Abstract

Forested areas are defined as wooded regions characterized by dense vegetation, largely preserved natural ecosystem features, and availability for recreational use. These areas play a critical role in maintaining ecological balance and are increasingly utilized as preferred sites for various outdoor activities. However, the growing intensity of recreational activities in such sensitive ecosystems contributes to increased waste generation and poses significant threats to environmental sustainability. The objective of this study is to calculate the carbon footprint resulting from waste produced during recreational activities in forested areas of Lithuania, Turkey, and Morocco, and to identify innovative waste management strategies aimed at achieving clean and safe forest ecosystems. This study includes a comparison of Turkey, Lithuania, and Morocco. Quantitative data and carbon footprint calculations were conducted, while quantitative methods were also employed through semi-structured interviews with experts. Firstly, carbon footprint calculations were carried out based on the types and amounts of waste generated by participants. Subsequently, semi-structured interviews were conducted with experts and participants from all three countries to identify issues related to waste management and innovative waste management strategies. The carbon footprint resulting from waste generation was estimated to be 1517.26 kg in Turkey, 613.25 kg in Lithuania, and 735.68 kg in Morocco. Experts from Turkey, Lithuania, and Morocco have proposed innovative solutions for improving waste management systems in their respective countries. In Turkey, the predominant view emphasizes the need for increased use of digital tools, stricter enforcement measures, a rise in the number of personnel and waste bins, as well as the expansion of volunteer-based initiatives. In Lithuania, priority is given to educational and awareness-raising activities, updates to legal regulations, the placement of recycling bins, the development of infrastructure, and the promotion of environmentally friendly projects. In Morocco, it is highlighted that there is a need for stronger enforcement mechanisms, updated legal frameworks, increased staffing, more frequent waste collection, and the implementation of educational programs.

1. Introduction

In line with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, environmental sustainability objectives and the risks associated with these goals are frequently discussed by various segments of society, particularly within academia. Global warming and environmental degradation, in particular, are evaluated and monitored within the framework of the life cycle [1,2,3,4,5,6,7].

Today, the increasing migration of people to urban areas in pursuit of work–life balance has heightened expectations regarding quality of life. In meeting these expectations, recreational activities have gained increasing importance. Particularly as a means of escaping the effects of intense urbanization, individuals are expressing a growing desire to participate in recreational activities organized in forested areas. However, this increased human mobility is bringing about environmental problems in forested regions. One of the most prominent of these problems is the waste generated by human activities [8,9,10]. Waste produced during recreational activities, such as hiking, camping, and picnicking, in forested areas is considered a major threat to ecosystems.

Recently, recreational events in forested areas have seen high demand, with large numbers of participants. However, this increased demand also leads to significant waste generation, one of the contributors to the carbon footprint. On average, more than four billion tons of waste are produced annually from recreational activities, and the recycling of this waste is becoming increasingly challenging [11]. Within the scope of this research, it is estimated that in Turkey, an average of 150,000 to 200,000 tons of waste are generated annually in forested areas, particularly around Istanbul, Ankara, and Antalya, due to intensive recreational activities. The majority of this waste is produced in picnic sites and recreational parks. In Lithuania, approximately 20,000 to 30,000 tons of waste are generated each year in forested areas near Vilnius and Kaunas, with plastics and organic materials making up the largest portion of this waste. In Morocco, annual waste generation in forested recreational areas surrounding Casablanca and Rabat is estimated to be between 50,000 and 70,000 tons, where inadequate waste management infrastructure contributes to environmental problems. These approximate annual averages and the specified locations where waste is produced contribute to a clearer understanding of the spatial distribution and magnitude of solid waste, and they highlight the critical waste management areas that need to be targeted in each country.

The collection and disposal of waste generated through recreational activities, as well as the reduction of the associated carbon footprint, are not solely dependent on technical measures. Rather, achieving sustainable environmental goals requires a process management approach that takes into account socio-cultural, institutional, and behavioral factors [12]. In this context, the research is grounded in institutional theory and aims to reveal how waste management processes in forested areas are shaped by the regulative, normative, and cognitive structures of the respective countries [13].

The attitudes and behaviors of participants toward the environment during recreational activities conducted in forested areas can be examined within the framework of the theory of planned behavior. This theory emphasizes that individuals’ tendencies to generate or manage waste during such activities are influenced by social norms [14,15]. In an effort to attract more people to recreational activities, artificial environments are being created within forested areas. This poses a risk primarily to biodiversity and negatively affects the natural habitats of wildlife. Human-generated waste, often consisting of plastic, glass, metal, and organic materials, not only contributes to the carbon footprint but also undermines the goal of maintaining clean and safe forest environments [16,17]. Furthermore, high levels of waste production contribute to climate change by increasing the carbon footprint [18,19,20,21].

In sustainable environmental management, countries’ waste management capacities, the level of infrastructure related to waste processes, and the availability of relevant technical equipment play a critical role. This is because recycling systems within countries are shaped by these factors, and their effectiveness is largely influenced by them [22,23]. Moreover, establishing a broad stakeholder network and enhancing participation and cooperation can alleviate the burden on public authorities in waste management. This is because waste management is not solely a public responsibility. Civil society organizations and private sector actors are also expected to take on responsibilities and develop collaborative policies within this process [24]. National and international institutions and organizations are attempting to take measures to mitigate the environmental impacts and carbon footprint resulting from waste generated during recreational activities in forested areas [25,26,27]. In this context, forest managers, recreation specialists, and participants are expected to take responsibility for reducing waste and minimizing the carbon footprint by adopting environmentally friendly approaches [28]. It is therefore foreseeable that managers and local communities involved in the management of forests and recreational activities should be environmentally aware and possess a high level of ecological sensitivity [29]. Waste generation in forested areas poses significant risks for environmental degradation, negatively affects ecosystems, and threatens biodiversity. At the same time, innovative solutions for waste management have become inevitable. Currently, major challenges include the irregular collection of waste, insufficient personnel, and the lack of waste collection centers and disposal sites. In this context, the study aims to reveal the environmental impacts of waste generation and how these challenges hinder the effective management of waste. It is expected to make a significant contribution as a case study, specifically focusing on Turkey, Lithuania, and Morocco. Therefore, the study addresses and clearly defines the waste problem within the scope of sustainable environmental management, and it is expected to contribute meaningfully to sustainable environmental solutions.

The degradation of forested areas through recreational activities is not limited to environmental impacts; it also has socio-economic dimensions. It is essential to separate waste generated during these activities and render it suitable for recycling. Furthermore, reducing the carbon footprint caused by this waste represents another important aspect of the issue. In this regard, examining the waste produced in forested areas and the resulting carbon footprint in countries with different societal, cultural, and geographical characteristics—such as Lithuania, Turkey, and Morocco—can contribute to the development of strategies addressing environmental degradation on both local and global scales. This study, through expert opinions and fieldwork based on quantitative data in the respective countries, aims to closely examine waste management processes while emphasizing innovative waste management strategies.

Waste generated as a result of recreational activities poses a significant risk to environmental sustainability goals, disrupts the balance of natural life, and may negatively impact ecosystems within the affected areas. In particular, the pollution of natural resources—such as soil and water—threatens regional biodiversity and hinders the sustainable management of forested areas. Therefore, it is essential to focus on identifying the root causes of waste generation and developing strategies to reduce such waste. The development and exploration of innovative solutions are of critical importance in this context. This study aims to identify the underlying causes of waste generation and to propose innovative solutions for reducing waste production in recreational forest environments.

This research distinguishes itself from other studies in the literature. It provides findings related to the waste generated during recreational activities in forested areas and the associated carbon footprint. Moreover, it offers innovative waste management solutions based on expert opinions in all three countries. While the existing literature typically focuses on the calculation of the carbon footprint in industrial sectors, the carbon footprint resulting from recreational activities in forested areas has not been widely studied.

The increasing demand for recreational activities is leading to a significant amount of waste production by individuals. To minimize the environmental impact of this waste, necessary precautions must be taken, and it is crucial that responsible individuals, institutions, and organizations adhere to these measures. Accordingly, the objective of this study is to calculate the carbon footprint resulting from waste produced during recreational activities in forested areas of Lithuania, Turkey, and Morocco, and to identify innovative waste management strategies aimed at achieving clean and safe forest ecosystems.

This study is one of the few comprehensive investigations that examine the waste problem arising from recreational activities conducted in forested areas across countries with diverse economic, socio-cultural, and legal infrastructures—namely Turkey, Lithuania, and Morocco. By employing both quantitative methods (carbon footprint analysis) and qualitative data (expert interviews), the research provides a multifaceted perspective on the challenges and proposes innovative strategies for sustainable waste management. While there are existing studies on waste management in the literature, many of these focus on a single country or region, limiting the generalizability of their findings. In contrast, the inclusion of three countries from different geographical and socio-political contexts enhances the potential for broader applicability of the results. Moreover, the study not only analyzes the current waste management challenges but also proposes sustainable and innovative solutions, which further contributes to its originality. The interdisciplinary approach—integrating the fields of recreation, forestry, and environmental sciences—underscores the study’s scholarly novelty and allows for significant conceptual and practical contributions to the existing body of literature.

Broad-based participation in waste management helps shape public perceptions, attitudes, and practical implementations regarding the environment, thereby fostering a systemic understanding essential for achieving sustainable environmental goals [30,31]. Accordingly, this study comparatively examines Turkey, Lithuania, and Morocco in terms of societal differences, legal frameworks, infrastructural capacities, and socio-cultural contexts. Additionally, the research includes comparative analyses aimed at identifying innovative solutions for waste management processes and calculating the carbon footprint associated with waste generated during recreational activities in forested areas.

The production of waste and the resulting environmental problems in recreational activities organized in forested areas are not merely the outcomes of behavioral patterns. These issues are also closely related to individuals’ attitudes and perceptions toward the environment. Environmental attitudes and behaviors are shaped significantly by the cultural heritage and social norms of each country [32,33]. In particular, it is essential that individuals exhibit environmentally responsible behavior by actively engaging in the protection of their surroundings. Cultural values and social understandings within different societies play a decisive role in the development and dissemination of environmental awareness. Collective consciousness and traditions of communal living are among the key factors that foster environmental responsibility [34]. Therefore, in countries such as Turkey, Lithuania, and Morocco—each characterized by distinct historical, cultural, and social norms—individual and societal attitudes and behaviors toward the environment carry particular significance. In line with the central theme of this research, issues such as waste generation and the mitigation of its environmental impacts are directly influenced by societal acceptance within each context. Accordingly, this study takes into account the individual and collective environmental attitudes and behaviors observed in the three countries under investigation.

In this context, based on expert opinions, it is anticipated that innovative solution proposals will be identified around a single, specific model tailored to the social structures of each of the three countries. In line with these objectives, the study aims to:

- Calculate the carbon footprint resulting from participant-generated waste during recreational activities in Turkey, Lithuania, and Morocco;

- Identify both common and country-specific challenges directly related to the generation, accumulation, and management of solid waste resulting from recreational activities in Turkey, Lithuania, and Morocco, with particular emphasis on the types of waste produced and the existing deficiencies in recycling practices;

- Develop and propose innovative and evidence-based waste management strategies based on the principles of sustainable development, tailored to the policy frameworks, infrastructure capacities, and behavioral characteristics of all three countries.

2. Research Methodology

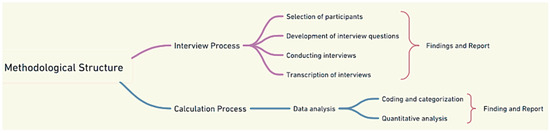

This study, designed with a multidisciplinary approach that integrates sports and environmental sciences, has been planned by the researchers to ensure effective and accurate results in accordance with scientific standards. The process and methodological structure of the study conducted in line with this plan are presented in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1.

Study plan.

This study includes a comparison of Turkey, Lithuania, and Morocco; quantitative data and carbon footprint calculations were conducted, while quantitative methods were also employed through semi-structured interviews with experts.

The selection of these three countries as the sample group was determined by their socio-cultural, societal, and economic differences. Due to these differences, each country exhibits various approaches and practices within the leisure industry. Turkey is characterized by an increasing interest in the leisure industry and the search for resources to support it; Lithuania, within the European Union, has comprehensive legal frameworks and an increasing emphasis on social responsibility; while Morocco, as a developing country, presents a significant case for examining the challenges and opportunities within the leisure industry. Therefore, the differences between these three countries offer valuable opportunities to understand how environmental issues are addressed, how opportunities in the leisure industry are evaluated, and how environmental sustainability practices are implemented.

Forested areas hosting recreational activities were selected from regions characterized by high accessibility, intensive use for outdoor activities, and availability of preliminary data on waste generation. In Turkey and Lithuania, forested areas in coastal regions and recreational parks are considered suitable sites due to their high visitor density, which inevitably leads to increased waste production. In Morocco, forested areas near urban environments and popular tourist destinations were chosen as study sites to reflect both local and tourist-driven waste pressures. These site-specific selections aim to facilitate a comprehensive examination of waste generation patterns and management challenges across diverse national contexts. It can be asserted that the sample selection enhances the transparency and contextual relevance of the research.

Firstly, carbon footprint calculations were carried out based on the types and amounts of waste generated by participants in recreational activities conducted in forested areas in each of the three countries during the past year (March 2024–March 2025). Subsequently, semi-structured interviews were conducted with experts and participants from all three countries, using a semi-structured interview form, to identify issues related to waste management and innovative waste management strategies aimed at achieving safe and clean environment goals during recreational activities in forested areas.

2.1. Methodological Framework for Carbon Footprint Calculation Process

2.1.1. Data Set and Data Collection

For the calculation of carbon footprints related to waste production, the amount of waste generated by participants during recreational activities conducted in forested areas between March 2024 and March 2025 was used as the data set, categorized by each type of waste. Data was obtained through public data-sharing platforms (official websites) shared by public institutions and non-governmental organizations in Turkey, Lithuania, and Morocco. According to the data presented in the 2024 Activity Report of the General Directorate of Nature Conservation and National Parks under the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry of the Republic of Türkiye, the average number of visitors to forested areas in the country has been determined. The report states that, in 2024, an average of 41,642,780 individuals visited forest areas for various purposes [35]. In the activity reports of Lithuanian State Forest Enterprise for 2024, it is stated that approximately 36% of the country is covered with forest areas. The average number of people visiting these areas is estimated to be 17,389,470 [36]. According to the Committee for Environment and Sustainable Development in Morocco, the average number of visitors to forest areas in Morocco is 24,387,964 people [37]. The data on visitor numbers used in the research are based on institutional reports in all three countries. Although the visitor numbers in these reports are not exact numbers (it is almost impossible to determine an exact and precise number), it is stated that there are annual average numbers regarding the number of visitors. The average number of participants in recreational activities and the total amount of waste produced in forested areas over the past year in each of the three countries are presented in Table 1 below.

Table 1.

Waste amounts by waste type.

According to the obtained data, the average per capita waste generation potential during recreational activities is 0.75 kg in Turkey, 0.65 kg in Lithuania and 0.7 kg in Morocco. Over the past year, the total amount of waste generated in Turkey, Lithuania, and Morocco was 68,397.909 tons, 17,033.649 tons, and 21,418.114 tons, respectively. Based on these data, the average daily waste generation was calculated to be approximately 187.34 tons in Turkey, 46.64 tons in Lithuania, and 58.67 tons in Morocco. Similarly, the average monthly waste generation was estimated to be around 5699.83 tons in Turkey, 1419.47 tons in Lithuania, and 1784.84 tons in Morocco. These calculations are based on annual data provided by relevant official institutions and have been further classified by the researchers according to waste types. This detailed quantification allows for a clearer understanding of waste generation amounts across the three countries [38,39,40]. The detailed amounts of waste generated for each type of waste are presented in Table 2 below.

Table 2.

Annual average of different waste types and the amount.

The data in the table indicate that, during the participation in recreational activities, individuals in all three countries predominantly contribute to plastic waste production. Additionally, it highlights the significant production of glass, organic, and food waste. The differences in the amounts of waste generated can be attributed to factors such as the population sizes of the countries, the number of forested areas available for recreational activities, and the motivations for participating in these activities.

2.1.2. Calculating Carbon Footprint Process

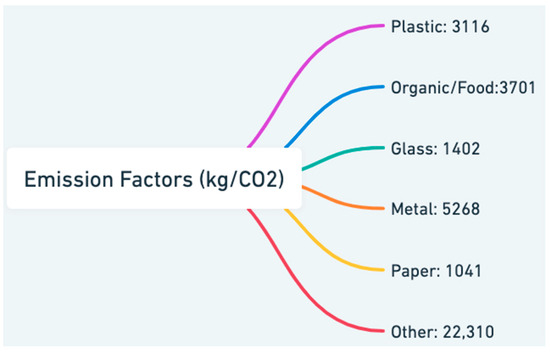

Over the past year, carbon footprint calculations have been carried out based on the types and amounts of waste produced during recreational activities in Turkey, Lithuania, and Morocco. The emission values used for each waste type in the carbon footprint calculation process are updated and published annually by the United Kingdom Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy. According to the published report, the emission values differ for each waste type, and therefore, plastic, organic/food, glass, metal, paper, and other waste emission values have been used in the calculations. The calculation formulas for each waste type have been prepared based on these emission values [41]. The emission values used for the waste types in the calculations are presented in Figure 2 below.

Figure 2.

Emission factors of waste type.

The emission values presented in Figure 2 above have been referenced, and formulas for carbon footprint calculations for each waste type have been created. The carbon footprint calculation formulas developed by Wicker (2018) have been adapted and refined to suit the objectives and scope of this study [42]. The updated calculation formulas based on the waste types and amounts are presented below:

2.1.3. Interview Process

The qualitative dimension of the study consists of interviews with experts in forest area management and recreation disciplines from Turkey, Lithuania, and Morocco. The qualitative research method focuses on the evaluation and analysis of expressions and words rather than quantitative data in studies [43,44]. It also provides opportunities to interpret a situation through existing phenomena via expressions and words. This allows for in-depth information on a particular topic within the scope of the research objectives To gain in-depth knowledge, the sample groups are intentionally kept limited in number [45,46,47].

The experts involved in the study were carefully selected based on professional experience and academic background criteria relevant to the scope of the research. The interview process was conducted through direct communication with the experts, and the obtained information was verified and confirmed. The items in the interview form were evaluated by the experts according to their knowledge and expertise, and the Content Validity Index (CVI) was calculated. The accepted threshold value for CVI is 0.78, and items scoring below this value were revised to enhance the validity of the form. Thus, the interview form was ensured to reflect expert opinions in a valid and reliable manner.

In this study conducted specifically in Turkey, Lithuania, and Morocco, data saturation was rigorously achieved. To ensure data saturation and reliability, recurring responses from the experts were examined using thematic analysis, and common patterns were identified [48]. In cases where responses or statements hindered the emergence of consistent themes, the response process to the relevant question was terminated, and the experts were instructed to proceed to the next question. This approach aimed to ensure meticulous consistency in coding the responses [49]. Additionally, to minimize bias during the analysis process, comparative methods were employed, and the analytical procedures were carefully monitored. These measures contributed to the objectivity of the study’s findings while also enhancing the reliability of the analyses [50].

2.1.4. Sample Group

In the study, purposive sampling was used to form the sample group to gain in-depth knowledge. In qualitative research, the interview method is a prerequisite for obtaining accurate and reliable information and findings [51,52]. The purposive sampling method was chosen in this research to obtain comprehensive, accurate, and reliable results. The decision to use purposive sampling was based on the criterion that the individuals in the interview group should have specific knowledge and experience relevant to the subject of the study [53,54,55]. Based on this criterion, the sample group consists of a total of 45 experts (15 from Turkey, 15 from Lithuania, and 15 from Morocco). The sample group includes professionals with expertise in the research topic, including lawyers (3), academics (3), forest area managers (3), recreation specialists (3), and individuals participating in recreational activities (3).

The research group consists of lawyers, academics, administrators, forest area managers, recreation specialists, and individuals participating in recreational activities. The inclusion of these expert groups was guided by their potential to contribute to the study’s objectives through their domain-specific knowledge and practical experience. Lawyers possess the theoretical knowledge and expertise necessary to interpret and evaluate the legal foundations of waste management processes. Academics, particularly those engaged in environmental research in recent years, offer intellectual contributions to the conceptual framework of the study. Forest area managers provide both theoretical and practical insights into waste generation, collection, and disposal, thus enriching the research with an applied managerial perspective. Recreation specialists, who are responsible for organizing and managing recreational activities in forest areas, have direct experience with waste-related issues and practices, thereby offering valuable reflections aligned with the research aims. Individuals participating in recreational activities represent both the source and potential solution to waste-related challenges, positioning them as fundamental actors in sustainable environmental management. Accordingly, the sample group was carefully selected to ensure alignment with the research objectives and sub-goals, with consideration given to their capacity to contribute meaningfully to the resolution of waste-related problems in forest environments through their expertise and experience.

To evaluate the validity of the interview form, the Item-Level Content Validity Index (I-CVI) and the Scale-Level Content Validity Index (S-CVI) were calculated for each item. Each item was presented to a total of 45 experts, equally from the three countries, and analyses were conducted based on the experts’ ratings of item relevance. The commonly accepted threshold value of 0.78 in the academic literature was used as a reference. As a result of the calculations, items 1, 2, and 6 demonstrated full validity with I-CVI values of 1.00. Item 5 met the validity criterion with a value of 0.80. Items 3 and 4, with values of 0.69 and 0.73, respectively, were found to be close to the threshold and considered acceptable. The S-CVI value calculated as the average of all items was 0.87, indicating that the interview form generally possesses a high level of content validity. The demographic characteristics of the sample group are presented in Table 3 below.

Table 3.

The demographic characteristics of the sample group.

2.1.5. Data Collection Tool

In this study, a semi-structured interview form was used as the data collection tool. The semi-structured interview form was prepared by the researchers and was subsequently reviewed and refined by experts in different fields and languages. After this process, the form was finalized and ready for the interviews. A semi-structured interview form was specifically designed by the researchers for the interviews. In qualitative research, semi-structured interview forms are used to obtain accurate, comprehensive, and in-depth information, as they allow for intervention during the interviews and facilitate easy guidance of the experts in accordance with the objectives of the study [56]. The questions included in the interview form used in this study are presented below:

- What types of waste are most commonly encountered during recreational activities in rural areas, and what are the underlying causes for their generation?

- What waste management practices are currently implemented in rural recreational areas in your country?

- Based on your experience, what deficiencies exist in the processes of waste collection, separation, or disposal in rural recreational spaces?

- How would you assess the level of public awareness and community participation in waste management in your country?

- In your opinion, what are the most significant administrative, legal, or structural challenges that hinder effective waste management in your country?

- What innovative solutions would you propose to improve waste management in rural recreational areas?

2.1.6. Analysis of Interview Data

For the analysis of data obtained from interviews with the experts from all three countries, the NVivo 14 analysis program was used. Descriptive and content analysis methods were employed in the analysis of the collected data, and expressions were transformed into findings. In qualitative research, the focus of analysis is not on numbers or quantitative data, but rather on the views and expressions of the experts, which need to be highlighted and converted into findings [57]. In this context, the views and responses of the experts from all three countries were transformed into findings and presented to the reader.

The data obtained from the interviews were evaluated using the descriptive analysis method. Descriptive analysis enables the systematic identification of the fundamental characteristics and patterns within the data [58]. Thus, the experts’ evaluations regarding waste management processes and innovative solution proposals were comprehensively revealed. In this process, qualitative coding was applied to systematically organize and interpret the data. Coding refers to the classification and categorization of raw data into specific themes or concepts [59]. This procedure facilitates the identification of patterns, relationships, and core meanings within the data. Consequently, expert opinions were classified and analyzed by the researchers, yielding comprehensive findings aligned with the study’s objectives.

3. Results

The presentation of the findings obtained in the study consists of two stages. In the first stage, carbon footprint (CF) calculations were conducted and presented to the reader based on the types and amounts of waste generated during recreational activities conducted in forested areas over the past year in Turkey, Lithuania, and Morocco. In the second stage, interviews were conducted with a total of 45 experts (15 from each country). The data obtained from these interviews were transcribed and analyzed using the content analysis method to derive findings, which were then presented to the reader. The findings were summarized and supported with tables for clarity.

3.1. Findings on Carbon Footprint

It has been determined that six different types of waste were generated during recreational activities conducted in forested areas over the past year (March 2024–March 2025) in Turkey, Lithuania, and Morocco. Based on the types and amounts of these wastes, the carbon footprint (CF) values for each country were calculated. The detailed results of these calculations are presented in Table 4 below.

Table 4.

Carbon footprint based on waste type and quantity.

Over the past year, carbon footprint calculations were conducted based on the types and quantities of waste generated during recreational activities in forested areas. According to these calculations, the total carbon footprint was estimated at 1517.26 kg for Turkey (52.92%), 613.25 kg for Lithuania (21.40%), and 735.68 kg for Morocco (25.67%). Turkey accounted for approximately 52.92% of the total carbon footprint. When examining the percentage distribution of waste types based on a total of 2866.19 kg, plastic waste accounts for the highest proportion at 35.26%. This is followed by organic/food waste at 30.95%, other waste types at 17.22%, metal waste at 10.56%, glass waste at 4.52%, and paper waste at 1.49%. The cumulative carbon footprint resulting from recreational activities in all three countries over the last year amounts to 2866.19 kg. Among the various types of waste, plastic waste emerged as the most significant contributor to carbon emissions, constituting 35.23% of the total carbon footprint across all three countries. This was followed by organic and food waste as the second-largest source.

3.2. Findings from Expert Opinions

In the qualitative dimension of the study, interviews were conducted with a total of 45 individuals from Turkey, Lithuania, and Morocco, including lawyers, academics, forest area managers, recreation experts, and individuals participating in recreational activities, with each possessing expertise relevant to the research topic. The findings obtained from these interviews are presented in this section.

As part of the research, the experts from all three countries were asked the following question: “What types of waste are most commonly encountered during recreational activities in rural areas, and what are the underlying causes for their generation?” According to the experts, the common types of waste observed across all three countries, as well as the primary causes of their generation, are presented in detail in Table 5 below.

Table 5.

The common types of waste and primary causes of their generation.

It can be stated that the types of waste generated during recreational activities in Turkey, Lithuania, and Morocco are generally similar. Plastic materials, glass bottles, and food packaging emerge as the most common waste types across all three countries. However, it is particularly notable that in Morocco, cigarette butts and plastic bags are frequently and extensively discarded into the environment.

The underlying causes of waste generation appear to be consistent across the three countries. A lack of education and awareness, insufficient infrastructure in recreational areas, and the tendency of participants to prefer single-use and convenience-oriented products are identified as the primary factors. Moreover, the experts from all three countries provided comprehensive assessments regarding both the types of waste generated and the underlying causes of their emergence.

“The use of plastic bottles is very common in Turkey, and due to the lack of effective recycling practices, people tend to discard them into the environment. Unfortunately, this is something we observe frequently. Pollution and adverse effects on nature are evident, mainly due to a lack of education and insensitivity towards environmental issues.” (Academics from Türkiye). “Smoking is very common in Morocco, and people often extinguish their cigarettes and throw them on the ground. It does not matter whether it is a forested area or an urban center. Unfortunately, we are a society lacking awareness, and cigarette butts can be seen everywhere—whether during recreational activities or sports events.” (Participants/Recreation Expert from Morocco). “Although recycling practices exist in Lithuania, it is still common to see plastic bottles littered in forest areas. Additionally, since packaged food is easy to carry and use, food packaging waste is also frequently discarded by individuals. I believe that the lack of waste bins and insufficient infrastructure in forested areas plays a significant role in this issue.” (Participant from Lithuania).

As part of the research, the experts from all three countries were asked the question: “What waste management practices are currently implemented in rural recreational areas in your country?” According to expert opinions, similar waste management processes and practices are implemented across all three countries. These practices are presented in detail in Table 6 below.

Table 6.

Waste management practices in the countries.

In all three countries, the experts reported the presence of waste bins and recycling containers in forested areas, as well as regular waste collection and recycling processes. However, a common view among the respondents is that these measures remain insufficient across all countries. In particular, the experts emphasized the inadequacy of recycling practices in Lithuania, the lack of waste and recycling bins in Morocco, and the overall insufficiency of recycling practices in Turkey. A closer examination of expert opinions reveals the following:

“Recycling practices in Turkey are quite weak. People also fail to demonstrate the necessary sensitivity. Although legal regulations regarding this issue have been increasingly discussed in recent times, the measures taken are still highly inadequate.” (Lawyer from Turkey). “Perhaps the most challenging part of forest area management is dealing with waste. Although these wastes are collected at regular intervals, we still need more waste bins and separation points. I also believe that people do not show the necessary awareness in this regard, and I am somewhat pessimistic about this issue.” (Forest Manager from Morocco). “In Lithuania, you can see numerous recycling and separation points in urban centers, but the situation is more problematic in forested areas. Yes, there are waste bins, but they are insufficient. Moreover, these wastes need to be collected more frequently; otherwise, they get scattered around. Sometimes animals spread them further, making it even harder to collect, and ultimately, they are left in nature.” (Forest Manager from Lithuania).

In the research, the experts from all three countries were asked, “Based on your experience, what deficiencies exist in the processes of waste collection, separation, or disposal in rural recreational spaces?” According to expert opinions, the deficiencies observed in waste collection, separation, or disposal processes in each of the three countries are presented in Table 7 below.

Table 7.

Deficiencies in the processes of waste collection, separation, or disposal.

It is observed that the problems related to waste management processes are common in Turkey, Lithuania, and Morocco. Issues such as the untimely collection of waste, an insufficient number of staff, a lack of separation and recycling points, and the insufficient involvement of the private sector in this process are emerging in all three countries. The necessity of frequent waste collection in forested areas, the widespread establishment of separation and recycling points similar to those in city centers, and the reduction of the public sector’s workload in this field through the involvement of the private sector are recommended.

The most significant issue in Turkey’s process is the insufficient number of workers dedicated to protecting forested areas and maintaining cleanliness in the environment. As a result, waste cannot be collected on time and becomes a major problem (Forest Manager from Turkey). There are very few trash bins, and there are no separate areas for waste separation. These issues can be considered as the most basic deficiencies (Recreation Expert from Turkey). Furthermore, in my opinion, it is very reasonable to handle this task through the private sector. This would bring competition, and the public administration would be relieved of this burden (Academic from Turkey). The recreational use of forested areas is quite important, but one of the main problems is the failure to remove waste and trash on time during the usage process. When trash is not collected on time, it is scattered by animals, leading to pollution (Recreation Expert from Lithuania). Separation and recycling machines should also be present in forested areas. Almost every city and many markets have these machines, and our city centers are quite clean. However, it is difficult to say the same for forested areas (Academic from Lithuania). In Morocco, the most significant deficiency is timing. Waste and trash sometimes stay for very long periods, although they need to be collected on time and used for recycling. However, I can also say that recycling practices are insufficient (Forest Manager from Morocco). I have led many recreational activities, and I have said repeatedly that these areas need more trash bins, but no solution has been found yet (Recreation Expert from Morocco). These waste materials need to be separated and collected regularly. This could also contribute to the country’s economy. Products made from recycling are becoming increasingly widespread around the world, so we need to implement recycling and separation practices (Academic from Morocco).

In the research, the experts from all three countries were asked the following question: “How would you assess the level of public awareness and community participation in waste management in your country?” Below are the experts’ views on public awareness and community participation in waste management in Turkey, Lithuania, and Morocco.

Experts from Turkey, Lithuania, and Morocco report that public awareness in their respective countries is insufficient, and as a result, participation in the process of achieving clean environment goals is very low. They emphasize that awareness and consciousness regarding the protection of forested areas are also significantly low.

In Turkey, there are many forested areas open to recreational activities, and these activities have seen a significant increase in participation in recent years. However, it can be said that awareness regarding the protection of forested areas has been steadily decreasing in parallel with this increase in participation. (Forest Manager from Turkey). In forested areas, especially with the mindset of “no one will see me,” people are throwing their trash around, and this situation is becoming more widespread. (Recreation Expert from Turkey). In Lithuania, there is almost nothing being done to protect the environment. It’s unbelievable. Awareness and consciousness are decreasing, especially among the youth, and I don’t understand why. (Academic from Lithuania). There is a need to increase community participation, and we must focus on information and awareness campaigns. Especially the youth are behaving indifferently and have a very low level of participation. (Lawyer from Lithuania). The fundamental issue is being sensitive to the environment! This needs to be achieved, but there is a lack of knowledge and awareness regarding the destruction or protection of the environment. (Participant from Lithuania). In Morocco, environmental education should start in schools, teaching what needs to be done to protect our environment. In my opinion, apathy is a global problem, and we feel it more intensely in Morocco. (Academic from Morocco). Our people don’t have concerns about the environment; they are unaware of the future that is being lost. They should understand that forests and the environment we live in are our future, and we should act accordingly. (Forest Manager from Morocco).

In the research, the experts from all three countries were asked the question, “In your opinion, what are the most significant administrative, legal, or structural challenges that hinder effective waste management in your country?” According to the experts, the administrative, legal, or structural challenges that hinder effective waste management in each country are presented in Table 8 below.

Table 8.

Administrative, legal and structural challenges for waste management.

It is observed that the administrative, legal, and structural challenges related to the existing waste management processes in Turkey, Lithuania, and Morocco are common. The most prominent issue is the insufficiency of legal regulations. Additionally, in Turkey, the lack of sufficient human and financial resources has been identified as a major challenge. Other shared issues include the insufficient number of staff, the lack of public awareness, and inadequate inter-institutional collaboration.

There is a cost to waste collection. Employees, vehicles used, etc. It is an important task, and I believe that the necessary resources are not allocated for this in Turkey. (Forest Manager from Turkey). Laws. In public administration, the most important tool is laws. In our country, legal regulations regarding environmental protection, waste collection, etc., are very insufficient. Additionally, the reluctance of employees makes it even harder to implement existing laws. (Lawyer from Turkey). Our people are not doing enough to protect these forests. They leave by throwing their trash around. It’s a shame! (Participants from Turkey). There is a specific law for forest areas in Lithuania. However, it is insufficient and needs to be renewed and updated. These laws should be more deterrent for those harming the forests; they should be stricter. (Lawyer from Lithuania). You cannot solve waste management issues with just one institution or a single law. You need cooperation, help, and support from other relevant institutions, but in our country, this cooperation is very weak and insufficient. (Academic from Lithuania). The most important point for protecting forest areas and eliminating waste is to raise awareness so that people do not produce waste in the first place. They should know that littering is wrong and should act accordingly. This should be taught in schools. (Academic from Morocco). Due to the intense participation in recreational activities, the accumulation of trash is normal, but more personnel and cooperation are needed to collect and recycle them. (Forest Manager from Morocco). New and updated laws are needed. The power of laws should be utilized. (Lawyer from Morocco).

The experts from all three countries were asked the question, “What innovative solutions would you propose to improve waste management in rural recreational areas?” According to the expert opinions, the necessary innovative solution proposals to improve waste management in each country are presented in Table 9 below.

Table 9.

Innovative solutions for the waste management process.

It is observed that experts from Turkey, Lithuania, and Morocco take into account the deficiencies in their respective countries while proposing solutions to improve waste management processes. In Turkey, the need for the use of digital tools, stricter supervision, an increase in the number of personnel and waste bins, and the promotion of volunteer work are emphasized. In Lithuania, the focus is on education and awareness campaigns, updating legal regulations, placing recycling bins, improving infrastructure, and promoting environmentally friendly projects. In Morocco, the experts highlight the need for increased sanctions, updated legal regulations, more personnel, more frequent waste collection, and the significance of educational activities.

“In my opinion, digital tools should be used in forested areas as they are in all other fields. This would make monitoring and supervision much easier. Digitalization is applied in every field today.” (Forest Manager from Turkey). “We are quite insufficient in terms of numbers. More personnel are needed. This way, we can also conduct inspections manually.” (Forest Manager from Turkey). “We are a country rich in forested areas. There is a law regarding forests, but it is very old. A new and updated legal regulation has become inevitable.” (Lawyer from Lithuania). “Since children start school, we should subject them to strict education and awareness campaigns about the environment. This way, consciousness and awareness can be increased.” (Academic from Lithuania). “Recreational activities provide an excellent opportunity for environmental projects and activities. By organizing environmentally conscious events, participation and awareness can be increased. This will naturally help protect forested areas.” (Recreation Expert from Lithuania). “We can take advantage of the power of laws and sanctions. People are very indifferent and behave negligently, thinking there is no punishment. New laws can be enacted, and penalties can be increased.” (Lawyer from Morocco). “People constantly come and go, and naturally, a lot of waste and garbage is generated. These need to be collected more frequently; otherwise, as they accumulate, they spread and cause more pollution.” (Recreation Expert from Morocco).

4. Discussion

Recreational activities conducted in forested areas and natural environments have a significant impact on individuals’ physical, mental, and social health. The creation of social environments, being immersed in nature, and similar factors enhance the positive effects of recreational activities on both individuals and society [60,61]. However, the increasing participation and demand for these activities also bring about environmental issues. The waste generated due to the high levels of human participation in these activities is considered a threat to environmental sustainability. These wastes accelerate greenhouse gas emissions and contribute to the growth of carbon footprints [62].

In the context of the study, the carbon footprints resulting from recreational activities held in forested areas in Turkey, Lithuania, and Morocco were calculated. According to the calculations, the carbon footprint generated in Turkey over the past year was 1517.26 kg, in Lithuania it was 613.25 kg, and in Morocco it amounted to 735.68 kg. The carbon footprint originating from Turkey constitutes 52.92% of the total. The total carbon footprint arising from recreational activities in all three countries during the past year is 2866.19 kg. The most significant factor contributing to the overall carbon footprint is plastic waste. In all three countries, plastic waste is identified as the primary source of carbon footprint, accounting for 35.23%. Organic food waste follows as the next significant contributor.

According to the research findings, plastic waste emerges as the primary factor contributing to the formation and growth of carbon footprints. Plastic waste is known for its long-lasting presence in the environment, with its effects persisting for many years.

From production to recycling, the process of plastic materials generates significant amounts of greenhouse gas emissions. Additionally, due to their prolonged life cycle, certain types of plastics can remain in the natural environment for hundreds of years, and their negative environmental impacts can last for an extended period [63,64]. The long persistence of plastic waste in the natural environment also directly impacts ecosystems, and in particular, it can pose a major risk to ecosystems found in forested areas [65,66,67]. Furthermore, the environmental impact of plastics can be doubled due to high energy consumption during their production processes. Therefore, it is crucial to protect forested areas from plastic waste and promote recycling practices [68,69,70,71].

Compared to Lithuania and Morocco, Turkey exhibits a significantly higher carbon footprint, with plastic waste being the main contributor to this footprint. A study on plastic waste in Turkey’s forested areas highlights the long lifespan of plastic waste and underscores its considerable impacts on nature, ecosystems, and biodiversity [72,73,74]. The primary reason for the frequent occurrence of plastic waste in Turkey is the insufficient recycling practices. According to the Ministry of Environment and Urbanization of the Republic of Turkey, only 12% of plastic waste is recycled [75]. This situation leads to the prolonged presence of plastic waste in nature and the escalating impact of these materials.

Another significant contributor to the carbon footprint is organic or food waste. In recent years, organic waste has become an important risk factor for environmental sustainability goals. Increasing consumption has led to the growing prevalence of this type of waste [76,77,78]. When food waste is left to accumulate with other trash in waste collection areas, it can become a source of methane emissions. Methane gases, in turn, can have nearly 25 times more harmful effects than carbon gases [79]. In each of the three countries, plastic waste emerges as a primary source of carbon footprints, followed by organic and food waste. In this context, it can be said that the starting point of waste management in Turkey, Lithuania, and Morocco should be plastic waste, with a central focus on recycling practices.

Interviews were conducted with experts from Turkey, Lithuania, and Morocco for this research. Based on the findings from these interviews, it can be stated that the types of waste produced during recreational activities are generally similar across the three countries. Plastic, glass bottles, and food packaging are prominent in all three countries. However, in Morocco, it was noted that cigarette butts and plastic bags are frequently and heavily discarded in the environment. The main reasons for waste production in all three countries are the same. Particularly, the lack of education and awareness, the need for infrastructure in recreational areas, and participants’ preference for single-use and convenient products are key factors.

The similarity in the types of waste generated during ongoing recreational activities in forested areas in Turkey, Lithuania, and Morocco highlights the cultural and environmental similarities. However, the widespread use of cigarette butts and plastic bags in Morocco, particularly related to cigarette consumption, distinguishes it from the other two countries and represents another dimension of environmental threat, shedding light on the lack of environmental awareness [80,81,82]. Environmental issues arising from the disposal of cigarette butts are considered a distinct environmental problem for developing countries [83,84]. This difference in Morocco can also be linked to the country’s culture and the high prevalence of smoking.

Although the types of waste generated during recreational activities in forested areas show similarities across Turkey, Lithuania, and Morocco—such as food packaging, beverage containers, and organic materials—country-specific patterns also reveal important socio-cultural differences. For instance, the high prevalence of cigarette butts and plastic bags in Morocco, as compared to the other two countries, reflects a distinct environmental threat that stems not only from individual behavior but also from broader societal norms regarding public space cleanliness and environmental responsibility. This finding may indicate lower levels of environmental awareness or weaker enforcement of anti-littering regulations in Morocco. In contrast, Turkey and Lithuania, despite generating similar waste types, demonstrate relatively higher adherence to waste management practices, possibly due to stronger institutional structures or more established public environmental education campaigns. These differences underscore the importance of tailoring waste reduction strategies to the specific socio-cultural and legal contexts of each country.

Plastic waste generated from global plastic use is considered one of the most significant waste problems worldwide [85,86]. The widespread production of single-use packaging, often made from plastic, exacerbates this issue. Moreover, steps taken by developing countries towards recycling plastic waste are often insufficient [87,88,89]. For instance, in Turkey, plastic waste is identified as the most produced type of waste in recreational areas, and its environmental impacts are steadily increasing. This issue is primarily driven by the lack of environmental awareness and people’s preference for single-use plastic products. Additionally, the irregular collection of these waste materials and their disposal in the environment further intensifies their environmental impact [90,91].

There are common issues related to waste management processes in Turkey, Lithuania, and Morocco. Problems such as the untimely collection of waste, insufficient workforce, lack of sorting and recycling points, and insufficient involvement of the private sector in the process are observed in all three countries. The underlying causes of these shared problems acquire meaning within the context of each country’s distinct socio-cultural, legal, and infrastructural characteristics. For instance, in Turkey, a noticeable gap exists between the limitations imposed by local government regulations and the level of public environmental awareness. In Lithuania, although institutional capacity appears to be stronger, individual environmental behaviors do not meet expectations. In Morocco, both the inadequacy of legal infrastructure and the weakness of collective responsibility related to environmental awareness contribute to a more severe manifestation of these issues. In this regard, while waste management problems may appear similar on the surface, the contextual specificities of each country significantly shape the nature, intensity, and potential solutions to these challenges.

In developing countries, the infrequent collection of waste and garbage is considered a potential issue. In Turkey, there are disruptions in the waste collection processes, and even in large cities, this problem is occasionally encountered. A study conducted by Avşar (2024) highlights that waste and garbage are not collected on time even in major cities, such as Istanbul and Ankara, which results in environmental risks [92]. In Lithuania, especially during the tourism season, an increase in human activity leads to a rise in waste and garbage, causing disruptions in their collection and disposal processes [93,94]. In Morocco, inadequate infrastructure is a major issue in waste collection processes. There is a shortage of equipment and human resources for transporting waste and delivering it to designated areas [95].

In addition to the transportation of waste, the recycling processes of waste and garbage are another challenge for all three countries. For instance, in Turkey, as one moves further away from metropolitan areas, particularly in rural and inland cities, the understanding and awareness of recycling are still not well established. According to a report on recycling processes in Turkey, the recycling rate is only 13% of the total waste volume [96]. In Lithuania, a similar situation is observed. The recycling infrastructure in Lithuania can be considered inadequate, and public awareness of the issue is also relatively weak. In Morocco, the infrastructure for waste separation and recycling is known to be problematic. The findings of the research reveal that the private sector has remained insufficient in managing recycling processes across all three countries. A similar situation is observed in both Lithuania and Morocco. In Lithuania, the involvement of the private sector in recycling processes is quite limited. In Morocco, recycling processes are managed by the state, and private sector initiatives are extremely limited [97,98].

The study reveals that the main issues related to waste management in Turkey, Lithuania, and Morocco stem from administrative, legal, and structural challenges. The most prominent issue, in particular, is the inadequacy of legal regulations. Additionally, it appears that problems arise in Turkey due to insufficient financial resources allocated for waste management. Other concerns include the shortage of staff and insufficient inter-institutional cooperation. However, the nature and impact of these issues vary across countries. In the case of Turkey, deficiencies in legal regulations are accompanied by shortcomings in the allocation of financial resources. This situation can be directly linked to Turkey’s unique structural and political conditions concerning economic priorities, budget planning, and the distribution of public funds. Furthermore, the insufficient number of personnel and the lack of inter-institutional coordination stem from the centralized nature of public administration in Turkey as well as its cultural and structural characteristics related to institutional functioning.

On the other hand, although similar administrative and structural barriers exist in the contexts of Lithuania and Morocco, these countries differ from Turkey in terms of their legal infrastructure capacity, public resource management, and institutional cooperation dynamics. For example, in Lithuania, the process of aligning with European Union standards emerges as a significant factor in strengthening legal regulations and diversifying financing models. In Morocco, socio-cultural factors, alongside deficiencies in infrastructure investments, are more pronounced, which can be associated with the local governance structures and the level of public awareness within the country. Within this framework, addressing waste management challenges necessitates an examination of the socio-cultural, legal, and economic infrastructures of the respective countries and the development of context-specific policy recommendations. In the subsequent sections of this study, proposals aimed at enhancing institutional cooperation models and legal regulations will be presented, taking into account the specific needs and strengths of each country based on these contextual differences.

Weak legal foundations and deficiencies in implementation may pose significant obstacles to achieving environmental sustainability goals. Buzkan and Erman (2020) state that although there are legal regulations regarding waste management in Turkey, their implementation and enforcement remain inadequate [99]. A similar situation exists in Lithuania, which operates within the framework of European Union legislation; however, due to the lack of enforcement and insufficient deterrence, these laws fail to yield effective results [100]. Morocco also faces a comparable issue, with scholars noting that legal regulations concerning waste management are highly insufficient [101].

The core of the research focuses on identifying innovative solutions for waste management in forested areas. In this context, experts from Turkey, Lithuania, and Morocco were asked about potential innovative solutions. According to the findings;

In Turkey, the opinion that digital tools should be utilized, inspections should be tightened, the number of staff and waste bins should be increased, and volunteer work should be promoted is predominant. In Lithuania, the emphasis is on education and awareness programs, updating legal regulations, placing recycling bins, improving infrastructure, and supporting environmentally friendly projects. In Morocco, the need to increase penalties, update legal regulations, increase personnel, collect waste more frequently, and enhance educational activities is highlighted.

The findings, based on the perspectives of experts from Turkey, Lithuania, and Morocco, indicate that the proposed solutions are shaped by each country’s unique socio-cultural, legal, and infrastructural contexts. In Turkey, measures such as the utilization of digital technologies, tightening of inspection mechanisms, enhancement of human resources, expansion of waste collection equipment, and the promotion of volunteer activities are emphasized. These recommendations reflect the structural deficiencies and institutional capacity challenges within Turkey’s current waste management system.

In Lithuania, strategies focusing on education and awareness programs, updating legal frameworks, strengthening recycling infrastructure, and supporting environmentally friendly projects are gaining prominence. This can be attributed to Lithuania’s alignment with European Union standards and its commitment to environmental sustainability policies. In the context of Morocco, priority solutions include increasing enforcement measures, implementing updated legal regulations, augmenting personnel capacity, increasing the frequency of waste collection, and expanding educational activities. These suggestions are closely linked to Morocco’s local governance structures, socio-cultural dynamics, and shortcomings in infrastructural investments. Within this framework, there emerges a clear necessity to develop innovative waste management strategies that are multidimensional, participatory, and tailored to the specific conditions of each country.

In Turkey, with the advancements in technology, the use of digital tools in waste management has gained significant attention. It is foreseen that digital equipment could facilitate monitoring and control, thereby improving waste management processes [102,103,104]. Furthermore, establishing digital infrastructures such as smart cities could improve waste and garbage collection processes [105]. In Lithuania, the most important motivation for clean environment goals is the European Union legislation. According to this legislation, the aim is to popularize recycling practices, implement projects, and conduct training on environmental sustainability. This could increase awareness and societal participation [106]. Additionally, through the National Waste Prevention and Management Plan, Lithuania aims to ensure that at least 60% of the generated waste is made recyclable. Full participation of local government units is targeted in this process. In addition to legal practices, environmental education is emphasized, with informational and awareness-raising goals in schools. Under the “Green Literacy” project, environmental education is provided in all schools to raise societal awareness [107].

Morocco faces challenges in carrying out inspections, updating legal regulations, and enforcing penalties in waste management processes. Furthermore, the country lacks sufficient experience in societal awareness and participation [95,108]. In recent years, the World Bank has been providing financial support to improve waste management processes in Morocco, aiming to increase both the quantity and quality of personnel [109]. Through this, it is expected that waste collection will become more frequent, recycling will be promoted, and waste management processes will be improved for cleaner environmental goals [98].

Integrating innovative solutions into waste management, promoting recycling practices, allocating more financial resources, and increasing the number and quality of personnel are key innovative solutions. Improving waste management processes in all three countries can be influenced by integrating these proposals, strengthening legal foundations, and, of course, enhancing societal participation. In particular, societal participation can significantly impact the effectiveness of all these proposed solutions. In this context, supporting educational initiatives and projects, promoting awareness-raising efforts, and expanding public and private sector collaborations are of utmost importance.

5. Conclusions

Due to the increasing demand for recreational activities, significant amounts of waste are being generated by individuals. To minimize the environmental impacts of this waste, it is of great importance to implement necessary precautionary measures and ensure compliance by relevant individuals, institutions, and organizations. In this context, the aim of the present study is to calculate the carbon footprint resulting from waste generation during recreational activities conducted in forested areas in Lithuania, Turkey, and Morocco, and to identify innovative waste management strategies to promote a safe and clean environment within forest ecosystems.

To achieve this objective, carbon footprint calculations were first conducted based on the type and amount of waste generated during recreational activities in the three countries. Subsequently, to identify the challenges in waste management processes and to propose innovative solutions to these problems, semi-structured interviews were conducted with a total of 45 experts from the three countries.

The carbon footprint calculations are based on the type and amount of waste generated during recreational activities held in forested areas in Turkey, Lithuania, and Morocco over the past year.

The carbon footprint resulting from waste generation was estimated to be 1517.26 kg in Turkey, 613.25 kg in Lithuania, and 735.68 kg in Morocco. Of the total carbon footprint, 52.92% originated from Turkey. The overall carbon footprint resulting from recreational activities across the three countries over the past year amounted to 2866.19 kg. Plastic waste was identified as the most significant contributor to the total carbon footprint in all three countries, accounting for 35.23% of the total. This was followed by organic food waste, which also constituted a notable share.

The relatively large carbon footprint observed in Turkey—constituting more than half of the total carbon footprint across the three countries—can be attributed to several factors, including the country’s extensive land area, significantly larger population compared to the other countries, more widespread forested regions, and a higher number of participants engaging in recreational activities. Nevertheless, plastic waste emerges as the most prominent contributor to the carbon footprint in all three countries.

To identify the challenges related to waste management processes and propose innovative solutions, semi-structured interviews were conducted with a total of 45 experts from Turkey, Lithuania, and Morocco. Based on the findings obtained from these interviews, several key observations were made.

It can be stated that the types of waste generated during recreational activities are largely similar across Turkey, Lithuania, and Morocco. In all three countries, plastic materials, glass bottles, and food packaging are the most commonly observed waste types. However, in Morocco, cigarette butts and plastic bags are more frequently and intensely discarded in natural environments compared to the other two countries.

The underlying causes of waste generation appear to be consistent across the three nations. The primary contributing factors include a lack of education and environmental awareness, insufficient infrastructure in recreational areas, and a preference for single-use, convenience-oriented products among visitors.

Moreover, common challenges regarding waste management were identified across Turkey, Lithuania, and Morocco. These challenges include the untimely collection of waste, an insufficient number of personnel, a lack of waste sorting and recycling facilities, and inadequate involvement of the private sector in waste management processes. To address these issues, it is recommended that waste collection in forested areas be conducted more frequently, that sorting and recycling facilities be expanded in a manner similar to those in urban centers, and that the involvement of the private sector be enhanced to alleviate the administrative burden on public authorities.

It is evident that Turkey, Lithuania, and Morocco share common administrative, legal, and structural challenges in their current waste management processes. Among these, the most prominent issue appears to be the inadequacy of existing legal regulations. In addition, it is understood that Turkey faces specific difficulties due to insufficient human and financial resources. Other commonly identified challenges include the lack of adequate personnel, limited public awareness, and insufficient levels of inter-institutional cooperation.

Experts from Turkey, Lithuania, and Morocco have proposed innovative solutions for improving waste management systems in their respective countries, taking into account the specific deficiencies observed in each context. In Turkey, the most emphasized recommendations include the increased use of digital tools, stricter enforcement and monitoring, increasing the number of personnel and waste bins, and promoting volunteerism. In Lithuania, the need for education and awareness-raising initiatives, updates to legal frameworks, installation of recycling bins, infrastructure development, and implementation of environmentally friendly projects are highlighted. In Morocco, the focus is placed on strengthening enforcement mechanisms, updating legislation, increasing personnel numbers, ensuring more frequent waste collection, and enhancing educational activities.

This study identifies the environmental issues arising in forested areas with the overarching goal of promoting a clean and safe environment. In line with this goal, it provides solution-oriented recommendations based on expert opinions. By integrating qualitative data with quantitative findings—specifically carbon footprint measurements—the study adopts a mixed-methods approach aimed at generating both theoretical insights and practical interventions. Future research may be expanded to include more countries and broader datasets. It is also suggested that further studies consider regional and contextual variables and increase the number of expert participants to produce more comprehensive and generalizable results.

This study reveals numerous similarities concerning the environmental issues arising from waste generation in Turkey, Lithuania, and Morocco. However, it also demonstrates that waste management processes in all three countries are influenced by their distinct socio-cultural, legal, and infrastructural characteristics. In Turkey, despite a growing awareness of environmental issues, infrastructural deficiencies in recreational areas within forested zones hinder the effectiveness of waste separation and recycling processes. Lithuania, benefiting from the regulatory framework associated with its European Union membership, implements more systematic environmental policies, and due to a relatively higher level of institutional compliance, waste management processes in forested areas are conducted more efficiently. In Morocco, although national environmental strategies exist, the implementation of waste reduction initiatives in recreational forest areas remains limited due to infrastructural shortcomings and low environmental awareness in certain communities.

These differences underscore that local governance structures, societal environmental attitudes, and infrastructural capacities directly impact the success of waste management interventions. A comprehensive understanding of these contextual factors is critical, moving beyond generalized policy recommendations towards the design of innovative and context-specific strategies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.A., L.S. and D.P.; methodology, A.A.; validation, D.P., L.S., M.A. and M.Š.; formal analysis, L.S. and A.A.; investigation, L.S. and M.Š.; resources, M.A.; data curation, D.P.; writing—original draft preparation, M.Š.; writing—review and editing, M.A.; visualization, D.P.; supervision, A.A.; project administration, A.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study did receive ethical approval. The research protocol was reviewed and approved at the beginning of the project by the Research Ethics Committee of Ardahan University 7 May 2025. At the time, the specific approval number was E-67796128-819-2500015243 issued by the committee.

Data Availability Statement

The data sets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding authors on reasonable request. The participant consent form and the ethics committee approval are also attached herewith.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Cucek, L.; Klemes, J.J.; Kravanja, Z. A review of footprint analysis tools for monitoring impacts on sustainability. J. Clean. Prod. 2012, 34, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ress, S.; Kendall, N.; Friedson-Ridenour, S.; Ampofo, Y.O. Representations of humans, climate change, and environmental degradation in school textbooks in Ghana and Malawi. Comp. Educ. Rev. 2022, 66, 599–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Kumar, S. Impact of environmental degradation on life expectancy: Evidence from Asia. J. Energy Environ. Policy Options 2022, 5, 30–38. [Google Scholar]

- Vienažindienė, M.; Perkumienė, D.; Atalay, A.; Švagždiene, B. The last quarter for sustainable environment in basketball: The carbon footprint of basketball teams in Türkiye and Lithuania. Front. Environ. Sci. 2023, 11, 1197798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]