Sustainable Design and Energy Efficiency in Supertall and Megatall Buildings: Challenges of Multi-Criteria Certification Implementation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

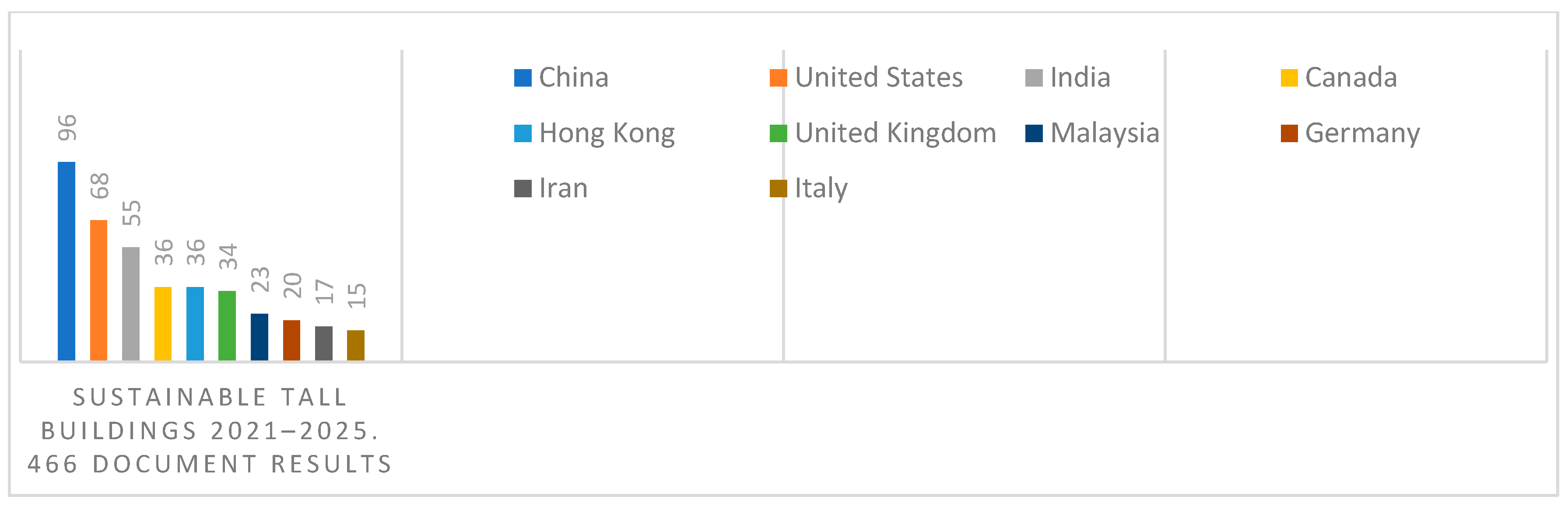

3.1. Literature Analysis

3.2. Sustainability and Multi-Criteria Certification

3.3. The World’s Tallest Buildings

3.4. Pro-Ecological Solutions and Renewable Energy in High-Rise Buildings: Case Studies

3.4.1. Burj Khalifa, Dubai, United Arab Emirates

3.4.2. Merdeka 118, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

3.4.3. Shanghai Tower, Shanghai, China

3.4.4. Makkah Royal Clock Tower, Mecca, Saudi Arabia

3.4.5. Ping an Finance Centre, Shenzhen, China

3.4.6. Lotte World Tower, Seoul, South Korea

3.4.7. One World Trade Center, New York City, United States

3.4.8. Guangzhou CTF Finance Centre, Guangzhou, China

3.4.9. Tianjin CTF Finance Centre, Tianjin, China

3.4.10. CITIC Tower, Beijing, China

3.4.11. Taipei 101, Taipei, China

3.4.12. Shanghai World Financial Center, Shanghai, China

3.4.13. International Commerce Centre, Hong Kong, China

3.4.14. Wuhan Greenland Center, Wuhan, China

3.4.15. Central Park Tower, New York City, United States

3.4.16. Lakhta Center, St. Petersburg, Russia

3.4.17. Vincom Landmark 81, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam

3.4.18. Changsha IFS Tower T1, Changsha, China

3.4.19. Petronas Twin Tower 1 and Petronas Twin Tower 2, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

4. Discussion

4.1. Multi-Criteria Certification

4.2. Sustainable Solutions in High-Rise Buildings

4.3. Building Structure and Economics: Design Issues

4.4. Quantitative Analysis

4.5. Qualitative Analysis

4.6. Correlation Analysis

4.7. Trend Analysis over Time

4.8. Limitations

5. Conclusions

5.1. Theoretical and Design Conclusions

5.2. Research Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CTBUH | The Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat |

| CSR | corporate social responsibility |

| EF | environmental footprint, |

| GBRSs | Green Building Rating Systems |

| LEED | Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design |

| BREEAM | Building Research Establishment Environmental Assessment Method |

| DGNB | Deutsche Gesellschaft für Nachhaltiges Bauen |

| GBI | Green Building Index |

Appendix A. Sustainable Development Strategy Assessment Cards Developed by the Authors

Appendix A.1. Sustainable Development Strategy Assessment Card: Burj Khalifa

- Location: Dubai, United Arab Emirates

- Assessment Date: 2 December 2025

- Assessor: Authors

- Certifications: LEED Platinum certification under the v4.1 Operations and Maintenance: Existing Buildings (2024)

| Strategy | Notes/Description | Code (0–3) |

|---|---|---|

| Orientation optimization | Y-shaped floor plan, floor rotation minimizes wind vortex merging and maximizes views | 1 |

| Daylighting optimization | The glass used in the building boasts very high solar and thermal efficiency | 1 |

| Passive solar heating/shading | High-performance glass facade and aluminum and steel panels reduce overheating and reflections; the system primarily functions as passive cooling | 2 |

| Natural ventilation | No information about the use; high-rise building likely based on full air conditioning | 0 |

| Thermal mass | A structure based on massive concrete, helping to buffer temperatures | 1 |

| Strategy | Notes/Description | Code (0–3) |

|---|---|---|

| High—efficiency HVAC | HVAC with additional energy savings, air units with thermal wheels, variable speed systems, control systems. | 2 |

| Demand—controlled ventilation | No data | 0 |

| High—efficiency lighting (LED + controls) | No detailed data, LEED O+M, 1 was assumed | 1 |

| Heat recovery systems | No data | 0 |

| Building automation/BMS | BMS and electronic measurement system | 3 |

| Strategy | Notes/Description | Code (0–3) |

|---|---|---|

| Photovoltaic panels | No data | 0 |

| Solar thermal collectors | No data | 0 |

| Geothermal systems | No data | 0 |

| Energy storage | No data | 0 |

| Hybrid renewable solutions | No data | 0 |

| Strategy | Notes/Description | Code (0–3) |

|---|---|---|

| Low—carbon/recycled materials | High-strength concrete and steel—no data on low emissions | 0 |

| Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) | No data | 0 |

| Water—saving fixtures | No data | 0 |

| Greywater/rainwater systems | No data | 0 |

| Design for disassembly/circularity | No data | 0 |

| Category | Score (Sum) | Average | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | 5 | 1.0 | |

| B | 6 | 1.2 | |

| C | 0 | 0.0 | |

| D | 0 | 0.0 |

Appendix A.2. Sustainable Development Strategy Assessment Card: Merdeka 118

- Location: Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

- Assessment Date: 2 December 2025

- Assessor: Authors

- Certifications: LEED Platinum, 86/110, (LEED BD+C: Core and Shell)

| Strategy | Notes/Description | Code (0–3) |

|---|---|---|

| Orientation optimization | The building is designed primarily with wind loads in mind, the building has a diamond-shaped facade and multi-faceted glass surface—this may help disperse light/heat | 2 |

| Daylighting optimization | Façade with “low-E/glazed glass” | 2 |

| Passive solar heating/shading | Low-emission (low-E) and high-performance glass façade, which reduces heat gain and cooling load—passive heat gain reduction. | 1 |

| Natural ventilation | No data—high-rise building, probably full mechanical ventilation | 0 |

| Thermal mass | The reinforced concrete core design provides high thermal inertia, but not as a primary strategy | 1 |

| Strategy | Notes/Description | Code (0–3) |

|---|---|---|

| High—efficiency HVAC | High scores in the LEED “Energy and Atmosphere” category; designed for energy efficiency | 2 |

| Demand—controlled ventilation | Systems with daylight sensors, which suggests automation and optimization of internal systems | 1 |

| High—efficiency lighting (LED + controls) | LED lighting | 2 |

| Heat recovery systems | No data | 0 |

| Building automation/BMS | Intelligent building management system BMS and smart metering | 3 |

| Strategy | Notes/Description | Code (0–3) |

|---|---|---|

| Photovoltaic panels | Building—integrated photovoltaic on the roof/podium of the building—although the share in the building’s power supply is a small percentage (~1.2% of the electricity demand) | 1 |

| Solar thermal collectors | Hot water for the building is supplied by a solar-thermal system located on the roof. | 3 |

| Geothermal systems | No data | 0 |

| Energy storage | No data | 0 |

| Hybrid renewable solutions | No data | 0 |

| Strategy | Notes/Description | Code (0–3) |

|---|---|---|

| Low—carbon/recycled materials | Low-emission materials were used | 2 |

| Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) | No data | 0 |

| Water—saving fixtures | Low-flow devices | 3 |

| Greywater/rainwater systems | Rainwater harvesting | 3 |

| Design for disassembly/circularity | Infrastructure for waste separation, reuse and recycling | 2 |

| Category | Score (Sum) | Average | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | 6 | 1.2 | |

| B | 8 | 1.6 | |

| C | 4 | 0.8 | |

| D | 10 | 2.0 |

Appendix A.3. Sustainable Development Strategy Assessment Card, Shanghai Tower

- Location: Shanghai, China

- Assessment Date: 2 December 2025

- Assessor: Authors

- Certifications: LEED Platinum BD+C: Core and Shell, 82/100, China Green Building

| Strategy | Notes/Description | Code (0–3) |

|---|---|---|

| Orientation optimization | No data on optimization with respect to world pages | 1 |

| Daylighting optimization | Large glazing area; no information about deliberate optimization | 1 |

| Passive solar heating/shading | No data on passive shading systems | 1 |

| Natural ventilation | The double façade allows for indirect ventilation and reduces air conditioning loads. | 2 |

| Thermal mass | Reinforced concrete core, but not as the main energy strategy | 1 |

| Strategy | Notes/Description | Code (0–3) |

|---|---|---|

| High—efficiency HVAC | High-efficiency HVAC systems, energy simulations, LEED-compliant optimization | 2 |

| Demand—controlled ventilation | The building is LEED Gold certified; probably used | 1 |

| High—efficiency lighting (LED + controls) | Effective LED system | 2 |

| Heat recovery systems | No data | 0 |

| Building automation/BMS | Advanced water and energy consumption monitoring systems—BMS | 3 |

| Strategy | Notes/Description | Code (0–3) |

|---|---|---|

| Photovoltaic panels | No data | 0 |

| Solar thermal collectors | No data | 0 |

| Geothermal systems | Ground-source heat pump system (GSHP) | 3 |

| Energy storage | No data | 0 |

| Hybrid renewable solutions | Rooftop wind turbines + GSHP, hybrid renewable energy system | 3 |

| Strategy | Notes/Description | Code (0–3) |

|---|---|---|

| Low—carbon/recycled materials | No data | 0 |

| Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) | No data | 0 |

| Water—saving fixtures | Water-saving devices, consumption monitoring | 3 |

| Greywater/rainwater systems | Rainwater collection system for irrigation and toilets | 2 |

| Design for disassembly/circularity | No data | 0 |

| Category | Score (Sum) | Average | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | 6 | 1.2 | |

| B | 8 | 1.6 | |

| C | 6 | 1.2 | |

| D | 5 | 1.0 |

- The building is LEED Gold certified.

- The double-skin façade is a key energy strategy.

- The building is a benchmark for sustainable construction in China.

Appendix A.4. Sustainable Development Strategy Assessment Card: Makkah Royal Clock Tower

- Location: Mecca, Saudi Arabia

- Assessment Date: 2 December 2025

- Assessor: Authors

- Certifications: No certification in official databases

| Strategy | Notes/Description | Code (0–3) |

|---|---|---|

| Orientation optimization | No data | 0 |

| Daylighting optimization | No data | 0 |

| Passive solar heating/shading | No data | 0 |

| Natural ventilation | No possibility of natural ventilation in such a tall and fully air-conditioned facility | 0 |

| Thermal mass | Reinforced concrete construction can provide thermal mass, but not as a conscious strategy | 1 |

| Strategy | Notes/Description | Code (0–3) |

|---|---|---|

| High—efficiency HVAC | No data | 0 |

| Demand—controlled ventilation | No data | 0 |

| High—efficiency lighting (LED + controls) | No data | 0 |

| Heat recovery systems | No data | 0 |

| Building automation/BMS | No data | 0 |

| Strategy | Notes/Description | Code (0–3) |

|---|---|---|

| Photovoltaic panels | No data | 0 |

| Solar thermal collectors | No data | 0 |

| Geothermal systems | No data | 0 |

| Energy storage | No data | 0 |

| Hybrid renewable solutions | No data | 0 |

| Strategy | Notes/Description | Code (0–3) |

|---|---|---|

| Low—carbon/recycled materials | No data | 0 |

| Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) | No data | 0 |

| Water—saving fixtures | No data | 0 |

| Greywater/rainwater systems | No data | 0 |

| Design for disassembly/circularity | No data | 0 |

| Category | Score (Sum) | Average | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | 1 | 0.2 | |

| B | 0 | 0 | |

| C | 0 | 0 | |

| D | 0 | 0 |

- The skyscraper was built in 2012, at a time when large-scale projects in the Middle East rarely incorporated sustainable strategies (structural and air-conditioning solutions predominated).

- The building’s height and hotel/pilgrimage function dictate its complete reliance on active cooling systems.

Appendix A.5. Sustainable Development Strategy Assessment Card Ping an Finance Centre

- Location: Shenzhen

- Assessment Date: 2 December 2025

- Assessor: Authors

- Certifications: LEED Platinum (Operations & Maintenance: Existing Buildings), LEED Gold (Core & Shell), BREAAM, Three Star

| Strategy | Notes/Description | Code (0–3) |

|---|---|---|

| Orientation optimization | No orientation analysis data; geometry optimized primarily for wind | 1 |

| Daylighting optimization | Very high daylight transmittance thanks to the high-performance façade | 2 |

| Passive solar heating/shading | Low-e facade reduces heat gains | 1 |

| Natural ventilation | The higher parts of the tower have access to fresh air thanks to the climatic conditions | 1 |

| Thermal mass | No use of thermal mass as a strategy | 0 |

| Strategy | Notes/Description | Code (0–3) |

|---|---|---|

| High—efficiency HVAC | Access to fresh air in higher zones, optimized for subtropical climates | 2 |

| Demand—controlled ventilation | Air recirculation control | 1 |

| High—efficiency lighting (LED + controls) | No data | 0 |

| Heat recovery systems | Regenerative drive elevators recover energy | 2 |

| Building automation/BMS | Advanced real-time energy monitoring system | 3 |

| Strategy | Notes/Description | Code (0–3) |

|---|---|---|

| Photovoltaic panels | No data | 0 |

| Solar thermal collectors | No data | 0 |

| Geothermal systems | No data | 0 |

| Energy storage | No data | 0 |

| Hybrid renewable solutions | No data | 0 |

| Strategy | Notes/Description | Code (0–3) |

|---|---|---|

| Low—carbon/recycled materials | No data | 0 |

| Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) | No data | 0 |

| Water—saving fixtures | No data | 0 |

| Greywater/rainwater systems | No data | 0 |

| Design for disassembly/circularity | No data | 0 |

| Category | Score (Sum) | Average | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | 5 | 1.0 | |

| B | 8 | 1.6 | |

| C | 0 | 0.0 | |

| D | 0 | 0.0 |

Appendix A.6. Sustainable Development Strategy Assessment Card: Lotte World Tower

- Location: Seoul, Republic of Korea

- Assessment Date: 2 December 2025

- Assessor: Authors

- Certifications: LEED BD + C: New Construction, Gold, 66/110

| Strategy | Notes/Description | Code (0–3) |

|---|---|---|

| Orientation optimization | No information about conscious optimization of orientation | 0 |

| Daylighting optimization | High-performance façade and LEED certification suggest good use of daylight | 1 |

| Passive solar heating/shading | No data | 0 |

| Natural ventilation | No data | 0 |

| Thermal mass | The concrete core and slabs were not described as a thermal mass element | 0 |

| Strategy | Notes/Description | Code (0–3) |

|---|---|---|

| High—efficiency HVAC | Variable frequency drives (VFD) | 2 |

| Demand—controlled ventilation | No data | 0 |

| High—efficiency lighting (LED + controls) | LEED Gold suggests a high probability of LED | 1 |

| Heat recovery systems | Energy recovered from exhaust air | 2 |

| Building automation/BMS | SHM and energy-saving systems, advanced BMS | 2 |

| Strategy | Notes/Description | Code (0–3) |

|---|---|---|

| Photovoltaic panels | PV as one of the main renewable energy sources | 2 |

| Solar thermal collectors | No data | 0 |

| Geothermal systems | geothermal energy | 3 |

| Energy storage | No data | 0 |

| Hybrid renewable solutions | Renewable energy: geothermal energy, PV, wind turbines | 3 |

| Strategy | Notes/Description | Code (0–3) |

|---|---|---|

| Low—carbon/recycled materials | No data | 0 |

| Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) | No data | 0 |

| Water—saving fixtures | Low-flow devices (30% water savings) | 2 |

| Greywater/rainwater systems | Grey water reuse system | 2 |

| Design for disassembly/circularity | No data | 0 |

| Category | Score (Sum) | Average | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | 1 | 0.2 | |

| B | 7 | 1.4 | |

| C | 8 | 1.6 | |

| D | 4 | 0.7 |

- Combination of geothermal energy, PV panels and wind turbines

- SHM (Structural Health Monitoring) increases the safety and efficiency of facility maintenance, which indirectly supports sustainable development.

- Significant water savings (30%) thanks to grey water + low-flow devices.

Appendix A.7. Sustainable Development Strategy Assessment Card: One World Trade Center

- Location: New York City, USA

- Assessment Date: 2 December 2025

- Assessor: Authors

- Certifications: LEED Gold BD + C, 37/62

| Strategy | Notes/Description | Code (0–3) |

|---|---|---|

| Orientation optimization | No detailed information on orientation optimization, but the unique octahedron form suggests natural solar gain control. | 1 |

| Daylighting optimization | Automatic “daylight” system controlling the lighting | 2 |

| Passive solar heating/shading | No specific shading systems mentioned, but the building’s design and orientation likely minimize solar heat gain. | 1 |

| Natural ventilation | No significant mention of natural ventilation, likely mitigated by advanced HVAC systems | 0 |

| Thermal mass | Concrete core provides some thermal mass benefits, but no further details on its design role in passive cooling. | 1 |

| Strategy | Notes/Description | Code (0–3) |

|---|---|---|

| High—efficiency HVAC | High-efficiency HVAC systems are integrated into the building, contributing to its energy efficiency goals. | 2 |

| Demand—controlled ventilation | The building has a “daylight” system that controls lighting, suggesting the possibility of demand-controlled ventilation as well. | 1 |

| High—efficiency lighting (LED + controls) | Daylight system and energy-saving lighting technology are used to minimize energy consumption. | 2 |

| Heat recovery systems | Energy-saving technology is implemented. | 1 |

| Building automation/BMS | Advanced building automation systems are in place for energy efficiency and comfort. | 2 |

| Strategy | Notes/Description | Code (0–3) |

|---|---|---|

| Photovoltaic panels | No data | 0 |

| Solar thermal collectors | No data | 0 |

| Geothermal systems | No data | 0 |

| Energy storage | 12 hydrogen-powered batteries supply energy to the building, contributing to its renewable energy system. | 2 |

| Hybrid renewable solutions | Hydrogen-powered fuel cells and possibly other renewables like wind or solar may be integrated into a hybrid system. | 2 |

| Strategy | Notes/Description | Code (0–3) |

|---|---|---|

| Low—carbon/recycled materials | Green concrete (replacing 50% of cement with industrial byproducts), recycled steel, drywall, and ceiling tiles are used. | 3 |

| Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) | No detailed data on LCA, but green concrete and recycled materials suggest that life-cycle considerations were made. | 1 |

| Water—saving fixtures | Rainwater storage tanks used for cooling and irrigation. | 3 |

| Greywater/rainwater systems | Rainwater is stored and used for cooling and irrigation purposes. | 2 |

| Design for disassembly/circularity | No data available on circularity, but emphasis on material reuse and energy-saving suggests circularity considerations. | 0 |

| Category | Score (Sum) | Average | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | 5 | 1.0 | |

| B | 8 | 1.6 | |

| C | 4 | 0.8 | |

| D | 9 | 1.8 |

- Green concrete (replacing 50% of cement with industrial byproducts) reduces the carbon footprint of the building.

- 12 hydrogen-powered batteries contribute to the building’s renewable energy systems.

- 80% of waste is recycled, supporting sustainability in construction and operation.

Appendix A.8. Sustainable Development Strategy Assessment Card: Guangzhou CTF Finance Centre

- Location: Guangzhou, China

- Assessment Date: 2 December 2025

- Assessor: Authors

- Certifications: Hotel: LEED BD+C: New Construction, Gold 61/100, Office/Retail: LEED BD+C: Core and Shell

| Strategy | Notes/Description | Code (0–3) |

|---|---|---|

| Orientation optimization | No detailed data on orientation optimization, though the building’s design likely takes local sun exposure | 1 |

| Daylighting optimization | The use of self-cleaning, corrosion-resistant terracotta on the façade likely supports effective daylight control. | 1 |

| Passive solar heating/shading | No detailed data, but the building’s advanced façade materials and shading might reduce solar heat gain. | 1 |

| Natural ventilation | No information available. Probably due to the height: HVAC systems for comfort | 0 |

| Thermal mass | No data | 0 |

| Strategy | Notes/Description | Code (0–3) |

|---|---|---|

| High—efficiency HVAC | High-efficiency chillers and cooling systems are probably implemented | 2 |

| Demand—controlled ventilation | No data available, but given the advanced HVAC systems, demand-controlled ventilation could be a part of the design. | 1 |

| High—efficiency lighting (LED + controls) | LEED Gold certification suggests the use of high-efficiency LED lighting with controls. | 2 |

| Heat recovery systems | Heat recovery from water-cooled chiller condensers | 2 |

| Building automation/BMS | Advanced BMS was probably integrated for managing energy consumption and environmental control. | 2 |

| Strategy | Notes/Description | Code (0–3) |

|---|---|---|

| Photovoltaic panels | No data | 0 |

| Solar thermal collectors | No data | 0 |

| Geothermal systems | No data | 0 |

| Energy storage | No data | 0 |

| Hybrid renewable solutions | No data | 0 |

| Strategy | Notes/Description | Code (0–3) |

|---|---|---|

| Low—carbon/recycled materials | Self-cleaning, corrosion-resistant terracotta is used on the façade, reducing maintenance and transportation impact. | 2 |

| Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) | No detailed data available, but the LEED Gold certification suggests a likely LCA for material selection. | 1 |

| Water—saving fixtures | Water efficiency is a key feature, with a full score in the LEED water efficiency category. | 3 |

| Greywater/rainwater systems | No specific data, but the highwater efficiency score suggests the presence of such systems | 2 |

| Design for disassembly/circularity | No data available, but circularity may be considered due to LEED Gold standards. | 0 |

| Category | Score (Sum) | Average | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | 3 | 0.6 | |

| B | 9 | 1.8 | |

| C | 0 | 0.0 | |

| D | 8 | 1.6 |

- High-efficiency chillers and heat recovery systems contribute to the building’s sustainable design.

- Water-saving features contribute to a full score in the LEED Water Efficiency category (10/10).

- Facade with self-cleaning and corrosion-resistant terracotta reduces the environmental impact of maintenance and transportation.

Appendix A.9. Sustainable Development Strategy Assessment Card: Tianjin CFT Finance Centre

- Location: Tianjin, China

- Assessment Date: 2 December 2025

- Assessor: Authors

- Certifications: LEED Gold

| Strategy | Notes/Description | Code (0–3) |

|---|---|---|

| Orientation optimization | No specific information on orientation, but the aerodynamic shape likely reduces solar heat gain and optimizes natural daylight. | 1 |

| Daylighting optimization | The high-performance envelope provides excellent daylighting and views, optimizing natural light use | 2 |

| Passive solar heating/shading | The design of the exterior wall and parametric modeling likely helps in controlling solar heat gain. | 2 |

| Natural ventilation | No significant data on natural ventilation; reliance likely on HVAC systems given the building’s height. | 0 |

| Thermal mass | The aerodynamic shape and high-performance envelope likely help in regulating temperatures. | 1 |

| Strategy | Notes/Description | Code (0–3) |

|---|---|---|

| High—efficiency HVAC | Energy and water reduction systems likely include high-efficiency HVAC components for energy savings. | 2 |

| Demand—controlled ventilation | High-performance envelope may work in conjunction with this system. | 1 |

| High—efficiency lighting (LED + controls) | LEED Gold certification suggests high-efficiency LED lighting with controls. | 2 |

| Heat recovery systems | Building likely incorporates energy-saving technology. | 1 |

| Building automation/BMS | Given the LEED Gold rating and focus on energy efficiency, it’s likely that a building management system (BMS) is in place. | 2 |

| Strategy | Notes/Description | Code (0–3) |

|---|---|---|

| Photovoltaic panels | No data | 0 |

| Solar thermal collectors | No data | 0 |

| Geothermal systems | No data | 0 |

| Energy storage | Building’s focus on energy-efficient design suggests the possibility of energy storage systems. | 0 |

| Hybrid renewable solutions | No data | 0 |

| Strategy | Notes/Description | Code (0–3) |

|---|---|---|

| Low—carbon/recycled materials | The building was constructed with a focus on sustainability, but no specific data on low-carbon or recycled materials. | 1 |

| Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) | No specific data on LCA, but the building was designed with sustainability in mind, achieving LEED Gold certification. | 1 |

| Water—saving fixtures | Water efficiency systems are implemented, earning a perfect score (10/10) in the LEED water efficiency category. | 3 |

| Greywater/rainwater systems | No specific mention of greywater systems, but the building’s water-saving features are likely to include such solutions. | 2 |

| Design for disassembly/circularity | No data | 0 |

| Category | Score (Sum) | Average | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | 6 | 1.2 | |

| B | 8 | 1.6 | |

| C | 0 | 0.0 | |

| D | 7 | 1.4 |

Appendix A.10. Sustainable Development Strategy Assessment Card: CITIC Tower

- Location: Beijing, China

- Assessment Date: 2 December 2025

- Assessor: Authors

- Certifications: LEED-CS Gold Precertification, China Certificate of Green Building Label-Three Star

| Strategy | Notes/Description | Code (0–3) |

|---|---|---|

| Orientation optimization | No specific mention of orientation optimization, but the building’s unique shape likely helps optimize sunlight penetration and wind load management. | 1 |

| Daylighting optimization | The building’s design and shape, including the narrowing and widening of the upper portion, likely optimize daylight penetration. | 1 |

| Passive solar heating/shading | No explicit mention of shading strategies, but the building’s shape could mitigate solar heat gain at different levels. | 1 |

| Natural ventilation | No specific mention of natural ventilation; HVAC systems are likely used to control indoor climate. | 0 |

| Thermal mass | No data on thermal mass, but the shape of the building and material selection may aid in temperature regulation. | 1 |

| Strategy | Notes/Description | Code (0–3) |

|---|---|---|

| High—efficiency HVAC | HVAC systems are likely efficient, though specific mention of VFD is not available. | 1 |

| Demand—controlled ventilation | No specific mention of demand-controlled ventilation, but given the advanced design, it is likely part of the system. | 1 |

| High—efficiency lighting (LED + controls) | LEED-CS Gold Precertification suggests that the building includes efficient lighting systems such as LEDs. | 2 |

| Heat recovery systems | No data on heat recovery systems, but the advanced technologies and LEED certification likely include some form of heat recovery. | 1 |

| Building automation/BMS | BIM technology and advanced design suggest a comprehensive Building Management System (BMS) is in place. | 2 |

| Strategy | Notes/Description | Code (0–3) |

|---|---|---|

| Photovoltaic panels | No data | 0 |

| Solar thermal collectors | No data | 0 |

| Geothermal systems | No data | 0 |

| Energy storage | No data | 0 |

| Hybrid renewable solutions | No data available, but the building’s sustainable certifications suggest the possibility of hybrid energy solutions. | 0 |

| Strategy | Notes/Description | Code (0–3) |

|---|---|---|

| Low—carbon/recycled materials | No data available on the specific use of low-carbon or recycled materials, but the building’s sustainability ratings suggest such materials are likely used. | 1 |

| Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) | No specific data available, but the design and sustainability certifications suggest that LCA was likely considered. | 1 |

| Water—saving fixtures | No data on specific water-saving fixtures, but the LEED Gold Precertification indicates water efficiency features are in place. | 2 |

| Greywater/rainwater systems | No data | 0 |

| Design for disassembly/circularity | No data | 0 |

| Category | Score (Sum) | Average | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | 4 | 0.8 | |

| B | 7 | 1.4 | |

| C | 0 | 0.0 | |

| D | 4 | 0.8 |

Appendix A.11. Sustainable Development Strategy Assessment Card: Taipei 101

- Location: Taiwan

- Assessment Date: 2 December 2025

- Assessor: Authors

- Certifications: LEED Platinum (2011), LEED Platinum O+M: Existing Buildings (2016), LEED Recertification Platinum (2021)

| Strategy | Notes/Description | Code (0–3) |

|---|---|---|

| Orientation optimization | No specific data available, but the building’s design likely maximizes natural light. | 1 |

| Daylighting optimization | The use of low-emissivity glass suggests an attempt to optimize daylight while reducing heat gain. | 2 |

| Passive solar heating/shading | The graywater system and low-emissivity glass suggest passive solar management, but no specific mention of shading. | 1 |

| Natural ventilation | No specific mention of natural ventilation, but HVAC systems are in place. | 0 |

| Thermal mass | The use of advanced glass might help with temperature regulation. | 1 |

| Strategy | Notes/Description | Code (0–3) |

|---|---|---|

| High—efficiency HVAC | Mechanical heating, ventilation, and air conditioning systems were upgraded during renovations. | 2 |

| Demand—controlled ventilation | The introduction of a building management system (BMS) likely includes demand-controlled ventilation. | 2 |

| High—efficiency lighting (LED + controls) | Lighting fixtures were replaced with energy-efficient ones during renovations. | 2 |

| Heat recovery systems | No specific mention of heat recovery, though the BMS may control temperature and ventilation for efficiency. | 1 |

| Building automation/BMS | The BMS provides detailed monitoring and control of energy use, including lights and HVAC. | 3 |

| Strategy | Notes/Description | Code (0–3) |

|---|---|---|

| Photovoltaic panels | No data | 0 |

| Solar thermal collectors | No data | 0 |

| Geothermal systems | No data | 0 |

| Energy storage | No data | 0 |

| Hybrid renewable solutions | The building’s sustainability initiatives suggest potential future integration. | 0 |

| Strategy | Notes/Description | Code (0–3) |

|---|---|---|

| Low—carbon/recycled materials | No data on the use of recycled or low-carbon materials, but sustainable building practices are evident. | 1 |

| Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) | No direct mention of LCA, though renovations aimed at energy savings and environmental impact reduction. | 1 |

| Water—saving fixtures | The building’s management system enables improved water efficiency and significant savings in consumption. | 2 |

| Greywater/rainwater systems | The building includes a graywater treatment system for reuse | 3 |

| Design for disassembly/circularity | No data available on design for disassembly, but sustainable water systems and management suggest circular strategies. | 1 |

| Category | Score (Sum) | Average | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | 5 | 1.0 | |

| B | 10 | 2.0 | |

| C | 0 | 0.0 | |

| D | 8 | 1.6 |

- Renovations: Significant improvements, including a new Building Management System (BMS), resulted in better energy and water efficiency.

- Sustainability Initiatives: The graywater system, low-emissivity glass, and focus on energy-efficient lighting demonstrate the building’s ongoing commitment to reducing its environmental impact.

Appendix A.12. Sustainable Development Strategy Assessment Card, Shanghai World Financial Center

- Location: Shanghai, China

- Assessment Date: 2 December 2025

- Assessor: Authors

- Certifications: No certification in official databases

| Strategy | Notes/Description | Code (0–3) |

|---|---|---|

| Orientation optimization | No specific mention of orientation optimization, but building form likely reduces energy demand by limiting direct solar gain. | 1 |

| Daylighting optimization | No direct mention of daylighting, but the design likely considers daylight access given the building’s use of modular systems and space planning | 1 |

| Passive solar heating/shading | No data | 0 |

| Natural ventilation | No mention of natural ventilation, though mechanical systems are in place | 0 |

| Thermal mass | No specific mention of thermal mass, but the reinforced concrete core may provide some passive thermal regulation. | 1 |

| Strategy | Notes/Description | Code (0–3) |

|---|---|---|

| High—efficiency HVAC | HVAC systems likely include high-efficiency elements, though no specific mention of VFD. | 1 |

| Demand—controlled ventilation | No specific mention of demand-controlled ventilation, but likely integrated with building systems for energy savings. | 1 |

| High—efficiency lighting (LED + controls) | High-efficiency lighting, consistent with practices commonly applied in LEED-oriented projects | 2 |

| Heat recovery systems | No mention of heat recovery systems, though such systems might be integrated in advanced building management systems. | 1 |

| Building automation/BMS | The use of advanced structural elements suggests a comprehensive Building Management System (BMS) for optimized energy use. | 2 |

| Strategy | Notes/Description | Code (0–3) |

|---|---|---|

| Photovoltaic panels | No data | 0 |

| Solar thermal collectors | No data | 0 |

| Geothermal systems | No data | 0 |

| Energy storage | No data | 0 |

| Hybrid renewable solutions | No hybrid renewable systems mentioned, although sustainability certification suggests a possibility. | 0 |

| Strategy | Notes/Description | Code (0–3) |

|---|---|---|

| Low—carbon/recycled materials | The use of modular systems likely contributed to material efficiency, but no direct data on low-carbon or recycled materials. | 1 |

| Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) | No data available, but the building’s sustainable design and modular construction likely considered life cycle impacts. | 1 |

| Water—saving fixtures | No direct mention of water-saving fixtures; however, LEED-aligned water efficiency strategies are likely applied. | 2 |

| Greywater/rainwater systems | No data | 0 |

| Design for disassembly/circularity | The modular design system likely makes disassembly and reuse of materials easier, though no specific mention of circularity strategies. | 1 |

| Category | Score (Sum) | Average | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | 3 | 0.6 | |

| B | 7 | 1.4 | |

| C | 0 | 0.0 | |

| D | 5 | 1.0 |

Appendix A.13. Sustainable Development Strategy Assessment Card, International Commerce Centre

- Location: Hong Kong, China

- Assessment Date: 2 December 2025

- Assessor: Authors

- Certifications: No certification in official databases

| Strategy | Notes/Description | Code (0–3) |

|---|---|---|

| Orientation optimization | The design likely takes into account the surrounding mountains and environmental factors to optimize performance | 1 |

| Daylighting optimization | Natural atrium lighting suggests an effort to use daylight efficiently. | 2 |

| Passive solar heating/shading | Low-emission curtain wall helps to minimize solar heat gain while allowing daylight. | 2 |

| Natural ventilation | No mention of natural ventilation, though mechanical HVAC systems are in place. | 0 |

| Thermal mass | No specific mention of thermal mass, but low-emission glass and efficient systems help regulate indoor temperatures. | 1 |

| Strategy | Notes/Description | Code (0–3) |

|---|---|---|

| High—efficiency HVAC | The building utilizes a water-cooled chiller with centrifugal separator to improve HVAC efficiency. | 3 |

| Demand—controlled ventilation | No specific mention, but the BMS and energy-efficient systems likely enable demand-controlled ventilation. | 2 |

| High—efficiency lighting (LED + controls) | Energy-efficient lighting fixtures are used throughout the building. | 2 |

| Heat recovery systems | No mention of specific heat recovery systems, though the BMS may control heating and cooling. | 1 |

| Building automation/BMS | The computer-aided Building Management System (BMS) enables energy monitoring and management. | 3 |

| Strategy | Notes/Description | Code (0–3) |

|---|---|---|

| Photovoltaic panels | No data | 0 |

| Solar thermal collectors | No data | 0 |

| Geothermal systems | No data | 0 |

| Energy storage | No data | 0 |

| Hybrid renewable solutions | No data | 0 |

| Strategy | Notes/Description | Code (0–3) |

|---|---|---|

| Low—carbon/recycled materials | While there is no direct mention of low-carbon or recycled materials, it likely includes sustainable materials. | 1 |

| Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) | No data available, but energy saving systems and building design likely incorporate life cycle analysis (LCA) | 1 |

| Water—saving fixtures | No specific mention, but the energy-efficient systems and cooling technology suggest that water conservation measures are in place. | 2 |

| Greywater/rainwater systems | No data | 0 |

| Design for disassembly/circularity | No data on design for disassembly, though the building’s waste management program indicates some consideration of sustainability in material. | 1 |

| Category | Score (Sum) | Average | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | 6 | 1.2 | |

| B | 11 | 2.2 | |

| C | 0 | 0.0 | |

| D | 5 | 1.0 |

- A water-cooled chiller and a building management system (BMS) are key technologies that help reduce energy consumption.

- The building’s commitment to energy efficiency is reflected in low-emission curtain walls, natural lighting systems, and energy-efficient lighting fixtures.

Appendix A.14. Sustainable Development Strategy Assessment Card, Wuhan Greenland Center

- Location: Wuhan, China

- Assessment Date: 2 December 2025

- Assessor: Authors

- Certifications: No certification in official databases

| Strategy | Notes/Description | Code (0–3) |

|---|---|---|

| Orientation optimization | No direct mention, but the conical and aerodynamic design likely optimizes wind load management. | 1 |

| Daylighting optimization | The lighting system responds to daylight, automatically turning off electric lighting when sufficient daylight is available. | 2 |

| Passive solar heating/shading | No explicit mention of passive solar heating, but the building’s form likely reduces solar gain at different levels. | 1 |

| Natural ventilation | No data on natural ventilation, though mechanical ventilation with energy recovery is in place. | 0 |

| Thermal mass | The building’s design uses its form to contribute to passive heating and cooling strategies. | 1 |

| Strategy | Notes/Description | Code (0–3) |

|---|---|---|

| High—efficiency HVAC | The system uses energy recovery through an enthalpy wheel in the ventilation system. | 2 |

| Demand—controlled ventilation | The ventilation system adjusts based on the indoor air quality. | 1 |

| High—efficiency lighting (LED + controls) | The lighting system uses energy-efficient ballasts and lamps, controlled by daylight sensors. | 2 |

| Heat recovery systems | Energy recovery using the enthalpy wheel integrated into the ventilation system. | 2 |

| Building automation/BMS | The building’s lighting and HVAC systems are controlled by automation systems. | 2 |

| Strategy | Notes/Description | Code (0–3) |

|---|---|---|

| Photovoltaic panels | No data | 0 |

| Solar thermal collectors | No data | 0 |

| Geothermal systems | No data | 0 |

| Energy storage | No data | 0 |

| Hybrid renewable solutions | No data | 0 |

| Strategy | Notes/Description | Code (0–3) |

|---|---|---|

| Low—carbon/recycled materials | No data | 0 |

| Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) | No data | 0 |

| Water—saving fixtures | The building includes low-flow fixtures to conserve water. | 2 |

| Greywater/rainwater systems | A graywater system recycles water from laundry, sinks, and showers for cooling. | 2 |

| Design for disassembly/circularity | No data | 0 |

| Category | Score (Sum) | Average | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | 5 | 1.0 | |

| B | 9 | 1.8 | |

| C | 0 | 0 | |

| D | 4 | 0.8 |

Appendix A.15. Sustainable Development Strategy Assessment Card, Central Park Tower

- Location: New York City, USA

- Assessment Date: 2 December 2025

- Assessor: Authors

- Certifications: No certification in official databases

| Strategy | Notes/Description | Code (0–3) |

|---|---|---|

| Orientation optimization | No direct mention of orientation optimization, though the cantilevered design may help reduce wind load on the building. | 1 |

| Daylighting optimization | No mention of daylighting optimization. However, the glass curtain wall might allow natural light into the building. | 1 |

| Passive solar heating/shading | No mention of passive solar heating or shading strategies. | 0 |

| Natural ventilation | No data on natural ventilation; the building appears to rely on mechanical systems. | 0 |

| Thermal mass | No data | 0 |

| Strategy | Notes/Description | Code (0–3) |

|---|---|---|

| High—efficiency HVAC | The building features advanced mechanical systems, including heat exchangers, air handling units, and exhaust systems. | 2 |

| Demand—controlled ventilation | The advanced mechanical systems suggest that the BMS might optimize ventilation | 1 |

| High—efficiency lighting (LED + controls) | The advanced mechanical systems imply energy-efficient systems, including lighting controls. | 1 |

| Heat recovery systems | The building features heat exchangers, which suggests that some level of heat recovery is integrated into the HVAC system. | 2 |

| Building automation/BMS | BMS system | 3 |

| Strategy | Notes/Description | Code (0–3) |

|---|---|---|

| Photovoltaic panels | No data | 0 |

| Solar thermal collectors | No data | 0 |

| Geothermal systems | No data | 0 |

| Energy storage | No data | 0 |

| Hybrid renewable solutions | No data | 0 |

| Strategy | Notes/Description | Code (0–3) |

|---|---|---|

| Low—carbon/recycled materials | No data | 0 |

| Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) | No data | 0 |

| Water—saving fixtures | No data | 0 |

| Greywater/rainwater systems | No data | 0 |

| Design for disassembly/circularity | No data | 0 |

| Category | Score (Sum) | Average | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | 2 | 0.4 | |

| B | 9 | 1.8 | |

| C | 0 | 0 | |

| D | 0 | 0 |

Appendix A.16. Sustainable Development Strategy Assessment Card, Lakhta Center

- Location: St. Petersburg, Russia

- Assessment Date: 2 December 2025

- Assessor: Authors

- Certifications: Tower: LEED BD + C: Core and Shell, Platinum, 82/110

| Strategy | Notes/Description | Code (0–3) |

|---|---|---|

| Orientation optimization | No data | 0 |

| Daylighting optimization | No direct mention, but the building’s design likely allows natural light through the façade. | 1 |

| Passive solar heating/shading | No mention of passive solar heating or shading; however, the design might help reduce solar gain through its unique structure. | 1 |

| Natural ventilation | No data | 0 |

| Thermal mass | No data | 0 |

| Strategy | Notes/Description | Code (0–3) |

|---|---|---|

| High—efficiency HVAC | The building is designed to use heat generated by technical equipment for space heating, which suggests a high-efficiency HVAC system. | 2 |

| Demand—controlled ventilation | No specific mention of demand-controlled ventilation, but the high-efficiency HVAC system likely optimizes air quality and temperature. | 1 |

| High—efficiency lighting (LED + controls) | No mention of specific lighting systems, though it is implied that energy efficiency is part of the building’s design. | 1 |

| Heat recovery systems | Heat from technical equipment is used for space heating, indicating an efficient heat recovery system. | 2 |

| Building automation/BMS | No specific mention, but LEED Platinum certification suggests that a BMS system is used to optimize building systems. | 3 |

| Strategy | Notes/Description | Code (0–3) |

|---|---|---|

| Photovoltaic panels | No data | 0 |

| Solar thermal collectors | No data | 0 |

| Geothermal systems | No data | 0 |

| Energy storage | No data | 0 |

| Hybrid renewable solutions | No data | 0 |

| Strategy | Notes/Description | Code (0–3) |

|---|---|---|

| Low—carbon/recycled materials | No data | 0 |

| Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) | The building earned LEED Platinum certification, which suggests some assessment of the building’s lifecycle impacts. | 1 |

| Water—saving fixtures | The building scored 10/10 in water efficiency under LEED, implying the use of water-saving fixtures. | 3 |

| Greywater/rainwater systems | No data | 0 |

| Design for disassembly/circularity | No data | 0 |

| Category | Score (Sum) | Average | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | 2 | 0.4 | Passive strategies are limited |

| B | 9 | 1.8 | |

| C | 0 | 0 | No renewable energy systems implemented. |

| D | 4 | 0.8 |

Appendix A.17. Sustainable Development Strategy Assessment Card, Vincom Landmark 81

- Location: Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam

- Assessment Date: 2 December 2025

- Assessor: Authors

- Certifications: No certification in official databases

| Strategy | Notes/Description | Code (0–3) |

|---|---|---|

| Orientation optimization | No data | 0 |

| Daylighting optimization | The use of environmentally friendly windows, which can improve energy efficiency, suggests optimizing natural lighting. | 2 |

| Passive solar heating/shading | No data | 0 |

| Natural ventilation | No data, probably HVAC | 0 |

| Thermal mass | The design uses a “thick base supported by piles” and “environmentally friendly windows” (which may indicate thermal insulation), it can be assumed that thermal mass elements were used | 1 |

| Strategy | Notes/Description | Code (0–3) |

|---|---|---|

| High—efficiency HVAC | The building with an advanced water management system and energy-efficient windows suggests that HVAC technology has been used | 2 |

| Demand—controlled ventilation | No data | 0 |

| High—efficiency lighting (LED + controls) | Given that the building is modern and has elements of sustainable development, it can be assumed that efficient lighting was used. | 2 |

| Heat recovery systems | No data | 0 |

| Building automation/BMS | An advanced water management system suggests there is also a building automation system (BMS) | 2 |

| Strategy | Notes/Description | Code (0–3) |

|---|---|---|

| Photovoltaic panels | No data | 0 |

| Solar thermal collectors | No data | 0 |

| Geothermal systems | No data | 0 |

| Energy storage | No data | 0 |

| Hybrid renewable solutions | No data | 0 |

| Strategy | Notes/Description | Code (0–3) |

|---|---|---|

| Low—carbon/recycled materials | Ecological windows, suggest the use of energy-saving materials | 1 |

| Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) | No data | 0 |

| Water—saving fixtures | The building is equipped with an advanced water management system, which suggests the use of water-saving devices | 2 |

| Greywater/rainwater systems | No data | 0 |

| Design for disassembly/circularity | No data | 0 |

| Category | Score (Sum) | Average | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | 3 | 0.6 | |

| B | 6 | 1.2 | Focus on energy efficiency and automation |

| C | 0 | 0 | No renewable energy integration |

| D | 3 | 0.6 | Limited focus on materials and water management |

Appendix A.18. Sustainable Development Strategy Assessment Card, Changsha IFS Tower T1 (Prada Changsha IFS)

- Location: Changsha, China

- Assessment Date: 2 December 2025

- Assessor: Authors

- Certifications: LEED O + M: Existing Buildings v4 standard—LEED v4 Platinum, scoring 83/110 points; LEED O + M: Existing Buildings v4 standard—LEED v4 Platinum, 83/110

| Strategy | Notes/Description | Code (0–3) |

|---|---|---|

| Orientation optimization | No data | 0 |

| Daylighting optimization | Glass facade—high level of natural lighting | 1 |

| Passive solar heating/shading | No data, metal “ribs” may reduce radiation | 1 |

| Natural ventilation | No data, probably HVAC | 0 |

| Thermal mass | The reinforced concrete core provides thermal mass | 1 |

| Strategy | Notes/Description | Code (0–3) |

|---|---|---|

| High—efficiency HVAC | LEED Platinum and Energy & Atmosphere category 28/56—high HVAC efficiency | 3 |

| Demand—controlled ventilation | LEED Indoor Environmental Quality—good results (8/17)—likely use of ventilation control | 2 |

| High—efficiency lighting (LED + controls) | Typical for LEED Platinum buildings, although no direct information is available | 2 |

| Heat recovery systems | LEED EA high score—most likely used | 1 |

| Building automation/BMS | Premium class building + LEED O+M: monitoring and automation necessary | 3 |

| Strategy | Notes/Description | Code (0–3) |

|---|---|---|

| Photovoltaic panels | No data, LEED EA score does not indicate renewable energy | 0 |

| Solar thermal collectors | No data | 0 |

| Geothermal systems | No data | 0 |

| Energy storage | No data | 0 |

| Hybrid renewable solutions | No data | 0 |

| Strategy | Notes/Description | Code (0–3) |

|---|---|---|

| Low—carbon/recycled materials | LEED Materials & Resources: 6/8—very good results indicate a high level of implementation | 3 |

| Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) | LEED MR partially assumes LCA; high scores suggest use | 2 |

| Water—saving fixtures | LEED Water Efficiency: 11/12—very high-water savings | 3 |

| Greywater/rainwater systems | Possible due to high WE score | 1 |

| Design for disassembly/circularity | No data | 0 |

| Category | Score (Sum) | Average | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | 3 | 0.6 | |

| B | 11 | 2.2 | Very powerful active systems and energy efficiency |

| C | 0 | 0.0 | |

| D | 9 | 1.8 | Very strong water-materials strategies thanks to LEED Platinum |

- There is a lack of implementation of renewable energy sources and strong passive design strategies.

- Green roofs improve user well-being, but they serve an environmental function more at the micro level than at the energy level.

Appendix A.19. Sustainable Development Strategy Assessment Card, Petronas Twin

- Location: Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

- Assessment Date: 2 December 2025

- Assessor: Authors

- Certifications: GBI Rating, Gold (validity date: 21 June 2019–22 June 2022)

| Strategy | Notes/Description | Code (0–3) |

|---|---|---|

| Orientation optimization | No data | 0 |

| Daylighting optimization | Large glazing, but no evidence of design for this purpose | 1 |

| Passive solar heating/shading | Lack of information on sun protection strategies beyond the facade | 0 |

| Natural ventilation | A mechanically air-conditioned skyscraper, no natural ventilation | 0 |

| Thermal mass | The reinforced concrete core and columns provide thermal mass | 1 |

| Strategy | Notes/Description | Code (0–3) |

|---|---|---|

| High—efficiency HVAC | No information on HVAC upgrades; only basic GBI Gold upgrades available | 1 |

| Demand—controlled ventilation | No data | 0 |

| High—efficiency lighting (LED + controls) | Energy-saving lighting | 2 |

| Heat recovery systems | No data | 0 |

| Building automation/BMS | Premium class building, but no data on the modernization of the BMS system | 1 |

| Strategy | Notes/Description | Code (0–3) |

|---|---|---|

| Photovoltaic panels | No data | 0 |

| Solar thermal collectors | No data | 0 |

| Geothermal systems | No data | 0 |

| Energy storage | No data | 0 |

| Hybrid renewable solutions | No data | 0 |

| Strategy | Notes/Description | Code (0–3) |

|---|---|---|

| Low—carbon/recycled materials | Featured biodegradable materials, recyclates, low-VOC products | 2 |

| Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) | No data | 0 |

| Water—saving fixtures | Installing energy-efficient flushing systems—one of the main improvements | 2 |

| Greywater/rainwater systems | No data | 0 |

| Design for disassembly/circularity | No data | 0 |

| Category | Score (Sum) | Average | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | 2 | 0.4 | Minimal passive strategies, typical of 1990s projects |

| B | 5 | 1.0 | |

| C | 0 | 0.0 | |

| D | 4 | 0.8 |

References

- Starzyk, A.; Rybak-Niedziółka, K.; Nowysz, A.; Marchwiński, J.; Kozarzewska, A.; Koszewska, J.; Piętocha, A.; Vietrova, P.; Łacek, P.; Donderewicz, M.; et al. New Zero-Carbon Wooden Building Concepts: A Review of Selected Criteria. Energies 2024, 17, 4502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravinder, B. Rethinking construction: From linear to circular economy through conceptual frameworks. J. Appl. Bioanal. 2025, 11, 372–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, D.; Liu, J.; Wu, H.; Zhang, G.; Pan, Z.; Huang, J. Advancing Smart Net-Zero Energy Buildings with Renewable Energy and Electrical Energy Storage. J. Energy Storage 2025, 131, 115850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bijlani, V.A. Smart Green Buildings for Advancing Corporate Social Responsibility Goals. In Global Corporate Governance; Nedzel, N.E., Idowu, S.O., Diaz Diaz, B., Guia Arraiano, I., Schmidpeter, R., Eds.; CSR, Sustainability, Ethics & Governance; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 43–72. ISBN 978-3-031-86329-5. [Google Scholar]

- Acuto, M. High-Rise Dubai Urban Entrepreneurialism and the Technology of Symbolic Power. Cities 2010, 27, 272–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Zhang, J.; Cai, J. Influences of New High-Rise Buildings on Visual Preference Evaluation of Original Urban Landmarks: A Case Study in Shanghai, China. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2020, 19, 273–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Environment Programme. Not Just Another Brick in the Wall: The Solutions Exist—Scaling Them Will Build on Progress and Cut Emissions Fast. In Global Status Report for Buildings and Construction 2024/2025; United Nations Environment Programme: Washington DC, USA, 2025; ISBN 978-92-807-4215-2. [Google Scholar]

- Piętocha, A. The BREEAM, the LEED and the DGNB Certifications as an Aspect of Sustainable Development. Acta Sci. Pol. Archit. 2024, 23, 121–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piętocha, A.; Li, W.; Koda, E. The Vertical City Paradigm as Sustainable Response to Urban Densification and Energy Challenges: Case Studies from Asian Megacities. Energies 2025, 18, 5278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, L.; Duan, K.; Tang, X. What Is the Relationship Between Technological Innovation and Energy Consumption? Empirical Analysis Based on Provincial Panel Data from China. Sustainability 2018, 10, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leite Ribeiro, L.M.; Piccinini Scolaro, T.; Ghisi, E. LEED Certification in Building Energy Efficiency: A Review of Its Performance Efficacy and Global Applicability. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, A.; Pinheiro, M.D.; Brito, J.D.; Mateus, R. A Critical Analysis of LEED, BREEAM and DGNB as Sustainability Assessment Methods for Retail Buildings. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 66, 105825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awadh, O. Sustainability and Green Building Rating Systems: LEED, BREEAM, GSAS and Estidama Critical Analysis. J. Build. Eng. 2017, 11, 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, S.; Zoghi, M.; Blázquez, T.; Dall’O’, G. New Level(s) Framework: Assessing the Affinity Between the Main International Green Building Rating Systems and the European Scheme. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 155, 111924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akçay, C.; Sarı, M. Sustainable Healthcare Infrastructure: Design-Phase Evaluation of LEED Certification and Energy Efficiency at Istanbul University’s Surgical Sciences Building. Buildings 2025, 15, 2385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, D.H.; Kim, B.; Lee, J.; Ahn, Y. An Investigation of the Selection of LEED Version 4 Credits for Sustainable Building Projects. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 7081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazur, Ł.; Resler, M.; Koda, E.; Walasek, D.; Daria Vaverková, M. Energy Saving and Green Building Certification: Case Study of Commercial Buildings in Warsaw, Poland. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2023, 60, 103520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.M.; Al-Kodmany, K.; Armstrong, P.J. Energy Efficiency of Tall Buildings: A Global Snapshot of Innovative Design. Energies 2023, 16, 2063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebelatto, B.G.; Salvia, A.L.; Brandli, L.L.; Leal Filho, W. Examining Energy Efficiency Practices in Office Buildings Through the Lens of LEED, BREEAM, and DGNB Certifications. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Shammari, M.; Al-juboori, O.A.; Erzaij, K. Analytical Comparison of Leading Sustainability Systems in the Iraqi Environment. E3S Web Conf. 2024, 586, 01003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulya, K.S.; Ng, W.L.; Biró, K.; Ho, W.S.; Wong, K.Y.; Woon, K.S. Decarbonizing the High-Rise Office Building: A Life Cycle Carbon Assessment to Green Building Rating Systems in a Tropical Country. Build. Environ. 2024, 255, 111437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, S.; Ryan, G.; Marino, M.; Gharehbaghi, K. The Green Design of High-Rise Buildings: How Is the Construction Industry Evolving. Technol. Sustain. 2023, 2, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Na, L.T.H.; Vi, L.T.H. An Analysis of Passive Design Strategy for Diamond Lotus Riverside High-Rise Apartment Project in Ho Chi Minh City. In Proceedings of the Third International Conference on Sustainable Civil Engineering and Architecture, Da Nang City, Vietnam, 19–21 July 2023; Reddy, J.N., Wang, C.M., Luong, V.H., Le, A.T., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Civil Engineering; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2024; Volume 442, pp. 51–56. ISBN 978-981-99-7433-7. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Kodmany, K. The Sustainability of Tall Building Developments: A Conceptual Framework. Buildings 2018, 8, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat. CTBUH Height Criteria: For Measuring & Defining Tall Buildings [PDF]; CTBUH: Chicago, IL, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Abdelrazaq, A.K. Design and Construction of Merdeka 118 Tower Using High Performance Concrete: Pushing the Boundaries of Concrete Technology for a Megatall Building. Rev. ALCONPAT 2025, 15, 175–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van, H.C. Raft Thickness Rational Design for Megatall Skyscrapers: Case Studies. Eng. Technol. Appl. Sci. Res. 2024, 14, 14781–14787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Zheng, C.; Lu, D.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Jin, Z.; Zhang, Z. Effects of Wind Shields on Pedestrian-Level Wind Environment Around Outdoor Platforms of a Megatall Building. Atmosphere 2024, 15, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Z.; Lu, W.; Fan, Y.; Gao, Y. Automated Simplified Structural Modeling Method for Megatall Buildings Based on Genetic Algorithm. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 77, 107485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.; Zheng, C.; Liu, H. Effects of Corner-Recession on Wind-Induced Responses and Aerodynamic Damping of a Square Megatall Building Under Twisted Wind Flow. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 75, 107018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusuf, D.A.; Ahmed, A.; Sagir, A.; Yusuf, A.A.; Yakubu, A.; Zakari, A.T.; Usman, A.M.; Nashe, A.S.; Hamma, A.S. A Review of Conceptual Design and Self Health Monitoring Program in a Vertical City: A Case of Burj Khalifa, U.A.E. Buildings 2023, 13, 1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.-H.; Zhang, G.; Zuo, J.; Lindsay, S. Sustainable High-Rise Design Trends—Dubai’s Strategy. Civ. Eng. Archit. 2013, 1, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konar, T. Mega-Tall Buildings: Current Trends, Challenges and Future Prospects. Discov. Civ. Eng. 2025, 2, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B. A Practical Study of LEED Certification for the Shanghai Tower Building Project. Int. J. Glob. Econ. Manag. 2024, 3, 183–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Han, X.; Li, Q.; Zhu, H.; He, Y. Monitoring of Wind Effects on 600 m High Ping-An Finance Center during Typhoon Haima. Eng. Struct. 2018, 167, 308–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poon, D.C.K.; Hsiao, L.; Zhu, Y.; Pacitto, S.; Zuo, S.; Gottlebe, T.; Srikonda, R. Performance-Based Seismic Evaluation of Ping An International Finance Center. In Proceedings of the Structures Congress 2011, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 14–16 April 2011; American Society of Civil Engineers: Las Vegas, NV, USA, 2011; pp. 983–993. [Google Scholar]

- Park, H.S.; Oh, B.K. Real-Time Structural Health Monitoring of a Supertall Building Under Construction Based on Visual Modal Identification Strategy. Autom. Constr. 2018, 85, 273–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golasz-Szołomicka, H.; Szołomicki, J. Wieżowiec One World Trade Center w Nowym Jorku—Współczesny Ekologiczny Biurowiec o Hybrydowej Konstrukcji. Bud. Archit. 2018, 17, 141–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L. Citic Tower Construction Key Technology. Int. J. High-Rise Build. 2019, 8, 185–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Cheng, Y.; Zhu, Y.-S. The Structural Design of “China Zun” Tower, Beijing. Int. J. High-Rise Build. 2016, 5, 213–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Kodmany, K. Green Retrofitting Skyscrapers: A Review. Buildings 2014, 4, 683–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, W.; Shan, J.; Lu, X. Modal Identification of Shanghai World Financial Center Both from Free and Ambient Vibration Response. Eng. Struct. 2012, 36, 14–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, G.; Li, Y.; Kong, H.; Liu, L.; Zhang, C. Field Measurements of Wind-Induced Responses of the Shanghai World Financial Center during Super Typhoon Lekima. Sensors 2023, 23, 6519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 50001; Energy Management Systems is an International Standard Created by the International Organization for Standardization (ISO), 2011 ISO 50001 (1st Edition). Available online: https://www.iso.org/iso-50001-energy-management.html (accessed on 19 December 2025).

- Al-Kodmany, K. Sustainability and the 21st Century Vertical City: A Review of Design Approaches of Tall Buildings. Buildings 2018, 8, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Travush, V.I.; Shulyat’ev, O.A.; Shulyat’ev, S.O.; Shakhraman’yan, A.M.; Kolotovichev, Y.A. Analysis of the Results of Geotechnical Monitoring of “Lakhta Center” Tower. Soil Mech. Found Eng. 2019, 56, 98–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong, Q.T.; Phan, T.H.; Pham, Q.D.; Pham, H.N. Design and Construction Solution of Foundation for Landmark 81—The Tallest Tower in Vietnam. In Proceedings of the Geo-Congress 2020, Minneapolis, MN, USA, 25–28 February 2020; American Society of Civil Engineers: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2020; pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Yu, M.; Zhuang, S.; Qian, Y.; Feng, R. Modal Analysis and Harmonic Response Analysis of the Petronas Twin Towers. Appl. Comput. Eng. 2023, 10, 316–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouka, D.; Russo, M.; Barreca, F. Building Sustainability Assessment: A Comparison Between ITACA, DGNB, HQE and SBTool Alignment with the European Green Deal. Heliyon 2024, 10, e34478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golański, M.; Juchimiuk, J.; Podlasek, A.; Starzyk, A. Design for Manufacturing and Assembly (DfMA) in Timber Construction: Advancing Energy Efficiency and Climate Neutrality in the Built Environment. Energies 2025, 18, 6332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristoffersen, A.E.; Schultz, C.P.L.; Kamari, A. A Critical Comparison of Concepts and Approaches to Social Sustainability in the Construction Industry. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 91, 109530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiri, A.; Ottelin, J.; Sorvari, J. Are LEED-Certified Buildings Energy-Efficient in Practice? Sustainability 2019, 11, 1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsirovasilis, E.; Katafygiotou, M.; Psathiti, C. Comparative Assessment of LEED, BREEAM, and WELL: Advancing Sustainable Built Environments. Energies 2025, 18, 4322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, D.H.; Zhang, C.; Di Maio, F.; Hu, M. Potential of BREEAM-C to Support Building Circularity Assessment: Insights from Case Study and Expert Interview. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 442, 140836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafez, F.S.; Sa’di, B.; Safa-Gamal, M.; Taufiq-Yap, Y.H.; Alrifaey, M.; Seyedmahmoudian, M.; Stojcevski, A.; Horan, B.; Mekhilef, S. Energy Efficiency in Sustainable Buildings: A Systematic Review with Taxonomy, Challenges, Motivations, Methodological Aspects, Recommendations, and Pathways for Future Research. Energy Strategy Rev. 2023, 45, 101013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Hu, Y.; Wang, R.; Li, X.; Chen, Z.; Hua, J.; Osman, A.I.; Farghali, M.; Huang, L.; Li, J.; et al. Green Building Practices to Integrate Renewable Energy in the Construction Sector: A Review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2024, 22, 751–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, W.; Shafique, M.; Luo, X. Achieving Net-Zero Emissions in China’s Building Sector: Critiques and Strategies of Minimizing Embodied Carbon. Energy Build. 2025, 345, 115878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayasgalan, A.; Park, Y.S.; Koh, S.B.; Son, S.-Y. Comprehensive Review of Building Energy Management Models: Grid-Interactive Efficient Building Perspective. Energies 2024, 17, 4794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, T.; Wang, J.; Wang, R.; Chow, D.; Nan, H.; Zhang, K.; Fang, Y. Multi-Objective Optimization for the Energy, Economic, and Environmental Performance of High-Rise Residential Buildings in Areas of Northwestern China with Different Solar Radiation. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 6719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schützenhofer, S.; Kovacic, I.; Rechberger, H.; Mack, S. Improvement of Environmental Sustainability and Circular Economy Through Construction Waste Management for Material Reuse. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almusaed, A.; Yitmen, I.; Myhren, J.A.; Almssad, A. Assessing the Impact of Recycled Building Materials on Environmental Sustainability and Energy Efficiency: A Comprehensive Framework for Reducing Greenhouse Gas Emissions. Buildings 2024, 14, 1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Ye, X.; Cui, H. Recycled Materials in Construction: Trends, Status, and Future of Research. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Z.; Yang, G.; Zhang, T.; Tian, W. Aerodynamic Performance Analysis of a Building-Integrated Savonius Turbine. Energies 2020, 13, 2636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.; Chen, Y.; McDowall, W.; Türkeli, S.; Bleischwitz, R.; Geng, Y. Embodied GHG Emissions of Building Materials in Shanghai. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 210, 777–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elnimeiri, M.M.; Hwang, Y. Towards Sustainable Structure of Tall Buildings by Significantly Reducing the Embodied Carbon. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Fang, Y.; Feng, W.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, G.X. How to Minimise the Carbon Emission of Steel Building Products from a Cradle-to-Site Perspective: A Systematic Review of Recent Global Research. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 368, 133156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, C.; Ren, C.; Wang, J.; Feng, Z.; Cao, S.-J. Impacts of Urban-Scale Building Height Diversity on Urban Climates: A Case Study of Nanjing, China. Energy Build. 2021, 251, 111350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimian, A.; Udilovich, K.; Shleykov, I.; Kelly, D.; Garber, J. On Performance-Based Wind Design of Tall Buildings. J. Wind. Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 2025, 267, 106248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Kodmany, K. The Vertical City: A Sustainable Development Model; WIT Press: Southampton, UK; Boston, MA, USA, 2018; ISBN 978-1-78466-257-8. [Google Scholar]

- Zhaoa, X.; Ding, J.M.; Suna, H.H. Structural Design of Shanghai Tower for Wind Loads. Procedia Eng. 2011, 14, 1759–1767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Zhao, Z.; Wang, S.; Xu, Y.; Qin, Z.; Li, K.; Kim, B. Impact of Sloped Terrain on Wind Loads in High-Rise Buildings: An Experimental Wind Tunnel Investigation. J. Wind. Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 2025, 264, 106156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASCE/SEI 7-22; ASCE 7: Minimum Design Loads and Associated Criteria for Buildings and Other Structures (ASCE/SEI 7-22). American Society of Civil Engineers: Reston, VA, USA, 2022.

- GB 50009-2012; Load Code For The Design of Building Structures, National Standard of the People’s Republic of China. Ministry of Housing Urban-Rural Construction of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China. Available online: https://www.scribd.com/document/722382313/GB-50009-2012-Load-code-for-the-design-of-building-structures (accessed on 19 December 2025).

- Eissa, M.; Metwally, O.; Alawode, K.J.; Elawady, A.; Lori, G. Performance of High-Rise Building Façades Under Wind Loading: A State-of-the-Art Review. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 113, 114072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslantamer, Ö.N.; Ilgın, H.E. Space Efficiency of Tall Buildings in Singapore. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 8397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilgın, H.E. A Study on Interrelations of Structural Systems and Main Planning Considerations in Contemporary Supertall Buildings. Int. J. Build. Pathol. Adapt. 2023, 41, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivasuriyan, A.; Vijayan, D.S.; Górski, W.; Wodzyński, Ł.; Vaverková, M.D.; Koda, E. Practical Implementation of Structural Health Monitoring in Multi-Story Buildings. Buildings 2021, 11, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigonah, N.; Khaksar, R.Y.; Fathollahi-Fard, A.M.; Gheibi, M.; Wacławek, S.; Moezzi, R. Seismic Stability and Sustainable Performance of Diaphragm Walls Adjacent to Tunnels: Insights from 2D Numerical Modeling and Key Factors. Buildings 2023, 14, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widjaja, D.D.; Khant, L.P.; Kim, S.; Kim, K.Y. Optimization of Rebar Usage and Sustainability Based on Special-Length Priority: A Case Study of Mechanical Couplers in Diaphragm Walls. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayan, D.S.; Sivasuriyan, A.; Devarajan, P.; Krejsa, M.; Chalecki, M.; Żółtowski, M.; Kozarzewska, A.; Koda, E. Development of Intelligent Technologies in SHM on the Innovative Diagnosis in Civil Engineering—A Comprehensive Review. Buildings 2023, 13, 1903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Name | City and Country | Completion | Height | Floors | Material | Function | Certifications | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Burj Khalifa | Dubai, United Arab Emirates | 2010 | 828 | 163 | Steel over concrete | Office/Residential/Hotel | LEED Platinum certification under the v4.1 Operations and Maintenance: Existing Buildings (2024) |

| 2 | Merdeka 118 | Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia | 2023 | 679 | 118 | Concrete–Steel Composite | Hotel/Serviced Apartments/Office | LEED Platinum, 86/110, (LEED BD+C: Core and Shell) |

| 3 | Shanghai Tower | Shanghai, China | 2015 | 632 | 128 | Concrete–Steel Composite | Hotel/Office | LEED Platinum BD+C: Core and Shell, 82/100, China Green Building Three-Star rating for Energy Efficiency |

| 4 | Makkah Royal Clock Tower | Mecca, Saudi Arabia | 2012 | 601 | 120 | Steel over concrere | Serviced Apartments/Hotel/Retail | - |

| 5 | Ping An Finance Centre | Shenzen, China | 2017 | 599 | 115 | Concrete–Steel Composite | Office | LEED Platinum (Operations and Maintenance: Existing Buildings), LEED Gold (Core and Shell), BREAAM, Three Star |

| 6 | Lotte World Tower | Seoul, South Korea | 2017 | 555 | 123 | Concrete–Steel Composite | Hotel/Residential/Office/Retail | LEED BD+C: New Construction, Gold, 66/110 |

| 7 | One World Trade Center | New York City, United States | 2014 | 541 | 94 | Concrete–Steel Composite | Office | LEED Gold BD+C, 37/62 |

| 8/9 | Guangzhou CTF Finance Centre | Guangzhou, China | 2016 | 530 | 111 | Composite | Hotel/Residential/Office | Hotel: LEED BD+C: New Construction, Gold 61/100 Office/Retail: LEED BD+C: Core and Shell |

| 8/9 | Tianjin CTF Finance Centre | Tianjin, China | 2019 | 530 | 97 | Concrete–Steel Composite | Hotel/Serviced Apartments/Office | LEED Gold |

| 10 | CITIC Tower | Beijing, China | 2018 | 528 | 109 | Concrete–Steel Composite | Office | LEED-CS Gold Pre-certification, China Certificate of Green Building Label—Three Star |

| 11 | TAIPEI 101 | Taipei, China | 2004 | 508 | 101 | Composite | Office | LEED Platinum (2011) LEED Platinum O+M: Existing Buildings (2016) LEED Re-certification Platinum (2021) |

| 12 | Shanghai World Financial Center | Shanghai, China | 2008 | 492 | 101 | Concrete–Steel Composite | Hotel/Office | - |

| 13 | International Commerce Centre | Hong Kong, China | 2010 | 484 | 108 | Concrete–Steel Composite | Hotel/Office | - |

| 14 | Wuhan Greenland Center | Wuhan, China | 2023 | 476 | 101 | Concrete–Steel Composite | Hotel/Serviced Apartments/Office | - |

| 15 | Central Park Tower | New York City, United States | 2020 | 472 | 98 | All-Concrete | Residential/Retail | - |

| 16 | Lakhta Center | St. Petersburg, Russia | 2019 | 462 | 87 | Concrete–Steel Composite | Office | Tower: LEED BD+C: Core and Shell, Platinum, 82/110 |

| 17 | Vincom Landmark 81 | Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam | 2018 | 461 | 81 | Concrete–Steel Composite | Hotel/Residential | - |

| 18 | Changsha IFS Tower T1 (Prada Changsha IFS) | Changsha, China | 2018 | 452 | 94 | Concrete–Steel Composite | Hotel/Office | LEED O+M: Existing Buildings v4 standard—LEED v4 Platinum, 83/110 |

| 19/20 | Petronas Twin Tower 1 | Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia | 1988 | 452 | 88 | Concrete–Steel Composite | Office | GBI Rating, Gold (validity date: 21 June 2019–22 June 2022) |

| 19/20 | Petronas Twin Tower 2 | Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia | 1988 | 452 | 88 | Concrete–Steel Composite | Office | GBI Rating, Gold (validity date: 21 June 2019–22 June 2022) |

| Name | City and Country | Completion | Height | Floors | Material | Function | Energy Label | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Burj Binghatti Jacob | Dubai, United Arab Emirates | 2026 | 595 | 105 | N/A | Residential | no information |

| 2 | Six Senses Residences | Dubai, United Arab Emirates | 2028 | 517 | 125 | All-Concrete | Residential | no information |

| 3 | China International Silk Road Center | Xi’an, China | N/A | 498 | 101 | Concrete–Steel Composite | Hotel/Office | no information |

| 4 | Tianfu Center | Chengdu, China | 2027 | 489 | 95 | N/A | Office/Exhibition | no information |

| 5 | Rizghao Center | Rizhao | 2028 | 485 | 94 | All-Concrete | Residential/Hotel Office | no information |

| 6 | North Bund Tower | Shanghai, China | 2030 | 480 | 97 | N/A | Observation/Serviced Apartments/Hotel/Office | LEED Platinum targeted, China Three Star targeted |

| 7 | Torre Rise | Monterrey | 2026 | 475 | 88 | All-Concrete | Office/Residential/Office/Hotel | no information |

| 8 | Wuhan CTF Finance Center | Wuhan, China | 2029 | 475 | 84 | Composite | Office | LEED Gold targeted |

| 9 | Suzhou CSC Fortune Center | Suzhou, China | 2028 | 460 | 100 | Composite | Residential/Office | no information |

| 10 | International Land–Sea-Center (Architecturally Topped Out) | Chongqing, China | 2025 | 458 | 98 | Concrete–Steel Composite | Hotel/Office | LEED Gold BD+C: Core and Shell |

| Name | City and Country | Pro-Ecological Solutions and Renewable Energy | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Burj Khalifa | Dubai, United Arab Emirates | an anti-glare shield for the intense desert sun, water from air conditioning is collected via a condensate collection system and is used to irrigate the nearby park. |

| 2 | Merdeka 118 | Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia | low-emission materials, rainwater harvesting systems, smart metering devices, low-flow devices and smart building management systems, electric vehicle charging installations |

| 3 | Shanghai Tower | Shanghai, China | 270 wind turbines generate renewable energy, photovoltaics, automates environmental controls, sky gardens, double curtain wall, water recycling, double-skin façade to reduce energy use |

| 4 | Makkah Royal Clock Tower | Mecca, Saudi Arabia | no information |