Abstract

Large quantities of wastewater (OMW) are generated by the olive oil industry, requiring sustainable management to mitigate environmental impacts. The main goal of this work is to evaluate the possibility of using the homogeneous Fenton process as a pretreatment of OMW, as well as the iron (Fe (II) and Fe (III)) addition to improve the methane production through AD. The Fenton process achieved chemical oxygen demand (COD) and total phenolic compound (TPh) removals of 17–47% and 75–94%, respectively. However, methane production did not improve compared with untreated OMW, which yielded about 82 NmL CH4/ g CODi. The increase in H2S production from about 2 mL in raw OMW to more than 8 mL in treated OMW may justify the inhibition of AD. Supplementing AD with 2 mg/L of Fe (III) increased methane production by 65% and significantly reduced H2S due to FeS precipitation. The addition of 1 and 2 mg/L of Fe (II) also increased methane production by 82 and 59%, respectively, but no reduction in H2S was observed. Therefore, although the Fenton pretreatment effectively reduces recalcitrant organic matter, it does not necessarily enhance methane production. A balance must be achieved between improving OMW characteristics and minimizing adverse impacts on AD performance.

1. Introduction

Energy is fundamental for the well-being of society. Nevertheless, the excessive exploitation of fossil fuels is leading to negative environmental consequences [1]. According to the European Biogas Association (EBA), there is an urgent need to strengthen the European Union’s (EU) dependence on natural gas imports. In 2022, 62.5% of all fuels consumed in the EU were imported. Therefore, it is necessary to promote alternative and sustainable energy sources that minimize the impact on the environment and avoid the EU’s dependence on external suppliers [2].

Anaerobic Digestion (AD) is a biological process that provides organic waste valorization by converting it into biogas [3,4]. Biogas is a mixture of methane, carbon dioxide, and other minor gases, including hydrogen sulfide, ammonia, and oxygen. Methane is the main constituent of biogas and can effectively replace fossil fuels in heat and power generation. Production of biogas is regarded as a zero-waste technology, since the methane generated can be used as fuel and the digestate can be applied in agricultural applications. Biogas production in Europe in 2023 was 234 TWh with a tendency to grow in the coming decades [2,4,5].

Every year, the olive oil-producing industry faces challenges in managing the enormous amounts of waste generated during its operations. In addition to the value-added product, the olive oil, this activity also produces solid waste, olive pomace (OP), and olive mill wastewater (OMW). The OP has been valorized as fuel, for composting, and for extracting olive pomace oil [6]. For every ton of processed olives, between 0.2 and 1.6 m3 of OMW can be produced, depending on the extraction system applied (Traditional, Two-phase, and Three-phase systems) [7]. OMW, given its high negative impact on the environment when directly disposed of, represents a serious management problem, particularly for Mediterranean countries, which are significant producers of olive oil [8]. In these countries, severe droughts have worsened in recent years due to climate change, prompting interest in OMW valorization, where the treated waters can be reused in the process and for crop irrigation.

The high organic matter content present in OMW makes it highly interesting to apply the AD process for energy production and effluent treatment [9]. However, the high concentration of phenolic compounds characteristic of OMW and low biodegradability are a barrier to the application of conventional AD systems. Calabrò et al. [10] studied the effect of different concentrations of phenolic compounds on methane production and concluded that a concentration of 2.0 g/L inhibits the AD. Thus, to overcome the toxic characteristics of OMW and stabilize AD, several pretreatments have been studied to optimize AD efficiency [9,11,12,13]. Vaz et al. [11] investigated the integration of ozonation with AD, noting that ozone reacts with electron-rich compounds, breaking down aromatic structures into low-molecular-weight molecules. This results in the substantial removal of phenolic compounds while achieving only limited COD reduction. Similarly, Hakim et al. [9] employed resins to purify OMW by removing phenolic compounds, thereby enhancing AD performance. The Fenton reaction has been reported as a process that allows for high removals of organic matter, phenolic compounds, and consequently increases the biodegradability of OMW. Domingues et al. [14] combined coagulation and the Fenton process for the OMW treatment and managed to reduce toxicity, increase the biodegradability of the effluent above 0.4, and achieve 45% of chemical oxygen demand (COD) removal. Also, Amaral-Silva et al. [15] combined the same processes and reported an increase in biodegradability to 0.52, and COD and phenolic compound (TPh) removals of 90 and 92%, respectively. Reis et al.’s [16] results indicate an increase in biodegradability to 0.5 and removals of COD and phenolic compounds (TPh) of 81% and 97%, respectively. The addition of iron has also been identified in the literature to improve methane production in AD. Ruan et al. [17], Suanon et al. [18], and Kong et al. [19] reported increases in methane production by adding zero-valent iron (Fe0). The effect of iron on microorganisms and enzymatic activities in the various stages of AD, as well as its influence on minimizing H2S production by precipitating iron in the form of FeS, may justify its positive effect on increasing methane production [20].

Accordingly, the present work evaluates the feasibility of employing the Fenton process as a pretreatment step before AD. Due to the complexity of OMW, the Fenton process will be applied as a pretreatment to evaluate its effect on improving OMW characteristics on enhancing methane production during the AD process. While most of the literature on the Fenton process focuses on maximizing COD removal, this study aims to minimize COD reduction and maximize TPh removal to boost methane yield. Additionally, the effect of adding different sources and concentrations of iron directly in the AD process was evaluated to further enhance methane production. The assessment of the impact of pretreatments on H2S formation during AD represents the principal novelty of this work.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. OMW and Inoculum

Samples of OMW (OMW-1 and OMW-2) used were collected from a refined olive oil extraction industrial facility based in Portugal, as described by Vaz et al. [11]. The OMW-1 was collected in the campaign of 2023/2024, while the sample OMW-2 was collected in the campaign of 2024/2025. The inocula (I-1 and I-2) considered in the anaerobic tests were collected from anaerobic digesters of a municipal wastewater treatment plant in Portugal. Chemical oxygen demand (COD), total phosphorus (TP), total solids (TS), volatile solids (VS), total Kjeldahl nitrogen (TKN), and sulfur (S) content of the two inoculum samples studied are shown in Table S1 in Supplementary Information.

2.2. Experimental Design

For the study of the Fenton process, the response surface methodology (RSM) was explored according to a Central composite design (CCD). This approach was applied to identify the optimal conditions that maximize the removal of total phenolic compounds (TPh) while minimizing the reduction in the organic load (COD), with both responses denoted as and , respectively, aiming at their subsequent integration with AD. Two factors, Fe2+ dosage () and H2O2 dosage (), were selected as independent variables and varied at three levels, as summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Independent variables () and response variables (Yi) for the CCD.

The JMP Statistical DiscoveryTM software (JMP Pro 18) from SAS (Cary, NC, USA) was used to design the experiments (DoE) and experimental results analysis. The responses were modeled as a quadratic model (Equation (1)), which includes linear, quadratic, and interaction terms [21,22,23].

where the Yi are the dependent variables and and are the independent variables (according to Table 1). The terms , , are to the interaction and , the quadratic effects. is the independent constant, , are linear regression coefficients, , , the quadratic regression coefficients and , , the interaction regression coefficients [21,22,24].

2.3. Fenton Process

Fenton reactions were carried out with 1 L of effluent under continuous magnetic stirring. The intended dosage of Fe (II) sulfate heptahydrate (FeSO4·7H2O) was introduced, and the pH was adjusted to 3 using H2SO4 (5 M) solution. An initial sample of the effluent was collected after pH adjustment at the start of each reaction to account for any dilution caused by the pH adjustment. The reaction was started by the addition of hydrogen peroxide and carried out for 1 h, after which the pH was raised to approximately 10 using 5 M NaOH to precipitate the iron present. The treated effluent was then stored at 4 °C until analysis.

2.4. Biochemical Methane Potential

To evaluate the methane production of substrates, biochemical methane potential (BMP) assays were performed using 0.5 L reactors. The samples were prepared carefully by mixing the different substrate (s), the inoculum, and the nutrient solutions. The nutrient solutions were prepared according to the report by Angelidaki et al. [25]. The BMP assays were realized at neutral pH and mesophilic temperature (37 °C). To estimate the volume of biogas formed and accumulated in the headspace of the reactors, manometric measurements were realized. The pressure (P) inside each reactor was measured using a manometer sensor. To calculate the volume of biogas under STP conditions (Standard Temperature and Pressure), Equation (2) according to [1] was used,

whereis the headspace volume of the reactor (mL), and are Standard Temperature (273.15 K) and Pressure (1 atm). The P and T are the real pressure (atm) and temperature (K) inside the reactor. The gases, CH4, CO2, O2, and H2S were measured by a GAS DATA (GMF 406, Coventry, UK) equipment. In this study, methane production is presented in NmLCH4/g CODi [26]. The methane formed by the inoculum activity was deducted from the total methane generated by the substates.

2.5. Analytical Methods

The pH measurements were realized using a Crison-micropH 2002 equipment (Barcelona, Spain). COD was measured according to the Standard Method 5220D [27]. The biochemical oxygen demand (BOD5) was determined by measuring the negative pressure due to the oxygen consumption in a sealed system at 20 ± 0.1 °C over 5 days using OxiTop®-C (WTW, Ingolstadt, Germany). Biodegradability was calculated by the ratio between the BOD5/COD. Total phenolic compound content (TPh) was measured using the Folin–Ciocalteau method [28]. The absorbance was measured at 765 nm using a T60 UV/VIS (PG Instruments, Leicestershire, UK). Total organic carbon (TOC) was measured using a TOC analyzer (TOC-5000A, Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan), with an automatic sampler (ASI-5000A, Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan). Total Kjeldahl Nitrogen (TKN) was measured by sample digestion (DKL Fully Automatic Digestion Unit from VELP Scientifica, Usmate Velate, Italy). Total phosphorus (TP) was determined following US EPA Method 365.3, with an automatic digester (DKL Fully Automatic Digestion Unit, VELP Scientifica). The absorbance was measured at 650 nm using a T60 UV/VIS spectrophotometer (PG Instruments, Leicestershire, UK). Total solids (TS) were determined by drying samples at 105 °C. The volatile solids (VS) were measured by calcining the dried sample at 550 °C for 2 h, until constant weight was reached. To determine the lipids, liquid–liquid extraction was applied following the procedure described by Martins et al. [29]. Elemental analysis (NC Technologies, ECS 8040 CHNS-O, Milan, Italy) was used to measure the S, while the iron was analyzed by atomic absorption spectroscopy in a ContrAA 300 (Analytik Jena Gmbh, Jena, Germany).

2.6. Statistical Analysis

For developing the design of experiments (DoE) and the analysis of the experimentally obtained results, JMP Statistical DiscoveryTM software (JMP Pro 18) from SAS was applied. Statistical differences in the results were evaluated using a Tukey HSD test with a 95% confidence level.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. OMW Samples Characterization

The samples of OMW used were gathered from a refined olive oil extraction industry located in Portugal. The OMW-1 was collected in the campaign of 2023/2024, while the sample OMW-2 was collected in the campaign of 2024/2025, and the properties are summarized in Table 2. Both samples are characterized by high organic loads, with COD ranging from 29 to 35 gO2/L and BOD5 around 6 gO2/L. These values are higher than the limits for direct discharge into natural water bodies, according to Portuguese Decree-Law nº 236/98 (150 mgO2/L and 40 mgO2/L for COD and BOD5). The TPh content for both samples is approximately 2.5 g GAE/L, which is well above the stipulated for discharge (0.5 mg/L) and that reported by Calabrò et al. [10] for anaerobic digestion (AD) inhibition (2 g/L of TPh). The presence of these compounds, coupled with low biodegradability, restricts the applicability of biological processes, such as AD. The significant variability of effluents from olive oil production is also noted by analyzing Table 2. This variability makes it difficult to standardize effective processes for treating this complex effluent.

Table 2.

Properties of the OMW samples used in the present study.

3.2. Influence of Operating Conditions on Fenton Process Efficiency

In the Fenton process, there is decomposition of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) into hydroxyl radicals (•OH) in the presence of iron ions according to Equation (3) [14]. Hydroxyl radicals are non-selective and have a high oxidation potential (2.8 V) that allows the degradation of organic matter [14,30,31,32]. During the process, Fe3+ can also react with H2O2 and produce more Fe2+, according to Equation (4).

The effect of the independent variables, dosage of Fe2+ and H2O2 (and , respectively), on minimization of COD removal () and maximization of TPh removal () during the Fenton process was investigated using RSM based on a CCD. A DoE of 9 trials (performed in duplicate and central points in quadruplicate) with different combinations of the chosen factors was developed by JMP software (JMP Pro 18). The maximum values of and were selected according to Domingues et al. [14]. These authors obtained 30% of COD removal using 2 g/L of [Fe2+] and 4 g/L of [H2O2] at pH 3 for 1 h. Since the aim of this study is not to maximize COD removal but to minimize it, to preserve the substrate for subsequent AD feeding, these conditions were set as the maximum allowable. Given the iron limits for discharge stipulated in Decree-Law No. 236/98, 2 mg/L of [Fe2+] was stipulated as the minimum iron load for these tests. The dosage of Fe2+ varied between 0.002–2 g/L, and the H2O2 dosage varied between 0.5–4 g/L. The selected Fe2+ source was iron (II) sulfate heptahydrate (FeSO4·7H2O) according to Amor et al. [12], Tufaner [33], and Maamir et al. [34]. The operating time was set at 1 h, and the operating pH was set at 3 according to Domingues et al. [14]. In very acidic pH values (<2.5), Fe2+ is deactivated and (Fe(II)(H2O))2+ is produced. The iron complex ((Fe(II)(H2O))2+) reacts slowly with H2O2, thus decreasing the production of hydroxyl radicals [33]. At higher pH, Fe3+ can precipitate and form Fe(OH)3, which hinders the reaction between the ferric ion and H2O2 and, therefore, the regeneration of Fe2+ (Equation (4)). Furthermore, Fe(OH)3 catalyzes the decomposition of H2O2 into water and molecular oxygen, losing its oxidative capacity [34]. Several authors, such as Maamir et al. [34] and Mert et al. [35], reported pH 3 as ideal for the Fenton process.

The response variables ( and ) were obtained experimentally, and the respective standard deviations can be seen in Table 3. OMW-1 was used in these tests. As shown in Table 3, COD removals ranged from 17 to 47%, while TPh removals were between 75–94%. Indeed, TPh removal exceeded 75% for all conditions tested. These results can be justified by the presence of benzene rings in phenolic compounds, which are highly susceptible to oxidation [16]. These findings are according with other reports on the effectiveness of the Fenton process for phenol degradation [36].

Table 3.

Planning of experiments and experimental results for COD and TPh removal after 1 h of homogeneous Fenton at pH 3.

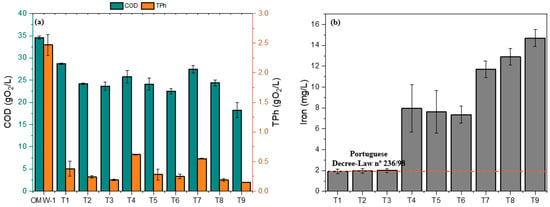

Figure 1a shows the COD and TPh values, while Figure 1b shows the dissolved iron after the Fenton process of OMW treatment for the different conditions under study. None of the conditions studied allowed reductions in COD and TPh for the effluent to be released into water sources (Portuguese Decree-Law nº 236/98). This outcome was expected, although the Fenton process can improve the effluent biodegradability due to its good capacity to remove COD and TPh. OMW is a very complex effluent that cannot be treated effectively by a single process [32]. Regarding the iron concentration in the treated effluent, only the tests with the minimum dosage of Fe2+ (0.002 g/L) meet the discharge limits for the effluent (Figure 1b).

Figure 1.

(a) COD and TPh after Fenton process; (b) iron dissolved in OMW treated after Fenton process. Note: OMW-1 was used in this study.

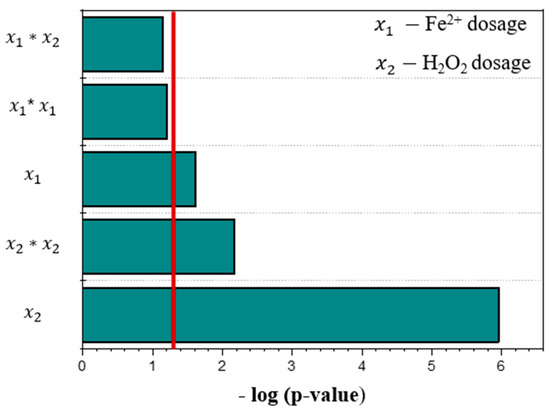

In general, from the results shown in Table 3 and Figure 1a, increasing the H2O2 dosage enhances TPh and COD removal efficiencies. However, maximizing COD and TPh removal is not the main objective of this work. In this study, COD removal should be minimized, maintaining the highest possible organic content, since AD benefits from substrates with a high organic content [9]. On the other hand, TPh removal should be maximized, since high concentrations of phenolic compounds are associated with higher toxicity for the methane-producing bacteria (MPB) involved in AD, thereby inhibiting the process [10,12]. Thus, given the study of independent variables at various levels simultaneously, it was evaluated which variables and effects have the greatest influence on minimizing COD removal () and maximization of TPh removal () through the Pareto diagram (Figure 2). Based on the statistical analysis, it was concluded that, for the interval under study for the independent variables, for a significance level of p-value < 0.05, the effect of H2O2 dosage () was identified as the independent variable that most influences the two dependent variables under study, followed by the quadratic effect (). In contrast, the quadratic effect of Fe2+ dosage () and interaction between dosage of Fe2+ and H2O2 demonstrated no statistical significance and were excluded from the model. Reis et al. [16] presented a similar study evaluating the influence of H2O2 and Fe2+ dosages, reaction time, and pH, finding that the linear effect of hydrogen peroxide dosage was the only independent variable with a significant impact on COD removal at a 95% confidence level.

Figure 2.

Pareto chart for the influence of independent variables on the COD (Y1) and TPh (Y2) removal in the Fenton process.

Results in Table 3 were used to fit polynomial models (Equation (1)) describing the removal of COD (%) and TPh (%) as a function of the normalized variables (Fe2+ and H2O2 dosages) (Table 1). The resulting regression models are provided in Equations (5) and (6).

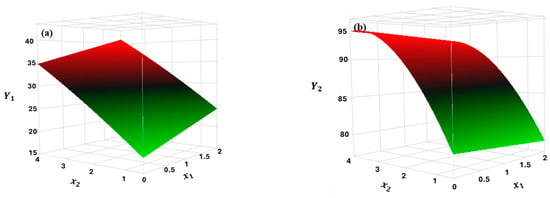

These regression model equations can be employed to predict the dependent variables under study. Experimental and predicted values obtained are presented in Table S2 and Figure S1 in the Supplementary Information. Figure 3a, b display the 3D response surface plots, which illustrate the effect of independent variables and their interaction on the variable responses. Both regression models predict that increasing the hydrogen peroxide dosage enhances COD and TPh removal. The same is not true for the Fe2+ dosage, which was less significant than the other factors considered (Figure 2), especially for TPh removal, where its coefficient is relatively low (Equation (6)). Consequently, an increase in iron load promotes COD removal, whereas a decrease favors TPh removal (Equations (5) and (6)).

Figure 3.

Response surface for (a) Y1 and (b) Y2 as a function of x1 and x2.

The optimal conditions within the CCD range were defined to minimize COD removal while maximizing TPh removal. The model predicted an H2O2 dosage of 2.5 g/L and an Fe2+ dosage of 0.002 g/L as the optimal operating conditions. These results were obtained based on the desirability function (Figure S2 in the Supplementary Information). Typically, both H2O2 and Fe2+ exhibit ideal dosages, meaning that the highest tested loads do not necessarily result in greater effluent depuration. Excessive H2O2 dosage increase the scavenging effect of •OH by H2O2, leading to a reduction in the degradation of organic pollutants (Equation (7)). A similar effect occurs with the ferrous iron dosage, which can react with the •OH to form Fe3+ (Equation (8)). The resulting Fe3+ promotes pollutant removal through coagulation and sedimentation (Equation (9)) at a considerably slower rate than the reaction in Equation (3) [14,34,37]. The Fe2+ dosage predicted by the model corresponds to the maximum limit for iron discharge into the environment. Therefore, its management is not expected to be a limiting factor in effluent disposal.

The regression models were validated by selecting a random set of conditions within the studied ranges of H2O2 and Fe2+ dosages. A dosage of 1.50 g/L of Fe2+ and 1.00 g/L of H2O2 was tested, and the results obtained are presented in Table S3 of the Supplementary Information.

3.3. Process Integration: Anaerobic Digestion After the Fenton Process

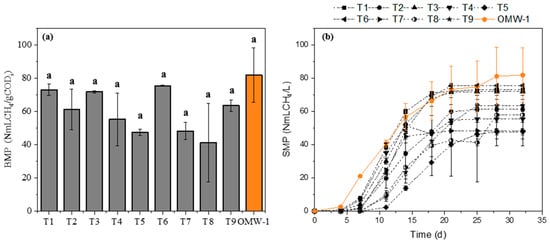

The effluent pretreated through different Fenton process conditions was subjected to BMP testing to quantify the maximum methane production of the substrate under anaerobic conditions. The tests were conducted with a substrate-to-inoculum ratio (SIR) equal to 1, as recommended by Vaz et al. [11] for the same effluent (OMW-1). Figure 4a,b show the BMP results after 32 days and the specific methane production (SMP), respectively, for the different pretreatment conditions tested.

Figure 4.

Volume of methane produced after pretreatment by Fenton process at different conditions in comparison with the OMW untreated: (a) after 32 days of AD; (b) over time. Note: Equal letters mean statistically equal results; OMW-1 was used in this study.

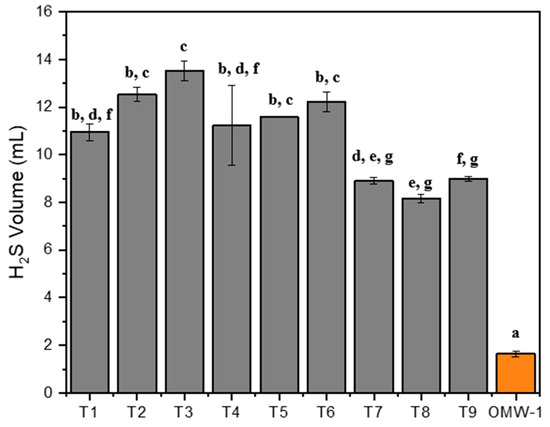

None of the applied pretreatments increased methane production compared to untreated OMW, which produced about 82 NmLCH4/gCODi. The Tuckey test confirmed that methane production obtained after 32 days for both untreated and treated effluent was not statistically different (Figure 4a). Analysis of Figure 4b indicates that pretreatment with the Fenton process extended the initial adaptation phase (lag phase) of the inoculum to the substrate. The profiles of methane production are commonly characterized by an initial lag phase, followed by a faster phase, and finally by a stabilization phase. The first phase represents the bacteria’s adaptation period present in the inoculum to the substrate. The duration of the lag phase is different for each substrate and different SIR [11,38]. Thus, although the treatment substantially removed phenolic compounds (with removals between 75% and 94%), which are known AD inhibitors, it may have formed other compounds that are also harmful to AD. The use of Fe (II) as an iron source and the addition of H2SO4 to acidify the effluent in the Fenton process treatment may have contributed to both the extended lag phase and the reduced methane production. Although OMW (OMW-1) and inoculum (I-1) used contain some sulfur (Table S1 and Table 2), the addition of both sulfur sources can lead to a high concentration of SO42− in the medium. Sulfate-reducing bacteria (SRB) and methane-producing bacteria (MPB) have survival conditions and use identical substrates, such as acetate and hydrogen, as electron donors [20,39]. Higher concentrations of SO42− may accelerate the growth of SRB, which can compete with MPB for the available substrates. Furthermore, SRB can have a higher affinity for substrates and grow faster than MPB, leading to the production of sulfides. At different pH levels of the medium, sulfides can exist as unionized H2S, ionized HS−, and S2− [39]. Amor et al. [12] reported that using sulfuric acid and the same iron source in the Fenton process pretreatment improved methane production in AD. However, Maamir et al. [34] also employed the same reagents, concluding that accumulated methane volumes decreased when OMW was pretreated by Fenton compared to untreated OMW. H2S production during AD was evaluated for each pretreatment condition studied. Figure 5 shows the H2S volume produced in the AD under the different treatment conditions.

Figure 5.

Volume of H2S produced in different conditions of the Fenton process as pretreatment in AD. Note: Equal letters mean statistically equal results; OMW-1 was used in this study.

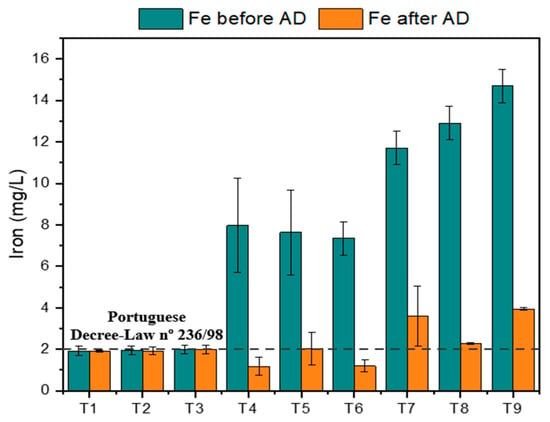

While untreated OMW, without the addition of sulfur sources, produced about 1.6 mL of H2S, the treated OMW produced over 8 mL of H2S during AD. A higher addition of iron sulfate (2 g/L) did not lead to increased H2S production compared with the lower concentrations tested (0.002 and 1 g/L). Although the Tuckey test indicated no statistically significant differences between different iron loads, other studies have reported contrasting results. This aspect can be explained by the presence of dissolved iron in the OMW treated by the Fenton process. Figure 6 shows the iron concentration before and after AD. It should be noted that the iron measurement after AD was performed after centrifugation of the digestate, with the measurement being made only in the liquid portion. According to the literature, iron can also mitigate H2S emissions through precipitation of iron sulfide (FeS), Equation (10) [20].

Figure 6.

Iron concentration before and after AD. Note: OMW-1 was used in this study.

It was verified that the T8 test, with an elevated dissolved iron concentration, produced lower H2S volumes (Figure 5 and Figure 6). Reducing H2S emissions due to iron precipitation can markedly improve both the quantity and quality of biogas [20]. Suanon et al. [18] and Kong et al. [19] reported methane yield increases exceeding 40% with the addition of Fe0 in AD. In the present study, H2S production was considerable, exceeding 8 mL compared to less than 2 mL for untreated effluent, without any corresponding increase in methane production. Although some dissolved iron present in the treated OMW may have precipitated due to the rise in pH around 6.5–7.5 for the normal course of AD, other iron may have been precipitated as reported in the form of FeS (Equation (10)). However, other authors Baek et al. [40] suggest that the precipitation of FeS on the cell surface of methanogens and the adsorption of Fe (III) to proteins involved in energy metabolism may be inhibitors of methanogenesis.

3.4. Effect of Fe (II) and Fe (III) on Anaerobic Digestion

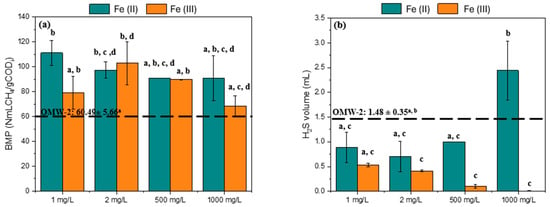

To assess the effect of iron on AD process, the addition of two iron sources, Fe (III) chloride hexahydrate (FeCl3·6H2O) and Fe (II) sulfate heptahydrate (FeSO4·7H2O), with different loads (1, 2, 500, and 1000 mg/L), was studied. The objective of applying lower iron loads (1 and 2 mg/L) is to evaluate whether there is any enhancement of AD with iron loads that are in accordance with the limits stipulated by Portuguese Decree-Law No. 236/98 for the discharge of effluents into watercourses. The effect of higher loads (500 and 1000 mg/L) on enhancing the AD process was studied to evaluate their toxic or beneficial character according to the information in the literature. Wang et al. [41] reported that a low Fe (III) content (<750 mg/L) promotes anaerobic digestion in the waste-activated sludge, while a continuous increase in Fe (III) inhibits methane production. It should be noted that the effluent and inoculum used in this study differ from those in the previous study. In this case, the OMW-2 effluent (without any prior treatment) and I-2 were employed (Table S1 and Table 2). Figure 7a,b show the methane production and H2S volumes, respectively, for the two iron sources studied under different dosages.

Figure 7.

(a) BMP and (b) H2S volume production for different iron sources and dosages in the study. Note: Equal letters mean statistically equal results; OMW-2 was used in this study.

Methane production for OMW-2 was about 61 NmLCH4/g CODi, 26% lower than OMW-1. Even so, the release of H2S from both raw effluents was the same, approximately 1.6 and 1.5 L of H2S for OMW-1 and OMW-2, respectively. The addition of 1 and 2 mg/L of Fe (II) enhanced methane production compared to untreated OMW-2, achieving BMP values of 111 and 97 NmLCH4/gCODi, respectively. Regarding Fe (III), only the 2 mg/L load increased methane production to 103 NmLCH4/gCODi comparing with the raw effluent. The literature has reported that iron supplementation can enhance methane production in AD by stimulating the activity of acidogenic bacteria (second stage of AD). Furthermore, the addition of Fe (III) resulted in reduced H2S production compared to raw OMW-2. This reduction can be attributed, as already mentioned, to the precipitation of iron as FeS, Equation (11). Under anaerobic conditions, Fe3+ can be reduced to Fe2+, also occurring the reaction in Equation (12) [40]. When Fe (II) was added, the H2S production results were less consistent, as the introduction of iron also introduced sulfate using Fe (II) sulfate heptahydrate (FeSO4·7H2O). The addition of 1000 mg/L of Fe2+ increased H2S production by approximately 65% compared to raw OMW-2. However, this increase was not statistically significant (Figure 7b).

Methanogens are among the microbial groups most susceptible to H2S toxicity. Therefore, proper control of sulfide concentrations in anaerobic digesters through the addition of Fe (II) or Fe (III) can indirectly enhance methanogenic activity, especially when treating sulfur-rich substrates [20]. Nonetheless, selecting an appropriate iron source and maintaining an optimal iron concentration are essential [40].

The presence of iron in effluent treated by AD can be advantageous for subsequent processes that use iron as a catalyst. Sulfate radical-based advanced oxidation processes, such as persulfate and peroxymonosulfate, can be activated by iron and thus may represent a viable option for post-AD treatment [32]. At an industrial scale, an H2S monitoring system could be employed to determine the appropriate iron dosage in the Fenton process, preventing inhibition of the AD process.

4. Conclusions

This study evaluates the potential of the homogeneous Fenton process as a pretreatment and the effect of iron addition on improving OMW properties and enhancing methane production through AD.

In the first phase, based on the Central Composite design (CCD), the response surface methodology (RSM) was used to assess the impact of H2O2 and Fe2+ dosage on minimizing COD removal and maximizing TPh removal. COD and TPh removal ranged from 17 to 47% and 75 to 94%, respectively. Nevertheless, due to the high complexity of the effluent under study, the treatment by the Fenton process did not enable compliance with the discharge limits stipulated by Portuguese Decree-Law nº 236/98. The effluent treated by the Fenton process was subsequently subjected to BMP tests to assess the maximum methane production under different treatment conditions. None of the Fenton pretreatment conditions improved methane yield, despite the substantial removal of phenolic compounds, known inhibitors of AD. The observed increases in H2S production, from 2 mL in raw OMW to over 8 mL in treated OMW, may justify the inhibition of the AD process. The use of Fe (II) sulfate heptahydrate (FeSO4·7H2O) as an iron source and the addition of a sulfuric acid solution for pH adjustment may explain the increase in H2S production. Nevertheless, the dissolved iron in the treated effluent proved to be a viable way to minimize H2S production by precipitating iron in the form of FeS.

The effect of two iron sources, Fe2+ and Fe3+, at different loads was also evaluated. The addition of 2 mg/L of Fe (III) improved methane production by 65% while markedly reducing H2S production. The addition of 1 and 2 mg/L of Fe (II) increased methane production by 82% and 59%, respectively. However, no reduction in H2S volume was observed, as Fe2+ was supplied in the form of Fe (II) sulfate heptahydrate (FeSO4·7H2O).

In conclusion, although pretreatment can convert the recalcitrant organic matter present in OMW into simpler and more biodegradable compounds, this does not necessarily translate into an effective improvement in the AD process, namely in methane production. Therefore, a balance must be established between improving the physicochemical characteristics of OMW and minimizing the potential adverse effects of pretreatment on biological systems.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/en19010051/s1, Table S1: Physical and chemical properties of inoculum samples (I-1 and I-2); Table S2: Experimental and model-predicted values for COD and TPh removal after Fenton’s process; Figure S1: Comparison between experimental values and those predicted by regression models for: (a) COD removal (); (b) TPh removal (); Table S3: Experimental and predicted values for model validation; Figure S2: Optimal conditions for minimizing and maximizing and desirability function (obtained by JMP software).

Author Contributions

T.V.: Writing—original draft, Conceptualization, Investigation, Visualization, Methodology, Funding acquisition. S.D.: Investigation, Methodology, Conceptualization. R.C.M.: Methodology, Resources, Conceptualization, Writing—review & editing, Visualization, Funding acquisition, Supervision. J.G.: Methodology, Resources, Conceptualization, Writing—review & editing, Visualization, Supervision, Funding acquisition, Supervision. M.J.Q.: Methodology, Resources, Conceptualization, Writing—review & editing, Visualization, Funding acquisition, Supervision. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors gratefully acknowledge FCT (Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia, Portugal) for the PhD Grant (2022.14237.BD and https://doi.org/10.54499/2022.14237.BD) and the financial support (CEECIND/01207/2018 and DOI: 10.54499/CEECIND/01207/2018/CP1585/CT0003). Thanks are due to FCT/MCTES for the financial support to CERES (https://doi.org/10.54499/UID/00102/2025 and https://doi.org/10.54499/UID/PRR/00102/2025).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Nomenclature

The following nomenclature is used in this manuscript:

| BMP | Biochemical methane potential (NmLCH4/gCODi) |

| BOD5 | Biochemical oxygen demand (gO2/L) |

| COD | Chemical Oxygen Demand (gO2/L) |

| TOC | Total organic carbon (gC/L) |

| TKN | Total Kjeldahl Nitrogen (gN/L) |

| TPh | Total phenolic compounds (g/L) |

| TP | Total phosphorus (mgP/L) |

| TS | Total solids (g/L) |

| VS | Volatile solids (g/L) |

| Acronyms | |

| AD | Anaerobic Digestion |

| CCD | Central Composite Design |

| DoE | Design of experiments |

| EBA | European Biogas Association |

| EU | European Union |

| MPB | Methane-producing bacteria |

| OMW | Olive mill wastewater |

| OP | Olive Pomace |

| RSM | Response surface methodology |

| SIR | Substrate-to-inoculum ratio |

| SRB | Sulfate-reducing bacteria |

References

- Almeida, P.V.; Rodrigues, R.P.; Teixeira, L.M.; Santos, A.F.; Martins, R.C.; Quina, M.J. Bioenergy production through mono and co-digestion of tomato residues. Energies 2021, 14, 5563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EBA (European Biogas Association). Available online: https://www.europeanbiogas.eu/ (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Gómez-Camacho, C.E.; Pirone, R.; Ruggeri, B. Is the Anaerobic Digestion (AD) sustainable from the energy point of view? Energy Convers. Manag. 2021, 231, 113857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wongarmat, W.; Sittijunda, S.; Imai, T.; Reungsang, A. Co-digestion of filter cake, biogas effluent, and anaerobic sludge for hydrogen and methane production: Optimizing energy recovery through two-stage anaerobic digestion. Carbon Resour. Convers. 2025, 8, 100248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archana, K.; Visckram, A.S.; Kumar, P.S.; Manikandan, S.; Saravanan, A.; Natrayan, L. A review on recent technological breakthroughs in anaerobic digestion of organic biowaste for biogas generation: Challenges towards sustainable development goals. Fuel 2024, 358, 130298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parascanu, M.M.; Sánchez, P.; Soreanu, G.; Valverde, J.L.; Sanchez-Silva, L. Environmental assessment of olive pomace valorization through two different thermochemical processes for energy production. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 186, 771–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medouni-Haroune, L.; Zaidi, F.; Medouni-Adrar, S.; Kecha, M. Olive pomace: From an olive mill waste to a resource, an overview of the new treatments. J. Crit. Rev. 2018, 5, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioannou-Ttofa, L.; Michael-Kordatou, I.; Fattas, S.C.; Eusebio, A.; Ribeiro, B.; Rusan, M.; Americano, A.R.B.; Zuraiqi, S.; Waismand, M.; Linder, C.; et al. Treatment efficiency and economic feasibility of biological oxidation, membrane filtration and separation processes, and advanced oxidation for the purification and valorization of olive mill wastewater. Water Res. 2017, 114, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakim, C.; Neffa, M.; Essadek, A.; Battimelli, A.; Escudie, R.; García-Bernet, D.; Harmand, J.; Carrère, H. Combined Continuous Resin Adsorption and Anaerobic Digestion of Olive Mill Wastewater for Polyphenol and Energy Recovery. Energies 2025, 18, 3226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabrò, P.S.; Fòlino, A.; Tamburino, V.; Zappia, G.; Zema, D.A. Increasing the tolerance to polyphenols of the anaerobic digestion of olive wastewater through microbial adaptation. Biosyst. Eng. 2018, 172, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaz, T.; Domingues, S.; Martins, R.C.; Gomes, J.; Quina, M.J. Ozonation to enhance methane production in anaerobic digestion of olive oil industry wastewater. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 117888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amor, C.; Lucas, M.S.; Garcia, J.; Dominguez, J.R.; De Heredia, J.B.; Peres, J.A. Combined treatment of olive mill wastewater by Fenton’s reagent and anaerobic biological process. J. Environ. Sci. Health Part A 2015, 50, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Bawab, A.F.; Abu-Dalo, M.A.; Kanaan, H.; Al-Rawashdeh, N.; Odeh, F. Removal of phenolic compounds from olive mill wastewater (OMW) by tailoring the surface of activated carbon under acidic and basic conditions. Water Sci. Technol. 2025, 91, 567–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingues, E.; Fernandes, E.; Gomes, J.; Castro-Silva, S.; Martins, R.C. Olive oil extraction industry wastewater treatment by coagulation and Fenton’s process. J. Water Process Eng. 2021, 39, 101818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaral-Silva, N.; Martins, R.C.; Castro-Silva, S.; Quinta-Ferreira, R.M. Integration of traditional systems and advanced oxidation process technologies for the industrial treatment of olive mill wastewaters. Environ. Technol. 2016, 37, 2524–2535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, P.M.; Martins, P.J.; Martins, R.C.; Gando-Ferreira, L.M.; Quinta-Ferreira, R.M. Integrating Fenton’s process and ion exchange for olive mill wastewater treatment and iron recovery. Environ. Technol. 2018, 39, 308–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, R.; Cao, J.; Li, C.; Zheng, D.; Luo, J. The influence of micro-oxygen addition on desulfurization performance and microbial communities during waste-activated sludge digestion in a rusty scrap iron-loaded anaerobic digester. Energies 2017, 10, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suanon, F.; Sun, Q.; Li, M.; Cai, X.; Zhang, Y.; Yan, Y.; Yu, C.P. Application of nanoscale zero valent iron and iron powder during sludge anaerobic digestion: Impact on methane yield and pharmaceutical and personal care products degradation. J. Hazard. Mater. 2017, 321, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, X.; Yu, S.; Xu, S.; Fang, W.; Liu, J.; Li, H. Effect of Fe0 addition on volatile fatty acids evolution on anaerobic digestion at high organic loading rates. Waste Manag. 2018, 71, 719–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, J.; Hao, X.; van Loosdrecht, M.C.; Li, J. Feasibility analysis of anaerobic digestion of excess sludge enhanced by iron: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 89, 16–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaz, T.; Quina, M.M.; Martins, R.C.; Gomes, J. Activation of Persulfate by temperature and iron filings for the treatment of synthetic olive mill wastewater: Optimization of conditions with a box–Behnken design. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 359, 130605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zheng, H. Optimization for decolorization of azo dye acid green 20 by ultrasound and H2O2 using response surface methodology. J. Hazard. Mater. 2009, 172, 1388–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, M.; Saraf, S.; Pradhan, M.; Patel, R.J.; Singhvi, G.; Alexander, A. Design and optimization of curcumin loaded nano lipid carrier system using Box-Behnken design. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 141, 111919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Görmez, F.; Görmez, Ö.; Yabalak, E.; Gözmen, B. Application of the central composite design to mineralization of olive mill wastewater by the electro/FeII/persulfate oxidation method. SN Appl. Sci. 2020, 2, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelidaki, I.; Alves, M.; Bolzonella, D.; Borzacconi, L.; Campos, J.L.; Guwy, A.J.; Kalyuzhnyi, S.; Jenicek, P.; Van Lier, J.B. Defining the biomethane potential (BMP) of solid organic wastes and energy crops: A proposed protocol for batch assays. Water Sci. Technol. 2009, 59, 927–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoufi, S.; Aloui, F.; Sayadi, S. Treatment of olive oil mill wastewater by combined process electro-Fenton reaction and anaerobic digestion. Water Res. 2006, 40, 2007–2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baird, R.B.; Eaton, A.D.; Rice, E.W. Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater, 23rd ed.; American Public Health Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Lamuela-Raventós, R.M. Folin–Ciocalteu method for the measurement of total phenolic content and antioxidant capacity. In Measurement of Antioxidant Activity & Capacity: Recent Trends and Applications; Apak, R., Capanoglu, E., Shahidi, F., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Martins, D.; Martins, R.C.; Braga, M.E.M. Biocompounds recovery from olive mill wastewater by liquid-liquid extraction and integration with Fenton’s process for water reuse. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2021, 28, 29521–29534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manos, D.; Miserli, K.; Konstantinou, I. Perovskite and spinel catalysts for sulfate radical-based advanced oxidation of organic pollutants in water and wastewater systems. Catalysts 2020, 10, 1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingues, E.; Silva, M.J.; Vaz, T.; Gomes, J.; Martins, R.C. Sulfate radical based advanced oxidation processes for agro-industrial effluents treatment: A comparative review with Fenton’s peroxidation. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 832, 155029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaz, T.; Quina, M.M.; Martins, R.C.; Gomes, J. Olive mill wastewater treatment strategies to obtain quality water for irrigation: A review. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 931, 172676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tufaner, F. Evaluation of COD and color removals of effluents from UASB reactor treating olive oil mill wastewater by Fenton process. Sep. Sci. Technol. 2020, 55, 3455–3466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maamir, W.; Ouahabi, Y.; Poncin, S.; Li, H.Z.; Bensadok, K. Effect of Fenton pretreatment on anaerobic digestion of olive mill wastewater and olive mill solid waste in mesophilic conditions. Int. J. Green Energy 2017, 14, 555–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mert, B.K.; Yonar, T.; Kiliç, M.Y.; Kestioğlu, K. Pre-treatment studies on olive oil mill effluent using physicochemical, Fenton and Fenton-like oxidations processes. J. Hazard. Mater. 2010, 174, 122–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, L.; Wang, J.; Dong, J.; Liu, H.; Sun, X. Treatment of coking wastewater by an advanced Fenton oxidation process using iron powder and hydrogen peroxide. Chemosphere 2012, 86, 409–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kallel, M.; Belaid, C.; Boussahel, R.; Ksibi, M.; Montiel, A.; Elleuch, B. Olive mill wastewater degradation by Fenton oxidation with zero-valent iron and hydrogen peroxide. J. Hazard. Mater. 2009, 163, 550–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pellera, F.M.; Gidarakos, E. Effect of substrate to inoculum ratio and inoculum type on the biochemical methane potential of solid agroindustrial waste. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2016, 4, 3217–3229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Cheng, H.; Chen, F.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, X.; Huang, C.; Chen, C.; Liu, W.; Ding, C.; Li, Z.; et al. Enhanced methane production by alleviating sulfide inhibition with a microbial electrolysis coupled anaerobic digestion reactor. Environ. Int. 2020, 136, 105503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baek, G.; Kim, J.; Lee, C. A review of the effects of iron compounds on methanogenesis in anaerobic environments. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2019, 113, 109282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Gong, Y.; Sun, C.; Wang, Z.; Sun, Y.; Yu, Q.; Zhang, Y. New insights into inhibition of high Fe (III) content on anaerobic digestion of waste-activated sludge. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 916, 170147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.