Overvoltage Challenges in Residential PV Systems in Poland: Annual Loss Assessment and Mitigation Strategies

Abstract

1. Introduction

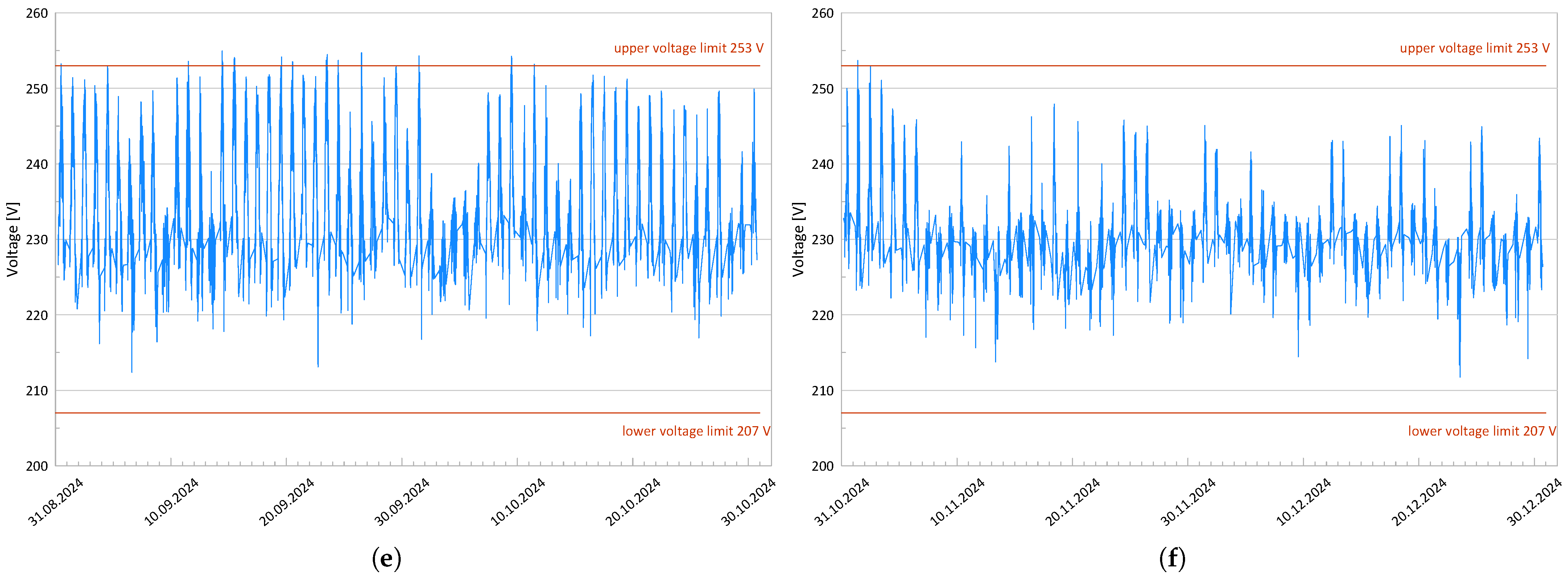

Voltage Rise in the Distribution Grid

- —receiving node voltage;

- —feeding node voltage;

- R, X—resistance and reactance of the line between the feeding node and the receiving node, respectively;

- , —active and reactive load, respectively;

- , —active and reactive power generation, respectively.

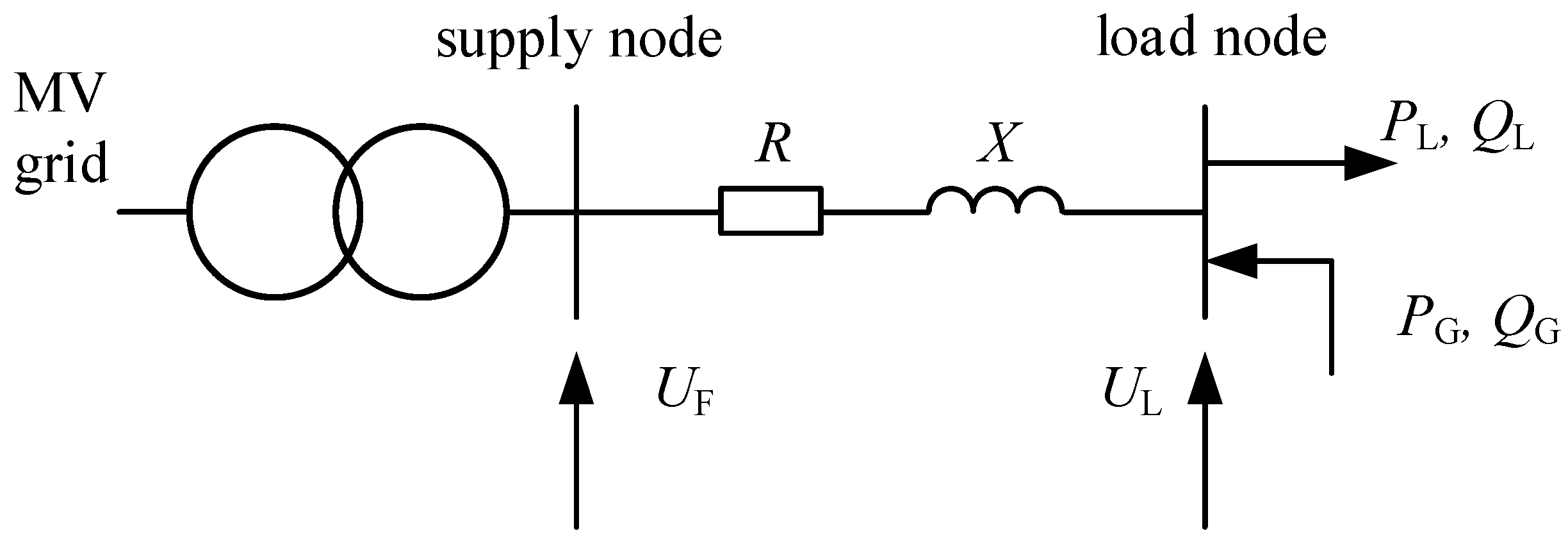

2. Methods

- Location of the PV system: the south-eastern part of Poland;

- Azimuth () and tilt angle ();

- Components of the photovoltaic installation: 12 modules Risen Energy, model: RSM60-6-310M, Ningbo city, China (total installed PV power 3.72 kWp), monophased Solar Edge Technologies, model: SE3680H-EU-APAC inverter (Izrael) connected to 12 P370 Solar Edge optymizers;

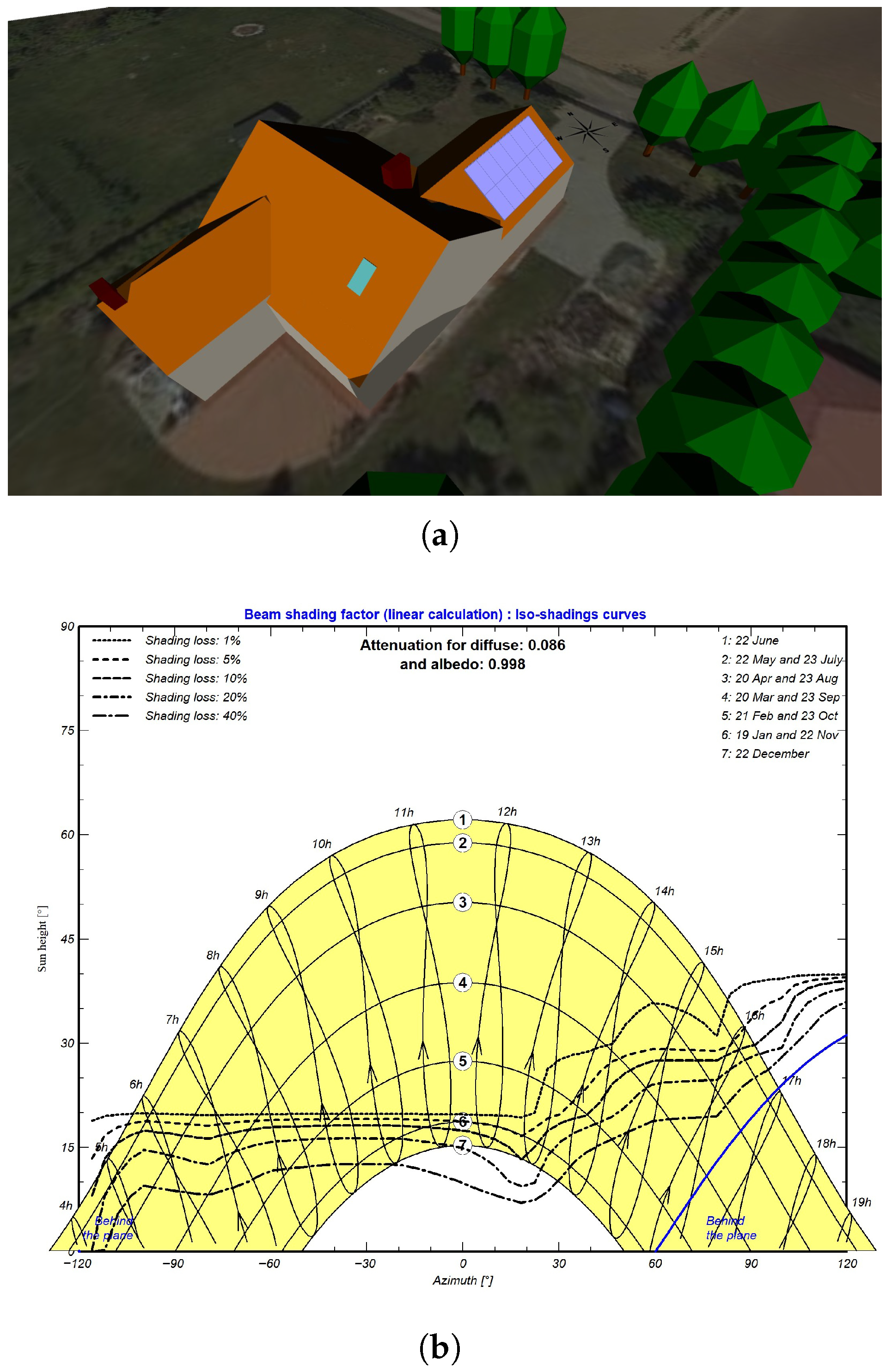

- A detailed 3D scene with all objects that can cast shadows (Figure 3a);

- Influence of shadows from nearby objects on irridiance level as well as on the PV electrical circuit (Figure 3b);

- The PV modules electrical circuit configuration has been introduced to provide specific information regarding the influence of shadows on the performance of PV modules;

- The length of the DC circuit and the cross sections of the DC wires.

- —actual (observed) value of PV power generation at index i;

- —predicted by clear sky model value of PV power at index i;

- n—total number of observations;

- —maximum of the observed values;

- —minimum of the observed values.

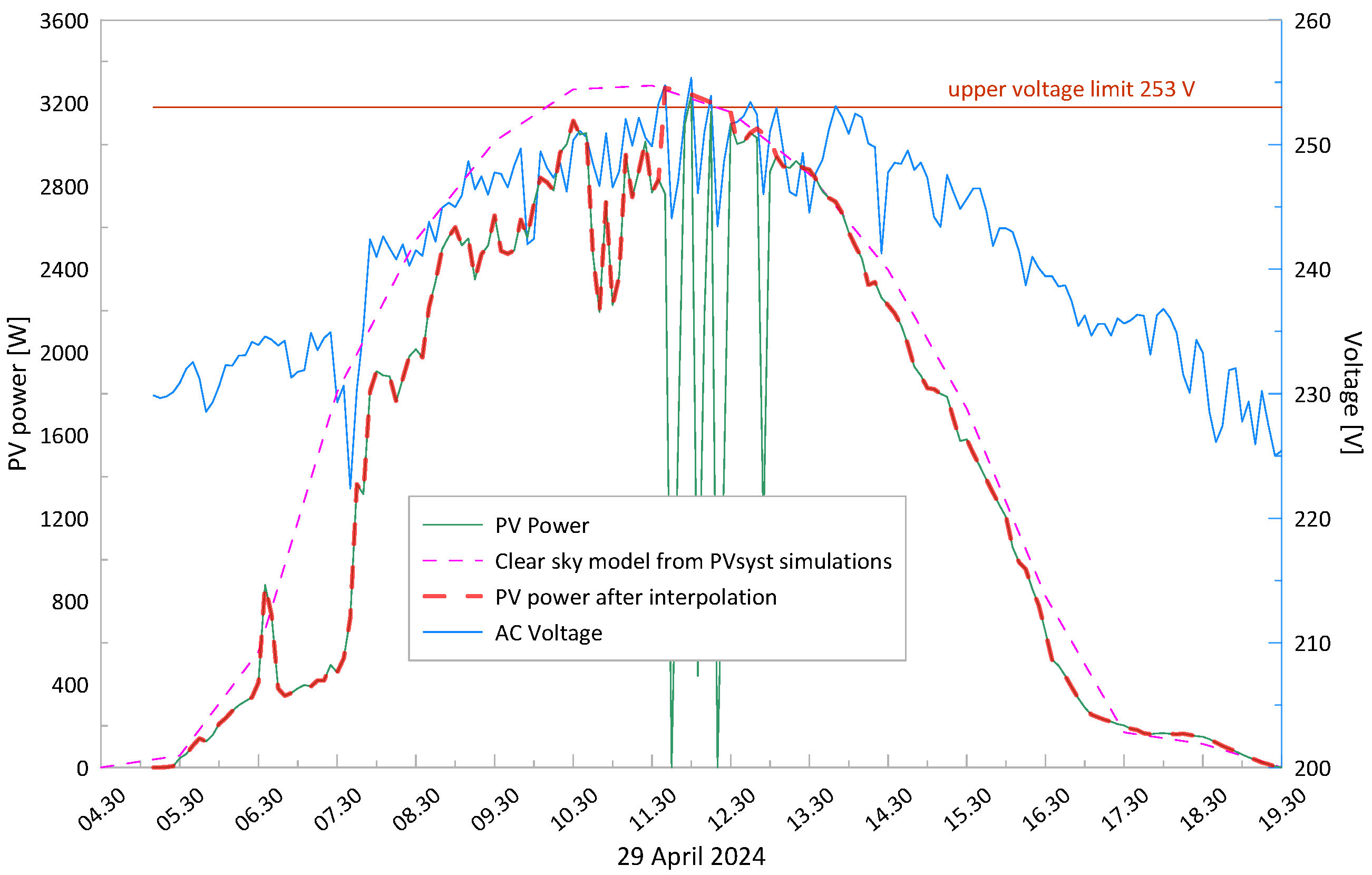

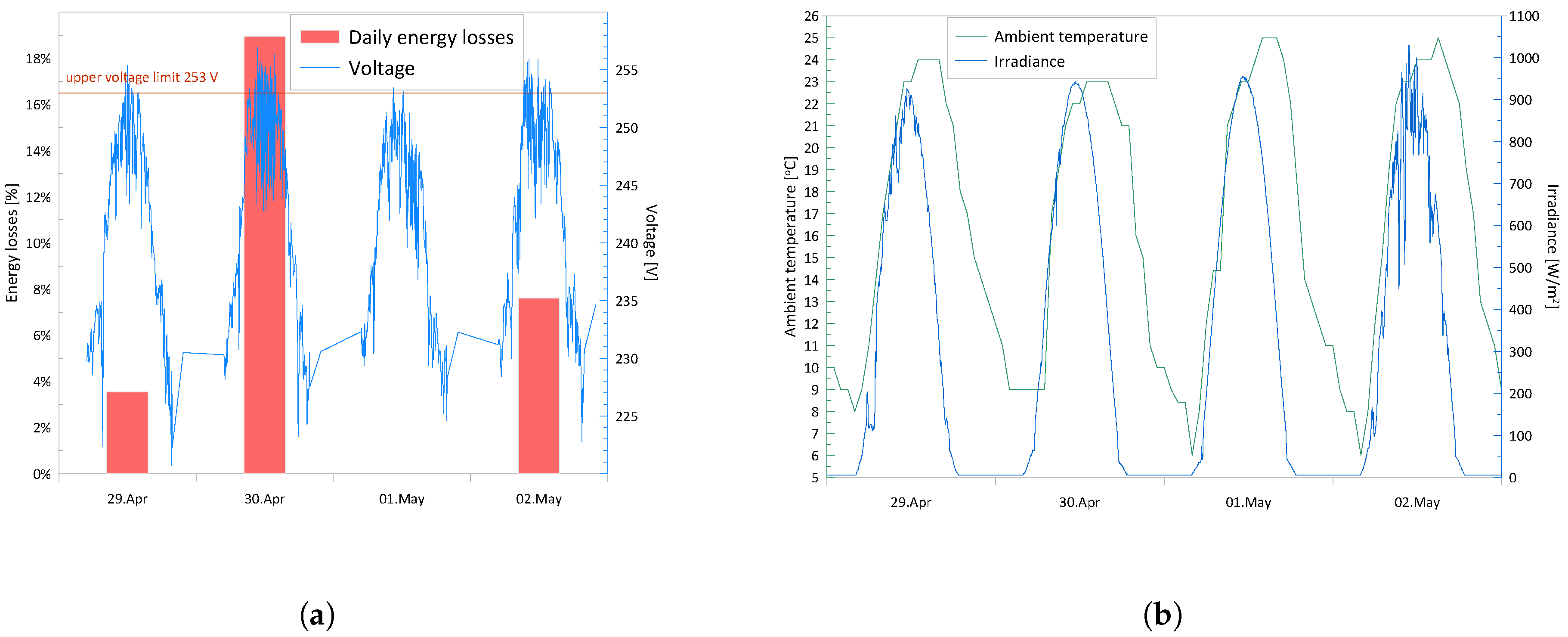

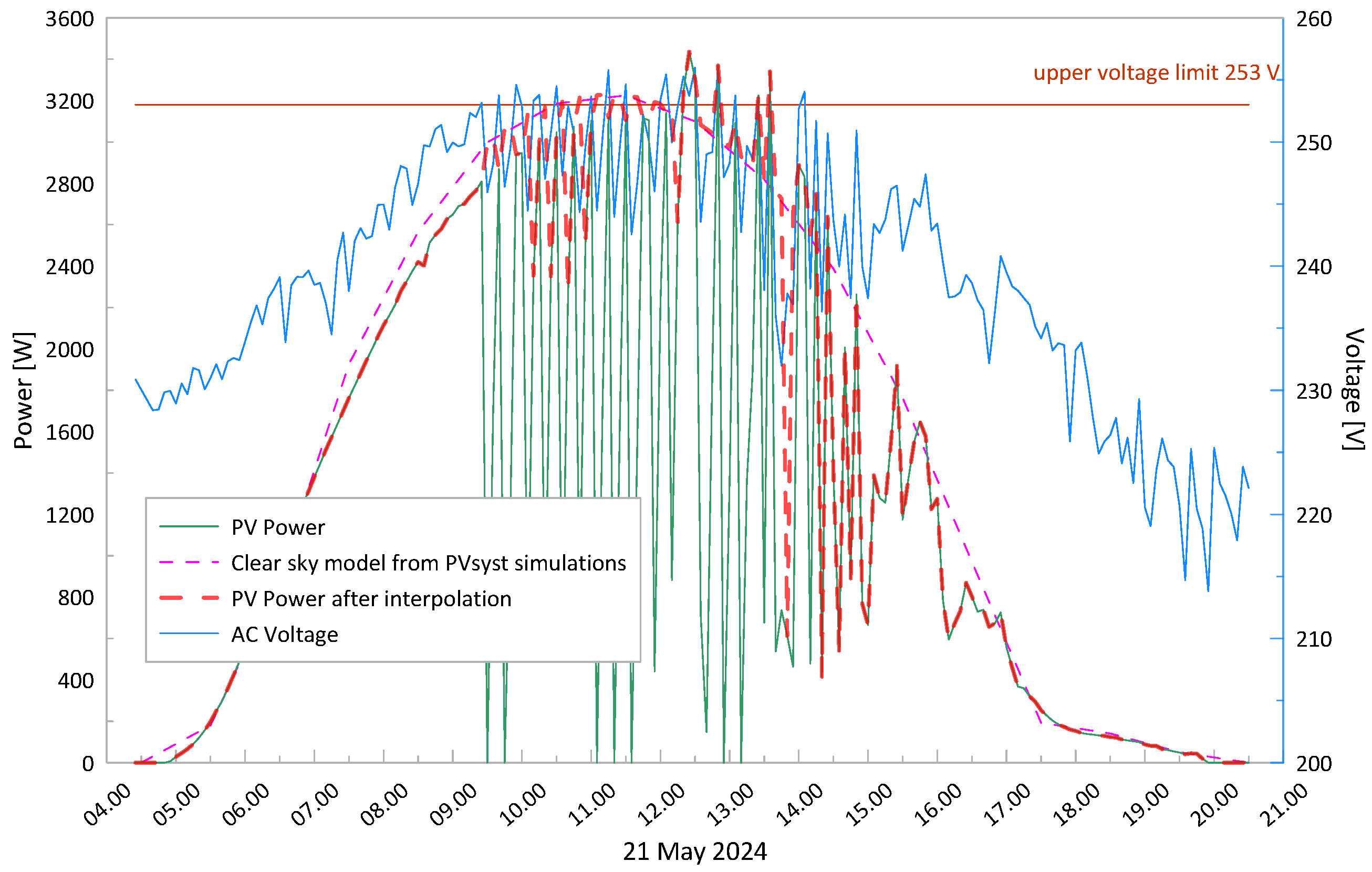

- Identification of the power drops caused by overvoltage;

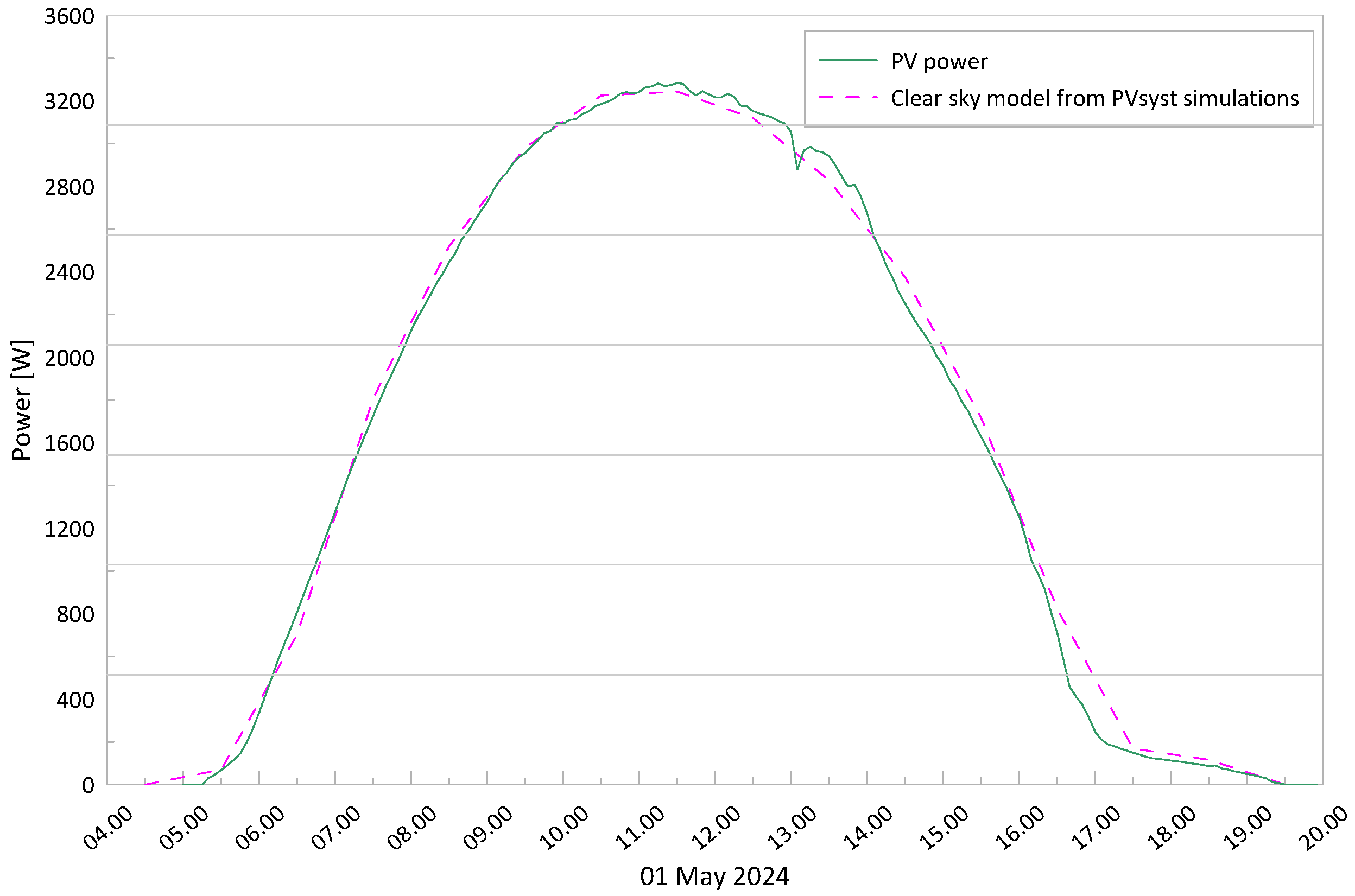

- The PVsyst simulation and extraction of the reference power curve, based on the clear-sky model (), was conducted for a specified day;

- Cubic interpolation [40] was applied using piecewise cubic polynomials ensuring continuity of the first and second derivatives (cubic splines). This approach provides a smooth fit to the data without introducing excessive oscillations. The interpolation was performed based on a reference curve ;

- The power curve after interpolation () provided information regarding the PV power without overvoltage power drops;

- The integration of the and curves post-time enabled the calculation of the energy produced by the PV on a given day, as well as the energy that would have been produced if there had been no power drops associated with overvoltage;

- The energy losses resulting from overvoltage were determined.

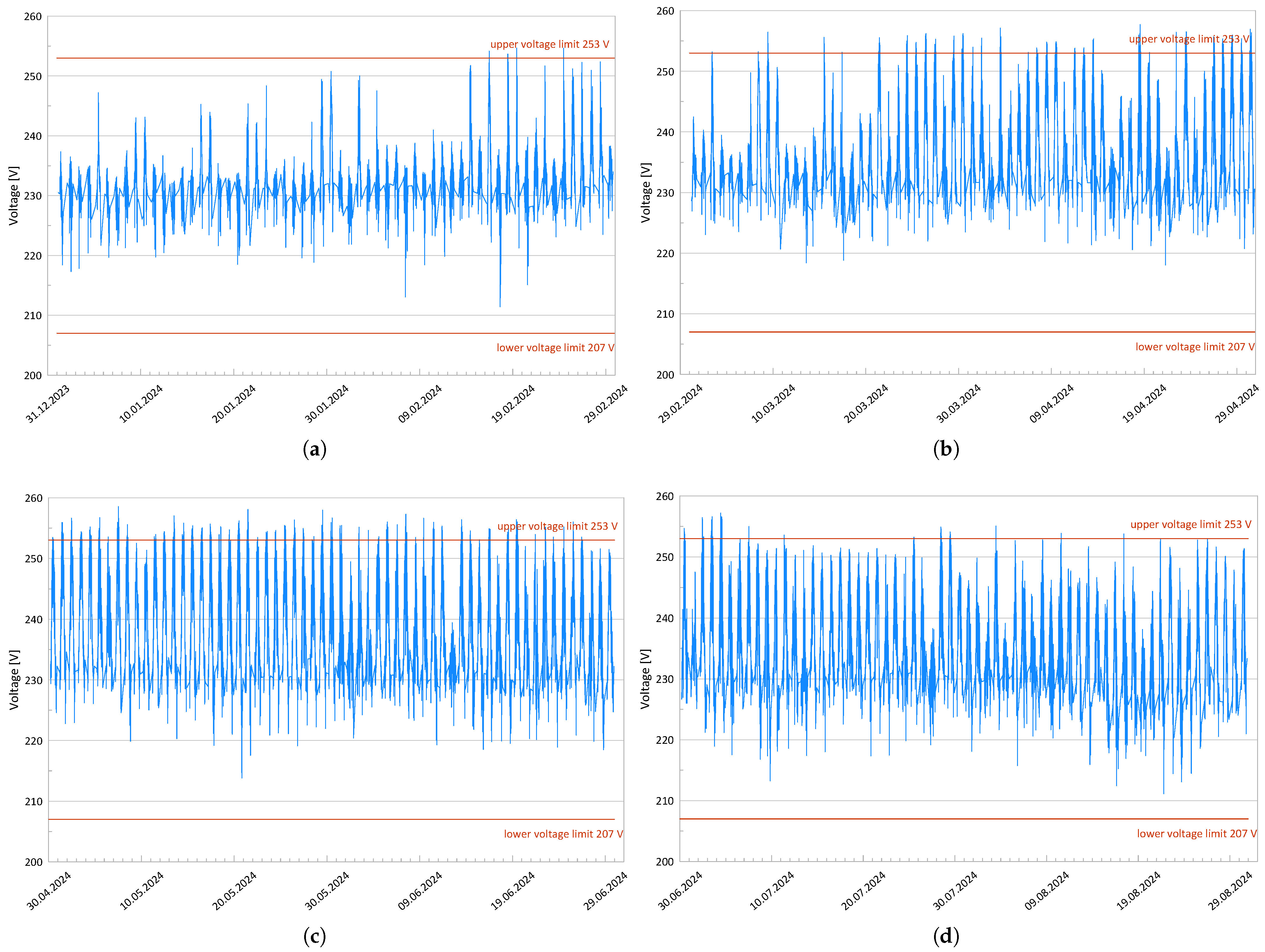

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Modernization of LV Grids

3.2. Installation of MV/LV Transformer with On-Load Tap Changer

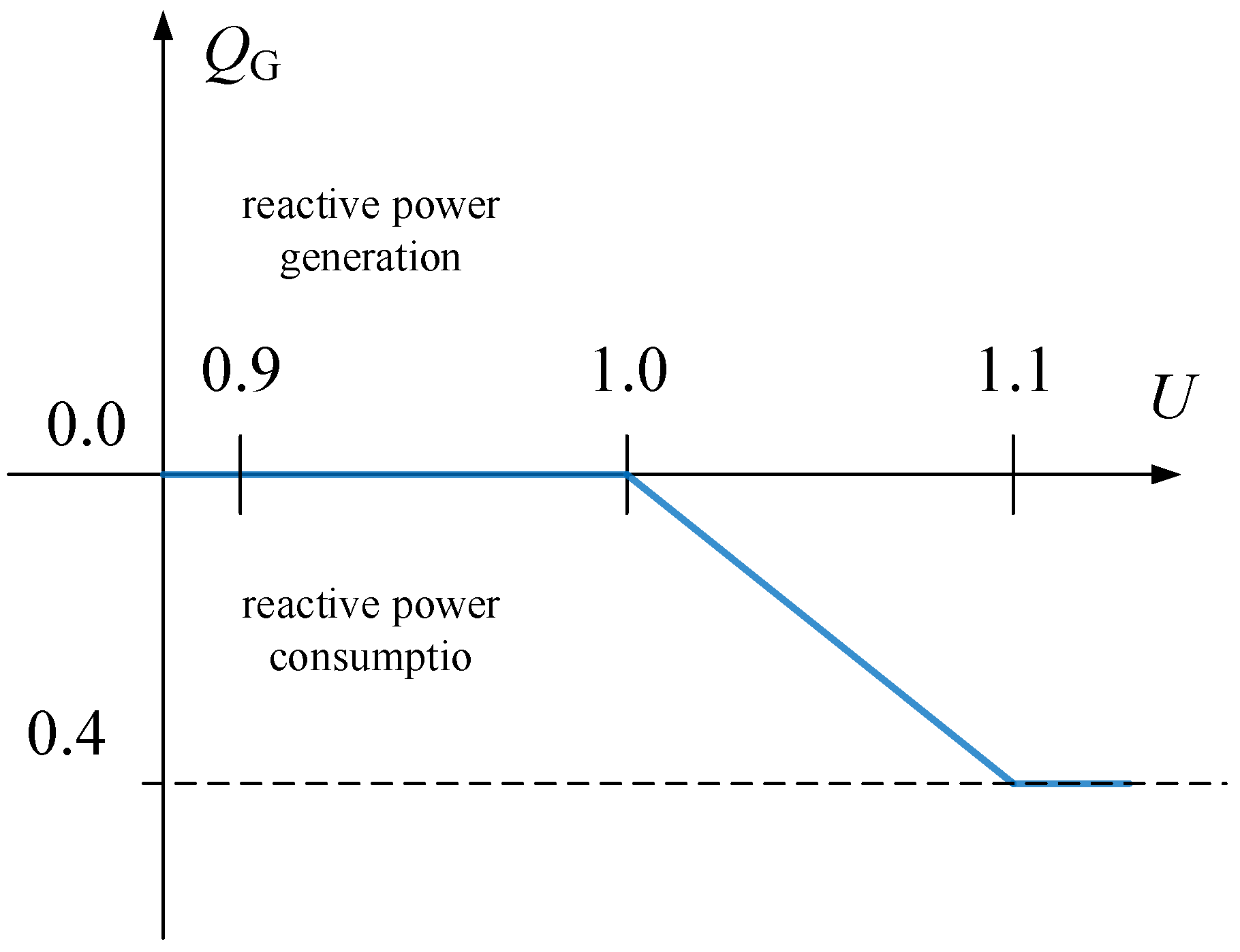

3.3. Reactive Power Regulation

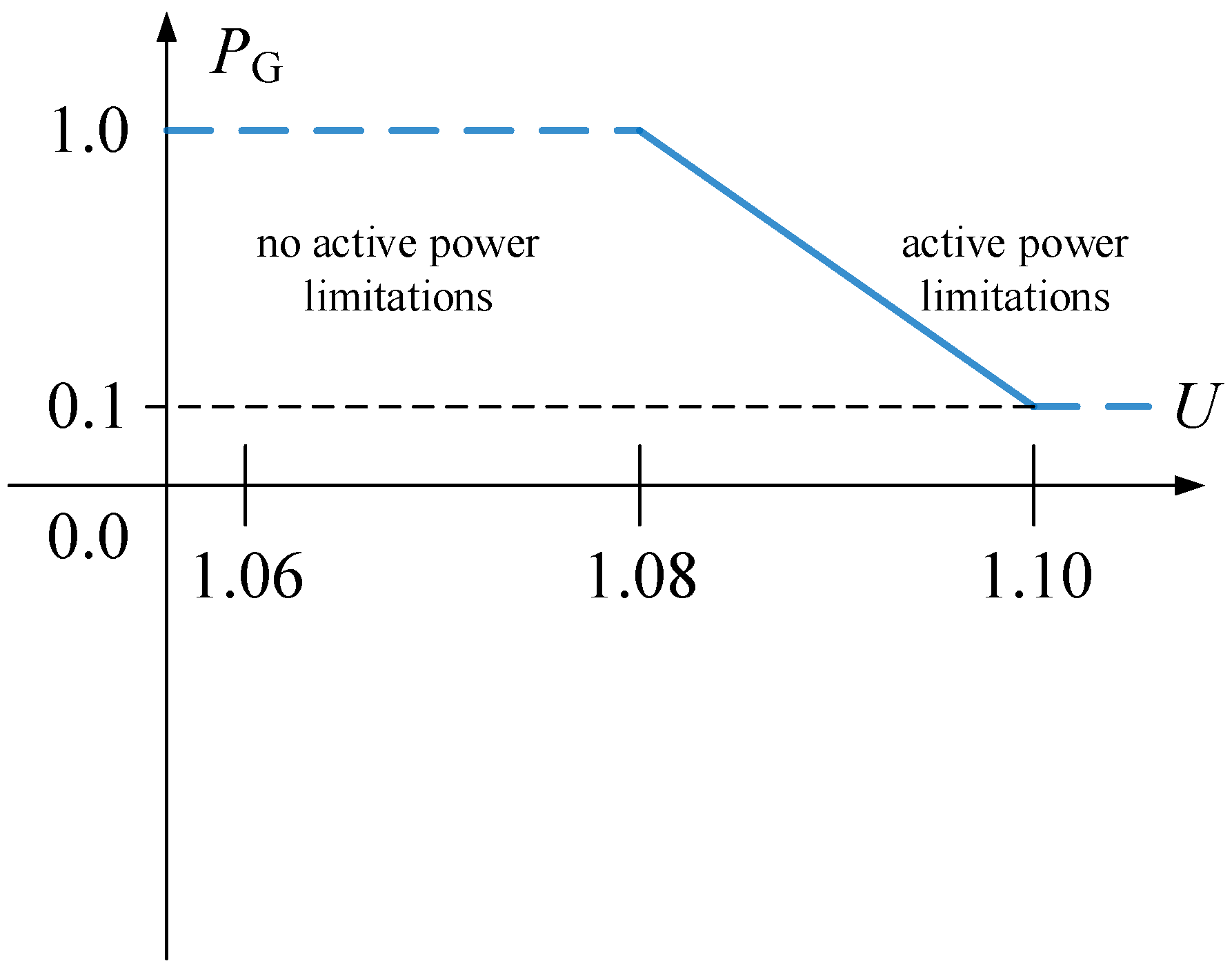

3.4. Active Power Limitation

3.5. Voltage Increase Reduction Methods—Summary

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| RES | Renawable energy sources |

| PV | Photovoltaic |

| SC | Self-consumption of the produced energy by photovoltaic system |

| AC | Alternating current |

| DC | Direct current |

| DSO | distribution system operator |

| LV | Low voltage |

| MV | Medium voltage |

| HV | High voltage |

| RED | Renewable energy directives |

| Symbols | |

| Receiving node voltage | |

| Feeding node voltage | |

| R, X | Resistance and reactance of the line between the feeding node and the receiving node |

| , | Active and reactive load, respectively |

| , | Active and reactive power generation, respectively |

| Voltage over time dependence | |

| Power over time dependence for the clear sky model | |

| Power over time dependence after eliminating power drops by interpolation | |

| The normalized root mean square error | |

| Actual value of PV power generation at index i | |

| Predicted by clear sky model value of PV power at index i | |

| n | Total number of observations |

| Maximum of the observed PG values | |

| Minimum of the observed PG values | |

Appendix A

References

- Forum Energii. Available online: https://www.forum-energii.eu/en/monthly-magazine-1 (accessed on 21 May 2025).

- Kulpa, J.; Olczak, P.; Surma, T.; Matuszewska, D. Comparison of Support Programs for the Development of Photovoltaics in Poland: My Electricity Program and the RES Auction System. Energies 2022, 15, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Institute for Renewable Energy. Photovoltaic Market in Poland. 2024. Available online: https://ieo.pl/raport-rynek-fotowoltaiki-w-polsce-2024 (accessed on 21 May 2025).

- Sjoerd, C.D.; Phuong, N.; Koen, K. Challenges for large-scale Local Electricity Market implementation reviewed from the stakeholder perspective. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 165, 112569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kijo-Kleczkowska, A.; Bruś, P.; Więciorkowski, G. Profitability analysis of a photovoltaic installation—A case study. Energy 2022, 261, 125310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Act of 20 February 2015 on Renewable Energy Sources (In Polish: Ustawa z Dnia 20 Lutego 2015 r. o Odnawialnych Źródłach Energii (Dz.U. 2015, poz. 478)). Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/download.xsp/WDU20150000478/T/D20150478L.pdf (accessed on 3 June 2025).

- Hanzel, K. Analysis of Financial Losses and Methods of Shutdowns Prevention of Photovoltaic Installations Caused by the Power Grid Failure in Poland. Energies 2024, 17, 946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janiga, K. Overvoltage Protection of PV Microinstallations—Regulatory Requirements and Simulation Model. Inform. Autom. Pomiary Gospod. Ochr. Sr. 2021, 11, 40–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talha, M.; Raihan, S.R.S. Rahim, N.A. PV inverter with decoupled active and reactive power control to mitigate grid faults. Renew. Energy 2020, 162, 877–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.; Pompodakis, E. Optimal conductor repositioning to mitigate adverse impacts of photovoltaics in LV networks. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2023, 216, 109050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashemi, S.; Østergaard, J. Methods and strategies for overvoltage prevention in low voltage distribution systems with PV. IET Renew. Power Gener. 2017, 11, 205–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmud, N.; Zahedi, A. Review of control strategies for voltage regulation of the smart distribution network with high penetration of renewable distributed generation. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 64, 582–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appen, J.; Braun, M.; Stetz, T.; Diwold, K.; Geibel, D. Time in the Sun: The Challenge of High PV Penetration in the German Electric Grid. IEEE Power Energy Mag. 2013, 11, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pompodakis, E.E.; Drougakis, I.A.; Lelis, I.S.; Alexiadis, M.C. Photovoltaic systems in low-voltage networks and overvoltage correction with reactive power control. IET Renew. Power Gener. 2016, 10, 410–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gimenes, T.K.; Coelho da Silva, M.P.; Ledesma, J.J.G.; Ando, O.H. Impact of distributed energy resources on power quality: Brazilian scenario analysis. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2022, 211, 108249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PN-EN 50160:2023-10; Supply Voltage Parameters in Public Distribution Networks. Polski Komitet Normalizacyjny: Warszawie, Poland, 2023. Available online: https://sklep.pkn.pl/pn-en-50160-2023-10e.html (accessed on 3 June 2025).

- Licari, J.; Rhaili, S.; Micallef, A.; Staines, C. Addressing voltage regulation challenges in low voltage distribution networks with high renewable energy and electrical vehicles: A critical review. Energy Rep. 2025, 14, 2977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, T.; Kanwar, N.; Sharma, M.K. Net metering from smart grid perspective. In Proceedings of the a Two-Day Conference on Flexible Electronics for Electric Vehicles, Jaipur, India, 5–6 March 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Malciak, M.; Nowakowska, P. Zmiany w Funkcjonowaniu i Zasadach Rozliczania Fotowoltaika. Nowa Energy 2021, 5–6, 81. [Google Scholar]

- Mój Prąd 6.0 Subsidy Programme. Available online: https://mojprad.gov.pl/ (accessed on 11 June 2025).

- Luthander, R.; Widén, J.; Nilsson, D.; Palm, J. Photovoltaic self-consumption in buildings: A review. Appl. Energy 2015, 142, 80–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moshövel, J.; Kairies, K.; Magnor, D.; Leuthold, M.; Bost, M.; Gährs, S.; Szczechowicz, E.; Cramer, M.; Sauer, D.U. Analysis of the maximal possible grid relief from PV-peak-power impacts by using storage systems for increased self-consumption. Appl. Energy 2015, 137, 567–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villar, C.H.; Neves, D.; Silva, C.A. Solar PV self-consumption: An analysis of influencing indicators in the Portuguese context. Energy Strategy Rev. 2017, 18, 224–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertsch, V.; Geldermann, J.; Lühn, T. What drives the profitability of household PV investments, self-consumption and self-sufficiency? Appl. Energy 2017, 204, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barzegkar-Ntovom, G.A.; Chatzigeorgiou, N.G.; Nousdilis, A.I.; Vomva, S.A.; Kryonidis, G.C.; Kontis, E.O.; Georghiou, G.E.; Christoforidis, G.C.; Papagiannis, G.K. Assessing the viability of battery energy storage systems coupled with photovoltaics under a pure self-consumption scheme. Renew. Energy 2020, 152, 1302–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Rodríguez, F.J.; Jiménez-Castillo, G.; de la Casa Hernández, J.; Aguilar Pena, J.D. A new tool to Analysing photovoltaic self-consumption systems with batteries. Renew. Energy 2021, 168, 1327–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Morán, C.; Arboleya, P.; Pilli, V. Photovoltaic self consumption analysis in a European low voltage feeder. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2021, 194, 107087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ordóñez, Á.; Sánchez, E.; Rozas, L.; García, R.; Parra-Domínguez, J. Net-metering and net-billing in photovoltaic self-consumption: The cases of Ecuador and Spain. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2022, 53, 102434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cieślak, K.J. Multivariant Analysis of Photovoltaic Performance with Consideration of Self-Consumption. Energies 2022, 15, 6732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reibsch, R.; Blechinger, P.; Kowal, J. The importance of battery storage systems in reducing grid issues in sector-coupled and renewable low-voltage grids. J. Energy Storage 2023, 72, 108726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cieślak, K.J. Profitability Analysis of a Prosumer Photovoltaic Installation in Light of Changing Electricity Billing Regulations in Poland. Energies 2024, 17, 3618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozporządzenie Ministra Klimatu i Środowiska z dnia 22 marca 2023 r. w sprawie szczegółowych warunków funkcjonowania systemu elektroenergetycznego. Regulation of the Minister of Climate and Environment of 22 March 2023 on Detailed Conditions for the Operation of the Power System. Dz.U. 2023 poz. 819. Available online: https://dziennikustaw.gov.pl/DU/2023/819 (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- Sharma, V.; Haque, M.H.; Aziz, S.M.; Kauschke, T. Reducing Overvoltage-Induced PV Curtailment through Reactive Power Support of Battery and Smart PV Inverters. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 123995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Parliament and Council of the European Union. Directive 2009/28/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 23 April 2009 on the Promotion of the Use of Energy from Renewable Sources and Amending and Subsequently Repealing Directives 2001/77/EC and 2003/30/EC. Off. J. Eur. Union 2009, L140, 16–62. [Google Scholar]

- European Parliament and Council of the European Union. Directive (EU) 2018/2001 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 11 December 2018 on the Promotion of the Use of Energy from Renewable Sources (Recast). Off. J. Eur. Union 2018, L328, 82–209. [Google Scholar]

- European Parliament and Council of the European Union. Directive (EU) 2023/2413 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 18 October 2023 amending Directive (EU) 2018/2001, Regulation (EU) 2018/1999 and Directive 98/70/EC as regards the promotion of energy from renewable sources, and repealing Council Directive (EU) 2015/652. Off. J. Eur. Union 2023, L 2413, 1–77. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Fit for 55: Delivering the EU’s 2030 Climate Target on the Way to Climate Neutrality; Communication from the Commission, COM (2021) 550 Final; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Jończy, R.; Śleszyński, P.; Dolińska, A.; Ptak, M.; Rokitowska-Malcher, J.; Rokita-Poskart, D. Environmental and Economic Factors of Migration from Urban to Rural Areas: Evidence from Poland. Energies 2021, 14, 8467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonanzas-Torres, F.; Urraca, R.; Polo, J.; Perpiñán-Lamigueiro, O.; Escobar, R. Clear sky solar irradiance models: A review of seventy models. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2019, 107, 374–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, Q.; Siauw, T.; Bayen, A.M. Chapter 17—Interpolation. In Python Programming and Numerical Methods; Kong, Q., Siauw, T., Bayen, A.M., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2021; pp. 295–313. [Google Scholar]

- Pijarski, P.; Kacejko, P.; Wancerz, M. Voltage Control in MV Network with Distributed Generation-Possibilities of Real Quality Enhancement. Energies 2022, 14, 2081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Requirements and Procedures for the Connection of Energy Generation Units to the Power Grid. TAURON Dystrybucja S.A. Available online: https://www.tauron-dystrybucja.pl/przylaczenie-do-sieci/przylaczenie/mikroinstalacja (accessed on 31 August 2025).

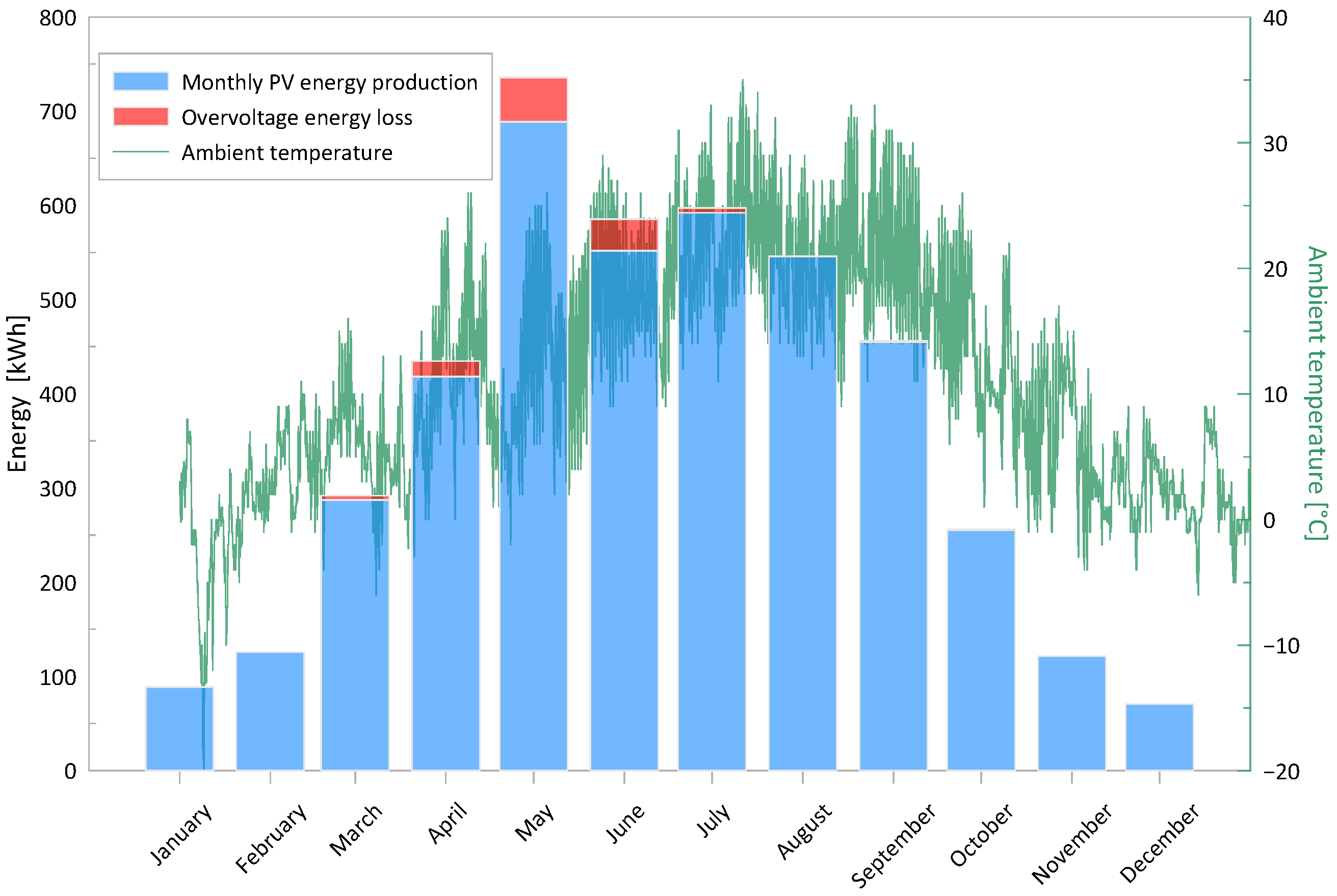

| Month | Number of Days with Overvoltage Power Drops | PV Energy Generation [kWh] | Energy Losses [kWh] | Percentage Loss |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| January | 0 | 89 | 0 | 0.00% |

| February | 1 | 126 | 0.125 | 0.10% |

| March | 4 | 287 | 4.52 | 1.57% |

| April | 13 | 418 | 16.55 | 3.96% |

| May | 26 | 689 | 47.1 | 6.84% |

| June | 20 | 552 | 33.6 | 6.1% |

| July | 8 | 592 | 5.1 | 0.86% |

| August | 2 | 546 | 0.25 | 0.05% |

| September | 2 | 455 | 1.45 | 0.32% |

| October | 1 | 255 | 0.4 | 0.16% |

| November | 0 | 121 | 0 | 0.00% |

| December | 0 | 70 | 0 | 0.00% |

| Annual total for 2024 | 78 | 4200 | 109 | 2.6% |

| Method for Limiting Voltage Overruns | DSO Investment Cost | Difficulty of Implementation | Power Losses in the Grid | Reduction in Energy Production | Effectiveness of the Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LV grids modernization | large | high | reduced | minor or nonexistent | good |

| Transformer with on-load tap changer | large | high | unchanged | minor or nonexistent | good |

| Reactive power regulation | none | low | increased | minor or nonexistent | medium, depends on the type of grid and power of PV installations |

| Active power limitation | none | low | reduced | medium or low | good |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cieslak, K.J.; Adamek, S. Overvoltage Challenges in Residential PV Systems in Poland: Annual Loss Assessment and Mitigation Strategies. Energies 2025, 18, 6247. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236247

Cieslak KJ, Adamek S. Overvoltage Challenges in Residential PV Systems in Poland: Annual Loss Assessment and Mitigation Strategies. Energies. 2025; 18(23):6247. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236247

Chicago/Turabian StyleCieslak, Krystian Janusz, and Sylwester Adamek. 2025. "Overvoltage Challenges in Residential PV Systems in Poland: Annual Loss Assessment and Mitigation Strategies" Energies 18, no. 23: 6247. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236247

APA StyleCieslak, K. J., & Adamek, S. (2025). Overvoltage Challenges in Residential PV Systems in Poland: Annual Loss Assessment and Mitigation Strategies. Energies, 18(23), 6247. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236247