Abstract

Agentic artificial intelligence (AI) is emerging as a paradigm for next-generation smart grids, enabling autonomous decision-making, adaptive coordination, and resilient control in complex cyber–physical environments. Unlike traditional AI models, which are typically static predictors or offline optimizers, agentic AI systems perceive grid states, reason about goals, plan multi-step actions, and interact with operators in real time. This review presents the latest advances in agentic AI for power systems, including architectures, multi-agent control strategies, reinforcement learning frameworks, digital twin optimization, and physics-based control approaches. The synthesis is based on new literature sources to provide an aggregate of techniques that fill the gap between theoretical development and practical implementation. The main application areas studied were voltage and frequency control, power quality improvement, fault detection and self-healing, coordination of distributed energy resources, electric vehicle aggregation, demand response, and grid restoration. We examine the most effective agentic AI techniques in each domain for achieving operational goals and enhancing system reliability. A systematic evaluation is proposed based on criteria such as stability, safety, interpretability, certification readiness, and interoperability for grid codes, as well as being ready to deploy in the field. This framework is designed to help researchers and practitioners evaluate agentic AI solutions holistically and identify areas in which more research and development are needed. The analysis identifies important opportunities, such as hierarchical architectures of autonomous control, constraint-aware learning paradigms, and explainable supervisory agents, as well as challenges such as developing methodologies for formal verification, the availability of benchmark data, robustness to uncertainty, and building human operator trust. This study aims to provide a common point of reference for scholars and grid operators alike, giving detailed information on design patterns, system architectures, and potential research directions for pursuing the implementation of agentic AI in modern power systems.

1. Introduction

The global power system is experiencing a structural transition that is the result of deep decarbonization targets, rapid electrification of transport and heating, and massive integration of inverter-based renewable resources. These developments have shifted the traditional, centrally planned networks used for the transmission and distribution of electricity to highly dynamic cyber–physical “smart grids” filled with a variety of distributed energy resources (DERs), prosumers, electric vehicles (EVs), responsive loads, and edge intelligence. Conventional methods based on static models, offline studies, and fixed hierarchies struggle to handle the resulting uncertainty, non-stationarity, and scale. Consequently, there is a wide body of literature on the use of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) for forecasting, controlling, stability assessment, and cyber security for smart grids [1].

Early discussions on AI in smart grids primarily provide lists of supervised and unsupervised learning applications (e.g., load and price forecasting, state estimation, anomaly detection, and event classification) and highlight the ability of AI techniques to take advantage of high-dimensional data from advanced metering infrastructure and wide-area monitoring systems [1,2]. Recent reviews have shown how modern ML and AI methods enable grid stability analysis, frequency and voltage control, and fault detection in converter-rich systems. The literature increasingly recognizes AI in smart grids as more than predictive models; it is an intelligence layer that continuously interacts with physical assets, networks, and markets [1].

1.1. From Static Artificial Intelligence Models to Agentic Artificial Intelligence in Smart Grids

Most AI applications in power systems today are “model-in-the-loop” rather than “agent in the loop”—ML models serve offline or advisory roles (forecasting, classification), whereas conventional controllers make final decisions. In contrast, agentic AI (as used in the current review) refers to AI systems that encompass the following:

- Store internal states and goals.

- Observe the environment through streaming data and events.

- Plan multiple-step actions over time and execute those actions autonomously in the environment (for example, set the set-point, perform switching actions, and place market bids).

- Learn and adapt from feedback (possibly within a multi-agent setup).

This “agentic” perspective already appears across several research areas: deep reinforcement learning (DRL) for control decisions, Safe RL for safety-critical operations, multi-agent systems (MASs) for device cooperation, digital twin-driven optimization, and explainable AI (XAI) for interpretable operator recommendations. Recent surveys of DRL in renewable power systems and grid control have revealed the ability of DRL agents to learn policies for emergency control, voltage and frequency support, and energy management under uncertainty, thus exceeding static optimization [3,4].

Reference [5] provides an early DRL review covering voltage control, load–frequency regulation, and microgrid energy management, highlighting DRL’s ability to handle high-dimensional states and nonlinear dynamics. Reference [3] reviewed reinforcement learning and deep reinforcement learning in electric power system control from the perspective of operation states (normal, preventive, emergency, and restorative) and control levels (local device, microgrid, sub-system, and wide-area control level), which is also an effective way to define RL controllers as autonomous agents embedded everywhere in the control hierarchy. The authors [1] took this one step further with a dedicated review on safe reinforcement learning for power system control, in which it was highlighted that constraint satisfying, risk-aware exploration, and verifiable safety guarantees are needed before any reinforcement learning can be used in real grids.

Meanwhile, the MAS community has built frameworks in which autonomous agents collaborate on protection, restoration, demand response, and distributed energy management, often with local objectives and limited communication. This paper presents an extensive survey of MAS for smart grids, discussing agent coordination mechanisms, communication topologies, and applications from microgrid management to market-based resource allocation [6]. These MAS-based approaches fit neatly into agentic AI, as they are based on sets of decision-making entities that cooperate or compete in partially observable and dynamically changing environments.

Beyond control and coordination, with the emergence of digital twins and XAI, the manner in which AI agents observe and reason about the grid is changing. Reference [7] introduced the concept of an Electric Digital Twin Grid with an architecture detailing how a virtual replica of the grid would use a continuous fusion of historical and real-time data to support its capability for self-healing, predictive maintenance, and real-time decision support. Researchers in paper [8] offered a thorough overview of digital twin technology in smart grids in terms of applications such as asset management, predictive maintenance, and resilience, as well as open challenges related to their interoperability, cyber security, and model validation. In this context, the digital twin plays a two-fold role in the environment in which AI agents are both trained and tested to query actively for counterfactual simulations and what-if analyses.

Simultaneously, the explosive growth in black-box deep learning across energy systems has led to rapid interest in explainability. Researchers in this work [9] reviewed explainable AI techniques dedicated to energy and power systems, where they synthesized the modalities ideally suited to model-specific and model-agnostic explainability (e.g., feature attribution, surrogate models, counterfactual explanations) and discussed the context in which these highlights are pertinent for grid operations, forecasting, and maintenance. Explainability is fundamental for agentic AI in smart grids—autonomous agents must justify their actions to operators and regulators with policies that support oversight and post-event auditing through traceable decisions and interpretable rationales.

Recent work has found that these threads are connected with broader AI and ML, for example, big language models, foundation models, and digital twin-driven optimization, and propose ways in which AI and ML can be included throughout the entire life cycle of smart grid planning, operations, and markets. Reference [10] explored AI and ML for smart grids, with a special emphasis on digital twin and large language model-driven intelligence for the future grid, where intelligence will be learned by agents operating on rich digital replicas and communicating with operators using a natural language interface.

1.2. Limitations of Existing Surveys and Motivation for This Review

Despite the rapid growth in AI/ML smart grid research, existing surveys remain fragmented, either methodologically or by application area. Reviews that span the topic of general AI/ML in smart grids provide general taxonomies of AI methods and application areas, such as forecasting, stability analysis, fault detection, and cyber security. Nevertheless, these studies generally address RL, multi-agent systems (MASs), explainable AI (XAI), and digital twin technologies as individual subtopics instead of as part of an integrated compound agentic stack.

Survey literature devoted to reinforcement learning focuses on algorithmic characteristics, such as value-based versus policy-based techniques, model-free versus model-based distinctions, and the multi-agent RL paradigm. The related application categories are likely to include frequency control, voltage control, and energy management. However, these studies rarely place RL into a larger agentic architecture that includes, for example, the use of optimization solvers or digital twins, other agents, such as MAS frameworks or market mechanisms, or integration with human-in-the-loop decision processes.

Different surveys that deal with the subjects of MAS, digital twins, and XAI provide additional insights. The ability to coordinate protocols, agent architectures, and communication standards is usually highlighted in MAS surveys. Digital twin reviews focus on data integration, model synchronization, and cyber–physical co-simulation. A search for interpretability techniques in energy systems is available (XAI surveys), but there are rarely discussions regarding the design of explainable agents that can both enact actions and express multiple stages of plans under safety and regulatory constraints.

No existing review carries out the following:

- Offers a clear definition of “agentic AI” in the context of smart grids and maps existing techniques—RL, MAS, digital twins, XAI, and large language models (LLMs)–onto a consistent agentic architecture.

- Provides a cross-cutting taxonomy that organizes contributions according to agent capabilities (perception, memory, reasoning, planning, acting, coordinating, explaining, and self-evaluation), rather than just according to the algorithmic family or application domain.

- Conducts a critical analysis of safety, reliability, and governance requirements for the deployment of agentic AI in safety-critical grid environments, relating Safe RL, formal verification, XAI, and operator-in-the-loop design.

- Identifies open research gaps by considering the integration of recent advances, such as digital twin-based simulations, federated and distributed learning, and LLM-driven orchestration in operational grid control rooms and field devices.

Addressing these gaps is essential for moving from isolated prototypes, such as simulation-only DRL controllers, to deployable, trustworthy agentic AI ecosystems spanning transmission, distribution, microgrids, and behind-the-meter resources. Table 1 provides a capability-oriented comparison of existing AI paradigms for smart grid control where it emphasizes the gaps that motivate the need for agentic AI frameworks.

Table 1.

Capability-oriented comparison of AI paradigms for smart grid control and the resulting agentic-AI gaps.

1.3. Scope and Contributions

This review focuses on agentic AI for smart grids as an ensemble of artificial intelligence (AI) methods that provide grid-connected software and hardware entities with autonomy, adaptability, and concerted activities. Agents are considered at several levels in the hierarchy (device, microgrid, system, and market levels), and they are characterized based on the function they play, including the following:

- -

- Perception and modeling of the grid state via the flow of data and digital twin representations.

- -

- Learning and planning through reinforcement learning, deep reinforcement learning, and other forms of sequential decision-making.

- -

- Coordination through MAS frameworks, distributed optimization, and negotiation protocols

- -

- Interaction with human operators using interpretable policies and tools of XAI—compliance with safety, reliability, and regulatory constraints, including cyber security standards and grid code compliance.

The main contributions of this review are as follows:

- Conceptual Framework: We propose a formalized agentic AI framework for smart grids, which decomposes agent behavior into the layers of perception, cognition (reasoning and planning), action, coordination, and explanation, and we attempt to map existing AI techniques and architectures from the AI literature onto these layers.

- Integrated Taxonomy: We propose a taxonomy of the types of agentic AI applications in smart grids that breaks through application silos (e.g., stabilization, protection agents, flexibility aggregation agents, digital twin orchestration agent) based on conventional methodologies and organizes questions (i) based on an agent’s role in the smart grid community (e.g., protection agent, flexibility aggregation agent, digital twin orchestration agent).

- Critical Analysis of Enabling Technologies: We distill the state of the art on deep reinforcement learning, safe reinforcement learning, multi-agent reinforcement learning, digital twins, and explainable AI as they relate to agentic smart grid applications, elaborating on synergistic patterns, for example, DRL agents trained in digital twins, coordinated by MAS mechanisms, and validated using feedback from XAI.

- Deployment and Governance Solutions: We specify the practical challenges to the real-world deployment of agentic AI in smart grids in terms of data quality, simulation-to-real transfer, safety issues and robustness, human/agent interaction in control rooms, and regulatory and ethical issues.

- Research Agenda: We identify promising paths for future inquiry, such as LLM-assisted grid operations, hybrid model-based/model-free agent architectures, quantum-inspired optimization for agentic decision-making, and establishing standardized evaluation benchmarks for agentic AI in smart grids.

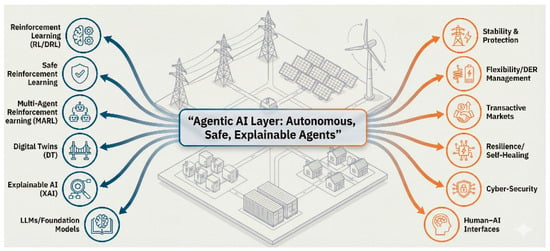

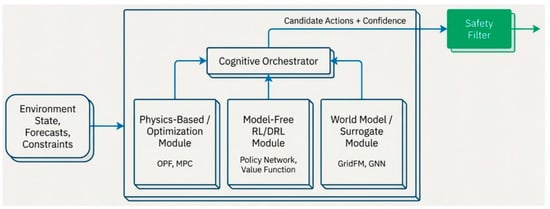

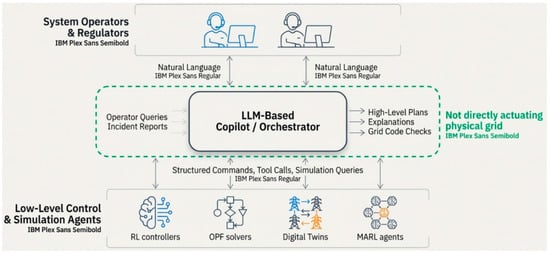

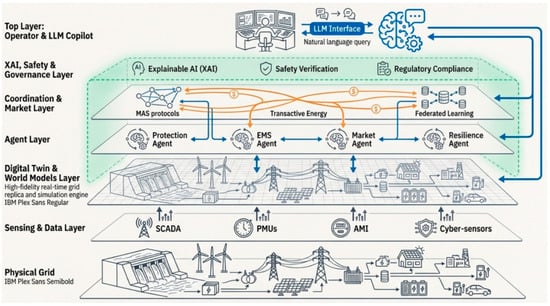

Figure 1 summarizes the proposed “agentic AI layer” that integrates reinforcement learning, digital twins, XAI, and LLMs to support critical grid functions such as protection, flexibility, markets, and cyber security.

Figure 1.

The new intelligence layer: agentic AI in smart grids.

1.4. Organization of the Paper

The remainder of this manuscript is structured as follows. Section 2 formalizes agentic AI in smart grid paradigms and lays down its conceptual foundations, such as the perception–cognition–planning–action–explanation cycle, grading the autonomy of the AI, and mapping agent roles to the temporal scales and temporal strata of control of the power system. Section 3 provides an overview of the fundamental enabling technologies underlying agentic AI for grid applications, including reinforcement learning and deep reinforcement learning, multi-agent reinforcement learning, safe reinforcement learning, digital twin-enabled learning, explainable AI, and the new role of large language models as orchestration and human interface layers based on the value of big data. Section 4 synthesizes system weakening agentic architectures and presents, in terms of application taxonomy, a functional agent archetype taxonomy organized by the different functions that different agent types perform (stability and protection, flexibility and DER/EMS, transactive markets, resilience and restoration, cyber security, and digital twin orchestration), showing the patterns in cross-layer integration. Section 5 provides an agenda of open challenges and research directions that are emphasized in benchmarking, safety-first deployment pipelines, hybrid physics-guided agents, and human–AI collaboration. Section 6 concludes by pulling together key insights and discussing limitations of the present evidence base as well as adding a practical path towards trustworthy deployable agentic ecosystems for smart grids.

2. Conceptual Foundations of Agentic AI for Smart Grids

The traditional AI literature defines an autonomous agent as a system embedded in an environment that perceives states and takes action to satisfy goals, demonstrating autonomy and persistence. Franklin and Graesser further distinguish agents from traditional programs by requiring continuous operation, situated action, self-initiated activity, and goal-directed behavior [11]. Wooldridge formalizes the idea of intelligent agents as autonomous, social, reactive, and proactive agents, which emphasize explicit reasoning about beliefs, desires, and intentions [12].

Building on these premises, a new term, “agentic AI,” is used in smart grid-related applications to refer to AI-enabled controllers that perform the following:

- Maintain an internal representation of goals, constraints, and system states, including a record of previous observations.

- Interact with the cyber–physical grid environment via sensors, communication channels, and actuators (switches, tap changers, set-points, bids, protection settings).

- Execute multi-step decision processes over extended horizons (planning, scheduling, coordination) and not just one-shot predictions.

- Adapt their policies over time based on feedback characterized by learning from feedback, simulations, or digital twin experimentation.

This definition goes beyond “using ML in power systems”; it excludes static advisory models that only produce forecasts or classifications while leaving control logic to classical controllers. Instead, agentic AI systems represent decision-making entities embedded at multiple levels of the grid hierarchy (e.g., at the level of converter, microgrid energy manager, flexibility aggregator, market bidding agent, etc.) that are endowed with the four capabilities listed above.

In reinforcement learning (RL) terms, an agentic AI system implements a policy by mapping its interaction history (observations, actions, rewards) to actions that affect the grid environment [13,14]. However, unlike the idealized Markov decision processes in canonical RL formulations, grid agents must respect hard safety constraints, operate under partial observability, and coordinate with human operators and other agents to achieve their objectives. Therefore, agentic AI in smart grids should be understood as a constrained, multi-agent, cyber–physical instantiation of the general autonomous agent paradigm [11,12].

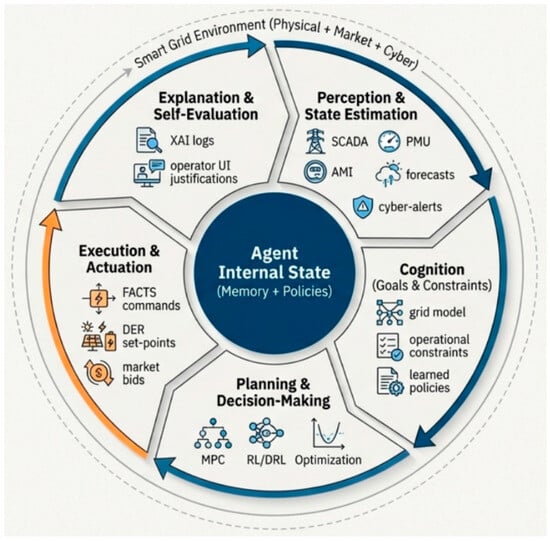

2.1. Cognitive Architecture: Perception–Cognition–Planning–Action–Explanation Loop

To reason systematically about agentic AI in smart grids, we consider the viewpoint of cognitive architecture. Cognitive architectures from artificial intelligence and cognitive science describe these sensing, memory, reasoning, and action choices, as well as their interaction, in a returning loop [11,12]. Recent work on language-based AI agents formalizes such a loop per memory module, an internal/external action space, and a decision procedure that plans, selects, and executes an action repeatedly while updating the internal state [15]. We adopt this perspective and assume that the agent in a grid works in a so-called perception–cognition–planning–action–explanation circle:

- Perception And State Estimation: The agent receives raw measurements and messages (e.g., phasor measurements, SCADA data, AMI data, forecasts, market prices, and cyber telemetry and intrusion alarms) and constitutes them into a structured internal state with state estimation, filtering, and feature extraction. This stage takes advantage of classical observers, Kalman or particle filters, or learned encoders, and has to deal with noise, latency, and missing data [15,16].

- Cognition (deliberation point of beliefs, aims, and constraints): The agent combines what it perceives to be the current state with its prior knowledge [for example, network models, device limits, contractual obligations, operational policies] and compares the current situation with its goals [ex., stability, cost, emissions, comfort, and reliability]. This reasoning may combine optimization solvers, rule-based inference, model-based reinforcement learning, or symbolic representations (safety rules, grid codes, etc.) [13,17].

- Planning and Decision-Making: Given its cognitive state, making multi-step planning decisions (selecting actions and contingencies over a horizon (e.g., schedule reserves, reconfiguring feeders, plan electric vehicle charging) considering stochastic dynamics and interactions with other agents). Methods vary from model predictive control to deep reinforcement learning and model-based reinforcement learning that combines planning and learning [6,14].

- Execution and Actuation of an Action: The agent commits to actions within its authority (e.g., issuing control commands to FACTS devices, modifying DER set-points, making market bids, and initiating remedial action schemes). In cyber–physical systems, this means strict interfacing with protection schemes, communication protocols (IEC 61850, DNP3, IEC 60870-5-104), and operator authorization layers [16,18].

- Explanation and Human Interaction: Grid agents, unlike generic AI, must explain their decisions to operators, regulators, and auditors. Explainable artificial intelligence and interpretable surrogate models are needed to transform internal policies and value functions into their human-readable equivalents of rationales, counterfactuals, and sensitivity analyses [19]. Explanatory channels are therefore a separate “output modality” of the architecture, which allows for human current or post-event metadata analysis.

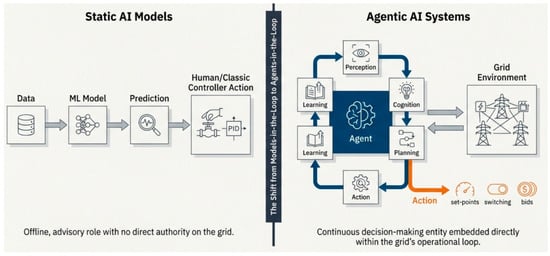

- Learning and Assessing Oneself: Feedback based on the environment (i.e., rewards, constraint violations, operator overrides, KPI violations) is used to update the inner models and policies. This can occur online (safe adaptive control) or offline using digital twin simulations [16,17]. Self-awareness includes monitoring performance, spotting distribution changes, and triggering concrete fallback modes when confidence is below a predefined percentage. As illustrated in Figure 2, we distinguish traditional static AI pipelines, where models only provide advisory outputs, from agentic systems that continuously perceive, reason, and act within the grid’s operational loop.

Figure 2. The paradigm shift: from static models to active agents.

Figure 2. The paradigm shift: from static models to active agents.

Sumers et al. demonstrated that language-based AI agent-style cognitive architectures, originally proposed for language agents, naturally extend to memory-centric, decision loop-based designs, where working memory, long-term memory, and external actions interact via a structured decision procedure [15]. By analogy, we argue that agentic grid controllers should be specified in terms of explicit modules for perception, memory, planning, action, and explanation, instead of monolithic “black-box controllers.” Figure 3 details the internal cognitive loop of a grid agent, highlighting how perception and state estimation feed cognition, planning, and execution via FACTS/DER commands, and post hoc explanation and self-evaluation.

Figure 3.

The agent’s cognitive loop.

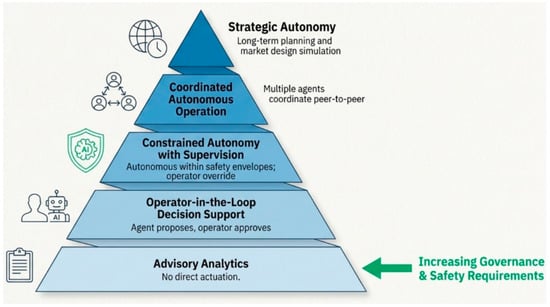

2.2. Degrees of Autonomy in the Grid Operation

In smart grids, agentic AI does not imply absolute autonomy. Instead, autonomy exists on a spectrum and emerges from agent–human interaction. Inspired by known concepts of autonomous agents [11,20] and autonomy taxonomies in control and robotics [16], we define the following levels of autonomy for grid agents in the following hierarchical order:

- Level 0—Advisory analytics: AI provides predictions, classifications, or prescriptive advice (load forecasts, contingency rankings, anomaly detection), but human operators or traditional controllers retain all control authority. This level is consistent with the current implementation of machine learning in power systems. In our framework, the AI does not act in an agentic manner because it does not have any direct authority to make things happen.

- Level 1—Operator in the loop decision support: For the provision of such an AI agent, explicit control actions or policy proposals are generated (such as remedial action schemes, reconfiguration plans, and optimal set-points). Operators then review, alter, and accept or reject these proposals. The agent executes an internal cycle of policy and planning but has no direct capacity for autonomous actuation; this arrangement is equivalent to “shared control” paradigms in robotics.

- Level 2—Constrained autonomy with supervision: The agent works autonomously bounded within predefined safety envelopes (e.g., voltage and reactive power control bounds, balance of local microgrid, and electric vehicle charging coordination), while recording explanatory data and allowing overrides by an operator. Techniques such as safe reinforcement learning, formal verification, and runtime monitoring are important for ensuring that learned policies comply with grid regulations and protection constraints [6,16].

- Level 3—Coordinate Autonomous operation: Multiple agents make stand-alone decisions and communicate with each other (e.g., distributed voltage/VAR control, peer-to-peer microgrid balancing, and autonomous restoration schemes) relying on human supervision, which is primarily involved in policies and governance. Multi-agent system frameworks and distributed optimization techniques are the dominant organizational paradigms [17,21].

- Level 4—Strategic autonomy overseen by humans: Agentic AI systems are engaged in strategic system planning, long-term asset management, and market design through simulations, scenario analysis, and digital twin experiments. These systems produce possible solutions that are later evaluated and approved by humans [18,22]. In this context, autonomy means not so much activating real-time but rather independent exploration of the policy and configuration space against institutional constraints.

These stratifications provide a conceptual framework to categorize deployments in existence and those planned in the future: most deep reinforcement learning-based protection and control prototypes are working at Level 1–2 (in simulation or hard-wired hardware-in-the-loop), while MAS-based microgrid coordination and autonomous restoration activities aim at Level 3 [17,21]. The main contribution of the current review is to scrutinize how agentic AI technologies, namely deep reinforcement learning, safe reinforcement learning, multi-agent systems, digital twins, and explainable AI, could help safely move to higher levels of autonomy without losing reliability. To organize the deployment spectrum, Figure 4 provides a structured view of increasing autonomy levels, ranging from advisory analytics to fully coordinated autonomous operations.

Figure 4.

A spectrum of autonomy for grid operations.

2.3. Time Scales and Control Layers of Agentic AI

Power systems exhibit multiscale multilayered control systems. Classical hierarchical control for microgrids and more general power systems separates loops of inner (ms) level converters, primary/secondary (m control) level, frequency, voltage control (ten ms to classic seconds), from tertiary and economic dispatch (min to hour) [16,23] and long-term (planning) (day to years) control. We provide a schematic mapping of agentic AI capabilities on these temporal strata:

- Fast dynamics (sub-cycle to seconds): Inner converter control loops, FACTS devices, and protection mechanisms require deterministic and short response times. Accordingly, agentic AI is usually combined with parameterized policies distilled from offline deep reinforcement learning or optimization with live adaptation, which is severely limited by hard real-time constraints [16]. Examples include the DRL-trained damping controller or adaptive relay setting that remains static while humans are in service and will only be updated post-validation.

- Operational control (seconds–tens of minutes): Secondary and voltage/VAR optimization, congestion management, and microgrid balancing occur on much longer time scales and are better suited for agentic intervention of artificial intelligence. Hierarchical control studies seem to indicate that optimization- and multi-agent-based secondary/tertiary controllers are increasingly proposed to coordinate the use of distributed energy resources and storage [16,23]. Agentic AI in this layer is capable of continuous replanning, reallocation of reserves, and corrective switching, and it enforces constraints very rigidly.

- Market scheduling horizons (tens of minutes to days): Unit commitment, economic dispatch, scheduling of demand response, and aggregation of flexibility take place over time scales that are relevant to the markets being adjusted (say 5–60 min). MAS-based aggregators and reinforcement learning-driven bidding agents democratize within these intervals to maximize economic and reliability goals in the face of uncertain generation and demand from renewable sources [17,21,24]. Digital twin simulations are essential for evaluating the long-term performance and strategy of a digital twin [18].

- Planning and investment time scales (months to decades): The uses of grid expansion, asset health management, and climate resilience planning occur over a long timeframe. Here, agentic AI is used for simulation-based exploration and testing of scenarios, as opposed to real-time control. Agent-based models and multi-agent systems are usefully employed to investigate emergence in multi-energy systems and market–ecosystem interactions [19,20].

Figure 5 aligns candidate agent roles with inherent power system time scales, distinguishing fast protection, operational EMS, congestion, market bidding, and long-term planning agents.

Figure 5.

Aligning agentic control with power system time scales.

Yamashita et al. and Li et al. have demonstrated how hierarchical control schemes in microgrids are explicit in their decomposition of tasks in terms of time scale and authority, which provides a natural framework for embedding agentic modules of AI [22,25]. Reference [26] further argues that multi-energy system planning and operation increasingly embrace a hierarchical and distributed control structure, where local agents optimize sub-system behaviors with respect to system-level constraints.

This view of time and hierarchy is key to the deployment of agentic AI:

- It describes where learning and adaptation can be safely introduced, usually in slower layers with augmented human supervision and simulation to back them up.

- It clarifies the interfaces between traditional controllers of set-points or policies and AI agents, where the outputs of AI (policies or set-points) are executed by lower-level deterministic controllers.

- It forms the basis for a principled mapping between agent roles (e.g., protection, microgrid dispatch, and market bidding agents) and time scale responsibilities (protection, primary/secondary control, EMS, markets) and associated accountability.

2.4. Organizational Scope and Multi-Agent Ecosystems

Smart grids are multi-stakeholder and distributed systems by their nature. Prosumers, DSOs/TSOs, aggregators, microgrid operators, market operators, regulators, and service providers interact under heterogeneous objectives and constraints. Multi-agent systems (MASs) provide a natural framework for the modeling and implementation of such ecosystems [17,21].

Recent surveys synthesize over a decade of MAS research in the smart grid area. Mahela et al. investigated architectures for MAS-based control of smart grids and highlighted the coordination protocol, communication topology, and application domains of protection, restoration, demand response, and market-based resource allocation [19]. Izmirlioglu et al. provided an up-to-date survey of MASs for smart grids by reporting the diversity of agent types (e.g., DER agent, prosumer agent, market agent, and grid operator agent), communication patterns, and decision-making mechanisms employed in practice [6].

Complementary studies have focused on application-specific MAS designs.

- Olorunfemi et al. proposed a MAS framework for demand response management, where household, aggregator, and grid agents coordinate via negotiation protocols to balance cost, comfort, and grid constraints [18].

- Yao et al. reviewed agent-based methods in multi-energy systems (electricity, heat, gas), showing how decentralized agents representing physical assets and actors can capture complex interdependencies and facilitate local and global optimization [19].

These studies converge on several organizational patterns relevant to agentic AI in smart grids:

- Role-based agent decomposition: Agents include protection, voltage control, market bidding, microgrid energy managers, flexibility aggregation, and digital twin orchestration agents. Each role corresponds to specific observables, actuators, time scales, and performance metrics, which align naturally with the conceptual framework in Section 2.2 and the autonomy levels in Section 2.3.

- Multi-agent human and artificial intelligence systems: Labedzki argues that future multi-agent ecosystems will be hybrid, containing both human and artificial agents with complementary strengths [21]. In power systems, this is already the case: human operators and dispatchers operate as agents with high-level authority, with automated controllers performing tasks with local, fast time scales. Agentic AI is a solution to this hybrid MAS, with additional cognitive agents that can explain the decisions made, negotiate with humans and other agents, and learn over time.

- Digital twin-mediated—ecosystems: Shan et al. continue with their point: Multi-actor energy system operation increasingly relies on digital twins that enable what-if evaluation and policy validation prior to deployment [22]. In such ecosystems, digital twins act as agents: they respond to queries, execute what-if scenarios, and provide feedback (in the form of KPIs and constraint violation statistics) on the policies of the agents performing the right action.

- Governance and norm design and protocol design: The MAS literature emphasizes that agent behavior must be controlled in terms of interaction protocols, norms, and rules [institutional] [6,17,21]. In the context of a smart grid, this translates to grid codes, rules for the markets, data sharing agreements, and cyber security policies that limit the degree of agentic AI that can be used and how it is allowed to interact. Designing governance layers for agentic AI, such as specifying authorization boundaries, escalation paths, audit mechanisms, and liability frameworks, is therefore as important as designing the learning algorithms themselves.

In summary, the organizational scope of agentic AI spans local device controllers to system-level orchestrators and market participants, all embedded within hybrid human–AI MAS structured by digital twins and institutional constraints. Section 3 of this review will map specific enabling technologies—DRL, Safe RL, MARL, digital twins, XAI, and LLM-based orchestration—onto this conceptual landscape.

3. Core Technologies Underpinning Agentic AI in Smart Grids

3.1. Reinforcement Learning and Deep Reinforcement Learning for Grid Control

Reinforcement learning (RL), the canonical technique for sequential decision-making under uncertainty, naturally serves as the backbone of agentic AI in smart grids. An RL agent interacts with an environment that is modeled as a Markov decision process (MDP) and learns policy mapping states (or histories) to actions to maximize the expected cumulative reward. Classical RL algorithms, such as value-based algorithms (Q-learning), policy gradients, and architectures such as actor-critic, are standard in control and optimization [27,28].

In the power and energy sectors, RL has evolved from a niche topic to a mainstream approach. Cao et al. provided a comprehensive review of RL and DRL applications in power flow control, voltage and frequency regulation, economic dispatch, unit commitment, energy storage scheduling, demand response, fault detection, and load forecasting. Bernadić et al. focused specifically on RL for power system control and optimization, highlighting concrete implementations of RL-based tap changer control and techno-economic optimization of storage in microgrids [29]. Waghmare et al. systematically reviewed RL-based control strategies for microgrid energy management and documented their advantages over classical heuristics for handling uncertainties and high-dimensional state spaces [30]. Li et al. synthesized DRL applications in renewable-rich power systems and showed that DRL can learn emergency control and small-signal stabilizing policies that outperform static optimization under fast-changing operating conditions [31].

From an agentic-AI standpoint, these developments imply the following:

- Policy-based learning modules based on RL/DRL can be deployed as the “decision core” of local agents (e.g., inverter controllers, microgrid energy managers, and storage schedulers) that continuously map perceived states to actions.

- Actor-critic and value-based DRL architectures that have already been used for continuous control (i.e., DDPG, PPO, SAC) can be embedded as inner cognitive components in agent architectures with surrounding layers enforcing safety, explanation, and coordination.

- The literature is now filled with a sufficient number of case studies in favor of pattern language as RL for real-time control of fast dynamics (voltage, frequency, damping) and DRL for higher-dimensional operational problems (EMS, congestion management, multiperiod scheduling).

However, most RL/DRL deployments remain confined to simulations or hardware-in-the-loop testbeds, with little attention paid to long-term stability, grid code compliance, and explainability under real disturbances, which are critical requirements for safety-critical deployment.

3.2. Multi-Agential Reinforcement Layout of Grid Coordination

Many of the multiple tasks associated with a smart grid are multi-agent by nature: between different stakeholders (TSO/DSO, aggregators, microgrids, prosumers, protection devices) who operate with limited information and at best, conflicting goals. Multi-agent reinforcement learning (MARL) adapts RL to these environments through an improved approach of projecting the environment as an opaque game with numerous learning agents. Recent MARL surveys have described important paradigms such as independent learning, centralized training with decentralized execution (CTDE), and joint action learners, and have related MARL to game theory and distributed optimization. Several strands have developed in the area of power:

Foundational MARL frameworks for power systems: Biagioni et al. proposed PowerGrid world, a modular MARL testbed for power system operation, allowing for the realistic operation of power system dynamics and multiple agents with interactions in the context of grid constraints. Jain et al. applied MARL in power system operation and control, where decentralized agents can coordinate to handle frequency, voltage, and congestion, and analyze the stability properties [32].

MARL for resource allocation and EMS MARL is used in the context of distributed energy management, which allows various generators, storage, and prosumer agents to coordinate to meet power balance requirements, minimize costs, and adhere to network constraints.

General MARL challenges relevant to grids in recent surveys focusing on key obstacles, non-stationarity, credit assignment, scalability, and partial observability are mentioned, all of which are acutely present in large-scale power systems.

From the agentic-AI perspective, MARL can offer the following:

- A formal agent design and analysis framework for ecosystems of agents, including protection, efficiency control, and flexibility aggregation agents, with each agent being trained to maximize local goals and provide system-level performance.

- The natural path to Level 3 autonomy (coordinated autonomous operation) as a concept is stipulated in anti-isolated anti-pathological forms in Section 2 where the agents act together or compete according to specific protocols and the same rewards instead of acting independently.

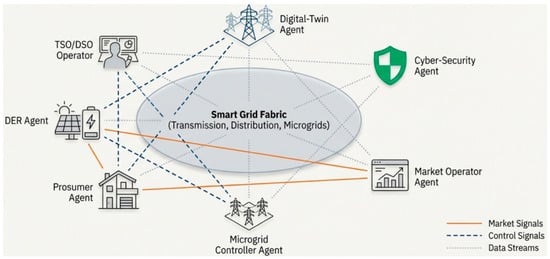

However, when it comes to power systems, the present MARL literature does not pay much attention to the combination of digital twins, safety verification, and explanation; these cross-cutting requirements are exactly what the agentic AI infrastructure aims to structure. Figure 6 depicts the smart grid as a multi-agent ecosystem, where prosumer, DER, microgrid, market, cyber security, and digital twin agents interact over market signals, control signals, and data streams.

Figure 6.

The smart grid as a multi-agent ecosystem.

3.3. Safe Reinforcement Learning and Constrained Decision-Making

A fundamental obstacle to RL-based agentic controllers is safety. Standard RL relies on trial-and-error exploration, which is unacceptable for power grids, where constraint violations cause blackouts or equipment damage. Safe reinforcement learning (Safe RL) is an approach that attempts to apply safety constraints to learning and action, commonly through constrained MDPs, Lyapunov-style tactics, shielding, or risk-sensitive objectives.

Bui et al. give a critical review of Safe RL strategies for the case of power system control specifically, where strategies like safety layers that project actions back into a feasible region, Lyapunov-based critics that ensure stability, and model-based Safe RL schemes that add system theory constraints to the learning process are cataloged. They explained that although it is possible to impose restrictions on frequency, voltage, and power flows with ease in simulation by Safe RL, there are few measures that are robust under the uncertainty in the model, as well as in models that are disturbed by cyber–physical factors [28].

General RL reviews for power and energy systems also discuss the fact that it requires RL to be clearly interfaced with conventional protection and control, fallback rules, guard rails, and runtime monitoring to ensure safe deployment. Recent research on explainability in DRL only reinforces the point that safety and interpretability go hand in hand; operators must receive not only guarantees of constraint satisfaction but also understandable rationales for an agent to take a certain action in an abnormal situation.

From an agentic perspective, Safe RL offers a safety-aware decision core for agents operating at Level 2–3 autonomy. The key design patterns include the following:

- Combining DRL and control theorem safety filters (e.g., control barrier functions) that override unsafe actions.

- Stress testing policies under different contingencies spending on digital twins (Section 3.4) to pre-train the strategies.

- Human-in-the-loop portfolios embedding the Safe RL agents with human-in-the-loop protocols defining operator overrides as negative feedback and adjustments to refine policies.

3.4. Digital Twin-Enabled Learning and Control

Digital twins (DTs) are sensitive full-fidelity digital models of physical systems or objects that are synchronized with real-time data and permit simulation, diagnostics, and optimization within a risk-safe context. In the power sector, DTs have been proposed for transmission networks, distribution systems, substations, and microgrids for predictive maintenance, outage management, and resilience analysis. In the case of agentic AI, the DTs do not simply represent passive models; they are examples of training environments as well as partners in crime.

Hua et al. proposed a digital twin-based RL framework in which the DT of a distribution system operator’s network is adopted to train RL agent(s) for configuration and operation decisions, claiming improvements in predictability, responsiveness, and automation compared to static policies [33].

Tubeuf et al. demonstrated transfer learning on a flexible energy system DT: RL agents are trained on synthetic or historical data of a DT; however, they are transferred and fine-tuned in the actual system, thus enabling the mitigation of unsafe exploring processes in a real grid [34].

Seyedi et al. created a DT-enabled RL controller for DC microgrids by exploiting the DT to explain sim-to-real annoyances and test policies under uncommon fault and disturbance conditions [35].

In general, in addition to particular applications of power models, a more recent systemic review of RL-based DT frameworks bears out common meta-designs: environment modeling through physics-based models or data-driven models, collaboration with RL loops (state encoding, reward-shaping, domain randomization), and mechanisms of online synchronization between the DT and physical system.

DTs can perform at least three functions in an agentic AI stack:

- Simulation sandbox: Agents learn and stress-test their policies using DTs before deployment, and Safe RL constraints and rare-event scenarios are explored here.

- Real-time counterpart: DTs run in parallel to physical systems, providing counterfactual analyses, sensitivity studies, and predicted consequences of candidate actions that agents can query during the planning phase.

- Cross-agent Coordination Medium: DTs can host multi-agent simulations in which protection agents, flexibility aggregators, and market agents interact, enabling the discovery and validation of higher-level coordination rules.

3.5. Explanability and Interpretability of Agentic Control Loops

Agentic artificial intelligence used as part of smart grid systems must be auditable and accountable. Operators, regulators, and manufacturers need to understand the rationale behind an agent’s chosen action, the variables on which this decision was based, and the confidence the agent has expressed. These requirements are part of the field of explainable artificial intelligence (XAI) or interpretable modeling.

Machlev and colleagues report among one of the first comprehensive method reviews of XAI techniques used in energy and power systems by introducing, in a systematic way, feature-attribution methods (such as SHAP and LIME), methods of surrogate modeling, and counterfactual explanations that have been used in forecasting applications, fault detections, and operational support [9]. Shadi et al. assessed XAI techniques for energy system maintenance, which makes post hoc explanations useful in supporting predictive maintenance and condition monitoring in Internet of Things-enabled energy frameworks [36]. Sazib et al. suggested a domain-specific XAI potential with respect to renewable energy systems and argued for the use of standardized benchmarks and performance indicators to provide the ability to compare explanations and calculate their impact on operator confidence [37].

With respect to deep reinforcement learning (DRL), Hickling et al. provided an extensive overview of the landscape of methods for explainability, which includes methods for extracting symbolic policies, saliency mapping, attention-based visualization, and methods for causal analysis to interpret traditionally opaque DRL policies [38]. Taghian et al. extrapolated this discussion to industrial control and safety-critical settings, which demand the explainability and certifiability of DRL policies [39].

In the context of agentic AI deployment in smart grids, XAI must go beyond model introspection and encompass the following:

- -

- Rationalization of a particular action, such as the shedding of a particular load, switching of a particular transmission line, and adjustment of a particular tap position of a transformer, relative to alternatives.

- -

- The identification of the most influential signals, including voltage levels, loading indices, contingency probabilities, and cyber security alerts, aided in the decision-making process.

- -

- The expected behavior of the policy under counterfactual scenarios; for example, we might like to see how the policy would have reacted if the output from a wind farm had been 20% lower.

Such explanations should be integrated into the agent’s control loop via a separate explanatory module that manifests human-readable rationales, synthesizes post-event reports, and enables root-cause analysis. As a result, XAI forms a central facilitator of Level 1 and Level 2 autonomy, with the inclusion of approval and supervision by the operators involved.

3.6. Large Language Models and Foundation Models as Orchestrators

The more recent direction of artificial intelligence research has proposed the presence of large language models (LLM) and other foundation models that exhibit strong performance in the domains of textual reasoning, code generation, and coordinating tools. Within the scope of power systems, such models appear increasingly not as direct low-level controllers but as high-level orchestraters and interfaces in agentic architectures.

Majumder et al. analyzed the readiness of LLMs to act as an interface between human stakeholders and the electric energy sector, which defines possibilities for knowledge retrieval, policy interpretation, incident reporting, and operator training, while also highlighting limitations such as hallucinations, domain mismatch, and data governance limitations. A recent survey on the application of LLMs to smart grids seeks applications in questions of grid information in natural language, automatically generating standard operating procedures, and linking heterogeneous AI providers with tool-calling systems [40].

Concurrently, Yao et al. surveyed “AI large models for power systems,” underlining that foundation models such as LLMs and large time series models can exist as meta-models with the ability to adapt to a range of tasks such as forecasting, anomaly detection, and decision support with limited task-specific data [41]. Xiang et al. presented an LLM-based monitoring system that aims to mitigate the functioning of the system, with the concept that an LLM accepts a dispatch description, processes real-time information about the power flow within the system, and provides an objective safety score, thereby connecting textual operating instructions and the state of the system in a numerical form [42]. In addition, a growing body of literature shows both externally invoking simulators and optimization-based agents that use LLM-based agents to assist in grid planning and operational decision-making.

Within a stack of agentic AI algorithms, LLMs and foundation models may serve several functions.

- -

- Cognitive front-end: A natural language interface that converts operator intents, regulatory directives, and incident reporting into lower-level objectives (goals and constraints) for lower-level reinforcement learning (RL) or model predictive control (MPC).

- -

- Planning and Orchestration Layer: A high-level agent that breaks down tasks, chooses specialized models (e.g., DRL controllers, optimal power flow solvers, and digital twin simulations), and assembles the outputs of these models into recommendations.

- -

- Knowledge and Governance Hub: A permanent collection of incidents, policies, and lessons learned, which can produce explanations, check whether policies and grid codes are obeyed, and assist post-event investigations.

However, foundation models bring concomitant risks, such as opaque training data, formal verification challenges, vulnerability to adversarial prompts, and problems in meeting the high demands of latency and determinism necessary for their application in real-time control. These limitations suggest that, in the short term, LLMs can be enabled as decision-aiding and planning agents with defensive guardrails and not as direct control agents of physical actuators.

3.7. Synthesis

Taken together, RL/DRL, MARL, Safe RL, digital twins, XAI, and foundation models constitute the core technological pillars of agentic AI in smart grids.

- -

- RL/DRL provides adaptive decision policies for individual agents.

- -

- MARL enables coordinated behavior among distributed controllers and stakeholders.

- -

- Safe RL and XAI provide the necessary safety and transparency layers for deployment in critical infrastructure.

- -

- Digital twins offer a sandbox and counterpart for training, validation, and what-if analyses.

- -

- LLMs and large models act as high-level orchestrators and human-facing interfaces, respectively.

Therefore, the next section will examine system-level architectures that combine these ingredients into coherent agentic AI stacks, showing how layers of perception, cognition, planning, action, coordination, and explanation can be instantiated in concrete smart grid applications (stability, protection, flexibility aggregation, and market participation) while satisfying safety and governance requirements. Table 2 summarizes the main agent archetypes discussed in this subsection, linking each role to its objectives, actuators, characteristic time scales, and dominant enabling technologies.

Table 2.

Representative agent archetypes in smart grids, with objectives, time scales, and dominant enabling technologies.

4. Agentic AI Architectures and Application Taxonomy in Smart Grids

Agentic artificial intelligence in the context of smart grids is a fundamental system-level design decision rather than the application of another component of an algorithmic system. Autonomous agents are deployed at different geographical locations and time scales, have specific roles, and are interlinked by communication networks, market mechanisms, and digital twin infrastructures. The present section formalizes such a holistic system understanding, and provides a taxonomy of agent roles and applications, which will be able to transcend conventional disciplinary limitations, such as forecasting, stability, or market clearing.

In contrast to algorithm-centric or application-centric survey frameworks, which are mostly group research based on model class or tasks domain, the proposed capability-driven taxonomy groups previous work based on functional capabilities (autonomy level, safety enforcement, decision authority, human-in-the-loop requirements, etc.). This organizational scheme provides greater analytical clarity by explicitly suggesting the links between the relationships among technical mechanisms and system-level roles and operational responsibilities. From additional evaluation perspectives, a taxonomy makes it simpler for design and deployment from direct reasoning about interoperability, certification readiness, and operator oversight, engineering choices that surpass isolated functionality.

4.1. Layered Agentic Architecture Smart Grid

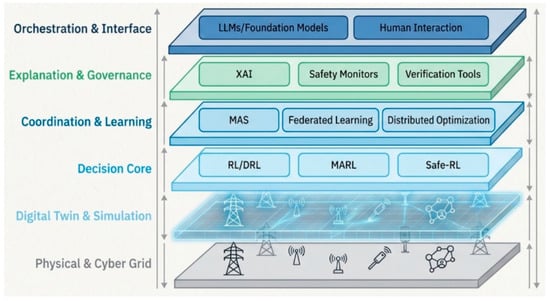

Building on the aspects of the perception–cognition–action–coordination–explanation cascade that we have already introduced, a concrete layered architecture for agentic smart grids may be summarized as follows:

- -

- Perception and Data Layer—Streaming measurements from supervisory control and data acquisition (SCADA)/energy management systems (EMSs), phasor measurement units (PMUs), smart meters, distributed energy resource (DER) controllers, meteorological feeds, and cyber security sensors.

- -

- Cognitive Layer—Decision and reasoning modules, including optimal power flow (OPF) and model predictive control (MPC) solvers, deep reinforcement learning (DRL) and Safe RL for constrained control, Bayesian/Kalman filtering for uncertainty handling, and foundation models (LLMs/time series models) for forecasting and decision support.

- -

- Action Layer—Controllers and actuators for implementing switching, set-point dispatch, flexible AC transmission system (FACTS)/DER control, and market bid submission.

- -

- Coordination Layer—Multi-agent coordination (MAS), transactive energy mechanisms, federated learning, and hierarchical control that put a lot of local agents into a single whole.

- -

- Explanation and Governance Layer—Explainable artificial intelligence (XAI) pipelines, safety monitors, formal verification elements, and human–agent interfaces (large language model-based natural language front-ends).

To consolidate these relationships, Table 3 illustrates the facilitation of artificial intelligence technologies by elaborating their functional responsibility inside agentic smart grid systems, rather than understanding their relative significance. Primary functional roles define the fundamental capabilities provided by each technology; secondary contributions summarize the support roles or supporting capabilities; and deployment relevance is the standard stage or context of deployment in which the technology is deployed. Such a functional decomposition overcomes the issue of subjective ranking while making a direct link between each technology and design and deployment considerations at the system level [7,32,37,38,43].

Table 3.

Functional roles of enabling AI technologies in agentic smart grid systems.

Classical MAS surveys have already revealed that smart grid control architectures tend to form naturally occurring centralized, decentralized, hierarchical, holonic, or coalition-based architectures, such that the categorization is directly compatible with agentic AI layering when cognitive and XAI modules are embedded within each agent rather than considered as an external black-box optimizer [6,17]. A practical implication of this research is that a number of classes of existing MAS controllers can be extended into agentic AI-based operating systems, under certain explicit assumptions regarding observability, autonomy, and safety. This transition requires the integration of learning-based decision-making paradigms such as DRL and MARL in conjunction with the use of digital twin technologies for safe training and strict validation. Moreover, the inclusion of mechanisms to explain these systems is essential to allow human operator oversight and accountability in these advanced systems [44,45,46].

Most existing deep reinforcement learning-based grid controllers are validated in almost exclusively simulation or hardware-in-the-loop setups, where often safety, constraint satisfaction, and operator interaction are implicitly hidden topics. Recent investigations show that to move beyond this stage, it is necessary to have architectures that explicitly incorporate safety constraints, supervision at the system level, and operational feasibility. Safe DRL-based autonomous scheduling frameworks have proven that the integration of operational constraints and validation mechanisms is essential for real-world energy system deployment, in contrast to the optimization of performance in a simulated context [47]. Complementary survey and system-level analyses further indicate that deployable autonomous control systems must include monitoring, decision arbitration, and safety enforcement levels to achieve higher technology readiness levels [48]. Collectively, these results provide evidence for the argument that agentic architectures of AI—which integrate learning, safety, and oversight into one control structure—can open an important tangible route from closing gaps between simulation-based controllers for DRL to deployable smart grids.

4.2. Agent Roles and Archetypes in Smart Grids

Instead of organizing the literature under algorithmic headings (RL, MPC, heuristic) or asset classes (FACTS, EV, storage), we propose the notion of agent archetypes that explicitly call for encoding the functional role of each entity on the power system grid.

Agents for Stability and Protection: Voltage and frequency support agents manage the coordination of inverter droop mechanisms, secondary and tertiary support actions, and grid-forming operations. Protection agents identify faults, interact for the proceeding of tripping and reclosing operations, and control adaptive protection settings in distribution and transmission networks. Multi-agent system (MAS)-based protection frameworks have already shown agents performing local fault detection, islanding, and reconfiguration activities, reducing fault clearance times and improving selectivity [44,49].

Flexibility and DER Management Agents: Microgrid energy management system (EMS) agents ensure the synchronization of photovoltaic (PV), wind power, storage, and controllable load resources. Electric vehicle (EV) aggregator agents schedule large fleets of EVs for vehicle-to-grid (V2G) and grid-to-vehicle (G2V) interactions in accordance with network constraints [8,9]. Building energy management agents are responsible for managing heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC) systems, thermal storage, and flexible end-use appliances at the edge [6,50].

Transactive Market and Pricing Agents: Local market agents implement transactive energy systems (TESs), in which bids and offers, as well as local price information, coordinate distributed energy resources (DERs) and loads [51]. Hierarchical transactive microgrid agents optimize energy cost and carbon footprint through multi-level multi-agent reinforcement learning (MARL) [52]. Distribution system transactive energy market system (TEMS) agents are responsible for clearing local markets by considering voltage constraints and the high penetration of renewables and EVs [53,54].

Resilience and self-healing agents: Restoration agents reconfigure distribution feeders and microgrids after faults and use MAS coordination to restore computing load and mitigate voltage/security goals [49,55]. Islanding and reconnecting agents negotiate microgrid boundaries, black start sequences, and sequence of service across multiple microgrids.

Cyber–physical Security and Situational Awareness Agents: Intrusion-detection agents combine anomaly detection, rule-based warnings, and graph-based reasoning. Situational awareness agents combine supervisory control and data acquisition (SCADA), phasor measurement units (PMUs), EMS, operational technology (OT) logs, and external intelligence for summarizing risk indicators for operators [6,44].

Digital twin Orchestration and Simulation Agents: Agents are in touch with the agent that adds the digital twin (DT) layer, induces what-if situations, validates policies in synthetic environments, and performs procedural simulation-to-real transfer in RL policies. Such agents act as meta-controllers, coaching subordinate agents, controlling DT model fidelity, and selecting relevant scenarios [44,56].

Human-sponsored/logistics manager (LLM)-Enabled Orchestration Agents: Large language model (LLM)-based agents act as natural language front-ends to grid information, operating procedures, and AI instruments, which allow operators to ask the operating system status, obtain an explanation, or script complex operations in natural language [57,58,59].

4.3. Taxonomy of Functional Application

Applications are now organized according to system functions instead of algorithms, and with explicit references to the agent roles and main technologies (deep reinforcement learning [DRL], MAS, DT, explainable AI [XAI], and LLMs) usually used.

- Voltage, Frequency, and Power Quality Management: Agentic applications include distributed voltage control, where agents representing inverters, on-load tap changers (OLT Cs), and capacitor banks cooperate through consensus or negotiation-based voltage control mechanisms to maintain voltages within prescribed limits while minimizing losses [60,61]. Frequency and inertia management in microgrids are performed by MAS-based secondary and tertiary controllers with all set-points shared by cooperative control, which reduces the dependence on centralized automatic generation control (AGC) [62]. Power quality agents adaptively tune harmonic filters, harmonic compensators in the filter or converter, and control loops by potentially exploiting DRL policies trained in DTs and monitored by the XAI module. Such systems are inherently hierarchical agent systems, where fast local agents implement the droop and converter-level control (millisecond-second level) and slower supervisory agents are used for the coordination of tap changer operations and set-point adjustments (seconds-minute range) [60,62].

- Microgrid and Distributed Energy Resource Management: For grid connected and islanded microgrid(s), MAS-based EMS solutions are based on agents assigned to these distributed generators, storage units, controllable loads, and tie-lines, where these agents negotiate power set-point and schedule under the economic and reliability objectives [63,64]. Concerning RL agents, renewable-rich microgrids increasingly include RL agents that learn policies to control the dispatching of storage and to operate load shifting [44,65] but are still physically embedded in MAS frameworks for negotiation and conflict resolution. Buildings surrendered their loads (HVAC, EV charging activities, etc.) to building-level agents, while participating in community markets and demand response programs, indicating that MAS studies realized improved comfort–cost trade-offs and resilience to communication failures [6,66]. In agentic terms, these are performed by each EMS agent, keeping internal goals (cost, emissions, comfort), sensing local measurements and price signals, and planning and executing schedules by coordinating with peers and agents up higher in the market organization (top).

- Transactive Energy Market-Based Coordination: Transactive energy systems explicitly include economic agents that orchestrate supply and demand through price determination and bidding behavior, often at the distribution or microgrid levels [11]. In addition to multi-agent TEMS, key agentic patterns include prosumer and aggregator agents bidding into local markets, while system operator agents enforce constraints on the networks and reliability [53]. Hierarchical transactive microgrids use a three-layer architecture of the MARL model, where household agents optimize costs, intermediate agents contribute to adjusting prices, and top-level agents focus on inter-microgrid trades and inter-microgrid carbon footprints [52]. Market clearing agents for regional distribution markets involve multi-agent coordination for double auctions to handle congestion, fairness, and carbon pricing [54,67]. From an agentic AI perspective, TES is a blatant example of coordination-heavy roles: all agents deploy a strategy to maximize their individual utility, but they must conform to network limitations and regulatory laws. DRL approach-based bidding policies, DT, and market simulators are increasingly used to increase robustness and trustfulness, along with XAI tools for price transparency.

- Resilience/Self-healing/Restoration: MAS architectures have been used profusely in applications such as self-healing distribution grids and multi-microgrid restoration, where agents that represent switches, feeders, and microgrids collectively make isolation, reconfiguration, and load prioritization decisions [49,55]. Agentic AI is used to refine these architectures by training restoration policies (single-/multi-agent RL) in high-fidelity DTs that simulate faults, extreme weather, and cascading failures, thus lowering the need for rule-based heuristic training methods for safe layers. Safe layers ensure the fulfillment of constraints, such as thermal constraints, voltage profiles, and N-1 safety requirements. Ultimately, formal verification in the case of N-1XAI is meaningfully used to justify restoration decisions (e.g., why specific feeders would not be energized, why critical loads are prioritized). This is imperative for regulatory compliance and public acceptance. Recent efforts have shown that multi-aging restoration schemes significantly reduce outage duration and unserved energy compared to static restoration strategies, particularly if the control of DERs and microgrids is active instead of being considered a passive resources [49,55].

4.4. Cross-Layer Design Patterns and Integrated Stacks

Several recurring patterns emerge in the literature when integrating RL, MAS, DTs, and XAI into end-to-end stacks.

- DT-Centric Training and Shadow Deployment

- ▪

- RL and MARL policies for voltage control, microgrid EMS, or transactive markets are first trained and stress-tested in DTs, and then deployed cautiously to real systems with “shadow mode” evaluation [44,68].

- ▪

- DT orchestration agents manage scenario generation (e.g., extreme weather and contingencies), data fidelity, and synchronization with live systems.

- Hierarchical MAS with RL-Enabled Local Agents

- ▪

- Lower-level agents (e.g., DER controllers and local markets) use RL for local decision-making, whereas upper-level agents enforce global objectives and constraints via coordination algorithms or market mechanisms [52,60,62].

- Human-in-the-Loop XAI and LLM Interfaces

- ▪

- Operational agents expose explanation interfaces (e.g., feature importance plots, counterfactual explanations, and natural language rationales) that LLM-based assistants can summarize or contextualize for operators and regulators [3,41].

- Federated and Distributed Learning for Privacy and Scalability

- ▪

- The multi-agent setting is often combined with federated learning to update models across many devices or microgrids without centralizing data, thus aligning with privacy and regulatory constraints while still benefiting from collective learning [6,46,65].

These patterns are the building blocks of truly agentic AI ecosystems for smart grids; the remainder of this paper focuses on safety, governance, and open problems in scaling them. A consolidated view of this technology stack is presented in Figure 7, highlighting the interactions between the physical infrastructure, digital twins, and learning-based decision cores, coordination layers, and governance frameworks.

Figure 7.

The engine room: inside the agentic technology stack.

5. Research Agenda and Open Challenges for Agentic AI in Smart Grids

As shown above, agentic AI in smart grids has evolved from speculation to active research, as evidenced by advances in DRL controllers, multi-agent architectures, digital twins, XAI, and LLMs. Nonetheless, the available literature consists mostly of a mixture of promising experimental prototypes rather than a fully developed engineering discipline. Accordingly, this section lays out a coherent research agenda that has the following form: benchmarking and evaluation, safety-first architecture, hybrid model-based/model-free agents, LLM orchestrated operations, and socio-technical and environmental considerations.

5.1. Towards Standardized Benchmarks for Agentic Grid Control

Current publications typically evaluate RL or agentic controllers on custom testbeds with custom metrics, making cross-paper comparisons impractical and difficult. Recently, initiatives such as RL2Grid have been proposed to provide a common benchmark for RL-based plan grid operations and combine optimal power flow (OPF), managing contingency, and tasks related to stability [69]. RL2Grid provides various operational scenarios and conditions; however, it remains largely single-agent-based and focused on transmission-level operations. Complementary efforts, such as MARL2Grid, extend this framework to multi-agent scenarios, explicitly addressing distributed control and local observability constraints in meshed networks. What is still lacking is a benchmark suite that matches overtly to the “agentic stack” addressing, herein, perception, memory, planning, acting, coordination, and explanation. Accordingly, new benchmarks for future use should consist of the following:

- -

- Incorporate end-to-end tasks that require agents to develop a combination of forecasting, state estimation, and control, rather than assuming perfect information and forecasts.

- -

- Span heterogeneous time scales, from millisecond number protective actions down to one hour, and different networks, from high voltage transmission to overall distribution and microgrids to behind-meter resources.

- -

- Safety-critical scenarios are defined as first-class evaluation cases (N-1/N-k, extreme weather, IBR-dominated islands, communication loss), not just average-case steady states.

Methodological studies on the systematization of RL for power system control, such as that by Jin et al. [70] and the last surveys focused on Safe RL for grid applications [71,72], establish a good conceptual ground that must be transposed into publicly available, well-documented, and continuously maintained benchmark suites adopted by both academia and industry.

Recent research has empirically built a framework for demonstrating safe deep reinforcement learning by formally modeling the problem of autonomous scheduling within integrated energy systems with deep learning and by explicitly incorporating operational constraints and system-level objectives into the learning paradigm. Specifically, safety-aware DRL frameworks have highlighted an increased feasibility to be deployed in the real world by simultaneously considering the constraint satisfaction, scheduling performance, and operational robustness, as opposed to focusing solely on simulation-based validation [43,47].

Representative applications of safe reinforcement learning-based autonomous scheduling provide empirical evidence to show that deployable intelligent control systems always require the explicit consideration of safety constraints and operational limits. Recent investigations show that the inclusion of such constraints into the learning and decision-making processes themselves is inseparably linked to the bias from simulated to real-world energy system operations for autonomous controllers [47]. Supplementary system horoscope analyses further propose that the feasibility associated with deployment is dependent upon the integration of learning-based controllers with supervisory structures that permit supervision monitoring, constraint enforcement, and compliance with operational requirements [43]. These findings hence offer direct impetus towards agentic architectures for AI, for which learning, safety, and system oversight are conceptualized as integrated functionalities at the system level, rather than disjointed algorithmic components.

A concrete short-term objective is the definition of “Grid Agentic Benchmark v1.0”, which consists of the following:

- -

- Builds on RL2Grid and MARL2Grid scenarios;

- -

- Includes explicit roles (e.g., protection agent, flexibility aggregator access digital twin orchestration agent);

- -

- Measures not only reward and constraint violation, but also explainability, robustness, and simulation to real transfer measures.

5.2. Safety-First Architectures and Verification Pipelines

Given the critical importance of power systems, safety considerations must be incorporated into the system from the earliest stages of design and not as an afterthought. Current Safe RL surveys aggregate an overview of shielding, constrained policy optimization, and Lyapos for applications to the grid [71,72]; nevertheless, there is currently no consensus architecture that combines these methods in a transparent and certifiable pipeline.

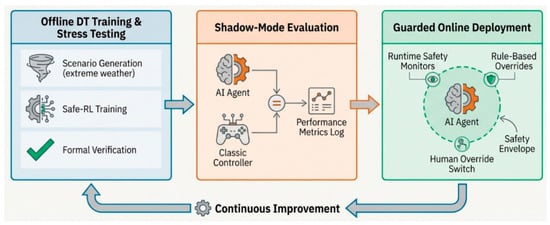

An important research direction is to connect Safe RL design patterns with formal verification and digital twin-based testing. The double-helix model for the verification and validation (V&V) of physical and digital twins explicitly emphasizes the bidirectional coupling between the real system and its twin and provides a general systems engineering view of how TEVV (testing, evaluation, verification, and validation) should be organized [73]. Applying this paradigm to agentic AI entails the following pipeline, each of which has a number of layers:

- -

- Offline layer: Agents are trained and stressed in high-fidelity digital twins, which are scenario ensembles (extreme weather, cyber–physical faults, rare operating points). Formal tools are available for checking the reachability of unsafe states in the presence of bounded disturbances.

- -

- Shadow mode layer: Policies are run in “advisor” or “shadow” mode in the control room (or embedded protection devices), where they generate actions but do not take any grid action. Their behavior is logged, monitored, and compared to operator or legacy controller decisions.

- -

- Guarded Online layer: Based on the measured performance, the agents run under runtime monitors and rule-based safety envelopes that can override the action in which they achieve hard limits or violate security rules (e.g., voltage/frequency margins, line currents, protection settings).

Figure 8 illustrates a safety-first deployment pipeline, beginning with offline digital twin training and stress testing, progressing to shadow mode evaluation against classic controllers, and culminating in guarded online deployment with runtime safety monitors and human override.

Figure 8.

The path to deployment: a safety-first pipeline.