Abstract

The Switched Reluctance Motor (SRM) is a strong candidate for high-performance industrial drives and electric vehicle (EV) propulsion due to its robust, magnet-free construction and high fault tolerance. However, its main drawback lies in its nonlinear behavior, which produces significant torque ripple and acoustic noise, thereby hindering its widespread adoption. In recent years, Finite Control Set Model Predictive Control (FCS-MPC) has emerged as a promising alternative to mitigate these issues. Nevertheless, existing implementations typically rely on an eight-vector set comprising both single-phase and dual-phase excitations with unequal magnitudes, resulting in a nonuniform distribution in the αβ-plane. Unlike the conventional square-shaped distribution of vectors where excitation alternates between one and two phases, this study proposes a novel vector set that consistently energizes two phases in each selection. This approach achieves a uniform circular distribution in the αβ-plane, enabling the voltage magnitude to remain constant. The proposed eight-vector set leads to smoother current transitions, reduced torque ripple, and improved dynamic behavior. The strategy is validated on the MATLAB/Simulink platform, with detailed comparative results presented against the conventional method. The findings demonstrate a torque ripple reduction of up to 58% and an acceleration time improvement of up to 64%. These results highlight the strong potential of the proposed method for scalable SRM performance enhancement in demanding applications such as EV propulsion systems.

1. Introduction

The Switched Reluctance Motor (SRM) has emerged as a strong contender for industrial drives and electric vehicle (EV) applications due to its simple and robust construction, inherent fault-tolerant capability, and excellent performance at high speeds. Distinct from traditional machines, the Switched Reluctance Motor (SRM) eliminates the need for permanent magnets or rotor windings, thus presenting a cost-effective and magnet-free alternative. The SRM is a salient pole machine that uses the magnetic reluctance minimization principle, where the magnetic torque is generated with the alignment of the rotor with the stator magnetized poles. Due to this principle, the motor relies on nonlinear behavior that results in a significant torque ripple and acoustic noise, which hinder broader adoption [1,2].

Achieving robust and smooth operation in SRMs, therefore, remains a key control challenge. A wide range of control strategies has been proposed, including conventional schemes such as voltage control, PI regulators, and hysteresis control [3], as well as more advanced methods such as Direct Torque Control (DTC) [4,5] and Angle Position Control (APC) [5]. Indirect approaches such as Torque Sharing Functions (TSFs) combined with hysteresis or PWM [6], Direct Instantaneous Torque Control (DITC) [7], and artificial intelligence (AI) have also been integrated into the predictive control of SRMs. Reinforcement learning (RL) methods, such as Q-learning scheduling and Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO)-based current controllers [8,9], have shown the ability to adapt online, improve current tracking, and reduce torque ripple without requiring explicit system models. These AI-assisted approaches highlight the potential of self-learning predictive controllers to enhance robustness under nonlinear and uncertain conditions, with each offering partial improvements in torque ripple reduction.

Model Predictive Control (MPC) has gained considerable attention due to its ability to handle nonlinear, multivariable systems while explicitly incorporating system constraints. A comprehensive review of MPC applications to SRMs is provided in [10], where strategies such as Model Predictive Current Control (MPCC), Model Predictive Torque Control (MPTC), and Model Predictive Flux Control (MPFC) are discussed.

For example, [11] applies MPC to a 6/4 SRM by formulating a finite-horizon optimal control problem directly at the converter level, achieving torque regulation while reducing phase currents and switching frequency. Finite Control Set (FCS-MPC) and Continuous Control Set (CCS-MPC) offer distinct computational advantages [12]. For instance, [13] introduces an FCS–MPTC scheme for a 12/8 SRM fed by a three-phase four-leg inverter, while [14] presents an FCS–MPDTC method for a 16/10 SRM prototype operating at low speeds. In [15], an MPTC strategy for an 8/6 SRM reduces computational complexity by lowering the number of candidate states from nine to six through a linear-model-based transformation. Similarly, Ref. [16] proposes an improved MPTC scheme that redefines commutation regions, reducing candidate vectors to only two or three per control cycle.

Among these strategies, FCS-MPC has emerged as one of the most promising due to its fast dynamic response, ability to address nonlinearities, and flexibility in balancing multiple objectives. However, most existing implementations rely on the conventional eight-vector set in 8/6 SRMs, which alternates between single-phase and dual-phase excitations of unequal magnitudes. This results in a nonuniform distribution in the αβ-plane, leading to uneven current slopes, torque ripple, and degraded transient behavior [17].

To address this limitation, this paper proposes a novel FCS-MPC strategy that introduces an alternative eight-vector set, in which two phases are always energized simultaneously while the vector magnitudes are kept constant. This design produces a circular and uniform distribution in the αβ-plane, eliminating the magnitude alternation and irregularity of conventional sets.

The proposed method is evaluated against the traditional FCS-MPC and a PWM baseline, with performance metrics including torque ripple, torque-per-ampere ratio, dynamic response, energy efficiency, and speed tracking accuracy. All simulations are conducted in MATLAB/Simulink 2024b to ensure a fair and reproducible comparison.

The key contributions of this work are summarized as follows:

- A novel eight-vector set for FCS-MPC is proposed, where two phases are always excited and the voltage magnitude remains constant, forming a circular and uniform distribution in the αβ-plane.

- The proposed strategy ensures smoother current transitions, reduced torque ripple, and a faster dynamic response compared with the conventional vector set.

- A detailed benchmarking study against both conventional FCS-MPC and PWM control is presented, showing torque ripple reductions of up to 58% and acceleration time improvements of up to 64%.

- Simulation profiling demonstrates a 73% reduction in computational time, highlighting the feasibility of real-time implementation for EV-oriented SRM drives.

The paper is organized as follows: Section II presents the mathematical model of the SRM. Section III describes the control strategy and details the implementation of the conventional and proposed vector sets. Section IV presents and discusses the simulation results. Finally, Section V concludes the study and outlines future research directions.

2. SRM Model

In this work, an 8/6 SRM is used, corresponding to a four-phase machine with eight stator poles and six rotor poles, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Basic configuration of the 8/6 SRM.

The mathematical model of the 8/6 SRM is developed in Simulink, based on the following Equation [3]:

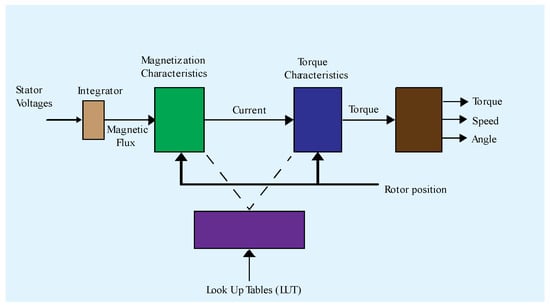

The block diagram illustrating the operating principle of the SRM is shown in Figure 2. The dot lines mean the look up tables data feeding the corresponding block.

Figure 2.

SRM block diagram.

To obtain the mathematical model of an SRM, it is essential to consider the relationship between the electrical angle and the mechanical angle, as expressed in the following equation [18]:

The main electrical and mechanical characteristics of the 8/6 SRM used in this study are summarized in Table 1. These parameters serve as the basis for the modeling and simulation process.

Table 1.

8/6 SRM characteristics.

The calculation of the electromagnetic torque in a Switched Reluctance Motor (SRM) requires first determining the magnetic flux and then the corresponding phase current. In this study, the analytical method proposed by Le-Huy [19] is adopted, and the torque is obtained using the following equations:

The inductance profile as a function of rotor position is modeled using a shape function, whose derivative with respect to the mechanical angle is expressed as follows:

The flux linkage and the electromagnetic torque, as functions of the phase current and rotor position , are expressed as follows:

As shown in Figure 1, the magnetic flux and rotor position are used as inputs to a lookup table derived from magnetic characterization data. A curvilinear interpolation method, described in [19], is applied to compute the phase current as a function of flux and position, forming the interpolated current block (ITBL). To determine the mechanical speed and rotor position of the motor, the following dynamic equation is employed:

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Conventional FCS Model Predictive Control

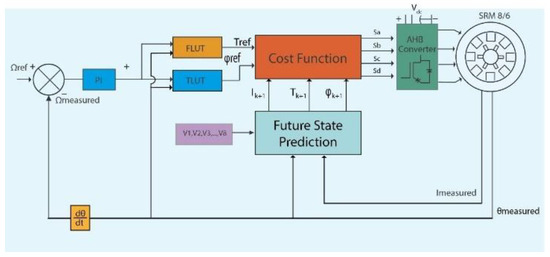

Finite Control Set Model Predictive Control (FCS-MPC) is an advanced strategy that relies on a predefined set of switching vectors to predict the future behavior of key system variables such as current, torque, flux, and rotor position. These predictions are evaluated through a cost function that incorporates reference values for each variable. The relative importance of each term can be tuned using weighting factors, enabling the controller to prioritize performance objectives such as torque ripple reduction, current tracking accuracy, and flux regulation, depending on the application requirements [20].

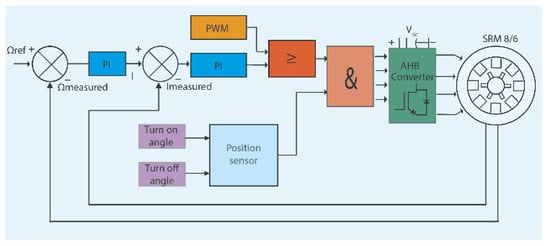

The operating principle of FCS-MPC is illustrated in Figure 3. The control loop begins by generating a speed error signal, defined as the difference between the measured speed and the reference setpoint. This error is processed by a PI controller to produce the reference current. Due to the strong nonlinear behavior of the SRM, where electrical variables depend heavily on rotor position, the following two Look-Up Tables (LUTs) are employed:

Figure 3.

FCS-MPC system block.

- A Torque Look-Up Table (TLUT) to determine the torque reference from the current reference.

- A Flux Look-Up Table (FLUT) to determine the flux reference under the same conditions.

These reference values are compared with the predicted torque and flux, obtained by evaluating the future system states for each voltage vector in the predefined control set. For every candidate vector, a cost function is calculated considering the weighted error terms, and the vector that minimizes this cost is applied to the converter in the next control cycle.

A set of eight switching vectors is defined for the Finite Control Set Model Predictive Control (FCS-MPC) strategy. The magnitude of each vector in the αβ-plane is calculated using the analytical expression given in Equation (10). The complete set of vectors is listed in Table 2, representing a standard configuration widely adopted in the literature [16,21,22].

Table 2.

Switching vectors for the conventional FCSMPC strategy.

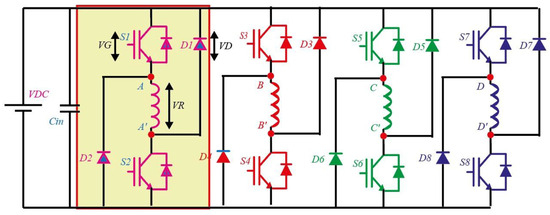

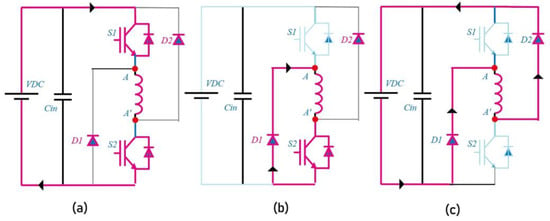

The asymmetric bridge converter, used to drive the Switched Reluctance Motor (SRM) as illustrated in Figure 4, operates in three distinct modes, as illustrated in Figure 5. Taking phase A as an example, the switching sequence can be described as follows:

Figure 4.

Asymmetric bridge converter topology.

Figure 5.

Asymmetric bridge converter modes of operation (a) Magnetization; (b) Free wheeling; (c) Demagnetization.

- Magnetization mode: Both switches S1 and S2 are turned ON, allowing current to flow through the phase A winding and build up magnetic flux (Figure 5a).

- Freewheeling mode: Switch S1 is turned OFF while S2 remains ON. In this mode, the current circulates through S2 and its corresponding freewheeling diode, maintaining flux without drawing energy from the source (Figure 5b).

- Demagnetization mode: Both S1 and S2 are turned OFF, forcing the stored magnetic energy to dissipate through the demagnetization path. The current reverses direction due to the inductive nature of the winding, ensuring complete de-excitation of the phase (Figure 5c).

For an 8/6 Switched Reluctance Motor (SRM) with four phases, the total number of switching combinations is 34 = 81, considering three states per phase (magnetization, freewheeling, and demagnetization). From this set, a subset of optimal vectors can be selected according to the following criteria:

- No more than two phases should conduct simultaneously.

- Direct transitions from magnetization to demagnetization modes should be avoided.

The methodology used to predict the system’s behavior is based on the analytical model proposed by Le-Huy, starting from the fundamental voltage equation, as follows:

The angular velocity is defined as follows:

By isolating the current derivative with respect to time, the following expression is obtained:

The partial derivatives of the magnetic flux with respect to rotor position and current are defined as follows:

To discretize the system, the forward Euler method is applied to Equation (13), yielding the following:

The mechanical angle prediction is obtained using the equation proposed in [13], as follows:

Once the predicted rotor position is available, it is substituted into the shape function derivative, as follows:

The predicted electromagnetic torque is then computed as follows.

The magnetic flux linkage is predicted as follows:

Finally, the cost function is defined as follows:

Table 3 summarizes the simulation parameters used in this study.

Table 3.

Simulation configuration parameters.

3.2. Proposed FCS Model Predictive Control

Previous studies have identified 81 possible switching vectors for the 8/6 Switched Reluctance Motor (SRM). However, due to practical constraints and converter operating conditions, this number is typically reduced to 72 feasible vectors. From this reduced set, a conventional subset of eight vectors shown in Table 2 is commonly selected as the basis for control implementations. Despite this, limited attention has been given to exploring alternative vector combinations beyond the conventional subset.

In this work, we introduce a novel vector selection strategy in which each switching vector simultaneously excites two phases, and all vectors are constrained to have identical magnitude. The resulting vector set, summarized in Table 4, ensures uniform excitation and balanced distribution in the αβ plane.

Table 4.

Switching vectors for the proposed FCS-MPC strategy.

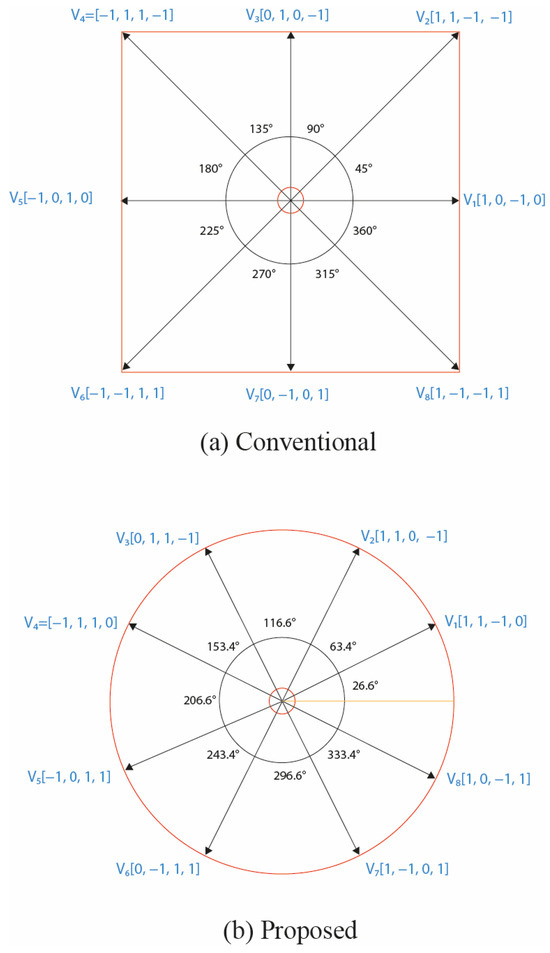

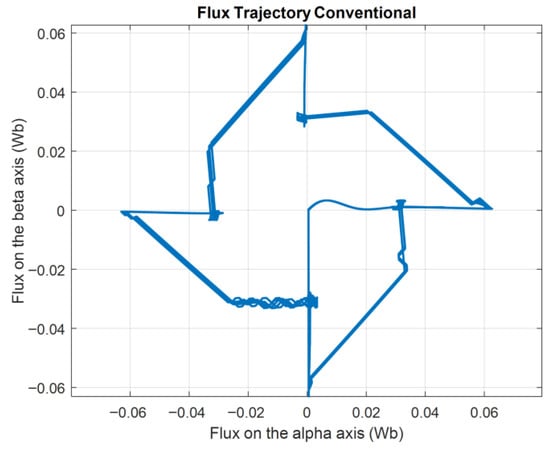

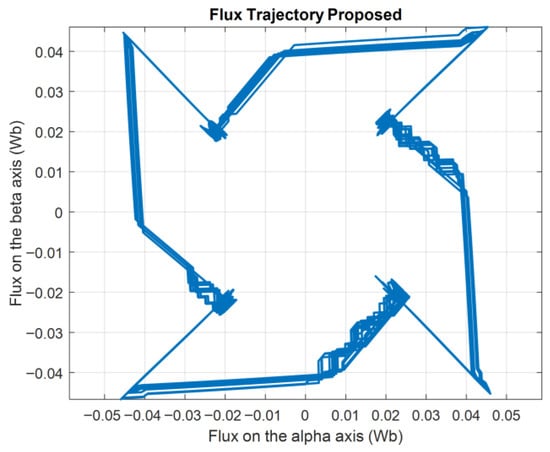

As illustrated in Figure 6b, the proposed vectors form a nearly circular trajectory in the αβ plane, in contrast to the irregular distribution observed with the conventional set in Figure 6a. This circular configuration enables smoother current transitions, as current dynamics are directly governed by the applied voltage vectors, which, in turn, strongly influence the developed torque. By maintaining uniform current slopes, the proposed method enhances control stability and significantly reduces torque ripple, one of the primary limitations of SRM drives.

Figure 6.

Set of vectors distributed on αβ plane.

In Figure 6a, the conventional approach produces an asymmetric octagonal trajectory. Four of the vectors correspond to single-phase excitations with |V| = 2, while the remaining four represent dual-phase excitations with |V| = 2.828. The alternation between single- and dual phase vectors introduces abrupt variations in the applied voltage magnitude, resulting in nonuniform current derivatives (di/dt). These discontinuities in the current evolution translate directly into pronounced torque ripple, given that electromagnetic torque depends quadratically on current and on the variation in inductance with rotor position, as described in (22).

By contrast, the proposed strategy (Figure 6b) constrains all eight active vectors to a constant magnitude of |V| = 2.23. This ensures a balanced voltage distribution throughout the electrical cycle and continuous torque contribution, eliminating discontinuities caused by single-phase excitation. The constant-amplitude, smoothly rotating voltage vector yields uniform di/dt during commutations, resulting in smoother current evolution, reduced torque ripple, and faster, more stable mechanical dynamics.

Overall, Figure 6 highlights the structural shift from an irregular, magnitude-varying polygon to a circular, constant-magnitude trajectory in the αβ plane. This geometric refinement forms the basis for the improved dynamic performance demonstrated in the subsequent simulation results (Figure 7, Figure 8, Figure 9, Figure 10, Figure 11, Figure 12 and Figure 13).

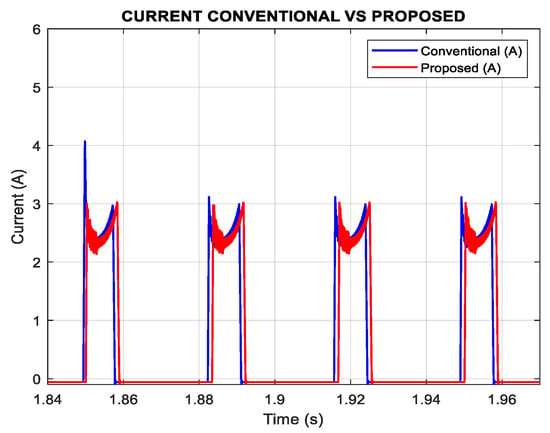

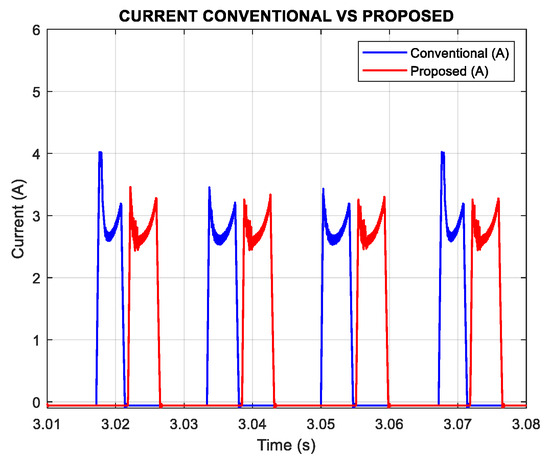

Figure 7.

Simulation results of current phase A n = 300 rpm Tl = 0.1 N*m.

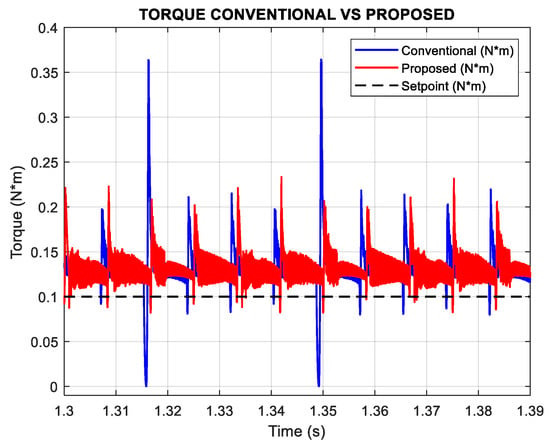

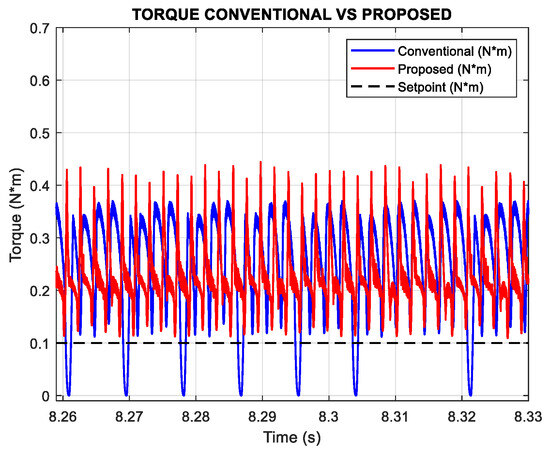

Figure 8.

Simulation results of torque n = 300 rpm Tl = 0.1 N*m.

Figure 9.

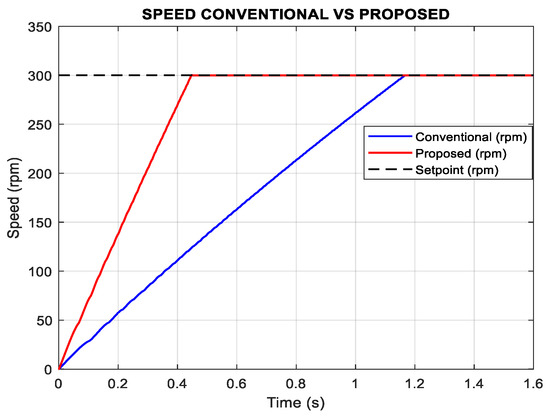

Simulation results of speed n = 300 rpm Tl = 0.1 N*m.

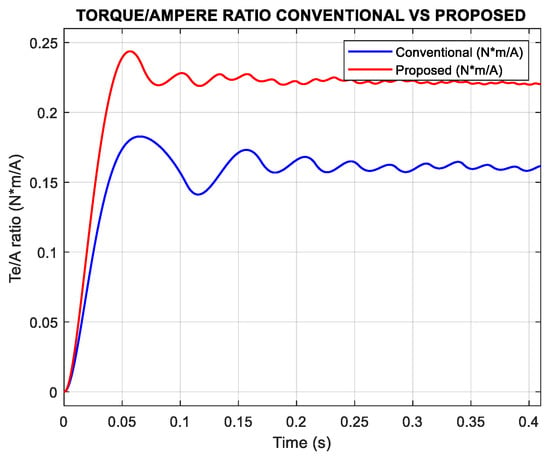

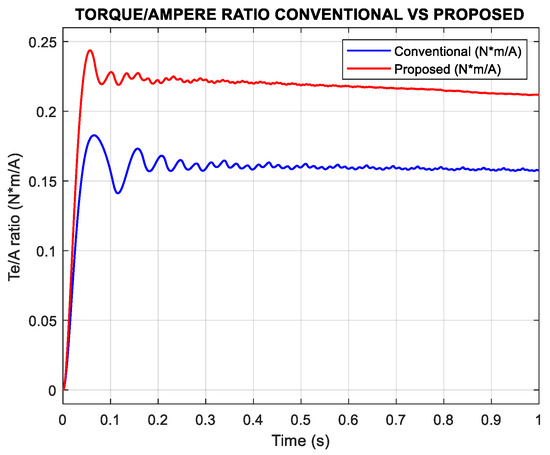

Figure 10.

Results of Te/A ratio conventional vs. proposed, n = 300 rpm Tl = 0.1 N*m.

Figure 11.

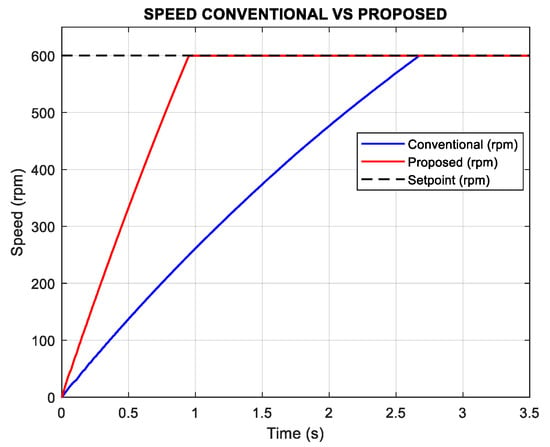

Simulation results of current phase A n = 600 rpm Tl = 0.1 N*m.

Figure 12.

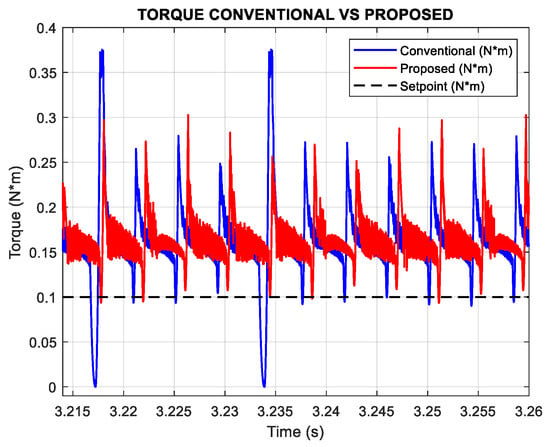

Simulation results of torque n = 600 rpm Tl = 0.1 N*m.

Figure 13.

Simulation results of speed n = 600 rpm Tl = 0.1 N*m.

The mathematical foundation to explaining the benefits of the proposed vector set is outlined as follows. In the conventional FCS-MPC implementation for a 4-phase SRM, the standard eight-vector set includes single-phase excitation vectors ∣V∣ = 2 and dual-phase excitation vectors with ∣V∣ = 2.828.

In the proposed method, all eight active vectors excite exactly two phases simultaneously and have equal magnitudes of ∣V∣ = 2.23 in the αβ plane.

They are uniformly spaced in an angle adjusted to match the dual-phase excitation geometry. Consequently, let be the voltage vector in αβ coordinates using (Equation (10)).

The conventional set satisfies , leading to an irregular octagon in αβ space. The proposed set maintains , forming a perfect circle in αβ space. From the SRM current evolution (Equation (13)), the magnitude of the applied voltage directly affects the slope . The conventional set alternates ∣V∣ between 2 and 2.828, resulting in the variable and in a nonuniform current rise and fall, notably when switching between single-phase and dual-phase vectors.

This causes torque ripple, since torque varies with the square of the current, as shown in Equation (22).

By contrast, the proposed control strategy maintains a constant vector magnitude, ensuring a uniform rate of current change. Because two phases are always excited simultaneously, continuous torque overlap is achieved, minimizing torque drops. The circular αβ trajectory distributes energy evenly across the electrical cycle, enhancing torque symmetry and improving the SRM’s speed and transient response, as described by the mechanical equation (Equation (9)).

As a result, the torque profile becomes smoother and more consistent, oscillations are reduced, acceleration is faster, overshoot is minimized, and higher operational points can be sustained under increased loads.

4. Results

The simulation tests were conducted at different rated speed values while maintaining the load torque below 0.1 N*m. The corresponding results are presented in Figure 7, Figure 8, Figure 9, Figure 10, Figure 11, Figure 12 and Figure 13. To compare the performance of the conventional and proposed methods, the following indices were used, as defined in Equations (23)–(25).

As illustrated in Figure 7, both the proposed and conventional control strategies achieve a peak phase current of approximately 3 A. However, the conventional method exhibits pronounced ripple during the rising transient, characterized by sharp variations in slope and amplitude. In contrast, the proposed approach ensures a much smoother current profile, with transient oscillations significantly reduced or nearly eliminated.

This improvement stems from the constant-magnitude dual-phase excitation, which promotes a more uniform current evolution. Furthermore, the proposed vector set yields smoother current rise and fall transitions, effectively suppressing the abrupt slope changes observed in the conventional waveforms.

By mitigating impulsive current variations, the proposed method reduces the torque spikes typically induced in such scenarios. Importantly, the peak phase current remains approximately 3 A for both methods, confirming that the proposed approach enhances dynamic performance without increasing current demand.

With the proposed method, torque pulses become more uniform, and the large transient spikes observed in the conventional vector set are effectively attenuated. Consequently, the proposed strategy achieves a lower torque ripple index and a reduction in high-frequency torque components.

As shown in Figure 8, the conventional approach exhibits significantly higher torque ripple, whereas the proposed method delivers a smoother and more consistent torque response. This comparative evaluation, performed at 300 rpm under a load torque of 0.1 N*m, confirms the superior ripple suppression capability of the proposed control scheme.

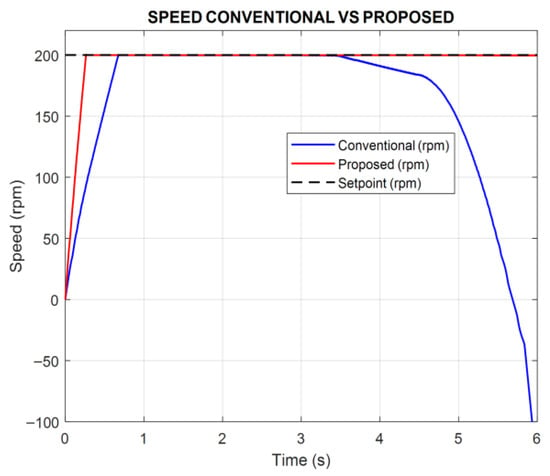

The proposed method exhibits a significantly faster dynamic response compared to the conventional approach. At 300 rpm with a load torque of 0.1 N*m, the proposed strategy reaches the reference speed in only 0.41 s, whereas the conventional controller requires 1.19 s to achieve the same target (Figure 9). Beyond the reduced acceleration time, the proposed method also shows less overshoot and faster settling, indicating improved torque delivery during transients and more effective phase overlap.

As shown in Figure 10, the proposed method achieves a significantly higher torque-per-ampere ratio compared to the conventional approach. Specifically, it reaches 0.22 N*m/A, while the conventional method achieves only 0.16 N*m/A under the same operating condition of 300 rpm with a load torque of 0.1 N*m.

Both methods exhibit a peak current of 3.2 A; however, the conventional strategy shows a noticeable increase in current ripple during the initial transient, a phenomenon that is substantially reduced or nearly absent in the proposed method, as illustrated in Figure 11.

At 600 rpm, the conventional controller produces a larger torque ripple, whereas the proposed method maintains a more stable torque output with reduced fluctuations, as shown in Figure 12.

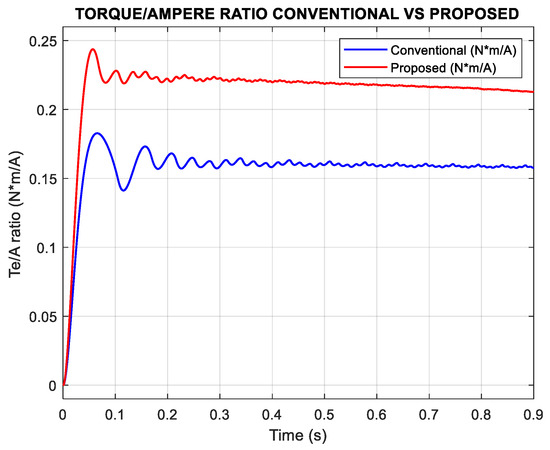

The proposed method reaches the reference speed in 0.9 s, significantly faster than the 2.52 s required by the conventional controller, thereby demonstrating its advantage in dynamic response (Figure 13). Consistent with the low-speed results, the proposed method also maintains a higher torque-per-ampere ratio compared to the conventional strategy, as illustrated in Figure 14.

Figure 14.

Results of Te/A ratio conventional vs. proposed, n = 600 rpm Tl = 0.1 N*m.

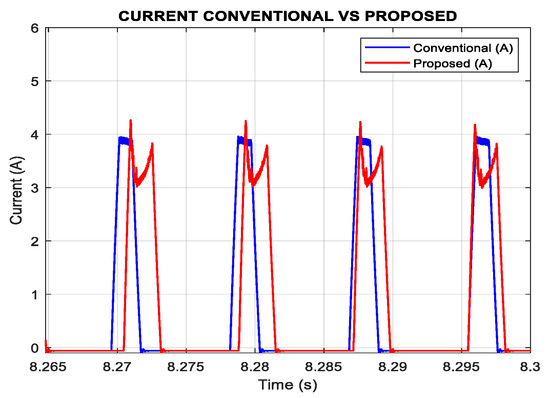

As illustrated in Figure 15, both the proposed and conventional methods reach a peak current of approximately 4 A. At lower speeds, the proposed strategy consistently produces smoother current waveforms, whereas the conventional method exhibits pronounced ripple. However, at higher speeds, this trend changes: the conventional waveform appears smoother, while the proposed method presents localized peaks. This behavior occurs because, under the proposed scheme, the SRM operates closer to partial magnetic saturation.

Figure 15.

Simulation results of current phase A n = 1200 rpm Tl = 0.1 N*m.

To validate this interpretation, a quantitative analysis of the magnetic characteristics is conducted. The aligned inductance decreases moderately from 23.6 mH in unsaturated conditions to about 20.0 mH under partial saturation, corresponding to a reduction of nearly 15%. Although less severe than full saturation, this drop in inductance accelerates the current dynamics (di/dt) for a given voltage.

As a result, at 1200 rpm, the elevated back-EMF reduces the effective voltage available for current buildup, and the controller compensates by injecting current more aggressively, as shown in Figure 15. This combination of reduced inductance and higher back-EMF explains the localized overshoots observed in the current waveforms of the proposed method.

Despite the apparently smoother current profile of the conventional method at this operating point, torque ripple analysis confirms that the proposed approach continues to achieve lower ripple levels. This outcome demonstrates that even under partial saturation, the constant-magnitude dual-phase excitation of the proposed vector set ensures superior torque quality compared to the conventional control strategy.

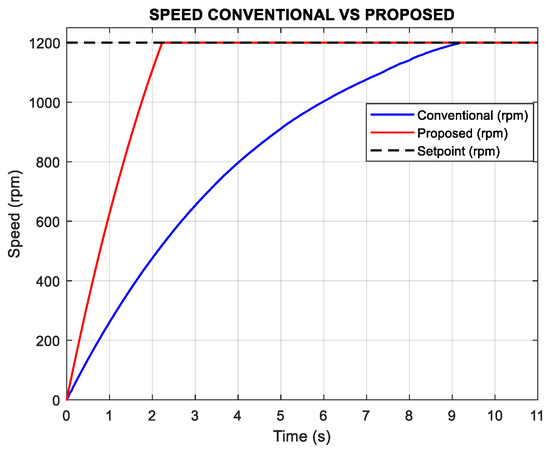

As shown in Figure 16, the proposed method reaches the speed setpoint much faster than the conventional approach. At 1200 rpm with a load torque of 0.1 N*m, the proposed method achieves the target in 2.2 s, whereas the conventional controller requires 9 s to reach the same value.

Figure 16.

Simulation results of speed n = 1200 rpm Tl = 0.1 N*m.

Figure 17 shows that the conventional method produces higher torque ripple compared to the proposed approach. In contrast, the proposed method delivers a more uniform torque response with reduced ripple. This evaluation is carried out at 1200 rpm under a load torque of 0.1 N*m.

Figure 17.

Simulation results of torque n = 1200 rpm Tl = 0.1 N*m.

Figure 18 shows that the torque-per-ampere ratio remains consistent with the values observed at lower speeds. The proposed method maintains a higher ratio, whereas the conventional method continues to exhibit a lower value under the same operating conditions.

Figure 18.

Results of Te/A ratio conventional vs. proposed, n = 1200 rpm Tl = 0.1 N*m.

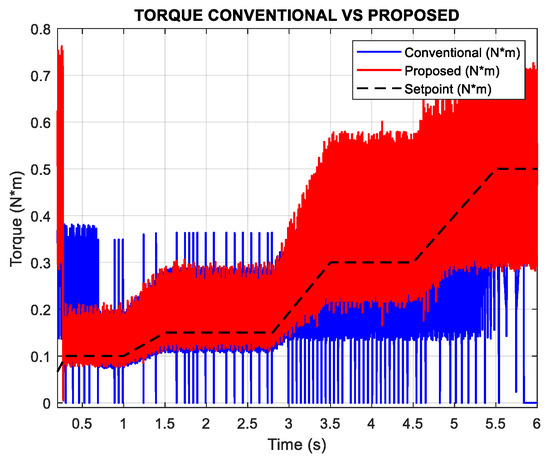

Figure 19 illustrates the torque setpoint tracking as the load increases. Under these conditions, the conventional method fails to maintain the reference speed, whereas the proposed method sustains it without difficulty. As shown in Figure 20, when the load reaches 0.3 N*m, the conventional method exhibits a noticeable speed droop, while the proposed method maintains smooth and stable speed tracking.

Figure 19.

Results of torque tracking increasing the torque setpoint n = 200 rpm.

Figure 20.

Results of speed tracking increasing the torque setpoint n = 200 rpm.

It is worth emphasizing that the proposed method increases the total harmonic distortion (THD) of the voltage by approximately 40–60% compared to the conventional FCS-MPC, while simultaneously reducing the current THD by 4–8%. From a power quality and machine efficiency perspective, this distinction is critical. Harmonic distortion in the stator current is directly linked to copper losses, additional heating, torque ripple, and reduced efficiency in SRM drives.

Therefore, minimizing current THD has a far more significant impact on motor performance and lifetime than the moderate increase in voltage THD. In contrast, voltage THD is less detrimental because the inductive nature filters high-frequency harmonics, preventing them from transferring directly into the torque production process. This explains why, despite higher voltage distortion, the proposed method achieves smoother current waveforms, reduced torque ripple, and an overall improved efficiency.

These benefits are particularly relevant for EV applications, where current distortion translates directly into higher energy consumption and thermal stress on the windings.

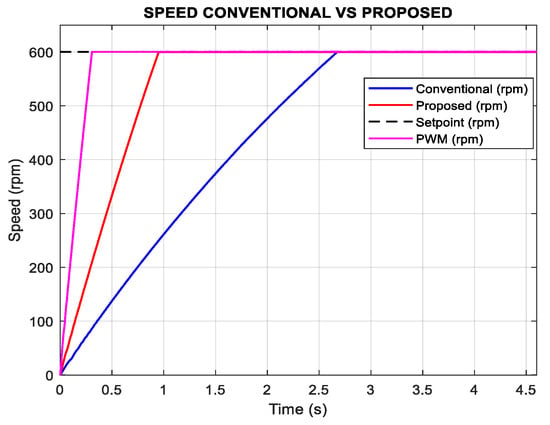

To further validate the proposed control strategy, a performance comparison was carried out against a conventional PWM-based control scheme at 600 rpm with a load torque of 0.1 N*m. The PWM controller was configured with a 2 kHz switching frequency, a turn-on angle of 42°, and a turn-off angle of 57°. The speed control loop used a PI regulator, while a separate PI controller was implemented for current regulation (Figure 21).

Figure 21.

PWM control block.

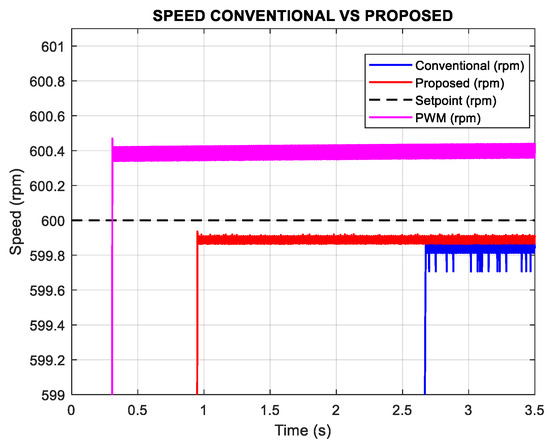

Although the PWM controller achieves the fastest transient response, reaching the reference speed in approximately 0.3 s compared to 2.6 s with the conventional FCS-MPC and 0.9 s with the proposed scheme (Figure 22), its steady-state accuracy is significantly inferior. As shown in Figure 23, the steady-state speed tracking error of the PWM method is about 0.10%, whereas the conventional and proposed FCS-MPC strategies achieve lower errors of 0.042% and 0.025%, respectively. This trade-off reflects the fundamental differences in control structure and switching strategy.

Figure 22.

Simulation results of speed FCS-MPC vs. PWM control n = 600 rpm Tl = 0.1 N*m.

Figure 23.

Simulation results of speed tracking error FCS-MPC vs. PWM control n = 600 rpm Tl = 0.1 N*m.

First, the PWM approach relies on fixed turn-on and turn-off angles (42° and 57° in this study) combined with PI controllers for current and speed regulation. This configuration allows for rapid current injection during transients, which explains the shorter acceleration times reported in Table 5.

Table 5.

PWM and FCS MPC comparative results.

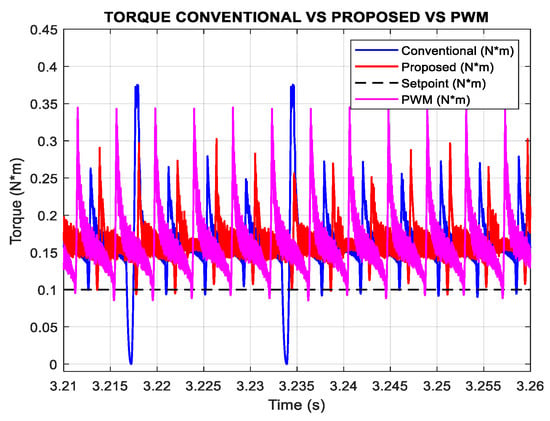

However, because the turn-on and turn-off angles are predetermined, PWM does not adaptively optimize phase excitation according to instantaneous rotor position or torque demand. As a result, once the transient subsides, the steady-state current waveform exhibits high ripple, and the torque production becomes highly irregular (Figure 24). This explains the high torque ripple index of nearly 272%, which is more than double that of the proposed FCS-MPC strategy.

Figure 24.

Simulation results of torque comparing FCS-MPC with PWM w = 600 rpm Tl = 0.1 N*m.

Second, the PI controllers used in PWM inherently introduce steady-state tracking errors in nonlinear systems such as SRMs, especially under varying operating conditions. In contrast, FCS-MPC directly incorporates system constraints and the prediction of future states into the control decision, enabling more precise current shaping and torque regulation. This predictive capability explains why both conventional and proposed FCS-MPC achieve superior steady-state speed tracking, despite slower transient acceleration compared to PWM.

Finally, the inductive nature of the SRM attenuates voltage harmonics but not current harmonics. PWM generates higher-order current harmonics due to its fixed switching frequency (2 kHz in this study), which increases copper losses and exacerbates torque ripple. The proposed FCS-MPC scheme, by contrast, minimizes current THD, even at the cost of higher voltage THD, ultimately improving torque quality and efficiency.

While PWM can accelerate the machine quicker, its inability to dynamically optimize excitation angles or minimize current harmonics leads to a poorer steady-state performance. This makes PWM less suitable for applications such as electric vehicle propulsion, where efficiency, torque smoothness, and precise speed tracking are critical. The comparative analysis (Figure 22, Figure 23 and Figure 24 and Table 5) clearly highlights the advantages of the proposed FCS-MPC method.

Figure 25 and Figure 26 present the α–β flux trajectories for the conventional and proposed control strategies, respectively. In the conventional method (Figure 25), the trajectory exhibits an irregular, asymmetric shape with nonuniform segment lengths, indicative of variable voltage vector magnitudes and inconsistent excitation between single- and dual-phase states. This irregularity can contribute to nonuniform current slopes and, consequently, higher torque ripple.

Figure 25.

Results of flux trajectory flux alpha vs. beta with conventional control.

Figure 26.

Results of flux trajectory flux alpha vs. beta with proposed control.

In contrast, the proposed method (Figure 26) produces a trajectory that is more uniform and closely aligned with a circular path, reflecting the constant magnitude voltage vector distribution in the αβ-plane.

This regular pattern ensures balanced excitation across all sectors, resulting in smoother current transitions, improved torque symmetry, and reduced torque ripple. The enhanced geometric uniformity of the flux trajectory directly correlates with the improved dynamic performance observed in the proposed control scheme.

To evaluate the computational efficiency of the proposed FCS-MPC method compared with the conventional approach, simulations were profiled using the built-in Simulink Profiler. Both models were executed under identical conditions: a fixed step size of 10 µs and a total simulation time of 4 s, corresponding to 400,000 discrete steps.

The profiling results, summarized in Table 6, show that the conventional controller required 415.36 s of run time, whereas the proposed method completed the same simulation in 109.75 s, representing a computational time reduction of approximately 73.6%.

Table 6.

Computational efficiency conventional vs. proposed.

Moreover, the run-to-simulation time ratio (CPU time required per simulated second) was 103.84 for the conventional controller, compared to only 27.44 for the proposed strategy. This metric further confirms that the proposed method is significantly more efficient and better suited for real-time implementation, particularly in embedded control systems where processing resources are limited.

Although this study focuses on an 8/6 SRM topology, the qualitative insights can be extended to other configurations, including 6/4, 12/8, and nonconventional geometries. However, the interplay between the rotor–stator pole ratio, the inductance profile, and the torque generation mechanism remains a determining factor in the relative effectiveness of each control strategy.

5. Discussion and Limitations

This study deliberately employs controlled simulations to isolate and evaluate the effect of the proposed constant-magnitude dual-phase vector set in FCS-MPC. This approach is consistent with predictive control research for SRMs, where MATLAB/Simulink is the de facto environment for first-stage validation prior to hardware replication, and in several cases [4,14,21] remains the sole validation tool for methodological studies.

Model scope: The SRM model integrates analytical magnetization characteristics with LUT-based interpolation of flux and torque versus current and position, while neglecting mutual coupling. This modeling strategy is well established in the MPC literature and has been shown to provide reliable predictive behavior for benchmarking control algorithms [19].

Simulation limits: Compared to a physical prototype, discrepancies may arise from device dead time, switching delays, DC-link dynamics, sensor quantization, parameter drift with temperature, structural compliance, and EMI-induced jitter in gate signals. These factors can modify current slopes, commutation timing, and, thus, torque ripple and dynamic response.

Mitigations in this study: To increase the robustness of the findings, we conducted (i) wide sweeps of speed and load conditions, (ii) operation near partial saturation, and (iii) benchmarking against PWM and conventional FCS-MPC baselines. Across all scenarios, the proposed method consistently outperformed alternatives in torque ripple, speed tracking, torque-per-ampere ratio, and efficiency indicators, with only modest increases in voltage THD.

The present validation is entirely simulation-based. While simulations provide a controlled, repeatable framework for isolating control effects, we fully acknowledge that experimental validation is essential for confirming robustness under real-world nonlinearities, parameter uncertainties, and hardware limitations. Following the progression established in prior works, we plan to extend this study to hardware-in-the-loop (HIL) setups and laboratory SRM prototypes as the next step toward deployment in electric vehicle applications.

6. Conclusions

This work presents a finite-control-set model predictive control (FCS-MPC) strategy for an 8/6 Switched Reluctance Motor (SRM), introducing a constant-magnitude voltage vector set that consistently excites two phases simultaneously. Unlike the conventional approach, which combines single- and dual-phase excitation vectors of nonuniform magnitudes, the proposed method generates a circular, evenly spaced trajectory in the αβ plane, ensuring smoother current transitions and more symmetric torque profiles.

MATLAB/Simulink simulations, conducted under identical operating conditions, lead to the following key conclusions:

The proposed method achieves up to 58% torque ripple reduction compared to the conventional controller, maintaining this improvement across a wide speed range, including near magnetic saturation.

Acceleration time is reduced by up to 64%, demonstrating a faster reaction to reference and load changes.

At low and medium speeds, the proposed controller delivers a substantially smoother current profile, minimizing the transient oscillations present in the conventional approach.

With a superior torque current ratio across all tested conditions, the proposed method achieves a higher torque-per-ampere ratio, indicating more efficient use of available current.

Regarding impact on harmonic distortion, while the proposed strategy moderately increases voltage THD, it reduces current THD, suggesting more favorable electromagnetic behavior of the machine.

Considering robustness under load variations in load-increase scenarios, the proposed method maintains the reference speed without significant droop, whereas the conventional approach experiences notable speed degradation.

Overall, the findings confirm that constant-magnitude dual-phase excitation not only enhances torque quality and current stability, but also provides notable dynamic advantages, making it a strong candidate for high-demand applications such as electric vehicle propulsion. However, the moderate increase in power losses and voltage THD should be considered in designs aiming for maximum efficiency.

Future work will include experimental validation on physical prototypes, adaptive optimization of the vector angular spacing, and the exploration of applicability to nonconventional SRM topologies and high-continuous-load operation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, writing—original draft preparation, F.S. and M.I.M.-M.; methodology, E.R.-C.; investigation, G.M.; writing—review and editing, J.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported in part by Universidad de las Fuerzas Armadas ESPE for supporting this work and by the European Regional Development Fund—“A way to make Europe”, under GR24040 project.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Universidad de las Fuerzas Armadas ESPE for supporting this work, including covering the registration fee related to the publication of this paper. Also this work was supported in part by the European Regional Development Fund – “A way to make Europe”, under GR24040 project.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Nomenclature

| Phase voltage | |

| Internal resistance of the stator winding | |

| Phase current | |

| Magnetic flux linkage | |

| Time | |

| Electrical angle | |

| Number of rotor poles | |

| Mechanical angle | |

| Flux linkage at aligned rotor position with maximum phase current | |

| Saturated inductance at aligned rotor position | |

| Unsaturated phase inductance at aligned rotor position | |

| Maximum phase current | |

| Unaligned inductance | |

| Electrical torque | |

| Inertia | |

| Friction coefficient | |

| Angular speed | |

| Load torque | |

| Phase A, B, C, D voltage | |

| Voltage in the alfa beta frame | |

| Sampling period | |

| Torque weighting factor | |

| Flux weighting factor | |

| Torque reference | |

| Flux reference | |

| Torque ripple | |

| Root mean square phase current | |

| Average torque to ampere ratio | |

| Torque average | |

| Minimum total instantaneous torque | |

| Maximum total instantaneous torque | |

| Conduction time of phase current during testing period. | |

| Speed | |

| Load Torque |

References

- Mohanraj, D.; Gopalakrishnan, J.; Chokkalingam, B.; Mihet-Popa, L. Critical Aspects of Electric Motor Drive Controllers and Mitigation of Torque Ripple—Review. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 73635–73674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, L.; Fan, Z.; Huang, J.; Cheng, Q.; Zhao, D.; Song, S.; De Doncker, R.W. Model Predictive Control of Switched Reluctance Machines with Online Torque Sharing Function Based on Optimal Flux-Linkage Curve. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrif. 2024, 10, 4990–5001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, F.; Milanés, M.; Romero, E.; González, E.; Roncero, C.; Barrero, F. A Simulation Based Comparison of Pwm and Dtc Control for 8/6 Srm. In Proceedings of the 2025 19th Conference on Electrical Machines, Drives and Power Systems (ELMA), IEEE, Sofia, Bulgaria, 19–21 June 2025; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanraj, D.; Gopalakrishnan, J.; Chokkalingam, B.; Ojo, J.O. An Enhanced Model Predictive Direct Torque Control of SRM Drive Based on a Novel Modified Switching Strategy for Low Torque Ripple. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Power Electron. 2024, 12, 2203–2213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, L.; Sun, X.; Bramerdorfer, G.; Zhu, Z.; Cai, Y.; Diao, K.; Chen, L. A review on control techniques of switched reluctance motors for performance improvement. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2024, 199, 114454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Gan, C.; Ni, K.; Chen, Y.; Qu, R. A Simplified PWM Strategy for Open-Winding Flux Modulated Doubly-Salient Reluctance Motor Drives with Switching Action Minimization. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2023, 70, 2241–2253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Dong, Z.; Liu, H.; Liu, Y.; Wu, Y. Direct Instantaneous Torque Control of SRM Based on a Novel Multilevel Converter for Low Torque Ripple. World Electr. Veh. J. 2023, 14, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prestes, G.X.; Moreira, W.K.; Scalcon, F.P.; Rech, C.; Knight, A.M.; Vieira, R.P. Reinforcement Learning-Based Current Controller for Switched Reluctance Motor Drives. In Proceedings of the International Electric Machines and Drives Conference, IEMDC 2025, Houston, TX, USA, 18–21 May 2025; Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2025; pp. 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharkan, H.; Saadatmand, S.; Ferdowsi, M.; Shamsi, P. Optimal tracking current control of switched reluctance motor drives using reinforcement Q-learning scheduling. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 9926–9936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.; Dou, X.; Cheok, A.D.; Ding, W.; Yan, Y.; Zhang, X. Model Predictive Control Strategies in Switched Reluctance Motor Drives—An Overview. IEEE Trans Power Electron. 2025, 40, 1669–1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peyrl, H.; Papafotiou, G.; Morari, M. Model Predictive Torque Control of a Switched Reluctance Motor. In Proceedings of the 2009 IEEE International Conference on Industrial Technology, Churchill, VIC, Australia, 10–13 February 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Khalilzadeh, M.; Vaez-Zadeh, S.; Rodriguez, J.; Heydari, R. Model-Free Predictive Control of Motor Drives and Power Converters: A Review. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 105733–105747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, D.; Ding, W.; Wang, Y.; Wang, K.; Chen, S.; Cai, J. Finite Control Set Model Predictive Torque Control of Switched Reluctance Motor Based on Three-Phase Four-Leg Inverter. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2025, 72, 9931–9941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Cui, Z.; Ding, S.; Chen, F.; Guo, Y. Model Predictive Direct Torque Control of Switched Reluctance Motors for Low-Speed Operation. IEEE Trans. Energy Convers. 2022, 37, 1406–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, G.; Ye, J.; Xiao, D.; Xia, Z.; Emadi, A. Computational-Efficient Model Predictive Torque Control for Switched Reluctance Machines with Linear-Model-Based Equivalent Transformations. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2022, 69, 5465–5477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, W.; Li, J.; Yuan, J. An Improved Model Predictive Torque Control for Switched Reluctance Motors with Candidate Voltage Vectors Optimization. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2022, 70, 4595–4607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valencia, D.F.; Tarvirdilu-Asl, R.; Garcia, C.; Rodriguez, J.; Emadi, A. A Review of Predictive Control Techniques for Switched Reluctance Machine Drives. Part II: Torque Control, Assessment and Challenges. IEEE Trans. Energy Convers. 2021, 36, 1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, R. Switched Reluctance Motor Drives: Modeling, Simulation, Analysis, Design, and Applications; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Le-Huy, H.; Brunelle, P. A versatile nonlinear switched reluctance motor model in simulink using realistic and analytical magnetization characteristics. In Proceedings of the IECON Proceedings (Industrial Electronics Conference), 2005, Raleigh, NC, USA, 6–10 November 2005; pp. 1556–1561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valencia, D.F.; Tarvirdilu-Asl, R.; Garcia, C.; Rodriguez, J.; Emadi, A. A Review of Predictive Control Techniques for Switched Reluctance Machine Drives. Part I: Fundamentals and Current Control. IEEE Trans. Energy Convers. 2021, 36, 1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deepak, M.; Janaki, G.; Bharatiraja, C. Performance Evaluation of Direct Torque Control and Model Predictive Control Based on Voltage Vector Strategy for SRM Drive. In Proceedings of the 2024 3rd International Conference on Power, Control and Computing Technologies, ICPC2T 2024, Raipur, India, 18–20 January 2024; Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 363–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, A.; Shang, C.; Chen, J.; Zhu, J.; Han, L. A New Control Method Based on DTC and MPC to Reduce Torque Ripple in SRM. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 68584–68593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).