Abstract

The goal of this work is to compare the effectiveness of the classical PID (Proportional Integral Derivative) controller and its extended PIDA (Proportional Integral Derivative Acceleration) version in the energy-aware context. A control system is applied to the high-order integrating system of three cascaded interconnected tanks. A complete process model of a real plant is developed in the MATLAB/Simulink environment, and system identification is carried out using PRBS signals. Hardware-in-the-Loop validation experiments use a real industrial PLC controller. The analysis addresses process variable filtering, the Smith predictor, and compensation for valve nonlinearities. The research focuses not only on control performance but also on the usage of actuators, aiming at energy-aware control. The paper proves that a properly tuned PIDA controller, particularly with a correctly configured acceleration term with appropriate filtering, provides a significant improvement in control quality and disturbance rejection. Such a system allows for the introduction and highlighting of the energy-aware context in industrial control engineering. Energy-aware control allows one not only to use less energy in control but also to lower the actuator’s operating hours, reducing its maintenance costs.

Keywords:

Hardware-in-the-Loop; PIDA; PID; filtering; feedforward; integrating plant; energy consumption 1. Introduction

Research on PID controllers, their modifications, and extensions plays a crucial role in process control. The reason for this is simple. This algorithm, no matter the industry, country, or region, can be found in the majority of control loops in the processing industry [1,2]. Some reviews identify that even over 95% [3,4] of control loops use it. Despite the fact that it is so common, only about half of PID loops operate properly, while the rest are either incorrectly designed, not well-tuned, or never tuned. Therefore, a significant number of loops operate in manual mode (MAN), which means that automatic control (AUTO) is hardly used. This occurs due to sensor or actuator errors [5]. This happens despite the well-known fact that poorly operating controllers bring financial losses [6]. The use of the PID algorithm is not limited to single-input–single-output (SISO) configuration. There exist a large number of structures and control templates that enhance the PID concept, enabling its wider applicability [7]. Recent plant-wide control systems use a decomposition to coordinate the action of several control loops and calculation blocks. Simultaneously, the PID tuning task is established, starting from Ziegler–Nichols experiments [8] up to the SIMC (Skogestad Internal Model Control) approach [9], which is effective and common in industry.

The simplified PID algorithm comes from the coordination of three elements: proportional, integral and derivative actions. They allow one to obtain fast proportional reactions and the incorporation of history included in the integrating term and accompanied by simple prediction delivered by the derivative term. The PIDA algorithm adds an acceleration term to the control rule. Feedback control system with this controller delivers a faster and smoother response than the one achievable by the PID in the case of third-order systems. The idea behind its design is to add an extra zero [10]. In conclusion, theoretical analysis [11,12] and robustness [13,14] for PIDA controllers is already addressed in the literature.

The fourth term demands more tuning attention and requires modified tuning schemes [15]. As the new algorithm is introduced, researchers try to compare it with existing PID control first [16] or similar PIDD2 [17] structures. They highlight potential benefits of its applications but at the cost of higher precision needed for higher-order systems [18]. Once the algorithm is introduced, we desire to pbtaom clear tuning rules that would allow its effective utilization and popularization. The IMC (Internal Model Control) tuning constitutes such an example as it allows tuning the PIDA algorithm for demanding, higher-order integral processes [19] or time-delayed plants [11].

On the other hand, PIDA educational tools support teaching and simulation-based understanding [20]. This aspect emphasizes the importance of proper education in the development and popularization of new concepts. Recently, PIDA controllers have been used in various applications, such as control of anesthesia depth [21], which demonstrates PIDA’s potential in areas beyond engineering. Comparison between PID and PIDA algorithms shows the advantage of PIDA in specific applications [19]. Such comparative studies mostly focus on controller performance [22], measured using classical control performance assessment (CPA) indexes, like mean square error (MSE) or mean absolute error (MAE). The reason is clear. Everyone wants to reach and sustain the highest performance.

The second issue is control system energy awareness and energy consumption by control actions themselves [23,24]. We have to be aware that each control system consumes energy itself. It is the energy spent at the execution of control actions in the form of power supply to actuating elements, like pumps, motors, or valves. This energy directly depends on certain control strategy and controller tuning. In large-scale control systems with multiple controllers, the aggregated value of the energy spent on plant actuation matters [25].

In most cases, researchers are addressing the wear and tear actuators’ perspective and their repair costs [26]. This work highlights a completely different perspective of control system operation energy awareness. Thus, common control key performance indicators (KPIs) should be enhanced. There exist three measures: quadratic manipulated variable (QMV), valve travel , and valve stroke [26,27].

This paper introduces industrial standard of the Hardware-in-the-Loop (HIL) environment [28,29] to assess PIDA control. It combines a part of the simulated system, and the rest is realized in the real hardware. The most common configuration is that the plant is simulated (for instance, in Matlab/Simulink), while the controller is implemented in physical PLC (Programmable Logic Controller) or DCS (Distributed Control System) hardware [30]. Such an approach allows one to assess almost real control performance, allowing the fast migration of the developed strategy to the real process, as the hardware is already programmed, and we only need to move it to the target destination. The HIL approach is also used to address cyber-security issues [31] or energy awareness [32].

Despite the effectiveness of the PIDA algorithm, its implementation in the process industry is rare. It is difficult to answer the question of why, as there might be many answers, for instance, the lack of dedicated PIDA blocks in control systems, the need to make custom designs, insufficient tuning competences, a poor understanding of its advantages, and the lack of knowledge about its existence. This paper addresses some of these issues. It shows how PIDA algorithms can be implemented within an industrial control system. It shows how we can safely prepare the algorithm before on-site implementation using HIL simulations. Moreover, it shows the design and construction of an entire HIL environment. It shows how to reflect reality more closely through tail-aware noise identification. Finally, it addresses practical process industry aspects, not the academic approach.

A dedicated control system with a PIDA algorithm is used to control an industrial integrating process that consists of three cascaded tanks. The real process is identified using correlation and frequency identification with a PRBS experiment. While the identified real plant is modeled and simulated with Matlab/Simulink, the PIDA algorithm is programmed in a PAC/DCS Allen–Bradley Control Logix 81ES (3MB BPCS memory, 1.5MB Safety memory) controller with the P_PIDE algorithm accompanied by an acceleration term, a process variable (PV) filter, a Smith predictor, and a disturbance compensation (static and dynamic) using the feedforward concept. Control quality assessment is performed using PV and manipulated variables (MVs). It makes controller analysis energy-aware [33].

The HIL simulation must be put into the industrial control system design context. The design must be safe and reliable. Best practices suggest following three stages:

- Dynamic simulation of the entire control system inside the simulator, like Matlab/Simulink;

- Hardware-in-the-Loop simulation with real control hardware and a simulated process;

- Programming of the HIL validated system in target plant hardware for fine-tuning and commissioning.

As shown above, HIL simulations allow one to safely obtain the control structure and its tuning, which can be uploaded to the target system and run with high confidence. This research shows how to carry this out for a PIDA control system. It shows how the PIDA algorithm can be programmed in the real industrial system, as there is no standard block. Additional techniques such as disturbance decoupling, filtering, and the Smith predictor are also addressed. This study explains how they can work together and what they contribute. Moreover, it shows how the simulation environment can be made more accurate using tail-aware noise models. Finally, the aspect of the energy spent on control actions is highlighted.

This paper focuses on engineering aspects of PIDA implementation. Industrial applications are subject to many challenges that must be solved before successful use. This paper addresses Hardware-in-the-Loop simulations. This stage is crucial for any industrial application of a new control strategy or algorithm, as it is the best practice approach. It allows for minimizing risks before the connection of the new concept control scheme or algorithm to the real, in this case, large-scale, industrial plant.

The control system in Matlab is not the same as the control system in DCS. The description of how the HIL validation is carried out for the new control algorithm constitutes the contribution of this paper. The paper also shows how the PIDA algorithm can be programmed in a DCS. Additionally, it should be remembered that HIL experiments are not frequent in the process industry, so the propagation of this knowledge matters.

Energy as such, as well as energy awareness of the control system, is a very practical issue, though rarely addressed in the research. Showing how better control diminishes energy consumption for control actions is very practical and can only be validated in practice. This paper shows how to do it.

The narration starts with Section 2 that describes the methods and algorithms utilized. This is followed by Section 2, which describes the HIL simulation environment. The results are provided in Section 4, while the entire document is concluded in Section 5, which also identifies open issues for further analysis.

2. Methods and Algorithms

This research uses common system identification methods. The PIDA algorithm is improved to include standard blocks available in the DCS system. The PIDA control is compared with the original PID algorithm in its parallel formulation. The modifications considered include PV filtering, feedforward disturbance decoupling, and nonlinearity compensation. The analysis uses control KPIs that capture both control performance and MV energy consumption. The paragraphs below present the above methods.

2.1. Identification

The real process is identified using two methods: the frequency response and the correlation algorithm. The plant is excited with the pseudo random binary signal (PRBS) [34]. Due to its nature, the PRBS exhibits a wide bandwidth. The excitation covers a wide frequency range, which makes the identification more accurate. Once the experiment is accomplished, the data obtained are used by the frequency-based method using fast Fourier transform (FFT) together with correlation analysis [34].

The delay is separated from the dynamics. Impulse response is identified as

where denotes the plant’s response without dead time and is the pure delay; represents delay in seconds. The separation first detects the impulse time shift in the frequency domain. Fourier transform is used to identify oscillations related to dead time to make the identification less problematic. Thus, the real part of the system’s spectral transfer function is extracted in the form of

where denotes real part, its amplitude and its phase.

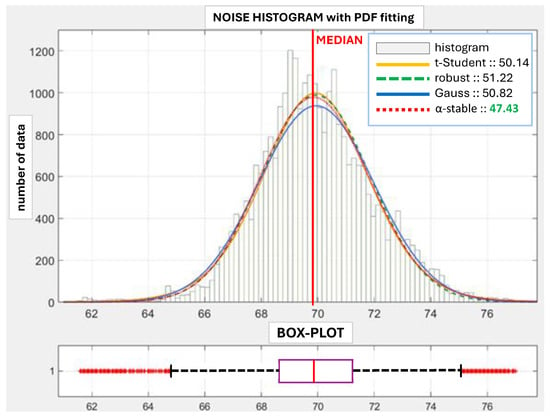

Next, the inverse fast Fourier transform (IFFT) is used to find out the dominant oscillation. The logarithm of the spectral transform is applied to improve oscillation detection. It enhances oscillations associated with . The plant is modeled as the first-order time delay (FOTD) or a higher-order time delay (HOTD) transfer function. Real process noises are independently identified to reflect industrial reality more accurately. Process noise is estimated as -stable noise [35]. The estimation uses Koutrouvelis’ regression approach [36].

2.2. Control Algorithms

Two control algorithms are addressed in this research: the PID and its extended formulation, PIDA.

2.2.1. PID

The DCS implementation of the P_PIDE block ua ses classical parallel PID structure. It is tuned using the tuning map [37] and finally fine-tuned using personal experience

2.2.2. PIDA

The first industrial PIDA controller solutions appeared in the 1980s in Honeywell’s MTS TDS system. However, due to the limited available processing power, it was abandoned. The equation for an ideal PIDA algorithm is formulated as

where denotes a controller gain, an integration time, a derivative time, and a time constant of the acceleration. In the Laplace domain, the equation takes the following form:

where N and M are time constants for differentiation and acceleration low-pass filters. Such an approach eliminates noise transfer and is necessary for good control using the PIDA algorithm. Equation (5) reduces to the ideal PID algorithm for .

The PIDA controller is developed based on the PIDE controller available in the Plant Pax library, which provides the option of selecting a speed or position algorithm. In the validation environment, the parallel speed controller option described by Equation (3) is used

where denotes the gain, an integration time in minutes, a derivative time in minutes, controller output at moment n, a control error at that moment and sampling interval (set to ).

As described earlier, the output parameters in the HIL environment are the structure of a parallel controller with separate , [s], and [s] elements. All controller settings have been recalculated accordingly. An acceleration element has been added to the controller based on an additional calculation block connected in series to the PIDE controller output.

PIDA controllers’ parametrization and tuning must be equally easy as for PIDs to make them a viable alternative. The SIMC method [9] introduces a simplified tuning of PID controllers, which is widely used in industry. The works [15,18] provide design support tools and compare PIDA controllers with classical PID controllers, highlighting the benefits of applications requiring greater precision in higher-order systems. Subsequent research [19] focuses on the design and tuning of PIDA controllers for higher-order integral processes, using advanced techniques such as IMC tuning. The most popular method is the IMC method, along with its extension to the generalized Haalman tuning method [38].

The following method is used. It begins with the identification of the process as a higher-order model obtained using the n-shift method [39]. Based on the identified higher-order process, an IMC model is constructed and reduced to a PIDA (with appropriate filters) by decomposing it into a reduced MacLaurin series [40]. Using a properly designed low-pass filter and the correct selection of IMC parameters allows for the reduction in measurement noise and the achievement of the desired control effect.

The model of the transfer function of high orders is not available in industrial practice. Thus, the applied approach uses the classical best-practice heuristic approach of optimal PID tuning, which is followed by the acceleration term and finally by the second-derivative filter.

2.3. Loop Modifications

An industrial control loop should not only address process variable performance but also must mitigate disturbances and noises or take into account nonlinearities. Thus, the control template considered should use PV filtering, disturbance decoupling with feedforward, and compensation of static nonlinearities of an actuator. Moreover, in the case of significant delays, the use of the Smith predictor should be accounted for.

2.3.1. Filtering

Industrial control is often disturbed, which demands PV filtering. Another degree of freedom occurs in the slave loop of a cascaded control, as the setpoint may also introduce noise. In that case, PV feedback filtering will not work. Control error filtering must also be used in such a situation [26]. Noise added to the measured process variable is transferred via negative feedback to the controller input. This characteristic occurs in every feedback control configuration. The CV filtering is used to counteract this phenomenon.

Advanced filtering solutions are difficult in industrial implementations, despite their positive impact on process performance. To make matters worse, they need specific and unique knowledge that is hardly available at industrial sites. A control engineer can only use blocks, which are available in a plant control system: delay, lag, static function generator, deadband (or integral deadband), saturation, or hysteresis. Actually, the filtering is mostly based on the first-order inertia term plus the function generator.

2.3.2. Feedforward

Industry constructs disturbance decoupling using additive feedforward based on the first order inertia [26] or simply by a static compensation coefficient. Many DCS systems enable direct input of a disturbance variable (DV), like a FF_VAL in Emerson DeltaV, and evaluate static compensation gain in the PID. In the case of dynamic feedforward, the DV signal enters the FF_VAL input after the series connection of the lead/lag and deadtime elements.

2.3.3. Compensation for Nonlinearities

Generally, process nonlinearity is addressed by controller gain scheduling [41]. The method assumes that though the process itself is nonlinear; one can divide the domain into a few regions, and this process may be considered linear. Thus, a specific tuning PID may be designed for each region. Controller settings are automatically switched as the process changes its operating point from one region to another. Gain-scheduling should use interpolation once, changing the region or fuzzy switching [42], to provide bumpless operation and to prevent abrupt process variations.

Once the nonlinearity occurs at the actuator’s static characteristics (the e.q. valve’s Kv curve), the inverted curve is applied using function block to compensate it [43].

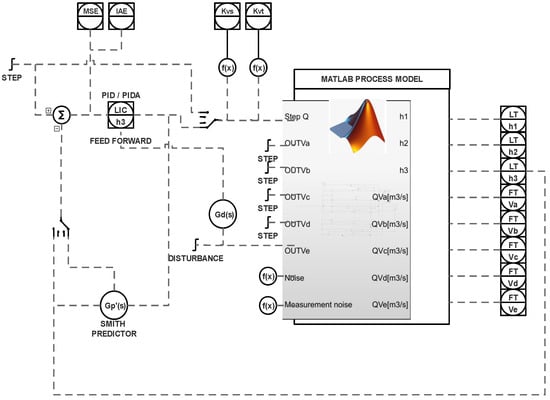

3. Simulation Environment

The simulation environment has been designed as a configuration with a long loop [7]. The real process is identified, and its model is simulated in Matlab/Simulink, while the controller is implemented in a real hardware DCS system. The model is disturbed by industrial-like noises. Modeled noise is simulated using an -stable random number generator with parameters identified during the noise identification process. More than 100 simulation experiments were run, which took more than 150 h of HIL simulations. A specific description is given below.

- Controller: PAC/DCS Allen–Bradley Control Logix L81ES (3MB BPCS memory, 1.5 MB Safety memory) and sampling equal to 1000 ms.

- Software: RS Studio 5000 Logix Designer Rockwell Software v.36.00.00.

- Communication: RS Linx Classic Single Node OPC Gateway working as an OPC DA Server/Matlab/Simulink OPC DA Client, RS Linx driver for Rockwell Software.

- Operators GUI: FT Factory View Studio v. 14.00 Rockwell Software with process libraries Plant Pax v.4.3 and internal Data Logger.

- Process model: Matlab/Simulink using Industrial Communication Toolbox.

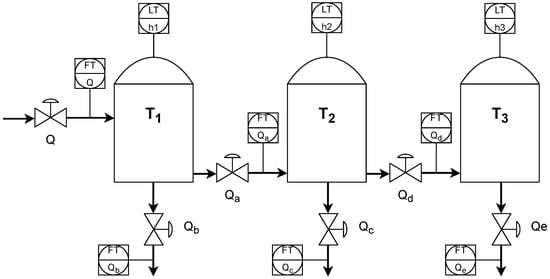

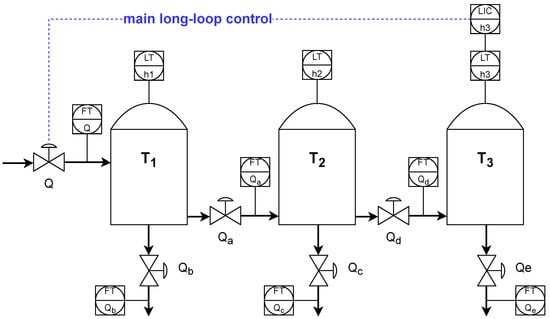

3.1. The Process

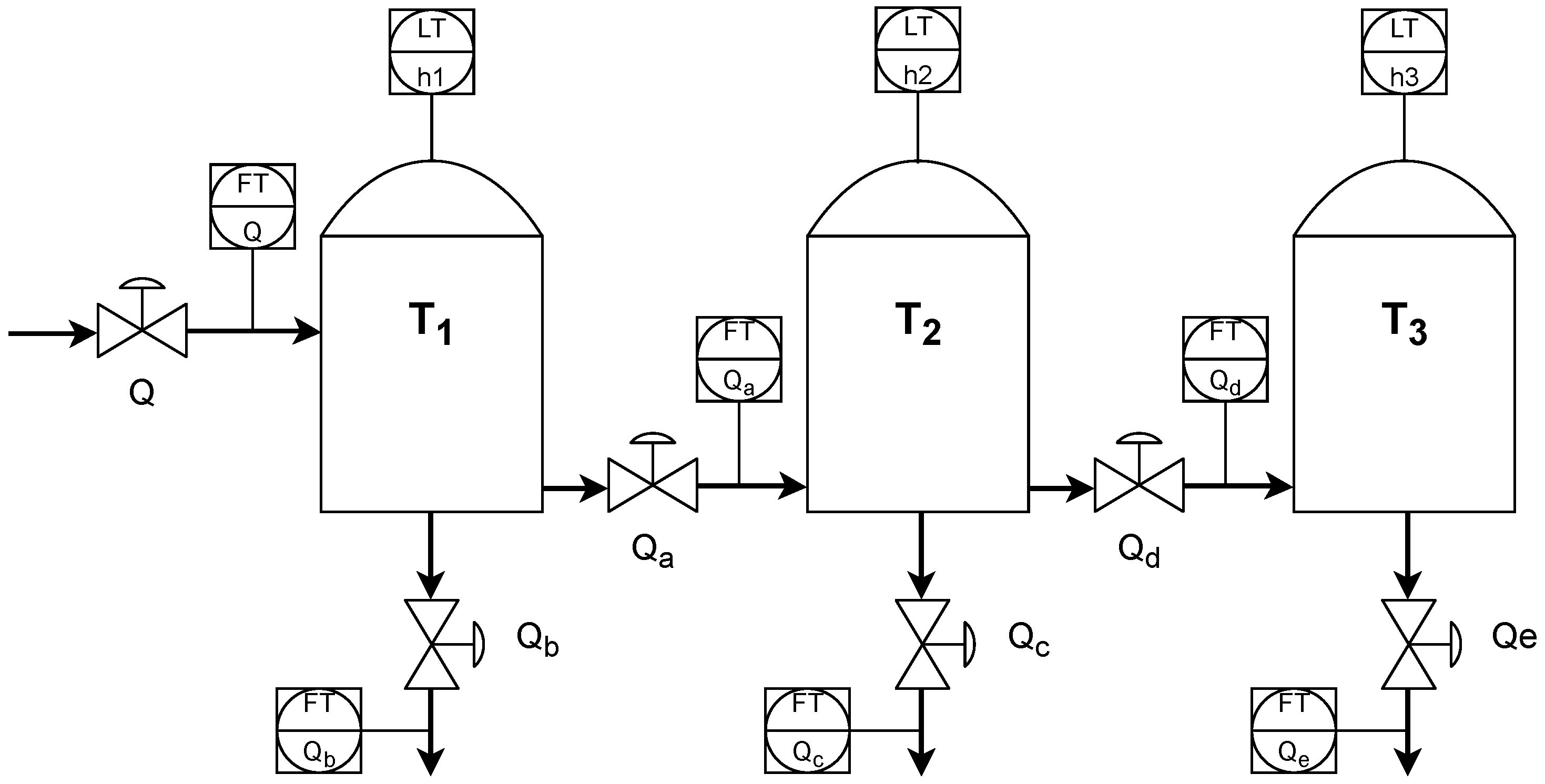

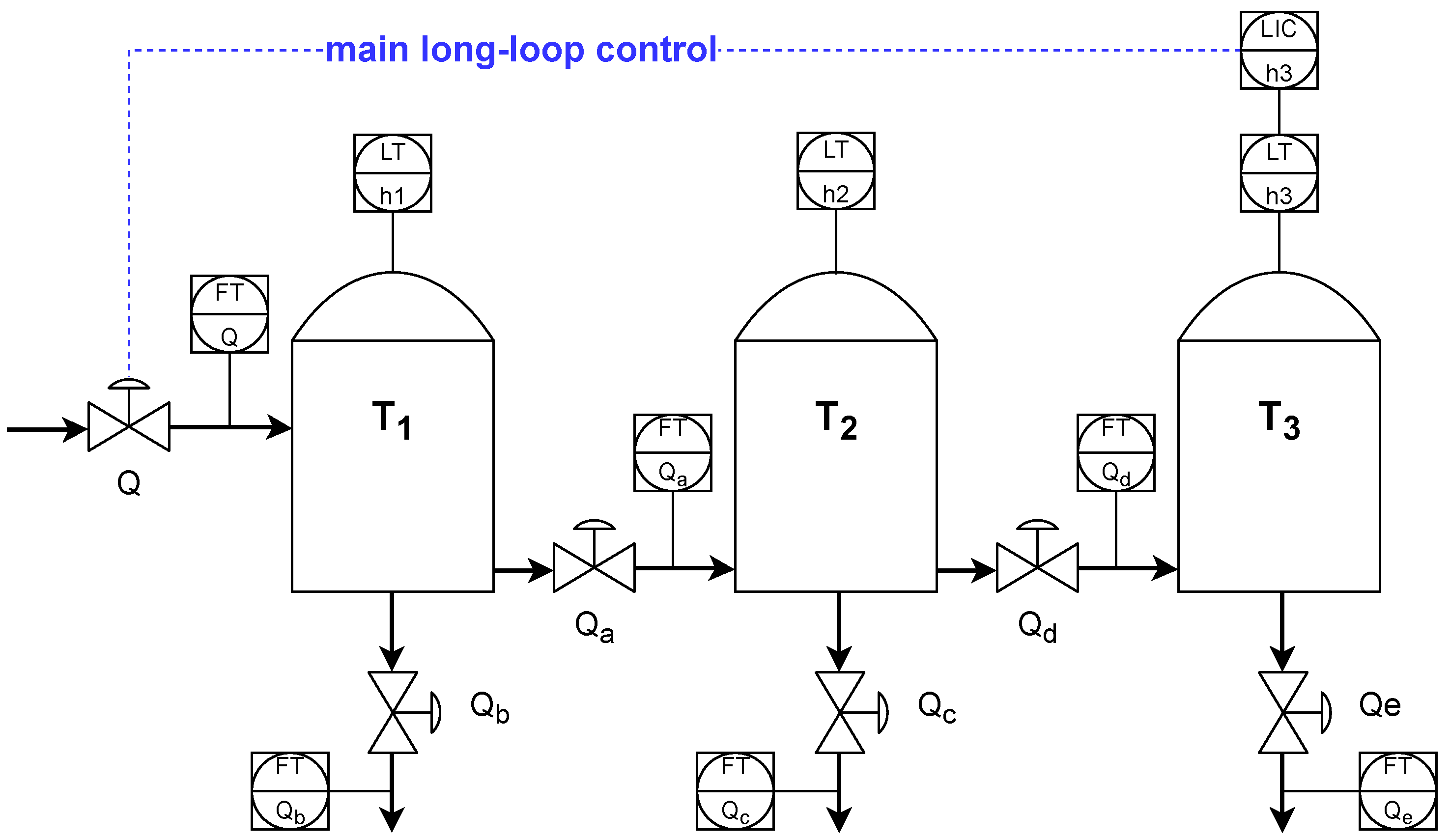

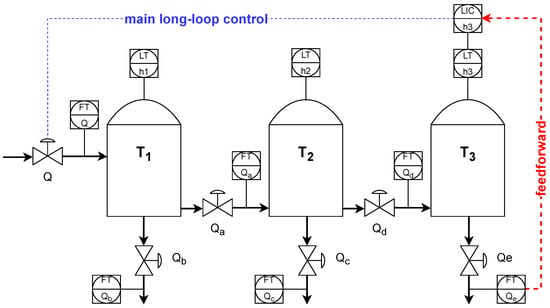

The plant consists of three vertical, pressure-less tanks, T1, T2, and T3, with radius m, height m and overflow level m. Figure 1 shows a process diagram with three tanks, piping connections, valves, a pump, and sensor placement.

Figure 1.

Three cascaded tanks—simulated plant.

A KSB centrifugal INVCP type pump rated at 30–100 m3/h feeds tank T1 using control valve Q. A minimum pumping rate of 30 m3/h once the valve Q is closed is obtained through a bypass (not shown in Matlab). The pump is not modeled, as its effect on control is negligible.

Tank T1 has two control valves: Qa at the bottom to enable liquid flow to the tank T2. Valve Qb is situated at the tank’s bottom. It supports the flow to other parts of the installation (outside the simulation scope). Tank T2 is modeled in the same way as T1. The fluid leaves T2 due to gravity. Valve Qc delivers the fluid to the non-simulated part of the process, while the valve Qd feeds tank T3. All valves (Fisher Globe and butterfly with Field Vue positioners) have a linear curve. Magnetic Flowmeter Rosemount 8705 is used as a flow sensor, and Differential Pressure Emerson 3051 Type sensors measure tank levels.

Tank T3 delivers the fluid to the final part of the installation. The level in T3 must be strictly kept inside the controlled range of m to ensure proper operation of other installation elements (outside the simulation scope). The target T3 level equals m. The following equations describe the process:

where , , denote tanks’ levels; denotes installation inflow; , , , describe outflows as shown in Figure 1; denote base area of tanks; is the fluid density; g is a gravity constant; and ’s denote valve parameters , , , and . Each flow sensor is delayed by s. Each piping connection introduces a delay due to the respective length: s, s, s, s, s.

The model takes into consideration the presence of real noises. Noises’ stochastic character in the form of the respective probabilistic density function (PDF) is identified using real plant data. It enables authentic measurement conditions to be kept. The noise is modeled using a random number generator with an -stable distribution [44]:

where

a shift, a scale, a skewness, and a stability exponent.

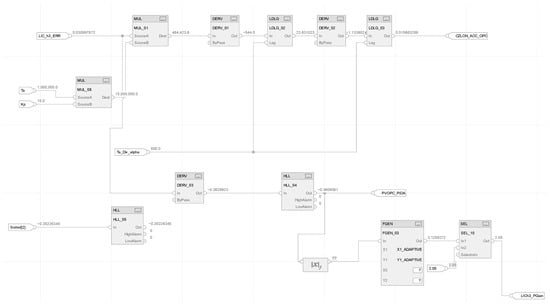

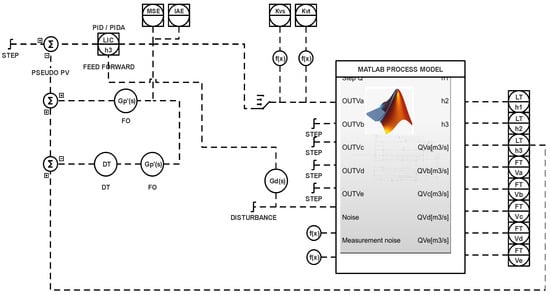

3.2. Simulink Model of the Process

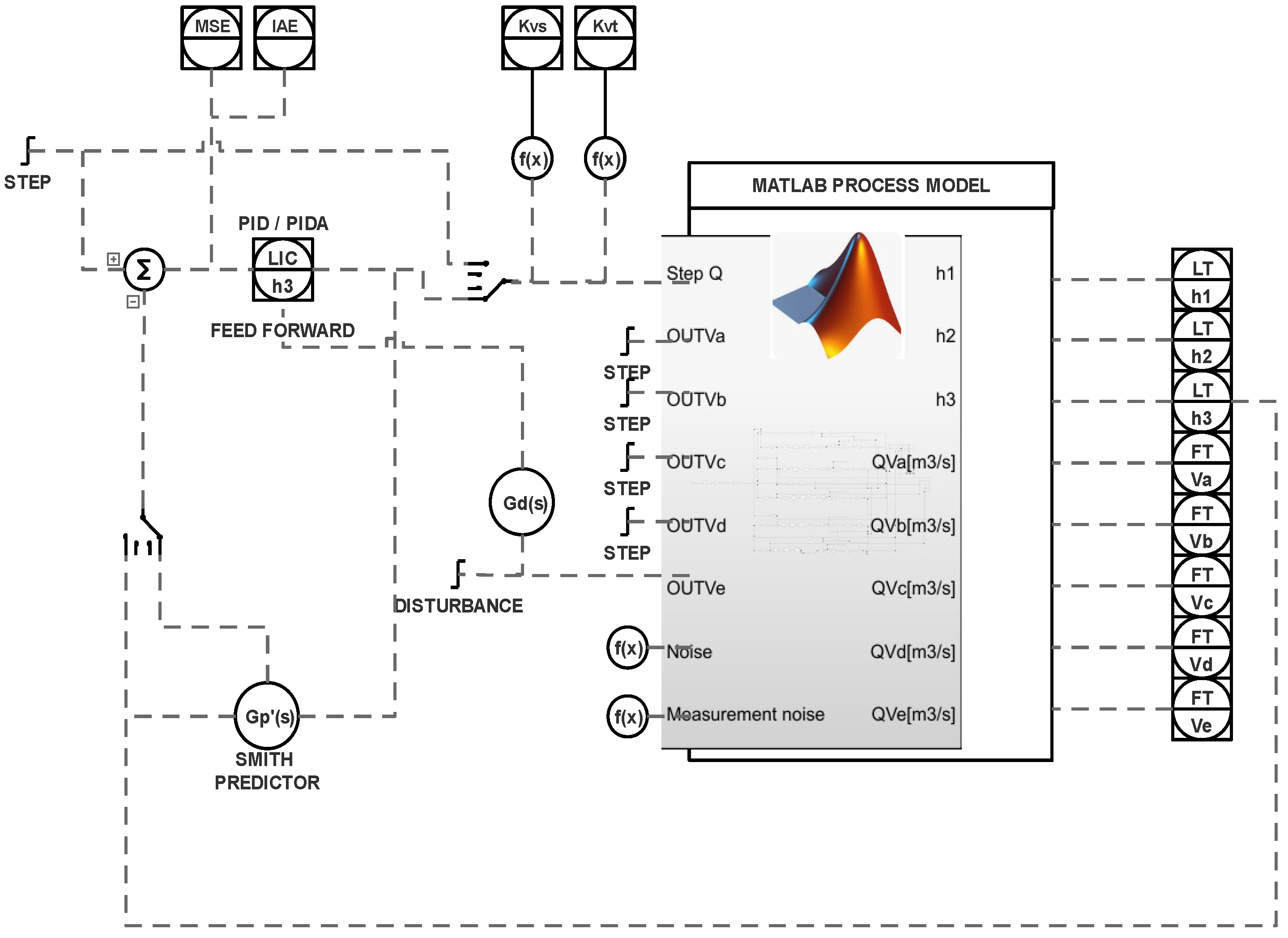

The model is constructed in a similar way in both control configurations. Based on control signals for valves () and pump load P (opening of Q valve), the model calculates the instantaneous values of the levels in each of the tanks ( in tank ; in tank ; in tank ) and flows: FTQ flow at valve Q, , which are outflows from tanks , , , and , which are flows between tanks , . The long loop version uses a Smith predictor, static, and dynamic feedforward disturbance compensation due to dead time.

The level controller in keeps the Q valve opening. The model is equipped with a noise generator designed in accordance with the noise characteristics taken from a real industrial facility. Its identified factors are , , and .

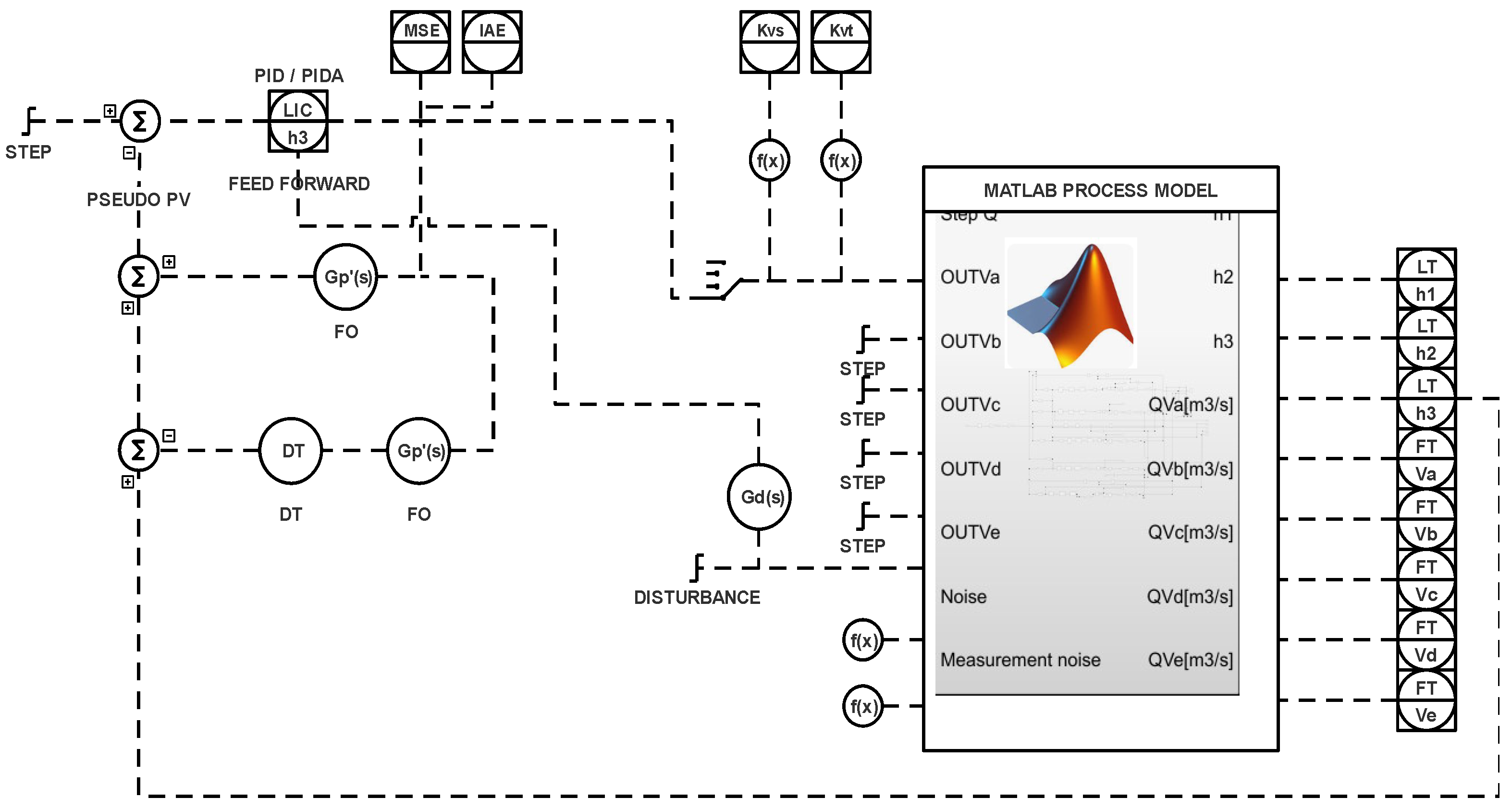

Figure 2 shows a schematic diagram of the simulation systems in Simulink with connections between the process model and hardware elements. Specific triggers allow one to switch on/off additional functionalities such as Smith predictor or feedforward disturbance decoupling. During the simulation, the respective KPIs [45] are evaluated:

Figure 2.

Matlab/Simulink process configurations for long loop control.

- Indexes MSE, MAE, rise time , settling time and an overshoot , which address loop performance.

- Valve travel and valve stroke that reflect control energy awareness.

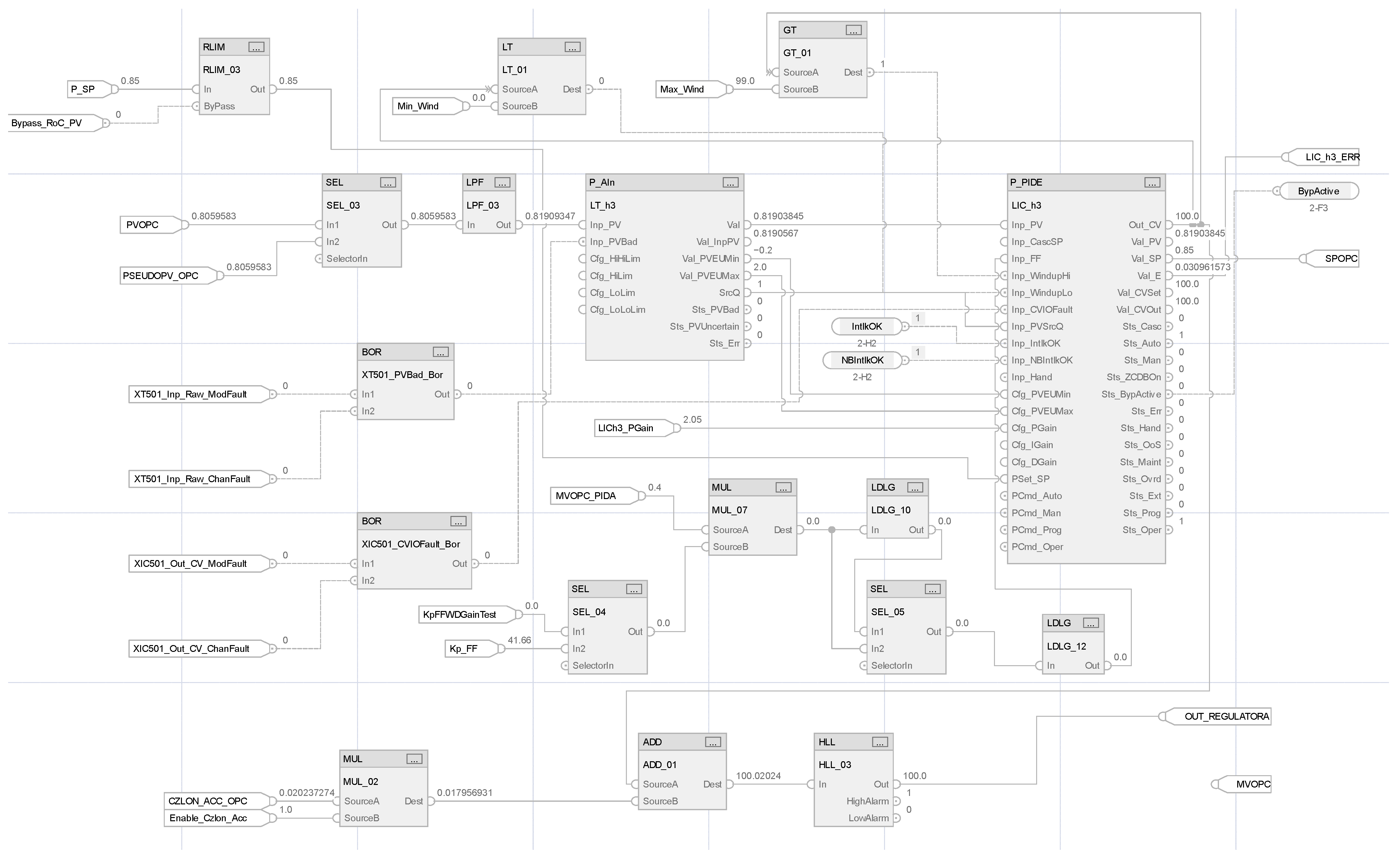

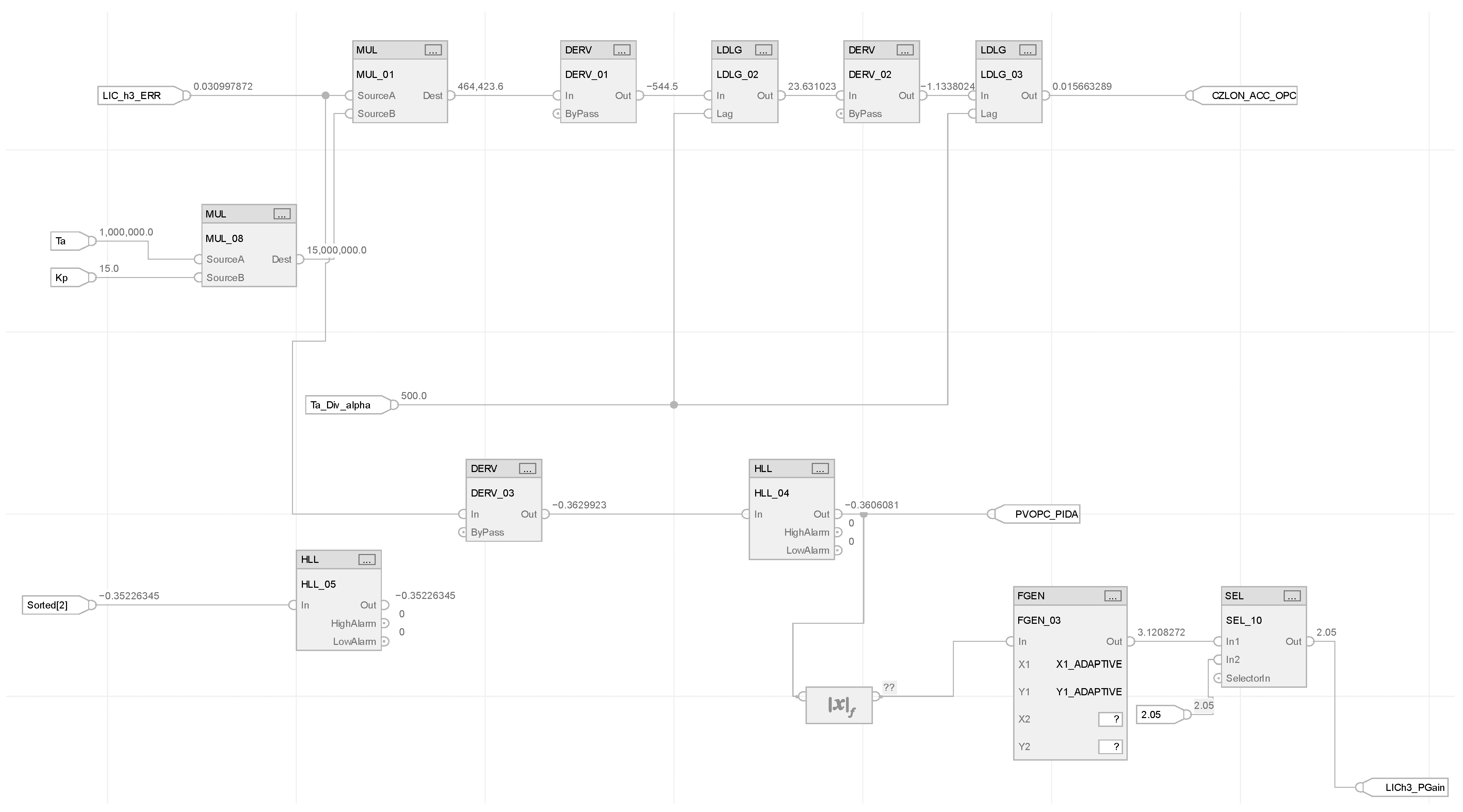

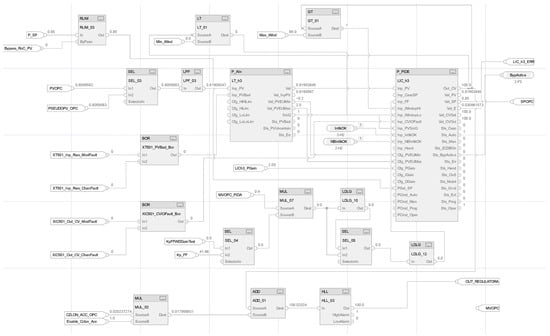

3.3. DCS-Based PIDA Controller

The PIDA controller design is implemented in the Allen–Bradley Control Studio 5000 DCS control system. The built-in PID controller (P_PIDE available for PlantPax libraries in version 4.10) is used as the reference PID algorithm [46]. The second derivative term is programmed in FBD (Function Block Diagram) using derivative function blocks and a built-in LDLG (Lead/Lag) block. Figure 3 and Figure 4 show the PIDA configuration inside the DCS with specific block-ware that allows it to run programmed simulations.

Figure 3.

RS Studio 5000 implementation: P_PIDE block, acceleration element, and saturation 0–100%.

Figure 4.

The RS Studio 5000 PIDA implementation: acceleration with gain, filter, and saturation 0–100%.

3.4. Control Schemes

Figure 5 shows a simple long loop control configuration without any additional elements.

Figure 5.

Simulated long loop control configuration.

4. Results and Discussion

The description of the experiments consists of two parts: the identification results for the real three-tank system and the PIDA control validation test.

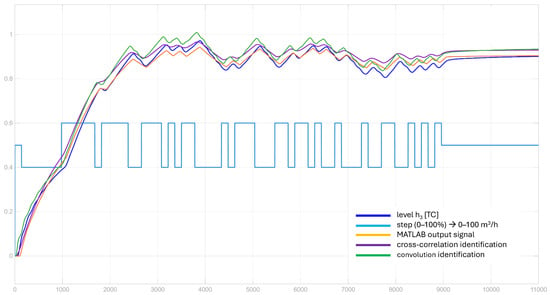

4.1. Three-Tank System Identification

A real plant consisting of three tanks is identified using two methods: frequency and correlation analysis. Actually, three transfer functions are taken into account: the T1 tank only (named T1), a series of T1 and T2 tanks (T12), and a series of all three tanks (T123). Two model structures are estimated: the FOTD transfer function (K, , ) and the higher-order one HOTD (K, , , , ). Identification results are shown in Table 1. Further PIDA design uses the HOTD transfer functions.

Table 1.

Identified transfer functions parameters.

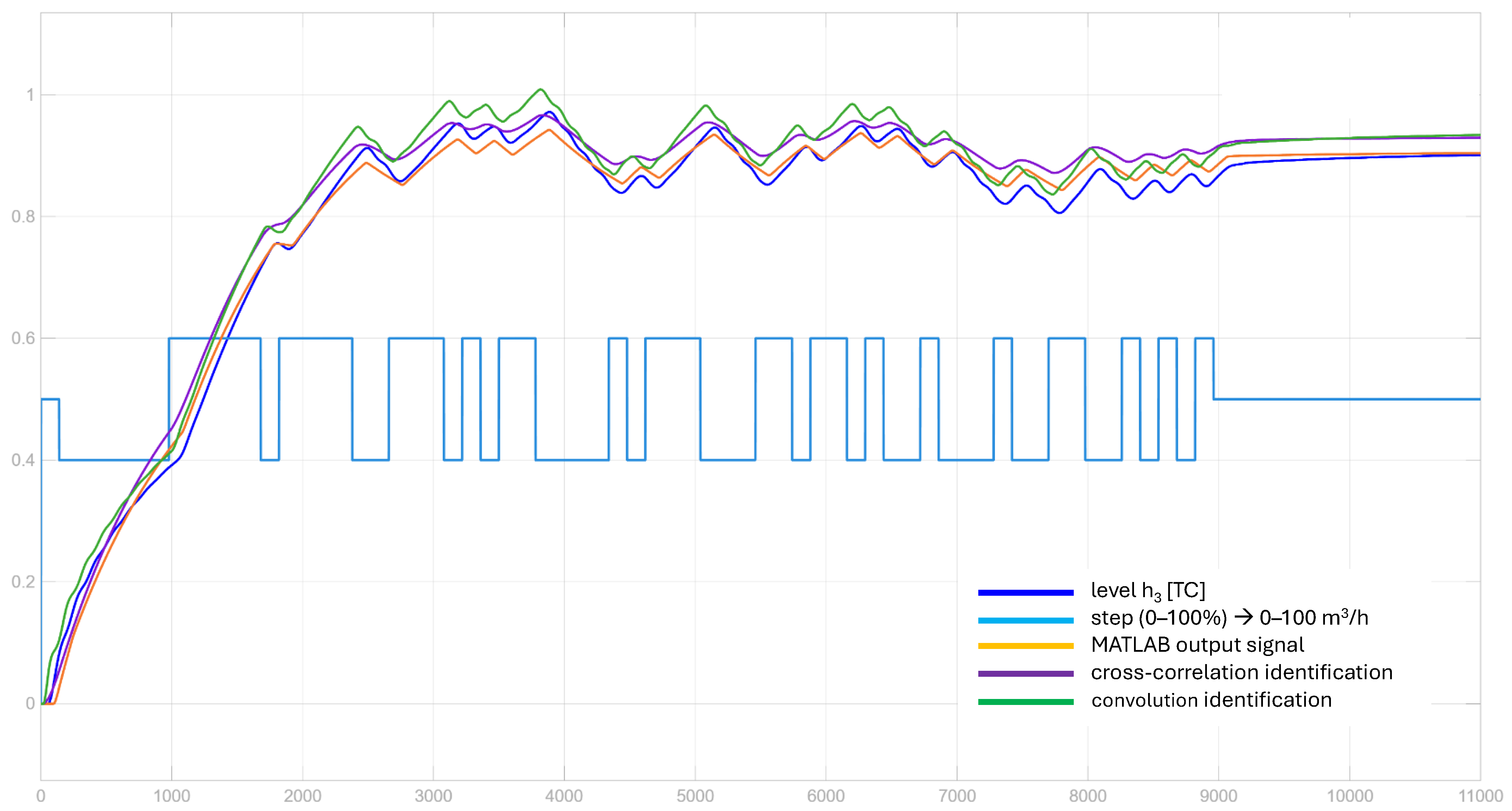

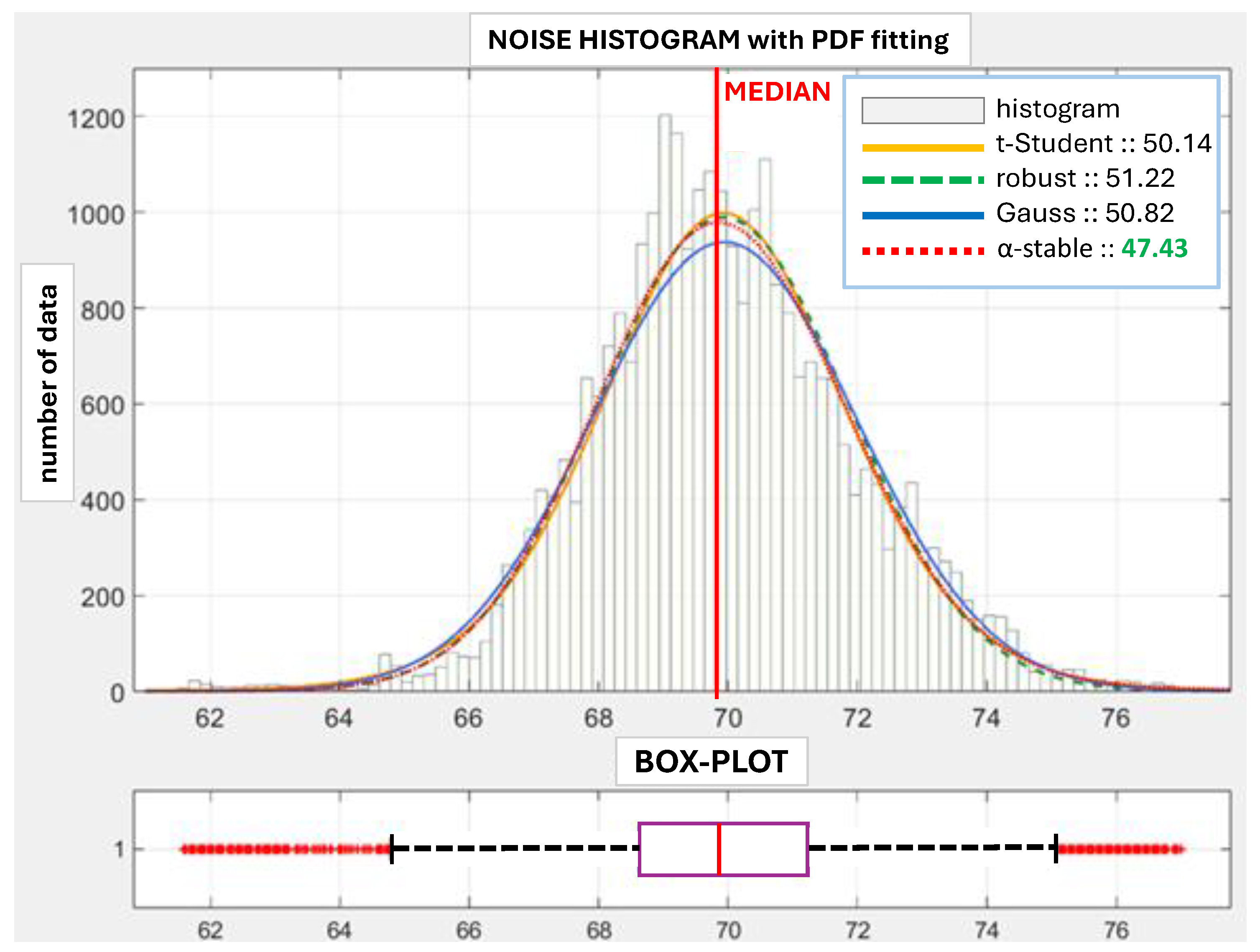

A sample PRBS identification response for all tanks in the series configuration is shown in Figure 6. It shows how the system responds to the step with an added PRBS signal. Figure 7 shows the identified noise histogram and a respective boxplot. We see that the noise is not purely Gaussian and the fitting error is minimal for the -stable distribution, which is further applied in simulations. The identified noise distribution factors of the -stable function are as follows: , , and . We observe small noise persistence because of the stability exponent .

Figure 6.

Plant identification results for T123 case.

Figure 7.

Process noise identification results.

4.2. The PIDA HIL Experiments

Initially, the reference PID controller is tuned. Its settings are obtained using the tuning map method, followed by an expert fine-tuning. The fine-tuning is performed first for the PID and next for the additional acceleration component. Tuning criteria are employed to minimize overshoot and MSE simultaneously keep a low rise time. The parameters of the validated controllers are given in Table 2.

Table 2.

Tuning parameters used during validation.

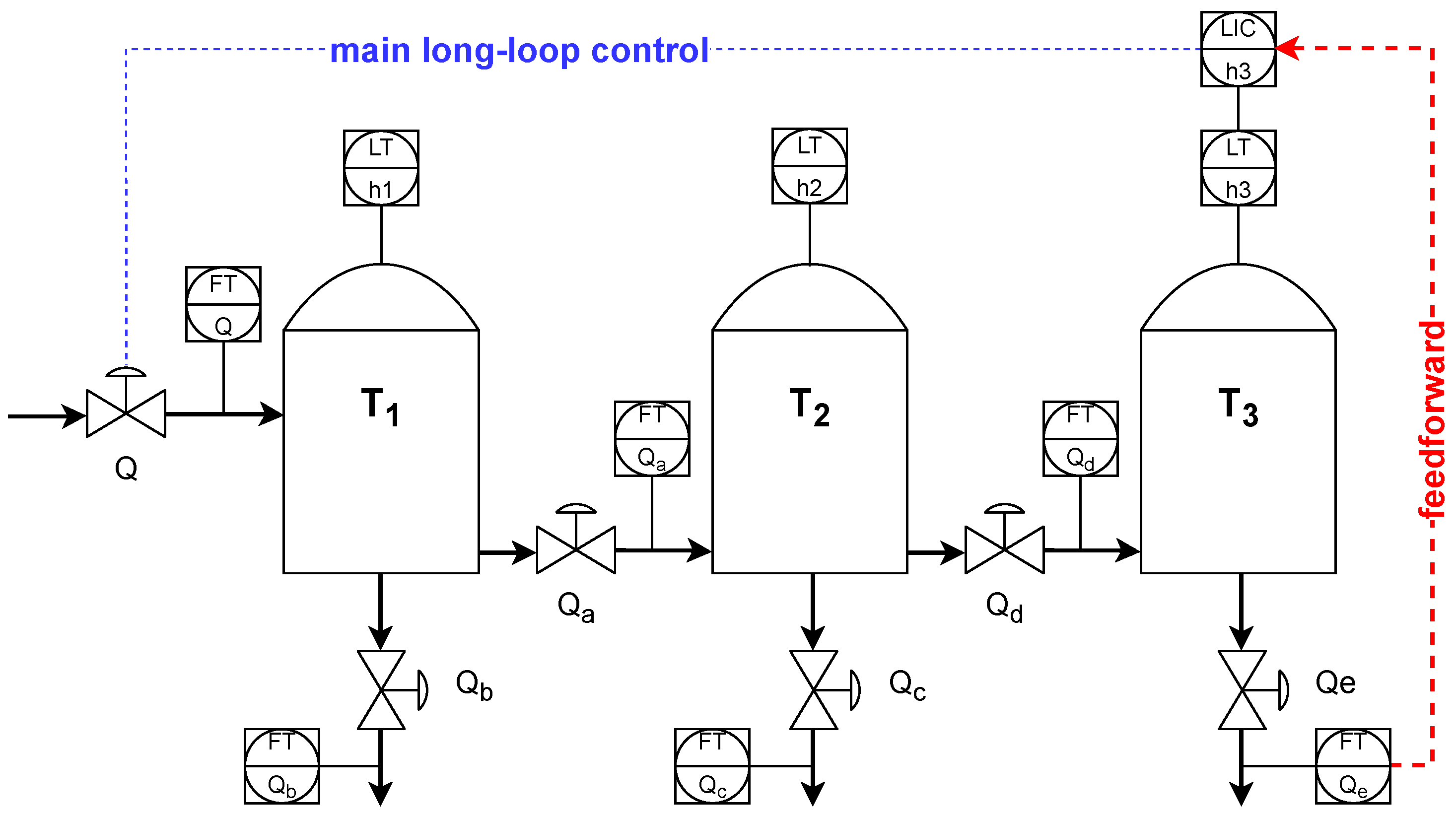

The feedforward disturbance decoupling element is tuned, which is further used in the long loop configuration. Figure 8 shows a respective control layout that incorporates the feedforward element to compensate for the outflow Qe disturbance. The identified process transfer functions allow for the design of a proper feedforward transfer function:

Figure 8.

Long loop control with feedforward disturbance decoupling.

The second required element is the filter for the process variable. The design uses a first-order Butterworth filter with a cutoff frequency of rad/s. The cutoff frequency is selected based on the calculation of the maximum possible signal frequency (above which aliasing may occur). Table 3 compares control performance with and without the filter for the reference PID control. We clearly see that it significantly decreases energy consumption by the valve reflected by the valve travel and the valve stroke indexes.

Table 3.

Filtering performance summary.

The ratio of the standard deviation for the unfiltered signal to the signal filtered with a first-order Butterworth filter equals ; for the robust Huber estimator [47] we obtain , so the filtered signal has an almost ten times smaller standard deviation. These values indicate that the first-order filter cuts off most of the noise from the signal. In addition, the rise time , settling time , and overshoot clearly indicate that the first-order filter is optimal for use in further research. The results also indicate that filtering significantly increases control system energy awareness, diminishing energy consumption to a small fraction of the original (%).

The control system is subject to comprehensive tests, including modifications and improvements discussed in the theoretical part, which allow for understanding the behavior of the control system in situations occurring in a real plant. As part of the work, over one hundred functional tests of the control system were performed, which allow us to conclude that the properties of the PIDA controller in real conditions were thoroughly investigated. All tests were conducted in real time, resulting in a total system operating time of 150 h of continuous operation. Results will form valuable input for further research.

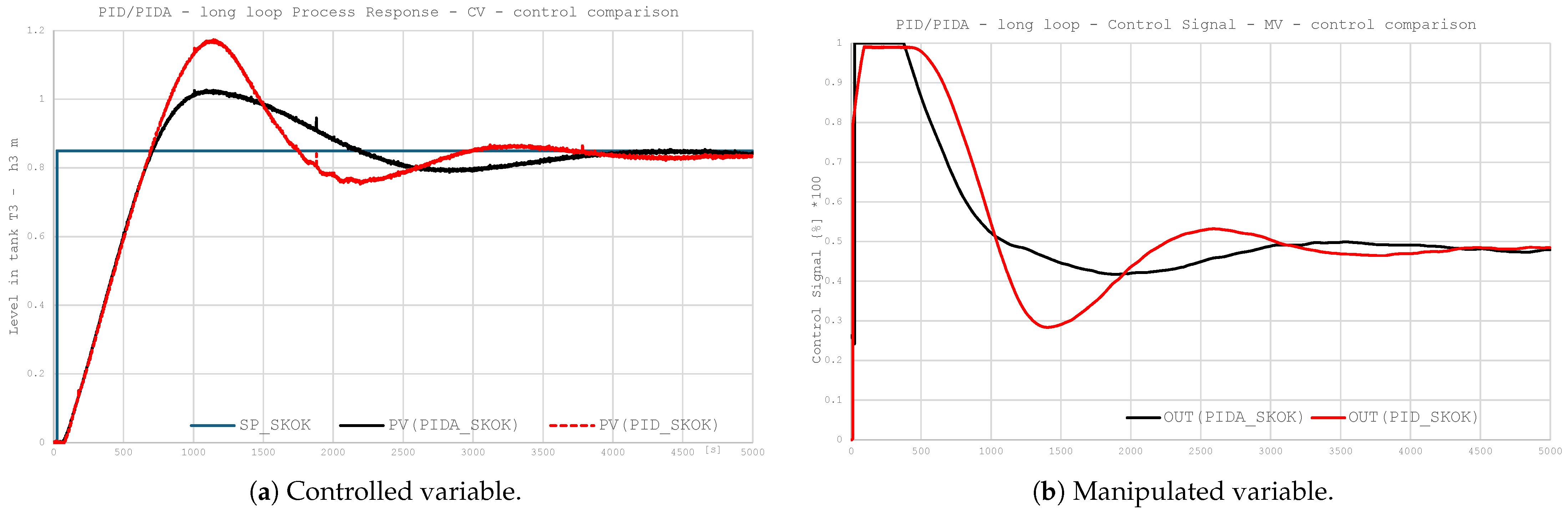

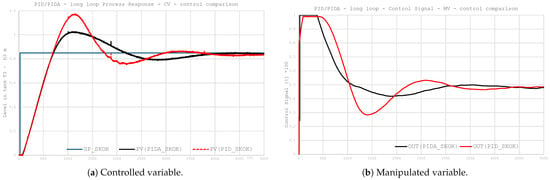

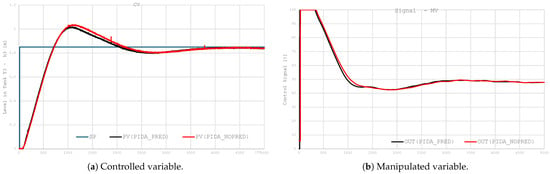

4.2.1. PID/PIDA Step Response in Long Loop

The purpose of the test is to compare the control quality between PID and PIDA controllers in a long control loop configuration implemented directly in an industrial controller. The controllers have identical parameters , , , and the PIDA controller has a pre-tuned acceleration element and an associated filter. The tested control systems do not use the Smith predictor. The test system contains plant noise being filtered.

The MSE and MAE are calculated for two cases. The MSE5000 and MAE5000 cover the entire test response, while the MSE500–5000 and MAE500–5000 cover only the period from the measured value reaching approximately 63% of the single step value (500 s). Assessment includes step response indexes and energy awareness indexes of valve travel and valve stroke. Table 4 summarizes the control quality coefficients, while Figure 9 compares response curves of process variable and controller output. The observations are as follows:

Table 4.

Results for step response in a long loop.

Figure 9.

Step response in a long loop.

- PIDA allows for more effective suppression of oscillations in the closed-loop response.

- The use of derivative filtering and an additional second-order differentiating element allows for better representation of the plant’s characteristics, thereby limiting excessive transient responses.

- The settling time for the PIDA controller is significantly shorter, which results from faster suppression of the dynamic error component and earlier entry of the system into a near-steady state.

- The reduction in MSE/MAE indicators means not only better control quality, but also potentially lower energy consumption and less use of actuators.

- The control signal response for PIDA is characterized by lower amplitude and smoother changes, which can have a positive effect on the durability of actuators and the stability of systems with nonlinearities. Unlike PID, it does not generate overly aggressive responses to momentary errors.

- The use of the PIDA structure provides measurable benefits in terms of dynamics, accuracy, disturbance rejection, and controller energy awareness.

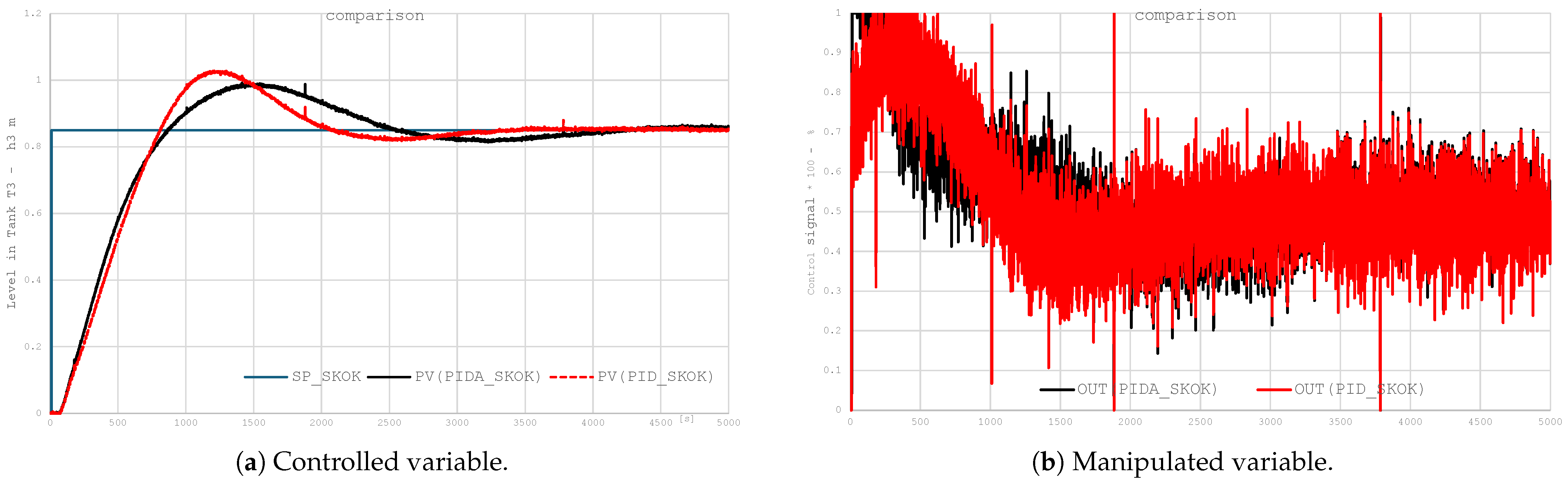

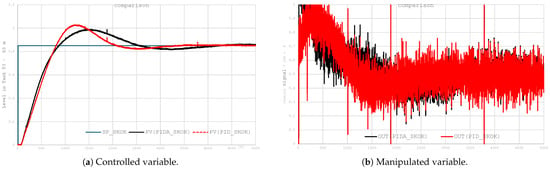

4.2.2. PID/PIDA Step Response in Long Loop with PV Filtering Disabled

The purpose of the test is to compare the control quality between PID/PIDA controllers in a long control loop configuration; however, the PV filtering is excluded from the test. The test aims to understand the impact of measurement value filtering on control quality and on the wear and tear of actuators, e.g., actuators and control valve positioners.

In industrial practice, measurement value filtering is an important element in improving control quality. However, selecting the optimal time constant for a low-pass filter involves an inevitable compromise between the response speed of the control system and the level and dynamics of the control signal. Excessive filtration may delay the response, while insufficient filtration can lead to increased interference and undesirable overmodulation of the output signal. Table 5 summarizes the control quality coefficients, while Figure 10 show a comparison of the response curves of the process variable and the controller output.

Table 5.

Results for step response in a long loop without filtering.

Figure 10.

Step response in a long loop without filtering.

The observations are as follows:

- The lack of MV filtering results in increased noise in the system response and control signal. This is particularly evident in the PID path, where the lack of interference suppression leads to high-frequency changes and more aggressive control.

- A clear deterioration in the quality of the control signal is observed in both structures. In particular, the signal for the PID shows a significant amplitude of interference, which can lead to undesirable effects in actual actuators and increased energy costs.

- Despite identical controller settings, PIDA maintains better control quality: it exhibits less overshoot and a smoother approach to the setpoint. This demonstrates the greater resistance of the PIDA structure to disturbances in the measurement path.

- It is worth noting that despite the lack of filtration, PIDA maintains higher controllability, suggesting that its extended internal dynamics compensate to some extent for the lack of external filtration.

- The lack of disturbance suppression leads to the generation of dynamically unacceptable control signal excitation, which in real actuator systems results in excessive energy consumption and unnecessary wear or even damage to actuators.

- The PIDA controller, despite the lack of PV filtering, shows greater resistance to measurement disturbances.

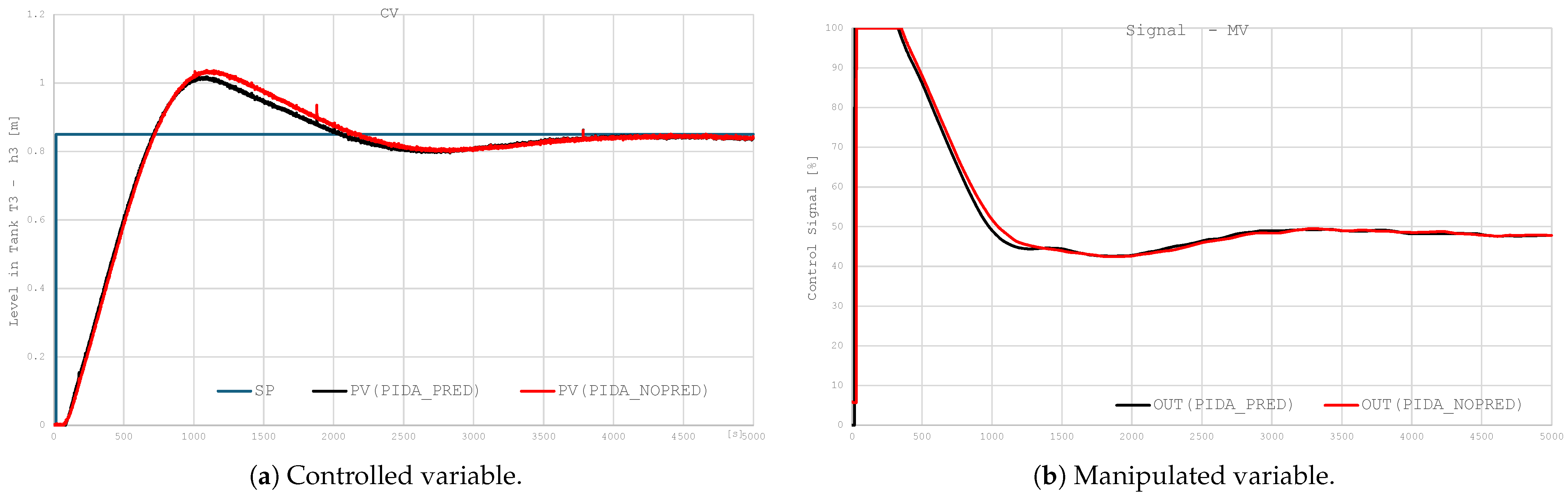

4.2.3. PIDA Control with Smith Predictor

The test aims at the evaluation of the Smith predictor impact. As the theoretical aspects of the Smith predictor are not the main goal of this research, the model accuracy is not addressed. However, it is important that the embedded model must be accurate, as its poor estimation may degrade the overall performance, especially in case of dead time estimation errors [48]. The comparison is performed for a PIDA controller with and without a Smith predictor. The tested control systems have a controller with identical dynamic element settings. A schematic diagram of the controller is shown in Figure 11.

Figure 11.

Smith predictor DCS configuration.

Table 6 summarizes performance coefficients, while Figure 12 compares response curves for process variable and controller output. The observations are as follows:

Table 6.

Impact of the Smith predictor on long loop operation.

Figure 12.

Effect of the Smith predictor on long loop operation.

- The consistency of the first-order model response with the actual PV signal indicates high accuracy of the object dynamics mapping by the model used in the Smith predictor. Such accuracy is a prerequisite for the effective operation of the delay compensation.

- The use of prediction in the PIDA structure (PRED variant) results in a reduction in the settling time of the closed-loop system.

- The reduction in overshoot observed in the PRED response results from the limitation of the phase delay effect in the control loop.

- A comparison of MVs for the PRED and NOPRED variants shows no significant differences in the nature of the controller’s operation (no oscillations), which proves that the introduction of prediction does not destabilize the control path and maintains similar energy awareness.

- The results obtained confirm the effectiveness of implementing the Smith predictor in the PIDA controller for processes with dominant delay.

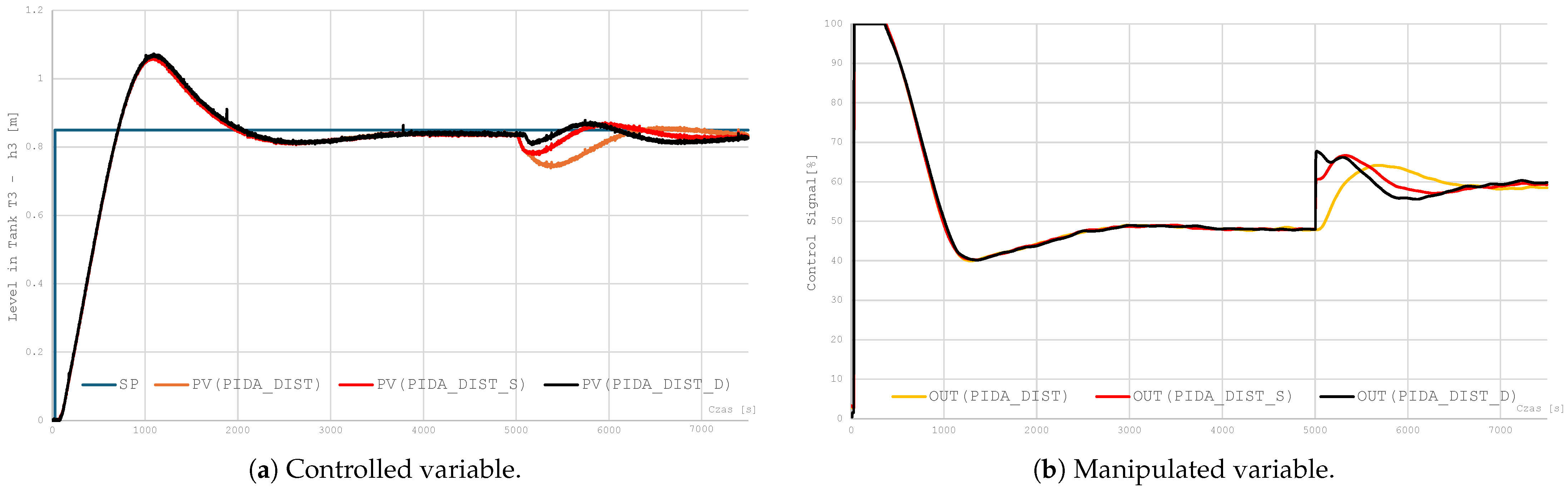

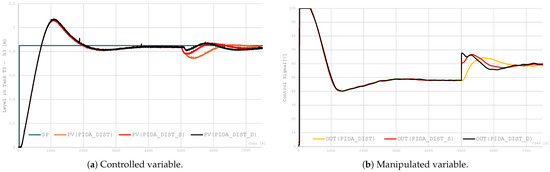

4.2.4. The Impact of Process Disturbance on PIDA Control

The aim of the study is to understand the impact of disturbance on the PIDA’s operation and to eliminate process disturbance by abruptly increasing the opening of the outlet valve from tank T3. The disturbance caused by an increase in demand for the product from tank T3 is technologically justified in the process. The software implementation in the industrial controller is carried out as static (PID DIST_S) and dynamic compensation (PID DIST_D) using the available Lead/Lag block and Dead Time block. The values Lead = 1066 s and Lag = 900 s are entered for the valve opening signal multiplied by the Feedforward gain KFFWD = 0.416. The disturbance signal occurs at 5000 s of simulation.

Table 7 summarizes the control quality coefficients, while Figure 13 shows a comparison of the response curves of the process variable and the controller output. We see that the control system is unable to completely eliminate the impact of the disturbance. This is due to the fact that the dead time between the disturbance and the process variable is shorter than the dead process time itself. Therefore, the system is unable to adequately compensate for disturbances that have not yet occurred. General observations are as follows.

Table 7.

Impact of the disturbance on long loop operation.

Figure 13.

Effect of the Smith predictor on long loop operation.

- The use of dynamic compensation with the Lead/Lag and Dead Time blocks leads to a significant improvement in control quality.

- Static compensation (PIDA_DIST_S) reduces the effects of disturbance only to a limited extent.

- The lack of compensation (PIDA_DIST) causes the system to exhibit the highest control error and the greatest instability of the control signal after a disturbance occurs, which confirms the need to use feedforward mechanisms.

- An improvement in the energy awareness of the MV signal can also be seen after the use of feedforward decoupling.

4.3. Concluding Remarks

The proposed and evaluated HIL simulation environment constitutes a crucial step during the implementation of any novel control approach. Best practices for safe control system design suggest the following three stages:

- Simulation of the entire loop (control system) inside the dynamic simulator, like Matlab/Simulink, for example;

- Hardware-in-the-Loop simulation with real control hardware and simulated process (sometimes called FAT—Factory Acceptance Test);

- Programming of the control system evaluated in the HIL into the target plant control system for final tuning and commissioning (often called SAT—Site Acceptance Test).

This research shows how such FAT testing can be performed. Moreover, it should be noted that the presented approach incorporates process noise modeling into the procedure for a reflection of reality that is as real as possible. The noise model uses a fat-tailed approach with -stable noise, which significantly makes the simulation closer to the industrial reality.

Such an approach allows for mitigating the risk associated with the site implementation, but it still relies on a sufficiently good simulated model and requires access to additional hardware equipment.

5. Conclusions and Further Research

The aim of this research is to compare the quality of control achieved by a classical PID and its extended PIDA version for a system with large inertia and long delays. Secondly, the HIL simulation is considered as a crucial step in industrial control system design.

The PIDA controller, by introducing an acceleration term (a second derivative of control error), enables active shaping of the closed-loop system’s transfer function by generating additional transfer function zeros, which translates into increased phase margin, reduced oscillations, and improved damping of the object’s dynamics. An analysis of the results shows the superiority of the PIDA controller over the classic PID controller. The PIDA controller allows us to achieve lower overshoot values and a smoother approach to the setpoint, i.e., with shorter rise times and minimized oscillations. However, the introduction of an acceleration term requires the use of advanced signal filtering, which mitigates actuators’ energy consumption and makes the design process energy-aware.

The complex structure of the PIDA controller significantly increases the number of parameters requiring tuning: in addition to the standard dynamic parameters of the PID controller , , and , it is also necessary to select the gain of the acceleration term , differential filtering constant , and parameters of the PV filters. The implementation of the PIDA controller in the DCS system is carried out exclusively on the basis of standard function blocks available in the software, which significantly facilitates its programming and at the same time reduces the risk of implementation errors. The algorithm is expanded with additional differentiation and filtering maintaining readability of the control code.

The overall results clearly confirm the effectiveness of the PIDA controller as a control tool for plants with complex dynamics and processes sensitive to overshoot. The work highlights the active influence of PIDA control on the shaping of control signals, reducing energy consumption for control-related actions and the wear and tear of actuators.

The research also shows that HIL simulations can be effectively used as a testing platform to evaluate new control techniques, shortening the design time and making the whole implementation process safer and more reliable.

One of the key directions for further research is the development of standardized methods for PIDA controller auto-tuning, taking into account the multidimensional characteristics of the parameter space and controller energy awareness. The introduction of such methods would allow for a wider use of the PIDA controller in industrial applications, where the complex tuning task requiring expert knowledge remains a limitation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.J. and P.D.D.; methodology, M.J.; software, M.J.; validation, M.J.; formal analysis, M.J.; investigation, M.J.; data curation, M.J.; writing—original draft preparation, P.D.D.; writing—review and editing, M.J. and P.D.D.; supervision, P.D.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Marcin Jabłoński was employed by the company QEMETICA Soda Polska S.A. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| PID | Proportional-Integral-Derivative |

| PIDA | Proportional-Integral-Derivative-Acceleration |

| IMC | Internal Model Control |

| SIMC | Skogestad Internal Model Control |

| SISO | Single Input Single Output |

| CPA | Control Performance Assessment |

| KPI | Key Performance Indicator |

| QMV | Quadratic Manipulated Variable |

| HIL | Hardware-in-the-Loop |

| PLC | Programmable Logic Controller |

| DCS | Distributed control System |

| PV | Process Variable |

| MV | Manipulated Variable |

| DV | Disturbance Variable |

| PRBS | Pseudo Random Binary Signal |

| FFT | Fast Fourier Transform |

| IFFT | Inverse Fast Fourier Transform |

| FOTD | First Order Time Delay |

| HOTD | Higher Order Time Delay |

| Probability Density Function | |

| MSE | Mean Square Error |

| MAE | Mean Absolute Error |

| FBD | Function Block Diagram |

| FAT | Factory Acceptance Test |

| SAT | Site Acceptance Test |

References

- Åström, K.J.; Murray, R. Feedback Systems: An Introduction for Scientists and Engineers; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA; Oxford, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Samad, T. A Survey on Industry Impact and Challenges Thereof [Technical Activities]. IEEE Control Syst. Mag. 2017, 37, 17–18. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, L.; Li, D.; Lee, K.Y. Optimal disturbance rejection for PI controller with constraints on relative delay margin. ISA Trans. 2016, 63, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domański, P.D. Performance Assessment of Predictive Control—A Survey. Algorithms 2020, 13, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bialkowski, W.L. Dreams versus reality: A view from both sides of the gap: Manufacturing excellence with come only through engineering excellence. Pulp Pap. Can. 1993, 94, 19–27. [Google Scholar]

- Ordys, A.; Uduehi, D.; Johnson, M.A. Process Control Performance Assessment—From Theory to Implementation; Springer: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Skogestad, S. Advanced control using decomposition and simple elements. Annu. Rev. Control 2023, 56, 100903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziegler, J.G.; Nichols, N.B. Optimum Settings for Automatic Controllers. Trans. Am. Soc. Mech. Eng. 1942, 64, 759–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skogestad, S.; Grimholt, C. The SIMC Method for Smooth PID Controller Tuning. In PID Control in the Third Millennium; Vilanova, R., Visioli, A., Eds.; Springer: London, UK, 2012; pp. 147–175. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, S.; Dorf, R. Analytic PIDA controller design technique for a third order system. In Proceedings of the 35th IEEE Conference on Decision and Control, Kobe, Japan, 13 December 1996; Volume 3, pp. 2513–2518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huba, M.; Bistak, P.; Vrancic, D. Series PIDA Controller Design for IPDT Processes. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 2040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huba, M.; Bistak, P.; Vrancic, D. Parametrization and Optimal Tuning of Constrained Series PIDA Controller for IPDT Models. Mathematics 2023, 11, 4229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Hote, Y.V. Robust CDA-PIDA Control Scheme for Load Frequency Control of Interconnected Power Systems. In Proceedings of the 3rd IFAC Conference on Advances in Proportional-Integral-Derivative Control PID, Ghent, Belgium, 9–11 May 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jitwang, T.; Hlangnamthip, S.; Puangdownreong, D. Robust PIDA Controller Design by Cuckoo Search for Liquid-Level Control System. In Proceedings of the 2020 Joint International Conference on Digital Arts, Media and Technology with ECTI Northern Section Conference on Electrical, Electronics, Computer and Telecommunications Engineering (ECTI DAMT & NCON), Pattaya, Thailand, 11–14 March 2020; pp. 226–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, M.; Visioli, A. A software tool to understand the design of PIDA controllers. In Proceedings of the 13th IFAC Symposium on Advances in Control Education ACE 2022, Hamburg, Germany, 24–27 July 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milanesi, M.; Mirandola, E.; Visioli, A. A comparison between PID and PIDA controllers. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 27th International Conference on Emerging Technologies and Factory Automation (ETFA), Stuttgart, Germany, 6–9 September 2022; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milanesi, M.; Visioli, A.; Chen, Y. Performance comparison between PID, PIDD2 and PIDD2α. In Proceedings of the 12th IFAC Conference on Fractional Differentiation and its Applications ICFDA 2024, Bordeaux, France, 9–12 July 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visioli, A.; Sánchez-Moreno, J. Design of PIDA Controllers for High-order Integral Processes. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 28th International Conference on Emerging Technologies and Factory Automation (ETFA), Sinaia, Romania, 12–15 September 2023; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visioli, A.; Sánchez-Moreno, J. IMC-based tuning of PIDA controllers: A comparison with PID control. In Proceedings of the 4th IFAC Conference on Advances in Proportional-Integral-Derivate Control PID 2024, Almería, Spain, 12–14 June 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Žáková, K.; Matišák, J.; Šefčík, J. Contribution to PID and PIDA Interactive Educational Tools. In Proceedings of the 4th IFAC Conference on Advances in Proportional-Integral-Derivate Control PID 2024, Almería, Spain, 12–14 June 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milanesi, M.; Paolino, N.; Schiavo, M.; Padula, F.; Visioli, A. PIDA control of depth of hypnosis in total intravenous anesthesia. In Proceedings of the 4th IFAC Conference on Advances in Proportional-Integral-Derivate Control PID 2024, Almería, Spain, 12–14 June 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, Z.; Li, Y.; Williams, K. HVAC control loop performance assessment: A critical review (1587-RP). Sci. Technol. Built Environ. 2017, 23, 619–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberati, F.; Cirino, C.M.F.; Tortorelli, A. Energy-Aware Model Predictive Control of Assembly Lines. Actuators 2022, 11, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arabas, P.; Sikora, A.; Szynkiewicz, W. Energy-Aware Activity Control for Wireless Sensing Infrastructure Using Periodic Communication and Mixed-Integer Programming. Energies 2021, 14, 4828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krok, M.; Majewski, P.; Hunek, W.P.; Feliks, T. Energy Optimization of the Continuous-Time Perfect Control Algorithm. Energies 2022, 15, 1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domański, P.D. Improving Actuator Wearing Using Noise Filtering. Sensors 2022, 22, 8910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grobelna, I. Intelligent Industrial Process Control Systems. Sensors 2023, 23, 6838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K. Development of Hardware-in-the-Loop Simulation Test Bed to Verify and Validate Power Management System for LNG Carriers. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwakin, O.; Moazeni, F. Hardware-in-the-Loop Simulation of Data-Driven Economic Dispatch Problem for Integrated Water-Energy Systems. In World Environmental and Water Resources Congress 2025; American Society of Civil Engineers: Reston, VA, USA, 2025; pp. 886–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thönnessen, D. Hardware-in-the-Loop Testing of Industrial Automation Systems Using PLC Languages; Technical Report AIB-2021-10; Department of Computer Science, RWTH Aachen University: Aachen, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Nam, K.; Kwon, K.; Kim, A. HINT-Sec: Hardware-in-the-Loop nuclear power plant testbed for cyber security. Prog. Nucl. Energy 2025, 180, 105600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelm, P.; Wasiak, I.; Mieński, R.; Wędzik, A.; Szypowski, M.; Pawełek, R.; Szaniawski, K. Hardware-in-the-Loop Validation of an Energy Management System for LV Distribution Networks with Renewable Energy Sources. Energies 2022, 15, 2561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domański, P.D. Energy-Aware Multicriteria Control Performance Assessment. Energies 2024, 17, 1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isermann, R.; Münchhof, M. Identification of Dynamical Systems; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Domański, P.D. Back to Statistics. Tail-Aware Control Performance Assessment; CRC Press, Taylor & Francis Group: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Koutrouvelis, I.A. Regression-Type Estimation of the Parameters of Stable Laws. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1980, 75, 918–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Åström, K.; Hägglund, T. PID Controllers: Theory, Design, and Tuning; ISA—The Instrumentation, Systems and Automation Society: Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Campregher, F.; Milanesi, M.; Schiavo, M.; Visioli, A. Generalized Haalman tuning of PIDA controllers. In Proceedings of the 4th IFAC Conference on Advances in Proportional-Integral-Derivate Control PID 2024, Almería, Spain, 12–14 June 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofreiter, M. Shifting Method for Relay Feedback Identification. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2016, 49, 1933–1938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Park, S.; Lee, M.; Brosilow, C. PID controller tuning for desired closed-loop responses for SI/SO systems. AIChE J. 1998, 44, 106–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rugh, W.J.; Shamma, J.S. Research on gain scheduling. Automatica 2000, 36, 1401–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domański, P.D.; Brdyś, M.; Tatjewski, P. Design and Stability of Fuzzy Logic Multi-Regional Output Controllers. Int. J. Appl. Math. Comput. Sci. 1999, 9, 883–897. [Google Scholar]

- Halimi, B.; Suh, K. Analysis of nonlinearities compensation for control valves. In Proceedings of the 2010 International Congress on Advances in Nuclear Power Plants-ICAPP’10, San Diego, CA, USA, 13–17 June 2010; Volume 3, pp. 1626–1629. [Google Scholar]

- Nolan, J.P. Stable Regression. In Univariate Stable Distributions: Models for Heavy Tailed Data; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Swizterland, 2020; pp. 223–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domański, P.D. Control Performance Assessment: Theoretical Analyses and Industrial Practice; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Swizterland, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rockwell. Logix 5000 Advanced Process Control and Drives Instruction; Publication 1756-RM006P-EN-P; Rockwell Automation, Inc.: Milwaukee, WI, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Huber, P.J.; Ronchetti, E.M. Robust Statistics, 2nd ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Veronesi, M. Performance Improvement Of Smith Predictor Through Automatic Computation Of Dead Time; Technical Report 35; Yokogawa Technical Report English Edition; Yokogawa: Nova Milanese, Italy, 2003. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).