Abstract

Post-industrial heaps are a major environmental problem. They require remediation and reclamation, in which natural succession plays a key role in ecosystem development. This study aimed to assess the effect of heaps formed from materials of different origins on the nutrient content of silver birch (Betula pendula Roth), a pioneer species in this process. We analyzed nutrient contents in biomass fractions (fine and coarse roots, stemwood, bark, coarse and fine branches, leaves) and in soils sampled from 0 to 10, 10 to 20, 20 to 40, and 40 to 80 cm. Basic soil properties and the contents of N, P, K, Ca, Mg, S, Fe, Mn, Cu, and Zn in both soil and biomass were determined. The soils were poor in total organic carbon and differed in pH, texture, and nutrient status. Leaves and roots contained the highest nutrient contents, whereas stemwood contained the lowest. Statistical analyses revealed significant differences in all studied elements between heaps. Among macronutrients, N, P, and Mg were most abundant, followed by K, Ca, and S. Among micronutrients, Mn dominated, followed by Fe, Zn, and Cu. Findings underscore that silver birch growing on contaminated post-industrial heaps cannot be considered a hyperaccumulator of trace elements.

1. Introduction

Industrialization has accelerated economic development, but it has also intensified land degradation and contamination through large-scale extraction and waste deposition, affecting soils, water, and biota. Waste management is a multi-dimensional system involving prevention, recovery, recycling, and regulated disposal; however, in post-industrial landscapes, legacy surface deposits remain an important driver of soil development and soil–plant interactions, and thus constitute a key context for interpreting vegetation establishment and element cycling. In Poland, mining and related processes generate the largest category of industrial waste [1]. In 2022, national official statistical data indicate that mining and quarrying accounted for 53.3% of all waste generation, while industrial manufacturing contributed 18.6% [2]. By 2022, the accumulated mass of waste from mining and quarrying amounted to 850,051 thousand tones, with manufacturing producing a further 285,859 thousand tones. Phosphogypsum deposits are a representative example, commonly exhibiting high Ca–S pools and site-specific pH regimes that may strongly modify element bioavailability and plant uptake [3].

The deposition of waste on the land surface leads to the formation of heaps with specific habitat conditions, such as low soil fertility, extremely low or high pH [4], poor soil structure, and limited water availability for plants [5]. Even long after industrial activities have ceased, such deposits can remain a potential source of pollution, including toxicity from trace elements [6]. These constraints favour the establishment of characteristic plant assemblages [7] and make spontaneous succession an important process in ecosystem recovery. Silver birch (Betula pendula Roth) is a common pioneer tree species in temperate regions, known for its ability to colonize barren land, including post-fire and post-industrial areas [8]. Its tolerance is supported by multiple traits reported in the literature, such as relatively high root biomass allocation, elevated phenolic compounds, differences in ectomycorrhizal diversity [9], efficient non-photochemical quenching [5], and variability in leaf morphology [5,10]. Accordingly, silver birch has been discussed in different contexts, including air-quality improvement [11], accumulation of selected trace elements, and biomonitoring/bioindication depending on the element and study objective [12,13,14,15,16,17]. For example, Rosselli et al. (2003) [18] reported a relatively high Zn bioconcentration factor in birch compared with several other tree species, whereas Lewis et al. (2015) [12] concluded that birch does not match specialized hyperaccumulators in the phytoremediation of trace-element-contaminated sites. Field data from a Zn–Pb industrial region also showed elevated trace-element concentrations in unwashed birch leaves [19], highlighting that measured values may reflect both uptake and surface contamination.

Abiotic stresses such as pollution, extreme pH, low soil fertility, and soil organic matter content can negatively affect plant growth [20,21] and are directly related to nutrient uptake and internal allocation. Silver birch biomass is often relatively abundant in macronutrients (N, P, K, Ca, Mg) [22], and comparative evidence indicates higher nutrient concentrations in birch than in Norway spruce (Picea abies) and Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris) [23]; nevertheless, reported element pools depend strongly on plant- and soil-related factors, including stand age and site conditions [24,25,26,27]. Although the elemental content of silver birch has been partially recognized, quantitative evidence on how various technogenic parent materials and soil conditions translate into organ-specific nutrient and trace-element patterns in naturally colonizing birch stands remains limited. Therefore, this study evaluates macro- and micronutrient accumulation (N, P, K, Ca, Mg, S, Fe, Mn, Cu, Zn) across seven biomass fractions (fine roots, coarse roots, stemwood, bark, coarse branches, fine branches, leaves) and the associated soils in three strongly contrasting Technosols developed on post-industrial waste heaps. We hypothesized that soil properties controlling element availability drive differences in element accumulation among birch organs, and we further assessed whether birch behaviour on these substrates is consistent with the phytoextraction or, rather, phytostabilisation of the studied trace elements.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Sites

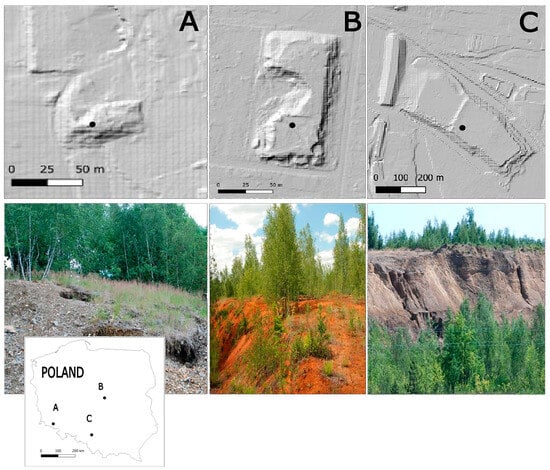

The study was performed at three disposal sites where industrial wastes of various origins were deposited. Their locations are shown in Figure 1. Stands overgrown by the spontaneous succession of silver birch were distinguished within these areas. The characteristics of the studied stands are presented in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Locations of the studied stands: (A) mine waste heap in Miedzianka; (B) industrial waste disposal site in Łowicz; and (C) mine-tailings disposal site in Bytom.

2.1.1. Historical Copper Mine Waste Heap

The studied copper mine (CM stand) waste heap was located in Miedzianka village in the Western Sudetes, southern Poland. In this area, the mining activities and extraction of polymetallic ores—particularly Cu, arsenic (As), and silver (Ag)—started in the early 14th century and ended in the 1950s [28]. During our field study (2022), the mine waste heap was covered by a sparse birch forest. In the period 1961–2010, the mean annual temperature from the nearest station (Karpacz) was 6.9 °C, with a mean annual sum of precipitation of 1066 mm. July was the warmest month, while January was the coldest. July was also noted as the month with the highest sum of precipitation, while February was the lowest.

2.1.2. Industrial Waste Disposal Site from an Abandoned Chemical Plant

The industrial waste disposal site (FW stand) was in the town of Łowicz in the Central Mazovian Lowland, which belongs to the central Polish climatic region [29]. For the period 1971–2000, the maximum temperatures exceeded 27 °C, while the minimum temperatures were below −8 °C. The coldest month is January, with mean temperatures of −2 to −1 °C, while the warmest month is July, with temperatures exceeding 19 °C.

The disposal site was developed between 1896 and 1914 as a result of the activity of a chemical plant that produced phosphate fertilizers. The plant primarily focused on the production of superphosphate from mineral phosphates and sulfuric acid. Therefore, it was assumed that the material deposited at the disposal site was a phosphogypsum containing impurities from the chemical processes used in the plant, including Fe oxides (most likely coming from the sulfuric acid, which was not purified well) and carbonates (which were most likely originally associated with the phosphate rocks). During our field studies (2022), the disposal site was covered by sparse birch thickets.

2.1.3. Mine-Tailings Disposal Site of a Former Lead and Zinc Mine

The mine-tailings (MT stand) disposal site was developed in Bytom city, in the Silesian Upland, southern Poland. Air masses flow into the area of this macroregion from different directions, also including, partly, from the south through the Moravian Gate. These include the polar-marine, polar-continental, Arctic, and tropical masses. From the 1930s to 1981, the “Marchlewski” Zinc and Lead Ore Mine, part of the “Orzeł Biały” Mining and Smelting Plant, excavated zinc and lead ores. Most of Bytom is built on Pleistocene glacial till, its weathering products, glacial sands, and gravels, as well as gravelly and outwash sands. The ores occur in Middle Triassic dolomites. During processing, they were subjected to mechanical grinding and then flotation to concentrate the ore minerals. The post-flotation waste was transported as a slurry to the settling ponds during the years 1930–1960 [30]. During our field studies (2022), the disposal site was covered by sparse birch thickets and meadow plant communities. The mean annual temperature of this area was 8.1 °C, with January being the coldest and July the warmest month. The annual precipitation was 723 mm, with the highest sum of precipitation recorded in July and the lowest in February.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the studied silver birch stands.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the studied silver birch stands.

| Stand Name | Coordinates | Soil Reference Group (WRB, 2022) [31] | DBH (cm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| CM | 50.875783 N, 15.939619 E | Spolic Technosol (Loamic, Endoeutric, Ochric, Hyperartefactic, Technoskeletic, Toxic) | 30.6 ± 6.2 |

| FW | 52.126372 N, 19.950969 E | Spolic Technosol (Eutric, Dolomitic, Fluvic, Hyperartefactic, Ochric, Toxic) | 31.6 ± 5.7 |

| MT | 50.338417 N, 18.942677 E | Spolic Technosol (Calcic, Fluvic, Gypsiric, Ochric, Hyperartefactic, Protosalic, Toxic) | 38.3 ± 6.1 |

Note: CM—stand on historical copper mine waste heap; FW—stand on industrial waste (phosphogypsum) disposal site of abandoned chemical plant; MT—stand on mine-tailings disposal site of former Pb and Zn mine; WRB—World Reference Base (International Union of Soil Sciences Working Group, 2022) [31]; and DBH—diameter at breast height.

2.2. Soil and Biomass Sampling

Soil and biomass samples were collected in July 2022. At each study stand, 10 locations were distinguished, represented by one average-sized tree without visible symptoms of dieback, from which the following biomass fractions were taken (approx. 100 g of each sample): second-order roots (RII), first-order roots (RI), stemwood (S), stem bark (B), first-order branches (BrI), second-order branches (BrII), and leaves (L). The samples of stemwood and bark were taken from breast height, while the leaves were taken from the central part of the crown. Under each tree (approximately 1 m from the stem), soil samples in total mass of approx. 1 kg per sample were collected using a 3 cm diameter corer from 0 to 10, 10 to 20, 20 to 40, and 40 to 80 cm.

2.3. Laboratory Analyses

The soil samples were dried at room temperature and then passed through a 2 mm sieve. Their particle size distribution was determined using the mixed pipette and sieve methods, and the Polish Soil Science Society’s classification of textural fractions and groups [32] was then applied. The soil pH was determined using the potentiometric method in a suspension with water at a soil/water ratio of 1:2.5 (pH-metre SevenDirect SD23 equipped with an InLab ExpertPro ISM electrode, Mettler-Toledo AG, Greifensee, Switzerland). The total organic carbon (TOC) content was calculated as the difference between the total carbon (TC) measured by dry combustion (Vario MACRO cube, Elementar Analysensysteme GmbH, Langenselbold, Germany) and inorganic carbon (IC) determined by the Scheibler volumetric method. The total N and total S contents were also measured by dry combustion, while the P, K, Ca, Mg, Fe, Mn, Cu, and Zn contents were determined by inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectrometry (ICP-OES, Avio 200, PerkinElmer, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA), prior to microwave (ETHOS UP, Milestone Srl, Sorisole, Italy) digestion in aqua regia.

Root samples were carefully cleaned to remove adhering soil particles. Roots were gently rinsed with deionized water and manually cleaned to minimize residual soil without damaging tissues. Aboveground organs (stemwood, bark, branches, leaves) were not washed. Any visible debris was removed manually. No chemical washing was applied. Cleaned samples were then dried at 65 °C and milled into powder. The TOC, N, and S contents were determined by dry combustion, and the P, K, Ca, Mg, Fe, Mn, Cu, and Zn contents were determined by ICP-OES, after microwave digestion in 65% nitric acid.

All analyses, except for the particle size distribution and pH, were performed in duplicate, which represent analytical replicates used for quality control and method precision. For each sample, duplicate results were averaged to obtain a single value that was used in all subsequent statistical analyses. Only pure per-analysis reagents and certified reference materials were used for instrument calibration and quality control.

2.4. Calculations and Statistical Analyses

Bioaccumulation factors (BAF’s) were calculated to relate element contents in birch biomass fraction to the corresponding soil contents at each stand, as a weighted mean across 0–80 cm soil layer, calculated using the following formula:

where Ci is the content of element in soil layer i; di is the thickness of soil layer i; and n is the number of layers. For each element and biomass fraction, BAF was computed as

The statistical analysis of the results included calculating the mean contents of the biomass and mean and/or weighted mean soil samples characteristics, as well as their standard deviations (SDs). The statistical significance of the differences between the mean values was assessed using the Kruskal–Wallis test followed by Dunn’s test. The whole dataset was also processed using Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to determine the stand variability and relationships between variables, using Statistica (v.13.3).

3. Results

3.1. Basic Characteristics of the Soils

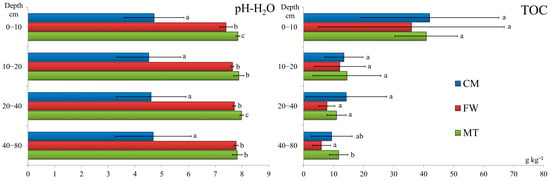

The particle size distributions showed considerable variability between the study sites in terms of texture (Table 2). The contribution of clay to the soils of the FW stand was relatively high (up to 20.9%) compared to the other stands (up to 6.5%). The soil reaction was acidic (CM stand) or alkaline (FW and MT stands) and vertically homogeneous in each stand, with mean pH values of 4.6 ± 1.3, 7.7 ± 0.1, and 7.9 ± 0.1 for the CM, FW, and MT stands, respectively (in the 0–80 cm layer) (Figure 2). All stands presented low SOM contents, particularly in the deeper layers (>10 cm), where the TOC content did not exceed 14.2 g kg−1. The highest amounts of TOC were found in the 0–10 cm topsoil where the SOM was accumulated (Figure 2), and significant differences between stands were mostly not observed (Supplementary Materials).

Table 2.

Particle size distribution of the studied soils.

Figure 2.

pH and TOC content in the studied soils. Different lowercase letters indicate statistically significant differences between stands at a significance level of p < 0.05 based on the Kruskal–Wallis test followed by Dunn’s test. Note: CM—stand on historical copper mine waste heap; FW—stand on industrial waste (phosphogypsum) disposal site of abandoned chemical plant; MT—stand on mine-tailings disposal site of former Pb and Zn mine.

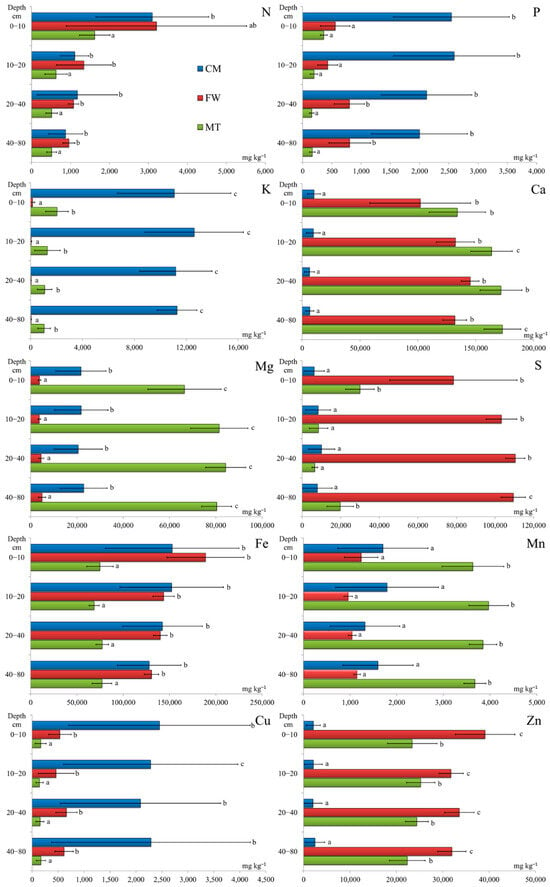

3.2. Nutrient Content of the Soils

The weighted mean nutrient contents in the soils (0–80 cm layer) of the investigated stands are presented in the Supplementary Materials. Based on these results, the elements could be arranged in the following orders: Fe > Mg > K > S > Ca > Cu > Zn > P > Mn > N in the CM stand, Fe > Ca > S > Zn > Mg > N > Mn > P > Cu > K in the FW stand, and Ca > Mg > Fe > Zn > S > Mn > K > N > P > Cu in the MT stand. The soils showed different vertical patterns of nutrient distributions between the stands, reflecting their associations with the SOM or the mineral phase of the soil. In most cases, significant differences between the studied stands were found (Supplementary Materials and Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Mean elemental contents (mg kg−1) and ± SD in soils from depths of 0–10, 10–20, 20–40, and 40–80 cm. Different lowercase letters indicate statistically significant differences between stands at a significance level of p < 0.05 based on the Kruskal–Wallis test followed by Dunn’s test. Note: CM—stand on historical copper mine waste heap; FW—stand on industrial waste (phosphogypsum) disposal site of abandoned chemical plant; MT—stand on mine-tailings disposal site of former Pb and Zn mine.

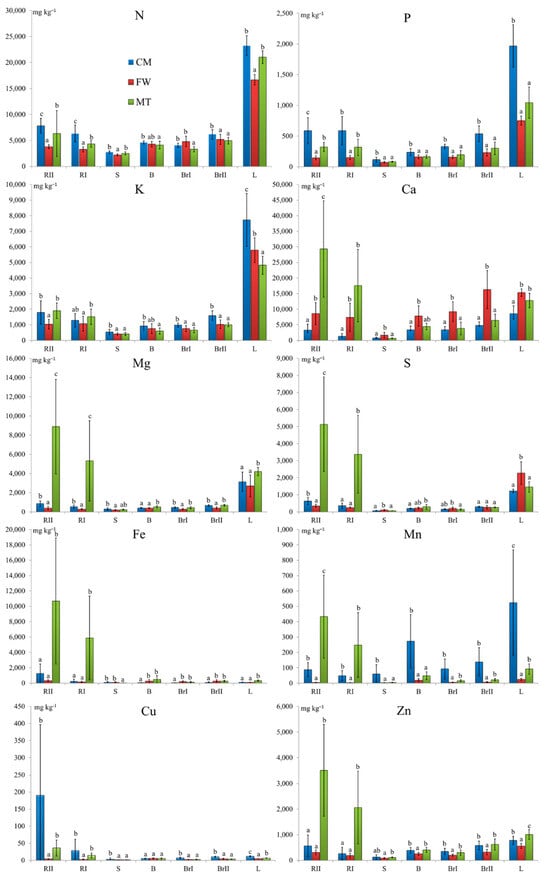

3.3. Nutrient Content in Birch Biomass

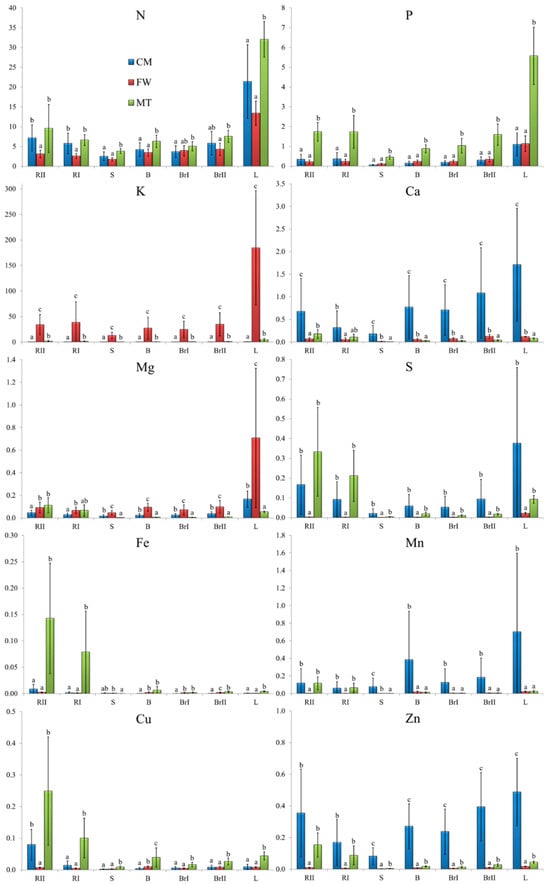

The nutrient composition and distribution of the silver birch biomass collected from the industrial waste disposal sites demonstrated several significant differences (Figure 4). The birch trees from the CM stand contained significantly more P, K, and Cu in most of the biomass fractions, while Mg was accumulated in higher amounts by the birches from the MT stand. The distribution patterns of the contents of the nutrients in the birch biomass varied depending on the type of element and the stand. Typically, the leaves had the highest nutrient contents (N, P, K, Mg, S, Mn, and Zn). In the MT stand, the highest elemental accumulation was also observed in the second-order roots (Ca, Fe, and Cu). Among the studied biomass fractions, the stemwood had the lowest accumulation of all elements. In terms of the mean contents of the biomass fractions, among the macronutrients, the highest values were for N (2199.7–23,230.0 mg kg−1), while the lowest were for P (71.6–1969.0 mg kg−1). Among the micronutrients, the highest contents were noted for Zn (86.6–1008.5 mg kg−1) and the lowest for Cu (1.2–190.3 mg kg−1).

Figure 4.

Mean elemental contents (mg kg−1) and ± SD in silver birch (Betula pendula Roth) biomass. Different lowercase letters indicate statistically significant differences between stands at a significance level of p < 0.05 based on the Kruskal–Wallis test followed by Dunn’s test. Note: CM—stand on historical copper mine waste heap; FW—stand on industrial waste (phosphogypsum) disposal site of abandoned chemical plant; MT—stand on mine-tailings disposal site of former Pb and Zn mine; RII—second-order roots, RI—first-order roots, S—stemwood, B—bark at a height ≈ 130 cm, BrI—first-order branches, BrII—second-order branches, and L—leaves.

3.4. Bioaccumulation Factors

The values of BAF differed strongly among stands and biomass fractions (Figure 5). Across all stands, N showed the highest BAFs (CM: 2.5–21.4; FW: 1.8–13.4; MT: 3.83–32.03), with the highest values in leaves, indicating preferential allocation/retention of N in photosynthetically active tissues. In contrast, micronutrients displayed low BAF values in all organs, suggesting limited enrichment relative to soil contents (Fe: 0.00–0.14, Mn: 0.00–0.70, Cu: 0.00–0.25, Zn: 0.00–0.50). Among macronutrients, the FW stand was distinctive due to exceptionally high BAF of K across all fractions (12.9–184.6), with the strongest enrichment in leaves (184.6), whereas other macronutrients at FW remained low (e.g., Ca: 0.00–0.10, Mg: 0.00–0.70, P: 0.10–1.10). At CM and MT stands, BAF patterns were more balanced: P and K showed moderate enrichment (CM: P 0.10–1.10, K 0.00–0.70; MT: P 0.45–5.57, K 0.39–4.67, with maxima in leaves: P 5.57, K 4.67), while Ca and Mg tended to remain below 1 in most organs (CM: Ca 0.20–1.70, Mg 0.00–0.20; MT: Ca 0.00–0.18, Mg 0.00–0.11). Overall, BAF-based comparisons indicate that stand-specific soil conditions translated into organ-dependent differences in relative uptake.

Figure 5.

Mean ± SD of the bioaccumulation factors (BF’s) in silver birch (Betula pendula Roth) biomass fractions. Different lowercase letters indicate statistically significant differences between stands at a significance level of p < 0.05 based on the Kruskal–Wallis test followed by Dunn’s test. Note: CM—stand on historical copper mine waste heap; FW—stand on industrial waste (phosphogypsum) disposal site of abandoned chemical plant; MT—stand on mine-tailings disposal site of former Pb and Zn mine; RII—second-order roots, RI—first-order roots, S—stemwood, B—bark at a height ≈ 130 cm, BrI—first-order branches, BrII—second-order branches, and L—leaves.

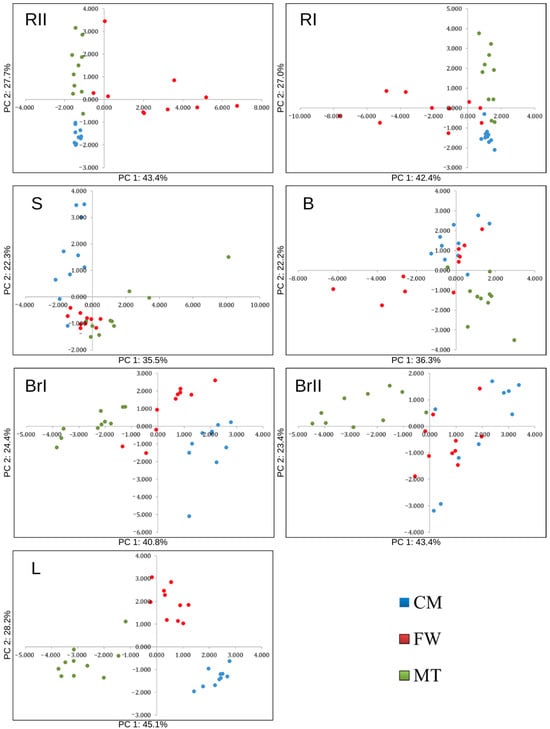

3.5. Principal Component Analysis

The results from a projection of the cases on the plane of factors (Figure 6) show a clear separation of stands within each biomass fraction. Through the differences determined between the stands, the effect of the anthropogenic factor and its impact on the linkages in the plant–soil system were highlighted.

Figure 6.

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) for the individual silver birch (Betula pendula Roth) biomass fractions (projection of cases on the plan of factors). Note: CM—stand on historical copper mine waste heap; FW—stand on industrial waste (phosphogypsum) disposal site of abandoned chemical plant; MT—stand on mine-tailings disposal site of former Pb and Zn mine; RII—second-order roots, RI—first-order roots, S—stemwood, B—bark at a height ≈ 130 cm, BrI—first-order branches, BrII—second-order branches, and L—leaves.

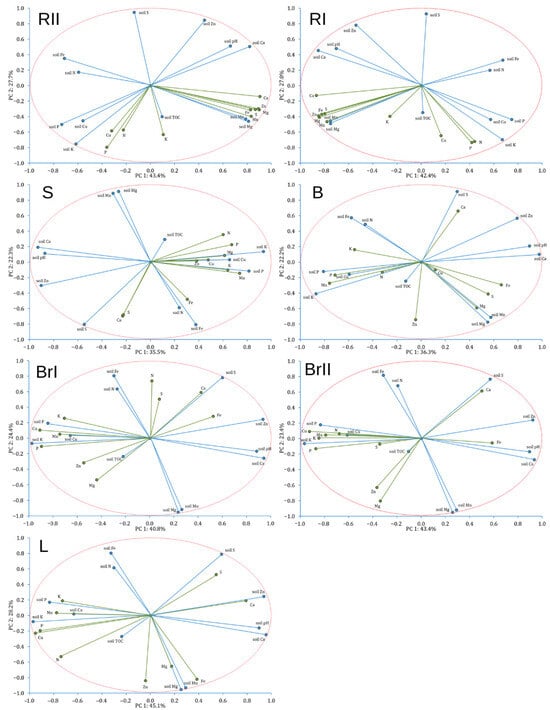

The analysis revealed stand-specific clustering for all biomass fractions, confirming that differences in soil properties translate into distinct element composition of birch organs. The PCA (Figure 7) showed that relationships between soil chemistry and element contents in birch organs were element-specific. Across biomass fractions, contents of P, K, Ca, Mg, and Cu generally increased with increasing soil contents of the same elements, indicating a coherent soil–plant linkage for these nutrients. In contrast, soil–plant correlations were weak or negative for Fe and Zn, suggesting that total soil contents were not reliable predictors of their contents in birch biomass fractions under the studied Technosols. For Mn, the soil–plant coupling differed by organ: it was positive in roots, whereas in aboveground fractions the relationship tended to be negative, pointing to organ-specific regulation and/or pH-controlled availability.

Figure 7.

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) of individual silver birch (Betula pendula Roth) biomass fractions and soil characteristics. Note: green lines—biomass components/properties, blue lines—soil components/properties, RII—second-order roots, RI—first-order roots, S—stemwood, B—bark at a height ≈130 cm, BrI—first-order branches, BrII—second-order branches, and L—leaves.

Soil pH emerged as an important co-factor explaining biomass composition. Increasing pH was consistently associated with higher Ca contents in biomass, while P contents (and frequently N) decreased with increasing pH across fractions. Moreover, Mn contents in aboveground tissues decreased strongly with increasing pH, and Cu also tended to decline with increasing pH, particularly in branches and leaves. Overall, the correlations highlight that pH-dependent mobility and organ-specific controls modulate soil–plant transfer.

Soil TOC showed generally weak associations with element contents in birch biomass across fractions, indicating that variability in biomass chemistry was not driven by organic carbon. Where relationships occurred, TOC tended to be positively related to biomass macronutrients (especially N and P in some fractions), but the overall pattern was not consistent among organs.

4. Discussion

The major feature of Technosols is their anthropogenic origin and, therefore, their large variability in terms of various properties [33,34]. Consequently, depending on the origin of the parent material, Technosols can represent different levels of trophic status with strongly diversified pools of bioavailable nutrients and potentially toxic elements. Hence, a strong variability in the chemical composition of the plants overgrowing such locations should be expected [35,36]. Our results from the soils showed high variability in this respect (Figure 2 and Figure 3). Therefore, considering the heterogeneous nature of the soils, the PCA analyses results (Figure 6 and Figure 7) were expected in that they clearly show a dissimilarity in the nutritional status of the silver birches between the studied stands and its relationships with soil characteristics.

Soils developed on industrial waste disposal sites are often contaminated with trace elements [37,38,39], as also observed in this study. Based on Polish legal regulations [40], the soils of the CM stand exceeded the permitted Cu content, which is typical of heaps formed as a result of mining ores of this metal [41]. This high Cu content was well reflected in the biomass of the silver birch, which showed higher Cu contents when compared to the birches overgrowing the other heaps in this study, but also compared to those investigated by other authors, including in areas undisturbed by industry [24,42,43,44,45] and areas affected by industrial activities [5,19,46,47,48,49]. All the investigated heaps can be considered to be contaminated with Zn, but this is particularly true of the industrial waste from the chemical plant disposal site (FW stand). As reported by Rajković et al. (2000) [50], such waste can contain significant amounts of several trace elements, including Zn. The Cu-ore rocks from the Miedzianka area (CM stand) contain metal-bearing minerals, such as chalcopyrite (CuFeS2), chalcocite (Cu2S), and sphalerite (ZnS), and are sources of contamination of such heaps with trace elements [28]. A previous study of the characteristics of Zn–Pb tailing ponds from close to the heap of the MT stand reported extremely high total Zn contents, exceeding 8% [30]. Silver birch has been identified by some authors as a species with a high potential for the effective accumulation of Zn, offering the possibility of using it for phytoremediation [16]. Kosiorek et al. (2016) [51], investigating the trace-element content of various tree species growing in urban environments, found that the Zn content in the leaves of silver birch was higher than in other trees. However, as explained by Baker and Brooks (1989) [52], the threshold Zn content for including a plant species in a group of hyperaccumulators should be >1% of the dry mass of the plant shoots, while for Cu, it should be >0.1%. In our study, the silver birch did not meet these criteria and therefore cannot be considered to be a hyperaccumulator of either Zn or Cu. However, when compared to the literature, the birch trees overgrowing the investigated heaps (except for those in the FW stand) contained significantly higher amounts of Zn in comparison to non-contaminated areas [24,42,43,44,45]. Higher contents have also been noted in birch trees found on black-coal dumps [46], coal waste substrates [49], an area of Zn–Pb ores [53], and on post-coal and post-smelter heaps [5]. The relatively low Zn accumulation in the FW stand, despite its high amounts in the soil substrate, is probably related to the properties of the phosphogypsum. As proven by Mahmoud and Abd El-Kader (2015) [54], phosphogypsum can immobilize some heavy metals, including Zn, and therefore reduce their availability to plants.

The Mn availability to plants is mainly controlled by the soil pH [55]. In acidic soils, birch trees can accumulate this element well [56]. This is consistent with our observations. There were significantly lower Mn concentrations in the biomass of the birches in the FW and MT stands in comparison with the CM stands, as well as other silver birch stands reported on in the literature [24,43,44,45,46]. This is probably due to both the alkaline character of the soils under both the FW and MT stands and their high Ca contents, together causing a reduction in Mn availability [57].

The soil-to-plant enrichment patterns, expressed as BAF, further support the interpretation that silver birch acts primarily as a tolerant colonizer rather than an efficient hyperaccumulator of the analyzed trace elements on Technosols. Across stands and organs, BAFs for Fe, Mn, Cu, and Zn remained consistently below 1, indicating no systematic enrichment of biomass relative to total soil pools and, consequently, limited phytoextraction potential under the studied conditions [58]. In contaminated soils, BAF values < 1 are commonly interpreted as an exclusion/stabilization-type response rather than an accumulation strategy, especially in woody species, where metal uptake and translocation are often physiologically constrained [59]. Importantly, hyperaccumulator status is defined primarily by shoot concentration thresholds and consistent enrichment behaviour, and it is rarely met by woody pioneer species. Using classical criteria [52], the contents observed in this study remain far below hyperaccumulation requirements. Therefore, the present BAF patterns are more consistent with phytostabilisation and site cover development (erosion control, assisted succession) than with metal phytoextraction [60].

The presence of trace elements in post-industrial areas can affect nutrient availability. Our results show that, among the studied macronutrients, the N and P contents in the biomass differed significantly between the stands (Figure 4). Because these are the major nutrients for plant growth and development, their availability is often a limiting factor in ecosystems. In the literature, the N and P contents in silver birch biomass occupy a wide range, and compared to several other works, e.g., [24,25,27,43,44], their accumulation in our study was relatively low, especially in the FW stand. Although industrial/post-industrial areas are usually lacking in these elements [61,62], their low concentration in the biomass of the FW stand may have been magnified due to salinity stress [63]. Some studies have also indicated that phosphogypsum contains substantial amounts of P (from 2.5% to 7.5%) [64,65,66]. This is contradictory to the results of our study, where the average content of P in the FW stand was considerably lower (approximately 0.07%). Therefore, phosphogypsum does not appear to be a P source for plants. This is in line with the reports of Nayak et al. (2011) [67] and Quintero et al. (2014) [68], which explain the low P accumulation in the FW stand in our study (Figure 4). This may be related to the high Ca contents (Supplementary Materials and Figure 3) found in phosphogypsum, mainly in the form of gypsum (CaSO4·2H2O), which originates during the reaction of sulfuric acid with calcium phosphate (apatite) during the processing of phosphate ores in chemical plants. The low solubility of P in this material has also been pointed out by Al-Karaki and Al-Omoush (2002) [69] and Ekholm et al. (2011) [70]. In the soils from the CM stand, the mineralogical composition indicated significant proportions of bassetite [Fe2+(UO2)2(PO4)2·10H2O], torbernite [Cu(UO2)2(PO4)2·12H2O], and parsonsite [Pb2(UO2)(PO4)2·2H2O] [71], which would explain the higher P contents in the soils of this stand and therefore the higher contents in the biomass of the silver birches, similarly to the cases presented by Hytönen et al. (2014) [43], Daugaviete et al. (2015) [25], Rustowska (2022, 2024) [24,44], and Jonczak et al. (2023) [45].

The K contents in the silver birch leaves were within the range reported in the literature, but there is a large variability in these data (1897–99,100 mg kg−1), with the studies representing various habitats [5,24,25,27,42,43,44,45,72,73]. This reveals the strong impact of site conditions on the uptake and accumulation of this element in birch biomass, as also reflected in our study. The K accumulation was significantly higher in the stand (CM) where K was present in higher amounts in the soil (Figure 3 and Figure 4). The stands where there were lower amounts of K in the soil (FW and MT) had much higher soil Ca and/or Mg concentrations, which may have affected the distribution of K in the biomass [74,75].

As mentioned, the soils of the investigated heaps had relatively high Ca and Mg contents as well as elevated S and Fe contents, compared to the average contents of Polish soils [76]. The abundance of Ca and S in the FW stand was strongly associated with its mineral composition, as phosphogypsum comprises mainly gypsum [77,78]. Saadaoui et al. (2017) [79] determined that the Ca oxide (CaO) and S trioxide (SO3) contents in this waste were 24%–34% and 48%–58%, respectively. The silver birch overgrowing the industrial chemical plant waste (FW stand) and the Pb–Zn mine-tailings (MT stand) seems, to some extent, to have responded to a Ca- and S-rich substrate. However, this observation is inconsistent with the findings of other authors in terms of S and various plant species [63,80,81,82,83] exposed to phosphogypsum. This is likely due to the use of fresh phosphogypsum in the experiments conducted by these authors. Because the dissolution of phosphogypsum is gradual, its deposition at the FW stand occurred over an extended period of time, which allowed for the release of S and its uptake by the birch (Figure 4). The silver birch leaf Ca contents in the FW and MT stands were almost 4000 times higher than those reported from natural forest stands [24,44,73], and also higher than in birches growing in an urban area [72] and on post-coal and post-smelter heaps [5]. The Mg contents were also elevated compared to the data reported in Rustowska (2022, 2024) [24,44], especially in the MT and CM stands, but were generally comparable to those presented in Oksanen (2005) [42], Daugaviete et al. (2015) [25], Modrzewska (2016) [72], Novák et al. (2017) [73], Sitko et al. (2021) [5], and Jonczak et al. (2023) [45]. The Fe accumulation in the birch leaves in our study was similar to the contents reported in the works of several other authors [5,24,42,43,44,45], except in the birches overgrowing the MT stand, which were characterized by Fe contents that were up to several times higher. The differences in the biomass contents of these elements in this study seem to have a multifactorial basis, with the predominant impacts being their abundance and reactions in the soil. In addition, the overall lower nutrient content of the CM stand may have been influenced by the high proportion of sand in the soil (Table 2), allowing the leaching of nutrients into deeper horizons inaccessible to root uptake [84]. Elevated BAF values for some macronutrients (particularly N, P, and K) should be interpreted primarily in terms of plant nutritional demand and internal cycling. For fast-growing pioneer trees, the preferential allocation of N and P (and often K) to metabolically active tissues is a common functional trait, whereas base-rich or chemically extreme substrates may decouple total soil pools from plant enrichment because BAF integrates both physiological regulation and soil chemical controls [85]. Consequently, exceptionally high BAF values can arise in some cases from the index structure itself (ratio to the soil denominator), particularly when total soil contents are very low or when the dominant soil pools are poorly representative of bioavailable fractions. This is one reason why BAF is recommended as a comparative screening metric rather than a mechanistic proxy of uptake [59]. Overall, the BAF framework supports interpreting silver birch on these heaps mainly as a species facilitating vegetation establishment and element retention.

The nutrient distribution pattern in this study can be interpreted in the context of element mobility and internal cycling in trees. In general, leaves are expected to be enriched in highly mobile macronutrients due to strong physiological demand and efficient re-translocation during senescence, whereas stemwood typically shows the lowest concentrations because it functions mainly as structural tissue with limited metabolic turnover [86,87]. Such “leaf-dominant” partitioning is therefore consistent with the role of foliage as a primary sink for N, P, and K required for photosynthetic machinery and growth [88]. At the same time, deviations from the leaf-dominant pattern—particularly the tendency of some elements to be relatively elevated in roots under the most chemically extreme Technosol conditions—can be explained mechanistically by constraints imposed at the soil–root interface and along the root-to-shoot transport pathway. First, element bioavailability and speciation are strongly controlled by soil pH and base status; under alkaline, Ca-rich conditions, the availability of several micronutrients, notably Mn, declines markedly, which can restrict uptake and long-distance transport to aboveground organs [55,56,57,89]. Second, trees frequently limit the upward translocation of potentially toxic metals by retaining them in belowground compartments through apoplastic binding in cell walls, vacuolar sequestration, and complexation with organic ligands (e.g., phytochelatins and organic acids), which favours phytostabilisation rather than shoot enrichment [90,91,92,93]. Finally, the interpretation of root-enriched patterns must consider methodological aspects inherent to root chemistry: even after careful cleaning, fine mineral particles may remain attached to roots and can inflate measured concentrations of less mobile elements, as highlighted in methodological studies addressing soil contamination of root samples [94].

5. Conclusions

Our findings confirm our first hypothesis, that the properties of Technosols and the general site conditions of the waste heaps have had a historical influence on the nutritional status of the silver birches. The soils of the stands were generally abundant in nutrients and, in most cases, also contaminated with trace elements. These soil elemental contents, along with the different soil pH values, influenced the accumulation of elements in the silver birch biomass in diverse ways, depending on the type of element, the biomass fraction, and the stand. Based on our statistical results, the significant differences between the stands involved the N, P, and Mg contents followed by K, Ca, and S among the macronutrients, while among the micronutrients, the Mn followed by the Fe, Zn, and Cu contents were important. These differences were most common between the historical Cu mine (CM stand) and abandoned chemical plant waste (FW stand) heaps. Our second hypothesis, concerning the possibility of considering silver birch as a hyperaccumulator of the studied trace elements, could not be confirmed based on our biomass data and the quantity requirements given in the literature. The distribution of nutrients in the silver birch biomass was uneven, which is typical for trees. However, some elements slightly differed from the expected trends for silver birch, as presented in other works. Depending on the element and stand, the fine roots or leaves contained the most abundant elements, while the stemwood tended to accumulate the least of the studied elements.

The study had two main limitations. First, sampling was conducted once within a single growing season; therefore, seasonal or interannual variability in element contents and bioaccumulation could not be evaluated. Second, no speciation or operationally defined bioavailable fractions of elements were determined. Thus, the soil–plant relationships should be interpreted in terms of extractable pools and not directly bioavailable forms.

From a management perspective, the results indicate that silver birch is best suited for phytostabilisation and early revegetation of Technosols rather than for phytoextraction of the analyzed trace elements. In practice, silver birch can be recommended as a candidate for assisted natural regeneration or active planting on post-industrial heaps where rapid canopy establishment, erosion control, and improvement of site microclimate are priority objectives. However, because trace-element enrichment in aboveground biomass was limited, planting should be combined with site-specific risk assessment and, where necessary, complementary measures (e.g., surface sealing, amendments, or long-term monitoring) when soils exceed the regulatory thresholds for potentially toxic elements.

Overall, our determination of the nutrient accumulations in the silver birch biomass growing on post-industrial waste heaps provides a better understanding of the functioning of this species and its adaptation abilities under the conditions of degraded areas, and supports its use primarily as a stabilizing pioneer in the reclamation of contaminated Technosols.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/f17010040/s1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.R.; Data curation, B.R.; Formal analysis, B.R. and M.O.; Investigation, B.R., J.J., and W.K.; Methodology, B.R.; Resources, B.R. and J.J.; Supervision, J.J.; Validation, B.R., J.J., and W.K.; Visualization, B.R.; Writing—original draft, B.R.; Writing—review and editing, B.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article and Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Galos, K.; Szlugaj, J. Management of hard coal mining and processing wastes in Poland. Gospod. Surowcami Miner. (Miner. Resour. Manag.) 2014, 30, 51–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics Poland. Ochrona Środowiska 2023; Główny Urząd Statystyczny (GUS): Warszawa, Poland, 2023; p. 188.

- Kurpińska, M. Składowiska fosfogipsu–problem w Polsce i na świecie. Mater. Bud. 2010, 12, 19–20. [Google Scholar]

- Ash, H.J.; Gemmell, R.P.; Bradshaw, A.D. The introduction of native plant species on industrial waste heaps: A test of immigration and other factors affecting primary succession. J. Appl. Ecol. 1994, 31, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitko, K.; Opała-Owczarek, M.; Jemioła, G.; Gieroń, Z.; Szopiński, M.; Owczarek, P.; Rudnicka, M.; Małkowski, E. Effect of drought and heavy metal contamination on growth and photosynthesis of silver birch trees growing on post-industrial heaps. Cells 2021, 11, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swęd, M.; Potysz, A.; Duczmal-Czernikiewicz, A.; Siepak, M.; Bartz, W. Bioweathering of Zn–Pb-bearing rocks: Experimental exposure to water, microorganisms, and root exudates. Appl. Geochem. 2021, 130, 104966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skubała, K. Vascular flora of sites contaminated with heavy metals on the example of two post-industrial spoil heaps connected with manufacturing of zinc and lead products in Upper Silesia. Arch. Environ. Prot. 2011, 37, 57–74. [Google Scholar]

- Hynynen, J.; Niemistö, P.; Viherä-Aarnio, A.; Brunner, A.; Hein, S.; Velling, P. Silviculture of birch (Betula pendula Roth and Betula pubescens Ehrh.) in northern Europe. Forestry 2010, 83, 103–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bojarczuk, K.; Karolewski, P.; Oleksyn, J.; Kieliszewska-Rolicka, B.; Żytkowiak, R.; Tjoelker, M.G. Effect of polluted soil and fertilisation on growth and physiology of silver birch (Betula pendula Roth.) seedlings. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2002, 11, 483–492. [Google Scholar]

- Franiel, I.; Więski, K. Leaf features of silver birch (Betula pendula Roth). Variability within and between two populations (uncontaminated vs Pb-contaminated and Zn-contaminated site). Trees 2005, 19, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzierżanowski, K.; Gawroński, S.W. Use of trees for reducing particulate matter pollution in air. Nat. Sci. 2011, 69–73. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, J.; Qvarfort, U.; Sjöström, J. Betula pendula: A promising candidate for phytoremediation of TCE in northern climates. Int. J. Phytoremediat. 2015, 17, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ernst, W.H.O.; Nelissen, H.J.M. Bleeding sap and leaves of silver birch (Betula pendula) as bioindicators of metal contaminated soils. Int. J. Environ. Pollut. 2008, 33, 160–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franiel, I.; Babczyńska, A. The growth and reproductive effort of Betula pendula Roth in a heavy-metals polluted area. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2011, 20, 1097–1101. [Google Scholar]

- Alagic, S.Č.; Šerbula, S.S.; Tŏic, S.B.; Pavlović, A.N.; Petrović, J.V. Bioaccumulation of arsenic and cadmium in birch and lime from the Bor region. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2013, 65, 671–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dmuchowski, W.; Gozdowski, D.; Brągoszewska, P.; Baczewska, A.H.; Suwara, I. Phytoremediation of zinc contaminated soils using silver birch (Betula pendula Roth). Ecol. Eng. 2014, 71, 32–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurković, J.; Kazlagić, A.; Sulejmanović, J.; Smječanin, N.; Karalija, E.; Prkić, A.; Nuhanović, M.; Kolar, M.; Albuquerque, A. Assessment of heavy metals bioaccumulation in Silver Birch (Betula pendula Roth) from an AMD active, abandoned gold mine waste. Environ. Geochem. Health 2023, 45, 9855–9873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosselli, W.; Keller, C.; Boschi, K. Phytoextraction capacity of trees growing on a metal contaminated soil. Plant Soil 2003, 256, 265–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pająk, M.; Halecki, W.; Gąsiorek, M. Accumulative response of Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris L.) and silver birch (Betula pendula Roth) to heavy metals enhanced by Pb-Zn ore mining and processing plants: Explicitly spatial considerations of ordinary kriging based on a GIS approach. Chemosphere 2016, 168, 851–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niinemets, Ü. Responses of forest trees to single and multiple environmental stresses from seedlings to mature plants: Past stress history, stress interactions, tolerance and acclimation. For. Ecol. Manag. 2010, 260, 1623–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zvereva, E.L.; Roitto, M.; Kozlov, M.V. Growth and reproduction of vascular plants in polluted environments: A synthesis of existing knowledge. Environ. Rev. 2010, 18, 355–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gawęda, T.; Małek, S.; Zasada, M.; Jagodziński, A. Allocation of elements in a chronosequence of silver birch afforested on former agricultural lands. Drewno 2014, 57, 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellsten, S.; Helmisaari, H.-S.; Melin, Y.; Skovsgaard, J.P.; Kaakinen, S.; Kukkola, M.; Akselsson, C. Nutrient concentrations in stumps and coarse roots of Norway spruce, Scots pine and silver birch in Sweden, Finland and Denmark. For. Ecol. Manag. 2013, 290, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rustowska, B. Nutrient distribution and bioaccumulation in silver birch (Betula pendula Roth) biomass grown in nutrient-poor soil. Trees 2024, 38, 441–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daugaviete, M.; Korica, A.M.; Silins, I.; Barsevskis, A.; Bardulis, A.; Bardule, A.; Spalvis, K.; Daugavietis, M. The use of mineral nutrients for biomass production by young birch stands and stands vitality in different forest growing conditions. J. Environ. Sci. Eng. B 2015, 4, 177–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietrzykowski, M. Macronutrient accumulation and relationships in a Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris L.) ecosystem on reclaimed opencast lignite mine spoil heaps in central Poland. In Proceedings of the 25th Annual Meeting of ASMR and 10th IALR, “New Opportunities to Apply Our Science”, Richmond, VA, USA, 14–19 June 2008; pp. 856–877. [Google Scholar]

- Kuznetsova, T.; Rosenvald, K.; Ostonen, I.; Helmisaari, H.-S.; Mandre, M.; Lõhmus, K. Survival of black alder (Alnus glutinosa L.), silver birch (Betula pendula Roth.) and Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris L.) seedlings in a reclaimed oil shale mining area. Ecol. Eng. 2010, 36, 495–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dziekoński, T. Wydobywanie i Metalurgia Kruszców na Dolnym Śląsku od XIII do Połowy XX w; Zakład Narodowy im. Ossolińskich, Wydawnictwo PAN: Wrocław, Poland, 1972; p. 420. [Google Scholar]

- Woś, A. Zeszyty Instytutu Geografii i Przestrzennego Zagospodarowania PAN nr 20. In Regiony Klimatyczne Polski w Świetle Częstości Występowania Różnych Typów Pogody; IGiPZ PAN: Warsaw, Poland, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Strzyszcz, Z. Właściwości fizyczne, fizykochemiczne i chemiczne odpadów poflotacyjnych rud cynku i ołowiu w aspekcie ich biologicznej rekultywacji. Arch. Ochr. Śr. 1980, 3–4, 19. [Google Scholar]

- International Union of Soil Sciences Working Group. World Reference Base for Soil Resources. In International Soil Classification System for Naming Soils and Creating Legends for Soil Maps, 4th ed.; International Union of Soil Sciences (IUSS): Vienna, Austria, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Soil Survey Division Staff. Soil Survey Manual; Soil Conservation Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture Handbook 18; U.S. Department of Agriculture: Washington, DC, USA, 1993.

- Kabała, C.; Greinert, A.; Charzyński, P.; Uzarowicz, Ł. Technogenic soils—Soils of the year 2020 in Poland. Concept, properties and classification of technogenic soils in Poland. Soil Sci. Annu. 2020, 71, 267–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzarowicz, Ł.; Charzyński, P.; Greinert, A.; Hulisz, P.; Kabała, C.; Kusza, G.; Kwasowski, W.; Pędziwiatr, A. Studies of technogenic soils in Poland: Past, present, and future perspectives. Soil Sci. Annu. 2020, 71, 281–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truog, E. Soil reaction influence on availability of plant nutrients. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1947, 11, 305–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cataldo, D.A.; Wildung, R.E. Soil and plant factors influencing the accumulation of heavy metals by plants. Environ. Health Perspect. 1978, 27, 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kompała, A.; Błońska, A.; Woźniak, G. Vegetation of the “Żabie Doły” area (Bytom) covering the wastelands of zinc-lead industry. Arch. Environ. Protect. 2004, 30, 59–76. [Google Scholar]

- Karczewska, A.; Bogda, A.; Gałka, B.; Szulc, A.; Czwarkiel, D.; Duszyńska, D. Natural and anthropogenic soil enrichment in heavy metals in the areas of former metallic ore mining in the Sudety Mts. Pol. J. Soil Sci. 2006, 39, 143–150. [Google Scholar]

- Tarnawczyk, M.; Uzarowicz, Ł.; Perkowska-Pióro, K.; Pędziwiatr, A.; Kwasowski, W. Effect of land reclamation on soil properties, mineralogy and trace-element distribution and availability: The example of technosols developed on the tailing disposal site of an abandoned Zn and Pb mine. Minerals 2021, 11, 559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minister of the Environment. Regulation of the Minister of the Environment of 1 September 2016 on the Method of the Contamination Assessment of the Earth Surface. J. Laws 2016, 1395. [Google Scholar]

- Gałuszka, A.; Migaszewski, Z.M.; Dołęgowska, S.; Michalik, A.; Duczmal-Czernikiewicz, A. Geochemical background of potentially toxic trace elements in soils of the historic copper mining area: A case study from Miedzianka Mt., Holy Cross Mountains, south-central Poland. Environ. Earth Sci. 2015, 74, 4589–4605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oksanen, E.; Riikonen, J.; Kaakinen, S.; Holopainen, T.; Vapaavuori, E. Structural characteristics and chemical composition of birch (Betula pendula) leaves are modified by increasing CO2 and ozone. Glob. Change Biol. 2005, 11, 732–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hytönen, J.; Saramäki, J.; Niemistö, P. Growth, stem quality and nutritional status of Betula pendula and Betula pubescens in pure stands and mixtures. Scand. J. For. Res. 2014, 29, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rustowska, B. Long-term wildfire effect on nutrient distribution in silver birch (Betula pendula Roth) biomass. Soil Sci. Annu. 2022, 73, 149943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonczak, J.; Oktaba, L.; Chojnacka, A.; Pawłowicz, E.; Kruczkowska, B.; Oktaba, J.; Słowińska, S. Nutrient fluxes via litterfall in silver birch (Betula pendula Roth) stands growing on post-arable soils. Eur. J. For. Res. 2023, 142, 981–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samecka-Cymerman, A.; Kempers, A.J. Accumulation ratios of elements in selected plant species from black coal mine dumps in Lower Silesia (Poland). Pol. J. Ecol. 2003, 51, 377. [Google Scholar]

- Butkus, D.; Baltrėnaitė, E. Transport of heavy metals from soil to Pinus sylvestris L. and Betula pendula trees. Ekologija 2007, 53, 29–36. [Google Scholar]

- Szwalec, A.; Lasota, A.; Kędzior, R.; Mundała, P. Variation in heavy metal content in plants growing on a zinc and lead tailings dump. Appl. Ecol. Environ. Res. 2018, 16, 5081–5094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kříbek, B.; Míková, J.; Knésl, I.; Mihaljevič, M.; Sýkorová, I. Uptake of trace elements and isotope fractionation of Cu and Zn by birch (Betula pendula) growing on mineralized coal waste pile. Appl. Geochem. 2020, 122, 104741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajković, M.B.; Blagojević, S.D.; Jakovljević, M.D.; Todorović, M.M. The application of atomic absorption spectrophotometry (AAS) for determining the content of heavy metals in phosphogypsum. J. Agric. Sci. 2000, 45, 155–164. [Google Scholar]

- Kosiorek, M.; Modrzewska, B.; Wyszkowski, M. Levels of selected trace elements in Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris L.), silver birch (Betula pendula L.), and Norway maple (Acer platanoides L.) in an urbanized environment. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2016, 188, 598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, A.J.M.; Brooks, R.R. Terrestrial higher plants which hyperaccumulate metallic elements—A review of their distribution, ecology and phytochemistry. Biorecovery 1989, 1, 81–126. [Google Scholar]

- Kicińska, A.; Gruszecka-Kosowska, A. Long-term changes of metal contents in two metallophyte species (Olkusz area of Zn-Pb ores, Poland). Environ. Monit. Assess. 2016, 188, 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahmoud, E.; Abd El-Kader, N. Heavy metal immobilization in contaminated soils using phosphogypsum and rice straw compost. Land Degrad. Dev. 2015, 26, 819–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, E.R. Studies in soil and plant manganese: II. The relationship of soil pH to manganese availability. Plant Soil 1962, 16, 247–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reimann, C.; Arnoldussen, A.; Finne, T.E.; Koller, F.; Nordgulen, Ø.; Englmaier, P. Element contents in mountain birch leaves, bark and wood under different anthropogenic and geogenic conditions. Appl. Geochem. 2007, 22, 1549–1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazrul-Islam, A.K.M. Effects of interaction of calcium and manganese on the growth and nutrition of Epilobium hirsutum L. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 1986, 32, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proc, K.; Bulak, P.; Kaczor, M.; Bieganowski, A.A. New approach to quantifying bioaccumulation of elements in biological processes. Biology 2021, 10, 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capuana, M. A review of the performances of woody and herbaceous plants used for phytoremediation in urban and peri-urban areas. iFor.-Biogeosci. For. 2020, 13, 139–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purwadi, I.; Erskine, P.D.; Casey, L.W.; van der Ent, A. Recognition of trace element hyperaccumulation based on empirical datasets derived from XRF scanning of herbarium specimens. Plant Soil 2023, 492, 429–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietrzykowski, M.; Krzaklewski, W.; Woś, B. Zawartość pierwiastków śladowych (Mn, Zn, Cu, Cd, Pb, Cr) w liściach olsz (Alnus sp.) zastosowanych jako gatunki fitomelioracyjne na składowisku odpadów paleniskowych. Zesz. Nauk. Inż. Śr./Univ. Zielonogórs. 2013, 151, 26–34. [Google Scholar]

- Pająk, M.; Woś, B.; Likus-Cieślik, J.; Bobik, I.; Otremba, K.; Pietrzykowski, M. Effect of properties of technogenic soils developed from different lignite spoil heap materials on the growth of Scots pine Pinus sylvestris L. Sylwan 2023, 167, 61–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stępień, K.; Stępień, P.; Piszcz, U.; Spiak, Z. Assessment of phosphogypsum waste use in plant nutrition. Arch. Environ. Prot. 2022, 48, 53–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordell, D.; White, S. Sustainable phosphorus measures: Strategies and technologies for achieving phosphorus security. Agronomy 2013, 3, 86–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pliaka, M.; Gaidajis, G. Potential uses of phosphogypsum: A review. J. Environ. Sci. Health A 2022, 57, 746–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, D.; Xia, J.; Zhou, N.; Xu, M.; Li, X.; Zhang, L.; Du, S.; Gao, H. The utilization of phosphogypsum as a sustainable phosphate-based fertilizer by Aspergillus niger. Agronomy 2022, 12, 646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayak, S.; Mishra, C.S.K.; Guru, B.; Rath, M. Effect of phosphogypsum amendment on soil physicochemical properties, microbial load and enzyme activities. J. Environ. Biol. 2011, 32, 613–617. [Google Scholar]

- Quintero, J.M.; Enamorado, S.; Mas, J.L.; Abril, J.M.; Polvillo, O.; Delgado, A. Phosphogypsum amendments and irrigation with acidulated water affect tomato nutrition in reclaimed marsh soils from SW Spain. Span. J. Agric. Res. 2014, 12, 809–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Karaki, G.N.; Al-Omoush, M. Wheat response to phosphogypsum and mycorrhizal fungi in alkaline soil. J. Plant Nutr. 2002, 25, 873–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekholm, P.; Jaakkola, E.; Kiirikki, M.; Lahti, K.; Lehtoranta, J.; Mäkelä, V.; Näykki, T.; Pietola, L.; Tattari, S.; Valkama, P.; et al. The effect of gypsum on phosphorus losses at the catchment scale. Finn. Environ. 2011, 33, 44. [Google Scholar]

- Siuda, R.; Gołębiowska, B. Nowe dane o minerałach wietrzeniowych złoża Miedzianka-Ciechanowice w Rudawach Janowickich (Dolny Śląsk, Polska). Przegląd Geol. 2011, 59, 226–234, 252. [Google Scholar]

- Modrzewska, B.; Kosiorek, M.; Wyszkowski, M. Content of some nutrients in Scots pine, silver birch and Norway maple in an urbanized environment. J. Elem. 2016, 21, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novák, J.; Dušek, D.; Kacálek, D.; Slodičák, M. Nutrient content in silver birch biomass on nutrient-poor, gleyic sites. Zpr. Lesn. Výzk. 2017, 62, 135–141. [Google Scholar]

- Overstreet, R.; Jacobson, L.; Handley, R. The effect of calcium on the absorption of potassium by barley roots. Plant Physiol. 1952, 27, 583–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, S.; Li, H.; Zhang, X.; Gao, J.; Ma, R.; Ma, L.; Ma, J. Effects of magnesium imbalance on root growth and nutrient absorption in different genotypes of vegetable crops. Plants 2023, 12, 3518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lis, J.; Pasieczna, A. Atlas Geochemiczny Polski 1:2,500,000; Państwowy Instytut Geologiczny-PIB: Warsaw, Poland, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Mechi, N.; Ammar, M.; Loungou, M.; Elaloui, E. Thermal study of Tunisian phosphogypsum for use in reinforced plaster. Br. J. Appl. Sci. Technol. 2016, 16, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garbaya, H.; Jraba, A.; Khadimallah, M.A.; Elaloui, E. The development of a new phosphogypsum-based construction material: A study of the physicochemical, mechanical and thermal characteristics. Materials 2021, 14, 7369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saadaoui, E.; Ghazel, N.; Ben Romdhane, C.; Massoudi, N. Phosphogypsum: Potential uses and problems—A review. Int. J. Environ. Stud. 2017, 74, 558–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caires, E.F.; Kusman, M.T.; Barth, G.; Garbuio, F.J.; Padilha, J.M. Changes in soil chemical properties and corn response to lime and gypsum applications. Rev. Bras. Ciênc. Solo 2004, 28, 125–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blum, S.C.; Caires, E.F.; Alleoni, L.R.F. Lime and phosphogypsum application and sulfate retention in subtropical soils under no-till system. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2013, 13, 279–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blum, S.C.; Garbuio, F.J.; Joris, H.A.W.; Caires, E.F. Assessing available soil sulphur from phosphogypsum applications in a no-till cropping system. Exp. Agric. 2014, 50, 516–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouray, M.; Moir, J.; Condron, L.; Lehto, N. Impacts of phosphogypsum, soluble fertilizer and lime amendment of acid soils on the bioavailability of phosphorus and sulphur under lucerne (Medicago sativa). Plants 2020, 9, 883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorensen, P.; Jensen, E.S. Mineralization–immobilization and plant uptake of nitrogen as influenced by the spatial distribution of cattle slurry in soils of different texture. Plant Soil 1995, 173, 283–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Zhang, C.; Zhu, B.; Liu, X.; Xiao, H.; Liu, S.; Shao, H. Systematic evaluation of plant metals/metalloids accumulation efficiency: A global synthesis of bioaccumulation and translocation factors. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1602951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aerts, R. Nutrient resorption from senescing leaves of perennials: Are there general patterns? J. Ecol. 1996, 84, 597–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergutz, L.; Manzoni, S.; Porporato, A.; Novais, R.F.; Jackson, R.B. Global resorption efficiencies and concentrations of carbon and nutrients in leaves of terrestrial plants. Ecol. Monogr. 2012, 82, 205–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marschner, H. Mineral Nutrition of Higher Plants, 2nd ed.; Academic Press: London, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Millaleo, R.; Reyes-Díaz, M.; Ivanov, A.G.; Mora, M.L.; Alberdi, M. Manganese as essential and toxic element for plants: Transport, accumulation and resistance mechanisms. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2010, 10, 470–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, J.L. Cellular mechanisms for heavy metal detoxification and tolerance in plants. J. Exp. Bot. 2002, 53, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clemens, S. Toxic metal accumulation, responses to exposure and mechanisms of tolerance in plants. Biochimie 2006, 88, 1707–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krzesłowska, M. The cell wall in plant cell response to trace metals: Polysaccharide remodeling and its role in defense strategy. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2011, 33, 35–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podar, D.; Maathuis, F.J.M. The role of roots and rhizosphere in providing tolerance to toxic metals and metalloids. Plant Cell Environ. 2022, 45, 719–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, H.W.; Reuss, D.E.; Elliott, E.T. Correcting estimates of root chemical composition for soil contamination. Ecology 1999, 80, 702–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.