1. Introduction

With the rapid advancement of electric vehicles, aerospace engineering, and high-end equipment manufacturing, requirements for thermal safety, energy efficiency, and reliability at the system level have become increasingly stringent. Consequently, thermal management systems are evolving toward highly integrated and efficient architectures [

1]. By deeply integrating multiple heat sources—such as batteries, electric motors, and passenger cabins—with compressors, expanders, and heat exchangers, an ITMS can achieve synergistic utilization of cold and heat sources within stringent space and weight constraints [

2,

3].

In such systems, the multi-way valve serves as a pivotal component. By enabling flexible switching and precise regulation of coolant flow channels, it directly determines the flow distribution among circuits, the response speed of thermal equilibrium, and the overall operational efficiency and safety of the system [

4,

5]. In advanced EV thermal management platforms, a single multi-way valve can facilitate rapid switching between various operating modes, including cooling, heating, and waste heat recovery. It provides active cooling or preheating for the battery pack, manages air conditioning and heating for the passenger cabin, and coordinates the motor cooling circuit, thereby significantly enhancing energy utilization efficiency and the vehicle’s driving range.

Current investigations into valve pressure drop and internal flow characteristics have predominantly focused on conventional configurations, such as four-way valves, spool valves, and globe valves. Conversely, research concerning multi-way valves with more complex structures remains relatively limited. Previous studies have established that the working fluid undergoes a significant pressure reduction in localized regions when passing through a valve. Specifically, Edvardsen et al. [

6] and Rahmatmand et al. [

7] experimentally investigated single-phase flow in globe valves and thermostatic mixing valves, respectively. Their findings indicated that abrupt changes in internal geometry are the primary cause of substantial pressure drops. Using numerical methods, Tripathi et al. [

8] compared two reversing valves with distinct structures, confirming that variations in the valve spool configuration result in significant differences in pressure drop characteristics. Furthermore, numerical simulations conducted by Ye et al. [

9] on needle valves demonstrated that the fluid experiences a drastic pressure drop within the throttling region when the valve opening is small. Experimental results from Hemamalini et al. [

10] further revealed that the maximum pressure drop in control valves can reach up to 68 times that of the pipeline, exhibiting an inversely proportional relationship with the valve opening. Synthesizing these findings, it is evident that pressure losses primarily occur in regions where the flow direction and cross-sectional area change abruptly; these losses generally decrease as the valve opening increases.

To enhance hydrodynamic performance and optimize pressure characteristics, researchers have extensively focused on the modification of key structural parameters, specifically by reconstructing flow channel topologies and wall curvatures to mitigate local losses or regulate pressure drops. Qian et al. [

11] optimized the length of the throttling gap, which ameliorated the internal flow field distribution, increased the pressure differential across the valve, and improved the overall throttling efficiency. Zhang et al. [

12] modified the internal valve profile from a linear to a circular arc configuration, effectively mitigating the sudden pressure surges observed under small opening conditions. Monika et al. [

13] investigated multi-stage Tesla valves and achieved an optimal configuration balancing pressure drop and heat dissipation performance by varying the number of channels and valve spacing. Furthermore, Gan et al. [

14] systematically analyzed the impact of geometric parameters—including stage count, inlet width, and channel depth—on labyrinth valve performance. Their findings indicated that increasing the stage count and inlet width while decreasing channel depth facilitates higher pressure drops, thereby optimizing the design of high-resistance labyrinth valves. Collectively, existing studies demonstrate that the synergistic optimization of flow channel shapes and key geometric parameters enables precise regulation of pressure drop and flow field characteristics, providing significant references for valve structural design.

In the field of valve hydrodynamics, flow forces are generally categorized into steady-state and transient forces based on flow regimes. Steady-state flow forces correspond to the force characteristics under fixed operating conditions where flow parameters remain time-invariant. Conversely, transient flow forces primarily stem from fluid inertia variations induced by spool motion and flow rate fluctuations, typically occurring during mode switching or start-stop processes. The magnitude and direction of these forces directly dictate the load characteristics of the driving motor, representing a fundamental research focus in fluid power transmission and control [

15,

16]. Regarding structural optimization, Simic et al. [

17] demonstrated that by optimizing the structural parameters of the valve spool and body, flow forces could be reduced while improving response time by approximately 20% and reducing power consumption by 10%. The 3D CFD simulations and experimental results by Lisowski et al. [

18] indicated that an increase in the internal flow rate of a directional control valve significantly amplifies the flow force, thereby disrupting the original force equilibrium of the spool. Furthermore, Gao et al. [

19] revealed a dual effect of flow forces in high-flow directional valves, characterized as “initially assisting, subsequently resisting” the spool motion: the force acts as a driving force during the startup phase and transitions to a resistive force once the displacement exceeds a certain threshold. Wu et al. [

20] changed the angle between the intake port in the valve sleeve and the valve spool axis to compensate for the valve’s hydrodynamic forces. Consequently, clarifying the evolution laws of steady-state and transient flow forces with respect to structural parameters and flow variations is critical for optimizing spool dynamic characteristics and the matching design of the driving motor.

In recent years, numerical modelling has become an indispensable tool for valve design and flow analysis, as it can resolve the internal hydrodynamics in complex geometries at a much lower cost than purely experimental approaches. Brazhenko et al. [

21] developed a CFD model of a semi-direct acting water solenoid valve using measured diaphragm displacements from a transparent prototype, and showed that the simulated pressure drop and internal flow structure agree well with experimental data, demonstrating that properly validated CFD models can reliably support valve design and optimization. Hadebe et al. [

22] further combined CFD and finite-element analysis to investigate a non-return multi-door reflux valve, using a detailed 3D model and mesh-independence testing to evaluate pressure drop, flow coefficient and backflow-prevention performance under different operating conditions, and showed that numerical simulations can capture the key flow and structural features of multi-port valves. More recently, Yu et al. [

23] carried out a numerical study of a diaphragm valve and systematically compared several turbulence models and inlet boundary conditions, finding that the SST k–ω model provides the best agreement with measured head-loss data over a range of openings. These studies confirm that CFD-based numerical valve models, when combined with appropriate turbulence modelling and validation, can accurately predict valve hydraulic performance. Building on this foundation, the present work adopts the SST k–ω model and a mesh-independent grid to simulate the internal flow and pressure characteristics of the proposed coolant control valve during mode switching.

Despite significant progress in investigating the flow losses, structural optimization, and hydrodynamic characteristics of traditional valves, there remains a lack of systematic research regarding multi-way valves within integrated ITMS. These valves are characterized by highly complex topological structures and multiple flow channels. In particular, the mechanisms of steady-state pressure loss and the laws of transient hydrodynamic response require further exploration. Consequently, existing findings cannot be directly applied to guide the structural design and actuator selection for multi-way valves in the ITMS of NEVs. To address this gap, this study focuses on a multi-way valve utilized in the ITMS of a specific NEV. By employing three-dimensional numerical simulation, the flow loss mechanisms and hydrodynamic characteristics under typical operating modes are systematically investigated.

The main contributions and innovations of this paper are summarized as follows:

A three-dimensional geometric model and a multi-condition hydrodynamic model for the multi-way valve in the Integrated Thermal Management System of electric vehicles were established. High-fidelity flow field simulations were realized under three typical operating modes: cooling, heating, and waste heat recovery. The study deeply investigated the pressure loss distribution characteristics within the complex multi-channels and precisely quantified the proportions and influence mechanisms of local resistance loss versus frictional resistance loss in the total pressure drop.

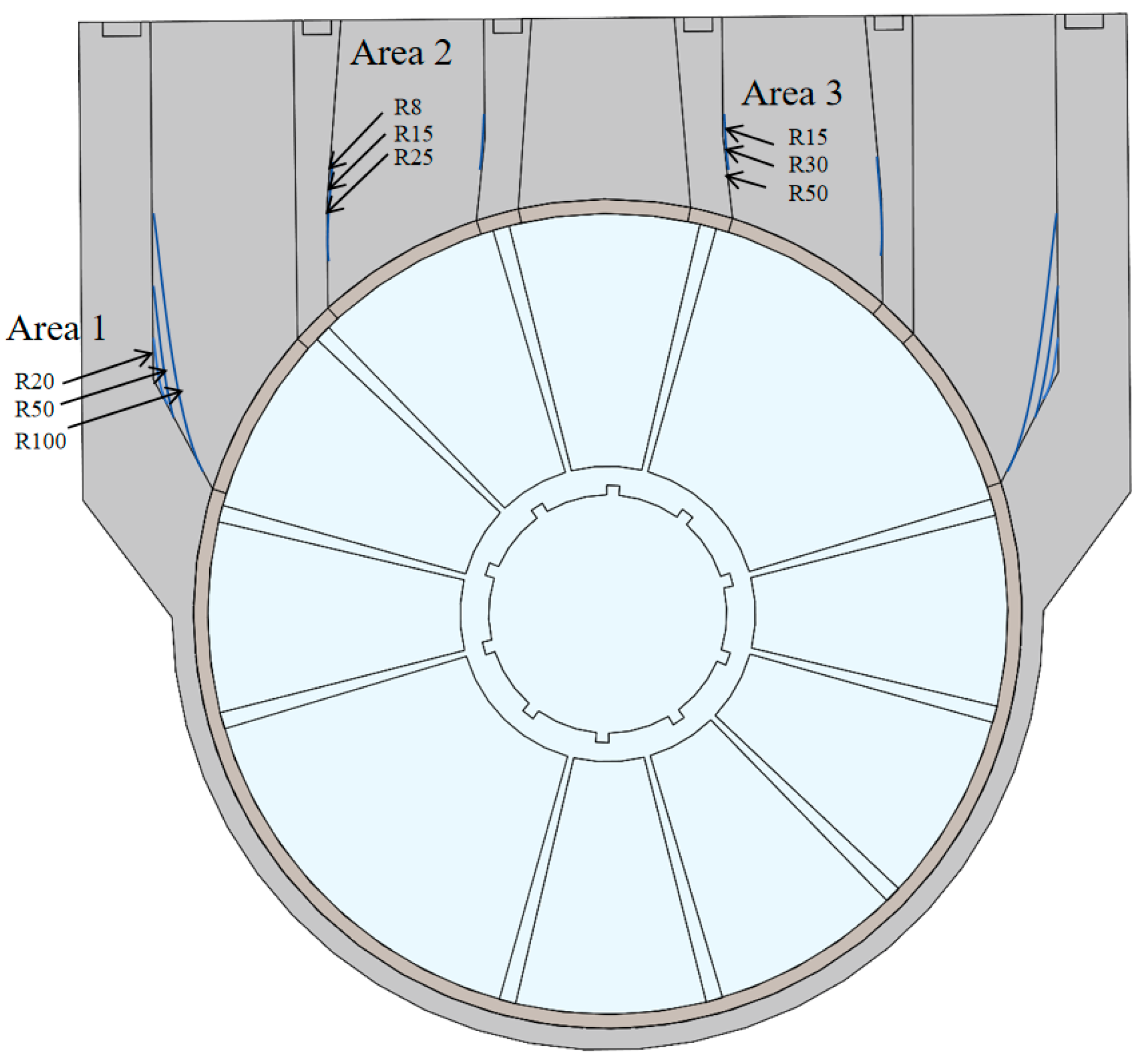

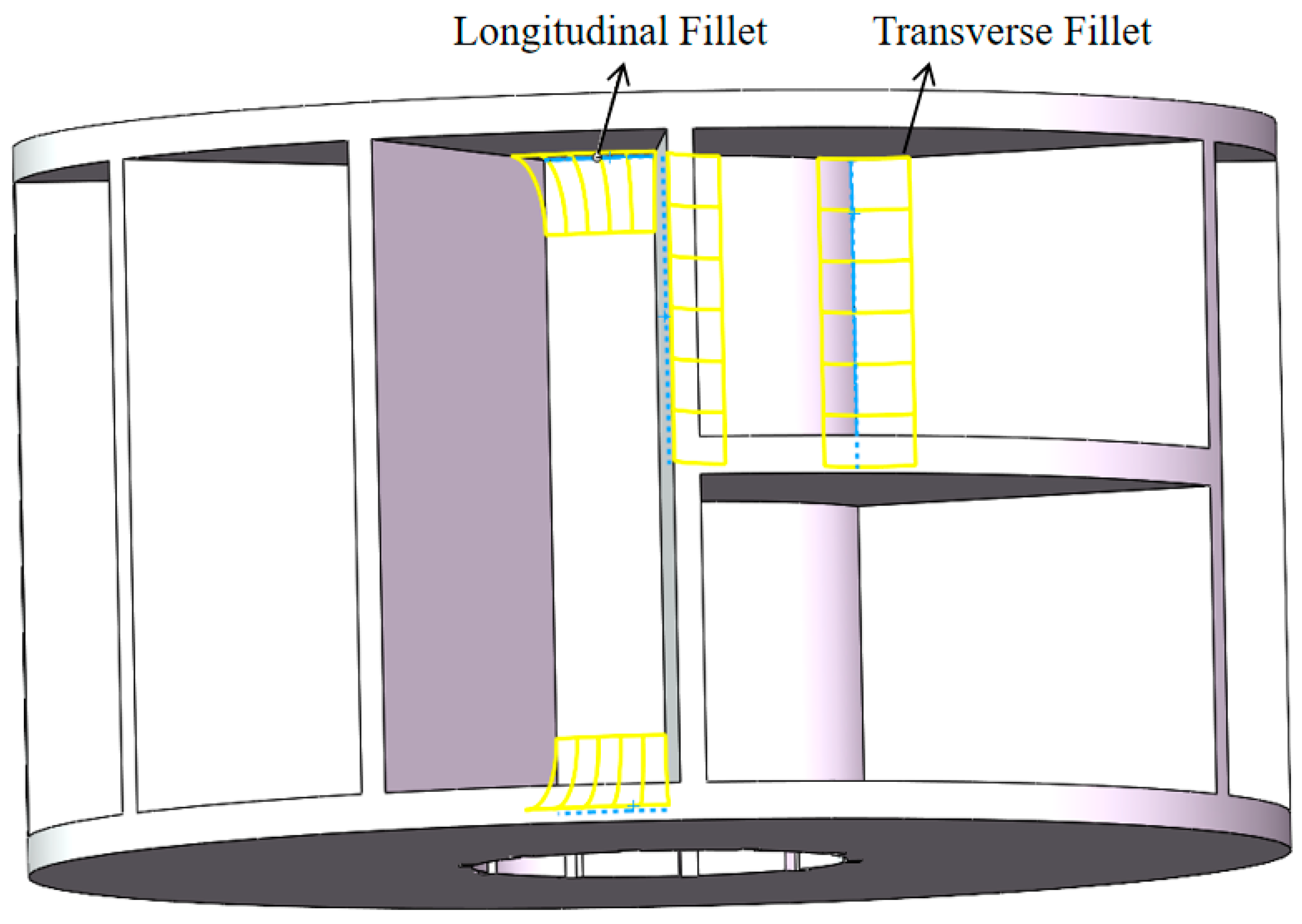

Based on the sensitivity analysis of key structural parameters, geometric optimization criteria for the flow channels were proposed. Through a parametric study on the valve body corner chamfers and the longitudinal/transverse fillets inside the valve spool, the non-monotonic evolution law of flow channel pressure drop with respect to geometric parameters was revealed. Furthermore, the competitive coupling mechanism between flow direction smoothness and effective flow cross-sectional area was elucidated, providing a clear quantitative basis for the low-flow-resistance design of multi-way valves.

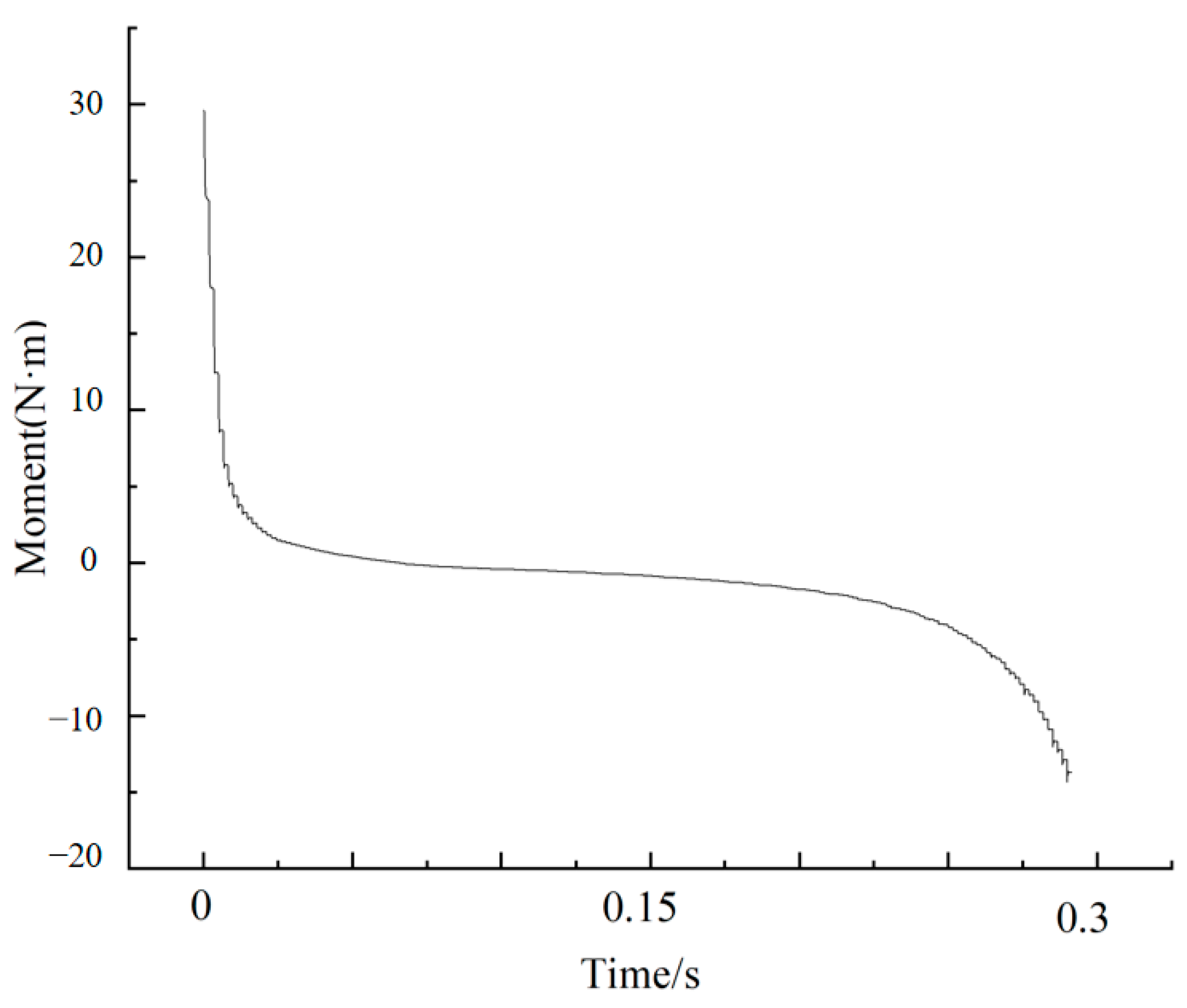

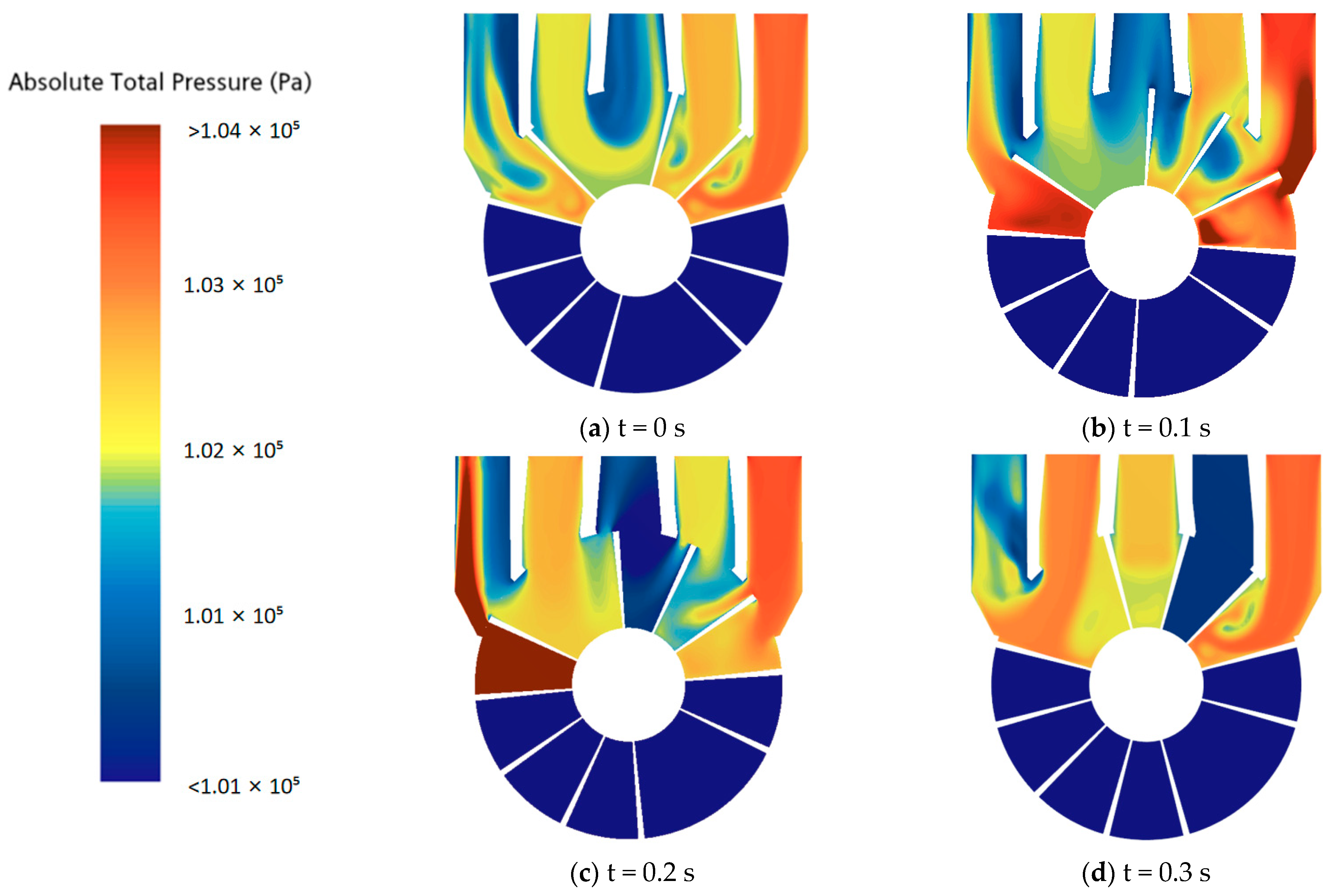

A transient computational model for the dynamic switching process of the valve spool was constructed, addressing the limitations of steady-state analysis. The dynamic process of the valve spool rotating from the heating mode to the waste heat recovery mode was simulated. The time-varying characteristics of the velocity field, pressure field, and hydraulic torque on the valve spool during the switching period were analyzed. The study captured the critical moments when local pressure peaks and hydraulic torque peaks occurred during the transient process, offering significant guidance for actuator selection and the formulation of control strategies.

2. Numerical Model and Computational Method

Thermal management technology is pivotal to the advancement of NEVs. It requires the efficient regulation of temperature fields across multiple heat sources—including batteries, motors, and passenger cabins—under complex operating conditions. Consequently, it directly influences vehicle performance, safety, and user experience. As a critical component of the integrated vehicle thermal management system, the multi-way valve plays an essential role in system performance. In this study, a geometric model is established for a multi-way valve within a specific thermal management system, and its characteristics are investigated using numerical simulation.

2.1. Structure and Operating Modes of the Multi-Way Valve

The multi-way valve investigated in this study is integrated into the integrated thermal management systems of a NEV. The ITMS employs PAG46 coolant to regulate the temperatures of key components, including the battery, motor, compressor, expander, and the indoor and outdoor heat exchangers. By coordinating the operation of these components, the ITMS enables flexible switching among cooling, heating, and waste heat recovery modes to meet thermal management requirements under different driving conditions. In the ITMS considered in this work, thermal energy is transported by a circulating liquid coolant, denoted as PAG46. Specifically, PAG46 refers to an ISO VG 46 polyalkylene glycol (PAG)-based working fluid, as defined by the ISO viscosity classification standard [

24].

The investigated ITMS is a sensible-heat heat-exchange system; therefore, the coolant remains in the liquid state and no phase change is involved in the loop under the studied conditions. Accordingly, the internal flow in the multi-way valve is treated as single-phase liquid flow in the numerical model.

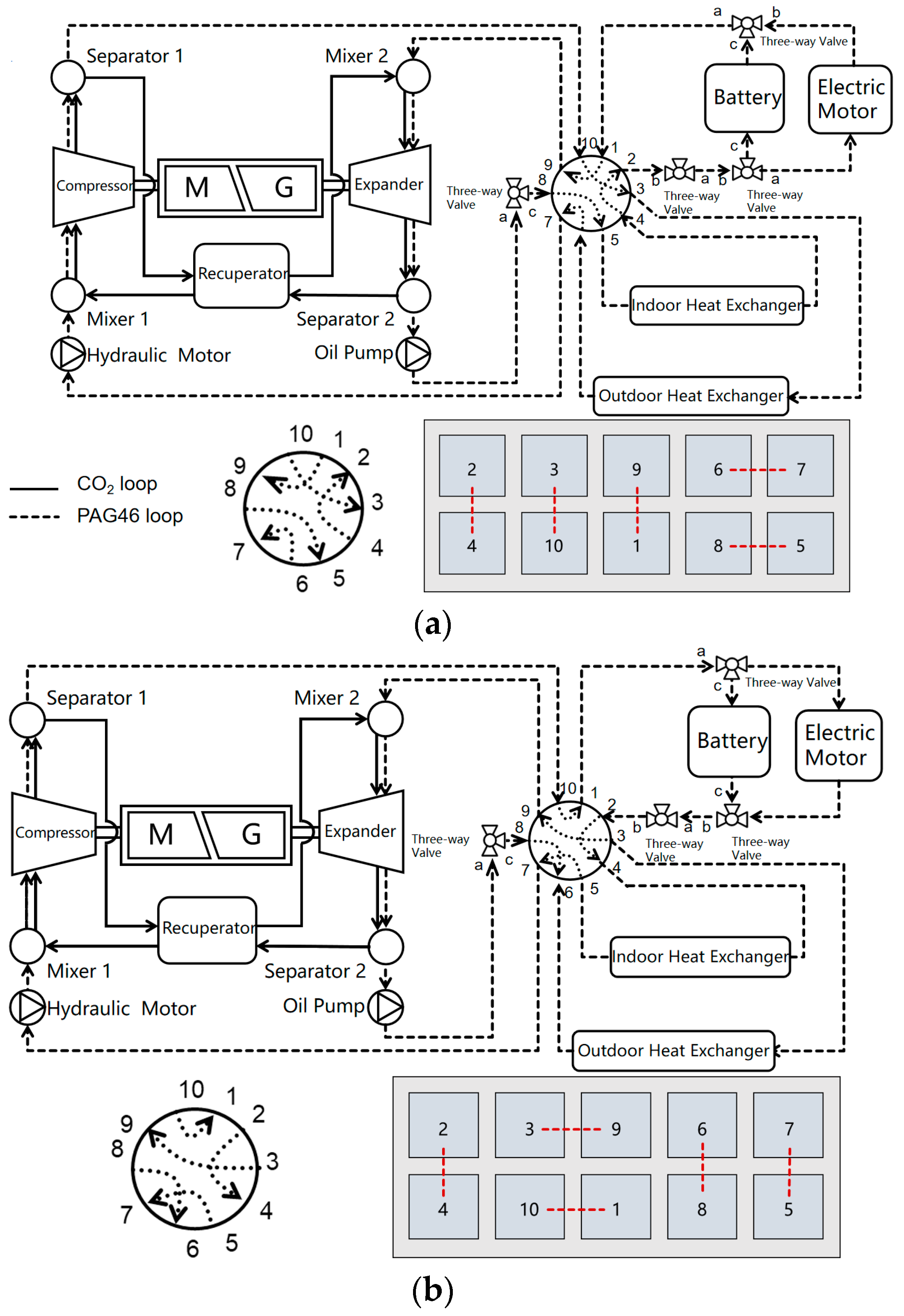

Figure 1. Schematic of the investigated integrated thermal management system (ITMS) and the three operating modes of the multi-way valve: (a) cooling mode, (b) heating mode, and (c) waste-heat recovery mode. Solid lines indicate the CO

2 loop, and dashed lines indicate the PAG46 coolant loop. Arrowheads denote the bulk flow direction in each loop. The multi-way valve is a 10-port rotary valve (ports 1–10); in each mode, the spool connects ports in pairs to form the corresponding flow channels. The dotted flow paths inside the valve symbol illustrate the internal passages opened by the spool position, and the red dashed links in the inset highlight the active port-pair connections for each mode. Mixer 1/2 denote junctions where streams merge, and Separator 1/2 denote phase separators in the CO

2 loop. Oil pump circulates the PAG46 coolant, and hydraulic motor provides the driving power for the coolant circulation unit. M and G denote the motor and generator coupled to the compressor/expander shaft. In this study, PAG46 is treated as a single-phase liquid under the investigated conditions. In this context, the ‘cooling’ and ‘heating’ modes refer to specific ITMS flow-path topologies designed to prioritize cabin climate control while simultaneously managing the thermal requirements of the battery and powertrain. Typically, the cooling mode is activated under high ambient temperatures, whereas the heating mode is engaged at lower temperatures to facilitate both cabin heating and battery preheating. Furthermore, the waste-heat recovery mode is specifically utilized to harvest and repurpose excess thermal energy generated by the battery and traction components.

In the cooling mode

Figure 1a, the high-temperature PAG46 coolant discharged from the compressor flows through the multi-way valve to the outdoor heat exchanger, where it releases heat to the ambient environment before returning to the compressor. Meanwhile, the low-temperature PAG46 coolant, having passed through the expander, provides cooling for the passenger cabin, battery, and motor circuits.

In the heating mode

Figure 1b, the high-temperature PAG46 coolant discharged from the compressor is directed via the multi-way valve to preheat the battery and motor circuits and to supply heat to the passenger cabin. Conversely, the low-temperature PAG46 coolant discharged from the expander absorbs heat from the ambient environment, completing the heat recovery process on the source side.

In the waste heat recovery mode

Figure 1c, the low-temperature PAG46 coolant first absorbs excess heat from the battery and motor circuits and then flows back to the expander. Simultaneously, PAG46 coolant in a separate circuit absorbs heat from the passenger cabin and returns to the compressor. In this way, waste heat from multiple components is effectively recovered and reutilized, thereby improving the overall energy efficiency of the ITMS.

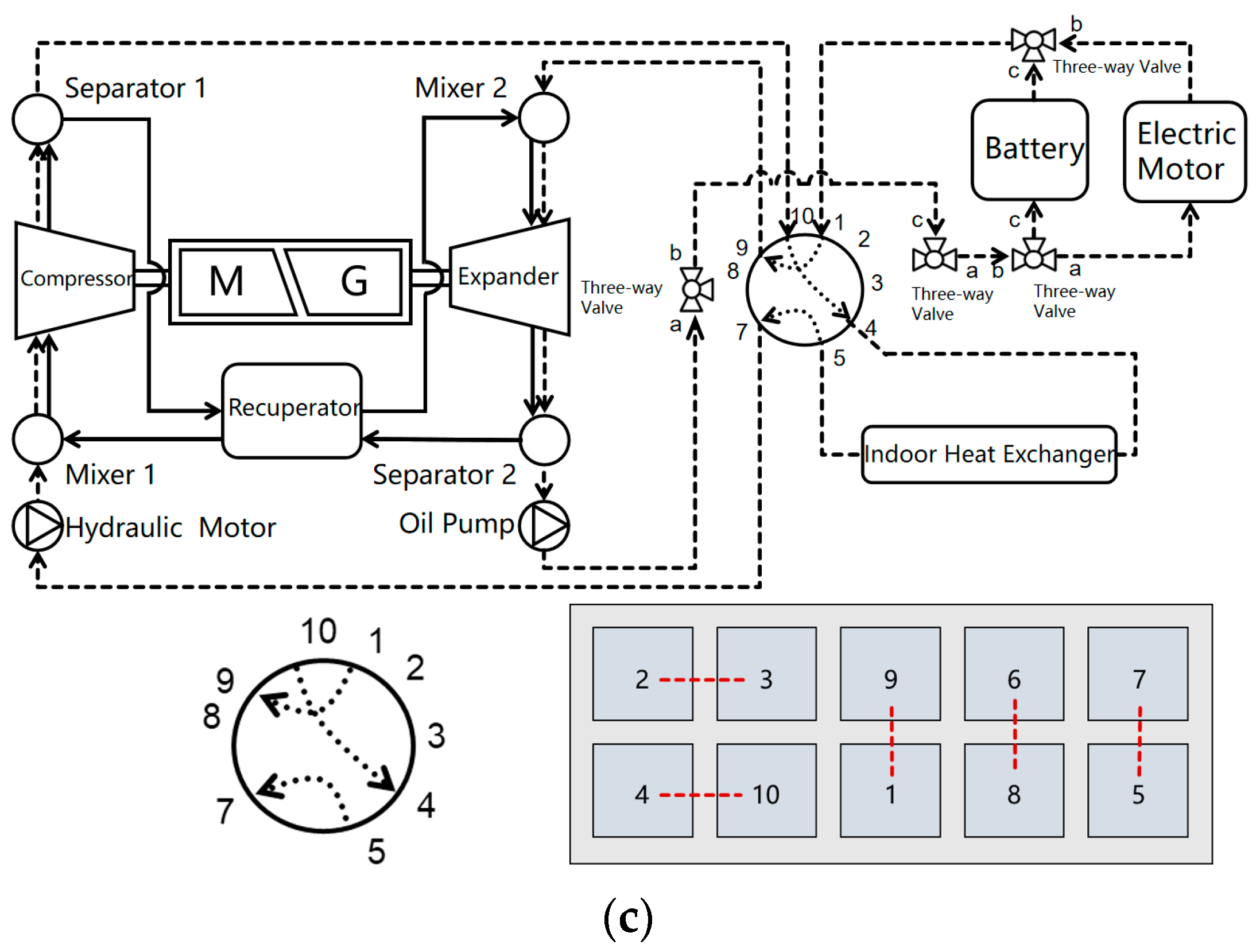

The geometric configuration of the multi-way valve primarily consists of the valve housing, sealing gaskets, and a rotary spool, as illustrated in

Figure 2. The valve features ten ports connected to the inlets and outlets of key ITMS components, including the battery, motor, compressor, expander, and the indoor and outdoor heat exchangers. These ports are interconnected in pairs to form five distinct flow channels. The valve body has overall envelope dimensions of 160 mm in width and 155.5 mm in height. Specifically, the inlet and outlet ports feature a side length of 22 mm each, while the internal rotary spool has a diameter of 108 mm and the sealing gasket thickness is 3 mm. These dimensions represent the characteristic scale of the valve used in the ITMS of the investigated new energy vehicle.

Mode switching is achieved by an electric motor that actuates the rotation of the valve spool, thereby altering the connectivity among the ten ports and reconfiguring the internal flow channels. Depending on the spool position corresponding to cooling, heating, or waste heat recovery mode, different subsets of the five flow channels are activated, and the flow paths of the PAG46 coolant are rearranged accordingly.

In summary, the multi-way valve provides a total of ten distinct port connections and five primary flow channels. Structural variations in these channels govern the direction and distribution of the PAG46 coolant under different operating modes, enabling the ITMS to satisfy thermal management requirements across a wide range of operating conditions.

2.2. Governing Equations and Turbulence Model

In this study, the coolant is treated as an incompressible Newtonian fluid. The flow is governed by the continuity equation and the Reynolds-Averaged Navier–Stokes equations, which describe the mass conservation and momentum transport within the multi-way valve. The continuity equation for incompressible flow is expressed as follows:

Considering the complex flow field within the multi-way valve, characterized by multiple sharp turns, narrow channels, and significant local flow separation, the RANS momentum equations are employed for the numerical solution:

The Shear Stress Transport SST k–ω turbulence model does not rely on wall functions in the near-wall region and is capable of directly resolving the viscous sublayer. Consequently, this model is highly suitable for capturing the flow characteristics in this study, particularly the drastic channel variations and significant local separation.

For the numerical solution, the second-order upwind scheme is adopted to discretize the convection terms, and the SIMPLE algorithm is used for pressure-velocity coupling. To satisfy the near-wall resolution requirements of the SST k–ω model, the average dimensionless wall distance (y+) of the mesh is maintained at approximately 0.83. This ensures the accurate prediction of flow structures and pressure gradients in corners, high-velocity regions, and within the valve spool.

2.3. Mesh Generation and Grid Independence Verification

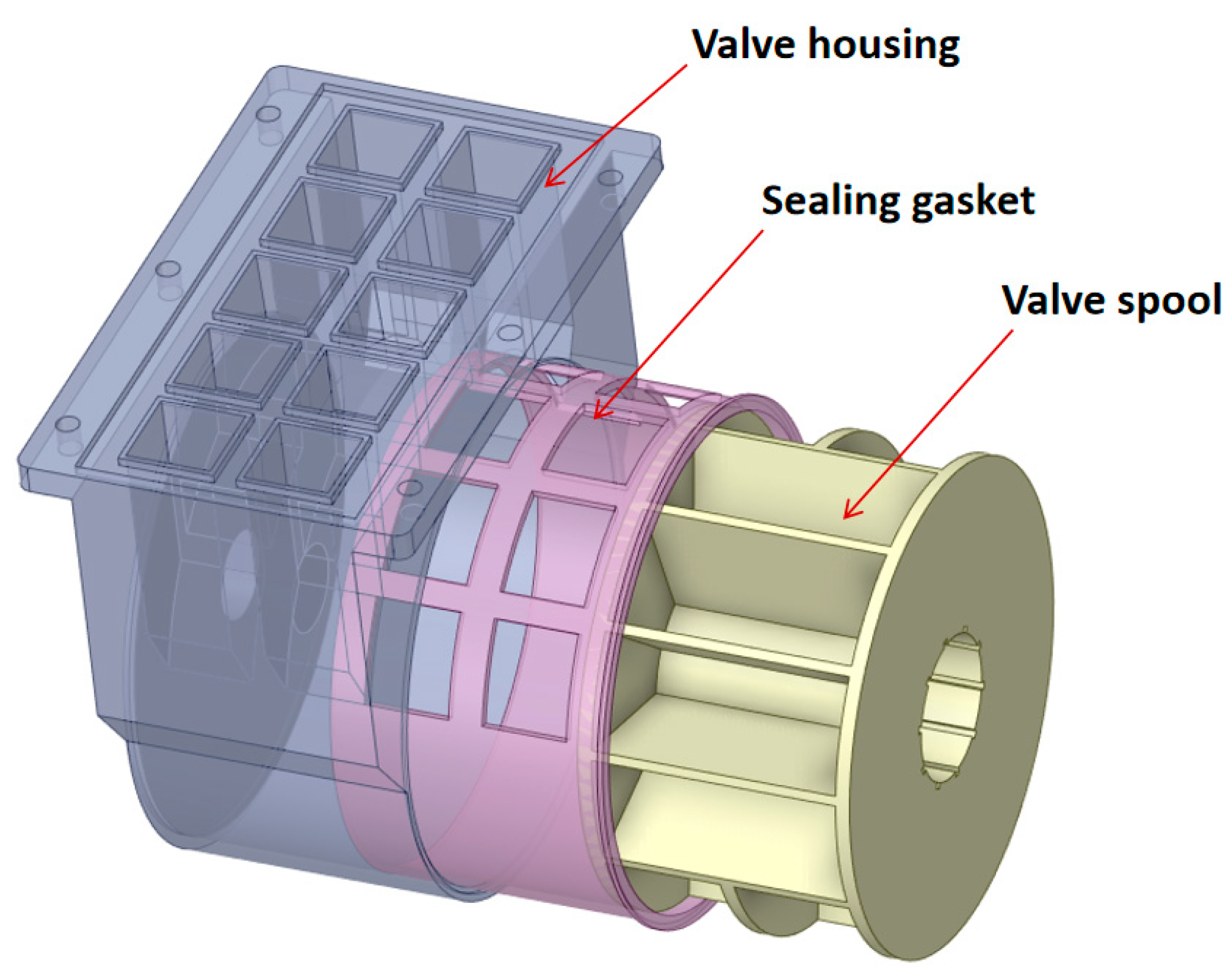

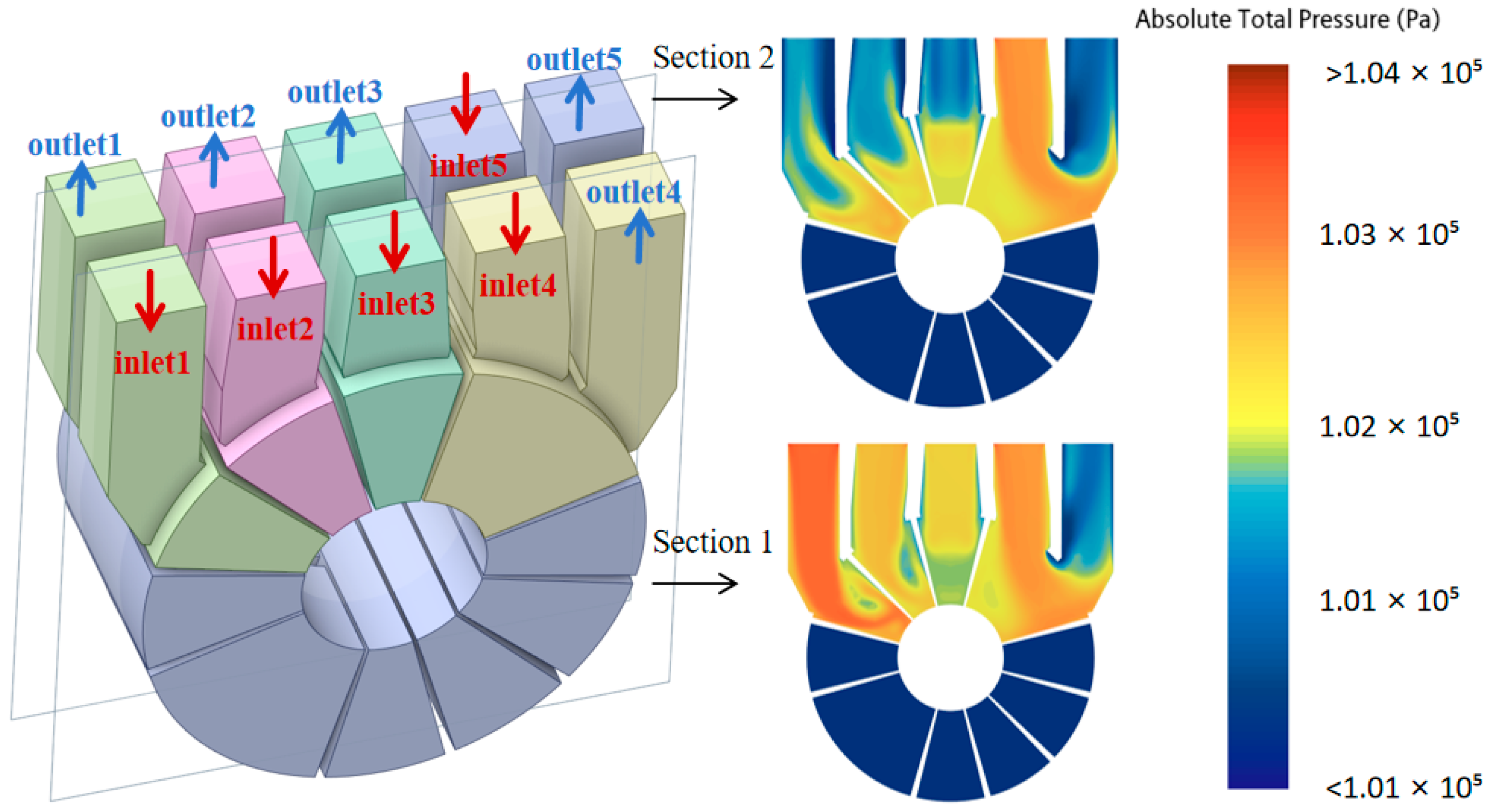

The multi-way valve investigated in this study comprises five flow channels. Following appropriate geometric simplification, the overall simulation model retains only the valve housing, sealing gasket, and valve spool as key components. In both cooling and heating modes, all internal flow channels of the valve are active with coolant flow. For the purpose of illustration, the cooling mode is selected as the representative operating condition: the extracted fluid computational domain is shown in

Figure 3a, and the arrangement of the inlets and outlets is presented in

Figure 3.

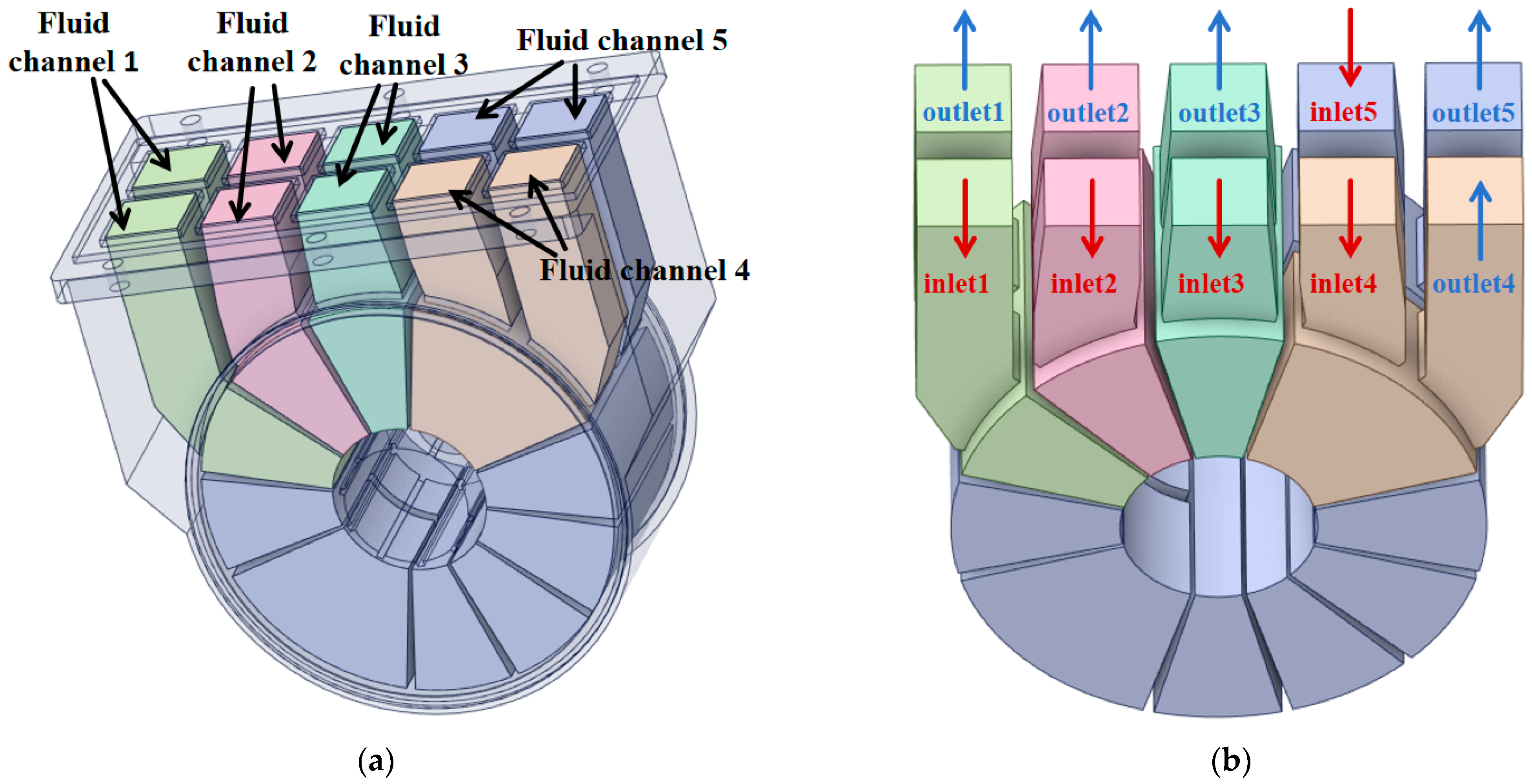

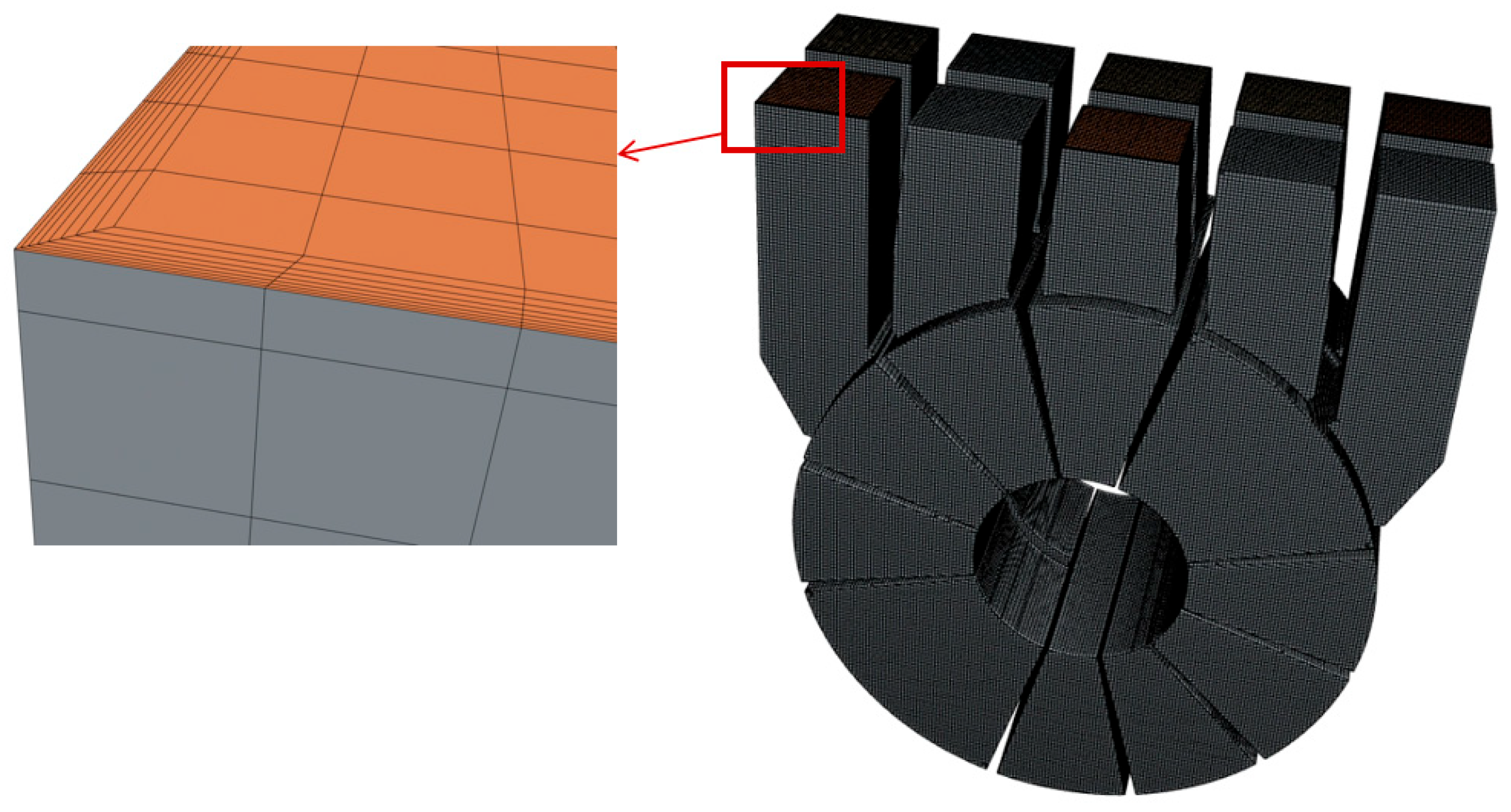

The mesh generation was performed using the automated meshing workflow in STAR-CCM+. The fluid domain was discretized using the Trimmed Cell mesher with a base size of 1 mm. To accurately capture the near-wall flow gradients, boundary layer refinement was implemented using the Prism Layer mesher. Specifically, the boundary layer consisted of 8 prism layers with a stretching ratio of 1.2 and a moderate surface growth rate. The resulting mesh topology and details of the boundary layer refinement are illustrated in

Figure 4.

To ensure computational accuracy and improve efficiency, a mesh-independence study was carried out using the pressure drop as the evaluation criterion. Five meshes with total cell numbers ranging from 8.22 × 10

5 to 3.06 × 10

6 were generated under the same boundary conditions. The pressure drops in Channel 1 and Channel 4, which have different geometries, were calculated and the results are summarized in

Table 1 and

Table 2. When the mesh size reaches approximately 1.9 × 10

6 cells, the variation in pressure drop between the medium and fine meshes becomes negligible: the relative differences are 0.191% for Channel 1 and 0.86% for Channel 4. Therefore, the mesh with about 1.9 × 10

6 elements is considered sufficiently grid-independent and is adopted for all subsequent simulations.

To rigorously quantify the discretization uncertainty, a statistical procedure based on the Grid Convergence Index (GCI) was performed following the standard method recommended by Celik et al. [

25] Although five grid sets were tested for overall sensitivity, a representative triplet—comprising a fine mesh (

cells), a medium mesh

cells), and a coarse mesh (

cells)—was selected for the formal GCI analysis. The apparent order of convergence (

) for Channel 1 and Channel 4 was calculated to be 6.37 and 3.59, respectively. The resulting

values are 0.14% and 1.40%, both of which are significantly below the 5% threshold. This confirms that the numerical solutions are well within the asymptotic range of convergence and the discretization error is negligible.

2.4. Boundary Conditions

Since the investigated ITMS is a sensible-heat heat-exchange system and no phase change in PAG46 occurs under the studied operating conditions, the internal flow in the multi-way valve is modelled as an incompressible single-phase liquid under isothermal conditions. The temperature is fixed at 313 K, and the thermo-physical properties of PAG46 are evaluated at this reference temperature and treated as constants. Therefore, heat transfer and thermal coupling are not activated in the present simulations, and the analysis focuses exclusively on the hydrodynamic characteristics of the flow.

In all simulations, the PAG46 working fluid is modelled as an incompressible Newtonian single-phase liquid, consistent with the fact that the investigated ITMS is based on sensible heat transfer and the coolant does not undergo phase change under the studied conditions. The thermo-physical properties used in the CFD simulations are summarized in

Table 3 (evaluated at T = 313 K and treated as constants).

The inlet boundary condition is prescribed as a mass-flow inlet with a total mass flow rate of 0.84 kg/s. The outlet is set as a pressure outlet with a specified static pressure. All solid walls are treated as no-slip boundaries. For turbulence specification, the inlet turbulence quantities are initialized using standard turbulence intensity/length-scale settings available in STAR-CCM+. The temperature is uniformly set to 313 K for all operating conditions.