, C.; Peterson, C.; Persson, P.; Tunlid, A. Fenton reaction facilitates organic nitrogen acquisition by an ectomycorrhizal fungus. New Phytol. 2018, 218, 335–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Burslem, D.F.R.P.; Taylor, J.D.; Taylor, A.F.S.; Khoo, E.; Majalap-Lee, N.; Helgason, T.; Johnson, D. Partitioning of soil phosphorus among arbuscular and ectomycorrhizal trees in tropical and subtropical forests. Ecol. Lett. 2018, 21, 713–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köhler, J.; Yang, N.; Pena, R.; Raghavan, V.; Polle, A.; Meier, I.C. Ectomycorrhizal fungal diversity increases phosphorus uptake efficiency of European beech. New Phytol. 2018, 220, 1200–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plassard, C.; Dell, B. Phosphorus nutrition of mycorrhizal trees. Tree Physiol. 2010, 30, 1129–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nehls, U. Mastering ectomycorrhizal symbiosis: The impact of carbohydrates. J. Exp. Bot. 2008, 59, 1097–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.; Wang, J.; Liu, B.; Nara, K.; Lian, C.; Shen, Z.; Xia, Y.; Chen, Y. Ectomycorrhizal fungi reduce the light compensation point and promote carbon fixation of Pinus thunbergii seedlings to adapt to shade environments. Mycorrhiza 2017, 27, 823–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heinonsalo, J.; Juurola, E.; Linden, A.; Pumpanen, J. Ectomycorrhizal fungi affect Scots pine photosynthesis through nitrogen and water economy, not only through increased carbon demand. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2015, 109, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Wang, H.; Zhao, X.; Feng, W.; Ding, G.; Quan, W. Effect of ectomycorrhizal fungi on the drought resistance of Pinus massoniana seedlings. J. Fungi 2023, 9, 471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hobbie, J.E.; Hobbie, E.A. 15N in symbiotic fungi and plants estimates nitrogen and carbon flux rates in Arctic tundra. Ecology 2006, 87, 816–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Averill, C.; Turner, B.L.; Finzi, A.C. Mycorrhiza-mediated competition between plants and decomposers drives soil carbon storage. Nature 2014, 505, 543–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Averill, C.; Hawkes, C.V. Ectomycorrhizal fungi slow soil carbon cycling. Ecol. Lett. 2016, 19, 937–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekblad, A.; Mikusinska, A.; Ågren, G.I.; Menichetti, L.; Wallander, H.; Vilgalys, R.; Bahr, A.; Eriksson, U. Production and turnover of ectomycorrhizal extramatrical mycelial biomass and necromass under elevated CO2 and nitrogen fertilization. New Phytol. 2016, 211, 874–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, C.W.; Kennedy, P.G. Revisiting the ‘Gadgil effect’: Do interguild fungal interactions control carbon cycling in forest soils? New Phytol. 2016, 209, 1382–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pec, G.J.; van Diepen, L.T.; Knorr, M.; Grandy, A.S.; Melillo, J.M.; DeAngelis, K.M.; Blanchard, J.L.; Frey, S.D. Fungal community response to long-term soil warming with potential implications for soil carbon dynamics. Ecosphere 2021, 12, e03460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talbot, J.M.; Allison, S.D.; Treseder, K.K. Decomposers in disguise: Mycorrhizal fungi as regulators of soil C dynamics in ecosystems under global change. Funct. Ecol. 2008, 22, 955–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maillard, F.; Michaud, T.J.; See, C.R.; DeLancey, L.C.; Blazewicz, S.J.; Kimbrel, J.A.; Pett-Ridge, J.; Kennedy, P.G. Melanization slows the rapid movement of fungal necromass carbon and nitrogen into both bacterial and fungal decomposer communities and soils. mSystems 2023, 8, e00390-23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mancinelli, R.; van Bodegom, P.M.; Lankhorst, J.A.; Soudsilovskaia, N.A. Understanding the impact of main cell wall polysaccharides on the decomposition of ectomycorrhizal fungal necromass. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2023, 74, e13351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beidler, I.; Steinke, N.; Schulze, T.; Sidhu, C.; Bartosik, D.; Zühlke, M.-K.; Martin, L.T.; Krull, J.; Dutschei, T.; Ferrero-Bordera, B.; et al. Alpha-glucans from bacterial necromass indicate an intra-population loop within the marine carbon cycle. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 4048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bödeker, I.T.M.; Clemmensen, K.E.; de Boer, W.; Martin, F.; Olson, Å.; Lindahl, B.D. Ectomycorrhizal Cortinarius species participate in enzymatic oxidation of humus in northern forest ecosystems. New Phytol. 2014, 203, 245–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellitier, P.T.; Zak, D.R. Ectomycorrhizal fungi and the enzymatic liberation of nitrogen from soil organic matter: Why evolutionary history matters. New Phytol. 2018, 217, 68–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.E.; Henkel, T.W.; Williams, G.C.; Aime, M.C.; Fremier, A.K.; Vilgalys, R. Investigating niche partitioning of ectomycorrhizal fungi in specialized rooting zones of the monodominant leguminous tree Dicymbe corymbosa. New Phytol. 2017, 215, 443–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, C.W.; Nguyen, N.H.; Stefanski, A.; Han, Y.; Hobbie, S.E.; Montgomery, R.A.; Reich, P.B.; Kennedy, P.G. Ectomycorrhizal fungal response to warming is linked to poor host performance at the boreal-temperate ecotone. Glob. Change Biol. 2017, 23, 1598–1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nehls, U.; Plassard, C. Nitrogen and phosphate metabolism in ectomycorrhizas. New Phytol. 2018, 220, 1047–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalot, M.; Brun, A. Physiology of organic nitrogen acquisition by ectomycorrhizal fungi and ectomycorrhizas. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 1998, 22, 21–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucic, E.; Fourrey, C.; Kohler, A.; Martin, F.; Chalot, M.; Brun-Jacob, A. A gene repertoire for nitrogen transporters in Laccaria bicolor. New Phytol. 2008, 180, 343–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, F.; Nicolás, C.; Bentzer, J.; Ellström, M.; Smits, M.; Rineau, F.; Canbäck, B.; Floudas, D.; Carleer, R.; Lackner, G.; et al. Ectomycorrhizal fungi decompose soil organic matter using oxidative mechanisms adapted from saprotrophic ancestors. New Phytol. 2016, 209, 1705–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pellitier, P.T.; Zak, D.R. Ectomycorrhizal root tips harbor distinctive fungal associates along a soil nitrogen gradient. Fungal Ecol. 2021, 54, 101111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, R.W.; Casper, B.B. Ectomycorrhizal community and extracellular enzyme activity following simulated atmospheric N deposition. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2008, 40, 1662–1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, C.; Mueller, G.M.; Egerton-Warburton, L.M.; Wilson, A.W.; Yan, W.; Xiang, W. Diversity and Enzyme Activity of Ectomycorrhizal Fungal Communities Following Nitrogen Fertilization in an Urban-Adjacent Pine Plantation. Forests 2018, 9, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jörgensen, K.; Clemmensen, K.E.; Wallander, H.; Lindahl, B.D. Ectomycorrhizal fungi are more sensitive to high soil nitrogen levels in forests exposed to nitrogen deposition. New Phytol. 2024, 242, 1725–1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebastiana, M.; Serrazina, S.; Monteiro, F.; Wipf, D.; Fromentin, J.; Teixeira, R.; Malhó, R.; Courty, P.-E. Nitrogen Acquisition and Transport in the Ectomycorrhizal Symbiosis—Insights from the Interaction Between an Oak Tree and Pisolithus tinctorius. Plants 2022, 12, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behie, S.W.; Bidochka, M.J. Nutrient transfer in plant–fungal symbioses. Trends Plant Sci. 2014, 19, 734–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemppainen, M.J.; Pardo, A.G. Gene knockdown by ihpRNA-triggering in the ectomycorrhizal basidiomycete fungus Laccaria bicolor. Bioeng. Bugs 2010, 1, 354–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilman, B.; Solly, E.F.; Kuhlmann, I.; Brunner, I.; Hagedorn, F. Species-specific reliance of trees on ectomycorrhizal fungi for nitrogen supply at an alpine treeline. Fungal Ecol. 2024, 71, 101361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreuzwieser, J.; Stulen, I.; Wiersema, P.; Vaalburg, W.; Rennenberg, H. Nitrate transport processes in Fagus-Laccaria-mycorrhizae. Plant Soil 2000, 220, 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Wu, Y.; Su, Y.; Li, H. Implication of quantifying nitrate utilization and CO2 assimilation of Brassica napus plantlets in vitro under variable ammonium/nitrate ratios. BMC Plant Biol. 2022, 22, 392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plassard, C.; Louche, J.; Ali, M.A.; Duchemin, M.; Legname, E.; Cloutier-Hurteau, B. Diversity in phosphorus mobilisation and uptake in ectomycorrhizal fungi. Ann. For. Sci. 2011, 68, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plassard, C.; Becquer, A.; Garcia, K. Phosphorus Transport in Mycorrhiza: How Far Are We? Trends Plant Sci. 2019, 24, 794–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, J.; Yan, R.; Zhang, X.; Su, K.; Liu, H.; Wei, X.; Wang, R.; Huang, L.; Tang, N.; Wan, S.; et al. Soil organic phosphorus is mainly hydrolyzed via phosphatases from ectomycorrhiza-associated bacteria rather than ectomycorrhizal fungi. Plant Soil 2024, 504, 659–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, Y.; Zhang, M.; Cao, G.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, A.; Bai, H.; Dai, C.; Jia, Y. Endofungal bacteria and ectomycorrhizal fungi synergistically promote the absorption of organic phosphorus in Pinus massoniana. Plant Cell Environ. 2024, 47, 600–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Guo, W.; Wang, J.; Lambers, H.; Yin, H. Extraradical hyphae alleviate nitrogen deposition-induced phosphorus deficiency in ectomycorrhiza-dominated forests. New Phytol. 2023, 239, 1651–1664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmalenberger, A.; Duran, A.L.; Bray, A.W.; Bridge, J.; Bonneville, S.; Benning, L.G.; Romero-Gonzalez, M.E.; Leake, J.R.; Banwart, S.A. Oxalate secretion by ectomycorrhizal Paxillus involutus is mineral-specific and controls calcium weathering from minerals. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 12187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinsinger, P. Bioavailability of soil inorganic P in the rhizosphere as affected by root-induced chemical changes: A review. Plant Soil 2001, 237, 173–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becquer, A.; Trap, J.; Irshad, U.; Ali, M.A.; Claude, P. From soil to plant, the journey of P through trophic relationships and ectomycorrhizal association. Front. Plant Sci. 2014, 5, 548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paparokidou, C.; Leake, J.R.; Beerling, D.J.; Rolfe, S.A. Phosphate availability and ectomycorrhizal symbiosis with Pinus sylvestris have independent effects on the Paxillus involutus transcriptome. Mycorrhiza 2021, 31, 69–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amenc, L.; Becquer, A.; Trives-Segura, C.; Zimmermann, S.D.; Garcia, K.; Plassard, C. Overexpression of the HcPT1.1 transporter in Hebeloma cylindrosporum alters the phosphorus accumulation of Pinus pinaster and the distribution of HcPT2 in ectomycorrhizae. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1135483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torres-Aquino, M.; Becquer, A.; Le Guernevé, C.; Louche, J.; Amenc, L.K.; Staunton, S.; Quiquampoix, H.; Plassard, C. The host plant Pinus pinaster exerts specific effects on phosphate efflux and polyphosphate metabolism of the ectomycorrhizal fungus Hebeloma cylindrosporum: A radiotracer, cytological staining and 31P NMR spectroscopy study. Plant Cell Environ. 2017, 40, 190–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Victor Roch, G.; Maharajan, T.; Ceasar, S.A.; Ignacimuthu, S. The role of PHT1 family transporters in the acquisition and redistribution of phosphorus in plants. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 2019, 38, 171–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loth-Pereda, V.; Orsini, E.; Courty, P.-E.; Lota, F.; Kohler, A.; Diss, L.; Blaudez, D.; Chalot, M.; Nehls, U.; Bucher, M.; et al. Structure and Expression Profile of the Phosphate Pht1 Transporter Gene Family in Mycorrhizal Populus trichocarpa. Plant Physiol. 2011, 156, 2141–2154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meeds, J.A.; Kranabetter, J.M.; Zigg, I.; Dunn, D.; Miros, F.; Shipley, P.; Jones, M.D. Phosphorus deficiencies invoke optimal allocation of exoenzymes by ectomycorrhizas. ISME J. 2021, 15, 1478–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zavišić, A.; Yang, N.; Marhan, S.; Kandeler, E.; Polle, A. Forest Soil Phosphorus Resources and Fertilization Affect Ectomycorrhizal Community Composition, Beech P Uptake Efficiency, and Photosynthesis. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, F.; Krüger, J.; Amelung, W.; Willbold, S.; Frossard, E.; Bünemann, E.K.; Bauhus, J.; Nitschke, R.; Kandeler, E.; Marhan, S. Soil phosphorus supply controls P nutrition strategies of beech forest ecosystems in Central Europe. Biogeochemistry 2017, 136, 5–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuyper, T.W.; Suz, L.M. Do Ectomycorrhizal Trees Select Ectomycorrhizal Fungi That Enhance Phosphorus Uptake Under Nitrogen Enrichment? Forests 2023, 14, 467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lilleskov, E.A.; Kuyper, T.W.; Bidartondo, M.I.; Hobbie, E.A. Atmospheric nitrogen deposition impacts on the structure and function of forest mycorrhizal communities: A review. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 246, 148–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Qu, Q.; Li, G.; Liu, G.; Geissen, V.; Ritsema, C.J.; Xue, S. Impact of nitrogen addition on plant-soil-enzyme C–N–P stoichiometry and microbial nutrient limitation. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2022, 170, 108714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, C.W.; Kennedy, P.G. Melanization of mycorrhizal fungal necromass structures microbial decomposer communities. J. Ecol. 2018, 106, 468–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, E.; Terrer, C.; Pellegrini, A.F.; Ahlström, A.; van Lissa, C.J.; Zhao, X.; Xia, N.; Wu, X.; Jackson, R.B. Global patterns of terrestrial nitrogen and phosphorus limitation. Nat. Geosci. 2020, 13, 221–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; Freschet, G.T.; Wang, H.; Hogan, J.A.; Li, S.; Valverde-Barrantes, O.J.; Fu, X.; Wang, R.; Dai, X.; Jiang, L. Mycorrhizal symbiosis pathway and edaphic fertility frame root economics space among tree species. New Phytol. 2022, 234, 1639–1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terrer, C.; Phillips, R.P.; Hungate, B.A.; Rosende, J.; Pett-Ridge, J.; Craig, M.E.; van Groenigen, K.J.; Keenan, T.F.; Sulman, B.N.; Stocker, B.D. A trade-off between plant and soil carbon storage under elevated CO2. Nature 2021, 591, 599–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Averill, C.; Bhatnagar, J.M.; Dietze, M.C.; Pearse, W.D.; Kivlin, S.N. Global imprint of mycorrhizal fungi on whole-plant nutrient economics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 23163–23168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen, K.; Fisher, J.B.; Phillips, R.P.; Powers, J.S.; Brzostek, E.R. Modeling the carbon cost of plant nitrogen and phosphorus uptake across temperate and tropical forests. Front. For. Glob. Change 2020, 3, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, R.; Lu, B.; Guerin-Laguette, A.; He, X.; Yu, F. Mycorrhization of Quercus mongolica seedlings by Tuber melanosporum alters root carbon exudation and rhizosphere bacterial communities. Plant Soil 2021, 467, 391–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nehls, U.; Göhringer, F.; Wittulsky, S.; Dietz, S. Fungal carbohydrate support in the ectomycorrhizal symbiosis: A review. Plant Biol. 2010, 12, 292–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, G.R.; Peay, K.G. Stepping forward from relevance in mycorrhizal ecology. New Phytol. 2020, 226, 292–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clausing, S.; Polle, A. Mycorrhizal phosphorus efficiencies and microbial competition drive root P uptake. Front. For. Glob. Change 2020, 3, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Schöll, L.; Kuyper, T.W.; Smits, M.M.; Landeweert, R.; Hoffland, E.; Breemen, N.V. Rock-eating mycorrhizas: Their role in plant nutrition and biogeochemical cycles. Plant Soil 2008, 303, 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landeweert, R.; Hoffland, E.; Finlay, R.D.; Kuyper, T.W.; van Breemen, N. Linking plants to rocks: Ectomycorrhizal fungi mobilize nutrients from minerals. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2001, 16, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia, K.; Zimmermann, S.D. The role of mycorrhizal associations in plant potassium nutrition. Front. Plant Sci. 2014, 5, 337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruytinx, J.; Coninx, L.; Nguyen, H.; Smisdom, N.; Morin, E.; Kohler, A.; Cuypers, A.; Colpaert, J.V. Identification, evolution and functional characterization of two Zn CDF-family transporters of the ectomycorrhizal fungus Suillus luteus. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 2017, 9, 419–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adriaensen, K. Adaptive Heavy Metal Tolerance in the Ectomycorrhizal Fungi Suillus bovinus and Suillus luteus; UHasselt Diepenbeek: Diepenbeek, Belgium, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Fajardo López, M.; Dietz, S.; Grunze, N.; Bloschies, J.; Weiß, M.; Nehls, U. The sugar porter gene family of Laccaria bicolor: Function in ectomycorrhizal symbiosis and soil-growing hyphae. New Phytol. 2008, 180, 365–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serafim, C.; Ramos, M.A.; Yilmaz, T.; Sousa, N.R.; Yu, K.; Van Geel, M.; Ceulemans, T.; Saudreau, M.; Somers, B.; Améglio, T.; et al. Substrate pH mediates growth promotion and resilience to water stress of Tilia tomentosa seedlings after Ectomycorrhizal inoculation. BMC Plant Biol. 2024, 24, 1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Z.; Manninen, M.J.; Asiegbu, F.O. Beneficial mutualistic fungus Suillus luteus provided excellent buffering insurance in Scots pine defense responses under pathogen challenge at transcriptome level. BMC Plant Biol. 2025, 25, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Quesada, G.; Xu, J.; Salmon, Y.; Lintunen, A.; Poque, S.; Himanen, K.; Heinonsalo, J. The effect of ectomycorrhizal fungal exposure on nursery-raised Pinus sylvestris seedlings: Plant transpiration under short-term drought, root morphology and plant biomass. Tree Physiol. 2024, 44, tpae029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castaño, C.; Suarez-Vidal, E.; Zas, R.; Bonet, J.A.; Oliva, J.; Sampedro, L. Ectomycorrhizal fungi with hydrophobic mycelia and rhizomorphs dominate in young pine trees surviving experimental drought stress. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2023, 178, 108932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otgonsuren, B.; Rewald, B.; Godbold, D.L.; Göransson, H. Ectomycorrhizal inoculation of Populus nigra modifies the response of absorptive root respiration and root surface enzyme activity to salinity stress. Flora 2016, 224, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhsin, T.M.; Zwiazek, J.J. Colonization with Hebeloma crustuliniforme increases water conductance and limits shoot sodium uptake in white spruce (Picea glauca) seedlings. Plant Soil 2002, 238, 217–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colpaert, J.V.; Wevers, J.H.L.; Krznaric, E.; Adriaensen, K. How metal-tolerant ecotypes of ectomycorrhizal fungi protect plants from heavy metal pollution. Ann. For. Sci. 2011, 68, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hachani, C.; Lamhamedi, M.S.; Cameselle, C.; Gouveia, S.; Zine El Abidine, A.; Khasa, D.P.; Béjaoui, Z. Effects of Ectomycorrhizal Fungi and Heavy Metals (Pb, Zn, and Cd) on Growth and Mineral Nutrition of Pinus halepensis Seedlings in North Africa. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 2033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marx, D.H. The Influence of Ectotrophic Mycorrhizal Fungi on the Resistance of Pine Roots to Pathogenic Infections. I. Antagonism of Mycorrhizal Fungi to Root Pathogenic Fungi and Soil Bacteria. Phytopathology 1969, 115, 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vishwanathan, K.; Zienkiewicz, K.; Liu, Y.; Janz, D.; Feussner, I.; Polle, A.; Haney, C.H. Ectomycorrhizal fungi induce systemic resistance against insects on a nonmycorrhizal plant in a CERK1-dependent manner. New Phytol. 2020, 228, 728–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; He, X.; Yu, F. Non-host plants: Are they mycorrhizal networks players? Plant Divers. 2022, 44, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wei, X.; Zhan, J.; Yuan, J.; Zheng, G.; Zhou, W.; He, X.; Yu, F. Both a Growth-Defence Trade-Off and a Leaf N: P Stoichiometric Imbalance Can Account for Ectomycorrhizal Hyphae Inhibited Non-Host Plant Growth. Plant Cell Environ. 2025, 48, 5753–5768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marx, D.H. The Influence of ectotrophic mycorrhizal fungi on the resistance of pine roots to pathogenic infections. V. Resistance of mycorrhizae to infection by vegetative mycelium of Phytophthora cinnamomi. Phytopathology 1970, 60, 1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berrios, L.; Venturini, A.M.; Ansell, T.B.; Tok, E.; Johnson, W.; Willing, C.E.; Peay, K.G. Co-inoculations of bacteria and mycorrhizal fungi often drive additive plant growth responses. ISME Commun. 2024, 4, ycae104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gille, C.E.; Finnegan, P.M.; Hayes, P.E.; Ranathunge, K.; Burgess, T.I.; de Tombeur, F.; Migliorini, D.; Dallongeville, P.; Glauser, G.; Lambers, H. Facilitative and competitive interactions between mycorrhizal and nonmycorrhizal plants in an extremely phosphorus-impoverished environment: Role of ectomycorrhizal fungi and native oomycete pathogens in shaping species coexistence. New Phytol. 2024, 242, 1630–1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dreischhoff, S.; Das, I.S.; Jakobi, M.; Kasper, K.; Polle, A. Local Responses and Systemic Induced Resistance Mediated by Ectomycorrhizal Fungi. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 590063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehto, T.; Zwiazek, J.J. Ectomycorrhizas and water relations of trees: A review. Mycorrhiza 2011, 21, 71–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sebastiana, M.; da Silva, A.B.; Matos, A.R.; Alcântara, A.; Silvestre, S.; Malhó, R. Ectomycorrhizal inoculation with Pisolithus tinctorius reduces stress induced by drought in cork oak. Mycorrhiza 2018, 28, 247–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agerer, R. Exploration types of ectomycorrhizae: A proposal to classify ectomycorrhizal mycelial systems according to their patterns of differentiation and putative ecological importance. Mycorrhiza 2001, 11, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Defrenne, C.E.; Philpott, T.J.; Guichon, S.H.A.; Roach, W.J.; Pickles, B.J.; Simard, S.W. Shifts in Ectomycorrhizal Fungal Communities and Exploration Types Relate to the Environment and Fine-Root Traits Across Interior Douglas-Fir Forests of Western Canada. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Wan, S.; Liu, Y.; Zhan, J.; Zhang, F.; Yang, H.; Zhang, F.; Xie, X.; Shi, X.; Wang, Y.; et al. Tuber indicum colonization enhances plant drought tolerance by modifying physiological, rhizosphere metabolic and bacterial community responses in Pinus armandii. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1642071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]