1. Introduction

With rapid societal development, cross-linked polyethylene (XLPE) cables have been widely used in power transmission and distribution systems, owing to their superior electrical performance and high operational reliability [

1,

2]. However, during actual installation, whether by direct burial or conduit laying, it is often difficult to completely avoid ingress of moisture or dampness [

3,

4]. If a small amount of water infiltrates and is fully absorbed by the water-blocking tape, forming a gel-like substance, the white powder precipitated after drying poses a potential threat to the safe operation of the cable [

5,

6]. Conversely, the intrusion of a large amount of water may diffuse into the main insulation and induce water treeing, thereby accelerating the aging and degradation of the insulating material and even leading to insulation breakdown and power supply interruptions [

7,

8]. Therefore, studying the changes in the insulation performance and parameter characterization of cables under damp conditions is of significant engineering importance.

Currently, there is abundant literature on research related to cable-moisture absorption. References [

9,

10] systematically analyzed the advantages and limitations of existing cable condition assessment methods, summarizing detection technologies mainly applicable to low-voltage cables or the local moisture absorption of high-voltage cables; however, a gap remains in the overall moisture absorption assessment of high-voltage cables. References [

11,

12] measured the dielectric loss characteristics of cables after water tree and electrical tree formation through experiments, and proposed that the low-frequency dielectric loss factor can be used as a criterion for faulty cables. References [

13,

14,

15] studied the performance and parameter changes in low-voltage moisture-affected cables using the polarization/depolarization current (PDC) method through different accelerated moisture absorption tests. Reference [

16] revealed the variation law of the insulation performance through constant-voltage load cycling tests. References [

17,

18] focused on cable moisture absorption localization methods, proposing cable body capacitance as a key variable characterizing the degree of moisture absorption by analyzing changes in cable performance and parameters after moisture absorption. Reference [

19] effectively evaluated the degree of cable moisture absorption by comprehensively measuring the insulation resistance, partial discharge, and polarization/depolarization current combined with the TOPSIS algorithm. References [

20,

21] mainly discussed the electric field distribution characteristics of cables under normal conditions and with defects. Reference [

22] proposed the use of frequency-domain spectroscopy (FDS) technology to assess the moisture content of XLPE cable insulation and found a monotonic increasing relationship between its dissipation factor and moisture content. However, this study only targeted the main insulation moisture absorption and did not establish a complete moisture absorption model for cable systems.

Most of the aforementioned studies on cable defects have focused on low-voltage cables; no research has been conducted on cables with water-blocking tapes. For high-voltage cables, research is limited to variations after shield ablation, water trees, electrical trees, and carbonization in the main insulation. No systematic conclusions have been drawn regarding the changes in electrical parameters during the three stages of cable moisture absorption (water-blocking tape moisture absorption, air-gap wetting, and XLPE main insulation moisture absorption). Additionally, there has been no detailed research on the impact of moisture content in the cable’s main insulation on its electrical performance. In this study, distorted electric fields were incorporated for different degrees of moisture absorption. Through joint experiments and simulations, it was concluded that the cable body capacitance, insulation resistance, and dielectric loss factor exhibited regular variations during the three moisture absorption stages. Furthermore, the moisture distribution in the main insulation of the cable has no significant effect on the dielectric loss and capacitance values of the cable.

2. Test Samples and Test Platform

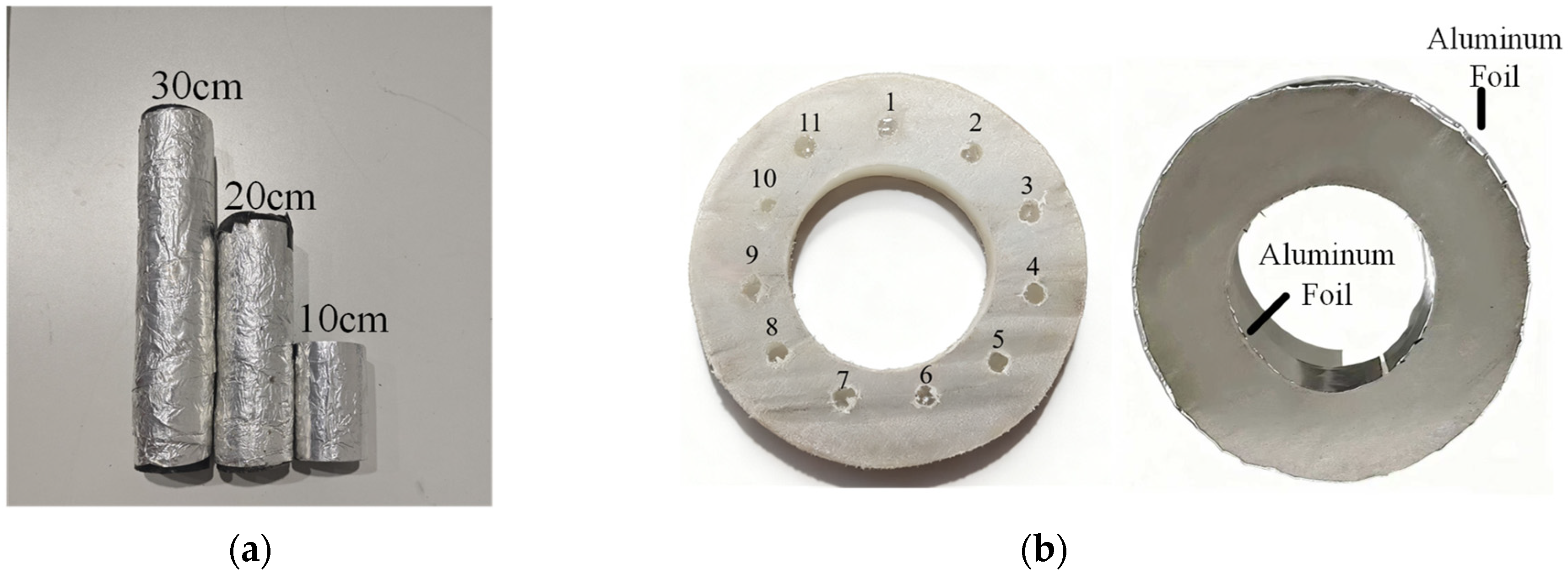

For the cable body, cross-linked polyethylene (XLPE) cables with lengths of 10, 20, and 30 cm (model: ZC-YJWO3-55/66 kV 1 × 500) were selected as the test samples, Chongqing Kebao Cable Co., Ltd. (Chongqing, China), as shown in

Figure 1. The outer sheath and aluminum sheath of the cables were stripped off and the cables were placed in a vacuum drying oven for moisture removal. The drying oven was set to 60 °C at a pressure of 0.01 MPa, and the drying process lasted for 3 h to ensure that the cables were restored to a dry state.

During the moisture simulation, efforts were made to ensure a uniform distribution of the water injection positions and volumes. The 10 cm-long cable was equipped with two moisture-affected points. To maintain the same moisture content across the three cables (10, 20, and 30 cm), the moisture content of the 20 cm and 30 cm-long cables was increased synchronously. The moisture content was characterized by the volumetric moisture content, defined as the ratio of the water volume to the volume of the cable body, set at 0.01%. Preliminary experiments revealed that, when the area around the moisture-affected points was compressed, the water-blocking tape absorbed 6–8 mL of water within 5 s. Therefore, 6 mL was used as the standard injection volume.

XLPE main insulation samples with thicknesses of 1 cm were used for the main insulation test. There are two schemes to characterize their moisture absorption status: one is to fully immerse the main insulation samples in water, which is called distributed moisture absorption, and the other is to drill holes on the sample surface and inject water (the moisture content per hole is 0.08 mL with a volumetric moisture content of 0.27%, which is called concentrated moisture absorption. The moisture intrusion scenario caused by the aluminum sheath damage of the cable was closer to the latter; therefore, the second moisture absorption scheme was adopted in this test, as shown in

Figure 1b. In addition, when measuring the sample capacitance, the inner and outer cylindrical surfaces were used as the two poles of the test, and aluminum foil was attached to each pole, as shown in

Figure 1b.

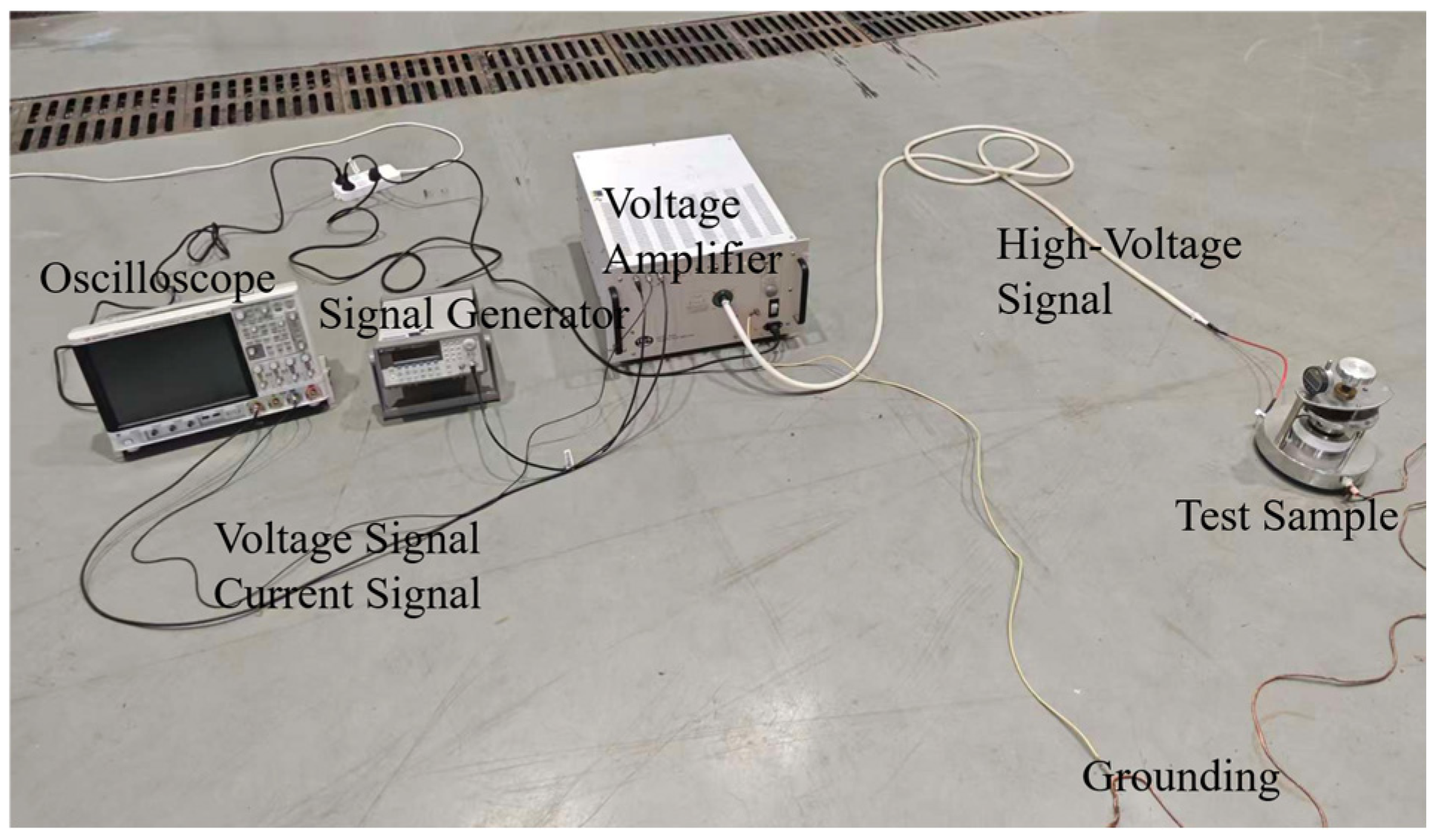

The dielectric-loss measurement circuit is illustrated in

Figure 2. The voltage signal generated by the signal generator (Keysight Technologies (Santa Rosa, CA, USA)) was modulated using a voltage amplifier (Advanced Energy (Trek brand) (Denver, CO, USA)), and then applied to the sample test terminal. The oscilloscope (Keysight Technologies (Santa Rosa, CA, USA)) detected the current and voltage signals of the voltage amplifier with a voltage frequency ranging from 0.01–15 Hz. When measuring the capacitance and insulation resistance, an E4990A impedance analyzer (Keysight Technologies, Santa Rosa, CA, USA) was used, with 256 test points and a frequency range of 20 Hz–10 kHz.

3. Analysis of Test Results

3.1. Test Results and Analysis of Cable Body

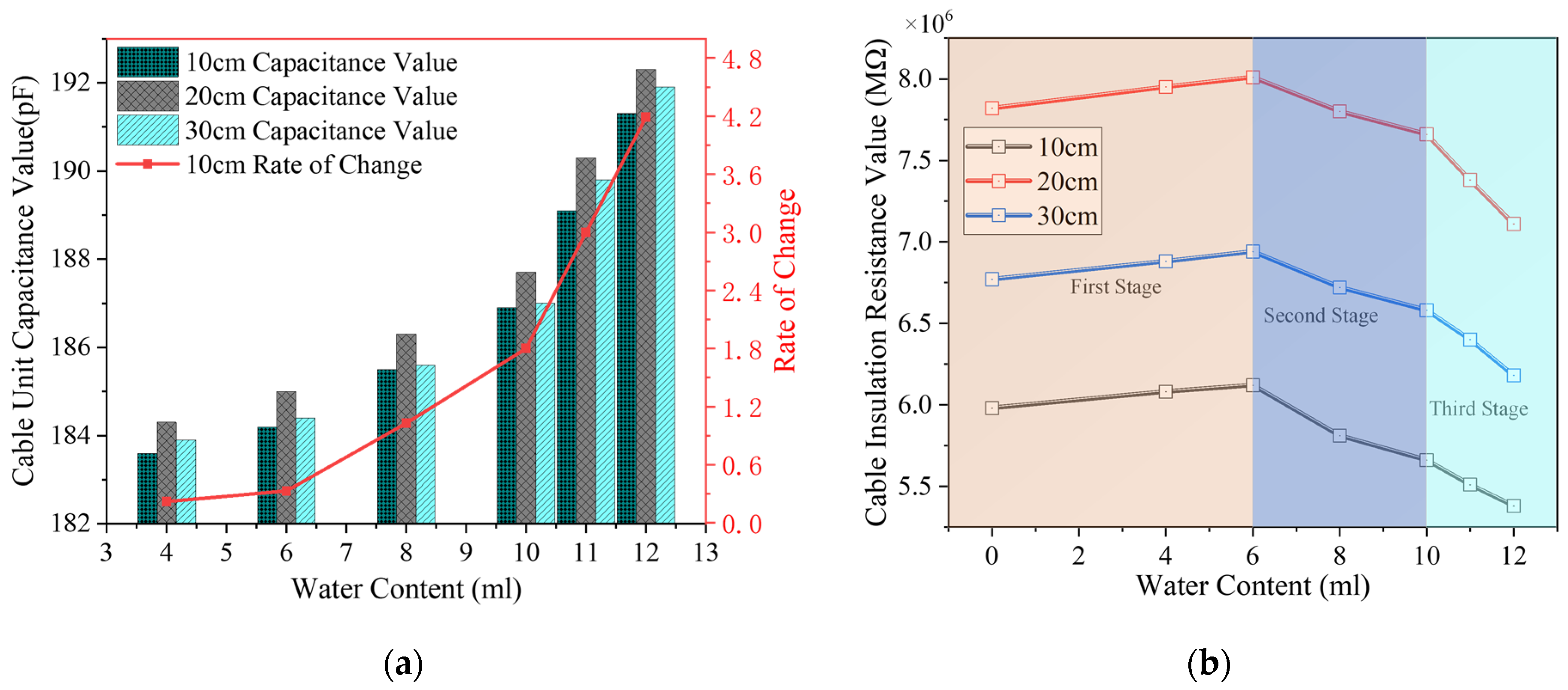

The measurement results of the cable body capacitance obtained by measuring the three cable samples shown in

Figure 1a are presented in

Figure 3a. The initial capacitance values of the 10 cm, 20 cm, and 30 cm cables are 183.2 pF, 183.9 pF, and 183.54 pF, respectively. In the first stage of moisture absorption, the water-blocking tape rapidly absorbed moisture, resulting in no significant change in cable-body capacitance. After the moisture content reached 6 mL, the cable entered the second stage of moisture absorption, which the capacitance increased steadily by approximately 0.7% for every additional 2 mL of moisture. An additional 1 mL of moisture from 11 mL to 12 mL led to moisture penetration into the main insulation, indicating a transition to the third stage of moisture absorption, at which point the capacitance surged sharply.

The insulation resistance test structure of the cable sample is illustrated in

Figure 3b. In the first stage of moisture absorption, the insulation resistance increased slightly as moisture gradually increased. When the moisture content was 6 mL, the insulation resistance increased by 2.34% compared to the initial value, which was due to the decrease in the conductivity of the water-blocking tape after absorbing moisture. In the second stage, the insulation resistance gradually decreased, and some of the moisture remained in the air gaps and displaced the air gaps, increasing the conductivity between the water-blocking tape and aluminum sheath, thus leading to a decrease in insulation resistance. When the moisture content reached 8 mL, the insulation resistance decreased significantly. For every additional 2 mL of water, its value decreased by approximately 2.75% compared to the initial value and approximately 5.1% compared to the end of the first stage. In the third stage, when moisture further invaded the main insulation layer of the cable, the insulation resistance decreased the most significantly, with the fastest decline rate. On average, for every additional 1 mL of water, the insulation resistance decreased by approximately 2.75%.

3.2. Test Results and Analysis of XLPE Main Insulation

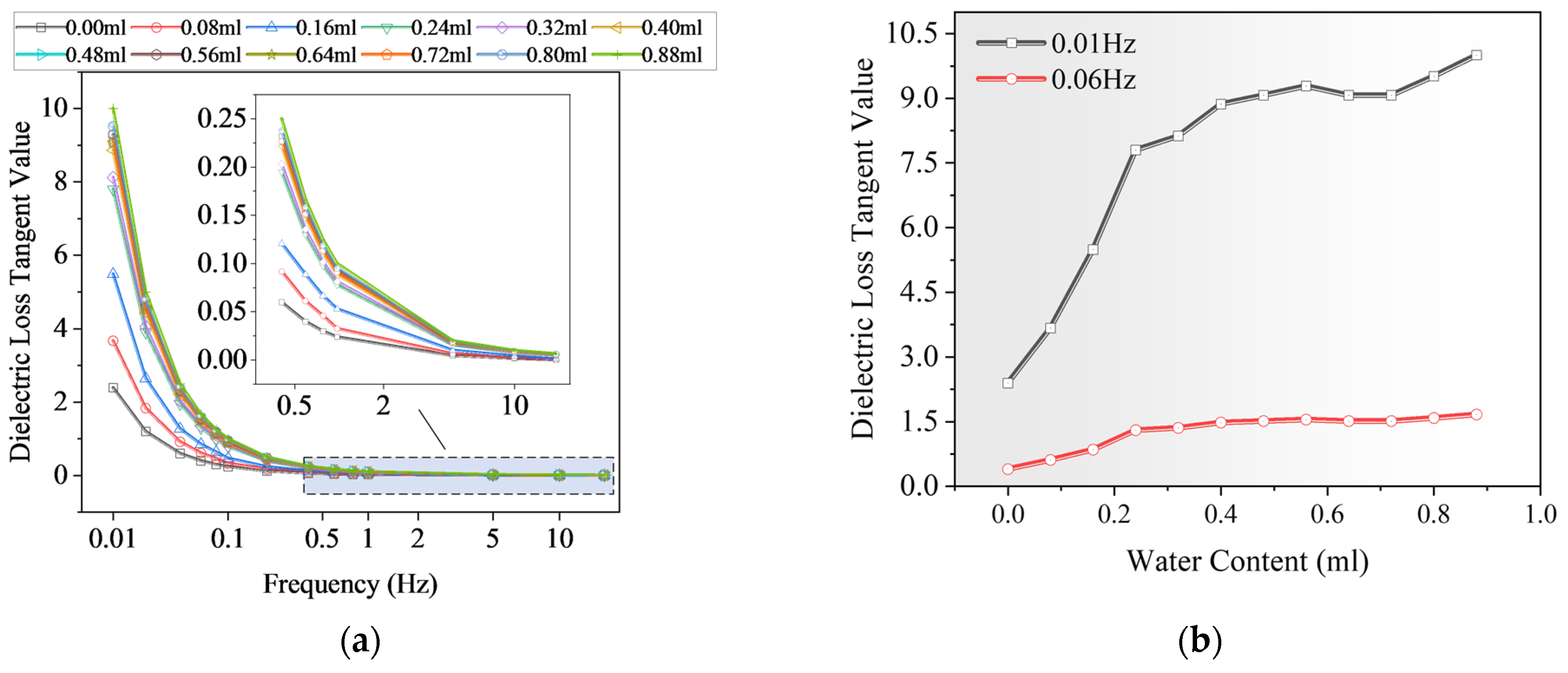

Figure 4 shows the dielectric loss values of the XLPE main insulation samples at a frequency of 15 Hz under the same moisture content but different distribution positions, and under different moisture contents but with the same distribution position. Regardless of whether the moisture absorption position was symmetric or uniform, there was no significant difference in the dielectric loss values at the different positions. However, as the moisture content increased, the dielectric loss value continued to increase, indicating that tan δ is mainly related to the moisture content and unrelated to the moisture absorption distribution position.

The curve shown in

Figure 5a was obtained by changing the moisture content further. The graph was plotted with a value of 15 Hz without moisture absorption as a reference. The tan δ value of the main insulation increased with decreasing frequency and increasing moisture content. At a frequency of 0.5 Hz, the dielectric loss value of the main insulation exhibits an approximately linear increase with the injection volume in the initial stage. However, when the moisture content is too high and affected by the distorted electric field caused by the expanded moisture, the measured results deviate from the theoretical simulation, and the linear relationship between the dielectric loss value and energy loss is no longer maintained. This is because there is a significant difference between the relative dielectric constants of XLPE and that of moisture. The continuous infiltration of moisture led to a continuous increase in the dielectric loss of the main insulation of the cable, thereby reflecting the deepening of the degree of insulation moisture absorption.

Figure 5b shows the influence of the moisture content on the dielectric loss at 0.01 Hz and 0.06 Hz. It can be observed that the dielectric loss at low frequencies was several times higher than that at high frequencies. Therefore, in actual on-site measurements, under the condition of filtering out external high-frequency interference signals, using a lower frequency makes it easier to detect the moisture absorption status of the main insulation of the cable and to determine its moisture absorption level.

In the experiment, the unit length capacitance of the main insulation was measured when the same moisture content was distributed at different positions, as shown in

Figure 6a. As shown in the figure, when the volumetric moisture content is the same, the capacitance value is independent of the moisture-affected position and is only related to the moisture content. Therefore, with the gradual increase in the moisture content in the cable insulation, the measured capacitance value of the XLPE cable main insulation increases by equal amounts with the increase in moisture content, as shown in

Figure 6b. When the moisture content increases by 0.08 mL, the measured average growth rate of the unit length XLPE capacitance was 0.79%.

4. Analysis and Demonstration of Staged Moisture Absorption of Cables

4.1. Analysis of Staged Moisture Absorption Mechanism of Cables

As mentioned in the previous experiments, the cable moisture absorption process can be divided into three stages according to the position of moisture intrusion, as shown in

Figure 7. After moisture invades the aluminum sheath, the water-blocking buffer layer first absorbs moisture, resulting in changes in its parameters. This is the first stage. Subsequently, the excess moisture continues to diffuse into the air gap between the aluminum sheath and the buffer layer, which is the second stage. If the aluminum sheath is severely damaged and a large amount of moisture invades it, it may diffuse into the main insulation (main insulation shield), which is the third stage.

In the first stage of moisture absorption, the permeation and distribution laws of moisture in the water-blocking tape are jointly determined by two mechanisms: moisture diffusion and adsorption in porous materials. Because moisture mostly invades the water-blocking tape vertically, this process can be characterized using the pseudo-second-order model, as shown in Equation (1). In the second stage of moisture absorption, the process involves interfacial flow and slow permeation-diffusion in capillary channels, which can be simulated using the Fick model, as shown in Equation (2). In the third stage of moisture absorption, the diffusion behavior of moisture in the main insulation of the cable leads to the generation of water trees. This phenomenon can be described based on Fick’s Second Law and semi-infinite medium assumption. Equation (2) is also applicable; however, the diffusion coefficient D differs from that in the second stage [

23]

In the equation, Qt is the adsorption capacity of the water-blocking tape at time t (mL); Qe is its maximum adsorption capacity (mL); k is the adsorption rate constant; t is time (s); C(x, t) is the moisture concentration in the air gap; x is the diffusion distance; D is the diffusion coefficient of moisture in the air gap, which is approximately 2.5 × 10−5 m2/s. During the third stage, the diffusion coefficient D is 10−10 m2/s. Qe (maximum equilibrium adsorption capacity) depends on the water-absorbing medium, which is 6 mL in this study.

Therefore, the moisture absorption stages of the cables are divided into three phases owing to the differences in the moisture diffusion mechanism. However, to reflect the parameter variation laws obtained in the experiments, it is necessary to simulate the moisture absorption at different axial positions of the cable, replicate the real state of the cable when the moisture absorption progresses to a specific stage in the experiment, and explore the evolution laws of the dielectric parameters and insulation performance at each moisture absorption stage.

4.2. Simulation Parameter Settings for Moisture-Absorbing Cables

Based on COMSOL Multiphysics 6.2 finite element simulation software, a 3D simulation model of the ZC-YJWO3-55/66 kV 1 × 500 cable was established. Fine mesh division was adopted, where the maximum and minimum element sizes are 0.2 cm and 0.01 cm, respectively. For the boundary conditions, a 38 kV phase voltage was applied to the cable core, and the aluminum sheath was grounded. The modeling diagram is shown in

Figure 8, and the cable parameters are listed in

Table 1 [

17,

18].

The moisture absorption of power cables can be divided into three distinct stages. Based on Equations (1) and (2), specific moisture absorption moments were selected within each stage to simulate the different moisture states of the cable. In the first stage of moisture absorption, different degrees of cable moisture are simulated by adjusting the electromagnetic parameters of the water-blocking tape. In the second stage, the degree of cable moisture was simulated by increasing the moisture volume in the air gap. In the third stage, the scenario in which moisture invades the main insulation was simulated using moisture droplets to occupy the position of the XLPE insulation.

In the finite element simulation software, the electric fields of the cable body and standalone XLPE main insulation were calculated using Equations (3)–(5). Through experiments investigating the electric fields before and after moisture ingress, the different laws exhibited by moisture ingress in the three stages were obtained. Furthermore, the capacitance values and insulation resistances of the cable body and XLPE main insulation were calculated using Equations (6) and (7).

where

denotes the electric potential,

and

are the boundary conditions of the field domain,

E is the electric field strength,

J is the current density,

σ is the material conductivity,

is the permittivity of free space,

is the relative permittivity, and

W is the electric energy per unit length of cable.

4.3. Analysis of Simulation Results for Moisture-Absorbing Cables

In the simulation process, the same moisture content as that of the test cables was used to investigate the variation in moisture absorption. The maximum electric field in the cable was simulated and calculated by adjusting the moisture content of the cable. The changes in the electric field strength within the cable indirectly verified the variation law of the three stages of the cable moisture absorption. As shown in

Figure 9, the maximum electric field values in the first, second, and third stages of moisture absorption were 3.69 × 10

6 V/m, 3.95 × 10

6 V/m, and 7.66 × 10

6 V/m, respectively. The electric field strength changes most drastically in the third stage, appearing in the water droplet areas of XLPE.

The simulated unit capacitance of the cable was calculated based on the computed electric field and simulation conditions. Owing to the uncertainty of the experiment, comparative values of the test capacitance were selected as the average of three cables with different lengths. In the simulation capacitance calculation results, the unit capacitance of the dry cable is 184.5 pF, and it increases to 184.9 pF after the water-blocking tape initially absorbs moisture. As the moisture content in the air gap increased, the unit capacitance of the cable increased accordingly, as shown in

Table 2. The last column of the table shows that the absolute difference in the change rates between the two is less than 0.07% and that the change rates are consistent.

During the insulation resistance calculation, the same moisture absorption degree as that of the test cables was used in the simulation to calculate the cable insulation resistance. Owing to the error in the test instruments, comparative values of the test resistance were selected as the average of three cables with different lengths. Although there were differences between the simulation and test results, the difference was controlled within 1.5%, which was within the range of normal errors. It can be observed from the results in

Table 3 that the variation trend of the cable body insulation resistance with the moisture absorption degree is consistent with the test results. The insulation resistance of the dry cable was 6.87 × 10

6 MΩ. As the moisture absorption degree continued to deepen, the insulation resistance between the cable core and the aluminum sheath increased, as shown in

Table 3. In the first stage, after moisture was absorbed by the water-blocking tape, the insulation resistance increased, which is consistent with the test results. In the second stage, with the deepening of moisture absorption, the water-blocking tape reached water absorption saturation, and when moisture appeared in the air gap, insulation resistance began to decrease. When the moisture content in the air gap exceeded 8 mL, the insulation resistance became lower than that of the dry cable, which is consistent with the test cable. In the third stage, after moisture continues to invade the main insulation, the insulation resistance decreases significantly. The absolute difference in the change rates in the three stages is less than 0.3%.

Figure 10 shows the electric field distribution of the cable insulation before and after moisture absorption when a 38 kV phase voltage is applied to the cable core and the outer ring is grounded. Before moisture absorption, the electric field was mainly concentrated near the cable core, and no local high-field-strength areas were formed. After the cable insulation absorbs moisture, the maximum electric field strength increases from 3.68 × 10

7 V/m (in the dry state) to 5.8 × 10

7 V/m. If the cable continues to operate after moisture absorption, local water treeing and electrical treeing will be generated at moisture-affected high field strength positions inside the cable insulation, impairing the cable insulation performance.

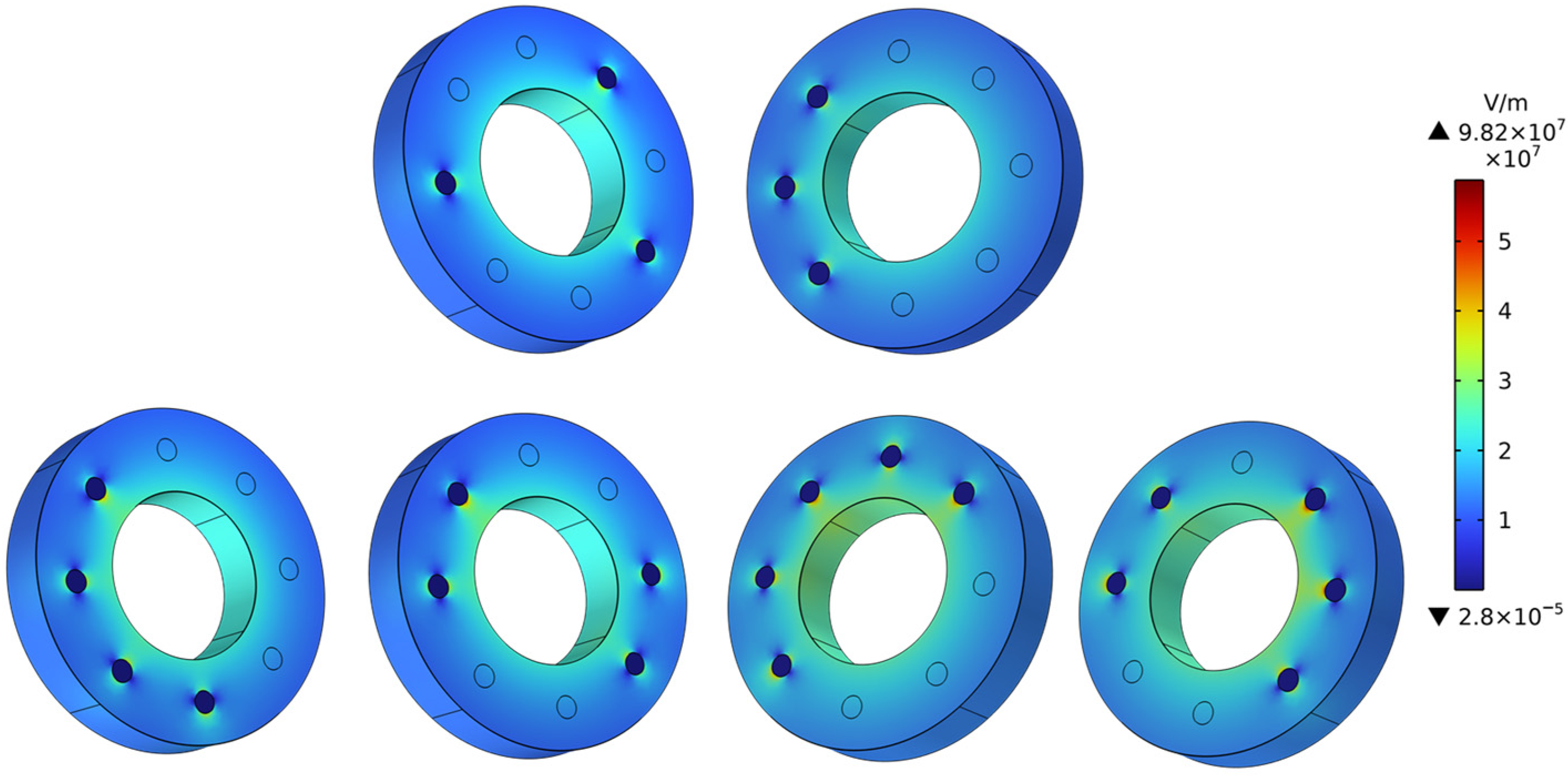

Figure 11 shows the electric-field distribution diagrams of the cable insulation after moisture absorption at different distribution positions. It can be observed that the maximum and minimum electric field values of the cable are essentially the same when they are subjected to accumulated moisture absorption or symmetric moisture absorption, and the electric field value gradually increases with the gradual intrusion of moisture.

Furthermore, the unit capacitance of the XLPE main insulation under the accumulated and symmetric distributions was calculated, as shown in

Figure 12a. It is observed that the capacitance values are essentially the same, regardless of the accumulated distribution or symmetric distribution. After moisture invades the cable insulation layer, owing to its high dielectric constant, it can produce a polarization effect under the action of an electric field, causing local electric field distortion and charge accumulation, as shown in

Figure 12b. The invasion of moisture increases the equivalent conductivity of the overall insulation structure and the dielectric loss. The variation law of the dielectric loss at 0.01 Hz is shown in

Figure 12b. As the degree of moisture absorption increases, the dielectric loss and insulation conductivity gradually increase. The insulation resistance of the cable was determined mainly by the XLPE insulation. Once moisture invasion occurs, the electric-field distribution, unit capacitance, and insulation resistance undergo significant changes. Therefore, the early stage of cable insulation moisture absorption should be identified in a timely manner, and measures should be taken to prevent further deterioration of the insulation performance, which is of great significance for online monitoring and early warning of cable insulation.

5. Conclusions

In this study, we conducted a systematic investigation of the insulation performance changes of 66 kV cables under different moisture absorption degrees. By combining experimental and simulation methods, the variation laws of parameters such as cable-body capacitance and insulation resistance were analyzed. The main conclusions are as follows.

(a) Based on experimental tests, the moisture absorption process of the cable body can be divided into three stages: water-blocking tape adsorption, air-gap wetting, and main insulation diffusion. When the moisture absorption degree increased by 0.02%, the body capacitance in the first stage increased by 0.3% and the insulation resistance increased by 0.87%. In the second stage, the body capacitance increased by 0.7%, the insulation resistance decreased by 1.9%, and the changes in the third stage were the most significant. When the moisture absorption degree increased by 0.01%, the cable body capacitance increased by 1.2% and the insulation resistance decreased by 3.7%. The dielectric loss and capacitance values of the XLPE main insulation were only related to the degree of moisture absorption and were independent of the moisture-affected position.

(b) By analyzing the mechanism of moisture diffusion, the different intrusion processes of moisture in the cable body lead to differences in the cable’s moisture absorption process. Simulations were conducted with the same moisture absorption degree as in the experiments to analyze the variation characteristics of the three moisture absorption stages. The results indicated that the difference in the moisture absorption growth rate of the body capacitance between the simulation and experiment was within 0.07%, and the difference in the insulation resistance change rate was within 0.3%. Similarly, the main insulation of the XLPE is related only to the degree of moisture absorption. Therefore, in engineering applications, the stage variation characteristics of the parameters can be used to determine the degree of moisture absorption in the cables.

Author Contributions

Methodology, S.L.; Validation, G.Z.; Investigation, G.Z.; Writing—original draft, G.Z.; Writing—review & editing, S.L.; Visualization, G.Z.; Project administration, S.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to internal management.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Zhao, X.; Wu, H.; Yang, D.; Wei, J.; Li, Z.; Guo, Z.; Zhang, S. Residual Magnetism Elimination Method for Large Power Transformers Based on Energy Storage Oscillation. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2025, 40, 2759–2768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhong, L. Evaluation of voltage endurance characteristics for new and aged XLPE cable insulation by electrical treeing test. IEEE Trans. Dielectr. Electr. Insul. 2019, 26, 72–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Gu, X.; Su, X.; Zhou, Q.; Li, K.; Song, J. Research on Fault Diagnosis Model of Feeder System in Rail Transit Distribution Network Based on Improved 1D-CNN. China Railw. Sci. 2025, 46, 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Wu, G.; Wang, J.; Xing, Y.; Yao, C.; Li, K. Fault diagnosis method for transformer winding deformation based on frequency response reconstruction and digital image processing. High Volt. Eng. 2025, 51, 4599–4609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Chen, J. Electro-thermal Field Analysis and Simulated Ablation Experiments for the Water-blocking Buffer Layer in High Voltage XLPE Cable. J. Chin. Electr. Eng. Sci. 2022, 42, 1260–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suo, C.; Cao, H.; Chern, W.; Ghias, A.M.Y.M. Application of pdc testing for medium-voltage XLPE cable joint water ingress detection. IEEE Trans. Dielectr. Electr. Insul. 2025, 32, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Wei, J.; Zhao, X.; Wu, H.; Yang, D.; Li, Z.; Zhang, S. Research on Elimination Method of Residual Magnetism in Large Power Transformers Based on Energy Storage Oscillation. Proc. CSEE 2025, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Wu, G.; Yang, D.; Xu, G.; Xing, Y.; Yao, C.; Abu-Siada, A. Enhanced detection of power transformer winding faults through 3D FRA signatures and image processing techniques. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2025, 242, 111433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, B.; Li, S.; Yang, X.; Wang, W.; Li, C. Key problems faced by defect diagnosis and location technologies for XLPE distribution cables. Trans. China Electrotech. Soc. 2021, 36, 4809–4819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yu, J.; Ma, M. Performance Evolution and Aging Mechanism of XLPE Insulation for HVdc Cables After Different Accelerated Aging. IEEE Trans. Dielectr. Electr. Insul. 2025, 32, 1074–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Y.; Zhao, P.; Hui, B.; Cheng, Y.; Zhu, W.; Fu, M.; Li, X. Broadband impedance spectrum detection of buffer layer defects in 110 kV crosslinked polyethylene cable with corrugated aluminium sheath. High Volt. 2023, 8, 967–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Yan, S.; Wang, S.; Zhang, M.; Li, S. Evaluation of electrical tree aging state of XLPE cable based on low-frequency high-voltage frequency domain dielectric spectrum. Trans. China Electrotech. Soc. 2023, 38, 2510–2518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maur, S.; Chakraborty, B.; Pradhan, A.K.; Dalai, S.; Chatterjee, B. Relaxation Frequency Distribution Based Approach Toward Moisture Estimation of 11 kV XLPE Cable Insulation. IEEE Trans. Dielectr. Electr. Insul. 2024, 31, 3261–3268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, H.; Wang, X.; Suo, C.; Ghias, A.M.Y.M. A data analytic approach for assessing XLPE cable insulation condition via resistance measurements. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2025, 74, 3528112–3528123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, Z.; Liang, Z.; Yao, H. Condition assessment of XLPE cable insulation based on improved fractional zener model. IEEE Trans. Dielectr. Electr. Insul. 2023, 31, 1499–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Chen, J.; Jia, Z.; Lu, G.; Fan, W.; Guan, Z. Study About Insulating Properties of 10 kV XLPE Damp Cable. Power Syst. Technol. 2014, 38, 2875–2880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, G.; Pan, S.; Lu, L.; Meng, P.; Liu, Z.; Wang, X.; Zhou, K. Electromagnetic Time Reversal Localization Method for Distribution Cables Based on Reflection Coefficient Modification. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2025, 72, 6497–6506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Duan, P.; Zhou, K.; Rao, X.; Gao, Y.; Peng, Z.; Huang, S. A Cable Defect Localization Method Based on Multiresolution Singular Value Decomposition and Stochastic Subspace Identification. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2024, 73, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, S.; Luan, L.; Xu, Z.; Fan, W.; Cui, Y.; Xv, S. Research on Damping Process of XLPEDistribution Network Cables Based on Comprehensive Electrical Performance Evaluation. Insul. Mater. 2022, 55, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, H.; Zhong, L.; Yang, X.; Li, W.; Gao, J.; Yu, Q.; Chen, X.; Li, Z. Electric field distribution based on radial nonuniform conductivity in HVDC XLPE cable insulation. IEEE Trans. Dielectr. Electr. Insul. 2020, 21, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meziani, M.; Mekhaldi, A.; Teguar, M. Space Charge and Associated Electric Field Distribution in Presence of Water Trees in XLPE Insulation Under DC and AC Voltages. IEEE Trans. Dielectr. Electr. Insul. 2025, 32, 1343–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, A.K.; Chatterjee, S.; Pradhan, A.K.; Chatterjee, B.; Dalai, S. Estimation of moisture content in XLPE cable insulation using electric modulus. IEEE Trans. Dielectr. Electr. Insul. 2022, 29, 1030–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, H.; Cheng, L.; Liu, Y.; Yang, L.; Liao, R. Effect of Electric Field on Water Absorption and Permeability Characteristics of Silicone Rubber. IEEE Trans. Dielectr. Electr. Insul. 2024, 31, 1169–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |