Optimal Training Sample Sizes for U-Net-Based Tree Species Classification with Sentinel-2 Imagery

Abstract

1. Introduction

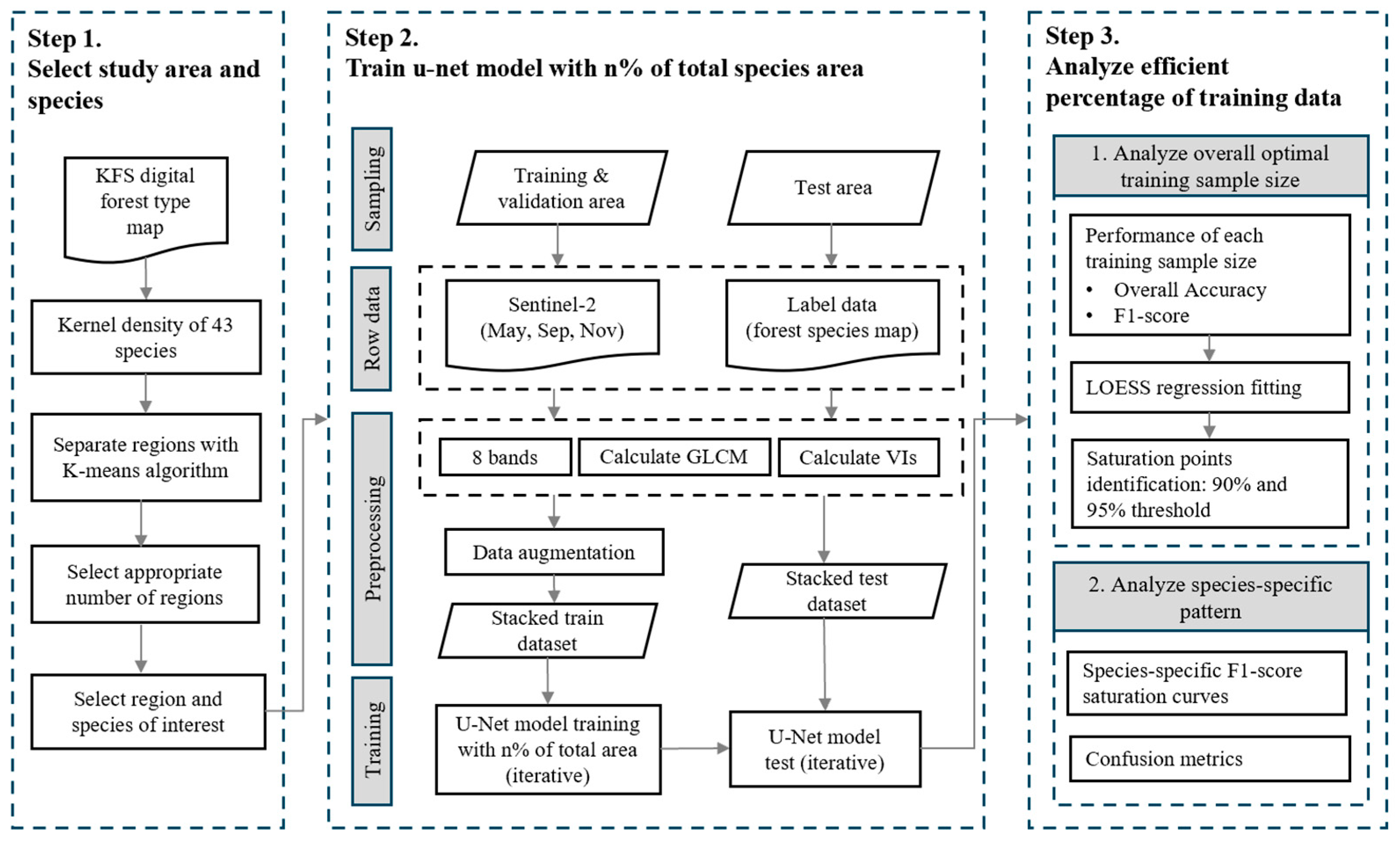

2. Materials and Methods

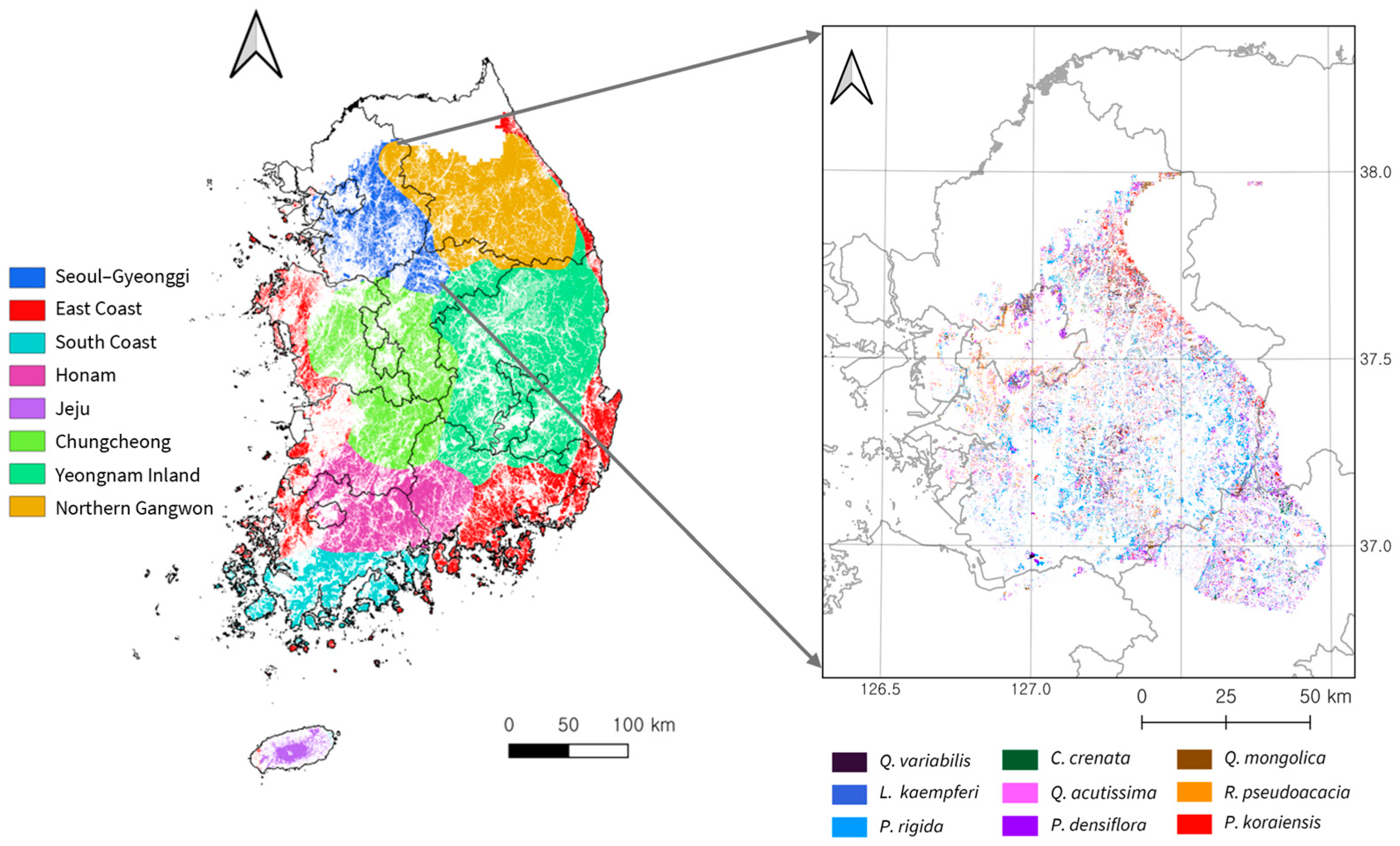

2.1. Study Area

2.1.1. National-Scale Regionalization

2.1.2. Seoul–Gyeonggi Region

2.2. Training Data Collection and Preprocessing

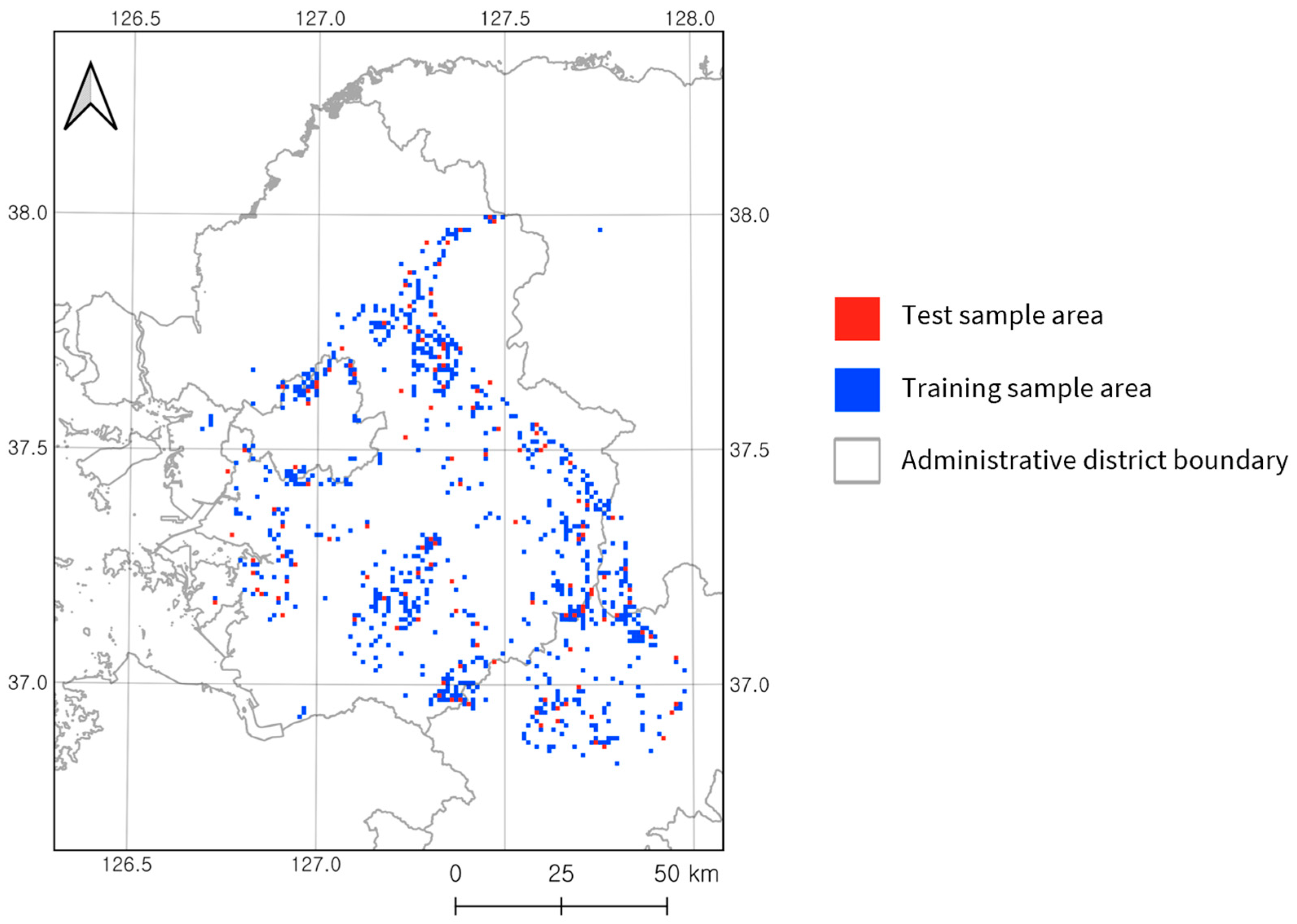

2.2.1. Training and Test Set Sampling Strategy

2.2.2. Sentinel-2 Imagery

2.2.3. Label Data

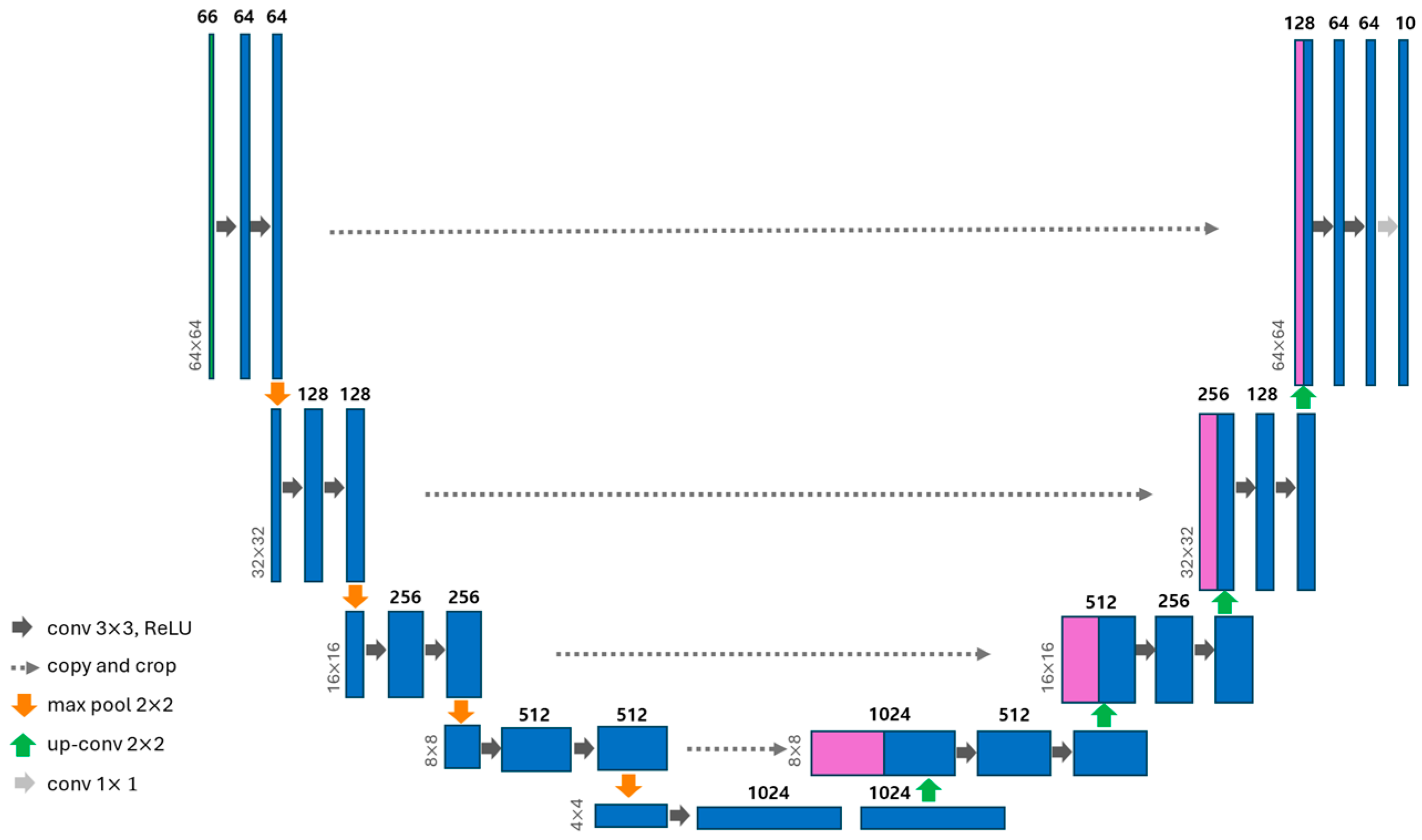

2.3. Deep-Learning Model Implementation

2.3.1. U-Net Model Architecture

2.3.2. Incremental Training Experiment Design

2.3.3. Model Performance Evaluation

2.3.4. Optimal Training Sample Size Analysis

3. Results

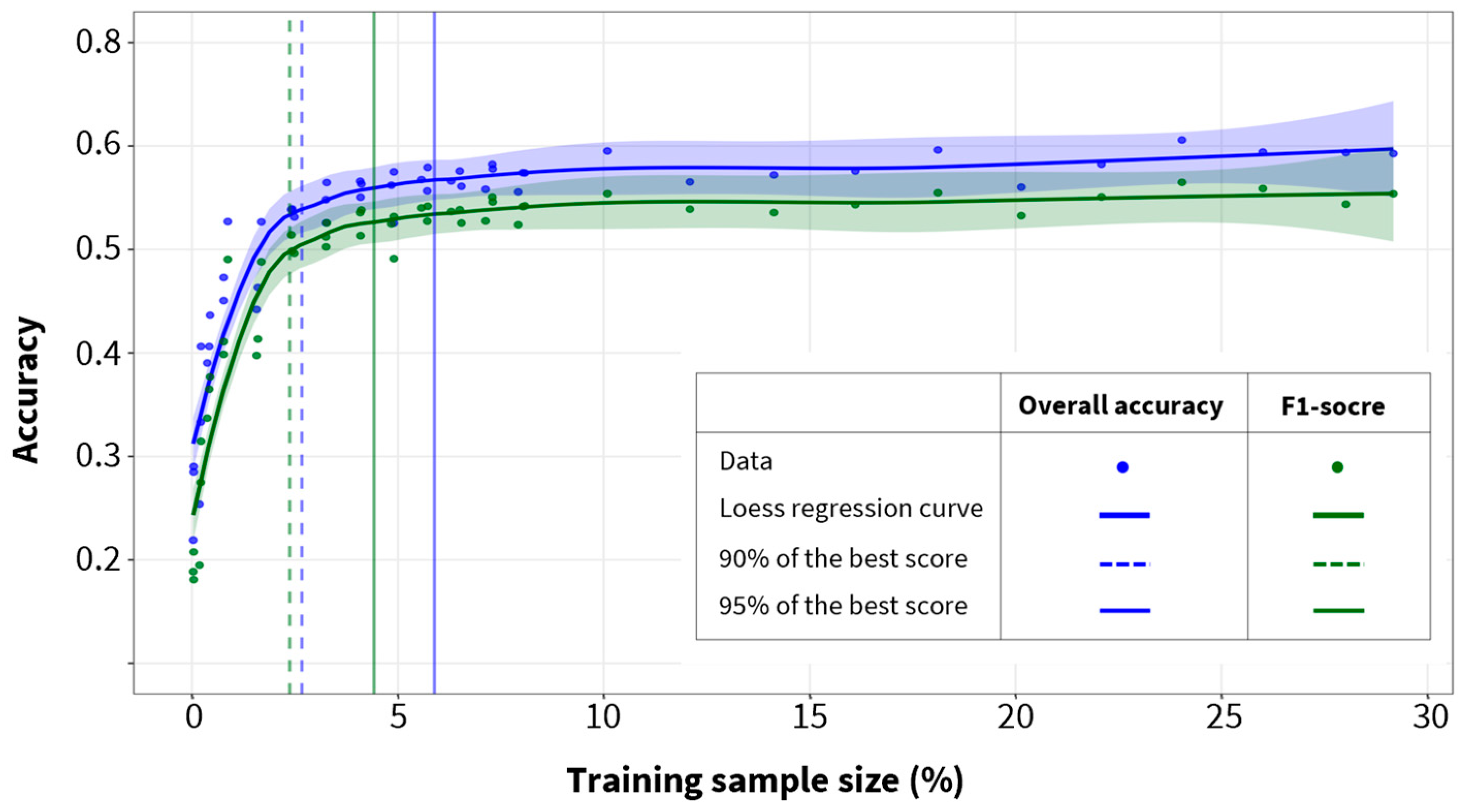

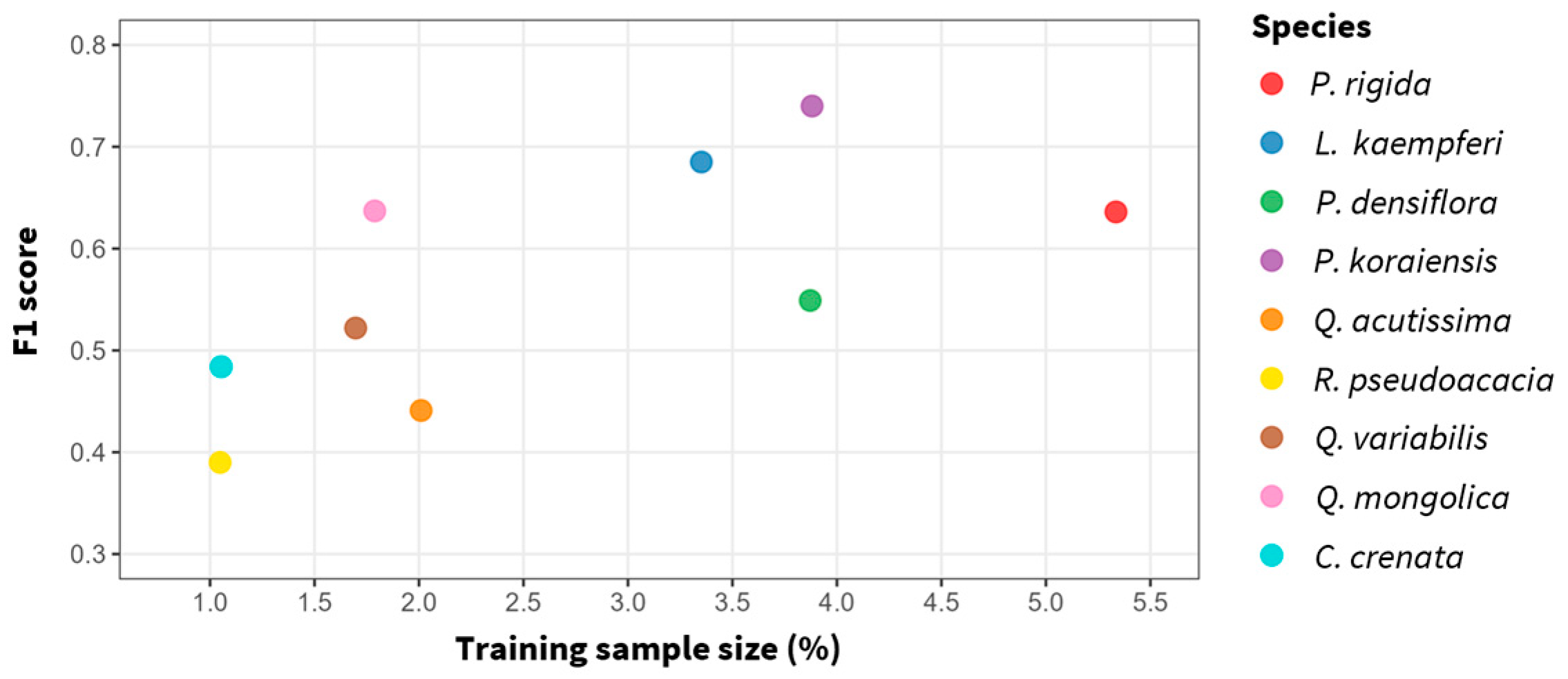

3.1. Optimal Training Sample Size and Maximum Accuracy

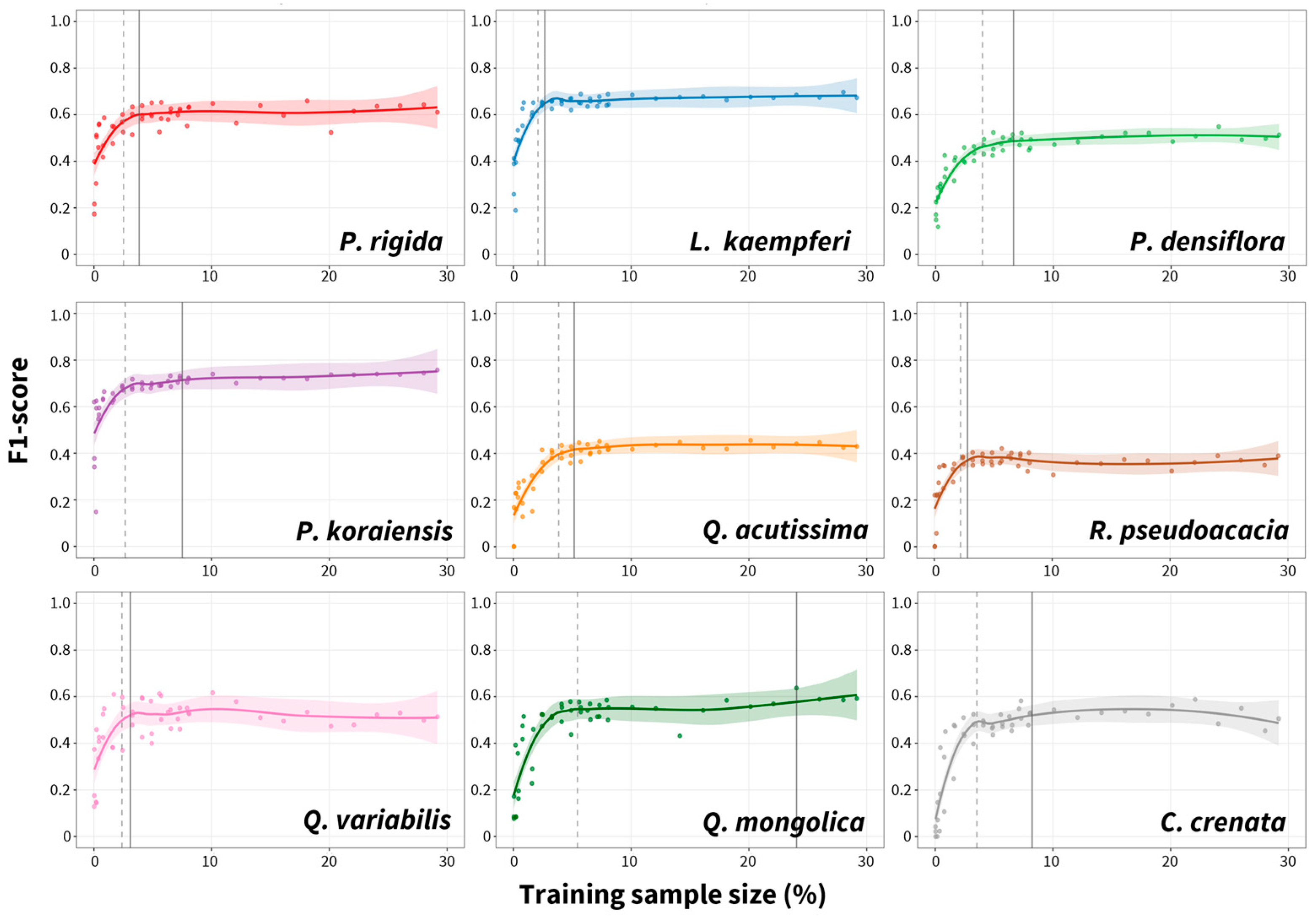

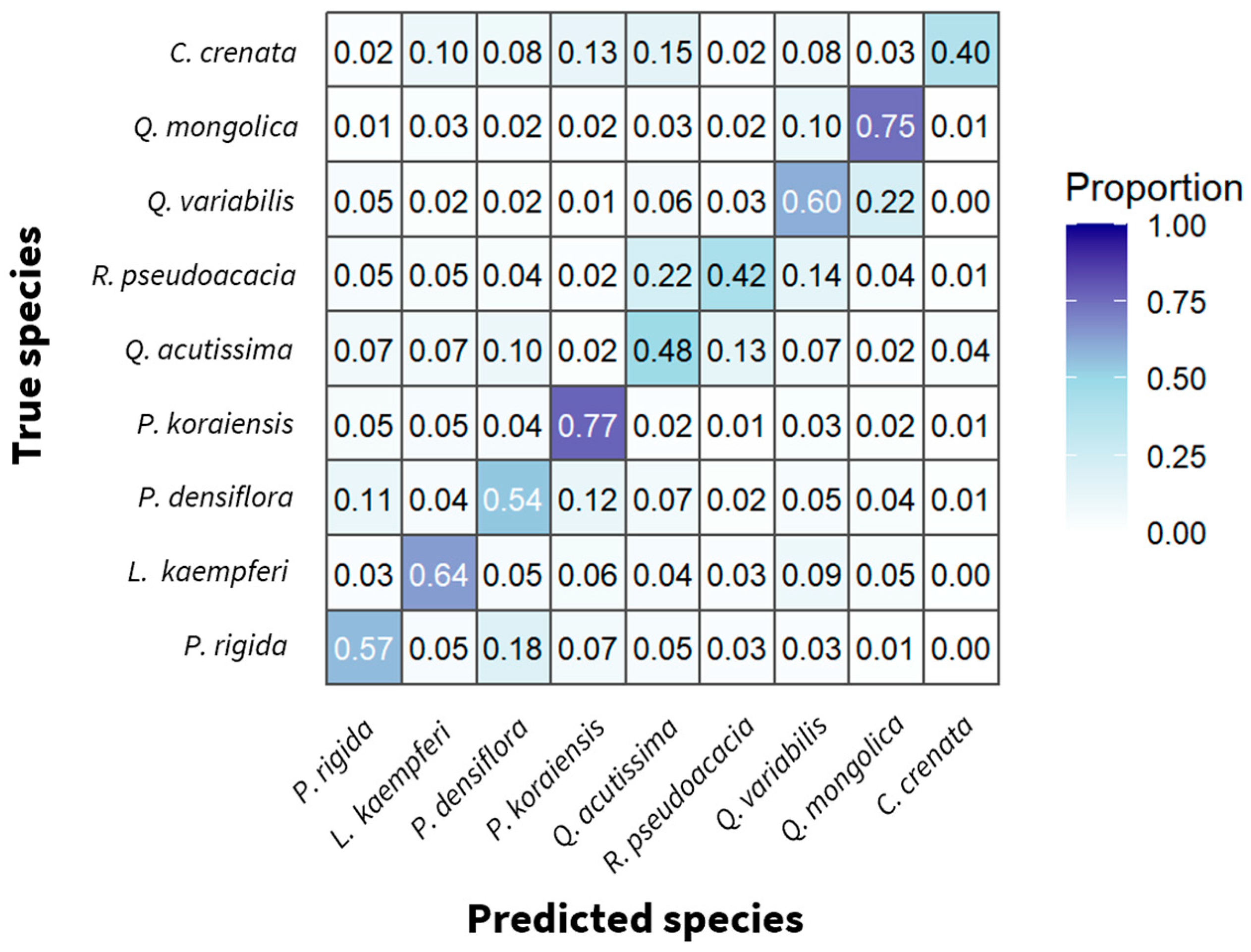

3.2. Species-Specific Classification Accuracy and Confusion Patterns

4. Discussion

4.1. Optimal Training Sample Size for Forest Tree Species Classification

4.2. Species Classification Performance and Limiting Factors

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CNN | Convolutional neural network |

| DFTM | Digital forest type map |

| LOESS | Locally estimated scatterplot smoothing |

| GLCM | Gray-level co-occurrence matrix |

| WSS | Within-cluster sum of squares |

| NDVI | Normalized difference vegetation index |

| GNDVI | Green normalized difference vegetation index |

| RVI | Ratio vegetation index |

| NDRE | Normalized difference red edge |

| CIre | Chlorophyll index red edge |

| MCARI | Modified chlorophyll absorption ratio index |

| SAVI | Soil-adjusted vegetation index |

| OA | Overall accuracy |

| TP | True positive |

| FP | False positive |

| FN | False negative |

| TN | True negative |

| NIR | Near-infrared |

| SWIR | Shortwave infrared |

| SCL | Scene classification layer |

| QA | Quality assessment |

Appendix A

| Window Size | Test Accuracy (Mean ± Std) |

|---|---|

| 3 × 3 | 0.1827 ± 0.0264 |

| 5 × 5 | 0.1799 ± 0.0277 |

| 7 × 7 | 0.1848 ± 0.0245 |

| Species | Label Noise (%) |

|---|---|

| Pinus rigida | 2.94 |

| Larix kaempferi | 5.88 |

| Pinus densiflora | 4.41 |

| Pinus koraiensis | 1.47 |

| Quercus acutissima | 2.94 |

| Robinia pseudoacacia | 8.82 |

| Quercus variabilis | 4.41 |

| Quercus mongolica | 2.94 |

| Castanea crenata | 4.41 |

| Number of Images | Training Sample Size (%) | OA (%) | Macro F1-Score |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.03 | 0.22 | 0.19 |

| 5 | 0.21 | 0.33 | 0.27 |

| 10 | 0.42 | 0.41 | 0.36 |

| 20 | 0.77 | 0.45 | 0.41 |

| 40 | 1.57 | 0.44 | 0.40 |

| 60 | 2.43 | 0.54 | 0.50 |

| 80 | 3.25 | 0.55 | 0.51 |

| 100 | 4.09 | 0.55 | 0.51 |

| 120 | 4.90 | 0.58 | 0.53 |

| 140 | 5.72 | 0.58 | 0.54 |

| 160 | 6.54 | 0.56 | 0.53 |

| 180 | 7.29 | 0.58 | 0.55 |

| 200 | 8.03 | 0.57 | 0.54 |

| 250 | 10.09 | 0.60 | 0.55 |

| 300 | 12.09 | 0.57 | 0.54 |

| 350 | 14.13 | 0.57 | 0.54 |

| 400 | 16.11 | 0.58 | 0.54 |

| 450 | 18.11 | 0.60 | 0.55 |

| 500 | 20.14 | 0.56 | 0.53 |

| 550 | 22.08 | 0.58 | 0.55 |

| 600 | 24.04 | 0.61 | 0.56 |

| 650 | 26.00 | 0.59 | 0.56 |

| 700 | 28.02 | 0.59 | 0.54 |

| 728 | 29.17 | 0.59 | 0.55 |

| Number of Images | Training Sample Size (%) | OA (%) | Macro F1-Score |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.04 | 0.29 | 0.21 |

| 5 | 0.18 | 0.25 | 0.19 |

| 10 | 0.37 | 0.39 | 0.34 |

| 20 | 0.77 | 0.47 | 0.40 |

| 40 | 1.60 | 0.46 | 0.41 |

| 60 | 2.41 | 0.54 | 0.51 |

| 80 | 3.27 | 0.56 | 0.53 |

| 100 | 4.11 | 0.56 | 0.54 |

| 120 | 4.90 | 0.53 | 0.49 |

| 140 | 5.71 | 0.56 | 0.53 |

| 160 | 6.50 | 0.58 | 0.54 |

| 180 | 7.30 | 0.58 | 0.55 |

| 200 | 8.08 | 0.57 | 0.54 |

| Number of Images | Training Sample Size (%) | OA (%) | Macro F1-Score |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.04 | 0.29 | 0.18 |

| 5 | 0.22 | 0.41 | 0.31 |

| 10 | 0.44 | 0.44 | 0.38 |

| 20 | 0.87 | 0.53 | 0.49 |

| 40 | 1.68 | 0.53 | 0.49 |

| 60 | 2.48 | 0.53 | 0.50 |

| 80 | 3.25 | 0.53 | 0.50 |

| 100 | 4.08 | 0.57 | 0.54 |

| 120 | 4.84 | 0.56 | 0.52 |

| 140 | 5.57 | 0.57 | 0.54 |

| 160 | 6.29 | 0.57 | 0.54 |

| 180 | 7.13 | 0.56 | 0.53 |

| 200 | 7.92 | 0.56 | 0.52 |

| Metric | Stage | Number of Images | Training Sample Size (%) | Mean | SD | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Accuracy | Early | 1–80 | 0.03–3.27 | 0.44 | 0.106 | 0.22 | 0.56 |

| Saturation | 100–140 | 4.08–5.72 | 0.56 | 0.016 | 0.53 | 0.58 | |

| Plateau | 160–728 | 6.29–29.17 | 0.58 | 0.015 | 0.56 | 0.61 | |

| Macro F1-score | Early | 1–80 | 0.03–3.27 | 0.39 | 0.120 | 0.18 | 0.53 |

| Saturation | 100–140 | 4.08–5.72 | 0.53 | 0.017 | 0.49 | 0.54 | |

| Plateau | 160–728 | 6.29–29.17 | 0.54 | 0.010 | 0.52 | 0.56 |

References

- Keenan, R.J. Climate Change Impacts and Adaptation in Forest Management: A Review. Ann. For. Sci. 2015, 72, 145–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbati, A.; Marchetti, M.; Chirici, G.; Corona, P. European Forest Types and Forest Europe SFM Indicators: Tools for Monitoring Progress on Forest Biodiversity Conservation. For. Ecol. Manag. 2014, 321, 145–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.-S.; Lee, J.; Lee, S.J.; Son, Y. Methodologies for Improving Forest Land Greenhouse Gas Inventory in South Korea Using National Forest Inventory and Model. J. Clim. Change Res. 2024, 15, 427–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.T.; Chung, S.H.; Kim, C. Carbon Stocksin Tree Biomass and Soils of Quercus Acutissima, Q. Mongolica, Q. Serrata, and Q. Variabilis Stands. J. Korean Soc. For. Sci. 2022, 111, 365–373. [Google Scholar]

- Pu, R. Mapping Tree Species Using Advanced Remote Sensing Technologies: A State-of-the-Art Review and Perspective. J. Remote Sens. 2021, 2021, 9812624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moraes, D.; Campagnolo, M.L.; Caetano, M. Training Data in Satellite Image Classification for Land Cover Mapping: A Review. Eur. J. Remote Sens. 2024, 57, 2341414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarker, I.H. Machine Learning: Algorithms, Real-World Applications and Research Directions. SN Comput. Sci. 2021, 2, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasmadi, M.; Pakhriazad, H.Z.; Shahrin, M.F. Evaluating Supervised and Unsupervised Techniques for Land Cover Mapping Using Remote Sensing Data. Geografia 2009, 5, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, A.; Quegan, S. Comparative Analysis of Supervised and Unsupervised Classification on Multispectral Data. Appl. Math. Sci. 2013, 7, 3681–3694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.D.; Bhavani, Y.L.; Sahithi, V.S.; Kumar, K.A.; Cheepulla, H. Analysing the Impact of Training Sample Size in Classification of Satellite Imagery. In Proceedings of the 2024 5th International Conference on Data Intelligence and Cognitive Informatics (ICDICI), Tirunelveli, India, 18–20 November 2024; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 879–884. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Z.; Gallant, A.L.; Woodcock, C.E.; Pengra, B.; Olofsson, P.; Loveland, T.R.; Jin, S.; Dahal, D.; Yang, L.; Auch, R.F. Optimizing Selection of Training and Auxiliary Data for Operational Land Cover Classification for the LCMAP Initiative. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2016, 122, 206–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramezan, C.A.; Warner, T.A.; Maxwell, A.E.; Price, B.S. Effects of Training Set Size on Supervised Machine-Learning Land-Cover Classification of Large-Area High-Resolution Remotely Sensed Data. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Yang, T.; Choi, C. Mapping Nine Dominant Tree Species in the Korean Peninsula Using U-Net and Harmonic Analysis of Sentinel-2 Imagery. Korean J. Remote Sens. 2025, 41, 243–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korznikov, K.A.; Kislov, D.E.; Altman, J.; Doležal, J.; Vozmishcheva, A.S.; Krestov, P.V. Using U-Net-Like Deep Convolutional Neural Networks for Precise Tree Recognition in Very High Resolution RGB (Red, Green, Blue) Satellite Images. Forests 2021, 12, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheeren, D.; Fauvel, M.; Josipović, V.; Lopes, M.; Planque, C.; Willm, J.; Dejoux, J.-F. Tree Species Classification in Temperate Forests Using Formosat-2 Satellite Image Time Series. Remote Sens. 2016, 8, 734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thapa, B.; Darling, L.; Choi, D.H.; Ardohain, C.M.; Firoze, A.; Aliaga, D.G.; Hardiman, B.S.; Fei, S. Application of Multi-Temporal Satellite Imagery for Urban Tree Species Identification. Urban For. Urban Green. 2024, 98, 128409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, T.; Zhu, H.; Zhang, J.; Yang, Z.; Chai, L.; Xie, J. Patch-U-Net: Tree Species Classification Method Based on U-Net with Class-Balanced Jigsaw Resampling. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2022, 43, 532–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, K.; Zhang, X. An Improved Res-UNet Model for Tree Species Classification Using Airborne High-Resolution Images. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiefer, F.; Kattenborn, T.; Frick, A.; Frey, J.; Schall, P.; Koch, B.; Schmidtlein, S. Mapping Forest Tree Species in High Resolution UAV-Based RGB-Imagery by Means of Convolutional Neural Networks. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2020, 170, 205–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cha, S.; Lim, J.; Kim, K.; Yim, J.; Lee, W.-K. Deepening the Accuracy of Tree Species Classification: A Deep Learning-Based Methodology. Forests 2023, 14, 1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ecosystem, C.D.S. Sentinel-2|Copernicus Data Space Ecosystem. Available online: https://dataspace.copernicus.eu/data-collections/copernicus-sentinel-data/sentinel-2 (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Liu, P.; Ren, C.; Wang, Z.; Jia, M.; Yu, W.; Ren, H.; Xia, C. Evaluating the Potential of Sentinel-2 Time Series Imagery and Machine Learning for Tree Species Classification in a Mountainous Forest. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, M.; Liu, J.; Liu, M.; Zeng, J.; Li, Y. Tree Species Classification Based on Sentinel-2 Imagery and Random Forest Classifier in the Eastern Regions of the Qilian Mountains. Forests 2021, 12, 1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trong, H.N.; Nguyen, T.D.; Kappas, M. Land Cover and Forest Type Classification by Values of Vegetation Indices and Forest Structure of Tropical Lowland Forests in Central Vietnam. Int. J. For. Res. 2020, 2020, 8896310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cha, S.; Lim, J.; Kim, K.; Yim, J.; Lee, W.-K. Uncovering the Potential of Multi-Temporally Integrated Satellite Imagery for Accurate Tree Species Classification. Forests 2023, 14, 746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seeley, M.M.; Wiebe, B.C.; Gehring, C.A.; Hultine, K.R.; Posch, B.C.; Cooper, H.F.; Schaefer, E.A.; Bock, B.M.; Abraham, A.J.; Moran, M.E.; et al. Remote Sensing Reveals Inter- and Intraspecific Variation in Riparian Cottonwood (Populus spp.) Response to Drought. J. Ecol. 2025, 113, 1760–1779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Rivard, B.; Sánchez-Azofeifa, A.; Castro-Esau, K. Intra- and Inter-Class Spectral Variability of Tropical Tree Species at La Selva, Costa Rica: Implications for Species Identification Using HYDICE Imagery. Remote Sens. Environ. 2006, 105, 129–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forest Geographic Information Service. Available online: https://map.forest.go.kr/forest/ (accessed on 27 February 2025).

- MacQueen, J. Multivariate Observations. In Proceedings of the 5th Berkeley Symposium on Mathematical Statisticsand Probability, Berkeley, CA, USA, 21 June–18 July 1965; Volume 1, pp. 281–297. [Google Scholar]

- Pakgohar, N.; Rad, J.E.; Gholami, G.; Alijanpour, A.; Roberts, D.W. A Comparative Study of Hard Clustering Algorithms for Vegetation Data. J. Veg. Sci. 2021, 32, e13042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, D.R.; Bahn, V.; Ciuti, S.; Boyce, M.S.; Elith, J.; Guillera-Arroita, G.; Hauenstein, S.; Lahoz-Monfort, J.J.; Schröder, B.; Thuiller, W.; et al. Cross-Validation Strategies for Data with Temporal, Spatial, Hierarchical, or Phylogenetic Structure. Ecography 2017, 40, 913–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persson, M.; Lindberg, E.; Reese, H. Tree Species Classification with Multi-Temporal Sentinel-2 Data. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 1794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanguri, R.; Laneve, G.; Hościło, A. Mapping Forest Tree Species and Its Biodiversity Using EnMAP Hyperspectral Data along with Sentinel-2 Temporal Data: An Approach of Tree Species Classification and Diversity Indices. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 167, 112671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Z.-H.; Deng, L.; Duan, F.-Z.; Li, X.-J.; Qiao, D.-Y. Angle Effects of Vegetation Indices and the Influence on Prediction of SPAD Values in Soybean and Maize. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2020, 93, 102198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jinguo, Y.; Wei, W. Identification of Forest Vegetation Using Vegetation Indices. Chin. J. Popul. Resour. Environ. 2004, 2, 12–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Guo, R.Y.; Sun, M.; Di, T.T.; Wang, S.; Zhai, J.; Zhao, Z. The Effects of GLCM Parameters on LAI Estimation Using Texture Values from Quickbird Satellite Imagery. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 7366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Zhu, Y.; Song, L.; Su, X.; Li, J.; Zheng, J.; Zhu, X.; Ren, L.; Wang, W.; Li, X. Optimizing Window Size and Directional Parameters of GLCM Texture Features for Estimating Rice AGB Based on UAVs Multispectral Imagery. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1284235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, J.; Kim, K.-M.; Kim, M.-K. The Development of Major Tree Species Classification Model Using Different Satellite Images and Machine Learning in Gwangneung Area. Korean J. Remote Sens. 2019, 35, 1037–1052. [Google Scholar]

- Deur, M.; Gašparović, M.; Balenović, I. Tree Species Classification in Mixed Deciduous Forests Using Very High Spatial Resolution Satellite Imagery and Machine Learning Methods. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 3926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall-Beyer, M. Practical Guidelines for Choosing GLCM Textures to Use in Landscape Classification Tasks over a Range of Moderate Spatial Scales. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2017, 38, 1312–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronneberger, O.; Fischer, P.; Brox, T. U-Net: Convolutional Networks for Biomedical Image Segmentation. In Proceedings of the Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention—MICCAI 2015, Munich, Germany, 5–9 October 2015; Navab, N., Hornegger, J., Wells, W.M., Frangi, A.F., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 234–241. [Google Scholar]

- Axelsson, A.; Lindberg, E.; Reese, H.; Olsson, H. Tree Species Classification Using Sentinel-2 Imagery and Bayesian Inference. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2021, 100, 102318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marconi, S.; Weinstein, B.G.; Zou, S.; Bohlman, S.A.; Zare, A.; Singh, A.; Stewart, D.; Harmon, I.; Steinkraus, A.; White, E.P. Continental-Scale Hyperspectral Tree Species Classification in the United States National Ecological Observatory Network. Remote Sens. Environ. 2022, 282, 113264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mäyrä, J.; Keski-Saari, S.; Kivinen, S.; Tanhuanpää, T.; Hurskainen, P.; Kullberg, P.; Poikolainen, L.; Viinikka, A.; Tuominen, S.; Kumpula, T. Tree Species Classification from Airborne Hyperspectral and LiDAR Data Using 3D Convolutional Neural Networks. Remote Sens. Environ. 2021, 256, 112322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, Y.; Zheng, G.; Du, Z.; Ma, X.; Li, J.; Moskal, L.M. Tree-Species Classification and Individual-Tree-Biomass Model Construction Based on Hyperspectral and LiDAR Data. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemmerling, J.; Pflugmacher, D.; Hostert, P. Mapping Temperate Forest Tree Species Using Dense Sentinel-2 Time Series. Remote Sens. Environ. 2021, 267, 112743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udali, A.; Lingua, E.; Persson, H.J. Assessing Forest Type and Tree Species Classification Using Sentinel-1 C-Band SAR Data in Southern Sweden. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 3237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shetty, S.; Gupta, P.K.; Belgiu, M.; Srivastav, S.K. Assessing the Effect of Training Sampling Design on the Performance of Machine Learning Classifiers for Land Cover Mapping Using Multi-Temporal Remote Sensing Data and Google Earth Engine. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fassnacht, F.E.; Latifi, H.; Stereńczak, K.; Modzelewska, A.; Lefsky, M.; Waser, L.T.; Straub, C.; Ghosh, A. Review of Studies on Tree Species Classification from Remotely Sensed Data. Remote Sens. Environ. 2016, 186, 64–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, W.; Li, J.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, Q.; Yin, G.; Li, A.; Zeng, Y.; Xu, B.; Xu, X.; Zhou, G.; et al. Topographic Correction of Forest Image Data Based on the Canopy Reflectance Model for Sloping Terrains in Multiple Forward Mode. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galvão, L.S.; Breunig, F.M.; Teles, T.S.; Gaida, W.; Balbinot, R. Investigation of Terrain Illumination Effects on Vegetation Indices and VI-Derived Phenological Metrics in Subtropical Deciduous Forests. GIScience Remote Sens. 2016, 53, 360–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, S.-H.; Valdez, M. Tree Species Classification by Integrating Satellite Imagery and Topographic Variables Using Maximum Entropy Method in a Mongolian Forest. Forests 2019, 10, 961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, C.; Zhao, G.; Meng, Y.; Li, B.; Peng, B. The Effect of Topographic Correction on Forest Tree Species Classification Accuracy. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Species | Precision | Recall | F1-Score |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pinus rigida | 0.72 (0.720–0.723) | 0.57 (0.567–0.571) | 0.64 (0.635–0.638) |

| Larix kaempferi | 0.74 (0.736–0.740) | 0.64 (0.637–0.641) | 0.69 (0.683–0.686) |

| Pinus densiflora | 0.56 (0.554–0.559) | 0.54 (0.539–0.543) | 0.55 (0.547–0.551) |

| Pinus koraiensis | 0.71 (0.709–0.712) | 0.77 (0.771–0.774) | 0.74 (0.739–0.742) |

| Quercus acutissima | 0.41 (0.407–0.412) | 0.48 (0.475–0.481) | 0.44 (0.439–0.444) |

| Robinia pseudoacacia | 0.36 (0.358–0.365) | 0.42 (0.418–0.426) | 0.39 (0.387–0.393) |

| Quercus variabilis | 0.46 (0.460–0.464) | 0.60 (0.598–0.603) | 0.52 (0.520–0.524) |

| Quercus mongolica | 0.56 (0.552–0.557) | 0.75 (0.747–0.752) | 0.64 (0.635–0.640) |

| Castanea crenata | 0.63 (0.620–0.630) | 0.40 (0.391–0.399) | 0.48 (0.480–0.488) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, H.; Lee, C.; Woo, H.; Choi, S.-E. Optimal Training Sample Sizes for U-Net-Based Tree Species Classification with Sentinel-2 Imagery. Forests 2025, 16, 1718. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16111718

Lee H, Lee C, Woo H, Choi S-E. Optimal Training Sample Sizes for U-Net-Based Tree Species Classification with Sentinel-2 Imagery. Forests. 2025; 16(11):1718. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16111718

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Heejae, Cheolho Lee, Hanbyol Woo, and Sol-E Choi. 2025. "Optimal Training Sample Sizes for U-Net-Based Tree Species Classification with Sentinel-2 Imagery" Forests 16, no. 11: 1718. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16111718

APA StyleLee, H., Lee, C., Woo, H., & Choi, S.-E. (2025). Optimal Training Sample Sizes for U-Net-Based Tree Species Classification with Sentinel-2 Imagery. Forests, 16(11), 1718. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16111718