Abstract

Blue carbon ecosystems, particularly mangroves, seagrasses, and salt marshes, play a crucial role in climate regulation by capturing and storing huge stocks of carbon. Together with supporting fisheries production, protecting shorelines from erosion, and supplying timber and non-timber products to communities, blue carbon ecosystems offer investment opportunities through carbon markets, thus supporting climate change mitigation and sustainable livelihoods. The current study assessed above- and below-ground biomass, sediment carbon, and the capacity of the blue carbon ecosystems in Kwale and Lamu Counties, Kenya, to capture and store carbon. This was followed by mapping of hotspot areas of degradation and the identification of investment opportunities in blue carbon credits. Carbon densities in mangroves were estimated at 560.23 Mg C ha−1 in Lamu and 526.34 Mg C ha−1 in Kwale, with sediments accounting for more than 70% of the stored carbon. In seagrass ecosystems, carbon densities measured 171.65 Mg C ha−1 in Lamu and 220.29 Mg C ha−1 in Kwale, values that surpass the national average but are consistent with global figures. Mangrove cover is declining at 0.49% yr−1 in Kwale and 0.16% yr−1 in Lamu, while seagrass losses in Lamu are 0.67% yr−1, with a 0.34% yr−1 increase in Kwale. Under a business-as-usual scenario, mangrove loss over 30 years will result in emissions of 4.43 million tCO2e in Kwale and 18.96 million tCO2e in Lamu. Effective interventions could enhance carbon sequestration from 0.12 to 3.86 million tCO2e in Kwale and 0.62 to 19.52 million tCO2e in Lamu. At the same period, seagrass losses in Lamu would emit 5.21 million tCO2e. With a conservative carbon price of 20 USD per tCO2e, projected annual revenues from mangrove carbon credits amount to USD 3.59 million in both Lamu and Kwale, and USD 216,040 for seagrass carbon credits in Lamu. These findings highlight the substantial climate and financial benefits of investing in the restoration and protection of the two ecosystems.

1. Introduction

Mangroves, seagrasses, and tidal marshes are key coastal ecosystems renowned for their unmatched carbon sequestration and storage potential [1,2]. These blue carbon ecosystems (BCEs) offer a variety of essential products and are gaining greater acceptance as essential allies in addressing climate change and biodiversity loss challenges around the world [3,4]. Although BCEs occupy less than 1% of the total ocean surface, they are responsible for sequestering an estimated 50% to 70% of the ocean’s carbon reservoir [5]. Their protection and sustainable use could contribute as much as 21% of the total emissions cuts required by 2050 to maintain the global temperature increase within the 1.5 °C threshold [6]. Despite their importance, BCEs are disappearing at a global annual rate ranging from 0.3% to 7% [7,8,9], far exceeding the estimated 0.5% yearly loss of tropical forests [10].

The degradation of these ecosystems not only impairs their carbon storage potential but also leads to the release of previously captured carbon into the atmosphere, intensifying the effects of climate change [11,12]. In addition to their role in long-term carbon sequestration, BCEs provide vital ecosystem services, such as coastal defense, food and livelihood resources, raw materials, and enhancement of water quality [13,14]. The decline in coastal fisheries and the diminished resilience of coastal communities have been directly linked to their loss and degradation [1,15]. Stakeholders have responded by developing restoration projects aimed at preserving BCEs for the sake of biodiversity preservation, sustainable livelihoods, and the benefits of mitigating and adapting to climate change [1]. In recognition of these attributes, nations have included blue carbon in their national development and climate change agendas [16,17].

Mangroves and seagrasses represent the primary blue carbon ecosystems along Kenya’s coastline. While they deliver a wide range of ecological and socioeconomic benefits, these vital habitats continue to experience degradation and decline due to a combination of anthropogenic pressures and natural disturbances. At least 40% of mangroves in Kenya were lost between 1996 and 2015 [18]. Although the rate of loss is reported to be declining, localized overharvesting of mangroves for construction materials and energy remains a common problem along the coast [19,20].

In addition to their ecological importance, blue carbon ecosystems present valuable economic prospects through participation in carbon trading systems. The growth of voluntary carbon markets has created pathways for channeling financial resources toward the conservation and restoration of these ecosystems. Verified blue carbon projects can generate carbon credits, which may be sold to entities seeking to compensate for their greenhouse gas emissions, offering a long-term, community-driven funding solution for preservation activities. As global interest in high-integrity, nature-based carbon offsets grows, blue carbon is increasingly being incorporated into sustainable finance strategies, thereby appealing to climate-conscious investors and financiers. Furthermore, regulated carbon markets, such as national or regional cap-and-trade systems, are beginning to recognize the role of blue carbon in achieving emission reduction goals [21]. To enhance the financing landscape for blue carbon, innovative tools such as blue bonds and payment for ecosystem services (PES) are gaining momentum. In parallel, blended financing approaches, combining governmental, private sector, and philanthropic contributions, are under consideration to scale up investments in blue carbon conservation and climate resilience projects [22]. With increasing corporate commitments to achieving net-zero emissions, the blue carbon market stands as a critical pathway to unlocking climate finance while supporting biodiversity conservation and coastal resilience.

Despite these opportunities, Kenya has inadequate data and information on blue carbon stocks, their sequestration potentials, and emissions under different land-use scenarios. These knowledge gaps hinder evidence-based decision-making and limit access to carbon finance for local stakeholders. The current study aimed to evaluate blue carbon investment potential in Lamu and Kwale Counties, two coastal regions rich in BCEs. The objectives were to (a) assess the status, conditions, and trends of blue carbon ecosystems, and identify degradation hotspots in Kwale and Lamu Counties; (b) determine blue carbon stocks in biomass and soil; (c) estimate blue carbon sequestration rates and emission projections over the next 30 years; (d) estimate carbon credit potential for mangrove conservation, as well as reforestation, over the next 20 years in Kwale and Lamu Counties, Kenya. This study lays a foundation for informed planning, policy making, and investment in Kenya’s blue carbon landscape.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Description of the Study Area

Kenya’s coastline spans approximately 600 km, stretching between latitudes 1°40′S and 4°25′ S, and longitudes 41°34′ E and 39°17′ E. Along this stretch, mangroves are a common feature in creeks, sheltered bays, lagoons, and estuaries of major rivers (Figure 1). As outlined in [18], Kenya’s mangrove cover is estimated at 61,271 ha, comprising 9 species. Kwale and Lamu Counties constitute over 70% of the total mangroves in Kenya [18].

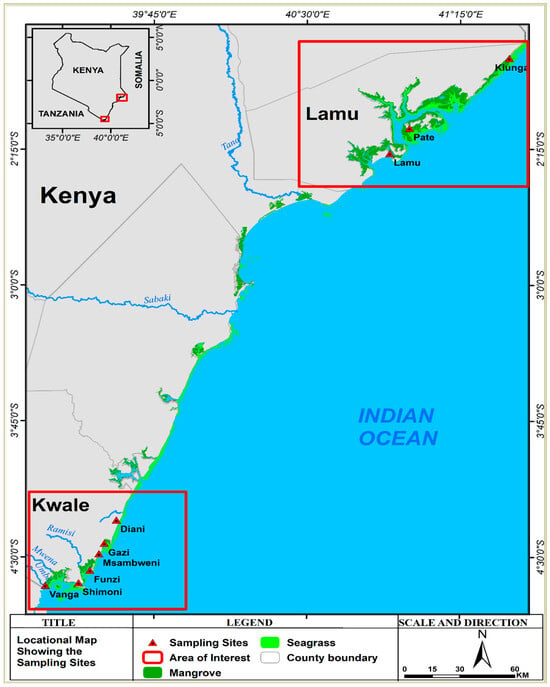

Figure 1.

Map showing mangrove and seagrass distribution in Kenya.

Another common feature along the coast is the seagrass beds. In Kenya, these marine macrophytes are represented by 12 species and cover approximately 33,600 ha of intertidal and subtidal areas [23,24]. Approximately 80% of seagrasses in Kenya occur in Lamu and Kwale Counties (Table 1). This study focused on mangroves and seagrasses in Kwale and Lamu Counties (Figure 1).

Table 1.

Extent and temporal changes in blue carbon ecosystem coverage within Kwale and Lamu Counties, Kenya.

2.2. Mangroves of Kwale and Lamu Counties

Kwale County hosts approximately 8354 hectares of mangrove forests, primarily consisting of pure and mixed stands of Ceriops tagal (Perr.) C.B.Rob., Rhizophora mucronata Lam., and Avicennia marina (Forssk.) Vierh. The main mangrove concentrations in the county are found in Gazi Bay and the Vanga-Funzi system, including Sii Island. Even though mangrove harvesting is banned in Kwale County, increased demand for mangrove wood products has promoted illegal harvesting activities, leading to forest degradation in many parts of the County. The restoration potential of mangrove forests in Kwale County is estimated at 3725 ha [18].

Lamu County hosts an extensive mangrove cover estimated at around 37,350 ha, accounting for roughly 60% of Kenya’s total mangrove area. These coastal forests consist of both mixed species assemblages, predominantly Rhizophora mucronata, and uniform stands primarily composed of Avicennia marina and Ceriops tagal. For effective management, the Kenya Forest Service (KFS) has divided the mangrove areas in Lamu into five distinct zones: Northern Swamps, Pate Island Swamps, Northern Central Swamps, Southern Swamps, and the Mongoni-Dodori Creek Swamps. Notably, the Northern Swamps and portions of the Northern Central Swamps fall within the boundaries of the Kiunga Marine Biosphere Reserve, where mangrove utilization is subject to conservation regulations [18].

In the Northern Central, Pate Island, and Southern mangrove swamps, community members engage in commercial mangrove logging as a key source of livelihood, with the majority of legal harvesting permits issued in these areas. However, unauthorized cutting of mangrove wood, particularly for traditional lime production, has led to additional degradation of mangrove forests, especially around Pate, Yowea, and Manda Islands [18].

2.3. Seagrasses of Kwale and Lamu Counties

In Kwale County, seagrasses cover approximately 9920 ha and are dominated by pure and mixed stands of Thalassodendron ciliatum (Forssk.) den Hartog, Thalassia hemprichii (Ehrenb.) Asch., Enhalus acoroides (L.f.) Royle, and Syringodium isoetifolium (Asch.) Dandy that are found growing in both intertidal and subtidal areas [25]. Extensive seagrass beds are found in the Diani-Chale lagoon, Gazi Bay, and the Funzi-Vanga seascape. Tourism activities and artisanal fishing are major economic activities in seagrass beds. In Kwale, substantial degradation of seagrass beds has been largely driven by unsustainable fishing practices and intense grazing pressure from sea urchins [26,27].

Seagrasses in Lamu County are estimated to cover 21,067 ha [28] and are dominated by monospecific stands of Thalassodendron ciliatum found in deeper subtidal areas, while multispecies seagrass communities occur in shallow intertidal zones. This is in addition to Cymodea serrulata (R.Br.) Asch. & Magnus, Halodule wrightii Asch., Enhalus acoroides, Halophila ovalis (R.Br.) Hook.f., Halophila stipulaceae (Forssk.) Asch., Thalassia hemprichii, and Syringodium isoetifolium [26]. Fishing is the most prevalent economic activity in Lamu seagrass beds. Human disturbances such as sand harvesting, dredging for infrastructure development, illegal mangrove harvesting, and increased sea urchin herbivory are having devastating effects on seagrass distribution and health [29,30].

2.4. Analysis of Spatial Coverage and Temporal Changes in BC Ecosystems

Blue carbon ecosystems occur in discrete patches along the coast, reflecting the localized environmental settings. For the sake of this study, we grouped mangroves and seagrass distributions to align with the administrative boundaries of Kwale and Lamu counties. Cover and change analyses were performed using Global Land Survey (GLS) data of 30 m spatial resolution, augmented by Landsat imagery from USGS and Google Earth Pro. All imagery underwent atmospheric, radiometric, and geometric corrections before analysis. We then applied a hybrid classification approach, supervised Maximum Likelihood Classification (MLC) combined with an Iso Cluster unsupervised algorithm, achieving an overall accuracy of 80%–85%. Our results were compared against the Global Mangrove Watch datasets [31,32] and previous regional assessments. Additional inputs came from KMFRI’s national blue carbon database and related technical reports. From these data and our cover-change findings, we estimated carbon stocks, sequestration rates, and emissions projections. When local measurements were missing, we used globally derived mean values adjusted for Kenyan conditions. The temporal scope of our analysis spans 1986–2020 for seagrass and 1990–2020 for mangrove ecosystems.

2.5. Sampling Strategy

This study incorporated three main carbon pools: above-ground biomass, below-ground biomass and soil carbon. This was followed by validation of satellite images to determine coverage, current condition, and trends of the two ecosystems in the study area. A total of six sites were assessed for each ecosystem type in Kwale County, whereas three sites were evaluated in Lamu County (Figure 1). Site selection was determined according to the following criteria: (i) structural attributes appeared to be typical of other sites in the area, (ii) different status and conditions of the habitats, and (iii) ease of access and navigation for logistical purposes. To document spatial patterns linked to mangrove zonation, belt transects were set along the intertidal gradient, starting from the seaward edge. A total of 36 and 72 sampling plots, each measuring 100 m2, were established perpendicular to the shoreline in Lamu and Kwale counties, respectively.

2.6. Quantification of Carbon Storage, Sequestration, and Emissions

A comprehensive systematic literature review was carried out by searching from widely recognized digital archives (including Web of Science, Google Scholar, PubMed, JSTOR, Science Direct, as well as institutional repositories and government reports) to gather, assess, and document the present blue carbon ecosystem data in Kenya. The following search words were used: “Coastal ecosystems”, “Mangroves”, “Seagrass”, “Carbon stocks”, “Carbon emissions”, “Kenya AND Lamu”, “Kenya AND Kwale”, “Carbon AND sequestration”, and “Carbon AND markets”. The returned search records included 32 peer-reviewed publications and three KMFRI databases containing information on blue carbon in Kenya (Supplementary Table S1). This was enhanced with primary data collected during the two field activities following a protocol by Kauffman and Donato [33]. At every sampling location, mangrove species were documented, GPS coordinates were taken, and measurements for tree height (in meters), stem diameter (in centimeters), and canopy cover (as a percentage) were collected. From these field measurements, additional vegetation characteristics were calculated, including basal area (m2 ha−1), tree density (stems ha−1), and both above-ground and below-ground biomass (megagrams ha−1) [34,35].

where AGB refers to above-ground biomass (kg), BGB represents below-ground root biomass (kg), p denotes wood density (g cm−3), and D is the diameter at breast height (dbh) measured in centimeters.

AGB = 0.251 × p × D2.46

BGB = 0.199 × p0.899 × D2.22

To estimate carbon stocks, biomass values for above-ground and below-ground components were converted to carbon equivalents using standard conversion coefficients: 0.50 for above-ground biomass (AGB) and 0.39 for below-ground biomass (BGB) [33]. The study focused on quantifying carbon in both above- and below-ground pools, limited to a soil depth of 1 m in mangrove systems and 50 cm in seagrass habitats.

Soil sampling was conducted at the center of each vegetation plot using a semi-circular corer (made of stainless steel, 1 m long) with a diameter of 7.0 cm. Each soil core was divided into depth-specific layers: 0–15 cm, 15–30 cm, 30–50 cm, and 50–100 cm [33]. From the center of each depth segment, a 5 cm sub-sample was extracted, placed in pre-labeled containers, and transported to the laboratory for carbon analysis.

In the laboratory, soil organic carbon (SOC) content was estimated using the Loss on Ignition (LOI) method. Air-dried and homogenized soil samples were weighed into pre-marked aluminum crucibles and then combusted at 450 °C for eight hours in a muffle furnace (Carbolite CWF 13/23, Hope Valley, UK). After cooling in a desiccator, the crucibles were reweighed. The decrease in mass following combustion was attributed to the thermal decomposition of soil organic matter (SOM), and organic matter loss (%LOI) was calculated using a standard formula [33,36]:

%LOI = [(Initial dry weight − Weight after ignition)/Initial dry weight] × 100

The resulting SOM values were then converted to SOC using the equation:

where SOM is the percentage of soil organic matter.

%C = 0.415 × SOM + 2.89

SOC content for each depth interval was then calculated as follows:

with %C expressed as a whole number.

Soil C (Mg C ha−1) = Bulk density (g cm−3) × Depth interval (cm) × %C

Total soil carbon stock was obtained by summing the carbon values from all sampled depth intervals [36]. Mangrove deforestation rates were derived from Compound Annual Growth Rate (CAGR) using the approach by FAO [37]:

where A1 and A2 represent forest cover at time points t1 and t2, respectively, with the rate expressed either in units per year or as a percentage change per year.

Carbon sequestration of mangroves was estimated using Tiers 1 and 2 of IPCC [38], while that of seagrasses was estimated using the global averages [39].

In estimating potential emissions from blue carbon ecosystems in Kenya, we used IPCC’s default values for coastal wetlands [38], which focuses on above-ground vegetation carbon pools as well as sediment carbon in the top meter of sediment, referred to as the ‘near-surface carbon’. These pools are highly vulnerable to disturbances and alterations in land use [38,40,41]. The proportion of ‘near-surface carbon’ released into the atmosphere is estimated to range between 25% and 100%, varying based on the nature and severity of the land-use change involved [40,42]. A 100% impact would represent scenarios where most land uses cause severe changes that transform the system into a fundamentally different state, eliminating and hindering the recovery of near-surface carbon [40,42,43]. On the other hand, a 25% impact would reflect situations where land uses are generally minimal in disturbance, preserving, burying, or simply redistributing most of the ‘near-surface carbon’ [44].

The major drivers of change in blue carbon ecosystems in Kenya are mainly over-utilization of resources and illegal activities, whose impacts at localized levels could be considered as low-end impacts [45,46,47]. We, therefore, used a 25% emission factor (the low-end values) to give conservative estimates for the potential carbon emissions for each ecosystem type. This estimate aligns with IPCC Tier 1 default values [38], which suggest a range of 25%–100% depending on the degree and severity of disturbance. The 25% value was selected to reflect local land-use patterns observed during field assessments, which indicate predominantly light-handed disturbances such as selective logging and small-scale clearance.

Projections of cover and carbon dynamics were made over a 30-year period (2020–2050) under both business-as-usual (BAU) and intervention scenarios, using 2020 as the base year. Historical trends in mangrove and seagrass cover changes were used to estimate future changes proportionally over the projection period. The projections were estimated using the carbon emissions model described by Adame et al. [41] and taking into consideration the assumptions outlined therein. The intervention scenarios were based on the priority actions outlined in [18,48] for mangroves and seagrass, respectively. This approach aligns with the IPCC 2013 Wetlands Supplement [38], which recognizes historical extrapolation as a valid method for constructing baseline scenarios in the absence of detailed site-specific models or land-use projections. We acknowledge that this approach assumes linearity, which may not fully reflect the non-linear and dynamic nature of mangrove and seagrass ecosystems, as shown in Table 1. As such, the results are presented as first-order estimates meant to inform strategic planning and scenario comparison, rather than as precise forecasts.

In estimating mangrove cover/cover change, one challenge we had to overcome was the availability of consistent cloud-free satellite images for the period under consideration. To resolve this, we used the 1990 to 2020 period to establish cover and cover changes, carbon stocks, and emission levels projected to 2050. The choice of 2020 baseline and the projections up to 2050 align well with key national, regional, and global targets, including the following: Kenya’s updated Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs), which emphasize long-term commitments to climate actions; the UN’s Decade on Ecosystem Restoration (2020–2030); the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework, among others.

3. Results

3.1. Mangrove and Seagrass Cover Change in Kwale and Lamu Counties

Kenya’s mangrove cover area is currently estimated at 54,304 ha, reflecting a decline from the previous estimate of 61,271 ha [18]. On the other hand, the area of seagrasses in Kenya was estimated at 39,693 ha, a value higher than the 31,700 ha documented by Harcourt et al. [49]. This discrepancy is plausibly attributable to differences in methodologies used, period of data acquisition, and data sources. Harcourt et al. [49], as well as the present study, utilized Landsat imageries, whereas data used in the mangrove management plan were generated using “medium-scale (1:25,000) panchromatic aerial photographs” [18].

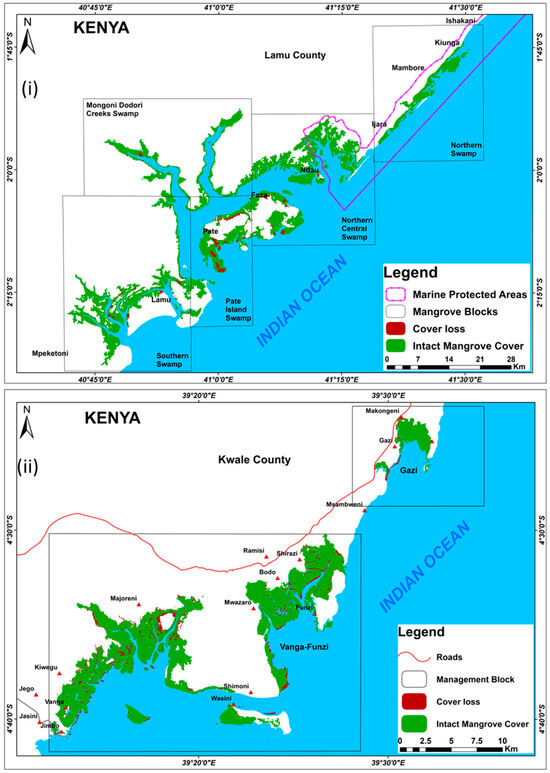

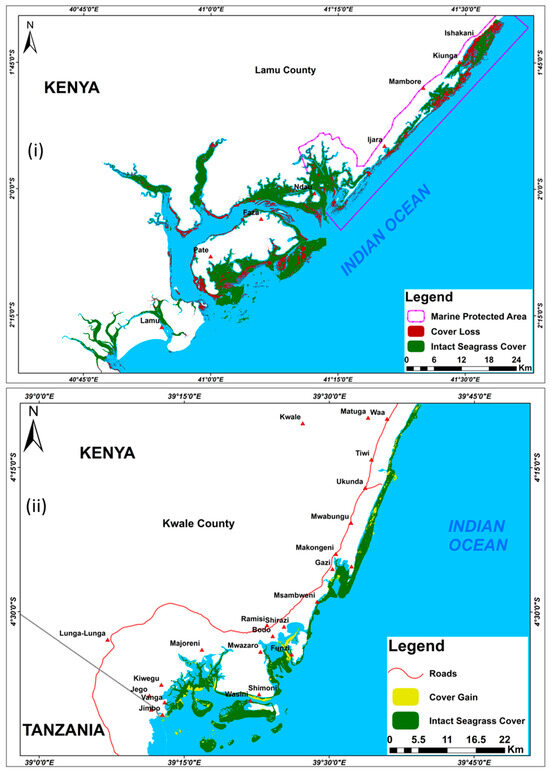

Kwale and Lamu Counties account for approximately 80% of Kenya’s blue carbon ecosystems (Table 1). These ecosystems have experienced losses and gains over the years. At the country level, the mangrove loss rate between 1990 and 2020 was estimated at 0.5% yr−1. In Lamu County, mangroves declined from 37,417 to 35,678 ha, translating to a rate of 0.16% yr−1 (Table 1). This is notably lower than in Kwale County, where mangroves recorded a 0.49% yr−1 reduction. We identified hotspot areas of mangrove changes in Lamu in Manda, Kililana, Njia ya Ndovu, Hidiyo, Bori, Pate, Mkokoni, and Ndau areas. Whereas in Kwale County, the highest mangrove losses and degradation were identified in Majoreni, Kiwegu, Bazo, Bodo, Munje, Mkurumudzi, and Chale areas (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Hotspot areas of mangrove changes (1990 and 2020) in (i) Lamu and (ii) Kwale Counties.

There was a 12.4% increase in seagrass coverage in Kwale County between 1986 and 2020, compared to the 20.4% net reduction in Lamu County (Table 1). Hotspot areas for seagrass changes were observed within Kiunga, Shanga, Mkokoni, Faza, Pate, and partly along the Mongoni-Dodori Creeks, Manda Toto, and Kipungani-Kiongwe areas. In Kwale County, hotspot areas of change were identified at Bazo, Spaki, Kubisu, Mwangani, Shimoni, Wasini, Msambweni, Gazi, and along Chale-Diani Shoreline areas (Figure 3). Causes of mangrove and seagrass losses and degradation in the study areas were found to be over-exploitation, habitat conversion, illegal fishing activities, and climate change.

Figure 3.

Hotspot areas of seagrass changes (1986 and 2020) in (i) Lamu and (ii) Kwale Counties.

3.2. Carbon Stocks and Emission Levels from BCEs in Kwale and Lamu Counties

Carbon Stocks

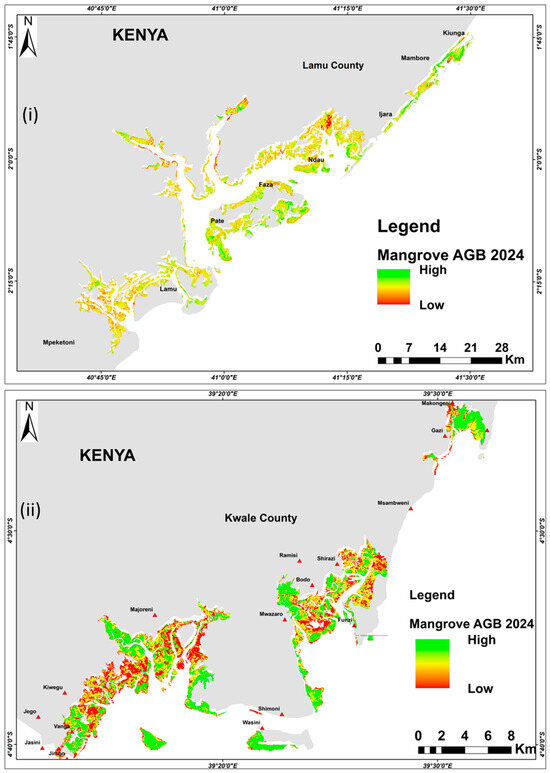

In Lamu County, the estimated above-ground and below-ground biomass carbon in mangroves is 127.85 Mg C ha−1 and 38.72 Mg C ha−1, respectively. When combined with soil organic carbon stocks of approximately 393.66 Mg C ha−1, the total carbon density for mangrove ecosystems in the county amounts to 560.23 Mg C ha−1. Multiplying this density by the total mangrove area of 35,678 hectares yields a cumulative mangrove carbon stock of about 19,987,885.94 Mg C (Table 2). In contrast, mangroves in Kwale County store 64.94 Mg C ha−1 in above-ground biomass and 24.30 Mg C ha−1 in below-ground roots. Soil carbon in these ecosystems is estimated at 437.10 Mg C ha−1, giving a total carbon density of 526.34 Mg C ha−1. Based on a mangrove extent of 7220 hectares, the total carbon stock in Kwale’s mangrove ecosystems is approximately 3,800,174.80 Mg C. The spatial distribution of above-ground mangrove carbon in both counties is illustrated in Figure 4.

Table 2.

Summary of carbon stock densities within BCEs in Kwale and Lamu Counties in Kenya.

Figure 4.

Above-ground biomass distribution in 2024: (i) Lamu and (ii) Kwale Counties.

For seagrasses in Kwale, biomass carbon storage includes 0.5 Mg C ha−1 above-ground and 5.1 Mg C ha−1 below-ground, totaling 5.6 Mg C ha−1. Soil carbon contributes significantly, at 214.69 Mg C ha−1, bringing the total seagrass ecosystem carbon density to 220.29 Mg C ha−1. With a total seagrass coverage of 9920 hectares, the cumulative ecosystem carbon stock reaches roughly 2,185,276.8 Mg C. In Lamu, seagrass ecosystems store 0.65 Mg C ha−1 in above-ground biomass and 5.9 Mg C ha−1 in below-ground biomass, summing to 6.55 Mg C ha−1. When combined with soil carbon stocks of 165.1 Mg C ha−1, the total carbon density reaches 171.65 Mg C ha−1. Given a seagrass area of 22,067 hectares, the total carbon stock is approximately 3,616,150.55 Mg C. When averaged across both counties, seagrass systems have an above-ground biomass carbon of 0.58 Mg C ha−1 and below-ground biomass of 5.5 Mg C ha−1, totaling 6.08 Mg C ha−1 in biomass. The average soil carbon stock is 189.90 Mg C ha−1, leading to a mean total ecosystem carbon density of 195.97 Mg C ha−1. Overall, seagrass ecosystems in the two counties hold a combined carbon stock of about 5,801,427.35 Mg C. As expected, the majority of this carbon is stored in sediment layers (Table 2).

3.3. Potential Emissions

Under the conservative 25% emission scenario, current mangrove carbon emissions in Kwale and Lamu were estimated at 482.92 and 514.01 MgCO2e ha−1, respectively. For seagrasses, the current emission is estimated at 202.71 and 151.48 MgCO2e ha−1 in Kwale and Lamu Counties, respectively. These values can serve as a basis for projecting potential carbon emissions from these blue carbon ecosystems over a defined period of time.

3.4. Projected Cumulative Carbon Stocks, Sequestration Potential, and Emission Estimates from Blue Carbon Ecosystems in Kwale and Lamu Counties over a 30-Year Period

Mangroves and seagrasses in Kenya are declining at an average annual rate of 0.5% and 0.18%, respectively (Table 1). Rates of decline vary across the sites, with mangrove cover declining at 0.47 and 0.16% yr−1 in Kwale and Lamu Counties, respectively. Seagrass cover in Lamu County is declining at 0.67% yr−1, while the same is increasing in Kwale County at 0.34% yr−1. For comparative purposes with other studies, carbon estimates were converted to carbon dioxide (CO2) equivalents using a multiplier of 3.67, reflecting the molecular weight ratio of CO2 to elemental carbon.

Under the business-as-usual (BAU) scenario, mangrove cover within Kwale and Lamu Counties will keep decreasing at 13.8% and 4.7%, respectively, over the 30-year period from 2020 to 2050 (Table 3). This decline would reduce total ecosystem carbon stocks from 13.22 to 11.40 million tCO2e in Kwale, and from 73.35 to 69.94 million tCO2e in Lamu. In contrast, with targeted management interventions, mangrove cover is expected to increase by 6.5% in Kwale and 4.8% in Lamu, resulting in corresponding increases in carbon stocks to 14.08 million tCO2e and 76.90 million tCO2e, respectively. Sequestered carbon also shows notable gains under intervention scenarios, rising from 0.12 to 3.86 million tCO2e in Kwale, and from 0.62 to 19.52 million tCO2e in Lamu (Table 3). In Kwale, the BAU pathway leads to net carbon emissions of −0.83 million tCO2e, equating to a negative carbon value of USD −16.6 million. However, with interventions, net sequestration reaches 1.38 million tCO2e, translating to a positive value of USD 27.6 million. In Lamu County, where the mangrove extent and carbon stocks are significantly higher, the BAU scenario results in net emissions of −0.28 million tCO2e (valued at USD −5.6 million). Management interventions, however, yield net carbon gains of 7.38 million tCO2e, generating a substantial value of USD 147.6 million. These findings highlight the considerable climate mitigation potential and economic value of investing in mangrove restoration and conservation, especially in Lamu.

Table 3.

Projected changes in mangrove and seagrass carbon stocks in Lamu and Kwale Counties between 2020 and 2050.

Under the business-as-usual (BAU) scenario, seagrass ecosystems in Lamu County are projected to decline by 18% in cover over the next 30 years, resulting in cumulative carbon emissions of 5.21 million tCO2e. At a price of 20 USD per tCO2e for high-quality blue carbon credits, this equates to a potential economic loss of USD 104.2 million. However, with project interventions, seagrass cover in Lamu is expected to recover significantly, reducing emissions by 5.12 million tCO2e and generating climate benefits valued at approximately USD 102.4 million, while also delivering ecological and community co-benefits. In Kwale County, seagrass carbon dynamics remain relatively stable under both BAU and intervention scenarios. Project interventions lead to a modest increase in sequestered carbon (0.64 million tCO2e) and a corresponding net carbon value of USD 2.6 million, identical to the BAU outcome. This indicates low carbon loss risk and limited additionality for intervention-based gains. Overall, while Kwale’s seagrass ecosystems show resilience, Lamu’s systems are at greater risk under BAU conditions, but also present greater potential for carbon and economic gains through targeted conservation and restoration actions.

3.5. Estimated Carbon Credit Generation from Mangrove Conservation and Restoration Activities in Kwale and Lamu Counties Between 2024 and 2044

Rehabilitating and safeguarding degraded mangrove and seagrass carbon ecosystems presents a low-cost yet highly effective approach to substantially reducing CO2 emissions. Incentive-based programs linked to blue carbon offer a possible source of income to reward individuals or groups engaged in the conservation of mangroves and seagrasses. While carbon prices vary across voluntary and compliance markets, market trends have indicated that high-quality nature-based credits, including blue carbon, can command premium prices. For instance, prices for high-integrity nature-based carbon credits typically range between 15 and 30 USD/tCO2e, with blue carbon often trading at the upper end of this range due to its co-benefits [22,50]. Additionally, recent market outlook reports for the Voluntary Carbon Market [51,52] indicate that blue carbon projects, particularly those generating measurable biodiversity and community benefits, have attracted credit offers exceeding 20 USD per ton of CO2 equivalent. Projects like Mikoko Pamoja and Vanga Blue Forest in Kenya have participated in the Plan Vivo voluntary standard and have historically received above-average prices, often ranging from 10 to 15 USD/tCO2e, with some premium sales approaching or exceeding USD 20, depending on co-benefits (e.g., biodiversity, community impacts).

Assuming per carbon credit prices of USD 20, the resulting benefits from the interventions in Lamu and Kwale counties over 30 years amount to USD 114,173,700 (Table 4), including other services such as shoreline protection, biodiversity support, and human welfare support (Table 5).

Table 4.

Mangrove and seagrass investment potential in relation to carbon credits in Lamu and Kwale Counties, Kenya.

Table 5.

Co-benefits of Kenya’s mangroves.

3.6. Mangrove Restoration Potential Within Kwale and Lamu Counties

Drivers of mangrove changes within Kwale and Lamu Counties include over-exploitation of wood products, habitat encroachment and conversion, herbivory, unsustainable land uses in the uplands, and climate change, which have synergistically resulted in huge contiguous patches with inadequate natural regeneration. To mitigate the sequential decline of mangroves, priority interventions for Kwale and Lamu include enrichment planting, avoided deforestation, increased surveillance and law enforcement, fencing to keep livestock away, hydrological restoration, and monitoring. The total mangrove restoration potential areas within Kwale and Lamu Counties have been estimated at 2661 and 7714 ha, respectively. In Lamu County, the largest intervention involves avoiding deforestation and protection (6569 ha), supplemented by direct and enrichment planting (454 ha), hydrological restoration (373 ha), and combined actions including law enforcement (220 ha). Research activities cover 46 ha. In Kwale County, priority actions for mangroves have been identified as promoting natural regeneration (2396 ha), direct planting (64 ha), combined direct and enrichment planting (81 ha), enrichment alone (95 ha), hydrological restoration (26 ha), and research (3.2 ha).

4. Discussion

4.1. Cover Change Analysis of Mangroves in Kwale and Lamu

Blue carbon ecosystems in Lamu and Kwale Counties are in different states and conditions. The area of mangrove forests in Lamu and Kwale has been estimated at 35,678 ha and 7220 ha, respectively, both representing over 70% of the total mangrove area in Kenya (Table 1). Our results reveal a net reduction in mangrove cover of 0.16% yr−1 and 0.49% yr−1 in Lamu and Kwale, respectively, which is lower than the 0.5% yr−1 national average, but higher than the rates reported for the Western Indian Ocean region (0.1% yr−1) and the global average (0.13% yr−1) [54]. The loss in Lamu (0.16% yr−1) can be termed as medium, suggesting a concerning trend but not alarming. This is in contrast to the 0.49% yr−1 reduction in Kwale, which can be termed as severe, indicating a critical and unsustainable decline in mangrove cover. The root causes of mangrove decline in Kenya stem from exponential population growth, economic factors, inequalities, and poor governance, besides climate change factors [18,55]. Thus, targeted interventions should address these root causes to be sustainable.

Seagrasses in Lamu and Kwale Counties have been estimated to cover 21,067 ha and 9920 ha, respectively (Table 1). Lamu County is losing seagrasses at a rate of 0.67% yr−1, while in Kwale, there is a net gain of 0.34% yr−1. The observed loss rate of seagrass in Lamu exceeded the national mean of −0.18% yr−1 but remained below the global average of −1.5% yr−1 (Table 1). Seagrass losses in Lamu could be attributed to human and natural causes, including poor fishing activities, coastal development, boating activities, herbivory by urchins, and climate change [49]. The gains in seagrass cover in Kwale, on the other hand, could be due to concerted efforts by the community, civil society, and the government through increased awareness of the values of seagrasses and the necessity of their restoration and protection for nature and livelihood benefits.

4.2. Total Ecosystem Carbon Stocks in Kwale and Lamu Counties

In Lamu County, the estimated total ecosystem carbon (TEC) stock for mangroves is 560.23 Mg C ha−1, while in Kwale County, it stands at 526.34 Mg C ha−1. Both figures exceed Kenya’s national average of 498.9 Mg C ha−1 but remain below the global mean of 755.6 Mg C ha−1 [56] (refer to Table 2). As expected, the majority of this carbon is concentrated in the soil layers, with the remainder found in the biomass pool (see Table 6). This distribution pattern corresponds with results from previous mangrove carbon assessments conducted in Kenya [57] and is consistent with global findings that indicate more than 70% of mangrove carbon is stored in sediments [56].

For seagrass ecosystems, TEC in Kwale County is estimated at 220.29 Mg C ha−1, and 171.65 Mg C ha−1 in Lamu. These values surpass the national average of 140.21 Mg C ha−1 but fall within the global range of approximately 195.98 Mg C ha−1 (see Table 2). Notably, about 97% of seagrass carbon stocks are stored below-ground in sediments, with only a small fraction residing in the plant biomass (Table 6). This trend reflects global observations, which report that over 90% of carbon in seagrass ecosystems is sequestered in sediment layers, with the remainder distributed between above- and below-ground plant tissues [39,58].

Table 6.

Comparison of Kwale and Lamu blue carbon attributes with national, Western Indian Ocean (WIO) region, global values, and tropical forests.

Table 6.

Comparison of Kwale and Lamu blue carbon attributes with national, Western Indian Ocean (WIO) region, global values, and tropical forests.

| Component | Mangroves | Seagrasses | Tropical Forests | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kwale | Lamu | Kenya | WIO a,b | Global b,c | Kwale | Lamu | Kenya | Global c,d | Kenya e | Global e | ||

| This Study | This Study | TNC f | GMW a | This Study | This Study | TNC f | ||||||

| Cover change (% yr−1) | −0.49 | −0.16 | −0.57 | −0.1 | −0.14 | −0.14 | +0.34 | −0.67 | −0.26 | −1.5 | −0.43 | - |

| Vegetation Carbon (tC ha−1) | 89.24 | 166.57 | 108.69 | - | 92.7 | 147.49 | 5.6 | 6.55 | 6.25 | 1.84 | 36.69 | 54 |

| Soil Organic Carbon (tC ha−1) | 437.10 | 393.66 | 390.21 | - | 335.7 | 320.00 | 214.69 | 165.1 | 214.69 | 70 | - | 55 |

| Total Ecosystem Carbon (tC ha−1) | 526.34 | 560.23 | 498.90 | - | 428.4 | 467.49 | 220.29 | 171.65 | 220.94 | 71.84 | - | 109 |

Sources: a = [45]; b = [32]; c = [59]; d = [39]; e = [60]; f = [29]. TNC = The Nature Conservancy and GMW = Global Mangrove Watch.

4.3. Cumulative Carbon Storage, Sequestration, and Emissions Projections in Mangrove and Seagrasses in Kwale and Lamu Counties Between 2024–2044

A summary table of BCEs in Kwale and Lamu, compared to Kenya and elsewhere, is provided in Table 6. Lamu’s mangroves exhibit higher biomass carbon (166.57 tC ha−1) than Kwale (89.24 tC ha−1) and the global average (92.7 tC ha−1). Soil carbon stocks in Kwale (437.10 tC ha−1) are higher than in Lamu (393.66 tC ha−1), and both exceed the global average (335.7 tC ha−1). Lamu’s seagrass carbon stock (6.55 tC ha−1) is higher than Kwale’s (5.6 tC ha−1) but much lower than the global average for seagrasses (36.69 tC ha−1). Soil carbon stocks are higher in Kwale (214.69 tC ha−1) compared to Lamu (165.1 tC ha−1), and both were higher than the global average for seagrasses (70 tC ha−1). On an area basis, mangroves in Kwale and Lamu have much higher carbon stocks when compared to their terrestrial counterparts in Kenya and elsewhere.

5. Conclusions

This study assessed the status, conditions, and trends of blue carbon in Kwale and Lamu Counties in Kenya. The emissions and sequestration levels were subjected to a 20–30-year crediting period to establish their investment potential in the two Counties. Mangroves and seagrasses can capture and store 6.65 and 0.88 tCO2 ha−1 yr−1, respectively. Over a 20-year crediting period, mangroves in Kwale and Lamu could sequester up to 2.57 million tCO2e and 13.01 million tCO2e, respectively. Seagrasses also demonstrate notable carbon sequestration potentials of up to 6.4 million tCO2e and 0.37 million tCO2e in Kwale and Lamu Counties over the same period. These carbon sequestration potentials present investment opportunities with multiple co-benefits. With an estimated market price of 20 USD/tCO2e for ‘high-quality’ blue carbon credits, the potential revenue to be generated from sales of mangrove and seagrass blue carbon credits in Lamu is estimated at USD3,589,750, while in Kwale, seagrass carbon credits are valued at USD 216,040 yr−1. By determining blue carbon stocks, sequestration rates, degradation hotspots, and emissions projections over the next 20 years, this study lays the foundation for potential investments in blue carbon for the benefit of nature and society. The combination of financial incentives for the conservation and management of BCEs presents a viable opportunity for impactful climate action investments, while unlocking substantial ecological and societal benefits. To fully harness the benefits of blue carbon, the study recommends integrating BC into Kenya’s climate policies, enhancing local capacity, and aligning coastal land-use planning with conservation goals. Identified barriers include reliance on secondary sequestration data, exclusion of deep soil carbon and methane flux estimates, and poor carbon pricing.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/f16111717/s1, Supplementary Table S1: Summary of existing blue carbon studies in Kenya as described in [26].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.G.K., A.M. and G.N.W.; methodology, J.G.K., J.K.S.L., A.M., G.N.W., G.K.K. and K.M.; software, A.M., F.M., J.K.S.L. and G.N.W.; validation, F.M., A.M., G.N.W., G.K. and B.K.G.; formal analysis, J.K.S.L., A.M., F.M. and G.N.W.; investigation, F.M., A.M., G.N.W. and B.K.G.; resources, J.G.K.; data curation, A.M., F.M., G.N.W. and J.K.S.L.; writing—original draft preparation, J.G.K., A.M., F.M., G.N.W., G.K., G.K.K., K.M. and B.K.G.; writing—review and editing, G.K.K., K.M., J.K.S.L. and L.O.; visualization, F.M., J.K.S.L., A.M. and G.N.W.; supervision, and L.O.; project administration and funding acquisition, J.K.S.L., L.O., G.K.K. and K.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

GIZ-Kenya under the IKI Kwale Tanga Project and GIZ Germany, Tender Reference No: 83451583. Additional support was through PEGASuS 5.1. Future Earth subgrant project funded by Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, PTE Future Earth Award No. 3839 and The Nature Conservancy (Grant No. F107291-KMFRI-20230203). We sincerely thank Anna-Sophia Elm (GIZ-Germany) for her valuable contribution in reviewing and providing constructive feedback on the initial draft of this manuscript.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data underlying the findings of this study can be obtained from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. However, the data is not publicly accessible due to privacy considerations.

Acknowledgments

The authors sincerely thank Marvin Osumba, Anne Wanjiru, and Hamisi Kirauni (all from KMFRI) for their valuable support and collaboration during data collection.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Lisa Omingo is affiliated with Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted independently, with no commercial or financial relationships that might be interpreted as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Howard, J.; Sutton-Grier, A.; Herr, D.; Kleypas, J.; Landis, E.; McLeod, E.; Pidgeon, E.; Simpson, S. Clarifying the role of coastal and marine systems in climate mitigation. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2017, 15, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. 2019 Refinement to the 2006 IPCC Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories; Calvo Buendia, E., Tanabe, K., Kranjc, A., Baasansuren, J., Fukuda, M., Ngarize, S., Osako, A., Pyrozhenko, Y., Shermanau, P., Federici, S., Eds.; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019; Available online: https://www.ipcc-nggip.iges.or.jp/public/2019rf/pdf/4_Volume4/19R_V4_Cover.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2024).

- Macreadie, P.I.; Costa, M.D.P.; Atwood, T.B.; Friess, D.A.; Kelleway, J.J.; Kennedy, H.; Lovelock, C.E.; Serrano, O. Blue carbon as a natural climate solution. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2021, 2, 826–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, T.; Wei, P.P.; Li, S.; Zhu, H.L.; Fu, Y.J.; Gan, K.Y.; Xu, S.J.-L.; Lee, F.W.-F.; Li, F.-L.; Jiang, M.-G.; et al. Lessons from a degradation of planted Kandelia obovata mangrove forest in the Pearl River Estuary, China. Forests 2023, 14, 532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mcleod, E.; Chmura, G.L.; Bouillon, S.; Salm, R.; Björk, M.; Duarte, C.M.; Lovelock, C.E.; Schlesinger, W.H.; Silliman, B.R. A blueprint for blue carbon: Toward an improved understanding of the role of vegetated coastal habitats in sequestering CO2. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2011, 9, 552–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoegh-Guldberg, O.; Jacob, D.; Taylor, M.; Guillén Bolaños, T.; Bindi, M.; Brown, S.; Camilloni, I.A.; Diedhiou, A.; Djalante, R.; Ebi, K.; et al. The human imperative of stabilizing global climate change at 1.5 °C. Science 2019, 365, eaaw6974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Global Forest Resources Assessment 2020. 2020. Available online: https://www.fao.org/forest-resources-assessment (accessed on 14 August 2024).

- Dunic, J.C.; Brown, C.J.; Connolly, R.M.; Turschwell, M.P.; Côté, I.M. Long-term declines and recovery of meadow area across the world’s seagrass bioregions. Glob. Change Biol. 2021, 27, 4096–4109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, A.D.; Fatoyinbo, L.; Goldberg, L.; Lagomasino, D. Global hotspots of salt marsh change and carbon emissions. Nature 2022, 612, 701–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FAO. The State of the World’s Forests 2022. In Forest Pathways for Green Recovery and Building Inclusive, Resilient and Sustainable Economies; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. From mangroves to seagrass, blue carbon ecosystems are critical to tackling climate change. In Unlocking Blue Carbon Development Report; World Bank Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2023; Available online: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/entities/publication/304fe159-e9ea-40ef-b568-fa6e8e992bb4 (accessed on 23 September 2024).

- Friess, D.A.; Shribman, Z.I.; Stankovic, M.; Iram, N.; Millman Baustian, M.; Ewers Lewis, C.J. Restoring blue carbon ecosystems. Camb. Prism. Coast. Futures 2024, 2, e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal, M.; Spalding, M. The State of the World’s Mangroves 2022; Global Mangrove Alliance: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do Amaral Camara Lima, M.; Bergamo, T.F.; Ward, R.D.; Joyce, C.B. A review of seagrass ecosystem services: Providing nature-based solutions for a changing world. Hydrobiologia 2023, 850, 2655–2670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNEP-WCMC. Understanding How Mangrove Loss Threatens Biodiversity. United Nations Environment Programme World Conservation Monitoring Centre. 2024. Available online: https://www.unep-wcmc.org/en/news/understanding-how-mangrove-loss-threatens-biodiversity (accessed on 3 April 2025).

- Friess, D.A.; Krauss, K.W.; Taillardat, P.; Adame, M.F.; Yando, E.S.; Cameron, C.; Sasmito, S.; Sillanpää, M. Mangrove blue carbon in the face of deforestation, climate change, and restoration. Annu. Plant Rev. 2020, 3, 427–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, C.; Steckbauer, A.; Mann, H.; Duarte, C.M. Achieving the Kunming–Montreal global biodiversity targets for blue carbon ecosystems. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2024, 5, 538–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Government of Kenya. National Mangrove Ecosystem Management Plan; Kenya Forest Service: Nairobi, Kenya, 2017; Available online: https://portal.mikoko.co.ke/document/show/7236 (accessed on 11 August 2024).

- Hamza, A.J.; Esteves, L.S.; Cvitanovic, M.; Kairo, J. Past and present utilization of mangrove resources in Eastern Africa and drivers of change. J. Coast. Res. 2020, 95 (Suppl. S1), 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamau, A.W.; Shauri, H.; Hugé, J.; Van Puyvelde, K.; Koedam, N.; Kairo, J.G. Patterns of Mangrove Resource Uses within the Transboundary Conservation Area of Kenya and Tanzania. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ecosystem Marketplace. State of the Voluntary Carbon Markets 2022; Forest Trends Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2022; Available online: https://www.ecosystemmarketplace.com/publications/state-of-the-voluntary-carbon-markets-2022/ (accessed on 2 April 2025).

- UNEP. State of Finance for Nature: Tripling Investments in Nature-Based Solutions by 2030. 2021. Available online: https://wedocs.unep.org/xmlui/bitstream/handle/20.500.11822/36145/SFN.pdf (accessed on 16 July 2024).

- UNEP. The Natural Fix: The Role of Ecosystems in Climate Mitigation; A UNEP Rapid Response Assessment-United Nations Environment Programme; UNEP-WCMC: Cambridge, UK, 2009; Volume 3, pp. 154–196. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/236979527_The_Natural_Fix_The_Role_of_Ecosystems_in_Climate_Mitigation (accessed on 24 September 2024).

- UNEP Nairobi Convention; WIOMSA. The Regional State of the Coast Report: Western Indian Ocean. 2015. Available online: https://www.wiomsa.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/Regional_State_of_the_Coast_Report_Western_Indian_OceanRSOCR_Final.pdf.pdf (accessed on 23 September 2024).

- Githaiga, M.N.; Gilpin, L.; Kairo, J.G.; Huxham, M. Biomass and productivity of seagrasses in Africa. Bot. Mar. 2016, 59, 173–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GIZ. Blue Carbon and Fishery Potential in Kwale and Lamu Counties, Kenya; GIZ: Nairobi, Kenya, 2024; Available online: https://www.kmfri.go.ke/images/2025/pdf/blue%20Carbon%20and%20Fishery%20Potential%20in%20Kenya.pdf (accessed on 20 December 2024).

- Uku, J.; Daudi, L.; Muthama, C.; Alati, V.; Kimathi, A.; Ndirangu, S. Seagrass restoration trials in tropical seagrass meadows of Kenya. West. Indian Ocean. J. Mar. Sci. 2021, 20, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwikamba, E.M.; Githaiga, M.N.; Briers, R.A.; Huxham, M. A review of seagrass cover, status and trends in Africa. Estuaries Coasts 2024, 47, 917–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TNC. Ocean Climate Actions in the Paris Agreement: Incorporating Ocean Climate Actions in the Revised Kenya’s Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs); Technical Report; TNC: Hong Kong, China, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Eklöf, J.S.; De la Torre-Castro, M.; Gullström, M.; Uku, J.; Muthiga, N.; Lyimo, T.; Bandeira, S.O. Sea urchin overgrazing of seagrasses: A review of current knowledge on causes, consequences, and management. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2008, 79, 569–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunting, P.; Rosenqvist, A.; Lucas, R.M.; Rebelo, L.; Hilarides, L.; Thomas, N.; Hardy, A.; Itoh, T.; Shimada, M.; Finlayson, C.M. The Global Mangrove Watch—A New 2010 Global Baseline of Mangrove Extent. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunting, P.; Rosenqvist, A.; Hilarides, L.; Lucas, R.M.; Thomas, N. Global mangrove watch: Updated 2010 mangrove forest extent (v2.5). Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kauffman, J.B.; Donato, D.C. Protocols for the Measurement, Monitoring, and Reporting of Structure, Biomass, and Carbon Stocks in Mangrove Forests; Cifor: Bogor, Indonesia, 2012; Volume 86, p. 7. Available online: https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/document?repid=rep1&type=pdf&doi=73ed3110a79d21d71e26ebca3ac0d66395cc69d1 (accessed on 18 August 2024).

- Komiyama, A.; Poungparn, S.; Kato, S. Common allometric equations for estimating the tree weight of mangroves. J. Trop. Ecol. 2005, 21, 471–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komiyama, A.; Ong, J.E.; Poungparn, S. Allometry, biomass, and productivity of mangrove forests: A review. Aquat. Bot. 2008, 89, 128–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, J.; Hoyt, S.; Isensee, K.; Telszewski, M.; Pidgeon, E. Coastal Blue Carbon: Methods for Assessing Carbon Stocks and Emissions Factors in Mangroves, Tidal Salt Marshes, and Seagrasses; International Union for Conservation of Nature: Arlington, VA, USA, 2014; Available online: https://www.cifor-icraf.org/knowledge/publication/5095/ (accessed on 20 August 2024).

- FAO. Forest Resources Assessment 1990. 1995. Available online: https://agris.fao.org/search/en/providers/122621/records/647228a469d6cbfdd4a36133 (accessed on 21 August 2024).

- IPCC. 2013 Supplement to the 2006 IPCC Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories: Wetlands; Hiraishi, T., Krug, T., Tanabe, K., Srivastava, N., Baasansuren, J., Fukuda, M., Troxler, T.G., Eds.; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014; Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/publication/2013-supplement-to-the-2006-ipcc-guidelines-for-national-greenhouse-gas-inventories-wetlands/ (accessed on 18 July 2024).

- Fourqurean, J.W.; Duarte, C.M.; Kennedy, H.; Marbà, N.; Holmer, M.; Mateo, M.A.; Apostolaki, E.T.; Kendrick, G.A.; Krause-Jensen, D.; McGlathery, K.J.; et al. Seagrass ecosystems as a globally significant carbon stock. Nat. Geosci. 2012, 5, 505–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pendleton, L.; Donato, D.C.; Murray, B.C.; Crooks, S.; Jenkins, W.A.; Sifleet, S.; Craft, C.; Fourqurean, J.W.; Kauffman, J.B.; Marbà, N.; et al. Estimating global blue carbon emissions from conversion and degradation of vegetated coastal ecosystems. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e43542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adame, M.F.; Connolly, R.M.; Turschwell, M.P.; Lovelock, C.E.; Fatoyinbo, T.; Lagomasino, D.; Goldberg, L.A.; Holdorf, J.; Friess, D.A.; Sasmito, S.D.; et al. Future carbon emissions from global mangrove forest loss. Glob. Change Biol. 2021, 27, 2856–2866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamilton, S.E.; Friess, D.A. Global carbon stocks and potential emissions due to mangrove deforestation from 2000 to 2012. Nat. Clim. Change 2018, 8, 240–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, J.R.; Cameron, C.; Arias-Ortiz, A.; Cifuentes-Jara, M.; Crooks, S.; Dahl, M.; Friess, D.A.; Kennedy, H.; Lim, K.E.; Lovelock, C.E.; et al. Global seagrass carbon stock variability and emissions from seagrass loss. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 3798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salinas, C.; Duarte, C.M.; Lavery, P.S.; Masque, P.; Arias-Ortiz, A.; Leon, J.X.; Callaghan, D.; Kendrick, G.A.; Serrano, O. Seagrass losses since mid-20th century fuelled CO2 emissions from soil carbon stocks. Glob. Change Biol. 2020, 26, 4772–4784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erftemeijer, P.; de Boer, M.; Hilarides, L. Status of Mangroves in the Western Indian Ocean Region; Wetlands International: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 1–67. Available online: https://www.nairobiconvention.org/clearinghouse/sites/default/files/wetlands-international_mangrove-report_2022-1.pdf (accessed on 17 July 2024).

- Hamza, A.J.; Esteves, L.S.; Cvitanović, M. Changes in Mangrove Cover and Exposure to Coastal Hazards in Kenya. Land 2022, 11, 1714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otundo Richard, M. Blue Carbon and the Role of Mangroves in Carbon Sequestration: Its Mechanisms, Estimation, Human Impacts and Conservation Strategies for Economic Incentives Among African Countries Along the Indian Ocean Belt. SSRN Electron. J. 2024, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Government of Kenya. Coral Reef and Seagrass Ecosystems Management Strategy 2015–2019; Kenya Wildlife Service: Nairobi, Kenya, 2015; Available online: https://reefresilience.org/wp-content/uploads/Kenya-National-Coral-Reef-Restoration-Protocol.pdf (accessed on 4 March 2025).

- Harcourt, W.D.; Briers, R.A.; Huxham, M. The thin (ning) green line? Investigating changes in Kenya’s seagrass coverage. Biol. Lett. 2018, 14, 20180227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farahmand, S.; Hilmi, N.; Duarte, C.M. The rise and flows of blue carbon credits advance global climate and biodiversity goals. Nat. Partn. J. Ocean. Sustain. 2025, 4, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ecosystem Marketplace. State of the Blue Carbon Market 2024; Forest Trends Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2024; Available online: https://www.ecosystemmarketplace.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/State_of_the_Blue_Carbon_Market_final.pdf (accessed on 13 August 2024).

- International Finance Corporation. Deep Blue: Opportunities for Blue Carbon Finance in Coastal Ecosystems. World Bank Group. 2023. Available online: https://www.ifc.org/en/insights-reports/2023/blue-carbon-finance-in-coastal-ecosystems (accessed on 15 August 2024).

- Murray, B.C.; Pendleton, L.; Jenkins, W.A.; Sifleet, S. Green Payments for Blue Carbon: Economic Incentives for Protecting Threatened Coastal Habitats. 2011. Available online: https://www.forest-trends.org/publications/green-payments-for-blue-carbon/ (accessed on 15 August 2024).

- FAO. FRA 2020 Remote Sensing Survey; FAO Forestry Paper No. 186; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maina, J.M.; Bosire, J.O.; Kairo, J.G.; Bandeira, S.O.; Mangora, M.M.; Macamo, C.; Ralison, H.; Majambo, G. Identifying global and local drivers of change in mangrove cover and the implications for management. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2021, 30, 2057–2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alongi, D.M. Global significance of mangrove blue carbon in climate change mitigation. Sci. Rep. 2020, 2, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirui, K.B.; Kairo, J.G.; Bosire, J.; Viergever, K.M.; Rudra, S.; Huxham, M.; Briers, R.A. Mapping of mangrove forest land cover change along the Kenya coastline using Landsat imagery. Ocean. Coast. Manag. 2013, 83, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, C.M.; Merino, M.; Agawin, N.S.; Uri, J.; Fortes, M.D.; Gallegos, M.E.; Marbá, N.; Hemminga, M.A. Root production and belowground seagrass biomass. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 1998, 171, 97–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siikamäki, J.; Sanchirico, J.N.; Jardine, S.L. Global economic potential for reducing carbon dioxide emissions from mangrove loss. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 14369–14374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Veiga, P.; Carreiras, J.; Smallman, T.L.; Exbrayat, J.F.; Ndambiri, J.; Mutwiri, F.; Nyasaka, D.; Quegan, S.; Williams, M.; Balzter, H. Carbon stocks and fluxes in Kenyan forests and wooded grasslands derived from earth observation and model-data fusion. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 2380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).