Highlights

- A roof structure was introduced in ICP-RIE to suppress ion bombardment, significantly enhancing the Si/SiGe etch selectivity.

- The CF4/N2 chemistry promoted CF4 dissociation and enabled N passivation on Si surfaces, achieving a maximum selectivity of 37:1.

- Process optimization demonstrated that precise control of gas chemistry and plasma parameters is essential for high selectivity and etch uniformity in Si/SiGe multilayers, providing insights for next-generation 3D logic devices.

Abstract

The SiGe/Si multilayer is a critical component for fabricating stacked Si channel structures for next-generation three-dimensional (3D) logic and 3D dynamic random-access memory (3D-DRAM) devices. Achieving these structures necessitates highly selective SiGe etching. Herein, CF4/O2 and CF4/N2 gas chemistries were employed to elucidate and enhance the selective etching mechanism. To clarify the contribution of radicals to the etching process, a nonconducting plate (roof) was placed just above the samples in the plasma chamber to block ion bombardment on the sample surface. The CF4/N2 gas chemistries demonstrated superior etch selectivity and profile performance compared with the CF4/O2 gas chemistries. When etching was performed using CF4/O2 chemistry, the SiGe etch rate decreased compared to that obtained with pure CF4. This reduction is attributed to surface oxidation induced by O2, which suppressed the etch rate. By minimizing the ion collisions on the samples with the roof, higher selectivity, and a better etch profile were obtained even in the CF4/N2 gas chemistries. Under high-N2-flow conditions, X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy revealed increased surface concentrations of GeFx species and confirmed the presence of Si–N bond, which inhibited Si etching by fluorine radicals. A higher concentration of GeFx species enhanced SiGe layer etching, whereas Si–N bonds inhibited etching on the Si layer. The passivation of the Si layer and the promotion of adhesion of etching species such as F on the SiGe layer are crucial for highly selective etching in addition to etching with pure radicals. This study provides valuable insights into the mechanisms governing selective SiGe etching, offering practical guidance for optimizing fabrication processes of next-generation Si channel and complementary field-effect transistor (CFET) devices.

1. Introduction

Because of the scaling down of planar logic devices and their ensuing physical limitations, a new three-dimensional (3D) architecture for devices based on stacked Si channels has emerged. When fabricating structures with this architecture, it is essential to alternate between the epitaxial growth of Si and SiGe, followed by the selective etching of SiGe.

Recently, methods, such as the wet etching method, thermal etching with HCl, and dry etching with plasma have been employed for selective etching of SiGe. Among these, wet etching showed a selectivity of over 150:1 in a Si0.76Ge0.24 multilayer (ML) structure with a 40 nm layer [1]. However, such high-selectivity wet etching has several limitations. First, if the surface oxidation rate is insufficient, SiGe may remain in the etch tunnel [2]. This can hinder the removal of SiGe, potentially reducing selectivity. Second, the drying process after wet etching can lead to pattern collapse [3,4]. For these reasons, dry etching methods for SiGe removal have gained increasing attention.

HCl thermal etching is one approach used for the selective removal of SiGe [5]. However, it requires high temperatures above 600 °C. This high-temperature process can lead to the undesired diffusion of dopants. Therefore, it is considered unsuitable for Si-based semiconductor processes.

Remote plasma can minimize ion bombardment, thereby reducing unwanted substrate modifications. In inductively coupled plasma reactive ion etching (ICP-RIE), the plasma is generated near the substrate, leading to increased dissociation and allowing more reactive species to be available for the etching process. This results in high plasma density, which contributes to both high reactivity and etch rate. Given these advantages, ICP-RIE is proposed as a promising method for selective SiGe etching, as it is a production-effective process [6]. However, ion bombardment in the ICP chamber may cause structural collapse in 3D structures. Thus, etching with radicals alone (without ion bombardment) is highly recommended.

One selective etching mechanism is the selective oxidation of Ge in the SiGe layer. For example, a CF4/O2/N2 gas chemistry allows for the etching of Si compared with SiGe, as the oxidation of germanium (Ge) occurs more readily, leading to the passivation of the SiGe surface while Si is etched away. This indicates that O2 gas should be fed to achieve a high selectivity of SiGe over Si [7,8]. However, studies on the role of N2 and the corresponding SiGe etching mechanism are limited. In this work, we investigated the effects and mechanisms of the addition of O2 and N2 additive gases to CF4 etching gas on Si/SiGe multilayer etching and the effects of radicals and ions on selectivity.

In addition to the technological importance of selective Si/SiGe etching, the environmental implications of fluorocarbon gases should also be considered. CF4 and SF6 are recognized as potent greenhouse gases with high global warming potentials (GWPs). In this study, we tried to minimize the environmental impact by carefully limiting gas leakage outside the chamber and employing a scrubber system. Furthermore, although their effectiveness may differ, the possible use of alternative gases such as NF3 should also be considered in light of environmental concerns.

2. Experimental

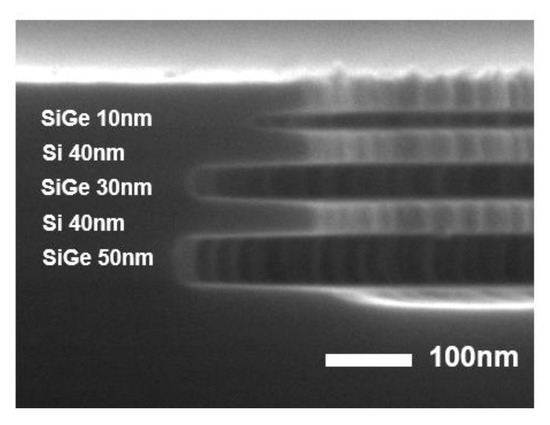

A SiGe/Si ML structure was fabricated through epitaxial growth, alternating between Si0.75Ge0.25 layers with thicknesses of 50, 30, and 10 nm and Si layers with a thickness of 40 nm. This SiGe/Si ML structure was grown using ultrahigh vacuum chemical vapor deposition (UHV-CVD, Jusung Engineering Co., Ltd., Gwangju, Kyeonggi, Republic of Korea) at 550 °C. Disilane (Si2H6, SK Materials, Yeongju, Republic of Korea) and germane (GeH4, SK Materials, Yeongju, Republic of Korea) served as precursors for the Si and SiGe layers, respectively. The SiGe layers were deposited under gas flow conditions of 20-standard cubic centimeters per minute (sccm) for Si2H6 and 50 sccm for GeH4, whereas the Si layers were grown with a Si2H6 flow rate of 20 sccm.

The fabricated ML was patterned through spin coating using GXR-601(MERCK, Darmstadt, Germany) under sequential conditions: 500 rpm for 10 s, 2000 rpm for 30 s, and 500 rpm for 5 s. The spin-coated ML was prebaked at 95 °C for 90 s and then exposed using a 5-μm line-pattern mask. After exposure, the sample was hard-baked at 110 °C for 90 s, developed for 60 s, rinsed with deionized water for 30 s, and dried with nitrogen.

Trenches on the line-patterned ML were formed using reactive ion etching with SF6, CHF3, N2, O2, and Ar gases (Samhung Special Gas, Yeosu, Republic of Korea). After trench formation, the SiGe/Si ML sidewalls were exposed. The SiGe layers were selectively etched using ICP-RIE (ICP-RIE SYSTEM, LAT Co., Ltd., Suwon, Kyeonggi, Republic of Korea) with CF4 and additive gases such as N2, O2, and Cl2(Samhung Special Gas, Yeosu, Republic of Korea). A substrate bias power of 0 W was maintained to enhance selectivity during etching. The substrate bias power controls the ion energy incident on the wafer. A setting of 0 W indicates that no additional RF power was applied to the substrate, thereby minimizing ion bombardment and emphasizing chemical etching. In this study, the ICP source power was kept constant at 100 W. The roof, used to block ion bombardment, was made of Teflon with a thickness of approximately 2 mm. By employing the roof structure, the effect of ion bombardment can be mitigated and the ion flux reduced, while radicals are still able to diffuse through the gap and reach the substrate. As a result, the selectivity can be enhanced. Also, the roof was fabricated from Teflon, which exhibits excellent etch resistance. Because it is scarcely etched, the generation of etch by-products is minimal and thus not expected to influence the substrate etching.

To examine the effects of the process conditions, etching experiments were conducted on SiGe and Si blanket layers and on the SiGe/Si ML. The CF4/(CF4 + N2) gas ratio was varied from 16.7% to 100%, the working pressure was set to 10, 30, and 50 mTorr (1 mTorr ≈ 0.13 Pa), and the total gas flow rate was adjusted between 6 and 60 sccm.

Microstructural analysis of the etched ML was performed using field-emission scanning electron microscopy (SEM, JSM-7001F, JEOL, Tokyo, Japan) with an accelerating voltage of 15 kV. To investigate the etched surfaces of SiGe and Si, X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) analysis was conducted using a K-alpha system (Thermo VG, Waltham, MA, USA) equipped with an Al Kα X-ray source. The X-ray power was set to 12 kV and 3 mA, and the sampling area had a diameter of 400 μm.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. SiGe Selective Etching Using Various Additive Gases

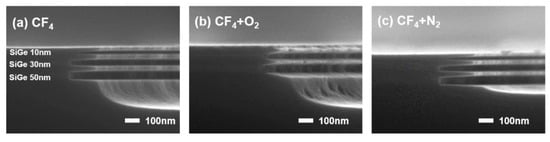

Figure 1 demonstrates the results of the selective etching of Si0.75Ge0.25/Si ML using CF4 combined with various additive gases in an ICP system, including the etching results with pure CF4. Selective etching of Si0.75Ge0.25 layers with thicknesses of 50, 30, and 10 nm was achieved while keeping the Si thickness at 40 nm. Figure 1 shows that the lateral etch depth decreased as the Si0.75Ge0.25 layer thickness decreased. Table 1 summarizes the lateral etch depths for each case, showing a reduction in the lateral etch depth as the Si0.75Ge0.25 layer thickness decreased. This trend could be attributed to the microloading effect [9], which led to a decrease in the etch rates due to the limited diffusion of the by-products and reactant gases in the fine patterns. For the 10 nm thick SiGe layer, the tunnel formed during etching was too narrow for the by-products to escape efficiently, decreasing the lateral etch depth from 183 to 145 nm. If the SiGe layer becomes thinner than 10 nm, the tunnel is expected to narrow further. Consequently, the supply of etchant F radicals and the removal of etching by-products are hindered, leading to a further reduction in the etch rate. A similar effect is also observed in wet etching [1].

Figure 1.

SEM image of the etched SiGe/Si ML with various additive gases.

Table 1.

Lateral etch depth of the SiGe layer in the SiGe/Si ML.

Figure 1b shows the results of adding 5 sccm of O2 to 30 sccm of CF4. Compared with etching in pure CF4, the SiGe-to-Si etch selectivity deteriorated. The top layers of both Si and Si0.75Ge0.25 were almost completely removed. This degradation could be attributed to the introduction of O2, leading to the formation of reactive O radicals and promoting the oxidation of the SiGe surface.

Figure 1c depicts the etching outcome with the addition of 5 sccm of N2 to 30 sccm of CF4. The lateral etch depths for Si0.75Ge0.25 layers of 50, 30, and 10 nm were deeper than those achieved with CF4 alone. From Figure 1, pure CF4 or CF4 with N2 as an additive appears to be a promising gas chemistry for the selective etching of SiGe.

3.2. Etch Properties of CF4/O2 and CF4/N2 Gas Chemistry Under Various Process Conditions

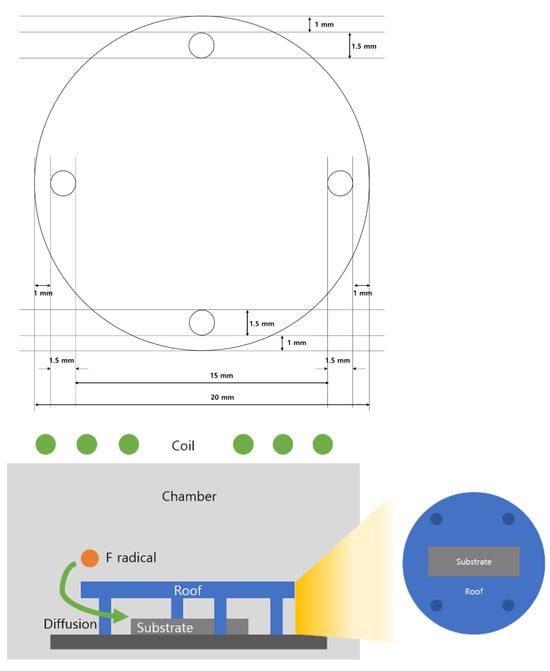

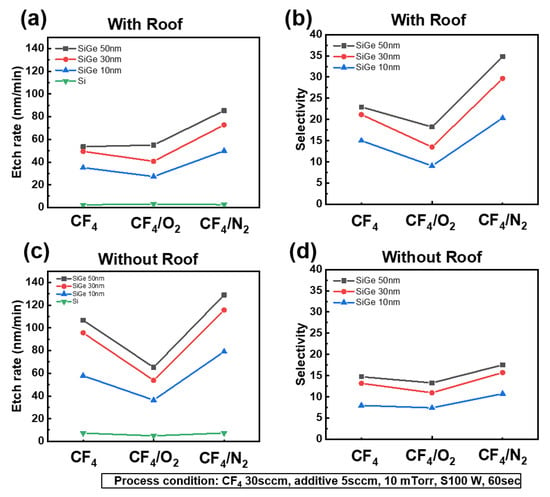

To suppress the self-bias effect, we designed a roof plate. After fabricating the structure shown in Figure 2, we evaluated the etch selectivity with and without the roof. Fluorocarbon species were generated from CF4 gas because of the presence of carbon. From a plasma perspective, this phenomenon is attributed to the self-bias effect and occurs even when the substrate bias power is set to 0 W. Figure 3 presents the etch rate and SiGe/Si selectivity under pure CF4, CF4/O2, and CF4/N2 plasma conditions, with and without the roof. As shown in Figure 3a,c, the addition of O2 promoted the formation of a SiOxFy passivation layer through surface oxidation, which suppressed the etching reaction and consequently reduced the etch rate [10,11]. In contrast, the addition of N2 enhanced CF4 dissociation, thereby increasing the etch rate with and without the roof compared with pure CF4. This behavior is also evident in Figure 3b,d, where N2 addition led to superior selectivity relative to O2 addition, indicating that N2 is a promising additive for achieving high-selectivity SiGe etching.

Figure 2.

Schematic illustration of the roof structure.

Figure 3.

Etch rate (a,c) and SiGe/Si selectivity (b,d) under CF4 plasma with 5 sccm of O2 or N2 additive gas, measured for SiGe layers of 10, 30, and 50 nm thickness, with and without a roof structure.

A comparison of Figure 3a,c shows that the overall etch rate was higher in the absence of the roof structure. However, without the roof, the enhanced ion bombardment also increased the Si etch rate, reducing the selectivity to approximately 15:1, as illustrated in Figure 3d. In contrast, with the roof, as shown in Figure 3b, the selectivity improved to as high as 35:1 with N2 addition, suggesting that ion bombardment accelerated the etching of both SiGe and Si, thereby degrading the selectivity. Therefore, suppressing ion bombardment is essential for achieving high SiGe etch selectivity. For all plasma chemistries and roof conditions, thicker SiGe layers (e.g., 50 nm) exhibited consistently higher etch rates than thinner layers (e.g., 10 nm), potentially because of loading effects. The data presented in Figure 3 emphasize the critical influence of both gas chemistry and ion bombardment modulation on the optimization of selective SiGe etching. Moreover, there were different selective etching mechanisms between the CF4/O2 and CF4/N2 gas chemistries.

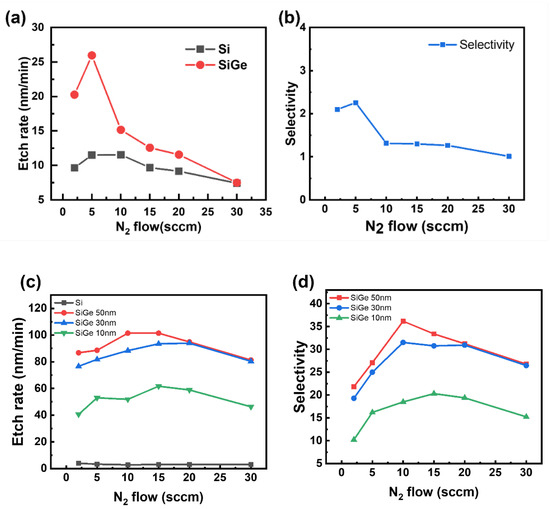

Figure 4 presents the etching results as the N2 flow rate increased while maintaining a constant partial pressure of CF4, with the roof plate placed above the sample. Figure 4a,b show the blanket etching results, while Figure 4c,d present the ML etching outcomes. In Figure 4a, the etch rate reached a maximum of 26 nm/min at an N2 flow rate of 5 sccm and then gradually declined with further increases in N2. Similarly, Figure 4b shows that the selectivity peaked at 5 sccm and decreased at higher flow rates. A comparable trend appeared in the ML etching results: Figure 4d shows that for all three SiGe thicknesses, the selectivity increased up to 10 sccm and then declined.

Figure 4.

Etch rate (a,c) and SiGe/Si selectivity (b,d) under varying N2 flows in SiGe/Si multilayers (ML). Etch rate and SiGe/Si selectivity as a function of N2 flow rate for (a,b) blanket films with a roof and (c,d) ML stacks with varying SiGe thicknesses (10, 30, and 50 nm) with a roof.

The increase in selectivity with moderate N2 addition results from two main mechanisms. First, N2 enhances CF4 dissociation by facilitating the reaction CF2 + N→CNF + F, which increases the concentration of reactive F radicals. Second, N2 promotes nitrogen passivation (N passivation), which selectively passivates the Si surface, enabling the preferential etching of SiGe. However, excessive N2 may lower the electron density in the plasma, reducing the frequency of particle collisions and thereby suppressing the formation of F radicals [12]. The lower electron density suppresses CF4 dissociation and subsequently decreases F radical formation. Because the dissociation of fluorocarbon gases depends largely on electron-impact reactions, a decrease in the number of energetic electrons reduces the number of collisions that are energetic enough to break molecular bonds. Consequently, the concentration of the reactive fluorine species in the plasma decreases. Overall, Figure 4 demonstrates that the N2 flow rate significantly affects both the etch rate and selectivity, highlighting the importance of optimizing N2 flow conditions to achieve effective selective etching.

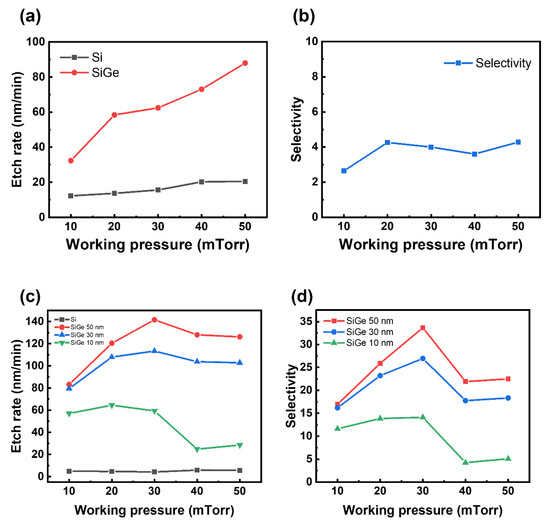

Figure 5 shows the etch rate and etch selectivity as functions of the working pressure, keeping the partial pressure of CF4 constant and the roof plate fixed, for both the blanket samples and the SiGe/Si ML structures. Figure 5a shows that the etch rates of both SiGe and Si increased with increasing working pressure. This could be attributed to the enhanced supply of fluorine radicals due to the increased collision frequency. Figure 5b presents the selectivity for the blanket samples, which remained relatively unchanged with varying working pressure because the etch rate of Si also increased along with that of SiGe as the pressure increased.

Figure 5.

Etch rate and SiGe/Si selectivity as a function of the working pressure. (a,b) Results from the blanket Si and SiGe films with a roof. (c,d) Results from the SiGe/Si ML structures with different SiGe thicknesses (10, 30, and 50 nm) with a roof.

In Figure 5c, the etch rates of the 50 and 30 nm SiGe films increased with the working pressure, reaching peak values of 142 and 113 nm/min, respectively, at 30 mTorr. However, beyond this pressure, the etch rates began to decline, exhibiting a different behavior from those of the blanket wafers. For the 10 nm SiGe film, a significant reduction in the etch rate was observed at pressures exceeding 30 mTorr.

Within the 10–30 mTorr range, increasing the pressure shortens the mean free path (MFP), leading to more frequent collisions and enhanced gas dissociation. This facilitates the generation of fluorine radicals, thereby increasing the etch rate. Additionally, a rise in the working pressure increases the radical-to-ion ratio, contributing to improved etch selectivity [13]. Among the dissociation mechanisms of CF4, the primary reaction (CF4 + e→CF3 + F) that produces F radicals has a relatively low threshold energy of ~5.6 eV, whereas the ionization process (CF4 + e→CF3+ + F + 2e) requires a much higher energy of ~15.9 eV. As the working pressure increases, the average electron energy decreases, making ionization less probable under these conditions [14]. Above 30 mTorr, excessive collisions may cause electrons in the plasma to lose energy, resulting in a lower electron temperature [15]. This, in turn, may suppress the dissociation of process gases and lead to a decreased etch rate. At pressures above a certain threshold, the recombination of reactive species becomes pronounced, which decreases the flux of radicals reaching the substrate [16]. Consequently, such elevated pressures are unsuitable for the etching process. Based on this consideration, 30 mTorr, where the maximum selectivity is achieved, as confirmed in Figure 5d, was selected as the optimal process condition.

In ML structures, unlike in blanket films, structural effects become more pronounced at higher pressures. As the MFP decreases, reactive species struggle to reach sidewall surfaces [16]. This diffusion limitation leads to a reduced etch rate and selectivity when the pressure exceeds a certain threshold.

Figure 6 presents experimental results comparing the initial and optimized etching conditions for Si0.75Ge0.25/Si ML structures using ICP-RIE with a roof. The figure includes cross-sectional SEM images along with quantitative data on etch rates and selectivity. The optimized conditions significantly improved the etch rate of the Si0.75Ge0.25 layer while minimizing that of the Si layer. Moreover, the SEM images illustrate that the ML structure exhibits high etch selectivity with minimal sidewall roughness.

Figure 6.

Etched Si0.75Ge0.25/Si ML under the following conditions: 20 sccm CF4, 10 sccm N2, and 30 mTorr for 60 s with a roof structure.

The improved selectivity was due to better control of the etching process, achieved through plasma modulation and surface passivation effects by adding N2 gas. By adding an appropriate amount of N2 gas to the CF4 plasma, the dissociation of CF4 was enhanced, which increased the concentration of F radicals (Table 2), leading to a higher SiGe etch rate. In addition, the etch selectivity was significantly improved, reaching up to 37:1. This enhancement is attributed to N passivation, where dissociated N radicals adsorb onto the Si surface and form stable Si–N bonds. These bonds effectively suppress the reaction between the F radicals and the Si surface, thereby protecting Si from etching. As a result, under the optimized process conditions, SiGe was etched, whereas the Si layer was protected by surface passivation. Figure 6 shows the results obtained under these conditions. The optimized pressure conditions suppressed GeF4 redeposition and promoted the efficient removal of volatile by-products. In addition, controlled pressure application prevented excessive polymer formation, keeping the etching process governed by surface reactions rather than diffusion-limited transport. The optimized ICP-RIE conditions with the roof structure successfully enhanced the selectivity and etch uniformity in Si0.75Ge0.25/Si ML structures. These findings highlight that the precise tuning of process parameters significantly enhances etch selectivity, enabling greater precision in semiconductor processing.

Table 2.

Summary of the etch rate and selectivity of Si0.75Ge0.25/Si ML under the following conditions: 20 sccm CF4, 10 sccm N2, and 30 mTorr for 60 s with the nonconducting plate.

Additionally, the general trends of the effects of N2 flow and working pressure are not expected to change significantly with Ge concentration. However, since the optimization was performed for Ge 25%, the etch rates and optimal process conditions for other Ge concentrations may differ.

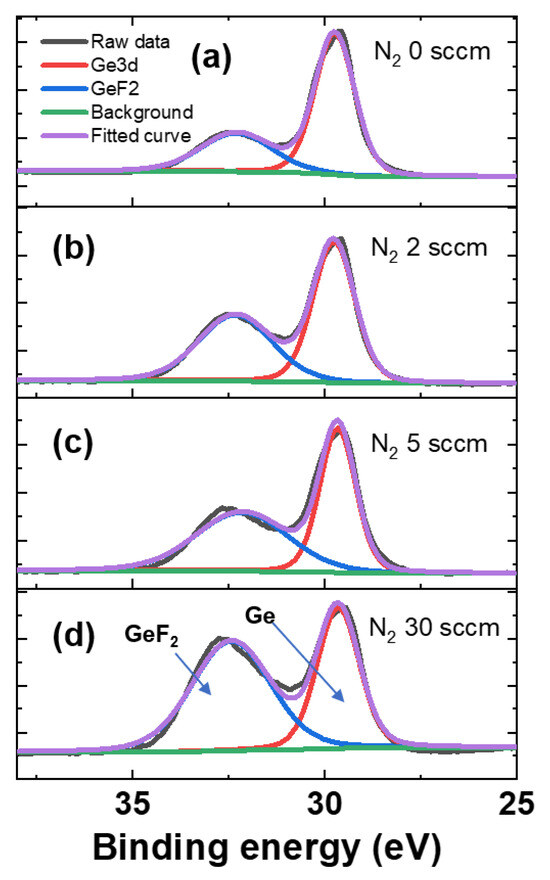

3.3. Selective Etching Mechanism According to an XPS Analysis of the Etched Surfaces of SiGe and Si

To further investigate the selective etching mechanism, XPS analysis was performed on the etched SiGe surfaces. Figure 7 presents the Ge 3d narrow-scan spectra of the SiGe samples etched under varying N2 flow rates while maintaining a fixed CF4 partial pressure. Each spectrum revealed two main components: a Ge peak corresponding to elemental Ge (29.7 eV) and a Ge–F peak (32.3 eV) attributed to Ge–F2 bonding [17,18]. As shown in Figure 7, GeF2 peaks consistently appeared across all conditions, indicating the fluorination of the Ge surface by fluorine radicals generated from CF4 dissociation. These F radicals reacted with the dangling bonds of the Ge atoms exposed at the surface, forming Ge–F2 bonds, typically observed around 32.5 eV [19].

Figure 7.

X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) Ge 3d narrow-scan spectra for SiGe surfaces etched under different plasma conditions: (a) CF4 only, (b) CF4 gas + 2 sccm N2, (c) CF4 + 5 sccm N2, and (d) CF4 + 30 sccm N2.

Quantitative analysis (Table 3) confirms that the fraction of Ge–F2 bonding increases with higher N2 flow rates. When the N2 flow increases up to a certain level, the rise in F radical concentration dominates, leading to a higher etch rate. An increase in N2 promotes CF4 dissociation, thereby increasing the concentration of F radicals. However, beyond that level, the effect of increased Ge–F2 formation on the surface becomes stronger, causing the etch rate to decrease. At high N2 flow rates, more GeF2 forms on the surface, lowering the etch rate. This is because the remaining fluorine blocks new F radicals from reaching the material, slowing down the etching process [20]. In addition, GeF2 has a very high boiling point of approximately 130 °C, making its removal difficult. This inhibitory effect becomes more pronounced with increased N2 flow, as the Ge–F2 fraction increases from 57.09% at 0 sccm to 79.68% at 30 sccm. These results clearly demonstrate that the GeF2 peak intensity is significantly enhanced at 30 sccm, suggesting a strong surface fluorination effect under excessive N2 flow conditions.

Table 3.

Peak fraction at different N2 flow rates.

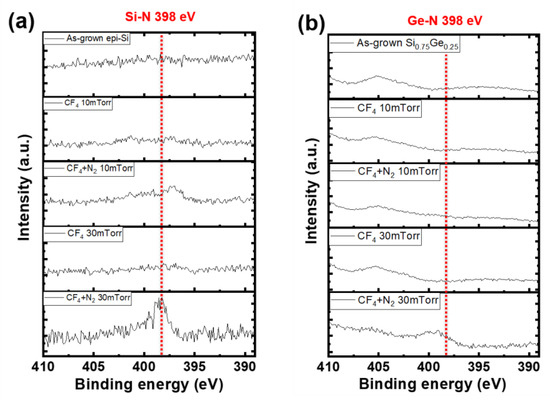

Figure 8 shows N 1s XPS spectra under varying working pressures with or without N2 addition. As shown in Figure 8b, on the SiGe surface, no distinct N-related peak was observed, or it appeared very broad. Therefore, N-passivation was selectively observed on the Si surface under the 30 mTorr condition. As a result, the formation of Si–N bonds suppressed etching on the Si surface, thereby enhancing the etching selectivity over the SiGe layer. Si–N bonds typically appear at ~398 eV in the N 1s region [21,22]. Herein, a clear Si–N peak appeared under CF4 (20 sccm) + N2 (10 sccm) plasma at 30 mTorr, confirming that N passivation occurred on the Si surface under these conditions.

Figure 8.

N 1s spectra of (a) Si and (b) SiGe surfaces obtained under different process pressures with and without N2 gas.

Indeed, as shown in Figure 4, increasing the pressure from 10 to 30 mTorr significantly enhanced the selectivity from 17:1 to 34:1 in the ML. These results suggest that both N2 addition and process pressure play key roles in enabling nitrogen passivation. Notably, the Si–N peaks did not appear under other conditions, where a broad feature was observed without any sharp peak.

Si–N bonds are inherently more stable and chemically favorable than Ge–N bonds. The dissociation energy of Si–N bonds is approximately 355 kJ/mol, indicating a very strong, readily forming covalent bond [23]. In contrast, Ge–N bonds have a lower dissociation energy (~200 kJ/mol) and are energetically less favorable. Furthermore, considering electronegativity differences (Si, 1.90; Ge, 2.01; and N, 3.04), Si–N bonds exhibit greater ionic character, contributing to their higher stability. Accordingly, nitrogen bonding preferentially occurs on Si rather than Ge, resulting in selective Si surface passivation. Compared with the dangling bond state, the Si–N bonded surface is less reactive with fluorine radicals, leading to improved etch selectivity.

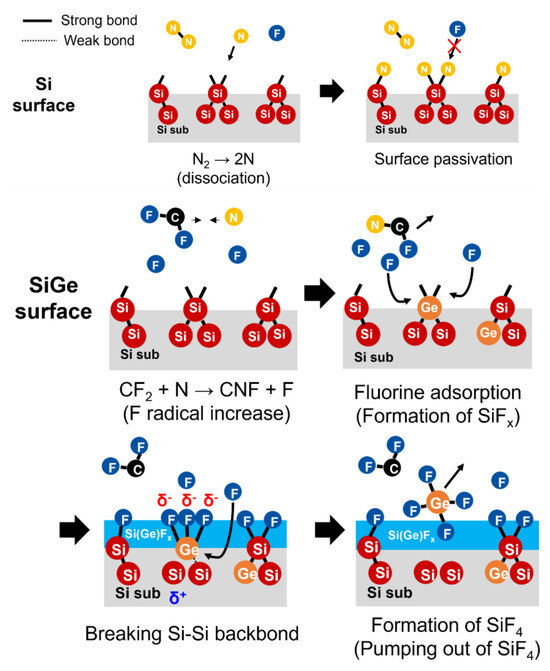

3.4. SiGe Etching Mechanism Based on CF4/N2 Gas Chemistry

Figure 9 illustrates the Si/SiGe etching mechanism using CF4/N2 gas. On the Si surface, dissociated N2 gas produces atomic nitrogen, which bonds with dangling bonds to form Si–N bonds. This N passivation suppresses the adsorption and reaction of fluorine atoms, thereby inhibiting etching—a key factor contributing to improved etch selectivity. In contrast, nitridation is less likely to occur on the Ge surface because of its higher activation energy for nitridation [24].

Figure 9.

Schematic of the Si/SiGe etching mechanism using CF4/N2 gas.

In a CF4/N2 mixed plasma, the CF2 + N→CNF + F reaction generates additional fluorine radicals, increasing the overall concentration of free fluorine radicals. This enhances fluorine-based reactivity by promoting the adsorption of fluorine radicals onto the dangling bonds on the SiGe surface, resulting in the formation of Si(Ge)Fx species. When multiple F radicals bind to Si or Ge atoms, the electrostatic state of Si or Ge shifts to delta-plus (δ⁺), leading to a charge imbalance. This weakens the Si–Si or Si–Ge backbonds, promoting bond breakage—a critical step in the etching process [25]. As the weakened Si–Si backbonds are attacked by incoming F radicals, the number of Si–F bonds increases, leading to the formation of SiF4 from intermediate SiFx species. Because SiF4 has a low boiling point (−86 °C), it becomes a volatile compound that readily desorbs from the surface and is pumped out of the chamber, thereby completing the etching process.

At this stage, the bond energies are 3.25 eV for Si–Si, 3.12 eV for Si–Ge, and 2.84 eV for Ge–Ge. These indicate that the presence of Ge atoms lowers the bond strength [26]. Consequently, the Ge-containing bonds are etched more readily, resulting in a faster etch rate for Ge than for Si.

Finally, the Si(Ge)Fx species react with additional fluorine radicals to form volatile Si(Ge)F4, which is then removed from the surface by the plasma environment and pumped out of the chamber, completing the etching process.

4. Conclusions

This work investigated the etching mechanism of SiGe using CF4/N2 gas chemistry in an ICP-RIE system. In this system, ion bombardment is inherently present and can degrade etch selectivity. Thus, a roof structure was introduced to suppress ion bombardment, improving the etch selectivity from 14:1 to 23:1. The roof structure blocked ion bombardment caused by the plasma self-bias, which helped maintain a high etch selectivity by preventing ion-induced damage.

A comparison of O2 and N2 as additive gases revealed distinct effects. The addition of O2 to CF4 reduced the etch selectivity compared with pure CF4, whereas N2 significantly enhanced it, achieving values up to 35:1. This enhancement was attributed to the N2-induced promotion of CF4 dissociation, increased fluorine radical density, and N passivation on Si surfaces, which improved the SiGe-to-Si etch selectivity.

As the N2 flow rate increased, both the etch rate and selectivity initially increased and reached their maximum values. However, they began to decrease with further increases in N2 flow in both the blanket and ML structures. Optimal selectivity was achieved at moderate N2 flow rates.

XPS analysis confirmed the formation of Si–N bonds, contributing to the selective etching behavior. The increased fluorine radical density facilitated the formation of volatile Si(Ge)F4 by-products, which were subsequently pumped out of the chamber. After process optimization, the etch selectivity increased significantly—from 10:1 to 37:1. These findings demonstrate the importance of precisely tuning the gas chemistry and plasma parameters to achieve high selectivity and etch uniformity in Si/SiGe ML structures, offering valuable insights for next-generation 3D logic device fabrication.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.K. (Jihye Kim); methodology, J.K. (Joosung Kang), J.K. (Jihye Kim); validation, J.K. (Jihye Kim), U.-i.C.; formal analysis, J.K. (Jihye Kim); investigation, J.K. (Jihye Kim), J.K. (Joosung Kang)., D.Y.; resources, J.K. (Jihye Kim); data curation, J.K. (Jihye Kim); writing—original draft preparation, J.K. (Jihye Kim); writing—review and editing, U.-i.C. and D.-H.K.; visualization, J.K. (Jihye Kim); supervision, U.-i.C. and D.-H.K.; project administration, U.-i.C. and D.-H.K.; funding acquisition, D.-H.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the Technology Innovation Programs (RS-2023-00235609 and RS-2024-00402178) funded by the Ministry of Trade, Industry and Energy (MOTIE, Republic of Korea).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| 3D-DRAM | 3D Dynamic random-access memory |

| CFET | Complementary field effect transistor |

| GAA | Gate-all-around |

| ICP-RIE | Inductively coupled plasma reactive ion etching |

| MFP | Mean free path |

| ML | Multilayer |

| sccm | Standard cubic centimeters per minute |

| SEM | Scanning electron microscopy |

| XPS | X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy |

References

- Choi, Y.; Jang, H.; Byun, D.-S.; Ko, D.-H. Selective chemical wet etching of Si1-xGex versus Si in single-layer and multi-layer with HNO3/HF mixtures. Thin Solid Film. 2020, 709, 138230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, Z.; Lin, H.; Wang, H.; Song, Y.; Li, J.; Liu, X.; Du, A.; Miao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Ren, Y. Multiple SiGe/Si layers epitaxy and SiGe selective etching for vertically stacked DRAM. J. Semicond. 2023, 44, 124101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, T.; Fritz, E.-C.; Balakrishnan, D.; Zhang, Z.; Vrancken, N.; Anand, U.; Zhang, H.; Loh, N.D.; Xu, X.; Holsteyns, F. Preventing the capillary-induced collapse of vertical nanostructures. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 14, 5537–5544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oniki, Y.; Altamirano-Sánchez, E.; Holsteyns, F. Selective etches for gate-all-around (GAA) device integration: Opportunities and challenges. ECS Trans. 2019, 92, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Destefanis, V.; Hartmann, J.-M.; Hüe, F.; Bensahel, D. HCl Selective Etching of Si1-xGex versus Si for Silicon on Nothing and Multi Gate Devices. ECS Trans. 2008, 16, 427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wang, W.; Li, Y.; Zhou, N.; Wang, G.; Kong, Z.; Fu, J.; Yin, X.; Li, C.; Wang, X. Study of selective isotropic etching Si1−xGex in process of nanowire transistors. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2020, 31, 134–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oehrlein, G.S.; Chan, K.K.; Jaso, M.A.; Rubloff, G.W. Surface analysis of realistic semiconductor microstructures. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. A Vac. Surf. Film. 1989, 7, 1030–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuo, P.; Kastenmeier, B.; Beulens, J.; Oehrlein, G. Role of N2 addition on CF4/O2 remote plasma chemical dry etching of polycrystalline silicon. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. A Vac. Surf. Film. 1997, 15, 1801–1813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youn, J.; Shin, K.-S.; Park, H.K.; Kim, D. Effects of process parameters on microloading in subhalf-micron aluminum etching. In Microelectronic Device and Multilevel Interconnection Technology II; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Campo, A.; Cardinaud, C.; Turban, G. Investigation of Si and Ge etching mechanisms in radiofrequency CF2-O2 plasma based on surface reactivities. Plasma Sources Sci. Technol. 1995, 4, 398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rachidi, S.; Campo, A.; Loup, V.; Vizioz, C.; Hartmann, J.-M.; Barnola, S.; Posseme, N. Isotropic dry etching of Si selectively to Si0.7Ge0.3 for CMOS sub-10 nm applications. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. A 2020, 38, 033002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagai, M.; Hori, M. Effects of N2 addition on density and temperature of radicals in 60 MHz capacitively coupled c-C4F8 gas plasma. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. A 2006, 24, 1760–1763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boris, D.R.; Petrova, T.B.; Petrov, G.M.; Walton, S.G. Atomic fluorine densities in electron beam generated plasmas: A high ion to radical ratio source for etching with atomic level precision. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. A 2017, 35, 01A104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakano, T.N.T.; Sugai, H.S.H. Partial cross sections for electron impact dissociation of CF4 into neutral radicals. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 1992, 31, 2919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.-X.; Gao, F.; Wang, Y.-N.; Bogaerts, A. The effect of F2 attachment by low-energy electrons on the electron behaviour in an Ar/CF4 inductively coupled plasma. Plasma Sources Sci. Technol. 2012, 21, 025008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Weng, B. Reactive ion etching of PbSe thin films in CH4/H2/Ar plasma atmosphere. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 2021, 124, 105596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, S. Energy calibration secondary standards for X-ray photoelectron spectrometers. Surf. Interface Anal. 1985, 7, 299–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Q.; Musschoot, J.; Schaekers, M.; Caymax, M.; Delabie, A.; Lin, D.; Qu, X.-P.; Jiang, Y.-L.; Van den Berghe, S.; Detavernier, C. TiO2/HfO2 bi-layer gate stacks grown by atomic layer deposition for germanium-based metal-oxide-semiconductor devices using GeOxNy passivation layer. Electrochem. Solid-State Lett. 2011, 14, G27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Meyer, T.; LeDain, G.; Girard, A.; Rhallabi, A.; Bouška, M.; Němec, P.; Nazabal, V.; Cardinaud, C. Etching of GeSe2 chalcogenide glass and its pulsed laser deposited thin films in SF6, SF6/Ar and SF6/O2 plasmas. Plasma Sources Sci. Technol. 2020, 29, 105006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byun, Y.M.; Choi, J.H.; Im, W.B.; Kim, H.-J. Analysis of plasma etching reactivity of bismuth aluminosilicate glasses using fluorine concentration. J. Non. Cryst. Solids 2024, 629, 122883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donley, M.; Baer, D.; Stoebe, T.G. Nitrogen 1s charge referencing for Si3N4 and related compounds. Surf. Interface Anal. 1988, 11, 335–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radi, A.; Leung, K. Competitive bonding of amino and hydroxyl groups in ethanolamine on Si (100) 2× 1: Temperature-dependent X-ray photoemission and thermal desorption studies of nanochemistry of a double-chelating agent. Mater. Express 2011, 1, 144–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lide, D.R. CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics: A Ready-Reference Book of Chemical and Physical Data; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Sugawara, T.; Sreenivasan, R.; McIntyre, P.C. Mechanism of germanium plasma nitridation. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. B Microelectron. Nanometer Struct. Process. Meas. Phenom. 2006, 24, 2442–2448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Zhao, Y.; Teo, B.K. Fluorination-induced back-bond weakening and hydrogen passivation on HF-etched Si surfaces. Phys. Rev. B 2004, 69, 125319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishii, Y.; Scott-McCabe, R.; Yu, A.; Okuma, K.; Maeda, K.; Sebastian, J.; Manos, J. Anisotropic selective etching between SiGe and Si. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 2018, 57, 06JC04. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).