Abstract

The growing necessity to decarbonize the global energy system has positioned green hydrogen as a central enabler of a secure and sustainable future. Among various production paths, water electrolysis has emerged as the most developed route for generating high purity hydrogen from renewable power. The paper includes a broad and comparative overview of four leading electrolyzer technologies: Alkaline Water Electrolyzers (AWE), Proton Exchange Membrane Electrolyzers (PEM), Solid Oxide Electrolyzer Cells (SOEC), and new Anion Exchange Membrane Electrolyzers (AEM). Key technical parameters, operating principles, system level properties, and innovation trends are discussed, with a particular emphasis on their deployment and application in different regions of Canada. The study also highlights Canada’s growing role in the global hydrogen economy, supported by vast renewable resources, a favorable policy environment, and a dense network of research facilities and technology hubs. By combining comparative insights and tying them to national energy strategy, this survey establishes the agenda for driving adoption and innovation in electrolyzers in Canada’s clean energy shift.

1. Introduction

The role of hydrogen as a pivotal clean energy vector is becoming broadly acknowledged, given its necessity for the deep decarbonization of challenging industries, such as steel and heavy transportation, and for facilitating long-duration energy storage [1]. Historically, hydrogen production has evolved from early coal gasification and water-gas shift processes to modern natural gas steam reforming, electrolysis-based pathways, and emerging renewable-driven production routes. A detailed examination of this technological transition from fossil-fuel-based methods toward sustainable renewable sources is provided by Megía et al. [2], which highlights the progression toward cleaner and more sustainable hydrogen systems. Among numerous production pathways, water electrolysis is the most potential low emission production pathway for producing completely green hydrogen, especially when fueled by renewable energy sources, especially when powered by renewable energy sources like wind, solar, or hydropower [3]. The clean energy shift is made possible by electrolyzer technologies, which use electricity to split water into hydrogen and oxygen [4]. It enables the integration of large amounts of variable and intermittent renewables into the grid by providing a means to store surplus energy seasonally in chemical form [1].

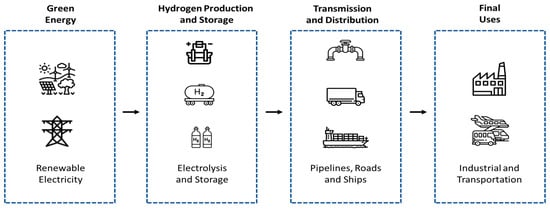

It is essential to comprehend how electrolyzers fit into the larger ecosystem of hydrogen generation, distribution, and end-use in order to completely appreciate their transformative potential in the clean energy transition. This integrated value chain is depicted in Figure 1 [5]. Electrolyzers are essential for the production of clean hydrogen and, critically, serve as a fundamental tool for optimizing power grid management, integrating various energy sectors, and establishing a sustainable, low-carbon economic model. [6].

Figure 1.

Global Green Hydrogen Value Chain.

Canada is emerging as a key player in the global hydrogen market, leveraging its abundance of renewable resources, foundational industry infrastructure, and robust policy support at federal and provincial levels [7].

Although the paper provides detailed descriptions of electrolyzer technologies, these sections are intended to serve as essential background to support the broader objective of analyzing Canada’s deployment landscape, policy directions, industrial ecosystem, and technological opportunities. The objective of this paper is to give a concise, comparative overview of the prevalent electrolyzer technologies like Alkaline Water Electrolyzers (AWE), Proton Exchange Membrane (PEM) Electrolyzers, Solid Oxide Electrolyzer Cells (SOEC), and Anion Exchange Membrane (AEM) Electrolyzers and their suitability, deployment, and unique applications in the Canadian context. By bringing together technical, commercial, and policy perspectives, this survey will inform researchers, industry stakeholders, and policymakers on the current state and future potential of electrolyzers in powering Canada’s clean energy shift.

2. Overview of Hydrogen Electrolyzer Technologies

Hydrogen electrolyzers are at the heart of the green hydrogen value chain, enabling the production of storable, transportable, and ready-to-use hydrogen fuel from renewable electricity. With the world’s interest in decarbonization picking up, cost-effective, efficient, and long-lasting electrolyzer technologies have played a central role in making a sustainable hydrogen economy a reality through their development and deployment [6]. This Section introduces the four main types of water electrolyzers with their foundation principles, history, and uses in current and future energy systems. The schematics for these four electrolyzers types can be accessed at [3,8]

2.1. Alkaline Water Electrolyzers (AWE)

Alkaline water electrolysis is the most matured and comprehensively implemented commercially employed hydrogen production technology, with commercialization in excess of one century. AWE systems are based on a liquid electrolyte alkaline material most commonly potassium hydroxide (KOH) or sodium hydroxide (NaOH) that allows for the transfer of hydroxide ions (OH−) between the two electrodes [3]. The technology uses low-cost, non-noble metal catalysts such as nickel or iron that keep the cost of technology low and enables it to be operated in long lifespan modes, in most instances 60,000 to 90,000 h [9]. Hydrogen produced by AWE is usually 99.3% to 99.8% pure, which is sufficient for most industrial applications such as ammonia synthesis, refining, and chemical synthesis [10].

Although these advantages are present, AWE systems have low current densities and slow dynamic response times, usually on the order of seconds to minutes and thus are less appropriate for applications where rapid cycling or load-following is required. Their response lag also makes them incompatible with variable renewable sources of energy [11]. Their size being a drawback in confined space scenarios is another limitation. But AWE is highly scalable, from kilowatts to and over 150 megawatts, with gigawatt scale plants planned. Its capability to run in steady-state mode with dependable and reliable energy supplies like hydropower in Quebec and British Columbia is a testament to its relevance in the clean hydrogen economy.

2.2. Proton Exchange Membrane (PEM) Electrolyzers

PEM represent an important breakthrough in electrolytic hydrogen production using a solid polymer electrolyte membrane commonly made of Nafion that carries protons (H+) from the anode side to the cathode side [12]. This arrangement is possible for compact and modular designs, allows for increased current densities, and facilitates hydrogen production at pressures that are generally up to 80 bar. The purity of hydrogen attained is typically above 99.999%, and therefore PEM systems are particularly suitable for sensitive uses such as hydrogen fuel cell cars, semiconductor manufacturing, and export markets where high purity levels must be upheld [13].

The fast dynamic response of PEM systems places them aptly for integration with renewable energy sources that are intermittent in nature such as wind and solar. However, the technology is still constrained by its reliance on rare and expensive noble metal catalysts like platinum and iridium, which contribute to high capital investments [14]. Longevity is also a concern, because the membrane and catalyst layers are prone to acid degradation at high current densities, which can reduce stack lifetimes to around 40,000 h [15]. PEM require high-purity deionized water, and that the operation and maintenance of the water treatment subsystem (including polishing filters and monitoring equipment) contribute significantly to overall operational cost [16]. Despite these challenges, PEM are now a first-choice technology in many real-world applications, including hydrogen refueling stations, backup power systems, and export terminals [13]. Their ability to respond fast and deliver high-purity hydrogen at varying operating conditions makes them a favorite contender in both grid-interactive and mobility-directed applications.

2.3. Solid Oxide Electrolysis Cells (SOEC)

Solid oxide electrolysis cells are high-temperature devices typically between 700 °C and 900 °C that use a solid ceramic electrolyte such as yttria-stabilized zirconia (YSZ) to transport oxygen ions from the cathode to the anode [17]. The high temperature significantly improves thermodynamic efficiency, and thus, SOECs can achieve electrical-to-hydrogen conversion efficiencies of more than 80% if waste heat or high-temperature thermal energy is available [18]. Without external heat sources, however, some of the input electricity must be used for heating, which can cancel out part of the efficiency gain.

A unique aspect of SOECs is that they may be operated for co-electrolysis of water (H2O) and carbon dioxide (CO2) to produce syngas, a valuable precursor to synthetic fuels and chemicals [19]. This does not require a fundamentally different electrolyzer design, but rather the gas feed composition and downstream separation processes are modified to accommodate more than one product. While SOECs benefit from high efficiency and compact solid-state design, commercialization has been hampered by high-cost materials, complex thermal management, and mechanical degradation under thermal cycling [20]. Stack sizes vary from 100 to 500 kW, and the majority of the systems are at pilot or demonstration levels. The high operating temperatures also create integration challenges with variable or intermittent power sources. In fact, SOECs are more suited to base-load steady industrial applications or coupling with high-grade thermal sources like nuclear or concentrated solar power [21]. Although SOEC stacks are quite compact due to the solid-state design, the need for heat exchangers and insulation can increase the system volume.

2.4. Anion Exchange Membrane (AEM) Electrolyzers

AEM are a next-generation low-temperature water-splitting technology that seeks to combine the beneficial attributes of alkaline and PEM technology. These systems utilize a solid polymer membrane to conduct anions, hydroxide ions (OH−) from cathode to anode [3]. The membrane itself is used as the electrolyte in AEM systems and is distinct from the liquid electrolyte used in conventional AWE systems. By permitting operation in slightly alkaline conditions and with non-precious metal catalysts such as nickel or cobalt, AEM aim to reduce both the operating and capital costs [22].

Current AEM systems are capable of producing hydrogen purities greater than 99.9% [23] and modular designs are employed in small- to medium-scale installations ranging from a few kilowatts up to over 1 MW. These features make AEM particularly attractive to off-grid, remote, or distributed applications, including Northern Canada microgrids or islanded villages in search of diesel generator alternatives. Although the first-generation systems showed high efficiency and fast response (on the order of seconds), durability is still a major limitation [24]. High-voltage and high-current density membrane degradation limits current stack lifetimes to a range of about 5000 h, though progress is being made toward achieving 10,000–30,000 h milestones [23]. Despite these challenges, AEM technology is attracting attention for its potential PFAS-free alternative to PEM systems, with ongoing research toward improving ionic conductivity and operational lifetime [25]. As for enhancing material stability and system reliability, AEM can be a cost-efficient, flexible alternative to both AWE and PEM in most decentralized energy applications.

2.5. High-Level Comparison and Development Context

The hydrogen economy’s changing priorities from industrial-scale, steady-state production to dynamic, dispersed, and renewable-integrated systems are reflected in the development of electrolyzer technology. A high-level comparison of the four primary electrolyzer types is shown in Table 1 [8,12,26,27,28,29,30] which also summarizes important performance indicators and operational factors.

Table 1.

Comparison of main electrolyzer types by core performance parameters.

Numerous criteria, such as production scale, the available energy supply, the necessary hydrogen purity, and economic considerations, influence the choice of electrolyzer technology. The current commercial environment is dominated by alkaline and PEM systems, although SOEC and AEM technologies are developing quickly because to the demand for increased operational flexibility, reduced costs, and increased efficiency. Large-scale, sustainable hydrogen production and the larger shift to clean energy will be made possible by the ongoing development of these technologies.

3. Electrolyzer Deployment and Applications in Canada

Thanks to its developing industrial expertise, favorable governmental climate, and abundance of renewable energy resources, Canada has emerged as one of the most promising regions for the progress of clean hydrogen technologies. The government has made electrolyzer deployment a key element of its decarbonization plan, with pledges to attain net-zero emissions by 2050 and a national hydrogen policy introduced in 2020 [31]. The present status of electrolyzer adoption in Canada is highlighted in this section, along with important manufacturers, significant projects, and sector-specific applications in different regions.

3.1. National Hydrogen Strategy and Policy Landscape

The Canadian Hydrogen Strategy, published in December 2020 by Natural Resources Canada, outlines a vision for putting Canada at the forefront of producing, using, and exporting clean hydrogen. The strategy highlights the potential of hydrogen to supply up to 30% of the country’s end-use energy needs by 2050 [7], reducing greenhouse gas emissions by as much as 45 megatonnes annually, and making a serious contribution to economic growth through innovation and infrastructure investment.

Federal and provincial governments have begun harmonizing incentives, investments, and regulatory frameworks to enable this vision. This includes funding for pilot projects, tax credits, clean electricity goals, and hydrogen exportability feasibility studies [32]. Because of the possibility for renewable integration and provincial incentives, the majority of near-term projects concentrate on Alberta, British Columbia, and Quebec [31]. Pertinently, Quebec’s Plan for a Green Economy and Alberta’s Hydrogen Roadmap reflect high provincial commitments specific to regional energy resources [33,34]. Quebec’s vast hydropower source renders it highly competitive in low-cost electrolysis through either AWE or PEM systems, whereas Alberta’s interest in wind-powered PEM options stems from its high capacity for winds and experience with energy infrastructure.

In addition, hydrogen is the core of Canada’s Clean Fuel Standard, Net-Zero Emissions by 2050 Act, and new Investment Tax Credits within the Federal Clean Energy Plan [7]. Together, the policies facilitate a favorable environment for large-scale as well as distributed deployment of electrolyzers.

3.2. Key Canadian Electrolyzer Manufacturers and Innovators

Canada has an up-and-coming base of electrolyzer developers, integrators, and system-level innovators. These companies not only are supporting in-country hydrogen production but also are inserting themselves in global value chains in electrolyzer segment and system design.

3.2.1. Hydrogen Optimized (Owen Sound, Ontario)

Concentrating on high-current Alkaline Water Electrolyzers (AWEs), Hydrogen Optimized has developed its Rugged Cell™ technology for utility-scale integration with renewable sources such as wind and solar [35]. The company is aimed at industrial customers and export markets, with systems available to go to the hundreds of megawatts.

3.2.2. Next Hydrogen (Mississauga, Ontario)

Unique to modular alkaline technology, Next Hydrogen has a proprietary cell-stack design that is optimal for variable power input and well suited to variable renewable energy supplies [36]. The company has various joint ventures that include partnerships with Hyundai and Black & Veatch with an aim of scaling up green hydrogen production in Canada and globally [37].

3.2.3. Enapter (Deployment in PEI)

Based in Germany but piloting its AEM electrolyzer system on Prince Edward Island as part of off-grid renewable microgrids, Enapter has a product design in small, stackable modules most suitable to decentralized uses in remote or rural regions of Canada [38,39].

3.2.4. HTEC (Vancouver, British Columbia)

A key player in PEM electrolyzer integration, HTEC is involved in hydrogen refueling infrastructure, supplying green hydrogen for Fuel Cell Electric Vehicles (FCEVs) across British Columbia [40]. The company supports Canada’s hydrogen mobility agenda and plays an important role in commercial fleet decarbonization.

As indicated in the overview in Table 2, Canadian electrolyzer manufacturers contribute not only to domestic hydrogen development but also create value through targeted innovation: Hydrogen Optimized and Next Hydrogen advance high-current-density alkaline technologies optimized for renewable integration; HTEC enables PEM-based mobility solutions; and Enapter’s deployments demonstrate modular AEM capabilities suitable for distributed and remote applications. These strengths in total indicate a promising direction for Canada as a developer of flexible, renewable-ready electrolyzer systems with strong commercial and export potential [35,36,37,38,40].

Table 2.

Table of Canadian Electrolyzer Companies and Technology Types [35,36,37,38,40].

3.3. Major Electrolyzer Projects and Demonstrations

Canada’s hydrogen future is being brought to life by a series of high-impact initiatives across the country. These encompass large-scale major green hydrogen production facilities to innovative pilot demonstrations in microgrids and transportation.

3.3.1. Air Liquide Bécancour (Quebec)

This 20 MW PEM electrolyzer facility, commissioned in 2021, uses low-cost hydroelectric electricity and produces over 3000 metric tonnes of green hydrogen annually [39]. It supplies industrial end-users and powers hydrogen refueling networks in eastern Canada. The project is one of the largest commercial PEM in the world, solidifying Canada’s leadership in scaling green hydrogen.

3.3.2. Varennes Carbon Recycling Electrolyzer Facility (Varennes, Québec)

Hydro-Québec, in collaboration with Varennes Carbon Recycling (VCR), is supporting the development of a 90 MW proton exchange membrane (PEM) electrolyzer facility in Varennes, Québec. Accelera by Cummins will supply the electrolyzer system, replacing the original agreement with Thyssenkrupp [41]. This state-of-the-art facility will produce up to 40 metric tonnes of green hydrogen per day amounting to approximately 14,600 metric tonnes annually, powered entirely by Québec’s clean and renewable hydroelectric grid.

The green hydrogen and oxygen produced will be primarily used by the adjacent VCR biorefinery, a project led by Enerkem with partners including Shell, Suncor, and Proman [42]. The facility will convert non-recyclable waste and residual biomass into low-carbon fuels and circular chemicals, helping reduce carbon emissions in the transportation and chemical sectors. Once operational in 2025, this will be among the largest electrolyzer deployments in North America, advancing Canada’s position as a global leader in the renewable hydrogen economy.

3.3.3. World Energy GH2—Nujio’qonik Project (Newfoundland and Labrador)

This is Canada’s largest green hydrogen export project to date. Phase one will be 3 GW of wind and 500+ MW of PEM electrolysis producing hydrogen for conversion to green ammonia for European markets [43]. This project will bring new economic growth for the region and positions Atlantic Canada as a hydrogen export center.

3.3.4. EverWind Fuels (Nova Scotia)

EverWind Fuels’ Point Tupper project in Nova Scotia, with Nel Hydrogen as partner, is a pioneering green ammonia facility fed from wind-sourced Proton Exchange Membrane (PEM) electrolyzers that will produce 240,000 metric tonnes per annum of ammonia from 2026 [44]. The project leverages the renewable energy of Nova Scotia to supply green ammonia to Germany, powering the Canada-Germany Hydrogen Alliance [45]. The PEM technology in the project offers 99.9–99.999% hydrogen purity, which can be used in industrial and future mobility applications and lifetimes of 20,000–80,000 h, positioning Atlantic Canada as a green hydrogen hub.

3.3.5. Enapter Green Hydrogen Project (Prince Edward Island)

Enapter is deploying two AEM Multicore 1 MW electrolyzers on Prince Edward Island within a 2 MW green hydrogen project. The project is aimed at making the transition of the region towards independence a reality through the production of hydrogen from renewable sources of power, including solar and wind. With an overall capacity of up to 900 kg of hydrogen per day, the system operates at pressures up to 35 bar without external compression and releases hydrogen in 99.9% purity, with the potential to go over 99.999% using an integral dryer [23]. The project is a major demonstration of modular AEM electrolyzer technology in a distributed, renewable-powered environment.

The above projects are reflected in Figure 2 which shows where these projects are on the map across the country.

Figure 2.

Map of Major Electrolyzer Projects in Canada. (Prepared by the authors based on data from provincial energy reports, industry publications, and CHA/CHFCA project listings).

3.4. Sectoral Applications Across Canadian Provinces

Electrolyzer deployment in Canada includes diverse applications and geography, each aligning with provincial energy mix and decarbonization plans.

3.4.1. Industrial Sector (Quebec, Ontario)

Electrolyzers are being used to supply green hydrogen to steel producers, fertilizer manufacturing plants, and petrochemical plants. The provinces already have the heavy industry infrastructure and renewable energy assets [46]. For example, Alberta and Saskatchewan are focusing on blue hydrogen hubs via steam methane reforming with carbon capture, while Quebec and British Columbia. support green hydrogen through hydro-powered electrolysis [47].

3.4.2. Mobility and Transportation (British Columbia)

It can be said that British Columbia leads Canada in terms of hydrogen fuel cell adoption, and PEM are supplying clean hydrogen to hydrogen fueling stations, delivery trucks, and transit bus fleets. It is supporting the province’s zero-emission vehicle policies and clean transportation goals [48].

3.4.3. Export-Oriented Production (Atlantic Canada)

Offshore wind resources-rich Atlantic provinces with deep-sea ports, are emerging as hubs for exporting green hydrogen and ammonia for the European continent, which is seeking to import clean energy to meet RE-Power EU goals.

3.4.4. Remote and Off-Grid Communities (Northern Canada, PEI)

Low-maintenance and modular technology like AEM is particularly suited to off-grid electricity, offering clean alternatives to diesel generators. The technology is under test for microgrid deployment, energy storage, and stand-by power [49].

Together, these applications demonstrate a decentralized yet planned approach with provinces playing to their respective strengths and electrolyzer technologies being aligned to provincial needs. This approach enhances national energy resilience and provides a demonstration of hydrogen’s flexibility in a decarbonized Canadian energy mix.

4. Comparative Assessment and Innovation Trends

The deployment of electrolyzer technologies by application and geographic market depends on a combination of technical, economic, and operating considerations. While Section 2 focused on performance, cost, and integration potential, this Section considers more closely the operation of electrolyzers in dynamic, real-world conditions, particularly where scalability, ramp rate, voltage requirements, and efficiency with varying loads are at stake.

Familiarity with these system-level features is important in the selection of technologies for use in renewable energy integration, distributed energy systems, and industrial-scale hydrogen production, all of which are central to Canada’s clean energy plan. In addition, this section shows key areas of technological innovation and how the advancements align with Canada’s national energy priorities.

4.1. System-Level Operational Comparison

Electrolyzers are also differentiated from each other based on how well they perform the electricity-to-hydrogen conversion, how they handle varying power input, how scalable they are, and how their voltage and efficiency profiles vary with different levels of production [8]. These differences have significant implications for integrating electrolyzers with variable renewable energy sources like solar and wind, where transient response and partial-load efficiency are key aspects in the operation of the system.

The following Table 3 presents a summary of every significant type of electrolyzers operating on three system scales (small, medium, and large) [1,3,11,50,51,52].

Table 3.

System-Level Operational Characteristics by Electrolyzer Type and Scale.

This analysis provides the following insights:

- PEM are highly flexible and well-suited to regions with intermittent renewable energy [53], such as Atlantic Canada and Alberta, where there is high ramping and need for high purity hydrogen.

- AWE systems, while slower to respond, remain economical and reliable when paired with stable electricity sources like Quebec’s or British Columbia’s hydropower.

- SOECs are highly efficient in steady load industrial operations but are difficult to operate and unsuitable for fast varying load conditions.

- AEM are an emerging option for off-grid and remote usage pursuing energy autonomy based on their fast response and modularity.

A broader system-level comparison also provides important differences in low-power performance, safe shutdown behavior, and start-up requirements across electrolyzer technologies. PEM can maintain stable operation at low current densities and transition into standby modes with minimal efficiency loss, and they support rapid and safe shutdown sequences due to their compact cell design [54]. AWE units have limited low-power flexibility and require controlled shutdown procedures because of slower gas-purging dynamics and electrolyte management constraints [55]. SOEC systems face strong restrictions at low power because their ceramic electrolytes and interconnects operate at very high temperatures, which necessitates carefully managed thermal cycling and gradual shutdown processes [56]. AEM, just like PEM, show a stable low-load operation due to their polymer-based membrane structure and low-temperature operation [57]. These additions yield a more complete representation of system-level behavior and complement the operational values summarized in Table 3.

4.2. Innovation Trends in Electrolyzer Technology

To address obstacles and expand applicability, intense R&D is focused on materials, design, and control systems. Four key areas of innovation are noteworthy:

- Non-Precious Metal Catalysts

It is the finding of low-cost and earth-abundant catalysts that is a top priority particular for PEM and AEM systems currently depending on expensive metals like platinum and iridium. Alternatives such as nickel-iron oxides, cobalt-phosphates, and metal nitrides are under development [58]. It is also important to note that, beyond catalyst cost, PEM and AEM systems rely on expensive hardware components such as titanium bipolar plates, titanium porous transport layers, and nickel-based structures, which contribute significantly to overall stack cost [59].

- 2.

- Durable and High-Performance Membranes

Longevity of electrolyzers is frequently constrained by degradation of the membrane in extreme conditions. Studies on fluoropolymer-based PEMs and alkaline-stable AEMs focus on enhancing capability to withstand chemical and thermal fatigue, particularly for high-frequency cycling environments [23]. In Canada’s cold climate, start-up reliability and minimizing downtime are critical to performance throughout the year.

- 3.

- Modular and Scalable Architectures

Products like Enapter’s AEM Multicore are indicative of a new direction toward stackable electrolyzer modules [60]. This type of design supports decentralized, flexible installation suitable for remote sites or phased project development. Canada’s vast geography and presence of off-grid villages make the technology particularly suitable.

- 4.

- Bi-Directional and Hybrid Systems

New Unitized Regenerative Fuel Cells (URFCs) and bi-directional electrolyzers can switch between hydrogen production and electric power generation. They have long-duration storage and grid backup, and potentially could contribute to rural and extreme-weather regions of Canada for critical infrastructure resiliency [61]. Current research focuses on improving internal components, including hierarchical electrode designs and stratified porous transport layers, in order to manage the different mass-transport and water-management requirements of the two operational modes [62]. While they are still in an experimental phase, their potential value is significant.

Within the Canadian research landscape, notable progress has been made in accelerating electrolyzer innovation, particularly in the areas of catalyst development and cold-climate system reliability. Several Canadian research groups have reported advances in nickel–iron and cobalt-based oxygen evolution catalysts capable of reducing dependence on precious metals [58,63,64]. Parallel efforts are underway at national research centers and university laboratories and the National Research Council (NRC), where ongoing work focuses on improving membrane durability and enhancing cold-weather startup performance. These two challenges are especially relevant for northern microgrid applications. In addition, Canadian companies such as Hydrogen Optimized and Next Hydrogen are actively testing large-area electrodes and dynamic-load alkaline systems designed specifically for renewable-energy integration. These developments reflect strong alignment between academic research and industrial deployment pathways [35,36,49].

4.3. Alignment with Canada’s Energy Priorities

Federal and provincial governments have begun harmonizing incentives, investments, each innovation area supports Canada’s specific needs:

- For cold-climate resilience, particularly during standby or cold start-up conditions integrated thermal management such as insulation, heat tracing, and/or waste-heat recovery is necessary to keep the electrolyzer stack at its operating temperature (e.g., 50–80 °C for PEM and 60–80 °C for AWE) even when outside temperatures drop below 0 °C.

- Decentralized energy requires modular and low-maintenance systems for remote and First Nations communities.

- Export competitiveness favors scalable, high-purity, and high-efficiency systems like PEM and potentially SOEC for bulk export of ammonia or hydrogen from Atlantic ports.

- Grid balancing and renewable smoothing are enabled by fast-acting PEM and AEM technologies able to cope with variable wind and solar profiles.

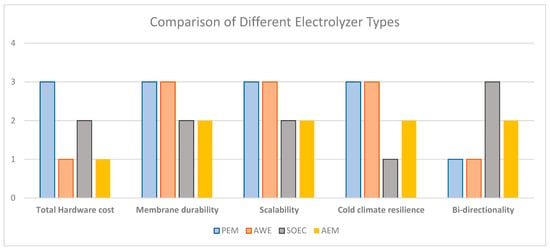

The bar chart in Figure 3 shows how different innovation areas in electrolyzer technologies correspond to Canada’s clean energy priorities. A simple logic is used, where 3 means high, 2, medium, and 1, low relevance, respectively. The ratings are derived from findings and insights in the literature [29,30,50,63,64,65,66,67].

Figure 3.

Mapping of innovation trends across electrolyzer technologies in relation to Canadian energy priorities.

In short, continued innovation along electrolyzer platforms, especially in areas such as durability, catalyst design, modularity, and grid-integration capability will be most critical in meeting the practical and strategic requirements of Canada’s hydrogen economy. As the global race for green hydrogen leadership is now on, Canada’s resource advantage and diverse climate challenges offer an ideal test bed for next-generation electrolyzer technologies.

5. Challenges and Future Directions

While electrolyzer technologies are evolving at a rapid rate, several technical, economic, and integration challenges still remain to prevent their widespread deployment and commercial scale-up. It is important to address these challenges to realize the full promise of green hydrogen, in Canada and globally. This section outlines the primary challenges associated with each primary electrolyzer technology and discusses principal directions for additional research, development, and policy support particularly in the Canadian context.

5.1. Technical Challenges

Despite major progress in design, materials, and system integration, technical limitations persist across all four electrolyzer types:

5.1.1. Durability and Longevity

Long-term durability represents a significant challenge, particularly to SOEC and AEM systems. AEM, while cost and modularity promising, still suffer from membrane degradation under dynamic cycling conditions and high voltages [23]. SOEC systems, on the other hand, suffer from thermal cycling fatigue, material embrittlement, and slow start-up times due to high-temperature operations [19]. Furthermore, recent comprehensive reviews indicate that engineering carbon-supported platinum nanostructures is a critical strategy for overcoming the sluggish kinetics and stability challenges inherent to the alkaline hydrogen evolution reaction [68].

5.1.2. Membrane and Electrolyte Stability

In both PEM and AEM systems, membrane degradation due to chemical, mechanical, or thermal stress remains a fundamental limitation to system lifetime extension [69]. Maintaining high ionic conductivity without sacrificing mechanical stability remains a materials science challenge.

5.1.3. Limited Commercial Scale-Up

While PEM and AWE technologies are commercially proven at multi-megawatt scales, SOEC and AEM are largely at pilot or demonstration scales [20,21,24]. Scaling from laboratory prototypes to full systems requires validated supply chains, long-term component lifetimes, and field-demonstrated reliability data elements that are still maturing on new platforms.

5.2. Economic Challenges

Electrolyzers are capital-intensive technologies, and cost remains a key constraint to market penetration:

5.2.1. High CAPEX and OPEX

PEM systems, while technically mature and renewable-compatible, require high-cost materials such as iridium and platinum, and operate at high current densities that can increase degradation rates [52]. Also, the cost of the titanium-based hardware, which includes the PTLs, flow fields, and bipolar plates, significantly increases stack and system CAPEX. These materials are required to ensure corrosion resistance but contribute heavily to overall system cost [59]. SOEC systems require complex thermal management hardware, which adds to installation and maintenance costs [20].

5.2.2. Materials Cost and Supply Risk

The reliance on imported or scarce materials for catalysts and membranes is a long-term concern for economic sustainability and supply chain security. The advancement of non-precious metal alternatives is therefore not only a technical but also a strategic economic imperative [70].

5.2.3. Infrastructure and Deployment Gaps

Canada, while rich in renewable energy, lacks widespread hydrogen distribution and storage infrastructure as yet. This adds to the installed cost of electrolyzer projects, especially in remote or export-oriented applications. Project proponents also have to deal with long permitting schedules and offtake market uncertainty in the future [1].

5.3. Integration Challenges

Successfully integrating electrolyzers into modern energy systems requires more than just technical compatibility:

5.3.1. Intermittency of Renewable Inputs

Electrolyzers, particularly AWE and SOEC systems, are constrained in terms of power variations. Fast change in their input power, due to solar or wind variability, can lower stack efficiencies and shorten component lifetimes unless systems are specially designed for dynamic load-following [53], as in PEM and certain emerging AEM systems.

5.3.2. System Control and Energy Management

Smart control systems and power electronics are needed to dynamically alter operating conditions, especially if electrolyzers are part of a Hybrid Energy Storage System (HESS) or support high penetration of renewables in remote communities. Real-time optimization algorithms are still evolving and need to be integrated into electrolyzer system design [51].

5.3.3. Hydrogen Storage and Utilization

Without appropriate storage capacity (e.g., pressurized tanks, underground caverns) or point demand for hydrogen, electrolyzer plants are subject to underutilization [50]. Canada’s extensive geography and dispersed population make centralized storage and distribution of hydrogen logistically demanding, particularly for rural locations.

5.4. Future Directions

To surmount these barriers and enable large-scale roll-out, a coordinated approach of research, demonstration, and policy is necessary. Canada, with its clean energy infrastructure, emerging hydrogen ecosystem, and strategic trading partnerships, is well-positioned to lead in the following areas:

5.4.1. Advanced R&D in Membranes and Catalysts

Canadian start-ups, research institutions, and universities can take a leading role in the innovation of alkaline-stable membranes, earth-abundant catalysts, and low-cost ionomers to make system costs lower and reliability higher [53]. Innovation in electrolyzer components should be the focus of federal research funding programs.

5.4.2. Demonstration of AEM and Bi-Directional Systems at Scale

As PEM and AWE technologies establish commercial traction, pilot-scale demonstrations for AEM and bi-directional (electrolyzer-fuel cell hybrid) systems are necessary to validate their performance under actual Canadian conditions like cold weather, remote microgrids, and hybrid energy systems [53]. Government-funded testbeds can accelerate this.

5.4.3. Policy Support for Domestic Manufacturing and Export Markets

Developing a competitive domestic supply chain for electrolyzer stacks, balance-of-plant components, and advanced materials will reduce reliance on imports and position Canada as a technology exporter. Incentives such as investment tax credits, hydrogen purchase agreements, and green industrial policy can catalyze both domestic demand as well as global cooperation [47].

5.4.4. Integration with Grid and Energy Market Design

Electrolyzers must be not just hydrogen production equipment but also versatile grid assets. Their ability to absorb excess renewable energy and provide ancillary services (e.g., frequency regulation, demand response) can be the key to new revenue streams [30]. Grid codes and energy market regulations must evolve to enable such integration.

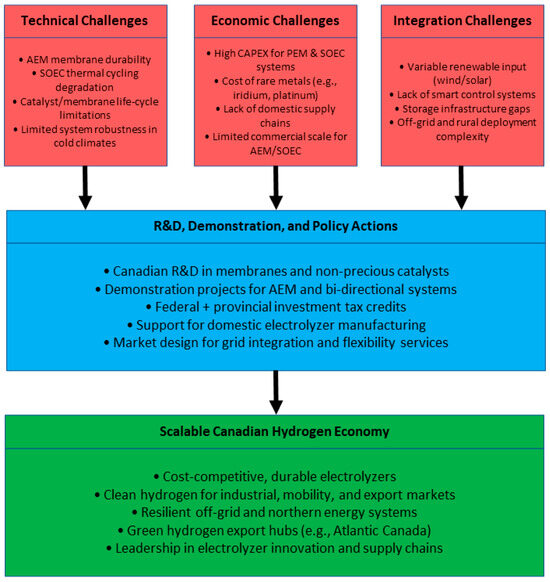

The summary of this section, shown in Figure 4, is a strategic roadmap that integrates Section 5.1, Section 5.2, Section 5.3 and Section 5.4, bringing together the key technical, economic, and integration challenges of electrolyzer deployment in Canada. It highlights the sequenced function of research and development, demonstration projects, and policy initiatives, each of which is essential to facilitating a scalable and resilient Canadian hydrogen economy.

Figure 4.

Strategic roadmap for advancing electrolyzer technologies in Canada.

Overall, while there are economic and technical challenges, the policy momentum, innovation potential, and strategic fit of Canada’s natural endowments provide a good starting point for widespread electrolyzer deployment. Focused investment in cost reduction, durability, system integration, and export readiness will be key to building a secure, low-carbon hydrogen economy that can compete globally and play a supportive role in national decarbonization goals.

6. Conclusions

Hydrogen electrolyzers are at the core of moving towards clean energy worldwide by producing green hydrogen from renewable electricity as a key decarbonization technology for industries difficult to electrify directly. The present work presented a comparative overview of the four dominant electrolyzer technologies of Alkaline (AWE), Proton Exchange Membrane (PEM), Solid Oxide (SOEC), and Anion Exchange Membrane (AEM), analyzing their operating principles, system-level behavior, innovation trends, and suitability for various deployment scenarios. Special note was given to Canada’s growing hydrogen horizon, highlighting the country’s bountiful renewable resources, policy-supportive environments, and budding leadership in electrolyzer manufacturing, research, and scaled demonstration projects. Despite ongoing durability, cost, and system integration problems with variable renewable inputs, targeted R&D, modular system innovation, and strategic policy support provide clear paths for surmounting these challenges. With the right investment and alignment, Canada is poised to lead next-generation electrolyzer technologies and be a global leader in clean hydrogen production and export.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.I., L.A.C.L. and Y.P.; methodology, S.I. and L.A.C.L.; software, S.I.; validation, S.I. and L.A.C.L.; formal analysis, S.I.; investigation, S.I.; resources, S.I.; data curation, S.I.; writing—original draft preparation, S.I.; writing—review and editing, Y.P. and L.A.C.L.; visualization, S.I.; supervision, L.A.C.L.; project administration, Y.P. and L.A.C.L.; funding acquisition, Y.P. and L.A.C.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by MITACS under project number IT41666, titled “Hydrogen Production and Utilization for Increasing Renewable Energy Penetration in Cold Climates.” Furthermore, it was also supported by RQEI under the project title “Optimisation de la production de l’H2 vert à partir des sources d’énergie variables et son utilisation en climat froid”.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Yanick Paquet was employed by Applied Research Centre, NERGICA. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AWE | Alkaline Water Electrolyzer |

| PEM | Proton Exchange Membrane |

| SOEC | Solid Oxide Electrolyzer Cell |

| AEM | Anion Exchange Membrane |

| KOH | Potassium Hydroxide |

| NaOH | Sodium Hydroxide |

| OH− | Hydroxide Ion |

| H+ | Proton |

| H2 | Hydrogen |

| O2 | Oxygen |

| CO2 | Carbon Dioxide |

| YSZ | Yttria-Stabilized Zirconia |

| CAPEX | Capital Expenditure |

| OPEX | Operating Expenditure |

| LHV | Lower Heating Value |

| MW | Megawatt |

| GW | Gigawatt |

| kW | Kilowatt |

| FCEV | Fuel Cell Electric Vehicle |

| URFC | Unitized Regenerative Fuel Cell |

| HESS | Hybrid Energy Storage System |

| GHG | Greenhouse Gas |

| VCR | Varennes Carbon Recycling |

| PEI | Prince Edward Island |

| QC | Quebec |

References

- Global Hydrogen Review 2023. 2023. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/global-hydrogen-review-2023 (accessed on 17 December 2025).

- Megía, P.J.; Vizcaíno, A.J.; Calles, J.A.; Carrero, A. Hydrogen Production Technologies: From Fossil Fuels toward Renewable Sources. A Mini Review. Energy Fuels 2021, 35, 16403–16415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuluhong, A.; Chang, Q.; Xie, L.; Xu, Z.; Song, T. Current Status of Green Hydrogen Production Technology: A Review. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehlers, J.C.; Feidenhans’l, A.A.; Therkildsen, K.T.; Larrazábal, G.O. Affordable Green Hydrogen from Alkaline Water Electrolysis: Key Research Needs from an Industrial Perspective. ACS Energy Lett. 2023, 8, 1502–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, A. Green Hydrogen and the Energy Transition: Hopes, Challenges, and Realistic Opportunities. Hydrogen 2025, 6, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Pang, Y.; Xu, H.; Martinez, A.; Chen, K.S. PEM Fuel cell and electrolysis cell technologies and hydrogen infrastructure development—A review. Energy Environ. Sci. 2022, 15, 2288–2328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zen and the Art of Clean Energy Solutions (Zen) on behalf of the Government of Canada. Hydrogen Strategy for Canada. Available online: https://natural-resources.canada.ca/sites/nrcan/files/environment/hydrogen/NRCan_Hydrogen-Strategy-Canada-na-en-v3.pdf (accessed on 17 December 2025).

- Şahin, M.E. An Overview of Different Water Electrolyzer Types for Hydrogen Production. Energies 2024, 17, 4944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, A.L.; Balakrishnan, S.; Hodges, A.; Tsekouras, G.; Al-Musawi, A.; Wagner, K.; Lee, C.Y.; Swiegers, G.F.; Wallace, G.G. High-performing catalysts for energy-efficient commercial alkaline water electrolysis. Sustain. Energy Fuels 2023, 7, 31–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, L.; Nakashima, R.N.; Comodi, G.; Frandsen, H.L. Alkaline electrolysis for green hydrogen production: A novel, simple model for thermo-electrochemical coupled system analysis. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2025, 262, 125154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Cheng, H.; He, H.; Wei, W. Efficiency and consistency enhancement for alkaline electrolyzers driven by renewable energy sources. Commun. Eng. 2023, 2, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayed-Ahmed, H.; Toldy, Á.I.; Santasalo-Aarnio, A. Dynamic operation of proton exchange membrane electrolyzers—Critical review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2024, 189, 113883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karthikeyan, B.; Kumar, G.P.; Basa, S.; Sinha, S.; Tyagi, S.; Kamat, P.; Prabakaran, R.; Kim, S.C. Strategic optimization of large-scale solar PV parks with PEM Electrolyzer-based hydrogen production, storage, and transportation to minimize hydrogen delivery costs to cities. Appl. Energy 2025, 377, 124758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clapp, M.; Zalitis, C.M.; Ryan, M. Perspectives on current and future iridium demand and iridium oxide catalysts for PEM water electrolysis. Catal. Today 2023, 420, 114140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallnöfer-Ogris, E.; Grimmer, I.; Ranz, M.; Höglinger, M.; Kartusch, S.; Rauh, J.; Macherhammer, M.G.; Grabner, B.; Trattner, A. A review on understanding and identifying degradation mechanisms in PEM water electrolysis cells: Insights for stack application, development, and research. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 65, 381–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, H.; Murawski, J.; Shinde, D.V.; Stephens, I.E.L.; Hinds, G.; Smith, G. Impact of impurities on water electrolysis: A review. Sustain. Energy Fuels 2023, 7, 1565–1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, J.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, Y.; Alodhayb, A.; Sun, Y.; Bu, Y. Advances and challenges in symmetrical solid oxide electrolysis cells: Materials development and resource utilization. Mater. Chem. Front. 2023, 7, 3904–3921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolaoso, L.A.; Duan, C.; Kazempoor, P. Life cycle analysis of a hydrogen production system based on solid oxide electrolysis cells integrated with different energy and wastewater sources. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 52, 485–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.; Singh, K.; Bhunia, H. Recent advances in high temperature solid oxide electrolysis cell for hydrogen production. Indian Chem. Eng. 2025, 67, 31–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prosser, J.H.; James, B.D.; Murphy, B.M.; Wendt, D.S.; Casteel, M.J.; Westover, T.L.; Knighton, L.T. Cost analysis of hydrogen production by high-temperature solid oxide electrolysis. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 49, 207–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flis, G.; Wakim, G. Solid Oxide Electrolysis: A Technology Status Assessment. 2023. Available online: https://cdn.catf.us/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/15092028/solid-oxide-electrolysis-report.pdf (accessed on 17 December 2025).

- Ding, G.; Lee, H.; Li, Z.; Du, J.; Wang, L.; Chen, D.; Sun, L. Highly Efficient and Durable Anion Exchange Membrane Water Electrolyzer Enabled by a Fe–Ni3 S2 Anode Catalyst. Adv. Energy Sustain. Res. 2023, 4, 2200130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Ma, H.; Khan, M.; Hsiao, B.S. Recent Advances and Challenges in Anion Exchange Membranes Development/Application for Water Electrolysis: A Review. Membranes 2024, 14, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, N.U. Durability Enhancement of Anion Exchange Membrane Based Fuel Cells (AEMFCS) And Water Electrolyzers (AEMELs) By Understanding Degradation Mechanisms. Ph.D. Thesis, University of South Carolina, Columbia, SC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Muhyuddin, M.; Santoro, C.; Osmieri, L.; Ficca, V.C.; Friedman, A.; Yassin, K.; Pagot, G.; Negro, E.; Konovalova, A.; Lindquist, G.; et al. Anion-Exchange-Membrane Electrolysis with Alkali-Free Water Feed. Chem. Rev. 2025, 125, 6906–6976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.Y.; Mastropasqua, L.; Saeedmanesh, A.; Brouwer, J. Sustained long-term efficiency in solid oxide electrolysis systems through innovative reversible electrochemical heat management. Energy Convers. Manag. 2024, 308, 118405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadiq, M.; Alshehhi, R.J.; Urs, R.R.; Mayyas, A.T. Techno-economic analysis of Green-H2@Scale production. Renew. Energy 2023, 219, 119362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernat, R.; Milewski, J.; Dybinski, O.; Martsinchyk, A.; Shuhayeu, P. Review of AEM Electrolysis Research from the Perspective of Developing a Reliable Model. Energies 2024, 17, 5030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Shafie, M. Hydrogen production by water electrolysis technologies: A review. Results Eng. 2023, 20, 101426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cozzolino, R.; Bella, G. A review of electrolyzer-based systems providing grid ancillary services: Current status, market, challenges and future directions. Front. Energy Res. 2024, 12, 1358333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canada 2022. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/canada-2022 (accessed on 30 May 2025).

- Okunlola, A.; Giwa, T.; Di Lullo, G.; Davis, M.; Gemechu, E.; Kumar, A. Techno-economic assessment of low-carbon hydrogen export from Western Canada to Eastern Canada, the USA, the Asia-Pacific, and Europe. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 6453–6477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberta Hydrogen Roadmap. Available online: https://open.alberta.ca/publications/alberta-hydrogen-roadmap (accessed on 6 June 2025).

- Implementation. Available online: https://www.quebec.ca/en/government/policies-orientations/plan-green-economy/implementation (accessed on 6 June 2025).

- Product. Available online: https://www.hydrogenoptimized.com/product/ (accessed on 30 May 2025).

- Applications. Available online: https://nexthydrogen.com/solutions/applications/ (accessed on 29 May 2025).

- Hyundai motor and Kia Collaborate with Next Hydrogen to Develop Advanced Alkaline Water Electrolysis System 0000000501. Available online: https://www.hyundai.com/worldwide/en/newsroom/detail/hyundai-motor-and-kia-collaborate-with-next-hydrogen-to-develop-advanced-alkaline-water-electrolysis-system-0000000501 (accessed on 29 May 2025).

- AKA with Re-Fuel Orders Two 1 Megawatt Electrolyzers from Enapter. Available online: https://www.aka-group.com/aka-with-re-fuel-orders-two-1-megawatt-electrolyzers-from-enapter/ (accessed on 29 May 2025).

- Air Liquide Commissions 20-MW Pem Electrolyser in Canada 729422. Available online: https://renewablesnow.com/news/air-liquide-commissions-20-mw-pem-electrolyser-in-canada-729422/ (accessed on 29 May 2025).

- HTEC Opens Its Sixth Station Strengthening British Columbias Light-Duty Hydrogen Refueling Network. Available online: https://www.htec.ca/htec-opens-its-sixth-station-strengthening-british-columbias-light-duty-hydrogen-refueling-network/ (accessed on 30 May 2025).

- First Green Hydrogen Project Becomes Reality: Thyssenkrupp to Install 88 Megawatt Water Electrolysis Plant for Hydro-Quebec in Canada 93778. Available online: https://www.thyssenkrupp.com/en/newsroom/press-releases/pressdetailpage/first-green-hydrogen-project-becomes-reality--thyssenkrupp-to-install-88-megawatt-water-electrolysis-plant-for-hydro-quebec-in-canada-93778 (accessed on 5 June 2025).

- Varennes. Available online: https://enerkem.com/projects/varennes (accessed on 5 June 2025).

- About. Available online: https://worldenergygh2.com/about/ (accessed on 5 June 2025).

- Everwind Fuels Supports Nova Scotia s Offshore Wind Roadmap 871342954. Available online: https://www.newswire.ca/news-releases/everwind-fuels-supports-nova-scotia-s-offshore-wind-roadmap-871342954.html (accessed on 5 June 2025).

- Harnessing Wind Power for Ammonia on Canadas Atlantic Coast. Available online: https://ammoniaenergy.org/articles/harnessing-wind-power-for-ammonia-on-canadas-atlantic-coast/ (accessed on 5 June 2025).

- Overview Ontario. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/services/environment/weather/climatechange/climate-plan/clean-electricity/overview-ontario.html (accessed on 29 May 2025).

- Hydrogen: A Viable Option for a Net-Zero Canada in 2050? Available online: https://sencanada.ca/content/sen/committee/441/ENEV/reports/Hydrogen-energy-report_e_Final_WEB.pdf (accessed on 17 December 2025).

- 2022PREM0018-000464. Available online: https://news.gov.bc.ca/releases/2022PREM0018-000464 (accessed on 5 June 2025).

- Gul, E.; Baldinelli, G.; Farooqui, A.; Bartocci, P.; Shamim, T. AEM-electrolyzer based hydrogen integrated renewable energy system optimisation model for distributed communities. Energy Convers. Manag. 2023, 285, 117025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łosiewicz, B. Technology for Green Hydrogen Production: Desk Analysis. Energies 2024, 17, 4514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, A.; Abdel-Rahim, O.; Bajaj, M.; Zaitsev, I. Power electronics for green hydrogen generation with focus on methods, topologies, and comparative analysis. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 24767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Technical Targets Proton Exchange Membrane Electrolysis. Available online: https://www.energy.gov/eere/fuelcells/technical-targets-proton-exchange-membrane-electrolysis (accessed on 29 May 2025).

- Wu, Y.; Xu, G.; Zhou, J.; Cao, D. Research progress of the porous membranes in alkaline water electrolysis for green hydrogen production. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 505, 159291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmo, M.; Fritz, D.L.; Mergel, J.; Stolten, D. A comprehensive review on PEM water electrolysis. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2013, 38, 4901–4934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Zhao, Y.; Ke, L.; Wu, X.; Zhao, K.; Li, L.; Cao, X.; Jiang, X.; Yang, Y.; Rothenberg, G.; et al. A reversible alkaline water electrolyser for load-flexible power–H2 interconversion enabled by bifunctional catalyst. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2025, 12, nwaf325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laguna-Bercero, M.A. Recent advances in high temperature electrolysis using solid oxide fuel cells: A review. J. Power Sources 2012, 203, 4–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, Y.J.; Mirshekari, G.; Raaijman, S.J.; Corbett, P.J. Technology Landscape of Anion Exchange Membrane Water Electrolyzers: Where Are We Today? ACS Energy Lett. 2025, 10, 3058–3063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loh, A.; Li, X.; Taiwo, O.O.; Tariq, F.; Brandon, N.P.; Wang, P.; Xu, K.; Wang, B. Development of Ni–Fe based ternary metal hydroxides as highly efficient oxygen evolution catalysts in AEM water electrolysis for hydrogen production. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2020, 45, 24232–24247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badgett, A.; Brauch, J.; Thatte, A.; Rubin, R.; Skangos, C.; Wang, X.; Ahluwalia, R.; Pivovar, B.; Ruth, M. Updated Manufactured Cost Analysis for Proton Exchange Membrane Water Electrolyzers. NREL/TP--6A20-87625, 2311140, MainId:88400. 2024. Available online: https://www.osti.gov/servlets/purl/2311140/ (accessed on 5 December 2025).

- Enapter_Brochure_AEM-MC_EN. Available online: https://handbook.enapter.com/assets/Enapter_Brochure_EN.pdf (accessed on 17 December 2025).

- Gabbasa, M.A.; Alahrish, A.S.; Emhamed, A.M. A Review of New Progress in Unitized Regenerative Fuel Cell System. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/375755513_A_review_of_new_progress_in_unitized_regenerative_fuel_cell_system (accessed on 17 December 2025).

- Peng, X.; Taie, Z.; Liu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Peng, X.; Regmi, Y.N.; Fornaciari, J.C.; Capuano, C.; Binny, D.; Kariuki, N.N.; et al. Hierarchical electrode design of highly efficient and stable unitized regenerative fuel cells (URFCs) for long-term energy storage. Energy Environ. Sci. 2020, 13, 4872–4881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Park, J.E.; Na, G.; Choi, C.; Cho, Y.-H.; Sung, Y.-E. Low-Cost and High-Performance Anion-Exchange Membrane Water Electrolysis Stack Using Non-Noble Metal-Based Materials. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2023, 6, 8738–8748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, D.T.; Tran, P.K.L.; Malhotra, D.; Nguyen, T.H.; Nguyen, T.T.A.; Duong, N.T.A.; Kim, N.H.; Lee, J.H. Current status of developed electrocatalysts for water splitting technologies: From experimental to industrial perspective. Nano Converg. 2025, 12, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, T.; Kim, S.-K. Non-precious hydrogen evolution reaction catalysts: Stepping forward to practical polymer electrolyte membrane-based zero-gap water electrolyzers. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 433, 133681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelico, R.; Giametta, F.; Bianchi, B.; Catalano, P. Green Hydrogen for Energy Transition: A Critical Perspective. Energies 2025, 18, 404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, H.F.; Gómez, J.A.; Santos, D.M.F. Proton-Exchange Membrane Electrolysis for Green Hydrogen Production: Fundamentals, Cost Breakdown, and Strategies to Minimize Platinum-Group Metal Content in Hydrogen Evolution Reaction Electrocatalysts. Catalysts 2024, 14, 845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Zeng, J.; Yang, G.; Sun, X.; Lin, X.; Liu, K.; Chen, J.; Wang, S.; Lu, X.F. Carbon-supported platinum-based electrocatalysts for alkaline hydrogen evolution. EES Catal. 2025, 3, 972–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henkensmeier, D.; Cho, W.C.; Jannasch, P.; Stojadinovic, J.; Li, Q.; Aili, D.; Jensen, J.O. Separators and Membranes for Advanced Alkaline Water Electrolysis. Chem. Rev. 2024, 124, 6393–6443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, D.; Maharana, S.; Panda, A.B. Bio-inspired nickel–iron-based organogel: An efficient and stable bifunctional electrocatalyst for overall water splitting at high current density. Nanoscale 2025, 17, 12880–12893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.