Abstract

To address the reclosing failures in the distribution networks (DNs) with high penetration of distributed energy resources (DERs), this paper proposes a communication-free cooperative fault recovery control method based on staged active power injection of an energy storage (ES) system. First, during the initial phase of a fault, a back-electromotive force (b-EMF) suppression arc extinction control strategy was designed for the ES converter, promoting fault arc extinction. Subsequently, the ES switches to grid-forming (GFM) control, providing active power injection to the network following the circuit breaker (CB) tripping. A time-limited variable power control of ES converter is also designed to establish voltage characteristics for fault state detection. And a fault state criterion based on voltage relative entropy is designed, helping reliable reclosing. Simulation results demonstrate that the proposed method achieves coordination solely through local measurements without the need for real-time communication between ES and CB, and can shorten the recovery time of transient faults to hundreds of milliseconds.

1. Introduction

Automatic reclosing is the primary method for addressing transient faults common in overhead distribution lines and enhancing power supply reliability [1]. The integration of DERs transforms traditional single-source radial DNs into multi-source networks, making them highly susceptible to sustained arcing faults and failed reclosing [2,3]. Most existing approaches to improving reclosing for active DNs extend the reclosing dead time to 3~6 s through coordinated timing between reclosing and DERs islanding protection, ensuring all DERs reliably disconnect during reclosing [4,5]. However, as the proportion of DERs continues to rise, this solution will face new challenges.

On the one hand, large-capacity, scaled DERs generally possess low voltage ride through (LVRT) capability. According to relevant standards [6], the maximum action time limit for anti-islanding protection has exceeded 300 s. This will result in prolonged reclosing wait times, severely impacting power supply reliability. On the other hand, if large-scale DERs were to disconnect from the grid entirely, it would cause drastic changes in power flow within the distribution network before and after the fault, as well as false tripping of backup protection, leading to secondary system impacts [7]. Reliably identifying the clearance of transient faults and promptly reclosing before widespread DERs disconnection could effectively resolve this issue.

In addition to the aforementioned methods for extending dead-time settings, existing research on improved reclosing for DNs incorporating DERs also includes the voltage detection method [8,9] and adaptive reclosing method [10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18]. Among these, the voltage detection method identifies the off-grid status of DERs by detecting voltage levels. However, it cannot distinguish this condition from the zero-voltage state caused by three-phase metallic faults, and thus still fails to resolve the issue of reclosing onto faults.

The core of adaptive reclosing methods lies in detecting fault conditions to adaptively adjust the reclosing dead time, ensuring reliable reclosing on non-faulty lines. Existing research can be categorized into two approaches: passive detection methods [10,11,12,13] and active signal injection method [14,15,16,17,18]. The passive detection method identifies the fault condition by analyzing the transient free oscillation signals after tripping, such as utilizing the attenuation characteristics of line capacitive discharge or network parameter identification. In [10], transient high voltage is applied to de-energized feeders via thyristor control, and the fault type is identified from the feeder’s frequency response to enable adaptive reclosing. However, due to the small line-to-ground capacitance of overhead distribution feeders, this method has difficulty accurately capturing high-frequency attenuation signals.

In contrast, the active signal injection method relies on injecting characteristic signals through additional power electronic devices and determining the fault condition by analyzing the voltage spectrum at the CB terminal. In [14], a STATCOM controls its converter sub-modules to briefly discharge DC capacitors into the faulty line, injecting a small current whose correlation coefficient is used to distinguish transient from permanent faults. Nevertheless, this method requires communication coordination between the high and low voltage sides of distribution transformers, as well as a relatively complex control system.

In summary, relying solely on reclosing is insufficient for effective fault restoration. Both passive detection and active signal injection methods require coordination between reclosers and controllable devices. However, the long electrical distances and the difficulty of high-speed communication in distribution networks make developing adaptive reclosing strategies based on fault characteristics—without additional equipment—a critical challenge.

Energy storage (ES) is one of the viable solutions to the aforementioned issues. with global installed capacity reaching nearly 28 GW by 2022 (data from IEA). By effectively utilizing the bidirectional power regulation capability of ES converters, effective technical support can be provided for arc extinction and fault state identification during fault recovery, thereby improving restoration efficiency and operational safety.

This study analyzes the characteristics of metallic short circuits and fault clearance in DNs incorporating ES following a trip. It constructs a fault state detection criterion based on voltage relative entropy derived from post-fault voltage rise, and designs a control method for arc extinction via b-EMF suppression in ES converters based on arc extinction conditions. Furthermore, considering protection action scenarios, an adaptive setting scheme for reclosing delay is designed. A rapid fault recovery control method for DNs is proposed, based on the three-stage sequential coordination of reclosing and ES. Simulation results demonstrate that the proposed method can effectively identify fault clearance and adaptively shorten reclosing delay based on fault detection outcomes and protection actions. This significantly minimizes the extensive disconnection of DERs and ES following transient faults, thereby facilitating rapid system restoration. Compared to the existing research, the main contributions of this study are as follows:

- A rapid fault recovery control method for DNs is proposed, based on the three-stage sequential coordination between reclosing and ES.

- Different from existing active detection schemes that rely on dedicated FACTS devices or communication links, the proposed method leverages inherent GFM-ES capabilities to construct fault-identifiable voltage features, enabling reclosing decisions based purely on local measurements.

- A fault detection method based on voltage relative entropy is proposed, and an adaptive reclosing delay setting scheme is designed considering protective action scenarios.

The remainder of this study is organized as follows. In Section 2, a three-stage control strategy for ES-reclosing cooperation was designed, comprising arc extinction control, GFM control, and variable power control. In Section 3. This paper analyzes the post-tripping system characteristics and the fault detection method based on voltage relative entropy; Section 4 determines the fault recovery control timing sequence for ES-reclosing communication-free cooperation. Section 5 presents simulation results obtained in PSCAD, verifying validity and feasibility of the proposed method. Section 6 provides the conclusions.

2. Three-Stage Sequential Control Strategy for ES-Reclosing Coordination

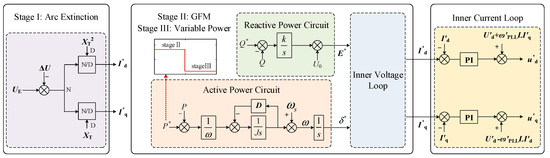

After a DNs fault triggers a trip, reclosing may encounter three scenarios: metallic short circuits, sustained arcing, or fault clearance. To address system restoration control requirements under various fault conditions, this study proposes a three-stage sequential control strategy for the ES. First, to assist in arc extinction, the ES enters arc extinction control (Stage I) immediately after a fault occurs, aiming to suppress the point of common coupling (PCC) voltage to zero. After several power-frequency cycles, the ES transitions to grid-forming (GFM) control (Stage II) to provide voltage support for the downstream system during reclosing and help construct fault detection characteristics. If no fault clearance is detected within the specified time, the ES enters Stage III to implement variable power control and actively identify the fault status. The three-stage sequential control strategy of the ES is shown in Figure 1 (* means reference value).

Figure 1.

Three-Stage Sequential Control Strategy Structure Diagram for ES.

2.1. Stage I: Arc Extinction Control of ES Converters

For persistent arc faults, reducing the voltage amplitude can assist the extinction of AC fault arcs [19,20,21]. This study leverages the bidirectional power controllability of ES grid-connected converters. Upon fault detection, the ES converter switches to arc extinction control by monitoring the voltage drop at the PCC, targeting zero output voltage.

At this stage, PCC voltage is given by Equation (1)

where represents the PCC voltage (Since downstream systems may have DERs remaining connected after a CB trip, the voltage control target at PCC is reduced to −10% UN.), and represent the ES output voltage and current, respectively. RT and XT represent the equivalent impedances of the ES step-up transformer.

Further derived from Equation (1), the required output current of the ES for arc extinction control is:

To facilitate implementation in the ES inverter, the current command is further expressed in the synchronous dq reference frame, where the d-axis is aligned with . Under this condition, the inverter current commands are given by:

In practical ES step-up transformers, the winding resistance is much smaller than the leakage reactance, i.e., RT << XT. Therefore, Equation (3) can be simplified to

The arc extinction control block diagram for the ES converters is shown in Stage I of Figure 1. After a fault occurs, Id/Iq assumes the command value for arc extinction control. After 60 ms (the fault arc typically extinguishes after three power-frequency cycles under zero-voltage conditions [22,23,24]), the system switches to GFM control mode.

2.2. Stage II: GFM Support and Fault State Identification of ES

GFM-DERs grid-connected converters exhibits “voltage source” characteristics externally, possessing the capability to actively support grid voltage and frequency. Its general-purpose control loop is shown in Stage II of Figure 1.

GFM control of ES can provide voltage support after fault clearance, enabling it to rise back to its rated value. In contrast, during permanent faults, the voltage level remains at a persistently low level, with waveform characteristics generally exhibiting similar patterns.

Following a fault trip, the recloser continuously acquires and calculates the positive-sequence voltage downstream of the CB in real time. This study establishes a voltage relative entropy criterion based on the waveform characteristics of voltage rise after fault clearance (see Section 2.2 for details), enabling the identification of transient versus permanent faults. If the fault is transient and determined to have cleared automatically, a reclosing operation will be performed after a preset delay. If the fault is not detected as cleared within the monitoring period, the ES will initiate variable power control.

2.3. Stage III: Active Fault Identification Based on Variable Power Control of ES

When voltage rise characteristics remain undetected for an extended period, the ES employs a variable power control strategy after a predetermined delay. This strategy actively reduces active power output by modifying the reference value p* within the active power loop depicted in Figure 1. At this point, if the fault has been cleared, the downstream voltage will decrease as power output reduces. Conversely, if the fault persists, the downstream voltage will remain unchanged regardless of variations in ES output power, and the waveform characteristics will generally remain similar.

Similarly, the reclosing system continuously acquires and calculates the positive-sequence voltage downstream of the CB in real time, determining whether the fault has been cleared based on the principle of relative entropy. If the fault is determined to be cleared, the system executes the reclosing operation after a preset delay; if the fault is determined to remain, reclosing is immediately blocked.

3. System Characteristics Analysis and Fault State Identification Before Reclosing

3.1. Analysis of Characteristics of Metallic Short-Circuit Faults

For persistent metallic short-circuit faults accompanied by CB tripping, the fault current contribution from the main grid is rapidly disconnected once CB operates. As a result, the total fault current drops instantaneously. After the tripping of the CB, the remaining fault current is mainly supplied by ES. Due to the inherent current-limiting capability of ES converters, the fault current magnitude is significantly reduced from 20–30 times the rated current (dominated by the main grid) to approximately 1.1–3 times the rated current.

Correspondingly, the downstream voltage of the distribution system decreases after the CB tripping, since the contribution of the large grid-side fault current is eliminated. The downstream fault voltage can be expressed as:

where U represents the downstream distribution system voltage, IS denotes the fault current of ES, IGrid represents the network-side fault current, ZΣ denotes the equivalent impedance of the distribution line, and Rf signifies the fault resistance.

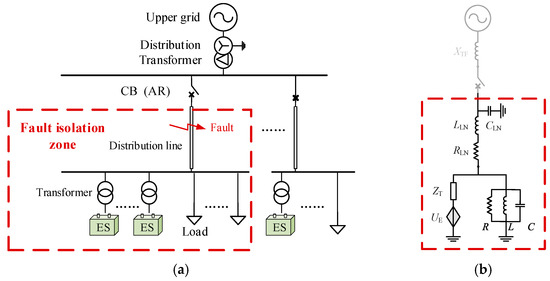

The fault state of a persistent metallic short circuit can be identified based on the characteristic of non-elevation in voltage amplitude before and after tripping. Figure 2a depicts the system prototype network, which includes multiple feeder lines downstream. When a fault occurs on one of these feeder lines, the circuit breaker trips, isolating the faulty feeder from the grid. For subsequent analysis, the downstream ES units and loads are treated as parallel equivalents.

Figure 2.

Diagram of the prototype distribution networks with ES connected. (a) Prototype system. (b) Equivalent circuit.

For analytical convenience, multiple parallel-connected ES units are also equivalently simplified into a single ES unit, and the distribution transformers, lines, and load circuits from the ES to the fault point in the downstream system are collectively simplified as a parallel R-L-C branch (see Appendix A.1 for derivation details). The system after tripping is shown in Figure 2b. Where XTF denotes the equivalent impedance of the primary distribution transformer; RLN, LLN, and CLN represent the equivalent resistance, reactance, and capacitance of the line, respectively; R, L, and C denote the equivalent resistance, reactance, and capacitance of the load, respectively.

The current limit for GFM-DERs is typically set at 3 times the standard value. When the current reaches this limit, the system voltage will drop below the rated value. Based on the current limit for GFM-DERs, Id can be calculated as:

IN represents the rated current value of the ES; Kre denotes the current limiting coefficient, typically ranging from 2.5 to 3, with 3 adopted in this study. Based on Kirchhoff’s voltage law for DNs incorporating ES, the following can be derived:

The frequency of DNs incorporating GFM-DERs can be maintained at its rated value. Therefore, after a CB trips, XLC in Equation (7) remains constant. Substituting Iq from Equation (7) into Equation (6) allows Id to be further expressed as:

where kd is the ratio of Id to IN. Substituting Equation (8) into Equation (7) yields the voltage of the DNs after fault clearance:

Convert IN and R in (9) into the form expressed by power P and voltage U:

where P represents the active power output from ES, PL denotes the active power of the load, and Kp is the ratio between the two.

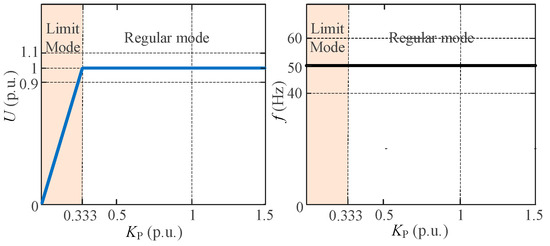

In summary, after fault clearance, the segmented relationship between the Kp and U, f is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

The segmented relationship between the Kp and U, f after fault clearance.

3.2. Fault State Identification Based on Voltage Relative Entropy

3.2.1. Relative Entropy Principle and Voltage Characteristic Quantization

Relative entropy characterizes the similarity between two different signal waveforms. The larger the value, the greater the difference between the two waveforms; conversely, the smaller the value, the higher the similarity between the waveforms.

This study establishes voltage relative entropy as a criterion, collecting and calculating in real time the positive-sequence voltage downstream of the CB after tripping, then integrating it. The expression for the positive-sequence voltage integral Hu(t) is:

where ||()|| is the positive-sequence voltage amplitude.

Select the steady-state portion of the fault voltage waveform as the reference window T, with its duration denoted as ΔT. Construct a sliding detection window T’ with the same duration ΔT. Acquire and compute the positive-sequence voltage data downstream of the CB in real time at a sampling frequency of 1.2 kHz. The positive-sequence voltage integral values for the windows is:

3.2.2. Formula for Calculating Voltage Relative Entropy

Assuming the voltage integral value obtained from the reference window is Hu1 and the voltage integral value obtained from the sliding detection window is Hu2. According to the relevant definition of relative entropy, the voltage relative entropy Su_1−2 between signal ‖‖ and signal ‖‖ is expressed as shown in Equation (13).

where and represent the values of the jth sampling point in the reference window and sliding detection window, respectively, and N denotes the total number of sampling points, all of which have undergone normalization. (see Appendix A.2 for derivation details)

The voltage relative entropy Su_2−1 between signal ‖‖ and signal ‖‖ is:

The composite relative entropy index Su for the voltage between two windows is defined as:

After calculating the relative entropy of the voltages in the two waveforms using Equation (15), it follows from its definition that the magnitude of the entropy value reflects the degree of difference in waveform amplitudes. Based on this, fault conditions can be identified.

Detection of voltage relative entropy uses positive-sequence voltage amplitude as the sample. When fault resistance increases, voltage rises accordingly. The positive-sequence voltage expression is as follows:

where is the positive-sequence voltage at the fault point, is the open-circuit voltage at the fault point prior to the fault (with Phase A as reference), is the positive-sequence current, and Z1∑ is the system positive-sequence impedance viewed from the fault point.

For three-phase short-circuit faults, two-phase-to-phase faults, and two-phase-to-ground faults, the positive-sequence voltages are, respectively:

where Z2∑ and Z0∑ represent the negative-sequence impedance and zero-sequence impedance of the system, respectively, as viewed from the fault point.

For a two-phase-to-ground short circuit, the fault resistance Rf appears in the zero-sequence circuit and is equivalently amplified to 3Rf. Compared to three-phase faults and two-phase-to-phase faults, when Rf increases, the positive-sequence voltage of a two-phase-to-ground short-circuit fault is most significantly affected by the fault resistance. As the fault resistance increases, the voltage rise is most pronounced. This characteristic causes ABGs to maintain elevated voltage levels when unresolved, resulting in relatively small voltage variation before and after fault clearance. Consequently, it represents the most challenging critical operating condition to identify.

The detection threshold is set to establish a reliable and conservative criterion, ensuring effective identification of fault conditions across various fault scenarios. Based on the above analysis, the relative entropy of a two-phase ground fault under high-resistance conditions is selected as the threshold setting reference K. Additionally, to avoid unreliable judgments caused by transmission errors in voltage transformers, the error value is incorporated. Thus, the transient fault criterion is defined as:

where ε is the correction error coefficient for the system’s amplitude measurement accuracy. In DNs, the accuracy of voltage transformers is typically ±3%. This study sets the amplitude to 0.95 [25].

For DERs that remain connected to the grid during faults, although their voltage support capability is weaker than that of GFM-ES, the power they deliver to loads can still assist in raising voltage levels. This, in turn, reduces the risk of misjudging the fault state.

4. ES-Reclosing Cooperative Fault Recovery Control Timing Setting Scheme

Following a short-circuit fault in the DNs, the relay protection device initiates CB tripping after a preset short delay threshold. Concurrently, the ES activates b-EMF arc extinction control to reduce PCC voltage. After the arc extinction control period, the ES switches control strategies to provide voltage support for downstream loads.

In DNs, transient faults caused by lightning strikes, bird contacts, and other factors typically clear spontaneously within 0~1 s. Considering the protection operation conditions and the requirements of fast auto-reclosing, this study assumes a maximum transient fault duration tf_max of 1.2 s, which is used as the boundary between Control Stage II and Stage III. Based on different entropy detection conditions and protection action types, the adaptive setting of reclosing delay can be further subdivided into the following two specific scenarios for in-depth research and analysis.

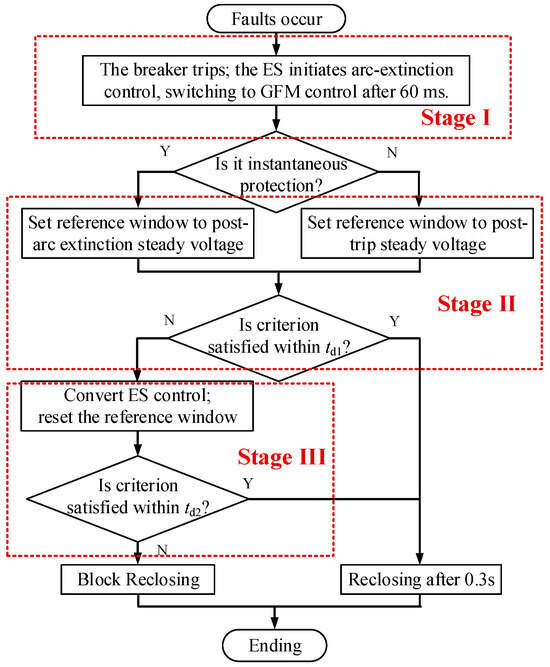

Case-1: When a fault clearance is detected in a timely manner during Stage II, this situation can be further divided into two scenarios:

(1) When the protection action type employs instantaneous protection (such as interlocked differential protection, instantaneous current protection, and distance stage I protection, etc., ttrip = 0.03 s [26]), the reference window is set after the arc extinction control time concludes and undergoes a voltage fluctuation transient period tT (set to 100 ms in this study). This ensures the voltage signal within the window has recovered from transient disturbances and reached a stable state. The sliding detection window then commences with the reference window as its starting point.

(2) When the protection action type is a time-limited instantaneous protection (e.g., time-limited current instantaneous protection, distance stage II protection, etc., with ttrip = 0.5 s [26]) or a time-delayed protection (e.g., time-delayed overcurrent protection, distance stage III protection, etc., with ttrip = 1 s [26]), the reference window is set after tripping and after the voltage fluctuation transient period tT. The sliding detection window then begins detection starting from the reference window, with the detection time constrained as follows:

- Not exceeding the difference between the fault duration and the protection trip time, taking into account the sliding detection window time window duration ΔT and the voltage transient time tT;

- Not exceeding the difference between tf_max and the protection trip time.

In summary, the detection time td1 is given by Equation (21):

Within detection time td1, if criterion (20) is satisfied, the fault is cleared and reclosing occurs after a 300 ms delay, which is determined by accounting for the inherent switching time of the CB and the environmental deionization time; if criterion (20) is not satisfied, proceed as follows.

Case-2: When fault clearance cannot be detected in a timely manner during Stage II:

If the voltage rise following fault clearance occurs within the reference window, or if the fault is cleared before the reference window, subsequent voltage relative entropy measurements will yield lower values. This creates a detection dead zone of a certain duration. To address this issue, this study proposes a detection method that actively reduces the output power of the ES and resets the reference window

If the fault occurs and criterion (20) remains unsatisfied after Stage II, according to Equation (9), the active power P regulated by the ES is:

Reduce P to lower the voltage downstream of the CB to 0.2 p.u. Simultaneously, reset the reference window to the latter segment of Stage II (set to the 1.15~1.2 s interval in this study). The sliding detection window begins detection starting from the reference window, recalculating the voltage relative entropy within both the reference window and the sliding detection window.

Considering window duration ΔT and the voltage transient duration tT, the detection time td2 is given by Equation (23):

Within detection time td2, if criterion (20) is satisfied, the fault is cleared and reclosing occurs after a 300 ms delay; if criterion (20) is not satisfied, reclosing is blocked. After the detection time elapses, the ES resumes GFM control. The detection flowchart is depicted in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Flowchart of the proposed fault recovery control method.

5. Simulation Verification

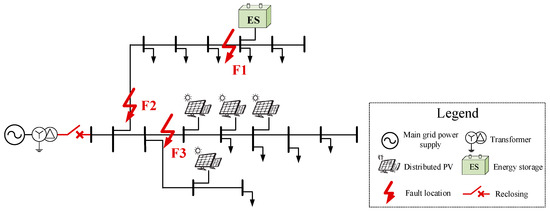

To validate the conclusions of fault characteristic analysis and the effectiveness of the proposed ES-reclosing non-communication cooperative fault recovery control method based on local detection, a simulation system was constructed on the PSCAD/EMTDC platform. A 100 kW ES was connected to a 10 kV distribution feeder (see Appendix C for derivation details). The detailed system structure is shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Schematic Diagram of ES Integration into DNs Topology.

A three-stage current protection system is installed at the substation’s outgoing CB. The voltage measurement point for adaptive reclosing is located downstream of the CB, where it monitors and continuously calculates the downstream positive-sequence voltage. The relative entropy value of the voltage for a 500 Ω ABG fault was selected as the basis for the detection threshold. The window duration ΔT was set to 50 ms (sufficient to capture 2–3 cycles of the power frequency voltage), and K was ultimately determined to be 0.095 based on Equation (20).

All faults are assumed to occur on the feeder downstream of the CB. The main transformer in the DNs has a capacity of 5 MVA, operates at a voltage level of 110/10 kV, employs a YNd connection, and has a short-circuit impedance of 10.5%.

5.1. Single Transient Fault Case Verification

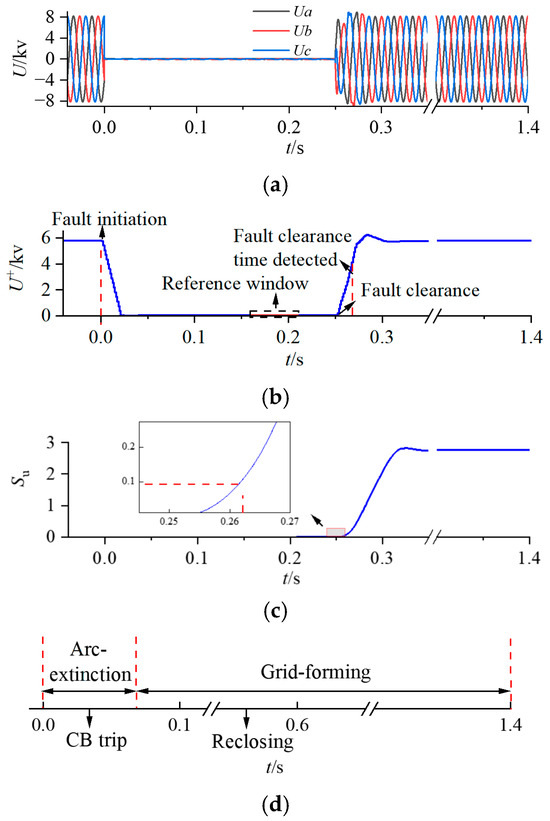

Simulations of transient and permanent three-phase faults (ABC) at point F1, with a fault resistance of 10 Ω, were conducted to evaluate the performance of the proposed method. The fault occurs at time 0 s, with an transient fault duration of 250 ms. The fault detection diagram is shown in Figure 6, where Figure 6a,b represent the faulted three-phase voltage and positive-sequence voltage, respectively. Figure 6c depicts the entropy value curve over time. Figure 6d illustrate the ES and Reclosing control strategies

Figure 6.

Fault Detection Diagram for Single Transient Fault Conditions. (a) Three-phase voltage. (b) Positive sequence voltage. (c) Relative entropy. (d) ES and Reclosing control.

Following a fault occurrence, the CB trips after 30 ms, simultaneously initiating arc extinction control at the ES. After 60 ms, the control strategy switches to GFM control. At 0.263 s, fault clearance is detected, and reclosing occurs after a 300 ms delay.

5.2. Verification Under Different Fault Locations

Based on the preceding discussion, it can be concluded that the proposed cooperative fault recovery control scheme, by effectively integrating protection action information, can significantly reduce fault detection time. Given that the operating characteristics of protective devices vary when faults occur at different locations along the feeder, it is necessary to systematically verify the performance of cooperative fault recovery control scheme under various protective action scenarios.

This section constructs three typical fault location scenarios: F1 (at the beginning of the line), F2 (at the end of the line), and F3 (at the 10% point of the downstream line). These locations correspond to the operational conditions of instantaneous protection, time-limited instantaneous protection, and time-delayed protection, respectively. Taking a three-phase metallic short-circuit fault through a 10 Ω transition resistor as a typical fault type, both transient and permanent faults with varying durations are considered. The performance of the proposed cooperative fault recovery control scheme is validated through simulation.

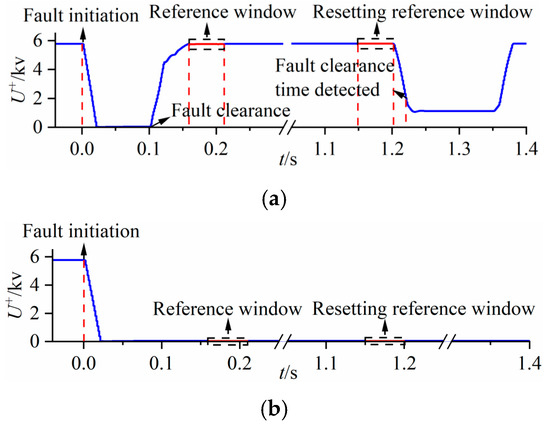

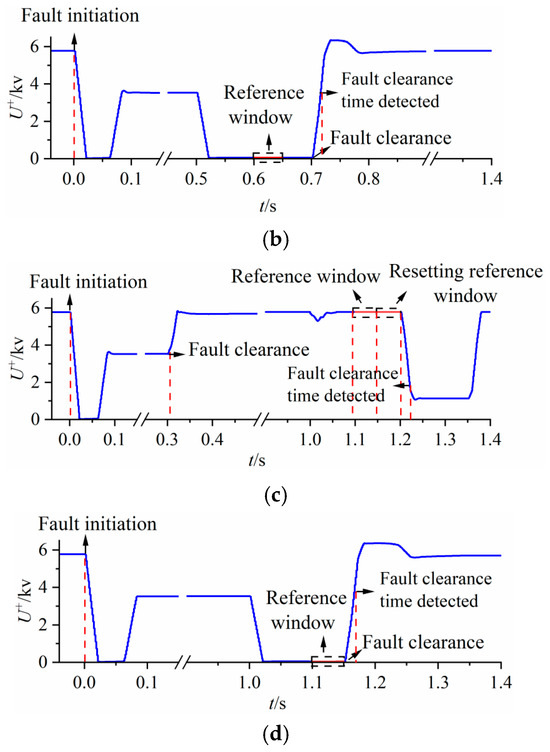

Taking position F1 as an example, the fault detection results are shown in Figure 7. Figure 7a depicts a transient fault lasting 100 ms, which self-cleared before the baseline window. Within 1.2 s after the fault occurred, no voltage relative entropy exceeding the threshold was detected. The ES adjusted its output power P to reduce the positive-sequence voltage. Resetting the reference window to the 1.15~1.2 s interval after the fault, the positive-sequence voltage decreased to 0.2 p.u. At t = 1.216 s, a threshold exceeding K = 0.095 was detected. After a 300 ms delay, reclosing occurred.

Figure 7.

Fault detection diagram at F1. (a) Instantaneous fault. (b) Permanent fault.

Figure 7b shows a permanent fault, where the measured voltage remains at a low level and the entropy value Su approaches 0, failing to reach the threshold. Finally, reclosing is locked out after exceeding the detection time to prevent secondary reclosing during a fault.

The simulation results for fault detection in the three scenarios are shown in Table 1. The fault detection diagrams for transient and permanent faults at locations F2 and F3 are shown in Figure A1 and Figure A2 of Appendix B.

Table 1.

The fault detection results of the proposed schemes under different fault locations.

The proposed cooperative fault recovery control scheme can identify fault types under various fault locations and protection operation conditions.

5.3. Verification Under Different Fault Types and Fault Resistances

To validate the proposed cooperative fault recovery control scheme system’s detection capability for different fault types and fault resistances, transient and permanent faults were simulated for three-phase faults (ABC), two-phase-to-phase faults (AB), and two-phase-to-ground faults (ABG). A eight-step transition resistance gradient was set at 0.1 Ω, 1 Ω, 10 Ω, 50 Ω, 125 Ω, 250 Ω, 375 Ω and 500 Ω. Assuming that the reference windows corresponding to each protection action can capture the steady-state voltage during transient faults, the steady-state entropy values after subsequent fault clearance are shown in Table 2. The entropy values for permanent faults are presented in Table A1 of Appendix B.

Table 2.

The entropy values of Transient faults under different transition resistances and different fault types.

For faults that self-clear before the reference window, the steady-state entropy value reaches 0.562 after undergoing variable power control during the Stage III. The results demonstrate that the proposed method can effectively distinguish fault characteristics under high resistance conditions across different fault types.

5.4. Verification Under Different Noise

Random noise is inevitably present during the actual operation of DNs, and such noise will affect the accuracy of voltage measurement. To verify the anti-noise performance of the proposed fault recovery control method, this section establishes three types of noise environments, namely 35 dB, 30 dB, and 25 dB, respectively. Taking three-phase faults (ABC), phase-to-phase faults (AB), and two-phase-to-ground faults (ABG) with a fault resistance of 10 Ω as the research objects, their transient and permanent fault conditions are considered separately. Assuming that the reference windows corresponding to various protection operations can capture the steady-state positive-sequence voltage under transient faults, the subsequently calculated steady-state entropy values are shown in Table 3

Table 3.

The entropy values under different metering noises.

For transient faults that have self-cleared before the reference window, after the variable power control in the third stage of ES, the steady-state entropy values under the three noise environments (35 dB, 30 dB, and 25 dB) are 0.563, 0.566, and 0.562, respectively. The results indicate that the proposed method can still effectively discriminate the fault nature under the condition of random noise.

6. Conclusions

To address the issue of secondary impact frequently triggered by reclosing in traditional distribution grids under high penetration of DERs, this study proposes a communication-free cooperative fault recovery control method for DNs based on staged active power injection from ES. This method first utilizes the ES converter to assist in extinguishing the fault arc. Subsequently, the ES actively injects power into the downstream distribution system to construct voltage characteristics, enabling real-time detection of fault conditions and achieving adaptive adjustment of reclosing delay. This effectively prevents DER disconnection and enhances the system’s power restoration efficiency. For transient faults, it rapidly determines fault clearance and accelerates reclosing; if a permanent fault is identified, reclosing is immediately blocked to ensure system stability. Simulation verification demonstrates that this method reliably identifies the clearance status of transient faults at different locations and types, while exhibiting strong tolerance to transitional resistance and noise. Its adaptive adjustment characteristics enable the system to outperform traditional delay strategies in fault handling speed, arc extinction effectiveness, and power supply reliability.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.Y.; methodology, B.Y. and N.W.; software, Y.G. and J.G.; validation, B.Y., N.W. and J.G.; formal analysis, N.W. and Y.G.; investigation, N.W.; resources, B.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, B.Y. and N.W.; writing—review and editing, B.Y., N.W. and J.G.; visualization, L.Z.; supervision, B.Y.; project administration, B.Y.; funding acquisition, B.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported in part by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant 52407093, in part by State Key Laboratory of Alternate Electrical Power System with Renewable Energy Sources (Grant No. LAPS24019), in part by S&T Program of Shijiazhuang under Grant 241791167A, and in part by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant 52507088.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| DNs | Distribution network |

| DERs | Distributed energy resources |

| ES | Energy storage |

| b-EMF | Back Electromotive force |

| GFM | Grid-forming |

| LVRT | Low voltage ride through |

| STATCOM | Static synchronous compensator |

| DC | Direct current |

| PCC | Point of common coupling |

| AC | Alternating current |

| CB | CB |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

For theoretical simplicity, the network downstream of the CB is maximally simplified to exclude ES.

This study analyzes the prototype network shown in Figure 2, and the proposed method can be easily extended to radial multi-branch network scenarios. Following the CB tripping, viewed from the PCC of the distributed energy to the grid side, the external circuit comprises the transformer, feeder, and load connected in series. The equivalent impedance can be given as:

Transfer the R-L-C parallel circuit of load into series circuit of resistance and reactance. ZLD can be expressed as:

where ω is the electrical angular frequency, |ZLD| is the amplitude of load impedance. Substituting (A1) into (A2), the total impedance of the external circuit can be derived as:

where R, L and C are, respectively, the total resistance, inductance, and capacitance of the equivalent circuit.

The feasibility of equivalently simplifying multiple parallel-connected GFM-ES units into a single GFM-ES unit in this paper can be supported by circuit theory and the operating principle of GFM converters: a GFM converters is equivalent to a synchronous voltage source externally, and its built-in control strategy can ensure the stability and synchronization of multiple units during parallel operation, thereby enabling the aggregated system to equivalently simulate the operating characteristics of a single large-capacity ES unit. On this basis, according to the superposition principle of power, the total active power and reactive power injected into the downstream load are equal to the arithmetic sum of the corresponding output powers of all parallel-connected GFM-ES units. This equivalent method is consistent with the simplified model adopted in this paper, which not only simplifies the fault analysis process but also ensures the accuracy of the analysis results.

Based on the above analysis, the network downstream of CB can be simplified as an equivalent circuit comprising a ES connected in parallel with an RLC branch, as shown in Figure 2. This simplification significantly reduces the analytical complexity of fault analysis arising from multi branch topology in DNs.

Appendix A.2

In this paper, when computing Su_1−2, the integral sequences of the reference window and the sliding window must first be normalized, and the normalized values of the j-th sample point for both windows are:

where and represent the actual values of the jth sampling point in the reference window and sliding detection window.

Appendix B

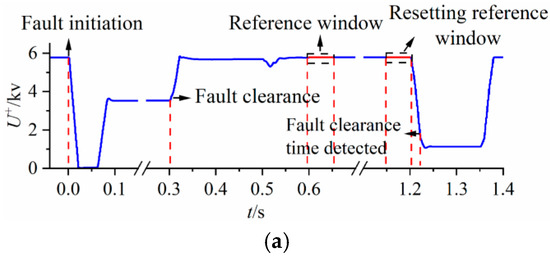

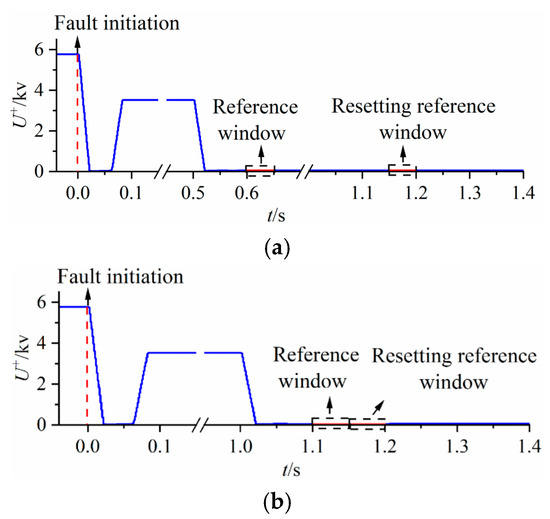

Figure A1 shows the detection results for transient faults at points F2 and F3, where Figure A1a,b correspond to fault point F2, and Figure A1c,d correspond to fault point F3. Specifically, the faults depicted in Figure A1a,c exhibited short durations, resolving spontaneously before the initial reference window commenced. After 1.2 s following fault onset, the system reset the reference window while the ES reduced voltage by controlling its output power. Upon detecting that the entropy value reached the threshold, a reclosing operation was executed after a 0.3 s delay. In Figure A1b,d, low fault voltages can be detected within the original reference window. Similarly, after the entropy value reaches the threshold, reclosing is completed following a 0.3 s delay.

Figure A1.

Transient fault detection diagrams at fault points F2 and F3. (a) Transient fault lasting for 300 ms at F2. (b) Transient fault lasting for 700 ms at F2. (c) Transient fault lasting for 300 ms at F3. (d) Transient fault lasting for 1150 ms at F3.

Figure A1a,b show detection results for permanent faults at points F2 and F3. Under such faults, the measured voltage remains persistently low, with entropy value Su approaching zero, consistently failing to reach the action threshold. Ultimately, reclosing is locked out after exceeding a 1.4 s delay to prevent secondary reclosing during the fault state.

Figure A2.

Permanent fault detection diagrams at fault points F2 and F3. (a) Permanent fault at F2. (b) Permanent fault at F3.

Table A1.

The entropy values of Permanent faults under different transition resistances and different fault types.

Table A1.

The entropy values of Permanent faults under different transition resistances and different fault types.

| Fault Resistance Value | ABC Three-Phase Fault | AB Phase-to-Phase Fault | ABG Two-Phase Ground Fault | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entropy Value | Reclosing Status | Entropy Value | Reclosing Status | Entropy Value | Reclosing Status | |

| 0.1 | 0 | ● | 0.009 | ● | 0.004 | ● |

| 1 | 0 | ● | 0.007 | ● | 0.011 | ● |

| 10 | 0.001 | ● | 0.006 | ● | 0.012 | ● |

| 50 | 0.002 | ● | 0.006 | ● | 0.011 | ● |

| 125 | 0.006 | ● | 0.009 | ● | 0.005 | ● |

| 250 | 0.007 | ● | 0.010 | ● | 0.003 | ● |

| 375 | 0.005 | ● | 0.001 | ● | 0.001 | ● |

| 500 | 0.004 | ● | 0.002 | ● | 0.001 | ● |

Note: ○ indicates the CB closes after a delay; ● indicates reclosing is blocked.

Appendix C

The rated capacity of the inverter is 100 kW, and the rated voltage/frequency is 380 V/50 Hz. The inductance of the filter is 1 mH. The rated capacity of the box-type transformer is 200 kVA, the voltage level is 10/0.38 kV, it is connected by Dyn, the short-circuit impedance is 10%, the ratio of active power of ES to load Kp is 1, the outer loop control coefficient Jwn is 0.001, Dwn is 0.04, Dq0 is 2, and K is 4. The inner loop control coefficients are Kup = 8.11, Kui = 0.003, Kip = 47.619, and Kii = 0.001.

In the simulation system, the lengths of the adjacent two distribution feeders are both 10 km. The parameters are set according to the overhead line of model JKLYJ-10-240 of a certain regional power grid. The resistance per unit length is 0.16 Ω/km, the reactance per unit length is 0.28 Ω/km, and the capacitance per unit length is 13.14 pf/km.

The capacity of the main transformer in the DNs is 1 MVA, the voltage level is 110/10 kV, it is connected by YNd, and the short-circuit impedance is 10.5%.

References

- Nikoofekr, I.; Sadeh, J. Nature of fault determination on transmission lines for single-phase autoreclosing applications. IET Gener. Transm. Distrib. 2018, 12, 903–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razavi, S.-E.; Rahimi, E.; Javadi, M.S.; Nezhad, A.E.; Lotfi, M.; Shafie-khah, M.; Catalão, J.P.S. Impact of distributed generation on protection and voltage regulation of distribution systems: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2019, 105, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meskin, M.; Domijan, A.; Grinberg, I. Impact of distributed generation on the protection systems of distribution networks: Analysis and remedies—Review paper. IET Gener. Transm. Distrib. 2020, 14, 3949–3962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakkar, M.; Bogarra, S.; Córcoles, F.; Iglesias, J.; Hanaineh, W.A. Multi-layer smart fault protection for secure smart grids. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2023, 14, 3125–3135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teimourzadeh, S.; Aminifar, F.; Davarpanah, M.; Shahidehpour, M. An adaptive reclosing scheme for preserving dynamic security in low-inertia microgrids. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2019, 10, 6228–6236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEEE Std 1547-2018; IEEE Standard for Interconnection and Interoperability of Distributed Energy Resources with Associated Electric Power Systems Interfaces. IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2018.

- Flores, S.; Bui, N.; Salmani, A.; Bello, M.; Zamani, M.A.; Katiraei, F.; Bidram, A. Impact analysis of high PV penetration on protection of distribution systems using real-time simulation and testing—A utility case study. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE Power & Energy Society General Meeting (PESGM), Montreal, QC, Canada, 2–6 August 2020; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Belčević, N.M.; Stojanović, Z.N. Using voltage signals for transient fault detection on overhead lines. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2022, 137, 107851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, K.; Lv, R. A three-phase adaptive reclosure technology for distribution feeders based on parameter identification. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2019, 34, 2173–2181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, R.; Han, Z.; Liu, S.; Gao, S. An adaptive reclosing scheme for all-parallel autotransformer traction network of high-speed railway based on multisource information. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrif. 2024, 10, 407–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, Z.; Ali, A.; Allu, A.; Antar, R. Improvement of protection relay with a single phase autoreclosing mechanism based on artificial neural network. Int. J. Power Electron. Drive Syst. 2020, 11, 505–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saad, M.; Kim, C.-H.; Munir, N. Single-phase auto-reclosing scheme using particle filter and convolutional neural network. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2022, 37, 4775–4785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Liao, W.; Bak, C.L.; Chen, Z. Active-control-based three-phase reclosing scheme for single transmission line with PMSGs. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2024, 71, 4795–4806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Song, G.; Hussain, K.S.T. Three-phase adaptive auto reclosing for single outgoing line of wind farm based on active detection from STATCOM. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2020, 35, 1918–1927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanati, S.; Azzouz, M.; Awad, A.S.A. Adaptive auto-reclosing and active fault detection of lines emanating from wind farms in microgrids. IEEE Trans. Energy Convers. 2024, 39, 389–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, C.; Li, F. Adaptive comprehensive auto-reclosing scheme for shunt reactor-compensated transmission lines. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2020, 35, 2149–2158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X. Three-phase adaptive reclosure for transmission lines with shunt reactors using mode current oscillation frequencies. J. Eng. 2018, 2018, 1012–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider Electric Industries SAS. Intermittent Transient Earth Fault Protection; Schneider Electric: Rueil-Malmaison, France, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.; Zeng, X.; Yan, L.; Xu, X.; Guerrero, J.M. Principle and control design of active ground-fault arc suppression device for full compensation of ground current. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2017, 64, 4561–4570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, X.; Liu, H.; Huang, X.; Huang, C.; Chai, C.; Rong, F. A novel single-phase grounding fault voltage full compensation topology based on antiphase transformer. IET Gener. Transm. Distrib. 2021, 15, 2893–2904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Zhang, W.; Xiao, X. Faulted terminal open-circuit voltage controller for arc suppression in distribution network. IET Gener. Transm. Distrib. 2020, 14, 2763–2770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, H.C.; Tian, K.Q.; Yang, Z.H.; Dai, Y. Novel active arc suppression and protection technology for distribution networks based on LPT injection. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2025, 248, 111922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catlett, R.; Lang, M.; Scala, S. A Novel Approach to Arc Flash Mitigation for Low Voltage Equipment. In Proceedings of the IEEE Electrical Safety Workshop (ESW) 2016, Jacksonville, FL, USA, 6–11 March 2016; IEEE: New York City, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, Y.C.; Jiang, F.; Guo, Q.; Tu, C.M.; Wang, L.; Wang, X.; Xiao, F. Adaptive Active Voltage-Type Arc Suppression Strategy Considering the Influence of Line Parameters in Active Distribution Network. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2023, 70, 4799–4808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEEE Standard C57.13-2016; IEEE Standard Requirements for Instrument Transformers. IEEE Standards Association/IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2016.

- Rojnić, M. A Comprehensive Assessment of Fundamental Relay Operating Times. Energies 2022, 15, 1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.