Abstract

Distributed energy resources provide local power as a supplement on the customer side. Recent rapid development of the distributed energy source enhances the clear energy production at the terminal of the power system. Whereas the small capacity of a single distributed energy source and the scaling of numbers pose difficulties for market design and clearance. In addition, the stochastic and quickly varying output power of the amount of (distributed) renewable energy sources increases the necessity for flexible regulation capacities. In response to the above issues, this paper develops a modified Leiden algorithm to aggregate distributed energy sources with similar regulation properties and connectives, avoiding complex power allocation strategies within the intra-aggregator and ensuring ordered power flow among inter-aggregators. Then, a bi-level market mechanism is proposed to highlight the regulation contributions of both distributed aggregators and conventional energy sources. The upper-level model optimizes the price of combined frequency regulation and electricity markets. The lower-level model regulates the output power of the aggregators and conventional energy sources. Furthermore, the modification of the bi-level model is proposed via the Karush–Kuhn–Tucker condition to ensure its solvability. The proposed market mechanism and the aggregating method are verified using a modified IEEE 30-bus system with IEEE 123-node test feeders and terminal-side energy resources. The results reflect the incentive impacts of the designed market mechanism and the effectiveness of the aggregating algorithm.

1. Introduction

In the global push toward energy transition and low-carbon practices, the widespread integration of distributed energy resources (DERs) like solar photovoltaics, energy storage, and wind power into distribution networks appears to have significantly reshaped how power grids traditionally operate [1]. However, rapid DER growth, with its intermittent output power, introduces scale, temporal coupling, and dimensionality into management and trading problems. Advanced methodological frameworks are therefore required to address intermittency and spatial heterogeneity while ensuring efficient coordination.

The proliferation of DERs in distribution networks introduces substantial operational and transactional challenges. Rapid deployment transforms traditionally radial, unidirectional feeders into circuits with frequent bidirectional, highly variable power flows, making their management complex due to these power flow constraints. The small individual capacity of a single DER unit leads to its flexibility being ignored in conventional dispatch, pricing, and settlement processes. DERs are widely distributed across the distribution network and exhibit significant volatility. For example, photovoltaics generate a large amount of electricity during lunchtime and are shut down at night, which may lead to local supply-demand imbalances in the power grid, distort the locational marginal price(LMP) [2], break the accuracy of market price signals [3], and weaken the economic efficiency of the electricity market [4]. However, because a single DER has a limited capacity, it can’t meet the demand for the “minimum trading unit” in the energy market. Therefore, dispersed DERs within a given area can be aggregated into a single aggregator to participate in the market. This will significantly reduce the number of units participating in the market, simplify scheduling, and provide auxiliary services such as frequency regulation and backup to the power grid, thereby enhancing economic value.

The aggregation of DERs has multiple advantages: firstly, it improves the consumption rate of renewable energy in the region [5], reduces carbon emissions, utilizes energy storage to absorb power output, and reduces abandoned electricity; the second is to enhance the flexibility of the power grid, reduce the impact on the main grid through energy storage charging and discharging, provide fast frequency regulation services for the power grid, replace fossil energy peak shaving units, and quickly respond to the flexibility adjustment needs of the power grid; the third is to enhance market liquidity [6]. DERs lower their market entry barriers through aggregation, and DER owners can earn profits by selling excess electricity and providing flexible services, and increase investment returns through diversified market participation. Aggregators provide services at prices closer to marginal costs, and their competitive combination bidding will lower wholesale electricity prices, thereby reducing overall power system expenditures.

Aggregating DERs in the distribution networks can be approached from multiple perspectives. The basic method is to consider the spatial distribution and partition the network according to the degree of electrical coupling between nodes in order to reduce cross-regional power transmission losses [7] and avoid blind aggregation from burdening the power grid. The existing network partitioning methods usually consider factors such as power grid topology [8], line impedance, and energy supply and demand balance [9]. The mainstream network partitioning algorithms include clustering algorithms, optimization algorithms, and community detection algorithms [10]. On this basis, it is necessary to consider the resource operation characteristics such as energy storage capacity and photovoltaic output curve of DERs in different aggregation scenarios [11]. For example, small-capacity energy storage participates in aggregation, while large-capacity energy storage participates directly in the auxiliary service market [12]. Different DERs during peak output periods cannot be forcibly integrated, and the aggregated aggregators prioritize internal power balance [13]. Therefore, by considering the operational characteristics of DER resources, the aggregation method of network partitioning can lay a good foundation for subsequent aggregator participation in market transactions.

After completing the aggregation, the aggregator integrates and coordinates the total capacity of DERs, participates in the bidding of the electricity wholesale market and auxiliary service market, and thus connects to the multi-market pricing framework [14]. This pricing framework usually covers the energy market, capacity market, frequency regulation market, and rotating reserve market, and the clearing price of each market will reflect the real-time supply and demand situation and the node marginal electricity price structure. The aggregation mode can help small and heterogeneous DER owners meet the market’s requirements for “minimum bidding capacity, real-time monitoring output, and rapid regulation”, thereby reducing market entry barriers and unleashing the collective value of DERs as flexible and responsive assets [15]. Aggregators integrate the capacity and time flexibility of DERs, submit collaborative bidding schemes, and achieve collaborative optimization of “energy supply, electricity price arbitrage, peak shaving and valley filling, and auxiliary service provision”, aligning scheduling strategies with market signals and improving resource allocation efficiency [16].

The trading mechanisms for DER aggregators should take into account the different output patterns and control abilities of various resources [17]. Recent research has made progress in improving market design. Bi-level optimization models help better utilize aggregated flexibility by coordinating controllable loads [18]. Combining PV and energy storage within a single optimization framework enables better time-shifting, reduces imbalance risks, and increases participation in ancillary service markets [19,20]. However, in pricing mechanisms, fluctuations in renewable energy can cause prices to exceed the price cap, reducing pricing efficiency [21]. To solve this problem, extended price signal methods have been proposed to provide stronger economic guidance [22,23]. These improved signals support clearing-based pricing models that optimize payments for both energy and ancillary services [24,25]. Therefore, it is necessary to use appropriate price signals to guide aggregators to actively participate in market operations and help maintain the stable operation of the power system.

Motivated by the discussion above, this paper presents an aggregating approach for DERs that considers characteristic similarity and topological connections to ensure the internal connectivity of DERs within each aggregator. Based on the resulting electrically coherent aggregators, a joint market-clearing strategy is developed, which applies price signals to each aggregator to improve the utilization of flexible DERs. The main contributions of this work are as follows.

- A modified Leiden algorithm is extended with capabilities for regulating distributed energy sources to aggregate similar energy sources in a connected distribution network.

- A combined frequency regulation and electricity market is designed for aggregated distributed energy sources.

- A pricing mechanism that couples scheduling and settlement through capability-linked price factors, supporting efficient allocation and incentive alignment.

2. Principles of Operation

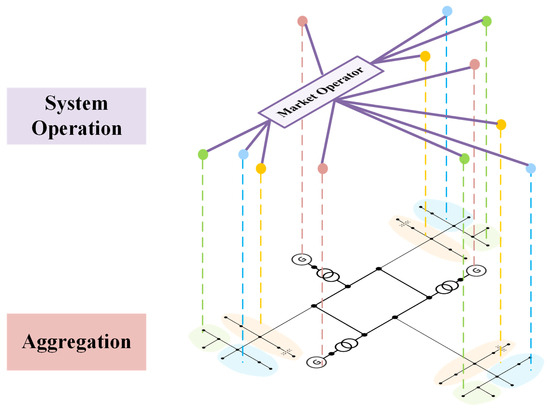

The proposed incentive mechanism for DER aggregators in joint markets in this paper comprises two stages: aggregating and transacting. The aggregating approach is based on resource characteristics and topology structure. Then, based on the aggregated DERs, the joint market-clearing method and bilevel pricing model are proposed for both the aggregated DER groups and units. The total framework of the article is shown in the Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Proposed DER aggregation and transaction framework. The different colored regions indicate the aggregated DER groups. DERs are aggregated into electrically coherent groups, after which an incentive-based transaction mechanism coordinates market participation at both aggregator and individual unit levels.

The proposed incentive mechanism operates in two stages: (i) DERs aggregating and (ii) market transacting. The aggregating stage constructs electrically coherent DER aggregators by jointly considering resource attributes and network topology. Using the aggregated aggregators, a joint market-clearing model and a bilevel pricing mechanism are then formulated to co-optimize dispatch and remuneration for both aggregators and individual units. The overall framework is shown in Figure 1.

The aggregating approach takes the following perspectives into account. First, DER characteristics and similarities between DERs are considered. To capture DER heterogeneity while promoting intra-aggregator resource complementarity, an attribute-based aggregation step classifies nodes according to DER characteristics: PV output profile, storage power/energy capacity, yielding a quantitative similarity measure between node pairs. In parallel, the electrical distance is implemented for the partitioning. Nodal voltage sensitivities are derived from the power flow Jacobian and used to quantify electrical distance via impedance-based propagation of voltage responses. Functional similarity and electrical distance are combined to form a weighted graph that captures both resource correlations and structural connections. Taking the modularity of this weighted graph as the optimization objective, the Leiden algorithm is employed to generate connectivity-preserving aggregators and to get a partition that effectively balances resource complementarity with structural consistency.

The aggregated aggregators and conventional generating units submit bid prices and quantities for both products to participate in the market. The cleared quantities of dispatch energy and regulation capacity are obtained through a joint unit commitment and economic dispatch model. A bilevel pricing model is then applied: the upper layer treats the clearing prices as decision variables, optimizing them within operational constraints to ensure economic consistency in price formation, while the lower layer represents the profit-maximizing behavior of market participants under these prices. The final market-clearing results include the cleared quantities and corresponding prices for energy and regulation capacity, both consistent with system and market constraints.

3. Aggregating Based on Similarities and Connectivity

By aggregating DERs with similar characteristics, the number of direct market participants can be effectively reduced, simplifying the organization and operation of joint market transactions. Similarity-based aggregating enhances the predictability of aggregated outputs and ensures a more coordinated response to dispatch instructions, thereby improving system feasibility and overall economic performance.

The primary purpose of aggregating DERs is to reduce the spatial and computational dimensionality of operational optimization and market-clearing problems. Ensuring that DERs within the same aggregator exhibit similar operational characteristics increases forecast accuracy for aggregated output power and improves the coherence of their response to clearing results. Thus, attribute similarity is explicitly incorporated into the aggregating process.

For PV units, grouping with similar capacity scale and normalized output profiles enables the use of a common scaling factor to represent aggregate real-time power, e.g., , where is rated capacity and the normalized forecast profile. Homogeneity reduces intra-aggregator forecast dispersion, simplifies bidding, and supports tighter confidence intervals for probabilistic offers.

For energy storage systems, similar power and energy ratings mitigate state-of-charge divergence under heterogeneous charging/discharging instructions and reduce equalization (circulating) currents that otherwise induce avoidable losses. An aggregator-level balanced state-of-charge policy can therefore be enforced with lower internal rebalancing overhead [26] When stochastic net-load shifts cause temporary SoC imbalance, size homogeneity limits corrective transfer magnitudes and associated degradation.

Demand response resources follow analogous principles: aggregating loads with comparable reduction potential, activation duration, and rebound characteristics yields a more controllable aggregate “virtual battery” (single-direction discharge), improving baseline estimation and reducing performance risk.

Consequently, PV shape similarity, ESS energy/power ratio alignment, and demand response flexibility profile similarity are jointly considered as attribute features in the aggregation and partitioning stage to enhance predictability, controllability, and market compliance.

To ensure the similarity of the aggregated DERs, the operation characteristics of DERs are considered: Historical data on DERs, such as PV output curves, charging and discharging power curves for energy storage, and energy storage capacity, are selected as functional indicators for aggregation. After normalization of the characteristics separately, similarity measures are used to ensure resource balance across different aggregators. At the same time, combined with network topology and sensitivity structural indicators, the network is transformed into a weight map that combines structural and functional characteristics.

3.1. DERs Characteristics and Similarity Indicators

For the i-th DER in the distribution network, define its attribute vector as follows:

where , ,…, respectively, represent the n different characteristics of i-th DER.

Using the attribute weight matrix D, whose diagonal entries encode feature importance, with larger values assigning greater influence on similarity, the attribute similarity between nodes i and j is defined as follows:

where is the weight of PVs; is the weight of the energy storage system; is the weight of the flexible load; and D is the complete weight matrix.

3.2. Network Topology and Sensitivity Structural Indicators

The electrical distance between nodes distributed with DERs reflects their spatial distribution and electrical connectivity, indicating the effects of a power injection on the voltage at each node. Accordingly, nodal voltage–power sensitivities are incorporated into the aggregation process. Based on the power flow equations, the relationship between incremental changes in voltage angle/magnitude at node i and active/reactive power injections at node j can be written as follows:

where represents the change in active and reactive power injected at the node j; , represents the change in phase angle and voltage amplitude of the node i; J is the Jacobian matrix, , , , represents the relationship between the change in node power and the voltage vector of the node.

The sensitivity matrix of node voltage to node active/reactive power can be expressed as follows:

where denotes the voltage magnitude at node i; and are the active and reactive power injections at node j; is the rated network voltage; and are the cumulative resistance and reactance, respectively, along the branch path set between nodes i and j.

In distribution networks, the ratio typically approaches 1 [27]. Thus, using the sensitivity matrix, the electrical distance between nodes i and j is derived from both resistance and reactance along their connecting path. For tractability, reactance is adopted here as the structural indicator:

3.3. The Leiden Algorithm Based on the Modularity Index

The Leiden algorithm is adopted and modified to guarantee connectivity among DERs within the same aggregator and to avoid fragmented or weakly connected aggregators. In this study, DER attribute similarity and the sensitivity–based structural metric are embedded into the algorithm to obtain electrically coherent aggregation results.

Thus, a composite inter-node distance that integrates (i) structural (electrical) distance derived from network topology and voltage–power sensitivities and (ii) functional similarity based on DER operational attributes and storage capacity. This composite metric forms the weighted edge set used in subsequent aggregation.

where functions as an intentional hyperparameter to control the relative importance of functional similarity versus structural closeness.

The additive combination of electrical structure and functional attributes in this composite edge weight is highlighted by two main prerequisites: directional consistency and scalar comparability. Firstly, the objective of the community detection algorithm is to find the most cohesive groups. Both the ‘electrical distance’ and ‘functional attribute difference’ metrics are transformed into ‘closeness scores’. This ensures that both the electrical and functional components with higher scores uniformly represent stronger connections and a greater tendency to cluster within the same community. Consequently, both components are perfectly aligned with the same optimization objective. Secondly, prior to calculating these ‘closeness scores’, all raw data (including electrical impedance, PV capacity, and battery energy storage capacity) undergo a pre-normalization process, scaled to a uniform numerical range. This step ensures the two resulting scores are numerically comparable (commensurate) and prevents a scenario in which one feature metric might dominate the other simply because of a difference in orders of magnitude. Establishing both directional consistency and scalar comparability provides a robust justification for this additive formulation. The weighting parameter is employed not merely as a normalization factor but also as a strategic hyperparameter to systematically modulate the relative importance of functional similarity and structural closeness in the final optimization objective.

Implementing the composite distance , an extended weighted modularity metric is defined to accommodate aggregators with heterogeneous internal densities. This metric serves as the optimization objective for the modified Leiden algorithm, which preserves connectivity and avoids weakly linked or fragmented aggregations. The extended modularity is given by the following:

where is the extended modularity index; m is the sum of all edge weights in the distribution network, ; is a resolution parameter that adjusts the density of the connection within and between aggregators. When , smaller and tightly connected groups will be formed, and when , larger, but relatively less tightly connected groups will be formed. , is the sum of all edge weights connected to node i and node j in the distribution network, ; when node i and node j are in the same aggregator, , otherwise .

Greater reverse power flow intensity increases power volatility and the probability and magnitude of feeder backfeed events. This elevates dependence on inter-aggregator power exchange, weakens intra-aggregator self-balancing, and effectively lowers internal connection density. Consequently, finer granularity (a larger number of aggregators) is preferred, implying an increase in the resolution parameter .

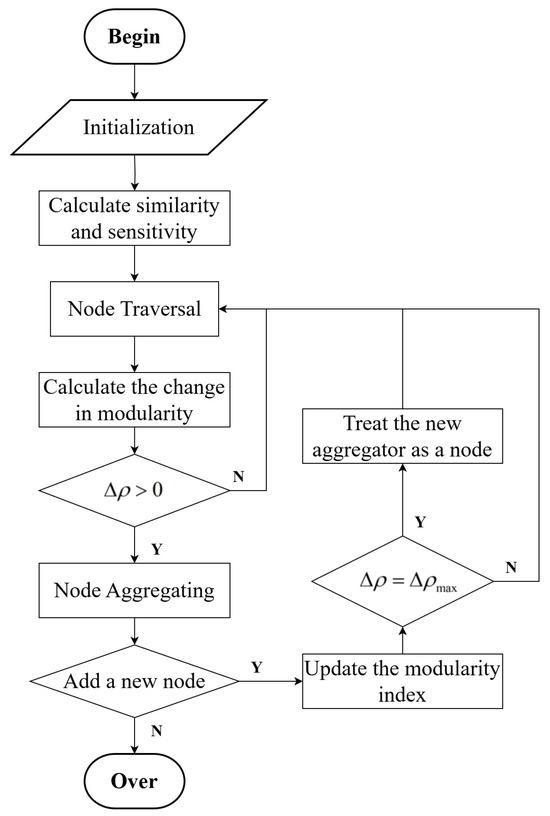

The modularity partitioning process is shown in the Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Modularity partitioning process of the modified Leiden algorithm with DERs characteristics, sensitive matrix of distribution network, and similarities.

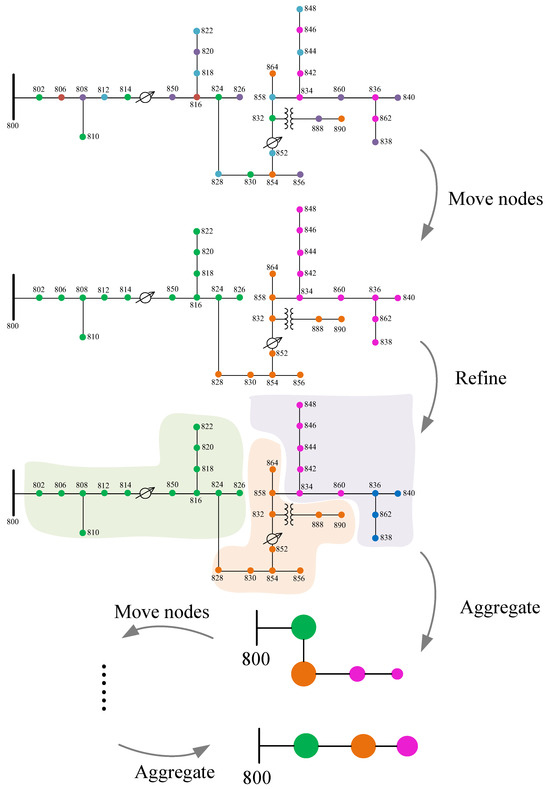

The Leiden algorithm starts with singleton partitioning, where each node is in its own aggregator. The algorithm iteration consists of three stages, as shown in Figure 3 and Algorithm 1.

Figure 3.

Illustration of the procedure for aggregating DERs in a distribution network using the modified Leiden algorithm.

- (1)

- Initialization and local movement: All nodes are placed in a queue in random order. Each node is examined sequentially; its modularity gain is evaluated for moves to candidate (typically adjacent) communities. The node is reassigned to the community yielding the largest positive modularity gain; if no positive gain exists, it remains in its current community. After one full pass, an interim partition is obtained.

- (2)

- Refinement: Each community in is refined to ensure internal connectivity; weakly connected or disconnected parts are split. Nodes (or refined subcommunities) may merge with alternative communities if this further increases modularity, with controlled randomness broadening the search space. After the refinement phase, the communities in are usually split into multiple optimized communities .

- (3)

- Aggregation: The algorithm continues to move the aggregated network nodes to obtain . At this point, aggregator optimization will no longer improve the partitioning results. After completing the third stage, the procedure iterates until modularity convergence.

Compared with the Louvain method, the Leiden algorithm prevents poorly connected or fragmented communities, guaranteeing internally coherent aggregators. By embedding electrical (sensitivity-based) distance and DER attribute similarity into the weighted modularity formulation, the modified approach more accurately captures both structural coupling and functional affinity, yielding electrically coherent, operationally meaningful aggregation results.

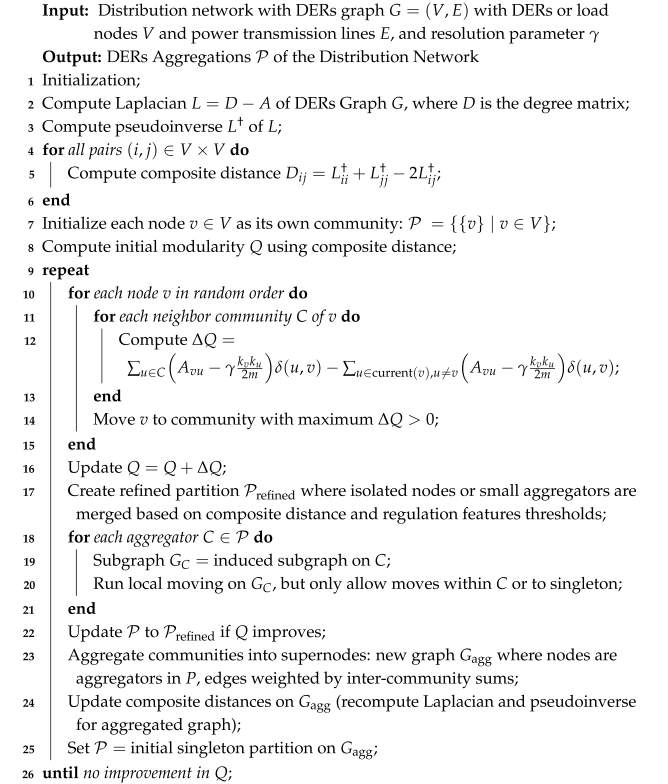

| Algorithm 1: Leiden Algorithm based DERs Aggregation Approach with Composite Distance-Based Modularity |

|

4. Joint Market Economic Dispatch Model with DER Aggregators

DERs are typically characterized by small individual capacities, large quantities, and wide spatial dispersion, which make it challenging for individual units to follow grid dispatch instructions. By employing the aforementioned aggregation approach, individual DERs can be integrated into an aggregator that can interface with the automatic generation control system, receive dispatch signals from the grid, and thereby become eligible to participate in the frequency regulation ancillary service market. Building on this, this paper develops a co-optimized market-clearing model for energy and frequency regulation ancillary services with aggregator participation, enabling market participants to submit simultaneous bids for both energy and regulation capacity, thereby facilitating coordinated clearing across the two markets.

The objective function of the joint clearing model is to minimize the total cost of procuring energy and frequency regulation ancillary services:

where, denotes the bidding function of the unit i at time t; denotes the bidding function of the aggregator i at time t; denotes the cleared power output of unit i at time t; denotes the cleared regulation capacity of the unit i at time t; denotes the cleared power output of the aggregator i at time t; denotes the regulation capacity of the aggregator i at time t; T denotes the total scheduling periods; denotes the total number of units; denotes the total number of aggregators.

The constraints that generating units must satisfy include power output limits, regulation capacity limits, and ramping rate limits:

where and denote the upper and lower output limits of unit i, respectively; denotes the maximum regulation capacity that unit i can bid at time t; and / denote the upper and lower ramping limits of unit i, respectively.

The total power output and regulation capacity of an aggregator are jointly provided by its internal PV and energy storage systems:

where denotes the PV output of the aggregator i at time t; and denote the charging and discharging power of the energy storage within the aggregator i, respectively; denotes the regulation capacity provided by the PV within the aggregator i at time t; and denotes the regulation capacity provided by the energy storage within the aggregator i at time t.

The constraints within the PV units of the aggregator i include the following:

where, for aggregator i at time t, and denote the upper and lower limits of PV output, respectively; and denotes the upper limit of regulation capacity provided by the PV.

The energy storage within the aggregator i is subject to capacity constraints and power output limits:

where is the maximum charging or discharging power of the storage in the aggregator i; denotes the charging/discharging status of the energy storage determined by the unit commitment. A value of 1 indicates charging; and are its upper and lower energy storage limits; is the charge/discharge efficiency; is the stored energy at time t; represents the length of the time interval; and is the maximum regulation capacity the storage can provide.

From the system perspective, power supply and demand should be balanced while satisfying the corresponding regulation capacity requirements [19,28]:

where denotes the load at time t, denotes the total number of loads, and denotes the system regulation capacity requirement at time t.

For each transmission line l, the power flow at time t should not exceed its capacity limit and :

where, , , and represent the generation shift distribution factors of units, aggregators, and loads on the branch l at time t, respectively.

5. Bilevel Pricing Model

Aggregation can concentrate substantial highly penetrated DER capacity within a single aggregator, creating upward pressure on market prices and risking violations of admissible operating bounds. To mitigate this, energy and regulation prices are treated as bounded decision variables, and a bilevel pricing framework is introduced. The proposed pricing model includes two stages: the dispatch and pricing procedure. Firstly, unit commitment and economic dispatch determine the unit’s operation states and cleared energy schedules purely based on operational constraints and cost minimization. Then, the pricing model is implemented using the dispatched results and cleared schedules as inputs to optimize the corresponding energy and regulation prices. At the upper level, market participants, generating units and aggregators, maximize profit subject to their technical constraints under the posted prices. At the lower level, the market operator determines prices within the specified upper limits to meet system demand and regulation requirements while minimizing the overall opportunity cost. For tractability, energy prices do not include an explicit congestion component in this formulation.

The objective function of the first-level model is formulated as follows:

where denotes the maximum net profit of the unit i under the given price; denotes the maximum net profit of the aggregator i under the given price, represents the system marginal electricity price, and represents the regulation capacity price.

The constraints of this level are the same as those in the joint market-clearing model.

The objective function of the lower-level model is as follows:

where and denote the revenues of the unit i and aggregator i respectively, obtained under the joint clearing model with price variables. The superscript indicates the values derived from the dispatch results of the joint clearing model.

To meet the practical requirements of market operation, a price cap constraint is introduced as follows:

where and denote the upper and lower bounds of the energy price, while and denote the upper and lower bounds of the regulation capacity price, respectively.

A uniform system marginal price is adopted to reflect the machines and principles of operation for the market with the aggregator of distributed renewable energy sources. All power transmission constraints are enforced during the network-constrained economic dispatch model, ensuring that congestion issues are fully resolved. Consequently, the pricing model operates based on the feasible dispatch result. Thus, for the market with distributed prosumers and flexible resources coordinated by aggregators, the proposed pricing method provides transparent, system-wide incentive signals without requiring nodal price granularity.

In the upper-level model, cleared energy and regulation capacities are decision variables; in the lower-level model, energy and regulation prices are the decision variables. This coupling renders the bilevel problem intractable for direct solution. Applying the Karush–Kuhn–Tucker (KKT) optimality conditions to the lower level, price-setting, converts it into a set of complementarity constraints, which—once embedded in the upper level—yield a single equivalent mathematical program that can be solved directly.

6. Result

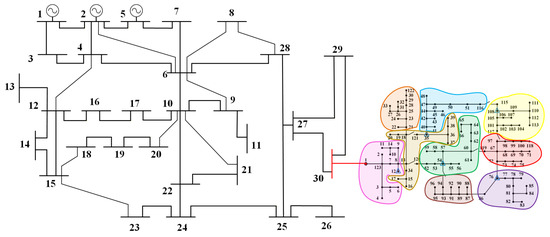

The proposed aggregating approach and bilevel pricing model are verified using a modified IEEE 30-bus power system with 3 generation units and distributed across modified IEEE 123-node test feeders at bus 30. Figure 4 illustrates the test system topology. The load profiles are shown in Figure 5a.

Figure 4.

The complete topology for DERs aggregating and market-clearing test.

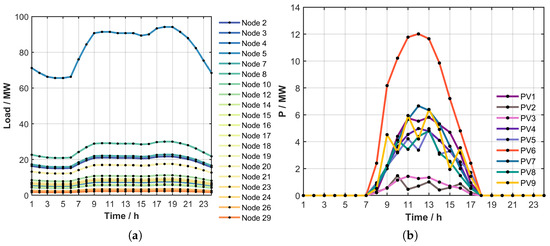

Figure 5.

Original data: (a) the total load within the system; (b) the combined profiles of PV within the system.

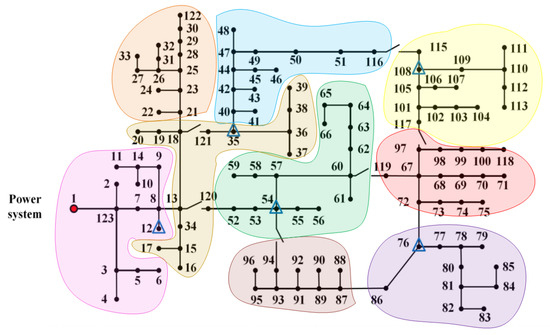

6.1. The DER Aggregating Results via the Modified Leiden Algorithm

The proposed partitioning method was evaluated on the IEEE 123-node test feeder using a resolution parameter of . The modified Leiden algorithm produced nine non-overlapping microgrid aggregators exhibiting strong internal coupling, high intra-aggregator attribute similarity, and clearly defined inter-aggregator boundaries. These results demonstrate that the Leiden algorithm, as a modularity-based community detection method, yields well-connected, electrically coherent partitions consistent with the underlying power flow structure, thereby supporting stable system operation.

The benefit of the modified Leiden algorithm is shown in Table 1 by comparing with Louvain and with a topology-only partition. The comparison data, evaluated using the specified metrics: modularity, size variance, and attribute variance (as a proxy for downstream operational performance), clearly demonstrate the advantages of the proposed method.

Table 1.

Performance comparison of Leiden and Louvain algorithms under different weighting schemes.

As shown in the table, the Leiden Composite method produces significantly lower community-size variance than the Louvain Composite method. This empirically confirms that the Leiden algorithm produces a more stable, balanced partition, which is critical for practical grid management applications where extremely large or extremely small zones are undesirable. Besides, the Leiden-Composite method successfully achieves its primary objective, significantly reducing the variance for both PV and battery. This demonstrates that the modified method creates functionally superior communities that are more homogenous in their DER capacity. The data confirms that the modified method leverages the strengths of the Leiden algorithm to produce more balanced partitions than Louvain and to successfully produce functionally cohesive communities with superior attribute homogeneity, while maintaining a high-quality modularity score.

The spatial distribution of partitioned DERs is shown in the Figure 6. The combined profiles of PV and energy storage systems are shown in Table 2 and Figure 5b.

Figure 6.

Aggregating for DERs. All DERs are aggregated into nine groups, indexed by the different-colored areas.

Table 2.

Internal data of aggregators after aggregation.

The total capacity of PV and energy storage within aggregators after aggregation is shown in Table 2.

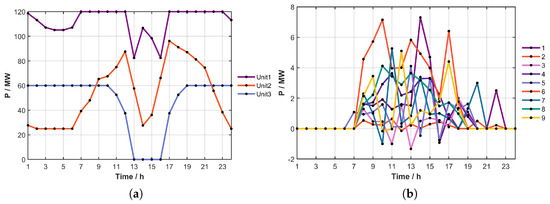

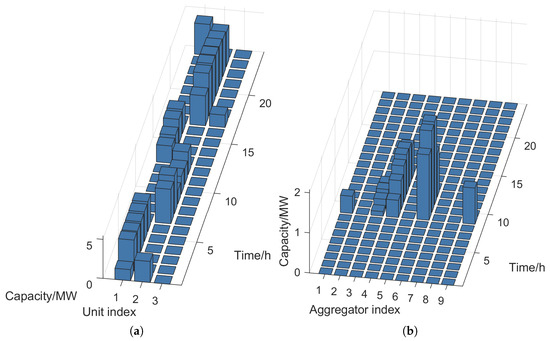

6.2. Market Clearing Result

Figure 7 demonstrates the cleared energy outputs under the proposed bilevel pricing framework. The co-optimized market-clearing mechanism adapts to temporal variations in system load and DER production, enabling aggregated DER portfolios to compete as single bidding entities. Coordination between PV and storage within each aggregator increases local PV utilization and smooths net power injections. The corresponding frequency regulation awards are shown in Figure 8. Conventional generating units receive the dominant share of regulation capacity, reflecting their higher assured ramping capability and availability. Regulation awards to aggregators are concentrated in a few aggregators with comparatively larger or more responsive storage, while the remaining aggregators obtain limited or no capacity in most intervals. Overall, aggregators function as complementary frequency resources, contributing opportunistically during periods of elevated variability or ramping demand rather than displacing traditional units.

Figure 7.

Clearing results of awarded power: (a) awarded power of generating units; (b) awarded power of aggregators. Positive values indicate that the aggregator is delivering power outward.

Figure 8.

Awarded frequency regulation capacity: (a) awarded capacity of generating units; (b) awarded capacity of aggregators.

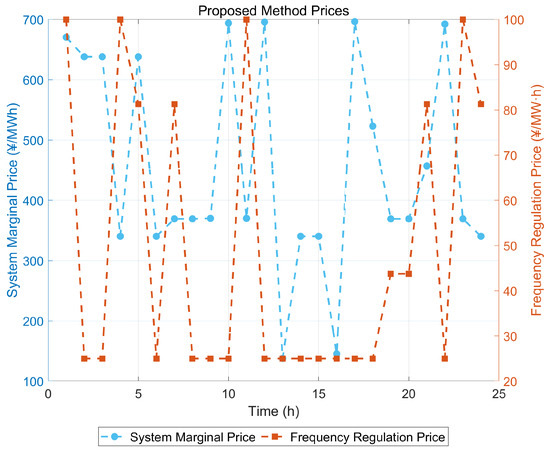

6.3. Comparison

By implementing the proposed pricing model, dispatch and price formation are co-determined in a unified optimization, satisfying market operational requirements. As shown in Figure 9, the model directly produces the system marginal energy price and the regulation capacity price. Imposed price bounds ensure feasibility, and all clearing prices remain within the admissible operating range.

Figure 9.

Price curve of proposed pricing scheme.

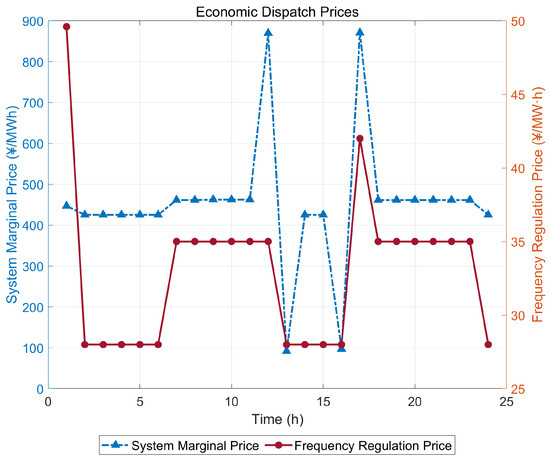

Compared with traditional economic dispatch in Figure 10, the proposed pricing framework significantly improves price stability in system marginal price and reveals the temporal variability in frequency regulation prices. The proposed method avoids extreme spikes in system marginal prices and provides dynamic frequency prices that better reflect the system’s flexibility requirements.

Figure 10.

Price curve of economic dispatch.

7. Conclusions

This paper presents an integrated framework for aggregator participation in electricity markets. An aggregating approach that jointly exploits grid topology and DER attribute similarity forms electrically coherent aggregators as the analytical foundation. On this basis, a joint energy–frequency regulation clearing model is established to co-optimize dispatch energy and regulation capacity, achieving flexible scheduling and maximizing aggregated profits. The bilevel pricing model introduces price variables directly into the clearing process, coupling scheduling and settlement to obtain consistent energy and regulation prices within predefined operational limits. This framework enables DERs to collectively meet market entry requirements, supports their compliant participation in energy and ancillary service markets, improves economic efficiency while adhering to system constraints, and provides a scalable development pathway for aggregators.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.H. and Z.L.; methodology, X.H. and Z.L.; software, Z.L. and J.S.; validation, X.H., Z.L. and B.L.; formal analysis, Z.L. and J.S.; writing—original draft preparation, B.L. and H.L.; writing—review and editing, X.H. and Y.G.; visualization, Y.G.; project administration, X.H. and H.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by State Grid Jiangsu Electric Power Co., Ltd., Economic Research Institute with grant number SGJSJY00GHJS2500147.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Xiaoyan Hu, Zesen Li, Jing Shi, Bingjie Li, Yi Ge and Hu Li were employed by the company State Grid Jiangsu Electric Power Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. The authors declare that this study received funding from State Grid Jiangsu Electric Power Co., Ltd. The funder was not involved in the study design, collection, analysis, interpretation of data, the writing of this article or the decision to submit it for publication.

References

- Hao, Y.; Khan, I. Impact of decarbonization enablers, energy supply between transition and disruption, on renewable energy development. Energy 2025, 324, 135863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Wang, X.; Chen, C.; Lu, Z.; Wang, X. Enhancing Distribution System Resilience with Peer-to-Peer Transactions. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2025, 40, 907–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Xiang, Y.; Gu, C.; Sun, W.; Wei, X.; Cheng, S.; Liu, J. Formulation of Locational Marginal Electricity-carbon Price in Power Systems. CSEE J. Power Energy Syst. 2023, 9, 1968–1972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liyanapathirane, U.; Khorasany, M.; Razzaghi, R. Optimization of Economic Efficiency in Distribution Grids Using Distribution Locational Marginal Pricing. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 60123–60135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Yao, L.; Liang, J.; Wang, J.; Cheng, F. Distributed optimization strategy for networked microgrids based on network partitioning. Appl. Energy 2025, 378, 124834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollitt, M.G.; von der Fehr, N.-H.M.; Willems, B.; Banet, C.; Le Coq, C.; Chyong, C.K. Recommendations for a future-proof electricity market design in Europe in light of the 2021–23 energy crisis. Energy Policy 2024, 188, 114051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhao, T.; Sun, D.; Ma, J.; Yu, H.; Yan, G.; Zhu, X.; Li, C. Multi-layer optimization method for siting and sizing of distributed energy storage in distribution networks based on cluster partition. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 501, 145260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, Y.; Sodhi, R.; Chakrabarti, S.; Sharma, A. A Novel Two-Stage Partitioning Based Reconfiguration Method for Active Distribution Networks. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2023, 38, 4004–4016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ez Eddin, M.; Massaoudi, M.; Abu-Rub, H.; Shadmand, M.; Abdallah, M. Optimum Partition of Power Networks Using Singular Value Decomposition and Affinity Propagation. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2024, 39, 6359–6371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Sun, Y.; Wang, Q.; Liu, F.; Zhu, L. Fast Power Grid Partition for Voltage Control With Balanced-Depth-Based Community Detection Algorithm. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2022, 37, 1612–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugunaraj, N.; Balaji, S.R.A.; Chandar, B.S.; Rajagopalan, P.; Kose, U.; Loper, D.C.; Mahfuz, T.; Chakraborty, P.; Ahmad, S.; Kim, T.; et al. Distributed Energy Resource Management System (DERMS) Cybersecurity Scenarios, Trends, and Potential Technologies: A Review. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparks, R.; Tobias, S.; Kemabonta, T.; Nelson, J.; Johnson, N. Microgrid system sizing and aggregation of distributed energy resources for wholesale market participation. Appl. Energy 2025, 400, 126537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, J.; Wu, Z.; Xu, J.; Hu, Q. A two-stage flow-based partition framework for unbalanced distribution networks. CSEE J. Power Energy Syst. 2023, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Alshehri, K.; Birge, J.R. Aggregating Distributed Energy Resources: Efficiency and Market Power. Manuf. Serv. Oper. Manag. 2024, 26, 834–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelbary, A.M.; Manglicmot, L.; Kanwhen, O.; Mohamed, A.A. Community-centric distributed energy resources for energy justice and decarbonization in dense urban regions. Energy Rep. 2024, 11, 1742–1751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paredes, Á.; Aguado, J.A.; Rodríguez, P. Uncertainty-Aware Trading of Congestion and Imbalance Mitigation Services for Multi-DSO Local Flexibility Markets. IEEE Trans. Sustain. Energy 2023, 14, 2133–2146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Qiu, J.; Zhang, C.; Lu, X.; Tao, Y.; An, S. An Encryption-Based Coordinated Kilowatt and Negawatt Energy Trading Framework. IEEE Internet Things J. 2025, 12, 48962–48977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Q.; Wang, J.; Lin, T.; Johnston, A.J. Peak-Valley Difference Based Pricing Strategy and Optimization for PV-Storage Electric Vehicle Charging Stations Through Aggregators. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2025, 169, 110812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siano, P.; Mohammad, D. MILP Optimization Model for Assessing the Participation of Distributed Residential PV-Battery Systems in Ancillary Services Market. CSEE J. Power Energy Syst. 2021, 7, 348–357. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, J.; Zhang, X.; Wang, S.; Zhao, W. ADMM-Based Two-Tier Distributed Collaborative Allocation Planning for Shared Energy Storage Capacity in Microgrid Cluster. Electronics 2025, 14, 3234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.; Yang, Z.; Yu, J.; Lai, X.; Xia, Q. Electricity Pricing Under Constraint Violations. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2020, 35, 2794–2803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Abdullah, Y.M.; Salloum, A.; Hedman, K.W.; Vittal, V. Analyzing the Impacts of Constraint Relaxation Practices in Electric Energy Markets. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2016, 31, 2566–2577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Luh, P.B.; Gribik, P.; Peng, T.; Zhang, L. Commitment Cost Allocation of Fast-Start Units for Approximate Extended Locational Marginal Prices. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2016, 31, 4176–4184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, K.; Zang, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhang, X. Electricity arbitrage for mobile energy storage in marginal pricing mechanism via bi-level programming. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2024, 162, 110330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitriadis, C.N.; Tsimopoulos, E.G.; Georgiadis, M.C. Co-optimized trading strategy of a renewable energy aggregator in electricity and green certificates markets. Renew. Energy 2024, 236, 121444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Hredzak, B.; Fletcher, J. Dynamic Aggregation of Energy Storage Systems into Virtual Power Plants Using Distributed Real-Time Clustering Algorithm. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2021, 68, 11002–11013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morstyn, T.; Hredzak, B.; Agelidis, V. Network Topology Independent Multi-Agent Dynamic Optimal Power Flow for Microgrids with Distributed Energy Storage Systems. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2018, 9, 3419–3429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Sun, Z.; Yang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Hu, G.; Chen, G. Study on Frequency Regulation Ancillary Service Trading Mechanisms for Distributed PV Generation. J. Glob. Energy Interconnect. 2020, 3, 477–486. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).