The Social Aspects of Energy System Transformation in Light of Climate Change—A Case Study of South-Eastern Poland in the Context of Current Challenges and Findings to Date

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. The European Way and Energy Transition Instruments

2.2. Systemic and Social Constraints of Poland’s Energy Transition

2.3. Societal Aspects of the Transition and the Rural Population’s Awareness

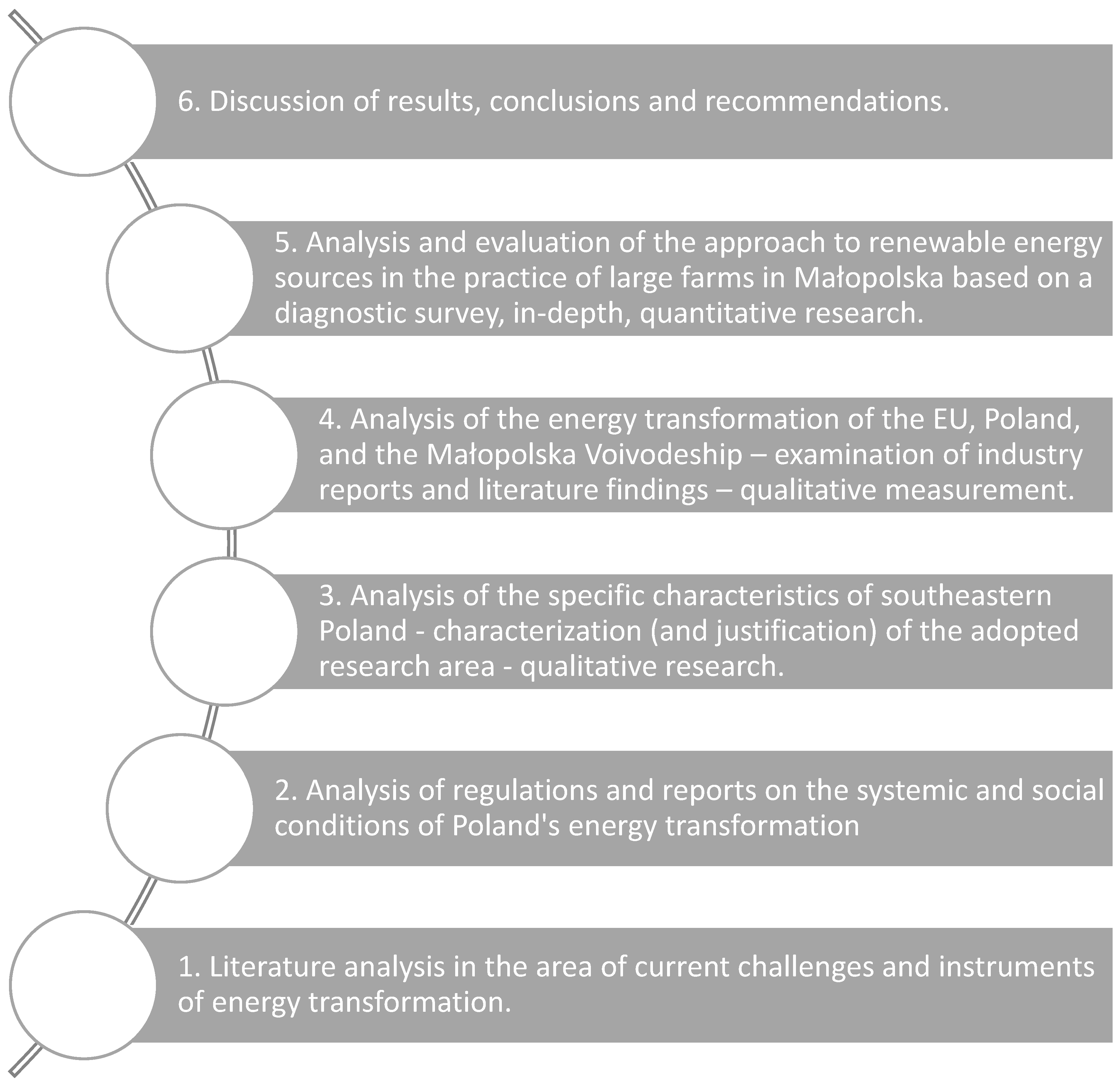

3. Materials and Methods

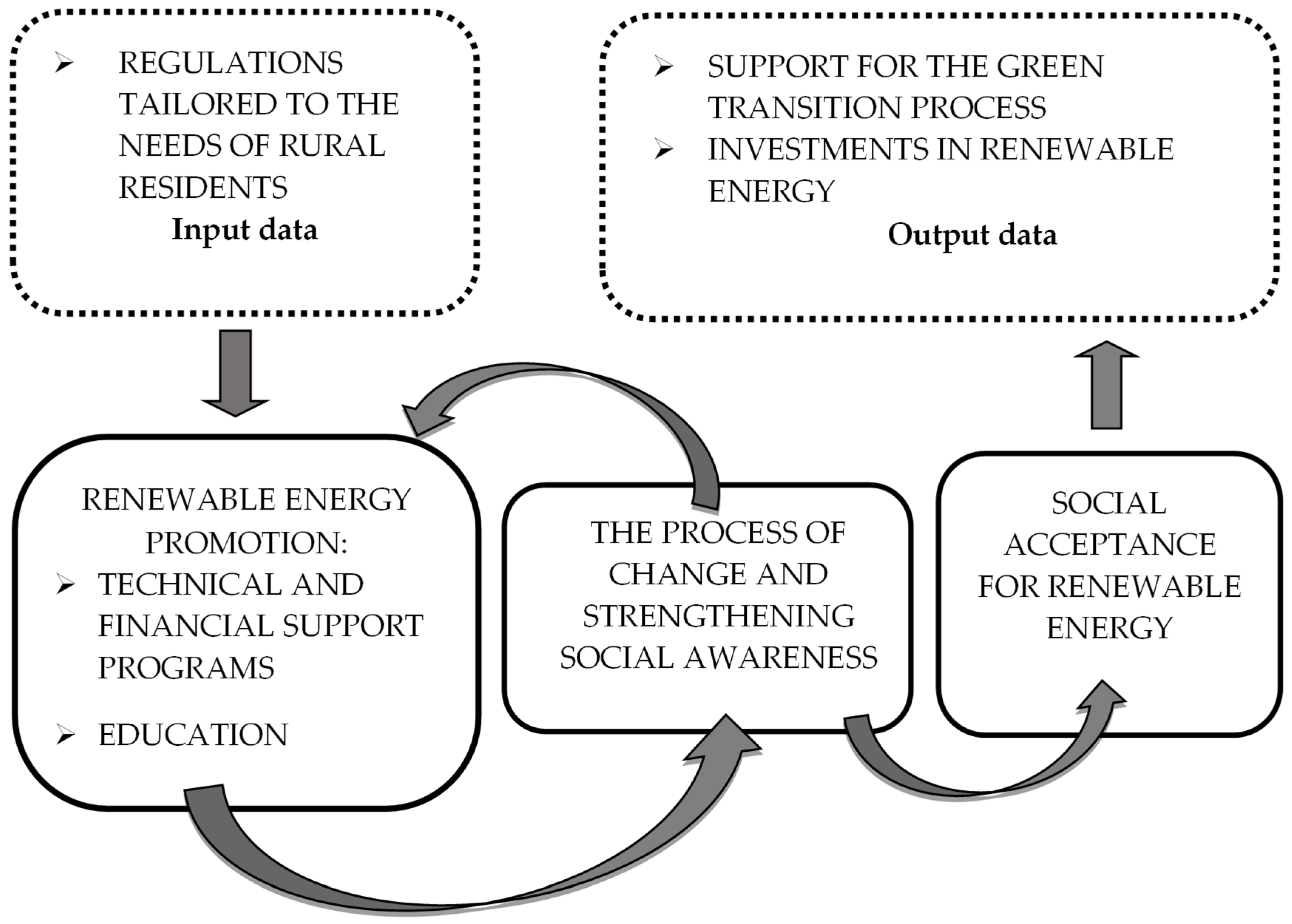

Research Concept and Hypotheses

- appropriate regulations,

- support programmes (financial and technical),

- education,

4. Results

4.1. Characteristics of Southeastern Poland as a Study Area

4.2. Energy Transitions in the EU, Poland, and Małopolskie Voivodeship According to Expert Reports and Literature

4.3. Analysis of Attitudes Towards Renewables in Rural Households in the Małopolskie Voivodeship: Survey Results and In-Depth Interviews

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- IPCC. AR6 WGIII: Summary for Policymakers; Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- IEA. World Energy Outlook 2024; International Energy Agency: Paris, France, 2024.

- Abo Elassal, D.; Jabareen, Y. Understanding Urban Adaptation Policy and Social Justice: A New Conceptual Framework for Just-Oriented Adaptation Policies. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EEA. Trends and Projections in Europe 2024; European Environment Agency: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- IRENA. Renewable Energy Capacity Statistics 2024; International Renewable Energy Agency: Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Zupok, S.; Chomać-Pierzecka, E.; Dmowski, A.; Dyrka, S.; Hordyj, A. A Review of Key Factors Shaping the Development of the U.S. Wind Energy Market in the Context of Contemporary Challenges. Energies 2025, 18, 4224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurostat. Renewable Energy Statistics—Statistics Explained (EU-27); European Commission: Luxembourg, 2024; Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Renewable_energy_statistics (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- Kęsy, I.; Godawa, S.; Błaszczak, B.; Chomać-Pierzecka, E. Human Safety in Light of the Economic, Social and Environmental Aspects of Sustainable Development—Determination of the Awareness of the Young Generation in Poland. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chomać-Pierzecka, E. Economic, Environmental and Social Security in accordance with the Concept of Sustainable Development. Stud. Adm. i Bezpieczeństwa 2025, 18, 257–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEA. Energy Security: Overview; International Energy Agency: Paris, France, 2024.

- European Commission. Directive (EU) 2018/2001 on the Promotion of the Use of Energy from Renewable Sources (RED II); European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Recast Renewable Energy Directive (RED III); European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Directive (EU) 2019/944 on Common Rules for the Internal Market for Electricity; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. BRIDGE Task Force on Energy Communities Report 2020–2021; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Handbook on Cross-Border Energy Communities; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- European Parliament & Council. Regulation (EU) 2018/1999 on the Governance of the Energy Union and Climate Action; European Parliament & Council: Brussels, Belgium, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Modernisation Fund—EU Instrument Under the EU ETS; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Just Transition Mechanism—Ensuring No One Is Left Behind; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- European Investment Bank. EIB Climate Survey: Attitudes Towards the Green Transition; European Investment Bank: Luxembourg, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Drożdż, W.; Mróz-Malik, O.; Kopiczko, M. The Future of the Polish Energy Mix in the Context of Social Expectations. Energies 2021, 14, 5341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drożdż, W.; Kinelski, G.; Czarnecka, M.; Wójcik-Jurkiewicz, M.; Maroušková, A.; Zych, G. Determinants of Decarbonization—How to Realize Sustainable and Low Carbon Cities? Energies 2021, 14, 2640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. EU Energy Poverty Observatory—2022 Annual Report; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Economic Survey of Poland 2023; OECD: Paris, France, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- EEA. Europe’s Climate and Energy Profile: Regional Perspectives; European Environment Agency: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Frankowski, J. Transformacja Energetyczna w Polskiej Gminie. Skutki Polityki Lokalnej Opartej o Odnawialne Źródła Energii na Przykładzie Kisielic; Fundacja Friedrich Ebert Stiftung: Warszawa, Poland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Herudziński, T.; Swacha, P. Poles Towards Energy Transformation and Energy Sources—Sociological Perspective. Przegląd Politol. 2022, 4, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GUS. Energia ze Źródeł Odnawialnych w 2023 r.; Główny Urząd Statystyczny: Warszawa, Poland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Energy Communities—Transposition Guidance; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Climate and Environment (MKiŚ). Energy Policy of Poland Until 2040 (PEP 2040); MKiŚ: Warszawa, Poland, 2021.

- Ministerstwo Klimatu i Środowiska. Krajowy Plan na Rzecz Energii i Klimatu na Lata 2021–2030 (KPEiK); MKiŚ: Warszawa, Poland, 2019.

- Jędrych, E.; Klimek, D.; Rzepka, A. Social Capital in Energy Enterprises: Poland’s Case. Energies 2022, 15, 546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kud, K.; Woźniak, M.; Badora, A. Impact of the Energy Sector on the Quality of the Environment in the Opinion of Energy Consumers from Southeastern Poland. Energies 2021, 14, 5551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LIFE-IP Małopolska. Implementation of Air Quality Plan for the Małopolska Region—Małopolska in a Healthy Atmosphere; Małopolska Region: Kraków, Poland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Żak-Skwierczyńska, M. Energy Transition of the Coal Region and Challenges for Local and Regional Authorities: The Case of the Bełchatów Basin Area in Poland. Energies 2022, 15, 9621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szpor, A.; Ziółkowska, K. Energy Poverty in Poland: Drivers, Measurement and Policy Responses; IBS: Warszawa, Poland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Wójcik-Jurkiewicz, M.; Kinelski, G.; Drożdż, W. Energy Poverty Alleviation in the Era of Energy Transition—Case Study of Poland. Energies 2022, 15, 5481. [Google Scholar]

- Żuk, P. The Sense of Socio-Economic Threat and the Perception of Climate Challenges and Attitudes Towards Energy Transition Among Residents of Coal Basins: The Case of the Turoszów Basin in Poland; SSRN: Rochester, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Latosińska, J.; Miłek, D. The State of Knowledge and Attitudes of the Inhabitants of the Polish Świętokrzyskie Province about Renewable Energy Sources. Energies 2023, 16, 7445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chodkowska-Miszczuk, J.; Kola-Bezka, M.; Lewandowska, A.; Martinát, S. Local Communities’ Energy Literacy as a Way to Rural Resilience—An Insight from Inner Peripheries. Energies 2021, 14, 2575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozera, A.; Standar, A.; Stanisławska, J.; Rosa, A. Low-Carbon Rural Areas: How Are Polish Municipalities Financing the Green Future? Energies 2024, 17, 5316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, Ö.; Klepacka, A.; Florkowski, W. Achieving Renewable Energy, Climate, and Air Quality Policy Goals: Rural Residential Investment in Solar Panels. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 248, 109309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wüstenhagen, R.; Wolsink, M.; Bürer, M.J. Social Acceptance of Renewable Energy Innovation: An Introduction to the Cconcept. Energy Policy 2007, 35, 2683–2691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chomać-Pierzecka, E. Innovation as an Attribute of the Sustainable Development of Pharmaceutical Companies. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dóci, G.; Vasileiadou, E. “Let’s Do It Ourselves”: Individual Motivations for Investing in Renewables at Community Level. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 49, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simcoc, N.; Thomson, H.; Petrova, S.; Bouzarovski, S. Energy Poverty and Vulnerability: A Global Perspective; Routledge: London, UK, 2018; ISBN 978-1-138-66838-8. [Google Scholar]

- Giacovelli, G. Social Capital and Energy Transition: A Conceptual Review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Świdyńska, N.; Witkowska-Dąbrowska, M.; Jakubowska, D. Influence of Wind Turbines as Dominants in the Landscape on the Acceptance of the Development of Renewable Energy Sources in Poland. Energies 2024, 17, 3268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarębski, P.M.; Katarzyński, D.; Godlewska-Majkowska, H.; Komor, A.; Gawryluk, A. Wind Farms’ Location and Geographical Proximity as a Key Factor in Sustainable City Development: Evidence from Poland. Energies 2024, 17, 3447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikuła, B.; Lorens, P.; Ciesielski, M.; Nowak, M.J. Współczesne Wyzwania Związane z Kształtowaniem Systemu Planowania Miejscowego; Policy Brief 2021/3 Komitetu Przestrzennego Zagospodarowania Kraju Polskiej Akademii Nauk; Committee on Space and Satellite Research: Warszawa, Poland, 2021; ISBN 978-83-66847-22-4. [Google Scholar]

- Diestelmeier, L. Citizen Energy Communities as a Vehicle for a Just Energy Transition in the EU—Challenges for the Transposition. Oil Gas Energy Law Intell. 2021, 19, 1–14. Available online: https://pure.rug.nl/ws/portalfiles/portal/157207159/ov19_1_article03.pdf (accessed on 16 December 2025).

- European Investment Bank. The EIB Climate Survey. Citizens Call for Green Recovery; European Investment Bank: Luxembourg, 2022; Available online: https://www.eib.org/files/publications/the_eib_climate_survey_2021_2022_en.pdf (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- Kowalska, M.; Chomać-Pierzecka, E. Sustainable Development Through the Lens of Climate Change: A Diagnosis of Attitudes in Southeastern Rural Poland. Sustainability 2025, 17, 5568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawicka, B.; Barbaś, P.; Pszczółkowski, P.; Skiba, D.; Yeganehpoor, F.; Krochmal-Marczak, B. Climate Changes in Southeastern Poland and Food Security. Climate 2022, 10, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EEA Trends and Projections: EU Greenhouse Gas Emissions See Significant Drop in 2023. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/en/newsroom/news/eea-trends-and-projections (accessed on 16 October 2025).

- EEA. EU Greenhouse Gas Emissions Decreased to 37% Below 1990 Levels in 2023 (Preliminary); European Environment Agency: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Janikowska, O.; Generowicz-Caba, N.; Kulczycka, J. Energy Poverty Alleviation in the Era of Energy Transition—Case Study of Poland and Sweden. Energies 2024, 17, 5481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalczyk-Juśko, A. Program ”Energia dla Wsi” Wsparcie Rozwoju Odnawialnych Źródeł Energii na Obszarach Wiejskich; Centrum Doradztwa Rolniczego w Brwinowie: Radom, Poland, 2023. Available online: https://cdr.gov.pl/images/Radom/pliki/oze/CDR2_ks_v2.pdf (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- National Energy Regulatory Office. National Report of the President of URE; National Energy Regulatory Office: Warszawa, Poland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Kilinc-Ata, N. The Evaluation of Renewable Energy Policies across EU Countries and US States: An Econometric Approach. Energy Sustain. Dev. 2016, 31, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haas, R.; Resch, G.; Panzer, C.; Busch, S.; Ragwitz, M.; Held, A. Efficiency and Effectiveness of Promotion Systems for Electricity Generation from Renewable Energy Sources—Lessons from EU Countries. Energy 2011, 36, 2186–2193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bäckstrand, K. Towards a Climate-Neutral Union by 2050? The European Green Deal, Climate Law, and Green Recovery. In Routes to a Resilient European Union; Bakardjieva Engelbrekt, A., Ekman, P., Michalski, A., Oxelheim, L., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shedding Light on Energy in Europe—2025 Edition, Eurostat, Interactive Publication, 2025. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/interactive-publications/energy-2025 (accessed on 2 November 2025).

- Clean Energy Wire. EU Surpasses 50% Renewable Power Share for the First Time in the First Half of 2024. Available online: https://www.cleanenergywire.org/news/eu-surpasses-50-renewable-power-share-first-time-first-half-2024 (accessed on 2 November 2025).

- Eurelectric Power Barometer 2025. In Shape for the Future. Available online: https://powerbarometer.eurelectric.org/ (accessed on 2 November 2025).

- Pietrzak, M.B.; Igliński, B.; Kujawski, W.; Iwański, P. Energy Transition in Poland—Assessment of the Renewable Energy Sector. Energies 2021, 14, 2046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kochanek, E. Poland’s Energy Transformation in the Context of the Challenges of the European Green Deal. Yearb. Inst. Cent. East. Eur. 2022, 20, 79–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanuch, M.; Firlej, K.A. Forecasting the Development of Electricity from Renewable Energy Sources in Poland Compared to EU Countries. Econ. Environ. 2023, 84, 30–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pepłowska, M. Climate Neutrality in Poland: The Role of the Coal Sector in Achieving the 2050 Goal. Polityka Energetyczna–Energy Policy J. 2025, 28, 113–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Energy Agency (IEA). World Energy Investment 2025; IEA: Paris, France, 2025; Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/world-energy-investment-2025 (accessed on 2 November 2025).

- Chomać-Pierzecka, E.; Kowalska, M.; Czyrka, K. The Problem of Transforming the Energy System Towards Renewable Energy Sources as Perceived by Inhabitants of Rural Areas in South-Eastern Poland. Energies 2025, 18, 5548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brożyński, B.W. Just Transition—The First Pillar of Poland’s Energy Policy until 2040: Legal, Economic and Social Aspects. Polityka Energetyczna–Energy Policy J. 2022, 25, 5–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, A.; Claeys, G.; Midões, C.; Tagliapietra, S. Just Transition Fund—How the EU Budget Can Best Help the Shift from Fossil Fuels to Sustainable Energy; European Parliament: Brussels, Belgium, 2020; Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/ (accessed on 2 November 2025).

- Nyga-Łukaszewska, H.; Aruga, K.; Stala-Szlugaj, K. Energy Security of Poland and Coal Supply: Price Analysis. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marciniuk-Kluska, A.; Ojdana-Kościuszko, M. Energy Transition—Challenges for Poland and Experiences of EU Member States. Manag. Adm. 2024, 62, 84–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. The European Green Deal; COM(2019) 640 Final; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- European Environment Agency (EEA). Environmental Statement Report 2022. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/en/analysis/publications/environmental-statement-report-2022. (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- Ember Climate. European Electricity Review 2024; Ember Climate: London, UK, 2024; Available online: https://ember-energy.org/app/uploads/2024/10/European-Electricity-Review-2024.pdf (accessed on 2 November 2025).

- Energy Regulatory Office (URE). Report on the Operation of the Electricity System in Poland 2023/2024; URE: Warsaw, Poland, 2024. Available online: https://www.ure.gov.pl (accessed on 2 November 2025).

- Maćkowiak-Pandera, J. Understanding EU’s and Poland’s Renewable Energy Goals; Forum Energii: Warszawa, Poland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Forum Energii. Energy Transition in Poland. Edition 2025. Available online: https://www.forum-energii.eu/en/transformacja-energetyczna-polski-edycja-2025 (accessed on 2 November 2025).

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report; World Meteorological Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Meteorology and Water Management (IMGW). Climate of Poland 2023: Annual Report; IMGW: Warsaw, Poland, 2023; Available online: https://imgw.pl/raport-imgw-pib-klimat-polski-2023/ (accessed on 12 November 2025).

- Malopolska Air. Summary of the Implementation of the Air Protection Program in the Malopolska Region 2023; Marshal’s Office of the Malopolska Region: Kraków, Poland, 2024; Available online: https://powietrze.malopolska.pl/ (accessed on 2 November 2025).

- Life Malopolska. Available online: https://klimat.ekomalopolska.pl/podsumowanie-wdrazania-rpddkie-w-malopolsce-w-roku-2022/ (accessed on 2 November 2025).

- Niemiec, M.; Komorowska, M.; Atilgan, A.; Abduvasikov, A. Labelling the Carbon Footprint as a Strategic Element of Environmental Assessment of Agricultural Systems. Agric. Eng. 2024, 28, 235–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sowiżdżał, A.; Tomaszewska, B.; Pająk, L.; Kaczmarczyk, M.; Luboń, W.; Pełka, G.; Hałaj, E.; Hajto, M.; Brawiak, K.; Chmielowska, A.; et al. Analysis of Renewable Energy Potential for the Malopolska Region; AGH University of Science and Technology/LIFE-Ekomałopolska: Kraków, Poland, 2024; Available online: https://klimat.ekomalopolska.pl/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/AGH_potencjal-OZE-w-Malopolsce.pdf (accessed on 2 November 2025).

- Polak, R.; Dziki, D.; Krzykowski, A.; Rudy, S.; Biernacka, B. RenewGeo: An Innovative Geothermal Technology Augmented by Solar Energy. Agric. Eng. 2025, 29, 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuchmacz, J.; Mika, Ł. Description of the Development of the Prosumer Energy Sector in Poland. Polityka Energetyczna–Energy Policy J. 2018, 21, 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gancarczyk, M.; Tomczyk, D.; Gancarczyk, J. Sustainable industrial transformation through entrepreneurial ecosystem governance: The case of Polish energy clusters. Przegląd Przedsiębiorczości i Ekon. 2025, 13, 95–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostecka-Jurczyk, D. Economic Conditions for the Development of Energy Cooperatives in Poland. Energies 2022, 15, 6831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wicki, L. Factors Determining the Development of Prosumer Photovoltaic Installations in Polish Regions. Energies 2022, 15, 5897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Śleszyński, P. How to Recognize the Threat of Social Energy Exclusion? Demographic and Settlement Determinants of Distributed Energy Development in Polish Towns and Cities. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2023, 98, 104780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikora, J.; Zimniewicz, K. Renewable energy sources as a way to prevent climate warming in Poland. Econ. Environ. 2023, 85, 456–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Public Opinion Research Centre. Report: Opinions on Wind Energy 2023. Available online: https://www.cbos.pl/SPISKOM.POL/2023/K_027_23.PDF (accessed on 7 October 2025).

- PSEW. Polacy Zdecydowanie Popierają Wprowadzane Zmiany, Które Uwolnią Wiatr na Lądzie. 14 July 2022. Available online: http://psew.pl/polacy-zdecydowanie-popieraja-wprowadzane-zmiany-ktore-uwolnia-wiatr-na-ladzie (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Piwowar, A.; Dzikuć, A. The Economic and Social Dimension of Energy Transformation in the Face of the Energy Crisis: The Case of Poland. Energies 2024, 17, 403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karpińska, L.; Śmiech, S. Conceptualising housing costs: The hidden face of energy poverty in Poland. Energy Policy 2020, 147, 111819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leszczyński, P.; Markiewicz, J.; Mądry, T.; Mierzejewski, M.; Ogórek, S.; Rybacki, J. Wpływ zmian klimatu na gospodarkę Polski na przykładzie wybranych miast wojewódzkich. In Working Paper; nr 4.; Polski Instytut Ekonomiczny: Warszawa, Poland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Kozera, A.; Standar, A.; Stanisławska, J.; Rosa, A. Investments in Renewable Energy in Rural Communes: An Analysis of Regional Disparities in Poland. Energies 2024, 17, 6185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roszak-Szyrocka, J.; Allahham, A.; Żywiołek, J.; Ali Turi, J.; Das, A. Expectations for renewable energy, and its impacts on quality of life in European Union countries. Manag. Syst. Prod. Eng. 2023, 31, 128–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conde, J.; Takano-Rojas, H. Rethinking energy transition: Approaches from social representations theory. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2025, 122, 104001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Höijer, B. Social representations theory: A new theory for media research. Nord. Rev. 2011, 32, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chomać-Pierzecka, E. Value as an economic category in the light of the multidimensionality of the concept ‘value’. Lang. Relig. Identity 2021, 24, 155–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lennon, B.; Dunphy, N.; Gaffney, C.; Revez, A.; Mullally, G.; O’Connor, P. Citizen or consumer? Reconsidering energy citizenship. J. Environ. Policy Plan. 2020, 22, 184–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Wadowicki | Miechowski | Krakowski | Limanowski | Tarnowski | TOTAL | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| strongly disagree | N | 3 | 5 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 16 |

| % | 5.00% | 8.30% | 3.30% | 6.70% | 3.30% | 5.30% | |

| disagree | N | 8 | 9 | 7 | 3 | 5 | 32 |

| % | 13.30% | 15.00% | 11.70% | 5.00% | 8.30% | 10.70% | |

| hard to say | N | 5 | 7 | 3 | 3 | 6 | 24 |

| % | 8.30% | 11.70% | 5.00% | 5.00% | 10.00% | 8.00% | |

| agree | N | 19 | 26 | 17 | 30 | 27 | 119 |

| % | 31.70% | 43.30% | 28.30% | 50.00% | 45.00% | 39.70% | |

| strongly agree | N | 25 | 13 | 31 | 20 | 20 | 109 |

| % | 41.70% | 21.70% | 51.70% | 33.30% | 33.30% | 36.30% |

| M | SD | |

|---|---|---|

| Wadowicki | 3.92 | 1.23 |

| Miechowski | 3.55 | 1.23 |

| Krakowski | 4.13 | 1.16 |

| Limanowski | 3.98 | 1.10 |

| Tarnowski | 3.97 | 1.04 |

| Total | 3.91 | 1.16 |

| Wadowicki | Miechowski | Krakowski | Limanowski | Tarnowski | TOTAL | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| It should be founded primarily on Poland’s hard coal reserves | N | 15 | 9 | 9 | 13 | 9 | 55 |

| % | 25.00% | 15.00% | 15.00% | 21.70% | 15.30% | 18.40% | |

| Coal-based energy production should be phased out and replaced with other energy sources | N | 34 | 27 | 42 | 32 | 34 | 169 |

| % | 56.70% | 45.00% | 70.00% | 53.30% | 57.60% | 56.50% | |

| hard to say | N | 11 | 24 | 9 | 15 | 16 | 75 |

| % | 18.30% | 40.00% | 15.00% | 25.00% | 27.10% | 25.10% |

| Wadowicki | Miechowski | Krakowski | Limanowski | Tarnowski | TOTAL | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Renewable energy sources | N | 24 | 26 | 36 | 33 | 29 | 148 |

| % | 42.10% | 43.30% | 60.00% | 55.00% | 49.20% | 50.00% | |

| Nuclear power | N | 22 | 11 | 13 | 11 | 15 | 72 |

| % | 38.60% | 18.30% | 21.70% | 18.30% | 25.40% | 24.30% | |

| Natural gas | N | 4 | 14 | 6 | 9 | 8 | 41 |

| % | 7.00% | 23.30% | 10.00% | 15.00% | 13.60% | 13.90% | |

| Coal | N | 7 | 7 | 4 | 7 | 7 | 32 |

| % | 12.30% | 11.70% | 6.70% | 11.70% | 11.90% | 10.80% | |

| Other | N | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| % | 0.00% | 3.30% | 1.70% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 1.00% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Kowalska, M.; Chomać-Pierzecka, E.; Kuboń, M.; Bogusz, M. The Social Aspects of Energy System Transformation in Light of Climate Change—A Case Study of South-Eastern Poland in the Context of Current Challenges and Findings to Date. Energies 2026, 19, 286. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19020286

Kowalska M, Chomać-Pierzecka E, Kuboń M, Bogusz M. The Social Aspects of Energy System Transformation in Light of Climate Change—A Case Study of South-Eastern Poland in the Context of Current Challenges and Findings to Date. Energies. 2026; 19(2):286. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19020286

Chicago/Turabian StyleKowalska, Magdalena, Ewa Chomać-Pierzecka, Maciej Kuboń, and Małgorzata Bogusz. 2026. "The Social Aspects of Energy System Transformation in Light of Climate Change—A Case Study of South-Eastern Poland in the Context of Current Challenges and Findings to Date" Energies 19, no. 2: 286. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19020286

APA StyleKowalska, M., Chomać-Pierzecka, E., Kuboń, M., & Bogusz, M. (2026). The Social Aspects of Energy System Transformation in Light of Climate Change—A Case Study of South-Eastern Poland in the Context of Current Challenges and Findings to Date. Energies, 19(2), 286. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19020286