1. Introduction

Transport plays a significant role in global economic growth. However, the transport sector accounts for approximately 23% of global CO

2 emissions [

1,

2]. More than three-quarters of the transport sector’s total emissions come from road transport, driven by the dominant use of internal combustion engines (ICEs) in vehicles. To reduce or eliminate these emissions, it is necessary to develop vehicles powered by near-zero emissions. Hence, the transition from internal combustion engines (ICEs) to electric vehicles (EVs) is becoming increasingly visible [

3,

4,

5]. However, this transition has not been as smooth as expected, because at present no single energy source matches fossil fuels in terms of both energy and power density [

4]. Therefore, hybridisation appears to be a necessity. Hybrid electric vehicles (HEVs) use both a conventional internal combustion engine and an electric motor drive system powered by a battery [

6,

7,

8]. HEVs appear to be the most economically viable solution to date, and likely in the coming decades. The overall objective of HEV development is to reduce fuel consumption and emissions while maintaining the required power demand [

5].

Such vehicles allow for a reduction in harmful emissions by shifting the operating range of the internal combustion engine to avoid low-efficiency, high-emission conditions—typically idle and low load.

Different levels of hybridisation exist—Mild Hybrid Electric Vehicle (MHEV), Full Hybrid (HEV), and Plug-in Hybrid Electric Vehicle (PHEV)—and the main distinguishing factors are the electric system’s power and the battery’s capacity. Higher electric power enables the vehicle to operate more frequently in electric mode and to recover more braking energy, thereby increasing its energy-saving potential [

9]. The aim of MHEVs is to support the combustion engine during take-off and to recover energy. HEVs and PHEVs share many similarities but also have key differences. These differences primarily relate to the degree of cooperation between the internal combustion engine and the electric motor, as well as the role of the traction battery. HEVs focus on improving the efficiency of the combustion system and energy recuperation, while PHEVs expand functionality by enabling fully electric driving, though this requires user engagement in regular charging, especially in urban traffic [

10,

11]. PHEVs combine the benefits of electric driving in daily use with the flexibility of conventional propulsion during longer journeys.

Internal combustion engines are very complex mechanical–chemical systems where various processes of oil degradation happen at the same time (e.g., oxidation, acidification, soot build-up), along with interactions involving other machine parts (e.g., corrosion, wear, deposit formation) [

12]. The operational qualities of engine oils greatly influence the efficiency of internal combustion engines and largely determine their reliability, service life, and environmental impact [

13].

Hybrid vehicles impose different operating cycles on the internal combustion engine compared with conventional powertrains. A characteristic feature of HEVs is the ability to switch off the combustion engine whenever the electrical system provides sufficient power to propel the vehicle. As a result, the engine undergoes repeated start–stop cycles, its operating time is reduced, and the duration of low-temperature operation increases significantly [

8,

9,

14,

15].

Lower engine operating temperatures are especially noticeable during short trips in battery-sustaining mode, urban driving, trips at the end of the electric range, low ambient temperatures, or a combination of these factors. These conditions can potentially cause the build-up of fuel and water in the oil sump. While high temperatures cause fuel and water to evaporate from the lubricant, this process is less effective at low temperatures. Such oil contamination not only affects the performance of additives but also reduces the lifespan, resulting in increased friction and wear of mechanical components [

8].

Vehicle hybridisation, therefore, introduces new challenges for the development of lubricants. New fuel components and combustion by-products—absent in earlier engine generations—may influence oil degradation and increase wear on engine contact surfaces and bearing elements [

16].

Research studies [

12,

17] show that hybrid vehicles accumulate significantly more fuel in their engine oil than conventional vehicles. When combined with the reduced evaporation resulting from lower lubricant temperatures in hybrids, this creates a serious challenge for ensuring effective engine protection in HEVs [

18].

Oil dilution can occur due to condensation during the engine warm-up phase or through the impingement of fuel droplets onto the cylinder wall, after which the fuel flows downward through the ring–liner gap to the oil sump [

19]. Fuel dilution adversely affects engine component wear, oil lubricity, exhaust emissions, and oil change frequency [

20]. The level and rate of accumulation depend on engine operating conditions and vehicle usage patterns. Oil dilution is generally considered excessive when it exceeds 3–5%. This amount depends not only on the type of fuel and engine design, but also on user behaviour. Excessive dilution levels may be easily reached under certain driving styles (e.g., many short trips at low temperatures). Tests conducted by [

21] showed that over a distance of 4.8 km the maximum oil temperature reached 90 °C in summer and 30 °C in winter, while over 2.4 km it reached only 75 °C. Fuel dilution increased by 3–5% in summer and 8–11% in winter, as the oil did not become sufficiently warm to evaporate volatile components. These threshold values apply primarily to gasoline engines, while diesel engines may tolerate higher dilution levels due to different combustion characteristics. In practical diagnostics, the resulting decrease in oil viscosity is often a more informative indicator of fuel-related degradation than the absolute percentage of fuel in the lubricant. An empirical model developed by [

20] predicts that with a warmed engine the dilution level should not exceed 2%, and similar conclusions were obtained by [

22,

23]. High fuel levels in the oil may also occur in modern vehicles equipped with start–stop systems [

24].

The presence of fuel in engine oil may lead to several issues. According to various authors, these include: an increase in oil level in the sump, changes in lubricant viscosity, deposit formation, effects on friction, low-speed pre-ignition, and removal of the cylinder-liner oil film [

24]. In gasoline engines, fuel dilution decreases oil viscosity, affecting fuel consumption. This effect is more pronounced at low temperatures (around 50 °C). According to [

24] for an SAE 5W-30 oil with 10% fuel content, the kinematic viscosity at 40 °C may decrease from 55 cSt to 35.5 cSt, whereas at higher temperatures the differences diminish. This results from the lower evaporation of fuel at low temperatures combined with the high viscosity of the oil itself. At higher temperatures, fuel evaporation increases and oil viscosity naturally decreases, causing the viscosity difference between oil and fuel to narrow. However, one must also consider the issue of fuel or fuel additives interfering with lubricant additives (such as friction modifiers or anti-wear additives) [

25,

26,

27].

In addition to the conventional viscosity grades used in hybrid vehicles, such as 5W30 or 0W20, ultralow-viscosity oils such as 0W16 or even 0W8 are also encountered. The use of such low-viscosity lubricants aims to protect engines that frequently operate without reaching full operating temperature (e.g., on short trips). Additional fuel dilution may therefore have serious consequences with a direct impact on engine condition and failure risk. Another issue associated with hybrid operation is the recommendation of low-viscosity engine oils, such as 0W16 or even 0W8, to protect engines operating over short distances before reaching full temperature [

28]. When such low-viscosity lubricants are used, fuel dilution may have severe consequences directly affecting engine integrity and failure risk [

18].

The examples above illustrate the complexity of the influence of vehicle hybridisation on engine oil. Hence, there is a need for extensive research to understand the mechanisms driving accelerated wear and degradation in hybrid powertrains. Therefore, the objective of this study is to evaluate fuel-induced dilution in ten hybrid vehicles by integrating viscosity measurements, FTIR spectral analysis, and paper chromatography tests. The research aims to identify characteristic degradation patterns and quantify the correspondence between viscosity loss and infrared spectral shifts, thereby advancing the understanding of lubricant deterioration mechanisms unique to hybrid combustion systems.

3. Methods

The variations in kinematic viscosity at 40 °C and 100 °C were determined using an SVM Stabinger Viscometer model 3001 (Anton Paar GmbH, Graz, Austria), operated in accordance with the ASTM D7042-21A standard [

29]. The instrument integrates a rotational Stabinger system with a density measurement cell, enabling simultaneous determination of dynamic viscosity, kinematic viscosity, and density under strictly controlled thermal conditions. The obtained kinematic viscosity values for used oils were compared with the reference viscosities of the corresponding fresh oils of identical specification. This procedure made it possible to determine both the direction and the magnitude of viscosity changes, allowing for the assessment of fuel-related dilution effects and mechanical shear of polymeric additives.

The chemical transformation processes occurring in the used oils were examined using Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy with a Thermo Nicolet iS5 spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), following ASTM E2412-23A [

30]. A ZnSe transmission cell with an optical path length of 0.1 mm was employed, and differential spectra were generated by subtracting the spectrum of each fresh oil from that of the corresponding used sample. The FTIR interpretation focused on diagnostically relevant regions directly associated with degradation pathways in gasoline engine oils. Oxidation was evaluated in the 1800–1670 cm

−1 region containing carbonyl absorptions (C=O). Nitration was assessed from the band near 1630 cm

−1 attributed to –O–NO

2 functional groups. Sulfation processes were interpreted in the 1300–1000 cm

−1 interval, which includes S–O and sulfonyl vibrations. The degradation of extreme-pressure additives, particularly zinc dialkyldithiophosphates, was examined through negative features in the 1000–900 cm

−1 region. Additional information on polar contamination and hydroxyl-bearing oxidation products was obtained from the broad absorptions between 3600–3100 cm

−1 and the neighbouring 3000–3100 cm

−1 region. Particular emphasis was placed on the spectral interval associated with fuel dilution, where gasoline hydrocarbons exhibit characteristic out-of-plane C–H bending vibrations. The most indicative signal occurs near 800 cm

−1 (typically 810–780 cm

−1), and increases in this area were used qualitatively to identify the presence of unburned fuel in the lubricant. Quantitative indices for oxidation, nitration, sulfation and antioxidant depletion were calculated using the baseline definitions specified in ASTM E2412, and all absorbance values were normalised to the 0.1 mm optical path to ensure full comparability of the spectra.

Paper chromatography was applied as a complementary diagnostic technique to visualise dispersion quality, contamination patterns and potential fuel-related effects in the oils. Two types of filter media were used: (1) paper developed using original laboratory formulations, optimised for enhanced separation of central and peripheral zones, and (2) professional chromatographic paper supplied by MCU (Motor Check Up, Birstein, Germany), designed specifically for engine oil spot testing. The in-house papers were selected for their increased hydrophilicity and improved migration uniformity, which enable clearer differentiation between the dark central deposit zone, the diffusion ring and the outer oxidative halo. The MCU paper, characterised by a more controlled capillary structure and higher reproducibility, served as the reference material to ensure comparability between samples. A fixed droplet volume of each oil was deposited onto the paper surface and allowed to develop under controlled ambient conditions until migration ceased. The resulting chromatograms were evaluated qualitatively, focusing on ring structure, distribution of insolubles, halo intensity and overall spot morphology. In hybrid engines, the presence of volatile fuel components typically influences the relative expansion of the diffusion zone and alters the sharpness of the central deposit area; thus, chromatographic patterns provided additional insight into the degree of dilution and the general stability of the lubricant.

4. Results and Discussion

Table 4 summarises the kinematic viscosity values of both fresh and used oils for all ten samples included in the study. The fresh oils represent a mixture of low-viscosity grades commonly used in hybrid powertrains, including 0W16, 0W20 and 5W30 formulations, which is reflected in their relatively broad range of initial viscosity values at 40 °C and 100 °C. Despite these differences in nominal grade, all oils exhibited viscosity levels consistent with their declared SAE classification. After operation, each sample showed a measurable decrease in viscosity at both reference temperatures. The magnitude of the reduction varied between oils but was substantial in nearly all cases, typically amounting to a loss of several units in kinematic viscosity at 40 °C and a smaller yet clear decline at 100 °C. These changes were sufficiently large to influence the calculated viscosity index, which increased slightly in most samples due to the disproportionately greater reduction at lower temperature—a characteristic effect of fuel dilution. The consistent downward trend in viscosity across all analysed oils indicates significant alteration of the rheological properties during service. Given the hybrid-specific operating conditions described earlier—frequent engine restarts, short combustion intervals and limited oil temperature stabilisation—the observed reductions are compatible with dilution by unburned fuel, which lowers viscosity preferentially at 40 °C. This behaviour provides the first quantitative indication that fuel ingress may have played a dominant role in the degradation of these lubricants.

Table 5 presents the percentage changes in kinematic viscosity observed for all used oil samples. Across the entire dataset, each case exhibited a clear decrease in viscosity, confirming the systematic impact of hybrid-related operating conditions on lubricant stability. The reductions at 40 °C range from −6.5% to −35.3%, while at 100 °C the declines vary between −3.0% and −26.9%. These values indicate substantial physicochemical alteration of the oils, with the magnitude of the viscosity loss strongly influenced by both the engine characteristics and the exploitation profile.

The smallest viscosity decrease was recorded for sample 6, originating from the Audi A4 Avant equipped with a mild hybrid powertrain (engine code DMSA). In this configuration, the combustion engine operates more continuously than in full hybrid systems, and the electric subsystem mainly supports transient load changes rather than enabling prolonged engine-off phases. This results in more stable thermal conditions and fewer cold-start sequences, which limits fuel ingress into the oil. The relatively low share of urban driving declared for this vehicle further supports this interpretation. In contrast, several of the strongest viscosity reductions were observed in full-hybrid drivetrains that operate with frequent engine shutdowns and short combustion intervals. Samples 3, 4 and 5—originating from the Lexus IS300h, Suzuki Vitara and Volvo XC60, respectively—show decreases exceeding −30% at 40 °C and −23% at 100 °C. These vehicles were predominantly used on short routes (often below 10–20 km), where the engine rarely reaches full thermal stabilisation. Under such conditions, incomplete evaporation of unburned fuel facilitates its accumulation in the oil sump, explaining the large disproportionate drop in low-temperature viscosity and the accompanying rise in viscosity index. Sample 7 (Lexus NX, A25A-FXS) also showed a notable viscosity reduction despite a relatively high share of non-urban operation. In this case, the most likely contributing factor is the specific calibration of Toyota’s hybrid system, where the engine frequently shuts down even at moderate cruising speeds, causing repeated temperature cycling of the lubricant. A similar mechanism may explain the results for samples 8 and 9, originating from the Hyundai Tucson (G4FT) and Dacia Bigster (RYN7), respectively. Both vehicles exhibited pronounced viscosity losses, particularly at 40 °C, consistent with dilution by gasoline hydrocarbons. Their usage patterns—characterised by medium to high city-driving shares—reinforce the interpretation that stop-and-go operation and short intervals between combustion phases intensify the dilution phenomenon. Taken together, the results clearly demonstrate that viscosity degradation is not determined solely by mileage on the oil but is instead strongly linked to hybrid operating strategy, the combustion–electric interaction regime, and the temperature history of the lubricant. The consistent and substantial reductions in kinematic viscosity across nine of the ten analysed cases point to fuel ingress as the dominant degradation pathway in hybrid powertrains, while the comparatively stable behaviour of the mild hybrid Audi confirms that even partial stabilisation of thermal cycles can effectively limit this process.

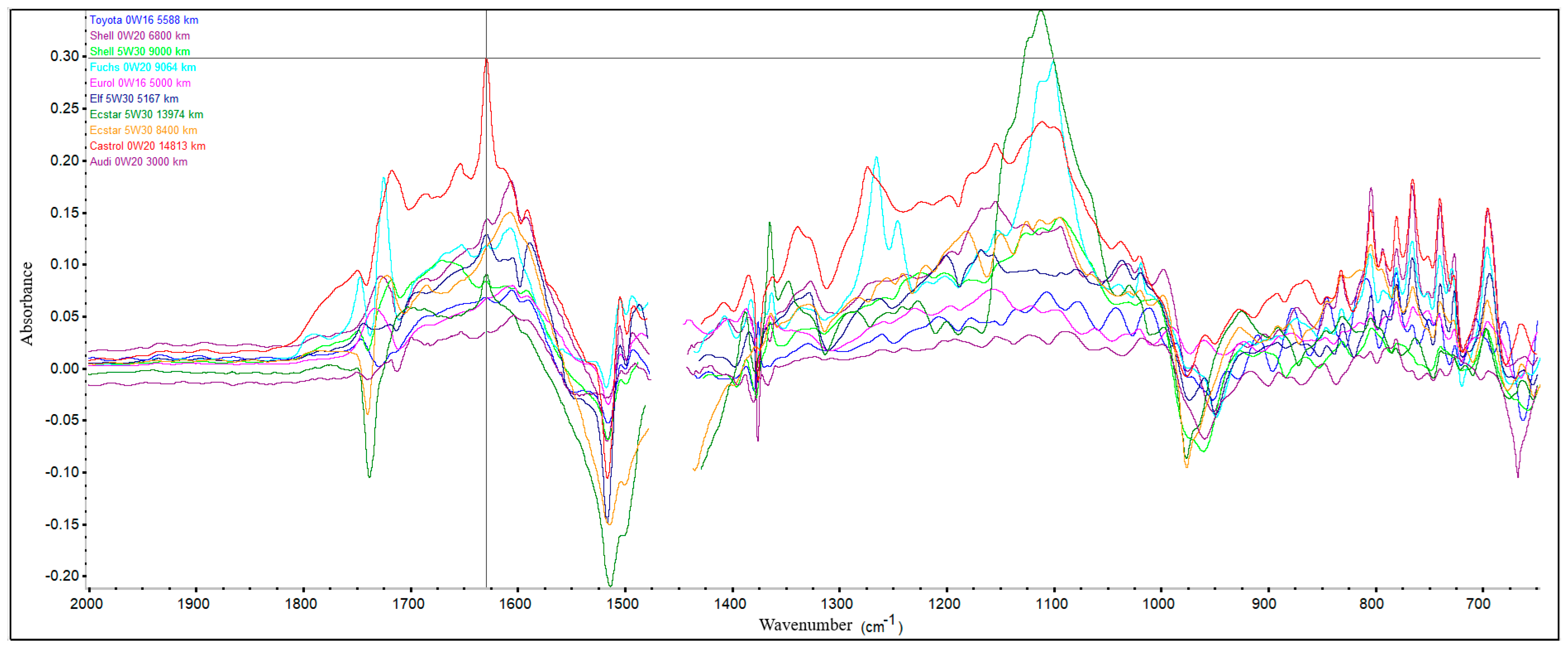

Figure 1 and

Figure 2 present the differential spectra for all the oils examined.

The corresponding FTIR-based degradation and contamination indices are listed in

Table 6 and

Table 7.

FTIR analysis revealed clear differences in the degradation mechanisms across the examined oil samples, reflecting both the operating conditions of the engines and the specific pathways of lubricant ageing. The strongest nitro-oxidative signals were observed for Castrol 0W20 (14,813 km), as indicated by the high intensity of the nitration band at 1630 cm−1 and pronounced oxidation peaks in the 1727–1747 cm−1 region. This sample also exhibited the highest level of contamination in the 3000–3600 cm−1 range and a distinct fuel-related signal, accompanied by a major reduction in viscosity. These combined effects suggest simultaneous fuel dilution, oxidation, and additive degradation, which is consistent with the operating pattern of an engine frequently subjected to cold starts and short-distance driving. A comparable pattern of oxidation and clear indications of fuel dilution was also detected for Fuchs 0W20 (9064 km). This sample demonstrated a substantial drop in viscosity and strong absorption in the 3000–3100 cm−1 region, confirming the presence of fuel. At the same time, the oxidation band around ~1700 cm−1 was notably intensified, consistent with the high-temperature stress experienced by small turbocharged engines operating under rapidly varying loads. Elevated nitro-oxidation levels were also observed in Elf 5W30 (5167 km), Shell 0W20 (6800 km) and Ecstar 5W30 (13,974 km). These oils share a common pattern of predominantly urban operation, characterised by short trips and delayed attainment of full operating temperature. The increase in nitration intensity suggests suboptimal combustion during the initial phase of engine warm-up, which promotes the transfer of combustion by-products into the lubricant. This agrees with moderate viscosity losses, although the effect is markedly weaker than in Castrol and Fuchs. Fuel-related signals in the ~800 cm−1 and 3000–3600 cm−1 regions were clearly visible for Castrol 14,813 km, Fuchs 9064 km, Shell 6800 km, Elf 5167 km, Toyota 0W16 (5588 km) and Eurol 0W16 (5000 km). In the Toyota and Eurol samples, the amplitude was significantly lower, which is consistent with the moderate viscosity decrease and the more stable, low-load operating conditions of their engines.

A different pattern was found for the two Ecstar 5W30 samples (13,974 km and 8400 km). Fuel-related signals were weak or absent, while the FTIR spectra showed strong degradation of additive packages, particularly within the 950–980 cm−1 region (EP additives) and around 3600 cm−1 (antioxidants). Both samples displayed a considerable viscosity decrease despite the lack of strong fuel dilution indicators, suggesting that polymeric viscosity modifiers and detergents were degraded, rather than diluted by fuel or oxidised. This mechanism is consistent with engines subjected to frequent thermal cycling, as is typical for many Suzuki powertrains. Several samples, including Audi 0W20 (3000 km) and Shell 5W30 (9000 km), did not show significant fuel-related absorption. Their moderate viscosity changes may therefore stem primarily from additive depletion or polymer shear, which aligns with more stable operating conditions and a smaller proportion of short-trip driving.

FTIR analysis also revealed notable differences in water contamination, assessed from the broad hydroxyl-associated absorption band in the 3100–3600 cm−1 region. Across the dataset, the contamination index ranged from 1.20 to 21.91 absorbance/0.1 mm, indicating that several samples accumulated substantial amounts of water during operation. The highest value was recorded for sample no. 5 (Castrol 0W20, 14,813 km), which simultaneously exhibited the strongest fuel-related signal, the most pronounced nitro-oxidation features, and the largest viscosity drop. Elevated water levels were also visible in samples 1, 2, 9 and 10, whereas the lowest value (1.20) was observed in sample no. 6 from the mild hybrid Audi, consistent with the milder operating conditions identified in the remaining analyses. Water accumulation is a characteristic phenomenon in hybrid powertrains, where frequent engine shut-downs and incomplete thermal stabilisation limit the evaporation of condensed moisture. Its presence may modify additive activity, accelerate antioxidant depletion and influence oxidation signatures in the FTIR spectra, making water an important co-factor in the degradation processes accompanying fuel dilution.

The FTIR results are consistent with the viscosity trends and enable the differentiation of samples dominated by oxidation, fuel dilution, or additive degradation. This highlights the diagnostic value of combining infrared spectroscopy with conventional laboratory methods when assessing oil ageing across a diverse set of engines and operating environments.

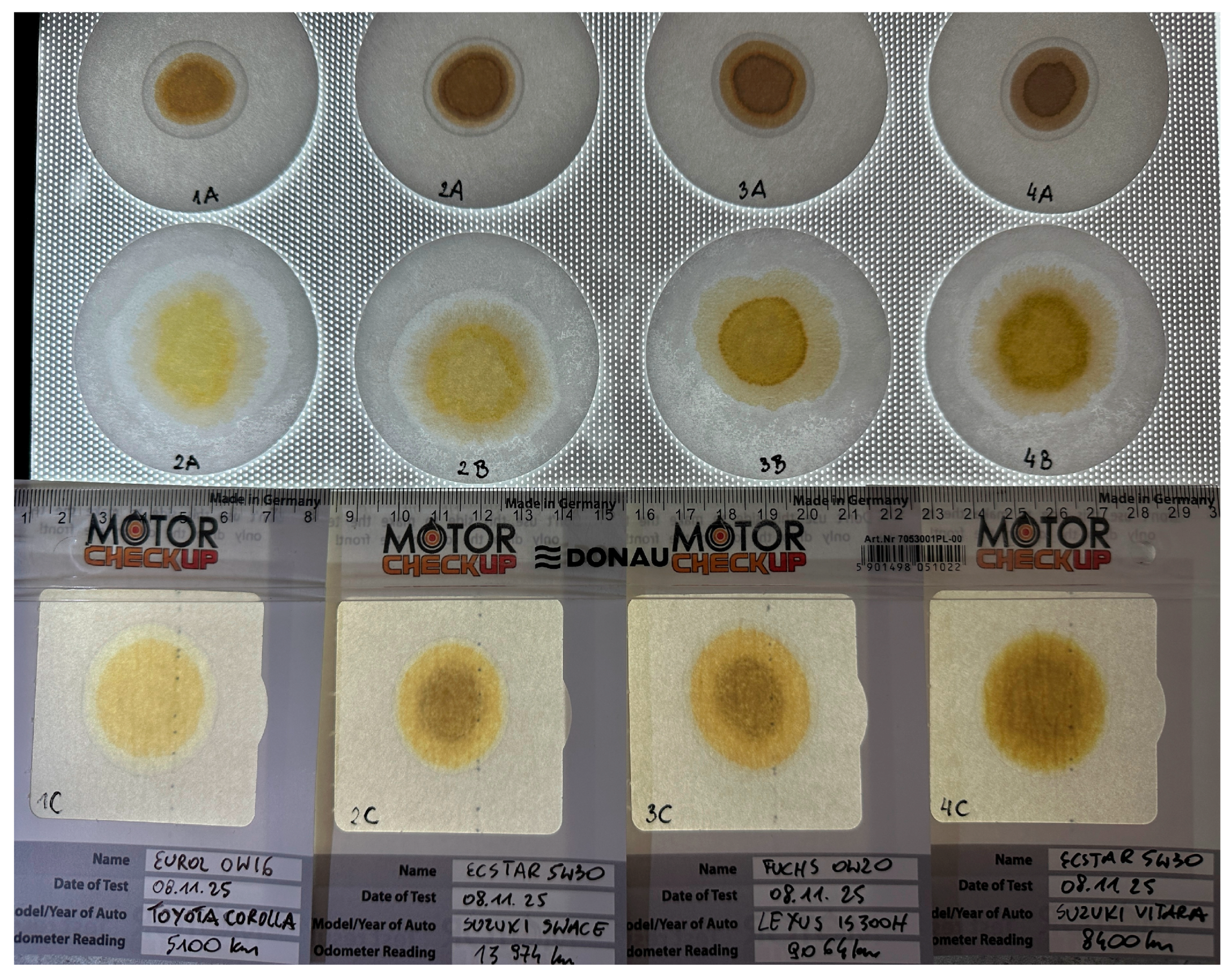

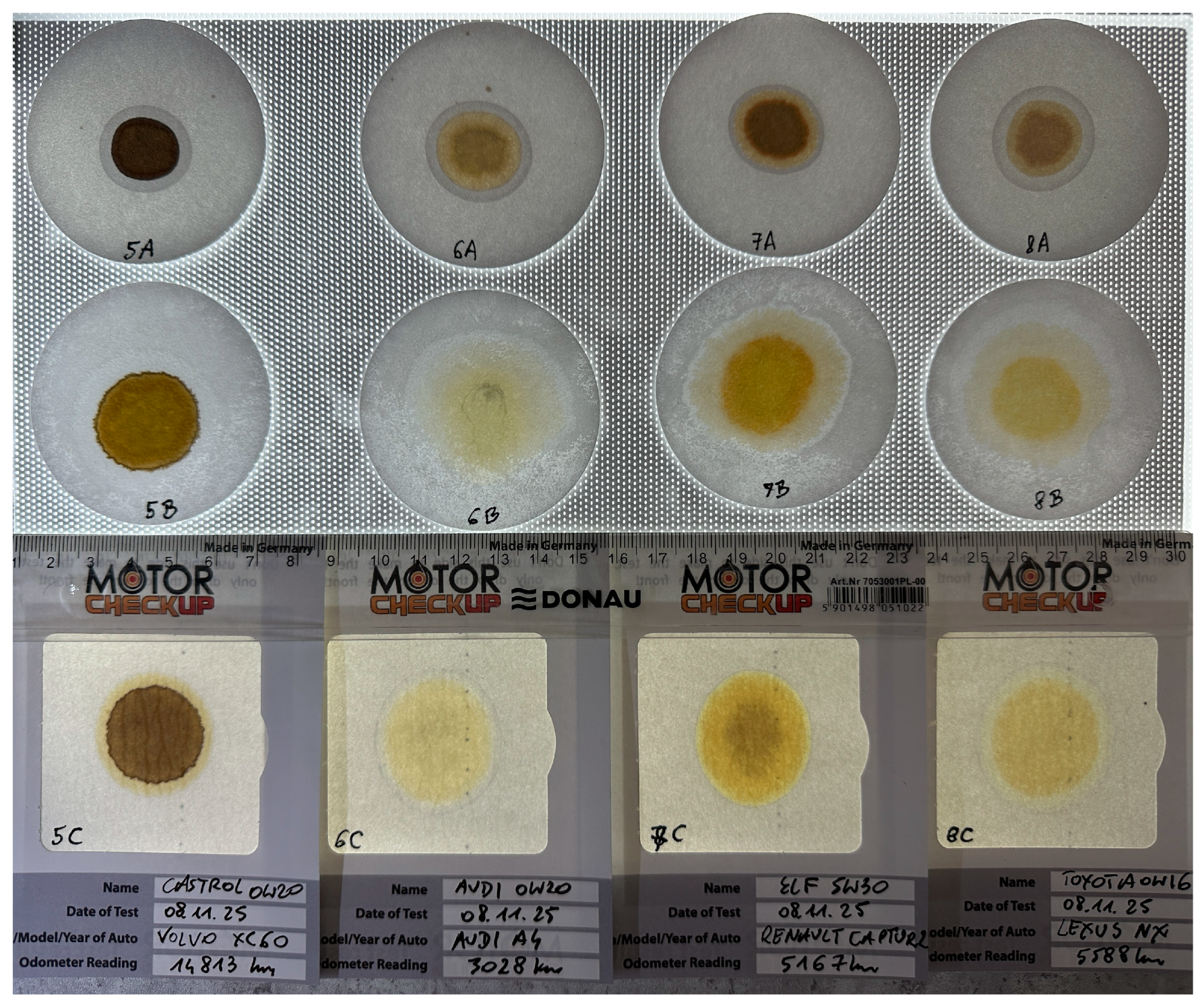

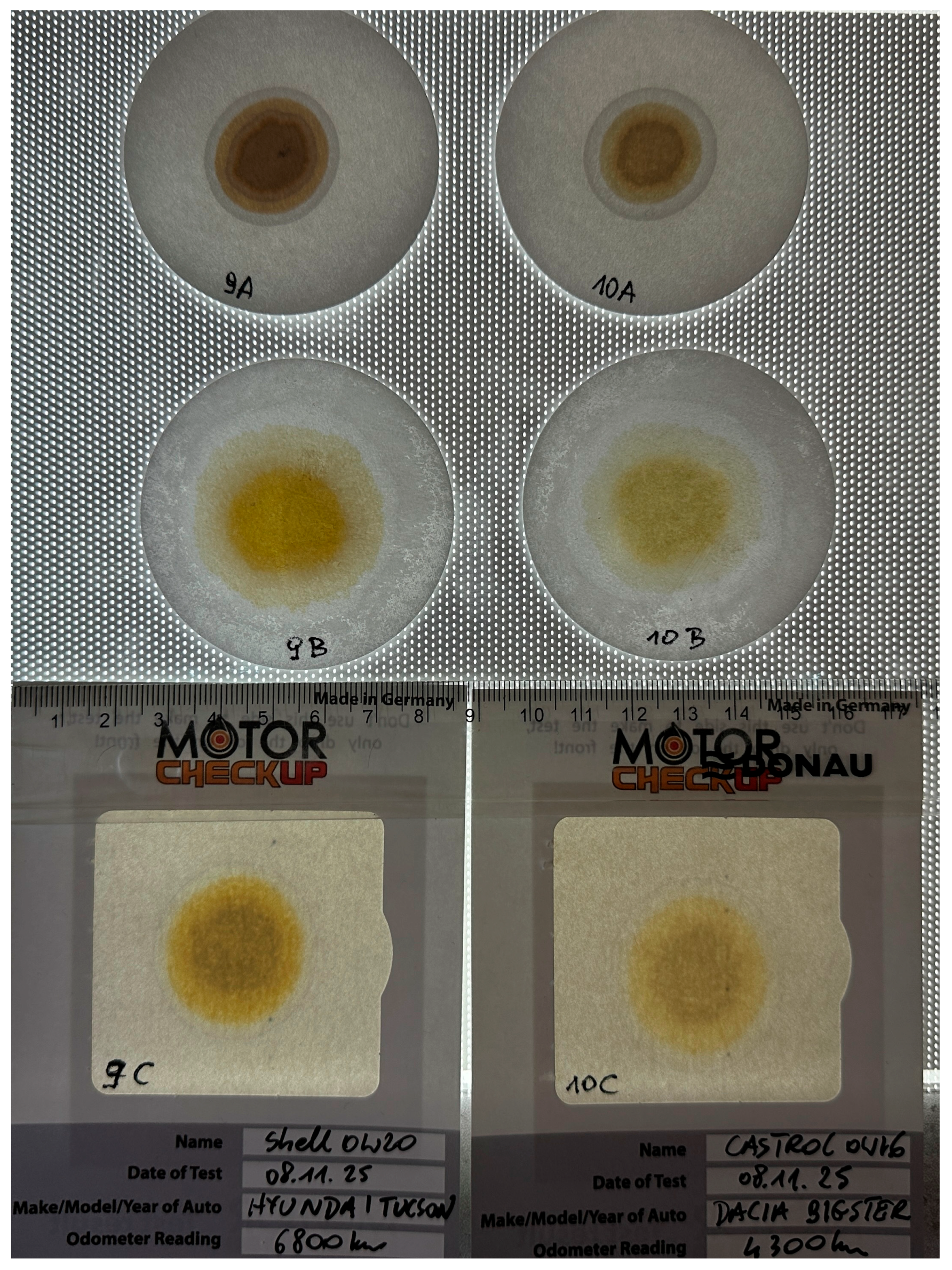

In several samples, the diffusion zones appeared expanded and uniform, with a relatively small central deposit (

Figure 3,

Figure 4 and

Figure 5). Such patterns can arise from increased mobility of the lighter oil fractions, and in the context of hybrid powertrains may potentially be linked with the presence of fuel-related volatiles. However, it should be emphasised that the chromatographic response is not exclusively governed by fuel dilution. The observed spread can also depend on the base oil composition (particularly in low-viscosity grades such as 0W16 and 0W20), additive chemistry, shear-induced changes in polymeric viscosity modifiers, and the overall thermal history of the lubricant. These factors complicate the interpretation and preclude a single, universal diagnostic criterion.

Conversely, samples with distinctly visible central deposits and more confined diffusion zones generally indicated the presence of heavier oxidation or nitration products, or simply lower relative volatility of the base oil. An example of this behaviour was observed in the mild hybrid powertrain, where the chromatograms displayed compact morphology despite the low measured viscosity drop. This illustrates that a large transparent halo alone does not necessarily signal fuel ingress, as it may also reflect limited degradation, higher freshness of the lubricant, or differences between oils from various manufacturers.

Overall, while certain qualitative tendencies in the chromatograms appear consistent with the viscosity trends—particularly in samples exhibiting substantial viscosity loss—the paper test should be regarded as an indicator rather than definitive proof of fuel dilution. The method is sensitive to multiple overlapping influences, and its diagnostic value increases when interpreted in parallel with quantitative measurements such as viscometry and FTIR spectroscopy. In this combined framework, the chromatographic patterns contribute additional, complementary insight into the evolving properties of the oils used in hybrid propulsion systems.

The interpretative accuracy of paper chromatography increases substantially when the visual patterns are considered alongside laboratory data, particularly viscosity measurements and FTIR spectral features. Even partial quantitative information allows the analyst to distinguish effects arising from the natural freshness or low viscosity grade of an oil from those more likely associated with fuel-derived volatiles. For example, oils with minimal viscosity loss but wide transparent halos can be recognised as exhibiting migration dominated by their inherent low-viscosity base stocks rather than by fuel ingress. Conversely, chromatograms showing expanded diffusion zones accompanied by marked decreases in kinematic viscosity or characteristic FTIR signals offer more credible evidence of dilution-related changes. This integrated approach helps isolate the contributions of multiple overlapping mechanisms and reduces the risk of misinterpreting the chromatographic response, reinforcing the value of combining rapid field tests with targeted laboratory analyses.

In the case of the Castrol 0W20 oil (14,813 km), the blot test (all three blots) is characterised by a distinct, clearly outlined dark core. Additionally, two of the blots exhibit a non-uniform, partially “ragged” contour around the central zone, which suggests phase separation and advanced degradation processes. On blot 5B, a broad, sharply defined outer ring is also observed—a transparent halo located beyond the typical diffusion region. Such an outer halo, clear and uniformly shaped, may indicate the migration and evaporation of volatile components present in the heavily degraded oil, including the potential contribution of fuel fractions. This morphology is fully consistent with the chemical results: the FTIR spectrum revealed the strongest fuel-related band in the entire dataset at approximately ~800 cm−1, together with pronounced nitro-oxidation features and a high level of overall contamination (3000–3600 cm−1). The sample also exhibited the most severe viscosity loss, confirming advanced physicochemical degradation. This suggests that the observed outer halo results from the combined effect of oxidative-nitro degradation and fuel dilution, which promotes the migration and evaporation of light hydrocarbons beyond the standard diffusion zone.

A distinctly different morphology is observed for samples 6, 1 and 8, which showed the smallest viscosity decrease, not exceeding 20%. Their blots display a very light colouration, a wide, homogeneous diffusion zone, and a clear, uniform, transparent outer halo devoid of the disturbances seen in the Castrol sample. The most striking feature, however, is the absence of a sharply defined dark core on the MCU blots—a characteristic typically associated with oils contaminated by fuel or soot. When combined with the FTIR data and viscosity results, this morphology suggests that: the fuel content in these oils was minimal, degradation was dominated by natural ageing, rather than strong fuel dilution, the low level of heavy contaminants promoted a uniform blot structure without core formation. In these samples, the correlation between low viscosity loss and clean, bright blot morphology is the most consistent within the entire dataset. This supports the hypothesis that the dark core in MCU blot tests may be partly indicative of an elevated fuel fraction or its degradation products, while its absence corresponds to oils undergoing less intensive physicochemical deterioration. This pattern is also supported, albeit to a lesser extent, by sample 10, which shows a very light central zone and no FTIR evidence of fuel dilution.

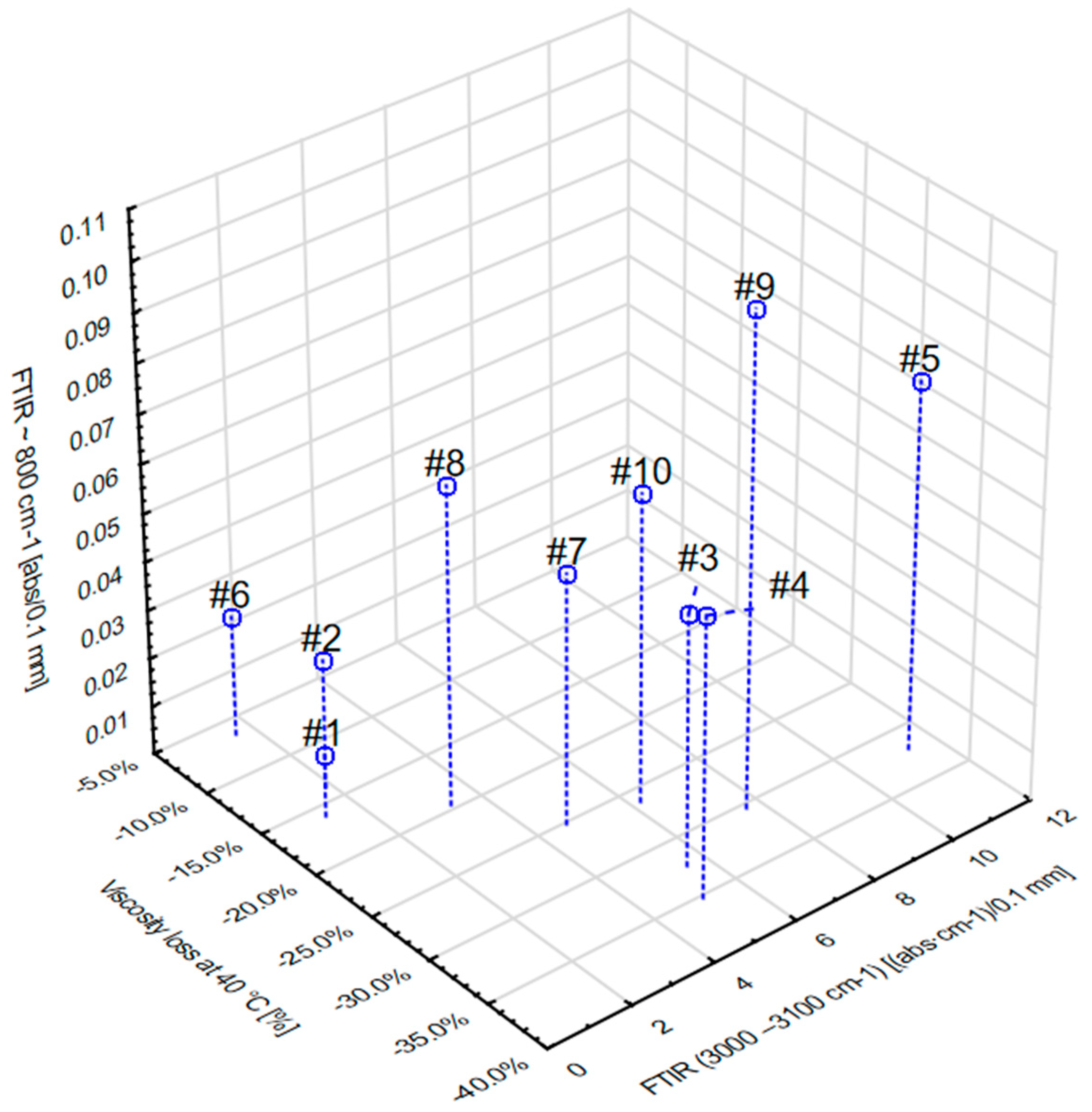

To strengthen the qualitative interpretation derived from the blot test and FTIR spectra, a three-dimensional correlation plot (

Figure 6) was prepared, combining three key diagnostic variables: the relative viscosity loss, the intensity of the ~800 cm

−1 band associated with fuel-related signals, and the contamination index calculated for the 3000–3600 cm

−1 region. The resulting spatial distribution clearly separates samples containing measurable amounts of fuel from the remaining oils. Sample no. 5 (Castrol 0W20, 14 813 km) occupies an extreme position in this 3D space, showing the highest viscosity loss, the strongest fuel-related FTIR peak, and the highest contamination level. These findings are fully consistent with the morphology observed in the blot test, which exhibited a distinct dark core, an irregular outer boundary and a wide, transparent halo. Sample no. 9 (Fuchs 0W20, 9064 km) also clusters in the high-fuel, high-degradation region, confirming good agreement between the analytical methods. In contrast, samples no. 1, 6 and 8 show both minimal viscosity reduction and a very low fuel-related FTIR signal; this corresponds well with their bright, uniform blot morphology without a defined central core. The plot therefore reveals a coherent relationship between FTIR results, viscosity changes and chromatographic blot appearance, indicating that the blot test can provide a rapid and reliable visual indication of fuel dilution, particularly for strongly degraded samples.

The relationship between fuel dilution and parallel degradation processes involves several overlapping mechanisms that cannot be fully distinguished on the basis of field samples alone. However, the data reveal characteristic trends that help clarify their concurrent occurrence. Fuel dilution lowers viscosity and weakens the lubricant film, which can increase susceptibility to oxidation and nitration under thermally unstable operating conditions. At the same time, dilution of polar species may reduce the apparent intensity of oxidation bands in FTIR spectra. These effects may coexist, particularly in hybrid engines operating at temperatures insufficient for complete evaporation of light fuel fractions. In the examined dataset, strong fuel-related FTIR signals generally occurred together with elevated oxidation and additive-depletion markers, indicating that in practical hybrid operation fuel dilution is more likely to accompany and potentially facilitate chemical degradation than to suppress it.