Abstract

This paper deals with the issue concerning the optimization of energy consumption saving in passenger railway traffic. The background is mainly related to the decision to modernize existing trains or purchase new units, which is a key dilemma for rail transport managers. Concerning the methods used for the determination of the proper results, there is a very wide range of possibilities. This issue is complex, encompassing technical, economic, environmental, and social aspects; therefore, artificial intelligence methods were used for analysis. The obtained results have shown that the choice is not clear-cut, as each option offers both benefits and limitations. The investigations are based on real measurement values obtained from a Polish regional railway. In conclusion, it can be found that the final decision should take into account the long-term goals and the specific characteristics of the given rail system. Several factors influencing the energy consumption were taken into account. So, the aim of this paper was achieved, and the main factors were determined, which have influenced energy consumption and its impact, as well as the possibility of energy consumption reduction.

1. Introduction

The energy consumption of railway vehicles is receiving growing attention. Among the different factors, some can be determined, like train route, train type (modernized or new), energy consumption (MWh), train kilometers/operating work (KM), transport performance (thousand gross KM), travel hours (e.g., late evening, rush hour, morning), or train length [1,2,3].

The impact of train routes on energy consumption in Poland is a multifaceted issue, encompassing both technical and organizational factors that shape the energy efficiency of rail transport. The route profile—its terrain, gradient, number of curves, surface type, and supporting infrastructure (Table 1)—has a direct impact on traction energy consumption [4]. Trains traveling on routes with significant elevation differences and numerous uphill and downhill gradients consume more energy than those traveling on flat terrain [5]. Furthermore, frequent stops at stations, speed changes, and the need to brake and accelerate again increase electricity demand [6,7,8].

Table 1.

Average energy consumption of rail vehicles [6].

Simulation studies conducted on selected routes in Poland in Greater Poland Voivodeship have shown that differences in energy consumption can be significant, even between sections of similar length, if they differ in terrain profile and the number of stops. Programs such as RSEL and RSDL enable accurate modeling of train movement, taking into account the resistance forces, vehicle weight, infrastructure parameters, and driving dynamics [9,10,11]. These programs enable route optimization in terms of energy consumption, which is crucial in the context of rising energy costs and the pursuit of sustainable transport development [12,13].

In Poland, where the rail network encompasses both modern high-speed lines and older, less modernized sections, differences in energy consumption are particularly pronounced [4]. Modernizing rolling stock [14,15] and infrastructure, including the electrification of lines, improving track quality, and implementing modern traffic control systems, can significantly reduce the energy consumption of transport [16]. However, as experts point out, increasing travel comfort and speed often comes at the cost of higher energy consumption, requiring a compromise between efficiency and service quality.

In the context of energy and climate policy, optimizing rail routes is becoming not only a technical issue but also a strategic issue. Electric trains consume an average of 2.5 to 3.5 kWh per 100 km, making them more efficient than cars or airplanes. However, their efficiency depends on driving conditions and the organization of transport. Therefore, route planning, taking into account the terrain profile, number of stops, capacity, and type of rolling stock, is crucial for minimizing energy consumption and reducing CO2 emissions. In the future, technological advancements and intelligent traffic management systems could further increase the energy efficiency of railways in Poland [17,18,19].

The impact of a train type—whether it is a modernized unit or a completely new one—on energy consumption is a significant issue in the context of sustainable rail transport. New trains are designed with maximum energy efficiency in mind, utilizing the latest technologies in propulsion, aerodynamics, construction materials, and energy management systems. This allows them to consume less energy per unit, translating into lower operating costs and a smaller carbon footprint [20]. For example, modern multiple units are often equipped with energy recovery systems, which allow for the recovery of some energy during braking and reuse of it, significantly reducing the overall energy consumption [21].

Conversely, modernized trains, although often cheaper to purchase and quicker to implement, have limited potential for improving energy efficiency. Modernization can include replacing engines, installing new control systems, or improving thermal insulation, but it does not always allow for the full potential of modern technologies. Furthermore, older trains can be less aerodynamic [22], heavier, and less energy-efficient, meaning that even after modernization, their energy efficiency remains lower than that of new units.

It is also worth considering the operational aspect—new trains often require less maintenance, which indirectly impacts energy consumption throughout the vehicle’s lifecycle. On the other hand, modernization can be beneficial from a circular economy perspective, as it allows for extending the life of existing assets and reducing material consumption. In practice, the choice between modernization and purchasing new units depends on many factors: budget, environmental objectives, technology availability, and planned operational life. However, from a purely energy-based perspective, new trains typically offer significantly improved energy consumption, making them more attractive in a long-term railway development strategy. The above economic aspects support the use of new rolling stock; however, due to the small amount of empirical data, it is difficult to verify this aspect in reality [7,23,24,25].

Optimizing electricity consumption in rail transport, expressed mainly in megawatt-hours (MWh), is a key element of the transport sector’s sustainable development and energy efficiency strategy. Faced with rising energy costs and environmental pressures, rail operators are implementing a range of technical and organizational solutions aimed at reducing traction energy consumption. One of the most important areas is the use of intelligent rail traffic management systems, which enable smooth train speed control, minimizing losses resulting from sudden braking and acceleration. Analyzing operational data and forecasting the network load allows for dynamic adjustments to operating parameters to the current conditions, resulting in lower energy consumption [26,27,28].

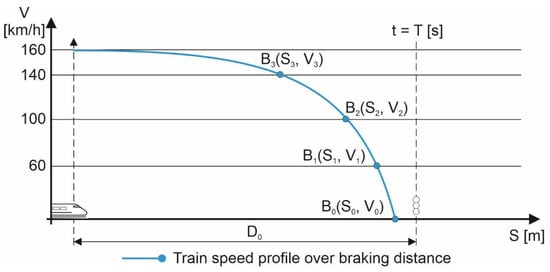

The goal of energy consumption optimization is to determine a train speed profile that uses as little kinetic energy as possible while approaching a given signal, and to avoid having to stop and wait [29]. Optimization therefore involves determining a train speed profile (Figure 1), such that a train traveling from point A reaches point B in time T, at a specified speed, V, and distance, S. The evaluation criterion is the mechanical energy consumption needed to maintain the train’s maximum speed and make up the lost distance, compared to a scenario in which the train travels without any speed restrictions, as the so-called reference train [26].

Figure 1.

Points on the braking curve (source: own work, based on [26]).

Another important aspect is energy recuperation, or the recovery of electrical energy during train braking [30]. Modern rail vehicles are equipped with systems that allow for the transfer of recovered energy back to the traction network catenary or its storage, enabling significant energy savings. Modern energy management systems in trains, based on advanced algorithms and sensors, monitor consumption in real time, identifying areas of potential losses and enabling their elimination. However, energy consumption optimization is not limited to technology alone. Organizational measures also play a significant role, such as planning timetables with energy-efficient routes in mind, training drivers in eco-driving, and integrating IT systems that support operational decisions. Furthermore, multi-criteria optimization of rail traffic—taking into account not only travel time but also energy consumption, operating costs, and environmental impact—allows for significant savings without the need to invest in new infrastructure. In the context of European and national climate policies, optimizing energy consumption per MWh in rail transport is becoming not only an economic necessity but also a moral obligation to future generations. Due to the synergy of technology, data, and informed management, rail can become a model for energy efficiency in public transport [31,32].

Rail transport operational work, measured in train-kilometers, is one of the key parameters for analyzing the efficiency of the railway system. A train-kilometer is defined as the distance traveled by one train over one kilometer, which allows for a precise determination of the intensity of rail infrastructure utilization. The technical and economic literature, including the journal “Railway Problems,” published by the Railway Institute, treats operational work as a fundamental parameter in assessing transport efficiency, timetable planning, and the allocation of traction resources. Scientific articles indicate that changes in the value of train-kilometers are directly linked to infrastructure modernization, route optimization, and the implementation of rail traffic management systems. Research published on the Science Library platform emphasizes that an increase in the value of operational work may indicate better utilization of modernized railway lines, which translates into increased capacity and shorter travel times. At the same time, operational data published by the Polish National Safety Authority—Office of Rail Transport (Urząd Transportu Kolejowego) show that the annual variability of train kilometers is a significant indicator of the economic situation in the freight and passenger transport sector. In the context of European regulations, such as Regulation (EC) No. 91/2003 of the European Parliament and of the Council, train-kilometers are also used in rail transport statistics as a comparative measure between Member States [33,34,35].

From a strategic planning perspective, operational performance analysis enables the identification of areas requiring investment intervention, the optimization of transport schedules, and the assessment of the impact of transport policy on the actual use of the rail network. Modern mathematical and simulation models used in technical and economic studies allow for the forecasting of train-kilometers, depending on scenarios for infrastructure development, demographic changes, and climate policy. Thus, operational performance becomes not only an operational indicator but also a strategic tool in railway system management [36,37].

Another important factor is the journey time. The time of a train’s journey—whether early morning, rush hour, or late evening—has a significant impact on the energy, operational, and organizational efficiency of rail transport. The technical literature and analyses published by PKP Polskie Linie Kolejowe S.A. (national infrastructure manager) and the Railway Institute indicate that the time of day affects not only the infrastructure load but also the traction energy consumption, traffic dynamics, and passenger comfort. During rush hours, when passenger flows are at their highest, trains run more frequently, which increases the operational efficiency, expressed in train-kilometers. However, it can also lead to higher energy consumption due to more frequent stops, acceleration, and the need to maintain high punctuality. On the other hand, late-evening journeys are characterized by a lower network load, allowing for smoother train operation and potentially lower energy consumption. However, a lower passenger load can impact the economic efficiency of such journeys. Studies published in “Biblioteka Nauki” (Science Library), for example, indicate that limiting the starting dynamics and operating at a fixed speed—possible during off-peak hours—helps to reduce electricity consumption, although it can extend travel times. Early mornings, especially in the context of regional transport and commuting, are a time of intense rolling stock use, but at lower temperatures, they can generate additional energy consumption related to heating the trains [38,39,40].

Managing timetables based on the time of day is therefore becoming a key element of optimization—both in terms of energy and operational efficiency. Rail infrastructure development strategies increasingly incorporate travel time analysis as a factor influencing the efficiency of the entire system. Integrating operational data with traffic management systems allows for dynamic adjustments to driving parameters to the current conditions, resulting in more sustainable resource utilization [41,42,43].

Due to the profound changes taking place among rail carriers in the former Central and Eastern European block, as well as in the rail infrastructure itself, it is worth answering the following questions. Should we renovate old rolling stock or replace it entirely with new stock? Which solution is more sensible and more future-proof? However, the key considerations in making this decision should not be financial, but primarily passenger safety and comfort.

Of course, the natural way to restore the aged EN57 electric multiple units (Figure 2) is to thoroughly overhaul them (inspection at level P5 or P4). Why are we primarily talking about the EN57? The answer, if we look at the production history of this unit, is simple. The EN57 is a standard-gauge, three-section electric multiple unit, manufactured at the Pafawag plant (Polish: Państwowa Fabryka Wagonów, ang.: State Wagon Factory) in Wrocław between 1962 and 1993, in over 1429 units. It is the longest-produced rail vehicle in the world [44,45].

Figure 2.

EN57-612 operating with Polregio, a passenger train at the Tarnowskie Góry station (Silesian Voivodeship, Poland), manufactured in 1965 [photo by Jarosław Konieczny, 2022].

The EN 57 modernizations completed to date are very advanced (Figure 3). An example is the one completed at the H. Cegielski Rail Vehicle Factory (Polish: FPS—Fabryka Pojazdów Szynowych) in Poznań. FPS assures that after the “very thorough modernization,” the vehicles are characterized by the following parameters [46]:

Figure 3.

EN57AKŚ-730: a passenger train at Tarnowskie Góry station, Katowice-Lubliniec route, produced in 1968 by Pafawag Wrocław [photo by Jarosław Konieczny, 2022].

- Operating speed of up to 120 km/h.

- Improved driving capabilities, due to the use of the following:

- New asynchronous motors.

- New two-stage gearboxes.

- Modernization of the bogies in terms of the first stage of suspension and wheelset guidance, along with ensuring optimal braking parameters.

In addition, the modernized EN57 units feature a modified front end, a new interior (Figure 4), a rebuilt driver’s cab, a separate air conditioning system for the passenger compartment and the driver’s cab, a closed-system toilet and an additional one adapted for disabled persons, a sliding door, an integrated passenger information system, and other features resulting from the need to adapt such a vehicle to the current standards expected by carriers and passengers, such as monitoring, facilities for mothers with children, and power outlets at the seats. Importantly, they are usually equipped with wheelchair-accessible platforms.

Figure 4.

Interior of EN57AKŚ-730 [photo by Jarosław Konieczny, 2022].

Of course, from a general point of view, it would be interesting to explore—when buying new vehicles—which type would be the most proper. Increasing demand for alternatives to fossil fuels in rail, especially on non-electrified lines (around 38% in Poland), creating, for example, an opening for hydrogen. The future key pint can also focus on issues such as whether low-temperature polymer electrolyte membrane fuel cells (PEMFC) are suitable for transport, or their potential for greater energy efficiency and reduced toxic emissions compared to diesel [47,48].

2. Research Procedure

To determine the discussed parameters in this paper, artificial intelligence tools were used for calculations. The parameters used for calculations are presented in Table 2. The data included the train type; the year of production; the producer or manufacturer; the year of last renovation, P4 or P5; or the contractor of the last renovation of P4 or P5.

For calculation, the Statistica Neural Networks 4.0 F software was used. Under the agreement concluded between the Silesian University of Technology and StatSoft Polska Sp. z o.o., it is possible to obtain STATISTICA software in the academic year 2025/2026 under the Site License for employees, student laboratories, and students of the following units of the Silesian University of Technology.

Both of the oldest units are also equipped with air conditioning. The EN71AKŚ consists of four cars (sections) and is designed to carry 256 passengers in individual seats, plus 260 standing passengers. The EN57AKŚ, on the other hand, consists of two end-carriage units for steering and a middle drive unit, and is designed to carry 168 passengers in individual seats, plus 195 standing passengers. For comparison, the latest generation of 22WEd—“ELF 2” electric multiple unit, manufactured in 2019—is also equipped with a special “parking” system, ETCS control equipment, and GSM-R communication, and can carry a maximum of 190 seated and 150 standing passengers.

Currently (July 2025), the cost of acquiring a new EMU, based on the example of purchasing 26 31WEbc units under the “Purchase of zero-emission rolling stock” project by the Silesian Voivodeship, amounts to PLN 36.9 million (EUR 8.7 million) [63]. The cost of P4 overhaul for 5 EMU EN57AKŚ vehicles in 2023 amounted to PLN 11,641,950.00 gross, i.e., the overhaul of one EN57AKŚ unit amounted to PLN 2,328,390 gross (EUR 547,856) [64,65].

3. Investigation Results and Discussion

There are many reasons why the age of rolling stock increases energy consumption. The most common reason is that older rail vehicles often have less efficient motors and drive systems, leading to higher energy consumption. Furthermore, wear and tear of components such as bearings, braking systems, and gears increases the motion resistance and reduces the energy efficiency. The lack of modern technologies, such as energy recuperation or lightweight construction materials, also limits the potential for energy savings in older rolling stock. It should also be noted that the thermal insulation used in older units is much less effective. Furthermore, older EMUs have greater leaks in doors and windows, which contributes to greater energy losses. Furthermore, older units require more frequent repairs and maintenance, which indirectly increases the consumption of energy resources throughout their lifecycle. Therefore, modernizing or replacing rolling stock with newer ones can significantly reduce energy consumption and improve the efficiency of rail transport. To emphasize, this is also the role of modern rolling stock in achieving carbon neutrality and reducing energy waste [65,66].

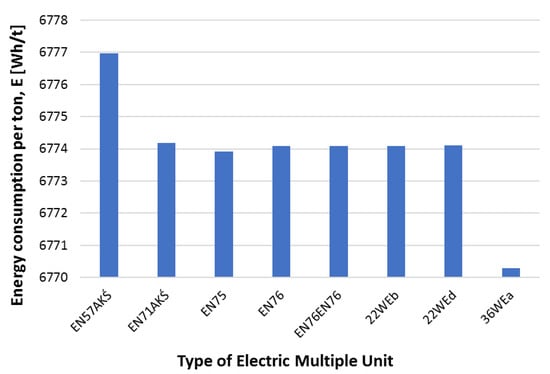

The investigations carried out confirm the above assumptions, particularly in the graph below (Figure 5), which shows the energy consumption of various types of electric multiple units, calculated by unit weight. The analysis included electric multiple units that operated on the same route in January.

Figure 5.

Comparison of electricity consumption by various types of electric multiple units per ton of weight that ran on the same route in January.

Koleje Śląskie operates exclusively electric vehicles, as all sections of the railway lines it operates on are fully electrified. Furthermore, it does not plan to purchase hybrid or gas-powered units in the coming years, as the carrier is financed from the provincial government budget and is not a typical commercial company tasked with generating revenue.

Only one other local government carrier, Koleje Dolnośląskie, purchased six three-car hybrid electric-diesel Impuls II multiple unit trains (NEWAG S.A.) in 2021. These are used to operate on sections that are not fully electrified. The Pomeranian Metropolitan Railway (Pomorska Kolej Metropolitalna) did the same in 2024. The method of generating electric power should also be taken into account; it must come from renewable resources.

These data are only available to the infrastructure manager (in Poland, it is PKP Polskie Linie Kolejowe) and PGE Energetyka Kolejowa; therefore, the authors are unable to determine the source of electricity for specific parts of the railway network.

The highest energy consumption per unit weight was demonstrated by EZT EN57AKŚ, which is the oldest of the analyzed units (produced in 1965), while the lowest energy consumption was demonstrated by the new generation unit 36WEa, one of the newest in the carrier’s rolling stock (produced in 2014). The energy consumption of other units on the same route is very similar.

The electric rail transport sector is the largest consumer of energy. It is divided into 70% for traction and 30% for station consumers. So, there is a need to implement effective solutions to reduce its consumption and carbon emissions. Most energy optimization strategies concentrate on the effective management of regenerative electric braking energy recovery and storage in transit systems, using DC electric rail [66].

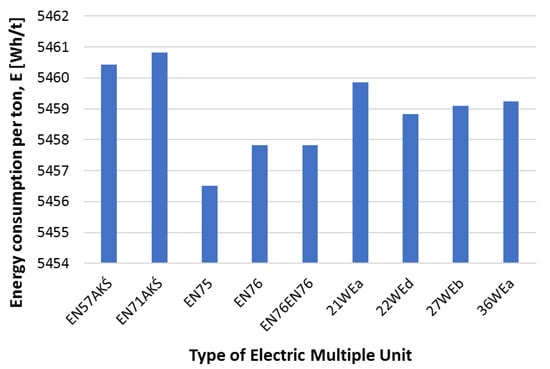

An analysis of the energy consumption per unit weight of passenger trains running on the same route in the summer (Figure 6) showed that the highest electricity demand was experienced by the two oldest units in the carrier’s fleet, the EN57AKŚ and EN71AKŚ. Furthermore, due to the summer season, energy was not used to heat the units, so the average energy consumption of 6770 Wh/t dropped to approximately 5460 Wh/t. Also, in the summer month, the demand for electricity of all units operating on the same route, regardless of their age, was very similar.

Figure 6.

Comparison of electricity consumption by various types of electric multiple units per ton of mass operating on the same route in July.

Artificial neural networks were used to answer the question of whether the age of electric multiple units alone has a significant impact on electricity consumption per ton of unit weight. An analysis of 14,570 electric multiple unit journeys was performed, covering various routes.

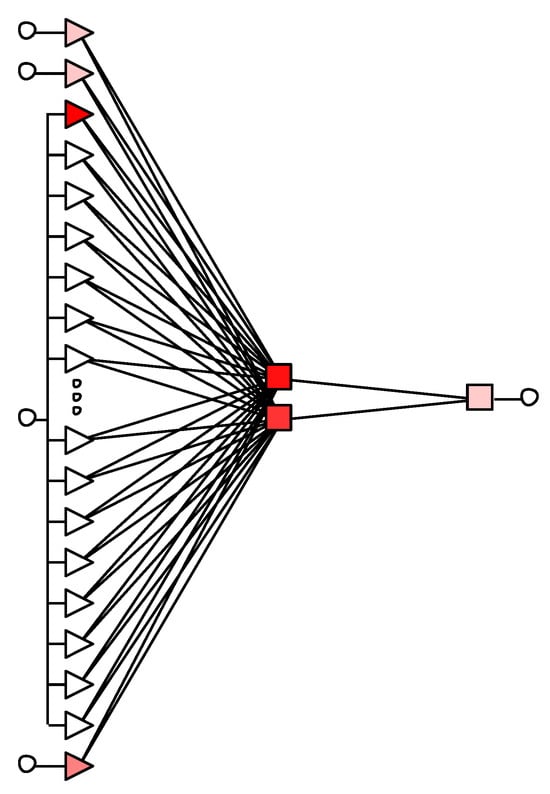

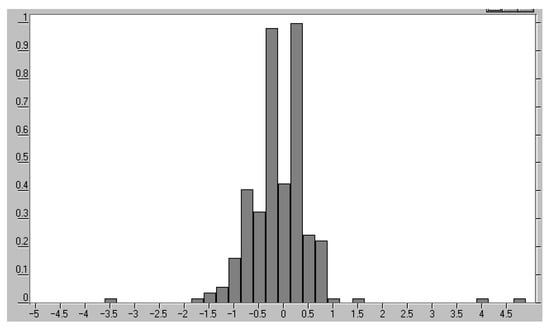

A total of 33 networks were tested and the efficiency of the best found network in Figure 7 (RBF, type 4:98-1-1:1) was determined to be very good, based on the regression coefficient—0.148432, correlation with empirical data—0.988923, and error—0.059972. As a result of the sensitivity analysis of the input factors, among which the influences of route length, unit weight, EMU type, EMU length (in meters), passenger coefficient, acceleration coefficient, operational work, transport work, heating coefficient, and energy loss coefficient were analyzed, it was found that the most important factors were route length (1), EMU type (2), EMU weight (3), and then the EMU acceleration coefficient (4).

Figure 7.

Schematic diagram of the developed RBF artificial neural network 4:98-1-1:1.

The regression statistics of the obtained network are presented in Table 3. The weight distribution of the resulting network is shown in Figure 7.

Table 3.

Regression statistics of the obtained network.

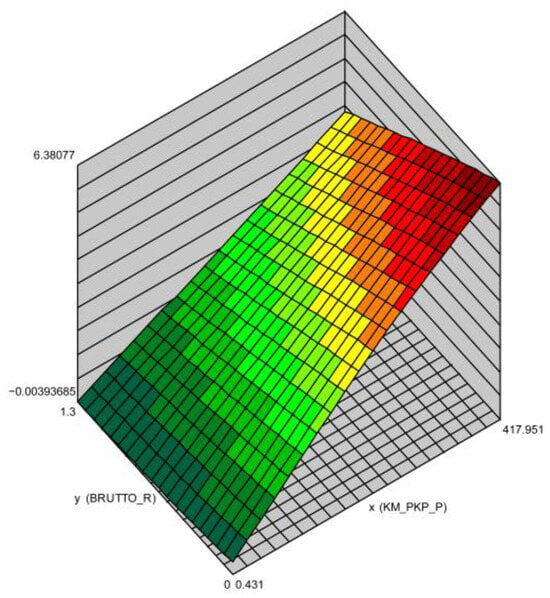

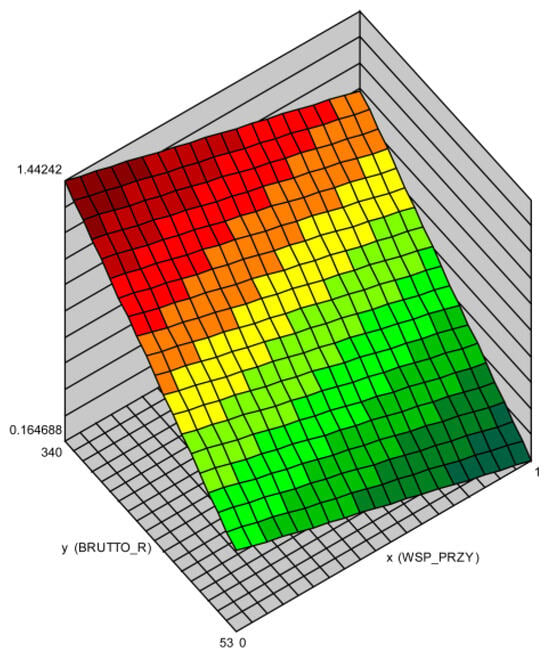

During the training process, the appropriate selection of connection weights allowed for the best representation of input–output data for the EMU’s energy consumption problem. Each time, the weight of connections between two neurons increased with the simultaneous activation state of both neurons (Figure 8, Figure 9 and Figure 10).

Figure 8.

Weight distribution, RBF network, type 4:98-1-1:1.

Figure 9.

Electricity consumption, depending on the mass of the EMU (y(BRUTTO_R) unit and the route length (x(KM_PKP_P).

Figure 10.

Electricity consumption, depending on the mass of the EMU (y(BRUTTO_R) unit and the acceleration factor (x(WSP_PRZY).

4. Multi-Criteria Analysis

The artificial neural network used in this paper is, of course, a tool: it is a predictive model, not an optimization model. Therefore, the optimization of energy consumption by electric multiple units (EMUs) in this article boils down to analyzing and answering the question of whether old, renovated (P4 and P5 major overhauls) EMUs can provide energy consumption equivalent or similar to that of new EMUs, in addition to passenger safety and travel comfort. The authors used the term “optimization” because selecting the units available to a carrier to operate a specific route during the current season is an element of energy consumption optimization. Therefore, the results of the analysis of the available data using ANN will enable the optimization of energy consumption by the carrier’s EMUs.

The analysis of the rail transport market using young people was based on the fact that they were students who frequently use public transport, including Koleje Śląskie (Silesian Rails). Furthermore, they are the most accessible group of opinion-formers for the authors of this article, who are employed at a university, educating future engineers. Furthermore, this was the first study in this area, aimed at understanding the opinions of users of both old and new EMUs.

In order to approach the topic scientifically and obtain a clear answer to the question posed in the title, a multi-criteria analysis was used, based on surveys conducted among people aged 18–65, at least via the Microsoft Forms platform, using online services.

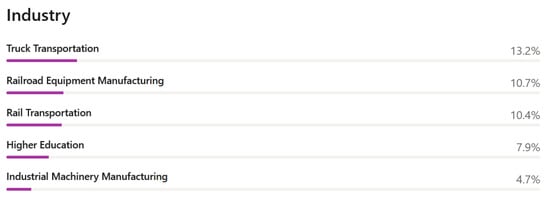

The survey was conducted among people from various metropolitan areas in Poland (Figure 11), including Bydgoszcz, Katowice, Krakow, Poznań, and Warsaw. In each of these areas, passengers use old, renovated, and new EMUs. The share of respondents by occupation is also presented (Figure 12).

Figure 11.

Share of respondents from various metropolitan agglomerations in Poland.

Figure 12.

Share of respondents from various professional areas.

When conducting the multi-criteria analysis, it was necessary to consider the factors that determine the choice of “renovate or buy electric multiple units.” As you might imagine, these are primarily financial factors. Therefore, the following criteria were analyzed:

- Cost of purchasing/renovating new EMUs.

- Servicing costs.

- Need for further inspections/renovations (e.g., P5) and when.

- Maximum operating parameters (e.g., speed) and operating comfort.

- Condition of the unit for operation under all permissible conditions (renovated EMUs typically retain old bogies and frames).

- Improving the competencies of technical staff.

- Financial resources from scrapping the units.

In the first case, the primary criterion was the purchase and operating costs of the electric multiple units. For each option (purchase/renovation), respondents could rate their assessment of this solution independently on a scale of 0–10 (0—worst and 10—best). Each criterion was assigned a weight, indicating the importance the respondent considered the criterion to have. The total weight for all criteria was one.

The analysis revealed that the multi-criteria analysis coefficient for the purchase of new units was 6.45, while for renovation, it was 6.6. On this basis, it can be concluded that there is a small difference in the results that can be ignored and therefore, it is not possible to clearly state which option is better (Table 4).

Table 4.

Results of multi-criteria analysis—basic criterion: EMU purchase and operating costs.

Expanding on this idea, it is worth emphasizing that while young respondents identified acquisition or modernization costs as the most important criterion in the multi-criteria analysis, they were not the only factor considered. Technical aspects, such as operational parameters and improved rolling stock energy efficiency, also appeared in the study, but these were deemed less important compared to direct costs. Similarly, technological factors related to access to modern solutions, improved travel comfort, and increased safety were ranked lower. Young people also recognized the importance of social factors, such as the impact on the attractiveness of public transport and its role in shaping urban mobility, but these factors were prioritized over economic considerations. Ultimately, the analysis showed that investment decisions in rolling stock—regardless of whether they involve modernization or the purchase of new vehicles—are, in the eyes of the young generation, primarily a matter of financial profitability, with other criteria playing a supporting role.

However, after changing the weights for individual criteria (if the multi-criteria analysis is conducted through the prism of passenger safety and comfort)—for example, criterion 1 < 5 and 2 < 6—and changing the criteria’s values based on safety and more educated personnel (criterion 6), it turns out that the multi-criteria analysis coefficient for the purchase of new units is 8.3, while for renovations, it is 6.2. In this case, the greater difference in these values indicates that purchasing new units is the better option (Table 5). This significant difference in assessment results from the experience of passengers who often use the services of various regional carriers and their awareness of passenger safety in rail transport.

Table 5.

Results of multi-criteria analysis—passenger safety and comfort criteria.

As can be seen, the analysis shows that purchasing new units is a significantly better solution, ensuring adequate passenger comfort and safety. Furthermore, it is important to remember that purchasing new rolling stock from Polish companies will translate into new jobs, and the development of technical expertise in Poland will guarantee a wide range of domestic technical solutions. We will not be limited solely to patents purchased from foreign companies: while analyzing this complex problem, it was noticed that there is no statutory limit on the time of use of railway rolling stock in Poland.

Newer vehicles are equipped with better brake controllers, which allows them to more effectively utilize blending (using different brake types, braking different axles, etc.), thus optimizing energy losses. It is also possible to equip refurbished old electric multiple units with a universal microprocessor-based electropneumatic braking control system, which will reduce energy costs (according to Barna and Stypka [67]). Alternatively, during the modernization of old units, they can be equipped with an asynchronous drive with regenerative braking, which will also enable the reduction in their operating costs (Biliński, Buta et al. [47]).

The artificial intelligence tool and survey used in the article were indeed intended solely for optimization purposes. The research was carried out for the Upper Silesia region (Poland) on railway routes operated by Koleje Śląskie. Considering the railway carrier Koleje Śląskie, the authors emphasize that the research results contained in the article, which are only predictions, can be used to optimize the structure of regional rail transport.

5. Conclusions

Renewable energy technologies, such as solar panels installed at train stations or in train power systems, can further reduce the rail sector’s carbon footprint. Integrating such innovations not only supports environmental protection but also lowers operating costs, making rail transport more competitive compared to other modes of transport. In the future, investments in technologies that combine sustainability with modern solutions will be crucial for the continued development of the rail sector.

The use of neural networks enables the effective identification and classification of factors influencing train energy consumption. Thanks to their ability to analyze nonlinear relationships and large data sets, these models enable the extraction of key operational and environmental parameters. As a result, precise strategies for optimizing energy consumption in rail transport can be developed.

It therefore seems advisable for the ordering party to require the rolling stock bidder to specify—during the tender procedure for the purchase of new or modernized rolling stock, and the role of scientist is, according to Ackoff [24]—that when thinking about ambitious goals, it is worth considering what their significance will be, even in several decades.

Concerning the energy consumption during traveling, it is worth underlining that the timing of obtaining the information about the predicted signal change, e.g., from S1 “Stop” to S2 “Permission to travel at the maximum allowed speed”, relative to the distance to the speed restriction in question, is crucial. Optimal timing helps to avoid excessive braking force (loss of kinetic energy) and, consequently, prevents extending the distance over which traction force would have to be applied to accelerate the train.

Modern trains, despite being equipped with energy-intensive systems such as air conditioning, consume less energy than refurbished units. This is due to the use of more efficient drive technologies, improved aerodynamics, and intelligent energy management systems. Modernizing older vehicles does not always compensate for their design limitations, which translates into higher operating costs.

In a multi-criteria analysis conducted to determine whether to modernize the existing rolling stock or purchase new ones, young respondents indicated that cost was a key deciding factor—both for purchasing new vehicles and for modernizing existing ones. In their opinion, the financial aspect dominated other criteria, such as energy efficiency, travel comfort, or environmental impact. This means that the economic viability of the investment remains the most important benchmark in the decision-making process, determining the direction of actions in the development and maintenance of the rolling stock.

Neural networks for predicting energy consumption in rail transport have several significant limitations. First, they require large, high-quality data sets, and in practice, rail data can be incomplete or difficult to obtain. Second, models are often treated as “black boxes,” making it difficult to interpret results and explain decisions in the context of safety or regulations. Third, neural networks can struggle to generalize when operating conditions change dynamically (e.g., different types of trains, infrastructure, or weather conditions). Fourth, the training process is computationally expensive and requires significant computing power, limiting their practical implementation. Fifth, there is a risk of model overfitting, leading to erroneous predictions in new, unfamiliar situations.

Of course, it should also be mentioned that the applied neural network model does not consider dynamic factors such as extreme weather and line congestion. It should be assumed that subsequent studies will introduce time-series data or multi-scenario simulations to enhance the extensibility of the research.

Also concerning general items, this research can lead to the conclusion that the better solution is to buy new vehicles, instead of modernizing them. However, the goal of the European Union was that alternative sources of energy would represent 20% of total consumption by 2020. According to the global strategy, these problems are being solved through a series of initiatives and innovations, including the introduction of natural gas buses in city transport. If taking the existing situation in city transport into account, the strategic proposal is to begin by retrofitting diesel buses into dedicated natural gas vehicle [68]. Alternatives are also possible in future building technologies, using, e.g., novel materials, as well as the lifetime elongation of used parts in safe conditions [69,70].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.K.; Methodology, J.K. and K.L.; Validation, W.G. and K.L.; Formal analysis, J.K. and K.L.; Resources, W.G.; Data curation, W.G.; Writing—original draft, J.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Bulakh, M. Evaluation and Reduction of Energy Consumption of Railway Train Movement on a Straight Track Section with Reduced Freight Wagon Mass. Energies 2025, 18, 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayed Gad, K.; Tonini, F.; Agati, G.; Borello, D. Emanuela Colombo, Energy demand prediction and scenario analysis for vehicle traction: A bottom-up approach applied to the italian railway system. Energy Rep. 2025, 13, 4196–4208. [Google Scholar]

- Sobkowiak, A.; Świechowicz, R. Energy balance of the passenger rail vehicles. Pojazdy Szyn./Rail Veh. 2020, 1, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kampczyk, A.; Gamon, W.; Gawlak, K. Integration of Traction Electricity Consumption Determinants with Route Geometry and Vehicle Characteristics. Energies 2023, 16, 2689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Z.; Zhao, N.; Hillmansen, S.; Roberts, C.; Dowens, T.; Kerr, C. SmartDrive: Traction Energy Optimization and Applications in Rail Systems, IEEE Transactions On Intelligent Transportation Systems. Available online: https://livrepository.liverpool.ac.uk/3093202/1/SmartDrive%20Traction%20Energy%20Optimization%20and%20Applications%20in%20Rail%20Systems_final.pdf (accessed on 15 January 2026).

- How Much Electricity Does a Train Use? Surprising Facts About Electricity. Available online: https://sofarsolarpoland.pl/ile-pradu-zuzywa-pociag-zaskakujace-fakty-o-energii-elektrycznej (accessed on 2 October 2025).

- Szeląg, A. Energy aspects of rolling stock modernization and increasing the speed of electric trains. TTS Tech. Transp. Szyn. 2009, 11, 29–34. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Szkopiński, J.; Kochan, A. Energy Efficiency and Smooth Running of a Train on the Route While Approaching Another Train. Energies 2021, 14, 7593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Q.; Dessouky, M.; Leachman, R.C. Modeling Train Movements Through Complex Rail Networks. ACM Trans. Model. Comput. Simul. 2004, 14, 48–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Široký, J.; Nachtigall, P.; Tischer, E.; Gašparík, J. Simulation of Railway Lines with a Simplified Interlocking System. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ter Beek, M.H. Models for formal methods and tools: The case of railway systems. Softw. Syst. Model. 2025, 24, 1935–1954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwaśnikowski, J.; Gramza, G. Simulation studies of traction energy consumption depending on the route profile. Pojazdy Szyn. 2004, 2, 77–80. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Kwaśnikowski, J. Reliability of data for train simulation. Mat. XKraj. Kon/Nauk. Pojazdy Szyn. 1994, 2, 150–160. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Szeląag, A.; Chudzikiewicz, A.; Nikitenko, A.; Nikšic, M. Re-Engineering of Rolling Stock with DC Motors as a Form of Sustainable Modernisation of Rail Transport in Eastern Europe After Entering EU in 2004—Selected Examples and Problems Observed in Poland and Croatia with Some Perspectives for Ukraine. Sustainability 2025, 17, 9486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raczyński, J.; Graff, M. New passenger rolling stock in Poland. TTS Tech. Transp. Szyn. 2014, 6, 20–29. [Google Scholar]

- Bartosiewicz, A.; Szterlik, P. New Silk Road—An Opportunity for the Development of Rail Container Transport in Poland? Nowa Polityka Wschod. 2020, 24, 9–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kłos, M.J.; Sierpiński, G. The Optimization of Intelligent Transport Systems: Planning, Energy Efficiency and Environmental Responsibility. Energies 2025, 18, 4518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skobiej, K. Energy efficiency in rail vehicles: Analysis of contemporary technologies in reducing energy consumption. Ail Veh. /Pojazdy Szyn. 2023, 3−4, 64−70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gołębiowski, P.; Jacyna, M.; Stańczak, A. The Assessment of Energy Efficiency versus Planning of Rail Freight Traffic: A Case Study on the Example of Poland. Energies 2021, 14, 5629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, A.; Araújo, A.; Carvalho, A.; Sepulveda, J. A New Approach for Real Time Train Energy Efficiency Optimization. Energies 2018, 11, 2660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ćwil, M.; Bartnik, W.; Jarzębowski, S. Railway VehicleEnergy Efficiency as a Key Factor in Creating Sustainable Transportation Systems. Energies 2021, 14, 5211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, S.; Schroeder, M.P. Aerodynamic Effects of High-Speed Passenger Trains on Other Trains. United States. Federal Railroad Administration. Office of Research and Development. Available online: https://rosap.ntl.bts.gov/view/dot/9450/dot_9450_DS1.pdf (accessed on 16 January 2026).

- Bałuch, H. Climate change and energy consumption—Examples of connections with railway construction. Probl. Kolejnictwa 2019, 183, 7–11. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Ackoff, R.L. Optimal Decisions in Applied Research; Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe: Warszawa, Poland, 1966. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Garlikowska, M.; Gondek, P. Types of risks in railway infrastructure investments. In Proceedings of the XI Konferencja INFRASZYN, Zakopanem, Poland, 18–20 April 2018. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Szkopiński, J. Optimization of traction energy consumption using intelligent rail traffic management systems. Transp. Overv. 2023, 6–8, 70–81. (In Polish) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PKP Polskie Linie Kolejowe S.A. Technical Guidelines for the Construction of Railway Traffic Control Devices; Ie-4 (WTB-E10); PKP Polskie Linie Kolejowe S.A.: Warszawa, Poland, 2019. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Jacyna, M.; Gołębiowski, M.; Krześniak, M.; Szkopiński, J. Organization of Railway Traffic; Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN: Warszawa, Poland, 2019; p. 384. [Google Scholar]

- Mańka, A.; Kisielewski, P.; Konieczny, J.; Labisz, K.; Ćwiek, J. Verification of a train on railway track simulation and optimization system. Transp. Probl. 2023, 3, 137–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iliev, I.; Suslov, K.; Kryukov, A.; Cherepanov, A.; Beloev, I.; Valeeva, Y. Modeling of energy recovery processes in railway traction power supply systems. Energy Rep. 2024, 11, 5163–5171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolejowy, K. Recuperation as a Way to Reduce Energy Costs on the Railways; Kurier Kolejowy: Warszawa, Poland, 2019. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Urbaniak, M.; Jacyna, M. Selected issues of multi-criteria optimization of railway traffic in terms of cost minimization. Probl. Kolejnictwa 2015, 2, 169. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Massel, A. Use of modernized railway infrastructure in Poland. In Zeszyty Naukowo-Techniczne; SITJ RP 2/123; Wydaw: Bielsko-Biała, Poland, 2021; Volume 2, pp. 271–282. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Massel, A. Methods and Tools for Assessing the Use of Transport Infrastructure on the Example of Research on the Railway Infrastructure of Central and Eastern European Countries in the Years 1989–2019; Wydnictwo Instytutu Kolejnictwa: Warszawa, Poland, 2020. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Jacyna-Gołda, I. Supply Network Efficiency Assessment Engineering; Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN SA: Warszawa, Poland, 2019. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Tomaszewski, F.; Licow, R. The impact of railway line modernization on the improvement of selected technical and operational parameters. Drog. Kolejowe 2015, 9, 152–155. [Google Scholar]

- Bałuch, H.; Bałuch, M. Determinants of Train Speed—Geometric Layout and Track Defects; Wydawnictwo Instytutu Kolejnictwa: Warszawa, Poland, 2010. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Jakubowski, A.; Jarzębowicz, L.; Karwowski, K.; Wilk, A. Energy efficiency of a rail vehicle under various load conditions. Eksploatacja 2018, 12, 44–48. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Douglas, H.; Roberts, C.; Hillmansen, S.; Schmid, F. An assessment of available measures to reduce traction energy use in railway networks. Energy Convers. Manag. 2015, 106, 1149–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durzyński, Z. Basics of the method for determining the parameters of energy-efficient driving of traction vehicles in agglomeration areas. Pojazdy Szyn. 2011, 3, 1–5. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Jakubowski, A.; Jarzebowicz, L.; Karwowski, K.; Wilk, A. Analysis of the Energy Consumption of a Rapid Urban Rail Vehicle Taking into Account the Variable Efficiency of the Traction Drive; Zeszyty Naukowe Wydziału Elektrotechniki i Automatyki Politechniki Gdańskiej: Gdańsk, Poland, 2018; pp. 32–36. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Urbaniak, M.; Kardas-Cinal, E. Optimizing the efficiency of regenerative braking in rail transport by controlling the arrival time at the station. Railw. Rep. 2018, 180, 61–68. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Rawicki, S. Energy-Saving Tram Rides with Vector-Controlled Induction Motors in Dynamic City Traffic; Wyd. Politechniki Poznańskiej: Poznań, Poland, 2013. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Janduła, M. It’s been 55 years of popularity “kible”. Available online: https://www.rynek-kolejowy.pl/wiadomosci/to-juz-55-lat-popularnych-kibli-80146.html (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Plewako, S. PKP Electrification at the Turn of the 20th and 21st Centuries: On the Seventieth Anniversary of PKP Electrification; Z.P. Poligrafia: Warszawa, Poland, 2006; pp. 159–173. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Konieczny, J. Buy or Modernize Rolling Stock? Komun. Publiczna 2018, 3, 36–41. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Biliński, J.; Buta, S.; Gmurczyk, E.; Kaska, J. Modern asynchronous drive with regenerative braking manufactured by MEDCOM for modernized electric multiple units of the EN57AKŁ series. TTS Tech. Transp. Szyn. 2012, 4, 20–25. [Google Scholar]

- Siwiec, J. Use of Hydrogen Fuel Cells in Rail Transport. Railw. Rep. 2021, 190, 113–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Electric Multiple Unit EN71AKŚ-101. Available online: https://ilostan.forumkolejowe.pl/index.php?nav=lok&typ=3&seria=66&lok=3500&numer=101&title=EN71AK%A6-101 (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Electric Multiple Unit EN71AKŚ. Available online: https://www.kolejeslaskie.com/spolka/tabor/ezt-en71-aks/ (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Electric Multiple Unit. Available online: https://ilostan.forumkolejowe.pl/index.php?nav=serie&typ=3&seria=66&title=EN71AK%A6 (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Electric Multiple Unit EN75—“FLIRT”. Available online: https://www.kolejeslaskie.com/spolka/tabor/ezt-en75/ (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Electric Multiple Unit EN75-001. Available online: https://ilostan.forumkolejowe.pl/index.php?nav=lok&typ=3&seria=70&lok=3512&numer=1&title=EN75-001 (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Electric Multiple Unit EN76—“ELF”. Available online: https://www.kolejeslaskie.com/spolka/tabor/ezt-en76-elf-22we/ (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Electric Multiple Unit EN76-009. Available online: https://ilostan.forumkolejowe.pl/index.php?nav=lok&typ=3&seria=28&lok=1470&numer=9&title=EN76-009 (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Electric Multiple Unit 21WEa—“ELF 2”. Available online: https://www.kolejeslaskie.com/spolka/tabor/ezt-21wea-elf-2/ (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Electric Multiple Unit 21WEa-001. Available online: https://ilostan.forumkolejowe.pl/index.php?nav=lok&typ=3&seria=368&lok=14120&numer=1&title=21WEa-001 (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Electric Multiple Unit 22WEd—“ELF 2”. Available online: https://www.kolejeslaskie.com/spolka/tabor/ezt-22wed-elf-2/ (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Electric Multiple Unit 22WEdg-012. Available online: https://ilostan.forumkolejowe.pl/index.php?nav=lok&typ=3&seria=377&lok=15412&numer=12&title=22WEd-012 (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Electric Multiple Unit 27WEb—“ELF”. Available online: https://www.kolejeslaskie.com/spolka/tabor/ezt-27web/ (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Electric Multiple Unit 27WEb-006. Available online: https://ilostan.forumkolejowe.pl/index.php?nav=lok&typ=3&seria=107&lok=5492&numer=6&title=27WEb-006 (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Electric Multiple Unit 36WEa—“IMPULS”. Available online: https://www.kolejeslaskie.com/spolka/tabor/ezt-36wea-impuls/ (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Another Impuls 2 Trains are Starting to Run in the Silesian Voivodeship. Available online: https://www.kolejeslaskie.com/kolejne-impulsy-2-ruszaja-na-tory-wojewodztwa-slaskiego/ (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Two Offers for Repairs to P4 Silesian EN57AKŚ. Available online: https://www.nakolei.pl/dwie-oferty-na-wykonanie-napraw-p4-slaskich-en57aks/ (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Koleje Śląskie with a Repair Contract EN57AKŚ. Available online: https://transinfo.pl/x/inforail/koleje-slaskie-z-umowa-na-naprawy-en57aks/ (accessed on 3 October 2025).

- Hu, H.; Liu, Y.; Li, Y.; He, Z.; Gao, S.; Zhu, X.; Tao, H. Traction power systems for electrified railways: Evolution, state of the art, and future trends. Railw. Eng. Sci. 2024, 32, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barna, G.; Stypka, M. Microprocessor control system for electropneumatic braking of multiple units. Pojazdy Szyn. 2009, 2, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milojević, S. Sustainable application of natural gas as engine fuel in city buses: Benefit and restrictions. J. Appl. Eng. Sci. 2017, 15, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konieczny, J.; Labisz, K. Structure and Properties of the S49 Rail After a Long Term Outdoor Exposure. Adv. Sci. Technol. Res. J. 2022, 16, 280–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labisz, K.; Konieczny, J.; Jurczyk, S.; Tanski, T.; Krupinski, M. Thermo-derivative analysis of Al-Si-Cu alloy used for surface treatment. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2017, 129, 895–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.