Abstract

Off-grid renewable energy systems have become a cost-effective way to supply electricity in remote rural areas, contributing to achieving universal energy access as mandated by Sustainable Development Goal 7 (SDG7). However, benefits are often compromised by limitations in the financial and technical capacity and capabilities of rural beneficiaries to operate and maintain the technology, raising concerns about the cost-effectiveness of investment in the systems. This study examines the non-economic social benefits of providing electricity through off-grid renewable systems and whether these benefits justify investment in the efforts and costs borne by rural communities. Using the case study of the community-managed Kalilang micro-hydro power plant (MHPP) operating on Sumba Island, Indonesia, we estimate the value of non-market benefits of off-grid renewable electricity in rural Indonesia. By applying a mixed-methods approach, this research qualitatively identified perceived non-market benefits through 16 key informant interviews and subsequently employed contingent valuation (CV) with 105 households to estimate their willingness-to-pay (WTP) for these benefits. The results suggest that off-grid renewable projects remain socially viable even when direct economic returns are lacking. Inclusion of these social values into project evaluation and appraisals is needed to better reflect the contribution of off-grid renewable energy systems to community well-being.

1. Introduction

Off-grid renewable power plants are a crucial tool in efforts to progress towards achieving Sustainable Development Goal 7 (SDG7), “Ensure access to affordable, reliable, sustainable and modern energy for all.” They can be built in remote areas, utilising locally available energy resources, conferring a significant advantage for electrification compared to the high cost and technical challenges of main grid extension [1,2]. In an archipelagic country like Indonesia, with 17,000 islands, the development of off-grid renewable power plants is crucial to the government’s efforts to electrify the entire nation [3]. The Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources (MEMR) provides incentives for the utilisation of off-grid renewable sources as part of a strategy to accelerate rural electricity provision [4]. In 2021, more than three gigawatts of off-grid electricity were produced [5] for more than 14,000 customers [6]. Additionally, establishment of off-grid renewable power plants can reduce the financial burden on the state electricity company, Perusahaan Listrik Negara (PLN), from the high operational cost of diesel generators, which have been a primary energy source for remote areas for decades [7].

However, there are numerous examples in Indonesia of newly established off-grid power plants that operate for only a short time and thus significantly fail to impact rural development [8,9,10]. Research results highlighted the beneficiaries’ lack of institutional and financial capacity to operate and maintain the power plants as the main issue leading to a lack of longer-term sustainability [11]. This then reduces the community’s ability and willingness to pay for the power supplied, particularly for operation, repair, and maintenance costs. Although considered an important part of SDG7’s efforts to reduce energy poverty, community-based off-grid power plants create significant additional work for beneficiaries. Consequently, the policymaker not only has to find a way for monthly tariffs to be paid, but also to deal with long-term institutional and technical issues [12]. This situation is evident in Sumba Island, an island that was to be electrified using renewable energy a decade ago, and then, according to reports and research studies (e.g., [9,13,14,15]) some of the projects are now abandoned due to the inability of communities to keep the systems working [13,14].

The burden imposed on communities to maintain and operate off-grid renewable energy raises the question of whether construction of community-based power plants by outside agencies can be justified from the perspective of beneficiaries. In other words, do the cost outweigh the benefits of electricity for rural households? This research addresses this question using the case study of the Kalilang micro-hydro power plant (MHPP) on Sumba Island, Indonesia. Our study looks beyond the techno-economic considerations of electricity’s benefits by exploring the social values. Researchers tend to discuss the benefits of electricity from either a macro-development perspective or a technological perspective, with the technical aspects of electricity systems as the primary focus [3,16,17,18,19,20]. In contrast, this research discusses the benefits of rural electricity, particularly through off-grid renewable systems, from the perspective of the beneficiaries by investigating the often overlooked primary social advantages provided. We identify and estimate the value of these benefits to communities and highlight the role of electricity with relevance to social utility, including social security, due to its contribution to people’s health and education [21,22,23,24]. Both qualitative and quantitative approaches were employed to explore the benefits using key-informant interviews and the Contingent Valuation (CV) method for estimating households’ willingness to pay (WTP) for the identified social benefits of rural off-grid renewable electricity.

This article is structured as follows. In the Section 2, we review off-grid renewable electricity provision in rural areas and its significance for rural development and explain the use of WTP values for addressing our research question. In the Section 3, we describe our case study and how the data is obtained and analysed. The Section 4 presents the results, which are followed by a discussion of their relevance to addressing our research question and policy implications. Conclusions are presented in the Section 6.

2. Literature Review

The recognition of energy as a key part of sustainable development in SDG7, together with increasing affordability of new technologies, has spurred widespread installation of off-grid power plants, particularly in Africa and Asia [25], as a promising solution for electrifying hard-to-reach areas not served by the main grid. Extending grid systems to remote areas with challenging topography, low population density, and low electricity demand is expensive, with costs of up to ten times higher than off-grid systems for remote regions [26]. Consequently, the number of individuals receiving electricity from off-grid systems has been increasing in recent years. IRENA [25] estimated that approximately 133 million people worldwide relied on off-grid renewable energy generators as their primary energy sources in 2016. In terms of capacity, from 2008 to 2017, there was a more than 4 GW increase in electricity generated from off-grid renewable generators. Moreover, decentralised electricity systems extended beyond household applications, such as the use of electric vehicles and in the manufacturing sector [27].

Technological advances have increased the efficiency of off-grid renewable power plants and significantly decreased costs, particularly in solar-based systems. According to the World Bank [28], off-grid solar products are the cheapest solution to provide Tier 1 access to electricity for powering basic appliances. Bhattarai & Thompson [29] demonstrated that the application of wind energy, despite its marginal resource capacity, resulted in remarkable cost and emission reductions and high electrical reliability. In most Indonesian provinces the utilisation of solar PV was at least USD 0.05/kWh cheaper than diesel power plants even more than a decade ago [30]. Similarly, in Egypt, solar PV could reduce the electricity cost by around USD 0.20/kWh [31]. The generation cost report published by IRENA [32] reveals that within the period 2010–2021, solar PV experienced an 88% cost reduction, from USD 0.417/kWh to USD 0.048/kWh. Within the same period, the average cost of onshore wind generators also fell by 68%, from USD 0.102/kWh to USD 0.033/kWh. Additionally, when environmental costs associated with greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions are included, the economic advantage of the off-grid renewable generator is much greater [26].

Off-grid renewable power plants are typically managed by individuals and the community rather than by the state-owned utility companies. In remote rural areas, these plants are often developed and funded by external entities before being transferred to community management upon becoming operational. This transition can pose challenges in the operation and maintenance of power plants [33]. Barriers to effective implementation of off-grid renewable power plants in rural contexts include insufficient skills and awareness [10,12], limited understanding of community behaviour [34], inadequately designed financial models [10], and ambiguous long-term objectives [35]. These obstacles underscore the complexity of technological interventions in rural environments. For providers, it is essential to develop policy trajectories informed by a thorough understanding of beneficiary behaviour [36]. Case studies from Sumba, Indonesia [37] and Malaysian Borneo [38] illustrate the influence of sociocultural factors on the deployment of off-grid renewable electricity. In Indonesia, neglecting village-level micropolitics impeded equitable access to electricity; while in Malaysian Borneo, community scepticism presented a significant barrier. Furthermore, the capacity and motivation of beneficiaries to establish effective institutional structures [39], consistently pay tariffs [33], and engage in capacity-building initiatives [35] are critical for ensuring the long-term sustainability of these systems.

The complex challenges of operating off-grid power plants in rural communities raises the question of whether off-grid-generated electricity benefits or burdens households. This topic is not well-explored in the current literature. We found that researchers are either focused on macro-level impacts of electricity such as poverty [3,16], the rural economy [17], and socio-environmental impacts [18,40]. On the other hand, technical scholars tend to focus on discussions of generator production costs, with development feasibility as the primary focus (see [1,19,20]). Despite all the different aspects being intertwined to collectively constitute multidimensional social security benefits due to its relevance on socio-economic vulnerability reduction, increases in life expectancy, and long-term human health variables [24], the macro discussion of such benefits often overlooks the nuanced understanding of how electricity is perceived and valued within communities and subsequently shapes their everyday practices.

The valuation of non-economic benefits of electricity has been prominent in discussions of rural electricity. Researchers have utilised various methods to estimate the non-market value of electricity provision to rural households, including contingent valuation [41,42,43], choice experiments [44,45], and the auction method [46]. The current literature on valuing non-market aspects of electricity primarily discusses improvements in service, including greater capacity, longer duration, and enhanced reliability [42,43,44,45]. Additionally, some studies estimated people’s willingness to pay (WTP) for exploring the acceptance of renewable sources, as demonstrated by Zuch [46] in sub-Saharan Africa and Nduka [41] in Nigeria. Despite the widespread application of WTP across diverse aspects of electricity provision, we found limited use of the approach to value how electricity is perceived and the social benefits it provides to communities, which cannot be captured by macroeconomic analysis. This research aims to fill this knowledge gap by providing a more nuanced understanding of how beneficiaries perceive and value the social benefits of electricity, and which of these are considered most important from a household perspective.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. The Case of Kalilang MHPP in Sumba, Indonesia

This study examines the Kalilang micro-hydro power plant (MHPP) in Kambata Bundung Village, East Sumba Regency, Indonesia. The selection of this power plant is for two main considerations. Firstly, the community, through a village cooperative, is fully responsible for the operation and maintenance (O&M) of the power plant. This allows them to receive economic and social benefits independent of management inputs from external support, such as government subsidies or donor funding, for running the system. The community has been encouraged to participate in the management of the Kalilang MHPP since its development phases. Due to its remote location, the community collaborated with the Indonesian non-governmental organisation IBEKA, based primarily in Jakarta, Indonesia, to construct 2.6 km of access track to the site. They also manually transported some of the MHPP components, including turbines. IBEKA reported that approximately 400 people were involved in establishing the MHPP [47]. The community is also involved in setting monthly tariffs. One of the key informants stated that the beneficiaries determined the basic tariff of 0.5 Amperes and the tariffs for 2 and 4 Amperes. Secondly, the Kalilang MHPP is fully operational as a community-based off-grid power plant. This is in contrast to some projects elsewhere on Sumba where community-based off-grid generators are non-functional due to institutional issues [9].

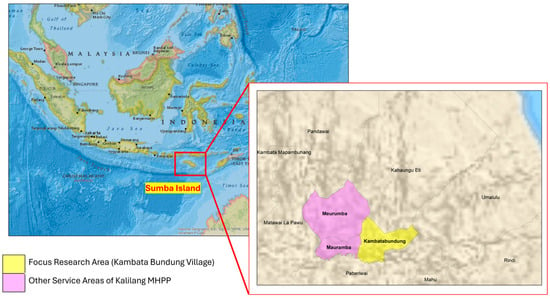

The Kalilang MHPP was established in 2018 by IBEKA [47] as part of its programme for rural electrification as a tool for community empowerment [48]. The Kalilang MHPP is located in Kambata Bundung Village (see Figure 1) and has a capacity of 65 kW. During the initial period of operation, the Kalilang MHPP successfully electrified approximately 400 households in four villages: Kambata Bundung, Madutolung, Mauramba, and Meurumba [47,49]. However, due to damage caused by the Seroja cyclone in 2021, the power plant is not working as initially planned. The restoration was proceeding slowly due to the cooperative’s limited financial capacity. The money collected from customers is mainly used to provide incentives to the managers and operators; therefore, the ability to fund a major restoration is constrained. Nevertheless, with external funding, the connection in two of the four villages has been restored, namely Kambata Bundung and Madutolung, in East Sumba Regency. We focus our analysis on the village of Kambata Bundung.

Figure 1.

Study Location.

3.2. Data Collection

This research utilises both qualitative and quantitative approaches to combine the consistency and repeatability of numerical analysis whilst also capturing the nuance of complex issues [50]. The qualitative approach provides insight into community processes and experiences related to electricity [51]. Whilst the quantitative approach provides measurable evidence [52]. We employed two steps in the data collection and analysis. Firstly, semi-structured interviews with relevant stakeholders were conducted to understand the perceived benefits of electricity, the current state condition of the service, and the potential influencing factors. Secondly, we conducted end-user interviews to assess the value of the identified benefits. Consent to conduct interviews was obtained through formal letters from government agencies and non-governmental organisations (NGOs); for the village-level informants, consent was obtained verbally prior to the interview. The field research protocol was assessed and approved by the Research Ethics committee of University of Leeds (reference code AREA 19-162).

In the first set of interviews, we spoke with 16 key informants from local and provincial government agencies, NGOs, and village stakeholders, including village officials and customary leaders. The interviews were conducted face-to-face in Bahasa Indonesia. Informants were asked how they perceive electricity, what changes have resulted from its arrival, how the beneficiaries utilise appliances in general, and what has been varying the electricity behaviour among the communities. All the informants’ statements were recorded and transcribed verbatim. The transcripts were coded and categorised to identify the perceived benefits of electricity that are generally applicable in our study area. These perceived benefits and influencing factors were later considered in the monetisation of WTP and further statistical analyses. Meanwhile, other information obtained was used to enrich the interpretation of the results.

Data gathering in the second step focused on the benefits identified in the first step of data collection. We conducted 105 end-user interviews with Kalilang MHPP customers in Kambata Bundung Village. This represented 37.5 per cent of the total customers currently connected to the Kalilang MHPP. In conducting this phase, we were assisted by Sumbanese enumerators. The use of enumerators from Sumba helped overcome cultural and language barriers when asking questions. We applied three measurements to minimise sampling bias in determining our informants. First, we placed enumerators in several hamlets to ensure a representative geographical distribution of respondents, including both accessible and hard-to-access hamlets. Secondly, the number of respondents was determined proportionally to the total number of electricity consumers in the hamlets, and lastly, the enumerators were instructed to cover different customer types: 0.5 Ampere customers (62.81%), 2 Ampere customers (24.76%), and 4 Ampere customers (11.43%).

3.3. Applying the Contingent Valuation Approaches

For estimating the value of non-market benefits, also referred to here as the social benefits of electricity, we employed contingent valuation (CV), a widely used stated-preference monetisation approach in which individuals are asked to reveal their hypothetical values [53]. This method is usually associated with questionnaires and structured interviews as the primary data collection tools, particularly for determining people’s WTP across fields such as environmental management [54,55], agriculture [56], and energy [57,58]. We applied the double-bounded dichotomous choice (DBDC) format for our structured interviews. This method was introduced by Hanemann et al. [59] and is among the most prevalent CV methods due to its statistical efficiency [60]. Hanemann et al. [59] argue that DBDC extracts more precise information about an individual’s WTP than the single-bounded format, as it imposes tighter boundaries on the stated value, thereby shrinking the margin of error.

We followed NOAA’s suggestion to use the referendum format for CV, as it is more realistic than an open-ended question, which can produce erratic and biased answers [61]. We presented respondents with a hypothetical scenario, for example, if electricity disappears, how much would you be willing to pay to obtain the non-market benefits? (see Appendix A for the exact words). There is a possibility of hypothetical bias in this approach, as the respondents knew it was hypothetical and that it would not actually happen. Arrow et al. [61] stress that effort should be made to ensure respondents take the question seriously. We did this by asking questions to revive respondents’ memories of their lives before the electricity era, so they could clearly picture what the hypothetical situation would be if the electricity system failed. Further, instead of asking about the value of losing the existing services, we asked respondents to value the benefits they have compared to the pre-electricity era, with the benefits explained prior to the end-user interviews. Additionally, the assessed benefits persist and are being experienced by the respondents. Hence, the hypothetical biases can be reduced as they have a sense of the situation they are experiencing when answering the questions.

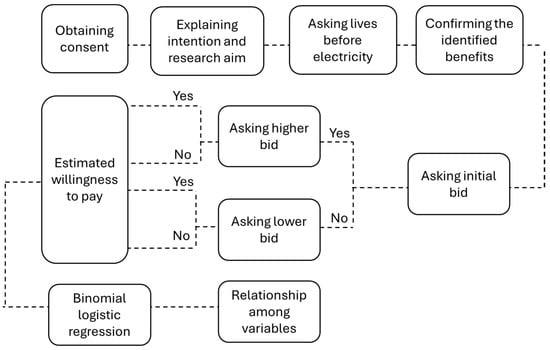

In the hypothetical situation, respondents are offered an initial bid and expected to respond with either yes or no. Depending on the initial response, respondents are offered a second bid, to which they can respond with either yes or no (see Figure 2). If the answer to the first bid is yes, the respondents will be presented with a higher bid. Conversely, the second bid will be lower if the first answer is no. For this research, we used three sets of bids in Indonesian Rupiah (IDR): (1000; 2000; 5000), (8000; 10,000; 20,000), and (15,000; 25,000; 50,000). The middle values are the initial bid, whereas the first and third values are the lower and higher follow-up bids. The sets of bids also take into account the results of our pilot survey, in which we tested a number of beneficiaries using the second set. Our pilot survey yielded many anomalous responses: people either always agreed (primarily due to their excitement about the arrival of electricity) or always disagreed (protest responses), due to familiarity with the previous situation and limited use of money as a trade and measurement tool. We further confirmed this situation through interviews with the government and village authorities, revealing that the current tariff structure is the result of deliberation and a middle path between these two groups in the community, and does not necessarily reflect the need to operate and maintain the power plant. In order to capture respondents’ variations, we thus applied multiple bid sets, considering the possibility that the respondent’s value might fall below the basic tariff (first set of bids), around the amount of basic tariff (second set of bids), and more than the highest tariff (third set of bids). It also reduces the likelihood that the starting point will excessively influence the WTP estimates [62].

Figure 2.

Flow diagram of how the double-bounded dichotomous choice is applied (adapted from Chang [63]).

The general flowchart of our research method is presented in Figure 2. As Gelo & Koch [63] explain, if an individual is denoted by i and their set of responses is denoted by Y, Yi = {Yi1, Yi2} where Yit = {1, 0} = {yes, no}, and t = {1, 2} constitutes the number of bids presented to the individual. Using a rational assumption where an individual does not want to pay more than they are willing, the bid responses yield interval values for estimating their WTP. If the bid is denoted by b, mathematically, the estimation of WTP will be as follows: if Yi = (no, no) ⇔ WTPi < bi2, Yi = (no, yes) ⇔ bi1 > WTPi ≥ bi2, Yi = (yes, no) ⇔ bi1 ≤ WTPi < bi2, Yi = (yes, yes) ⇔ WTPi ≥ bi2.

We utilised the statistical package R to estimate the mean and median WTP for non-market benefits using the DCchoice package [64], which provides functions for analysing responses to CV questions (for a detailed explanation, see Aizaki et al. [65]). This method provides maximum likelihood estimation procedures tailored for dichotomous-choice contingent valuation models, including the double-bounded format. The logit formulation assumes a logistic distribution for the unobserved components of utility and enables consistent estimation of the bid-response relationship from which welfare measures such as median willingness to pay are derived. The combined use of the DBDC elicitation format and a logit-based estimation strategy ensures that the resulting WTP estimates possess high internal validity and policy relevance [59].

Lastly, as this study aims specifically to understand how inhabitants value electricity socially, the estimated WTP values reflect their willingness to pay for the identified non-market benefits on a monthly basis. In other words, it represents the amount a typical household would be willing to pay each month to secure the described benefits. This specification also supports policy relevance by providing decision makers with a clear understanding of the ongoing financial commitment households are willing to bear for the intervention. This study thus does not perform any sensitivity analyses related to the resulting WTP values, such as varying the discount rate or adjusting the estimated WTP by proportional changes. This decision reflects the specific scope and intended use of the valuation results, which were not designed to support a full benefit–cost analysis or long-term economic projections, which typically require testing the robustness of present-value calculations or alternative WTP assumptions. Instead, the primary objective of the research is to provide indicative, cross-sectional estimates of household WTP for the proposed intervention, based directly on the stated preferences elicited from the sample. Conducting formal sensitivity tests would imply a level of generalisation and policy precision beyond the study’s purposes, especially given that the sample is not representative of the broader population. Accordingly, the analysis intentionally focuses on reporting the empirically derived WTP estimates without extending them into scenario-based robustness evaluations.

4. Results

4.1. Perceived Benefits of Electricity Generated by the Kalilang MHPP

Based on our interviews, we identified five non-market benefits of electricity to rural communities. The non-market benefit is any benefit that lacks a market value; hence, a specific method is needed to estimate its value. The summary of these benefits is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

The identified non-market benefits.

The benefits presented in Table 1 result from the adoption of electrical appliances. Among these, lighting has the greatest impact on rural communities, as it has substantially altered daily routines by extending the time available for activities. Before electrification, as observed in most of rural Sumba, beneficiaries of Kalilang typically ceased activities after sunset. The introduction of electric lighting has enabled continued engagement in activities such as weaving, socialising, and studying during evening hours. Additional indirect benefits are linked to the use of mobile phones and television. According to informant observations, the community primarily utilises these devices for entertainment, including watching dramas, YouTube, social media, and football matches. Informants also highlight the use of mobile phones with internet access for obtaining information. Although this informational use is less prominent than entertainment, certain community groups consider it valuable, particularly for supporting students’ studies and helping women find recipes.

Electricity has also contributed to the community by improving access to clean water and facilitating customary ceremonies. Although most residents of Sumba Island had access to clean water prior to electrification [66], the island’s hilly topography meant that water sources were typically located in valleys, requiring residents to travel considerable distances over difficult terrain [67]. The introduction of electricity enabled the use of communal water pumps, significantly simplifying the water-collection process and reducing the need for lengthy, challenging journeys. Furthermore, electricity has also enhanced the convenience of conducting customary events due to the use of lighting, and other appliances for gathering such as microphone and sound systems.

4.2. Estimated Willingness-to-Pay Values of the Identified Benefits

To obtain a picture of how people value electricity’s social benefits, we estimated their WTP for each of the identified benefits. We applied DBDC questions to 105 MHPP beneficiaries in Kalilang. Table 2 presents the general characteristics of our respondents. Most (95.24%) of our respondents are farmers, while the remaining 5 are builders (2.86%), priests (0.95%), and an employee at the village office (0.95%). Some might argue that this leads to representative bias due to the exclusion of people engaged in other livelihoods; however, most of the population engaged in subsistence agriculture, with only a small number working in other sectors. Additionally, the more accessible hamlets might be over-represented due to accessibility issues during data collection. In response to this situation, we purposively selected hamlets to ensure spatial representativeness within the village. While we experienced difficulties accessing some hamlets, we did involve respondents from hamlets with limited accessibility to fulfil spatial representativeness, and respondents were randomly selected in proportion to the number of electricity beneficiaries.

Table 2.

The characteristics of respondents.

Table 2 also shows that, in terms of income distribution, most of our respondents live on less than IDR 1,200,000 ≈ USD 77 per month. 45% of them even obtained less than IDR 600,000 ≈ USD 38 a month. This amount is less than a third of the regional minimum salary in the East Sumba Regency, i.e., IDR 1,975,000 ≈ USD 126.5 a month. This, we argue, is closely related to the subsistence nature of their livelihoods, in which money is not the primary aim. As for household size, around 47% of our respondents live with 4 to 6 people, while 33% live with more than 7 people, including extended family living under the same roof.

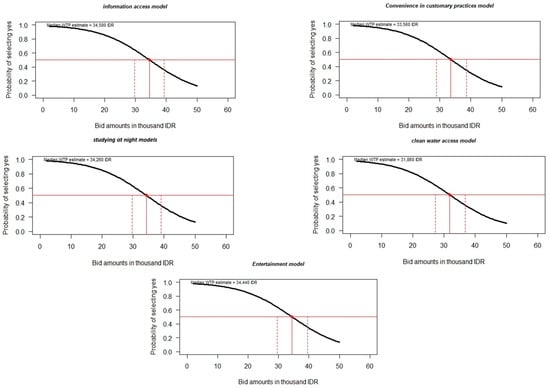

The DBDC method applied in this study enables measurement of willingness to pay (WTP) for societal benefits that are not captured by the market price approach. As shown in Figure 3, the WTP model demonstrates general consistency. The difference between the highest WTP (information access) and the lowest (clean water access) is approximately IDR 2700 ≈ USD 0.18. Notably, the benefit of electricity in providing improved access to clean water is perceived as the least valuable. Although clean water is essential for healthy human life, respondents assign greater value to the information and entertainment functions of electricity than to other benefits. The WTP values for these benefits are IDR 34,580 ≈ USD 2.28 and IDR 34,440 ≈ USD 2.27, respectively, while clean water access is valued at IDR 31,860 ≈ USD 2.10.

Figure 3.

The WTP models of each non-market benefit, the red dots indicate median WTP values in each non-market benefits and the dash-lines indicate standard deviation of the WTP values.

4.3. The Role of Household Size and Income

Binomial logistic regression analysis was conducted to examine the relationship between respondents’ answers in the DBDC interview and the independent variables of household income, household size, and bid value. These independent variables were determined based on our initial interviews, which identified household size and economic situation as among the most significant factors affecting household energy consumption in Kambata Bundung. While the unit is household-based, our interview also confirmed that individual attributes such as age, education, and gender are of limited relevance. Table 3 presents the results. The bid value variable shows significant p-values for all non-market benefits at the 0.001 significance level, indicating a higher likelihood of a ‘yes’ response when the bid value was lower. In contrast, household size did not exhibit significant p-values for any non-market benefits, suggesting minimal influence on respondents’ answers. The income variable was statistically significant for three non-market benefits: clean water access (p = 0.007), information access (p = 0.046), and studying at night (p = 0.014). Income was not significant for convenience in customary practices (p = 0.213) and entertainment (p = 0.145). These findings indicate that higher-income households are more likely to prioritise essential benefits, such as access to clean water, information, and the ability to study at night.

Table 3.

The regression results.

5. Discussion

Our results show the important role of off-grid renewable electricity, not only through direct-use economic metrics, but by enhancing the multi-dimensional quality of life for beneficiaries. While previous studies often emphasised the productive use of electricity as an association between electricity provision and rural poverty alleviation (see [17,68,69,70]), our findings suggest electricity’s immediate value for beneficiaries lies in the social sphere through non-market benefits. The high value placed on entertainment and information access challenges the perspective that prioritises basic physical necessities such as water pumping, which, from a developmentalist perspective, is considered highly beneficial for rural inhabitants [16,71]. The role of electricity in providing information access, entertainment, and supporting educational opportunities as highly valued benefits aligns with the broader literature on energy poverty, which argues that access to electricity is a prerequisite for modernisation, allowing remote communities to connect with modern society through access to national-global materials, including entertainment and information, extended productive hours, and broader social interaction [72]. This is a common response when people are asked about what makes a better life as they tend to focus on variables they feel they lack and which others possess [73].

Our results support the notion that providing electricity to rural households is pivotal for reducing social exclusion and enhancing safety. In the case of Sumba, electricity functions as a safety asset which is, according to Chomać-Pierzecka, et al. [24], substantially linked to an increase in well-being and quality of life, by reducing economic vulnerability, through making more time available for producing weaved products and to engage in education. This then offers opportunities for long-term economic benefits. Moreover, electricity enables greater socio-cultural participation when holding customary events through provision of lighting and loudspeakers. On a wider level, exclusion from services provided by government elsewhere in less remote locations, such as electricity, is a form of social exclusion associated with poverty [74,75]. By facilitating social connections that significantly expand access to information, the restriction on the community’s participation in wider political and social spheres gradually diminishes. In other words, for our respondents, despite all the burdens and limitations, off-grid electricity acts as a buffer against isolation, not only in the geographical sense, but also in terms of access to, and inclusion in, information exchange. Without electricity, community members only have a limited understanding and interaction with the outside world, hence making them socially excluded [72].

Our case also demonstrates a positive relationship between income and WTP with the relatively richer people in the community tending to prioritise particular advantages of electricity access by placing higher bids for them. Sievert & Steinbuks [76] found a similar pattern in Sub-Saharan Africa, where people’s electricity demand increased as they became wealthier. In the context of Sumba, wealthier individuals are more inclined to place a higher bid for benefits related to water supply, access to information, and night studying. These benefits are closely tied to the reliability of electricity connections. For example, with a reliable electricity connection, the capacity of water pumps can be increased, resulting in improved water supply. Similarly, a more reliable connection provides better lighting, making it more comfortable and healthier for children to study at night. These benefits are highly valued by individuals who can afford more than just basic services and have a demand for enhanced reliability and functionality.

Lastly, although the value of WTP estimated in this research is embedded in the case under scrutiny, and thus not generalisable in a wider context, we argue that the emphasis on non-market benefits as valuable advantages to rural inhabitants from off-grid electrification is a generically applicable result. Including non-market social values into project appraisals could provide a justification for supporting investment in off-grid renewable systems when market-based cost–benefit analysis is low or negative. If electricity is viewed strictly as a commodity for producing direct monetary benefits, the low economic returns in areas like Kambata Bundung might suggest project failure. However, when viewed through the lens of social security, the relatively high WTP for non-economic benefits validates the investment as being for the public good. The mere presence of electricity in the village generates social benefits in general, underscoring its significance as basic infrastructure for rural communities. The non-market valuation of off-grid electricity access for remote rural communities indicates that electrification policies should view electricity as a multi-dimensional public benefit, with social considerations integral to investment appraisal.

In some cases, in rural areas, the arrival of electricity cannot initially generate economic income to the beneficiaries due to reasons such as the worldview and knowledge differences [36], adherence to the long-existing practices [68], limited access to market and entrepreneurial capacities [68,77], as well as specific local-institutional dynamics [37]. The expectation that electricity contributes to poverty by promoting rural economic development may not apply in some cases. Our results support the conclusions of Fingleton-Smith [68] in the need to nuance the narrative of electricity benefits beyond economic considerations and to understand how electricity benefits the community’s social practices [73]. The inclusion of non-market values and social return methodology should be part of acceptable measurements for project evaluation in addition to narrow financial tools. In practice, these methodologies lead to a shift in the primary discourse on rural electrification and enable a complementary intervention that amplifies the multiple benefits households prioritise. In this research, for example, the identified social benefits are among the most prominent perceived advantages of electricity for Kalilang MHPP beneficiaries. When planning interventions for off-grid electricity generation, support for initiatives such as communal water pumps, shared information hubs that expand education and livelihood opportunities, and education at night should be included alongside economic incentives.

6. Conclusions

Our examination of non-market benefits in Kambata Bundung Village confirms that, despite the additional burdens placed on the community from operation and maintenance and technical limitations of the type of technology that can be reliably operated under community management, off-grid renewable electricity yields significant non-market benefits that are highly valued by the community, even in the situation of limited direct economic returns. Access to electricity enables the provision of information and communication services that may have been lacking in the past. By including such benefits, we gain an understanding of how electricity socially influences its beneficiaries beyond its potential economic benefits. The contingent valuation results show that households place a positive monetary value on social gains such as improved information access, entertainment, and evening study opportunities, with these values collectively indicating favourable benefits of electricity even when direct economic benefits are limited. Our analysis further shows that household income generally influences valuation, as wealthier households tend to place higher bids for reliability-dependent benefits. Overall, the findings suggest that off-grid renewable projects remain socially viable and justifiable by serving as a buffer against social exclusion and by enhancing local social safety.

This research provides empirical evidence on the social benefits of electricity access in rural communities, contributing to ongoing debates surrounding rural electrification. Despite a consensus among development actors of the benefits of electricity to rural communities, the literature quantifying the extent to which these benefits are received and perceived is limited. Addressing the question of “how much” these benefits are received and perceived by rural inhabitants is an important component for the formulation of rural electricity policies. Understanding the affordability and actual benefits derived from electricity programmes is a prerequisite for policymakers in designing effective tariff plans and implementing complementary interventions. This information can guide the formulation of tariff structures, subsidy schemes, or other support mechanisms to maximise the benefit of electricity beyond economic considerations.

Lastly, despite the contribution, this research is constrained by several limitations that limit the generalisability of the results, particularly regarding the specific WTP values identified. The use of Kambata Bundung as a single case study makes the WTP estimation contextually embedded, as the respondents were predominantly subsistence farmers who adhered to cultural norms called marapu beliefs. Hence, different valuations might occur in other socio-economic–cultural situations. Secondly, our approach to investigating the perceived value of social benefits at a single point in time does not account for dynamic effects within the community under study, such as adaptation to technology and changes in indirect income, which may influence their perceived value. The utilisation of the CV method also poses a hypothetical bias limitation. Although we have made efforts to minimise this potential bias, we acknowledge that the stated WTP may differ from actual payment behaviour as respondents might over- or understate values depending on their importance. Accordingly, further research in varying socio-cultural settings and the incorporation of dynamic modelling can be a good fit for understanding non-market advantages of electricity holistically.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.W. and J.C.L.; methodology, H.W., J.C.L. and C.W.; formal analysis, H.W., J.C.L. and C.W.; data curation, H.W. and S.S.; writing—original draft preparation, H.W. and M.G.R.A.T.; writing—review and editing, J.C.L.; supervision, J.C.L. and C.W.; funding acquisition, H.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research is funded by Ministry of Education and Research of the Republic of Indonesia through the BPPLN scholarship scheme as well as the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council of UK through the project entitled ‘Creating Resilient Sustainable Microgrids through Hybrid Renewable Energy Systems’ (EP/R030243/1). Ongoing collaboration on the project was provided through the University of Leeds International Strategy Fund ‘Indonesia Net Zero Network’ project.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and analysed during the current study are not available due to containing respondents’ individual data but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for the assistance from various parties, including Kang Li and Martin Zebracki as the first author’s supervisors, as well as the enumerator team from Wira Wacana Christian University.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest, and the funders had no role in all the research process.

Appendix A. An Example of Contingent Valuation Interview Guideline

Note: it is a translated version as the actual interviews used Bahasa Indonesia.

Surveyor:

Village Name:

- I.

- RESPONDENT IDENTITY

- a.

- Number of family members: ……………………………… people

- b.

- Main occupation of head of family: ………………………………

- c.

- Estimated income: ……………………………… Rupiah per day/week/month

- II.

- ELECTRICITY COSTS

- a.

- How much is the electricity cost per month? ……..………………… Rupiah per month

- b.

- Have you ever paid other than those costs? Yes/Never

- c.

- If yes, for what? …………………………………………………..

- III.

- INDIRECT BENEFITS

- a.

- Access to clean water—With the existence of electricity, clean water can be distributed to houses using pumps. Can you imagine if the electricity goes out, how you would have to put in extra effort to get water?

- a.1. If there were no electricity, would you be willing to pay 2000 Rupiah so that clean water could flow to your house?—If the answer is yes, continue to a.2., if the answer is no, continue to a.3.

- a. Yes b. No

- a.2. If yes (in question a.1), would you be willing to pay 5000 Rupiah so that clean water could flow to your house?

- a. Yes b. No

- a.3. If no (in question a.1), would you be willing to pay 1000 Rupiah so that clean water could flow to your house?

- a. Yes b. No

- b.

- Access to information—With the existence of electricity, you become able to access news or information from outside via Mobile Phone or TV. Can you imagine if the electricity goes out, what you would feel if you could not access that information?

- b.1. If there were no electricity, would you be willing to pay 2000 Rupiah to access information or news?—If the answer is yes, continue to b.2., if the answer is no, continue to b.3.

- a. Yes b. No

- b.2. If yes (in question b.1), would you be willing to pay 5000 Rupiah to access information or news?

- a. Yes b. No

- b.3. If no (in question b.1), would you be willing to pay 1000 Rupiah to access information or news?

- a. Yes b. No

- c.

- Comfort of customary events—With the existence of electricity, customary events such as ceremonies can use lights and sound systems. Can you imagine what would happen to those events when the electricity goes out?

- c.1. If there were no electricity, would you be willing to pay 2000 Rupiah so that customary events could use electronic devices?—If the answer is yes, continue to c.2., if the answer is no, continue to c.3.

- a. Yes b. No

- c.2. If yes (in question c.1), would you be willing to pay 5000 Rupiah so that customary events could use electronic devices?

- a. Yes b. No

- c.3. If no (in question c.1), would you be willing to pay 1000 Rupiah so that customary events could use electronic devices?

- a. Yes b. No

- d.

- Entertainment—With the existence of electricity, you become able to access entertainment via Mobile Phone or TV. Can you imagine if the electricity goes out, what you would feel if you could not access that entertainment?

- d.1. If there were no electricity, would you be willing to pay 2000 Rupiah to access entertainment/social media?—If the answer is yes, continue to d.2., if the answer is no, continue to d.3.

- a. Yes b. No

- d.2. If yes (in question d.1), would you be willing to pay 5000 Rupiah to access entertainment/social media?

- a. Yes b. No

- d.3. If no (in question d.1), would you be willing to pay 1000 Rupiah to access entertainment/social media?

- a. Yes b. No

- e.

- Night activities—With the existence of electricity, you become able to be active at nighttime. Can you imagine if the electricity goes out, what you would feel if you could not be active at night?

- e.1. If there were no electricity, would you be willing to pay 2000 Rupiah so that you could be active at night?—If the answer is yes, continue to e.2., if the answer is no, continue to e.3.

- a. Yes b. No

- e.2. If yes (in question e.1), would you be willing to pay 5000 Rupiah so that you could be active at night?

- a. Yes b. No

- e.3. If no (in question e.1), would you be willing to pay 1000 Rupiah so that you could be active at night?

- a. Yes b. No

References

- Blum, N.U.; Sryantoro Wakeling, R.; Schmidt, T.S. Rural Electrification through Village Grids—Assessing the Cost Competitiveness of Isolated Renewable Energy Technologies in Indonesia. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2013, 22, 482–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trotter, P.A.; Cooper, N.J.; Wilson, P.R. A Multi-Criteria, Long-Term Energy Planning Optimisation Model with Integrated on-Grid and off-Grid Electrification—The Case of Uganda. Appl. Energy 2019, 243, 288–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirawan, H.; Gultom, Y.M.L. The Effects of Renewable Energy-Based Village Grid Electrification on Poverty Reduction in Remote Areas: The Case of Indonesia. Energy Sustain. Dev. 2021, 62, 186–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MEMR Permen ESDM No. 38 Tahun 2016. 2016. Available online: https://peraturan.bpk.go.id/Details/143370/permen-esdm-no-38-tahun-2016 (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- MEMR Handbook of Energy & Economic Statistics of Indonesia (Final Edition). 2021. Available online: https://www.esdm.go.id/en/publication/handbook-of-energy-economic-statistics-of-indonesia-heesi (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- BPS Statistik Potensi Desa Indonesia 2021. Available online: https://www.bps.go.id/id/publication/2022/03/24/ceab4ec9f942b1a4fdf4cd08/statistik-potensi-desa-indonesia-2021.html (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Wibisono, H.; Lovett, J.C.; Anindito, D.B. The Contestation of Ideas behind Indonesia’s Rural Electrification Policies: The Influence of Global and National Institutional Dynamics. Dev. Policy Rev. 2023, 41, e12650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, D.F. Electric Power for Rural Growth: How Electricity Affects Rural Life in Developing Countries; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- DAGI. Consulting Monitoring & Evaluation Sumba Iconic Island Program 2018; DAGI Consulting: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Sovacool, B.K. Success and Failure in the Political Economy of Solar Electrification: Lessons from World Bank Solar Home System (SHS) Projects in Sri Lanka and Indonesia. Energy Policy 2018, 123, 482–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streimikiene, D.; Baležentis, T.; Volkov, A.; Morkūnas, M.; Žičkienė, A.; Streimikis, J. Barriers and Drivers of Renewable Energy Penetration in Rural Areas. Energies 2021, 14, 6452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Njoh, A.J.; Etta, S.; Ngyah-Etchutambe, I.B.; Enomah, L.E.D.; Tabrey, H.T.; Essia, U. Opportunities and Challenges to Rural Renewable Energy Projects in Africa: Lessons from the Esaghem Village, Cameroon Solar Electrification Project. Renew. Energy 2019, 131, 1013–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathis, W.; Listiyorini, E. A Solar Microgrid Brought Power to a Remote Village, Then Darkness. Bloomberg.com 2022. Available online: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/features/2022-03-24/challenges-of-a-solar-microgrid-project-in-indonesia (accessed on 31 May 2025).

- Wibisono, H.; Lovett, J.; Chairani, M.S.; Suryani, S. The Ideational Impacts of Indonesia’s Renewable Energy Project Failures. Energy Sustain. Dev. 2024, 83, 101587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singgih, V. Investors Abandoning Renewable Energy Projects in Sumba—Tue, 3 April 2018. Available online: https://www.thejakartapost.com/news/2018/04/03/investors-abandoning-renewable-energy-projects-sumba.html (accessed on 17 May 2024).

- Asghar, N.; Amjad, M.A.; Rehman, H.u.; Munir, M.; Alhajj, R. Achieving Sustainable Development Resilience: Poverty Reduction through Affordable Access to Electricity in Developing Economies. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 376, 134040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handayani, P.W.; Nasrudin, R.; Rezki, J.F. Reliable Electricity Access, Micro and Small Enterprises, and Poverty Reduction in Indonesia. Bull. Indones. Econ. Stud. 2024, 60, 35–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wassie, Y.T.; Adaramola, M.S. Socio-Economic and Environmental Impacts of Rural Electrification with Solar Photovoltaic Systems: Evidence from Southern Ethiopia. Energy Sustain. Dev. 2021, 60, 52–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haning, D.J.; Manna, E.M.; Firman, G. Pre-Feasibility Study: Microgrid Solar Solution for Indigenous Village (Kampung Adat) Ubu Oleta in Sumba Island, Indonesia. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Power and Renewable Energy Conference (IPRECON), Kollam, India, 24–26 September 2021; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Filho, G.L.T.; dos Santos, I.F.S.; Barros, R.M. Cost Estimate of Small Hydroelectric Power Plants Based on the Aspect Factor. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 77, 229–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanagawa, M.; Nakata, T. Assessment of Access to Electricity and the Socio-Economic Impacts in Rural Areas of Developing Countries. Energy Policy 2008, 36, 2016–2029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega, N.; Curto, A.; Dimitrova, A.; Nunes, J.; Rasella, D.; Sacoor, C.; Tonne, C. Health and Environmental Impacts of Replacing Kerosene-Based Lighting with Renewable Electricity in East Africa. Energy Sustain. Dev. 2021, 63, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.S.; Miah, M.D.; Hammoudeh, S.; Tiwari, A.K. The Nexus between Access to Electricity and Labour Productivity in Developing Countries. Energy Policy 2018, 122, 715–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chomać-Pierzecka, E.; Błaszczak, B.; Godawa, S.; Kęsy, I.; Chomać-Pierzecka, E.; Błaszczak, B.; Godawa, S.; Kęsy, I. Human Safety in Light of the Economic, Social and Environmental Aspects of Sustainable Development—Determination of the Awareness of the Young Generation in Poland. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IRENA. Off-Grid Renewable Energy Solutions; IRENA: Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ortega-Arriaga, P.; Babacan, O.; Nelson, J.; Gambhir, A. Grid versus Off-Grid Electricity Access Options: A Review on the Economic and Environmental Impacts. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 143, 110864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, X.; Zhong, J.; Chen, Y.; Shao, Z.; Jian, L. Grid Integration of Electric Vehicles within Electricity and Carbon Markets: A Comprehensive Overview. eTransportation 2025, 25, 100435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. BEYOND CONNECTIONS: Energy Access Redefined; The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development: Washington, DC, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bhattarai, P.R.; Thompson, S. Optimizing an Off-Grid Electrical System in Brochet, Manitoba, Canada. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 53, 709–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veldhuis, A.J.; Reinders, A.H.M.E. Reviewing the Potential and Cost-Effectiveness of off-Grid PV Systems in Indonesia on a Provincial Level. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 52, 757–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qoaider, L.; Steinbrecht, D. Photovoltaic Systems: A Cost Competitive Option to Supply Energy to off-Grid Agricultural Communities in Arid Regions. Appl. Energy 2010, 87, 427–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IRENA. Renewable Power Generation Cost in 2021; International Renewable Energy Agency: Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 2022; ISBN 978-92-9260-452-3. [Google Scholar]

- Numata, M.; Sugiyama, M.; Mogi, G. Barrier Analysis for the Deployment of Renewable-Based Mini-Grids in Myanmar Using the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP). Energies 2020, 13, 1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, V.G.; Bartolomé, M.M. Rural Electrification Systems Based on Renewable Energy: The Social Dimensions of an Innovative Technology. Technol. Soc. 2010, 32, 303–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouedraogo, N.S. Opportunities, Barriers and Issues with Renewable Energy Development in Africa: A Comprehensible Review. Curr. Sustain. Renew. Energy Rep. 2019, 6, 52–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wibisono, H.; Lovett, J.C.; Suryani, S. Expectations and Perceptions of Rural Electrification: A Comparison of the Providers’ and Beneficiaries’ Cognitive Maps in Rural Sumba, Indonesia. World Dev. Sustain. 2023, 3, 100102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fathoni, H.S.; Setyowati, A.B.; Prest, J. Is Community Renewable Energy Always Just? Examining Energy Injustices and Inequalities in Rural Indonesia. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2021, 71, 101825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Gevelt, T.; Zaman, T.; George, F.; Bennett, M.M.; Fam, S.D.; Kim, J.E. End-User Perceptions of Success and Failure: Narratives from a Natural Laboratory of Rural Electrification Projects in Malaysian Borneo. Energy Sustain. Dev. 2020, 59, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feron, S. Sustainability of Off-Grid Photovoltaic Systems for Rural Electrification in Developing Countries: A Review. Sustainability 2016, 8, 1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarker, S.A.; Wang, S.; Adnan, K.M.M.; Anser, M.K.; Ayoub, Z.; Ho, T.H.; Tama, R.A.Z.; Trunina, A.; Hoque, M.M. Economic Viability and Socio-Environmental Impacts of Solar Home Systems for Off-Grid Rural Electrification in Bangladesh. Energies 2020, 13, 679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nduka, E. How to Get Rural Households out of Energy Poverty in Nigeria: A Contingent Valuation. Energy Policy 2021, 149, 112072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumga, K.T.; Goswami, K. Willingness to Pay for Cooking with Electricity among Rural Households: The Case of Southern Ethiopia. Heliyon 2025, 11, e41343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chishimba, S.K.; Muchapondwa, E. Credit Constraints and Willingness to Pay for Electricity among Non-Connected Households in Zambia. Energy Sustain. Dev. 2025, 85, 101601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siyaranamual, M.; Amalia, M.; Yusuf, A.; Alisjahbana, A. Consumers’ Willingness to Pay for Electricity Service Attributes: A Discrete Choice Experiment in Urban Indonesia. Energy Rep. 2020, 6, 562–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, C.; Lovett, J.C.; Rianawati, E.; Arsanti, T.R.; Suryani, S.; Pandarangga, A.; Sagala, S. Household Willingness to Pay for Improving Electricity Services in Sumba Island, Indonesia: A Choice Experiment under a Multi-Tier Framework. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2022, 88, 102503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuch, M. Rural Electrification in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Willingness to Pay Analysis of Electricity Access in Kenya. Energy Policy 2025, 206, 114720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBEKA. n.d. PLTMH. Available online: https://ibeka.or.id/mhp-project/ (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Ibrahim, A.R. Factors Influencing Commercialization Phase of Social Innovation and Entrepreneurship; Delft University of Technology: Delft, The Netherlands, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ropo, R. Hadirnya PLTMH Kalilang, Warga Empat Desa di Kahaungu Eti Terang Benderang. Pos-kupang.com 2020. Available online: https://kupang.tribunnews.com/2020/02/04/hadirnya-pltmh-kalilang-warga-empat-desa-di-kahaungu-eti-terang-benderang (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Creswell, J.W. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009; ISBN 978-1-4129-6556-9. [Google Scholar]

- Kalof, L.; Dan, A.; Dietz, T. Essentials of Social Research; McGraw-Hill Education: New York, NY, USA, 2008; ISBN 978-0-335-23679-4. [Google Scholar]

- Aspers, P.; Corte, U. What Is Qualitative in Qualitative Research. Qual. Sociol. 2019, 42, 139–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atinkut, H.B.; Yan, T.; Arega, Y.; Raza, M.H. Farmers’ Willingness-to-Pay for Eco-Friendly Agricultural Waste Management in Ethiopia: A Contingent Valuation. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 261, 121211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, X.; Zhan, J.; Wang, C.; Hameeda, S.; Wang, X. Households’ Willingness to Accept Improved Ecosystem Services and Influencing Factors: Application of Contingent Valuation Method in Bashang Plateau, Hebei Province, China. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 255, 109925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghanbarpour, M.R.; Saravi, M.M.; Salimi, S. Floodplain Inundation Analysis Combined with Contingent Valuation: Implications for Sustainable Flood Risk Management. Water Resour. Manag. 2014, 28, 2491–2505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.; Xue, D.; Wang, B. Integrating Theories on Informal Economies: An Examination of Causes of Urban Informal Economies in China. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Liu, H.; Mao, X.; Jin, J.; Chen, D.; Cheng, S. Willingness to Pay for Renewable Electricity: A Contingent Valuation Study in Beijing, China. Energy Policy 2014, 68, 340–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stigka, E.K.; Paravantis, J.A.; Mihalakakou, G.K. Social Acceptance of Renewable Energy Sources: A Review of Contingent Valuation Applications. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014, 32, 100–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanemann, M.; Loomis, J.; Kanninen, B. Statistical Efficiency of Double-Bounded Dichotomous Choice Contingent Valuation. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 1991, 73, 1255–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bateman, I.J.; Burgess, D.; Hutchinson, W.G.; Matthews, D.I. Learning Design Contingent Valuation (LDCV): NOAA Guidelines, Preference Learning and Coherent Arbitrariness. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2008, 55, 127–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrow, K.; Solow, R.; Portney, P.; Leamer, E.; Radner, R.; Schumar, H. Report of the NOAA Panel on Contingent Valuation; National Oceanic & Atmospheric Administration: Washington, DC, USA, 1995.

- Veronesi, M.; Alberini, A.; Cooper, J.C. Implications of Bid Design and Willingness-To-Pay Distribution for Starting Point Bias in Double-Bounded Dichotomous Choice Contingent Valuation Surveys. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2011, 49, 199–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.S. Estimation of Option and Non-Use Values for Intercity Passenger Rail Services. J. Transp. Geogr. 2010, 18, 259–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakatani, T.; Aizaki, H. DCchoice: Analyzing Dichotomous Choice Contingent Valuation Data 2015, 0.2.0. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/DCchoice/DCchoice.pdf (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Aizaki, H.; Nakatani, T.; Sato, K.; Fogarty, J. R Package DCchoice for Dichotomous Choice Contingent Valuation: A Contribution to Open Scientific Software and Its Impact. Jpn. J. Stat. Data Sci. 2022, 5, 871–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JRI Research. Socio-Economic-Gender Baseline Survey; JRI Research: Sumba, Indonesia, 2012; pp. 1–123. [Google Scholar]

- Go, Y.L.; Kurniasa, M.; Potapova-Crighton, O.A.; Himayati, L.; Kumar, J. Treading Water in a Savannah: The Reality of Water Scarcity in East Sumba. 2020. Available online: https://rdiglobal.org/publications/view/3856/treading-water-in-a-savannah-the-reality-of-water-scarcity-in-east-sumba (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Fingleton-Smith, E. Blinded by the Light: The Need to Nuance Our Expectations of How Modern Energy Will Increase Productivity for the Poor in Kenya. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2020, 70, 101731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelz, S.; Aklin, M.; Urpelainen, J. Electrification and Productive Use among Micro- and Small-Enterprises in Rural North India. Energy Policy 2021, 156, 112401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngowi, J.M.; Bångens, L.; Ahlgren, E.O. Benefits and Challenges to Productive Use of Off-Grid Rural Electrification: The Case of Mini-Hydropower in Bulongwa-Tanzania. Energy Sustain. Dev. 2019, 53, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riva, F.; Ahlborg, H.; Hartvigsson, E.; Pachauri, S.; Colombo, E. Electricity Access and Rural Development: Review of Complex Socio-Economic Dynamics and Causal Diagrams for More Appropriate Energy Modelling. Energy Sustain. Dev. 2018, 43, 203–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. The Welfare Impact of Rural Electrification: A Reassessment of the Costs and Benefits; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2008; ISBN 978-0-8213-7367-5. [Google Scholar]

- Winther, T. The Impact of Electricity: Development, Desires and Dilemmas, 1st ed.; Berghahn Books: Brooklyn, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Haan, A.d.; Maxwell, S. Poverty and Social Exclusion in North and South. IDS Bull. 2017, 48, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popay, J. Understanding and Tackling Social Exclusion. J. Res. Nurs. 2010, 15, 295–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sievert, M.; Steinbuks, J. Willingness to Pay for Electricity Access in Extreme Poverty: Evidence from Sub-Saharan Africa. World Dev. 2020, 128, 104859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wibisono, H.; Suryani, S.; Safina, S. Entrepreneurial Tendency of Indonesia Remote Rural Communities: Are the Existence of Community-Based Mini-Grids Matters? J. Socioecon. 2024, 7, 205–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.