Abstract

Rambutan seed waste from fruit processing remains underutilized, while conventional biodiesel routes face high feedstock costs and food-versus-fuel concerns. This study investigated a novel catalyst-free process for biodiesel production from rambutan seed waste using supercritical ethanol and ethyl acetate as renewable reactants to valorize fruit by-products. Batch reactions on the semi-solid fraction of rambutan seed oil (RSO) were conducted at 15 MPa to evaluate the effects of temperature (275–375 °C), reactant-to-oil molar ratio (20:1–40:1), and reaction time (15–50 min) on fatty acid ethyl ester (FAEE) yield. Under optimal conditions, FAEE yields of 59.92 and 41.92% were obtained using ethanol (350 °C, 40:1, 30 min) and ethyl acetate (350 °C, 30:1, 40 min), respectively. However, severe conditions degraded unsaturated esters, revealing a conversion–stability trade-off. The ethanol system exhibited faster reaction kinetics and lower activation energy than ethyl acetate. Applying the optimized ethanol-based conditions to the liquid fraction of RSO, which contained a lower proportion of saturated fatty acids, resulted in a markedly improved FAEE yield of 94.16%. This study demonstrated a catalyst-free supercritical route for converting rambutan seed waste into biodiesel, advancing waste-to-energy strategies and circular bioeconomy.

1. Introduction

Biodiesel, a clean and renewable biomass-based fuel, is synthesized from various sources, including edible and non-edible oils, waste cooking oils, animal fats, and food industry by-products [1,2,3]. It shares similar attributes with conventional diesel, providing a sustainable energy alternative [1]. However, a crucial factor in biodiesel production is the selection of feedstock. Feedstock-related expenditures constitute approximately 80–85% of the total production expenses [4]. In addition, reliance on edible oils has sparked concerns over the food-versus-fuel conflict [5]. To address these economic challenges, current research efforts are focused on exploring novel, low-cost, non-edible feedstocks alongside efficient, sustainable catalytic systems to improve economic viability, process performance, and reduce the environmental footprint. For instance, biodiesel production from Acer truncatum seed oil using alkaline ionic liquid catalysts has demonstrated high conversion efficiency and excellent catalyst reusability, successfully integrating low-cost feedstock with advanced catalyst technology [6].

Rambutan (Nephelium lappaceum L.), an exotic tropical fruit, belongs to the Sapindaceae family and is primarily cultivated and exported by Thailand, Indonesia, and Malaysia [7]. The seeds, comprising 4.0–9.5% of the overall weight, are typically discarded as waste during processing. The annual output of rambutan in Thailand is around 0.22 million tons, corresponding to an estimated 8.80–20.90 thousand tons of discarded seeds [8]. Approximately 1900–2000 tons of seeds are generated annually from rambutan canning factories [7,9]. Fruit seed wastes, which are frequently discarded, landfilled, or incinerated [10,11] pose environmental risks due to greenhouse gas emissions and pollution [11,12]. The waste seeds of rambutan are rich in lipids, comprising approximately 14.7% to 41.3% of their dry weight, depending on several factors, including species, extraction method, and processing conditions [13,14]. The saturated and unsaturated fatty acids of rambutan seed fat were 44.19–62.50% and 37.51–45.18%, respectively [13]. Consequently, repurposing these lipid-rich seeds as a viable alternative feedstock for biodiesel production may substantially decrease the environmental footprint of seed disposal and support resource valorization within a bioeconomy.

Traditionally, biodiesel is produced via catalytic transesterification, which converts triglycerides (oils) with short-chain alcohols (typically methanol or ethanol) in the presence of catalysts into fatty acid methyl esters (FAME) or fatty acid ethyl esters (FAEE), with glycerol as a byproduct [15]. However, this process has several drawbacks. These include slow reaction times, soap formation, and low biodiesel yields when using low-quality feedstocks with high free fatty acid (FFA) or water content. Additionally, significant wastewater is generated during catalyst removal [16].

To address these challenges, Saka and Kusdiana (2001) [17] proposed a non-catalytic supercritical fluid technology. This method utilizes alcohols under supercritical conditions. Under these conditions, a single phase of oil/alcohol mixture is achieved due to high temperatures and pressures. This improves phase solubility and reduces mass-transfer limitations, enabling rapid transesterification [18]. This green technology offers several advantages, including catalyst-free operation, compatibility with low-cost feedstocks, no wastewater generation, shorter reaction times, and enhanced reaction speeds [19].

Ethanol is a green alternative reactant for biodiesel production due to its renewability and lower toxicity. It can be derived from sugar- or starch-rich renewable biomass through fermentation, making the synthesized ethyl esters entirely plant-based [20]. Although Thailand ranks seventh globally in ethanol production, an occasional oversupply has been observed [21,22]. Utilizing ethanol for biodiesel production offers cost-effective solutions and environmental benefits, helping to manage excess ethanol supplies. In addition to transesterification, ethyl acetate can be used as a reactant. Ethyl acetate, derived from ethanol dimerization, facilitates glycerol-free interesterification. This process produces FAEE and triacetin as a clean fuel additive [23].

Despite the promising potential of rambutan seed oil (RSO) as a biodiesel feedstock, its application has been scarcely explored. To the best of our knowledge, the production of rambutan seed oil-based biodiesel under supercritical ethanol and ethyl acetate has not been explored before. In the present study, non-catalytic lipid-based biofuel production from RSO in supercritical ethanol and ethyl acetate was experimentally investigated. The influence of key process parameters, including reaction temperature, reactant-to-oil molar ratio, reaction time, and the use of two distinct oil phases (semi-solid and liquid fractions) on FAEE yield was evaluated. This novel investigation enhances waste valorization and contributes to a more resilient and eco-friendly energy system within the circular bioeconomy.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Rambutan seed waste used in this study was sourced from Pissanumhon Food Products Company Limited, Chumphon Thailand. Ethanol (99.9% purity, Qrec, Auckland, New Zealand) and ethyl acetate (99.5% purity, KemAus, Cherrybrook, Australia) were utilized for the experimental procedures. N-heptane (99.5% purity) purchased from RCI Labscan Co., Ltd., Bangkok, Thailand, was used as a solvent for gas chromatography analysis to determine fatty acid composition and FAEE yield and composition. Ethyl arachidate (≥99%), ethyl oleate (98%), and triacetin (99%) were employed as external standard compounds obtained from Sigma Aldrich, Darmstadt, Germany.

2.2. Experimental Procedure

2.2.1. RSO Extraction and Characterizations

Fresh rambutan seeds were cleaned under running tap water and then dried in a hot air oven at 60 °C for 8 h. Rambutan seed oil (RSO), extracted from the dried rambutan seeds using a single-screw press machine (Model YZYX70-ZWY) provided by Mianyang Guang Xin Machinery Factory Co., Ltd., Guangzhou, China without prior size reduction. The screw rotational speed was maintained at 25 rpm with an extraction temperature of 80 °C and a feed rate of 7 kg/h. After extraction, heavy solid impurities were removed by filtration through a filter cloth. The filtered RSO was allowed to stand overnight at ambient temperature and was then stored at −20 °C until analysis. The extraction was performed in triplicate to ensure reproducibility. The average oil yield was 15.0 ± 0.40% (w/w, g oil per 100 g dried seed), calculated on a dry-weight basis. The distribution of fatty acids in RSO was analyzed using the AOCS official methods (Ce 2–66 and Ce 1–62). The free fatty acid (FFA) content was measured by titration in accordance with AOCS Official Method Ca 5a–40, while the density was determined using the gravimetric method. The molecular weight of RSO was estimated using a single pseudo-triglyceride approach. Initially, the molecular weight was calculated by assuming a pseudo-triglyceride composed of only one type of fatty acid and was subsequently corrected based on the fatty acid composition (wt.%) of RSO [24]. Table 1 details the composition of fatty acids, density, free fatty acid content, and molecular weight of RSO.

Table 1.

Average fatty acid composition, density, free fatty acid content, and molecular weight of semi-solid and liquid fractions of RSO.

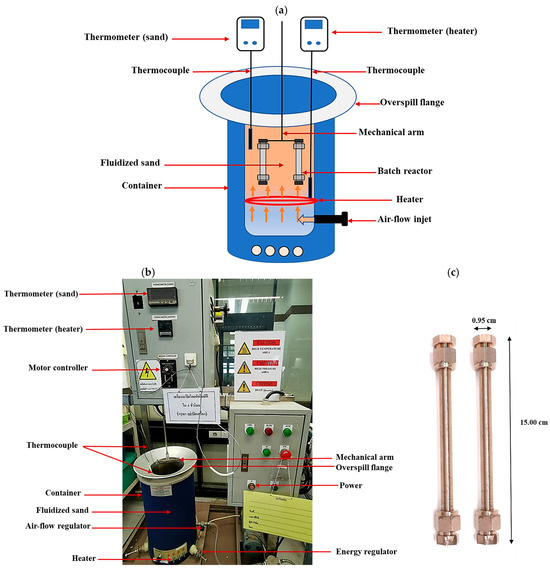

2.2.2. Biodiesel Production from RSO in a Batch Reactor

The extracted RSO, which exists in a semi-solid state at room temperature, was preheated to 60 °C prior to the initiation of the reaction. The conversion of RSO to FAEEs was carried out in a 4.38-mL batch reactor made of SUS316 stainless steel and sealed at both ends. The dimensions of the reactor were 0.95 cm in external diameter, 0.17 cm in wall thickness, and 15.00 cm in length (See Figure 1c). The experimental setup for the biodiesel production system is schematically represented in Figure 1a,b.

Figure 1.

(a) Drawing (figure not drawn to scale), (b) photograph of fluidized sand bath system, and (c) batch reactor used for biodiesel production from RSO in supercritical ethyl acetate and ethanol.

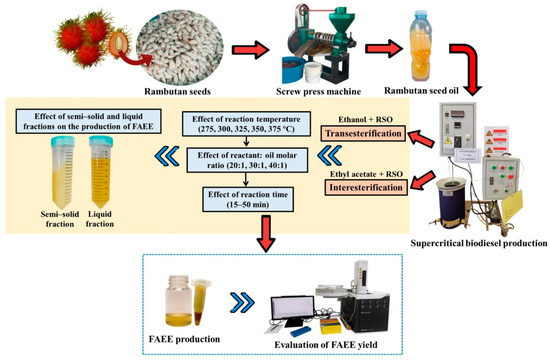

A fluidized sand bath (Model FSB-3, Omega Engineering, Norwalk, CT, USA) was utilized to heat the reactor to the specified temperature setpoint. Temperature monitoring and control were achieved with k-type thermocouples (VSC Advance, Nonthaburi, Thailand) and a PID controller (Model SF48, Sigma, Perkasie, PA, USA), respectively [28]. The amount of reactants loaded into the reactor was determined using the Peng–Robinson equation of state to achieve a final pressure of 15 MPa at the target temperature, as previously reported [29]. Accordingly, the loading volume was adjusted based on the experimental temperature at constant pressure. After the reactants were added, the reactor was sealed and submerged in the fluidized sand bath, thereby ensuring isothermal conditions and effective heat transfer. The batch reactor system operated at a heating rate of 30 °C/s, while the fluidized sand bath temperature fluctuated within a range of ±5 °C throughout the experiment. An electric motor was employed to agitate the reactor, ensuring uniform mixing. After achieving the desired reaction time, the reactor was promptly cooled in an ice bath to inhibit the reaction. Before gas chromatography (GC) analysis, the biodiesel product underwent nitrogen stripping at ambient conditions to remove excess ethanol and ethyl acetate, followed by phase separation via centrifugation (3000 rpm, 10 min) to remove the glycerol by-product. The overall methodology for FAEE production is shown in Figure 2. The effects of reaction temperature (275–375 °C), reactant-to-oil molar ratio (20:1, 30:1, and 40:1), and reaction time (15–50 min) were studied to determine the optimal conditions for FAEE production. All experimental procedures were performed in duplicate, and the data are reported as mean values with error bars representing the standard deviation (SD).

Figure 2.

Overall methodology.

2.2.3. Evaluation of FAEE Yield

The FAEE yield was evaluated using a modified method based on previous research [2], employing a Shimadzu gas chromatograph model GC2030 equipped with a DB-FATWAX capillary column (30 m × 0.25 mm i.d., 0.25 µm film thickness) and a flame ionization detector (FID). FAEE content was determined using external standard solutions of ethyl arachidate and ethyl oleate (0.625–10.000 wt.%) in n-heptane, with quantification based on the slope and intercept of the GC calibration curves. The five-point calibration curves for ethyl arachidate and ethyl oleate exhibited strong linear relationships, with correlation coefficients (R2) greater than 0.999. The total FAEE yield was then computed as a composition-weighted yield based on the distribution of the two most abundant fatty acids, oleic acid (C18:1) and arachidic acid (C20:0), in the RSO to accurately account for the different compositions of the semi-solid and liquid fractions. Similarly, triacetin content was quantified using a separate five-point calibration curve prepared from pure triacetin standards. Biodiesel samples were prepared by diluting 0.025 g of produced biodiesel with 0.975 g of n-heptane, followed by filtration through a 0.45 μm-membrane filter before injection. Method validation was conducted through spike-and-recovery analysis, in which a defined quantity of standard was added to the samples prior to analysis. Ultra-pure helium (99.999%) was used as the carrier gas at a constant flow rate of 0.92 mL/min. The injector temperature was established at 250 °C while the FID temperature was maintained at 300 °C. The analysis employed a split injection mode with a ratio of 31.9:1 and an injection volume of 1 µL.

2.2.4. Kinetic Modeling

Vegetable oils typically consist of 90–98 wt.% triglycerides (TG), along with small fractions of diglycerides (DG) and monoglycerides (MG) [30]. Both transesterification and interesterification are reversible reactions that proceed through three sequential steps. Triglycerides react with an ethylating agent to form diglycerides, which are then converted into monoglycerides and finally into FAEEs, with glycerol or triacetin as a byproduct [31]. Several studies on oil-based biodiesel production using supercritical alcohols have assumed that an excess of ethylating agent shifts the reaction forward, thereby minimizing the reverse reaction and allowing intermediates (DG and MG) to be neglected. Under these conditions, the reaction can be approximated as a pseudo-first-order [31,32]. In this study, the FAEE production from RSO using supercritical ethyl acetate or supercritical ethanol at optimal reactant-to-oil molar ratios was analyzed using a first-order kinetic model, as shown in Equation (1) [32]. The rate constant (k) was calculated by plotting −ln (1 − X) against the reaction time (t), where X represents the FAEE yield and t denotes the reaction time.

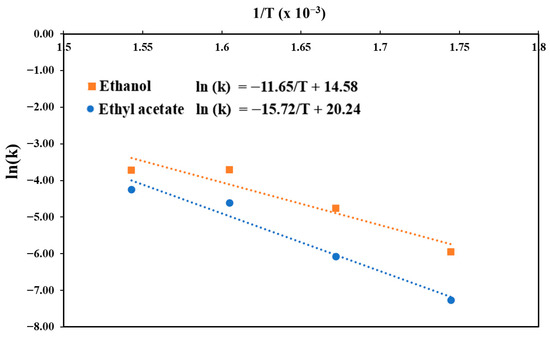

The activation energies of both reaction systems were derived from the slope of the linear regression of the Arrhenius plot, which relates the natural logarithm of the rate constant (ln (k)) to the reciprocal of absolute temperature (1/T).

2.2.5. Analysis of Semi-Solid and Liquid Fractions

The extracted RSO was stored overnight at room temperature (approximately 25 °C), resulting in spontaneous solid–liquid phase separation into a semi-solid fraction (~80% w/w) and a liquid fraction (~20% w/w). The liquid fraction was carefully collected by decantation and subsequently centrifuged at 5500 rpm for 10 min to improve purity. FAEE production from the liquid fraction of RSO was investigated under optimal reaction temperature and reactant-to-oil molar ratios previously established with the semi-solid fraction using supercritical ethyl acetate and ethanol. Table 1 shows a comparison of the fatty acid composition between the semi-solid and liquid fractions of RSO. Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy (PerkinElmer Spectrum One, universal ATR) was applied to characterize the functional groups and differentiate the two fractions, with spectra recorded in the range 4000–515 cm−1 at a resolution of 4 cm−1 using 64 scans. Statistical analysis of the experimental results was conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics 22.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA), and Tukey’s HSD test was applied to evaluate differences between groups at a significance level of p < 0.05. The synthesized FAEEs from the semi-solid and liquid fractions of RSO were evaluated for density, acid value, FFA, kinematic viscosity, and cloud point in compliance with EN 14214 [33] and ASTM D6751 [34,35] standards.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Analysis of RSO

Rambutan seed waste contained 15.0% oil, in agreement with the reported fat content of rambutan seeds in Thailand, which varies from 14.7% to 41.3% [26,36]. The fatty acid composition of the RSO in a semi-solid state comprises 51.39% saturated and 48.62% unsaturated fatty acids (Table 1). Oleic acid (C18:1) and arachidic acid (C20:0) were the predominant unsaturated and saturated fatty acids in the RSO, accounting for 41.49% and 34.50%, respectively. Other saturated fatty acids present in moderate amounts included stearic acid (C18:0) at 7.86%, gondoic acid (C20:1) at 7.11%, and palmitic acid (C16:0) at 4.30%. The relatively high level of saturated fatty acids contributes to a semi-solid texture at room temperature. The observed fatty acid profile is consistent with previous reports [25,26,27], as shown in Table 1, with variations in content attributed to differences in extraction methods and rambutan varieties [13,37].

3.2. Effect of Reaction Temperature and Reaction Time

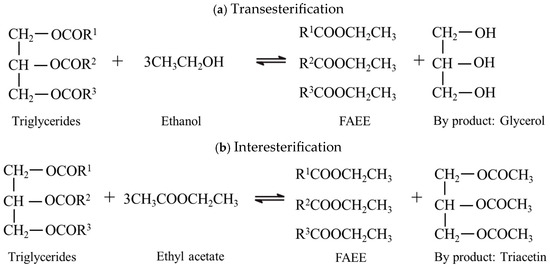

Ethanol and ethyl acetate have critical temperatures of 243.0 and 250.0 °C, with critical pressures of 6.3 and 3.8 MPa, respectively [38]. The reactions in supercritical biodiesel production were performed at temperatures well above the critical points of the involved alcohols and carboxylate esters. Transesterification and interesterification reactions using supercritical ethyl acetate and ethanol are illustrated in Figure 3. The reaction mechanism under supercritical conditions is hypothesized to proceed via a pathway analogous to acid catalysis in the absence of added catalyst. Supercritical conditions disrupt hydrogen bonding in alcohol molecules, creating highly reactive monomers. These monomers facilitate direct nucleophilic attack on the triglyceride carbonyl, driving stepwise transesterification to form FAAEs and liberate glycerol. Conversely, interesterification with supercritical ethyl acetate proceeds via nucleophilic acyl substitution. The fatty acyl groups from triglycerides transfer to the ethoxy groups of ethyl acetate, yielding FAAEs, while the acetyl group replaces the fatty acyl group on the glycerol backbone, leading to the formation of various acetins instead of glycerol. This differs from conventional acid/base catalysis, which requires catalyst-mediated carbonyl activation or alkoxide formation, followed by neutralization and phase separation [19,39,40].

Figure 3.

(a) Transesterification and (b) interesterification reactions involved in FAEE production.

Previous research has demonstrated that reaction pressure (15.0–30.0 MPa) had minimal impact on biodiesel production efficiency [41] and tended to plateau beyond 15 MPa [42]. Therefore, 15 MPa was selected based on optimal conditions from our previous studies [2,43,44].

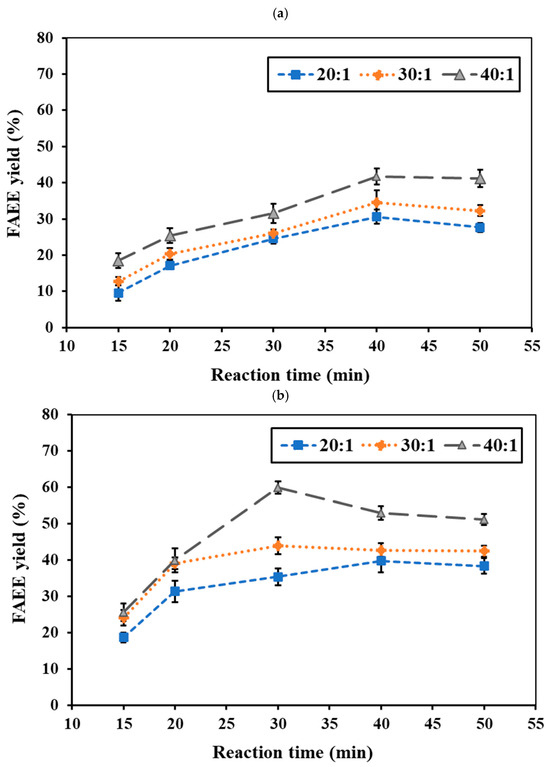

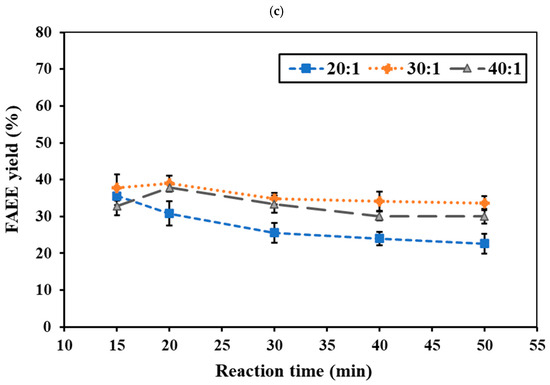

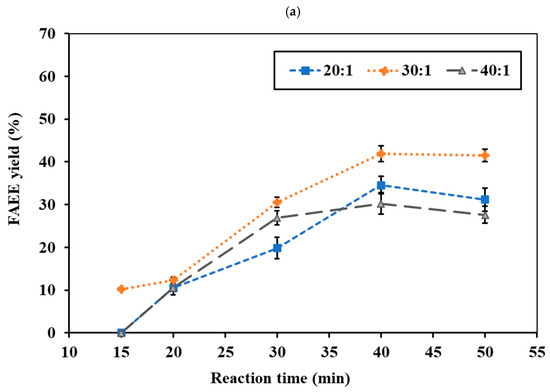

The reaction temperature and time represent critical factors in synthesizing FAEEs from RSO. No conversion occurred at 275 °C under supercritical conditions. At 300 °C, the ethanol system yielded <10% ester, while the ethyl acetate system showed <5%. Even at 325 °C, the ethyl acetate system remained below 10%, indicating higher temperatures are required for effective reaction. Figure 4a,b and Figure 5a,b show the effects of reaction temperature and reaction time on FAEE yield under a constant pressure of 15 MPa for the ethanol and ethyl acetate systems, respectively. In the ethanol system at 325 °C, the FAEE yield gradually increased with reaction time, reaching a peak of 41.71 wt.% at 40 min before slightly declining (Figure 4a). At 350 °C (Figure 4b), FAEE yields increased substantially, reaching the highest value of 59.92 wt.% at 30 min, then declined to 39–52 wt.%. At 375 °C (Figure 4c), rapid conversion occurred within 20 min, reaching 37.95%, followed by a gradual decrease. The ethyl acetate system showed a similar temperature-dependent trend (Figure 5a,b) but with slower reactions, requiring longer reaction times to achieve maximum FAEE yield. Maximum FAEE yield of 41.92 wt.% was achieved at 350 °C and 40 min, while 38.26 wt.% was obtained at 375 °C and 30 min, followed by a gradual decline in yield. Therefore, the ethanol system exhibited higher conversions and faster reaction rates compared to the ethyl acetate system. The superior performance of ethanol can be attributed to its smaller molecular size and reduced steric hindrance, facilitating better reactivity [45]. This observation is consistent with previous reports by Mani Rathnam et al. (2020) [31] and Muhammad Niza et al. (2011) [46], who found that smaller alcohols (ethanol and methanol) exhibited superior performance compared to their corresponding acetates. These results indicate that 350 °C was the optimal reaction temperature for FAEE production using supercritical ethanol and ethyl acetate, yielding the highest ester content at 30 and 40 min, respectively.

Figure 4.

Effects of ethanol-to-RSO molar ratio and reaction time on FAEE yield (%) at (a) 325 °C, (b) 350 °C, and (c) 375 °C under constant pressure of 15 MPa.

Figure 5.

Effects of ethyl acetate-to-RSO molar ratio and reaction time on FAEE yield (%) under supercritical conditions at (a) 350 °C and (b) 375 °C with fixed pressure of 15 MPa.

High temperature increases FAEE yield by improving reactant solubility and mass transfer, increasing particle kinetic energy, enhancing molecular collisions, and facilitating the cleavage of triglyceride bonds for ester formation [47,48]. However, excessive temperatures over extended periods can lead to thermal decomposition of unsaturated fatty acids, resulting in lower ester content [43,49]. Thermal decomposition was observed at 350 and 375 °C for ethanol (>30 and >20 min, respectively), and at 350 and 375 °C for ethyl acetate (>40 and >30 min, respectively). Thermal degradation of fatty acid esters under supercritical conditions leads to the formation of short-chain ethyl esters and low molecular-weight hydrocarbons, as reported in our previous work [41,43]. Thermal degradation of saturated and unsaturated fatty acid esters has been reported to occur at >400 and >350 °C, respectively [17,50]. The optimal temperature of 350 °C obtained in this study aligns with previous findings in non-catalytic supercritical transesterification and interesterification of various feedstocks, including palm kernel oil, coconut oil [51], soybean oil [52], rapeseed oil [39], canola oil [45], and animal fat [53].

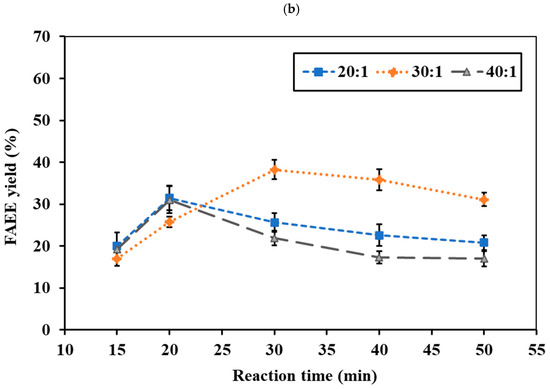

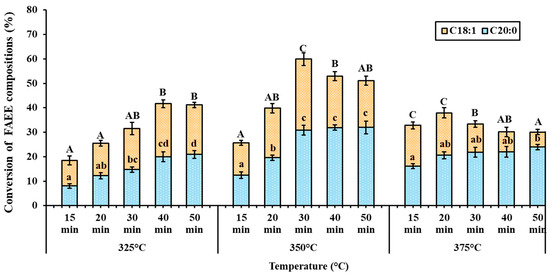

Statistically significant differences (p < 0.05) in the levels of ethyl oleate (C18:1) and ethyl arachidate (C20:0) in the obtained FAEE at the same reaction temperature were indicated by different letters, A–C and a–d, respectively (Figure 6). At 325 °C, the FAEE yield gradually increased with reaction time, reaching a plateau. At higher temperatures (350–375 °C), the C18:1 content increased and reached a maximum before declining due to thermal degradation, while the C20:0 content gradually increased and plateaued.

Figure 6.

Ethyl oleate (C18:1) and ethyl arachidate (C20:0) contents in obtained FAEE from various reaction times under supercritical conditions at 325, 350, and 375 °C and ethanol-to-oil molar ratio of 40:1, with fixed pressure of 15 MPa.

The presence of C=C double bonds in C18:1 induces decomposition mechanisms such as radical addition to the double bond and allylic hydrogen abstraction, which subsequently lead to β-scission reactions [54]. At 350 °C, the thermal decomposition of C18:1 ethyl ester was observed at 40 min, with a degradation of 27.94%. At 375 °C, degradation occurred earlier at 30 min (33.45% degradation), with further statistically significant reductions observed (Figure 6).

These findings demonstrate that increasing temperature can improve FAEE conversion, but prolonged exposure to high temperatures results in reduced FAEE production due to thermal decomposition.

The critical challenge in supercritical biodiesel production lies in achieving complete transesterification while preventing thermal degradation of FAEEs. Thermal decomposition of biodiesel includes isomerization (275–400 °C), polymerization (300–425 °C), and pyrolysis (>350 °C) [55]. Saka et al. [17] and Kusdiana et al. [50] reported that thermal degradation of saturated and unsaturated fatty acid esters occurs at >400 and >350 °C, respectively. There are several key strategies to prevent heat degradation. In terms of the reactant-to-oil molar ratio, employing a larger excess of reactant not only promotes forward reaction kinetics via Le Chatelier’s principle but may also provide a protective effect against thermal degradation, particularly for polyunsaturated fatty acid esters, as reported by Olivares-Carrillo et al. [56]. The polymerization of oils during thermal processing is primarily attributed to autoxidation, an oxygen-dependent mechanism [57,58]. Therefore, a sealed batch reactor with controlled heating duration was employed to restrict oxygen exposure and minimize polymerization. Consistent with this rationale, once the specified reaction time was achieved, the reactor was promptly removed from heat and quenched in an ice bath before depressurization to immediately halt reactions and prevent further thermal degradation [44,59]. Reactor design and heat transfer efficiency are crucial to ensure uniform heating and prevent hot spots. Although batch reactors provide controlled conditions for fundamental studies, continuous reactor systems with optimized heat exchange are often more suitable for large-scale operations, offering consistent product quality and reduced processing time [60].

3.3. Effect of Reactant: Oil Molar Ratio

In the ethanol-based system, increasing the ethanol-to-oil molar ratio from 20:1 to 40:1 significantly enhanced FAEE conversion, especially at the optimal temperature of 350 °C (Figure 4). The highest FAEE yield of about 60% was achieved at a molar ratio of 40:1 and a temperature of 350 °C. The stoichiometric conversion of triglycerides requires at least a 3:1 alcohol-to-oil molar ratio to produce three fatty acid alkyl esters per triglyceride molecule [38]. Since transesterification is a reversible process, excess reagent is necessary to drive the equilibrium toward increased ester products, by Le Chatelier’s principle [38,61]. Under supercritical conditions, alcohol molecules lose their ability to form hydrogen bonds and act as monomers. A large amount of alcohol is required to convert triglycerides into mono-alkyl esters by creating a homogeneous phase and lowering critical conditions [49]. An optimal ethanol-to-oil molar ratio of 40:1 in this study aligns with findings by Bolonio et al. [53] and Varma and Madras [62], who reported maximum conversion for linseed oil, castor oil, and animal fat under supercritical ethanol conditions. Exceeding this ratio did not improve biodiesel yields [62], and in some cases, yields were even reduced [63]. Additionally, this ratio has been proven effective across multiple feedstocks, including canola [45], sunflower [64], and soybean oils [52]. Higher ratios were not investigated due to economic and environmental concerns related to alcohol recovery [65].

Interestingly, as illustrated in Figure 4c, a molar ratio of 30:1 yields a higher FAEE than a ratio of 40:1 at 375 °C. This observation aligns with the findings of Sakdasri et al. [44], who reported that lower alcohol-to-oil molar ratios require higher temperatures for homogeneous supercritical phase formation due to increased global density. In the ethyl acetate-based system, increasing the ethyl acetate-to-oil molar ratio from 20:1 to 30:1 resulted in enhanced FAEE yield at both 350 and 375 °C (Figure 5). However, exceeding this ratio to 40:1 caused a decline in FAEE conversion. Similar results were reported by Sakdasri et al. [66], who demonstrated that increasing the ethyl acetate-to-oil molar ratio from 20:1 to 30:1 significantly enhanced FAEE content under supercritical conditions. Ratios exceeding 30:1 showed no additional improvement in FAEE yield due to reduced global density, which lowered the effective reaction temperature [49,66]. Notably, this molar ratio has also been proven effective in our previous works via supercritical interesterification with palm oil [67] and spent coffee grounds [2] as feedstocks. The results, as shown in Figure 4 and Figure 5, revealed that ethanol required a higher molar ratio (40:1) than ethyl acetate (30:1) to achieve optimal FAEE production. This difference can be attributed to ethanol’s higher polarity compared to ethyl acetate, which limits miscibility with oil and requires a greater excess to overcome mass transfer limitations and drive the reaction forward [68]. This may also be attributed to glycerol accumulation in ethanol-based systems, which shifts the equilibrium toward the reactants and necessitates a greater excess of ethanol to drive FAEE formation effectively [69].

No detectable level of glycerol was observed, and triacetin level was 0.20 wt.% in the FAEE product under optimal supercritical ethyl acetate conditions (350 °C, 30:1 molar ratio, 40 min). The absence of glycerol confirms that the reaction followed the intended interesterification pathway. This low triacetin content is comparable to the findings of Postaue et al. [70] and Stevanato et al. [68], who reported yields of ~0.70 and ~0.90 wt.%, respectively, at 300 °C, 20 MPa, and 15 min. The low level of triacetin in the product may be due to thermal degradation at the optimal temperature of 350 °C, since triacetin is sensitive to high temperatures, especially above 360 °C, as reported by Niza et al. [71].

3.4. Kinetic Model and Arrhenius Parameters

Previous research has shown that ester conversion processes conducted with excess alcohol typically exhibit pseudo-first-order kinetic behavior, as evidenced by various supercritical fluid studies on lipid-based feedstocks, including edible and non-edible oils [32,72] and algae-based feedstocks [31]. The reaction kinetics for FAEE production from RSO were studied under supercritical conditions of ethanol and ethyl acetate. Kinetic studies were conducted at temperatures ranging from 300 to 375 °C and reaction times of 0–50 min. Linear plots of ln(1 − X) versus reaction time validated the application of pseudo-first-order kinetics to both reaction systems, with correlation coefficients (R2) ranging from 0.97 to 0.99. The corresponding first-order rate constants (k) were determined from the slopes of these linear relationships. Table 2 shows that the rate constants for transesterification with the supercritical ethanol system ranged from 0.0026 to 0.0247 min−1, which are significantly higher than those for the interesterification with the supercritical ethyl acetate system, which ranged from 0.0007 to 0.0143 min−1. This suggests that the ethanol system exhibits greater reactivity compared to the ethyl acetate system. For the ethanol system, the highest rate constant of 0.0247 min−1 was observed at 350 °C, whereas for the ethyl acetate system, the highest value of 0.0143 min−1 was found at 375 °C. This is consistent with the findings of Stevanato et al. [68], who reported that ethyl acetate becomes more reactive at higher temperatures. However, ester degradation at elevated temperatures can limit the yields of FAEEs.

Table 2.

First-order rate constants and activation energies for FAEE production in supercritical ethyl acetate and supercritical ethanol.

Figure 7 illustrates the Arrhenius plots utilized to determine the activation energies for the interesterification and transesterification processes. The Arrhenius equations for RSO-based biodiesel production can be expressed as Equations (2) and (3) for the ethanol and ethyl acetate systems, respectively:

Figure 7.

Arrhenius plots for conversion of RSO to FAEE via interesterification and transesterification using supercritical ethyl acetate and ethanol.

The activation energies determined from the slopes were 96.83 kJ/mol for the ethanol system and 130.67 kJ/mol for the ethyl acetate system. These results are in agreement with the findings of Mani Rathnam et al. [31], who studied biodiesel production from Schizochytrium limacinum microalgae and reported that the ethanol system exhibited higher rate constants (1.02 × 10−2 to 6.12 × 10−2 vs. 2.43 × 10−3 to 1.91 × 10−2 min−1) and lower activation energy (67.1 vs. 78.5 kJ/mol) compared to the ethyl acetate system. These results indicate that the ethanol system exhibits superior kinetic performance under supercritical conditions, with a lower energy barrier and faster reaction rates than the ethyl acetate system. Santana et al. [73] and Sanjel et al. [74] reported activation energies for the transesterification of sunflower oil (150–200 °C, 20 MPa, fixed-bed continuous reactor) and waste soybean oil (210–350 °C, 5.1–16.5 MPa, batch reactor) in supercritical ethanol, which ranged from 58.6–140.0 kJ/mol and 61.0–116.2 kJ/mol, respectively. The activation energy obtained in this work falls within these ranges. However, the activation energy for the ethyl acetate system observed in this study was higher than that found in some previous studies, which range from 50 to 78 kJ/mol [31,67]. A possible reason for the high activation energy in this study is the higher proportion of saturated fatty acids in the feedstock, which previous studies report to have lower reactivity than unsaturated fatty acids [75,76].

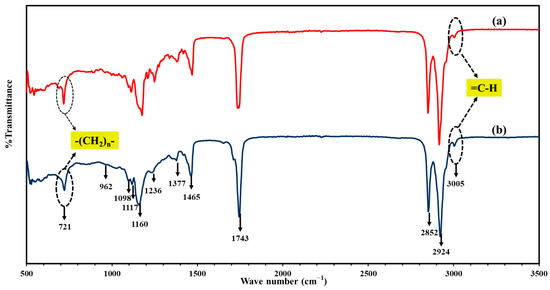

3.5. Effect of Semi–Solid and Liquid Fractions on the Production of FAEE

Oleic acid (C18:1) and arachidic acid (C20:0) were the most abundant unsaturated and saturated fatty acids identified in both the semi-solid and liquid fractions, with variations in their relative contents between the two phases, as shown in Table 1. The distinct physical appearances of the semi-solid and liquid fractions are shown in Figure 2. The semi-solid fraction contained a higher proportion of saturated fatty acids (51.39%) than the liquid fraction (42.70%). In contrast, the liquid fraction exhibited a higher concentration of oleic acid (C18:1) (44.96%) compared to the semi-solid fraction (41.49%), while arachidic acid (C20:0) content was significantly lower (28.00 vs. 34.50%). Figure 8 presents the FTIR spectra of the semi-solid and liquid fractions of RSO. The spectra of the semi-solid and liquid fractions of RSO are broadly similar, but differ in band sharpness and intensity. Major peaks included alkene =C–H stretching vibrations at 3005 cm−1, asymmetric and symmetric CH2 stretching at 2924 and 2852 cm−1, ester C=O stretching at 1743 cm−1, CH2 scissoring and CH3 bending vibrations at 1465 and 1377 cm−1, ester C-O stretching at 1236, 1160, 1117, and 1098 cm−1, =C–H out-of-plane bending vibration of trans-configuration alkenes at 962 cm−1, and CH2 rocking/crystallinity at 721 cm−1 [77]. The functional groups present in RSO are listed in Table 3. Consistent with these fatty acid compositional distinctions, the liquid fraction showed intensified =C–H stretching at 3005 cm−1, reflecting higher unsaturation, while the semi-solid fraction displayed stronger CH2 rocking at 721 cm−1, indicating greater molecular packing of saturated triacylglycerols.

Figure 8.

FTIR spectra of (a) the semi-solid and (b) liquid fractions of RSO.

Table 3.

FTIR peak assignments for RSO [77].

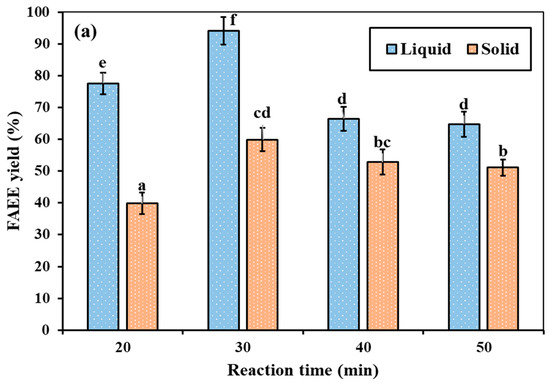

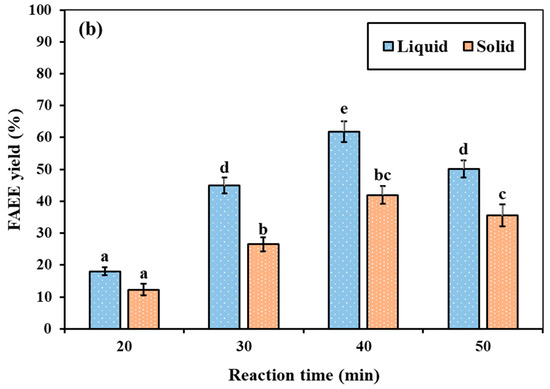

The spontaneous solid–liquid phase separation in RSO at room temperature is due to the difference in crystallization behavior and melting profiles of its triglyceride components. Solís-Fuentes et al. [14] found that the fat from rambutan seeds consisted of three main groups of triglycerides with different crystallization behaviors, featuring maximum crystallization temperatures of +30.8, +15.6, and −18.1 °C, respectively. The melting range of the fat is between −14.5 and +51.8 °C. Therefore, at ambient temperature, saturated triglycerides with higher melting points crystallize and form a semi-solid fraction, whereas unsaturated components with lower melting points remain in the liquid phase. This differential thermal behavior leads to the natural phase separation into semi-solid and liquid layers. Figure 9 illustrates the statistically significant differences (p < 0.05) in FAEE production between the semi-solid and liquid fractions of RSO under supercritical ethanol and ethyl acetate conditions. Different letters (a–f) are used to indicate statistically significant differences between the groups. The results revealed that the liquid fraction yielded significantly superior FAEEs compared to the semi-solid fraction for both supercritical ethanol and ethyl acetate reactions. Under supercritical ethanol conditions (350 °C, 15 MPa, and a molar ratio of 40:1), the liquid fraction achieved the highest FAEE yield of 94.16% at 30 min (Figure 9a). In contrast, the semi-solid fraction produced only 59.92% under the same conditions, which is approximately 1.6 times lower than that of the liquid fraction. Similarly, under supercritical ethyl acetate conditions (350 °C, 15 MPa, and a molar ratio of 30:1) (Figure 9b), the maximum yield from the liquid fraction was 61.88% at 40 min, compared to 41.92% for the semi-solid fraction under the same conditions. The greater reactivity of the liquid fraction can be attributed to its higher content of shorter-chain fatty acids and a lower degree of saturation. This observation aligns with the previous finding of Alonso et al. [78] that the transesterification reaction rate decreases significantly as the fatty acyl chain length increases. Longer, non-polar chains experience greater steric hindrance, which inhibits the reaction and leads to much lower activity than shorter chains. Additionally, previous findings have reported that oils with higher saturated fatty acid contents exhibit lower reactivity compared to oils with unsaturated fatty acid content, due to increased viscosity, steric hindrance, and limited mass transfer in the reaction [75,76].

Figure 9.

Comparison of FAEE yield (%) from semi-solid and liquid fractions of RSO under supercritical conditions at (a) 350 °C, ethanol-to-RSO molar ratio of 40:1, and (b) 350 °C, ethyl acetate-to-RSO molar ratio of 30:1, with fixed pressure of 15 MPa.

Consistently, Sáez-Bastante et al. [79] reported that mono- and di-unsaturated fatty acids contributed to higher FAME yields due to lower surface tension, enhancing the interfacial area and mass transfer efficiency.

Table 4 presents the properties of synthesized FAEEs from the semi-solid and liquid fractions of RSO compared to biodiesel standards. Fuel properties varied significantly between the two fractions due to differences in their fatty acid profiles. Although the ester contents achieved in this study did not reach the 96.5% minimum requirement specified by EN 14214, meeting this specification can be challenging in supercritical processes due to the thermal degradation of unsaturated fatty acids. However, this requirement is not included in ASTM D6751, and some countries, such as China, India, and Brazil, permit lower-ester biodiesel blends for use with petroleum diesel [41,66]. To improve FAEE content and meet the EN 14214 minimum requirement (≥96.5%), post-treatment dry-washing methods could be employed. These techniques, including silica-based adsorbents, activated carbon, and various biomass-based adsorbents, effectively remove residual impurities such as glycerides and FFAs without significant ester losses, thereby enhancing overall yield recovery [80,81]. For the liquid fraction, all properties are within the acceptable range of the standards. However, the viscosity and cloud point of FAEE derived from the semi-solid fraction exhibited values of 6.5 mm2/s and 15 °C, which exceed the biodiesel specification, consistent with its higher proportion of saturated fatty acids. For pure biodiesel (B100) applications, these limitations can be addressed through blending with more unsaturated biodiesel, using cold flow improvers to enhance cloud point performance, or modifying the ester composition through winterization or fractionation [82].

Table 4.

Evaluated properties of synthesized FAEEs a.

The ongoing reliance on crude palm oil for biodiesel production in Thailand raises sustainability concerns related to the food-versus-fuel conflict and the limited production area [83]. To meet the Alternative Energy Development Plan (AEDP)’s goal of 20–25% biofuel utilization by 2036, there is an urgent need to adopt alternative feedstocks, particularly those derived from non-edible oil sources or industrial by-products. Rambutan canning factories generate 1900–2000 tons of seeds annually as a by-product [7,9], offering a valuable opportunity for sustainable biodiesel production that contributes both renewable energy development and waste valorization. Among the 27 plant oils evaluated in Thailand, rambutan oil exhibited a high conversion efficiency and met biodiesel standards [26]. This study demonstrates advantages over conventional catalytic methods for rambutan seed biodiesel production, as summarized in Table 5. Nguyen et al. [3] achieved a 96.60% yield using sulfuric acid catalysis; however, this process involves corrosive reagents and poses challenges in hazardous chemical management. In the same study [3], heterogeneous catalysts including mesoporous SiO2–SO3H/CoFe2O4 and poly (vinylsulfonic-co-divinylbenzene) (PVS–DVB) were evaluated, offering easier catalyst recovery but yielding lower conversion rates (38.80–68.00%) with longer reaction times (10 h). Additionally, Wong and Othman [84] demonstrated that enzyme-catalyzed transesterification using immobilized Candida rugosa lipase achieved an 89.00% biodiesel yield from rambutan seed oil, representing an environmentally friendly approach; however, this process requires expensive enzymes and extended reaction times (24 h). All traditional methods depend on methanol, a toxic alcohol derived from fossil fuels. Conversely, this study achieved superior yields in 30 to 40 min through catalyst-free supercritical processing with renewable reactants and solvent-free extraction, thus promoting a fully green production process.

Table 5.

Comparison of biodiesel yields obtained from various catalytic and non-catalytic transesterification and interesterification using rambutan seed waste and other non-edible oils.

Several studies have employed supercritical ethanol and ethyl acetate for biodiesel production from non-edible feedstocks (Table 5). Comparative studies of supercritical biodiesel production have demonstrated varying performance among different feedstocks. Supang et al. [2,85] reported FAEE yields of 88.40 and 91.80% from spent coffee grounds using supercritical ethanol and ethyl acetate, respectively (275–325 °C, 40–50 min, and 15 MPa). In contrast, forage radish seed oil yielded only 30.15–53.03% under supercritical conditions at 300–325 °C and 20 MPa for 15–25 min [68]. Mani Rathnam et al. achieved >95% and >60% yields from microalgae using supercritical ethanol and ethyl acetate at 320 and 380 °C, respectively (20 MPa and 50 min) [31]. In comparison, this study attained comparable performance (94.16% with ethanol and 61.88% with ethyl acetate) from RSO under milder conditions (350 °C, 15 MPa, and 30–40 min). Furthermore, previous techno-economic analyses by Sakdasri et al. [65] reported that feedstock costs, particularly palm oil as Thailand’s primary biodiesel feedstock, contributed to over 50% of the total production costs in supercritical biodiesel processes. This emphasizes the critical importance of utilizing low-cost, non-edible alternatives to edible oils. Consequently, the present study highlights rambutan seed waste as a promising, cost-effective feedstock for producing clean and renewable biodiesel within a truly sustainable waste-to-energy framework.

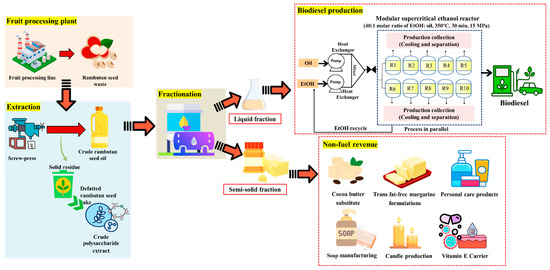

According to the results, the liquid fraction produced significantly more FAEE than the semi-solid fraction, highlighting a valuable opportunity to utilize RSO in a dual-purpose approach: the liquid fraction for high-efficiency biodiesel production and the semi-solid fraction as a cocoa butter substitute in confectionery and other products (Figure 10). Notably, the fatty acid profile of the semi-solid fraction closely resembles that of cocoa butter, containing 57–64% saturated and 36–43% unsaturated fatty acids [86]. Issara et al. reported that the high saturated fatty acid content of rambutan seed fat, particularly arachidic acid, makes it suitable as a cocoa butter substitute for direct commercial applications [87]. Beyond serving as a cocoa butter substitute, the semi-solid fraction can also be utilized in various applications, including margarine production, natural cosmetic products, soap and candle manufacturing, and as a vitamin carrier in nutraceutical formulations [13,37,88]. The dry fractionation process provides an environmentally friendly and solvent-free method for optimizing the melting properties and crystallization behavior of RSO, thereby achieving the desired fatty acid profiles for specific applications. Additionally, defatted rambutan seed cake, the primary non-hazardous waste stream of the process, can be valorized through polysaccharide extraction with antioxidant and potential prebiotic properties, thereby supporting the zero-waste concept as demonstrated by our research group [9].

Figure 10.

Proposed dual-purpose valorization pathway of rambutan seed waste for biodiesel production and value-added applications.

To implement these findings at the community level, a small-scale, modular biodiesel system is proposed for integration within existing fruit-processing plants. Seeds from the processing line would be mechanically pressed to extract crude rambutan seed oil, with the defatted cake that could be marketed as an animal feed supplement or sold to the pharmaceutical and nutraceutical sectors. The crude oil would undergo dry fractionation, yielding a liquid fraction suitable for biodiesel production, while the semi-solid fraction would be marketed as described above. The liquid fraction would feed a modular supercritical-ethanol reactor system comprising multiple parallel reactor modules (350 °C, 15 MPa, EtOH:oil = 40:1 molar, ~30 min). Oil and ethanol would be pumped independently at 25 °C and 1 bar, then be preheated and pressurized to 15 MPa via product-to-feed heat-recovery exchangers before being mixed in the reactors at 350 °C. Heat integration is critical to process viability. An optimized product-to-feed heat-exchanger network reduced external heating and cooling utilities by 32.2 and 23.8%, respectively [89]. Residual thermal energy from hot streams can be further recovered, valorized, and utilized through an organic Rankine cycle (ORC) to generate electric power [90]. After the reaction, the product streams would be cooled through the product-to-feed exchangers and then distilled to separate the unreacted ethanol for recycling. Glycerol would be removed by decantation, and a final distillation step would remove any remaining traces of ethanol [65]. Despite its high energy demand, the supercritical process achieves economic competitiveness with conventional methods by leveraging rapid reaction rates, flexibility with low-cost feedstocks, effective heat integration, and simplified downstream processing that eliminates catalyst costs and wastewater treatment [91].

At the community level, this integrated biorefinery would deliver environmental, economic, and social benefits by generating multiple revenue streams and promoting zero waste through the complete utilization of local resources. Additionally, it would fulfill local energy requirements, foster employment opportunities, and establish a rural circular bioeconomy, thereby empowering sustainable community development [92,93]. Future research should evaluate the economic and environmental feasibility of this integrated biorefinery approach through techno-economic analysis (TEA) and life-cycle assessment (LCA).

4. Conclusions

This study successfully demonstrated catalyst-free supercritical processes for biodiesel production from rambutan seed waste, using ethanol and ethyl acetate as renewable reactants. The ethanol system exhibited superior performance with lower activation energy (96.83 vs. 130.67 kJ/mol) and higher rate constants (0.0026–0.0247 vs. 0.0007–0.0143 min−1) compared to ethyl acetate, confirming the faster reaction rates and lower energy barrier of the ethanol-based pathway. Under optimal conditions (350 °C, 40:1 molar ratio, 30 min), the ethanol-based process achieved a 59.92% FAEE yield from the semi-solid fraction and 94.16% from the liquid fraction, which contains higher levels of unsaturated fatty acids. Thermal degradation of unsaturated esters at 350 and 375 °C (>30 and >20 min, respectively) limited further yield improvements. This catalyst-free supercritical process offers a sustainable solution for valorizing rambutan seed waste into biodiesel, thereby supporting Thailand’s AEDP goals for renewable energy and the development of the circular bioeconomy. Future work should focus on TEA and LCA to assess the economic viability and environmental sustainability of scaling this integrated biorefinery system.

Author Contributions

M.K.: Investigation, Writing—original draft, Funding acquisition. D.W.: Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing, Supervision, Funding acquisition. R.S.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing—review & editing. W.S.: Methodology, Investigation. P.H.: Supervision. P.S.: Funding acquisition. S.N.: Conceptualization, Writing—review & editing, Validation, Supervision, Resources. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data available on request from the authors.

Acknowledgments

This research project is supported by Chulalongkorn University, the Second Century Fund (C2F). This research is funded by Thailand Science Research and Innovation Fund Chulalongkorn University (IND66610028).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Yusuf, N.N.A.N.; Kamarudin, S.K.; Yaakub, Z. Overview on the current trends in biodiesel production. Energy Convers. Manag. 2011, 52, 2741–2751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Supang, W.; Ngamprasertsith, S.; Sakdasri, W.; Sawangkeaw, R. Ethyl acetate as extracting solvent and reactant for producing biodiesel from spent coffee grounds: A catalyst- and glycerol-free process. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2022, 186, 105586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.-D.; Thi Nguyen, M.-H.; Nguyen, T.-D.; Nguyen, P.-T. Nephelium lappaceum oil: A low-cost alternative feedstock for sustainable biodiesel production using magnetic solid acids. Environ. Prog. Sustain. Energy 2016, 35, 603–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gülşen, E.; Olivetti, E.; Freire, F.; Dias, L.; Kirchain, R. Impact of feedstock diversification on the cost-effectiveness of biodiesel. Appl. Energy 2014, 126, 281–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atabani, A.E.; Silitonga, A.S.; Badruddin, I.A.; Mahlia, T.M.I.; Masjuki, H.H.; Mekhilef, S. A comprehensive review on biodiesel as an alternative energy resource and its characteristics. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2012, 16, 2070–2093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; Sun, S. Unveiling the innovation: Optimized biodiesel production from emerging Acer truncatum Bunge seed oil using novel and highly effective alkaline ionic liquid catalyst. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 487, 150603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solís-Fuentes, J.A.; Galán-Méndez, F.; Hernández-Medel, M.d.R.; María del Carmen, D.-d.-B. Chapter 1—Rambutan (Nephelium lappaceum L.) seed and its fat. In Nuts and Seeds in Health and Disease Prevention, 2nd ed.; Preedy, V.R., Watson, R.R., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020; pp. 3–13. [Google Scholar]

- Chaidech, P.; Matan, N. Cardamom oil-infused paper box: Enhancing rambutan fruit post-harvest disease control with reusable packaging. LWT 2023, 189, 115539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilmat, K.; Ngamprasertsith, S.; Sakdasri, W.; Jirukkalul, P.; Karnchanatat, A.; Noitang, S.; Sawangkeaw, R. Polysaccharide extraction from defatted rambutan seeds with hot water and subcritical water extractions. Biol. Life Sci. Forum 2023, 26, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jantuma, N.; Ruangchai, S.; Ketkaew, C.; Naruetharadhol, P. Sustainability assessment for Thai mango: The environmental impact and economic benefits from cradle-to-grave. J. Infrastruct. Policy Dev. 2023, 7, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manhongo, T.T.; Chimphango, A.F.A.; Thornley, P.; Röder, M. Current status and opportunities for fruit processing waste biorefineries. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 155, 111823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muenmee, S.; Prasertboonyai, K. Potential biogas production generated by mono- and co-digestion of food waste and fruit waste (Durian shell, dragon fruit and pineapple peel) in different mixture ratio under anaerobic condition. Environ. Res. Eng. Manag. 2021, 77, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahurul, M.H.A.; Azzatul, F.S.; Sharifudin, M.S.; Norliza, M.J.; Hasmadi, M.; Lee, J.S.; Patricia, M.; Jinap, S.; Ramlah George, M.R.; Firoz Khan, M.; et al. Functional and nutritional properties of rambutan (Nephelium lappaceum L.) seed and its industrial application: A review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 99, 367–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solís-Fuentes, J.A.; Camey-Ortíz, G.; Hernández-Medel, M.d.R.; Pérez-Mendoza, F.; Durán-de-Bazúa, C. Composition, phase behavior and thermal stability of natural edible fat from rambutan (Nephelium lappaceum L.) seed. Bioresour. Technol. 2010, 101, 799–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasudevan, P.T.; Briggs, M. Biodiesel production—Current state of the art and challenges. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2008, 35, 421–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farobie, O.; Matsumura, Y. State of the art of biodiesel production under supercritical conditions. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2017, 63, 173–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saka, S.; Kusdiana, D. Biodiesel fuel from rapeseed oil as prepared in supercritical methanol. Fuel 2001, 80, 225–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.-S.; Saka, S. Biodiesel production by heterogeneous catalysts and supercritical technologies. Bioresour. Technol. 2010, 101, 7191–7200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ngamprasertsith, S.; Sawangkeaw, R. Transesterification in supercritical conditions. In Biodiesel—Feedstocks and Processing Technologies; Stoytcheva, M., Montero, G., Eds.; IntechOpen: Rijeka, Croatia, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Brunschwig, C.; Moussavou, W.; Blin, J. Use of bioethanol for biodiesel production. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2012, 38, 283–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaya, W.; Jesdapipat, S.; Tripetchkul, S.; Santitaweeroek, Y.; Gheewala, S.H. Challenges and pitfalls in implementing Thailand’s ethanol plan: Integrated policy coherence and gap analysis. Energy Policy 2019, 132, 1050–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumakiri, I.; Yokota, M.; Tanaka, R.; Shimada, Y.; Kiatkittipong, W.; Lim, J.W.; Murata, M.; Yamada, M. Process Intensification in Bio-Ethanol Production–Recent Developments in Membrane Separation. Processes 2021, 9, 1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esan, A.O.; Olabemiwo, O.M.; Smith, S.M.; Ganesan, S. A concise review on alternative route of biodiesel production via interesterification of different feedstocks. Int. J. Energy Res 2021, 45, 12614–12637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawangkeaw, R.; Bunyakiat, K.; Ngamprasertsith, S. Continuous production of biodiesel with supercritical methanol: Optimization of a scale-up plug flow reactor by response surface methodology. Fuel Process. Technol. 2011, 92, 2285–2292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, K.F.; Noranizan, M.A.; Roselina, K.; Yaya, R.; and Ghazali, H.M. Characteristics of fat, and saponin and tannin contents of 11 varieties of rambutan (Nephelium lappaceum L.) seed. Int. J. Food Prop. 2018, 21, 1091–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winayanuwattikun, P.; Kaewpiboon, C.; Piriyakananon, K.; Tantong, S.; Thakernkarnkit, W.; Chulalaksananukul, W.; Yongvanich, T. Potential plant oil feedstock for lipase-catalyzed biodiesel production in Thailand. Biomass Bioenergy 2008, 32, 1279–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonwai, S.; Ponprachanuvut, P. Characterization of physicochemical and thermal properties and crystallization behavior of krabok (Irvingia Malayana) and rambutan seed fats. J. Oleo. Sci. 2012, 61, 671–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Sakdasri, W.; Sawangkeaw, R.; Ngamprasertsith, S. Response surface methodology for the optimization of biofuel production at a low molar ratio of supercritical methanol to used palm olein oil. Asia-Pac. J. Chem. Eng. 2016, 11, 539–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakdasri, W.; Ngamprasertsith, S.; Saengsuk, P.; Sawangkeaw, R. Supercritical reaction between methanol and glycerol: The effects of reaction products on biodiesel properties. Energy Convers. Manag. X 2021, 12, 100145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, A.; Prasad, R. Triglycerides-based diesel fuels. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2000, 4, 111–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mani Rathnam, V.; Modak, J.M.; Madras, G. Non-catalytic transesterification of dry microalgae to fatty acid ethyl esters using supercritical ethanol and ethyl acetate. Fuel 2020, 275, 117998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamba, N.; Gupta, K.; Modak, J.M.; Madras, G. Biodiesel synthesis from Calophyllum inophyllum oil with different supercritical fluids. Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 241, 767–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barabás, I.; Todorut, I.-A. Biodiesel Quality, Standards and Properties. In Biodiesel—Quality, Emissions and By-Products; Montero, G., Stoytcheva, M., Eds.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim, M.L.; Rashid, T.D.U.; Yunus, R.; Taufiq-Yap, Y.H. ChemInform Abstract: Carbohydrate-Derived Solid Acid Catalysts for Biodiesel Production from Low-Cost Feedstocks: A Review. Catal. Rev. 2014, 56, 187–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, S.; Ali, R. Physico-chemical properties of biodiesel manufactured from waste frying oil using domestic adsorbents. Sci. Technol. Adv. Mater. 2015, 16, 034602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalayasiri, P.; Jeyashoke, N.; Krisnangkura, K. Survey of seed oils for use as diesel fuels. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 1996, 73, 471–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, K.; Kamilah, H.; Sulaiman, S.; Yang, T.; Fazilah, A. Valorization of rambutan (Nepheleum lappaceum L.) by-products: Food and non-food perspectives. Int. Food Res. J. 2018, 25, 892–902. [Google Scholar]

- Makareviciene, V.; Sendzikiene, E. Noncatalytic biodiesel synthesis under supercritical conditions. Processes 2021, 9, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goembira, F.; Matsuura, K.; Saka, S. Biodiesel production from rapeseed oil by various supercritical carboxylate esters. Fuel 2012, 97, 373–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casas, A.; Ramos, M.J.; Pérez, Á. Kinetics of chemical interesterification of sunflower oil with methyl acetate for biodiesel and triacetin production. Chem. Eng. J. 2011, 171, 1324–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngamprasertsith, S.; Laetoheem, C.-e.; Sawangkeaw, R. Continuous production of biodiesel in supercritical ethanol: A comparative study between refined and used palm olein oils as feedstocks. J. Braz. Chem. Soc. 2014, 25, 1746–1753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Wang, T.; Zhu, S. Continuous production of biodiesel fuel from vegetable oil using supercritical methanol process. Fuel 2007, 86, 442–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawangkeaw, R.; Teeravitud, S.; Bunyakiat, K.; Ngamprasertsith, S. Biofuel production from palm oil with supercritical alcohols: Effects of the alcohol to oil molar ratios on the biofuel chemical composition and properties. Bioresour. Technol. 2011, 102, 10704–10710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakdasri, W.; Sawangkeaw, R.; Ngamprasertsith, S. Continuous production of biofuel from refined and used palm olein oil with supercritical methanol at a low molar ratio. Energy Convers. Manag. 2015, 103, 934–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farobie, O.; Matsumura, Y. A comparative study of biodiesel production using methanol, ethanol, and tert-butyl methyl ether (MTBE) under supercritical conditions. Bioresour. Technol. 2015, 191, 306–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muhammad Niza, N.; Tan, K.; Ahmad, Z.; Lee, K.T. Comparison and optimisation of biodiesel production from Jatropha curcas oil using supercritical methyl acetate and methanol. Chem. Pap. 2011, 65, 721–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imahara, H.; Minami, E.; Hari, S.; Saka, S. Thermal stability of biodiesel in supercritical methanol. Fuel 2008, 87, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gumba, R.; Saallah, S.; Misson, M.; Ongkudon, C.; Anton, A. Green biodiesel production: A review on feedstock, catalyst, monolithic reactor, and supercritical fluid technology. Biofuel Res. J. 2016, 3, 431–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, C.; Kumar, N.; Gautam, R. Supercritical transesterification route for biodiesel production: Effect of parameters on yield and future perspectives. Environ. Prog. Sustain. Energy 2021, 40, e13685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusdiana, D.; Saka, S. Methyl esterification of free fatty acids of rapeseed oil as treated in supercritical methanol. J. Chem. Eng. Jpn. 2001, 34, 383–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunyakiat, K.; Makmee, S.; Sawangkeaw, R.; Ngamprasertsith, S. Continuous production of biodiesel via transesterification from vegetable oils in supercritical methanol. Energy Fuels 2006, 20, 812–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieitez, I.; da Silva, C.; Borges, G.R.; Corazza, F.C.; Oliveira, J.V.; Grompone, M.A.; Jachmanián, I. Continuous production of soybean biodiesel in supercritical ethanol−water mixtures. Energy Fuels 2008, 22, 2805–2809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolonio, D.; Marco Neu, P.; Schober, S.; García-Martínez, M.-J.; Mittelbach, M.; Canoira, L. Fatty acid ethyl esters from animal fat using supercritical ethanol process. Energy Fuels 2018, 32, 490–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Westbrook, C.K.; Cool, T.; Hansen, N.; Kohse-Höinghaus, K. The Effect of Carbon–Carbon Double Bonds on the Combustion Chemistry of Small Fatty Acid Esters. Z. Für Phys. Chem. 2011, 225, 1293–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, R.; Zhu, Y.; Tavlarides, L.L. Mechanism and kinetics of thermal decomposition of biodiesel fuel. Fuel 2013, 106, 593–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivares-Carrillo, P.; Quesada-Medina, J. Thermal decomposition of fatty acid chains during the supercritical methanol transesterification of soybean oil to biodiesel. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2012, 72, 52–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahir, Y.K. Lipid oxidation in biological systems: Biochemical, biological & biophysical aspects. Global J. Biosci. Biotechnol. 2015, 4, 224–233. [Google Scholar]

- Khor, Y.P.; Hew, K.S.; Abas, F.; Lai, O.M.; Cheong, L.Z.; Nehdi, I.A.; Sbihi, H.M.; Gewik, M.M.; Tan, C.P. Oxidation and Polymerization of Triacylglycerols: In-Depth Investigations towards the Impact of Heating Profiles. Foods 2019, 8, 475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboelazayem, O.; Gadalla, M.; Saha, B. Comprehensive Optimisation of Biodiesel Production Conditions via Supercritical Methanolysis of Waste Cooking Oil. Energies 2022, 15, 3766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acevedo-Quiroz, A.; Carrera-Avendaño, E.d.J.; Acevedo-Quiroz, N.; Alvarez-Gutiérrez, P.E.; Borunda, M.; Adam-Medina, M. Experimental Study on Biodiesel Production in a Continuous Tubular Reactor with a Static Mixer. Processes 2024, 12, 2859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torrentes-Espinoza, G.; Miranda, B.C.; Vega-Baudrit, J.; Mata-Segreda, J.F. Castor oil (Ricinus communis) supercritical methanolysis. Energy 2017, 140, 426–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varma, M.; Madras, G. Synthesis of biodiesel from castor oil and linseed Oil in supercritical fluids. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2007, 46, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, K.T.; Gui, M.M.; Lee, K.T.; Mohamed, A.R. An optimized study of methanol and ethanol in supercritical alcohol technology for biodiesel production. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2010, 53, 82–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madras, G.; Kolluru, C.; Kumar, R. Synthesis of biodiesel in supercritical fluids. Fuel 2004, 83, 2029–2033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakdasri, W.; Sawangkeaw, R.; Ngamprasertsith, S. Techno-economic analysis of biodiesel production from palm oil with supercritical methanol at a low molar ratio. Energy 2018, 152, 144–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakdasri, W.; Ngamprasertsith, S.; Daengsanun, S.; Sawangkeaw, R. Lipid-based biofuel synthesized from palm-olein oil by supercritical ethyl acetate in fixed-bed reactor. Energy Convers. Manag. 2019, 182, 215–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komintarachat, C.; Sawangkeaw, R.; Ngamprasertsith, S. Continuous production of palm biofuel under supercritical ethyl acetate. Energy Convers. Manag. 2015, 93, 332–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevanato, N.; de Mello, B.T.F.; Saldaña, M.D.A.; Cardozo-Filho, L.; da Silva, C. Production of ethyl esters from forage radish seed: An integrated sequential route using pressurized ethanol and ethyl acetate. Fuel 2023, 332, 126075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anastopoulos, G.; Zannikou, Y.; Stournas, S.; Kalligeros, S. Transesterification of vegetable oils with ethanol and characterization of the key fuel properties of ethyl esters. Energies 2009, 2, 362–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Postaue, N.; de Mello, B.T.F.; Cardozo-Filho, L.; da Silva, C. Use of the Product from Low Pressure Extraction (Crambe Seed Oil and Methyl Acetate) for Synthesis of Methyl Esters and Triacetin Under Supercritical Conditions. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 2020, 122, 2000004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niza, N.M.; Tan, K.T.; Lee, K.T.; Ahmad, Z. Biodiesel production by non-catalytic supercritical methyl acetate: Thermal stability study. Appl. Energy 2013, 101, 198–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathore, V.; Madras, G. Synthesis of biodiesel from edible and non-edible oils in supercritical alcohols and enzymatic synthesis in supercritical carbon dioxide. Fuel 2007, 86, 2650–2659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santana, A.; Maçaira, J.; Larrayoz, M.A. Continuous production of biodiesel using supercritical fluids: A comparative study between methanol and ethanol. Fuel Process. Technol. 2012, 102, 110–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanjel, N.; Gu, J.H.; Oh, S.C. Transesterification kinetics of waste vegetable oil in supercritical alcohols. Energies 2014, 7, 2095–2106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warabi, Y.; Kusdiana, D.; Saka, S. Reactivity of triglycerides and fatty acids of rapeseed oil in supercritical alcohols. Bioresour. Technol. 2004, 91, 283–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarve, A.; Varma, M.; Sonawane, S. Optimization and kinetic studies on biodiesel production from kusum (Schleichera triguga) oil using response surface methodology. J. Oleo. Sci. 2015, 64, 987–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohman, A.; Man, Y.B.C. Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy for analysis of extra virgin olive oil adulterated with palm oil. Food Res. Int. 2010, 43, 886–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, D.M.; Granados, M.L.; Mariscal, R.; Douhal, A. Polarity of the acid chain of esters and transesterification activity of acid catalysts. J. Catal. 2009, 262, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sáez-Bastante, J.; Pinzi, S.; Reyero, I.; Priego-Capote, F.; Luque de Castro, M.D.; Dorado, M.P. Biodiesel synthesis from saturated and unsaturated oils assisted by the combination of ultrasound, agitation and heating. Fuel 2014, 131, 6–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jariah, N.F.; Hassan, M.A.; Taufiq-Yap, Y.H.; Roslan, A.M. Technological Advancement for Efficiency Enhancement of Biodiesel and Residual Glycerol Refining: A Mini Review. Processes 2021, 9, 1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manuale, D.L.; Mazzieri, V.M.; Torres, G.; Vera, C.R.; Yori, J.C. Non-catalytic biodiesel process with adsorption-based refining. Fuel 2011, 90, 1188–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradana, Y.S.; Makertihartha, I.G.B.N.; Indarto, A.; Prakoso, T.; Soerawidjaja, T.H. A Review of biodiesel cold flow properties and its improvement methods: Towards sustainable biodiesel application. Energies 2024, 17, 4543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nutongkaew, P.; Waewsak, J.; Riansut, W.; Kongruang, C.; Gagnon, Y. The potential of palm oil production as a pathway to energy security in Thailand. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2019, 35, 189–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, C.S.; Othman, R. Biodiesel production by enzymatic transesterification of papaya seed oil and rambutan seed oil. Int. J. Eng. Technol. 2014, 6, 2773–2777. [Google Scholar]

- Supang, W.; Ngamprasertsith, S.; Sakdasri, W.; Sawangkeaw, R. Biodiesel production from spent coffee grounds by using ethanolic extraction and supercritical transesterification. Bioenerg. Res. 2024, 17, 2429–2439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azzatul, F.; Jahurul, M.H.A.; Norliza, J.; Norazlina, M.R.; Hasmadi, M.; Sharifudin, M.S.; Matanjun, P.; Lee, J.S. Characteristics of rambutan (Nephelium lappaceum L.) seed fat fractions and their potential application as cocoa butter improver. Food Res. 2020, 4, 852–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Issara, U.; Zzaman, W.; Yang, T. Rambutan seed fat as a potential source of cocoa butter substitute in confectionary product. Int. Food Res. J. 2014, 21, 25–31. [Google Scholar]

- Douniama-Lönn, G.V.; Ngakegni-Limbili, A.C.; Valentin, R.; Nsamoto, H.; Cerny, M.; Mouloungui, Z.; Ouamba, J.M. Fractionability of saturated and unsaturated fatty acid concentrates of rambutan oil with a freeze-thaw cold crystallization procedure. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2020, 44, e14396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboelazayem, O.; Gadalla, M.; Saha, B. Experimental-Based Energy Integrated Process for Biodiesel Production from Waste Cooking Oil Using Supercritical Methanol Chem. Eng. Trans. 2017, 61, 1645–1650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboelazayem, O.; Gadalla, M.; Alhajri, I.; Saha, B. Advanced process integration for supercritical production of biodiesel: Residual waste heat recovery via organic Rankine cycle (ORC). Renew. Energy 2021, 164, 433–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagapurkar, P.; Smith, J.D. Techno-economic and life cycle analyses for a supercritical biodiesel production process from waste cooking oil for a plant located in the Midwest United States. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2025, 27, 22749–22773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopresto, C. Sustainable biodiesel production from waste cooking oils for energetically independent small communities: An overview. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 22, 1953–1974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Sohail, M.T.; Zhang, Y.; Ullah, S. Bioenergy for sustainable rural development: Elevating government governance with environmental policy in China. Land 2024, 13, 2147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).