Synergistic Temperature–Pressure Optimization in PEM Water Electrolysis: A 3D CFD Analysis for Efficient Green Ammonia Production

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Simulation and Optimization of PEMWE Based on CFD Calculation

2.1. Three-Dimensional CFD Model of PEMWE

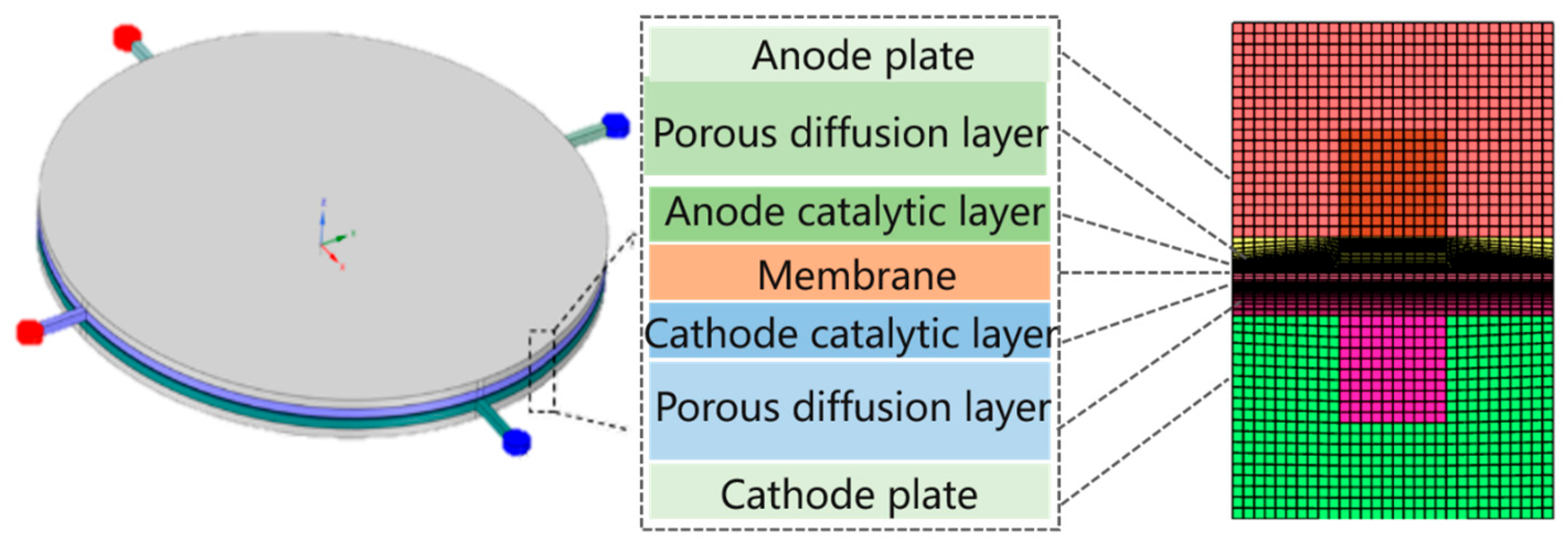

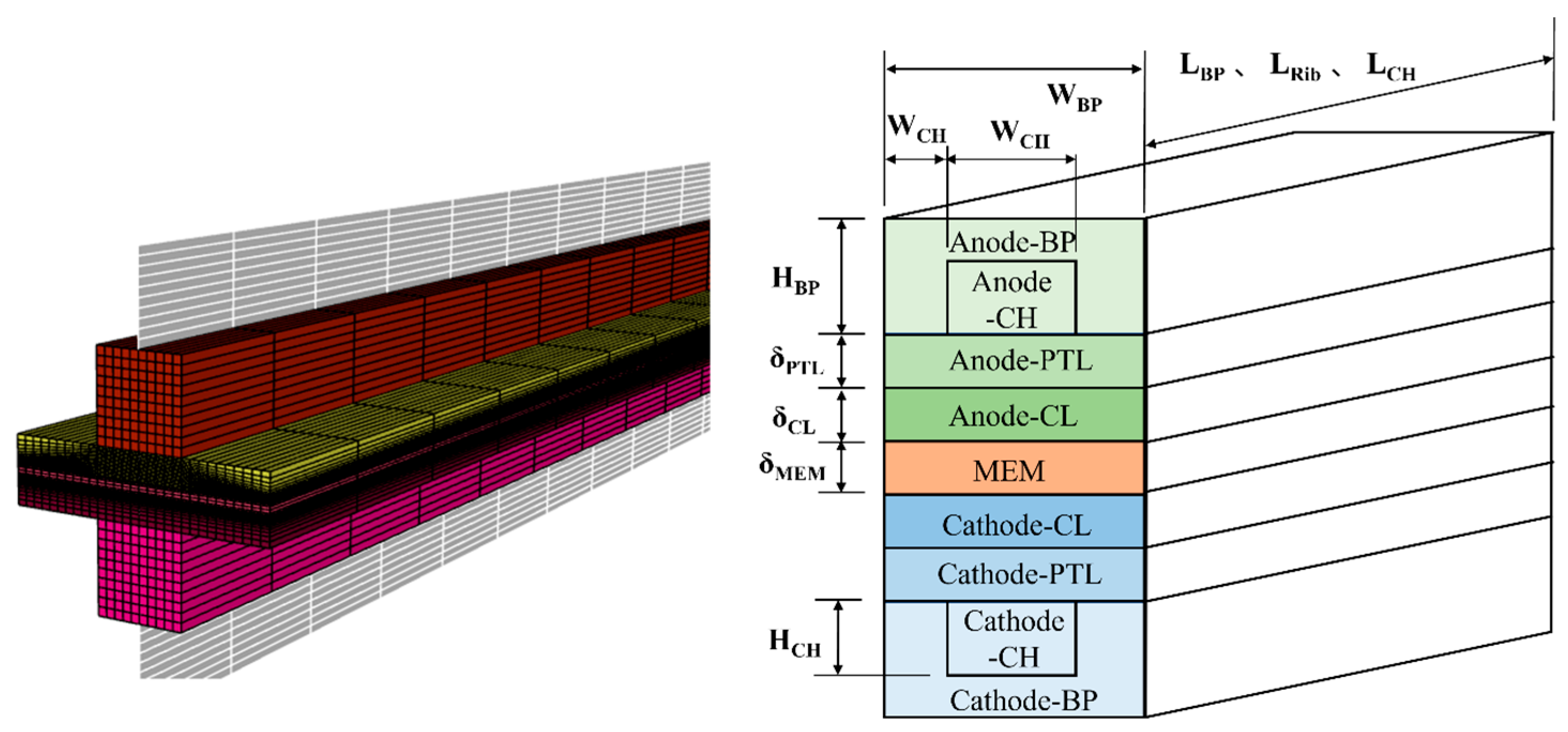

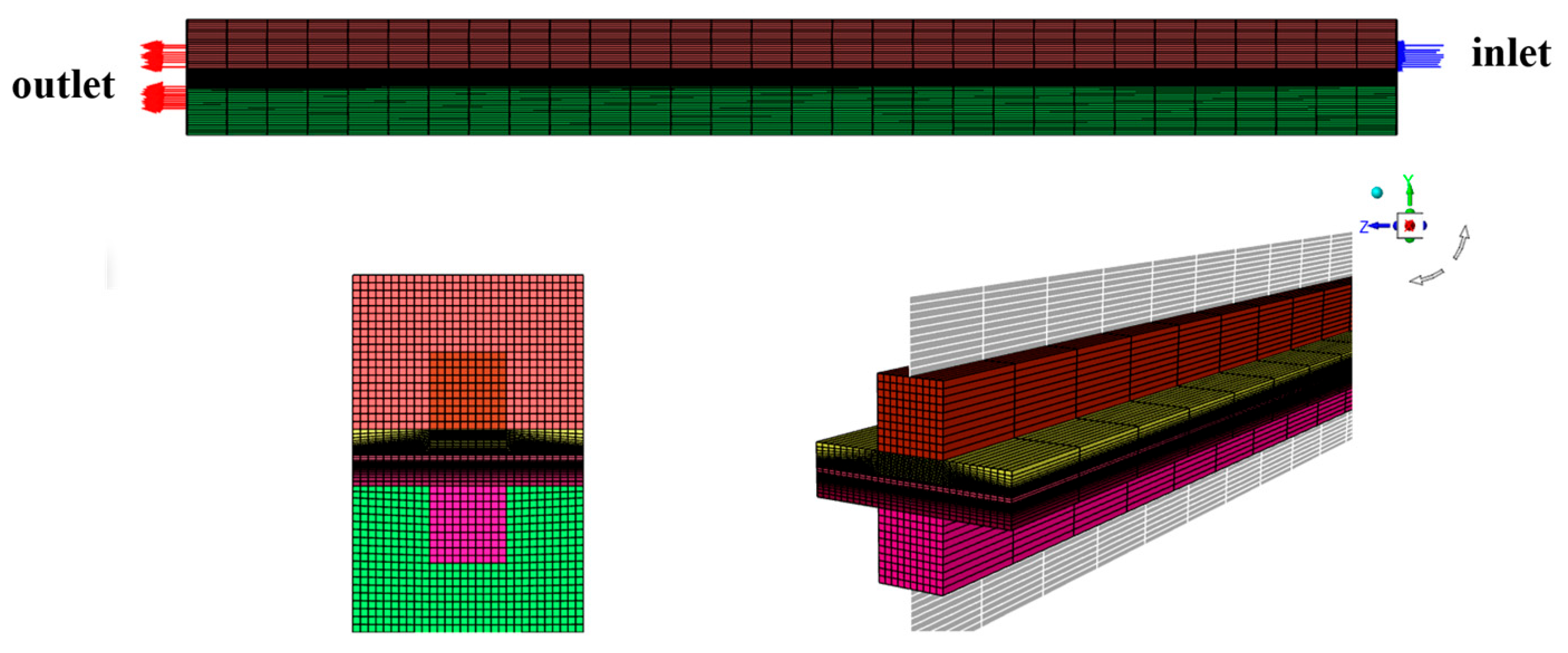

2.1.1. Geometric Mode

- (1)

- Steady-state operation with time-invariant variables;

- (2)

- Laminar flow regime dominated by viscous forces;

- (3)

- Negligible water evaporation in the anode due to liquid saturation;

- (4)

- Ideal gas behavior governed by the ideal gas law;

- (5)

- Homogenized porous transport layers (PTLs) characterized by macroscopic properties, such as porosity and permeability;

- (6)

- Fully hydrated membrane maintaining optimal proton conductivity;

- (7)

- Exclusive proton permeability through the membrane, preventing gas crossover and electrical shorting.

2.1.2. Numerical Mode

2.2. Model Validation

2.2.1. Grid Independence Verification

2.2.2. Verification of CFD Model with Experimental Data

3. Results and Discussion

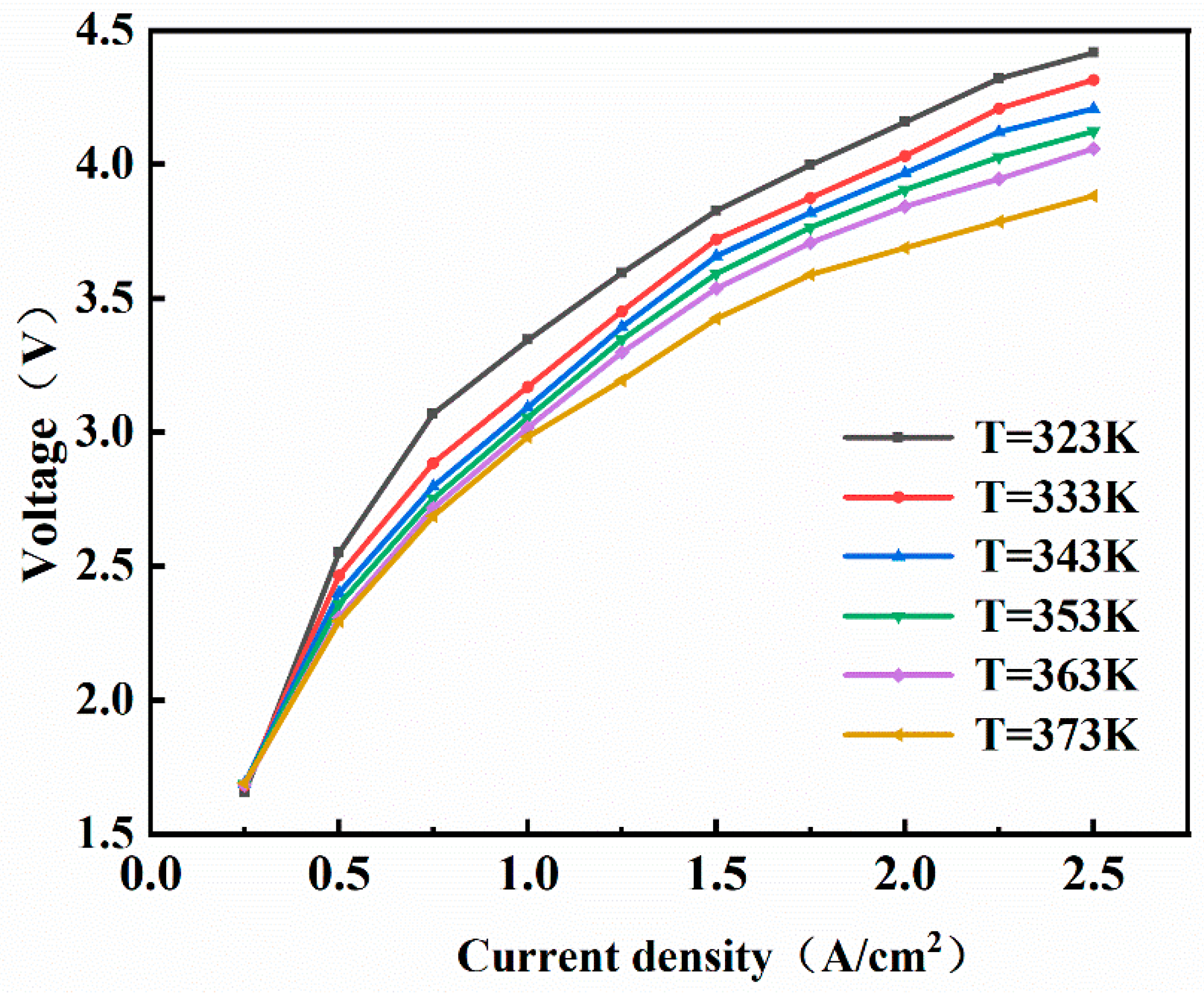

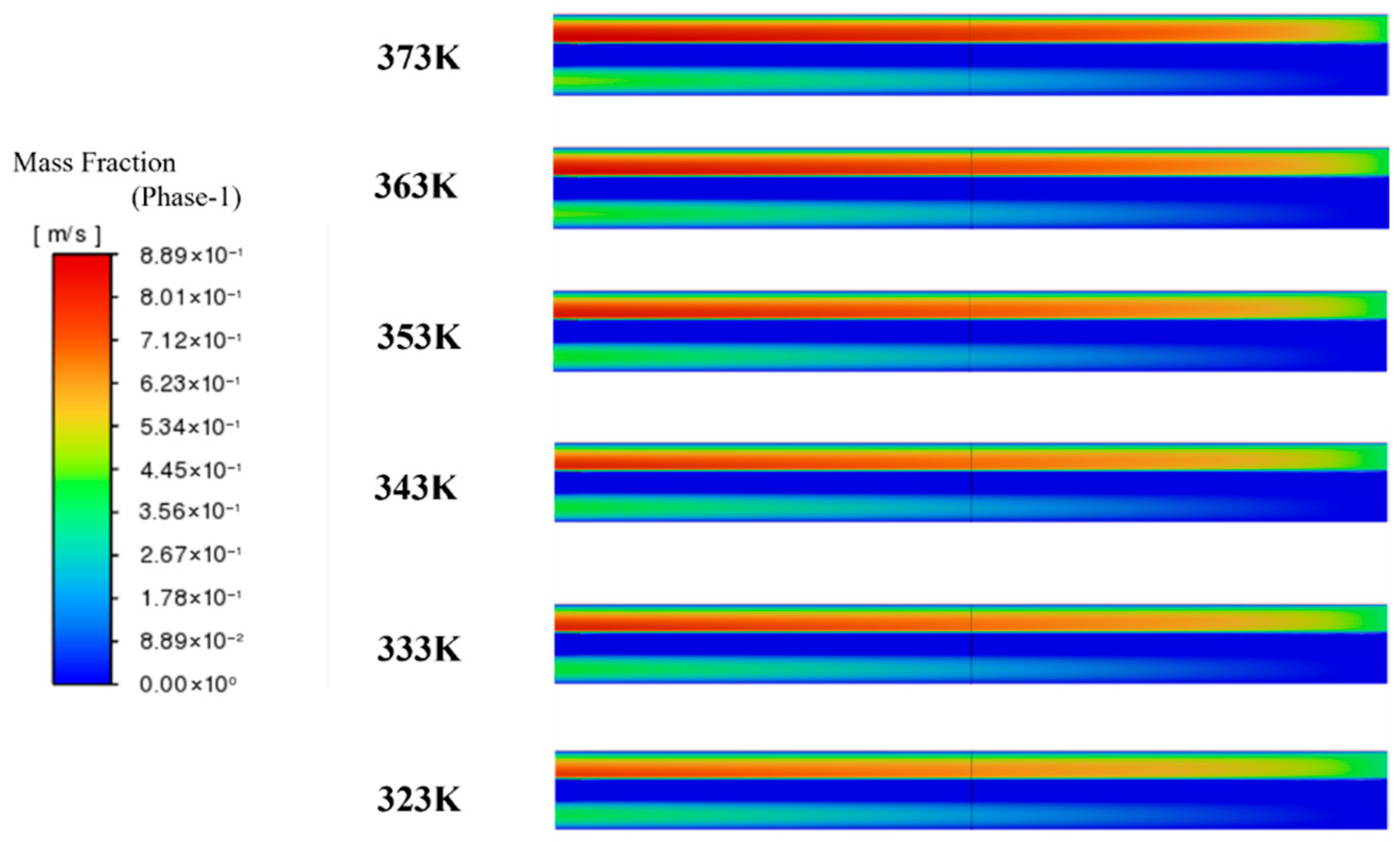

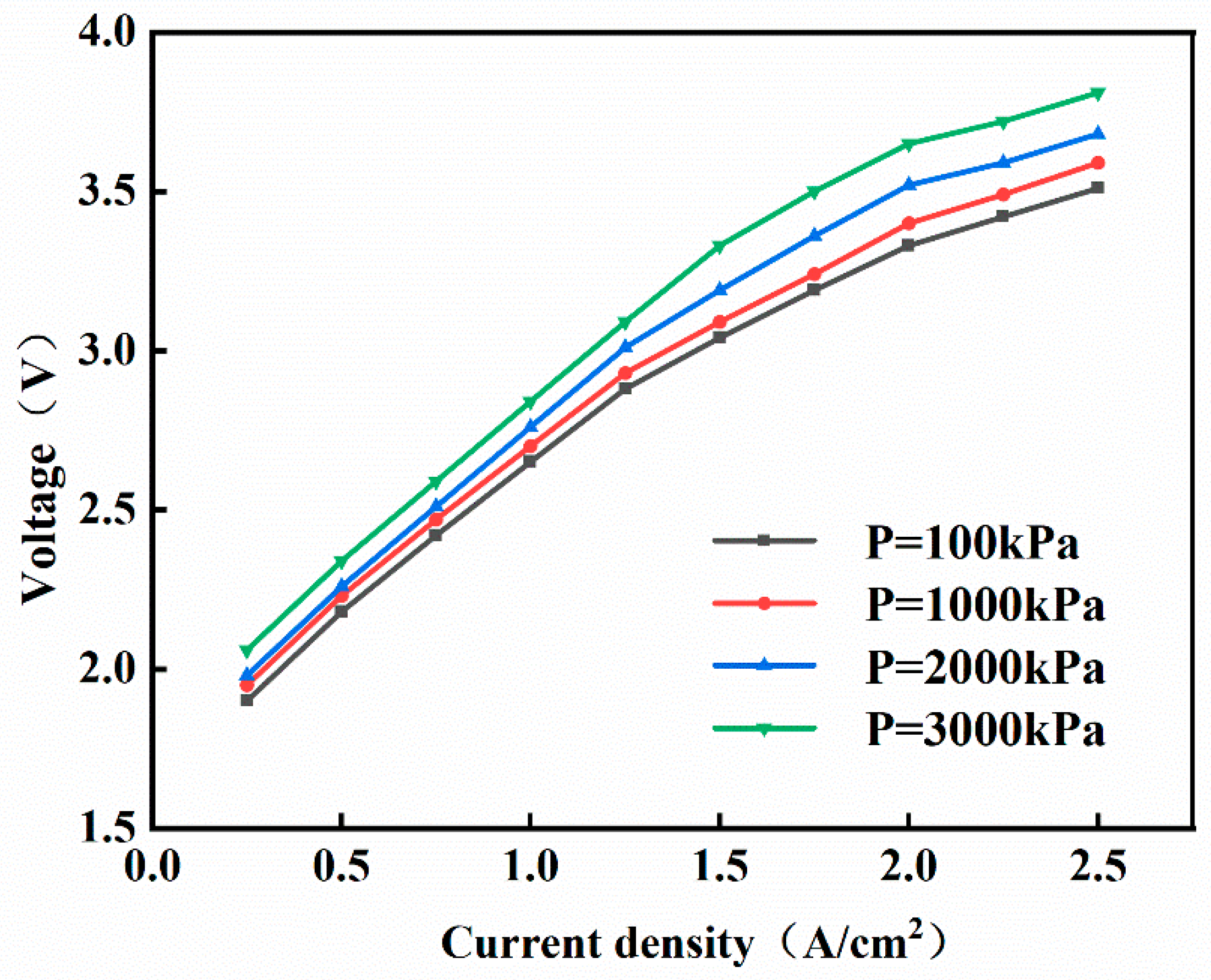

3.1. Influence of Operating Conditions

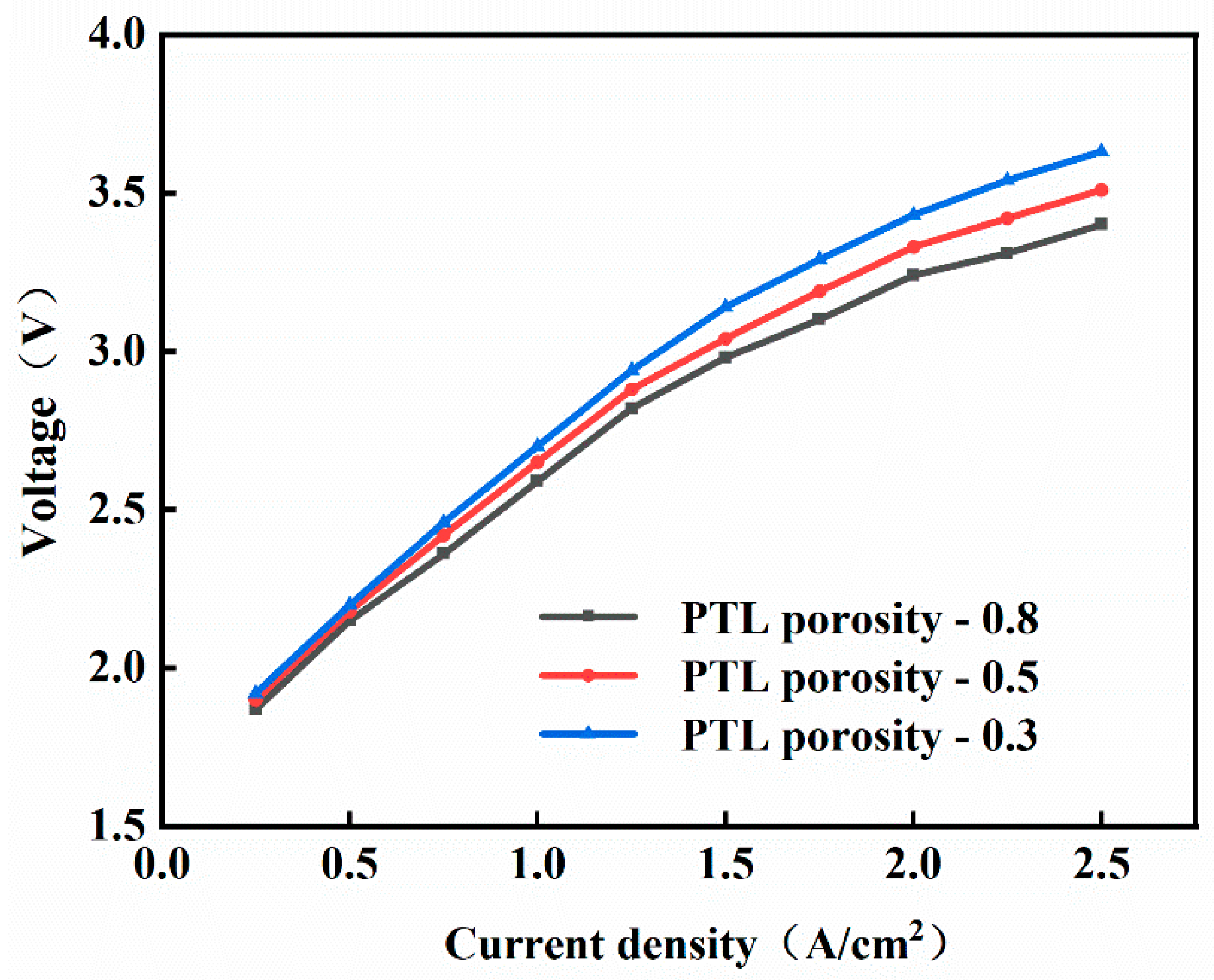

3.2. Influence of Equipment Component

3.3. Hydrogen Production Analysis and Efficiency Evaluation

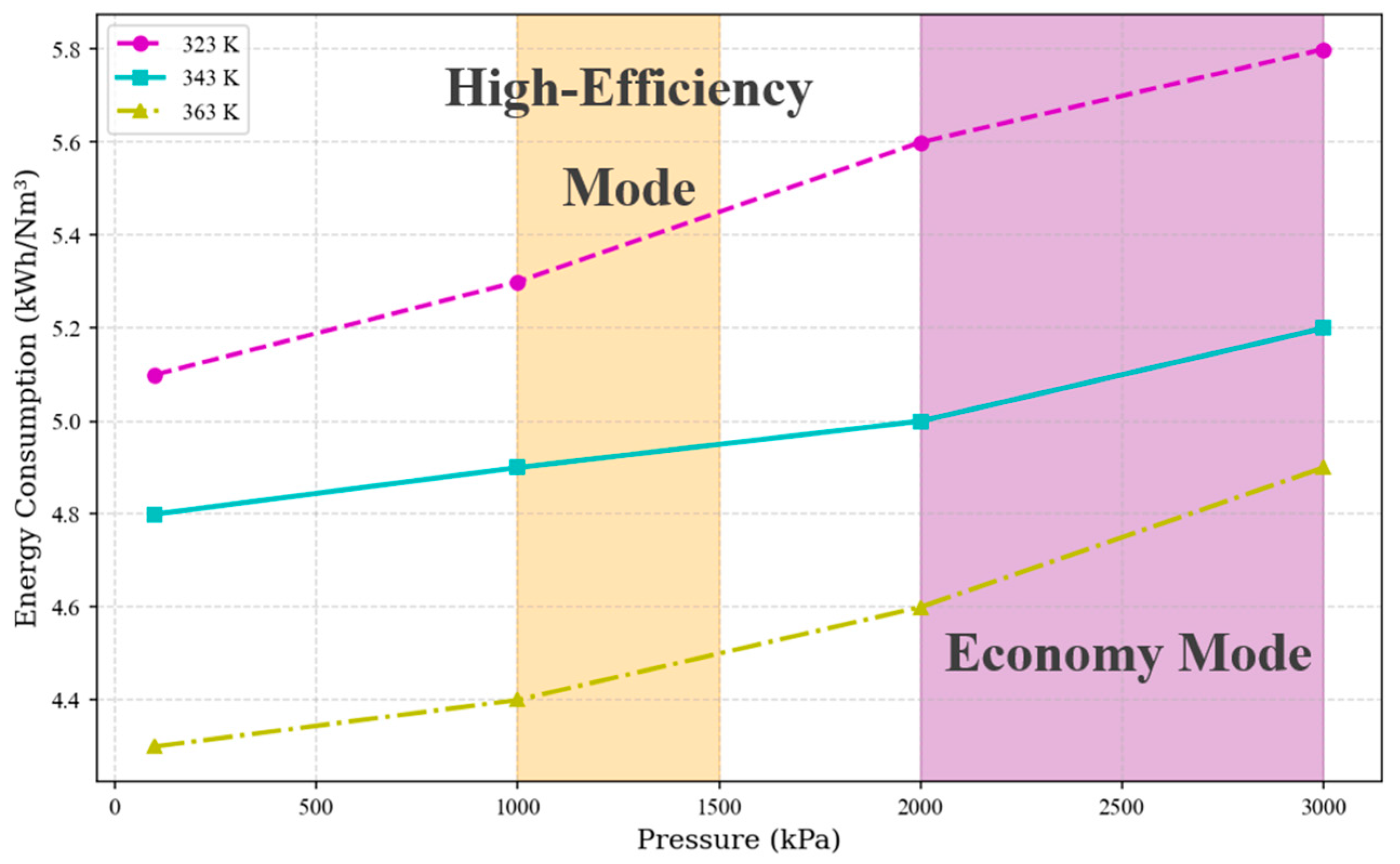

3.4. Operational Strategy Optimization

- (1)

- High-Efficiency Mode (Yellow): The temperature control range is 353–363 K, and the pressure control range is 1000–1500 kPa. The advantage of a high temperature lies in the exponential increase in membrane proton conductivity with temperature. When T = 363 K, the conductivity is 2.3 times higher than that at 323 K. The activation overpotential decreases with increasing temperature, and the Arrhenius equation indicates that for every 10 K temperature increase, the exchange current density increases by approximately 30%. According to Henry’s law, low pressure reduces gas solubility, minimizing bubble blockage at the flow channel and porous transport layer interface. The concentration polarization voltage decreases by 0.15–0.2 V. Furthermore, regarding integration with the overall green ammonia production system, a hydrogen output pressure of 1000 kPa allows for direct connection to medium-pressure storage tanks (10–15 bar), eliminating one compression stage and reducing compression energy consumption.

- (2)

- Economy Mode (Purple): The temperature control range is 333–343 K, and the pressure control range is 2000–3000 kPa. Reducing the temperature to 333–343 K slows the dehydration rate of the Nafion membrane, thereby extending its service life. High-pressure hydrogen can be fed directly into multi-stage compressors to raise the pressure to the levels required for green ammonia synthesis (15–25 MPa), reducing the number of compression stages and consequently lowering energy consumption, resulting in higher techno-economic feasibility.

4. Conclusions

- (1)

- A comprehensive assessment quantified the influence of temperature, pressure, membrane thickness, and PTL porosity on system performance. The optimal operating conditions were established to enhance hydrogen production efficiency and cost-effectiveness.

- (2)

- While performance improves with temperature, membrane stability constraints limit the optimal range to 353–363 K. Elevated cathode pressures increase voltage requirements; 1000–2000 kPa balances power demands with sealing integrity while enabling direct hydrogen storage.

- (3)

- When the current density is 2.5 A/cm2, increasing the thickness of the proton exchange membrane leads to an increase in the working voltage by approximately 0.4 V. The increase in the thickness of the proton exchange membrane reduces the performance of PEMEC; compared to the low-current-density region, at higher current densities, the porosity of PTL has a more significant impact on the working voltage. At a current density of 2.5 A/cm2, the working voltage increases by approximately 11.7 V, and the increase in the porosity of PTL reduces the performance of PEMEC; moreover, an insufficient water inlet rate significantly increases system energy consumption.

- (4)

- Through quantitative sensitivity analysis, it can be found that temperature is the most sensitive parameter, but due to the risk of membrane dehydration, Nafion proton exchange membranes are prone to brittleness when the temperature is greater than 363 K; there is great potential for optimizing the thickness of the PEM, but it is necessary to balance mechanical strength. In practical engineering applications, a composite reinforced membrane can be considered. The pressure sensitivity is relatively low, but operating at high pressure can reduce subsequent compression energy consumption.

- (5)

- Operational strategy analysis indicates that the high-efficiency mode (4.3–4.5 kWh/Nm3) is suitable for renewable energy consumption scenarios, while the economy mode (4.7 kWh/Nm3) reduces compression energy consumption by 23% through pressure–temperature synergistic optimization, achieving energy consumption alignment with green ammonia synthesis processes.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Xu, R.; Zhang, S.; Rong, F.; Fan, W.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Y.; Zan, L.; Ji, X.; He, G. Physics-Informed Neural Network Enhanced CFD Simulation of Two-Dimensional Green Ammonia Synthesis Reactor. Processes 2025, 13, 2457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Hu, C.; Ji, S.; Zhao, H.; Chen, J.; He, G. Generating comprehensive lithium battery charging data with generative AI. Appl. Energy 2025, 377, 124604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, G.; Dang, Y.; Zhou, L.; Dai, Y.; Que, Y.; Xu, J. Architecture model proposal of innovative intelligent manufacturing in the chemical industry based on multi-scale integration and key technologies. Comput. Chem. Eng. 2020, 141, 106967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Khadilkar, M.R.; Al-Dahhan, M.H.; Dudukovic, M.P. CFD of multiphase flow in packed-bed reactors: II. Results and applications. AIChE J. 2004, 48, 716–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barth, T.J.; Griebel, M.; Keyes, D.E.; Nieminen, R.M.; Roose, D.; Schlick, T. (Eds.) Uncertainty Quantification in Computational Fluid Dynamics; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; Volume 14, pp. 274–282. [Google Scholar]

- Chai, S.; Ren, Z.; Ji, S.; Zheng, X.; Zhou, L.; Zhang, L.; Ji, X. Exploring the Influence of Solvation on Multidimensional Particle Size Distribution Based on the Spiral Growth Model and the Lattice Boltzmann Method. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2024, 63, 20633–20650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saba, S.M.; Müller, M.; Robinius, M.; Stolten, D. The investment costs of electrolysis—A comparison of cost studies from the past 30 years. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2018, 43, 1209–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, M.; Lee, S.; Jung, S.; Choi, Y.; Moon, S.; Lim, H. Systematic assessment of the anode flow field hydrodynamics in a new circular PEM water electrolyser. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2020, 45, 20765–20775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olesen, A.C.; Rømer, C.; Kær, S.K. A numerical study of the gas-liquid, two-phase flow maldistribution in the anode of a high pressure PEM water electrolysis cell. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2016, 41, 52–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, J.; Chen, Y. Numerical modeling of three-dimensional two-phase gas–liquid flow in the flow field plate of a PEM electrolysis cell. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2010, 35, 3183–3197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, D.D.H.; Sasmito, A.P.; Shamim, T. Numerical Investigation of the High Temperature PEM Electrolyzer: Effect of Flow Channel Configurations. ECS Trans. 2013, 58, 99–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toghyani, S.; Afshari, E.; Baniasadi, E.; Atyabi, S.A. Thermal and electrochemical analysis of different flow field patterns in a PEM electrolyzer. Electrochim. Acta 2018, 267, 234–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inaba, M.; Kinumoto, T.; Kiriake, M.; Umebayashi, R.; Tasaka, A.; Ogumi, Z. Gas crossover and membrane degradation in polymer electrolyte fuel cells. Electrochim. Acta 2006, 51, 5746–5753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigoriev, S.A.; Millet, P.; Korobtsev, S.V.; Porembskiy, V.I.; Pepic, M.; Etievant, C.; Puyenchet, C.; Fateev, V.N. Hydrogen safety aspects related to high-pressure polymer electrolyte membrane water electrolysis. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2009, 34, 5986–5991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olesen, A.C.; Frensch, S.H.; Kær, S.K. Towards uniformly distributed heat, mass and charge: A flow field design study for high pressure and high current density operation of PEM electrolysis cells. Electrochim. Acta 2019, 293, 476–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigoriev, S.A.; Kalinnikov, A.A.; Millet, P.; Porembsky, V.I.; Fateev, V.N. Mathematical modeling of high-pressure PEM water electrolysis. J. Appl. Electrochem. 2009, 40, 921–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afshari, E.; Khodabakhsh, S.; Jahantigh, N.; Toghyani, S. Performance assessment of gas crossover phenomenon and water transport mechanism in high pressure PEM electrolyzer. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 11029–11040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toghyani, S.; Baniasadi, E.; Afshari, E.; Javani, N. Performance analysis and exergoeconomic assessment of a proton exchange membrane compressor for electrochemical hydrogen storage. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2020, 45, 34993–35005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toghyani, S.; Afshari, E.; Baniasadi, E. Parametric study of a proton exchange membrane compressor for electrochemical hydrogen storage using numerical assessment. J. Energy Storage 2020, 30, 101469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikiforov, A.V.; Tomás García, A.L.; Petrushina, I.M.; Christensen, E.; Bjerrum, N.J. Preparation and study of IrO2/SiC–Si supported anode catalyst for high temperature PEM steam electrolysers. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2011, 36, 5797–5805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, M.K.; Aili, D.; Christensen, E.; Pan, C.; Eriksen, S.; Jensen, J.O.; von Barner, J.H.; Li, Q.; Bjerrum, N.J. PEM steam electrolysis at 130 °C using a phosphoric acid doped short side chain PFSA membrane. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2012, 37, 10992–11000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandesris, M.; Médeau, V.; Guillet, N.; Chelghoum, S.; Thoby, D.; Fouda-Onana, F. Membrane degradation in PEM water electrolyzer: Numerical modeling and experimental evidence of the influence of temperature and current density. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2015, 40, 1353–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toghyani, S.; Afshari, E.; Baniasadi, E.; Atyabi, S.A.; Naterer, G.F. Thermal and electrochemical performance assessment of a high temperature PEM electrolyzer. Energy 2018, 152, 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toghyani, S.; Baniasadi, E.; Afshari, E. Numerical simulation and exergoeconomic analysis of a high temperature polymer exchange membrane electrolyzer. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2019, 44, 31731–31744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debe, M.K.; Hendricks, S.M.; Vernstrom, G.D.; Meyers, M.; Brostrom, M.; Stephens, M.; Chan, Q.; Willey, J.; Hamden, M.; Mittelsteadt, C.K.; et al. Initial Performance and Durability of Ultra-Low Loaded NSTF Electrodes for PEM Electrolyzers. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2012, 159, K165–K176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, K.W.; Hernández-Pacheco, E.; Mann, M.; Salehfar, H. Semiempirical Model for Determining PEM Electrolyzer Stack Characteristics. J. Fuel Cell Sci. Technol. 2006, 3, 220–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, A.Z.; Newman, J. Modeling Transport in Polymer-Electrolyte Fuel Cells. Chem. Rev. 2004, 104, 4679–4726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ito, H.; Maeda, T.; Nakano, A.; Kato, A.; Yoshida, T. Influence of pore structural properties of current collectors on the performance of proton exchange membrane electrolyzer. Electrochim. Acta 2013, 100, 242–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinosa-López, M.; Darras, C.; Poggi, P.; Glises, R.; Baucour, P.; Rakotondrainibe, A.; Besse, S.; Serre-Combe, P. Modelling and experimental validation of a 46 kW PEM high pressure water electrolyzer. Renew. Energy 2018, 119, 160–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbir, F. PEM electrolysis for production of hydrogen from renewable energy sources. Sol. Energy 2005, 78, 661–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Z.; Mo, J.; Yang, G.; Li, Y.; Talley, D.A.; Han, B.; Zhang, F.-Y. Performance Modeling and Current Mapping of Proton Exchange Membrane Electrolyzer Cells with Novel Thin/Tunable Liquid/Gas Diffusion Layers. Electrochim. Acta 2017, 255, 405–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bromberger, K.; Ghinaiya, J.; Lickert, T.; Fallisch, A.; Smolinka, T. Hydraulic ex situ through-plane characterization of porous transport layers in PEM water electrolysis cells. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2018, 43, 2556–2569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Merwe, J.; Uren, K.; van Schoor, G.; Bessarabov, D. Characterisation tools development for PEM electrolysers. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2014, 39, 14212–14221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakousky, C.; Reimer, U.; Wippermann, K.; Carmo, M.; Lueke, W.; Stolten, D. An analysis of degradation phenomena in polymer electrolyte membrane water electrolysis. J. Power Sources 2016, 326, 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, B.; Alli, B.; Ahmed, B. Using the hydrogen for sustainable energy storage: Designs, modeling, identification and simulation membrane behavior in PEM system electrolyser. J. Energy Storage 2016, 7, 270–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sartory, M.; Wallnöfer-Ogris, E.; Salman, P.; Fellinger, T.; Justl, M.; Trattner, A.; Klell, M. Theoretical and experimental analysis of an asymmetric high pressure PEM water electrolyser up to 155 bar. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2017, 42, 30493–30508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbabi, F.; Kalantarian, A.; Abouatallah, R.; Wang, R.; Wallace, J.S.; Bazylak, A. Feasibility study of using microfluidic platforms for visualizing bubble flows in electrolyzer gas diffusion layers. J. Power Sources 2014, 258, 142–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmo, M.; Fritz, D.L.; Mergel, J.; Stolten, D. A comprehensive review on PEM water electrolysis. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2013, 38, 4901–4934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, A.Z.; Borup, R.L.; Darling, R.M.; Das, P.K.; Dursch, T.J.; Gu, W.; Harvey, D.; Kusoglu, A.; Litster, S.; Mench, M.M.; et al. A Critical Review of Modeling Transport Phenomena in Polymer-Electrolyte Fuel Cells. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2014, 161, F1254–F1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdin, Z.; Webb, C.J.; Gray, E.M. Modelling and simulation of a proton exchange membrane (PEM) electrolyser cell. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2015, 40, 13243–13257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gostick, J.T.; Weber, A.Z. Resistor-Network Modeling of Ionic Conduction in Polymer Electrolytes. Electrochim. Acta 2015, 179, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, O.; Gambhir, A.; Staffell, I.; Hawkes, A.; Nelson, J.; Few, S. Future cost and performance of water electrolysis: An expert elicitation study. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2017, 42, 30470–30492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Springer, T.E.; Zawodzinski, T.A.; Gottesfeld, S. Polymer Electrolyte Fuel Cell Model. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2019, 138, 2334–2342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Symbols | Value | Organization |

|---|---|---|---|

| Geometrical dimensions: | |||

| Bipolar plate length | LBP | 131 | cm |

| Bipolar plate width | WBP | 2.4 | cm |

| Bipolar plate height | HBP | 1.2 | cm |

| Rib length | LRib | 131 | cm |

| Rib width | WRib | 0.8 | cm |

| Channel length | LCH | 131 | cm |

| Channel width | WCH | 0.8 | cm |

| Channel height | HCH | 0.6 | cm |

| PTL thickness | 0.21 | cm | |

| CL thickness | 0.012 | cm | |

| Membrane thickness | 0.036 | cm | |

| Operating parameter: | |||

| Temperature | T | 293–373 | K |

| Pressure | P | 1–30 | bar |

| Flow rate | v | 1–10 | L/min |

| Physical parameter: | |||

| PTL porosity | 0.5 | - | |

| PTL permeability | 1.0 × 1012 | 1/m2 | |

| Membrane porosity | 0.5 | - | |

| Membrane permeability | 5.0 × 1010 | 1/m2 | |

| CL porosity | 0.3 | - | |

| CL permeability | 6.875 × 1013 | 1/m2 | |

| No. | Grid Quantity | Current Density (A/cm2) | Output Voltage (V) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 56,763 | 1.0 | 2.28 |

| 2 | 75,600 | 1.0 | 2.32 |

| 3 | 129,600 | 1.0 | 2.32 |

| 4 | 213,696 | 1.0 | 2.32 |

| No. | Temperature (K) | Pressure (kPa) | Thickness (μm) | Porosity | Density (A/cm2) | Voltage (V) | Hydrogen Production Rate (g/h) | Energy Efficiency (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 323 | 101 | 360 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1.75 | 50.4 | 68.5 |

| 2 | 323 | 101 | 360 | 0.5 | 2.5 | 2.32 | 252.0 | 62.1 |

| 3 | 343 | 2000 | 200 | 0.5 | 2.0 | 2.02 | 201.6 | 75.6 |

| 4 | 353 | 1000 | 50 | 0.3 | 2.5 | 1.85 | 252.0 | 82.3 |

| 5 | 363 | 1000 | 50 | 0.8 | 2.5 | 1.80 | 252.0 | 84.7 |

| 6 | 343 | 3000 | 200 | 0.8 | 1.5 | 2.15 | 151.2 | 70.2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Yang, D.; Zhang, X.; Li, J.; Rong, F.; Zhu, J.; Li, G.; Ji, X.; He, G. Synergistic Temperature–Pressure Optimization in PEM Water Electrolysis: A 3D CFD Analysis for Efficient Green Ammonia Production. Energies 2026, 19, 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010002

Yang D, Zhang X, Li J, Rong F, Zhu J, Li G, Ji X, He G. Synergistic Temperature–Pressure Optimization in PEM Water Electrolysis: A 3D CFD Analysis for Efficient Green Ammonia Production. Energies. 2026; 19(1):2. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010002

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Dexue, Xiaomeng Zhang, Jianpeng Li, Fengwei Rong, Jiang Zhu, Guidong Li, Xu Ji, and Ge He. 2026. "Synergistic Temperature–Pressure Optimization in PEM Water Electrolysis: A 3D CFD Analysis for Efficient Green Ammonia Production" Energies 19, no. 1: 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010002

APA StyleYang, D., Zhang, X., Li, J., Rong, F., Zhu, J., Li, G., Ji, X., & He, G. (2026). Synergistic Temperature–Pressure Optimization in PEM Water Electrolysis: A 3D CFD Analysis for Efficient Green Ammonia Production. Energies, 19(1), 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010002