1. Introduction

In Aotearoa, New Zealand (henceforth “New Zealand”), 24% of plantation forests are located on steep, erosion-susceptible lands [

1]. In many cases, these steepland plantations were deliberately established to control soil erosion that followed the large-scale clearance of indigenous forests and their conversion to grassland for pastoral farming. This strategy has proved successful (

Figure 1).

However, these plantations are typically clearfelled for commercial wood production when mature. Clearfelling on erosion-susceptible lands creates a “window of vulnerability” (WoV), where soil reinforcement by tree roots, rainfall interception, and evapotranspiration are drastically reduced, increasing erosion susceptibility by three- to ten-fold compared with mature forests [

2]. The WoV lasts approximately six years until replanted trees grow large enough to protect the soil [

2]. Over 90% of the forest plantation area in New Zealand comprises even-aged, single-species stands of radiata pine (

Pinus radiata D.Don) managed under a clearfell regime with a rotation length of approximately 28 years [

3]. Thus, the first six years (or 21%) of a 28-year radiata pine plantation rotation are in the WoV.

Many of the forests established for erosion control in New Zealand were planted over large areas in a short time, with entire catchments planted within three to five years in some cases. Because these plantation forests were managed as commercial forests for wood production, they were typically clearfelled at or near the average New Zealand rotation age of 28 years. This has resulted in very large clearfelling areas (

Figure 2) extending for several hundreds or even thousands of hectares [

4].

Erosion-susceptible lands in New Zealand are prone to rainfall-induced landslide (RIL) events, where large numbers of shallow landslides occur within areas ranging from tens to thousands of square kilometres, typically triggered by intense or long-duration regional rainfall [

5]. When a harvested forest in the WoV experiences a RIL event, increased erosion susceptibility can result in much higher landsliding rates. Because the landslide discharges are occurring on harvested sites, considerable volumes of woody debris (“slash”) are mixed in with the landslide, resulting in downstream discharges of sediment and woody material [

6].

Over the last 15 years in New Zealand, plantation forest harvesting has led to multiple sediment and logging slash impacts on downstream communities and environments [

4]. Two notable examples are as follows:

In June 2018, two RIL events in Tairāwhiti, Gisborne District, resulted in catastrophic discharges of sediment and slash from recently clearfelled plantation forests. These unauthorised discharges led to five forestry companies being prosecuted and convicted under New Zealand’s Resource Management Act 1991 [

4].

Between 11 and 17 February 2023, Tropical Cyclone Gabrielle impacted ~40% of the North Island (46,000 km

2) with rainfall recurrence intervals exceeding 250 years in places [

7]. Landslide analysis in Tairāwhiti, Gisborne, and Hawke’s Bay showed landslides within plantations preferentially occurred on slopes clear felled 3–5 years before Cyclone Gabrielle, i.e., within the WoV.

In the aftermath of Cyclone Gabrielle, a “Ministerial Inquiry into Land Use causing woody debris and sediment-related damage in Tairāwhiti and Wairoa” (MILU) was convened [

8]. The MILU recognised the link between clearfelling and landsliding on erosion-susceptible land. It recommended a halt to large-scale clearfell harvesting in Tairāwhiti, Gisborne, and the neighbouring Wairoa District, with maximum coupe sizes of 40 ha and limits to the annual clearfelled area within a catchment of ≤5% per year [

8].

Internationally, such “catchment-oriented harvesting” (restrictions on the size and location of clearfell coupes) is a widely accepted strategy [

9]. In contrast, the need for small clearfelling coupes has not been accepted unconditionally by the New Zealand forest industry [

4]. There are few examples of catchment-oriented harvesting in New Zealand, where large single-age plantation forests have been systematically harvested with coupe size and location restrictions.

This study assesses the impact of traditional versus catchment-oriented harvest schedules on financial returns, wood flows, landslide susceptibility, and WoV location and size. We test the hypothesis that catchment-oriented harvest scheduling can mitigate landslide susceptibility with minimal economic impact and predict that alleged drawbacks are surmountable.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

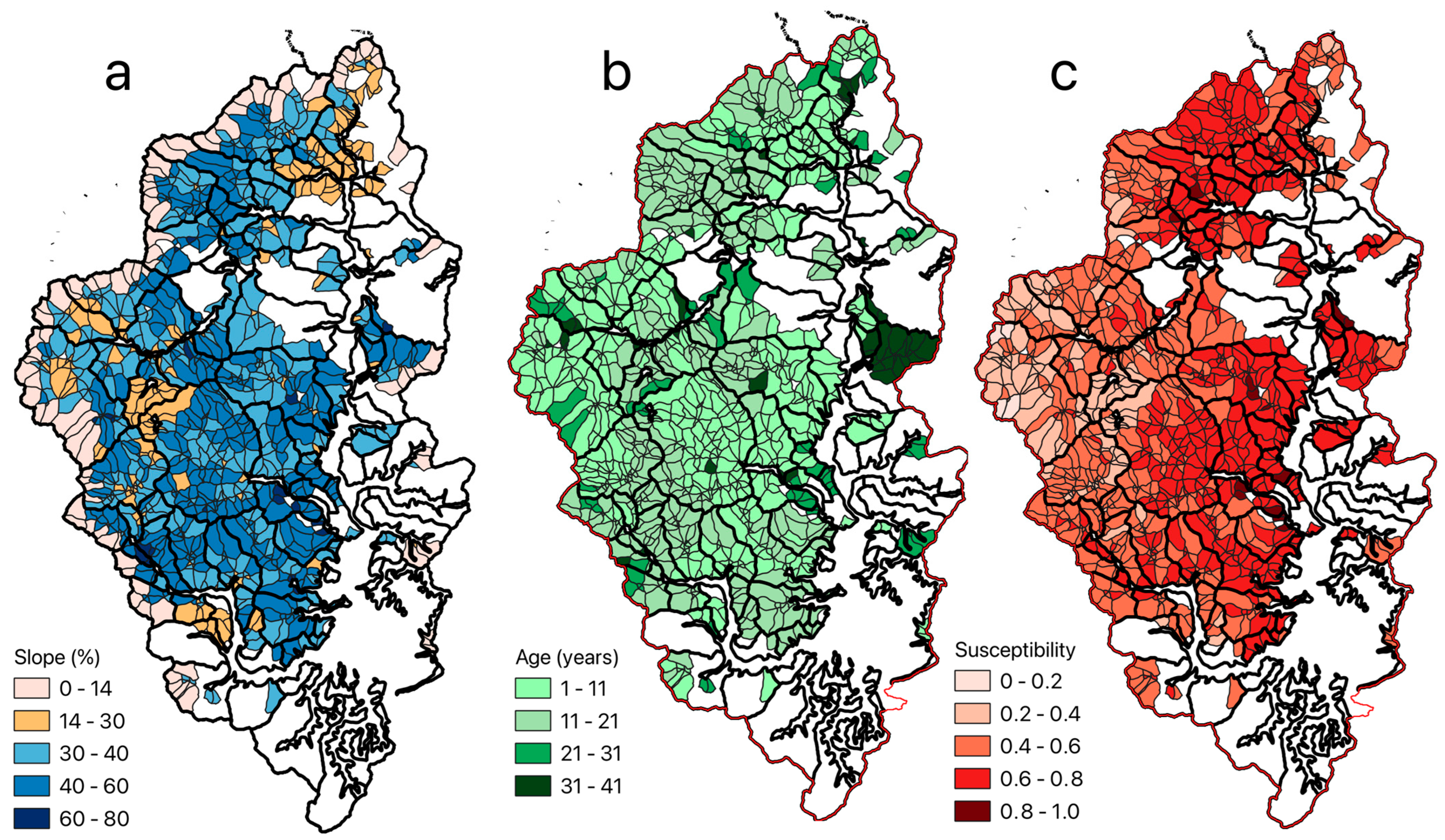

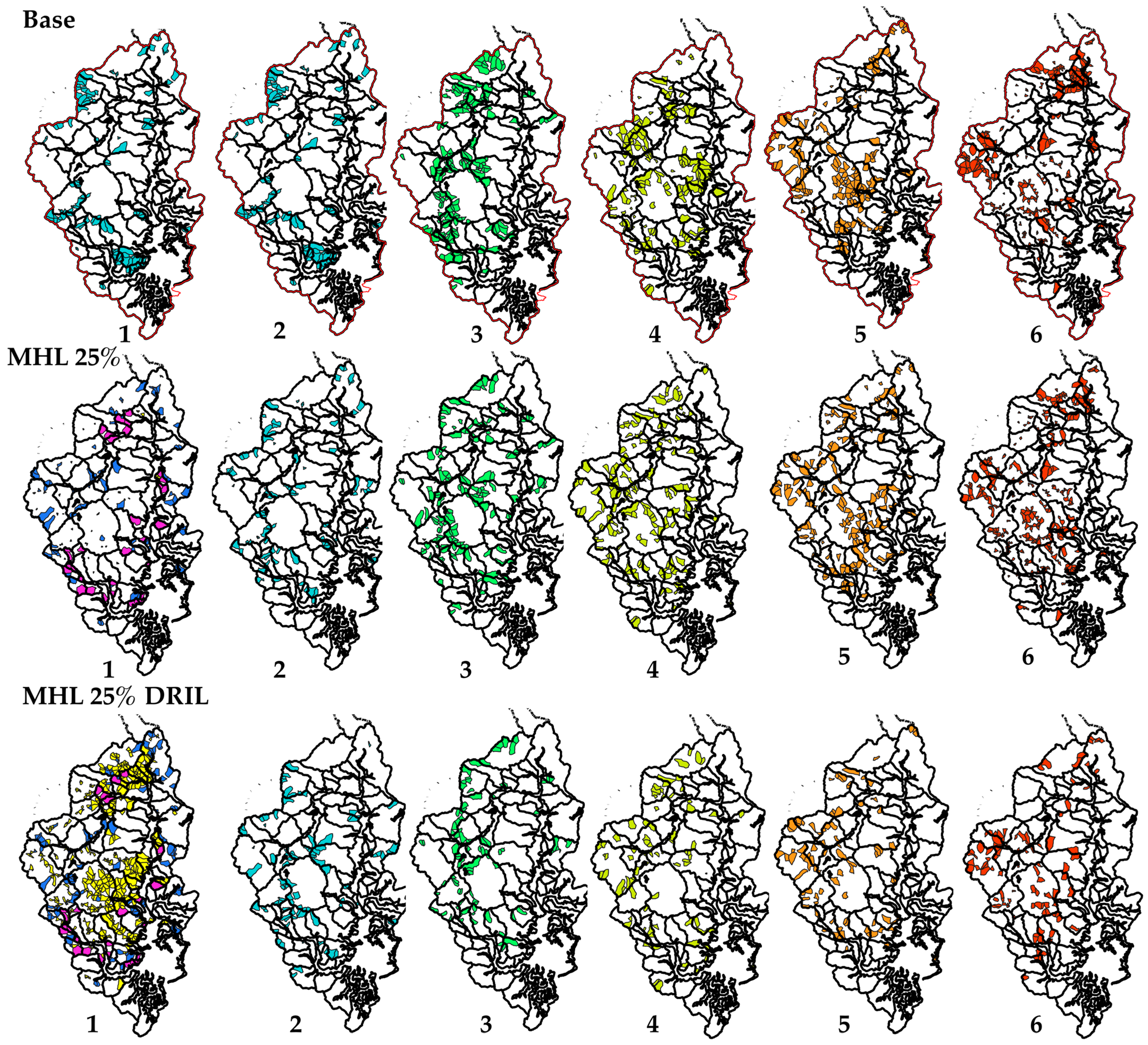

This hypothetical case study simulates radiata pine plantation management in the Uawa catchment, Tairāwhiti, Gisborne district, New Zealand (

Figure 3). This area was chosen because it was severely impacted by June 2018 storms, with prior clearfelling of several thousand hectares over 3–5 years causing catastrophic downstream effects [

8]. Much clearfelled forest was replanted in radiata pine, so large areas of even-age plantations will be harvest-ready from 2045 onwards. Unconstrained clearfell harvesting could result in landslide disasters of a similar scale to June 2018.

The Uawa catchment has a total area of 53,866 ha and a perimeter of 168 km. Terrain varies substantially across the catchment (

Figure 3c), being generally gentler in the lower part and rugged in the upper part where radiata pine plantations are mostly located. The Uawa catchment has an average slope of 32% (±20%) while the forest plantations have an average slope of 38% (±16%) (

Table 1).

2.2. The Forestry Catchment Planner

The Forestry Catchment Planner (FCP,

https://www.forestrycatchmentplanner.nz/, accessed on 4 August 2025) is a geospatial app that uses region-wide maps of plantation forest areas and ages to predict where and when clearfell harvesting is likely to occur, and, therefore, forest land will be in the WoV. The FCP then uses maps of erosion susceptibility to show if the land in the WoV is highly erosion-susceptible, and therefore more likely to generate landslides and other erosion processes. This allows visualisation of the future spatial distribution of the risk of sediment (from erosion) and harvesting slash discharges [

10]. Currently, the FCP covers the Tairāwhiti, Gisborne District, and the Hawkes Bay regions in the North Island of New Zealand, as well as the Te Tau Ihu region (comprising Nelson, Marlborough, and Tasman Districts) in the South Island of New Zealand (

Figure 3a).

In this study, we use the FCP for the following tasks:

Predicting the spatial and temporal occurrence of plantation forest clearfelling in the Uawa catchment over a 30-year planning period (2025–2055), under different catchment-oriented harvesting scenarios.

Identifying the landslide susceptibility of areas clearfelled under the different scenarios.

We then use the predicted plantation forest clearfelling for each scenario to calculate forest wood flows, cash flows, variation in landslide susceptibility due to clearfelling, and overall economic performance of forests. Thus, we can evaluate each scenario using both commercial (wood flow, cash flow, and financial metrics) and environmental (landslide susceptibility and erosion mitigation) criteria.

2.2.1. Catchment Management Units (CMUs)

While MILU recommended a 5% annual harvested area limit within catchments [

8], it did not define “catchment”, preventing practical application. FCP solves this by defining catchments as CMUs, dividing the landscape into units for visualising and managing clearfell harvesting locations in steepland forests.

CMU’s are defined using a longstanding concept in fluvial geomorphology where a fluvial system comprises three parts (

Table 2): Zone 1 comprises the headwater subcatchments from which most sediment and water originate; downstream of Zone 1 is Zone 2, the transfer zone in which, if stable, sediment inputs equal sediment outputs; and downstream of Zone 2 is Zone 3, the area where deposition is the dominant process [

11].

A CMU is a subcatchment upstream from where Zone 2 transitions to Zone 1, containing Order 1 and 2 streams that flow together into an Order 3 stream. This confluence with Order 3 streams typically occurs at a “pour point” through which all sediment and water discharges flow from a Zone 1 subcatchment into a river channel located in Zone 2.

This concept works well in the New Zealand context, since most steepland plantation forests on erosion-susceptible land are located in Zone 1. Discharges of sediment and woody debris from a CMU in Zone 1 will directly impact the natural and built environment in Zone 2, although sediment and woody debris will eventually be transported by the fluvial system down to Zone 3 or even the coastline.

2.2.2. Hill Slope Units (HSU)

Each CMU is subdivided into multiple hill slope units (HSUs), typically Order 1 or 2 catchments (“headwater streams”) dominated by steep slopes and high gradients where erosion dominates. We do this because significant variation in erosion susceptibility and landsliding can exist within CMUs. Each HSU represents areas reasonably similar in erosion susceptibility and likelihood of delivering woody debris and sediment downslope to the CMU pour-point.

The average size of HSUs within the areas covered by the FCP is 28 ha (ranging from 1 to 450 ha). HSUs were defined using the watersheds in the New Zealand River Environments Classification (REC2) database [

12]. HSUs usually correspond to Order 1 and/or Order 2 subcatchments in the REC2 classification. Some REC2 watersheds occur on both sides of the stream channel. These were split using the REC2 riverlines so that individual HSUs were defined on either side of the channel. Areas of flat land on floodplains, terraces or low fans were removed from the hill slope units. These flat lands were identified using data from the New Zealand Land Resource Inventory database [

13]. They were clipped from the hill slope units, typically excluding slopes with angles less than 8 degrees [

10].

2.2.3. Rainfall-Induced Landslide Susceptibility Layer

The rainfall-induced landslide (RIL) probability model was developed by Rosser et al. (2021) [

14]. The output from the RIL probability model is a spatial raster (or grid) covering New Zealand showing the probability of a landslide occurring in a given grid cell or pixel (32 × 32 m), when subject to a 100-year return interval rainfall event. The model was developed from existing storm landslide inventories compiled for 20 nationwide storm events during the period 1938–2019. Rainfall data for each storm event were obtained from the National Climate Database (

https://data.niwa.co.nz/pages/clidb-on-datahub, accessed on 4 August 2025). Rainfall data included 24 h maximum and storm rainfall totals. Logistic regression modelling was used to determine RIL probabilities for a 100-year return interval based on storm intensity and duration and topographic and soil factors. This model is incorporated into the Forestry Catchment Planner (FCP).

The FCP aims to identify the area and location of erosion-susceptible plantation forests within a CMU, as harvesting these forests will influence the amount of erosion and, consequently, the sediment that flows out of the CMU and into Zones 2 and 3. To manage this erosion and sediment flowing out of the CMU, we need to manage the area of erosion-susceptible land within the CMU that is in the WoV at any point in time [

10]. To this aim, erosion susceptibility was spatially defined using the outputs from the rainfall-induced landslide (RIL) prediction model developed by Rosser et al. (2021) [

14]. In the FCP, these landslide probabilities were averaged for each HSU.

The RIL susceptibility layer in the FCP allows us to visualise where rainfall-induced landslide susceptibility is relatively higher or lower (

Figure 4c). This can inform decisions about managing clearfelling and the cumulative area in the WoV in each CMU at any one time [

10].

2.3. Forest Estates Under Study

We assumed that the HSUs that intercepted the plantation forest cover of the Uawa catchment (

Figure 3b) would be managed as forest stands in our hypothetical case study. with stand ages as of 2024. Geospatial layers with this information can be downloaded from the FCP website (

https://www.docs.forestrycatchmentplanner.nz/, accessed on 6 August 2025). The planning horizon was set at 30 years (2025–2055) with 5-year planning periods.

The forest estate in the Uawa catchment comprised 1123 HSUs within 89 CMUs, covering an area of 31,899 ha, representing 59% of the total catchment area. Twenty-five per cent of the HSUs were below 7.8 ha, 50% below 20.8 ha, and 75% below 39.0 ha. The maximum HSU size was 182 ha. The forest estate was relatively young, with 42% of the area below 10 years, 46% between 10 and 20 years, 7% between 20 and 30 years, and 6% above 30 years (maximum age 39 years) (

Figure 4b). In terms of rainfall-induced landslide susceptibility, 86% of forested HSUs were above 0.4 (extreme susceptibility), with only 14% of the area below 0.4 (i.e., high or very high susceptibility) (

Figure 4c).

2.4. Estimates of Total Recoverable Stem Volume and Log Outturn

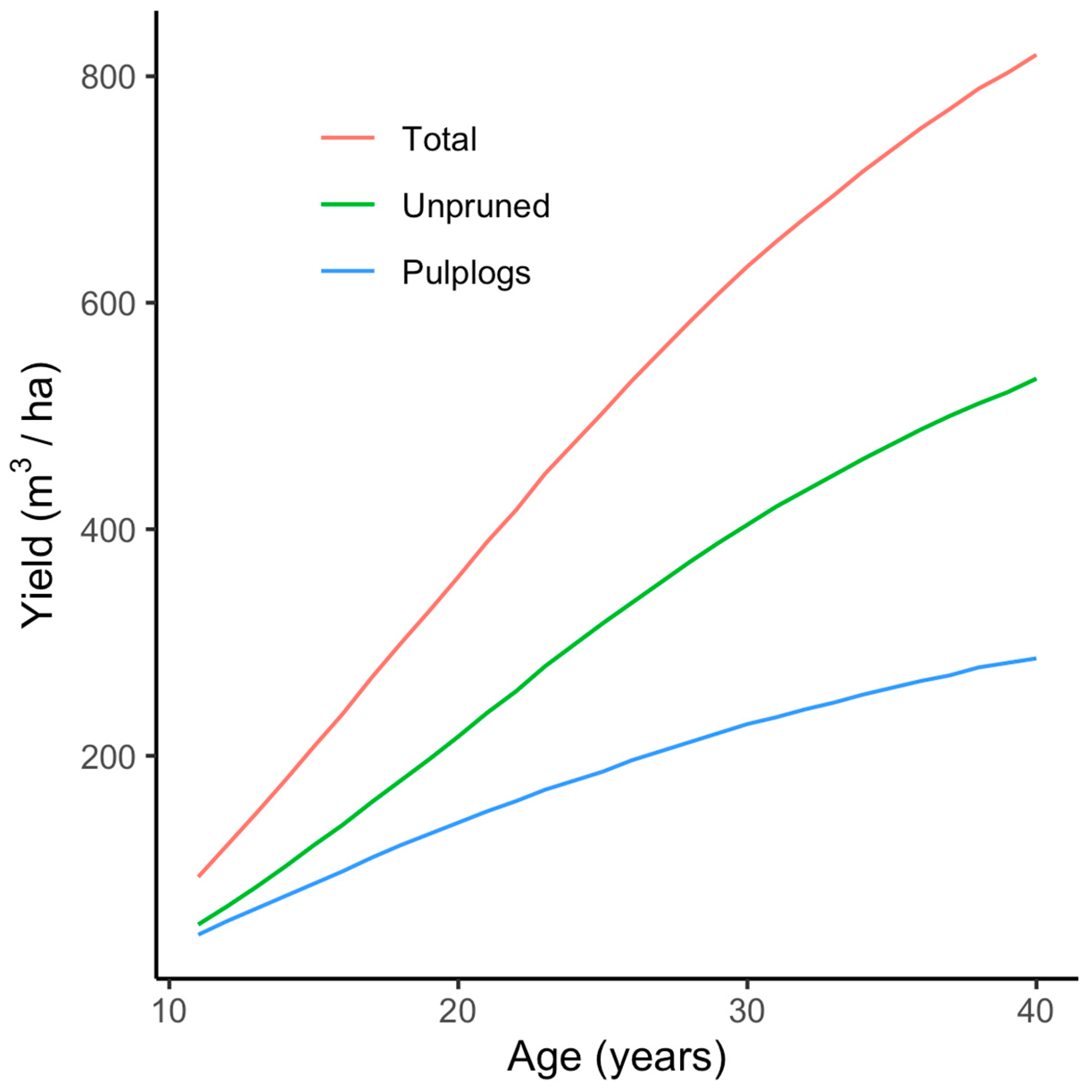

For simplicity, we used one timber yield trajectory. We used the yield table for radiata pine planted post-1989 under an unpruned, without production thinning regime from the Gisborne or East Coast region from the National Exotic Forest Description yield tables (

https://www.canopy.govt.nz/forestry-data-research/national-exotic-forest-description, accessed on 6 August 2025). We chose “Unpruned without production thinning” as it is the most common tending regime in New Zealand (55% of plantation area) [

15]. This table provides log outturn for total, unpruned, and pulplogs for ages 11–40 years (

Figure 5). This regime produces structural grade timber with high demand from China, Korea, Japan, and the domestic market (

https://www.canopy.govt.nz/market-forest/what-silviculture-regime, accessed 8 August 2025). It is worth noting that stands have different ages at the start of the planning horizon (

Figure 4b); therefore, yield predictions along the planning horizon are unique for each stand.

For tactical harvest scheduling planning, we used a fitted model to interpolate the total volume presented in

Figure 5:

y = 1037(1 − 1/e

(0.069x))

3.708, where

y is total recoverable volume (m

3/ha), and

x is age in years since planting.

2.5. Timber Value

We used indicative radiata pine prices and weighted averages for the June 2025 quarter from the New Zealand Ministry of Primary Industries (

https://www.canopy.govt.nz/forestry-data-research/indicative-radiata-pine-log-prices, accessed on 6 August 2025), i.e., unpruned A Grade 148 NZD/m

3, unpruned K Grade 138 NZD/m

3, and pulplogs (117 NZD/m

3). Considering log outturn and prices, we calculated a weighted average price as a function of age, which only marginally changed (range 133–134 NZD/m

3) from ages 20–40. For this reason, we used the average price for total recoverable volume at 134 NZD/m

3 as a constant for all ages.

2.6. Silvicultural and Management Costs

All costs related to silviculture and management were estimated based on published sources (

Table 3). Initial establishment expenses in year 0 were NZD 2034/ha and covered activities such as land preparation, planting, release spraying, and mapping. Stands were unpruned. Thinning was performed at ages 4 and 8 to reduce stocking to 450 stems/ha at a cost per operation of NZD 900/ha, representing a cost of NZD 1278/ha at a discount rate of 6% p.a. Annual operating costs covered forest management (NZD 40/ha/year) and insurance (NZD 42/ha/year) (

Table 3). The land cost was a fixed cost at NZD 10,000/ha charged at the beginning of the planning horizon and recovered at the end of the 30-year planning horizon.

2.7. Harvesting, Roading, and Transport Costs

Harvesting costs were estimated for each HSU based on the Visser Costing Model (VCM) [

16,

17]. The VCM calculates the harvesting cost (NZD/m

3) as a function of slope (%), total recoverable volume (m

3/ha), and stand area (ha). The current road network for our case study comprises 202.911 km within 31,899 ha, which equates to a road density of 6.35 m/ha. We assume these are primary roads, while access to secondary and spur roads were calculated according to the VCM, in which roading cost depends mainly on stand area (ha) and total recoverable volume (NZD/m

3). For further details about the VCM see

Appendix A. Transport costs to a mill were estimated at 19 NZD/m

3, assuming a cartage distance of 100 km and transport carried out by a log truck [

18].

We also added a premium to those units with their centroids within a buffer of 200 m from primary roads, as road construction costs will be minimal compared with areas where those roads are not available. Roading costs for these units were considered zero.

2.8. Accounting for Fixed Costs

We considered fixed costs due to land value, stumpage, and existing roads. Because the total area for the case study was 31,899 ha, the land value was NZD 263,450,609 (land value at year 0 minus discounted land value at year 30). Considering an administration cost of 82 NZD/ha/year over the total forest estate, the annual value of the series over 30 years amounts to NZD 43,466,815. The current road length within the forest estate is 202.911 km. Using past road construction costs (pers. comm. Robin Webster, 7 February 2025) corrected for inflation, we arrived at a value of 137,091 NZD/km for primary roads. Based on that, we consider that existing roads could be valued at NZD 27,817,271. Stumpage was obtained by multiplying the total recoverable volume times the net price (gross price minus harvesting, roading and transport cost) for each HSU at the start of the planning horizon. When the difference between price and costs was negative, we considered the stumpage to be zero. The total stumpage value for the forest estate was NZD 153,562,623. Therefore, the total fixed cost at year zero, considering land value, stumpage and existing roads was NZD 488,297,318.

Optimisation models, such as those used for harvest scheduling, typically exclude fixed costs from the objective function as they do not affect the optimal solution among feasible production plans. They are considered in post-optimisation or subsequent decision-making [

19].

2.9. Tactical Planning Model

The proposed spatially explicit tactical model aims to determine a harvest schedule for all forest stands located in the Uawa catchment, maximising profit (NPV, IRR) while maintaining a non-declining yield (NDY) and controlling rainfall-induced landslide susceptibility. All costs and revenue were discounted at a rate of 6% for calculation of NPV.

The tactical model is described by four components: decision variables, parameters (or known values), an objective function, and constraints, described in more detail below.

2.9.1. Decision Variables

The decision variable selected is an integer binary variable, i.e., it takes either a value of 0 or 1 but not a fractional value. There are as many variables as stands and periods.

| xit | A binary variable that indicates whether stand i is harvested in period t (1) or not (0) |

where

i ∈ A (stand, A is the set of stands);

t: 1, 2, …, m (time period).

2.9.2. Auxiliary Variables

Auxiliary variables are a combination of decision variables and parameters. They do not influence the final solution but document and keep track of management quantities relevant for decision-making. For this case study, there are two auxiliary variables:

| Ht | An auxiliary variable to account for the total volume harvested in period t; |

| St | An auxiliary variable to account for the weighted sum of rainfall-induced landslide (RIL) probability times areas harvested in period t. We hypothesise this value as a surrogate for landslides and therefore discharges of sediment and woody debris. |

2.9.3. Parameters

The parameters of the model refer to specific values that characterise the forest and its management at the tactical level. Parameters describing the forest estate include the stand areas, recoverable volumes along the planning horizon, and RIL probabilities, among others. A list of these parameters is given below:

| A | Set or list of all HSUs (stands) that are within the Uawa catchment forest estate. |

| C | Set or list of all catchment management units (CMUs) intersected with the forest estate. Each CMU has one or more HSUs and may have an area without forest cover. |

| Cj | Set or list of all HSUs within a particular CMU j. For each CMU in list C, there is a list of stands which are within CMU j. |

| m | Number of periods, e.g., for 6 periods of 5 years each, m = 6. |

| ai | Area of stand i (ha). |

| vit | Total recoverable volume (m3/ha) that could be harvested from stand i in period t (period t goes from 1 to m). |

| si | Susceptibility to rainfall-induced landslide (RIL) of stand i when harvested. |

| NPVit | Net present value (NZD/ha) from harvesting stand i in period t. |

The

NPVit is an auxiliary parameter derived from harvesting 1 ha of spatial unit

i in period

t. Therefore

where

pit is the net price per cubic metre at mill gate considering the harvesting, roading, and transport cost estimated using the VCM [

16,

17], from unit

i in period

t,

Cs is the discounted silvicultural cost of establishment and thinning after harvesting, and

r is the interest or discount rate (6% in this study).

2.9.4. Objective Function at the Tactical Level

The objective function aims to maximise the net present value from harvesting the stands over the planning horizon. This is represented by

2.9.5. Constraints at the Tactical Level

- (a)

Area constraints: Each stand can only be harvested once along the tactical planning horizon (30 years) or left unharvested:

- (b)

The total volume harvested in each period, being an auxiliary variable, is calculated as follows:

- (c)

Non-declining timber yield. This constraint ensures that volumes harvested do not decline over the planning horizon,

- (d)

Aggregated RIL susceptibility per period: The RIL susceptibility from harvested areas in each period, being an auxiliary variable, is calculated as follows:

- (e)

Declining RIL susceptibility. This constraint ensures that aggregated RIL probabilities are declining along the planning horizon,

- (f)

Non-declining RIL susceptibility. This constraint ensures that aggregated RIL susceptibilities are non-declining along the planning horizon,

- (g)

RIL susceptibility is allowed to vary by no more than 10% from one period to the next. This constraint ensures that aggregated RIL susceptibilities does not greatly change along the planning horizon,

2.10. Optimisation Algorithm

The tactical spatially explicit harvest schedule problem was programmed using the Operations Research language MATHPROG, read using package Rglpk (version 0.6-5.1) and solved using the GUROBI (version 12.0.3) commercial package [

20] in the R system for statistical computing [

21]. Both R packages, and particularly GUROBI, provide a high-level interface to R for solving large-scale linear programming (LP) and mixed-integer linear programming (MILP) problems.

2.11. Scenarios Analysed

Tactical planning was carried out for the following scenarios.

2.11.1. Base Scenario

Tactical harvest scheduling, which is the core of this study, was programmed for the forest estate described in

Section 2.3, considering maximising the NPV of the harvest schedule over a planning horizon of 30 years, with time aggregation into 5-year periods, and subject to non-declining yield (NDY) constraints. During the tactical planning horizon (30 years), each stand should be harvested at most once. Here, it is implicitly assumed that we are only concerned with first-harvest and that replanted stands will not reach a profitable age within the planning horizon. This is a reasonable assumption given the age distribution of the forest estate (see

Section 2.3) and structural regime rotations of about 28 years. The minimum harvest age was set to 20 years while there is not maximum.

2.11.2. Catchment-Oriented Harvest Schedule Scenarios

The forest estate under study was divided into stands equivalent to the HSUs, which were contained within CMUs as developed from the FCP [

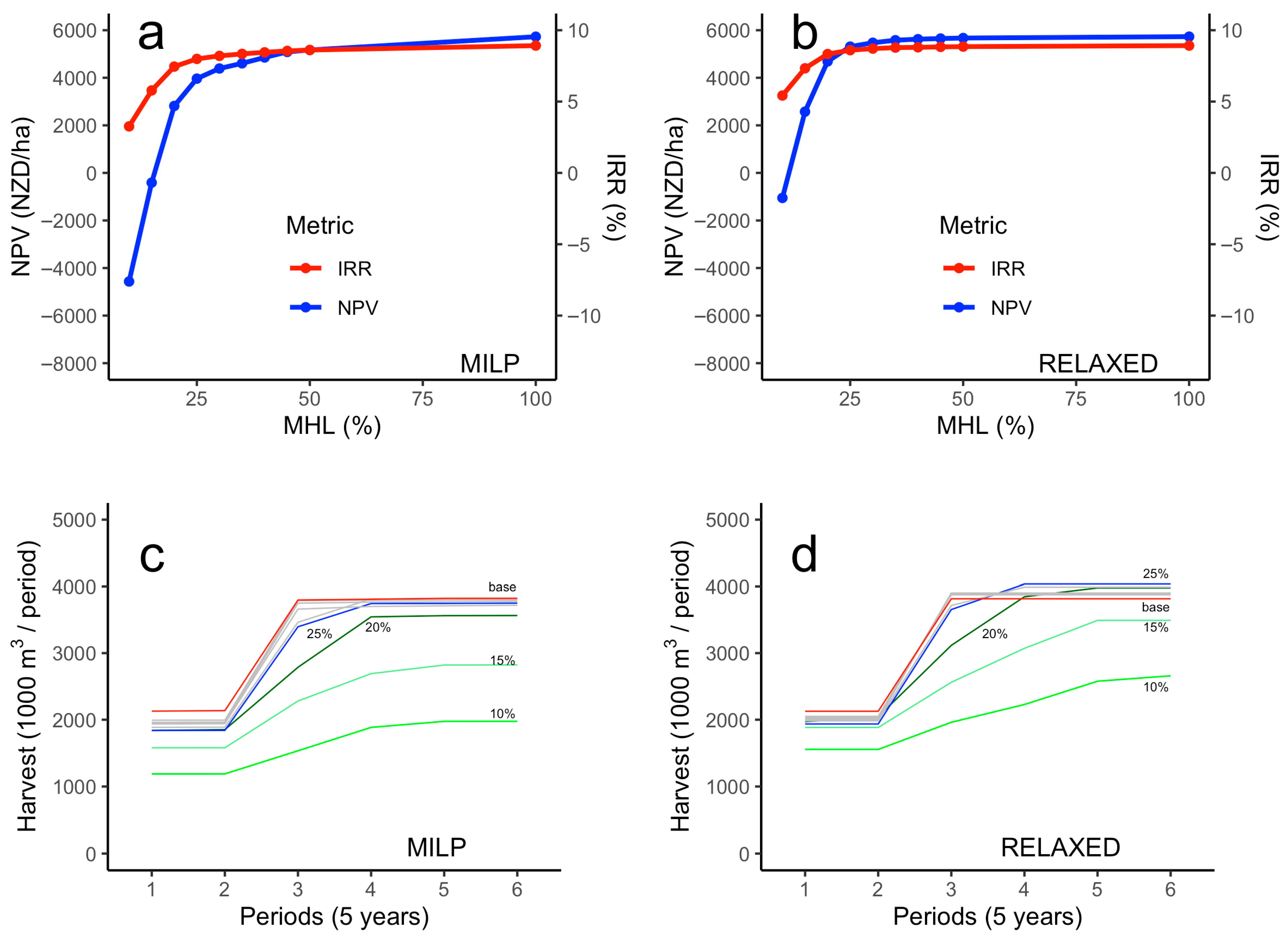

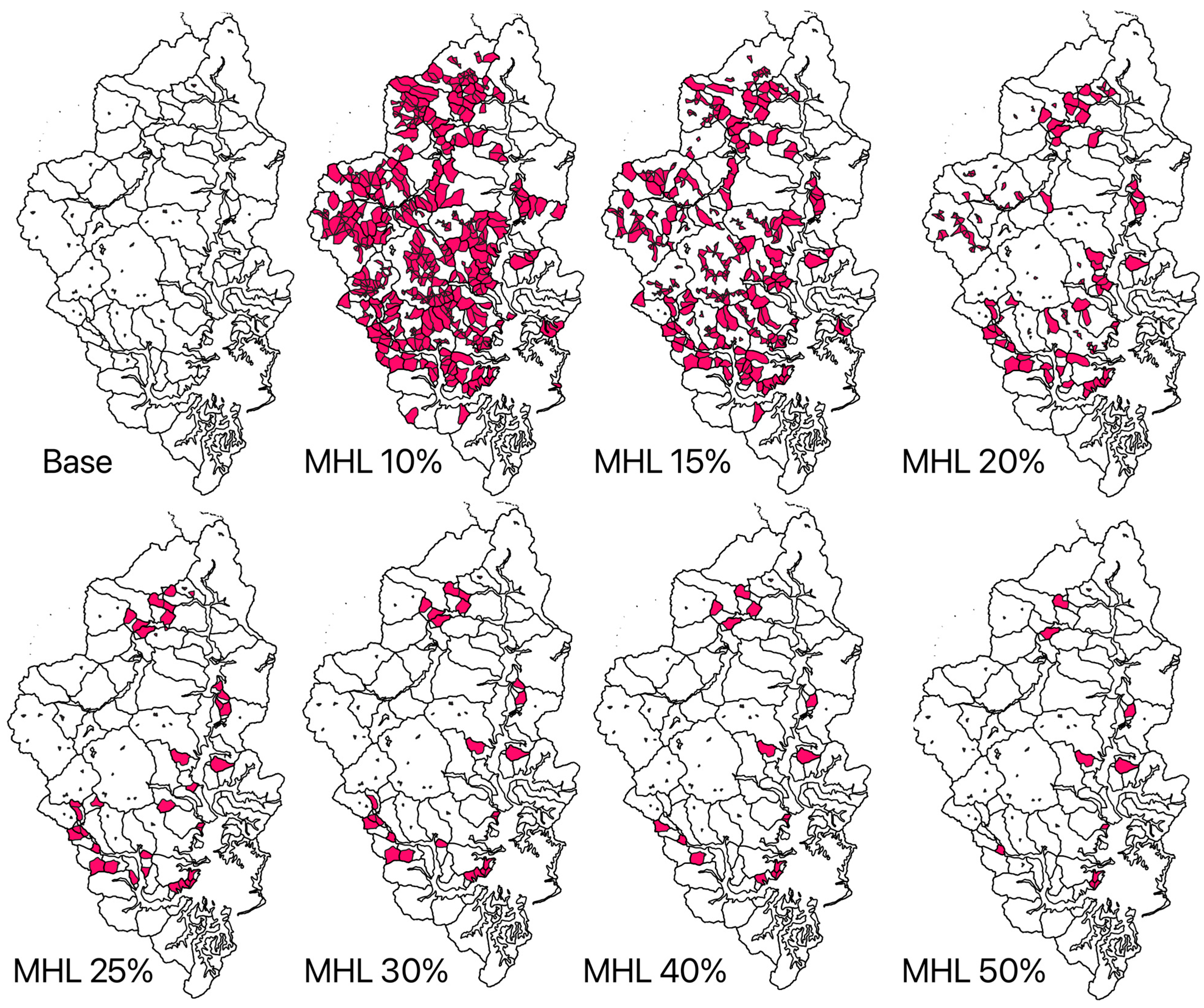

10]. Under the catchment-oriented harvest schedule, we took the base scenario and then added restrictions so that no more than a given percentage of each CMU would be harvested at any given five-year period. We tried different maximum harvesting levels (MHL) (10% to 50% of the CMU area with 5% steps) to assess the effect of such a policy on profitability.

2.11.3. Scenarios Including Proxies of Rainfall-Induced Landslides

Taking the previous best catchment-oriented harvest schedule scenario (i.e., the one considered best within MHLs 10%–50%), we added a representation of rainfall-induced landslide susceptibility. This proxy was calculated as the cumulative sum of the HSU areas harvested times their RIL probabilities, for each period. We then tested declining and non-declining susceptibility constraints, and aggregated susceptibility allowed to vary by no more than 10% from one period to the next. The idea behind this policy will be to spread the RIL susceptibility of the landscape over time, so that we do not observe periods of high susceptibility followed by periods of lower susceptibility.

2.11.4. Variable Relaxation

During this stage, we performed some model improvements, particularly decision variable relaxation for a small subset of HSUs in order to better adapt the model to reality. Most HSUs are harvested once along the planning horizon; however, some HSUs are left unharvested because if harvested, they would render the problem infeasible. This would usually happen for large units within small CMUs. Therefore, these units are allowed to be harvested in partialities over several periods.

4. Discussion

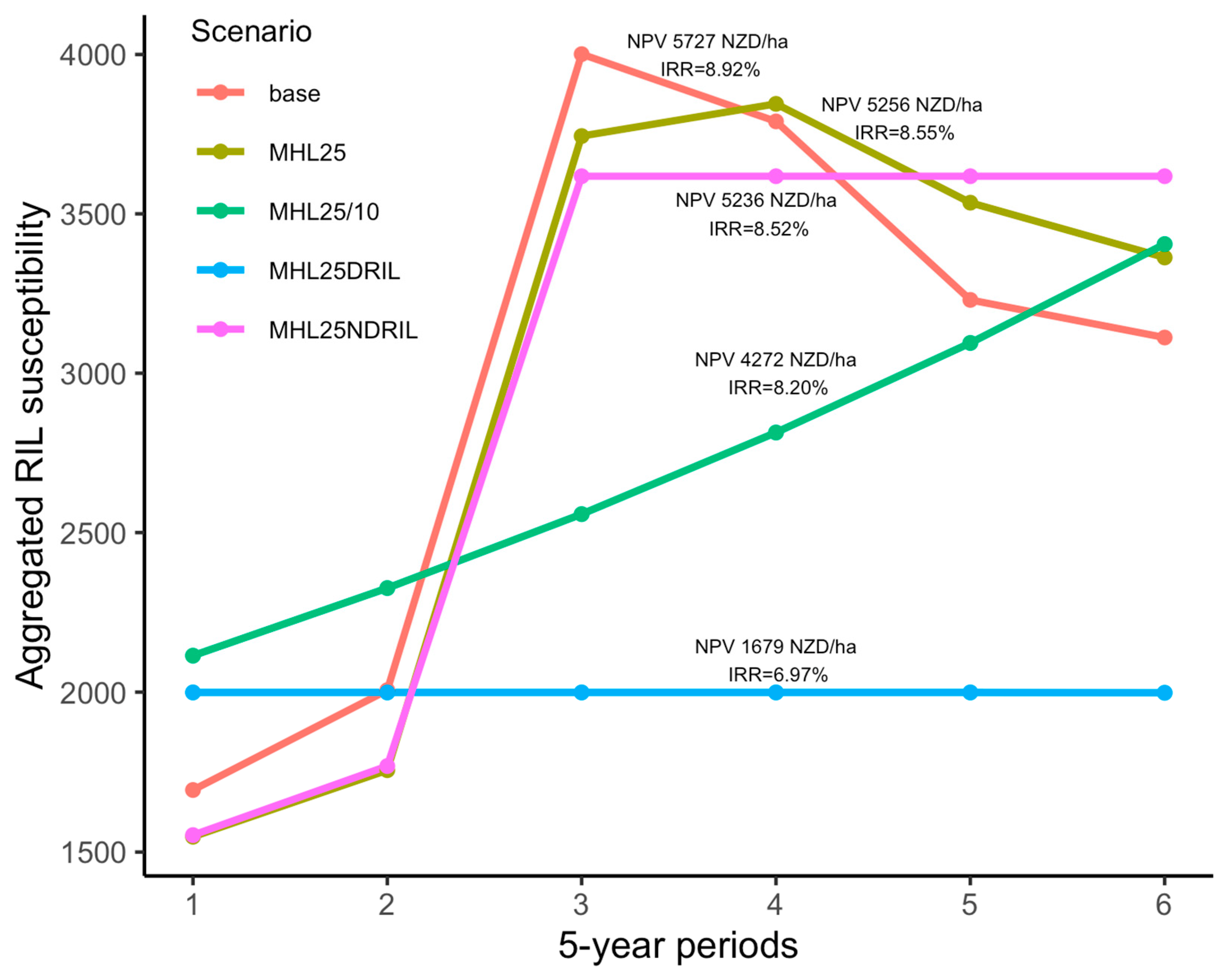

Radiata pine plantation management has been shown to be highly profitable, particularly in the North Island of New Zealand. Our hypothesis that catchment-oriented harvest planning profitability (IRR 8.55%) would not drastically differ from business-as-usual policy (IRR 8.92%) was confirmed. These IRRs are considered robust for radiata pine and other exotic plantation species such as Douglas-fir (

Pseudotsuga menziesii (Mirb.) Franco), eucalypts (

Eucalyptus spp. L’Hér.), and blackwood (

Acacia melanoxylon R.Br.) in New Zealand [

22]. Even in our harshest scenario in which we kept the aggregated RIL susceptibility constant along the planning horizon, the IRR was still highly competitive and equal to 6.97% p.a.

The minimal reduction in profitability when implementing catchment-oriented harvest scheduling is particularly significant given the current regulatory environment in New Zealand. Following Cyclone Gabrielle, stakeholders have called for restrictions on plantation forestry in erosion-prone areas. Our results demonstrate that meaningful reductions in RIL susceptibility can be achieved through spatial and temporal harvest constraints while maintaining commercially viable returns.

In our catchment-oriented harvest scheduling approach, land is divided not according to the limits of stands historically planted but according to HSUs, which behave hydrologically as a unit. These hill slope units typically represent Order 1 or 2 catchments (“headwater streams”), dominated by steep slopes and high stream gradients, where erosion is the dominant landscape process. These HSUs are fully contained within CMUs, which discharge through a “pour point” onto built and natural environments in the downstream transfer and depositional zones.

Once HSUs and CMUs are defined, a limit can be placed on the maximum area that can be clearfell harvested in any single period along the planning horizon within each CMU. We have called this threshold the Maximum Harvest Level (MHL), expressed as a fraction of any CMU, e.g., MHL 15% means that not more than 15% of any CMU could be harvested at any single 5-year period. For the base scenario, we ran a tactically explicit harvest scheduling model maximising the NPV subject to non-declining yield (NDY) constraints. We then ran further scenarios in which MHL constraints were added to the base simulation, testing MHLs in a series from 10% to 50% with 5% steps. Thus, for these new scenarios, we maximised the NPV subject to NDY and MHL constraints. Imposing the MHL constraints in the range 10%–20% drastically reduced profitability. In comparison, for MHLs 25% and larger, differences in profitability with the base scenario were relatively small. Based on the results of our study, we consider that an MHL of 25% struck a good balance between profitability and limiting the maximum area that could be harvested in any CMU in any single 5-year period.

When running the tactical harvest scheduling model under the MHL 25% constraint, we found that 47 out of 1123 HSUs were left unharvested at the end of the planning horizon because they represented more than 25% of the CMU. This is something likely to happen in reality, where CMUs are relatively small in area and composed of a small number of HSUs, or when HSUs are large compared with the CMU size. As these HSUs are only a small proportion of the total number of HSUs (4.2%), we relaxed the solution for those particular cases, i.e., instead of using binary 0–1 variables, we used continuous variables in the 0–1 range. As an example, an HSU unit left unharvested (binary variable equal to zero) could be relaxed, allowing the decision variable to take fractional values, meaning that the stand could be harvested over several periods in partialities. For example, 0.3 means that 30% of that HSU would be harvested in that period. Such a strategy of using binary variables for most of the forest estate and continuous fractional variables for the units that exceeded 25% of the CMU proved to be technically and financially feasible. This condition of small CMUs or CMUs with only a few large HSUs is likely to occur in other forest estates, suggesting that relaxing the solution is a useful option.

A proxy of rainfall-induced landslide susceptibility was constructed as the product of the area harvested times RIL susceptibility calculated for each period. This proxy was then forced to be as constant as possible. This strategy would allow the spreading of risk from rainfall-induced landslides along the planning horizon, avoiding years where stands in the WoV had high RIL susceptibility, followed by years where stands in the WoV had low RIL susceptibility. We achieved such a condition by applying declining RIL susceptibility constraints, i.e., ensuring that the aggregated value of area harvested times RIL probabilities declined or stayed the same from one period to the next. Given that the information about RIL susceptibility is widely available at the HSU level, it follows that it could be routinely included in tactical harvest scheduling planning in the Gisborne Region.

Following Cyclone Gabrielle, the Ministry for the Environment (2023) established the “Ministerial Inquiry into Land Use” (MILU) to address damage caused by woody debris and sediment in Tairāwhiti and Wairoa. Identifying a clear connection between clearfell logging and landslides on fragile terrain, the MILU proposed ending large-scale harvesting in these regions. Specifically, they recommended capping harvest plots (coupes) at 40 hectares and ensuring no more than 5% of any single catchment is clearfelled annually. We found that our model aligns well with MILU recommendations. The median of our 1123 HSUs is 20 ha, while 75% are below 39 ha. For those units exceeding 40 ha, we can enforce harvesting less than the whole HSU every year with continuous fraction variables in the range 0–1. In relation to the second part of the statement, i.e., no more than 5% of each CMU is harvested each year, our results also align well because an MHL of 25% means that over the 5-year planning period, the clearfell harvest is limited to 25% or 5% per year.

Adjacency constraints are a common practice in forest management in other areas around the world, which prevent neighbouring units from being concurrently harvested so that the maximum size of clearcuts does not exceed statutory or policy limits [

23]. Harvest scheduling now routinely incorporates such constraints to address multiple objectives, including erosion control, biodiversity conservation, and mitigation of storm impacts on forests [

23,

24,

25,

26]. In our catchment-oriented harvest scheduling plan, we have not considered adjacency constraints because the HSUs represent subcatchments which are hydrologically independent of other HSUs. Then, it is worth asking whether an adjacency constraint will have any effect on rainfall-induced landslide risk when using the FCP methodology.

Where neighbouring HSUs drain to different streams, it would make no sense to impose adjacency constraints to reduce RIL susceptibility. However, there might be some space here to consider the case of HSUs that contribute to the same water and woody debris flow pathway—for example, those on opposite slopes of the same subcatchment; in that case, adjacency may play a role. We suggest here that adjacency constraints might be necessary for a reduced subset of HSUs in order to harvest these units in different periods.

Implicitly, the MHL 25% scenario implies a greenup period of 5 years. Consider that during the first 5-year period, no more than 25% of the CMU will be harvested. During the second period, this condition will be repeated. Then, at least some units harvested during the first and second period will be neighbours, where the ones harvested during the first period will have a 5-year-old plantation. Reference [

2] defines the concept of “WoV” as the time lapse following forest removal when steep land is vulnerable to rainfall-induced landslides. This WoV may vary between 1 and 8 years after clearfelling, although years 2–4 seem to be the most critical. In our case, we consider that five years would allow radiata pine plantations to reach 6–8 m in height and achieve complete canopy cover after planting in the Tairāwhiti, Gisborne region, which is a condition for landslide density to drastically drop [

2].

Study limitations present several opportunities for further investigation. First, reshaping current forest stands to HSUs may take a few years and some planning for harvesting and the plantation establishment. Therefore, taking the decision today to start a catchment-oriented harvest scheduling will not give immediate results and will need a transition period. Second, two or more forest owners may be present in a given CMU, and therefore, harvest scheduling would need coordination between them. We may find that some CMUs are only controlled by one forest owner, and that some CMUs may have several forest owners, where trade-offs might be necessary. Third, we have not modelled temporal variability in storm frequency and intensity, which climate change projections suggest may increase in New Zealand [

27]. Finally, the model assumes harvesting operations proceed as planned; in reality, market conditions and weather events may force deviation from model-optimised schedules.

Another counterargument that could arise is that harvesting HSUs spread over the landscape might impose higher operational costs. Our take on this is that the HSUs are big enough so that operational costs will not increase. In fact, the VCM cost model [

16,

17] shows that for areas greater than 20 ha, harvesting and roading costs only marginally increase per m

3. In our particular case, nearly 50% of the HSUs were below 20 ha subject to marginal increases in harvesting and roading costs.

A further counterargument is that harvesting systems may not suit HSU-based harvesting units. We argue the contrary: catchment-oriented harvest scheduling suits conventional steepland harvesting systems. It is routine to set skylines on ridges for harvesting steepland forests in New Zealand [

6]. However, haul distances rarely exceed 300–500 m between ridges [

28]. These skyline distances are comfortably within values for many Uawa catchment HSUs. For large HSUs, those distances could be achieved by subdividing the HSUs. Detailed operational planning is needed to implement catchment-oriented harvesting, particularly in broken terrain, but difficulties are likely surmountable in most cases.

The range of piece sizes resulting from the extended harvesting age may pose operational challenges. The tactical planning shows that some harvesting along the planning horizon will involve trees 45+ years reaching up to 80 cm in dbh. Feller-bunchers typically handle trees up to 45–60 cm dbh [

29,

30], with productivity declining as stems approach machine capacity limits [

31,

32]. Similarly, cut-to-length harvesters, even with maximum cutting capacities of 75–80 cm dbh depending on harvesting head specifications [

33], demonstrate a declining processing efficiency at larger stem sizes [

34], with cycle times increasing substantially near these cutting capacity limits [

35]. Based on the above, some operational difficulties and increases in harvesting costs are expected to arise as a result of piece size, particularly on HSUs where the rainfall-induced landslide probability is high.

Our model, while currently theoretical and not yet field-tested, suggests that catchment-oriented harvest scheduling is technically and financially feasible. We predict that reshaping stands to conform to hill slope units and harvesting no more than 25% of each CMU over 5 years (5% per year) may increase landscape resilience and reduce rainfall-induced landslide susceptibility. Besides, constraining the weighted sum of areas harvested times their RIL susceptibility to stay constant will ensure spreading the risk equally over successive periods. This catchment-oriented approach would likely be more ecologically and socially acceptable than traditional unconstrained clearcuts with only marginal reductions in profitability.