Abstract

Methanol is a promising alternative marine fuel due to its favorable combustion characteristics and potential to reduce exhaust emissions under increasingly stringent International Maritime Organization (IMO) regulations. This study presents a three-dimensional computational fluid dynamics (CFD) analysis of a four-stroke, medium-speed marine engine operating in methanol–diesel dual-fuel (DF) mode. Simulations were performed using AVL FIRE for a MAN B&W 6H35DF engine, covering the in-cylinder process from intake valve closing to exhaust valve opening. Nine operating cases were investigated, including seven methanol–diesel DF cases with equivalence ratios (Φ) from 0.18 to 0.30, one methane–diesel DF case (Φ = 0.22), and one pure diesel baseline. A power-matched condition (IMEP ≈ 20 bar) enabled consistent comparison among fueling strategies. The results show that methanol–diesel DF operation reduces peak in-cylinder pressure, heat-release rate, turbulent kinetic energy, and wall heat losses compared with diesel operation. At low to moderate Φ, methanol DF combustion significantly suppresses nitric oxide (NO), soot, and carbon monoxide (CO emissions), while carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions increase with Φ and approach diesel levels under power-matched conditions. These results highlight methanol’s potential as a viable low-carbon fuel for marine engines.

1. Introduction

Global economic expansion and demographic growth have significantly increased worldwide energy consumption, driving a corresponding rise in maritime transport demand and enlargement of the global merchant fleet [1]. Maritime shipping is responsible for approximately 80–90% of international trade [2], transporting more than 10 billion tons of goods annually across global sea routes [3]. Between 2016 and 2019, global trade grew by 18%, and shipping fuel consumption is projected to increase by 50% between 2012 and 2040 [4]. Despite advances in propulsion and fuel technologies, the sector remains heavily dependent on fossil fuels, particularly Heavy Fuel Oil (HFO), which contains high sulfur fractions. A vessel operating on fuel with 3.5% sulfur content can emit as much pollution as over 210,000 trucks [5]. In 2018, maritime transport generated more than one million tons of greenhouse gases (GHGs) and carbon dioxide (CO2), reflecting increases of 9.6% and 9.3% relative to 2012 [6]. More recent UN statistics show a 4.7% rise in GHG emissions in 2022, with CO2 emissions reaching 847 million tons—23% higher than a decade earlier [2]. Overall, the sector accounts for nearly 3% of global anthropogenic emissions [7].

Approximately 70% of ship emissions occur within 400 km of coastlines [8], exacerbating environmental and public health concerns. Emitted pollutants include CO2, carbon monoxide (CO), methane (CH4), sulfur oxides (SOx) [9,10], nitrogen oxides (NOx) [9,10,11], and particulate matter (PM) [9,10,12,13], all of which negatively affect atmospheric quality and human health [14]. The IMO’s Third GHG Study (2014) projected that maritime emissions could rise by 50–250% by 2050 [15], potentially accounting for 15% of global CO2 emissions by mid-century [12], posing a substantial challenge to meeting Paris Agreement and Kyoto Protocol commitments. Consequently, the IMO has introduced progressively stricter emission regulations for the sector [12,16].

The regulatory framework for ship emissions began with MARPOL Annex VI, adopted in 1997 and enforced in 2005, which set limits on air pollution from ships [17]. The NOx Technical Code (MEPC 58) entered into force in 2010, introducing limits for engines above 130 kW [18]. Sulfur Regulation 14 (MEPC 59) mandated a global sulfur cap reduction from 3.50% to 0.50% by January 2020. To address energy efficiency, the IMO established the Energy Efficiency Design Index (EEDI) at MEPC 62 (effective 2013), the Ship Energy Efficiency Management Plan (SEEMP), and the Data Collection System (DCS) for ships over 5000 GT, effective in 2018 [17]. More recently, the Energy Efficiency Existing Ship Index (EEXI) and Carbon Intensity Indicator (CII) were adopted at MEPC 75, entering into force in 2023 [19,20]. The IMO’s long-term climate ambition targets a 40% reduction in CO2 intensity by 2030 and a 50% reduction in total GHG emissions by 2050 compared with 2008 [21], requiring a profound shift in marine fuel composition. Estimates suggest that 70% of current marine fuels must be replaced or substantially modified to meet future targets [12,22].

Against this regulatory backdrop, interest in alternative marine fuels has grown rapidly. While aftertreatment technologies allow the continued use of HFO, fuels such as Liquified Natural Gas (LNG) and methanol have gained prominence due to their lower pollutant emissions. LNG, however, requires cryogenic storage and introduces significant design constraints, whereas methanol remains liquid at ambient conditions, is widely produced from natural gas, and is readily available in major ports [23]. Methanol’s physicochemical properties further support its adoption: it is fully miscible with water, facilitating storage in void spaces of double-hull ships, and spills dilute rapidly, minimizing environmental harm. Toxicity assessments show methanol concentrations lethal to aquatic life are orders of magnitude higher than those for diesel or gasoline, making harmful exposure unlikely in spill scenarios [24]. Its flammability characteristics resemble those of diesel rather than cryogenic gases, and methanol pool fires are generally easier to control [25]. These advantages have supported early commercial adoption, including MAN’s ME-LGI injection system for DF methanol combustion [12,26].

Methanol provides several combustion-related advantages relevant to marine applications. The absence of sulfur and carbon–carbon bonds prevents SOx formation and significantly reduces particulate matter emissions. Its lower adiabatic flame temperature can suppress NOx formation, and water-addition strategies have been shown to enable Tier III NOx compliance without exhaust gas recirculation or selective catalytic reduction [27,28,29]. Numerous studies report substantial reductions in NOx, SOx, PM, and CO2 when methanol replaces marine gas oil [18]. While methanol produced from natural gas can yield slightly higher lifecycle GHG emissions than HFO or marine diesel oil (MDO), renewable methanol derived from biomass or e-methanol pathways can reduce GHG emissions by 56% or more [12,30], and in some cases by as much as 95% for CO2 and 80% for NOx [31,32].

In parallel, methanol’s combustion properties have stimulated extensive research into methanol–diesel dual-fuel (DMDF) operation. Methanol’s low cetane number and high latent heat of vaporization complicate ignition [33], but pilot-assisted combustion strategies enable stable operation [34]. Experimental studies indicate substantial soot and PM reductions in DMDF engines, though increases in unburned hydrocarbons and CO may occur depending on equivalence ratio and combustion phasing [35]. Computational fluid dynamics studies have further clarified ignition behavior, spray–mixing interactions, fuel–air stratification, and pollutant formation mechanisms, but significant research gaps persist. Most prior CFD studies examine automotive-scale or single-cylinder engines; many rely on simplified chemical mechanisms; systematic equivalence-ratio sweeps at matched power outputs remain limited; and direct comparisons of methanol with both diesel and natural gas under consistent boundary conditions are rare.

To address these gaps, this study performs a comprehensive CFD investigation of a large-bore, four-stroke, medium-speed marine engine—the MAN B&W 6H35DF—operating in methanol–diesel DF mode. Using AVL FIRE, simulations capture the full in-cylinder process from intake valve closing (IVC) to exhaust valve opening (EVO). Nine operating cases are examined, including seven methanol–diesel DF cases with equivalence ratios (Φ) ranging from 0.18 to 0.30, one pure-diesel case, and one natural-gas DF case (Φ = 0.22). The Φ = 0.22 methanol case produces an indicated mean effective pressure (IMEP) equal to that of the pure-diesel mode and is used as a reference for power-equivalent emission comparisons. This systematic approach enables detailed evaluation of methanol’s influence on combustion behavior, engine performance, and pollutant formation, and provides a direct comparison with diesel and natural gas.

The novelty of this study lies in applying a fully transient 3-D CFD framework to a medium-speed marine engine, conducting a systematic equivalence-ratio sweep for methanol DF operation, performing power-equivalent comparisons across diesel, methanol, and natural gas, and interpreting the results within the context of IMO decarbonization targets. The findings offer new insights into the viability of methanol as a low-carbon marine fuel and support future developments in clean maritime propulsion.

2. Methodology

2.1. Engine Specifications

The engine investigated in this study is a four-stroke, medium-speed DF marine engine, specifically the 6H35DF, manufactured by MAN B&W, Augsburg, Bavaria, Germany. The engine consists of six cylinders, each equipped with two intake valves and two exhaust valves, and is designed to operate at a rated speed of 720 rpm, delivering a total power output of 2880 kW. The engine has a cylinder bore of 350 mm and a piston stroke of 400 mm, corresponding to a compression ratio of 13.5:1. The connecting rod length is 870 mm, and the IMEP under rated conditions is approximately 20 bar. The specifications of the engine are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Primary specifications of the research engine.

The combustion chamber features an ω-type piston bowl geometry, which promotes air–fuel mixing and combustion stability under both diesel and DF operating modes. A single centrally mounted pilot fuel injector is installed on the cylinder cover. The pilot injector is equipped with 12 identical nozzle holes and an injection spray angle of 155°, ensuring uniform fuel distribution within the combustion chamber.

The engine is capable of operating smoothly in two distinct modes: conventional diesel mode and DF mode. In diesel mode, the engine operates solely on diesel fuel following a conventional compression-ignition (CI) combustion process. In DF mode, methanol is used as the primary fuel, while a small quantity of diesel is injected as pilot fuel to initiate combustion. In this mode, methanol is supplied via fuel port injection into the intake port through a dedicated valve mounted in the suction passage. The injected methanol mixes with the intake air upstream of the intake valves, forming a premixed methanol–air mixture that is inducted into the cylinder during the intake process. Combustion is subsequently initiated by direct injection of diesel pilot fuel into the cylinder near top dead center (TDC).

This engine configuration allows flexible operation under both diesel and methanol–diesel DF conditions and provides a representative platform for investigating combustion behavior and emission characteristics relevant to modern medium-speed marine engines.

2.2. Numerical Platform and Simulation Scope

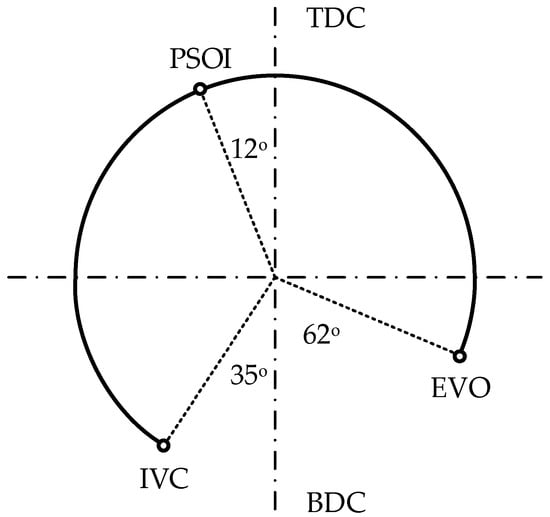

All simulations were performed using the commercial CFD software AVL FIRE, version R2018a, which has been widely validated for combustion and emission prediction in gasoline, diesel, and DF engines. Among the available modeling environments, the ESE Diesel platform, provided by AVL FIRE version 2018a was selected. This platform simulates only the closed-valve portion of the engine cycle, from IVC to EVO, thereby reducing computational cost while retaining the key physical processes governing compression, combustion, and expansion. A schematic of the simulation window is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

A schematic of the simulation window.

The numerical workflow included construction of the three-dimensional computational domain of the combustion chamber, generation of a deforming mesh accounting for piston motion, definition of the pilot diesel injector geometry, solution of the governing transport equations, and post-processing of combustion and emission results.

2.3. Computational Dynamic Mesh

The three-dimensional engine combustion chamber geometry was constructed using the AVL FIRE ESE-Diesel platform version 2018a, followed by generation of the computational mesh for CFD analysis. Owing to the axial symmetry of the combustion chamber and the presence of a fuel injector with twelve identical nozzle holes, a 1/12 sector model of the full geometry was employed to reduce computational cost. Periodic boundary conditions were applied at the sector interfaces to preserve the physical symmetry of the flow and combustion processes.

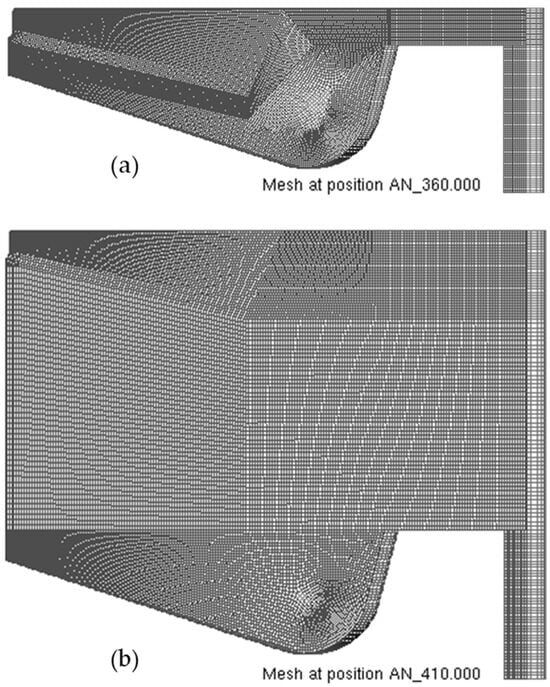

A dynamic mesh strategy was used to account for piston motion throughout the simulated crank-angle range. Mesh deformation algorithms were employed to maintain cell quality during large volume changes. Local mesh refinement was applied in regions of strong gradients, particularly near the injector nozzle and within the piston bowl, to accurately capture spray evolution, combustion development, and emission formation. The computational mesh is presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Computational mesh for simulation: (a) at 360 CADs (TDC) and (b) at 410 CADs.

All simulations were executed in serial mode on a Windows workstation with a twelve-core processor, AMD Ryzen 7 chip, 32 GB RAM, with each case requiring approximately 36 h of CPU time. This meshing strategy provided an effective balance between computational efficiency and numerical accuracy for resolving in-cylinder flow, combustion, and emission formation.

2.4. Simulation Cases

A total of nine simulation cases were considered in this study to investigate the combustion and emission characteristics under different fueling strategies. Seven cases correspond to methanol–diesel DF operation, in which methanol serves as the primary fuel and diesel is used as the pilot fuel. For these cases, the global equivalence ratio (Φ) was systematically varied from 0.18 to 0.30, with an increment of 0.02 (Φ = 0.18, 0.20, 0.22, 0.24, 0.26, 0.28, and 0.30), in order to examine the influence of methanol mixture strength on engine performance and emission formation. When Φ gradually increases from 0.18 to 0.3, the diesel pilot injection duration remains constant (15 CADs), meaning the amount of diesel fuel (or the energy produced by the diesel) remains constant; only the total amount of energy supplied to the engine increases proportionally with Φ. The diesel energy fraction (DEF) and fuel substitution ratio for these methanol-diesel DF modes are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Diesel Energy Fraction (DEF) and fuel substitution ratio for methanol-diesel DF modes.

In the present study, the equivalence ratio (Φ) is defined exclusively based on the premixed primary fuel, i.e., methanol for methanol–diesel dual-fuel (DF) operation and methane for methane–diesel DF operation. The Φ value represents the global equivalence ratio of the premixed fuel–air mixture inducted into the cylinder at intake valve closing. The pilot diesel fuel, which is directly injected near top dead center to initiate combustion, is not included in the Φ definition. Its injected mass and injection timing are kept constant across all DF cases, ensuring that variations in Φ reflect changes in premixed methanol (or methane) quantity only.

In addition, one natural gas–diesel DF case was simulated at an equivalence ratio of Φ = 0.22. This case was designed to produce an IMEP comparable to that of the diesel-only operating condition, thereby enabling a power-equivalent comparison between methanol–diesel, methane–diesel, and pure diesel operation.

Finally, a pure diesel case was included as the baseline reference. In this mode, the engine operates under conventional compression-ignition conditions with diesel as the sole fuel, corresponding to an equivalence ratio of Φ = 0. Together, these nine cases provide a comprehensive framework for evaluating the effects of fuel type and equivalence ratio on combustion behavior, engine performance, and exhaust emission characteristics.

To ensure a strictly power-matched comparison, the total chemical energy supplied per cycle was kept constant for the diesel baseline, methanol–diesel DF at Φ = 0.22, and methane–diesel DF at Φ = 0.22. For all three cases, the total fuel energy input was approximately 80 kJ per cycle per cylinder, corresponding to an IMEP of about 20 bar. In the DF modes, the diesel pilot contributed approximately 5% of the total fuel energy and was kept constant across all cases, while the remaining 95% was supplied by the premixed primary fuel (methanol or methane). As a result, differences in combustion behavior and emissions under power-matched conditions can be attributed primarily to fuel properties and combustion mode rather than to variations in total energy input. For DF operation, the diesel pilot energy was kept constant at 4.0 kJ per cycle per cylinder for all cases. Power-matched comparisons were conducted at Φ = 0.22, corresponding to a total fuel energy input of 80.0 kJ per cycle per cylinder.

In this study, diesel fuel was represented using a single-component surrogate (C13H23), which is commonly adopted in engine CFD studies to approximate the average physical and ignition characteristics of real diesel fuels. While actual marine diesel consists of a multi-component mixture with a broad boiling range, the use of a single-component surrogate enables robust and computationally efficient spray, evaporation, and ignition modeling within the ECFM-3Z framework. This simplification may influence absolute predictions of spray evaporation dynamics and ignition delay; however, because the same surrogate fuel is applied consistently across all simulated cases, the comparative trends in combustion behavior and emissions remain physically meaningful. The simulation cases in this study are presented in Table 3. The thermophysical and chemical properties of fuels used in this study are presented in Table 4. Meanwhile, Table 5 summarises the fuel quantities for all simulation cases calculated for each cycle, per cylinder.

Table 3.

A summary of the simulation cases in the study.

Table 4.

Thermophysical and chemical properties of fuels [36,37,38].

Table 5.

Fuel quantities for all dual-fuel cases (per cycle, per cylinder).

The fuel properties listed in Table 4 correspond to the default or recommended values used in the AVL FIRE fuel property database for single-component diesel surrogates, methane, and methanol. Minor variations may exist among different database versions; however, the selected values fall within the ranges reported in authoritative combustion literature and do not affect the comparative trends discussed in this study.

2.5. CFD Models

Turbulent flow inside the cylinder was modeled using the k–ζ–f turbulence model, a four-equation formulation derived from the conventional k–ε model. This turbulence model offers improved numerical stability and enhanced accuracy in near-wall regions and flows with strong pressure gradients, making it well-suited for transient in-cylinder simulations of medium-speed marine engines.

The combustion process was simulated using the Species Transport model coupled with the three-zone Extended Coherent Flame Model (ECFM-3Z). The species transport formulation solves conservation equations for individual chemical species, accounting for convection, diffusion, and reaction source terms, while the ECFM-3Z model distinguishes premixed, diffusion, and burned gas zones. This combination enables accurate representation of the mixed combustion modes characteristic of methanol–diesel DF engines and has been successfully applied in previous studies of gasoline, diesel, and DF combustion.

It should be noted that the ECFM-3Z combustion model employed in this study does not resolve detailed chemical kinetic mechanisms. Instead, ignition and heat release are modeled using a flame-surface-density-based approach, in which premixed and diffusion combustion zones are distinguished and the reaction rate is governed primarily by turbulent mixing and flame propagation [39]. In dual-fuel operation, auto-ignition is initiated exclusively by the diesel pilot spray, which is modeled using the Diesel Ignited Gas Engine model. The premixed methanol–air mixture does not undergo auto-ignition; its combustion is triggered by the ignition of the diesel pilot and subsequently proceeds in a turbulence-controlled manner. As a result, ignition delay predictions primarily reflect diesel pilot ignition behavior, while methanol influences combustion through charge cooling, mixture strength, and flame propagation characteristics rather than through detailed chemical kinetics.

Regarding methanol combustion modelling, methanol is treated as a premixed gaseous fuel characterized by its thermophysical properties and global stoichiometry, while intermediate oxidation pathways are not explicitly represented. Nitric oxide formation is calculated using the Extended Zeldovich mechanism and is therefore primarily sensitive to local temperature and oxygen availability rather than detailed fuel chemistry.

Pilot diesel injection was modeled using the Diesel Nozzle Flow sub-model, which corrects injection velocity and initial droplet size to account for internal nozzle flow and cavitation effects. Liquid fuel sprays were treated using a Lagrangian discrete droplet approach. Droplet breakup was simulated using the WAVE model, based on Kelvin–Helmholtz instability theory, while droplet evaporation was modeled using the multi-component evaporation model. Interactions between fuel droplets and chamber walls were described using the Walljet1 model, derived from the Naber–Reitz spray–wall impingement formulation, enabling realistic prediction of droplet rebound, spreading, and secondary atomization.

The ignition behavior of the methanol–diesel DF system was modeled using the Diesel Ignited Gas Engine model, in which auto-ignition of the diesel pilot initiates combustion of the premixed methanol–air charge. This approach allows prediction of ignition delay, combustion phasing, and heat-release characteristics under DF operating conditions.

Nitric oxide (NO) formation was predicted using the Extended Zeldovich mechanism, consisting of seven chemical species and three elementary reactions, which provides reliable NO predictions over a wide range of equivalence ratios and combustion temperatures. Soot formation was simulated using a kinetic soot model, accounting for soot inception, surface growth, and oxidation during combustion. A summary of the CFD models used in this study is presented in Table 6.

Table 6.

Summary of the CFD models.

Post-processing of the simulation results was conducted to analyze in-cylinder pressure histories, temperature distributions, combustion development, and emission formation. Key performance and emission indicators, including ignition delay, heat-release characteristics, and trends in NO and soot emissions, were extracted to evaluate the influence of fueling strategy and operating conditions on combustion and emission behavior.

2.6. Boundary and Initial Conditions

The boundary and initial conditions adopted in this study were derived from the technical documentation of the actual engine provided by the manufacturer. Impermeable wall boundary conditions were applied to the cylinder head, piston surface, and cylinder liner. Constant wall temperatures were prescribed, with the cylinder head and piston maintained at 297 °C, while the cylinder liner temperature was set to 197 °C. Owing to the axial symmetry of the combustion chamber, cyclic (periodic) boundary conditions were imposed on the circumferential cutting surfaces of the computational domain.

The cylinder head, piston, and liner wall temperatures were prescribed as fixed values for all operating cases to represent time-averaged component temperatures under steady full-load operation. While the gas-side thermal boundary layer is resolved through local temperature gradients and turbulence modeling, transient wall temperature variation and solid heat conduction are not explicitly simulated. This approach represents a modeling simplification commonly adopted in closed-cycle engine CFD studies, particularly when conjugate heat-transfer data are unavailable. This simplification provides consistent thermal boundary conditions across all cases and enables reliable comparative analysis of combustion and emission trends.

In practical marine engines, wall temperatures are primarily governed by the cooling system and thermal inertia of engine components and are not expected to vary significantly with short-term changes in combustion mode. Using identical wall temperatures across all cases ensures consistent boundary conditions and allows differences in wall heat loss to be attributed primarily to gas-side combustion behavior rather than imposed wall-temperature variations. Nevertheless, this assumption may affect the absolute magnitude of predicted wall heat fluxes, particularly for fuels with different combustion temperature levels, and should be considered when interpreting WHR results.

The simulations were conducted over the closed-valve portion of the engine cycle, starting from IVC at 35 crank angle degrees (CAD) after bottom dead center (ABDC) and ending at EVO at 62 CAD before bottom dead center (BBDC). At IVC, the in-cylinder pressure and temperature were initialized to 3.5 bar and 47 °C, respectively. In dual-fuel operation, the port-injected methanol (or methane) was assumed to be homogeneously premixed with the intake air at intake valve closing (IVC). This assumption reflects the long residence time available for mixing during the intake process in medium-speed marine engines operating at 720 rpm, as well as the high volatility and single-component nature of methanol, which promote rapid evaporation and mixing. While some degree of mixture stratification may exist in practical engines due to intake-flow non-uniformities and wall interactions, explicitly resolving these effects would require full-cycle simulations including intake port geometry and spray–wall film dynamics, which are beyond the scope of the present closed-valve CFD framework. The homogeneous mixture assumption is therefore adopted to enable a systematic and computationally efficient investigation of equivalence-ratio effects and power-matched fuel comparisons. In addition, for all dual-fuel cases, the diesel pilot injection mass was maintained constant, while the premixed methanol (or methane) mass was varied to achieve the target equivalence ratio Φ.

It is important to clarify that, because the CFD simulations start at IVC with a prescribed initial temperature, the intake-phase evaporative cooling associated with methanol vaporization prior to IVC is not explicitly resolved. Methanol is assumed to be fully evaporated and homogeneously mixed with the intake air at IVC. Consequently, the classical latent-heat-driven reduction in intake charge temperature and volumetric-efficiency enhancement are not directly captured. Instead, the influence of methanol’s thermophysical properties is reflected during the compression and combustion processes through its higher specific heat capacity, lower adiabatic flame temperature, and distributed premixed combustion behavior, which together lead to reduced peak temperatures and moderated heat-release rates.

The diesel pilot fuel start of injection (SOI) was set to 12 CAD before top dead center (BTDC) for all operating modes. The SOI was fixed at 12 CAD BTDC for all operating cases to ensure a consistent injection strategy across different fueling modes. This approach was adopted to isolate the effects of fuel properties and equivalence ratio on combustion behavior without introducing additional calibration variables. While optimizing the pilot SOI for methanol dual-fuel operation could shift combustion phasing closer to top dead center and potentially improve thermal efficiency, such optimization was beyond the scope of the present study, which focuses on comparative analysis under a fixed control strategy representative of practical marine-engine operation. In the DF cases, the diesel injection duration was 15 CAD, whereas in the pure diesel case, the injection duration was increased to 32 CAD to supply the full fuel energy. These boundary and initial conditions were kept constant across all simulation cases to ensure consistent and meaningful comparisons of combustion and emission characteristics. The boundary and initial conditions for the CFD simulation in this study are presented in Table 7.

Table 7.

Boundary and initial conditions for the CFD simulations.

2.7. Mesh Independence Analysis

Mesh independence analysis is a critical step in CFD simulations to ensure that numerical results are not affected by spatial discretization of the computational domain. Because the governing equations of mass, momentum, energy, and species transport are solved on a finite grid, insufficient mesh resolution can lead to numerical diffusion, inaccurate gradients, and artificial smoothing of key flow and combustion features. Conversely, excessive mesh refinement can substantially increase computational cost without a corresponding improvement in solution accuracy. Therefore, mesh independence analysis aims to identify a grid resolution that yields accurate and stable predictions with reasonable computational efficiency.

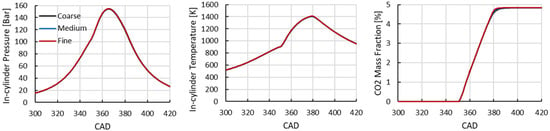

In the present study, three computational meshes with increasing spatial resolution, including coarse, medium, and fine, were employed to evaluate mesh sensitivity. To improve reproducibility, the physical base grid size associated with each mesh level is explicitly stated. The coarse, medium, and fine meshes correspond to global Cartesian base cell sizes of 1.0 mm, 0.75 mm, and 0.5 mm, respectively. Local mesh refinement was applied in regions of high gradients, including the fuel injection zone, flame front, and near-wall regions. For the medium mesh, the minimum cell size in the refined regions was approximately 0.375 mm, while the fine mesh achieved a minimum local cell size of approximately 0.25 mm. These mesh settings resulted in total cell counts of approximately 0.59 million, 0.88 million, and 1.59 million cells for the coarse, medium, and fine meshes, respectively. All meshes were simulated under identical operating conditions, and key in-cylinder parameters, including in-cylinder pressure, in-cylinder temperature, and CO2 mass fraction, were compared over the crank-angle domain, as these quantities are highly sensitive to spatial resolution and directly reflect combustion and emission characteristics.

The results show that increasing mesh resolution from the coarse to the medium grid leads to noticeable improvements in the prediction of peak pressure, temperature evolution, and combustion phasing, indicating that the coarse mesh does not fully resolve the relevant flow and reaction gradients. In contrast, further refinement from the medium to the fine mesh results in only negligible differences in pressure traces, temperature histories, and CO2 mass fraction evolution (Figure 3), demonstrating that the numerical solution has reached grid convergence and that discretization errors are sufficiently minimized beyond the medium mesh resolution.

Figure 3.

Simulation results for in-cylinder pressure, in-cylinder temperature, and CO2 mass fraction in mesh independence analysis.

From a computational standpoint, the coarse, medium, and fine meshes required approximately 24 h, 36 h, and 92 h of CPU time per simulation case, respectively. Given the minimal differences between the medium and fine mesh results and the substantially higher computational cost associated with the fine mesh, the medium mesh was selected for all subsequent simulations. This choice provides an optimal balance between numerical accuracy and computational efficiency and ensures that the predicted combustion and emission characteristics are governed by physical modeling rather than numerical artifacts, which is particularly important for CFD simulations of large-bore marine engines involving complex spray–combustion–turbulence interactions.

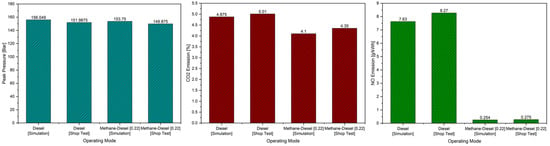

2.8. CFD Model Validation

After numerical convergence, the global energy balance was examined to confirm solution reliability. For all simulated cases, the residual energy imbalance at the end of the calculation (CAD = 478) was close to zero, indicating satisfactory energy conservation and numerical stability. The CFD framework was subsequently validated using engine shop test data provided by the manufacturer under full-load operation at 720 rpm, considering peak in-cylinder pressure, NO emissions, and CO2 emissions as validation metrics. As illustrated in Figure 4, the predicted results show good agreement with measurements. In diesel mode, the deviations between simulation and experiment were 0.22% for peak pressure, 7.7% for NO emissions, and 2.7% for CO2 emissions, while in DF mode the corresponding deviations were 4.43%, 3.4%, and 4.87%, respectively. These discrepancies are within the accepted accuracy range for three-dimensional CFD simulations of large-bore marine engines, where pressure-related quantities are typically predicted within ±5%, and emission predictions—particularly NOx and CO—within ±5–10%, due to uncertainties associated with turbulence–chemistry interaction, reduced chemical kinetics, spray modeling, and experimental measurement variability [40,41,42,43]. Similar levels of agreement have been reported in prior CFD studies of diesel and DF marine engines, supporting the robustness of the adopted modeling approach. On this basis, the validated CFD model was deemed sufficiently accurate and was applied to investigate combustion behavior and emission formation for the full set of simulated fuel cases.

Figure 4.

Comparison between simulated and measured peak cylinder pressure, CO2 emissions, and NO emissions for diesel and DF operating modes at full load and 720 rpm.

It should be noted that the present model validation is performed at a single representative operating condition (720 rpm, full load) using a limited set of global parameters, including peak in-cylinder pressure, NO emissions, and CO2 emissions. While this level of validation is sufficient to establish the reliability of the CFD framework for comparative analysis, it does not fully guarantee predictive accuracy across all operating conditions. In particular, crank-angle-resolved heat-release characteristics and detailed emission formation pathways may exhibit different sensitivities under other speeds and loads, which will be addressed in future studies.

In addition, it should be clarified that the experimental validation presented in this study covers diesel operation and methane–diesel dual-fuel operation, for which engine shop test data were available. Direct experimental validation for methanol–diesel dual-fuel operation was not possible due to the lack of corresponding methanol test data for the investigated engine. While methane and methanol differ substantially in physical and chemical properties—particularly with respect to phase state, specific heat capacity, and oxidation pathways—the validated diesel and methane cases provide confidence in the CFD framework’s ability to capture in-cylinder flow, spray–turbulence interaction, ignition initiation by diesel pilot, and global combustion behavior under dual-fuel operation.

3. Results

3.1. In-Cylinder Pressure, Rate of Heat Release, and Cylinder Power

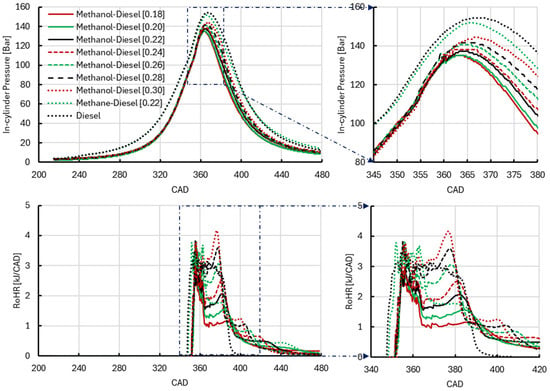

Figure 5 and Figure 6 present the in-cylinder pressure, rate of heat release (RoHR), and IMEP results for methanol–diesel DF operation over a wide range of equivalence ratios (Φ = 0.18–0.30), together with methane–diesel DF operation at Φ = 0.22 and pure diesel operation. All simulations were performed under identical engine speed and boundary conditions, enabling a direct and consistent comparison of combustion characteristics and power output across different fueling strategies.

Figure 5.

In-cylinder pressure and RoHR histories in all simulation cases.

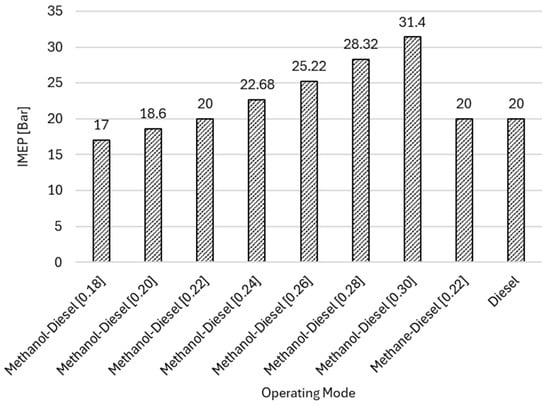

Figure 6.

IMEP of the engine for all simulation cases.

Three operating cases were designed to produce identical cylinder output, corresponding to an IMEP of approximately 20 bar: pure diesel operation (baseline), methanol–diesel DF operation at Φ = 0.22, and methane–diesel DF operation at Φ = 0.22. These power-matched conditions allow the effects of fuel properties and combustion behavior on pressure development and heat-release characteristics to be examined independently of load variation, following methodologies commonly adopted in experimental and numerical DF engine studies [44,45,46,47].

At the rated operating condition (720 rpm), the indicated power of the six-cylinder engine is 2880 kW, corresponding to an indicated work of approximately 80 kJ per cycle per cylinder. For the power-matched dual-fuel condition (Φ = 0.22), the total fuel energy input is of the same order, resulting in an indicated thermal efficiency of approximately 48%. Under this condition, methanol provides about 95% of the total fuel energy, while the diesel pilot contributes the remaining 5%.

Pure diesel operation typically exhibits the highest peak in-cylinder pressure and a sharp rate-of-heat-release peak shortly after top dead center, which is characteristic of conventional compression-ignition combustion. This behavior arises from a short ignition delay followed by an intense premixed combustion phase, leading to rapid pressure rise and highly concentrated heat release, while the subsequent diffusion-controlled combustion sustains high local temperatures within the cylinder [40,48,49,50].

Compared with pure diesel operation, methane–diesel dual-fuel operation at Φ = 0.22 produces a slightly lower peak in-cylinder pressure, while remaining significantly higher than all methanol–diesel cases. The corresponding rate-of-heat-release profile remains relatively sharp, indicating a rapid and spatially concentrated heat-release process once ignition is initiated by the diesel pilot. This behavior arises from the limited dilution of the reacting mixture and the localized nature of methane oxidation following pilot ignition, which leads to elevated local temperatures and a concentrated release of chemical energy. Similar combustion characteristics have been widely reported in experimental methane–diesel dual-fuel engines, where pilot-controlled ignition and relatively compact reaction zones result in higher peak pressures compared with alcohol-based dual-fuel operation [44,51,52].

In contrast, methanol–diesel DF operation exhibits systematically lower peak in-cylinder pressures and broader rate-of-heat-release profiles, even under power-matched conditions. Among the three IMEP-equivalent cases, methanol–diesel operation at Φ = 0.22 produces the lowest peak pressure, despite delivering the same indicated output as diesel and methane–diesel operation. Similar behavior has been consistently reported in experimental studies on methanol–diesel DF engines, where methanol substitution leads to reduced peak pressure and extended combustion duration at comparable loads [53]. This behavior is primarily attributed to methanol’s high specific heat capacity and low chemical reactivity, which reduces in-cylinder temperature at the end of compression, delays combustion development, and distributes heat release over a longer crank-angle duration [40,54].

Within the methanol–diesel DF operating range, both IMEP and peak in-cylinder pressure increase monotonically with increasing equivalence ratio. As Φ increases from 0.18 to 0.30, the greater availability of premixed methanol–air mixture leads to higher total heat release and, consequently, increased IMEP. Simultaneously, peak pressure increases due to the larger contribution of premixed combustion, although it remains lower than that observed in diesel and methane–diesel modes. Similar equivalence-ratio-dependent trends have been confirmed experimentally in methanol–diesel DF engines operating under constant-speed and variable-load conditions.

Based on the simulation results, the peak in-cylinder pressure follows the descending order: diesel operation, methane–diesel DF at Φ = 0.22, methanol–diesel DF at Φ = 0.30, 0.28, 0.26, 0.24, 0.22, 0.20, with methanol–diesel DF at Φ = 0.18 producing the lowest peak pressure. This ranking highlights the dominant influence of fuel thermo-physical properties, particularly specific heat capacity and ignition characteristics, on combustion intensity and pressure development, in agreement with prior experimental and theoretical analyses of DF combustion.

The RoHR profiles further elucidate these trends. At low methanol equivalence ratios (Φ = 0.18–0.20), combustion is primarily governed by the diesel pilot, resulting in relatively low RoHR peaks and delayed secondary heat release. As Φ increases beyond 0.22, premixed methanol combustion becomes increasingly dominant, leading to higher, but more distributed, RoHR profiles and a slight shift in the heat-release centroid toward later crank angles. Comparable RoHR broadening and delayed combustion phasing have been widely observed in experimental methanol–diesel DF engines and are attributed to extended premixed combustion and flame-propagation-dominated heat release [51,53].

The smoother heat-release behavior observed in methanol–diesel dual-fuel operation is primarily attributed to the thermophysical properties of the methanol–air mixture and the resulting combustion mode. Compared with diesel operation, the presence of a premixed methanol–air charge leads to increased thermal dilution and a more spatially distributed reaction zone during combustion. Under the present closed-cycle simulation framework, methanol evaporation is assumed to be completed prior to intake valve closing; therefore, the observed reduction in combustion intensity is not associated with intake-phase cooling. Instead, the smoother heat release arises from the combined effects of higher mixture heat capacity, lower adiabatic flame temperature, and progressive flame-propagation-dominated combustion initiated by the diesel pilot. These factors suppress the intensity of the initial premixed heat-release phase and result in broader heat-release profiles, lower pressure-rise rates, and reduced peak in-cylinder pressure, even under power-matched conditions.

In addition, the observed reduction in peak in-cylinder pressure under DF operation can be attributed to the fundamental differences in fuel preparation and combustion mode compared with conventional diesel operation. In diesel mode, fuel is injected late in the compression stroke, resulting in locally rich mixtures, intense premixed combustion, and a rapid pressure rise characteristic of diesel-cycle combustion. In contrast, in DF operation, the primary fuel (methanol or methane) is injected during the intake stroke, allowing sufficient time for mixing with the intake air during the intake and compression processes. This promotes the formation of a more homogeneous or partially homogeneous fuel–air mixture prior to ignition, and combustion is subsequently initiated by a small diesel pilot. The resulting premixed, flame-propagation-dominated combustion distributes heat release more evenly over the combustion chamber and over a longer crank-angle duration, thereby reducing the peak rate of heat release and suppressing maximum cylinder pressure. This combustion behavior can be regarded as Otto-cycle-like in terms of heat-release characteristics, although ignition remains pilot-controlled, as widely discussed in numerical and theoretical studies on DF engines [40,51,55,56].

Overall, the combined analysis of in-cylinder pressure, RoHR, and IMEP demonstrates that methanol–diesel DF operation enables power-equivalent combustion with significantly reduced peak pressure and moderated heat-release rates compared to diesel and methane–diesel operation. These characteristics are particularly advantageous for medium-speed marine engines, as they reduce mechanical and thermal loading while maintaining controllable engine output. The smoother combustion behavior also provides a favorable basis for emission reduction, which is discussed in subsequent sections.

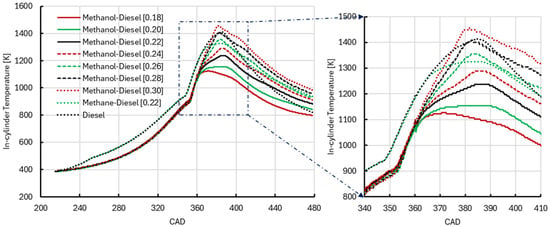

3.2. In-Cylinder Temperature

Figure 7 shows that the evolution of average in-cylinder temperature is strongly influenced by the methanol equivalence ratio in methanol–diesel DF operation. At low to moderate equivalence ratios (Φ = 0.18–0.24), methanol–diesel DF operation exhibits lower peak average in-cylinder temperatures than both pure diesel operation and methane–diesel DF operation at Φ = 0.22. This behavior is primarily attributed to methanol’s high specific heat capacity, as well as delayed and distributed heat release associated with pilot-ignited premixed combustion.

Figure 7.

In-cylinder temperature histories in all simulation cases.

However, as the methanol equivalence ratio increases beyond Φ = 0.26, the peak average in-cylinder temperature in methanol–diesel dual-fuel operation exceeds that of the methane–diesel case at Φ = 0.22. At these higher equivalence ratios, the increased fraction of premixed methanol–air mixture results in a substantially higher total chemical energy release and a broader reacting volume. Under these conditions, the effect of increased heat release and reduced dilution dominates the in-cylinder thermal behavior, leading to higher peak average temperatures. Consequently, combustion intensity increases compared with the methane–diesel case, which operates at a lower overall fuel energy input and exhibits a more diluted reaction environment.

Furthermore, when the methanol equivalence ratio approaches Φ = 0.30, the peak average in-cylinder temperature in methanol–diesel DF mode also becomes higher than that observed in pure diesel operation. This indicates that, at sufficiently high methanol substitution levels, the enhanced premixed combustion of methanol dominates the thermal behavior of the engine. The larger fraction of premixed charge contributes to higher overall energy release near TDC, leading to elevated peak temperatures even compared with conventional diesel combustion.

Despite the higher peak temperatures observed at high methanol equivalence ratios, the temperature histories in methanol–diesel DF operation remain broader and more evenly distributed over the crank-angle domain than those of diesel operation. This reflects the combined effects of premixed flame-propagation-dominated combustion and delayed heat-release phasing, which reduce local temperature gradients and limit the duration of high-temperature residence, even when peak average temperatures increase.

Overall, these results indicate that methanol–diesel DF operation exhibits a dual thermal behavior: at low to moderate equivalence ratios, charge cooling and delayed combustion lead to reduced peak temperatures, whereas at high equivalence ratios, the increased contribution of premixed methanol combustion results in higher peak average in-cylinder temperatures than those of methane–diesel and even pure diesel operation. This nuanced temperature response highlights the importance of equivalence-ratio control when optimizing methanol DF engines for both performance and emissions.

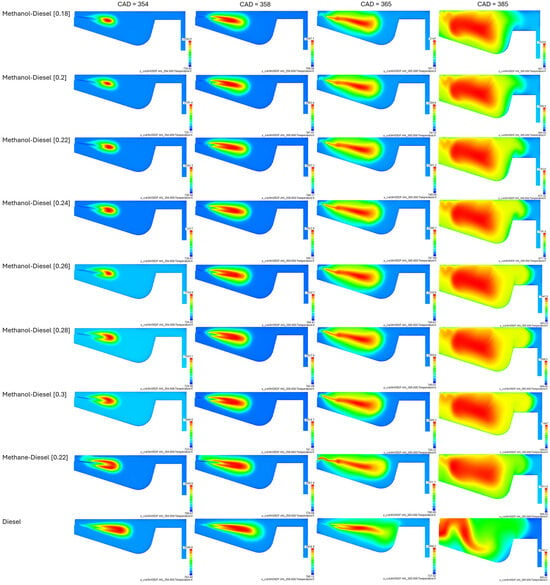

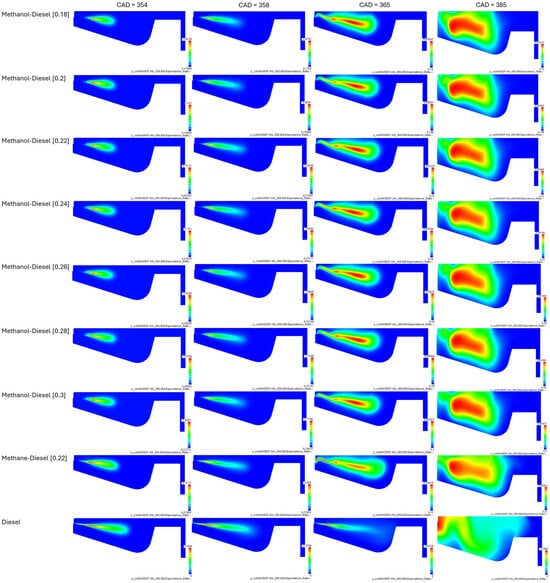

Figure 8 presents the spatial distribution of in-cylinder temperature for all simulated operating cases at four representative crank-angle positions: 6 CAD after the SOI (CAD = 354), 10 CAD after SOI (CAD = 358), 5 CAD after TDC corresponding to the peak heat-release period (CAD = 365), and 25 CAD after TDC (CAD = 385). These snapshots allow detailed visualization of ignition development, flame propagation, peak combustion intensity, and post-combustion heat diffusion under different fueling strategies.

Figure 8.

Temperature distributions inside the engine cylinder at some CAD in all simulation cases.

At CAD = 354, shortly after diesel pilot injection, high-temperature regions are localized near the injector and confined to relatively small zones, indicating the early ignition and kernel formation stage. In methanol–diesel dual-fuel operation, the peak local temperature initially increases with equivalence ratio up to Φ = 0.24. However, when Φ exceeds 0.24, the maximum temperature decreases markedly, from approximately 2317 K to around 1700 K. This behavior indicates that, at higher methanol substitution ratios, the diesel pilot ignites within a more diluted and spatially distributed premixed background, leading to reduced early-stage heat-release intensity and a less concentrated temperature rise immediately after SOI, rather than to an explicit cooling effect.

As combustion progresses toward CAD = 365, corresponding to the crank angle of maximum heat release, the influence of equivalence ratio becomes more pronounced. In methanol–diesel dual-fuel mode, the peak in-cylinder temperature increases nearly linearly with increasing Φ, rising from approximately 2147 K at Φ = 0.18 to about 2409 K at Φ = 0.30. This trend indicates that, despite weaker and more distributed early-stage ignition at higher methanol fractions, the increased availability of premixed methanol–air mixture leads to enhanced overall heat release once combustion is fully established. The methane–diesel dual-fuel case at Φ = 0.22 produces a peak temperature (~2365 K) comparable to that of the methanol–diesel case at Φ = 0.28, reflecting a more localized reaction zone and faster heat-release development following pilot-controlled ignition. Among all cases, pure diesel operation exhibits the highest local temperature, reaching approximately 2460 K, due to intense diffusion-controlled combustion and highly concentrated heat release near the diesel spray.

At later combustion stages (CAD = 385), the temperature contours clearly illustrate differences in heat distribution between combustion modes. In dual-fuel operation—both methanol–diesel and methane–diesel—the temperature field is more spatially uniform across the combustion chamber, indicating a more distributed and premixed combustion process. In contrast, pure diesel operation exhibits strong temperature gradients and localized hot spots, characteristic of diffusion flame structures and concentrated heat release. The more homogeneous temperature distribution observed in DF modes reduces peak thermal loading on combustion chamber components and contributes to lower wall heat losses and moderated combustion severity.

Overall, the temperature contour analysis demonstrates that methanol–diesel dual-fuel operation fundamentally alters combustion phasing and heat-release distribution. While higher methanol equivalence ratios suppress early-stage temperature rise due to charge cooling, they promote higher peak temperatures during the main combustion phase as premixed combustion becomes dominant. Compared with diesel operation, dual-fuel modes exhibit smoother temperature evolution and more uniform thermal fields, which are advantageous for controlling peak pressure, reducing NOx formation, and mitigating thermal stress in medium-speed marine engines.

To further elucidate the relationship between temperature evolution and mixture formation, contours of local equivalence ratio at the same crank angles (354, 358, 365, and 385 CADss) are presented in Figure 9. By comparing Figure 8 and Figure 9, it becomes evident that the high-temperature regions are closely correlated with near-stoichiometric zones formed by the interaction between the diesel pilot spray and the premixed background mixture. In methanol–diesel dual-fuel operation, the premixed methanol–air charge leads to a more homogeneous equivalence-ratio field, resulting in broader and smoother temperature distributions compared with the highly stratified temperature field observed in pure diesel operation.

Figure 9.

Contours of equivalence ratio at 354, 358, 365, and 385 CAD for all operating cases.

3.3. NO Emissions

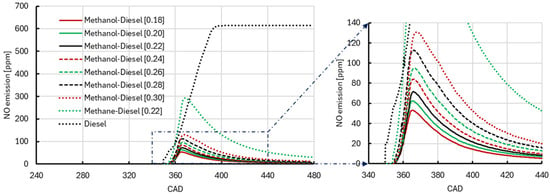

Figure 10 illustrates the crank-angle-resolved NO emission histories for all simulated operating modes. For all cases, NO formation initiates shortly after the start of combustion and increases rapidly during the main heat-release phase, followed by a gradual evolution during the expansion stroke.

Figure 10.

NO emission histories for all simulation cases.

Pure diesel operation produces by far the highest NO levels throughout the combustion and expansion processes. The NO concentration increases sharply after TDC and continues to rise during the early expansion stroke before reaching a plateau at approximately 600 ppm. This behavior is characteristic of conventional diesel combustion, where high peak temperatures, locally stoichiometric or rich reaction zones, and long high-temperature residence times promote intense thermal NO formation via the extended Zeldovich mechanism.

Methane–diesel dual-fuel operation at Φ = 0.22 exhibits significantly lower NO emissions than pure diesel operation, although NO levels remain considerably higher than those observed in methanol–diesel dual-fuel cases. The initial NO formation rate in methane–diesel operation is relatively high, reflecting elevated local temperatures during the early combustion phase associated with rapid, pilot-controlled heat release in a relatively undiluted reaction zone. However, compared with pure diesel operation, the overall NO level is reduced due to lower peak temperatures and a shorter duration of high-temperature residence, as combustion proceeds in a more partially premixed manner rather than through an intense diffusion-controlled flame. The relatively high initial NO formation rate in methane–diesel operation arises from rapid, localized heat release following pilot ignition, while the reduced overall NO level compared with diesel reflects lower peak temperatures and shorter high-temperature residence times.

In contrast, methanol–diesel DF operation results in substantially lower NO emissions across the entire equivalence-ratio range. At low methanol equivalence ratios (Φ = 0.18–0.20), NO formation is minimal, owing to strong charge cooling induced by methanol evaporation, delayed combustion phasing, and reduced peak temperatures. Under these conditions, combustion is largely governed by the diesel pilot, and the contribution of methanol to high-temperature reactions is limited.

As the methanol equivalence ratio increases from Φ = 0.22 to 0.30, peak NO emissions increase progressively. This trend correlates directly with the increase in peak average in-cylinder temperature and IMEP observed at higher equivalence ratios. Nevertheless, even at Φ = 0.30, NO emissions in methanol–diesel DF operation remain substantially lower than those of methane–diesel DF and pure diesel operation. This indicates that, although higher methanol substitution enhances total heat release and peak temperature, the combined effects of distributed premixed combustion, broader heat-release profiles, and reduced high-temperature residence time continue to suppress thermal NO formation.

Overall, the NO emission trends confirm that methanol–diesel DF operation offers a pronounced advantage in NO reduction compared with both diesel and methane–diesel operation. The strong sensitivity of NO formation to equivalence ratio further highlights the importance of optimizing methanol substitution levels to balance engine performance and emissions. These findings are consistent with the fundamental dependence of thermal NO formation on temperature magnitude and residence time and provide a strong basis for the emission benefits of methanol DF combustion in medium-speed marine engines.

Experimental studies consistently report NOx reductions for methanol–diesel dual-fuel operation compared with conventional diesel combustion, which are generally attributed to lower peak gas temperatures and reduced high-temperature residence times associated with premixed alcohol combustion [57,58]. In the present simulations, similar NOx reduction trends are observed and are primarily linked to the more distributed heat-release characteristics and moderated temperature fields of methanol–diesel dual-fuel operation. Comparisons with methane–diesel dual-fuel studies further indicate that, although methane dual-fuel combustion also reduces NOx relative to diesel, methanol–diesel operation often achieves larger NOx reductions at comparable IMEP due to the broader spatial distribution of combustion and reduced peak temperature intensity, rather than to intake-phase charge-cooling effects [44].

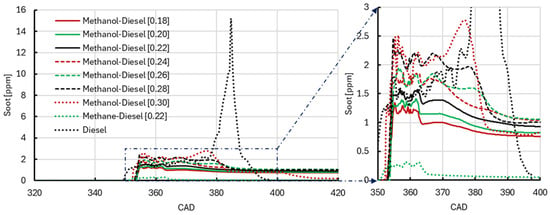

3.4. Soot Emissions

Figure 11 presents the crank-angle-resolved soot formation histories for all simulated operating modes. Pure diesel operation exhibits the highest soot formation among all cases, with a pronounced soot peak occurring shortly after TDC. This behavior is typical of conventional diesel combustion, where late direct injection leads to locally rich fuel–air regions, diffusion-controlled flames, and favorable conditions for soot precursor formation [40].

Figure 11.

Soot formation histories for all simulation cases.

Among all DF cases, methane–diesel DF operation at Φ = 0.22 produces the lowest soot levels throughout the combustion process. The near-zero soot formation observed in this mode is primarily attributed to the absence of carbon–carbon bonds in methane and the highly premixed nature of the methane–air charge, which effectively suppresses locally rich combustion zones and limits the formation of soot precursors. The small amount of diesel pilot fuel contributes only marginally to soot formation, resulting in the lowest overall soot levels among all investigated cases.

In methanol–diesel dual-fuel operation, soot formation originates almost exclusively from the diesel pilot diffusion flame, as methanol is an oxygenated fuel containing no carbon–carbon bonds and does not readily form soot precursors in premixed combustion. The observed increase in soot with increasing methanol equivalence ratio is therefore not caused by methanol combustion itself. Instead, it is primarily attributed to the progressive reduction in background oxygen concentration as the methanol–air equivalence ratio increases. Under these conditions, the diesel pilot burns in increasingly oxygen-diluted (vitiated) air, which suppresses soot oxidation in the pilot diffusion flame and leads to higher net soot levels.

At low methanol equivalence ratios (Φ = 0.18–0.20), the diesel pilot flame develops in an oxygen-rich environment, promoting effective soot oxidation and resulting in very low soot levels. As Φ increases beyond 0.22, the higher fraction of premixed methanol–air mixture reduces local oxygen availability around the diesel spray, limiting soot burnout and causing a monotonic increase in soot emissions. Nevertheless, even at the highest equivalence ratio investigated (Φ = 0.30), soot levels in methanol–diesel DF operation remain substantially lower than those of pure diesel operation, confirming the inherent soot-reduction potential of methanol substitution.

Overall, these results demonstrate that methane–diesel DF operation is the most effective strategy for soot suppression among the investigated cases, while methanol–diesel DF operation exhibits a trade-off between increased engine output and modestly increased soot formation as equivalence ratio increases. This highlights the importance of equivalence-ratio optimization in methanol DF engines to balance power output, soot emissions, and overall combustion performance.

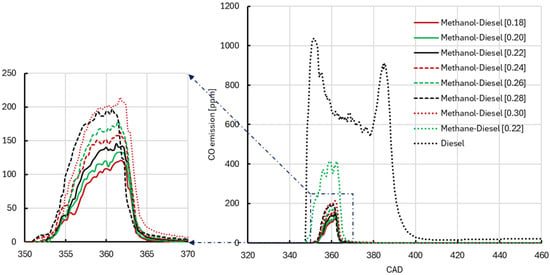

3.5. CO Emissions

Figure 12 presents the crank-angle-resolved CO emission histories for all investigated operating modes. Among all cases, pure diesel operation produces the highest CO emissions, characterized by a rapid rise in CO concentration shortly after the start of combustion and sustained high levels during the early expansion stroke. This behavior is typical of conventional diesel combustion, where locally fuel-rich regions, diffusion-controlled burning, and incomplete oxidation of carbon species promote CO formation, particularly during transient and late-combustion phases.

Figure 12.

CO emission histories for all simulation cases.

Methane–diesel DF operation at Φ = 0.22 exhibits lower CO emissions than pure diesel operation but higher CO levels than all methanol–diesel DF cases. Although methane contains no liquid-phase evaporation losses, its high resistance to auto-ignition and reliance on pilot-initiated combustion can lead to locally incomplete oxidation during early combustion, especially in regions distant from the diesel ignition sites. As a result, CO emissions in methane–diesel DF operation remain significant, albeit substantially reduced compared with diesel operation.

In contrast, methanol–diesel DF operation produces significantly lower CO emissions than diesel and methane–diesel DF operation under the investigated conditions. However, it should be noted that CO emissions alone do not fully represent combustion completeness, particularly for alcohol fuels. Methanol’s oxygenated molecular structure enhances local oxygen availability during combustion, promoting more complete oxidation of carbon species and suppressing CO formation. In addition, the premixed nature of methanol–air combustion reduces locally rich zones that typically favor CO production in diesel combustion.

Within the methanol–diesel DF cases, the results point out that CO emissions increase progressively as the methanol equivalence ratio rises from Φ = 0.18 to 0.30. Although CO emissions increase with the methanol equivalence ratio, the mixture remains globally lean even at Φ = 0.30. Therefore, the observed CO trend cannot be attributed to rich combustion. Instead, the increase in CO is primarily associated with oxidation-limited combustion under lean conditions. As the methanol equivalence ratio increases, combustion becomes more distributed and peak flame temperatures decrease due to enhanced thermal dilution and the high specific heat capacity of the methanol–air mixture. These lower temperatures suppress the conversion of CO to CO2, particularly in near-wall regions and areas affected by flame quenching. The fixed wall temperatures employed in the present simulations further promote CO survival in low-temperature boundary layers. Consequently, elevated CO emissions at higher Φ arise from incomplete CO oxidation rather than from locally rich combustion. This behavior is characteristic of lean premixed and dual-fuel combustion systems operating under temperature-limited oxidation conditions.

Overall, these results demonstrate that methanol–diesel DF operation offers a clear advantage in reducing CO emissions compared with both diesel and methane–diesel DF modes. However, the monotonic increase in CO with methanol equivalence ratio highlights the need for careful equivalence-ratio optimization to balance engine performance, combustion efficiency, and CO emissions in methanol-fueled DF marine engines.

3.6. CO2 Emissions

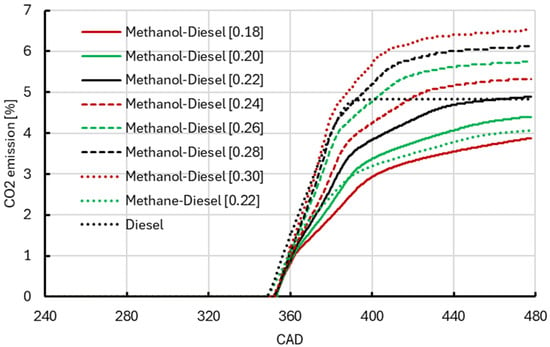

Figure 13 illustrates the crank-angle-resolved CO2 emission histories for all simulated operating modes. For all cases, CO2 formation begins shortly after the onset of combustion and increases rapidly during the main heat-release phase, followed by a gradual stabilization during the expansion stroke as oxidation reactions approach completion.

Figure 13.

CO2 emission histories for all simulation cases.

Among all investigated cases, methanol–diesel DF operation at Φ = 0.18 produces the lowest CO2 emission, reflecting the smallest total fuel energy input and the lowest carbon conversion to CO2. At this low equivalence ratio, methanol contributes a limited fraction of the total chemical energy, resulting in reduced overall carbon oxidation and consequently lower CO2 formation. As the methanol equivalence ratio increases from Φ = 0.18 to 0.30, CO2 emissions increase monotonically, consistent with the increased total fuel supply and higher IMEP observed at higher Φ values. The enhanced contribution of premixed methanol combustion at higher equivalence ratios leads to greater overall carbon oxidation and thus higher CO2 production.

The methane–diesel DF mode at Φ = 0.22 produces lower CO2 emissions than methanol–diesel DF operation at Φ = 0.20, but higher CO2 emissions than methanol–diesel DF operation at Φ = 0.18. This behavior can be explained by differences in fuel carbon content and total fuel energy input. Methane has a higher hydrogen-to-carbon ratio than diesel but still contains carbon, and the power-matched methane–diesel DF case requires sufficient fuel energy input to achieve the target IMEP, resulting in an intermediate CO2 emission level relative to the low-Φ and moderate-Φ methanol DF cases.

Notably, methanol–diesel DF operation at Φ = 0.22 produces nearly the same CO2 emission level as pure diesel operation, despite the fundamentally different combustion modes. This indicates that, under power-matched conditions, total CO2 emissions are primarily governed by the overall carbon throughput required to deliver the target engine output, rather than by combustion phasing alone. Although methanol has a lower carbon-to-hydrogen ratio than diesel, the increased fuel quantity required to compensate for its lower heating value leads to comparable total carbon oxidation and CO2 formation at Φ = 0.22.

In addition to carbon throughput, combustion efficiency also exerts a secondary influence on the measured CO2 emissions. Under different combustion modes and equivalence ratios, incomplete oxidation can result in a larger fraction of carbon being emitted as CO or remaining as unburned species rather than being fully converted to CO2. As discussed in Section 3.5, methanol dual-fuel operation at higher equivalence ratios exhibits oxidation-limited combustion behavior, leading to elevated CO levels under globally lean conditions. This incomplete conversion of CO to CO2 slightly reduces the final CO2 concentration compared with an ideal complete-combustion scenario. Nevertheless, the dominant factor governing CO2 emissions remains the total carbon content of the supplied fuel, with combustion inefficiency playing a secondary role.

Overall, the CO2 emission trends demonstrate that methanol–diesel DF operation enables flexible control of CO2 emissions through equivalence-ratio adjustment, with low-Φ operation providing significant CO2 reduction, while higher-Φ operation approaches or exceeds diesel CO2 levels as engine output increases. These results highlight the importance of operating-point optimization when using methanol as a marine fuel, particularly in balancing power demand with greenhouse-gas emission reduction objectives.

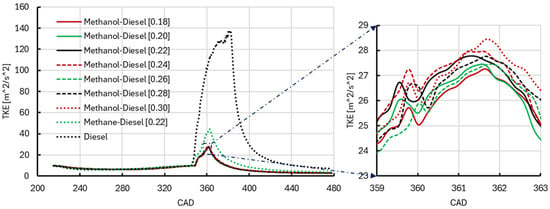

3.7. Average Turbulence Kinetic Energies

Figure 14 shows the crank-angle-resolved turbulent kinetic energy (TKE) histories for all simulated operating modes. In all cases, TKE remains relatively low during the compression stroke and rises sharply near TDC, coinciding with the onset of combustion and rapid heat release. The sharp increase in TKE reflects strong flow acceleration, jet–flow interaction, and volumetric expansion induced by combustion.

Figure 14.

TKE histories for all simulation cases.

Pure diesel operation produces the highest TKE peak among all cases. This behavior is attributed to late-cycle direct injection and the resulting high-momentum fuel jets, which generate intense shear layers and strong turbulence during the premixed and diffusion-controlled combustion phases. The rapid pressure rise and concentrated heat release further enhance velocity gradients and turbulent production, leading to the highest TKE levels.

Methane–diesel DF operation at Φ = 0.22 exhibits lower TKE than diesel operation but higher TKE than all methanol–diesel DF cases. In methane DF mode, the premixed methane–air charge reduces the contribution of diffusion flames, but turbulence generation remains significant due to relatively fast heat release initiated by the diesel pilot and the absence of strong evaporative cooling. Consequently, methane DF operation maintains appreciable combustion-induced turbulence, albeit weaker than that of diesel operation.

Methanol–diesel DF modes show systematically lower TKE levels throughout the combustion process. This reduction is primarily attributed to methanol’s high specific heat capacity, which suppresses local temperature rise and moderates combustion intensity, leading to smoother pressure development and weaker turbulence generation. In addition, the premixed nature of methanol–air combustion reduces jet-induced shear and limits the formation of highly turbulent diffusion flames.

Within the methanol–diesel DF cases, TKE increases monotonically with increasing equivalence ratio. As Φ rises from 0.18 to 0.30, the greater availability of premixed methanol–air mixture leads to higher total heat release and stronger combustion-induced expansion, which enhances velocity fluctuations and turbulent production. Nevertheless, even at the highest equivalence ratio investigated, TKE levels in methanol–diesel DF operation remain significantly lower than those observed in diesel and methane–diesel modes.

Overall, the TKE trends indicate that DF operation, particularly with methanol, promotes a less turbulent and more uniformly distributed combustion process compared with conventional diesel operation. The reduced turbulence intensity contributes to smoother heat release, lower peak pressure rise rates, and favorable emission characteristics, while the dependence of TKE on equivalence ratio highlights the role of combustion intensity in governing in-cylinder turbulence levels.

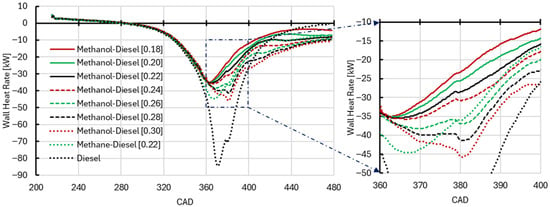

3.8. Wall Heat Loss

Figure 15 presents the crank-angle-resolved wall heat rate (WHR) histories for all simulated operating modes. In all cases, the wall heat rate remains relatively small during compression and increases sharply around TDC, coinciding with the main combustion phase. The negative sign of the wall heat rate indicates heat transfer from the hot in-cylinder gases to the combustion chamber walls, and its magnitude reflects the combined effects of gas temperature, temperature gradients near the wall, and turbulence intensity.

Figure 15.

WHR histories for all simulation cases.

Pure diesel operation exhibits the largest magnitude of wall heat rate, reaching approximately −84.3 kW, which is significantly higher than all DF cases. This behavior is attributed to the intense diffusion-controlled combustion characteristic of diesel operation, which produces high local gas temperatures, steep near-wall temperature gradients, and strong turbulence levels. The late-cycle direct injection and rapid pressure rise further enhance convective heat transfer to the cylinder walls, resulting in the highest heat losses among all operating modes.

In methanol–diesel DF operation, the magnitude of wall heat rate is substantially reduced compared with diesel operation, reflecting the smoother and more distributed combustion process. At low methanol equivalence ratios (Φ = 0.18), the peak wall heat rate magnitude is approximately −34.7 kW, which is less than half that of diesel operation. This reduction is primarily caused by methanol’s high specific heat capacity, which lowers in-cylinder gas temperatures and suppresses near-wall thermal gradients, as well as by reduced turbulence intensity associated with premixed combustion.

As the methanol equivalence ratio increases from Φ = 0.18 to 0.30, the magnitude of the wall heat-transfer rate increases monotonically, reaching approximately −45.8 kW at Φ = 0.30. This trend correlates directly with the increase in peak in-cylinder temperature, turbulent kinetic energy, and total heat release observed at higher equivalence ratios. With a larger fraction of premixed methanol–air mixture participating in combustion, the enhanced thermal energy release and elevated turbulence levels strengthen convective heat transfer to the combustion chamber walls, resulting in increased wall heat losses at higher methanol substitution ratios.

The methane–diesel DF operation at Φ = 0.22 produces a wall heat rate magnitude comparable to that of methanol–diesel DF operation at Φ = 0.30. This similarity arises from the relatively high combustion temperatures and turbulence levels in methane DF operation, which are promoted by the absence of strong evaporative cooling and the rapid heat release once ignition is initiated by the diesel pilot. Although methane DF operation avoids diffusion-controlled diesel flames, its higher gas temperatures lead to wall heat losses comparable to those of high-Φ methanol DF combustion.

Overall, the wall heat rate trends demonstrate that DF operation—particularly with methanol at low to moderate equivalence ratios—can significantly reduce heat transfer losses to the combustion chamber walls compared with conventional diesel operation. The gradual increase in wall heat rate with methanol equivalence ratio highlights the trade-off between higher engine output and increased thermal loading, emphasizing the importance of equivalence-ratio optimization for improving thermal efficiency and component durability in methanol-fueled marine engines.

4. Discussion

The present CFD investigation provides a comprehensive comparison of combustion, performance, and emission characteristics of a medium-speed marine engine operating in pure diesel, methane–diesel DF, and methanol–diesel DF modes under identical boundary conditions. Particular emphasis was placed on the influence of methanol equivalence ratio on in-cylinder thermodynamics and pollutant formation, as well as on power-matched comparisons to isolate fuel effects from load variation. Because methanol-specific experimental validation is not available, the methanol–diesel dual-fuel results should be interpreted as comparative CFD predictions rather than fully validated absolute performance metrics. In particular, phenomena strongly influenced by methanol evaporation and detailed chemical kinetics—such as ignition delay magnitude and unburned fuel formation—may be subject to higher uncertainty. Nevertheless, the consistent modeling framework applied across all cases ensures that relative trends with equivalence ratio and fuel type remain physically meaningful.

In this study, the in-cylinder pressure, RoHR, and IMEP results demonstrate that methanol–diesel DF operation enables effective control of engine output through equivalence-ratio adjustment. While pure diesel operation produces the highest peak pressure and sharpest RoHR due to intense premixed and diffusion-controlled combustion, methanol–diesel DF combustion exhibits broader heat-release profiles and reduced peak pressure, especially at low to moderate equivalence ratios. At Φ = 0.22, methanol–diesel DF operation achieves the same IMEP as pure diesel and methane–diesel DF operation but with significantly lower peak pressure, indicating a clear reduction in mechanical loading at power-matched conditions. As Φ increases beyond 0.26, enhanced premixed methanol combustion leads to higher peak temperatures and pressures; however, these remain more evenly distributed over the crank-angle domain than in diesel operation. These results demonstrate that methanol’s high specific heat capacity plays a central role in moderating premixed combustion intensity, thereby smoothing heat release and reducing mechanical loading in medium-speed marine engines.

However, it is important to note that the smoother heat-release profiles and lower peak pressures observed for methanol DF operation are influenced not only by methanol’s thermophysical and combustion properties but also by the delayed combustion phasing resulting from the fixed diesel pilot SOI. Because the pilot injection timing was not optimized for methanol, the resulting CA50 occurs later than in the diesel case, leading to reduced pressure-rise rates and peak pressure. Consequently, the present results should not be interpreted as demonstrating the optimal performance potential of methanol dual-fuel operation but rather its behavior under a non-optimized yet practically relevant injection strategy. A CA50-matched comparison through pilot SOI optimization would provide further insight into methanol’s maximum efficiency potential and is recommended for future work.

The temperature and NO emission results further highlight the benefits and trade-offs of methanol–diesel dual-fuel combustion. At low to moderate equivalence ratios, delayed and more distributed combustion development leads to reduced peak temperatures and shorter high-temperature residence times, resulting in substantial NO suppression compared with both pure diesel and methane–diesel dual-fuel operation. As the methanol equivalence ratio increases, peak temperatures rise due to the increased availability of premixed fuel and enhanced total heat release. Nevertheless, NO emissions remain significantly lower than those of diesel operation, owing to the broader spatial distribution of combustion and the reduced duration of exposure to extreme temperatures. These findings confirm that equivalence-ratio control is a key parameter for balancing performance and NO reduction in methanol dual-fuel marine engines.

The soot and CO emission characteristics reveal distinct differences between methane–diesel and methanol–diesel dual-fuel modes. Methane–diesel dual-fuel operation produces the lowest soot levels among all cases, primarily because soot formation originates from the diesel pilot diffusion flame, and methane does not directly contribute to soot precursors. Methanol–diesel dual-fuel operation exhibits slightly higher soot levels than methane–diesel operation, with soot increasing monotonically with equivalence ratio. This trend reflects the reduced oxygen availability in the vicinity of the diesel pilot as methanol substitution increases, leading to less effective soot oxidation, while overall soot levels remain substantially lower than in pure diesel operation.

CO emissions are lowest in methanol–diesel dual-fuel operation at low equivalence ratios, reflecting improved oxidation associated with distributed combustion and the oxygenated nature of methanol. However, CO increases with increasing equivalence ratio due to oxidation-limited combustion under globally lean conditions, reduced post-flame temperatures, and shortened oxidation time during the expansion stroke. Consequently, incomplete CO-to-CO2 conversion becomes more pronounced at higher methanol substitution ratios, consistent with the observed CO trends.