Abstract

This paper presents a Genetic Algorithm-based Home Energy Management System designed to exploit the energy flexibility of user-dependent loads by identifying and recommending optimal operating schedules that minimize electricity costs. To determine the most advantageous 15 min activation slot for the following day for each load, the algorithm uses as input the forecasted consumption profile of non-optimizable loads and photovoltaic generation, both obtained through an LSTM-based model, along with the contracted power, applicable tariffs, and the load profiles of the selected appliances. Unlike previous approaches, the proposed framework allows users to select which loads to optimize and define specific operational constraints. Additionally, a user-friendly interface was developed to facilitate seamless interaction between the user and the system. To validate the proposed framework, a case study was conducted on a residential household with four occupants located in Portugal, considering user-dependent flexible loads such as a washing machine, tumble dryer, and dishwasher. The results demonstrated that the developed system operated effectively, reducing electricity costs by approximately 9% compared to a scenario without the proposed solution.

1. Introduction

Global warming is becoming increasingly evident, as demonstrated by the steady rise in the Earth’s average temperature [1]. This trend is largely driven by the combustion of fossil fuels for energy production, which releases significant amounts of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere [2]. As global energy demand continues to increase, a crucial factor in economic growth, the transition toward renewable energy sources has become more important than ever [3]. However, the variable nature of renewable sources such as solar and wind power makes it difficult to consistently meet building energy requirements.

Additionally, energy consumption patterns have changed significantly due to the increasing electrification of sectors such as transport and heating [4,5,6]. While electrification improves environmental performance and energy efficiency, it also poses challenges. Rising electricity demand can strain distribution networks not designed for such loads, leading to demand peaks and requiring major infrastructure investments. Moreover, without intelligent demand management, large-scale electrification can cause imbalances between supply and demand, making it harder to integrate variable renewable sources like solar and wind power [7].

In this context, exploring load flexibility emerges as a strategic approach to mitigate the challenges posed by electrification and to facilitate the more efficient integration of renewable energy sources. As buildings account for about 33% of global energy consumption, exploring the energy flexibility of their loads becomes particularly relevant. Leveraging this flexibility can play a key role in reducing carbon emissions, facilitating the integration of renewable energy sources, and minimizing peak demand caused by the electrification of certain loads [4].

2. Literature Review

Energy flexibility can be defined as a system’s capacity to modify its energy consumption or generation based on specific goals, while maintaining technical limitations and ensuring user comfort [8]. This flexibility is largely dependent on the characteristics of the loads connected to the electrical system. Loads like security systems need an uninterrupted power supply to guarantee the safety of property and individuals. Therefore, their consumption patterns cannot be altered, making them unsuitable for energy flexibility. Consequently, this type of load is categorized as non-flexible, inflexible, or inelastic, depending on the terminology used by the author. On the other hand, heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC) systems can adjust their operation throughout the day. During times of reduced grid demand or increased renewable energy generation, such as sunny periods, air conditioning or heating can be utilized more intensively to pre-cool or pre-heat spaces, thereby lowering energy consumption during peak hours. This can be achieved without compromising thermal comfort, provided that intelligent control and thermal storage strategies are implemented [9]. This kind of load may be described as flexible or elastic. Nevertheless, categorizing residential loads merely as flexible or non-flexible can be overly simplistic, as it overlooks the diversity and complexity of energy usage behaviors within a household.

2.1. Subclassification of Flexible Loads

Although the distinction between flexible and non-flexible loads may seem straightforward, typically based on the question, “Is it possible to shift the load in time without violating technical constraints or reducing user comfort?”, this simple separation is not always sufficient. Flexible loads can present different degrees of flexibility that a binary classification fails to capture. As a result, various researchers have introduced more refined and representative classification models that better align with real-world scenarios.

Xiong et al. [10] propose a classification of flexible loads into two main categories based on their level of controllability. The first group is non-interruptible devices, which can be delayed but must complete their cycle once started, such as washing machines and dishwashers. The second group is interruptible loads, which can be postponed or temporarily stopped and resumed without losing functionality, such as robotic vacuum cleaners and rechargeable devices like electric vehicles (EVs) and smartphones. In a similar effort, Yang et al. [11] introduce a model that classifies flexible residential loads into two types: adjustable appliances, which allow power modulation in line with user preferences (e.g., air conditioners), and time-shiftable appliances, which can be scheduled to run at different times, like washing machines. Still based on operational criteria, Saavedra et al. [12] suggest a more detailed classification, organizing flexible loads into five categories: interruptible, non-interruptible, time-shiftable, adjustable, and thermal loads. The latter, such as HVAC systems, can be modulated without significantly compromising comfort, thanks to thermal inertia, as previously mentioned [9]. Reis et al. [13] adopt a similar structure but omit the adjustable load category from their framework.

In addition to this categorization, three other distinct classifications were identified. Qiao et al. [14] offer an alternative perspective by classifying flexible loads according to their function within the demand response (DR) process. The loads are divided into three categories: translational, transferable, and reducible. Translational and transferable loads closely correspond to the previously described non-interruptible and adjustable appliance categories, respectively, while reducible loads, such as lighting, can lower power use, shorten operation, or pause temporarily without affecting overall system performance. The approach presented by Akbari et al. [15] classifies flexible loads based on the type of control applicable to them, dividing them into three main groups: thermostatically controlled loads, programmable appliances, and energy storage systems. Thermostatically controlled loads, such as HVAC systems and water heaters, work within set temperature ranges, allowing energy adjustments without affecting comfort. Programmable appliances, like washing machines and dishwashers, can be scheduled to run during low-demand or low-cost periods. Energy storage systems, such as home batteries and EVs, provide flexibility by storing and supplying energy, helping to balance supply and demand. Lastly, Tamilarasu et al. [16] propose yet another classification for flexible loads, organizing them based on two key characteristics: controllability and shiftability.

Notably, none of these classifications considers the aspect of user interaction. Considering this, a new characterization method for flexible residential loads will be defined and adopted, emphasizing user interaction. To illustrate this perspective, consider a typical household with common appliances such as a washing machine and a pool filtration pump. While both are generally classified as flexible loads, their degree of flexibility varies significantly depending on the level of user interaction required. Regarding the washing machine, its operation requires active user involvement, such as loading clothes, adding detergent, and selecting the wash cycle. To align its use with off-peak tariffs or periods of high solar energy availability, these preparatory steps must first be completed. However, user behavior is influenced by internal factors, such as fatigue, limited time, or lack of motivation, and external factors, like unexpected schedule changes. These variables make usage patterns unpredictable, reducing the washing machine’s actual flexibility in practice. On the other hand, the swimming pool filtration pump has a different operational profile. According to the Associação Portuguesa de Profissionais de Piscinas [17], a full daily filtration cycle is required to maintain water quality. This cycle can be scheduled automatically, requiring minimal user interaction aside from occasional maintenance. This shows that, while both loads are technically classified as flexible, their actual operational flexibility depends on the level of user involvement. Table 1 summarizes the classification used in this paper, categorizing loads according to their dependence on user intervention.

Table 1.

Classification of residential loads based on the degree of dependence on user interaction.

2.2. Demand Response for Fully User-Dependent Loads

Although user-dependent flexible loads have high theoretical potential for demand-side management, their actual flexibility depends less on technical features and more on the user’s willingness to adjust usage without affecting comfort or routines. For instance, although a dishwasher could run at night when electricity is cheaper and demand is lower, users often run it after dinner due to convenience or concerns such as nighttime noise. Consequently, the main challenge in maximizing appliance flexibility is not technological but behavioral. Real energy benefits rely on understanding and guiding user behavior for effective participation in flexible energy programs.

Despite these challenges, user-dependent flexible loads merit greater research attention given their widespread presence in residential settings. Although frequently addressed within DR strategies, user involvement in these studies is often treated superficially or in overly general terms. This limited consideration of actual user behavior and preferences can reduce the relevance and applicability of proposed solutions in real-world residential contexts. Wang et al. [18] proposed a framework where the scheduling of these types of loads relies on predefined operating intervals. However, the study does not explain how these intervals were determined. Li et al. [19] proposed a framework where the optimization of these types of flexible loads is performed within fixed time windows based on assumed usage patterns. The study does not explain how these intervals were defined, which reduces the transparency and adaptability of the approach. Yi et al. [20] presents a similar framework but incorporates a more detailed user model that distinguishes between working individuals and retirees, allowing a more realistic representation of user behavior. Still, the assigned time windows rely on generalized assumptions rather than observed household routines.

Additionally, the revised methods treat all these loads as a single unit within the communities, without adapting control strategies to specific appliances or user preferences. This generalization overlooks the diversity of household routines, such as those of residents working night shifts or from home, making a one-size-fits-all solution less effective. By ignoring individual differences, such models reduce the accuracy and real-world applicability of their results. Thus, the frameworks do not offer concrete recommendations to help users adapt their behavior to meet the proposed optimization goals; instead, they merely indicate the potential flexibility of the loads under study. Considering these challenges, it becomes imperative to develop more advanced and nuanced models of occupant behavior to improve the scheduling of residential flexible loads. These models must reflect the wide range of user routines and the inherent complexity of everyday household activities. To be truly effective, they should be integrated with energy optimization algorithms that are not only technically sound but also designed with the end user in mind. This includes intuitive, user-friendly interfaces, clear and transparent communication of energy goals, and compelling incentives that encourage active participation. By aligning technical optimization with real-world human behavior, these models can significantly enhance both the effectiveness and acceptance of demand-side management strategies.

Taking this into account, it was possible to identify some frameworks in which the authors provide individual, load-specific suggestions to users based on their preferences. In [21], Luo et al. propose a model that determines day-ahead optimal schedules for user-dependent loads over a 24 h period, such as in the morning or late afternoon. Luo et al. [22] and El Makroum et al. [23] present similar models that recommend a 60 min operating window. The framework proposed by Soares et al. [24] optimizes the operating schedules of this type of flexible loads for the next 36 h. In [25], Patrício et al. develop a framework similar to those presented in [21,23,24], but provide the exact minute of the following day at which each load should start operating in order to minimize cost. Lastly, Urrutia et al. [26] propose a framework capable of suggesting variable operating intervals based on photovoltaic (PV) generation forecasts, low demand periods, or other favorable conditions.

2.3. Research Gaps and Contributions

Although the reviewed studies have made valuable progress in addressing the previously identified challenges, notable gaps persist in the literature and warrant further investigation:

- Existing works rely on fully automated optimization processes that exclude any form of daily user routine adaptation. Although many approaches are based on typical user routines or insights from interviews, the devices used in the optimization remain static, failing to adapt dynamically to day-to-day variations in user behavior. For example, the washing machine is usually not used every day. Allowing users to indicate whether they intend to use it the next day would enable the optimization process to better align with their actual needs.

- None of the reviewed frameworks allow users to define short-term preferences/constraints for individual loads. For instance, there may be occasions when the washing machine needs to operate within a particular time window that differs from the household’s typical routine.

- The temporal resolution used in most current approaches is limited. Most studies use 60 min time windows for appliance scheduling, although electricity billing in many countries is based on 15 min intervals, causing potential mismatches with tariff periods. In contrast, the study [25] applies a minute-by-minute resolution, which increases granularity but reduces forecast reliability. A 15 min resolution would offer a practical balance, aligning with common billing structures while ensuring accurate load scheduling.

- None of the previous studies mentions a user interface. The closest example is [26], which only includes a message-sending feature to convey suggestions.

To address the gaps identified, this paper, under the scope of the European Project COMMUNITAS [27], funded by the H2020 program (Grant Agreement No. 101096508), and in light of identified research gaps, a Genetic Algorithm (GA)-based Home Energy Management System (HEMS) is proposed. The system aims to exploit the energy flexibility of user-dependent loads by identifying and recommending the optimal operating schedules that minimize energy costs. Unlike previous approaches, this framework allows users to select which loads to optimize and define specific conditions for their operation. As a result, the system returns, for each selected load, the most advantageous 15 min time slot for activation the following day. Both load selection, constraints, and results can be defined/seen through a user interface. The HEMS was subsequently applied through simulation to validate its practical applicability.

3. Methodology

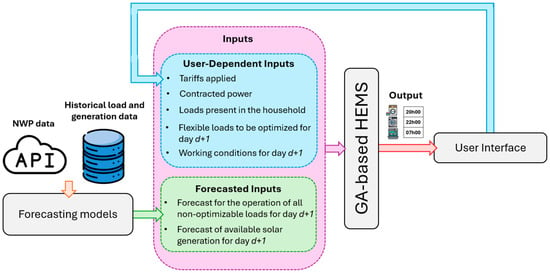

The HEMS developed in this work aims to exploit the energy flexibility of user-dependent flexible loads by identifying and recommending an optimal operating schedule for each, thereby reducing the associated costs. Accordingly, the system requires specific inputs. Regarding user interaction, several long-term inputs are required, such as the contracted power (to prevent cost increases and, consequently, higher tariffs), the type of tariff applied (time-of-use (ToU) with one, two, or three periods), and the appliances present in the household that fall under the category of user-dependent flexible loads. Based on Berg et al. [28], washing machines, dishwashers, and dryers are recognized as having the highest demand-reduction potential and penetration rates within this category [29,30,31]. Therefore, the HEMS was designed specifically to optimize these three types of loads. However, users can include any number of such appliances in their household (e.g., two washing machines, one dryer, and one dishwasher). Daily, the user must indicate which appliances they plan to use the following day (e.g., for tomorrow, just one washing machine and the dryer) and, if desired, define specific operating conditions for each selected load. Finally, the HEMS also requires the forecasted consumption profile of non-optimizable loads by the framework, which includes non-flexible loads and flexible loads that are not user-dependent, as well as PV generation, both obtained through a Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) model. Both the user-dependent inputs and outputs are managed and communicated to the user through the developed interface.

Figure 1 provides an overview of the HEMS, illustrating the entire process from input specification and processing to solution calculation through the GA and the subsequent communication of these solutions to the user. These processes are discussed in greater detail in the following sections: Section 3.1 explains how the forecasts for the consumption of non-optimizable loads and PV generation are obtained; Section 3.2 describes the process of generating optimal solutions; and Section 3.3 focuses on how these solutions are communicated to the user, as well as on the collection of the user-dependent inputs.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation and functional overview of the developed HEMS.

3.1. Time-Series Forecasting

To provide day-ahead operating schedule recommendations for the user-dependent loads, forecasts of both the electricity consumption of the non-optimizable loads and PV generation are required. Based on the work reported in [32], forecasting models were developed to simulate a realistic day-ahead forecasting scenario at the required temporal resolution, enabling evaluation of optimization strategies under conditions representative of actual deployment. Residential-level forecasting is considerably more challenging than aggregate load forecasting due to the high stochasticity inherent in individual household consumption and generation patterns [33]. This increased variability stems from unpredictable occupant behavior, sporadic appliance usage, and the relatively small scale of PV installations, which magnifies the impact of local weather variations. Despite these challenges, accurate residential-level forecasts are essential for effective DR and optimization of flexible loads in distributed energy systems.

The forecasting workflow comprised a sequence of standard steps: data collection and preprocessing, model training and validation, selection of the best-performing architecture, and integration into the scheduling optimization framework. These will be described in the following subsections.

3.1.1. Data Collection and Pre-Processing

Electricity consumption from the non-optimizable loads and PV generation data were collected from a residence (further described in Section 4) from the 1st of January 2024 to the 30th of September 2025, at one-minute resolution. Missing timesteps were handled by either (a) removing data for the entire day when multiple consecutive timesteps were missing or (b) linearly interpolating between adjacent timesteps for isolated missing values. This resulted in 557 complete days of electricity consumption data and 534 complete days of PV generation data. Given the infeasibility of minute-resolution forecasts at a 24 h horizon and the necessity of sufficient temporal resolution to optimize scheduling, data were resampled to 15 min resolution by averaging values within each interval.

Numerical Weather Prediction (NWP) forecasts from the ICON Global, Météo-France ARPEGE Europe, and ECMWF IFS models were used as exogenous variables, collected via the Open-Meteo API [34], to maintain consistency with operational day-ahead forecasting conditions. Additional temporal features, including hour of day, day of week, and month, were encoded using sine-cosine pairs to preserve cyclical continuity, as detailed in Equations (1)–(6), where h represents the hour, m the month, d the day, the number of days in month m, and the encoded day of the week (0 to 6).

3.1.2. Long Short-Term Memory, LSTM

Unlike traditional feedforward neural networks, Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs), are designed to recognize patterns in sequential data, such as time series. This capability allows RNNs to maintain information about previous inputs through their internal state, making them effective for tasks where context and order are crucial.

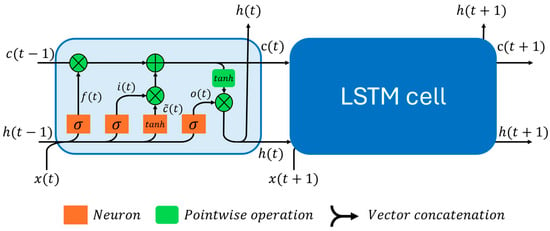

The LSTM network, introduced by Hochreiter and Schmidhuber [35], was designed to address the vanishing and exploding gradient problems inherent to earlier RNN architectures. Standard RNNs trained with backpropagation through time (BPTT) exhibit exponential decay (vanishing) or growth (explosion) of back-propagated error signals, resulting in slow learning or unstable weights, limiting their ability to learn long-term temporal dependencies LSTM addressed this through a constant error carousel (CEC), maintains a constant error flow through internal states. Later, Gers et al. [36] subsequently expanded the LSTM cell by introducing the forget gate, enabling the cell to reset its state when stored information is no longer relevant. The mathematical formulation of the LSTM cell [37] is expressed as follows (Equations (7)–(12)):

where , , and are the weights relating to the forget gate, input gate, cell state and output gate, respectively. If is , all the information relating to the cell state for is kept, while if , it all becomes “forgotten”. All gates use a sigmoid activation function, meaning that it can output values within the to interval, which leads to only partial filtering. The input gate also decides how much of the current new input data, combined with previous recurrent information, should be stored in the cell state. The output gate decides the new hidden state based on the determined cell state summed with the previous, and the combination of the new input and the previous hidden state. Figure 2 showcases the composition of the described LSTM cell.

Figure 2.

Architecture of the LSTM cell.

The proposed architecture follows an established LSTM-based approach for forecasting the electricity consumption of non-optimizable loads [38] and PV generation [39]. The network consists of stacked LSTM layers that learn temporal dependencies from the input sequences, followed by fully connected layers that perform the regression mapping from the learned hidden representations to the forecasted output values.

3.1.3. Model Training and Validation

The proposed model architecture was designed to generate day-ahead forecasts at 15 min resolution using a supervised learning approach. The input features consist of historical consumption or generation observations from a lookback window, and NWP forecasts with engineered features corresponding to the 24 h forecast horizon. This configuration ensured that the model used only information available in operational settings.

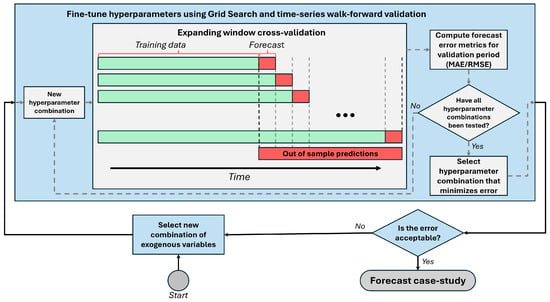

Figure 3 illustrates the hyperparameter tuning and model validation workflow. The model was trained and validated using an expanding window walk-forward validation scheme, which incrementally expands the training set at each fold, preventing information leakage and providing a realistic evaluation under operational conditions. Validation was performed from 1 January to 30 April 2025, using four consecutive 30-day test folds. The first fold used data from 1 January to 31 December 2024, for training and generated forecasts for 1 January to 30 January 2025. Each subsequent fold expanded the training window by 30 days and evaluated the following 30-day period, simulating monthly model updates.

Figure 3.

Model training and validation scheme.

For each exogenous variable combination, hyperparameters were optimized through grid search. Each hyperparameter configuration was evaluated by computing forecast error metrics, namely Mean Absolute Error (MAE) and Root Mean Square Error (RMSE), across all validation folds, and the combination yielding the lowest average error was selected. If the resulting error was not acceptable, a new exogenous variable combination was tested and the process repeated. Table 2 presents the optimal hyperparameters for the final LSTM architecture. The search space encompassed architectural parameters (number of LSTM layers, number of units per layer, dropout rate for regularization, and number of units in the TimeDistributed Dense layer with Rectified Linear Unit (ReLU) activation), input configuration (lookback window length in days), and training parameters (number of epochs, batch size, and learning rate). Performance was assessed using the normalized Root Mean Square Error (nRMSE) and normalized Mean Absolute Error (nMAE), as defined in Table 3.

Table 2.

Final architectures of the forecasting models for non-optimizable load consumption and PV generation.

Table 3.

Considered forecasting validation metrics.

The optimal lookback window was 3 days for consumption forecasting and 1 day for generation forecasting, reflecting the distinct nature of PV generation, which is predominantly determined by meteorological conditions rather than prior generation patterns. Exogenous feature selection is presented in Table 4. For PV generation forecasting, NWP variables including temperature, global tilted irradiance, and cloud cover were retained, while wind speed and precipitation were excluded due to negligible impact. The consumption forecasting model relied solely on temporal and calendar features, as NWP variables did not improve accuracy.

Table 4.

Selected exogenous features by the forecast model.

A model comparison benchmarked the LSTM architecture against Naïve persistence, Prophet, and CNN-LSTM (Table 5). For a fair comparison, all benchmark models were trained and validated using the same pipeline described above, with hyperparameters optimized through grid search across the same validation folds. The LSTM model slightly outperformed CNN-LSTM on both tasks, while Prophet achieved marginally lower nRMSE but higher nMAE for generation forecasting. Adopting LSTM for both forecasts enabled a unified framework, simplifying implementation through a single architecture with task-specific hyperparameter tuning.

Table 5.

Forecast validation errors per optimal model.

3.2. Genetic Algorithm-Based Home Energy Management System for User-Dependent Flexible Loads

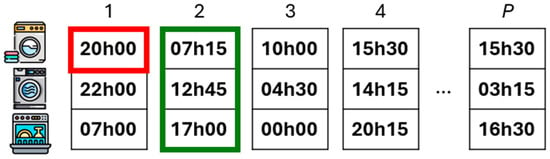

Considering the wide applicability of GAs to complex optimization problems and their ability to explore vast solution spaces efficiently and adaptively, a generic GA was adapted to meet the specific requirements and objectives of this study. A crucial step is to define what constitutes a gene, a chromosome, and the population in the context of the problem. Within this framework, a gene was defined as the specific time at which a household appliance should be activated. This representation was chosen due to the discrete and temporal nature of the problem, where the main decision variable is the start time of each load’s operation. Since the flexibility of these loads lies in their ability to shift operation within a user-prescribed and limited time window, modeling each gene as a time slot provides a simple and effective way to encode possible solutions. A chromosome, in turn, corresponds to a complete scheduling scenario, that is, the combination of start times for all the flexible loads under consideration. It is composed of n genes, where n represents the total number of user-dependent flexible loads. Finally, a population consists of a set of P distinct chromosomes, each representing a possible solution to the scheduling problem. To facilitate a better understanding of the concepts presented, a household with a washing machine, a tumble dryer, and a dishwasher was considered, and an illustrative example is provided in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Example of a population generated by the GA, showing in green one of the P chromosomes that compose the population and in red an example of the genes within a chromosome.

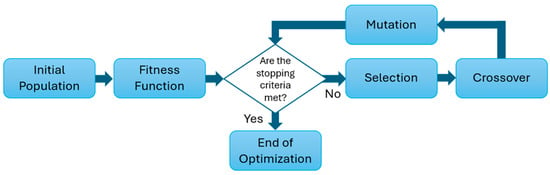

As shown in Figure 5, the GA is composed of several processes, the first of which concerns the creation of the initial population. In this problem, an initial population is generated randomly, consisting of P chromosomes, where each gene can be assigned a value between 00h00 and 23h45. Once created, the initial population is then evaluated through the Fitness Function.

Figure 5.

Schematic representation of the GA structure.

Another crucial step involves defining the Fitness Function. This process is particularly important, as it quantifies how well each chromosome meets the defined objectives, guiding the evolutionary process by allowing the algorithm to prioritize the most promising solutions and progressively refine the scheduling strategy. Considering that the optimization of flexible load operation aims to minimize the costs associated with their usage, while simultaneously respecting the constraints defined by the user and the contracted power, it is essential that all these aspects are properly incorporated into the Fitness Function. Thus, the Fitness Function (Equation (13)) can be expressed as follows:

where the variable Fitness_Score denotes the score assigned to each chromosome. The variables General Consumption Costs and Penalty refer to the costs associated with the household’s total energy consumption and the penalties resulting from the combination of appliance operation schedules, respectively.

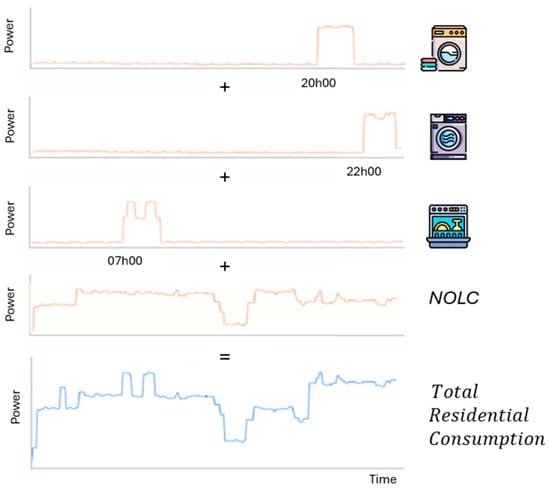

To calculate the General Consumption Costs, it is necessary to perform some auxiliary calculations using the following inputs: forecasted consumption of the non-optimizable loads, forecasted available PV generation, applicable tariffs, flexible loads to be optimized, and their respective load profiles. First, it is necessary to calculate the Total Residential Consumption associated with the given solution/chromosome. This can be obtained using the following equation (Equation (14)):

where NOLC represents the forecasted consumption of the non-optimizable loads, obtained through input data, and FLC refers to the consumption associated with the flexible loads considered in the optimization (obtained from the chromosomes). To aid comprehension, Figure 6 illustrates the previously referenced example, providing a visual explanation of the procedure based on the first chromosome presented in Figure 4. The sum of the first three consumption diagrams corresponds to the FLC variable, the fourth diagram corresponds to non-optimizable loads, NOLC, and the last to the total sum, Total Residential Consumption.

Figure 6.

Illustrative example of how to obtain the Total Residential Consumption considering a specific chromosome.

After obtaining the Total Residential Consumption, it is possible to calculate the effective consumption drawn from the electrical grid, that is, the portion that will incur a cost. As illustrated in Equation (15), this is performed by subtracting the forecasted available solar generation from the total consumption, at any given timestep k. Since the model operates with 15 min intervals, the General Consumption Costs are obtained by summing, over the 96 timesteps in the day, the product of the Grid Consumption and the respective Tariff, as showcased in Equation (16). Since the tariffs are expressed in €/kWh and each timestep represents the average kW consumed over a 15 min interval, the values must be converted to kWh by dividing by 4 before performing the cost calculation.

The Penalty variable is determined through a relatively straightforward process. It is important to note that this variable results from the sum of two distinct penalties: one associated with exceeding the contracted power limit, and another related to the violation of user-defined constraints. This situation is illustrated in Equation (17).

To calculate penalties related to contracted power, the user must specify their household’s power limit. Based on this information, and using Equation (18), a penalty is applied whenever power demand exceeds the contracted limit. This is because exceeding the contracted power may trigger the circuit breaker, automatically interrupting the power supply and making the operation under such conditions unfeasible. Therefore, a high penalty is assigned to discourage such scenarios.

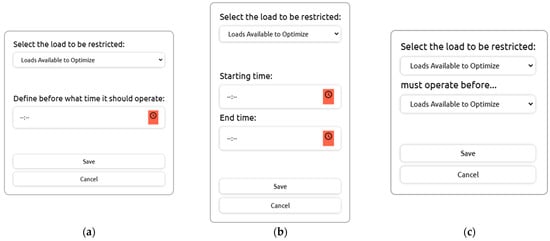

Regarding the penalties associated with user-defined constraints, these conditions must be provided beforehand as input to the system. If no restriction is imposed, the corresponding is automatically set to zero. Otherwise, if conditions are defined, they may vary across three possible types:

- The first option allows the user to define a fixed start time for a specific load, thereby opting out of leveraging that load’s flexibility (e.g., 22h15).

- The second option consists of defining a time window within which the load may start operating (e.g., between 00h00 and 02h00).

- Finally, the third option involves defining the order of operation, meaning the user specifies that one appliance must operate before another (e.g., the washing machine must run before the dryer).

The penalty calculation method for user preferences in the first and second options is based on the difference between the gene value (the start time suggested by the solution) and the time defined by the user. In the case of the third option, the logic changes slightly, with a penalty being applied if the gene representing the start time of a load is earlier than the final timestep of the load plus 1 that was designated to operate beforehand.

To aid understanding, consider the following example: suppose the user specifies that the washing machine should start at 12h00, aligning with peak solar generation. If the gene associated with that load indicates a start time of 19h00, the difference between the two times is 28 timesteps of 15 min. The same logic applies if a time interval is defined and the gene’s value falls outside the allowed window. For example, if the user defines a time window between 12h00 and 14h00 and the gene indicates 19h00, the difference is calculated relative to the nearest boundary of the interval (14h00 in this case), resulting in 20 timesteps. In the third case, let us consider a new example in which the washing machine must operate after the washer-dryer. Suppose the washer-dryer is required to start its operation at 19:00. This implies that the washing machine must complete its cycle before that time. Given that the washing machine has a duration of 2 h, it must start no later than 16:45. If the gene associated with the washing machine indicates a start time of 16:45 or earlier, no penalty is applied. However, if it suggests a start time of, for example, 20:00, a penalty is incurred. This penalty is calculated based on the difference between the proposed start time (20h00) and the latest permissible start time (16:45), resulting in a penalty value proportional to the gap (in this case, 13 timesteps). Both these differences are then divided by 10 to soften the impact of the penalty, making it more comparable in scale to typical total consumption cost values. The resulting value is then assigned to the penalty variable associated with user constraints. It is also important to note that if multiple conditions are defined for different loads and these are not respected, the penalty values are accumulated, reflecting the overall degree of non-compliance with the user’s preferences. There is also a safety mechanism that ensures the defined conditions do not conflict, allowing a new condition to be added only if it does not contradict any existing one.

Next, after evaluating the population, the stopping criteria are verified. If these criteria are met, the population is considered final, and the chromosome with the lowest Fitness_Score is returned as the optimal solution (e.g., the washing machine should operate at 12:00, the dryer at 14:00, and the dishwasher at 18:00). If not, the standard GA procedure is executed, as in any other optimization problem [40].

3.3. User Interface

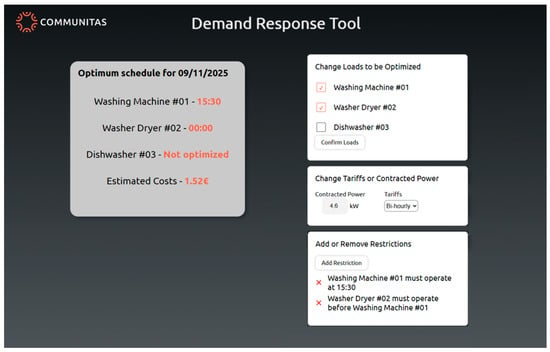

The development of a user-centered interface, which in this work also constitutes a scientific contribution, is primarily intended to support the adoption of the HEMS by enabling users to provide inputs through intuitive interactions and to receive outputs in a clear and accessible manner. According to established principles of human–technology interaction, a clear and intuitive interface enhances accessibility, reduces cognitive effort, and increases user engagement, factors that are crucial for effectively capturing and sustaining user involvement, which are often overlooked in existing HEMS solutions in the literature [41]. These considerations become even more critical given the profile of the expected end-users in the COMMUNITAS project, whose average age is approximately 44 years and who, in most cases, do not possess academic qualifications.

Thus, aligning technical optimization with user-centered platforms could greatly improve both the effectiveness and acceptance of demand-side management strategies. Figure 7 presents a screenshot of the beta version of the developed platform. To better understand how the user interface operates, how the user-dependent inputs are obtained, and when the optimal schedules are suggested, let us examine the necessary steps of the platform in chronological order.

Figure 7.

Screenshot of the beta version of the user interface developed under the European Project COMMUNITAS.

Every day at 21h00, the system is automatically triggered to calculate the optimal operating schedule for the selected user-dependent loads for the following day. This process is based on the inputs and operating conditions provided in the white boxes, while the resulting optimized schedules are displayed in the gray box. Additionally, the interface computes and presents the potential cost savings achievable through optimization by comparing the optimized results with the average activation times of the loads under non-optimized operation. In the case of Figure 7, at 21h00 on 8 November 2025, the program predicted the optimal operation of the loads to be optimized for the following day, 9 November 2025. Between 21h01 on 8 November 2025 and 20h59 on the following day, the user may change any desired inputs in the white boxes, either by modifying the loads to be optimized or by adding operating conditions. After making this change, at 21h00 on 9 November 2025, the HEMS updates the gray box with the optimal schedules for 10 November 2025. If the user does not update the inputs, the optimization will be carried out considering the previous inputs.

Regarding the addition of conditions, the process is quite straightforward. In the white box at the bottom of Figure 7, when the “Add Restriction” button is pressed, a pop-up appears allowing the user to choose from the three conditions described in the previous section. Once a condition is selected, another corresponding pop-up appears. In this case, Figure 8 shows the respective pop-ups for each condition. As also mentioned in the previous section, it is important to emphasize that any newly added condition cannot contradict an existing one. For example, if the following conditions are already defined, “Dishwasher must operate at 10h00” and “Washing machine must operate between 00h15 and 06h00”, it would not be possible to add a condition such as “Dishwasher must operate before washing machine”.

Figure 8.

Screenshot of the auxiliary pop-ups for entering conditions, where (a) refers to the condition defining a fixed start time for a specific load, (b) to an interval start time for a specific load, and (c) to a temporal condition involving two loads.

4. Case Study

To evaluate the performance of the proposed solution, a simulation was conducted using a real household as a case study over a 30-day period (September 2025) and relying on 15 min resolution time-series for both consumption and generation. The case study considers the consumption of non-flexible loads in a real household, inhabited by a family of four in Portugal. In this household, a washing machine, a tumble dryer, and a dishwasher are present, and were thus included as user-dependent flexible loads in the optimization process. An EV is also present, but although it can be considered a user-dependent load, as it requires the user to plug in the charger, it was excluded from the optimization based on two factors: EV flexibility typically involves (1) rescheduling the charging period and/or (2) bidirectional battery control. Regarding rescheduling, because EVs have high power demand and must generally be fully charged in the morning, their schedule would be largely fixed, usually at night, limiting flexibility. Concerning bidirectional control of the battery, since the framework only provides recommendations for optimal load operating schedules, implementing bidirectional management falls outside the scope of the framework. Therefore, the EV was classified as a non-optimizable load, together with non-flexible loads. The dwelling has a contracted power of 6.9 kVA and operates under a time-of-use (ToU) electricity tariff with three periods, with energy prices of 0.1058 EUR/kWh during off-peak hours, 0.1702 €/kWh during half-peak hours, and 0.3161 EUR/kWh during peak hours. It is also equipped with a south-oriented PV installation with a rated capacity of 1320 wp, whose generation profile is also considered in the study.

For the utilization of user-dependent flexible loads, assumptions were established based on typical household usage patterns reported in the literature. According to [42], approximately 80% of European households with a dishwasher use it around seven times per week; therefore, daily operation of this appliance was considered. Based on [43], the washing machine performs an average of 3.3 cycles per week, which was adopted in this study. The tumble dryer, being less common in Portuguese households, was assumed to operate only once per week, specifically on Sundays [30]. Additionally, the load profile of each user-dependent flexible load was derived using the Richardson model [44].

Regarding the GA employed in the optimization of this case study, it is essential to define the parameters associated with the selection and mutation operators, as well as the algorithm’s stopping criteria. In this context, the top 10% of individuals in the population are selected, and a mutation probability of 30% is applied. The evolutionary process ends when a maximum of 100 generations is reached or, alternatively, when the Fitness_Score shows no improvement over 30 consecutive generations. Each population consists of 50 chromosomes.

5. Results

To assess the applicability of the GA-based HEMS and the influence of forecasting on the outcome, three distinct scenarios were simulated. These scenarios and their corresponding results are described and presented in the following sections.

5.1. Reference Scenario

The reference scenario aims to represent conditions as close to reality as possible prior to the application of the proposed solution in order to explore the energy flexibility of user-dependent loads. This scenario serves as a baseline for comparison with alternative scenarios.

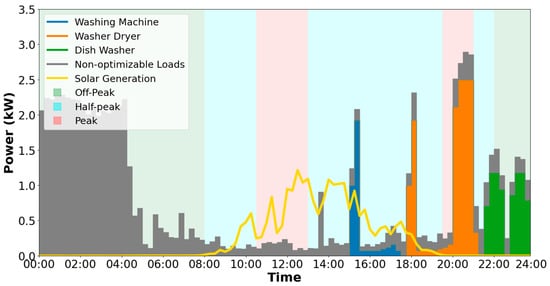

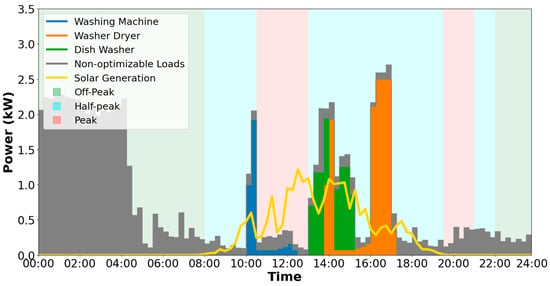

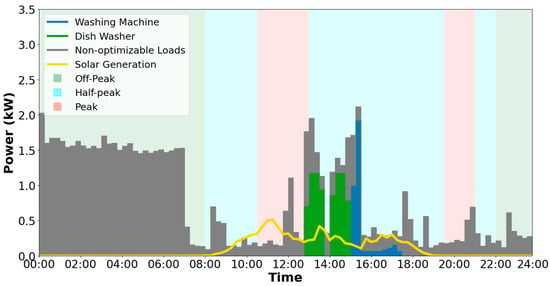

As for the usage of the loads in this scenario, since their operation is not optimized, specific average schedules were assumed. The dishwasher is considered to operate daily at around 21h30, right after dinner. The washing machine is assumed to run on Wednesdays at 18h30, after working hours, to wash clothes accumulated during the first days of the week, and again on Saturday and Sunday at 21h00 and 15h00, respectively, to simulate deeper laundry cycles. The tumble dryer is assumed to operate on Sundays at 17h45, reflecting the typical need to quickly dry clothes in preparation for the upcoming week. Figure 9 and Figure 10 illustrate the load behavior on a Sunday and a Wednesday, specifically 7 and 24 September 2025, respectively. At the end of the 30-day period, the monthly electricity bill amounted to EUR 58.92.

Figure 9.

Household reference consumption for 7 September 2025.

Figure 10.

Household reference consumption for 24 September 2025.

5.2. Genetic Algorithm Application

This scenario involves the application of the GA-based HEMS, aiming to explore the energy flexibility of the user-defined flexible loads to reduce their associated costs. Following the methodology described in Section 3.1, the household’s non-optimizable loads consumption and PV generation forecasts are obtained, with the errors of these forecasts for the considered timeframe represented in Table 6. Using these inputs, along with the remaining user-defined parameters, the framework determines the optimal operating hours for the flexible loads. It is also worth noting that, in addition to the mandatory inputs, such as contracted power and ToU, two specific conditions are applied on Sundays: the washing machine must operate between 09h00 and 19h00, and the washing machine must operate before the dryer. Once the optimal schedules are determined, they are applied to the actual consumption data to calculate the corresponding costs.

Table 6.

Forecasting errors for the case-study period.

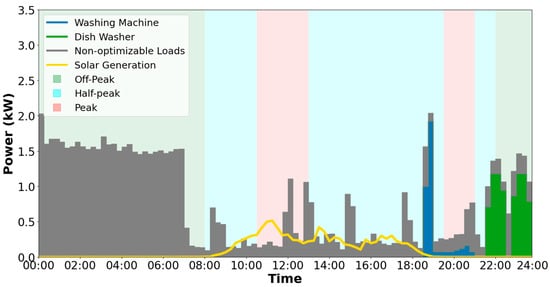

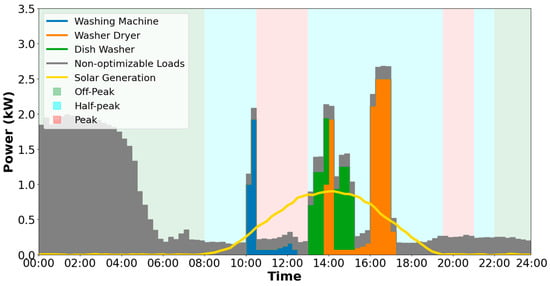

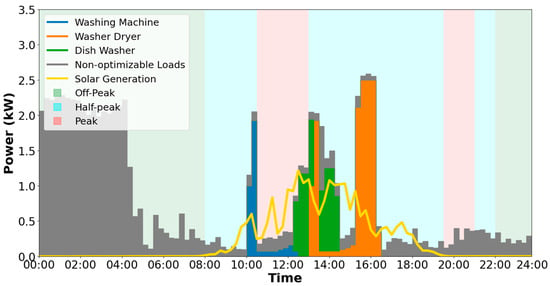

Figure 11 and Figure 12 present the non-optimizable load consumption and PV generation forecasts for 7 and 24 September 2025, along with the recommended optimal operating schedules, respectively. For 7 September, the optimization results assigned the washing machine to 10h00, the tumble dryer to 13h45, and the dishwasher to 13h00. On 24 September, as mentioned, only the washing machine and the dishwasher were used, with the washing machine scheduled for 15h00 and the dishwasher for 12h45. Figure 13 and Figure 14 show the actual non-optimizable load consumption and PV generation for the same day, as well as the operation of the flexible loads following the optimization. Applying the algorithm resulted in household energy consumption costs totaling EUR 53.86 for the 30-day period.

Figure 11.

Optimal schedule determined by the HEMS using the consumption and PV forecasts for 7 September 2025.

Figure 12.

Optimal schedule determined by the HEMS using the consumption and PV forecasts for 24 September 2025.

Figure 13.

Implementation of the optimal schedule with the actual data from 7 September 2025.

Figure 14.

Implementation of the optimal schedule with the actual data from 24 September 2025.

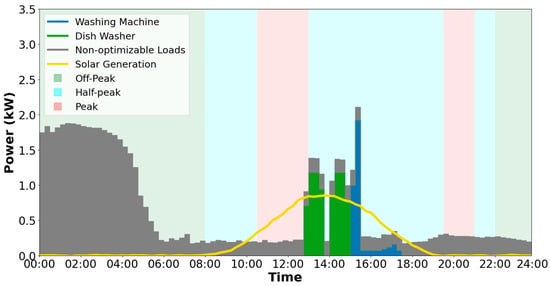

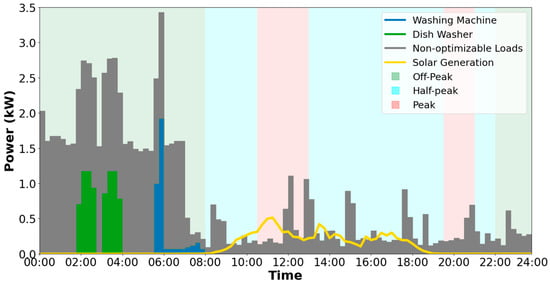

5.3. Optimization with the Actual Data

Finally, in the third scenario, the optimal operating schedule for the three loads under study was calculated using perfect forecasting, that is, the actual consumption for the respective day. All other variables and conditions remain the same as in the previous scenario. For 7 September 2025, the optimization results assigned the washing machine to 10h00, the tumble dryer to 13h00, and the dishwasher to 12h15, whereas for 24 September 2025, the optimization results assigned the washing machine to 05h30 and the dishwasher to 01h45. Over the 30-day period, the associated cost amounted to EUR 52.85. Figure 15 and Figure 16 show the optimal utilization schedule for the flexible loads based on the real data for 7 and 24 September 2025, respectively.

Figure 15.

Optimal schedule determined by the HEMS using the actual consumption and PV generation data for 7 September 2025.

Figure 16.

Optimal schedule determined by the HEMS using the actual consumption and PV generation data for 24 September 2025.

5.4. Discussion

By comparing the results obtained in the second scenario with those of the reference scenario, the effectiveness of the proposed solution can be observed, showing a clear reduction in energy-related costs. Specifically, the total cost decreases by 8.59%, from EUR 58.92 to EUR 53.86, when the solution is applied. Considering this average monthly saving, over the course of a year, this reduction corresponds approximately to the equivalent of one full month of electricity at no cost. This reduction is possible because the GA-based HEMS seeks schedules that maximize PV self-consumption or take advantage of lower electricity tariffs. Figure 11, Figure 12, Figure 15 and Figure 16 clearly illustrate this behavior, showing the predicted optimal operating schedule, in which the system aims to operate all flexible loads using PV generation, and when that is not possible, to shift them to periods with lower tariffs. In addition, this is achieved while respecting all imposed conditions, whether technical or user-defined. Again, an example of this can be seen in the previously mentioned figures, where the conditions “washing machine must operate between 09h00 and 19h00” and “washing machine must operate before the dryer” are always respected, and the contracted power never exceeds the agreed-upon value. This occurs because, although the algorithm does not explicitly optimize for contracted power or other user-defined constraints during the creation of the initial population or across successive generations, any solution that does not respect these conditions is penalized within the Fitness Function. Such solutions are immediately excluded from consideration.

Regarding the impact of forecasting on the results, this can be assessed by comparing the second scenario and the third scenario. Although the forecast does not significantly impact the optimal scheduling on most days, including 7 September, there are days when it causes the schedule to deviate from the true optimum. An example can be seen in Figure 12 and Figure 14, regarding 24 September, where the forecast model overestimates local PV generation, leading to the scheduling of flexible loads during this period. In this case, the optimal period would be during the night, when the off-peak tariff is applied, as shown in Figure 16. These differences over the course of the month result in a 1.88% cost variation between the two scenarios. Thus, the improvement of load forecasting is therefore a priority; however, achieving substantial accuracy gains at the residential level is inherently challenging due to the stochastic nature of individual load profiles. This suggests that the proposed optimization framework would be particularly effective at community or aggregate levels, where load forecasting benefits from lower variance through statistical aggregation. Although this analysis lies outside the scope of the present work, extending the framework to a community-scale setting would be straightforward due to its inherent scalability. This would mainly require supplying community-level forecasts (non-flexible loads and PV generation), the expected number of user-dependent flexible loads, and adjusting the contracted power to its aggregated community representation. Another way to mitigate the impact of forecasting errors would be, in future implementations, to incorporate forecast uncertainty directly into the optimization process, thereby improving scheduling robustness and reducing the risk of unnecessary costs.

Although forecasting was not the primary focus of this study, some other conclusions could be reached regarding its adequacy. While the available NWP data at day-ahead lead time (24 h) and 15 min resolution captured the overall daily generation trends, it exhibited insufficient correspondence with the short-term dynamics of the measured PV power generation. This mismatch between NWP-derived features and actual generation patterns constrained the model’s capacity to learn and forecast rapid intra-day variability accurately. Accurate historical data sourced from local meteorological stations could potentially be used to bias-correct the NWP forecasts, improving their representation of site-specific conditions and thereby enhancing their utility for the forecasting models.

6. Conclusions

This study introduces a HEMS based on a GA, developed to leverage the flexibility of user-dependent loads by determining and recommending optimal operating schedules that reduce electricity costs. For each load, the algorithm identifies the most advantageous 15 min activation period for the following day, using as inputs the forecasted consumption profiles of non-controllable loads and PV generation obtained from an LSTM-based model, along with contracted power, applicable tariffs, household loads, loads to be optimized, and specific operational constraints.

Thus, with the proposed HEMS, the authors aim to address gaps that none of the existing studies have tackled. Many previously developed systems rely on fully automated optimization processes that exclude any form of daily user input, preventing dynamic adaptation to day-to-day variations in user behavior and household conditions. Furthermore, most studies adopt 60 min time windows for appliance scheduling, even though electricity billing in many countries is based on 15 min intervals, leading to potential mismatches with tariff periods. Finally, none of the previous studies include a comprehensive user interface, with the closest example being [26], which only provides a simple message-sending feature to convey suggestions.

The results demonstrate that implementing the proposed solution can reduce the energy bill by approximately 9%, confirming its economic benefits. Furthermore, the inclusion of user-defined constraints proves effective, as shown in Scenarios 2 and 3, where all imposed conditions are successfully respected throughout the optimization process. Forecasting models were developed to accurately replicate real-world deployment conditions. Although the models exhibited non-negligible errors in both validation and case-study periods, their impact on optimal load scheduling was modest, as demonstrated by the 1.88% cost difference between forecast-based and perfect-forecast scenarios. These findings suggest that future implementations should focus on energy community and aggregate-level applications, where forecast accuracy improves substantially through statistical aggregation effects.

Given that this study falls within a relatively recent and evolving area of research, several directions for future work can be identified. In the case study, some assumptions were made regarding appliance usage patterns, specifically for calculating the reference scenario. Nonetheless, a key step would be to implement the proposed solution in a real-world case study, enabling the observation of actual appliance usage patterns, user interactions with the developed HEMS, and opportunities to further enhance the user experience. It would also be important to assess the framework’s performance across different seasons, tariff structures, and household profiles, as these factors may significantly influence the overall effectiveness of the system. Additionally, it would be valuable to evaluate the algorithm’s performance when a larger number of flexible loads are introduced, particularly in terms of computation time, as well as to investigate more complex or varied user-defined operational constraints. Finally, to avoid the large-scale installation of sensors, the incorporation of techniques such as Non-Intrusive Load Monitoring would be beneficial for distinguishing between the consumption of non-optimizable loads and user-dependent flexible loads, as well as for providing feedback on the operation of household appliances, such as identifying potential malfunctions or operational issues.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.A.L., N.A. and J.M.; methodology, J.T.P. and F.J.S.; software, J.T.P. and F.J.S.; validation, J.T.P., F.J.S. and N.A.; data curation, F.J.S.; writing—original draft preparation, J.T.P. and F.J.S.; writing—review and editing, R.A.L., N.A. and J.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the “COMMUNITAS—Bound to accelerate the roll-out and expansion of Energy Communities and empower consumers as fully fledged energy market players” project, funded by the EU Horizon Europe Programme, grant agreement no. 101096508 and by the Portuguese “Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia” (FCT) in the context of the Center of Technology and Systems CTS/UNINOVA/FCT/NOVA, reference UIDB/00066/2020.

Data Availability Statement

The data is unavailable due to privacy restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- NASA. Evidence. Available online: https://science.nasa.gov/climate-change/evidence/ (accessed on 12 November 2025).

- NASA. Carbon Dioxide Concentration|NASA Global Climate Change. Climate Change: Vital Signs of the Planet. Available online: https://climate.nasa.gov/vital-signs/carbon-dioxide?intent=121 (accessed on 12 November 2025).

- European Environment Agency. Energia. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/pt/themes/energy/intro (accessed on 12 November 2025).

- International Energy Agency. Transition to Sustainable Buildings: Strategies and Opportunities to 2050; OECD: Paris, France, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EUROPE 2020—A Strategy for Smart, Sustainable and Inclusive Growth. 2010. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/ALL/?uri=CELEX%3A52010DC2020 (accessed on 12 November 2025).

- Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the European Council, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions—The European Green Deal. 2019. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A52019DC0640 (accessed on 12 November 2025).

- Priyadarshan; Crozier, C.; Baker, K.; Kircher, K. Distribution Grids May Be a Barrier to Residential Electrification. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2410.04540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynders, G.; Lopes, R.A.; Marszal-Pomianowska, A.; Aelenei, D.; Martins, J.; Saelens, D. Energy flexible buildings: An evaluation of definitions and quantification methodologies applied to thermal storage. Energy Build. 2018, 166, 372–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Péan, T.Q.; Salom, J.; Costa-Castelló, R. Review of control strategies for improving the energy flexibility provided by heat pump systems in buildings. J. Process Control 2019, 74, 35–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, L.; Li, P.; Wang, Z.; Wang, J. Multi-agent based multi objective renewable energy management for diversified community power consumers. Appl. Energy 2020, 259, 114140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Wang, H.; Wang, T.; Zhang, S.; Wu, X.; Wang, H. Blockchain-based decentralized energy management platform for residential distributed energy resources in a virtual power plant. Appl. Energy 2021, 294, 117026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saavedra, A.; Negrete-Pincetic, M.; Rodríguez, R.; Salgado, M.; Lorca, Á. Flexible load management using flexibility bands. Appl. Energy 2022, 317, 119077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, I.F.G.; Gonçalves, I.; Lopes, M.A.R.; Antunes, C.H. A multi-agent system approach to exploit demand-side flexibility in an energy community. Util. Policy 2020, 67, 101114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, B.; Dong, J.; Xu, W.; Li, J.; Lu, F. Research and Demonstration of Operation Optimization Method of Zero-Carbon Building’s Compound Energy System Based on Day-Ahead Planning and Intraday Rolling Optimization Algorithm. Buildings 2025, 15, 836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbari, S.; Lopes, R.A.; Martins, J. The potential of residential load flexibility: An approach for assessing operational flexibility. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2024, 158, 109918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamilarasu, K.; Sathiasamuel, C.R.; Joseph, J.D.N.; Elavarasan, R.M.; Mihet-Popa, L. Reinforced Demand Side Management for Educational Institution with Incorporation of User’s Comfort. Energies 2021, 14, 2855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patrício, J.T.; Lopes, R.A.; Amaro, N.; Martins, J. Rule-Based Control Algorithm to Explore Energy Flexibility from Residential Pool Filtration Pumps. In Technological Innovation for Human-Centric Systems; Camarinha-Matos, L.M., Ferrada, F., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 231–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Tu, J.; Qiu, Y. A research on family flexible load scheduling based on improved non-dominated sorting genetic algorithm. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 71, 106541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Mo, D.; Kong, X.; Lu, Y.; Liang, Y.; Liang, Z. Intelligent optimal scheduling strategy of IES with considering the multiple flexible loads. Energy Rep. 2023, 9, 1983–1994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, L.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Y.; Luo, B.; Fan, L.; Liu, J.; Li, G. Multi-objective optimal scheduling of electricity consumption in smart building based on resident classification. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 98, 111085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Yang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, T. Classification of energy use patterns and multi-objective optimal scheduling of flexible loads in rural households. Energy Build. 2023, 283, 112811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z.; Peng, J.; Yin, R. Many-objective day-ahead optimal scheduling of residential flexible loads integrated with stochastic occupant behavior models. Appl. Energy 2023, 347, 121348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Makroum, R.; Khallaayoun, A.; Lghoul, R.; Mehta, K.; Zörner, W. Home Energy Management System Based on Genetic Algorithm for Load Scheduling: A Case Study Based on Real Life Consumption Data. Energies 2023, 16, 2698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, A.; Gomes, Á.; Antunes, C.H.; Cardoso, H. Domestic Load Scheduling Using Genetic Algorithms. In Applications of Evolutionary Computation; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Esparcia-Alcázar, A.I., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; Volume 7835, pp. 142–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patrício, J.T.; Silva, F.; Lopes, R.A.; Amaro, N.; Martins, J. Combining Time-Series Forecasting and Genetic Algorithm Based Optimization to Explore Energy Flexibility at Building-Level. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Engineering, Technology, and Innovation (ICE/ITMC), Funchal, Portugal, 24–28 June 2024; IEEE: Funchal, Portugal, 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urrutia, L.Z.; Schumann, M.; Febres, J. Optimization of electric demand response based on users’ preferences. Energy 2025, 324, 135893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- COMMUNITAS. Available online: https://communitas-project.eu/ (accessed on 12 November 2025).

- Berg, B.; Kunwar, N.; Guillante, P.; Vanage, S.; Mahmud, R.; Cetin, K.; Ardakani, A.J.; McCalley, J.; Wang, Y. Occupant-driven end use load models for demand response and flexibility service participation of residential grid-interactive buildings. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 96, 110406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Census Bureau. Housing and Urban Development and Census Bureau Expand Access to Detailed Information on Nation’s Housing. Available online: https://www.census.gov/newsroom/archives/2013-pr/cb13-04.html (accessed on 12 November 2025).

- Instituto Nacional de Estatística and Direção-Geral de Energia e Geologia. Inquérito ao Consumo de Energia no Sector Doméstico. 2020. Available online: https://www.dgeg.gov.pt/media/jvfgkejh/dgeg-aou-icesd-2020.pdf (accessed on 16 November 2025).

- Stratton, H.; Chen, Y.; Dunham, C.; Burke, T.; Yang, H.-C.; Ganeshalingam, M. Dishwashers in the Residential Sector: A Survey of Product Characteristics, Usage, and Consumer Preferences. Berkeley Lab; 2021. Available online: https://eta-publications.lbl.gov/sites/default/files/osg_lbnl_report_dishwashers_final_4.pdf (accessed on 16 November 2025).

- Lopes, R.A.; Silva, F.; Menezes-Barros, R.; Amaro, N.; de Carvalho, A.G.; Martins, J. Exploring energy flexibility from smart electrical water heaters to improve electrification benefits in residential buildings: Findings from real-world operation. Energy 2025, 316, 134381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevlian, R.; Rajagopal, R. A scaling law for short term load forecasting on varying levels of aggregation. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2018, 98, 350–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zippenfenig, P. Open-Meteo.com Weather API, version 1.4.0; Zenodo: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Hochreiter, S.; Schmidhuber, J. Long Short-Term Memory. Neural Comput. 1997, 9, 1735–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gers, F.A.; Schmidhuber, J.; Cummins, F. Learning to forget: Continual prediction with LSTM. In Proceedings of the 1999 Ninth International Conference on Artificial Neural Networks ICANN 99. (Conf. Publ. No. 470), Edinburgh, UK, 7–10 September 1999; Volume 2, pp. 850–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Si, X.; Hu, C.; Zhang, J. A Review of Recurrent Neural Networks: LSTM Cells and Network Architectures. Neural Comput. 2019, 31, 1235–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Gao, Y.; Li, Y.; Zheng, D.; Shan, D. Short-term household load forecasting based on Long- and Short-term Time-series network. Energy Rep. 2021, 7, 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.-H.; Gu, J.-C.; Yang, M.-T. A Simplified LSTM Neural Networks for One Day-Ahead Solar Power Forecasting. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 17174–17195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, J.H. Adaptation in Natural and Artificial Systems: An Introductory Analysis with Applications to Biology, Control, and Artificial Intelligence; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norman, D.A. The Design of Everyday Things; First Basic Paperback, [Nachdr.]; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Tewes, T.J.; Harcq, L.; Bockmühl, D.P. Use of Automatic Dishwashers and Their Programs in Europe with a Special Focus on Energy Consumption. Clean Technol. 2023, 5, 1067–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Washing Machines—European Commission. Available online: https://energy-efficient-products.ec.europa.eu/product-list/washing-machines_en (accessed on 12 November 2025).

- Richardson, I.; Thomson, M.; Infield, D.; Clifford, C. Domestic electricity use: A high-resolution energy demand model. Energy Build. 2010, 42, 1878–1887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.