Abstract

Agrivoltaics is a rapidly expanding technology thanks to its energy, agronomic, and microclimatic benefits, which have been demonstrated in a variety of climatic contexts around the world. This study presents the first systematic review exclusively focused on experimental agrivoltaics field studies, based on the analysis of 82 peer-reviewed articles. The aim is to provide a cross-study comparable synthesis of how shading from different photovoltaic (PV) technologies affects microclimate, crop yield, and crop quality. The reviewed systems include four main categories of PV modules: conventional, bifacial, semi-transparent/transparent, including spectrally selectivity modules and concentrating photovoltaic systems (CPV). To handle heterogeneity and improve comparability, results were normalised against open-field controls as relative percentage variations. The analysis reveals a high variability in results, strongly influenced by crop type, climate, level of shading, and reduction in PAR (Photosynthetically Active Radiation). Studies conducted with the same shade intensity but under different climatic conditions show contrasting results, suggesting that there is no universally optimal agrivoltaics configuration. Nevertheless, the review allows us to identify recurring patterns of compatibility between crops and photovoltaic technologies, providing useful guidance for choosing the most suitable technology based on climate, crop physiology, and production objectives.

1. Introduction

According to the United Nations, the world population is expected to reach 8.5 billion in 2030 and 9.8 billion in 2050 [1]. This growth, together with urbanisation and industrialisation, will lead to a significant increase in demand for food, water, and energy [2]. This trend, combined with the decarbonisation targets to be achieved by 2030–2050, is exacerbating the problem of food, energy, and water security and is placing significant pressure on the global production system [3].

According to the water–energy–food (WFE) nexus paradigm, these three systems are closely interconnected and influence each other in various ways [4]. According to the FAO, the agricultural sector accounts for approximately 70% of global water demand, a resource that is essential for irrigation and livestock farming [5]. Moreover, irrigation requires energy, while water is essential in energy production processes, from hydroelectric to thermoelectric power plants, to the management of renewable sources [6]. At the same time, the increase in demand for food due to demographic growth also implies an increase in energy consumption linked to the modernisation and mechanisation of the agricultural system, the use of automated irrigation systems, and the spread of intensive cultivation. This dynamic creates a circular relationship between the three sectors [7].

At the same time, both food and energy production require the use of land, respectively, for the cultivation of agricultural products and for the installation of renewable energy plants. Electricity production from renewable sources, particularly photovoltaics, is growing rapidly thanks to lower costs and improved module performance. From 2013 to 2024, the spot price of PV modules fell by 84% [8] while the performance of the modules continued to improve [9]. As a result, global cumulative photovoltaic capacity grew to significantly exceed 2.2 TW by the end of 2024, while Europe showed strong and steady growth, installing 71.4 GW (62.6 GW of which was in the EU), led by Germany (16.7 GW) and Spain (7.5 GW) [10].

Despite the spread of photovoltaics distributed across rooftops and urbanised surfaces, this configuration is not sufficient to cover future global energy needs or to achieve the energy targets set for 2030–2050. For this reason, it has been necessary to develop innovative technologies. For example, CPV systems, which concentrate direct solar radiation onto small photovoltaic areas using dedicated optics, allow a greater amount of electricity to be produced with a limited footprint. However, this emerging technology is not yet widely used due to its high costs and structural complexity [11].

In this scenario, agrivoltaics represents one of the most promising strategies for optimising the use of resources in the water–energy–food nexus [12,13]. Agrivoltaic technology is based on a simple principle, first proposed in the late 1980s by Goetzberger and Zastrow [14], of raising photovoltaic modules off the ground to a variable height of approximately 2–3 m, depending on the crops, so as to allow the combined use of the land for the simultaneous production of electricity and agricultural products on the same land and thus mitigate the problem of competition for land between the energy and food sectors [15]. Unlike conventional photovoltaic applications, such as large ground-mounted or rooftop photovoltaic systems, agrivoltaics must simultaneously ensure energy production and maintain agricultural productivity. Therefore, photovoltaic modules also act as optical and microclimatic modifiers that influence PAR, crop development, and water requirements. Agrivoltaics can be applied to open-field crops, livestock farming, or agricultural greenhouse roofing [16,17].

The growth in installed agrivoltaic power has been significant in recent years [18]: it is estimated that global agrivoltaic capacity has grown from less than 5 MW in 2012 to over 14 GW in 2024, with a trend of constant expansion [19]. This expansion is linked to the significant advantages that have been demonstrated in connection with the implementation of this technology. In fact, in addition to the possibility of coexistence between crops and photovoltaics, agrivoltaics brings significant microclimatic benefits [20,21]. The shade generated by photovoltaic modules helps to reduce crop evapotranspiration, with a consequent reduction in water requirements, improving water use efficiency and fully embracing the logic of WFE [22]. Furthermore, shading modulates air temperature, improves relative humidity, and reduces heat stress and sunburn in locations characterised by arid and extreme climates.

However, in agrivoltaic systems, depending on the technology used, light is shared between photovoltaic panels and crops [23], thus varying the amount of PAR available to crops for their growth, affecting yield, product quality, and vegetative growth [24,25]. Not all crops react in the same way: some shade-tolerant species benefit more from agrivoltaic integration, while other crops may suffer significant yield losses that can also affect the profitability of farms [26]. This has led to the development of numerous innovations in this field, including the integration of semi-transparent, transparent, bifacial, coloured, and wavelength-selective modules; dynamic single-axis and dual-axis solar tracking systems; and even high row spacing configurations to optimise light sharing.

To date, despite the growing body of scientific literature, it is not possible to identify a universally optimal configuration for photovoltaic technology integrated into agriculture. This is because no single optimal combination of photovoltaic technology and crop cultivation: agrivoltaics performance depends on multiple factors: suitability, local climate, crop type, level of shading, system geometry, module height, optical transmittance, installation density, soil characteristics, and many other variables.

Previous reviews have already addressed agrivoltaics [27,28]; Nonetheless, current reviews amalgamate findings from experimental, modelling, and simulation-based evidence, which constrains study comparability. Consequently, a clear gap persists in the systematic synthesis of purely experimental data employing a uniform normalisation method compared to open-field controls. To address this gap, this study proposes a PRIMA-based systematic review focused exclusively on experimental scientific agrivoltaics studies developed globally. The aim is to evaluate the effects of shading generated by different photovoltaic modules on microclimate, crop yield, and crop quality, providing a methodological, cross-study comparable synthesis. The work is structured as follows: Section 2 describes in detail the methodology adopted, with particular attention to the bibliographic research process, the criteria for screening, inclusion and exclusion of articles, and the subsequent classification of the selected studies. Section 3 presents and discusses the results extracted, organised according to the category of photovoltaic technology used (conventional, bifacial, transparent/semi-transparent modules, and concentration systems). Each subsection describes the main experimental results and the environmental conditions in which they were obtained. All quantitative parameters (PAR, air/soil temperature, relative humidity, agricultural yield, quality, water savings, energy output) are also summarised in a comprehensive table in the Appendix A, which provides a comparative overview of the results; finally, Section 4 presents an integrated discussion aimed at identifying recurring patterns of compatibility between crops and photovoltaic technologies, with particular attention to the role of climate, shading intensity, and the agronomic characteristics of the species.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Objective of the Review

The purpose of this review is to conduct a systematic analysis of the energy and agricultural effects that the main photovoltaic technologies used in agrivoltaics systems have on crops. In particular, the effects of shading on the microclimate underneath the photovoltaic panels, energy performance, and crop yield and quality will be analysed. The review also aims to assess how these effects vary depending on the installation site and, therefore, the climate. The objective is to obtain a classification of crops based on the type of technology used, in order to identify recurring patterns of compatibility between crops and technologies. The review, therefore, not only summarises the state of the art of experimental research but also aims to provide a tool to support the selection of the most suitable photovoltaic modules for specific agricultural areas or systems and in the design of new agrivoltaics systems.

2.2. Bibliographic Search Strategy

The bibliographic research was conducted mainly using three of the leading international scientific databases: Google Scholar, Scopus, and Science Direct, selected for their extensive coverage in the fields of solar energy, photovoltaics, and agricultural engineering. Scopus and ScienceDirect guarantee reliability in the indexing of peer-reviewed articles, while Google Scholar allows the search to be extended to contributions that are not always indexed, such as conference proceedings and early access papers. Due to the recognised constraints in reproducibility of searches for Google Scholar and the publisher-specific range of ScienceDirect, Scopus was deemed the main resource for reproducible indexing, whereas Google Scholar and ScienceDirect served as additional sources to enhance coverage logic.

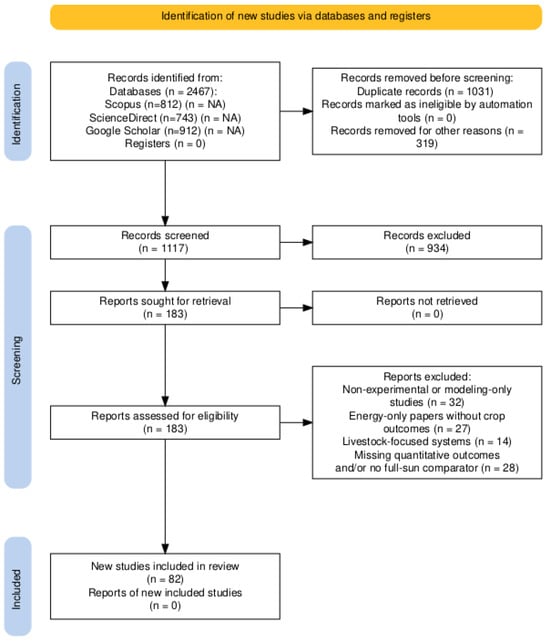

The review was conducted in accordance with the PRISMA 2020 reporting guideline [29] and the completed PRISMA checklist is available in the Supplementary Materials.

The protocol was not registered because the study aimed to synthesise heterogeneous experimental evidence without performing a quantitative meta-analysis. The research was performed using the following search string: (agrivoltaics OR APV OR “solar sharing”) AND (“PV panels” OR photovoltaics OR bifacial OR “vertical panels” OR “transparent PV” OR “semi-transparent PV” OR “spectrally selective PV” OR CPV OR “concentrator photovoltaics” OR “Fresnel lens concentrator” OR “dichroic film”) AND (“crop yield” OR biomass OR “vegetative growth” OR “leaf area index” OR evapotranspiration OR “water requirement” OR “soil temperature” OR “air temperature” OR PAR OR photosynthesis), considering articles written between 2010 and 2025. The identical search idea was utilised across all databases; the query was only mildly modified to fit platform-specific syntax while preserving keywords and search logic.

The search returned a total of 2467 articles, including 812 from Scopus, 743 from Science Direct, and 912 from Google Scholar. Reference lists of included studies were also screened to identify additional eligible records.

The search for articles was conducted from 1 October 2025 to 1 November 2025. All the main data were exported to a database and managed using Zotero software (version 6.0), which allowed for the automatic identification and elimination of duplicates by comparing DOI and bibliographic details (title, authors, year), subsequently followed by manual checks of uncertain cases’ logic.

After duplication, the number of articles was reduced to 1436. The study selection was performed by one reviewer, without the use of automation tools, and records were screened in two stages (title/abstract screening followed by full-text assessment), managed in Zotero, and tracked in an Excel file.

2.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

From the total number of articles identified (1436), those not written in English were excluded to ensure terminological consistency and comparability of results, resulting in a total of 1117 potential articles for analysis; therefore, no translation was required for screening or data collection. Articles published in peer-reviewed journals and conference proceedings were considered eligible. Conference proceedings were included solely when it was evident that they underwent peer review and when adequate methodological specifics and quantitative results were presented; otherwise, they were excluded.

From these, those that did not have an experimental approach were also excluded, such as purely theoretical, modelling, simulation, or numerical analysis-based studies. Although these works are useful contributions to understanding the potential of agrivoltaics, they do not provide direct measurements of the effects of photovoltaic modules on agriculture. Applying this filter, 183 articles remained. From these, articles dealing exclusively with the energy, electrical, or technical engineering aspects of photovoltaic technology were also excluded, such as studies on module efficiency or purely on structural configurations, without explicitly assessing their agricultural impact, since, in agrivoltaics, electricity production and agricultural production are two inseparable components of the same system and an analysis that does not consider crop response cannot be classified as an agrivoltaic study in the strict sense.

Similarly, research on systems integrated with livestock farming (e.g., agrivoltaics with grazing under the modules or applications for sheep and goats) was excluded. Although they fall within the agrivoltaics classification, they do not evaluate the physiological responses of plant crops and are therefore not relevant to the objective of this review.

Eligible studies examined agrivoltaic systems (open-field and/or greenhouse) and were conducted under real experimental conditions (field/greenhouse trials). That is, studies detailing field or greenhouse experiments that offered on-site measurements under photovoltaic shading conditions and included a comparison (full-sun/open-field control) to measure relative changes were taken into account.

Studies were considered eligible only if they reported quantitative results on at least one of the following outcomes: crop performance (yield and/or biomass and/or quality traits such as °Brix, sugar, or protein content), microclimatic parameters under/near the photovoltaic structure (PAR, air/soil temperature, relative humidity), and/or energy performance (electricity production). Studies were considered unsuitable if the results of interest were not measured or if quantitative results were not reported. The comparator consisted of full-sun (non-agrivoltaic) controls and percentage changes relative to full-sun controls were extracted as seasonal averages. In the end, a total of 82 papers were identified for analysis.

2.4. Classification of Selected Studies

The selected articles have been classified according to the type of photovoltaic module used, as these technologies represent the evolution over time of photovoltaic integration in agrivoltaics and differ in the way they filter, transmit, or concentrate solar radiation, thus influencing crop growth in different ways.

The first category includes conventional photovoltaic modules, which were the first to be used in agrivoltaic systems. This category includes single-sided monocrystalline or polycrystalline silicon modules, characterised by a single active surface exposed to direct solar radiation. The second category concerns bifacial photovoltaic modules, equipped with two active surfaces capable of absorbing not only direct and diffuse radiation, but also that reflected from the ground. This allows for a more even distribution of light and potentially less impact on the crops below. The third category includes transparent and semi-transparent modules, including spectrally selective ones. These devices are designed to transmit a significant amount of PAR, while filtering out wavelengths that cannot be used by plants and converting them into electricity. This reduces the shading typical of traditional technologies and improves compatibility with certain crops. The last and most innovative category includes CPV systems, which use optics such as Fresnel lenses or parabolic mirrors to convey solar radiation to high-efficiency multi-junction cells, allowing the diffuse component of the radiation to pass through to the plants. These systems are usually classified according to their concentration factor into LCPV, MCPV, HCPV, and UHCPV.

For each article belonging to one of the four categories, Section 3 provides a brief description of the experimental site and the technology used, as well as the experimental results concerning the effects on crops or the microclimate. Given the high heterogeneity of data concerning crops, climates, and technologies across different studies, the work was conducted as a systematic review with qualitative synthesis, without meta-analysis.

All relevant information is collected and organised in a table summarising: crop analysed, technology used, level of PAR or shading reduction, agronomic parameter considered, percentage change compared to the full-sun control, year, location, and bibliographic reference. Additional variables included the cultivation setting (open-field/greenhouse), PV technology, irrigation regime, and growing season. All quantitative and qualitative outcomes were extracted from the main text as well as from tables and figures by a single reviewer using no automation tools or figure extraction software, and the authors of the studies were not contacted. To improve traceability, all metric values were recorded alongside their source in the data extraction spreadsheet. If studies referring to the same experimental evidence were found, they were excluded if the most recent article did not provide new data. When the study reported no statistically significant difference compared to full-sun controls, it was indicated as “NV”. Formal risk of bias assessment and certainty of evidence was not performed due to the highly heterogeneous nature of the included studies. Reporting bias was not assessed as no statistical synthesis was conducted. The entire screening and selection process is reported in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

PRISMA 2020 flow diagram of the study selection process.

3. Results

3.1. Overview of Selected Studies

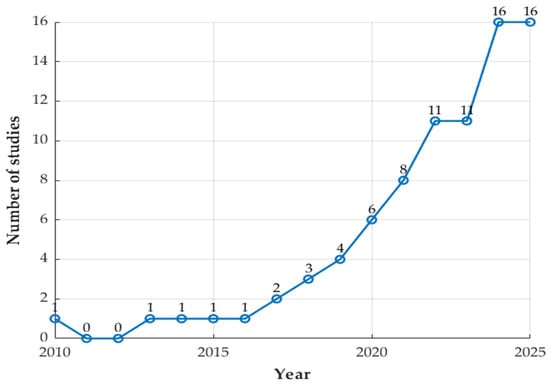

The 82 selected articles were first analysed to identify the author, year of publication, location of experimentation, technology used, and main parameters measured, and then systematically classified. Figure 2 shows the annual distribution of studies and highlights a strong growth trend: from 2010, the year of the first agrivoltaic prototype and a fully pioneering phase—in which the technology was developed only by a few research groups, mainly in France and Japan—until 2016, scientific production remained very limited. From 2020 onwards, publications increased sharply. They exceeded 10 studies per year in 2022 and peaked at 16 studies per year in 2024–2025. This increase is linked to growth in investment, the introduction of policies promoting the combined use of agricultural land, and the need to develop solutions in line with global decarbonisation targets.

Figure 2.

Number of experimental agrivoltaics studies per year.

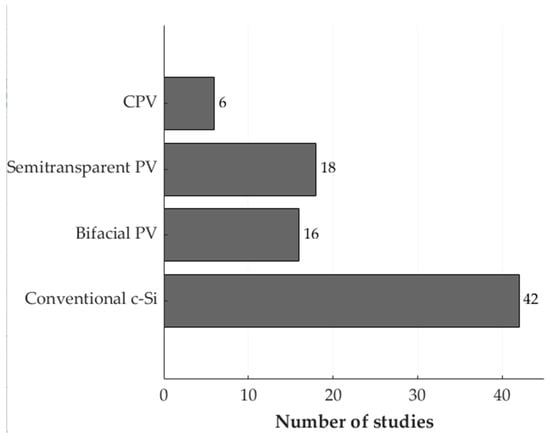

Figure 3 shows the distribution of studies according to the photovoltaic technology analysed, highlighting how, at present, the experimental literature is still strongly oriented towards mature and widely commercialised technologies. The dominant category is represented by conventional crystalline silicon (c-Si) modules, which alone account for 42 experimental studies (51.2%) of the entire sample. These are followed by bifacial modules (16 studies) and semi-transparent/transparent modules (18 studies), reflecting a growing interest in more advanced solutions capable of modulating the quantity and quality of light transmitted to crops. The most advanced technologies, such as a CPV system, account for only 6 experimental studies, highlighting that these solutions are still in the early stages of development and have not yet been confirmed from either an agronomic or energy point of view, mainly due to their high costs and structural complexity.

Figure 3.

Number of experimental agrivoltaics studies per PV technology.

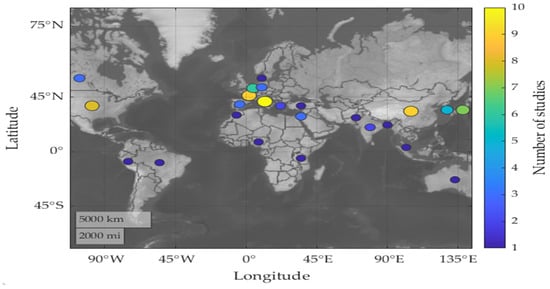

Finally, Figure 4 and Table 1 provide an overview of the geographical distribution of studies, showing how agrivoltaics is attracting interest on a global scale and not just in specific areas or continents. Circle size is proportional to the number of experimental studies conducted in each country. Europe emerges as the main hub for experimentation, with a high density of studies in countries such as France, Germany, Italy, Belgium, Greece, and the Netherlands. Asia is also a particularly active area, with numerous experiments conducted mainly in Japan, China, and South Korea, where the need to increase food security and high population density favour the development of solutions that preserve agricultural land without sacrificing energy production. The United States shows a stable presence, especially in arid and semi-arid regions such as California, Arizona, Colorado, and Oregon, where the microclimate generated by agrivoltaic modules can mitigate water stress and high levels of radiation.

Figure 4.

Number of experimental agrivoltaics studies per country.

Table 1.

Number of experimental agrivoltaic studies per country (N = 82).

The experimental data extracted from various studies are characterised by a very high degree of heterogeneity in terms of the variables considered, the methods used to report the results, and the reference conditions adopted. Among the studies examined, 82 studies were considered that focus on both energy and agricultural performance, some of which give priority to microclimatic monitoring (e.g., air/soil temperature, relative humidity, soil moisture, evapotranspiration, and water savings), while others focus on crop performance in terms of yield and quality. Light availability is expressed in various ways, such as reduction in PAR, transmitted PAR (% of control), global radiation, shading rate, or light quality classes. Table 2 highlights that the literature provides heterogeneous coverage of key results among photovoltaic technology families. Conventional and bifacial crystalline silicon systems, as more established technologies, are more frequently characterised by combined agronomic and microclimatic measurements, which allow for clearer qualitative patterns linking PAR reduction to crop yield sensitivity to be identified. Semi-transparent and spectrally selective systems more often report results related to optical transmission and quality. In contrast, CPV-based agrivoltaics remains underrepresented and is often reported with an emphasis on optical/energy concepts rather than full agronomic validation, confirming a serious gap in evidence.

Table 2.

PV technology categories in experimental agrivoltaics: frequency, typical shading, and commonly reported variables.

3.2. Energy, Agronomic, and Microclimatic Effects by PV Technology in Agrivoltaics Systems

This section provides a detailed description of the selected studies organised according to the four main categories of photovoltaic technologies identified in the experimental literature: conventional crystalline silicon modules, bifacial modules, semi-transparent and transparent systems, and CPV systems. For each article, a structured summary is presented that includes: a brief description of the technology used and the innovation proposed, the characteristics of the experimental site and the crops analysed, the effects observed on the microclimate (air and soil temperature, relative humidity, PAR reduction, water savings), the impacts on the energy performance of the system, the effects on agricultural yield and product quality. The aim is to provide a comprehensive and consistent overview of how different photovoltaic technologies affect crop growth, microclimate, and the overall efficiency of agrivoltaic systems. This qualitative section is supported by Appendix A, in which the same results are presented in tabular form, in a schematic and quantitative format. The table includes PAR reduction, relative yield, microclimatic measurements, product quality, and energy produced, all expressed as a percentage difference compared to the open-field control to guarantee traceability from distributions to specific experiments. Light availability is specifically indicated as a decrease in PAR (%) compared to the open-field control; when a study presents transmitted PAR as “% PAR” (proportion of control), the figures are converted to a PAR reduction using the formula (100 − % PAR). Furthermore, agronomic and microclimatic outcomes are presented as relative change (%) in comparison to the open-field control.

3.2.1. Conventional Monofacial Crystalline Silicon Modules (Opaque Modules)

The first agrivoltaic applications were developed using conventional opaque photovoltaic modules installed above or near crops. Their effects on agricultural yield, microclimate, and water demand have been demonstrated through experimental trials around the world.

Early experimental studies were conducted in France. In 2010, the first agrivoltaic prototype on durum wheat was developed [30]. The first validation was reported in 2013 when a system consisting of fixed-tilt monofacial crystalline silicon modules elevated at 4 m reduced PAR by 33% (half density) and 54% (full density) compared to open-field conditions. Results showed moderate decreases in air (−0.6 °C) and soil temperature (−3 °C), increased relative humidity (+5%), and reduced wind speed (−24%), improving overall water retention and lowering evapotranspiration (−27%). In particular, the effects were evaluated not only on wheat, but also on cucumber and lettuce. Crop yield decreased slightly (−7% to −20%) depending on the species and shading level, confirming that partial shading can enhance microclimatic resilience while maintaining acceptable productivity levels. [31]. Successively, in [32] the results relating to lettuce cultivation are analysed in detail. Despite the reduced availability of light, lettuce showed greater efficiency in the use of radiation (RUE) with an estimated increase in yield of around 18% and an increase in leaf area (SLA), a typical symptom of reduced light intensity conditions. Lettuce yield was maintained thanks to a higher radiation interception efficiency (RIE) under shade, while radiation conversion efficiency (RCE) did not change significantly. The increase in RIE was explained by a greater total leaf area per plant, despite a reduction in leaf number, and a different allocation of leaf area within the canopy, with larger maximum leaf size under shade.

Similar trends emerged from experiments beyond Europe. A study conducted in California (USA) aims to evaluate the agricultural yield of kale, Swiss chard, broccoli, peppers, tomatoes, and spinach under a traditional agrivoltaic system with a single-axis tracking system. The plants were grown in eight parallel rows and were subjected to different levels of shading, reducing the PAR intercepting the crops by 93% in the case of “intense shade”, 45% in the case of “moderate shade”, and 15% in the case of “almost full sun”, and comparing these results with the “full sun” case in the absence of agrivoltaic modules. The results showed that Swiss chard, broccoli, and spinach suffered the greatest reduction in agricultural yield, between 55% and 85%, while peppers and tomatoes achieved good yield levels in all conditions, making them the most suitable crops for agrivoltaics [33].

Tomatoes, tested in Turkey, confirmed these results, showing no significant variation in plant height, number of fruits, or chlorophyll content under similar modules but with single-axis trackers, and in some harvesting periods yields of over 9% were recorded [34]. In Bangladesh, on the other hand, with fixed modules, lower yields were recorded [35], while in Morocco, tomato cultivation showed overall comparable yields between the photovoltaic greenhouse and the control case [36].

In southern Italy shading effects were evaluated on chicory plantation. Four conditions were considered in this experiment: two with full light in the absence of agrivoltaic modules and two with agrivoltaic modules. The results show that, after 40 days, shading had a positive effect on crop weight, which was 69% heavier than crops grown in full sun. The four different areas were also subjected to different levels of irrigation, and in areas with less irrigation, plants grown in the shade produced 23% more than those in the control area [37].

Other studies have focused mainly on environmental responses: an experimental study conducted in Minnesota (USA) assesses the environmental effects associated with the installation of traditional modules on agricultural land. In particular, a 9.5 MW plant, built with crystalline silicon modules mounted two metres above the ground and oriented in an east–west direction, lowered the soil temperature compared to the control treatment thanks to the partial shading provided by the modules, making the soil more humid and nutrient-rich and thus helping to promote a more stable microclimate [38].

The positive microclimatic influence of shading also emerged in Mediterranean environments. In Kourtesi, Greece, on the other hand, the effects of a fixed agrivoltaic system tilted at 30° southwards on a plantation of aromatic herbs such as thyme, oregano, and Greek mountain tea were evaluated. In all three cases, the variation in weight and height was minimal compared to the control area in full sun. However, the shade generated by the panels resulted in an 8% reduction in soil temperature, which was shown to be more humid than in the control case, resulting in less water stress for the crops [39].

In Asia, several studies assessed shading impacts on staple crops. A study conducted in Japan, on the other hand, aims to assess the advantages and disadvantages of installing agrivoltaic modules on a rice crop. Three sites were considered for the experiment: site A with wooden panels installed at a height of 3 m with chemical fertiliser, site B with silicon panels with a power of 55 kW and 30% shade with chemical fertiliser, site C with panels with 50 kW power and 39% shade with chemical fertiliser, and site D with 12.2 kW panels and 34% shade with organic fertiliser. The results showed that rice yield decreases while protein levels increase as the level of shading increases [40]. The negative effects of shading on rice crops have been confirmed by experiments conducted in northern Japan, where the installation of crystalline silicon photovoltaic modules, with a system capacity of 9.9 kW, resulted in a reduction in PAR of 61–74% and a reduction in agricultural yield of between 23% and 31% compared to full-sunlight conditions [41]. However, the system achieves a positive LER of 1.24. The same results were obtained in Korea [42,43]. Also in Japan, it has been shown that a 25% reduction in shading could lead to a 23% reduction in wheat yield compared to full-sun conditions, but also an 11–16% reduction in protein content [44].

Experiments conducted in China on a large agrivoltaic park were based on the simultaneous cultivation of sun-loving species (kiwi, broccoli, cabbage, courgette, potato) between the modules and species that prefer shade. The former showed a reduction linked to the indirect shading of the modules, while the shade-loving crops benefited from the lower radiation, showing advantages from a microclimatic point of view [45].

In [46], a study conducted in the United States, in the state of Colorado, evaluates the effects of conventional photovoltaic modules on herbaceous forage crops growing in areas characterised by cold semi-arid climates. The system, consisting of modules supported by a single-axis tracking system, is divided into four zones: one zone between the panels where there is slight morning/afternoon shade, one under the modules, one on the eastern edge with full morning sun, and one with full afternoon sun. The results show that, although the modules reduced the annual PAR availability by about 38%, there was only a 6.1% reduction in productivity, thus demonstrating that C3 forage grasses are highly compatible with agrivoltaic integration.

Also in the USA, at Oregon State University Vegetable Farm in Corvallis, similar modules, oriented east–west and tilted at 18°, were tested on a tomato crop. The 482 kW system, with rows spaced 3 metres apart, was divided into three distinct light zones: the outer area in full sun (control), the area between the rows of panels subject to partial shading (inter-row), and the strip directly under the modules characterised by the maximum degree of shade (under-panel). From a microclimatic point of view, air temperatures were lowest under the modules. The soil temperature was 6 °C lower than in full sun, while soil moisture remained highest in the agrivoltaic areas. Tomato yield followed a downward trend as the level of shading increased, as did total biomass, while water productivity was lower in fully illuminated areas, demonstrating that agrivoltaics can be beneficial for shade-sensitive crops in conditions of limited water availability [47].

A study analysed the effect of traditional photovoltaic modules that generate uneven shading, which varies depending on the position of the panels and seasonal conditions, on the cultivation field. Crops such as celery and turnips have proven to be the most sensitive, with reductions of up to 40%, while crops such as potatoes, wheat, and beetroot have proven to be more tolerant to shade, maintaining yields between 75% and 95%, allowing Land Equivalent Ratio (LER) values greater than unity to be obtained [48]. Similar results were also obtained under simulated opaque modules, where a maximum yield reduction of 26% was achieved. In this case, the shade also resulted in higher concentrations of protein and potassium [49].

In Puglia (Italy), opaque amorphous silicon (a-Si) modules were installed above a vineyard, resulting in a significant reduction in PAR reaching the ground below. In particular, the effects of three levels of shading (full-sun, low-shade, high-shade) were evaluated during two years of experimentation. Under conditions of heavy shading, the experiments showed that the system contributes significantly to creating a cooler environment. This is more conducive to growth during the most critical hours and seasons, resulting in increased soil moisture, a reduction in soil temperature of up to 3.5 °C, and a reduction in wind speed, representing a promising solution in areas characterised by arid and semi-arid climates. In terms of agricultural productivity, the LS treatment yielded the best results, while in conditions of heavy shading, there was a reduction in sugar accumulation compared to the FS treatment. At the same time, the system allows for the production of approximately 53 kWh/m2/year, with an LER of 3.54 [50,51]. In the same region, the effects of opaque glass–backsheet system modules on tomato cultivation were compared with the effects of semi-transparent glass–glass systems. Under both systems, the microclimate showed lower air (−2 °C) and soil temperatures (−4 °C) and slightly higher relative humidity (+4–5%). Crop yield decreased by 12–16%, but fruit quality improved, with °Brix and dry-matter content increasing by 8–10%, demonstrating how moderate shading levels of 30–40% can maintain constant agricultural yields while producing electricity [52].

The effects on tomato cultivation were also evaluated in relationship with the integration of thin-film photovoltaic modules made of amorphous silicon (a-Si) into the roof of a greenhouse in Almeria (Spain). This integration resulted in a reduction in light transmittance of between 2% and 8%. The plants grown under the a-Si modules maintained production levels comparable to those in full sunlight, confirming that such a small amount of shading does not compromise vegetative development or overall productivity. The system generated approximately 2766 kWh per production cycle, of which approximately 768 kWh was consumed directly by the greenhouse, resulting in an NPV of approximately 640 EUR per cycle and a payback period of approximately 18 years [53]. In the same region, an experiment was conducted on a greenhouse, evaluating three levels of shading (0%, 30%, 50%), obtained by arranging opaque photovoltaic panels in a checkerboard pattern, which reduced PAR by 0%, 25%, and 48%, resulting in a temperature reduction of up to −2.2 °C and a 6% increase in relative humidity. The plants in the shaded treatments showed greater height, more leaves, longer internodes, and smaller stem diameters, indicating acclimatisation to the lower light level. Fresh mass was reduced by 15–30% under 30% shading conditions and by 25–50% under 50% shading conditions [54]. Also in Almeria, polycrystalline photovoltaic mini-modules arranged in concentrated-shade (CS) and scattered-shade (SS) patterns, both covering 22% of the surface area, were tested on lettuce. In particular, in the SS case, there was an increase in fresh weight of +46% in spring and +61% in summer compared to the concentrated-shade (CS) treatment, and +69–88% compared to full-sun conditions [55].

The effects of fixed photovoltaic modules (c-Si) were assessed in Emilia Romagna (Italy) on 70 hectares of permanent grassland divided into four sampling areas based on the level of shading. The results show that higher yields were obtained in the brightest areas, up to 78% compared to the full-sun control [56].

A study conducted in Sardinia (Italy) evaluated the effects of opaque photovoltaic modules placed on the roof of a greenhouse used for growing tomatoes. The multicrystalline modules caused an 82% reduction in the light reaching the soil, resulting in a reduction in crop yield from 3.4 kg m−2 under the plastic roof to 2.0–2.4 kg m−2, while fruit dry-matter content increased by about +15%, indicating higher sugar concentration and improved firmness [57].

In Brazil, 210 polycrystalline silicon modules, with a system capacity of 68 kWp, that can help to produce 11.5 MWh per year, elevated by 7–8 m were installed above a sugarcane field. The results, at shading levels of approximately 35%, showed an increase in stalk yield of 38.8%, resulting in a LER of 1.69 [58]. In India, on the other hand, the effects of these panels were evaluated on a wheat crop. The modules, mounted on a fixed structure at a height of 3.7 m, generated a reduction in PAR incident on the crop of between 26 and 68% in partially shaded areas and 73 and 90% in completely shaded areas, with a consequent improvement in the microclimate but a reduction in the agricultural yield of 26% and 63%, respectively [59].

Also in India, a similar technology was tested on a tomato crop, demonstrating that approximately 50% shading does not cause significant changes in crop yield [60].

In Montpellier, an agricultural system built with bifacial modules was tested on a 1720 m2 corn field. The modules were mounted both in a fixed configuration and with a north–south single-axis tracker with three levels of shading intensity: BP (moderate shade), HP (intense shade), or LP (very intense shade). The results show that moderate shading (30–35%) allows agricultural yields to be maintained compared to open fields, while heavy shading can lead to yield losses of up to 30–50% [61].

In Malaysia, a study evaluated the effects of simulated agrivoltaics modules which, positioned 1.8 m above the ground, reduce incident solar radiation on various tropical horticultural crops by 70–90%. For okra, there was a decrease in plant height (−18%), number of leaves (−27%), leaf area (−39%), fresh weight (−55%), and dry weight (−45%). For green spinach, the response was even more pronounced, with −54% in height, −43% in number of leaves, −82% in leaf area, and a drastic reduction in fresh weight (−90%) and dry weight (−80%). At the same time, under the panels, the soil temperature dropped by about 1.5–2 °C, the air temperature by 1.2–2 °C, and the relative humidity was +5 to +9% higher than in areas in full sun [62]. In the temperate climate of eastern Japan, maize was tested under two configurations: a high-density configuration with 48 modules and a low-density configuration with 24 modules. The results show that the low-density configuration actually increases the dry mass of maize by 5% compared to open fields [63].

In Tanzania, a 36.3 kWp experimental plant built with silicon modules mounted on a fixed structure inclined at 10° and 3 m high was tested to assess the effects on various crops (beans, chard, maize, onions, peppers, aubergines), showing significant variability in production response: significant increases for beans (+123.7%) and chard (+90.3%), stable yields for maize, and reductions for onions (−15.9%), peppers (−31.5%), and aubergines (−17.5%). Shading allowed average irrigation savings of 12–14% (up to 22% in the dry season). At the same time, there was a reduction in soil temperature (−3 °C) and air temperature (−2.3 °C), with an increase in relative humidity (+8 to +12%), creating a more stable microclimate for crops. From an energy perspective, the system produced 12.55 MWh/year with a module degradation rate of 0.5%/year and an average LER of 1.88, indicating a total soil productivity almost double that of isolated agricultural or photovoltaic practices [64].

In France, in 2022–2023, a dynamic agrivoltaic system with opaque panels was tested on a nectarine orchard. The results, compared with those obtained in the open field, show constant increases in night-time temperatures under AV compared to the control: +0.27–0.47 °C in the air, +0.25–1.29 °C via frost sensors, and up to +1.61–1.69 °C in buds, demonstrating how agrivoltaics can contribute to spring frost protection [65].

In the same country fixed PV panels were installed 4 metres above the ground on an alfalfa crop, which, depending on the year, recorded an overall increase in soil productivity of 73–81% compared to the open-field control [66].

In Italy the agronomic and qualitative performance of six species of aromatic and medicinal plants (sage, oregano, rosemary, lavender, thyme, and mint) grown under a dynamic single-axis tracking agrivoltaic system installed in San Severo (FG), in southern Italy, was compared with open-field cultivation. The rotation of the system generates two distinct zones: an area that is constantly shaded and an area with intermittent shading during the day. Among these species, sage showed marked increases in height and width when grown under the panels. No statistically significant differences emerged for oregano and thyme, but even for these species, the values under the system were slightly higher than the control [67].

A study conducted in Japan assessed the effects of photovoltaic panels integrated into the roof of a greenhouse on the growth of Welsh onions. The photovoltaic system installed in the greenhouse consisted of two different panel configurations: PVs (solar absorbing type) and PVc (colour PV type), each characterised by a different active area and light transmittance. In the first case, there was a moderate reduction in fresh biomass compared to the control, indicating that this type of panel induces shading compatible with crop growth. On the contrary, the PVc configuration, characterised by lower light transmittance, resulted in a more marked reduction in both the fresh weight and dry biomass of the plants, highlighting the crop’s greater sensitivity to shading intensity [68].

In this field, an agrivoltaic system based on conventional silicon photovoltaic modules was combined with a grooved glass plate to refract and redistribute light evenly in the shaded area. The results, concerning a specific crop, were compared with those of a similar crop under a conventional system where growth was slowed down with taller plants but with longer, thinner, and less consistent leaves, typical of an environment with insufficient light. CAS causes a drastic drop in production: fresh yield decreases by −53.5% and dry yield by −60.5% compared to plants grown in full sun, while the presence of the glass plate eliminates this reduction and allows normal productivity levels to be restored [69]. Traditional systems have also been tested on broccoli in Korea [70] and on grapevines of the Corvina variety in northern Italy [71].

3.2.2. Bifacial Modules

Bifacial photovoltaic systems have been widely used around the world as a potential integration in agrivoltaics. These allow solar radiation to be captured from both sides, also exploiting the reflected component of solar radiation. In France, for example, an experimental study was carried out on a Golden Delicious apple orchard to evaluate the effectiveness of a dynamic agrivoltaic system using bifacial monocrystalline silicon modules mounted on a single-axis north–south tracker at a height of 4.5 m. The system reduced the PAR incident on crops by 40–50%, resulting in a decrease in air temperature of approximately 11–13% and an increase in relative humidity of 15%, leading to a reduction in water requirements of 6% to 31%, without compromising fruit yield [72]. At the same time, the experiment demonstrated that this type of module reduces damage from sunburn, one of the main factors causing economic losses for producers, caused by excessive solar radiation and the resulting high temperatures on the surface of the fruit [73].

In Germany, winter wheat was grown for four consecutive seasons, from 2016 to 2020, simultaneously with the 194 kWp AV system consisting of bifacial modules raised 5 metres above the ground and on an adjacent unshaded plot used as a reference. The results show that agrivoltaics helps mitigate the effects of drought on winter wheat, maintaining yields comparable to those obtained in open fields [74].

The effects of bifacial modules on crops are compared with those of monofacial and semi-transparent modules on a bean plantation, famous for its ability to grow in a wide range of climates but with variable yields depending on temperature, water availability, and soil quality. The study, conducted in Chachapoyas, located in north-eastern Peru at 2300 metres above sea level, in a temperate-humid climate, demonstrated that bean plants grew taller (up to 71.5 cm) under bifacial modules because the greater amount of diffused light available in such conditions promotes stem elongation, resulting in heavier pods and, therefore, a higher yield per hectare [75].

The bifacial modules were also tested in Germany as part of the APV-RESOLA project. The 194.4 kWp plant produced approximately 1265 kWh kWp−1 yr−1 and was tested on clover grass, celeriac, potato, and winter wheat crops. The irradiance under the modules was 70–75% of full sunlight. The tests yielded different results depending on the year, demonstrating that shading can have a positive, neutral, or negative effect, depending on average annual temperatures. In particular, agrivoltaics in temperate climates can reduce yields in normal years but potentially improve them in hot, dry seasons, highlighting their increasing agronomic value in conditions of water and heat stress [76].

In general, however, winter wheat and potatoes were found to be the most shade-sensitive crops, while celeriac showed greater adaptability [77]. The results for potatoes were also confirmed by a study conducted in Punjab, Pakistan, where the yield was slightly higher under AV (+8.7%) [78] while the negative effects of shading on wheat have also been demonstrated in Belgium, where yield losses of between 33% and 46% have been recorded. During the same experiment, beetroot, on the other hand, suffered a loss of only 19% and a reduction in sugar content of only 1.7%, proving to be less sensitive to shading and resulting in a LER greater than 1 (1.22) [79]. In the same country, similar experiments were conducted on beetroot in 2021 and 2022, but they showed that the impact of the modules on the crop depends heavily on seasonal weather conditions. In fact, in 2021, a rainy year, shading led to significant losses in beet yield, while in 2022, a dry year, the same shading helped protect crops from excessive temperatures, limiting losses [80,81]. Also in the same country, wheat, tested under similar conditions but with high biaxial tracking systems, showed no significant variations in yield [82].

In Denmark, on the other hand, vertically arranged double-sided systems, with a 344 MWh·ha−1 electrical producibility per year, made it possible to maintain constant wheat yields compared to open fields, with a weight reduction of only 0.9% caused by a 25% decrease in incident PAR. At the same time, the same modules arranged at a 25° angle facing south resulted in a significant reduction in grass-clover yield (−18.2%) [83].

Double-sided modules were tested in South Korea, in Naju-si, on kimchi cabbage and garlic, which showed yield reductions of between 17 and 21% and between 7 and 21%, respectively, compared to the open-field control [84].

In Nigeria, on the other hand, the compatibility of bifacial modules with green bean cultivation was assessed, considering five local varieties—Tvr95, Tvr129, Tvr153, Tvr184, and Tvr186—and three environmental configurations: EPV (east–west oriented bifacial panels), WPV (west–east oriented bifacial panels), and NPV (no panels, full-sun). The study found that EPV systems showed a better balance between shading and radiation, resulting in a decrease in PAR of only 14.5% and a consequent increase in yield of 23%. In the case of WPV, on the other hand, there was a reduction in yield of approximately 19% [85].

In China, rice yield was tested within a fixed agrivoltaic system with bifacial modules. The system generates three different shading conditions: BP (Between Panels), characterised by moderate shading; HP (High Panel), an area located under the upper edge of the modules, with more severe shading; and LP (Low Panel), an area below the lower edge of the modules, where the shading is almost total. The three areas are therefore characterised by increasing levels of shading, corresponding to decreasing plant heights. In fact, height is reduced by 14.5% in BP, 22% in HP, and 26.8% in LP, while the number of tillers, which is fundamental in determining the final number of ears and therefore the yield, decreases in a similar way, with slight losses in BP and much more significant losses in HP and LP [86]. In South Korea, however, similar modules but in a vertical configuration resulted in a maximum reduction of 7% [87].

3.2.3. Semi-Transparent and Transparent Photovoltaic Systems

As shown in Section 3.1 and Section 3.2, opaque, single-sided and double-sided modules can lead to losses in yield and quality for certain types of crops, depending on the microclimate of the installation site. Among the various innovative technologies being tested in the field of agrivoltaics is the use of semi-transparent modules.

These have been tested in various parts of the world. In Mantua, Italy, the effects of installing semi-transparent modules were compared with the effects of full sun exposure, demonstrating that partial shading allows for greater fresh mass of lettuce and no change in the number of leaves, while still helping to reduce the negative effects of soil evapotranspiration [88].

These modules are also well suited for integration on greenhouse roofs. For instance, laminated glass panels with PVB (polyvinyl butyral) interlayers containing luminescent materials were tested in Perth (Australia). The system had an installed capacity of 6.1 kWp and was deployed across four greenhouse bays (200 m2 each), using a 12-panel array. The measured electricity production ranged from 1.1 kWh/day in winter to 2.0 kWh/day in summer. These materials allow sunlight, and therefore PAR, to pass completely through the panel to reach the crops, while blocking UV and NIR components. Experiments have shown that these technologies improve the thermal insulation of the greenhouse by maintaining higher internal temperatures at night and reducing overheating during the day [89].

Thin-film modules (Cd-Te), with different levels of transparency (10–80%), were tested to assess the effects on agricultural yield and morphological parameters of strawberries. The results show a bell-shaped curve response: transparencies above 40% maintain productivity above 80%, while maximum yield is achieved at transparency values of 70%. With regard to biometrics (number of leaves, flowers, and height), an upward trend was observed for high transparency levels, while low transparency levels (10–30%) proved to be detrimental [90,91].

Organic semi-transparent modules (OPV) were tested in tomato greenhouses. In particular, two technologies with different transmittance were considered: one with maximum transmittance of 28.8% (blue) and one with 32.2% (red). Both technologies resulted in a reduction in radiation of approximately 38%, leading to a reduction in air temperature, especially in the middle of the day, and lower leaf temperature in both summer and winter, creating a more favourable microclimate and reducing heat stress. Agricultural yield was reduced by approximately 15% in the first case and 9% in the second case in summer, while in winter the reduction was smaller and similar in both cases. The quality of the fruit showed no significant differences compared to the control [92]. Similar results were achieved in Kunming, China, with greenhouses made of semi-transparent BIPV modules [93].

Transparent photovoltaic modules and photosensitive materials were tested on basil, petunia, and tomato plants. Specifically, seven covering materials were tested, including three neutral density panels (33%, 58%, and 91% PAR), two NIR-cutoff filters (CO700 and CO770), and two PAR-selective filters (CO550a and CO550b), compared with a high transmittance control. The results show that the determining variable of the production response is not the spectral selectivity of the panel, but rather the overall PAR transmission. Basil and petunia showed higher yields and quality up to maximum shading levels of 34–40%, while higher shading values resulted in a decrease in chlorophyll content and a reduction in the number of branches or flowers per petunia. Tomatoes, on the other hand, showed tolerance for maximum shading levels of 25–37%, proving to be more sensitive to shading than other crops [94]. In south-western China, on the other hand, three levels of shading (19% (T1), 30.4% (T2), and 38% (T3) PV coverage) were tested for three years (from 2018 to 2020) using thin, semi-transparent amorphous silicon modules, compared with an area in full sunlight, on a kiwi crop. In all cases, the chlorophyll content showed no differences between treatments, but the plants modified their leaf structure and increased LAI to improve light interception. The yield decreased proportionally to the increase in shading: between 2 and 5% in T1, between 37 and 39% in T2 and T3. Partial shading resulted in a reduction in evapotranspiration of 17% in T1, 28% in T2, and 31% in T3, respectively [95].

The semi-transparent modules, in this case made of monocrystalline silicon, with a transmittance of 40%, were tested on a pear orchard. The parameters were monitored for two years and the results show that a reduction in average PAR of 28–35% can lead to a reduction in yield of approximately 26%, mainly due to a lower number of fruits per tree, while the average weight of the fruits and commercial uniformity remained substantially unchanged. The quality parameters—soluble solids, colour, firmness, and storage capacity—also showed no significant differences between the agrivoltaic treatment and the open field, highlighting the cultivar’s good tolerance to light reduction [96]. Single-sided semi-transparent photovoltaic modules were tested for three years in Flanders, Belgium, to assess their effects on a pear orchard. The plants, with an interception of approximately 75% compared to the full-sun control, showed a reduction in leaf flavonoids, a slight increase in SLA, and no changes in photosynthesis, but an average reduction in yield of approximately 15%. Fruit quality (°Brix, hardness, starch index) was not compromised [97].

Semi-transparent coloured solar panels (a-Si, thin-film) installed in an experimental agrivoltaic system, with a reduction in solar radiation of 45–58%, were compared with greenhouses equipped with transparent glass in Melegnano (Italy), on basil (in spring–summer) and spinach (in autumn–winter). Despite this significant decrease in incident light, both crops showed greater photosynthetic efficiency of the available light: +63% in basil and +68% in spinach, an effect linked to the higher proportion of red radiation under the photoselective panels compared to the control case. Total biomass was reduced by 30% in basil and 28% in spinach, but leaf biomass, the marketable part, was reduced by only 28% in basil and only 26% in spinach. However, there was a significant increase in protein content: 14.1% in basil and 53.1% in spinach. Obvious morphological effects included larger leaves in basil and longer stems in spinach, consistent with a physiological response to optimise light capture [98].

In Beijing (China), the effects of semi-transparent photovoltaic modules (41.5% shading) were compared with those of traditional opaque crystalline silicon photovoltaic modules (74.7% shading) and with those of cultivation in full sun. Under moderate shading conditions, soybeans showed a moderate reduction in total dry biomass (28%), while higher shading values resulted in losses of up to 72% [99].

Other innovative technologies such as double-sided glass Si, double-sided plastic Si, and semi-transparent OPV were installed in Israel inside a Mediterranean polytunnel greenhouse above 400 cucumber plants. The results, monitored weekly, showed a more marked reduction in PAR radiation for OPV (−34%), which, however, led to a lower yield than Si-glass due to the presence of a spectrum more favourable to the red–blue bands. The LER was greater than 1 in all cases but also greater for OPV (1.56), characterised by lower energy efficiency, which is however compensated for by agricultural efficiency [100]. Similar modules were tested in Arizona, USA, in a greenhouse experiment on tomatoes, reducing the total solar radiation transmittance by approximately 40% and the PAR (400–700 nm) by approximately 37% in the shaded area. This stabilised the canopy temperature, while in terms of production, the fruits showed a delay in development and similar cumulative yields compared to the control case [101]. Similar results were obtained in Israel [102].

Another interesting experiment on lettuce is being conducted in a controlled biome that replicates the summer conditions of London (ON Canada). The tests aim to evaluate CdTe modules with uniform illumination (40%, 50%, 70%) and bifacial c-Si modules with non-uniform illumination (44%, 69%), with a system capacity of 175 Wp. The best performance was achieved for the 69% c-Si treatment, which achieved the same yield as the control, while the CdTe modules, despite having high transmittance, were characterised by too weak a transmission of diffuse radiation, resulting in lower yields (−6% on average), especially at 40% [103]. In Fort Collins, Colorado (USA), in a semi-arid climate, lettuce was tested under opaque CdTe modules with frames, opaque frameless CdTe modules, and semi-transparent frameless CdTe modules with 40% transmittance, with the highest fresh and dry biomass values found in the latter case compared to all other treatments [104].

The effects of strawberries were also evaluated in Greece using semi-transparent photovoltaics (51% theoretical shading) positioned in two parallel rows (A: less shading; B: more shading), on which the morphological, productive, and biochemical parameters of the fruits were measured. The most relevant results showed that, although the fruits harvested in row A, with greater radiation, were heavier, the fruits in row B, characterised by more shade, showed higher quality, an increase in total phenolic compounds, and antioxidant activity [105].

3.2.4. Concentrated Photovoltaic Systems

As shown in Section 3.2.1 and Section 3.2.2, opaque, single-sided and double-sided modules can lead to losses in yield and quality for certain types of crops, depending on the microclimate of the installation site. Among the various innovative technologies currently being tested in the field of agrivoltaics is the use of CPV modules. However, experimental agrivoltaic applications based on this technology remain limited in the literature analysed.

In 2015, the first design of a concentrated agrivoltaic module made with Fresnel lenses was carried out, in which diffused light passes through the module and reaches the crops with a transmittance of over 70% [106].

These, which are still characterised by the absence of a standard configuration, have been tested, for example, in China, where an experimental prototype has been built with a selective optical layer that allows the wavelengths useful for photosynthesis (mainly red and blue) to pass through and reflects the remaining components of the solar spectrum towards a small photovoltaic module. The reflective surface is shaped to concentrate non-PAR on the cell, increasing its efficiency without penalising PAR transmission to the agricultural soil. The system was tested on a lettuce crop and the results were compared with those of plants grown in open fields. The system produced taller plants with greater fresh and dry weight than those grown in full sun, thanks to better light distribution beneath the modules [107]. This prototype was compared with one made with Fresnel lenses [108].

In 2019, however, two experimental modules were built in Japan, one featuring Fresnel lenses with a conventional-scale multi-junction cell that generates a clear separation between the portion of radiation intended for electricity production and that transmitted, and one using a low-density microlens array, allowing significantly higher transmittance of direct and diffuse light towards the ground, favouring greater illumination of the ground compared to the first prototype.

A CPV integrated with a spectral splitting film, has been designed as a potential covering for greenhouses. The system allows VIS radiation (400–780 nm) to be transmitted to crops and NIR radiation (780–2500 nm) to be reflected towards a GaInP/GaAs/Ge CPV cell, achieving a NIR blocking rate of 78% [109].

These latest studies do not include any agricultural experimentation, nor measurements of yield, biomass, physiology, or crop microclimate [110], representing a serious gap in the research, since most concepts related to CPV have been evaluated primarily from an optical/energy perspective.

The only study that presents experimental results on crop performance is [111]. This study, conducted in China, proposes and experimentally demonstrates an innovative system based on the spectral separation of solar radiation using dichroic films and a CPV system capable of concentrating wavelengths not used by plants. The results show that under these modules it is possible to obtain taller and heavier plants than those exposed to direct sunlight, thanks to an increase in the photosynthetic rate of up to 28% for lettuce, resulting from optimisation of the radiation transmitted for photosynthesis.

In this type of system, the NIR component, responsible for overheating and excessive evaporation, is completely reflected for electricity production.

4. Discussion

The scientific literature analysed includes 82 experimental studies conducted in agrivoltaic environments across more than 20 countries over the last 15 years, highlighting the wide variety of photovoltaic technologies adopted in agrivoltaic applications.

Among the studies reviewed, PAR reduction ranges from minimal to extreme levels, between 4% and 95%, with a central tendency towards moderate shading of 48%. Even with significant light reduction, agricultural responses are not always negative. Examining research, yield responses range from significant losses to considerable gains, from approximately −63% to +124%, with the central part of the distribution clustering around near-neutral or moderately positive results in moderate shading scenarios. In contrast, high levels of shading, with a 60–70% decrease in PAR, are linked to substantial yield declines (e.g., leafy vegetables and horticultural crops facing simulated 70–90% radiation reduction scenarios).

LER is not consistently documented in experimental research on agrivoltaics. Our dataset contains only six studies that offer a specific numerical value for LER; in each instance, LER is greater than 1, suggesting a net advantage in land use relative to individual photovoltaics and open-field farming.

The analysed literature does not indicate the existence of a universally best photovoltaic technology for agrivoltaic applications but demonstrates that agrivoltaic systems rely on different solutions, each characterised by specific trade-offs between energy and agricultural performance. Opaque crystalline silicon (c-Si) modules, both monofacial and bifacial, generally exhibit higher electrical efficiencies, whereas semi-transparent solutions, such as thin-film technologies (e.g., amorphous silicon and CdTe), are typically associated with lower electrical efficiency. Nevertheless, the optimal agrivoltaic solution is based on a compromise between energy production and agricultural performance: opaque c-Si systems are suitable where partial shading is acceptable, while semi-transparent technologies allow a more controlled transmission of solar radiation to the crops.

Figure 5 shows the reduction in PAR compared to the control case (C) in full sunlight on the x-axis and the percentage change in crop yield on the y-axis observed in experimental studies.

Figure 5.

Relationship between PAR reduction (relative to the full-sun control) and crop yield change (%) reported in experimental agrivoltaic studies.

The figure clearly shows that crop yield response is extremely variable; in fact, even with the same PAR reduction values, very different results can be observed. Traditional systems, generally made of monocrystalline or polycrystalline silicon, and bifacial systems can cause significant shading, often exceeding 50%, drastically reducing the amount of PAR reaching crops. In these contexts, crops that are highly dependent on radiation—such as cereals like rice and wheat—show significant drops in production, even exceeding 30–40%, especially in northern Europe (Germany and Belgium) and northern Japan. Conversely, some broad-leaved horticultural species, such as lettuce, spinach and chicory, fruit tree species (apple, pear, kiwi), and some aromatic plants, under conditions of high thermal stress, especially in Mediterranean and semi-arid climates, benefit most from these levels of shading, resulting, in some cases, in better quality and yield. However, semi-transparent and transparent modules, that represent an evolution in this field, allow selective transmission of radiation and optimise the quality of the radiation reaching crops by filtering out NIR and UV, which are often harmful to plants. Studies show that, in addition to maintaining almost unchanged productivity levels for most crops, these technologies can bring benefits, especially in terms of quality, such as improved phenolic compounds in strawberries, increased protein content in spinach and basil, and better colour and sugar accumulation in fruits. In some cases, although this type of panel leads to a decrease in yield, it reduces sunburn and preserves the integrity of the fruit and, therefore, its commercial value.

CPV systems have more limited experimental results, representing a promising but still little-explored avenue. Future research should prioritise experimental campaigns to jointly quantify not only energy output but also crop response. However, so far, preliminary results seem to show the same trend as semi-transparent and transparent systems.

Nevertheless, crop responses are not dependent only on light availability: the results clearly confirm that agronomic performance also strongly depends on crop type, geographical context, and local microclimatic conditions, further confirming the intrinsic complexity of agrivoltaic systems, where energy production and crop yield are governed by multiple interacting factors. The technology used and the height and the distance between the rows of modules influence the microclimatic parameters and the PAR reaching the crops.

In fact, in arid/semi-arid and Mediterranean climates with warm periods, microclimatic advantages (reduced canopy/soil temperature, increased soil moisture, and lower evaporative demand) can help mitigate light limitations, whereas in seasons/latitudes with restricted light and for shade-sensitive crops (especially certain cereals/grains), yield reductions occur more frequently as shading increases. This suggests that some of the variability and seemingly contradictory results between “similar” photovoltaic systems can be explained by climate variability and the fact that agronomic management is tailored to the microclimate. In general, almost all studies show a reduction in air temperature ranging from −0.5 °C to −3 °C, while soil temperature can be reduced by up to 4 °C. These dynamics, widely demonstrated in Mediterranean, temperate, and tropical contexts, help to mitigate crop heat stress, reduce evapotranspiration and, therefore, improve water use efficiency, a fundamental aspect of the WFE nexus.

In terms of energy, most of the studies analysed show an LER greater than one and, in some cases, greater than 3, thus demonstrating that the combined agricultural and energy yield exceeds that of the two activities carried out separately.

This review is limited by the high heterogeneity of results among the different scientific articles analysed. Many articles do not report key variables in a similar way, limiting the quantitative aggregation of data and preventing a formal meta-analysis. Finally, no formal assessment of bias risk or study quality was performed, as basic quality indicators were not reported systematically across all studies, limiting the strength of causal claims.

5. Conclusions

This review, based on 82 experimental studies conducted in over 20 countries over the last 15 years, confirms that agrivoltaics can be an effective solution for integrating agricultural and energy production and mitigating land use conflicts, but at the same time highlights the strong dependence of results on the combination of crop, climate, and technology.

The review highlights how current experimental research still focuses mainly on opaque agrivoltaic configurations based on crystalline silicon modules, while other approaches, such as CPV or OPV, have been little tested but represent great potential, despite economic limitations. Conversely, perovskite-based solar cells have not been addressed in this systematic review because experimental agrivoltaic applications of this technology remain limited in the literature analysed.

Despite the wide variability of results, it was possible to identify a recurring pattern, synthesised into a simple decision-support framework linking crop categories, climate context, and PV-technology families (Table 3).

Table 3.

Recurring patterns across crops, climate, and PV technologies.

- -

- Leafy crops (lettuce, spinach, chicory, Swiss chard, cabbage, leafy brassicas) generally show higher tolerance to moderate shading and, under hot conditions, can benefit from the associated microclimate buffering. They can perform well under conventional modules in Mediterranean settings, whereas in warmer climates they often favour semi-transparent solutions to better preserve PAR availability.

- -

- Fruit crops (fruit trees (apple, pear, peach, kiwi, grapevine)), on the other hand, prefer bifacial and semi-transparent systems that optimise the microclimate and reduce sunburn without compromising yield.

- -

- Fruit vegetables (tomatoes, peppers, aubergines, cucumbers, courgettes), being highly dependent on light, prefer semi-transparent and CPV modules in dry and sunny climates, which optimise light transmission.

- -

- Cereals C3 (wheat, barley, rice), which are the crops most sensitive to PAR reduction, require shading of no more than 20–30%.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/en19020539/s1. PRISMA 2020 Main Checklist; PRISMA 2020 for Abstracts Checklist.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, C.R. and O.D.M.; methodology, C.R. and O.D.M.; software, C.R. and O.D.M.; validation, C.R. and O.D.M.; formal analysis, C.R. and O.D.M.; investigation, C.R. and O.D.M.; resources, C.R. and O.D.M.; data curation, C.R. and O.D.M.; writing—original draft preparation, C.R. and O.D.M.; writing—review and editing, C.R. and O.D.M.; visualisation, C.R. and O.D.M.; supervision, C.R.; project administration, C.R.; funding acquisition, C.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analysed in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| a-Si | Amorphous silicon |

| Bi-Si | Bifacial |

| C | Control |

| c-Si | Monocrystalline photovoltaic |

| CdTe | Cadmium telluride |

| CPV | Concentrated photovoltaic system |

| DF | Dicroic film |

| ET | Evapotranspiration |

| HD | Head weight |

| HWS | Hight water savings |

| HWL | High water dispersion |

| I | Increase |

| NV | No Variation |

| NR | Net radiation |

| OPS-CB | Opaque plastic sheets (checkerboard pattern) |

| OPV | Organic photovoltaics |

| Poly-si | Polycrystalline photovoltaic |

| PVc | Coloured photovoltaics |

| PVs | Opaque photovoltaics |

| RH | Relative Humidity |

| SS | Spectral splitting |

| SPV | Semi-transparent photovoltaic |

| TPV | Transparent photovoltaic |

| VWC | Volumetric water |

| D | Decrease |

Appendix A

Table A1.

Summary of experimental agrivoltaic studies.

Table A1.

Summary of experimental agrivoltaic studies.

| Crop | Tec | Light vs. Control | Parameter | Change vs. Control | Location and Year | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wheat | c-Si | 45% PAR | Yield | −19% | Montpellier, France (2010) | [30] |

| Biomass | −29% | |||||

| 70% PAR | Yield | −8% | ||||

| Biomass | −11% | |||||

| Lettuce | c-Si | 45% PAR | Yield | −16% | Montpellier, France (2011) | [31,32] |

| 70% PAR | −5% | |||||

| Cucumber | 45% PAR | −23% | ||||

| 70% PAR | −12% | |||||

| Kale | c-Si | 45% PAR | Biomass | NV | California, USA (2021) | [33] |

| 7% PAR | D | |||||

| Swiss chard | 85% PAR | NV | ||||

| 55–62% PAR | D | |||||

| Peppers | 85% PAR | Fruit weight | I | |||

| Tomatoes | 55% PAR | NV | ||||

| 7% PAR | D. | |||||

| Chicory | c-Si | 6% of full sunlight | Biomass | +69% (HWS) and +26% (HWL) | Lecce, Italy (2021) | [37] |

| Chlorophyll | −20/30% | |||||

| ET | −45% | |||||

| Native flora | c-Si | - | Soil temperature | D | Chisago City, MN, USA (2019) | [38] |

| Soil moisture | I | |||||

| Soil nutrients | I | |||||

| Thyme | c-Si | 56% PAR | Height | +8.6% | Kourtesi, Greece (2024) | [39] |

| Fresh weight | +6% | |||||

| Oregano | Height | +9% | ||||

| Fresh weight | +32% | |||||

| Tea | Height | −5% | ||||

| Fresh weight | +47% | |||||

| LN | NV | |||||

| Thyme, Oregano, Tea | ET | −29% | ||||

| Rice | c-Si | 30–40% shading | Yield | −4 to −9% | Kakegawa (Shizuoka) and Katori (Chiba), Japan (2014–2019) | [40] |

| Plant height | −5 to −10% | |||||

| Plant number | −2 to −8% | |||||

| Rice | c-Si | 32% of shading | Plant height | −4.8% | Yamagata Prefecture, Tohoku Region, Japan (2021–2023) | [41] |

| Tiller number | −10.8% | |||||

| Panicle number | −11.2% | |||||

| Yield | −13.4% | |||||

| Protein content | +6.4% | |||||

| c-Si | 21–30% light reduction | Plant height | +7–10% | Chikusei (Ibaraki, Japan) (2018–2023) | [44] | |

| Panicle density | −10–20% | |||||

| Filled grains | −7–20% | |||||

| Protein content | +11–16% | |||||

| Amylose content | +4–6% | |||||

| Cabbage | c-Si | - | Yield | −57 to −9% | Jiangshan, China (2022) | [45] |

| Forage grasses | c-Si | 38% light reduction | ET | −1.3% | Colorado, USA (2023) | [46] |

| Tomato | c-Si | - | RH | −1.09–+4.75% | Corvallis, USA (2021) | [47] |

| Yield | −39–68% | |||||

| Celery | c-Si | - | Yield | −40% | France (2017) | [48] |

| Turnip | −40% | |||||

| Potato | −5 to −25% | |||||

| Wheat | −5% to −25% | |||||

| Vite | a-Si | 95% Light | RH | +6.1% | Puglia, Italy (2023) | [50,51] |