Abstract

This study explores shrub–herb configuration patterns in the northern and southern mountains of Lhasa and examines associations between slope aspect, soil properties, and plant community composition. By comparing plant communities on shady and sunny slopes (n = 15 plots), we found that shady slopes supported higher species diversity (Shannon index: 3.62 vs. 3.14) and more even distributions. Exploratory regression analyses suggested that soil moisture, salinity, and pH may be associated with the occurrence patterns of native woody species, though these relationships require validation with larger sample sizes. Principal component analysis identified several recurring shrub–herb associations, including Rosa sericea Lindl. with Cynoglossum amabile Stapf & Drummond and Argentina anserine (L.) Rydb., and Cotoneaster adpressus Bois with Taraxacum mongolicum Hand.-Mazz. and Carex myosuroides Vill. These associations exhibited higher co-occurrence frequencies across plots. Our findings provide preliminary guidance for shrub–herb configuration and ecological restoration in this region. This study offers baseline data and hypotheses for vegetation restoration, forestry greening, and ecological protection in the northern and southern mountain regions of Lhasa, though expanded research is needed to validate these exploratory patterns.

1. Introduction

The unique geographical environment and climate of the Qinghai–Xizang Plateau have created distinctive ecosystems, making it one of the most biodiverse regions in the world [1]. Lhasa, located on the Qinghai–Xizang Plateau, serves as the political, economic, and cultural center of the Xizang Autonomous Region [2]. With the rapid development of urbanization, ecological degradation has intensified, negatively affecting the livelihoods of local residents and the regional ecological balance. In response to this challenge, the Lhasa municipal government launched the Northern and Southern Mountain Greening Project in 2012, a flagship initiative for ecological restoration in this cold and arid region. The afforestation area of this project has reached 8.04 × 104 hm2 (hectare = 10,000 m2) [3]. The northern and southern mountains of Lhasa span elevations from approximately 3600 to 4200 m, with diverse slope aspects creating distinct microclimatic zones. Vegetation distribution follows an elevational gradient, with shrub-dominated communities in the lower elevations (3600–3850 m) transitioning to sparse alpine vegetation above 4000 m [3]. However, due to harsh natural conditions including poor soil fertility, water scarcity, and extreme climate, the project has faced significant challenges. A primary issue has been the inappropriate selection of non-native woody species without adequate consideration of local environmental conditions, particularly slope aspect and soil characteristics. This has resulted in low survival rates and the ecological phenomenon described as “green in the first year, yellow in the second, and dry in the third”.

Currently, research on afforestation in Tibet primarily focuses on seedling technology [4,5], cultivation techniques [6], rapid propagation methods [7], plant cold resistance and drought tolerance traits [8,9], and site conditions and afforestation model exploration [10,11]. However, few studies have systematically examined the native shrub–herb associations that naturally occur in the Lhasa mountain regions, nor how these associations relate to slope aspect and soil conditions. Understanding these natural vegetation patterns is critical for developing science-based restoration strategies using locally adapted species.

Native plant communities represent time-tested assemblages that have adapted to local environmental constraints. By characterizing these natural associations and their relationships with environmental factors, we can identify appropriate species combinations for restoration plantings. This approach is particularly important in high-altitude environments where harsh conditions limit the pool of viable species. These shrub–herb configurations represent understory vegetation patterns beneath shrub canopies or in open shrublands. Fire is not a significant disturbance factor in these high-altitude, cold-arid environments, allowing natural succession patterns to persist relatively undisturbed.

Therefore, this study aims to investigate native shrub–herb vegetation patterns in the northern and southern mountains of Lhasa to inform ecological restoration practices. Specifically, we seek to: (1) compare plant community composition and diversity between shady and sunny slopes; (2) examine how environmental variables—particularly slope aspect and soil properties—influence native species distributions; and (3) identify consistent shrub–herb plant combinations with potential for use in restoration planting.

We tested the following hypotheses:

H1.

Plant community composition and diversity significantly differ between sunny and shandy slopes due to micro climatic variations (e.g., moisture, temperature, solar radiation).

H2.

Soil physicochemical properties, particularly moisture, pH, and salinity, are closely associated with the distribution of native woody species.

H3.

Stable and recurring shrub–herb associations can be identified across plots, offering ecologically viable configurations for restoration.

Through this analysis, our study provides a scientific foundation for selecting appropriate native species and designing site-adapted shrub–herb configurations to enhance the success and sustainability of afforestation efforts on the Qinghai–Xizang Plateau.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Plot Establishment and Data Collection

This study was conducted during July–August 2024 in the northern and southern mountain regions of Lhasa (91°06′ E, 29°36′ N), across an elevation range of 3650–3850 m. Lhasa, one of the world’s highest cities, lies in south-western China on the central Tibetan Plateau, immediately north of the Himalaya [12]. The city experiences a plateau temperate semi-arid monsoon climate: mean annual temperature 7.4 °C, relative humidity 30%–50%, precipitation 200–500 mm, and >3000 h of sunshine [13,14,15]. Prominent climatic features are strong solar radiation, low rainfall, cold winters, cool summers and large diurnal temperature ranges. Topographically, the area is dominated by mountains that decline in elevation from north to south; the central–southern sector is occupied by the broad middle valley of the Lhasa River [13]. A stratified systematic sampling approach was employed to establish 15 square plots (10 m × 10 m), with 8 plots on shady slopes and 7 on sunny slopes. Plot locations were selected in areas representing natural vegetation communities while avoiding recently afforested or disturbed sites.

2.2. Vegetation Survey

In each plot, a full census of vascular plant species was conducted, recording the following parameters: (1) All species present, identified to the species level; (2) Species frequency, based on occurrence in 25 systematically placed 1 m2 subquadrats per plot; (3) Life form classification (tree, shrub, herb, or liana); (4) Relative abundance for each species. It should be noted that frequency-based measurements do not account for individual plant size, age, or biomass, which may affect interpretations of species dominance. Plant identification was performed by trained botanists (authors N.T., X.L., and J.W.) using regional flora references (Flora of Xizang [Juss.]). Voucher specimens for unidentified species were collected and deposited in the Xizang University Herbarium (LSNS-2024-001 to LSNS-2024-054), with taxonomic verification performed using authenticated herbarium specimens.

2.3. Soil Sampling and Analysis

Soil samples were collected from each vegetation plot using the five-point sampling method (four corners and center). Surface debris was cleared, and soil cores (0–20 cm depth) were extracted using a 5 cm diameter soil auger. The five subsamples were composited and homogenized per plot. Soil moisture content was determined immediately upon return to the laboratory using the oven-drying method (fresh samples at 105 °C for 24 h). Subsequently, samples were air-dried at room temperature for chemical analyses, crushed, and sieved through a 1 mm mesh prior to analysis of other soil properties. The following soil properties were analyzed with a soil analyzer (HED-Q800ZDH; Shandong Holder Electronic Technology Co., Ltd., Weifang, China) using standardized methods: (1) Soil moisture content: Oven-drying method at 105 °C for 24 h; (2) pH: Glass electrode method (1:2.5 soil:water); (3) Electrical conductivity (EC), total dissolved solids (TDS), and salinity (SAL): Conductivity meter in a 1:5 soil:water extract; (4) Available phosphorus: Olsen method (0.5 M NaHCO3 extraction); (5) Available potassium: Ammonium acetate extraction and flame photometry; (6) Ammonium nitrogen (NH4+–N): Indophenol blue colorimetric method; (7) Nitrate nitrogen (NO3−–N): Cadmium reduction method. Each parameter was measured in triplicate, and mean values were used for statistical analysis.

2.4. Environmental Variables

The following environmental parameters were recorded for each plot: (1) Elevation (via GPS); (2) Slope aspect (compass; classified as sunny [315–45°] or shady [135–225°]); (3) Slope gradient (clinometer); (4) Geographic coordinates (GPS). All plots were established in areas with minimal recent anthropogenic disturbance. Sites were classified as having low to moderate historical disturbance based on the following criteria: (1) absence of recent mechanical disturbance or construction; (2) minimal evidence of intensive grazing (assessed by dung presence and vegetation trampling); (3) no visible signs of invasive species dominance (though some non-native species were present at low frequencies). Most plots represented naturally regenerating vegetation communities 5–10 years post-disturbance.

2.5. Species Diversity Indices Analysis

Species diversity indices were calculated for each plot using Shannon-Wiener (H’) and Simpson (D) indices: H’ = −Σ(pᵢ × ln pᵢ), D = 1 − Σ(pᵢ2), where pᵢ represents the relative frequency of species i. Differences between sunny and shady slopes were assessed using Mann–Whitney U tests (α = 0.05) due to non-normal distribution of diversity data.

2.6. Environmental Associations with Species Distribution

To assess relationships between environmental variables and species distributions, univariate logistic regressions were performed for each woody species (tree/shrub). Presence/absence (1/0) was used as the dependent variable, and predictors included: (1) Elevation; (2) Soil moisture (%); (3) Soil pH; (4) Soil salinity (dS/m); (5) Slope aspect (binary: 0 = sunny, 1 = shady. Regression coefficients (β), standardized coefficients, and p-values were reported. Due to the exploratory nature of the sample size, relationships with p < 0.10 were interpreted cautiously.

2.7. Principal Component Analysis

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was performed on the species presence/absence matrix (15 plots × 54 species) to identify recurring shrub–herb associations. The PCA used a correlation matrix to standardize variables, and components with eigenvalues > 1.0 were retained. Species and plot scores from the first two principal components were plotted, and species with absolute loadings > 0.4 were considered indicative of co-occurrence. All statistical analyses were conducted using XLSTAT 19.2.2 (Addinsoft, Paris, France) and R version 4.3.0 (R Core Team, Vienna, Austria).

3. Results

3.1. Species Composition

According to the statistical analysis (Table 1), a total of 54 plant species were identified across the 15 sampling plots, belonging to 27 families and 51 genera. The family with the highest number of species was the Asteraceae (Dumort.), with 12 species, accounting for 22.22% of the total species in the plots. This was followed by the Rosaceae (Juss.), with 5 species, accounting for 9.25% of the total species. In terms of plant life forms, herbaceous plants dominated, while woody plants and shrubs were less abundant. There were 38 herbaceous species, 10 shrub species, 5 tree species, and 1 liana species. In addition, invasive alien species such as Datura stramonium L., Galinsoga parviflora Cav., Senecio vulgaris L., and Sonchus oleraceus L. were also identified within the plots. Overall, the plant species in the northern and southern mountain regions of Lhasa are relatively limited, with Asteraceae plants being widespread and shrubs dominating the main forest communities.

Table 1.

Species Survey Statistics of the North and South Mountains of Lhasa.

3.2. Analysis of Plant Community Differences Between Shady and Sunny Slopes in the Northern and Southern Mountains of Lhasa

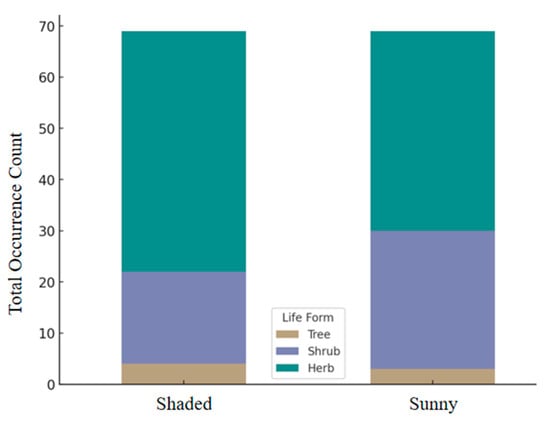

This study compared the plant communities on the shady and sunny slopes of the northern and southern mountains in Lhasa to investigate the effects of slope aspect on plant community composition and diversity. The results indicated significant differences in both the composition and diversity of plant communities between the shady and sunny slopes. Tree species had a low frequency of occurrence on both the shady and sunny slopes. Shrubs were distributed relatively evenly on both slopes and grew widely. Herbaceous plants were the dominant plant type on both the shady and sunny slopes (Figure 1, Table 2). In terms of species diversity (Table 2), diversity index analysis showed that the Shannon index (3.62) and Simpson index (0.97) on the shady slopes were higher than the Shannon index (3.14) and Simpson index (0.95) on the sunny slopes. Mann–Whitney U tests revealed that the differences in Shannon index (U = 10, p = 0.048) and Simpson index (U = 12, p = 0.089) between slope aspects were statistically significant or marginally signifiqcant, respectively. These results indicate that the plant communities on the shady slopes exhibit higher species diversity and more uniform species distribution. Overall, shrubs and herbaceous plants are the dominant plant communities on both the shady and sunny slopes. The more humid environment on the shady slopes provides more suitable growth conditions for herbaceous plants and some tree species, promoting higher species diversity. In contrast, the drier and higher light intensity conditions on the sunny slopes limit tree growth, allowing shrubs to dominate and resulting in lower species diversity.

Figure 1.

Distribution of plant life forms (tree, shrub, herb) on shaded and sunny slopes in the northern and southern mountain regions of Lhasa.

Table 2.

Comparison of Shannon and Simpson Indices of Plant Communities on the Sunny and Shaded Slopes of Lhasa City Mountains.

3.3. Regression Analysis of Native Woody Species and Environmental Factors in the Northern and Southern Mountains of Lhasa

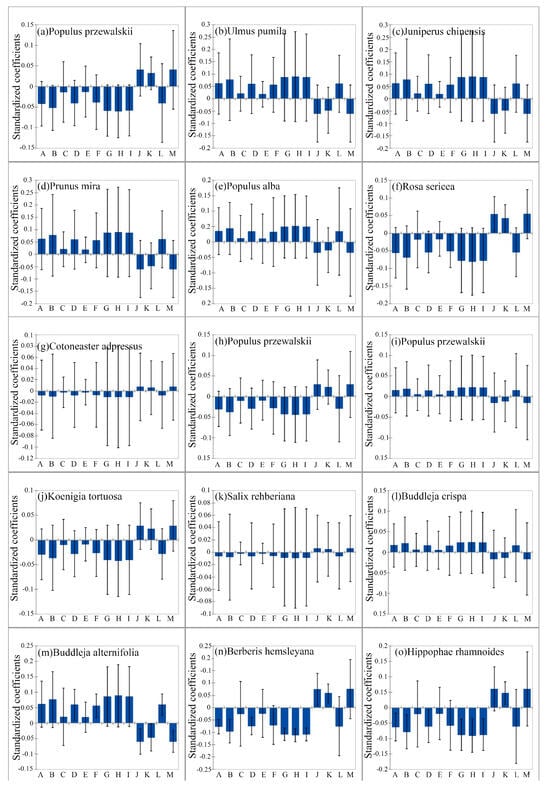

We examined associations between the occurrence of native woody species and environmental factors using univariate logistic regression. Results are summarized in Figure 2 and discussed below. Given our sample size (n = 15 plots), these results should be interpreted as exploratory patterns requiring validation with larger datasets. Specifically, the regression coefficients for soil-species associations may shift in magnitude or significance with larger samples. The identification of rare species associations (those occurring in <3 plots) is particularly tentative and requires validation across additional sites and years.

Figure 2.

Regression analysis of native woody species growth in the northern and southern mountain regions of Lhasa, showing the relationships between environmental physicochemical factors (altitude, soil moisture, salinity, and pH) and tree species occurrence patterns. Note: A: Ammonium nitrogen; B: Available potassium; C: Available phosphate; D: Nitrate nitrogen; E: Soil water content; F: pH; G: Electrical conductivity (EC); H: Total dissolved solids (TDS); I: Salinity (SAL); J: Resistance (Res); K: Altitude; L: Sunny Slope; M: Shaded Slope.

3.3.1. Relationship Between Elevation and Species Occurrence

Among the woody species examined, most showed weak associations with elevation over the range sampled (3650–3850 m). Populus przewalskii Maxim., Ulmus pumila L., and Salix rehderiana C. K. Schneid. all had regression coefficients near zero (β < 0.05, p > 0.40), suggesting that within this elevational range, altitude alone does not strongly predict their occurrence. This indicates these species have broad elevational tolerance within the study area, and that other environmental factors (discussed below) may be more important in determining their distribution.

3.3.2. Soil Moisture Associations

Soil moisture showed varying associations with different woody species. Salix rehderiana showed a positive association with soil moisture (β = 0.18, p = 0.08), suggesting this species occurs more frequently in plots with higher moisture availability. In contrast, Populus przewalskii showed minimal response to moisture variation (β = −0.001, p = 0.96), consistent with its reputation as a drought-tolerant species. Hippophae rhamnoides and Rosa sericea showed intermediate patterns. These differential moisture associations suggest species-specific water requirements should guide planting site selection.

3.3.3. Soil Salinity Associations

Soil salinity showed negative associations with several woody species. Rosa sericea (β = −0.549, p = 0.12) and Hippophae rhamnoides (β = −0.700, p = 0.09) both occurred less frequently in plots with higher salinity, though these trends were marginally significant. This suggests that saline soils may constrain the occurrence of these species, which should be considered when selecting planting sites.

3.3.4. Soil pH Associations

Soil pH associations varied among species. Populus przewalskii showed a slight negative association with pH (β = −0.037, p = 0.35), while Prunus mira Koehne showed a weak positive association (β = 0.034, p = 0.42). Neither relationship reached statistical significance, suggesting that within the pH range observed in our study (pH 7.2–8.5), pH alone may not strongly limit species occurrence, though species-specific pH preferences may exist.

3.3.5. Important Caveats

These regression results represent exploratory correlational patterns based on a limited sample size. They should not be interpreted as demonstrating causation. The associations observed may reflect unmeasured co-varying factors. Experimental studies are needed to validate these patterns and establish causal relationships. Future experimental studies should include: (1) manipulative transplant experiments to test species responses to soil moisture and salinity gradients; (2) greenhouse trials examining growth rates under controlled environmental conditions; (3) expanded field sampling across broader elevational ranges (3600–4200 m) and multiple growing seasons; and (4) long-term monitoring of naturally establishing populations to validate correlational patterns observed here. Nevertheless, these results provide preliminary guidance for species-site matching in restoration plantings.

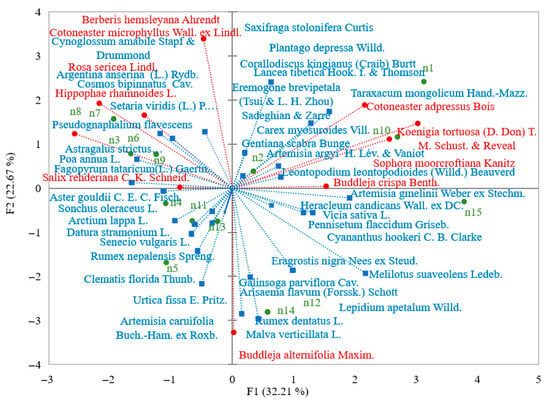

3.4. Identification of Shrub–Herb Configuration Patterns Based on PCA

To identify typical shrub–herb plant configuration patterns, this study conducted Principal Component Analysis (PCA) based on the plant community composition data from the sampling plots (Figure 3). The aim was to reveal the distribution structure of shrubs and herbaceous plants across different plots, and to explore representative shrub–herb combinations, providing data support and configuration guidelines for afforestation and greening in the northern and southern mountain regions of Lhasa. In sampling plots n6, n7, n8, and n9, Rosa sericea Lindl. showed a similar arrangement with Cynoglossum amabile Stapf & Drummond, Argentina anserine, and Pseudognaphalium flavescens (Kitam.) Anderb., with a relatively concentrated distribution. This indicates that these species have a high co-occurrence frequency within the plots, suggesting they can form a stable shrub–herb combination unit. In sampling plots n1 and n10, Cotoneaster adpressus Bois was arranged similarly to Taraxacum mongolicum Hand.-Mazz., Carex myosuroides Vill., and Eremogone brevipetala (Tsui & L. H. Zhou) Sadeghian & Zarre indicating a common distribution trend within the community. Hippophae rhamnoides L. was located near Setaria viridis (L.) P. Beauv. and Cosmos bipinnatus Cav. in the ordination plot, primarily concentrated in plot n7, forming another type of shrub–herb combination. Berberis hemsleyana Ahrendt in sampling plots n7 and n8 showed a similar distribution pattern with Cosmos bipinnatus, Poa annua L., and Setaria viridis (L.) P. Beauv., indicating consistency in the community structure across these plots. Sophora moorcroftiana Kanitz was located near plots n2 and n10, with its distribution closely aligned with that of Leontopodium leontopodioides (Willd.) Beauverd, Gentiana scabra Bunge, and Artemisia argyi H. Lév. & Vaniot. The distribution trend of Salix rehderiana C. K. Schneid. was concentrated in plot n6, where it exhibited similar patterns to Fagopyrum tataricum (L.) Gaertn. and Astragalus strictus Graham, forming another distinct shrub–herb configuration. Buddleja crispa Benth. exhibited a similar distribution pattern to Gentiana scabra and Artemisia argyi, predominantly found in plots n2 and n10. Buddleja alternifolia Maxim. was located in plot n14, with its distribution pattern adjacent to that of Rumex dentatus L. and Malva verticillata L. Cotoneaster microphyllus Wall. ex Lindl. was found near plot n7, with a distribution pattern similar to that of Cynoglossum amabile and Cosmos bipinnatus. Overall, the PCA results delineated several distinct shrub–herb configuration combinations with common distribution characteristics. These findings provide empirical support for species selection and zonal configuration in afforestation and greening efforts in the northern and southern mountain regions of Lhasa.

Figure 3.

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) of Shrub–Herb Plant Configuration Patterns in the Northern and Southern Mountains of Lhasa.

4. Discussion

4.1. Interpretation in Context of Study Limitations

Before discussing our findings, we acknowledge several limitations. The modest sample size (15 plots) constrains statistical robustness and limits generalizability. The correlational design precludes causal inference, and single-season sampling may not capture temporal variability in plant interactions and community dynamics. Additionally, our frequency-based measure does not account for differences in plant biomass or functional impact across species.

However, these limitations are consistent with other field studies exploring shrub–herb interactions in heterogeneous and stress-limited environments. Reviews of shrubland facilitation literature indicate that shrub effects on understory herbs vary with species identity, water availability, and environmental stress gradients, with facilitation often increasing under harsher conditions yet showing context dependence [16]. Empirical work in arid sandy ecosystems has demonstrated that both herb and shrub colonization significantly influence soil microbial activity and nutrient status via cumulative plant litter inputs, although shrubs often contribute relatively more organic inputs [17]. Field research also shows that shrub morphology and functional traits mediate shrub–herb effects, producing both facilitative and competitive outcomes depending on context [18].

Together, these studies suggest that while observational limitations exist in our dataset, the patterns we observed are ecologically plausible and reflect broader evidence that shrub and herb interactions are mediated by environment and species traits. Future work with expanded sampling and multi-season monitoring is needed to extend these exploratory insights.

4.2. Environmental Correlates of Species Distribution

Our regression analyses revealed that elevation had minimal association with species distributions within the range studied, while soil properties showed stronger relationships. This aligns with ecological theory suggesting that within-site heterogeneity in resources often outweighs broad elevational effects over modest gradients [19,20,21]. The positive association between Salix rehderiana occurrence and soil moisture, contrasted with the moisture-independence of Populus przewalskii, highlights species-specific water relations. In restoration contexts, Salix species should be prioritized for mesic microsites, while Populus przewalskii offers greater flexibility for drier sites. The negative associations between salinity and occurrence of several shrub species (Rosa sericea, Hippophae rhamnoides) suggest soil salinity may constrain planting site suitability, consistent with established effects of salinity on plant establishment [22].

4.3. PCA Reveals Effective Shrub–Herb Combinations for Afforestation

Through Principal Component Analysis (PCA) (Figure 3), this study identified several shrub–herb plant combinations with co-occurrence distribution patterns, providing empirical support for regional plant configuration and ecological restoration. For example, Rosa sericea exhibits a high co-occurrence frequency with Cynoglossum amabile, Argentina anserine, and Pseudognaphalium flavescens; Cotoneaster adpressus co-occurs with herbaceous plants such as Taraxacum mongolicum and Carex myosuroides; and Hippophae rhamnoides clusters with Setaria viridis and Cosmos bipinnatus. The existence of these combinations suggests that, under specific environmental conditions, certain shrubs and herbaceous plants can form stable coexistence relationships, thereby enhancing ecosystem stability. Therefore, in the afforestation and greening projects in the northern and southern mountain regions, suitable shrub–herb combinations can be selected to improve vegetation stability and resilience. This pattern is consistent with ecological evidence that shrubs can facilitate herbaceous species by ameliorating microenvironmental stress, improving soil moisture and nutrient conditions, and modifying habitat structure [16,23]. The role of plant litter in enhancing soil microbial activity and nutrient availability further underscores the potential benefit of mixed shrub–herb assemblages for ecosystem functioning in arid landscapes [17].

However, several plant associations were identified from single plots only, which limits confidence in their generalizability. Broader sampling is needed to validate the stability and ecological significance of these associations.

4.4. Ecological Implications for Restoration

Our findings have several practical implications for ecological restoration in the Lhasa mountain region:

- (1)

- Slope aspect-based species selection: The higher diversity on shady slopes vs. sunny slopes indicates that species pools should differ by aspect. Shady slopes can accommodate more diverse plantings, while sunny slopes should focus on drought-tolerant shrub combinations.

- (2)

- Target shrub–herb assemblages: The PCA-identified associations (e.g., Rosa sericea with Cynoglossum amabile and Argentina anserina; Cotoneaster adpressus with Taraxacum mongolicum) represent naturally co-occurring combinations that may facilitate establishment through positive interactions. Planting these assemblages together may improve establishment success compared to monocultures.

- (3)

- Soil moisture management: Given the strong moisture associations observed, irrigation or water harvesting techniques may be critical for establishment, particularly on sunny slopes and for moisture-dependent species like Salix rehderiana.

- (4)

- Site-specific approaches: The environmental heterogeneity revealed by our study indicates that a one-size-fits-all restoration approach will be ineffective. Species selection and planting strategies should be tailored to slope aspect, soil moisture conditions, and salinity levels at each site.

4.5. Challenges and Future Potential in the Establishment of Native Woody Species for Afforestation

According to the field survey, the soil layers in the northern and southern mountain regions of Lhasa are generally shallow, with severe soil compaction, and widespread distribution of rocky layers. These factors present significant challenges to plant growth. Furthermore, no native woody species grow in the northern and southern mountains; shrubs are widely distributed, with some species growing vigorously to a height of 3–4 m. Therefore, future greening projects should particularly focus on the cultivation of shrubs and the rational configuration of shrub–herb combinations to enhance the effectiveness of afforestation. Currently, some nurseries have made progress in research on the planting and propagation of native woody species in Lhasa, such as Berberis lhasaensis and Pilea involucrata. However, the application of these species in the greening projects of the northern and southern mountains still requires further promotion.

4.6. Limitations and Future Directions

Our findings are limited by modest sample size (n = 15 plots) and single-season sampling. These results should be considered exploratory and hypothesis-generating. Future research should: (1) expand sampling to validate patterns across broader spatial and temporal scales, (2) conduct experimental plantings to test identified shrub–herb combinations, and (3) implement long-term monitoring to assess restoration outcomes.

Despite these limitations, this study provides valuable baseline data for ecological restoration in this understudied high-altitude region and offers preliminary, science-based guidance for native species selection and planting configuration strategies in the northern and southern mountain regions of Lhasa.

5. Conclusions

This exploratory study examined shrub–herb plant configuration patterns in the northern and southern mountain regions of Lhasa and their associations with slope aspect and environmental factors. Our key findings include:

- (1)

- Slope aspect strongly influences plant communities: Shady slopes supported significantly higher species diversity (Shannon index: 3.62 ± 0.24) and evenness compared to sunny slopes (Shannon index: 3.14 ± 0.31), reflecting differences in moisture availability and microclimate.

- (2)

- Environmental associations: Within the elevational range studied, soil properties (moisture, salinity, pH) showed stronger associations with species occurrence patterns than elevation. However, given our limited sample size, these represent preliminary patterns requiring validation.

- (3)

- Shrub–herb associations: PCA revealed several recurring plant combinations, including Rosa sericea with Cynoglossum amabile, Cotoneaster adpressus with Taraxacum mongolicum, and Hippophae rhamnoides with Setaria viridis. These assemblages may represent promising candidates for restoration plantings.

- (4)

- Native shrubs dominate: Field observations confirmed that native shrub species, rather than trees, form the natural woody vegetation, suggesting restoration efforts should prioritize shrub establishment.

We recommend that future restoration initiatives: (1) adopt an adaptive management framework that monitors establishment success and adjusts species selection accordingly; and (2) prioritize areas where restoration will have the greatest ecological impact while considering socioeconomic factors. Finally, we recommend that restored areas be designated for long-term protection and monitoring, allowing vegetation communities to mature and develop naturally over multi-decadal timescales. Such protection would maximize ecological benefits and provide opportunities for adaptive management based on observed outcomes.

Author Contributions

Read, N.T. and X.L.; software, N.T., X.L., S.H. and J.W.; validation, N.T. and X.L.; writing—original draft preparation, N.T., X.L. and R.L.; writing—review and editing, N.T., X.L., J.W., G.Q., S.H., Y.Z. and R.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the High-Level Talent Training Program for Postgraduates of Tibet University (Grant No. 2022-GSP-B005), the Key R&D Project of the Science and Technology Program of Tibet Autonomous Region (Grant Nos. XZ202301ZY0006G, XZ202501ZY0091), the Nagchu City Science and Technology Program Key R&D Project (Grant No. NQKJ-2023-15), the Open Project of North Minzu University Ningxia Key Laboratory for the Development and Application of Microbial Resources in Extreme Environments (Grant No. NXTS2401), the High-Level Talent Recruitment Program of Tibet University (Grant No. xzdxdr202407), the University-Level Innovation and Entrepreneurship Training Program for College Students of Tibet University (Project No. 2025XCX095), and the Open Project of the Key Laboratory of Biodiversity and Environment on the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau, Ministry of Education (Project No. KLBE2025004). Additionally, this work is supported by the West Tibet Autonomous Region Science and Technology Program Key R&D and Transformation Project: “Research on Optimizing the Precision Afforestation and Dynamic Irrigation Technology System of Lhasa’s North and South Mountains Based on GIS Remote Sensing” (currently without project number).

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their gratitude for the use of XLSTAT (19.2.2) in generating the word cloud featured in this study. Furthermore, the process flow diagrams were meticulously crafted using Adobe Photoshop. The authors assume full responsibility for the accuracy, integrity, and content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| pH | Soil pH |

| cond | Conductivity |

| TDS | Total Dissolved Solids |

| SAL | Salinity |

| RESX | Resistance |

| PCA | Principal Component Analysis |

| XLSTAT | Software for statistical analysis |

References

- Myers, N.; Mittermeier, R.A.; Mittermeier, C.G.; da Fonseca, G.A.B.; Kent, J. Biodiversity hotspots for conservation priorities. Nature 2000, 403, 853–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhu, W.; Jiang, S.; Li, Z. Evaluation of the suitaiblity of afforestation tree species in the northern and southern mountains of Lhasa using analytic hierarchy process. J. Northeast For. Univ. 2025, 53, 38–57. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, B.; Yao, X. Influencing factors and countermeasures for afforestation survival rate in the north and south mountains greening project of Lhasa. Sichuan Agric. Sci. Technol. 2025, 1, 173–176. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, H.; Zhu, Z.; Yao, H.; Ke, Y.; Pu, B. Tibet plateau semi-arid region seabuckthorn field seedling raising technique. Tibet Agric. Sci. Technol. 2012, 34, 24–26. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, S. Summary of introduction, seedling cultivation and afforestation trials of Cupressus torulosa in Tibet. Hunan For. Sci. Technol. 2001, 28, 44–46. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, J. Cultivation techniques of Cupressus torulosa in Tibet. Pract. For. Technol. 2014, 4, 60–61. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Z.; Ke, Y.; Ge, S.; Cui, Z.; Pu, B.; Zuo, L. The main afforestation tree species in tibet—The technology research about Poplar in vitro rapid propagation. Tibet Agric. Sci. Technol. 2012, 34, 23–28. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, D.; Fang, J.; Quan, H.; Guo, Q.; Zhao, K. A study on drought resistance of three cypress species in the semi-arid region of Tibet. Resour. Sci. 2010, 32, 1601–1607. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y. Study on Drought Resistant Forestation Technology of Lhasa Semi-Arid Valley and Overflow Land. Master’s Thesis, Xizang University, Lhasa, China, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, Y. Tree selection and typical afforestation model of south-north mountains in Lhasa. J. Plateau Agric. 2023, 7, 486–491. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, Y.; Pu, B. Classification of stand type and evaluation on forest suitability in Lhasa South-North Mountains. For. Constr. 2023, 41, 26–28. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Li, X.; Dong, S.; Zhang, J.; La, Q.; Cao, P. Characteristics of bacterial diversity changes in the watershed of the lower Lhasa River. J. Glaciol. Geocryol. 2025, 47, 537–548. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Zhou, J.; Hu, J.; Liu, S.; Weng, S.; Fang, Q.; Pu, B.; Yang, L. Diversity of birds in Lhasa in autumn. Tibet Sci. Technol. 2024, 46, 3–11. [Google Scholar]

- Du, J.; Jian, J.; Yu, Y.; Yang, B.; Lhak, P. Climatic change features of rainfall in Lhasa form1952 to 2005. Arid Land Geogr. 2008, 31, 397–402. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, L.; Huang, Z.; Jie, C.; Zang, J. Study on the diversity of spider community under different afforestation patterns in the northern and southern mountains of Lhasa. Plateau Sci. Res. 2024, 8, 55–64. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, G.-S.; Luo, T.-X.; Liang, E.-Y.; Zhang, L. Advances in the study of shrubland facilitation on herbs in arid and semi-arid regions. Chin. J. Plant Ecol. 2022, 46, 1321–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wang, J.; Morreale, S.J.; Schneider, R.L.; Li, Z.; Wu, G.-L. Contributions of plant litter to soil microbial activity improvement and soil nutrient enhancement along with herb and shrub colonization expansions in an arid sandy land. Catena 2023, 217, 107098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, X.; Wu, X.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, A.; Duan, L.; Zhou, J.; Zhan, Z.; Qi, W. Shrub effect on grassland community assembly depends on plant functional traits and shrub morphology. Oecologia 2025, 207, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ordoñez, J.C.; van Bodegom, P.M.; Witte, J.P.; Bartholomeus, R.P.; van Hal, J.R.; Aerts, R. Plant strategies in relation to resource supply in mesic to wet environments: Does theory mirror nature? Am. Nat. 2010, 175, 225–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCluney, K.E.; Belnap, J.; Collins, S.L.; González, A.L.; Hagen, E.M.; Holland, J.N.; Kotler, B.P.; Maestre, F.T.; Smith, S.D.; Wolf, B.O. Shifting species interactions in terrestrial dryland ecosystems under altered water availability and climate change. Biol. Rev. Camb. Philos. Soc. 2012, 87, 563–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Yu, B.; Sun, Z.; He, P.; Dong, Y.; Yang, H. Spatial variability and driving factors of soil pH in the desert grasslands of northern Xinjiang. Environ. Res. 2025, 276, 121489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.; Sarker, S.K.; Friess, D.A.; Kamruzzaman, M.; Jacobs, M.; Islam, M.A.; Alam, M.A.; Suvo, M.J.; Sani, M.N.; Dey, T.; et al. Salinity reduces site quality and mangrove forest functions. From monitoring to understanding. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 853, 158662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, H.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, J.; Guo, Y.; Liu, H.; Li, Y.; Gao, S. Aridity and soil properties drive the shrub–herb interactions along environmental gradients. Agronomy 2024, 14, 2588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.