Abstract

While battery electric vehicles (BEVs) are pivotal for transport decarbonization, existing life cycle assessments (LCAs) often confound vehicle design effects with inter-brand manufacturing variations. In this study, a comparative cradle-to-grave LCA was conducted for three distinct BEV segments—a sedan, an SUV, and an MPV, produced by a single manufacturer on a shared platform. Leveraging detailed bills of materials, plant-level energy data, and region-specific emission factors for a functional unit of 150,000 km, we quantify greenhouse gas emissions across the full life cycle. Results show the total emissions scale with vehicle size from 25 to 31 t CO2-eq. However, the MPV exhibits the highest functional carbon efficiency, with the lowest emissions per unit of interior volume. Material production and operational electricity use dominate the emission profile, with end-of-life metal recycling providing a 15–20% mitigation credit. Scenario modeling reveals that grid decarbonization can slash life cycle emissions by around 30%, while advanced battery recycling offers a further 15–18% reduction. These findings highlight that the climate benefits of BEVs are closely linked to progress in power system decarbonization, and provide references for future optimization of low-carbon vehicle production and reuse.

1. Introduction

Battery electric vehicles (BEVs) are widely recognized as a cornerstone technology for deep decarbonization of road transport [1]. Integrated mitigation pathways consistently show that large-scale electrification of passenger cars, combined with rapid power-sector decarbonization, is among the most effective strategies to reduce economy-wide greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in net-zero scenarios [2]. Beyond climate and air-quality benefits, the current acceleration of electrified mobility is also driven by energy-security concerns. Furthermore, it reflects a strategic repositioning of countries and firms along emerging clean-technology value chains, particularly in batteries and critical minerals. In this global transition, China is the world’s largest BEV market and a major manufacturing hub. This makes it a critical case for assessing how design, manufacturing, electricity, and end-of-life management shape life cycle emissions [3]. Although BEVs have zero tailpipe emissions during operation, their overall climate performance depends on the full life cycle of vehicles, including raw material extraction, vehicle and battery manufacturing, electricity generation, and end-of-life treatment [4]. A rigorous cradle-to-grave life cycle assessment is therefore indispensable for understanding the true carbon footprint of BEVs and for designing effective mitigation pathways.

Over the past few years, a substantial body of LCA studies has compared BEVs with internal combustion engine vehicles (ICEVs) under different regional and technological conditions. For Europe, most analyses conclude that, despite higher production-phase emissions driven by traction battery manufacturing, BEVs achieve significantly lower life cycle greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions than comparable ICEVs when the use phase is included, particularly under present and projected low-carbon electricity mixes [5,6,7]. Similar conclusions have been reported for China and other emerging economies, although the magnitude of the advantage is more sensitive to coal-dominated power structures and regional differences in grid carbon intensity [8,9,10]. Across these studies, several robust patterns emerge: (i) the carbon intensity of electricity is the dominant driver of use-phase emissions; (ii) materials production and battery manufacturing account for a large share of upstream emissions, while vehicle assembly itself contributes comparatively little; and (iii) end-of-life treatment, including metal recovery and battery recycling, can offset part of the production burden but is often represented in a simplified manner.

At the same time, component-level LCAs for lithium-ion batteries and lightweight body structures highlight the importance of battery chemistry, manufacturing energy intensity and recycling routes [11]. Considerable variability and uncertainty are present in the published inventory data. National and provincial studies for China further show that BEVs already outperform ICEVs on a life cycle basis [8], but that net benefits vary substantially across regions and depend on assumptions regarding vehicle lifetime, driving intensity, and the evolution of the power system.

Within the existing literature, three specific gaps remain regarding the life cycle carbon footprint of BEVs. First, most comparative LCAs either contrast BEVs with ICEVs or analyze only one or a few BEV models from different brands, so the effects of vehicle class and body type cannot be separated cleanly from differences in manufacturing systems [12]. Systematic cradle-to-grave comparisons of several BEV segments from the same manufacturer and production system are still rare, and empirical evidence on how class, mass distribution and interior volume jointly shape life cycle emissions under controlled manufacturing conditions is limited. Second, many studies in China and elsewhere rely on national databases or generic inventory data. In contrast, brand-specific modeling, which integrates detailed bills of materials, plant-level energy use, and actual powertrain configurations remains uncommon [13]. This lack of specificity weakens design-relevant insights for manufacturers and can mask key structural differences between vehicle segments built on the same platform. Third, grid decarbonization and end-of-life management are widely recognized as key levers for reducing BEV life cycle emissions [14]. However, existing research often examines these factors separately or for a single vehicle type, with few studies quantifying the individual and combined mitigation potential of grid decarbonization and enhanced recycling for diverse BEV segments within a unified model.

In response, this study presents a comparative LCA assessment of three mainstream BEV models from the same brand: a B-class sedan, a mid-to-large SUV and an MPV, all with steel–aluminum hybrid bodies and lithium iron phosphate (LFP) traction batteries. The study follows ISO 14067 and related LCA standards [15], uses 150,000 km of lifetime driving per vehicle as the functional unit, and combines primary design and manufacturing data from the Original Equipment Manufacturer (OEM) with regionally representative electricity and background process data. In summary, this work presents the following main contributions:

- Establish a transparent, internally consistent life cycle assessment of three BEV segments from a single manufacturer, providing segment-level carbon benchmarks that separate vehicle design effects from inter-brand differences;

- Introduce normalized performance indicators, including emissions per unit interior volume and energy use per unit curb mass, to enable a more differentiated evaluation of climate efficiency across vehicle classes;

- Quantify the emission reduction potential of combining cleaner electricity in production and use with enhanced recycling of vehicle metals and battery materials, and demonstrate the additional life cycle mitigation achievable at the segment level under these strategies.

The article is structured in the following sections. Section 2 describes the three vehicle models, the system boundary and the life cycle carbon accounting framework. Section 3 presents the inventory data, including data sources, processing steps and key assumptions. Section 4 reports and discusses the results, covering baseline life cycle profiles, phase-wise emission characteristics and decarbonization scenarios based on cleaner electricity and recycling. Section 5 concludes the study and outlines implications for vehicle design, recycling strategies and low-carbon power development in China.

2. Methodology

The LCA follows a cradle-to-grave framework, encompassing raw material acquisition, component production, vehicle assembly, vehicle use, and end-of-life recycling. In line with ISO 14040/44 [16] and ISO 14067 standards [15], we adopt a systematic LCA approach with four iterative phases: goal and scope definition, inventory analysis, impact assessment, and interpretation. The functional unit is one vehicle driven 150,000 km over its lifetime, corresponding to a typical service life of around ten years in passenger car LCAs. This choice ensures a consistent comparison across models [17].

2.1. Vehicle Models and Technical Characteristics

The analysis considers three BEVs from a single manufacturer: a B-class sedan, a mid-size SUV, and an MPV. All three share the same steel–aluminum hybrid body structure and use LFP traction batteries. Table 1 summarizes the main technical characteristics of the three vehicles, including overall dimensions, mass distribution across the body, chassis, powertrain and fluids, battery capacity, electricity consumption per 100 km and rated motor power. The MPV is the longest and heaviest of the three models, with a body-in-white mass of about 924 kg, while the sedan is the shortest and lightest, with a body-in-white mass of about 744 kg. Battery capacities are similar, in the range of 80–84.5 kWh, and each model is equipped with a traction motor rated at approximately 230–235 kW. Measured energy consumption lies between 13.4 kWh per 100 km for the sedan and 16.2 kWh per 100 km for the MPV. Collectively, these vehicles cover compact, SUV and MPV segments, while remaining within a common design and production context, which enables a controlled comparison of life cycle carbon emissions. As revealed by Mendziņš et al. [18], BEVs maintain significantly lower well-to-wheel CO2 emissions compared to ICEVs in key markets like China and Europe, a gap that continues to widen as electricity generation decarbonizes.

Table 1.

Parameters of different types of BEV.

2.2. System Boundary and Function Unit

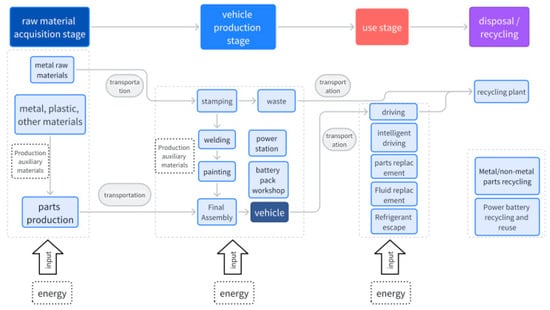

This study uses a cradle-to-grave LCA framework that includes all life phases from raw material extraction through end-of-life recycling. The system boundary comprises four sequential phases: (i) raw materials and component manufacturing, including mining, refining, and fabrication of all parts, as well as the transportation of materials to the manufacturing plant; (ii) vehicle production, including assembly, painting, and other factory processes; (iii) vehicle use, including electricity consumption for driving and inputs related to maintenance; and (iv) end-of-life treatment, including vehicle disassembly and metal recycling. Figure 1 illustrates this boundary. All greenhouse gas emissions from energy and material flows within these phases are included in the foreground system. The functional unit is one vehicle driven 150,000 km over its lifetime, which represents a typical service life for passenger vehicles in China (corresponding to a duration of approximately 10–12 years). This assumption aligns with the maintenance schedule modeled in the use phase, which accounts for the replacement of aging consumables such as tires and fluids [19]. Results are reported as kg CO2-eq per vehicle over 150,000 km and, where appropriate, normalized per kilometer. The life cycle inventory combines detailed foreground data from the manufacturer, such as bills of materials and plant energy use, with background data such as grid electricity mixes and material-specific emission factors, in accordance with ISO 14044 [16] and ISO 14067 [15].

Figure 1.

The carbon emission system boundary of the entire life cycle of a vehicle.

2.3. Life Cycle Carbon Accounting Model

The total life cycle carbon footprint E is calculated as the sum of the four phase contributions:

where E1 = raw material and component manufacturing, E2 = vehicle production, E3 = use phase, and E4 = end-of-life recycling. Each term is computed with a phase-specific submodel. Emission factors, expressed in kg CO2-eq per unit of activity, follow GWP100 conventions and are applied to all material and energy flows. This modular structure provides a transparent accounting of all relevant CO2-eq sources throughout the vehicle life cycle, both in the manufacturer’s operations and in the upstream supply chain.

2.3.1. Raw Material and Component Manufacturing

Emissions E1 account for all CO2e embodied in the vehicle’s materials and parts. We model this by summing, for each component i, the emissions from each raw material j it contains plus any fabrication emissions. Formally:

where n is the total number of parts. EMij is the embedded emission in part i from raw material j, and EPi is the emission from producing component i through stamping, molding, machining, and other operations. In practical terms, the mass of each material category such as steel, aluminum alloy, copper, plastics, glass, rubber, and fluids is multiplied by the corresponding background emission factor to obtain EMij. Manufacturing emissions EPi include the energy and process emissions arising from component production, including transport and handling where relevant. Summing across all components provides the total embodied emissions in the bill of materials.

2.3.2. Vehicle Production

Emissions E2 represent the total GHG emissions from energy consumed at the vehicle assembly plant during manufacturing. These emissions encompass all on-site fuel combustion and electricity use across assembly processes, then per-vehicle emissions are given by:

where EDij denotes the CO2e emissions from fuel combustion in the j-th unit of equipment of type i, ER denotes the CO2e from the plant’s total electricity consumption, EW denotes the CO2e from other on-site fuel use, and M denotes the number of vehicles produced.

2.3.3. Vehicle Use Phase

Emissions E3 during operation arise mainly from electricity generation for propulsion, plus minor maintenance. As BEVs have zero tailpipe CO2, all operational emissions arise upstream from electricity generation and the production of replacement parts.

Lifetime electricity-related emissions are calculated from the vehicle’s rated energy consumption, the lifetime mileage, and the grid emission factor:

where is energy use per 100 km in kWh, S is lifetime distance in km, and K is the grid emission factor in kg CO2e per kWh. ECij is the cradle-to-gate emission for the j-th replacement of consumable i, p is the number of consumable types, and Ni is the number of replacements of consumable i over S.

2.3.4. End of Life Vehicle Scrapping and Recycling

Emissions E4 cover dismantling and processing of the vehicle’s recyclable materials. We assume a 98% mass recovery at end-of-life and focus on metal recycling. Battery recycling is excluded due to the current lack of large-scale infrastructure and reliable data [20]. The CO2e here comes from the energy used in recycling processes. If Ee,i and Ec,i are the CO2e from electricity and fuel used to process material i, then:

where Ee,i is the carbon emission generated by the consumption of electricity for processing the i-th material, and Ec,i is the carbon emission generated by the use of fuel for processing the i-th material, and t represents all types of recyclable materials.

3. Life Cycle Inventory and Data Compilation

The life cycle inventory is compiled mainly from site specific data provided by the vehicle manufacturer. Material composition, component level energy use and plant electricity consumption are obtained through on-site surveys. For energy carriers and upstream processes that are not directly monitored, such as coal, electricity and natural gas supply, the study draws on localized research and regional databases that report Chinese carbon emission factors [21]. On this basis, consistent inventories are established for the three battery electric vehicle models for all phases defined in the methodological framework.

3.1. Material Composition and Upstream Processes

Each vehicle is decomposed into four systems: body, chassis, powertrain, and fluids. For every system, the mass of each material is taken from production records, covering steel, aluminum, copper, magnesium and zinc alloys, plastics, rubber, glass, coatings, and other minor materials. Using background emission factors for these materials, the embodied emissions of the body, chassis, powertrain, and fluids are calculated for each model. The resulting material breakdown and subsystem-level-embodied emissions are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Material mass of three different types of BEV.

Component manufacturing is represented by specific electricity and heat demand per unit mass for representative parts in each system. Data are available for body components such as glass panels, longitudinals, thresholds, doors, floor assemblies, exterior parts, interior parts and battery holders, for chassis components such as springs, bearings, rims, tires and wiring systems, and for powertrain components such as traction and low voltage batteries, speed reducers, drive motors and electronic control devices. These energy intensities, together with the corresponding manufacturing emissions, are summarized in Table 3. Body panels stamped within the vehicle plant, such as the front and rear floor assemblies, are treated as part of the assembly phase rather than component manufacturing. Transport of raw materials and purchased components is included by multiplying ton kilometer values by an emission factor for medium and heavy-duty trucks of 0.129 kgCO2e/t·km [22]. The resulting transport emissions for the three models are reported in Table 4.

Table 3.

Energy consumption of different types of BEV components in production and manufacturing.

Table 4.

Carbon emissions from transportation of components and materials for three different types of BEV.

3.2. Manufacturing Energy and Assembly Operations

Vehicle production comprises body forming, welding, painting and final assembly, and in some cases die casting. All three battery electric vehicles are produced in the same factory, on a common assembly line and under similar production cycles. Differences in tooling, part geometry and configuration among the three models have only a limited influence on the overall energy demand of the plant, which is small compared with the upstream material burden. Assembly processes are therefore represented in a unified way for all models so that the production phase reflects the characteristics of the shared manufacturing system rather than model specific variations.

Annual consumption of electricity and fuels at the plant is converted into greenhouse gas emissions using the relevant emission factors. The resulting total is allocated to individual vehicles on the basis of the yearly output of the assembly line, which yields a single per-vehicle emission value for assembly that is applied consistently to the sedan, the sport utility vehicle, and the multi-purpose vehicle. This treatment captures the energy and emissions associated with stamping, welding, painting, and final assembly, while keeping the production inventory compact and directly comparable across the three battery electric vehicle types.

3.3. Operational Energy Use and Maintenance Flows

During the use phase the battery electric vehicles do not emit carbon dioxide directly from the exhaust. The operational inventory therefore consists of traction electricity demand and the production and replacement of maintenance parts. The power consumption of the three BEVs is based on actual data, traction electricity use is derived from measured energy consumption per one hundred kilometers for each model. According to the data of China Automotive Technology and Research Center Co., Ltd. (CATARC) [23], lifetime driving distance is set as 150,000 km. Specifically, the national average electricity carbon footprint factor for 2023, as officially released by the Ministry of Ecology and Environment [24], is applied to convert this electricity use into greenhouse gas emissions. The resulting emissions from lifetime electricity consumption for the three vehicles are reported in Table 5.

Table 5.

Carbon emissions during the use phase of the three different types of BEV.

Maintenance-related flows include the replenishment of operating fluids, including air conditioning refrigerant, and the replacement of tires and the low-voltage auxiliary battery. A replacement schedule is adopted in which the tires and the low-voltage battery are replaced twice and fluids are replenished three times over the vehicle lifetime. The refrigerant is characterized by a global warming potential of 1300 [25]. Emissions associated with these maintenance activities are calculated using cradle-to-gate emission factors for the relevant materials and are also listed in Table 6, which also reports the total use phase carbon footprint for each model as the sum of electricity related and maintenance related emissions.

Table 6.

Recovery rate and recovery energy consumption.

3.4. End-of-Life Material Recovery and Treatment

At the end of life, battery electric vehicles are dismantled and their materials are routed either to recycling or to final disposal. The main recoverable streams are metals, plastics and glass [13,26]. In this study, the inventory focuses on metal recycling, while traction batteries are excluded because large scale recycling technologies and consistent inventory data are not yet available. A mass loss rate of 2% is assumed during dismantling and handling, so that 98% of the vehicle mass is available for recycling [27]. Recovered metals are treated mainly through smelting, and the associated energy use and emissions are determined for each metal type and recycling route.

The end-of-life inventory therefore records, for each vehicle, the masses of individual metals, the adopted recycling rates, and the energy use and greenhouse gas emissions of recycling operations, together with the reduction in life cycle emissions when recycled metals substitute primary metal production. These data complete the system wide inventory and provide the basis for quantifying the contribution of end-of-life treatment to the life cycle carbon performance of the three battery electric vehicles [28].

4. Discussion

4.1. Vehicle Carbon Emissions Analysis

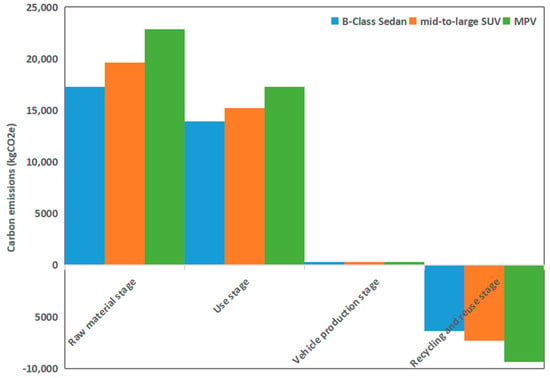

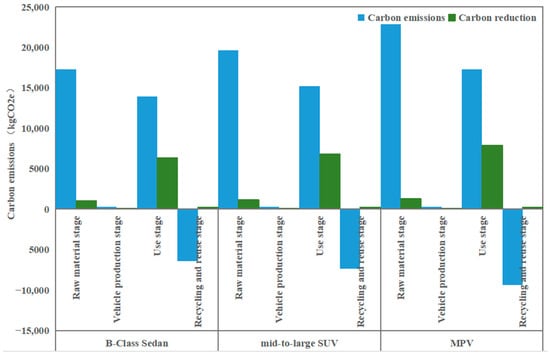

This section quantifies and compares the life cycle carbon footprints of the three battery electric vehicle segments and, on that basis, establishes segment-specific benchmarks within a single, internally consistent manufacturing context. The analysis directly targets the first research gap identified in the introduction: previous studies rarely compared multiple battery electric vehicle types from the same manufacturer, using the same body concept and battery chemistry, under a unified life cycle model. Over a lifetime driving distance of 150,000 km, total life cycle emissions from production to end-of-life increase from 25.12 tCO2e for the B-class sedan to 27.81 tCO2e for the sport utility vehicle and 31.06 tCO2e for the multi-purpose vehicle, as shown in Figure 2. The carbon footprint results of BEVs vary in different studies, but the carbon dioxide emissions of BEVs are basically between 160 and 230 gCO2e/km [29,30]. This band is in line with recent life cycle assessments of battery electric passenger cars and clearly lower than typical values reported for comparable internal-combustion vehicles, which indicates that, even under the current Chinese power mix, the three battery electric vehicles already deliver a substantial reduction in life cycle carbon intensity at the segment level.

Figure 2.

Carbon emissions at different phases for three BEV models.

The assumption of lifetime driving distance is a critical factor influencing carbon intensity results. Taking the sedan model as an example, a sensitivity analysis shows that when the lifetime driving distance is set to 100,000 km, 150,000 km, and 200,000 km, the carbon emissions per kilometer are 251.20 gCO2e, 167.46 gCO2e, and 125.60 gCO2e, respectively. While extending vehicle life lowers per-kilometer emissions, Nguyen-Tien et al. [5] highlight that excessively long lifespans may require battery replacements due to degradation. Given that standard warranties for new EVs typically cover 8 years or 160,000 km (approx. 100,000 miles), and that car owners are unwilling to bear the cost of replacing the power battery, we retained 150,000 km as the functional unit. This assumption represents a realistic maximizing of the original battery’s utility within its guaranteed performance period.

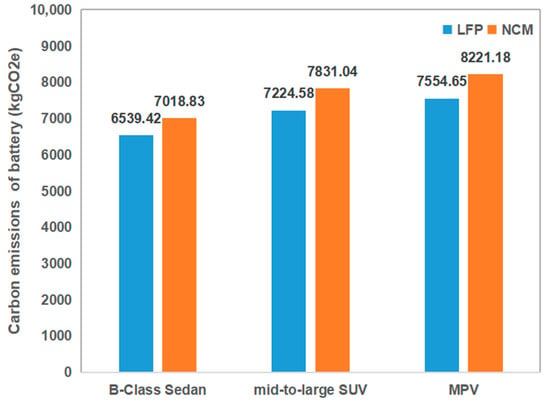

Regarding battery chemistry, this study focuses on LFP batteries. While Nickel Cobalt Manganese (NCM) batteries offer a weight advantage—Shen et al. [31] noted that an LFP pack (449 kg) is significantly heavier than an equivalent NCM811 pack (283 kg) for 77.4 kWh—the carbon footprint factors of NCM cathode materials are considerably higher [14]. Consequently, as shown in Figure 3, for the same vehicle segment and capacity, the NCM battery pack results in higher absolute manufacturing emissions compared to LFP, outweighing the benefits of lightweighting in the production phase. Furthermore, considering that LFP batteries accounted for 76.3% of the Chinese market share in 2023 [32], the selection of LFP in this study ensures the results are representative of the dominant technology in the world’s largest EV market.

Figure 3.

Carbon emission comparison of LFP battery vs. NCM battery.

The decomposition by life cycle phase in Figure 2 reveals a strongly skewed emission structure. For all three models, upstream raw material supply and the use phase together account for more than 90% of total life cycle emissions, while vehicle assembly and end-of-life treatment contribute only a minor share. Before recycling is taken into account, raw material production contributes slightly more than half of the total footprint, reflecting the carbon-intensive manufacture of traction batteries, aluminum-rich body structures and other metal-intensive components. The use phase contributes slightly less than half and is driven almost entirely by electricity generation in a power system that still relies heavily on fossil fuels. When end-of-life metal recycling is included, the net footprint is reduced by roughly 20%, because the recovery of steel, aluminum, and copper displaces a significant fraction of primary metal production. The concentration of emissions in upstream materials and electricity use, combined with a sizeable recycling credit, shows that three levers are central to further decarbonization of battery electric vehicles: higher material efficiency and lightweight design on the vehicle side, a lower-carbon electricity supply on the system side, and robust recycling systems that realize the mitigation potential of secondary metals.

Across the three segments, total life cycle emissions rise with vehicle size, yet the relative contributions of raw material supply, vehicle production, use phase, and end-of-life treatment remain broadly similar. The three cars in this study used the same set of background data, their relative rankings will not change, and the conclusions remain reliable. Segment differences therefore manifest primarily in the absolute level of emissions, while the overall shape of the life cycle profile is governed by common structural features such as battery technology, body concept, and electricity mix. The aggregate benchmarks reported in Figure 2 thus provide a coherent starting point rather than a complete explanation. The next subsection turns to the internal composition of the raw material phase and to the normalization by interior volume and curb mass, in order to reveal segment-specific differences that are not visible from total life cycle emissions alone and to identify additional opportunities for low-carbon vehicle design.

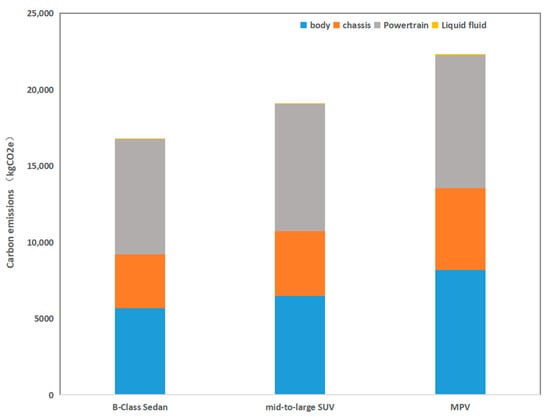

4.2. Analysis of Cabon Emissions at Different Phase

This section deepens the phase-wise analysis by focusing on the raw material and use phases that dominate the life cycle profiles in Figure 2. The objective is to clarify how upstream emissions are structured across vehicle systems and segments, and to introduce functional metrics that enable a more meaningful comparison among the three vehicle types. The raw material phase is decomposed into four systems: body, chassis, powertrain, and fluids. For all three vehicles, the powertrain is the single largest contributor and accounts for nearly half of upstream emissions, as illustrated in Figure 4. This reflects the energy-intensive production of traction batteries, including electrolyte salts and high-purity metals, as well as the extensive use of aluminum in battery enclosures and related structures. The chassis and body each contribute on the order of one-fifth to one-third of raw material emissions, while fluids such as brake fluid and refrigerant represent only a marginal share. Total raw material emissions increase with vehicle size, yet the fraction attributed to the powertrain decreases from the sedan to the sport utility vehicle and to the multi-purpose vehicle because battery capacity and mass do not scale in direct proportion to vehicle curb weight [33]. These patterns indicate that upstream emissions are governed by the interaction between battery design, metal intensity in the structure, and overall vehicle size.

Figure 4.

Carbon emissions from the raw materials phase of the three BEV models.

To compare segments on a more functional basis, the analysis applies normalized indicators that relate emissions and energy use to interior space and vehicle mass. When raw material emissions are divided by interior volume, the sedan, sport utility vehicle, and multi-purpose vehicle yield values of about 1280, 1240, and 1220 kgCO2e/m3, respectively. Emissions per unit volume therefore decline as vehicle size increases, which means that the multi-purpose vehicle, although it has the highest absolute upstream footprint, imposes the lowest carbon burden per unit of usable interior space. Given that this model can carry up to seven occupants, high-occupancy trips can achieve a lower upstream footprint per passenger than the smaller vehicles. The CO2 emission index relative to the vehicle’s body volume is theoretical and is used only sporadically in practice. A similar picture emerges when operational energy use is normalized by curb mass. The energy consumption per 100 km and per kilogram of curb weight is approximately 0.0061 kWh for the sedan, 0.0062 kWh for the sport utility vehicle, and 0.0061 kWh for the multi-purpose vehicle. The sport utility vehicle therefore has the highest energy use per unit mass, while the multi-purpose vehicle performs slightly better than the sedan. These results show that segment rankings depend on the metric used; in absolute terms, the multi-purpose vehicle has the highest emissions, but when evaluated per unit volume or per unit mass it performs competitively, which supports the use of multiple functional indicators when assessing climate efficiency across vehicle classes and when designing segment-specific mitigation strategies [34].

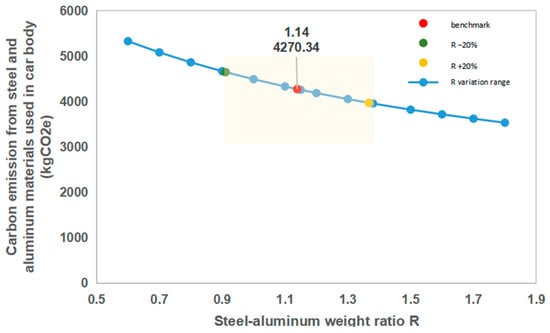

All three cars feature a steel–aluminum hybrid body. Considering the differences in design philosophies among the OEMs, this analysis deeply examines how the total carbon emissions of these two materials change when the weight ratio of steel-to-aluminum varies in the sedan. As shown in Figure 5, assuming the total weight of the materials remains constant, the steel-to-aluminum weight ratio R at the benchmark point is 1.14. When R varies within ±20%, carbon emissions will also change accordingly; the larger the R value, the lower the total carbon emissions. It is well known that aluminum has a carbon footprint factor 4–6 times higher than that of steel, but aluminum is 40–60% lighter than steel. This indicates that, when designing vehicle body materials, OEMs should comprehensively consider both weight and carbon emissions, using relatively appropriate weight steel materials [35].

Figure 5.

Carbon emission change with varying steel-to-aluminum weight ratio.

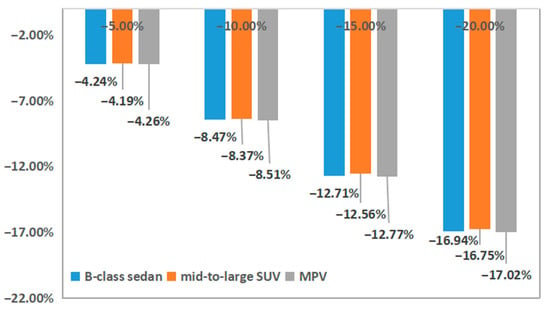

The influence of system-level conditions on the use phase is examined through the sensitivity to electricity carbon intensity. A reduction in the grid emission factor by 5 to 20% leads to an almost proportional decrease in use-phase emissions, with reductions in that phase ranging from about 4.2% to 17.0%, as illustrated in Figure 6. The response is close to linear over the explored range, which confirms that the grid emission factor is the dominant driver of operational emissions for all three vehicles. This finding reinforces the conclusion that decarbonizing electricity supply is essential for unlocking the full mitigation potential of battery electric vehicles, irrespective of segment.

Figure 6.

Sensitivity analysis of carbon emissions during the use phase and electricity carbon intensity.

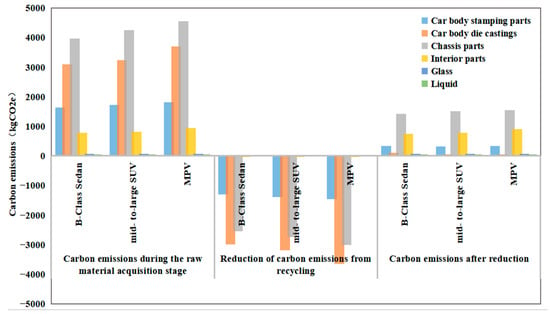

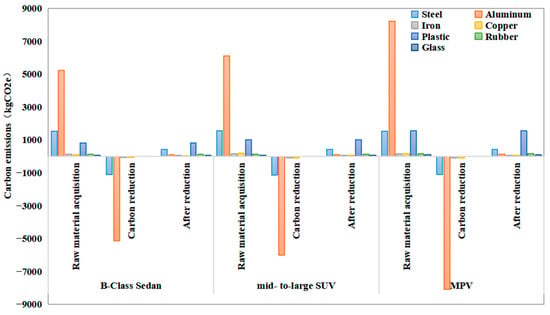

The role of material recycling in reshaping upstream emissions is shown in Figure 7 and Figure 8. Metal-rich components such as the body-in-white, chassis assemblies, and exterior structures exhibit large absolute reductions when steel and aluminum are recycled, whereas interior components show much smaller improvements because they consist of complex mixtures of plastics, textiles, and other non-metallic materials with low recovery rates. After recycling, residual raw material emissions are concentrated in steel, plastics and rubber. This pattern indicates that further reductions in the raw material phase will depend not only on higher recycling rates for metals but also on new design and process options that improve the recyclability of interior and other non-metallic parts. These observations close the gap between the baseline life cycle profiles and the mitigation strategies considered in Section 4.3, where cleaner electricity and advanced recycling are evaluated jointly at the vehicle level.

Figure 7.

Carbon emissions of key components after recycling and reuse of different vehicle models.

Figure 8.

Carbon emissions from recycled raw materials of different vehicle models.

It is crucial to specifically address the recycling dynamics of automotive plastics, which constitute a significant portion (over 10%) of the vehicle mass in this study. Unlike the well-established recovery loops for steel and aluminum, the decarbonization potential of plastics is currently constrained by technical and systemic barriers. As highlighted by Weise et al. [36], the effective recycling of automotive plastics is limited by the dispersed application of various polymer grades across complex vehicle subsystems and the lack of mature, standardized recovery networks. Furthermore, current mechanical recycling technologies are energy-intensive and often result in downcycling, yielding lower carbon reduction benefits compared to primary material substitution. Due to these factors, the emission reductions observed for plastic-intensive interior components are minimal in the current assessment. This study therefore prioritizes metal recovery in the mitigation scenarios, noting that significant future reductions in the plastic domain will require advancements in chemical recycling and improved material sorting infrastructures.

4.3. Considering Carbon Reduction and Emission Reduction Secenarios

The scenario analysis builds on the baseline life cycle profiles by exploring how future changes in the power system and in battery end-of-life management could reshape the carbon footprint of the three vehicles. The focus is on two mitigation strategies that are both realistic and highly relevant for the coming decade.

The first scenario assumes a cleaner power grid by 2030 [37], consistent with national plans for expanding low-carbon electricity. The Chinese cumulative installed capacity of wind and solar power continued to grow rapidly from 2022 to 2024 according to data released by authoritative departments. By the end of 2024, the total installed capacity of wind and solar power had exceeded 1400 GW, following a decrease in the national average carbon emission factor for electricity from 0.6205 in 2023 to 0.5777 in 2024 [38,39]. Based on this trajectory, we adjusted the background electricity dataset to a projected emission factor of 0.31 kg CO2e/kWh for the 2030 timeframe [20].

Under this assumption, total life cycle emissions per vehicle fall by about 30% relative to the baseline. The largest absolute and relative reductions occur in the use phase, where emissions decrease by 45.3% for the sedan, 44.8% for the sport utility vehicle, and 45.5% for the multi-purpose vehicle. Smaller but still meaningful reductions are observed in the raw material and vehicle production phases because many material and manufacturing processes draw electricity from the grid. In those phases, emissions decline by around 5% to 15% when the lower-carbon electricity mix is applied. The ordering of segments by total life cycle emissions remains unchanged; larger vehicles still emit more in absolute terms.

Material-recovery technology in lithium-ion battery mainly involves traditional pyrometallurgical and hydrometallurgical technologies. Pyrometallurgy technology is relatively easy to achieve. However, it consumes a lot of energy and the quality and recovery efficiency of material recovery are not high. Hydrometallurgical technology offers better recovery efficiency, lower energy consumption, and causes slightly less direct pollution to the environment compared to pyrometallurgy. Currently, most research results are obtained in the laboratory, realizing industrial application needs further exploration.

The second scenario assumes a large-scale implementation of physical recycling for lithium iron phosphate battery packs with high recovery rates of key metals. The battery-recycling scenario considers route combining physical pretreatment with hydrometallurgical recovery for lithium iron phosphate packs, in which aluminum and copper from the battery system are recovered at rates close to 97%, while lithium recovery remains limited in the near term [40]. The recycling process itself consumes electricity and generates on the order of 1300 to 1500 kg CO2e, but it also displaces the production of primary metals. The net effect is that roughly 75% to 80% of the raw material emissions of the battery system can be avoided. When this improvement is embedded in the full vehicle life cycle, total emissions per vehicle decline by approximately 15% to 18%, with the multi-purpose vehicle showing the largest absolute reduction because it contains the largest battery. In relative terms, the reduction rates of the sedan and the sport utility vehicle are slightly higher, since the battery represents a larger share of their upstream footprint.

Combining the two hypothetical scenarios above, Figure 9 compares the resulting life cycle emissions with the baseline case without targeted low-carbon measures. Taken together, the scenarios address the third research challenge identified in the introduction, which is the lack of integrated assessments that quantify, within a single model and across several battery electric vehicle segments, the mitigation potential of grid decarbonization and enhanced recycling.

Figure 9.

Carbon emissions from different types of BEVs in 2030.

These results indicate that grid decarbonization and advanced battery recycling act as complementary strategies [41]. A cleaner grid primarily reduces use phase and electricity-related emissions, while high-quality recycling reduces the upstream burden of battery materials. Coordinating both measures is therefore essential if battery electric vehicles are to reach the deeper levels of life cycle decarbonization implied by long-term climate goals, and it directly addresses the remaining research gap concerning the joint evaluation of grid decarbonization and advanced recycling within a single, segment-resolved framework.

The scenario nevertheless shows that decarbonization of the power sector is the dominant driver of future emission reductions for all three battery electric vehicles, even if their technical characteristics were to remain otherwise unchanged, and it therefore sets the boundary conditions within which vehicle-level design improvements need to operate.

5. Conclusions

In this study, a comprehensive life-cycle carbon accounting framework was developed to quantify greenhouse gas emissions for three battery electric vehicle segments (sedan, SUV, and MPV). All models originate from a single manufacturer and share a unified design and production platform, enabling consistent cross-segment comparison. The assessment integrates primary design specifications, detailed bills of materials, plant-level manufacturing data, and regionally representative electricity carbon intensities. Emissions were characterized across the full vehicle life cycle, including raw material extraction, component and vehicle manufacturing, battery production, use phase electricity consumption, and end-of-life treatment. Material-specific end-of-life assumptions were applied to estimate the mitigation potential from substituting recycled for primary metals. The analysis follows ISO 14067 and adopts a functional unit of one vehicle driven for 150,000 km, consistent with the lifetime assumption justified in this study [15,17].

Using this model, three main findings emerge. (1) Total life cycle emissions increase from the sedan to the SUV and MPV. When normalized by vehicle utility, the MPV shows lower carbon intensity. (2) Before recycling credits, raw materials and the use phase dominate. Metal recycling reduces upstream emissions, but the benefit is limited by the low recovery of polymer-rich parts. (3) Electricity decarbonization reduces total life cycle emissions by ~30%. Battery recycling provides a further ~15–18% reduction under the stated recovery assumptions.

Importantly, electrochemical battery manufacturing remains a CO2-emitting process, and recycling credits do not eliminate these process emissions. Further reductions therefore require both cleaner electricity and lower energy intensity in battery (cell) manufacturing, in addition to improved material recovery. Overall, electricity decarbonization is the most influential system lever because it simultaneously reduces emissions in manufacturing, vehicle operation and recycling. From a policy perspective, accelerating the deployment of low-carbon electricity is a prerequisite for realizing the mitigation potential quantified here and for embedding electric mobility within broader national decarbonization strategies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.Z.; Methodology, Y.L.; Investigation, Y.Z.; Data curation, Y.Z.; Formal analysis, J.Z.; Writing—original draft, Y.Z.; Writing—review & editing, J.Z. and Y.L.; Supervision, Y.L.; Funding acquisition, Y.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Hubei Province of China, grant number 2023AFB1062.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the Public Affairs Department of Guangzhou Xiaopeng Motors Technology Co., Ltd.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Yan Zhu and Jie Zhang were employed by the company Guangzhou Xiaopeng Motors Technology Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. The authors declare that this study received funding from Guangzhou Xiaopeng Motors Technology Co., Ltd. The funder was not involved in the study design, collection, analysis, interpretation of data, the writing of this article or the decision to submit it for publication.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BEV | Battery Electric Vehicle |

| ICEV | Internal Combustion Engine Vehicle |

| SUV | Sport Utility Vehicle |

| MPV | Multi-Purpose Vehicle |

| LCA | Life Cycle Assessment |

| LFP | Lithium Iron Phosphate |

| NCM | Nickel Cobalt Manganese |

| OEM | Original Equipment Manufacturer |

| GHG | Greenhouse Gas |

| CO2-eq | Carbon Dioxide Equivalent |

| ISO | International Organization for Standardization |

| CNTNRC | China Automotive Technology and Research Center Co., Ltd. |

| GWP | Global Warming Potential |

References

- Šimaitis, J.; Lupton, R.; Vagg, C.; Butnar, I.; Sacchi, R.; Allen, S. Battery electric vehicles show the lowest carbon footprints among passenger cars across 1.5–3.0 °C energy decarbonisation pathways. Commun. Earth Environ. 2025, 6, 476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dua, R. Net-zero transport dialogue: Emerging developments and the puzzles they present. Energy Sustain. Dev. 2024, 82, 101516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dua, R.; Almutairi, S.; Bansal, P. Emerging energy economics and policy research priorities for enabling the electric vehicle sector. Energy Rep. 2024, 12, 1836–1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira da Costa, V.B.; Bitencourt, L.; Dias, B.H.; Soares, T.; Bessa de Andrade, J.V.; Bonatto, B.D. Life cycle assessment comparison of electric and internal combustion vehicles: A review on the main challenges and opportunities. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2025, 208, 114988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen-Tien, V.; Zhang, C.; Strobl, E.; Elliott, R.J.R. The closing longevity gap between battery electric vehicles and internal combustion vehicles in Great Britain. Nat. Energy 2025, 10, 354–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, Ö.; Börjesson, P. The greenhouse gas emissions of an electrified vehicle combined with renewable fuels: Life cycle assessment and policy implications. Appl. Energy 2021, 289, 116621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, P.; Garcia, R.; Kulay, L.; Freire, F. Comparative life cycle assessment of lithium-ion batteries for electric vehicles addressing capacity fade. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 229, 787–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhao, F.; Hao, H.; Liu, Z. Life Cycle Emissions of Passenger Vehicles in China: A Sensitivity Analysis of Multiple Influencing Factors. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Champeecharoensuk, T.; Saisirirat, P.; Chollacoop, N.; Vithean, K.; Thapmanee, K.; Silva, K.; Champeecharoensuk, A. Global warming potential and environmental impacts of electric vehicles and batteries in Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). Energy Sustain. Dev. 2025, 86, 101723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abhiraman, V.J.; Khandelwal, N.; Krishnaiah, R.; Behera, S.K.; Kumar, A. Comparative life cycle assessment of lithium iron phosphate and nickel manganese cobalt batteries for electric vehicles: An Indian perspective. Energy Sustain. Dev. 2025, 89, 101837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zajemska, M.; Biniek-Poskart, A.; Skibiński, A.; Skrzyniarz, M.; Rzącki, J. A Narrative Review of Life Cycle Assessments of Electric Vehicles: Methodological Challenges and Global Implications. Energies 2025, 18, 5704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Can Sener, S.E.; Van Emburg, C.; Jones, M.; Bogucki, T.; Bonilla, N.; Ijeoma, M.W.; Wan, H.; Carbajales-Dale, M. Electric light-duty vehicles have decarbonization potential but may not reduce other environmental problems. Commun. Earth Environ. 2024, 5, 476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.C.; Deng, C.N.; Shen, P.; Qian, Y.; Xie, M. Environmental impact and carbon footprint analysis of battery electric vehicles based on life cycle assessment. Environ. Sci. Res. 2023, 36, 2179–2188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.S.; Hao, Z.; Lan, L.B.; Fu, P.; Chen, H. Research on energy saving and carbon reduction over the life cycle of battery electric vehicles with different power batteries. Chin. J. Automot. Eng. 2022, 12, 517–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 14067:2018; Greenhouse Gases—Carbon Footprint of Products—Requirements and Guidelines for Quantification. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018.

- ISO 14040/44: 2006; Environmental Management—Life Cycle Assessment—Principles and Framework. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006.

- Wu, Z.X.; Wang, M.; Zheng, J.H.; Sun, X.; Zhao, M.N.; Wang, X. Life cycle greenhouse gas emission reduction potential of battery electric vehicle. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 190, 462–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendziņš, K.; Barisa, A. Electric vs. Internal Combustion Vehicles: A Multi-Regional Life Cycle Assessment Comparison for Environmental Sustainability. Environ. Clim. Technol. 2024, 28, 855–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, X.; Li, P. A Review of the Life Cycle Assessment of Electric Vehicles: Considering the Influence of Batteries. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 814, 152870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, X.P.; Nie, H.H.; Gao, M.; Wu, F.B. Carbon emissions from electric vehicles throughout their life cycle. Energy Storage Sci. Technol. 2023, 12, 976–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Song, C.; Yuan, R. CO2 emissions from electricity generation in China during 1997–2040: The roles of energy transition and thermal power generation efficiency. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 773, 145026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- China Automobile Data Co., Ltd. China Automotive Life Cycle Assessment Database (CALCD—2021); China Automotive Life Cycle Assessment Database: Tianjin, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Karagoz, S.; Aydin, N.; Simic, V. End-of-life vehicle management: A comprehensive review. J. Mater. Cycles Waste Manag. 2020, 22, 416–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Announcement Regarding the Release of 2023 Electricity Carbon Footprint Factor Data. Available online: https://www.hunan.gov.cn/zqt/zcsd/202501/t20250124_33574554.html (accessed on 17 January 2025).

- Shafique, M.; Azam, A.; Rafiq, M.; Luo, X. Life cycle assessment of electric vehicles and internal combustion engine vehicles: A case study of Hong Kong. Res. Transp. Econ. 2022, 91, 101112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argonne National Laboratory. The Greenhouse Gases, Regulated Emissions, and Energy Use in Transportation (GREET) Model; Version 1.5; US Department of Energy: Washington, DC, USA, 1999; Available online: https://greet.es.anl.gov/publication-h3k81jas (accessed on 20 September 2023).

- Zhao, F.Q.; Liu, X.L.; Zhang, H.Y.; Liu, Z.W. Automobile industry under China’s carbon peaking and carbon neutrality goals: Challenges, opportunities, and coping strategies. J. Adv. Transp. 2022, 2022, 5834707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Ji, J.P.; Ma, X.M. Greenhouse gas emissions reduction from battery electric automobile: A study based on EIO-LCA model. China Environ. Sci. 2012, 32, 947–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Z.Y.; Wang, L.; Huang, K.; Liu, L.; Yu, Y. Analysis of carbon neutrality potential of power batteries for new energy vehicles. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 36, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, Q.Y.; Zhao, F.Q.; Liu, Z.W.; Jiang, S.; Hao, H. Cradle-to-gate greenhouse gas emissions of battery electric and internal combustion engine vehicles in China. Appl. Energy 2017, 204, 1399–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, M.; Cha, J.; Song, J. Impact of lightweighting and driving conditions on electric vehicle energy consumption: In-depth analysis using real-world testing and simulation. Energy 2025, 323, 135746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.; Zhou, J.; Hu, J.; Shang, Z.; Zhou, X.; Xu, S. Exploring the energy and environmental sustainability of advanced lithium-ion battery technologies. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2025, 212, 107963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, X.; Guo, Y.F.; Yang, W.X.; Wei, K.; Zhu, G. Life cycle assessment of the environmental impact of the batteries used in battery electric passenger cars. Energy Rep. 2021, 7, 2302–2315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Pero, F.; Delogu, M.; Pierini, M. Life Cycle Assessment in the automotive sector: A comparative case study of Internal Combustion Engine (ICE) and electric car. Procedia Struct. Integr. 2018, 12, 521–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palazzo, J.; Geyer, R. Consequential life cycle assessment of automotive material substitution: Replacing steel with aluminum in production of north American vehicles. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2019, 75, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weise, S.; Ali, A.R.; Cerdas, F.; Herrmann, C. Determination of circular economy targets based on absolute sustainability: A case study on plastics. Procedia CIRP 2024, 122, 743–747. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Global Energy Interconnection Development and Cooperation Organization. Research on China’s 2030 Energy and Power Development Plan and Outlook for 2060; Global Energy Interconnection Development and Cooperation Organization: Beijing, China, 2021; Available online: https://www.geidco.org.cn/2021/0318/3268.shtml (accessed on 18 March 2022).

- Status of Renewable Energy Grid Connection and Operation in 2024. Available online: https://www.nea.gov.cn/20250221/e10f363cabe3458aaf78ba4558970054/c.html (accessed on 17 January 2025).

- Announcement Regarding the Release of 2024 Electricity Carbon Footprint Factor Data. Available online: https://www.mee.gov.cn/xxgk2018/xxgk/xxgk01/202510/t20251024_1130734.html (accessed on 17 January 2025).

- Li, L.; Li, Y.; Zhang, G. Summary of Pretreatment of Waste Lithium-Ion Batteries and Recycling of Valuable Metal Materials: A Review. Separations 2024, 11, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, J.F.; Baumann, M.; Zimmermann, B.; Braun, J.; Weil, M. The environmental impact of Li-Ion batteries and the role of key parameters—A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 67, 491–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.