Abstract

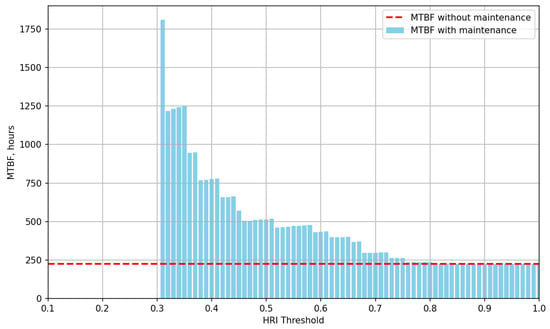

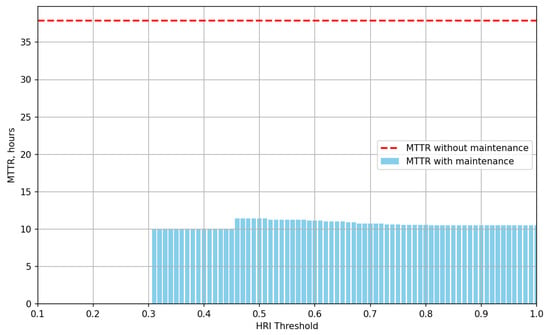

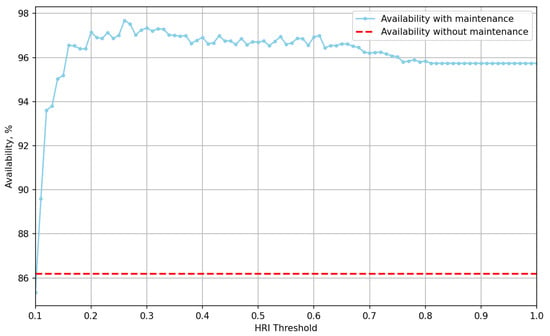

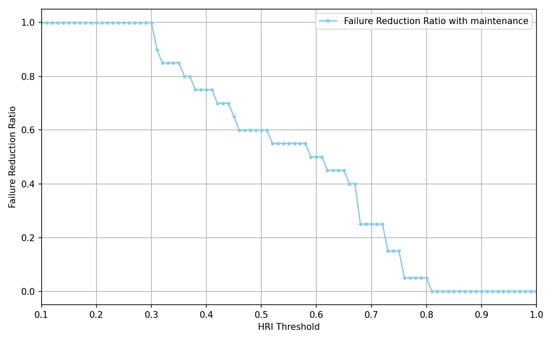

The growing demand for energy-efficient and sustainable manufacturing requires maintenance strategies that extend beyond reliability optimization toward active energy management. This study proposes a Smart Hybrid Maintenance System (SHMS) that integrates Reliability-Centered Maintenance (RCM) and Condition-Based Maintenance (CBM) principles with energy performance assessment. The framework combines classical reliability indicators (MTBF, MTTR, and Availability) with energy-oriented Key Performance Indicators (EEI, EENS, and OEE) to quantify the relationship between machine degradation, operational availability, and energy efficiency. The methodology was validated using two datasets: NASA N-CMAPSS for simulation-based benchmarking and the Smart RDM industrial environment for real process data. Results demonstrate that predictive maintenance supported by the Hybrid Risk Index () reduces unplanned downtime by up to 12%, corresponding to a 7–9% decrease in specific energy consumption and a measurable improvement in the Energy Efficiency Index. By embedding energy metrics into predictive maintenance decision-making, the SHMS enables dual optimization of reliability and energy performance. The proposed approach not only enhances equipment availability and cost efficiency but also supports industrial decarbonization targets, positioning predictive maintenance as a key enabler of energy-aware and sustainable manufacturing aligned with Industry 5.0 objectives.

1. Introduction

1.1. Energy Efficiency as a Driver of Predictive Maintenance Strategies

In modern industry, energy efficiency has become a strategic factor linking operational performance, economic competitiveness, and environmental sustainability. The manufacturing and energy sectors account for a major share of global energy consumption, and even small improvements in efficiency translate into measurable reductions in operating costs and greenhouse gas emissions. Maintenance engineering plays a crucial yet often underestimated role in this context. Studies demonstrate that the degradation of technical systems, process instability, and unplanned downtime generate hidden energy losses that can reach 10–20% of total plant energy consumption [1,2]. Therefore, maintenance policies must increasingly account not only for reliability and cost but also for their impact on overall energy performance.

A pioneering study introduced the concept of integrating energy efficiency indicators into Condition-Based Maintenance (CBM) decision-making [1]. Using the Energy Efficiency Indicator (EEI)—the ratio between useful output and energy input—it was shown that maintenance actions triggered by a decline in energy efficiency can significantly reduce both energy losses and maintenance costs in manufacturing systems. This framework redefined maintenance from a purely reliability-driven activity into a key element of energy management.

Several studies extend this perspective by coupling predictive maintenance with machine learning and sustainability-oriented optimization [3]. Data-driven models can identify energy inefficiencies before they escalate, and modern Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) architectures can predict component degradation and enable energy savings—by up to 9% in compressed air systems and over 12% in hot rolling mills—through improved control of radiator and motor operation cycles [4,5]. These examples confirm that energy-aware predictive maintenance is no longer theoretical but increasingly a practical tool for industrial optimization.

In the energy sector, condition-based and reliability-centered maintenance have proven to be particularly effective in reducing unplanned stoppages and associated energy waste [6]. Integrated CBM and RCM models for offshore wind turbines optimize maintenance schedules to minimize expected energy not supplied (EENS) and thereby increase total power output. A similar approach applied to steam boiler systems showed that optimized maintenance intervals based on reliability indicators reduced fuel consumption and improved overall thermal efficiency by nearly 6% [7]. These results highlight that predictive maintenance is not only about asset health but is also directly tied to energy productivity and emissions reduction.

Complementary research underscores the role of digitalization and data analytics in achieving energy savings through maintenance optimization [8]. Frameworks that integrate Big Data mapping with predictive models support maintenance decisions balancing performance and energy consumption. Likewise, holistic approaches to asset management that include energy performance as a lifecycle criterion for decision-making emphasize that sustainable maintenance requires considering both technical reliability and the energy footprint of assets throughout their operation [9].

Energy-driven maintenance optimization has also been explored through mathematical modeling. An energy consumption-based optimization approach allows for the selection of maintenance strategies that minimize total energy use and greenhouse gas emissions [10]. Aligning maintenance timing with low-energy operating periods can yield up to 38% savings in total energy-related costs, providing a strong quantitative foundation for incorporating energy efficiency into maintenance policy design.

At the component and system monitoring level, recent advances in IoT and AI enhance energy-aware diagnostics [11]. Explainable deep learning frameworks for predictive maintenance of air compressors are capable of linking degradation patterns to energy performance in real time, achieving both improved model transparency and measurable energy savings. Similarly, IoT-based energy-efficient CBM frameworks for Industry 4.0 applications demonstrate that integrating energy-related features into predictive models can reduce overall energy waste while maintaining equipment reliability [12].

The importance of such strategies is further reinforced by reviews of diagnostic methods for electrical equipment, which conclude that predictive analytics and condition monitoring significantly contribute to energy-efficient system operation by reducing unplanned downtime and extending equipment lifecycles [2].

Taken together, these studies converge on the conclusion that predictive and condition-based maintenance are not only reliability management tools but also crucial enablers of energy efficiency and sustainability. By leveraging data analytics, IoT sensing, and machine learning, PdM systems can detect degradation early, optimize energy use, and synchronize maintenance with production and demand profiles.

In the context of this work, we extend these principles by developing a hybrid predictive maintenance framework that integrates reliability-centered maintenance with energy performance indicators to enhance both equipment availability and energy efficiency. This approach aligns with the broader objective of smart industrial systems—maximizing operational performance while minimizing energy intensity and environmental impact.

The integration of predictive maintenance with energy management principles has therefore become a natural progression in industrial optimization strategies. While Section 1.1 established energy efficiency as a key driver of maintenance transformation, the following part elaborates on how predictive maintenance (PdM) methods directly contribute to achieving this objective through data analytics, reliability modeling, and process automation.

Specifically, this work contributes to (i) an energy-aware hybrid PdM framework (RCM + CBM) operationalized via the Hybrid Risk Index, (ii) a methodology to quantify energy impacts through EEI/EENS/OEE linkages, and (iii) a comparative evaluation on benchmark and industrial datasets highlighting measurable availability and energy-performance gains.

1.2. Predictive Maintenance as a Tool for Energy Optimization

Predictive Maintenance (PdM) has emerged as a transformative paradigm in modern industrial operations, fundamentally reshaping how organizations approach equipment reliability and operational efficiency. In an increasingly competitive global manufacturing landscape, industries face constant pressure to maximize productivity, minimize downtime, and reduce operational expenditures. This has accelerated the transition from reactive to proactive maintenance strategies, driven by advances in the Industrial Internet of Things (IIoT), big data analytics, and artificial intelligence (AI) [13]. The application of PdM extends across numerous industrial sectors, including manufacturing, energy, transportation, and healthcare. The core tasks of predictive models include the prediction of failure events, estimation of the Remaining Useful Life (RUL) of critical components, and the enhancement of production performance through downtime reduction. These objectives are accompanied by challenges such as data heterogeneity, the need for sophisticated data models, difficulties in result interpretation, and scalability limitations. Addressing these challenges requires the integration of digital twins and machine learning algorithms with physical reliability models [14].

PdM represents a maintenance strategy based on continuous monitoring of the actual technical condition of equipment and forecasting failures before breakdowns occur. In contrast to Preventive Maintenance (PM), PdM is inherently data-driven, relying on sensors, analytical models, and machine learning [13]. Such data are used to forecast when a failure is likely to happen, allowing maintenance to be performed only when truly necessary [15]. This approach reduces both maintenance costs and downtime, while improving resource utilization and extending asset lifespan. However, the implementation of PdM requires the development of advanced data infrastructure and monitoring systems, making it more complex and resource-intensive to deploy.

It should be noted that PdM and PM are closely interrelated—not as competing, but as complementary approaches within an integrated maintenance strategy. PdM adds an analytical and predictive layer to maintenance operations. Frequently, data collected as part of PM programs, such as failure histories or inspection cycles, are utilized in predictive models for downtime forecasting. Therefore, PdM can be considered the next evolutionary step in enterprise maintenance maturity. In practice, deploying such advanced methods is feasible only when a sufficient and reliable dataset is available [16].

A key aspect of PdM is the prediction of failures and the planning of maintenance activities based on actual asset condition data, rather than on rigid time-based schedules. To achieve this, a structured sequence of steps is typically employed, encompassing data acquisition, analysis, and interpretation. In particular, the following stages can be distinguished [16,17]:

- Identification of critical assets;

- Data acquisition;

- Development of a consistent data model;

- Data flow design and storage architecture;

- Data preprocessing;

- Implementation of predictive algorithms and model training;

- Evaluation of PdM process performance through KPI calculation;

- Visualization and interpretation of results;

- Decision-making and execution of maintenance actions;

- Continuous process improvement.

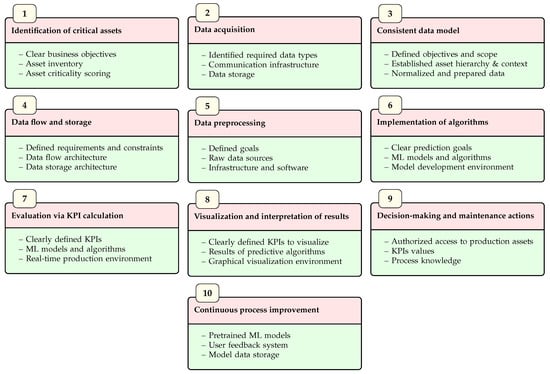

Figure 1 presents a data flow diagram illustrating the implementation and operation of a PdM system. Each stage of the PdM deployment process is represented by a distinct block. Within each block, a specific activity is defined, together with the required data and resources necessary for the successful execution of subsequent steps.

Figure 1.

Stages of PdM process deployment.

A properly functioning PdM system requires the execution of several data engineering tasks to prepare an appropriate dataset. In general, it is necessary to collect information concerning process parameters and associated events. This includes sensor measurement data, records of events and downtimes, as well as inspection and repair histories, which enable characterization of the lifecycle of individual machines or their components. Additionally, information on defined operational conditions—such as duty cycles, load levels, and nominal parameters—is essential. A well-prepared machine inventory, including machine types, categories, and operational times, is also a prerequisite.

Data requirements may vary depending on the applied methodology. For example, when Condition-Based Maintenance (CBM) is employed, process data are of primary importance. Machine learning models, in turn, can be enhanced with information about downtimes, failures, or other historical events. The development of a digital twin, on the other hand, requires design data necessary to construct a digital representation of a machine and subsequently feed it with historical operational data.

It should be emphasized that the use of a single data model may not yield satisfactory results. Therefore, it is recommended to combine various modeling approaches and develop a hybrid system. Recent research has demonstrated significant progress in the construction and application of health indicators (HIs) for predictive maintenance. Feature-level fusion methods combined with stochastic degradation modeling have been shown to improve RUL prediction accuracy and support cost-driven maintenance optimization, as exemplified by the KPCA–DAE framework proposed by Chen et al. [18]. In parallel, recent studies emphasize the integration of HIs within digital twin architectures, where HIs serve as key enablers of monitoring, diagnostics, and prognostics, enhancing system transparency and uncertainty awareness [19].

While these approaches significantly advance health assessment and prognostic capabilities, maintenance decisions are typically derived from RUL estimates, threshold-based rules, or external optimization layers. In contrast, the approach proposed in this work explicitly operates at the decision level. By integrating reliability-based survival analysis with condition-based anomaly assessment into a unified Hybrid Risk Index, and by introducing the Optimal Maintenance Point as a formally defined decision construct, the proposed framework directly links health assessment to maintenance action selection. This distinction enables the transition from descriptive and prognostic indicators toward an operational, risk-aware maintenance decision-making paradigm.

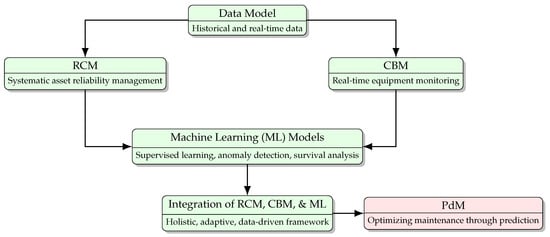

In this context, we introduce the Smart Hybrid Maintenance System (SHMS)—a comprehensive framework that integrates the principles of Reliability-Centered Maintenance (RCM) and CBM. RCM provides a structured methodology for identifying and managing critical assets based on their functions and failure consequences, while CBM leverages real-time sensor data and continuous monitoring to assess equipment condition [20]. The SHMS architecture enhances these traditional approaches by incorporating machine learning (ML) techniques, enabling predictive modeling based on both historical failure data and live operational inputs [21]. A schematic overview of the SHMS architecture is provided in Figure 2 (see also [22]).

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of the Smart Hybrid Maintenance System (SHMS).

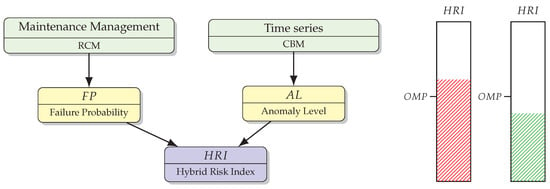

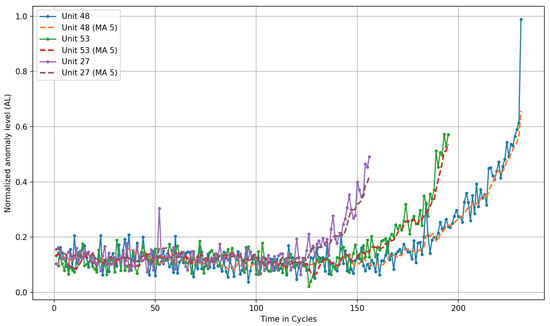

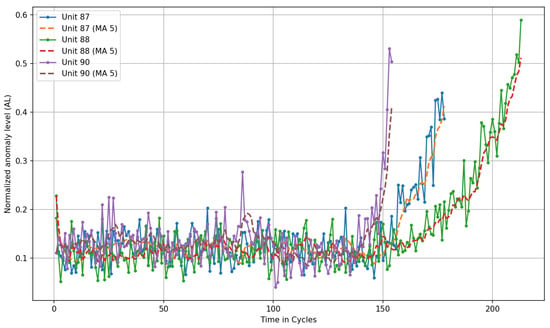

At the core of SHMS lies the Hybrid Risk Index (), a composite Key Performance Indicator (KPI) that quantifies failure risk. The integrates two components: Failure Probability (), derived from statistical reliability models, and Anomaly Level (), calculated using AI/ML models detecting deviations from expected behavior. Time series data from condition monitoring (CBM) and maintenance management systems (RCM) are used to calculate and , which are then combined into the . The is normalized on a scale from 0 to 1, allowing for continuous monitoring of risk levels and informed maintenance decisions (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Conceptual representation of the Hybrid Risk Index () construction.

The computation of combines historical failure patterns, operating profiles, real-time condition monitoring data (e.g., temperature, vibration, current), predictive model outputs, and expert knowledge from maintenance personnel. This hybridized perspective ensures that both data-driven predictions and human expertise are incorporated into maintenance decision-making.

In practice, serves as a decision-support mechanism, enabling maintenance teams to assess equipment condition in both nominal and actual operational contexts. It supports timely intervention by identifying early signs of degradation, improving asset availability, and aligning maintenance activities with reliability policies.

Another key concept introduced within SHMS is the Optimal Maintenance Point (), which defines the point in a system’s lifecycle where maintenance is most economically and operationally advantageous. It is characterized by a combination of increasing failure probability and a cost–benefit balance where the expense of preventive action is lower than the potential cost of downtime or failure.

Determining the requires operational experience, cost analysis, and understanding of equipment criticality in terms of production, quality, and safety. The supports a balanced approach—avoiding both premature maintenance (leading to unnecessary cost) and delayed action (resulting in failures and unplanned downtime). The bar plots in Figure 3 visualize levels with risk zones highlighted by pattern-filled regions.

SHMS is designed not as a black-box model but as an interpretable, context-aware solution reflecting the operational realities of a specific facility. It relies on predefined thresholds and rules derived from organizational standards and accumulated domain expertise. These setpoints convert sensor readings into actionable insights and trigger appropriate maintenance actions. The system incorporates operator input and expert feedback, fostering a human-centric maintenance paradigm where AI augments, rather than replaces, human decision-making.

The success of predictive maintenance initiatives such as SHMS depends strongly on the availability, quality, and contextual relevance of data. Historical records—failure logs, maintenance interventions—form the foundation for model training. Contextual data on load, environment, and utilization improve the interpretability of real-time signals [13,23]. Data deficiencies—such as incompleteness, noise, or poor integration—can impair model performance, leading to missed detections or false alarms [24]. Robust data acquisition and integration frameworks are therefore essential prerequisites for effective PdM.

Within this data-centric context, digital twins have emerged as powerful enablers of PdM. By creating high-fidelity virtual representations of physical assets, digital twins support real-time synchronization, scenario simulation, and advanced diagnostics, enhancing proactive maintenance and process optimization [24].

One of the most significant benefits of PdM is its impact on Overall Equipment Effectiveness (OEE)—a metric encompassing availability, performance, and quality dimensions. Originally introduced by Nakajima [25] within the Total Productive Maintenance (TPM) framework, OEE remains a cornerstone of performance measurement [26,27,28]. In the era of digital transformation, OEE serves as a baseline indicator for assessing progress and guiding maintenance investment priorities [29].

PdM directly improves OEE by minimizing unplanned downtime, optimizing resource utilization, and enhancing product quality [30]. It is often implemented in combination with Autonomous Maintenance (AM), where operators perform routine inspections and minor maintenance tasks. This decentralized approach increases responsiveness and ownership [25]. When effectively integrated, PdM and AM create a mutually reinforcing system that strengthens reliability and operational excellence [26].

To fully realize the potential of SHMS and PdM, organizations must prioritize digitalization—automating data collection, deploying integrated systems, and ensuring real-time process visibility [29]. Such digital infrastructure not only enables predictive and autonomous maintenance but also fosters continuous improvement, data-driven decision-making, and strategic alignment between operational and enterprise objectives.

In this paper, we present the SHMS framework, describing its theoretical foundation, data-driven architecture, and integration of domain expertise with operator knowledge. The SHMS is applied to a simulated real-world manufacturing environment, where the configuration of the is demonstrated based on historical data and operational scenarios. The effectiveness of the system is evaluated through a comparative study, analyzing operational outcomes between a machine equipped with SHMS and one without predictive maintenance functionality. This analysis demonstrates the practical advantages of SHMS in enhancing reliability, reducing costs, and improving overall operational performance. As predictive maintenance systems mature, their integration with reliability-centered approaches becomes essential to ensure both operational resilience and sustainable energy performance. The next section introduces the RCM framework, emphasizing its complementary role in aligning equipment reliability with the objectives of energy efficiency and optimized resource utilization.

1.3. Reliability-Centered Maintenance (RCM)

1.3.1. Introduction to RCM

RCM represents a sophisticated process through which organizations systematically identify and manage physical assets essential for their production processes with respect to reliability [31]. This comprehensive methodology enables organizations to develop and implement strategies that maintain equipment at optimal operational levels while balancing reliability requirements with resource constraints. The framework integrates multiple maintenance approaches, including Preventive Maintenance, Corrective Maintenance (also termed reactive maintenance), and Proactive Maintenance, to enhance the probability that equipment and components will function as required throughout their design lifecycle while minimizing maintenance requirements and downtime. These fundamental maintenance strategies are not implemented in isolation but rather integrated systematically to leverage their respective advantages, thereby maximizing facility and equipment reliability while optimizing lifecycle costs [32].

The fundamental principle of RCM is predicated on the optimization of maintenance decision-making processes to maximize equipment longevity while concurrently minimizing associated maintenance expenditures. The implementation of an RCM system typically engenders a multitude of significant advantages. These benefits encompass enhanced cost-effectiveness through the judicious scheduling of maintenance activities, augmented equipment uptime and operational reliability, improved comprehension and management of operational risks, and more efficacious allocation of maintenance resources. This multifaceted approach to maintenance strategy not only contributes to the overall operational efficiency but also fosters a proactive stance towards equipment management, thereby mitigating potential failures and their consequent economic implications.

In addition to its impact on reliability and cost, RCM also contributes directly to improving the energy efficiency of industrial systems. Properly timed maintenance actions prevent machines from operating under suboptimal conditions—such as increased mechanical resistance, leakage, or misalignment—that lead to excessive energy consumption. As shown in [10], integrating energy consumption into maintenance policy optimization can yield energy cost reductions of up to 38%, while [7] demonstrated that RCM-based scheduling in boiler systems reduces fuel usage and enhances thermal efficiency by nearly 6%. Thus, energy-aware RCM enables organizations to align reliability objectives with sustainable energy management goals, creating measurable benefits in both economic and environmental dimensions.

The successful implementation of RCM-based maintenance decisions necessitates the development of a comprehensive data model that monitors equipment reliability [33]. This sophisticated framework requires extensive manufacturer specifications and lifecycle data derived from equipment technical documentation, alongside detailed equipment failure histories and downtime records that encompass both unplanned failures and scheduled maintenance activities [20]. The model must incorporate component interdependency data analyzed through Failure Tree Analysis (FTA) methodology, enabling systematic evaluation of failure propagation paths and critical system vulnerabilities [32]. Furthermore, the framework demands continuous updates of failure cause analyses to maintain current understanding of equipment degradation patterns and failure modes. This is complemented by comprehensive maintenance action catalogs that document all possible intervention strategies and their historical effectiveness in addressing specific failure modes [34]. The integration of these diverse data categories creates a robust foundation for implementing effective RCM strategies while enabling data-driven decision-making in maintenance operations.

The implementation framework necessitates a sophisticated data model comprising three primary components. The first component is a comprehensive relational database encompassing historical maintenance records, equipment context data, and system-wide downtime analytics. The second component consists of an advanced asset hierarchy system, which incorporates several critical elements: Weibull distribution-based failure probability estimations, manufacturer specifications and operational parameters, time series KPI data such as OEE, failure cause analytics, current and planned maintenance activities, and probability and risk thresholds. The third component is a dedicated relational database designed to store predictive model outputs, maintenance recommendations, preventive maintenance schedules, and service action correlations.

This comprehensive framework facilitates the implementation of data-driven maintenance strategies that optimize equipment reliability while minimizing operational costs [35]. The integration of these components establishes a robust system for managing maintenance activities throughout the entire equipment lifecycle, enabling organizations to make informed decisions based on a holistic view of their assets’ performance and maintenance requirements. The key benefits of adopting the RCM approach include cost optimization through efficient maintenance planning, increased equipment reliability resulting in reduced downtime, improved risk management by identifying and mitigating potential failures and effective resource allocation by focusing maintenance efforts where they deliver the highest value.

1.3.2. Application of the Weibull Distribution to Reliability Analysis

Reliability engineering is a discipline that integrates statistical methods, risk analysis, and the physical understanding of failure mechanisms to estimate, prevent, and manage system failures. By analyzing the causes and patterns of past failures, it is possible to more accurately predict the future behavior and lifespan of systems and components, thereby supporting effective lifecycle management and risk mitigation. Due to conceptual similarities between the lifecycle of technical systems and biological lifespans, the methodologies of survival analysis are often employed in reliability engineering [36,37].

The Weibull distribution analysis is widely used in reliability engineering to model the time to failure of products and technical systems. Due to its flexibility, the distribution can take various shapes depending on the parameter values, allowing for accurate representation of different phases of an asset’s lifecycle—from early failures, through periods of stable operation, to failures caused by natural wear and aging [38,39]. Based on historical data, it is possible to forecast the time instant at which a certain fraction of components fails which is crucial for warranty planning and maintenance strategy development. The analysis of the model’s parameters also enables the identification of dominant failure mechanisms, providing deeper insight into the root causes of defects. This knowledge supports the creation of effective preventive maintenance plans by allowing interventions to be scheduled at the most optimal time—before costly breakdowns occur [40]. Additionally, the Weibull distribution is applicable in the general assessment of system and component reliability, making it a particularly valuable tool in industries that demand high levels of availability and operational safety [41,42,43,44].

The Weibull distribution is used to predict reliability-related events because it is flexible, easy to interpret, and effectively describes different phases in the lifecycle of technical systems and components. Its key advantage lies in the ability to model different types of failures by changing the shape parameter [45,46]. When , the distribution describes so-called early failures, typical for the “infant mortality” period of a system. In the case of , the failure rate remains constant, corresponding to the exponential distribution and modeling random, chance failures. When , the Weibull distribution models an increasing failure rate due to aging and wear of components. This makes the Weibull distribution well-suited for describing the entire lifecycle of a device—from manufacturing defects, through stable operation, to wear-out failures.

An additional advantage of the Weibull distribution is the intuitive interpretation of its parameters: describes the nature of changes in failure risk over time, while (the scale parameter) indicates the so-called characteristic life, i.e., the time at which approximately 63.2% of the population has failed [47]. The Weibull distribution fits empirical data very well across various domains—from industry and energy to transport and information technology. It also supports the analysis of censored data, i.e., observations where not all items have failed, which is common in reliability testing [48].

Moreover, the Weibull distribution enables accurate estimation of the reliability function, hazard rate, mean time to failure (MTTF), and confidence intervals for life parameters. Its structure is also consistent with the methods used in survival analysis, which supports the analogy between technical systems and biological organisms. Due to these properties, the Weibull distribution is one of the fundamental tools in reliability engineering.

Fitting data to the Weibull distribution is a key step in reliability analysis and lifetime prediction of technical systems. In practice, three estimation approaches are most commonly used: the maximum likelihood estimation (MLE), the least squares method (LSQ), and confidence interval-based methods.

MLE is considered the most accurate and widely used technique for estimating parameters in the context of the Weibull distribution. It involves finding the parameter values that maximize the likelihood function, i.e., the probability of obtaining the observed data assuming a specific distribution form. MLE has several advantages, including the ability to handle censored data, statistical efficiency, and favorable asymptotic properties. Although the likelihood function for the Weibull distribution does not have a closed-form solution, numerical solutions can be obtained using iterative methods [45,48].

An alternative to MLE is LSQ. In the case of the Weibull distribution, it involves transforming the cumulative distribution function (CDF) into a linear form, enabling the use of linear regression to estimate distribution parameters. This approach fits a straight line to points based on a logarithmic transformation of the data and empirical CDF estimation. LSQ is intuitive and easy to implement; however, its main drawbacks are the inability to directly handle censored data and lower accuracy compared to MLE [49]. In practice, LSQ is often used as a preliminary method for parameter estimation.

Complementary to both of the above methods are confidence interval-based approaches, which are used to assess the uncertainty of the estimated distribution parameters and to interpret model fitting. Once estimation is complete, it is possible to compute confidence intervals for the shape parameter and the scale parameter , as well as for reliability functions, hazard rates, or characteristic times such as the median time to failure. These intervals are typically derived using the asymptotic distribution of the estimators (usually normal) or through numerical methods such as bootstrapping [47,48]. Their use not only allows for estimating the potential prediction error but also facilitates the comparison of Weibull distributions across different data groups or equipment types.

One of the aspects of reliability prediction is the issue of right-censored data. This is a common phenomenon that occurs when complete information on the time to failure is not available for all units. Such censoring occurs when it is only known that a given unit did not fail by the end of the observation period, but the exact time of failure remains unknown. In practice, this means that the actual lifetime is greater than the observed time.

In the context of estimating the parameters of the Weibull distribution, accounting for right-censored data is important because failing to include this information may lead to significant errors in estimating the distribution parameters, such as the shape parameter and the scale parameter . The MLE method is the most widely used and statistically justified estimation technique in the presence of censoring. For mixed data containing both complete observations (known time to failure) and censored observations (unknown time to failure), the likelihood function L takes the following form:

where is the observation time, is the censoring indicator ( for a failure, for a censored observation), is the Weibull probability density function, and is the reliability function.

Incorporating censoring allows all available information in the data to be utilized. Censored observations are not ignored but treated as incomplete data that still contribute significantly to the estimation. MLE in this form can only be solved numerically, but widely available statistical tools (e.g., packages in Python 3.14, R 4.5.2, MATLAB 25.1, as well as commercial software such as Minitab 22 or Weibull++ 2025) allow for automatic inclusion of censored data in the estimation process [48,49].

In addition to MLE, some graphical methods and linear regression on Weibull plots can be adapted to handle censored data, although their accuracy and flexibility are limited compared to the maximum likelihood method. Furthermore, accounting for censoring is also essential when determining confidence intervals for the estimated parameters, as uncertainty is typically greater when some of the data do not contain complete information [47]. Proper inclusion of censored data in the process of estimating the parameters of the Weibull distribution, especially using the maximum likelihood method, is crucial for obtaining reliable and statistically valid results.

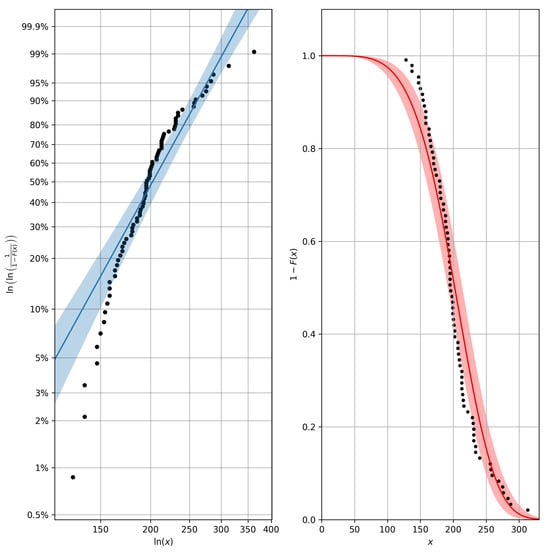

The following steps should be performed to properly conduct an analysis based on the Weibull method [50,51]:

- Collect information on the number of operational cycles (e.g., hours) for individual machines and/or their components.

- Sort the operational cycle data in ascending order.

- Assign a probability value to each observation in the failure dataset.

- Determine the double-logarithmic probability measure and the logarithm of the number of cycles.

- Estimate the parameters of the Weibull distribution using linear regression.

After preparing the dataset, the next step is to determine the number of operational cycles or hours of service of the analyzed machine or component prior to failure. To ensure statistical reliability, the dataset should include a sufficiently large number of failure instances. The data are then arranged in ascending order according to the number of cycles, and each observation is assigned an ordinal rank. Based on this ranking, the cumulative probability (P) of failure for each case is estimated, most commonly using the median rank (MR) method [50,51].

The probability value P (for ) can be expressed as the solution of the cumulative binomial equation with respect to the variable Z, which defines the unreliability associated with the j-th observation [52]:

where N is the total number of elements (cases) in the sample, and j is the ordinal number of the observation.

In practice, instead of solving the binomial equation directly, Benard’s approximation is typically applied to estimate the median rank:

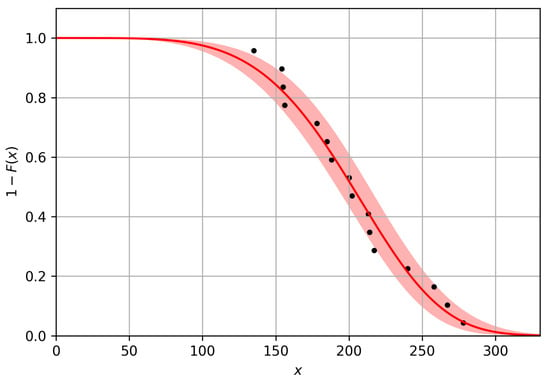

After calculating the median ranks, the empirical data can be fitted to the theoretical Weibull cumulative distribution function, which is given as follows [50]:

where x—number of cycles, and —distribution parameters.

The parameters and of the above equation are determined by using the following formulas [51]:

where , , .

These parameters are most often estimated using the maximum likelihood or the least squares method. Once these coefficients are determined, applying the inverse transformations yields the values of and that define the fitted Weibull cumulative distribution function.

In addition, for a known cumulative distribution function , it is possible to determine the survival function, which represents the probability of survival without failure until a given number of cycles x. It is defined as follows:

where —probability density function and t—integral variable. The probability density of failure occurrence can thus be determined using the derivative of the cumulative distribution function.

1.4. Key Performance Indicators Used for PdM Process Scoring

PdM acts as a protective layer against unnecessary downtime, as early detection of degradation symptoms (e.g., vibration anomalies, temperature deviations, current fluctuations, or abnormal process profiles) enables maintenance activities to be shifted from emergency interventions to planned maintenance windows. This approach reduces the number of unplanned stoppages, directly contributing to schedule stability and improving key performance indicators of production processes. The relationship between PdM effectiveness and process performance lies in the fact that early fault detection and optimized maintenance scheduling maximize equipment availability, minimize downtime duration and costs, and enhance overall system reliability [13,53,54]. In the context of evaluating PdM results, both reliability indicators and operational process KPIs are important. The first group includes MTTR and MTBF, whose definitions and data collection rules are described in ISO 14224 [54]:

where —total downtime duration, —operating time, —number of repair events, —number of failures.

Another metric used within PdM is system availability (A). It is defined as the percentage of time during which the asset is ready for operation. In the case of repairable systems, in steady-state conditions, it is directly linked to MTBF and MTTR through the following formula:

When calculated based on data from an observation window, the empirical form of Equation (13) can be used:

The second group includes the OEE indicator, defined in ISO 22400 as the product of Availability, Performance, and Quality [53].

The relation between PdM and process performance can be made visible through the analysis of so-called “avoided failures”, which involves comparing data from the period before implementation (baseline) with data after PdM deployment. This includes, among others, the number and duration of downtimes, repair costs, and counterfactual estimates of what would have happened if the alert had not been generated. Industry studies and reports typically report 30–50% downtime reduction and 20–40% increase in component lifetime, directly influencing Availability and OEE; individual case studies indicate approximately ∼25% reduction in unplanned stoppages in specific production cells [13,55,56]. It should be noted, however, that PdM effectiveness depends on data quality, the level of false alarms, and the criticality of monitored assets. In situations where the cost of preventive downtime is high, and the predictability of signals is low, it is recommended to consider alternative strategies such as CBM or advanced diagnostics/ATS, combined with portfolio management of maintenance strategies [55].

One of the parameters that can be used to assess the effectiveness of PdM in the context of operational safety is the Failure Rate of Safety-Critical Components (). This metric defines the frequency of failures of system elements that are critical to the safe operation of the system. It is defined as the ratio of the number of failures of components deemed safety-critical () to the total number of such components in the system (), according to the following formula:

This indicator is used to assess the reliability of systems where a failure could have serious consequences for people, the environment, or property, such as in aviation, nuclear power, railway transport, or the chemical industry. Since it concerns only the highest-priority safety elements, its monitoring enables precise identification of areas requiring special supervision and the determination of priorities for maintenance and preventive actions. When combined with Failure Mode and Effects Analysis (FMEA), or its extended version—Failure Mode, Effects, and Criticality Analysis (FMECA)—as well as RCM methods, the indicator enables the assessment of the effectiveness of implemented safety measures. Values close to zero indicate a very low failure rate of critical components and a high level of safety, while high values indicate frequent failures of key elements, requiring immediate corrective action.

Another parameter that can be used to evaluate the effectiveness of PdM in the context of operational performance is the Failure Reduction Ratio (). This metric defines the relative decrease in the number of failures in the current period compared to a baseline period, allowing a direct assessment of the impact of predictive or preventive measures. It is calculated according to the following formula:

where is the number of recorded failure events in the baseline period, and is the number of failure events in the current period. The indicator is particularly useful in determining the quantitative effect of implemented PdM strategies, modernizations, or process optimizations on system reliability. High values indicate a significant reduction in failures, which translates into improved equipment availability, reduced downtime costs, and higher OEE. Low or negative values, in turn, suggest the need to review maintenance strategies, as the implemented actions did not achieve the expected improvement in failure rates.

The effectiveness of the PdM strategy should be evaluated based on a set of indicators covering both reliability and operational aspects. On one hand, measures such as MTBF, MTTR, or system availability make it possible to determine the impact of PdM on machine uptime stability and downtime minimization; on the other, indicators such as OEE allow the linking of predictive maintenance results to business outcomes and productivity. Complementing this analysis are metrics dedicated to high-risk areas, such as , which focus on operational safety and the reliability of critical components, as well as , which quantifies the reduction in the number of failures between the baseline and current periods, providing a direct measure of reliability improvement and downtime cost savings. The combined use of these measures provides a complete picture of PdM effectiveness, enabling both the optimization of maintenance schedules and the rational allocation of maintenance resources based on actual safety and performance priorities.

1.5. Condition-Based Maintenance Framework

CBM represents an advanced maintenance strategy that leverages sensor technology and data analytics to monitor equipment performance in real-time [20]. This approach utilizes sophisticated monitoring equipment to collect comprehensive performance data, which is then analyzed through machine learning and artificial intelligence algorithms to detect patterns and anomalies indicative of potential maintenance requirements [13]. Beyond reliability, CBM frameworks are increasingly recognized as a foundation for energy-efficient operation. Continuous condition monitoring allows for early identification of operating states associated with excess energy use—such as compressor leakage, unbalanced loads, or inefficient control cycles—thus preventing unnecessary energy waste. Studies have shown that explainable AI-based monitoring of air compressors can reduce electrical consumption while maintaining performance [11], and that IoT-enabled CBM strategies significantly improve overall energy utilization in smart manufacturing environments [12]. Incorporating such feedback into CBM algorithms enables the dynamic optimization of equipment performance and directly supports the reduction of the facility’s total energy footprint. Therefore, CBM serves as both a diagnostic and an energy management tool, where early identification of energy-intensive operating states allows not only for reliability improvement but also for tangible reductions in energy consumption and CO2 emissions.

The integration of CBM with predictive maintenance methodologies significantly enhances system capabilities through the incorporation of sophisticated machine learning models for failure prediction and survival analysis [32]. A successful implementation of this integrated approach requires comprehensive data collection across multiple domains. The system must incorporate detailed manufacturer specifications and lifecycle data obtained from technical documentation, which provides baseline performance parameters and operational constraints. This is complemented by extensive historical failure and downtime records that capture the equipment’s past performance patterns and maintenance history. Critical to the system’s predictive capabilities is the continuous collection of time series sensor data monitoring operational parameters, providing real-time insights into equipment health and performance variations. The framework also necessitates a continuously updated failure cause analysis database that helps in understanding the root causes of equipment malfunctions and their progression patterns. Additionally, a comprehensive maintenance action catalog must be maintained, documenting all possible intervention strategies and their historical effectiveness in addressing specific failure modes [34]. This multi-faceted data infrastructure enables the development of robust predictive models that can accurately forecast potential failures and optimize maintenance scheduling.

Advancements in ML and IIoT technologies have revolutionized predictive maintenance systems, enabling sophisticated real-time monitoring and advanced analytical capabilities. Modern sensor networks, when integrated with state-of-the-art data analytics platforms, allow organizations to continuously monitor equipment health parameters, predict potential failures with remarkable accuracy, and dynamically optimize maintenance schedules based on real-time operational data [34]. This transition from conventional fixed-interval maintenance strategies to data-driven predictive methodologies has resulted in significant operational benefits. For example, Ref. [57] highlights that the adoption of ML and IoT-driven predictive maintenance has been instrumental in achieving substantial reductions in both downtime and operational costs across multiple industries. Specifically, companies leveraging these technologies report average reductions in unexpected downtime of 30–40% and maintenance cost savings of 20–30%.

The integration of ML and IIoT technologies facilitates a deeper understanding of equipment behavior and failure patterns through comprehensive data analysis. By combining the methodical reliability analysis of RCM with the real-time monitoring capabilities of CBM, organizations can implement highly targeted maintenance strategies that optimize resource allocation while minimizing operational disruptions [58]. The use of machine learning algorithms, particularly supervised models such as random forests and deep neural networks, enhances these systems by enabling continuous learning from historical data, which in turn improves predictive accuracy over time [33]. This adaptive learning capability, combined with real-time sensor data analysis, provides maintenance teams with actionable insights, empowering them to undertake proactive interventions. Consequently, these advancements have fundamentally transformed traditional maintenance paradigms, paving the way for highly efficient, data-driven predictive frameworks [21].

1.5.1. Application of Clustering Methods for Anomaly Detection and Failure Prediction

Data clustering represents a sophisticated data analysis technique aimed at partitioning datasets (represented as points in multidimensional feature space) into groups (clusters) such that objects within the same group exhibit maximum similarity while objects from different groups demonstrate maximum dissimilarity [21]. As an unsupervised machine learning approach, clustering operates without requiring labeled data for training, testing, or model evaluation. The most prominent clustering methods include the following [35,59]:

- k-means clustering [33,60,61]: This widely adopted clustering method partitions data into k clusters through iterative assignment of points to the nearest cluster centroid, followed by centroid updates.

- Hierarchical Clustering [62,63]: This algorithmic approach constructs a cluster hierarchy, progressing from individual points to increasingly larger clusters. Implementation variants include agglomerative (bottom-up merging) or divisive (top-down splitting) approaches.

- Density-Based Spatial Clustering of Applications with Noise DBSCAN [36,64,65]: This methodology clusters points based on density distributions, identifying high-density regions as clusters while classifying points in low-density regions as noise.

- Spectral Clustering [66,67]: This sophisticated approach employs linear algebra techniques for dimensionality reduction and cluster identification through eigenvalue analysis of similarity matrices.

1.5.2. Machine Anomaly Detection Using Clustering Algorithms

Building on the clustering concepts introduced in the previous section, unsupervised clustering is here employed to model normal operating states and quantify deviations from them for anomaly detection. In the present framework, clustering serves as a mechanism for defining reference operating regions in the multidimensional feature space.

As a representative example, the k-means algorithm is briefly outlined below to illustrate the clustering-based anomaly detection procedure.

Consider a set of observations: , , …, , where each observation represents a d-dimensional vector. The k-means algorithm partitions these n observations into sets: . The algorithm proceeds through the following steps [33]:

- Initialization: Choose k initial cluster centroids (this can be done randomly).

- Point Assignment: Assign each data point to the nearest cluster centroid, typically using Euclidean distance as the measure of proximity.

- Centroid Update: Recalculate the centroids of the clusters as the mean of all points assigned to each cluster.

- Iteration: Repeat steps 2 and 3 until convergence, i.e., when cluster assignments no longer change significantly.

In the case of unsupervised algorithms, the data used are unlabeled, meaning that information about failures is partially or entirely unavailable during training. In such scenarios, the following procedure can be applied, utilizing various clustering algorithms (e.g., the k-means algorithm).

- Define the state space as the space encompassing all possible signal values. For instance, if data is collected from two sensors, the state space will be two-dimensional; if data is collected from five sensors, it will be five-dimensional.

- Define a subspace that contains only the combinations of signal values representing correct machine operating states. It is assumed that during proper operation, all signal value combinations belong to . This implies that the machine is functioning correctly if the current state lies within . Conversely, if the state does not belong to , it is classified as an anomaly (incorrect state). Additionally, the degree of anomaly is measured as the distance of the current state from the subspace . It is assumed that is a metric space with a specified metric (e.g., Euclidean distance).

- Define an analytical representation of as a collection of clusters. Multiple valid operating states may exist in the multidimensional feature space . Using a defined membership function, each data point/state in is assigned to a specific cluster. Model training primarily involves determining this membership function.

- Acquire new data/machine states and determine their position in the state space relative to clusters representing valid operating states. The distance between the current state and the nearest cluster is then calculated; this metric is referred to as Anomaly Level, . If the state lies within a cluster, the distance is zero; if it lies outside, the anomaly severity increases with the distance.

- Determine the extent to which the distance projected onto each individual feature contributes to the overall distance. This allows for the identification of the causes of the anomaly or the features with the most significant impact on the anomaly.

1.6. The Concept of a Hybrid Model

The hybrid model enables the integration of indicators determined within the CBM methodology with the assessment of failure probability obtained from the RCM methodology. This allows the creation of a solution combining two models—one based on failure history and the other on current and forecast anomaly levels. Such an approach can significantly extend the capabilities of both unsupervised models, used for anomaly detection and prediction, and supervised models aimed at estimating failure probability. To effectively implement predictive maintenance based on the hybrid model, it is necessary to monitor environmental conditions (e.g., using sensor data) and analyze historical data on failures and operating cycles of individual components, including information from ERP/CMMS systems.

The following section presents the concept of a hybrid model for determining the probability of failure with the inclusion of the CBM approach (CBM component) and RCM approach (RCM component). Two variants of input assumptions are described. In the first variant, it is assumed that the ranges of process or environmental variable values for which failure is certain or almost certain (failure ranges) are unknown. In such a case, the CBM component related to anomalies is determined using the Bray–Curtis measure [68] to calculate the normalized distance between points in the state space, followed by applying a sigmoidal mapping function. In the second variant, the ranges are assumed to be known—in this case, the CBM component is determined using a linear mapping function with saturation.

In both variants, the current failure probability and its forecast are calculated as the weighted average of the CBM and RCM components. These weights can be set arbitrarily (e.g., considering the sensitivity of the indicator to individual components) or optimized within a given objective function. In the proposed solution, the weights were determined based on the confidence level of the component estimators, which increases the influence of the component with lower uncertainty and reduces the influence of components with higher uncertainty.

Moreover, by integrating energy-related parameters such as power consumption, load variability, and thermal profiles into the hybrid model, the SHMS can directly correlate degradation patterns with energy performance, making it possible to quantify the energy savings resulting from predictive interventions. The CBM component of failure risk can be considered in two scenarios. In the first case, when no information about the critical value is available, an n-dimensional state space is considered, containing all possible values of n signals:

The distance between any elements in the space can be determined using an appropriate metric . Assuming no knowledge of the critical values associated with the failure state (a value whose exceedance means certain occurrence of failure), it is assumed that the distance between the current and healthy state can take any value. In the further part of this work, it is assumed that the CBM risk component is related to the distance between the current state and the state defined as correct. For this purpose, a normalized Bray–Curtis dissimilarity measure is applied:

This distance is normalized to the range , and then transformed using a sigmoidal function to obtain a unified risk measure :

where a and b—the minimum and maximum values of the input variable x, respectively; c and d—the minimum and maximum values of the output variable y; k—parameter determining the steepness of the curve. Assuming , , , , and , we obtain:

In the second case, it is assumed that the critical value, i.e., the failure threshold , is known. In this situation, a non-normalized distance between the centroid (state from the model training stage) and the current state should be introduced. In the experimental implementation presented in this study, the Manhattan distance was used as the primary metric for CBM-based anomaly quantification. Equation (21) presents the Euclidean distance solely as a representative example of a distance metric that can be employed within the proposed framework.

If the minimum risk value corresponds to the distance , and the critical value is known, the CBM component can be expressed as a linear function with saturation:

where . The hybrid model makes it possible to determine a failure risk measure that takes into account both the RCM component (based on the history of machine element failures) and the CBM component (resulting from the observation of current and historical anomalies). The overall value of (Hybrid Risk Index) can be expressed as a weighted average:

In this expression, denotes the probability of failure estimated from survival curves obtained using the Weibull distribution, representing the RCM component. The term corresponds to the risk measure derived from the CBM component, which is determined on the basis of current and historical anomalies in process or environmental variables. The symbols and denote the weights assigned to the RCM and CBM components, respectively, and reflect the confidence level in the estimations of each component. These weights can be selected depending on the specifics of the process, either arbitrarily or based on the uncertainty level of the estimations of both components.

In the experiments presented in this study, the weighting coefficients and were selected a priori, and not obtained through numerical optimization. Equal weights were adopted () to ensure a balanced contribution of reliability-based failure probabilities and condition-based risk indicators, given the comparable confidence levels in both components.

The formulation in Equation (23) is intentionally generic and allows for alternative weighting strategies, including uncertainty-driven or data-driven optimization, which may be explored in future work. In practical deployments, the weighting coefficients may depend on expert judgment from maintenance engineers, reflecting their operational experience and confidence in specific diagnostic signals, as well as on the goodness-of-fit and predictive performance of the underlying RCM and CBM models. The use of a weighted average provides flexibility, enabling the method to be tailored to the specific characteristics of a given plant, asset class, or data quality regime, and facilitating adaptation to evolving operational conditions.

1.7. Plan of the Paper

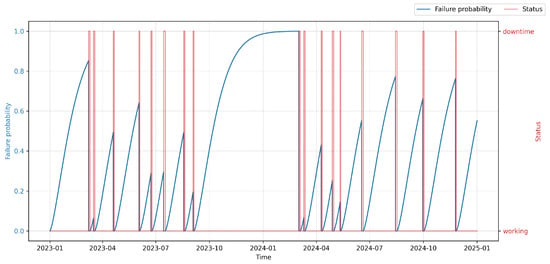

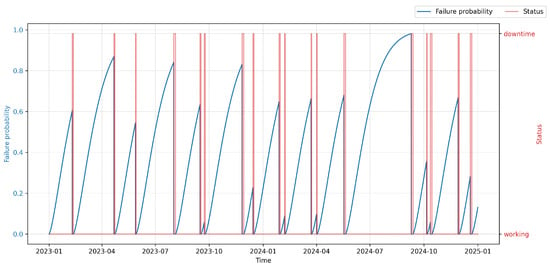

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 describes the materials and methods used in the study, including the preparation of two complementary datasets. The first dataset, NASA N-CMAPSS, is used to model and evaluate predictive maintenance algorithms for turbofan engines, while the second dataset originates from the Smart RDM industrial environment and is used to demonstrate the implementation of the predictive maintenance framework in a real manufacturing context. The section also outlines the applied preprocessing, feature engineering, and simulation methodology.

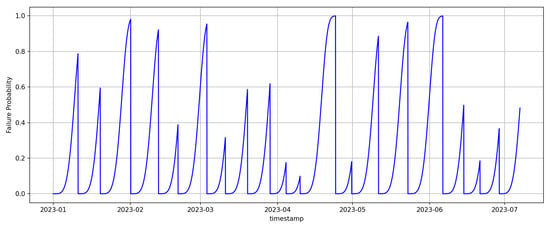

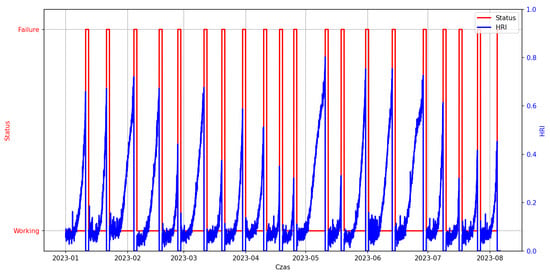

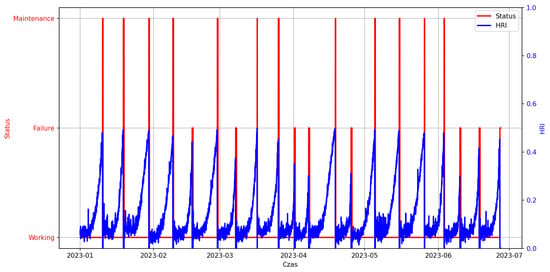

Section 3 presents the results and discussion. It includes the computation of key predictive indicators—Anomaly Level (), Time to Failure (), Failure Probability (), and Hybrid Risk Index ()—and evaluates their effectiveness for both datasets. The section also illustrates how the proposed model was deployed and visualized within the Smart RDM platform to support decision-making in maintenance management.

Finally, Section 4 provides the conclusions and perspectives for future work. It summarizes the main findings, discusses the benefits of integrating RCM and CBM methodologies into a unified Smart Hybrid Maintenance System (SHMS), and highlights the role of the and Optimal Maintenance Point () in improving maintenance planning and operational efficiency.

The integration of energy efficiency concepts into predictive maintenance modeling requires a methodological framework that connects technical reliability with measurable energy performance indicators. In this study, the SHMS is developed as a comprehensive solution addressing both aspects—reliability and energy optimization. To evaluate these interactions, the proposed methodology incorporates classical reliability metrics such as MTBF and MTTR, alongside energy-related indicators: the Energy Efficiency Index (EEI), the Expected Energy Not Supplied (EENS), and the Overall Equipment Effectiveness (OEE). By linking predictive diagnostics with energy-oriented KPIs, the SHMS enables quantification of the energy savings resulting from reduced downtime, optimized load distribution, and improved machine operating conditions. The methodological framework described in the following section outlines the data structures, analytical procedures, and simulation environment used to model the hybrid maintenance process, integrating RCM, CBM, and energy-efficiency assessment into a single, data-driven architecture.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Quantitative Relationships Between Maintenance Indicators and Energy Efficiency

Recent macro-level analyses highlight the strong economic and energy implications of unplanned equipment downtime in industrial environments. The International Energy Agency (IEA) estimates that energy-intensive industries lose nearly USD 50 billion annually due to unplanned outages, with individual facilities experiencing 3–5% production capacity losses as a direct result of equipment failures [69]. Data-driven predictive maintenance programes—combining high-frequency sensing with machine learning analytics—can reduce downtime by 10–20%, yielding global savings of USD 8–15 billion per year while simultaneously reducing energy waste and CO2 emissions. These figures reinforce the rationale for integrating reliability and energy-efficiency indicators within predictive maintenance modeling. This integration forms the methodological foundation of the SHMS framework presented in this section. The macroeconomic perspective aligns with earlier findings showing that inadequate preventive maintenance practices can increase the specific energy consumption of industrial plants by up to 10–15% due to extended downtime and reduced equipment availability [70]. These results confirm that structured maintenance programs significantly lower total energy losses through improved reliability and process stability, highlighting the critical role of preventive strategies in energy optimization.

Machine availability is one of the primary determinants of overall energy efficiency in manufacturing and energy systems. High availability reduces the frequency of equipment start-up and shutdown cycles, which are known to increase energy losses due to transient operational inefficiencies. Empirical studies have demonstrated that each 1% improvement in technical availability can yield between 0.5 and 0.8% reduction in specific energy consumption at the system level [1,2]. Industrial case studies have shown that optimizing maintenance scheduling to maintain availability above 98% can result in energy savings exceeding 5% annually, primarily due to reduced standby and idling losses [10].

To further quantify this relationship, the availability-based payback model was applied to express the economic and energetic benefits of maintenance improvements as a function of availability gain, energy savings, and investment cost [71]. This formulation directly links maintenance-driven efficiency improvements with financial return periods, offering a practical basis for evaluating maintenance decisions from both reliability and energy perspectives.

Applications of Reliability-Centered Maintenance (RCM) in energy-intensive systems have been shown to be associated with higher availability and improved thermal efficiency, with typical gains in the range of 5–6% [7]. These quantitative correlations highlight that maintenance-driven improvements in availability directly enhance energy performance, validating the inclusion of availability as a core metric in the SHMS energy efficiency evaluation framework.

Reliability indicators such as Mean Time Between Failures (MTBF) and Mean Time to Repair (MTTR) are also closely related to energy performance. Low MTBF values indicate frequent interruptions that force equipment to operate outside optimal efficiency zones, while long MTTR increases the duration of energy-inefficient downtime periods. Statistical analyses of industrial data reveal that an increase in MTBF by 10 h can reduce specific energy consumption by 1.2–1.8%, depending on the process type [7,9]. Experimental studies have confirmed that incorporating energy-based triggers into CBM increases MTBF and reduces total energy losses [1]. Furthermore, optimizing maintenance intervals through combined reliability and energy co-optimization has been shown to reduce expected energy not supplied (EENS) by nearly 4% while improving overall turbine availability by approximately 3% [6]. These findings underline the necessity of including MTBF and MTTR within energy-aware maintenance models, as their optimization yields measurable improvements in both reliability and energy efficiency. In addition, following the probabilistic approach described in [72], the proposed SHMS incorporates a reliability–cost–energy coupling term to capture degradation-related energy losses. This extension allows the framework to estimate expected energy waste during degraded operation as a function of downtime duration and component reliability, thereby linking stochastic reliability behavior with real energy impacts.

Energy-oriented Key Performance Indicators (KPIs), such as the Energy Efficiency Index (EEI), Overall Equipment Effectiveness (OEE), and Expected Energy Not Supplied (EENS), provide a quantitative link between predictive maintenance outcomes and energy efficiency. The EEI captures variations in equipment energy performance as a function of degradation, while OEE combines the effects of availability, performance, and quality losses, serving as a holistic proxy for energy efficiency. Statistical modeling results indicate that predictive maintenance systems maintaining OEE above 85% can reduce total process energy intensity by 8–12%, primarily by minimizing micro-stoppages and non-productive operation [8,9,11]. Recent analyses also show that predictive scheduling based on LSTM architectures can improve OEE by approximately 9% and reduce compressed air energy consumption by nearly 9% [4]. In addition, real-time predictive maintenance of air compressors has achieved an improvement of over 10% in EEI, confirming the importance of explainable AI in enhancing both reliability and energy performance [11]. These findings confirm that integrating EEI, OEE, and EENS within predictive maintenance modeling enables the quantitative assessment of energy-related maintenance benefits. Finally, the integration of AI-based analytics proposed in [69] reinforces the methodological foundation of SHMS by enabling automatic identification of energy–reliability correlations through hybrid modeling and data-driven signal interpretation. This integration ensures that the developed framework captures both quantitative dependencies and contextual insights linking predictive maintenance outcomes with measurable energy efficiency improvements. These relationships between reliability and energy indicators constitute the foundation for the energy-efficiency assessment module of the SHMS. In subsequent sections, the data-driven methodology explicitly quantifies how reliability improvements—reflected by higher MTBF and availability, and lower MTTR—translate into measurable energy savings and reduced carbon intensity. In summary, Section 2.1 establishes the quantitative foundation linking maintenance performance to energy efficiency, providing the empirical and theoretical basis for the simulation and validation procedures presented in the following sections.

The relationships discussed in this section are adopted from the literature and serve as a conceptual and quantitative foundation for the proposed framework. Their independent experimental verification is beyond the scope of the present study, which focuses on the integration and operational validation of reliability- and condition-based indicators.

2.2. Data Description

2.2.1. Modeling the Predictive Maintenance Process Using the NASA N-CMAPSS Dataset

This study utilizes the N-CMAPSS dataset developed by NASA for the purpose of prognostic and predictive maintenance of turbofan jet engines. The dataset consists of multivariate time series representing the operational trajectories of engines under various conditions and fault modes. Each time series corresponds to a unique engine instance and begins in a healthy operational state, gradually progressing toward system failure in the training set, while in the test set, trajectories end before the point of failure. This structure allows for the development and evaluation of models focused on Remaining Useful Life (RUL) estimation, binary/multiclass failure classification, and anomaly detection.

Although primarily used for Remaining Useful Life (RUL) prediction, the N-CMAPSS dataset also provides a suitable basis for assessing the relationship between system reliability and energy efficiency. In the proposed SHMS framework, degradation trajectories are mapped to variations in power demand, allowing energy-intensity trends to be inferred from the failure progression profiles. This coupling enables quantitative estimation of the energetic impact of maintenance interventions within a standardized benchmark environment. This linkage between degradation and power demand allows the SHMS to evaluate how predictive interventions would affect energy efficiency in aviation-like systems, where fuel consumption and mechanical load are critical proxies for energy use.

The dataset used in this work is specifically the N-CMAPSS_DS02-006.h5 file, which includes realistic degradation behavior under real flight conditions [73]. From this source, we generated training and test datasets using a sliding time window approach with a window size of 50, a stride of 1, and a subsampling factor of 10 to reduce memory usage and simulate lower-frequency measurements. For model development, six units (u = 2, 5, 10, 16, 18, 20) were used for training and three units (u = 11, 14, 15) for testing, in line with the configuration proposed in [74].

To address class imbalance—an inherent challenge in predictive maintenance datasets due to the rarity of failure events—we employed the SMOTE (Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique) algorithm [75]. SMOTE generates synthetic examples of minority class instances by interpolating between existing samples and their nearest neighbors. This method helps improve model generalizability and mitigates the bias toward majority classes.

Feature engineering was applied to the time series data using both time-domain and frequency-domain statistical descriptors, including mean, standard deviation, skewness, kurtosis, and spectral entropy. These features enhance the capacity of downstream models to detect degradation trends and patterns indicative of failure.

The final dataset consists of standardized and normalized input tensors suitable for deep learning models. Each sample has the shape , where N is the number of samples aggregated across all engine units, and V is the number of sensor variables. Ground truth RUL labels were associated with each sample in the test set for performance evaluation of prognostic models.

It should be noted that the NASA N-CMAPSS dataset does not provide direct measurements of energy consumption. In this case, energy efficiency indicators are inferred from degradation trajectories, operating regimes, and reliability profiles, and are used as relative proxies of energy intensity rather than as absolute energy measurements. The resulting metrics therefore quantify comparative trends and potential energy impacts of maintenance strategies, rather than direct metered consumption.

All data preparation and sampling procedures followed the publicly available scripts from the NASA Prognostics Data Repository and implementation guidelines as referenced in [74,76,77].

2.2.2. Modeling the Predictive Maintenance Process in the Smart RDM Environment

The modeling and implementation of the predictive maintenance (PdM) process were carried out within the Smart RDM platform—an industrial analytics and monitoring environment designed to support data-driven decision-making in production systems. Smart RDM enables the integration of heterogeneous data sources, including real-time sensor measurements, process control variables, event logs, and maintenance records. The platform provides a unified operational context for data visualization, anomaly detection, and performance analysis, allowing for continuous supervision of machine health and process stability.

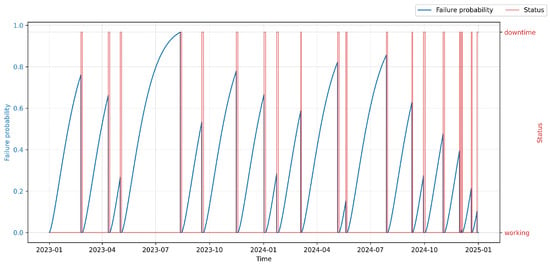

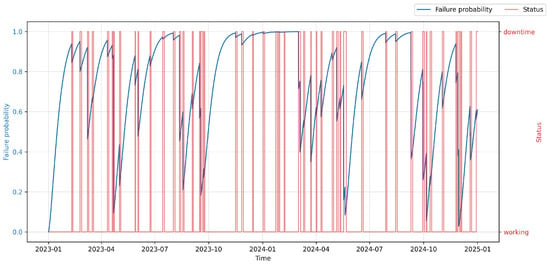

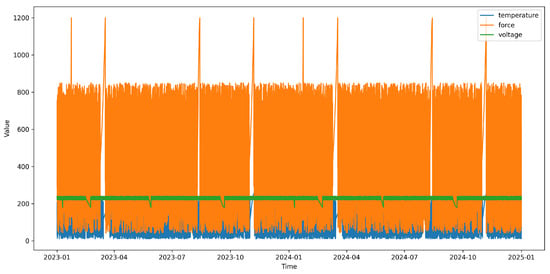

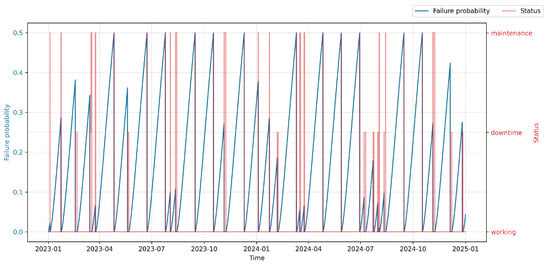

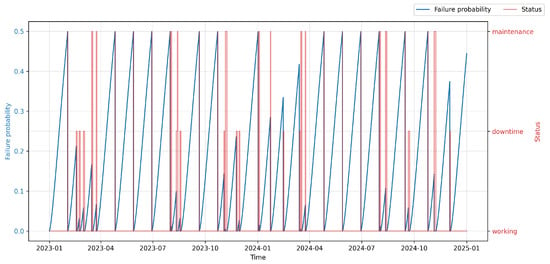

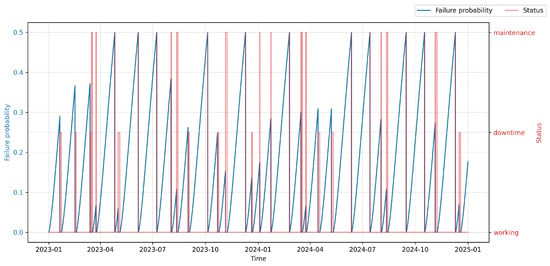

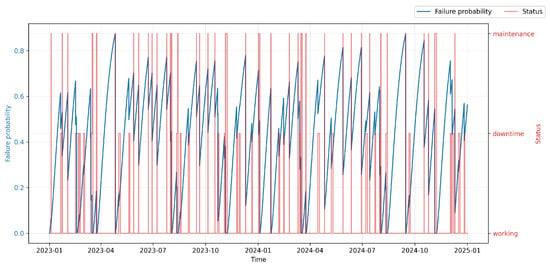

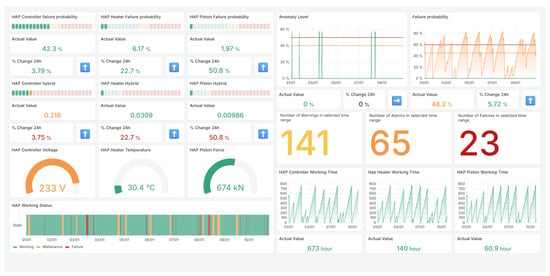

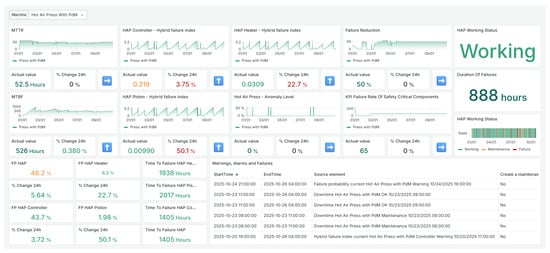

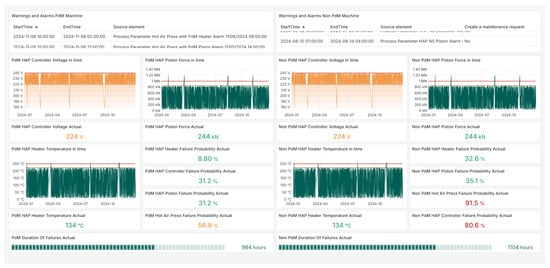

The Smart RDM environment features a modular architecture comprising interactive dashboards, analytical modules, data forms, and event-driven notification mechanisms. These components are supported by an integrated data layer that consolidates historical and live process information. In the present study, Smart RDM was configured to collect, aggregate, and analyze data from two industrial presses used in the manufacture of wooden boards. The interactive dashboards support anomaly visualization, reliability analysis, and operator decision-making (see Figure 4). Within this environment, we instantiated and evaluated the SHMS, which combines RCM and CBM components into the defined in Equation (23).

Figure 4.

Smart RDM: Example of the dashboard environment used for predictive maintenance modeling.

To evaluate the PdM process, two categories of machines were considered: (1) a reference press operating without maintenance actions (baseline scenario), and (2) a press managed under a predictive maintenance regime (PdM scenario). The dataset included time series signals such as heater temperature, controller voltage, and piston force, as well as operational counters, event timestamps, and metadata related to machine states. For the maintained press, additional annotations specified the type, duration, and timing of service activities, providing ground-truth labels for model validation and temporal analysis. The unmaintained press served as a control case, allowing for the assessment of the impact of PdM on performance indicators and downtime reduction.

The scientific objective of the conducted PdM deployment was to develop and evaluate methods of predictive maintenance aimed at improving equipment operational efficiency and reducing unplanned downtimes through automated maintenance scheduling. Within the experimental environment, a so-called virtual operator was implemented in the Smart RDM system. Within the experimental environment, a so-called virtual operator was implemented in the Smart RDM system. It acts as a rule-based autonomous decision layer that translates the continuous into maintenance actions. The decision logic is anchored to the concept of the , which is defined as a configurable threshold reflecting the balance between failure risk, maintenance cost, and operational criticality.

At each evaluation step, the virtual operator monitors both the current value and the temporal trend of . When exceeds a predefined warning threshold (), the system generates advisory alerts for maintenance personnel, indicating elevated risk and recommending inspection or planning of maintenance activities. If further exceeds the critical threshold corresponding to the Optimal Maintenance Point (), autonomous actions are triggered, such as scheduling a planned stop, generating a maintenance work order, or temporarily limiting machine operation.

The thresholds are not fixed constants but configurable parameters defined based on historical reliability data, component criticality, and operational constraints. This design allows the virtual operator to avoid both premature interventions and delayed responses, ensuring economically and operationally optimal maintenance timing.

The main research objectives related to the implementation of the Smart RDM-based predictive maintenance concept included the following:

- Analysis of the potential for reducing unplanned downtimes and increasing machine availability under production conditions;

- Evaluation of the cost-effectiveness of data-driven maintenance strategies compared to traditional preventive approaches;

- Verification of the impact of early fault detection and prognostic maintenance planning on production process continuity;