Abstract

Artificial intelligence (AI) has become integral to predictive maintenance (PdM) in renewable energy systems (RES), enabling the detection of faults, forecasting of degradation, and optimization of performance. However, existing reviews are fragmented, focusing either on specific energy domains or algorithmic families without a unified framework that connects AI methods to real-world deployment. This paper presents a novel, cross-domain synthesis for solar, wind, hydro, and hybrid systems. Its originality lies in a dual-axis classification framework that maps AI models to their functional roles while accounting for the data realities of different energy infrastructures. Unlike prior studies, this review integrates data characteristics into the comparative analysis, revealing how data constraints shape model selection, scalability, and reliability. By bridging methodological rigor with operational feasibility, this paper establishes a foundation for adaptive, transparent, and scalable AI integration in RES. The findings offer actionable insights for researchers, engineers, and policymakers seeking to advance intelligent asset management in the context of global energy transition.

1. Introduction

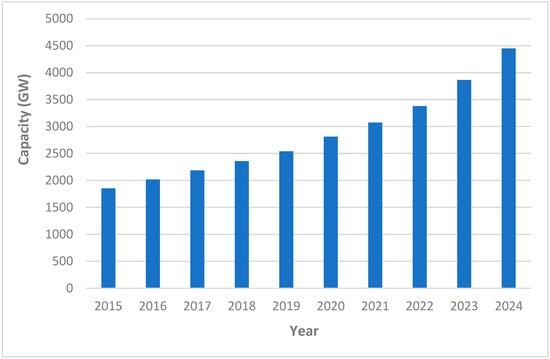

The global energy landscape is undergoing a significant transformation driven by the urgent need to address climate change, ensure energy security, and promote sustainable development. This shift has spurred unprecedented deployment of renewable energy (RE) technologies, with solar photovoltaic (PV), wind turbines (WT), hydropower, and hybrid systems moving from marginal to central roles in national energy strategies. The International Energy Agency (IEA) and the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA) report continued record-breaking annual growth in renewable capacity [1,2] as shown in Figure 1. However, the operational paradigm of RES introduces unique challenges that threaten reliability, economic viability, and long-term sustainability. Unlike conventional dispatchable power plants, RE assets are subject to inherent intermittency driven by stochastic environmental conditions [3,4]. Furthermore, these systems often operate in harsh, inaccessible, or remote environments, accelerating component degradation and increasing the likelihood of mechanical, electrical, and structural failures.

Figure 1.

Global installed renewable energy capacity.

The financial model of RES is exceptionally sensitive to unplanned downtime and suboptimal performance [5,6]. Every kilowatt-hour of lost generation directly impacts the levelized cost of energy (LCOE) and returns on investment. Consequently, the traditional maintenance strategies of reactive and preventive maintenance [7] are proving inadequate. They lead to either high costs from catastrophic failures or unnecessary expenditures from replacing components that still have significant useful life.

In this context, Predictive Maintenance (PdM) has emerged as a cornerstone strategy for intelligent asset management [8]. Its objective is to forecast failure onset and estimate the remaining useful life (RUL) of critical components, enabling just-in-time maintenance scheduling to maximize asset availability and longevity while minimizing operational expenditures [9]. The successful implementation of PdM, however, hinges on the ability to process and interpret vast, multi-modal streams of operational data to discern subtle patterns indicative of incipient faults.

Artificial Intelligence (AI), particularly machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL), offers a transformative, data-driven toolkit for learning complex, non-linear relationships from historical and real-time data that are often intractable for traditional physical or statistical models. Techniques, ranging from classical supervised learning to advanced deep neural networks, process high-dimensional sensor data, adapt to evolving system behavior, and operate effectively under uncertainty [10,11,12]. These capabilities are fundamental for intelligent fault detection and diagnosis (FDD), accurate RUL estimation, maintenance schedule optimization, and energy dispatch [13].

Despite these advancements, literature on AI-based PdM in RES remains fragmented [14]. Several prior reviews have examined AI applications in PdM for RES, yet have largely adopted one of two approaches: Domain-specific syntheses [15,16,17,18] or Algorithm-centric surveys that catalog ML or DL techniques for PdM without systematically linking them to the data realities, functional roles, or deployment constraints of real-world RES. For instance, the research in [8,16,19] focused on ML and DL for fault detection and diagnosis in PV systems. These provided detailed insights into component-level issues but rarely extended to cross-domain comparisons or explicit consideration of deployment maturity and technology readiness levels (TRL). Similarly, the wind-energy-focused surveys in [17,20,21] highlight condition monitoring, fault diagnosis, and PdM using AI methodologies, often prioritizing algorithmic performance over data heterogeneity, privacy constraints in distributed assets, or systematic TRL assessments. Broader reviews in [22,23,24] address PdM across multiple renewable sources, including solar, wind, and hydropower. However, they typically remain domain-specific or algorithm-centric, with minimal integration of data-centric perspectives that account for varying sensor density, label scarcity, and privacy needs across diverse renewable infrastructures. The absence of a data-centric perspective in [25,26] limits their applicability to operational environments and impedes the development of scalable AI solutions. The lack of comparative analysis across energy domains is further highlighted in [27,28,29]. While these studies provide valuable foundations, critical gaps remain: Cross-domain analysis is absent; a data-centric perspective is seldom incorporated; assessments of deployment maturity are rare; and the scope is typically confined to PdM with limited integration of performance optimization tasks such as forecasting and dispatch.

In contrast, the present review offers a novel cross-domain synthesis that encompasses solar, wind, hydro, and hybrid systems. Its originality lies in introducing a dual-axis framework that explicitly maps AI paradigms to both functional roles (diagnostic, predictive, prescriptive) and data readiness constraints. By centering data characteristics as a core determinant of model selection, scalability, and reliability, this work bridges the persistent gap between advanced algorithmic proposals and real-world operational feasibility, while providing explicit technology readiness assessments and actionable insights for stakeholders navigating the global energy transition. This review addresses the highlighted gaps through three key contributions:

- (1)

- A novel dual-axis framework that classifies AI techniques by both algorithmic paradigm and functional role (diagnostic, predictive, prescriptive), enabling a structured comparison across energy domains.

- (2)

- A data-centric synthesis that explicitly incorporates data readiness into the evaluation of AI models, aligning methodological rigor with deployment realities.

- (3)

- An integrated analysis of existing literature to identify research gaps, assess deployment maturity, and critique methodological limitations. By bridging domain-specific, algorithmic, and data-centric perspectives, this work offers a unified, pragmatic foundation for scalable, transparent, and trustworthy AI integration in renewable energy systems.

2. Methodology and Literature Review

2.1. Methodology

This review adopts a critical synthesis methodology with systematic elements, including structured searches, multi-stage screening, and quality appraisal. It aims to provide a reproducible, domain-crossing analysis of AI for PdM and performance optimization in RES. A structured search was conducted across five major academic databases: IEEE Xplore, Scopus, Web of Science, ScienceDirect, and SpringerLink. Searches were executed across all databases between 1 September 2025, and 2 December 2025, and an updated search incorporating the expanded query was performed on 12 January 2026. Duplicates were removed using a two-step process: (1) automated deduplication via EndNote 21, (2) manual verification to resolve near-duplicates (e.g., conference vs. journal versions, preprints vs. final publications) and ensure only true duplicates were excluded.

The following Boolean query was adapted per database syntax: IEEE Xplore- (“predictive maintenance” OR “condition monitoring” OR “prescriptive maintenance” OR optimization OR dispatch OR “energy management” OR “optimal control” OR “reinforcement learning” OR “model predictive control” OR “multi-agent” OR forecasting OR “grid integration”) AND (“artificial intelligence” OR “machine learning” OR “deep learning”) AND (“renewable energy” OR “solar PV” OR “wind turbine” OR hydropower OR “smart grid” OR “cyber-physical systems”), Scopus- TITLE-ABS-KEY ((“predictive maintenance” OR “condition monitoring” OR “prescriptive maintenance” OR optimization OR dispatch OR “energy management” OR “optimal control” OR “reinforcement learning” OR “model predictive control” OR “multi-agent” OR forecasting OR “grid integration”) AND (“artificial intelligence” OR “machine learning” OR “deep learning”) AND (“renewable energy” OR “solar pv” OR “wind turbine” OR hydropower OR “smart grid” OR “cyber-physical systems”)), Web of Science- TS = ((“predictive maintenance” OR “condition monitoring” OR “prescriptive maintenance” OR optimization OR dispatch OR “energy management” OR “optimal control” OR “reinforcement learning” OR MPC OR “model predictive control” OR “multi-agent” OR forecasting OR “grid integration”) AND (“artificial intelligence” OR “machine learning” OR “deep learning”) AND (“renewable energy” OR “solar PV” OR “wind turbine” OR hydropower OR “smart grid” OR “cyber-physical systems”)), ScienceDirect (“predictive maintenance” OR “condition monitoring” OR “prescriptive maintenance” OR optimization OR dispatch OR “energy management” OR “optimal control” OR “reinforcement learning” OR “MPC” OR “model predictive control” OR “multi-agent” OR forecasting OR “grid integration”) AND (“artificial intelligence” OR “machine learning” OR “deep learning”) AND (“renewable energy” OR “solar” OR “wind” OR “hydropower” OR “smart grid”), SpringerLink- (“predictive maintenance” OR “condition monitoring” OR “prescriptive maintenance” OR optimization OR dispatch OR “energy management” OR “optimal control” OR “reinforcement learning” OR “MPC” OR “model predictive control” OR “multi-agent” OR forecasting OR “grid integration”) AND (“artificial intelligence” OR “machine learning” OR “deep learning”) AND (“renewable energy” OR “solar” OR “wind” OR “hydropower” OR “smart grid”)

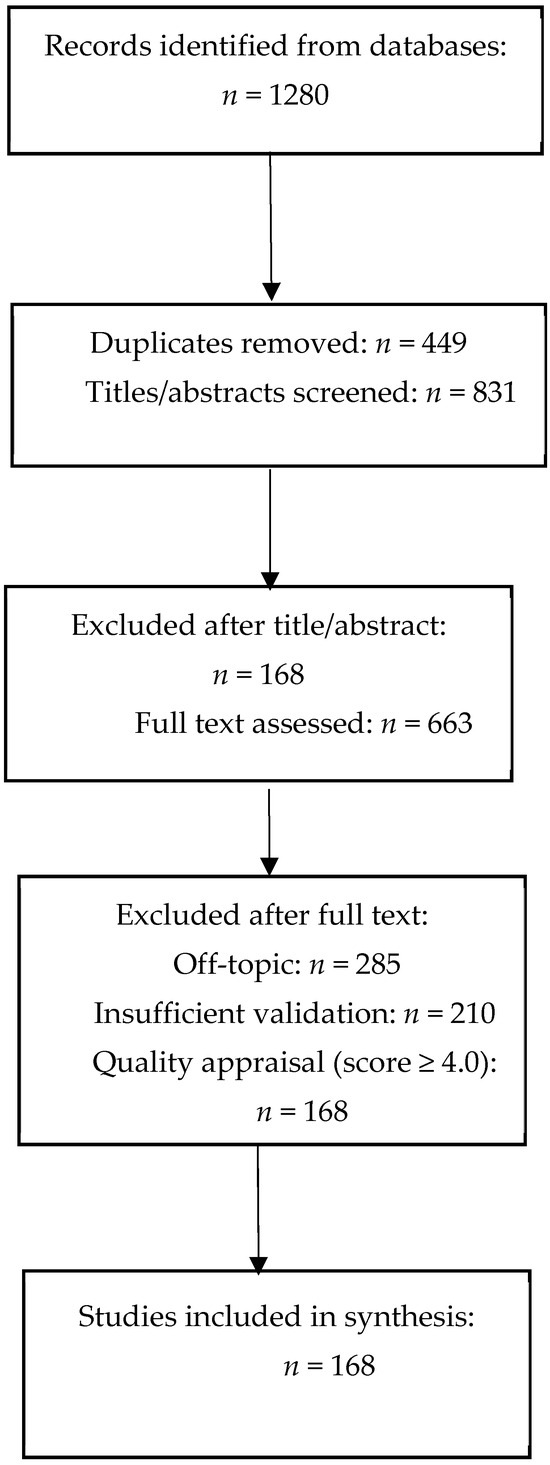

The initial search produced 1280 articles. A multi-stage screening process refined the literature set as detailed in Table 1 and the selection flow is shown in Figure 2.

Table 1.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria for Literature Search.

Figure 2.

Selection Flow Diagram.

A rigorous critical appraisal process was implemented using a custom checklist adapted from the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) [30]. Each study was scored on a five-point scale across five weighted criteria, shown in Table 2. The composite quality score was calculated as shown in Equation (1), where each criterion is weighted according to its importance and scores are averaged.

where refers to the scores for problem formulation, technical depth, validation strategy, relevance to RES domains and reproducibility, respectively.

Table 2.

Quality appraisal criteria and scoring guidelines (adapted from CASP).

This rubric translates the five weighted criteria used for study quality assessment into clear, actionable benchmarks across three defined performance levels: Poor (1), Adequate (3), and Excellent (5). It provides explicit descriptors for each level, transforming subjective judgment into a structured, transparent, and reproducible process. For instance, it specifies that an Adequate (3) validation strategy might involve a single metric, while an Excellent (5) strategy requires rigorous cross-validation and benchmark comparisons. Only studies achieving a final score ≥ 4.0 were included in the final synthesis. For example, ref. [31] scored 4.8/5 and was included due to an explicit problem statement, detailed hybrid CNN-ML architecture, and rigorous validation. After full-text assessment (n = 663), 495 studies were excluded (off-topic n = 285; insufficient validation n = 210). The remaining 168 studies all achieved a composite quality score ≥ 4.0 (median 4.4, range 4.0–5.0). Lower scores (4.0–4.2) were most commonly due to limited technical depth of the AI methodology (e.g., missing architectural details or hyperparameters) or incomplete reproducibility information (e.g., lack of dataset description or code availability). No studies were excluded solely based on the quality threshold. Screening and full-text appraisal were performed independently by two reviewers (O.A. and E.M.M.). Inter-rater agreement was substantial for both stages: Cohen’s kappa κ = 0.82 (title/abstract screening) and κ = 0.78 (full-text eligibility). Disagreements were resolved through discussion with a third reviewer (J.L.M.).

2.2. Literature Review

The application of AI for PdM in RES has evolved from initial algorithmic experiments to deployment-focused solutions. Early work proved the value of classical ML. For instance, Kusiak and Verma [32] used decision trees and Support Vector Machines (SVMs) on wind turbine Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition (SCADA) data to accurately diagnose bearing and gearbox faults. Similarly, Zhang et al. [33] demonstrated robust electrical anomaly detection in PV arrays using a Least Squares SVM within a Bayesian framework. Suliman et al. [34] extended this approach by optimizing SVM performance using swarm intelligence for fault detection in PV systems. Similarly, Kumaradurai in [35] reviewed various types of faults detected using different ML algorithms in PV systems. These studies proved that data-driven models could surpass traditional threshold-based methods. However, a significant gap identified was their heavy reliance on extensive feature engineering and domain expertise for manual feature selection, limiting their adaptability to new systems or evolving fault modes [36]. Furthermore, these models often struggled with the high-dimensional and temporal nature of operational data.

The advent of DL marked a paradigm shift, enabling end-to-end learning from raw or minimally processed data. Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) have shown remarkable success in image-based diagnostics. The research in [37] demonstrated a DL approach for detecting defects in WT blades from images while [31] focused on using a hybrid CNN model to diagnose faults in solar panels using infrared (IR) thermography images. In [38], the study used a Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) variant to predict the RUL of WT gearbox bearings. It highlighted the strength of LSTM’s in handling sequential time series data which is critical for representing the gradual degradation process. More recently in [39], the study proposed a model that combined the temporal sensitivity of LSTM with a Tree Seed Algorithm (TSA) for the purpose of optimizing network parameters to predict the RUL of WT main bearings. Despite their superior performance, a critical gap emerged from these studies: these DL models are “data-hungry,” requiring vast amounts of labeled fault data for training, which is often scarce for critical but rare failure events [40].

To address the limitations of single-model approaches, research has progressed towards hybrid and ensemble models. Kuyumaniet et al. in [41] proposed a novel forecasting model that aggregated CNN and LSTM for detecting and forecasting harmonics in a power system while in [42], the authors developed a CNN-LSTM-based wind motor fault detection model for different categories of faults in a WT system. In solar energy, ref. [43] employed an ensemble of gradient boosting models for forecasting PV power output, demonstrating improved robustness to weather variability. While these hybrid approaches enhance performance, they introduce gaps related to computational complexity and integration challenges, making real-time deployment on edge devices difficult.

Recent years have witnessed the exploration of emerging AI paradigms tailored to the distributed and privacy-sensitive nature of modern RES. Federated learning (FL) has been proposed to enable collaborative model training across geographically dispersed assets like wind farms or residential PV systems without sharing raw data, thus addressing data privacy and bandwidth constraints [44,45]. However, a key research gap is the performance degradation of FL models due to non-independent and identically distributed (Non-IID) data across clients and the communication overhead involved [46]. Simultaneously, Explainable AI (XAI) techniques, such as SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) and Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations (LIME) are being integrated to elucidate model decisions in RES [47,48]. The gap here is the computational cost of these post hoc explanations, which often makes them unsuitable for real-time applications, and a lack of standardized metrics for evaluating explanation quality in an engineering context [49].

Beyond fault detection, AI has been extensively applied to performance optimization, particularly forecasting and dispatch. The work performed in [50] presented a review of DL irradiance forecasting models, showing that hybrid DL models are preferred for enhanced performance in solar systems. For energy dispatch, Reinforcement Learning (RL) has shown promise as seen in [51] where Deep Q-Network (DQN) was used to optimize power dispatch in a microgrid, reducing operational costs. However, the primary gap with RL is that, as with most algorithms trained and validated in simplified simulations, it inadequately captures the full stochasticity and complexity of real-world grid operations [52].

The application of AI varies significantly across energy domains, revealing domain-specific gaps. In data-rich wind and solar domains, research is mature, but challenges like model adaptability to new sites and component-level RUL estimation persist [53,54]. In contrast, hydropower systems suffer from a critical data scarcity gap. In [55], Zhang et al. used Variational Autoencoders (VAEs) for anomaly detection in turbines with limited labeled data, but the lack of fault examples severely constrains the development of supervised diagnostic models. For hybrid microgrids and CPES, the research focus has shifted to multi-agent systems (MES) [56] and coordinated control where Multi-Agent RL (MARL) framework is implemented for decentralized energy management as seen in [57].

While the volume of research is impressive, several overarching gaps remain unaddressed. First, there is a pronounced fragmentation and lack of a unified framework. Most reviews and studies are either domain-specific or algorithm-centric, preventing a holistic understanding of cross-domain AI applicability. Second, a data-centric perspective is often missing such that the influence of data characteristics like sampling frequency, label availability, and privacy constraints on model selection and scalability is frequently discussed in isolation, if at all. This leads to a misalignment between sophisticated AI models and the practical data realities of operational environments. Lastly, there is insufficient analysis of functional mapping and deployment maturity. While many papers propose novel algorithms, few provide a structured analysis linking AI paradigms to their specific functional roles such as fault detection or prescriptive control within a PdM workflow or a critical assessment of their TRL for industrial use.

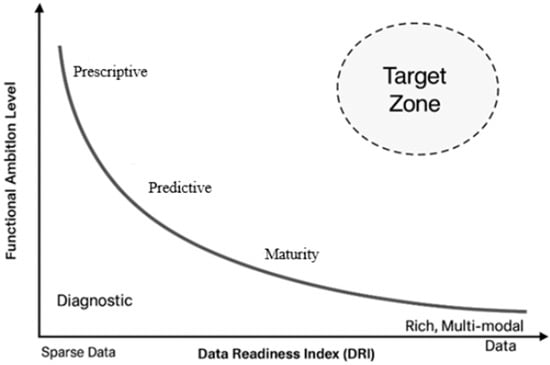

3. Dual-Axis Framework

An analysis of 168 studies reveals a tension where advanced algorithms often surpass practical data limits. We developed a dual-axis framework using the Data Readiness Index (DRI)—a composite metric that quantifies the availability and quality of data in a given renewable energy system—and Functional Ambition Level (FAL)—an ordinal scale that categorizes the operational role and decision autonomy of the AI system (diagnostic, predictive, or prescriptive)—to evaluate AI approaches, as shown in Figure 3. The target zone balances data availability and operational goals for optimal AI deployment, with a growth path toward this balance.

Figure 3.

Proposed dual-axis framework mapping Data Readiness Index (DRI) against Functional Ambition Level (FAL).

3.1. Data Readiness Index (DRI)

The DRI axis quantifies data availability from sparse to rich environments as a composite metric reflecting key data characteristics. For a given system or dataset, DRI is conceptualized as a function of:

- Sampling frequency (): Measured in Hertz (Hz), distinguishing between low-frequency supervisory data (e.g., Hz for some hydropower SCADA systems) and high-frequency condition monitoring data (e.g., kHz for vibration analysis in wind turbine gearboxes).

- Number of verified, labeled fault events (): The total count of annotated failure instances available for model training. This parameter directly constrains supervised learning feasibility, ranging from sparse scenarios (e.g., for critical hydropower failures) to abundant ones (e.g., for common inverter faults in solar PV systems).

- Modality index (): A categorical representation of data source diversity and complexity, scaled from for homogeneous time-series (e.g., electrical measurements alone) to for highly heterogeneous data fusion (e.g., combining SCADA, vibration, infrared imagery, acoustic emissions, and maintenance logs in cyber-physical energy systems).

- Data quality score (): A composite measure of signal-to-noise ratio, missing data proportion, sensor calibration status, and temporal consistency.

Each component is normalized to a 0–1 scale based on domain-specific benchmarks. The DRI is then calculated as the simple equal-weight average of the four normalized values. For example, an onshore wind farm with high-frequency SCADA (0.9), more than 1000 labeled faults (0.95), multi-modal inputs (0.8), and excellent data quality (0.9) yields DRI = (0.9 + 0.95 + 0.8 + 0.9)/4 ≈ 0.89 (data-rich). In contrast, a run-of-river hydropower system with low-frequency SCADA (0.1), fewer than 50 labeled faults (0.1), homogeneous data (0.2), and moderate quality (0.6) yields DRI = (0.1 + 0.1 + 0.2 + 0.6)/4 = 0.25 (data-sparse). This aggregate score guides the selection of appropriate AI paradigms in the dual-axis framework.

3.2. Functional Ambition Level (FAL)

The FAL axis categorizes the operational role and value proposition of the AI system using an ordinal scale defined by the input-output relationship and decision autonomy:

- FAL 1 (Diagnostic): The AI model identifies current or past system states. This is typically a classification or anomaly detection task, formally represented as , where is a vector of sensor measurements at time and is a fault class or an anomaly score.

- FAL 2 (Predictive): The AI model forecasts future system states. This is a sequence forecasting or regression task, formalized as , where is a historical sequence of observations and is the predicted sequence over a future horizon . RUL estimation is a key example in which the output is a scalar RUL value.

- FAL 3 (Prescriptive): recommends or autonomously executes optimal actions as a sequential decision-making problem where the AI learns a policy that maps system state to an action , i.e., . The policy is learned to maximize a cumulative reward function. , which encodes operational objectives such as cost minimization and reliability maximization.

To illustrate, consider an onshore wind farm gearbox monitoring system that detects abnormal vibrations (FAL 1—diagnostic), estimates remaining useful life with a 3-month horizon (FAL 2—predictive), and recommends inspection timing or derating actions (FAL 3—prescriptive). The overall FAL is assigned as the highest level implemented: in this case FAL 3 (Prescriptive), guiding selection toward reinforcement learning (RL) or policy-based models in the dual-axis framework.

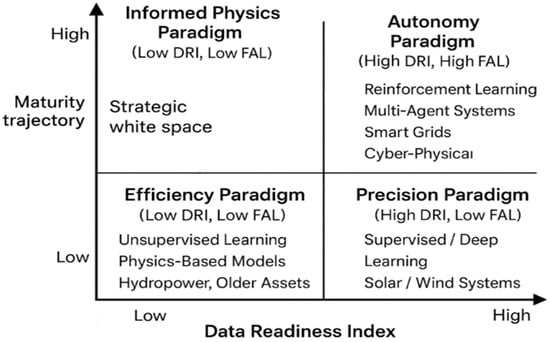

The convergence of DRI and FAL creates a strategic landscape defined by the formal mapping

where is the set of suitable AI paradigms, yielding four distinct strategic paradigms shown in Figure 4. Efficiency Paradigm (Low DRI, Low FAL) focuses on robustness and efficiency using unsupervised learning, transfer learning, and few-shot learning. The Precision Paradigm (High DRI, Low FAL) maximizes performance using supervised learning, deep learning, and ensemble techniques, Autonomy Paradigm (High DRI, High FAL) emphasizes autonomous optimization using reinforcement learning and multi-agent systems, and the Informed Physics Paradigm (Low DRI, High FAL) employs Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINNs) and hybrid models that incorporate domain knowledge to compensate for data scarcity.

Figure 4.

Categorization of AI operational paradigms.

This framework provides a diagnostic lens to critique the current state of the art and a strategic compass for future investment. It explains why a one-size-fits-all AI approach is destined to fail and why many advanced algorithms struggle to transition from research to practice.

4. AI Techniques for Predictive Maintenance in Renewable Energy Systems

PdM has emerged as a cornerstone in the operation and life-cycle management of RES, enabling the transition from reactive to proactive asset management. By forecasting potential failures and optimizing maintenance schedules, PdM minimizes downtime, extends asset lifespan, and improves operational efficiency, constituting a cornerstone strategy for modern asset management [58,59]. Figure 5 presents a synthesis of AI methodologies applied to PdM across solar, wind, hydro, and hybrid renewable systems.

Figure 5.

AI methodologies in PdM for RES.

4.1. Supervised Learning Techniques

Supervised learning constitutes a foundational shift in PdM for RES. Formally, supervised learning aims to learn a function that maps an input feature vector such as sensor readings to a corresponding output like a fault class or RUL value based on a labeled training dataset which constitutes the learner’s input in the standard model of supervised learning [60,61]. This is represented in (3) and (4).

where represents a feature vector of sensor readings, and is a corresponding label denoting a specific fault class or a continuous value for RUL. The efficacy of these models is contingent upon the quality, volume, and feature representation of the training data, which often comprises high-dimensional time-series from SCADA systems, vibration sensors, and electrical measurements. As shown in Figure 6, the supervised learning techniques for PdM in RES comprise SVM, Random Forest (RF) models, and Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost).

Figure 6.

Supervised learning techniques for PdM in RES.

SVMs have demonstrated robust performance in diagnosing complex, nonlinear faults. For instance, in wind energy systems, they have been successfully applied to classify bearing and gearbox failures using SCADA data, showcasing their capability to handle non-linear relationships in high-dimensional operational data as seen in [62]. Similarly, ref. [32] applied an SVM with a radial basis function (RBF) kernel to diagnose drivetrain failures in wind turbines using SCADA data, highlighting its capability to handle non-linear relationships and demonstrating superior performance over linear kernels. This approach is recognized as a validated method for wind turbine condition monitoring [27]. However, their diagnostic precision is constrained by a sensitivity to kernel selection and hyperparameter tuning. Furthermore, as noted in [63], SVMs suffer from limited scalability and high computational cost when applied to large-scale SCADA datasets, making them less suitable for real-time applications on massive fleets of turbines [64,65].

Random Forest (RF) models have proven highly valuable for fault diagnosis and feature importance ranking. The study by Bangalore et al. in [66] demonstrated the efficacy of RF in diagnosing incipient faults in wind turbines, leveraging its inherent robustness to noise and missing data in SCADA systems. Their work specifically utilized the model’s interpretability, through Gini importance ranking, to identify the most critical parameters leading to a fault. However, the performance of RF can deteriorate significantly under conditions of severe class imbalance, which is a common challenge in industrial deployments where fault events are rare. This is highlighted in [67] which showed that for high-dimensional data with severe imbalance, standard RF models become biased towards the majority class, necessitating advanced sampling or cost-sensitive learning techniques.

Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) has emerged as a high-performance alternative, often surpassing other tree-based methods in accuracy and computational efficiency. In the context of RES, ref. [68] demonstrated that XGBoost outperforms SVM and RF in accuracy and computational efficiency by effectively modeling complex interactions among heterogeneous sensor inputs. Nonetheless, as critically examined in [69], XGBoost’s performance is highly sensitive to hyperparameter tuning, and its greedy learning approach can lead to overfitting on noisy or unrepresentative training datasets unless carefully regularized.

Although supervised models deliver impressive diagnostic accuracy when comprehensive labeled fault data are available, their fundamental reliance on annotated datasets limits their adaptability to early-stage or rare-fault scenarios. This constraint is a significant bottleneck, as compiling sufficient labeled data for every potential failure mode is often economically and practically infeasible [20]. This limitation underscores the critical importance of exploring transfer learning and semi-supervised learning paradigms that can leverage knowledge across domains or augment model training with readily available unlabeled data [70]. Finally, the absence of standardized, open datasets in renewable energy PdM continues to be a major impediment, hindering robust model benchmarking, reproducibility, and the acceleration of research across the community [71].

4.2. Unsupervised Learning and Clustering

In many renewable energy contexts, labeled fault data are scarce or incomplete, making unsupervised learning indispensable for identifying latent patterns, operational anomalies, and degradation signatures. Techniques such as K-means clustering, principal component analysis (PCA), and autoencoders have been widely employed to learn the normal behavior of assets and detect deviations indicative of faults [72,73]. K-means has been effective for grouping operational states in PV arrays and wind turbines, but its assumption of spherical cluster geometry and equal variance limits its suitability for systems exhibiting nonlinear dynamics [74]. PCA, frequently used for dimensionality reduction and noise filtering, simplifies fault detection by isolating the most significant variance components, yet it fails to capture complex nonlinear relationships that characterize renewable energy data [75,76].

Autoencoders, particularly denoising and variational variants, have proven highly effective in reconstructing normal operational patterns and identifying anomalous deviations through reconstruction errors [77,78]. Despite their advantages, these models often suffer from limited interpretability and require careful architectural design to prevent underfitting or overgeneralization.

The strength of unsupervised learning lies in its applicability to domains with limited failure records, such as hydropower and microgrids. However, the lack of transparency and explainability remains a major limitation, as these models typically operate as black “boxes” [79]. A promising research direction lies in integrating domain knowledge into the model structure through physics-informed or constraint-based learning frameworks, thereby enhancing interpretability and ensuring that AI models remain consistent with known physical laws.

4.3. Deep Learning Architecture

Deep learning has transformed PdM by enabling the modeling of high-dimensional and nonlinear relationships inherent in RES [12,80]. Architectures such as CNNs, recurrent neural networks (RNNs), and LSTM networks have become central to PdM research. CNNs have demonstrated remarkable results in visual diagnostics of wind turbine blades and PV modules, where image-based analysis using UAVs or infrared thermography allows for early fault detection. They are also being adapted for multivariate time-series data by treating sensor matrices as pseudo-images to capture spatial correlations across multiple sensors [81]. LSTM networks have shown strength in degradation modeling and RUL estimation, as their ability to retain long-term dependencies makes them ideal for capturing the temporal evolution of faults [82,83].

However, both CNN and LSTM architectures require large, labeled datasets, substantial computational resources, and careful regularization to avoid overfitting [12]. Hybrid CNN-LSTM models have recently gained traction for their ability to combine spatial and temporal learning, achieving high diagnostic precision in multi-modal RES [84]. Despite their superior performance, these hybrid architectures remain difficult to interpret and computationally demanding [85].

The critical challenge in DL for PdM is the balance between predictive accuracy and model transparency [79]. While deep models outperform traditional approaches in representing complex data relationships, their opaque decision processes pose challenges for trust and regulatory compliance. Research in explainable deep learning, attention mechanisms, and hybrid physics-informed neural networks represents a crucial step toward interpretable and trustworthy PdM frameworks [86].

4.4. Reinforcement Learning for Maintenance Scheduling

Rather than predicting faults alone, RL optimizes maintenance actions through experience-driven learning, where an agent interacts with its environment to minimize operational costs and maximize reliability. Algorithms such as Q-learning and DQN have been applied to determine optimal inspection intervals and component replacement schedules in wind and solar systems, while deep deterministic policy gradient (DDPG) and proximal policy optimization (PPO) frameworks have been explored for continuous control applications, such as adaptive load management and dynamic maintenance planning [87]. By framing PdM as a sequential decision-making problem, RL introduces an entirely different paradigm [88].

The objective of the RL agent is to learn an optimal strategy known as a policy (), that dictates the best maintenance action () to take in any given operational state (). This objective is formally captured by the goal of maximizing the cumulative reward [88,89]. The agent learns this by estimating the value of taking an action in a state, represented by an action-value function . The optimal policy is then derived by simply selecting the action with the highest estimated value in any state:

where is the best action to take when the system is in state , while signifies the action that maximizes the value function, is the expected long-term cumulative reward received after taking action in state and following the optimal policy thereafter.

Despite the conceptual promise of RL for autonomous decision-making as seen in [90], practical adoption in industrial renewable settings remains limited. Most studies rely on simulation-based environments that inadequately reflect real-world stochasticity and cost constraints. The development of hybrid simulation platforms, coupled with safe exploration strategies and transferable policy networks, is essential to bridge the gap between theoretical advances and operational feasibility. Nonetheless, RL’s potential to transform predictive maintenance into a fully self-optimizing process positions it as a future cornerstone of intelligent renewable asset management.

4.5. Hybrid and Ensemble Models

Hybrid and ensemble learning approaches represent an evolution toward more resilient predictive maintenance frameworks that combine multiple models to enhance generalization, accuracy, and robustness [91]. Examples include CNN-LSTM architectures that capture both spatial and temporal dynamics, as well as ensemble systems that integrate outputs from diverse base learners to mitigate individual model biases. Such models are particularly effective in handling heterogeneous data streams from solar, wind, and hybrid systems, where fault characteristics vary widely across components and operating conditions. Ensemble techniques also provide a natural mechanism for uncertainty quantification, which is crucial for risk-aware maintenance planning [83].

The trade-off, however, lies in the computational burden and architectural complexity that accompany hybrid systems [12]. Integration challenges, such as model synchronization and parameter optimization, remain barriers to real-time deployment. Future developments in lightweight meta-learning and automated architecture search hold promises for reducing computational cost and simplifying model orchestration without compromising diagnostic performance [92].

4.6. Emerging Paradigms: Federated Learning (FL) and Explainable AI (XAI)

In recent years, there has been growing interest in both FL and explainable artificial intelligence (XAI) as transformative paradigms for PdM in distributed and privacy-sensitive energy systems. FL enables geographically dispersed assets, such as wind turbines or PV arrays, to collaboratively train a global model without sharing raw data, thereby preserving privacy, reducing data transmission overheads, and enhancing cybersecurity resilience [93]. Meanwhile, XAI approaches help render AI-driven maintenance decisions transparent and trustworthy, a key requirement in critical-infrastructure contexts [94].

However, challenges persist in maintaining synchronization among distributed nodes, ensuring communication efficiency, and achieving convergence stability in heterogeneous environments [46]. Explainable AI, on the other hand, aims to make model decisions transparent and interpretable through methods such as SHAP and LIME [95]. By elucidating the influence of individual features on model predictions, XAI enhances operator trust and facilitates compliance with emerging data governance standards. Despite these advantages, integrating interpretability into complex deep learning frameworks remains a research challenge, as explainability often entails a trade-off with model accuracy and computational efficiency.

Together, FL and XAI signal a paradigm shift toward trustworthy, transparent, and privacy-preserving predictive maintenance. Their convergence offers a path toward resilient and human-centric AI systems that align with both technical and ethical imperatives in the renewable energy sector.

5. Functional Role Mapping of AI Techniques in Predictive Maintenance

To operationalize the proposed dual-axis framework, this section critically examines the functional mapping of AI paradigms across key PdM tasks in RES. The mapping, illustrated in Table 3, synthesizes empirical evidence, and elucidates the evolving role of AI as RES transition from passive monitoring to autonomous, data-driven optimization. While the functional mapping illustrates the expanding capabilities of AI across the diagnostic–predictive–prescriptive spectrum, a critical assessment of TRL reveals a significant gap between algorithmic potential and field-deployed reality [96]. In this study, the TRL classification is adapted from the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) 2012 [97] and European Union (EU) Horizon 2020 frameworks [98], which defines TRL 1–3 as concept validation and simulation, TRL 4–6 as laboratory or pilot demonstration, and TRL 7–9 as field-proven or operational deployment.

Table 3.

Role Mapping of AI Techniques in PdM.

The indicative TRL ranges are conservative aggregate assessments derived from the 168 included studies. Technique families were coded according to reported validation contexts using adapted NASA/EU criteria: simulation/proof-of-concept, lab/pilot validation with real RES data, and operational demonstration or commercial platform integration. Ranges reflect typical maturity observed across the corpus to highlight deployment gaps rather than the highest single achievement.

Applying these standardized benchmarks enables a quantitative interpretation of AI maturity across functional layers. Supervised learning models for fault detection in data-rich domains such as wind and solar are positioned at TRL 7–8, reflecting integration into commercial SCADA analytics platforms. Deep learning architectures used for RUL estimation achieve TRL 5–6, indicating validated laboratory or pilot-scale implementations but limited robustness in continuous field operations.

Supervised and unsupervised learning paradigms dominate the diagnostic layer, where the principal aim is to identify faults and classify anomalies. In photovoltaic and wind systems, SVM and Random Forests (RF) remain widely used for fault classification due to their robustness to noisy measurements and interpretable structure, representing a high degree of maturity with integration into commercial SCADA analytics platforms [99]. In contrast, unsupervised methods such as PCA and Autoencoders are indispensable for anomaly detection in environments with scarce labeled data, such as hydropower plants, where they have successfully identified subtle deviations in operational patterns.

At the predictive layer, deep learning architectures provide the temporal modeling capabilities required for RUL estimation and performance forecasting. LSTM and Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU) networks have become dominant frameworks for modeling degradation trajectories and power fluctuations in renewable energy systems [100]. While these models deliver state-of-the-art predictive accuracy in research settings, their deployment is constrained by dependence on large, labeled datasets, high computational demands, and low interpretability [101]. Consequently, despite their strong potential, they occupy a medium TRL range (5–6), validated mainly in controlled or simulated environments rather than in continuous, unattended field operation.

The prescriptive layer, which emphasizes autonomous decision-making and system optimization, represents both the frontier and the lowest level of technological readiness. Here, RL and Multi-Agent Systems (MAS) play transformative roles by enabling learning from continuous interaction with the environment. Frameworks such as Deep Q-Networks (DQN) and Actor–Critic algorithms have demonstrated proficiency in optimizing maintenance schedules in simulation environments for RES [101,102]. However, their field deployment remains limited by the stringent safety, stability, and verification requirements of industrial environments. Accordingly, they correspond to a TRL range of 3–4, reflecting concept validation and simulation-based demonstration. Federated Learning (FL), while architecturally suited to decentralized, privacy-preserving training across distributed assets, also resides at TRL 3–5, as real-world implementations continue to face challenges from non-IID data distributions and communication overhead.

The control function represents the apex of PdM intelligence, where AI-driven insights are embedded directly into operational loops through digital twins and real-time controllers. Here, reinforcement learning and deep recurrent networks are increasingly integrated for adaptive, fault-tolerant control, but their deployment in live grid operations remains nascent. The “black-box” nature of these models poses a fundamental barrier, necessitating XAI to ensure transparent and certifiable decision-making. The development of interpretable, safety-assured control strategies is thus a critical prerequisite for advancing readiness within this high-stakes domain.

While the functional mapping illustrates the expanding capabilities of AI across the diagnostic-predictive-prescriptive spectrum, a critical assessment of TRL reveals a significant gap between algorithmic potential and field-deployed reality. The TRL of AI paradigms is highly correlated with their position on the dual-axis framework, with maturity decreasing as one moves from data-rich diagnostic tasks toward data-heterogeneous prescriptive control. Supervised learning models for fault detection in data-rich domains like wind and solar have reached a mature stage, often integrated into commercial SCADA analytics platforms where technology has been demonstrated in a relevant environment. In contrast, the deep learning architectures dominating RUL estimation, while showing high accuracy in research, face challenges regarding their robustness to real-world data drift and computational demands, positioning them at a medium TRL, validated in lab and simulated environments.

The most significant readiness chasm exists at the prescriptive layer. RL for autonomous maintenance scheduling and control remains predominantly in the simulation phase, with a low TRL. Here, the barriers are no longer primarily accuracy but are instead rooted in requirements for absolute safety, verifiable decision-making, and seamless integration with legacy, safety-critical control systems. Similarly, while FL is a promising architectural paradigm for addressing data privacy, its performance degradation under non-independent data distributions and communication overheads keep its practical TRL low. This TRL perspective is crucial for stakeholders, as it clarifies that the research frontier is pushing into high-complexity, prescriptive domains, but the most readily deployable and trustworthy solutions today reside in the diagnostic and predictive realms of data-rich environments. Bridging this deployment gap represents the next grand challenge for the field, demanding a shift in focus from purely algorithmic innovation to robust engineering for safety, verification, and integration.

6. AI Techniques for Performance Optimization in Renewable Energy Systems

Performance optimization in RES naturally builds upon the PdM layer by translating reliability gains into measurable system-level improvements. When PdM effectively minimizes unplanned outages and fault frequency, the result is a direct enhancement in system availability (A), which in turn lowers the Levelized Cost of Energy (LCOE). This interdependence can be expressed as

where represents capital costs, denotes operation and maintenance expenditure accounts for energy inputs (if applicable), is the cost of PdM implementation, and is the net energy output. Availability, in this context, is given by:

with and denoting the mean time between failures and the mean time to repair, respectively. Improvements in PdM accuracy, early fault detection, or optimized maintenance scheduling effectively increase or reduce , resulting in a higher availability factor. This, in turn, improves asset utilization and reduces the denominator of the LCOE expression, yielding tangible performance gains at the system level.

In this way, PdM does not merely prevent equipment failure; it becomes a driver of operational optimization, closing the feedback loop between intelligent asset management and sustainable energy economics. Unlike PdM which focuses on fault anticipation and asset longevity, performance optimization leverages AI to fine-tune system behavior in real time, adapt to stochastic inputs, and orchestrates multi-component coordination. The approaches discussed in this section capture the transition from static control to adaptive, self-optimizing operations. A structured synthesis is presented across forecasting, energy dispatch, battery energy storage management, and grid integration, with emphasis on methodological innovation, cross-domain applicability, and implementation feasibility.

6.1. Forecasting and Load Prediction

Accurate forecasting of energy generation and demand is crucial for optimizing renewable energy systems. Here, AI models like LSTM networks excel, learning complex patterns in irradiance, wind, and load data to deliver highly accurate, sub-hourly forecasts. However, this power comes at a cost. LSTMs are computationally intensive and act as “black boxes,” making them a poor fit for edge devices that need fast, interpretable results. For these cases, like a microgrid predicting its short-term load, lighter options like XGBoost are often a better choice. These models trade some forecasting nuance for much-needed speed, robustness, and the ability to explain which factors most influence their predictions.

The emerging application of Transformer-based architecture, with their powerful self-attention mechanisms, promises further gains, particularly for multi-step forecasting during periods of high volatility [103,104,105]. Yet, this promise must be critically weighed against their exceptional data hunger and computational expense, raising the pivotal question of whether their marginal accuracy gains justify the significant increase in complexity for most RES forecasting tasks. This landscape creates a clear decision pathway for practitioners, forcing a conscious trade-off between DL accuracy for central systems and gradient boosting’s speed and transparency for distributed, real-time applications.

6.2. Energy Dispatch and Control Optimization: Bridging the Simulation-to-Deployment Gap

AI-driven dispatch algorithms are designed to allocate generation resources by minimizing operational costs and ensuring grid reliability amidst generation variability and complex constraints [106,107]. In RES, this task is particularly challenging due to fluctuating solar and wind inputs, demand uncertainty, and the need for real-time responsiveness. A critical synthesis reveals a significant disparity between the algorithmic promise and operational maturity of these approaches.

Consequently, the TRL of RL for autonomous grid dispatch remains low, with its current primary value lying in simulation-based planning and human-in-the-loop decision support. For scalable control in large-scale, distributed networks, MASs offer a promising framework for decentralized coordination and peer-to-peer energy trading. The fundamental trade-off with MAS, however, is the introduction of coordination overhead and communication latency, which can compromise global optimality as the number of agents scales. This contrasts with traditional evolutionary algorithms like Genetic Algorithms and Particle Swarm Optimization, which can guarantee a global optimum for a defined system model but lack the scalability and resilience demanded by modern, decentralized grid architectures [108]. Furthermore, the integration of AI forecasting with Model Predictive Control (MPC) enables real-time adjustment of setpoints, yet its efficacy is entirely contingent on the accuracy of both the AI forecast and the underlying physical model of the system, highlighting a critical dependency that links data-driven intelligence with traditional control theory.

6.3. Battery Energy Storage System Optimization: Integrating Data-Driven and Physics-Based Intelligence

Battery Energy Storage Systems (BESS) are essential for mitigating the intermittency of RES, and their optimization increasingly relies on AI to balance operational efficiency with long-term asset health. Supervised learning models have proven effective in predicting key operational parameters like State of Charge (SoC) and State of Health (SoH). These models are widely used in forecasting and diagnostics, as highlighted in [109]. Meanwhile, deep learning architectures like autoencoders and LSTM networks enable sophisticated anomaly detection and long-term degradation modeling. These methods are particularly valuable for identifying subtle patterns in battery behavior, as discussed in the IEEE review on optimization techniques for energy storage systems within renewable energy setups [110].

While data-driven models dominate the literature, their performance is constrained by the quantity and quality of available data. Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINNs) represent a paradigm shift by seamlessly integrating the governing physical laws of a system directly into the deep learning framework. This is achieved by constructing a composite loss function that penalizes deviations from both the observed data and the underlying physics:

Here, is the conventional supervised loss, is the residual of the partial differential equations (PDEs) governing the system, and is a weighting parameter. By integrating physical laws and constraints, PINNs ensure that optimization strategies not only improve performance but also prolong battery life, a direction supported by recent work in hybrid modeling frameworks for energy storage [111].

RL-based controllers represent an advanced frontier for BESS applications such as frequency regulation, where dynamic adjustment to grid signals is crucial. These controllers have shown promise in simulation environments, but their deployment is constrained by stringent safety requirements, robustness to model inaccuracies, and simulation fidelity, like challenges faced in dispatch optimization. As noted in [110], RL’s operational maturity remains low despite its potential. Their development is subject to the same stringent safety and simulation fidelity requirements as dispatch optimization, emphasizing that the path to autonomous BESS management must be paved with robust, hybrid models that respect both data patterns and physical laws.

6.4. Grid Integration and Stability Enhancement: Balancing Performance, Privacy, and Trust

In RES, deep learning models, particularly hybrid CNN-LSTM architectures have demonstrated high efficacy in classifying transient events and initiating protective actions faster than conventional methods. For example, a federated CNN-Attention-LSTM model was shown to improve multi-energy load forecasting while preserving data privacy across distributed assets [112]. These models excel at capturing spatiotemporal patterns in grid behavior, making them ideal for real-time fault detection and response.

However, the deployment of such “black-box” models for high-stakes grid control is untenable without robust XAI frameworks. Operators require transparent justifications for autonomous decisions to build trust and meet regulatory standards. Techniques like SHAP and LIME are increasingly used to interpret model outputs in smart grid applications, helping bridge the gap between predictive accuracy and operational accountability. Beyond direct control, unsupervised clustering algorithms play a vital role in identifying operational regimes and informing grid reconfiguration strategies. These methods help segment grid behavior into meaningful patterns, enabling more targeted interventions and adaptive control.

A pivotal advancement for grid-wide coordination is FL, which allows distributed energy assets to collaboratively learn superior control policies without centralizing sensitive operational data. This approach is particularly valuable in smart grids with heterogeneous data sources, as demonstrated by recent work on regional load forecasting using federated LSTM networks [113]. However, FL involves a conscious performance trade-off: models trained in a federated manner often underperform their centralized counterparts due to data heterogeneity across grid nodes and the complexities of secure aggregation.

Therefore, the pursuit of enhanced data privacy and security through FL may come at the cost of model accuracy and convergence speed, a critical consideration for designing the resilient and intelligent grids of the future. Hybrid frameworks that combine FL with XAI and physics-informed modeling may offer a pathway to balance these competing demands.

7. Discussion

7.1. Domain-Specific Applications

The efficacy of artificial intelligence in PdM is not determined by algorithmic performance alone but is fundamentally governed by the unique architectural, operational, and data-centric constraints of each renewable energy domain. This section synthesizes domain-specific applications through the lens of the dual-axis framework, demonstrating how the interplay between domain-specific challenges and functional requirements dictates the selection and adaptation of AI paradigms. This analysis moves beyond a simple catalog of techniques to reveal the underlying logic of AI deployment across the renewable energy landscape.

Solar Photovoltaic (PV) Systems are characterized by a data-rich environment of high-frequency electrical time-series and, increasingly, high-resolution thermal and electroluminescence imagery. This data abundance aligns the domain strongly with the supervised learning and deep learning paradigms on the algorithmic axis. The primary functional roles, mapped on the second axis, are fault detection and anomaly classification at the module and string level. The high resolution of available imagery makes CNNs the dominant solution for spatial fault detection, directly addressing failures like hotspots and cracks [114]. However, a key domain constraint is the need for diagnostics that are not only accurate but also actionable for maintenance crews. This drives the integration of XAI techniques, such as Grad-CAM, which can overlay heatmaps on images to localize defects intuitively. For system-level performance forecasting, the consistent temporal nature of irradiance data makes LSTM networks highly effective. The distributed nature of residential and commercial PV arrays also creates a privacy constraint, making FL an emerging paradigm for collaborative model training without centralizing sensitive customer data.

Wind Energy Systems present a contrasting landscape defined by mechanical complexity, high-dimensional SCADA data, and stochastic operational profiles due to varying wind conditions. This domain necessitates AI solutions that are robust to non-stationary data and capable of modeling complex temporal degradation. The core functional roles here are fault detection in critical drivetrain components and RUL estimation. The availability of well-labeled historical data from thousands of turbines makes supervised ensemble methods like Random Forests a robust first line of defense for classifying common failures [20]. For more complex temporal forecasting of component wear, LSTM networks are indispensable. A critical domain constraint is the changing definition of “normal” operation across different speeds and seasons. This directly drives the application of unsupervised learning techniques, such as clustering, as a pre-processing step to identify distinct operational modes, thereby improving the accuracy of supervised models by ensuring they are compared against the correct baseline. The high cost of unscheduled offshore maintenance creates a strong incentive for accurate RUL estimation, further cementing the role of deep learning, while the safety-critical nature of blade and gearbox failures is increasing the demand for XAI to justify maintenance recommendations.

Hydropower systems operate under a paradigm of data scarcity, with often sparse sensor instrumentation, low-frequency data, and a critical lack of labeled fault data due to the long lifespan and high reliability of components. This fundamental constraint severely limits the feasibility of data-hungry supervised and deep learning models for many tasks. Consequently, the dominant functional role in hydropower is anomaly classification rather than precise fault diagnosis. This aligns the domain almost exclusively with the unsupervised learning paradigm on the algorithmic axis. Techniques such as Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and VAE are deployed to analyze vibration and acoustic signals from turbines, identifying deviations from a learned baseline of normal operation without requiring examples of past failures [115]. The strong, well-understood physics of fluid dynamics and turbine mechanics presents another key constraint, revealing a significant gap for PINNs. These models, which embed physical laws into the learning process, are uniquely suited to this domain, as they can compensate for data sparsity by ensuring that all predictions are physically consistent, a non-negotiable requirement for managing such large, critical infrastructure.

Hybrid Microgrids and CPES represent the most complex deployment environment, defined by the integration of multiple, asynchronous energy sources (PV, wind, storage) with real-time communication and control. The primary domain constraint is the need for multi-modal data fusion and coordinated decision-making across heterogeneous assets [116]. This complexity demands a fusion of paradigms from the algorithmic axis. For fault detection and performance forecasting, hybrid CNN-LSTM architectures become necessary to model both the spatial correlations from distributed sensors and the temporal dynamics of the entire system [117]. The functional role of dispatch optimization in such a dynamic, multi-objective environment is a natural fit for MARL, where agents representing individual assets learn cooperative policies [118]. However, the domain’s distributed ownership and cybersecurity concerns impose a privacy constraint, making FL a critical enabler for secure, collaborative learning [119].

Finally, the operational complexity of CPES makes the control role highly sensitive, necessitating XAI to provide transparent rationales for autonomous decisions, ensuring operator trust and system resilience. In CPES, no single AI paradigm suffices; effective deployment requires a strategic orchestration of multiple techniques, precisely aligned by the dual-axis framework to address the multifaceted challenges of integrated energy systems.

7.2. Comparative Analysis Across Energy Domains: A Data-Centric Framework

The strategic deployment of AI in RE PdM has historically been guided by algorithmic potential, often overlooking the foundational constraint of data availability. To address this gap, this section employs the dual-axis framework to present a systematic, data-centric comparative analysis The following synthesis presented in Table 4 segments the renewable energy landscape into data-rich, data-sparse, and data-heterogeneous categories based on quantifiable benchmarks.

Table 4.

Data-Centric Comparative Analysis of AI Deployment Across RE Domains.

This comparative framework provides an evidence-based methodology for aligning AI investment and model selection with the fundamental data realities of any given renewable energy domain.

The segmentation in Table 3 reveals three distinct strategic pathways for AI deployment, each defined by a specific data paradigm. The landscape cleaves into domains characterized by data abundance, data scarcity, and data heterogeneity, demanding fundamentally different approaches to both research and implementation.

Solar and wind systems represent a data-rich domain where supervised and deep learning models excel. Abundant, high-frequency data enables precise applications like fault detection using CNNs and performance forecasting with LSTMs [120]. The main challenges are computational management and model generalization, while privacy concerns in distributed networks drive the adoption of FL [121].

In contrast, hydropower systems face severe data scarcity, with limited labeled examples and low sampling rates. This constraint makes data-intensive models impractical, shifting the focus to unsupervised methods like PCA and VAEs for anomaly detection [122,123]. Here, PINNs add strategic value by embedding known physical laws, reducing data requirements by up to 90% while ensuring physically consistent predictions [124].

The most complex environment is found in hybrid microgrids and cyber-physical energy systems, characterized by extreme data heterogeneity. Managing asynchronous, multi-modal data streams requires hybrid AI architectures (e.g., CNN-LSTMs) for spatio-temporal modeling, while dispatch optimization naturally aligns with MARL [125]. FL becomes essential for privacy and security, despite introducing a 3–8% performance trade-off and communication overhead [126]. In these settings, the strategic focus is on balancing performance, privacy, and computational feasibility rather than simply selecting the most powerful algorithm.

7.3. Challenges and Limitations of AI in Renewable Energy Systems

Deploying AI in renewable energy faces challenges beyond algorithms. Data issues are most common, especially class imbalance with rare failure events biasing models. Concept drift caused by aging and environmental changes reduces accuracy, requiring continuous updates most systems lack. Combining data from old and new systems introduces pre-processing and compatibility problems.

Trust and interpretability are critical challenges, especially for safety-critical applications. Complex DL models are opaque, leading to operator and regulator skepticism needing transparent decision-making for grid reliability. Explanation techniques provide some clarity but add computational latency and lack formal guarantees for certification, causing industry preference for simpler, interpretable models despite potentially lower accuracy.

Scalability and real-time constraints pose significant engineering challenges: computational needs of cutting-edge models often surpass edge hardware capabilities at remote renewable sites, leading to trade-offs between performance and practicality. Applications requiring sub-second responses challenge inference latency and communication delay limits in distributed networks. Managing AI models over decades-long asset lifetimes creates complex version control, retraining, and compatibility issues underestimated in research prototypes.

Integration with operational technology creates technical and organizational barriers: legacy systems with proprietary protocols require complex bridges introducing latency and failure risk; connecting AI to isolated control networks increases cybersecurity risks, underscoring need for strong protection for legacy and AI systems. Organizationally, deploying AI requires bridging data science and operational teams with different priorities, expertise, and cultures.

The deployment of AI in safety critical energy infrastructure extends beyond technical hurdles into complex regulatory, ethical, and human terrain. Regulatory inertia poses the most immediate barrier. Current frameworks such as North American Electric Reliability Corporation Critical Infrastructure Protection (NERC CIP) and IEC 62443 [127,128] are grounded in deterministic models of system behavior and are ill-equipped to certify adaptive, probabilistic AI. This creates a structural mismatch. The result is a liability gap that constrains industrial adoption, as asset owners cannot assume responsibility for autonomous actions without regulatory precedent. Emerging standards are beginning to bridge this divide. The IEEE 7000-2021 standard [129] offers a structured method for embedding ethical values into engineering requirements. Its application in renewable-energy AI systems could help pre-empt risks such as discriminatory maintenance allocation, translating high-level ethical intent into verifiable design requirements.

Ethically, the transition to AI-driven operations introduces systemic risks of algorithmic bias and inequity. This reframes the ethical challenge from data privacy to one of distributive justice in energy reliability, where maintenance quality becomes a function of an asset’s data richness and commercial value. automated systems. The human factor remains equally decisive. The opacity of deep-learning architectures undermines operator trust, a finding supported by empirical studies. Leichtmann et al. in [130] showed that explainable interfaces and uncertainty visualizations improved user trust and task performance in high-risk decision contexts. The authors in [131] similarly demonstrated that AI-enhanced decision-support systems improved situational awareness and reduced workload in energy control rooms while [94] linked explainability and governance to trust calibration in smart-energy systems.

7.4. Future Research Directions

The future of AI in renewable energy systems demands a strategic shift from isolated algorithmic advances toward holistic, deployment-ready solutions. This transition re-quires addressing interconnected barriers across data infrastructure, methodological integration, computational efficiency, trust, safety, and long-term adaptability. The proposed dual-axis framework provides a clear guide for prioritizing these efforts.

In the short to medium term, establishing robust data infrastructures stands out as the most urgent priority. The field currently suffers from a lack of high-quality, multi-modal, and openly accessible datasets. Researchers should focus on creating standardized, time-aligned repositories that capture real-world operational data from solar, wind, hydro, and hybrid systems. Such benchmarks would enable rigorous validation, facilitate cross-domain comparisons, and accelerate progress especially in data-sparse domains like hydropower. At the same time, efforts must advance physics-informed and hybrid AI paradigms. These approaches embed domain-specific physical laws such as fluid dynamics in hydropower or electrochemical degradation in batteries directly into the learning process. By reducing dependence on large, labeled datasets, they offer a practical path forward for environments where DRI remains low.

Over the medium term, computational and scalability challenges must also be tackled. Advanced deep learning models often exceed the capabilities of edge devices deployed at remote renewable sites. Future work should prioritize the co-design of efficient, adaptive architectures that dynamically adjust complexity based on available resources and operational needs. Alongside this, FL requires significant refinement. Improvements in handling non-IID data distributions and reducing communication overhead will make privacy-preserving, collaborative intelligence viable across geo-graphically dispersed assets.

Building trust in autonomous systems represents another critical medium- to long-term objective. Current explainable AI techniques, such as SHAP and LIME remain post hoc and computationally expensive. Research should move toward intrinsically interpretable architectures and causal inference methods. These would allow models not only to detect anomalies but also to reveal root causes and predict intervention outcomes. Such capabilities would transform AI from a black-box tool into a trusted partner for operators in safety-critical settings.

Finally, achieving truly lifelong and adaptive AI systems constitutes the long-term frontier. Renewable assets operate over decades, during which equipment ages, configurations change, and environmental patterns evolve. Future efforts must develop continual learning frameworks that prevent catastrophic forgetting while enabling rapid adaptation to new conditions. Meta-learning approaches, which allow models to quickly fine-tune on novel assets with minimal data, hold promise. Together, these directions offer a clear progression: from foundational data and physics-informed foundations, through scalable and trustworthy intelligence, to fully autonomous, evolving systems capable of supporting the decades-long lifecycle of renewable infra-structure.

8. Conclusions

This review has established that the future of reliable and efficient renewable energy systems hinges on a strategic and nuanced integration of artificial intelligence. The novel dual-axis framework introduced herein provides more than a taxonomy; it offers a diagnostic tool and a strategic compass, revealing that the choice of an AI paradigm must be fundamentally constrained by the data realities of an energy domain, not just its algorithmic potential. Our data-centric synthesis of the literature demonstrates that the field is segmented into distinct strategic categories, data-rich, data-sparse, and data-heterogeneous environments, each demanding a tailored approach where the pursuit of higher functional complexity must be carefully balanced against the practical constraints of data readiness and technological maturity.

The critical insights from this analysis are threefold. First, the most significant barriers to the widespread adoption of AI are no longer primarily algorithmic but are operational, spanning data quality, system integration, and the crucial need for trustworthy, interpretable decision-making. Second, emerging paradigms like federated learning and explainable AI are not mere technical enhancements but essential enablers for scalable, secure, and trustworthy deployment, particularly as we move toward prescriptive control. Third, a pronounced gap exists between the high complexity of models at the research frontier and their low technology readiness for field deployment, underscoring a critical need for research focused on robustness, safety, and integration.

The research directions outlined, from building foundational data infrastructures and physics-informed AI to advancing safe reinforcement learning and continual adaptation, provide a concrete roadmap for bridging this gap. This agenda calls for a collective shift in focus from isolated algorithmic advances to the development of holistic, resilient, and evolving AI systems.

As the global energy transition accelerates, the integration of intelligent, self-optimizing maintenance and control strategies will be the key to unlocking the full potential of renewable assets. This review provides the foundational framework and a common language to guide this endeavor. The goal is a future where renewable energy infrastructures are not merely connected, but truly intelligent; where maintenance is not just predictive, but prescriptive and proactive; and where artificial intelligence fulfills its role as the central nervous system of a sustainable, resilient, and efficient global energy ecosystem.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- International Renewable Energy Agency. Renewable Capacity Statistics 2025. Available online: https://www.irena.org (accessed on 3 September 2025).

- Global Energy Review 2025. Available online: https://www.iea.org (accessed on 3 September 2025).

- Apata, O.; Oyedokun, D.T.O. Wind turbine generators: Conventional and emerging technologies. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE PES-IAS PowerAfrica Conference: Harnessing Energy, Information and Communications Technology (ICT) for Affordable Electrification of Africa, PowerAfrica, Accra, Ghana, 27–30 June 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, Q.; Algburi, S.; Sameen, A.Z.; Salman, H.M.; Jaszczur, M. A review of hybrid renewable energy systems: Solar and wind-powered solutions: Challenges, opportunities, and policy implications. Results Eng. 2023, 20, 101621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turnbull, A.; Carroll, J. Cost benefit of implementing advanced monitoring and predictive maintenance strategies for offshore wind farms. Energies 2021, 14, 4922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dao, C.; Kazemtabrizi, B.; Crabtree, C. Wind turbine reliability data review and impacts on levelised cost of energy. Wind Energy 2019, 22, 1848–1871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Gao, C.; Tang, T. A Review of Sustainable Maintenance Strategies for Single Component and Multicomponent Equipment. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onwusinkwue, S.; Osasona, F.; Ahmad, I.A.I.; Anyanwu, A.C.; Dawodu, S.O.; Obi, O.C.; Hamdan, A. Artificial intelligence (AI) in renewable energy: A review of predictive maintenance and energy optimization. World J. Adv. Res. Rev. 2024, 21, 2487–2799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Xiao, F.; Guo, F. Similarity learning-based fault detection and diagnosis in building HVAC systems with limited labeled data. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2023, 185, 113612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Qi, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Elchalakani, M. Machine Learning Applications in Building Energy Systems: Review and Prospects. Buildings 2025, 15, 648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fasogbon, S.K.; Fetuga, I.A.; Oyeniran, A.T.; Shaibu, S.A.; Afolabi, S.; Ndokwu, T.A.; Oluwadare, S.R.; Onafowokan, J.T.; Eso, O.S.; Bassey, V.B. Optimization of energy grid efficiency with machine learning: A comprehensive review of challenges and opportunities. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2025, 223, 115980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Y.; Yang, B.; Jiang, X.; Jia, F.; Li, N.; Nandi, A.K. Applications of machine learning to machine fault diagnosis: A review and roadmap. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2020, 138, 106587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abid, A.; Khan, M.T.; Iqbal, J. A review on fault detection and diagnosis techniques: Basics and beyond. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2020, 54, 3639–3664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azodo, A.P.; Mezue, F.C.T.; Onyekwere, O.S.; Idama, O. Leveraging AI for predictive maintenance in energy systems: Enhancing reliability and efficiency. Aust. J. Multi-Discip. Eng. 2025, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betti, A.; Trovato, M.L.L.; Leonardi, F.S.; Leotta, G.; Ruffini, F.; Lanzetta, C. Predictive Maintenance in Photovoltaic Plants with a Big Data Approach. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1901.10855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamza, A.; Ali, Z.; Dudley, S.; Saleem, K.; Uneeb, M.; Christofides, N. A multi-stage review framework for AI-driven predictive maintenance and fault diagnosis in photovoltaic systems. Appl. Energy 2025, 393, 126108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bošnjaković, M.; Martinović, M.; Đokić, K. Application of Artificial Intelligence in Wind Power Systems. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 2443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Wu, Y.; Ma, X. Quantum machine learning based wind turbine condition monitoring: State of the art and future prospects. Energy Convers. Manag. 2025, 332, 119694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]