Highlights

What are the main findings?

- Lysinibacillus fusiformis solution (LFS) increased mortar flow, compressive strength development.

- LFS decreased the carbonation depth through densification and inhibited CO2 influx.

- LFS induced self-healing, showing an excellent compressive strength recovery rate.

What are the implications of the main findings?

- L. fusiformis overcomes the limitations of previous bacteria tested in highly alkaline concrete.

- Self-healing can mitigate the long-term damage to concrete structures.

- The durability and self-healing capacity will increase the service life of concrete structures.

Abstract

Cracks can reduce the durability of concrete structures. To mitigate the damage caused, self-healing technologies using bacteria and cement-based materials can be utilized. For self-healing, bacteria contained within the matrix are advantageous because they can heal cracks upon introducing oxygen and water under favorable conditions. To our knowledge, this is the first study showing that Lysinibacillus fusiformis isolated from waste concrete induces calcite precipitation in a cement-based material. Replacing 5–20% of the mixing water with the bacterial solution increased mortar flow, and the initial compressive strength increased with the bacterial content. After long-term aging, the compressive strength of the sample with 20% bacterial solution was ~45.6 MPa, the highest among all samples. In terms of durability, the bacterial solution reduced the carbonation depth compared with that of a control sample without added bacteria, and the 20% sample showed 53% higher carbonation resistance than the control. In terms of the self-healing performance, the bacteria-loaded samples showed higher compressive strength recovery rates than the control sample, with the 20% sample showing the highest rate of approximately 131%. Therefore, L. fusiformis derived from waste concrete is a promising candidate bacterium for enhancing the durability and self-healing efficiency of cement composites.

1. Introduction

Concrete is widely used in various industries owing to its excellent compressive strength and durability [1,2]. However, because of its low tensile strength and high brittleness, along with various external factors, cracks inevitably form. These cracks enable harmful substances, such as chloride ions and carbon dioxide, to enter the concrete structure, which has been shown to reduce its strength and durability [3,4,5,6]. Methods that include injecting epoxy into concrete cracks or filling them with repair materials after V-cutting are used to prevent deterioration. However, these methods address cracks only after they have formed and necessitate repeated repairing if the filler material deteriorates over time. Furthermore, while self-healing through unhydrated cement particles is possible, this method is only effective for very small cracks, and the limited presence of unhydrated cement particles often leads to minimal self-healing.

In recent years, various self-healing cement composites have been reported to heal cracks occurring on the surface or inside cement composites without any additional processes or reconstruction procedures. These studies simply applied self-healing materials with the ability to repair cracks to mitigate the deteriorating strength and durability of concrete [7,8,9,10,11]. In the case of self-healing cement composites, studies have utilized bacteria, polymers, and cementitious materials, depending on the material used [12,13,14,15]; these methods are known to improve the durability of concrete by preventing leakage and blocking harmful substances from entering, thereby increasing the lifespan of concrete and reducing maintenance costs [16,17,18,19].

Among the methods for applying self-healing materials, self-healing cement composites containing bacteria have been shown to improve the density and strength of the matrix by precipitating crystalline calcium carbonate outside the cells through the biomineralization action of bacteria attached to the crack surface. This process, which is known as microbially induced calcite precipitation (MICP), fills microcracks and voids in the cement composite, thereby densifying and strengthening the matrix [20,21,22,23].

Bacterially promoted biomineralization induces the formation of calcium carbonate (CaCO3) through various metabolic pathways. Microorganisms that facilitate carbonate mineralization are generally categorized into three major groups: (i) ureolytic bacteria that produce urease, (ii) aerobic bacteria capable of converting organic carbon into inorganic carbon, and (iii) anaerobic denitrifying bacteria. Urea is converted into ammonia and carbon dioxide by the urease produced by ureolytic bacteria, with the ammonia subsequently increasing the local pH through the formation of hydroxide ions that react with carbon dioxide to yield bicarbonate and carbonate ions [7,8]. Ultimately, calcium ions present in the environment combine with the carbonate ions and precipitate as CaCO3 crystals, as represented by the following sequence:

In addition, spore-forming bacteria such as those belonging to the Bacillus and Clostridium genera are able to survive under extreme environmental conditions by producing dormant endospores. These endospores remain structurally intact yet metabolically inactive for extended periods, even in the absence of essential elements, such as carbon sources, nutrients, moisture, and oxygen. Cracks expose the dormant spores to favorable conditions; consequently, they germinate and reinitiate metabolic activity, thereby inducing MICP and contributing to autonomous crack healing [12].

Bacteria can also hibernate as endospores in the healed area, which can be expected to have a secondary crack-healing effect when cracks reform in the future [24,25,26,27].

However, when bacteria are incorporated into cement composites in live form without any additional treatment, the survival rate of bacteria is reduced to approximately 90% or less in the high-pH environment of cement composites, which makes it difficult for bacteria to survive [28,29,30].

Research aiming to overcome this poor survival rate and to exploit the potential for calcium carbonate precipitation through the MICP action of bacteria is currently underway. One strategy is to incorporate bacteria that are viable in high pH environments into aqueous solutions. Alternatively, bacteria have been encapsulated in porous lightweight aggregates, such as expanded clay and expanded vermiculite, and in polymers such as alginates and hydrogels. These capsules are then incorporated into cement composites [31,32,33,34].

For example, Pourfallahi et al. [31] evaluated the self-healing performance of concrete incorporated with bacteria isolated from alkaline soil in the form of an aqueous solution. They reported that Portland pozzolanic cement and Portland cement type 2 samples incorporating Bacillus sp. showed relatively higher healing performance than the control samples. Vigay et al. [32] evaluated the healing performance of concrete with various types of bacteria and found that B. pasteurii and B. subtilis showed relatively better crack healing than the other bacteria. Skevi et al. [33] reviewed the effects of live and dead bacterial cells on the mechanical performance of cement mortars and demonstrated that both live and dead bacteria could increase the strength of cement composites. In the case of dead bacteria, they provided nucleation sites that promoted hydrate production.

Riad et al. [34] evaluated the healing performance of concrete based on the type and number of bacteria (Sporosarcina pasteurii, B. sphaericus) incorporated.

Their results showed that regardless of the type of bacteria, the samples with 10% bacteria showed relatively good healing strength, which was attributed to the filling of microcracks due to the precipitation of calcium carbonate, which was confirmed by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy.

Although a number of studies have incorporated bacteria such as Sporosarcina and Bacillus spp. isolated from highly alkaline environments into concrete, either encapsulated or in aqueous solution, reports involving Lysinibacillus spp. are limited. While previous studies have shown that Sporosarcina pasteurii and Bacillus subtilis are effective MICP agents owing to their high urease activities and spore-forming abilities, they also present limitations, including ammonia overproduction and relatively low tolerances to highly alkaline cementitious environments [35,36]. Recent reports suggest that L. fusiformis may overcome some of these drawbacks because it adapts strongly to saline–alkaline conditions while maintaining effective urease activity [37]. Recent studies [37,38] have revealed the use of L. fusiformis isolated from soil for use in MICP applications, primarily focusing on soil stabilization and tailing sand remediation. Members of the Lysinibacillus genus are commonly isolated from waste environments and are known for their abilities to utilize minerals. Calcium carbonate is reportedly precipitated in rare cases, with L. sphaericus a notable example [39], which suggests that Lysinibacillus spp. are also potential candidates for use in concrete self-healing and repair applications.

However, to our knowledge, no studies have reported the isolation of L. fusiformis from waste concrete or evaluated its applicability to cement-based materials. Accordingly, we investigated the mechanical properties, durabilities, and healing behavior of cement composites that incorporate L. fusiformis isolated from waste concrete.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

The cement used in this study was a type 1 ordinary Portland cement (Sampyo Cement, Seoul, Republic of Korea) with a density of 3.13 g/cm3 and a Blaine fineness of 3820 cm2/g, as shown in Table 1. Natural sand with a density of 2.60 g/cm3 and a fineness modulus of 2.45 was also used.

Table 1.

Composition of the cement used in this study.

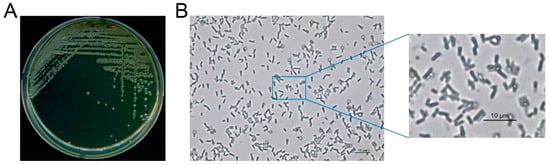

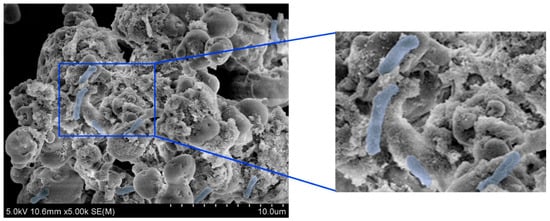

L. fusiformis A15 (KCTC16263BP) was the microbial strain used in this study; it was isolated from waste concrete and deposited at the Korean Collection for Type Cultures (KCTC, Jeongup, Republic of Korea). The morphology and physiological characteristics of L. fusiformis were verified by optical and electron microscopy (Leica ICC5-E, Wetzlar, Germany) prior to each MICP experiment.

In particular, scanning electron microscopy was performed using a field-emission SEM (Hitachi S-4800, Tokyo, Japan). Samples were fixed, dehydrated through a graded ethanol series, dried, and coated with platinum using a sputter coater prior to observation. Imaging was conducted at an accelerating voltage of 5–15 kV under high-vacuum conditions.

The following equations represent the reaction equations for calcium carbonate precipitation by bacteria incorporated inside the cement composite [40]:

Ca2+ + Bacterial cell → Cell-Ca2+

Cell-Ca2+CO32− → Cell-CaCO3

An L. fusiformis solution (LFS) for inoculation was prepared by streaking YA medium and incubating at 30 °C for 24 h to obtain single colonies, which were then inoculated into 10 mL of YB medium. The compositions of these media are presented in Table 2. For primary seeding, the inoculated single colonies were incubated at 30 °C and 180 rpm for 18 h. Next, a 2 L triflask was inoculated with 500 mL of YB medium and 10 mL of primary culture and then incubated at 30 °C and 180 rpm for 24 h. The cultured bacteria were transferred to sterilized centrifuge tubes and centrifuged at 7000 rpm for 1 min to remove the culture medium.

Table 2.

Composition of the media used in this study.

Cells were harvested from a total of 2.5 L of L. fusiformis culture. After removing the medium, the cells were washed once with saline solution and centrifuged again to remove any residual liquid. The final cell pellet was suspended in 1 L of tap water to prepare the LFS (1.87 × 108 cells/mL).

2.2. Mixing Proportions and Sample Preparation

Table 3 shows the mixing proportions used in this study. The water–cement ratio was fixed at 50%, and 0%, 5%, 10%, 15%, and 20% of the water was replaced with the LFS. The range of mixing ratios that did not affect the final properties of the cement composite was explored in preliminary experiments to optimize the LFS mixing ratio, which led to a maximum mixing ratio of 20%. These mortars are hereafter referred to as the control, LFS05, LFS10, LFS15, and LFS20, respectively. To evaluate the compressive strength and compressive strength recovery rate of cement composites incorporating LFS, 50 × 50 × 50 mm cubes were fabricated. For the splitting tensile strength and carbonation depth tests, Ø50 × 100 mm cylindrical samples were fabricated, whereas Ø100 × 50 mm cylinders were fabricated to examine the crack healing performance.

Table 3.

Mixing proportions of the mortars.

The test samples were demolded 24 h after production and then cured in water at 20 °C until the required age.

The mortar flow and compressive strength were measured according to the KS L 5105 [41]. For the compressive strength recovery rate, the samples were subjected to a load of approximately 70% of the 28 d compressive strength, which was taken from the existing literature [42], followed by re-curing; then, the healing compressive strength was measured 7, 28, and 56 d after re-curing.

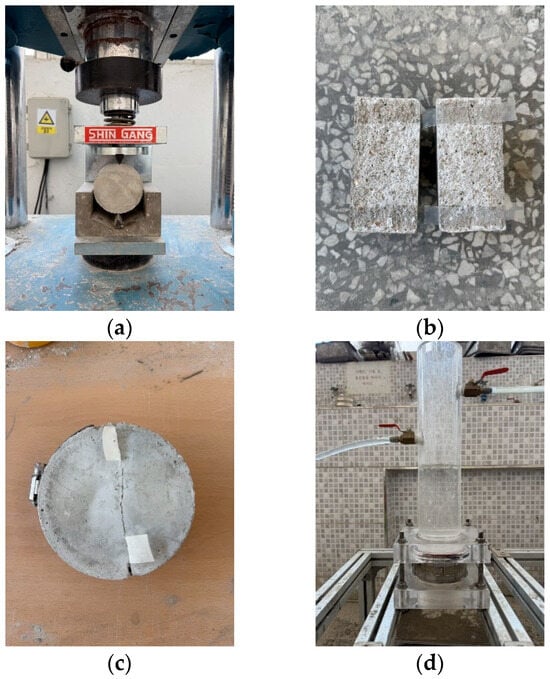

The splitting tensile strength, carbonation depth, and healing ratio were measured in accordance with KS F 2423 [43] and KS F 2584 [44]. The healing ratio was measured according to KCI-CT 114 [45], and the laitance and foreign substances were removed from the cracked area after the sample was split at 28 d, as shown in Figure 1. To induce cracks, a silicone sheet was inserted into the side of the sample, and the sample was then fixed using a clamp. The crack width was fixed to approximately 0.2 mm, and measurements were taken at 7 d intervals until the healing age was 28 d.

Figure 1.

Water permeability testing: (a) splitting, (b) attaching a silicone sheet, (c) fastening the clamp, and (d) measuring the water passing through the crack.

The healing rate based on the measurement results was calculated as

where q(t) represents the unit amount of water passing through the crack over time, and q(0) represents the unit amount of water passing through the crack on the first day of testing. In addition, q(t) was calculated by dividing the amount of water passed (mL) by the crack length (mm) and the measurement period (min), the unit being [mL/(min × mm)].

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Characterizing the L. fusiformis Phenotype

The phenotypic and physiological characteristics of L. fusiformis, which was isolated from waste concrete, were examined prior to evaluating the self-healing performance of cement composites. As shown in Figure 2, optical microscopy revealed that this bacterial strain is composed of colonies and cells with typical morphologies. In addition, FE-SEM at 5000× magnification (Figure 3) revealed that the bacterial cells are rod-shaped. These preliminary results confirm that L. fusiformis is suitable for use in subsequent MICP experiments.

Figure 2.

Phenotypic characteristics of the L. fusiformis used in this study. (A) Colonies of L. fusiformis grown on YA agar medium. (B) Cellular morphology of L. fusiformis observed by optical microscopy at 400× magnification, with a magnified view of the selected region.

Figure 3.

Field-emission scanning electron microscopy (FE-SEM) images of L. fusiformis at 5000× magnification. Bacterial cells (highlighted in blue) display a typical rod-shaped morphology.

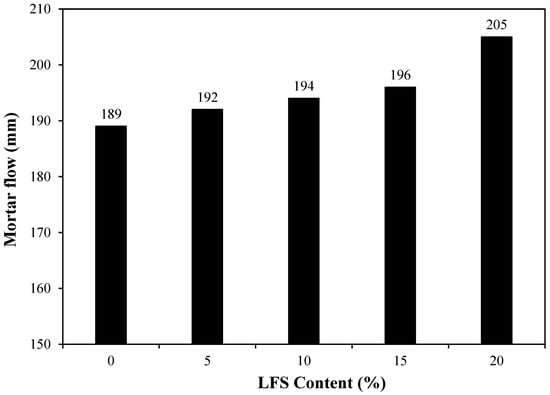

3.2. Mortar Flow

The effect of LFS on the mortar flow was examined, and the results are shown in Figure 4. Evidently, the mortar flow of the control sample was approximately 189 mm, which was the lowest among all samples. By comparison, the mortar flow of LFS05 increased by ~1.6% to ~192 mm. The mortar flow continued to increase with the increasing amount of LFS, and the LFS20 sample showed the highest flow of approximately 205 mm, approximately 8.5% higher than that of the control. The increase in the mortar flow with increasing LFS was attributed to the fact that the main component of the yeast extract used in the bacterial cultures was carbohydrates [46], which are sugar derivatives that act as surface active agents to increase mortar flow [47].

Figure 4.

Mortar flow for various L. fusiformis solution (LFS) samples.

3.3. Compressive Strength

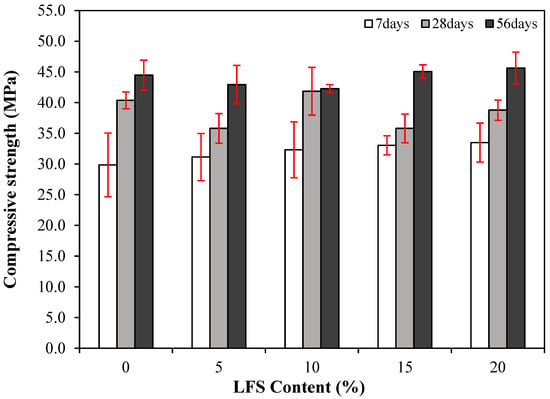

The effect of age on the compressive strength of mortar without and with various amounts of LFS is shown in Figure 5. The 7 d compressive strength of the control sample was the lowest at approximately 29.9 MPa, whereas that of LFS05 was relatively higher at ~31.1 MPa. In addition, the 7 d compressive strength generally increased as the amount of LFS increased, reaching approximately 33.5 MPa for LFS20, which was ~12% higher than that of the control sample. The relatively higher 7 d compressive strengths of the LFS-containing samples compared with that of the control samples are attributed to using the LFS as part of the mixing water. The LFS slightly increased the internal density owing to the bacteria it contained, as observed in previous studies [33].

Figure 5.

Changes in the compressive strength of the various LFS samples with age.

The 28 d compressive strength of the control sample was approximately 40.4 MPa, which decreased slightly for LFS05 to approximately 35.8 MPa. Meanwhile, the 28 d compressive strength of LFS10 was ~41.9 MPa, which is approximately 3.7% higher than that of the control sample. Similar to LFS05, the 28 d compressive strength of LFS15 and LFS20 were also somewhat lower than that of the control sample. The generally similar or lower compressive strengths of the LFS-containing samples were attributed to the yeast extract in the medium, which contained a large amount of carbohydrates that retarded the silicate reaction [46].

Finally, the 56 d compressive strength of the control sample was approximately 44.5 MPa, whereas that of the LFS20 sample was the highest at approximately 45.6 MPa. The LFS15 sample also exhibited a relatively higher 56 d compressive strength (~45.1 MPa) compared with the control sample. Meanwhile, those of LFS05 and LFS10 were approximately 42.3 and 42.9 MPa, respectively, which were not significantly higher than those of the control sample, with differences of ~3.6% and ~4.9%.

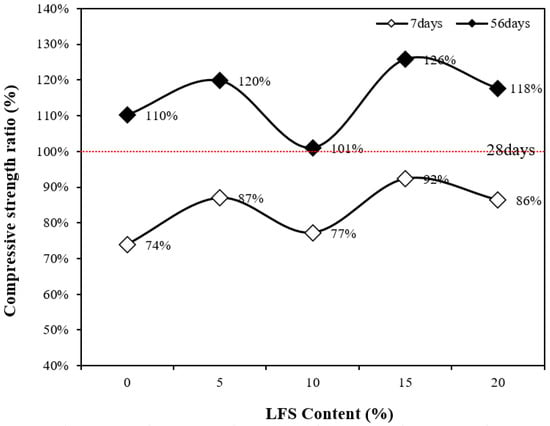

Figure 6 presents the compressive strength development rates at 7 and 56 d with respect to the 28 d compressive strength. Clearly, the compressive strength development rates at 56 d for the LFS-containing samples, except for LFS10, were relatively higher than those for the control sample. This difference is attributed to the silicate reaction, initially delayed by the presence of carbohydrates. However, this reaction then continued to progress over time, and as a result, the 56 d compressive strengths of the LFS15 and LSF20 samples were relatively higher than that of the control sample. In addition, although the development rate of the LFS10 sample was the lowest, its 28 d compressive strength was the highest at approximately 41.9 MPa. This higher reference point is hypothesized to be the reason for its lower development.

Figure 6.

Compressive strength ratio as a function of the LFS content.

3.4. Splitting Tensile Strength

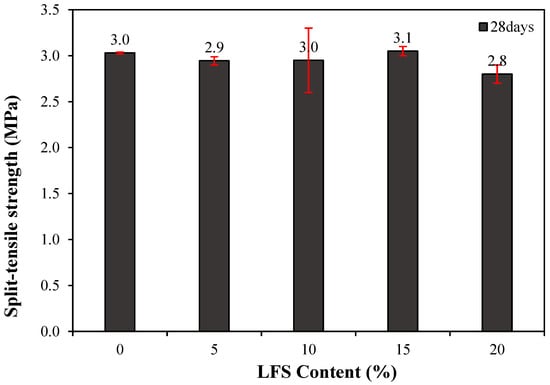

The 28 d splitting tensile strength of the mortar with and without LFS was also examined, as shown in Figure 7. The control sample exhibited a splitting tensile strength of approximately 3.0 MPa, whereas that of LFS05 was ~3.4% lower at ~2.9 MPa. However, as more LFS was incorporated, the splitting tensile strength tended to increase, reaching ~3.0 MPa for LFS10, which is similar to that of the control sample, and approximately 3.1 MPa for LFS15, the highest among the samples and ~3.3% higher than that of the control sample. By contrast, LFS20 demonstrated the lowest tensile strength of all samples at approximately 2.8 MPa, which is ~7.1% lower than the control sample.

Figure 7.

28 d splitting tensile strength of the mortar.

3.5. Carbonation Resistance

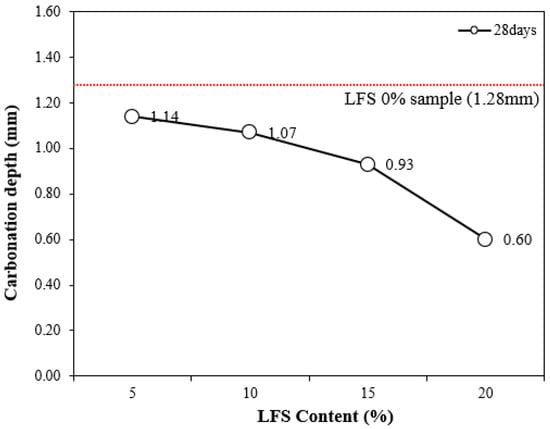

Figure 8 shows the carbonation depth at 28 d of age as a function of the LFS content along with that of the control. The control sample had the highest carbonation depth of ~1.28 mm. By comparison, the carbonation depths of the LFS samples were lower, decreasing with the increasing incorporation of LFS. This is believed to be a result of the increased density because of the embedded bacteria [33].

Figure 8.

Carbonation depth at 28 d for various LFS contents.

In particular, the carbonation depth of LFS20 was approximately 0.60 mm, which was ~53% lower than that of the 0% LFS sample, implying the best carbonation resistance; this was also the sample with the highest 56 d compressive strength.

In general, bacteria-incorporated cement composites are known to inhibit an influx of CO2 because microcracks and voids are filled by the calcium carbonate formed by the MICP action of the bacteria [48]; similarly, this study has shown that the carbonation resistance increased with increasing LFS.

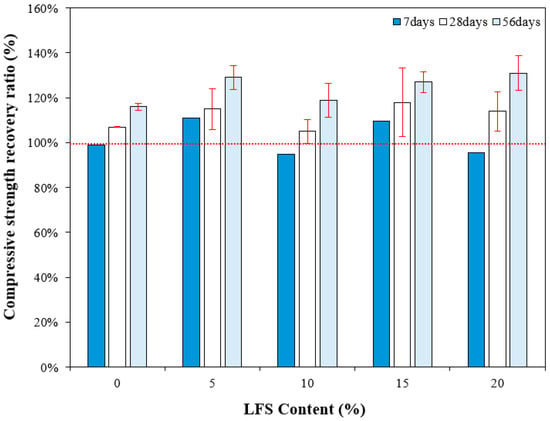

3.6. Compressive Strength Recovery Ratio

Figure 9 compares the 28 d compressive strength of mortar incorporating LFS and the compressive strength recovery rate according to the re-curing age. Evidently, the 7 d compressive strength recovery rate of the control sample after re-curing was approximately 99%. By contrast, those of the LFS05 and LFS15 were ~110–111%; thus, their compressive strengths after loading and then 7 d of re-curing exceeded the original 28 d compressive strength. However, the compressive strength recovery rates of the LFS10 and LFS20 samples were somewhat less than 100% of the 28 d compressive strength at this time, similar to the control sample.

Figure 9.

Compressive strength recovery ratio for various LFS contents after different periods of re-curing.

After 28 d of re-curing, however, the compressive strength recovery rates of the control sample and LFS10 were similar at approximately 107% and 105%, respectively. The LFS05 and LFS15 samples, which showed excellent 7 d compressive strength recovery rates, continued to strengthen after 28 d of re-curing, with recovery rates of 115% and 118%, respectively. The compressive strength recovery rate was the highest in LFS15.

After 56 d of re-curing, the compressive strength recovery rate of the samples using LFS was approximately 119–131%, which is ~12.9% higher than that of the control sample (~116%), and the highest compressive strength recovery rate of approximately 131% was observed with LFS20. Thus, in the samples incorporating LFS, the healing performance improved with the increasing re-curing age, and the compressive strength recovery rate after 56 d of healing was better than that of the control sample. This result is attributed to the progressive bacterial metabolism, facilitated by the inflow of air and moisture through internal microcracks that formed when the load was applied [49].

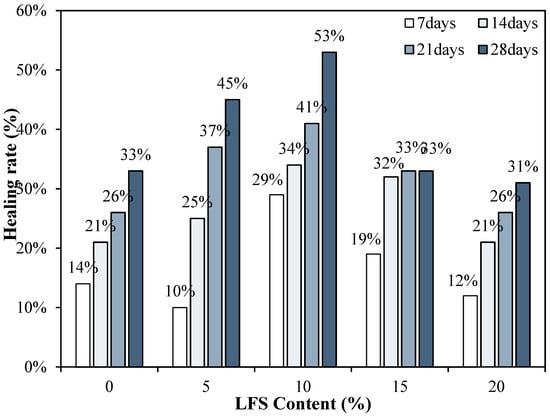

3.7. Healing Ratio

Figure 10 shows the changes in the healing rate of the mortars using LFS. After re-curing for 7 d, the healing rate of the LFS10 sample was the highest at ~29%, and the healing rate of LFS05 was the lowest. Even after 14 d, the healing rate of LFS10 remained the highest at approximately 34%, whereas for LFS05, which had the lowest healing rate at 7 d, the healing rate was approximately 25%, which is ~4% higher than that of the control sample. In addition, the healing rate of LFS20 was approximately 21%, which is the lowest level among the LFS samples but similar to the control sample. After the final healing period of 28 d, LFS10 showed the best healing rate of approximately 53%.

Figure 10.

Healing rates for various LFS contents after different periods of re-curing.

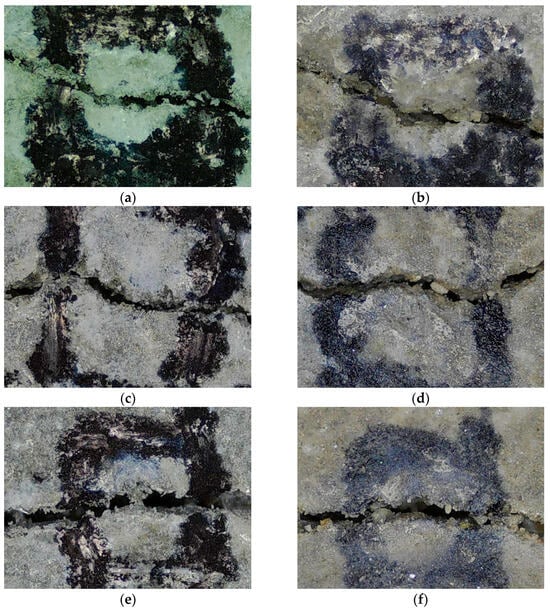

Figure 11 displays crack-healing images for the control, LFS10, and LFS20 samples. The control sample exhibited no significant change in crack size even after 28 d of re-curing. By contrast, LFS10 exhibited a significantly more filled-in crack than the Control sample. Furthermore, in the LFS20 sample, which exhibited the poorest healing performance, the crack size decreased only marginally, consistent with the healing ratio results.

Figure 11.

Crack width in mortars with 0% (control), 5%, 10%, 15%, and 20% LFS (labeled LFSx, where x is the LFS mixing ratio) at the time of cracking (0 d) and after 28 d of re-curing: (a) control 0 d, (b) control 28 d, (c) LFS10 0 d, (d) LFS10 28 d, (e) LFS20 0 d, and (f) LFS20 28 d.

4. Conclusions

Based on the findings of this study, the following conclusions were obtained.

- The mortar flow tended to increase with the increasing incorporation of LFS, which was likely because of the carbohydrate component in the bacterial medium acting as a surface active agent.

- The compressive strength increased with the increasing LFS at the initial age of 7 d. The compressive strength development rate was evaluated on days 28 and 56, and the LFS samples showed relatively higher development rates than the control sample.

- The splitting tensile strengths of the samples with and without LFS were ~2.8–3.1 MPa, showing no significant difference.

- The carbonation depths showed that the carbonation resistance improved with the increasing incorporation of LFS, which was attributed to the incorporation of LFS, densifying the samples and metabolically producing hydrates that inhibited CO2 influx.

- In the case of self-healing performance, the LFS20 showed the highest compressive strength recovery rate of approximately 131%, and in general, the compressive strength recovery rates of the samples incorporating LFS were superior to those of the control sample.

Considering the compressive strength development rates in this study, it is speculated that the compressive strength of the samples with LFS would likely continue to increase further with increasing age beyond 56 d compared with that of the control sample. Thus, additional research is required to evaluate the long-term compressive strength of the LFS-containing samples at ages exceeding 56 d.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.-J.C. and J.-M.K.; Investigation, S.-J.C., H.-Y.S., J.-Y.P. and J.-I.L.; Data Curation, J.-Y.P., H.-Y.S. and J.-I.L.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, S.-J.C. and J.-M.K.; Writing—Review and Editing, S.-J.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by a grant from the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Korea government (MIST) (RS-2024-00405537).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MICP | microbially induced calcite precipitation |

| SEM | scanning electron microscopy |

| LFS | L. fusiformis solution |

References

- Haddadian, A.; Alengaram, U.J.; Ayough, P.; Mo, K.H.; Alnahhal, A.M. Inherent characteristics of agro and industrial By-Products based lightweight concrete—A comprehensive review. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 397, 132298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghadam, M.A.; Izadifard, R.A. Prediction of the Tensile Strength of Normal and Steel Fiber Reinforced Concrete Exposed to High Temperatures. Int. J. Concr. Struct. Mater. 2021, 15, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanhadoust, A.; Madhkhan, M.; Nehdi, M.L. Two-stage multi-objective optimization of reinforced concrete buildings based on non-dominated sorting genetic algorithm (NSGA-III). J. Build. Eng. 2023, 75, 107022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, N.; Ren, L.; Tian, S.; Liu, X.; Zhong, Z.; Deng, Z.; Yan, R. Study on the Fracture Toughness of Polypropylene-Basalt Fiber-Reinforced Concrete. Int. J. Concr. Struct. Mater. 2021, 15, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, D.; Yang, J.; Chu, K.; Guo, S. Effect of alkalinity and pre-cracks of seawater sea-sand concrete on the deterioration of BFRP bars in marine environment. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 468, 140356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olajide, O.D.; Nokken, M.R.; Sanchez, L.F.M. Evaluation of the induced mechanical deterioration of ASR-affected concrete under varied moisture and temperature conditions. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2025, 157, 105942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taheri, S.; Clark, S.M. Preparation of self-healing Additives for Concrete via Miniemulsion Polymerization: Formulation and Production Challenges. Int. J. Concr. Struct. Mater. 2021, 15, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Zheng, Q.; Ashour, A.; Han, B. Self-healing cement concrete composites for resilient infrastructures: A review. Compos. Part B Eng. 2020, 189, 107892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Zhang, R. Factors and mechanism affecting the workability and self-healing performance of microbial self-healing concrete: A review. Structures 2025, 74, 108494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Chen, B.; Sun, W.; Wang, Y. Microbial induced calcium carbonate precipitation study using Bacillus subtilis with application to self-healing concrete preparation and characterization. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 280, 122460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.-I.; Choi, S.-J. Compressive strength, chloride-ion-penetration resistance and crack-recovery properties of self-healing cement composites containing cementitious material capsules and blast-furnace-slag aggregate. J. CO2 Util. 2024, 86, 102916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javeed, Y.; Goh, Y.; Mo, K.H.; Yap, S.P.; Leo, B.F. Microbial self-healing in concrete: A comprehensive exploration of bacterial viability, implementation techniques, and mechanical properties. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2024, 29, 2376–2395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.-I.; Kim, C.-Y.; Yoon, J.-H.; Choi, S.J. Effect of Cementitious Materials on Compressive Strength and Self-healing Properties of Cement Mortars Containing Chitosan-Based Polymer. Archit. Res. 2023, 25, 53–59. [Google Scholar]

- Palin, D.; Wiktor, V.; Jonkers, H.M. A Bacteria-Based Self-Healing Cementitious Composite for Application in Low-Temperature Marine Environments. Biomimetics 2017, 2, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, A.; Zhou, Y.; Bertolesi, E.; Liu, M.; Liao, F.; Fan, M. Factors influencing self-healing mechanisms of cementitious materials. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 393, 131550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, M.A.; Yi, X.; Munir, Q.; Kärki, T.; Wang, J.; Deng, X. Nano-engineerd self-healing concrete: Application, mechanism, challenge and prospect. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 113, 114179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amoorezaei, K.; Ghazijahani-Ghanbari, T. A comprehensive review: Self-healing methods and cementitious composites. Structures. 2025, 72, 108038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kan, L.-L.; Lv, J.-W.; Duan, B.-B.; Wu, M. Self-healing of Engineered Geopolymer Composites prepared by fly ash and metakaolin. Cem. Concr. Res. 2019, 125, 105895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, S.; Bhat, G.S. Progress and challenges in self-healing composite materials. Mater. Adv. 2021, 2, 1896–1926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osta, M.O.; Mukhtar, F. Effect of bacteria on uncracked concrete mechanical properties correlated with damage self-healing efficiency—A critical review. Dev. Built Environ. 2023, 17, 100301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddique, R.; Chahal, N.K. Effect of ureolytic bacteria on concrete properties. Constr. Build. Mater. 2011, 25, 3791–3801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnapriya, S.; Babu, D.V.; Arulraj, P.G. Isolation and identification of bacteria to improve the strength of concrete. Microbiol. Res. 2015, 174, 48–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Tittelboom, K.; De Belie, N.; De Muynck, W.; Verstraete, W. Use of bacteria to repair cracks in concrete. Cem. Concr. Res. 2010, 40, 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šovljanski, O.; Tomić, A.; Markov, S. Relationship between Bacterial Contribution and Self-healing Effect of Cement-based Materials. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parashar, A.K.; Gupta, A. Effects of the concentration of various bacillus family bacteria on the strength and durability properties of concrete: A Review. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2021, 1116, 012162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jogi, P.K.; Lakshmi, T.V.S.V. Self healing concrete based on different bacteria: A review. Mater. Today Proc. 2021, 43, 1246–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, N.; Tafsirojjaman, T.; Shanmugasundaram, N.; Praveenkumar, S.; Li, L.-Z. Smart self-healing bacterial concrete for sustainable goal. Innov. Infrastruct. Solut. 2022, 8, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakubovskis, R.; Ivaškė, A.; Malaiškienė, J.; Urbonavičius, J. Impact of Portland cement type on bacterial viability in biological concrete. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2022, 127, 104413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Hu, X.; Zhang, Q.; Xue, D.; Zhao, Y. Growth environment optimization for inducing bacterial mineralization and its application in concrete healing. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 209, 631–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Algaifi, H.A.; Abu Bakar, S.; Sam, A.R.M.; Ismail, M.; Abidin, A.R.Z.; Shahir, S.; Altowayti, W.A.H. Insight into the role of microbial calcium carbonate and the factors involved in self-healing concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 254, 119258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourfallahi, M.; Nohegoo-Shahvari, A.; Salimizadeh, M. Effect of direct addition of two different bacteria in concrete as self-healing agent. Structures 2020, 28, 2646–2660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijay, K.; Murmu, M.; Deo, S.V. Bacteria based self healing concrete—A review. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 152, 1008–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skevi, L.; Reeksting, B.J.; Hoffmann, T.D.; Gebhard, S.; Paine, K. Incorporation of bacteria in concrete: The case against MICP as a means for strength improvement. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2021, 120, 104056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riad, I.M.; Elshami, A.A.; Elshikh, M.M.Y. Influence of concentration and proportion prepared bacteria on properties of self-healing concrete in sulfate environment. Innov. Infrastruct. Solut. 2021, 7, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achal, V.; Mukherjee, A.; Basu, P.C.; Reddy, M.S. Lactose mother liquor as an alternative nutrient source for microbial concrete production by Sporosarcina pasteurii. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2009, 36, 433–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Muynck, W.; De Belie, N.; Verstraete, W. Microbial carbonate precipitation in construction materials: A review. Ecol. Eng. 2010, 36, 118–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, J.; Song, N.; Meng, C.; Xie, L.; Chang, D. An experimental study to improve the nutrients and the mechanical properties of copper tailing sand in China’s arid zone by biomineralization of locally isolated urease-producing bacteria. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leeprasert, L.; Chonudomkul, D.; Boonmak, C. Biocalcifying potential of ureolytic bacteria isolated from soil for biocementation and material crack repair. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamal, Q.M.S.; Ahmad, V. Lysinibacilli: A biological factories intended for bio-insecticidal, bio-control, and bioremediation activities. J. Fungi 2022, 8, 1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anbu, P.; Kang, C.-H.; Shin, Y.-J.; So, J.-S. Formations of calcium carbonate minerals by bacteria and its multiple applications. SpringerPlus 2016, 5, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KS L 5105; Testing Method for Compressive Strength of Hydraulic Cement Mortars. Korean Standards & Certification Information Center: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2007; p. 5.

- Choi, S.-J.; Bae, S.-H.; Ji, D.-M.; Kim, S.-H. Effects of Capsule Type on the Characteristics of Cement mortars Containing powder Compacted Capsules. Materials 2022, 15, 6773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- KS F 2423; Standard Test Method for Tensile Splitting Strength of Concrete. Korean Standards & Certification Information Center: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2011.

- KS F 2584; Standard Test Method for Accelerated Carbonation of Concrete. Korean Standards & Certification Information Center: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2015.

- KCI-CT114; Constant Water Head Permeability Test Method for the Evaluation of Self-Healing Performance of Mortar. Korea Concrete Institute: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2021.

- Pinto, A.; González-Fonteboa, B.; Seara-Paz, S.; Martínez-Abella, F. Effects of bacteria-based self-healing nutrients on hydration and rheology of cement pastes. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 404, 133142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jumadurdiyev, A.; Ozkul, M.H.; Saglam, A.R.; Parlak, N. The utilization of beet molasses as a retarding and water-reducing admixture for concrete. Cem. Concr. Res. 2005, 35, 874–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, G.; Lv, Y.; Guo, Y.; Yan, Y.; Wu, J.; Liu, W.; Li, Z. Effect of carbonation on the properties of self-healing concrete with expanded perlite as a microbial carrier. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 98, 111430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onyelowe, K.C.; Adam, A.F.H.; Ulloa, N.; Garcia, C.; Valle, A.I.A.; Rodríguez, M.G.Z.; Villacres, A.N.Z.; Shakeri, J.; Anyaogu, L.; Alimoradijazi, M.; et al. Modeling the influence of bacteria concentration on the mechanical properties of self-healing concrete (SHC) for sustainable bio-concrete structures. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 8414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).