Abstract

Carnot Batteries with thermal integration stand as one of the most promising approaches to tackling contemporary global energy problems. Currently, research on Carnot Battery systems utilizing the ocean thermal gradient is still in its early stages. This paper establishes a holistic thermo-economic model to assess the system’s performance. Through working fluid screening and subsequent multi-objective optimization, this study identifies the optimal working fluid and clarifies the system’s thermal economy at the optimal design point. With round-trip efficiency and total cost as metrics, a sensitivity analysis identified key parameter effects on the system. This was followed by a multi-objective optimization, where the TOPSIS method selected the optimal solution. It was found that, when Ammonia and R1234yf were used as the working fluids in the RC and ORC sub-cycles, respectively, the system can achieve peak performances of 71.79% round-trip efficiency and 36.24% exergy efficiency. Moreover, the RC evaporation temperature exerts the most significant influence on the overall thermodynamic performance. Multi-objective optimization successfully identified a balanced thermo-economic design, yielding an optimal solution with a round-trip efficiency of 65.30% at a total cost of USD 65.90 M. These results offer critical insights for the design and optimization of this promising ocean thermal-powered Carnot Battery system.

1. Introduction

In recent years, China has made great efforts in the field of renewable energy and is gradually becoming a global leader in renewable energy development. The development and utilization of renewable energy currently face several challenges. One of these challenges is the uneven temporal and spatial distribution of the supply and demand of renewable electricity [1]. The existence of these problems necessitates the development of long-duration energy storage technologies [2]. As a relatively mature methodology, pumped hydro storage relies on the principle of converting water’s potential energy to store and discharge electrical power on a large scale. But it has long construction cycles and is constrained by geographical conditions [3]. Compressed air energy storage (CAES) is also suitable for large-scale energy storage, which also faces challenges such as the need for storage containers and geographical constraints [4].

The Carnot Battery (or Pumped Thermal Energy Storage) has emerged as a promising new contender in the field of energy storage [5,6]. Its principle is based on the integration of thermal cycles and thermal energy storage technology. When there is an excess of electricity generated from renewable energy sources, it is converted into the thermal energy. During peak electricity consumption periods, electricity is generated through a power cycle, using heat from the heat reservoir. Generally speaking, the Carnot Battery offers the following notable advantages: First, it has relatively high energy storage density and round-trip efficiency. For instance, a regenerated Carnot Battery system using nitrogen as the working fluid can achieve an energy storage density of 25.6 kWh/m3 and a round-trip efficiency of 65.6% [7]. Second, the economic advantages of this technology for large-scale deployment are significant, stemming primarily from its relatively low investment costs compared to other storage options [5,6,7]. Additionally, PTES is not constrained by geographical conditions, does not require specific terrain, and can be flexibly deployed in various scenarios, such as near wind farms, photovoltaic power plants, and traditional thermal power plants, greatly enhancing its applicability and adaptability [5,6].

Currently, research on Carnot Batteries (CBs) mainly focuses on systems based on the Brayton cycle and those based on the Organic Rankine Cycle (ORC) as a heat engine. Among these, the ORC-based Carnot Battery exhibits significant compatibility with low-grade heat sources [8]. The ORC-based Carnot Battery was firstly proposed by the ABB Group to address the high cost problem associated with the large-capacity, high-pressure storage tanks required in Brayton cycle systems [9]. Its maximum heat storage temperature was 123 °C, with a cycle efficiency of 53%. Based on their preliminary research, the company further developed a transcritical CO2 system incorporating both hot and cold water storage tanks, achieving a cycle efficiency of 60% and a heat storage temperature of 177 °C. Subsequently, Frate et al. [10] enhanced the conventional system structure by adding two regenerators to improve its thermal performance. From an economic perspective, the proposed regenerative system using thermal oil as the heat storage medium demonstrated a much higher performance. Moreover, to increase the energy storage density, Chen et al. [11] proposed a novel regenerative ORC-based Carnot Battery combined with a heat storage heat pump as the charge cycle. Transient simulation comparisons revealed that a maximum cycle efficiency of 47.67% could be reached, representing a 5.68% improvement over supplemental compressed air energy storage systems. In the context of thermal integration applications. Xi et al. [12] evaluated four different configurations of regenerative Carnot Batteries. Despite the higher initial investment from incorporating regenerators in both subsystems, their results identified this configuration as the most economically viable. Jockenhöfer et al. [13] proposed a subcritical heat pump energy storage system using butane as the working fluid, which achieved a net work ratio of 1.25 under a specific heat source and ambient temperature conditions. Hu et al. [14] undertook a thermo-economic study to evaluate the performance of an ORC-based Carnot Battery. An economic analysis indicated that the Levelized Cost of Storage (LCOS) of the system under design conditions was 0.18 USD/kWh, demonstrating economic feasibility for industrial waste heat recovery scenarios. To optimize the comprehensive performance of ORC-based Carnot Batteries, Xia et al. [15] carried out an integrated 4E (energy, exergy, economic, and environmental) analysis. This integrated approach enabled a complete evaluation of the system’s operational behavior, economic feasibility, and environmental footprint. In addition to system structure and thermodynamic performance, thermal storage performance is also a hot topic in this field. Eppinger et al. [16] developed and optimized a Carnot Battery based on both sensible heat and phase-change material. Their study found that the phase-change cold storage method significantly influences cooling performance. The system using cyclopentane as the working fluid achieved better cooling effects. In contrast, sensible heat storage systems were less affected by the working fluid, with R1233zd(E) being the recommended working fluid. Meanwhile, since the systems often adopt sensible heat storage, packed beds are considered more suitable. Ameen et al. [17] demonstrated that modern packed beds exhibit favorable thermal stratification, low pressure loss, and narrow thermoclines. Benato et al. [18] indicated that limestone is suitable for short-duration charge–discharge systems, while alumina is more appropriate for long-duration applications. Using temperature-sensitive ethanol VP-1 as the energy storage medium, a cycle conversion efficiency of up to 68% can be achieved.

Due to the unique advantages of ORC in the utilization of low-grade heat sources, the effective integration of multiple low-grade heat sources can improve the energy efficiency of ORC-based CBs and reduce dependency on high-quality heat. Their most important application is to integrate with heat from solar energy. To assess the viability of solar PV load shifting in an office building, Tassenoy et al. [19] carried out a techno-economic analysis of an ORC-based Carnot Battery. Considering the variation in electricity production, demand, and price, the authors denied the feasibility of installing the system. Kursun and Ökten [20] developed a comprehensive scenario analysis of a novel concentrated photovoltaic thermal system. The proposed system demonstrated a lower Levelized Cost of Storage (LCOS) under specific conditions compared to Li-ion and VRF batteries, based on a thermodynamic and economic comparison. Their further research indicated that a lower LCOS can be archived by replacing the heat pump with a resistance heater. However, exergy efficiency and round-trip efficiency will be affected [21]. Wang et al. [22,23] combined a flat plate collector with an ORC-based CB. The system performance under part-load conditions was analyzed through a life cycle assessment, and the optimal solutions were determined for the system using the five working fluids. In addition to solar energy, geothermal energy within a temperature band of 60–90 °C is also considered a suitable low-grade heat source for ORC-based CBs. Su et al. [24] introduced a comparative study of geothermal-integrated CBs in four different configurations. Through a multi-objective optimization, they concluded that the flash heat pump-ORC CB shows the best thermo-economic performance. Moreover, in the comprehensive review of various geothermal-integrated CBs, Wang et al. [25,26] highlighted the evaporator as the primary site of exergy destruction and the expander as the costliest component, with the evaporator being the second costliest. Yin et al. [27] provided configuration selection maps for 15 types of geothermal-integrated transcritical CBs. Optimization results indicated that, in the geothermal temperature ranges of 50~90 °C, the round-trip efficiency of the systems under optimal operation conditions varies from 66.2% to 105.6%. A minimum Levelized Cost of Storage of 0.472 CNY/kWh was achieved at a geothermal temperature of 90 °C, with the system cost exhibiting a declining trend as the temperature increases. Furthermore, as the industrial waste heat is cost-free and traditionally goes unused, it can be captured and converted through the ORC-based CB to useful power. Hu et al. [14] compared the economic performance of ORC-based CBs integrated by various low-grad heat sources. They found that waste heat is the most potential scenario for MW-scale thermal-integrated CB promotion. The multi-objective optimization indicated that gains in power-to-power efficiency (from 50% to 120%) come at the expense of a higher cost, which could increase by as much as 47%. Meanwhile, the cost of the system was sensitively affected by turbine’s efficiency. Therefore, optimizing the turbine is crucial for improving system economy. Barberis et al. [28] analyzed the potential valorization of industrial waste heat (100–400 °C) to enhance CB thermodynamic performance as well as increase energy efficiency of a cement production plant. The authors found that a CB consisting of highly efficient HP combined with the sCO2 power cycle can build a cost-effective system and could attract industrial customers’ interest. Ravindran et al. [29] experimentally studied the performance of a small-scale reversible high-temperature ORC-based CB for industrial waste heat (<100 °C) recovery. Peak performance was characterized by an overall cycle efficiency of 3.01% and a net power output of 512.4 W. Meanwhile, according to Zhou et al. [30], the waste heat can be flexibly allocated to serve both the HP and ORC sub-cycles. In the ORC, it functions as a preheater or regenerator. Such configuration with a R1233zd(E)-based mixture as the working fluid can enhance the power-to-power efficiency by 4.46–43.46%. Moreover, to assess the technical viability, Xue et al. [31] carried out a study on the integration of ORC-based CBs with waste heat from coal-fired power plants. A round-trip efficiency of 126% was observed under the highest waste heat temperature of 110 °C.

In addition to the low-grade energy mentioned above, the ocean temperature gradient also demonstrates its applicability as a heat source for integration with ORC-based CBs. Ocean thermal energy conversion is a highly potential marine renewable energy source [32,33]. The temperature differential between surface and deep ocean water drives the system’s energy generation. Typically, surface seawater is warmer due to factors such as solar radiation, while deep seawater remains at a relatively low temperature. The satellite images for South China Sea show the surface seawater temperature ranging from 24 to 29 °C, and at depths of approximately 800~1000 m, the water temperature varies between 4 and 6 °C [34]. According to our literature survey, there are only three reports on the integration of ocean thermal energy with CBs. The very first research on this conception was reported by Ghilardi et al. [35]. Centered on a shared thermal storage unit with phase-change material, the system coupled a vapor compression chiller and an Organic Rankine Cycle. The chiller mediated the conversion of electrical energy into cooling using the cold seawater, whereas the ORC performed the reverse function, converting thermal energy from the warm seawater into electricity. Following optimization, the system’s round-trip efficiency is determined to be between 30% and 52%. Furthermore, to identify the optimal design and layout for ORC-based CBs, their follow-up work [36] performed a sensitivity analysis focused on storage size and temperature. System configuration with and without ocean water re-injection was analyzed by using Aspen Hysys 2022. Additionally, an assessment of off-design performance evaluated the system’s potential, and a comparison of the LCOS with other technologies demonstrated its economic viability. A novel Carnot Battery system utilizing ocean thermal energy and a transcritical CO2 cycle was examined thermo-economically by Zhang et al. [37]. The investigation included a detailed analysis of how seawater depth affects system performance and a Monte Carlo-based cost uncertainty analysis. It was further found that the Levelized Cost of Storage decreases as the energy storage capacity increases.

The existing research on the ocean temperature gradient-integrated ORC-based Carnot Battery is still very limited. This study first establishes mathematical models for thermodynamic and economic analyses to enable a comprehensive thermo-economic evaluation. Then, it investigates the impact of critical parameters, such as evaporation temperature and storage temperature, on both thermodynamic and economic performance indices of the whole system. A screening process was conducted across different working fluids to determine the optimal fluid pair for the system. Thereafter, the multiple-objective optimization is employed to optimize the system performance using the screened working fluid, and the thermal economy and storage capacity of the optimal design point of the system are clarified.

2. System Description

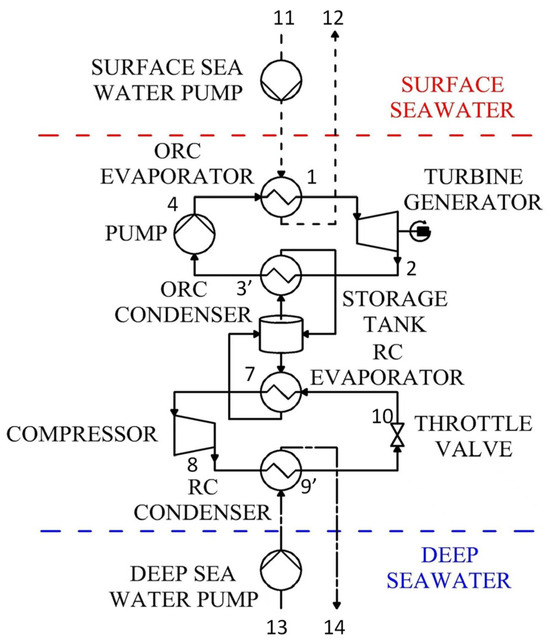

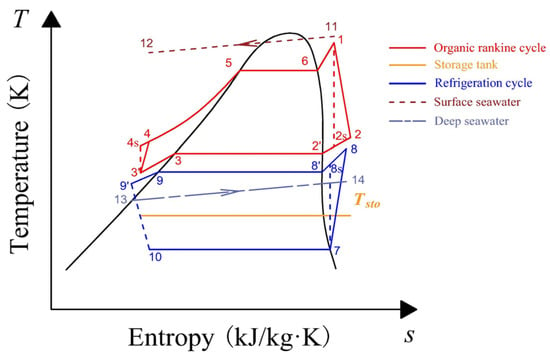

The system focused on in this paper consisted of a Refrigeration Cycle (RC) and an Organic Rankine Cycle (ORC). The system features a dual-mode operation, encompassing both energy charging and discharging phases. The charging mode is completed by the Refrigeration Cycle, which is driven by the excess electricity from renewable energy. It operates between the cold storage temperature Tsto and the deep seawater temperature Tdeep, using the deep seawater as a low-temperature heat sink to produce cooling energy, which is stored in the cold storage tank. During the discharging mode, the Organic Rankine Cycle operates between the surface seawater temperature Tsur and the cold storage temperature Tsto, driving a turbine to generate useful electricity. The charging (RC) cycle specifically integrates a compressor and a throttle valve, while the discharging (ORC) cycle is equipped with a turbine and a working fluid pump. The storage tank uses water–glycol as the phase-change material and operates at a constant temperature between the ORC condenser and the RC evaporator. The schematic diagram of the system and the temperature–entropy (T-s) diagram are shown in Figure 1 and Figure 2, respectively.

Figure 1.

System schematic diagram.

Figure 2.

T-s diagram of the system.

Surplus electricity is used to drive the RC compressor during the charging cycle. This compression act increases the temperature and pressure of the working fluid exiting the RC evaporator. The working fluid then enters the RC condenser, where it exchanges heat with deep seawater to reach a sub-cooled state. Subsequently, it passes through the throttle valve for expansion before entering the RC evaporator. Through a water–glycol loop, the cooling energy generated by the RC is stored in the storage tank. As shown in Figure 2, the charging cycle (RC) follows the sequence 7–8–9′–10–7, converting surplus electricity into cooling energy that is stored in the storage tank. Meanwhile, during peak grid periods, the ORC working fluid is heated by warm surface seawater in the evaporator, generating superheated vapor. This vapor consequently expands through the turbine, performing mechanical work that drives a generator to produce electricity. The low-pressure working fluid from the expander outlet next enters the condenser. There, it is cooled by a water–glycol loop that transfers heat to the storage tank, condensing the fluid into a subcooled liquid. Accordingly, the discharging cycle follows the sequence 1–2–3’–4–5–6–1 in the T-s diagram.

3. Mathematic Model

The development of mathematical and optimization models for the ORC-based Carnot Battery incorporated the following simplifying assumptions to facilitate the thermo-economic analysis.

- (1)

- Steady-state assumption is applied to all components [15].

- (2)

- Pressure drops throughout the system are considered negligible [20,21].

- (3)

- Heat transfer losses and frictional losses in the system are not considered [35,36].

3.1. Thermodynamic Model

During charging, the working fluid is compressed to a high-pressure state by the compressor. The device’s isentropic efficiency and the resulting cycle power consumption are subsequently determined by Equations (1) and (2).

In the condensation process 8–8′–9–9′, heat is transferred from the working fluid to the deep seawater in the RC condenser. The energy balance between the working fluid and deep seawater can be shown as follows:

In addition, during the condensation process, as deep seawater is pumped from a depth of about 800–1000 m into the system by a deep-seawater pump, its power consumption can be expressed as Equation (5), where ε = 0.5 is the surface roughness of the pipeline, and the pipeline diameter D can be calculated by Equation (6) [35]:

In the throttle process 9′–10, the specific enthalpy of the working fluid remains unchanged, as shown in Equation (7):

Heat absorption from the water–glycol mixture by the working fluid in the RC evaporator results in the storage of cooling energy in the tank. The energy balance between the working fluid and the water–glycol mixture in the storage tank can be shown with the following equation, where τcha is the charging duration of the CB (8):

The total power input for the RC charging cycle is calculated by summing the power consumption of the RC compressor and the deep-seawater pump.

The working fluid pump’s isentropic efficiency and power consumption during discharging are calculated as follows, where the pump pressurizes the fluid in the process 3′–4:

In the process 4–5–6–1, the working fluid absorbs heat from the warm surface seawater through the ORC evaporator. The energy balance between working fluid and surface seawater can be calculated with the following equations:

The 1–2 expansion process involves two steps: the working fluid converts thermal energy to mechanical work in the turbine; this work is then used to drive the generator, producing electricity. The isentropic efficiency and output power of the expander can be calculated as follows:

The condensation process in the ORC is shown as 2–2′–3–3′, and heat is transferred from the working fluid to the water–glycol mixture within the storage tank. The energy balance of the ORC condenser can be represented by the following equation:

where ηsto is the energy storage efficiency of the storage tank, defined as the ratio of the heat exchange amount between the working fluid and the water–glycol mixture in the ORC and RC, respectively. It can be shown with the following equation:

The net power output of the ORC discharge cycle is given by the difference between the turbine’s power production and the working fluid pump’s power draw:

The CB’s round-trip efficiency is the ratio of the ORC’s net discharging power to the RC’s total charging power input. This performance indicator can be calculated with the following equation:

In addition, round-trip efficiency can also be expressed as follows:

where EER and ηORC are the Energy Efficiency Ratio of RC and the thermal efficiency of ORC, respectively, which can be calculated by the following equations:

Moreover, in order to systematically understand the energy loss of the two subsystems of the CB and identify the weak links in energy conversion, an exergy analysis model has also been established. For any control volume, the exergy rate balance can be depicted as follows:

where Exin and Exout represent input and output exergy, respectively. W represents power, and I represents exergy destruction. The exergy destruction in different components can be determined according to the equations listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

The component-level exergy destruction [14].

The exergy at each state point can be calculated by the following equation:

The following equation determines the total exergy efficiency of the CB [15,19]:

where Exhs represents the exergy of the external heat source, which is warm seawater in this research, and it can be calculated as follows:

3.2. Economic Analysis

The total system cost from an engineering standpoint breaks down into initial investment and operational and maintenance costs. The initial investment cost for each component is derived from empirical formulas listed in Table 2. The costs of the water and throttle valve are excluded from this analysis due to their significantly lower values compared to other components [36,37].

Table 2.

Empirical models for investment cost of each component.

In Equation (32), Ai denotes the heat exchange areas. This area is a function of the total heat transfer and the specified pinch point temperature difference [45]. fm and fp represent material factor and pressure factor of heat exchangers, respectively. According to Ref. [38], their recommended values are 2.3 and 1.2.

The following equation determines the total system cost [44,46]:

where Cinv represents the initial investment cost, and the other costs are listed in Table 3.

Table 3.

Cost calculation formula of the system [45,47].

3.3. Working Conditions and Thermodynamic Calculation Process

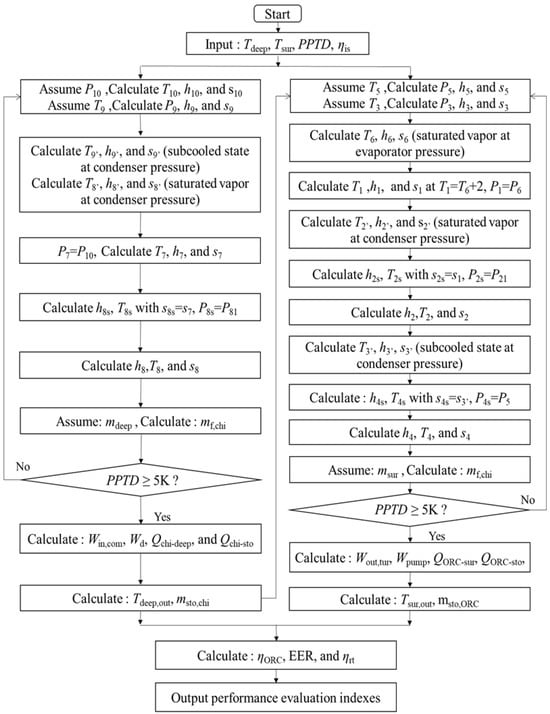

For further calculation and optimization, Table 4 listed the parameters of the system under design conditions. The thermodynamic calculation flowchart of RC and ORC is shown in Figure 3.

Table 4.

Thermodynamic design parameters of the Carnot Battery system.

Figure 3.

Thermodynamic calculation flowchart of the system.

3.4. Optimization Method

A multi-objective optimization approach is employed to balance the energy performance and economic performance of the CB. This research selects the round-trip efficiency (ηrt) and total system cost (Ctot) as energy and economic performance indicators, respectively. Here, we choose three critical system performance indicators as the decision variables: the ORC evaporation temperature (T5), RC evaporation temperature (T7), and storage tank temperature (Tsto). The overall optimization model is shown in the following equations:

The model code was developed on the MATLAB R2021a platform, with the thermophysical properties of the working fluids retrieved from the REFPROP 9.1 database [47]. The Non-dominated Sorting Genetic Algorithm (NSGA-II) was employed to resolve the multi-objective optimization problem. This method works by combining non-dominated sorting and crowding techniques with the selection, crossover, and mutation operations of Genetic Algorithms to create new offspring [48,49].

4. Results and Discussion

To evaluate the effects of different working fluid combinations, an initial thermodynamic simulation was carried out under the prescribed design conditions. The combinations yielding the highest thermodynamic performance were selected, enabling a detailed comparison of their characteristics. Based on the results of working fluid screening, a comparative analysis was conducted to evaluate how key thermodynamic parameters influence system performance. Finally, comparing the design and optimized conditions revealed the system’s optimization potential.

4.1. Model Verification

For the purpose of validating the mathematical model developed in this work, its simulation results for the system were compared against the data published in Reference [35]. As summarized in Table 5, a high level of consistency is observed, evidenced by a maximum relative error of only 3.1% for ηth of ORC. This strong agreement confirms the feasibility and reliability of the adopted thermodynamic model.

Table 5.

Model validation results *.

4.2. Effect of Working Fluid Combinations

Due to their distinct thermodynamic parameters, the working fluids for the two sub-cycles must be carefully selected. Based on an extensive review of thermo-physical properties, safety, and economic considerations from researchers and engineering fields, Ammonia, R152, R1234yf, and R1234ze were ultimately identified as candidates for this research. As shown in Table 6, the comparative analysis reveals the optimal working fluid combination for the proposed CB system. First, Ammonia is chosen as the RC charging cycle working fluid because its combinations consistently yield a higher RTE across all ORC fluids than other RC options. Subsequently, R1234yf is selected as the ORC charging cycle working fluid, as the Ammonia/R1234yf pair simultaneously maximizes both the round-trip efficiency (71.79%) and exergy efficiency (36.24%). Therefore, the following analysis focuses on the working fluid combination of Ammonia/R1234yf.

Table 6.

Performances of the CBs with different working fluid combinations.

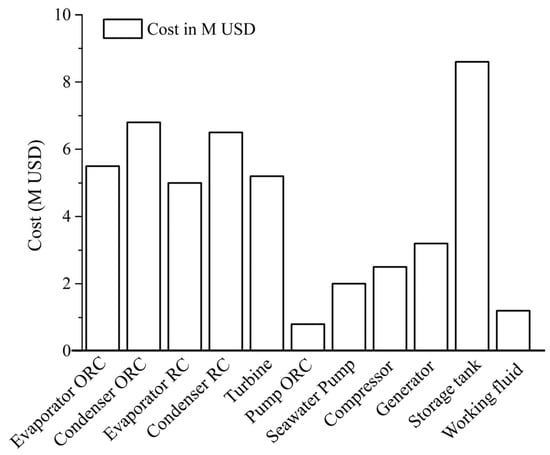

Figure 4 shows the investment cost of each main component from the CB using Ammonia/R1234yf as the working fluid under the design condition. The analysis shows that the storage tank accounts for the largest share of the total investment cost, followed by the condensers in both the RC and ORC sub-cycles and then the evaporators. The total investment cost of the main components is USD 47.3 M, and the total system cost calculated based on this is USD 70.71 M.

Figure 4.

Investment cost of each main component from CB.

4.3. Effect of RC Evaporation Temperature

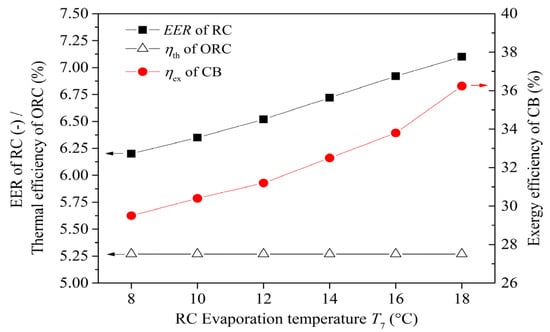

Figure 5 illustrates the variation in system thermodynamic performance across a range of RC sub-cycle evaporation temperatures (8–18 °C), a range dictated by the deep seawater inlet temperature. It can be found that, raising the evaporation temperature reduces the heat transfer temperature difference in the RC, thus improving the EER for the RC sub-cycle. However, with the surface seawater and storage temperatures held constant, the ORC thermal efficiency (ηth) remains unchanged. Meanwhile, a similar variation trend is observed between the overall CB system’s exergy efficiency (ηex) and the EER of the RC sub-cycle. As shown in Figure 5, as the evaporation temperature of RC sub-cycle increases from 8 °C to 18 °C, the EER of RC increases by nearly 15% and the CB system efficiency increases by nearly 20%.

Figure 5.

RC evaporation temperature vs. system thermodynamic performance.

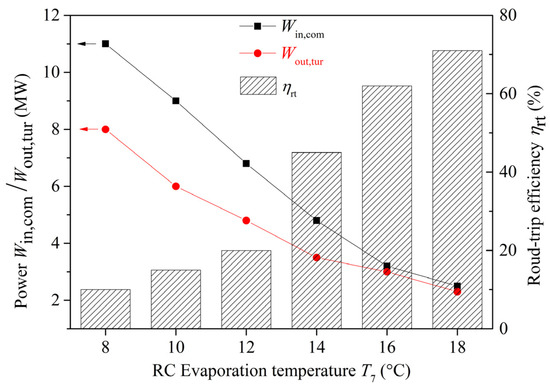

Figure 6 depicts the variations in system performance with RC evaporation temperature. As shown in this Figure, with the increase in RC evaporation temperature, the round-trip efficiency (ηrt) rises from 12% to over 70%. Meanwhile, the charge power in the compressor (Win,comp) and the ORC turbine output power (Wout,tur) gradually decrease. When the RC evaporation temperature rises from 8 °C to 18 °C, the charge power to the CB system (Win,comp) decreases from 11 MW to lower than 3 MW, and the output power from turbine (Wout,tur) decreases from 8 MW to nearly 2 MW.

Figure 6.

RC evaporation temperature vs. system overall performance.

4.4. Effect of ORC Evaporation Temperature

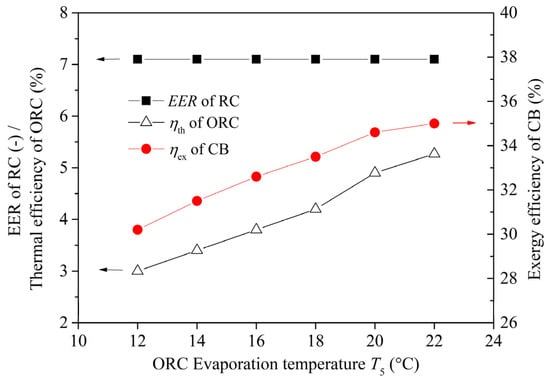

In addition to the RC evaporation temperature, another parameter that significantly affects system performance is the evaporation temperature of ORC sub-cycle, which is closely restricted by the surface seawater temperature. Figure 7 shows the relationship between ORC evaporation temperature and system thermodynamic performance. As shown in Figure 7, with the increase in ORC evaporation temperature, the thermal efficiency of ORC sub-cycle (ηth) and the exergy efficiency of CB system (ηex) are gradually rising, while the EER of RC remains unchanged. Specifically, as the ORC evaporation temperature is raised from 12 °C to 22 °C, the relative increase in ORC thermal efficiency is more than 75% and in exergy efficiency of the entire system is nearly 16%.

Figure 7.

ORC evaporation temperature vs. system thermodynamic performance.

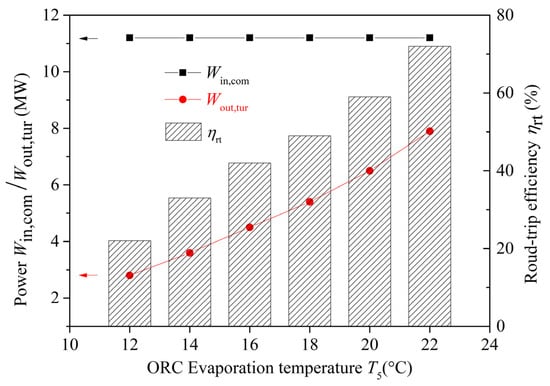

Regarding the input/output performance of the system, Figure 8 presents the variation trend of charge and discharged power with increased ORC evaporation temperature. Obviously, the ORC evaporation temperature has no effect on the charge power in the compressor (Win,comp) of RC sub-cycle. The system round-trip efficiency, however, offers significant potential for improvement, driven primarily by the increased turbine output power (Wout,tur) in the ORC sub-cycle. By analyzing the data from Figure 8, when the ORC evaporation temperature varies within 12–22 °C, the round-trip efficiency rises from 22% to over 70%.

Figure 8.

ORC evaporation temperature vs. system overall performance.

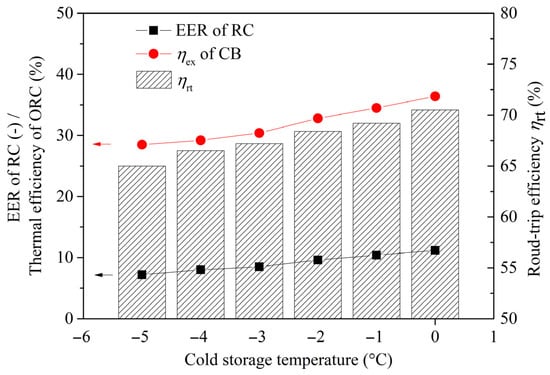

4.5. Effect of Cold Storage Temperature

The cold storage temperature is a critical parameter for the performance of both the RC sub-cycle’s EER and the overall CB system. Figure 9 investigates the effect of cold storage temperature (from −5 °C to 0 °C) on system performance. As shown in Figure 9, increasing the cold storage temperature leads to a decrease in the EER of the RC sub-cycle. This occurs because a higher cold storage temperature reduces the heat transfer temperature difference in the RC evaporator, which in turn increases the EER and exergy efficiency of the CB system. It is found that an increase in the cold storage temperature from −5 °C to 0 °C results in respective rises of 56% in the RC subsystem’s EER and 28% in the total CB system’s exergy efficiency. The round-trip efficiency increases from 65.0% to 70.5%. Variations in the cold storage temperature, however, leave the thermal efficiency of the ORC sub-cycle virtually unchanged.

Figure 9.

Effects of the cold storage temperature vs. system overall performance.

4.6. Multi-Objective Optimization

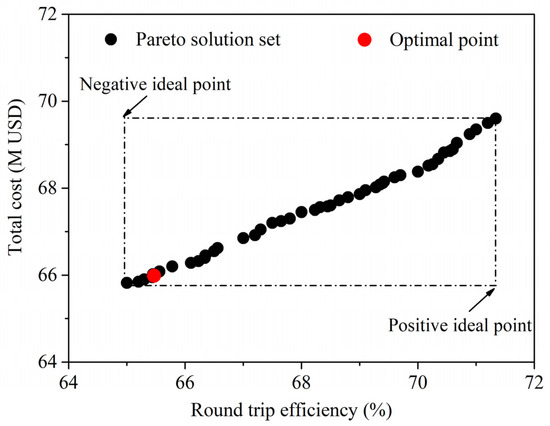

The parameter sensitivity analysis in Section 4.2, Section 4.3, Section 4.4 and Section 4.5 demonstrate that, among the several parameters investigated, both the evaporation temperatures of the RC and ORC subsystems (T7 and T5) and the temperature of cold storage (Tsto) exert a pronounced influence on the overall system performance. To leverage this insight, we conducted a multi-objective optimization targeting these three key parameters, with the round-trip efficiency (ηrt) and total system cost (Ctot) defined as the objective functions. As mentioned in Section 3.4, the NSGA-II algorithm is applied for this purpose. The simulation setup uses a population size of 100 and is run for a maximum of 300 generations.

Figure 10 presents the Pareto frontier for the abovementioned two objectives. The plot exhibits a clear trade-off, where an improvement in the round-trip efficiency (ηrt) is invariably accompanied by a simultaneously increase in the total system cost (Ctot). This competition between thermodynamic and economic performance means that the two objectives cannot be optimized at the same time. As shown in this figure, the total system cost rises from USD 65.82 M to USD 69.60 M, as the round-trip efficiency increases from 65.05% to 71.34%. The optimization results reveal two key points: a maximum round-trip efficiency of 69.9% is attained at the highest cost (USD 69.60 M), while the minimum cost (USD 65.82 M) corresponds to a round-trip efficiency of 65.05%. The TOPSIS method [50,51] was adopted for identifying the best compromise solution from the Pareto frontier. The TOPSIS approach relies on two reference points: the positive ideal, representing the best achievable performance, and the negative ideal, representing the poorest performance present in the Pareto set. TOPSIS performs ranking based on the relative distances of alternatives to both ideal points, with the goal of selecting the option that best balances closeness to the positive benchmark and remoteness from the negative benchmark. According to this method, the optimal solution can be found and marked as a red point in Figure 10. At this point, round-trip efficiency of the system is 65.30% and the total cost is USD 65.90 M.

Figure 10.

Multi-objective optimization results.

5. Conclusions

The thermo-economic performance of an ocean-driven, ORC-based Carnot Battery system is examined in this study. The system is systematically investigated and optimized to balance these two aspects. This study began by establishing thermodynamic and economic models to assess the influence of critical thermodynamic parameters, such as the RC and ORC sub-cycle evaporation temperatures and the cold storage temperature. For the performance and economic objectives, the round-trip efficiency and total cost were selected as the respective indicators. The parameter sensitivity analysis was conducted. The effect of key parameters on thermodynamic performance of two sub-cycles, as well as the whole system, was discussed in detail. Subsequently, multi-objective optimization was performed to identify the optimal solution via the TOPSIS method. The key findings are summarized below:

- (1)

- Ammonia and R1234yf proved to be the optimal working fluids for the RC and ORC sub-cycles, respectively, under the specified design conditions. With this configuration, the system reached its peak performance: a 71.79% round-trip efficiency and a 36.24% exergy efficiency.

- (2)

- The RC evaporation temperature has the greatest effect on system thermodynamic performance; as the evaporation temperature of RC sub-cycle increased, the EER of RC increased by nearly 15% and the CB system efficiency increased by nearly 20%. Meanwhile, raising the evaporation temperature of the ORC sub-cycles can significantly enhance its thermal efficiency, without affecting the RC system, while the cold storage temperature has no significant impact on the thermal efficiency of ORC sub-cycle.

- (3)

- A TOPSIS-based multi-objective optimization was conducted to achieve an optimal trade-off between the system’s thermodynamic and economic performance. The optimal solution is characterized by a round-trip efficiency of 65.30% with a corresponding total cost of USD 65.90 M.

It should be pointed out that, in future research, the authors will further calculate the LCOS of the proposed system and use it as a benchmark to compare the technical and economic performance of the CBs with other long-term energy storage technologies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.L. and J.D.; methodology, L.L. and Y.Y.; software, Y.Y.; validation, L.L.; investigation, Y.Y.; resources, Y.Y. and J.D.; data curation, Y.Y. and J.D.; writing—original draft preparation, L.L. and Y.Y.; writing—review and editing, L.L.; visualization, Y.Y.; supervision, L.L.; project administration, L.L.; funding acquisition, L.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Nomenclature

| C | Cost, USD |

| D | Diameter, m |

| cp | Specific heat, kJ·kg−1K−1 |

| E | Exergy, W |

| h | Specific enthalpy, kJ·kg−1 |

| H | Latent heat, kJ·kg−1 |

| I | Exergy destruction, W |

| Mass flow rate, kg/s | |

| m | Mass, kg |

| Q | Heat capacity, W |

| PPTD | Pinch point |

| s | Specific entropy, kJ·kg−1K−1 |

| △s | Entropy difference, kJ·K−1 |

| T | Temperature, K |

| △T | Temperature difference, K |

| τ | Time duration, h |

| v | Velocity, m/s |

| V | Volume, m3 |

| W | Work, W |

| ε | Roughness, m |

| η | Efficiency, % |

| Subscripts | |

| 0 | Environment state |

| 1–14 | State point |

| com | Compressor |

| cha | Charge |

| cri | Critical |

| deep | Deep seawater |

| dis | Discharge |

| ex | Exergy |

| f | Working fluid |

| g | Generator |

| hs | Heat storage |

| in | Inlet |

| inv | Investment |

| is | Isentropic |

| o | Outlet |

| ORC | ORC sub-cycle |

| RC | Refrigeration sub-cycle |

| sto | Storage |

| t | Storage tank |

| tot | Total |

| tur | Turbine |

| w | Water |

References

- Li, M.H.; Liu, X.X.; Yang, M. Analyzing the regional inequality of renewable energy consumption and its driving factors: Evidence from China. Renew. Energy 2024, 223, 120043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mclarnon, F.R.; Cairn, E.J. Energy storage. Annu. Rev. Energy 1989, 14, 241–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.M.; Oni, A.O.; Gemechu, E.; Kumar, A. The development of techno-economic models for the assessment of utility-scale electro-chemical battery storage systems. Appl. Energy 2021, 283, 116343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jankowski, M.; Pałac, A.; Sornek, K.; Goryl, W.; Żołądek, M.; Homa, M.; Filipowicz, M. Status and Development Perspectives of the Compressed Air Energy Storage (CAES) Technologies—A Literature Review. Energies 2024, 17, 2064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumont, O.; Frate, G.F.; Pillai, A.; Lecompte, S.; De Paepe, M.; Lemort, V. Carnot battery technology: A state-of-the-art review. J. Energy Storage 2020, 32, 101756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novotny, V.; Basta, V.; Smola, P.; Spale, J. Review of Carnot Battery Technology Commercial Development. Energies 2022, 15, 647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.H.; Bai, H.P.; Jiang, P.; Xu, Q.; Taghav, M. Economic, energy and exergy assessments of a Carnot battery storage system: Comparison between with and without the use of the regenerators. J. Energy Storage 2022, 50, 104577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Wang, S.Y.; Xu, S.G.; Wang, Q.W.; Markides, C.H. An intensive review of ORC-based pumped thermal energy storage. Energy 2025, 330, 136792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morandin, M.; Mercangöz, M.; Hemrle, J.; Maréchal, F.; Favrat, D. Thermoeconomic design optimization of a thermo-electric energy storage system based on transcritical CO2 cycles. Energy 2013, 58, 58571–58587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frate, F.; Ferrari, L.; Desideri, U. Multi-criteria investigation of a pumped thermal electricity storage (PTES) system with thermal integration and sensible heat storage. Energy Convers. Manag. 2020, 208, 112530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Hu, P.; Zhao, P.P. Thermodynamic analysis of a high temperature pumped thermal electricity storage (HT-PTES) integrated with a parallel organic Rankine cycle (ORC). Energy Convers. Manag. 2018, 77, 150–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, R.; Xi, H. Exergoeconomic optimization and working fluid comparison of low- temperature Carnot battery systems for energy storage. J. Energy Storage 2022, 51, 104453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jockenhofer, H.; Steinmann, W.D.; Bauter, D. Detailed numerical investigation of a pumped thermal energy storage with low temperature heat integration. Energy 2018, 145, 665–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Yang, Z.; Li, J.; Duan, Y. Thermo-economic analysis of the pumped thermal energy storage with thermal integration in different application scenarios. Energy Convers. Manag. 2021, 236, 114072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, R.; Wang, Z.; Cao, M.; Jiang, Y.; Tang, H.; Ji, Y.; Han, F. Comprehensive performance analysis of cold storage Rankine Carnot batteries: Energy, exergy, economic, and environmental perspectives. Energy Convers. Manag. 2023, 293, 117485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eppinger, B.; Zigan, L.; Karl, J.; Will, S. Pumped thermal energy storage with heat pump-ORC-systems: Comparison of latent and sensible thermal storages for various fluids. Appl. Energy 2020, 280, 15940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameen, M.T.; Ma, Z.; Smallbone, A.; Norman, R.; Roskilly, A.P. Experimental study and analysis of a novel layered packed-bed for thermal energy storage applications: A proof of concept. Energy Convers. Manag. 2023, 277, 116648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benato, A.; Stoppato, A. Integrated thermal electricity storage system: Energetic and cost performance. Energy Convers. Manag. 2019, 197, 111833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tassenoy, R.; Couvreur, K.; Beyne, W.; De Paepe, M.; Lecompte, S. Techno-economic assessment of carnot batteries for load-shifting of solar PV production of an office building. Renew. Energy 2022, 199, 1133–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kursun, B.; Okten, K. Comprehensive energy, exergy, and economic analysis of the scenario of supplementing pumped thermal energy storage (PTES) with a concentrated photovoltaic thermal system. Energy Convers. Manag. 2022, 260, 115592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kursun, B. Comparison with carnot battery of an alternate thermal electricity storage charged by concentrated photovoltaic thermal system and resistance heater. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2025, 258, 124587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Li, Q.; Wang, S.; He, C.; Wu, C. Off-design performance evaluation of thermally integrated pumped thermal electricity storage systems with solar energy. Energy Convers. Manag. 2024, 301, 118001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Li, Q.; Wang, S.; Xiao, T.; Wu, C. Thermo-economic and life cycle assessment of pumped thermal electricity storage systems with integrated solar energy contemplating distinct working fluids. Energy Convers. Manag. 2024, 318, 118895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Z.; Yang, L.; Song, J.; Jin, X.; Wu, X.; Li, X. Multi-dimensional comparison and multi- objective optimization of geothermal-assisted Carnot battery for photovoltaic load shifting. Energy Convers. Manag. 2023, 289, 117156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Li, Q.; Wang, S.; He, C.; Tang, J. Thermo-economic analysis and comparative study of different thermally integrated pumped thermal electricity storage systems. Renew. Energy 2023, 217, 119150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Li, Q.; Liu, C.; Wang, R.; Luo, Z.; Zou, P.; Wang, S. Comparative analysis of system performance of thermally integrated pumped thermal energy storage systems based on organic flash cycle and organic Rankine cycle. Energy Convers. Manag. 2022, 273, 116416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, S.Z.; Bai, C.G.; Zheng, K.Y.; Zhang, Y.L.; Yan, X.P.; Liu, Z. Geothermal energy-assisted pumped thermal energy storage: Configuration mapping. Energy Convers. Manag. 2025, 329, 119660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barberis, S.; Maccarini, S.; Shamsi, S.S.M.; Traverso, A. Untapping Industrial Flexibility via Waste Heat-Driven Pumped Thermal Energy Storage Systems. Energies 2023, 16, 6249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravindran, R.V.; Cotter, D.; Wilson, C.; Huang, M.J.; Hewitt, N.J. Experimental investigation of a small-scale reversible high-temperature heat pump—organic Rankine cycle system for industrial waste heat recovery. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2024, 257, 124237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T.; Shi, L.; Sun, X.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, Y.; Yao, Y.; Pan, Z.; Hu, Q.; Jiang, Z.; Tian, H.; et al. Performance enhancement of thermal-integrated Carnot battery through zeotropic mixtures. Energy 2024, 311, 133328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, X.J.; Zhao, Y.; Zhao, C.Y. Multi-criteria thermodynamic analysis of pumped- thermal electricity storage with thermal integration and application in Electric Peak shaving of coal-fired power plant. Energy Convers. Manag. 2022, 258, 115502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, F.M.; Wang, X.R.; Mei, Y.L.; Tian, R. A comprehensive review on ocean thermal energy conversion technology: Thermodynamic optimization, multi-energy integration, and byproduct utilization. Energy Convers. Manag. 2025, 27, 101188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, W.Z.; Wang, F.; Zhang, Y.; Tian, Z.; Wu, D.W.; Farrukh, S. Review of performance improvement strategies and technical challenges for ocean thermal energy conversion. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2025, 266, 125506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.K. A Survey of Ocean Energy Resources China; China Ocean Press: Beijing, China, 1987; pp. 93–106. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Ghilardi, A.; Baccioli, A.; Frate, G.F.; Ferrari, L. Thermodynamic feasibility of a pumped thermal energy storage driven by ocean temperature gradient. In Proceedings of the 7th International Seminar of ORC Power Systems, Seville, Spain, 9–11 September 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Ghilardi, A.; Baccioli, A.; Frate, G.F.; Volpe, M.; Ferrari, L. Integration of ocean thermal energy conversion and pumped thermal energy storage: System design, off-design and LCOS evaluation. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2024, 236, 121551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.L.; Liu, J.X.; Liu, Z. Thermo-economic examination of ocean heat-assisted pumped thermal energy storage system using transcritical CO2 cycles. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2025, 255, 123992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamdy, S.; Morosuk, T.; Tsatsaronis, G. Exergetic and economic assessment of integrated cryogenic energy storage systems. Cryogenics 2019, 99, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benato, A. Performance and cost evaluation of an innovative Pumped Thermal Electricity Storage power system. Energy 2017, 138, 419–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, T.; Vecchi, A.; Knobloch, K.; Sciacovelli, A.; Engelbrecht, K.; Li, Y.L.; Ding, Y.L. Key components for Carnot Battery: Technology review, technical barriers and selection criteria. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 163, 112478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez, J.C.; Ochoa, G.V.; Duarte-Forero, J. A comparative study of the energy, exergetic and thermo-economic performance of a novelty combined Brayton S-CO2-ORC configurations as bottoming cycles. Heliyon 2020, 6, e04459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Li, J.; Yang, F.; Yang, Z.; Duan, Y. Multi-objective optimization of organic Rankine cycle using hydrofluorolefins (HFOs) based on different target preferences. Energy 2020, 13, 117848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carotenuto, A.; Figaj, R.; Vanoli, L. A novel solar-geothermal district heating, cooling and domestic hot water system: Dynamic simulation and energy-economic analysis. Energy 2017, 141, 2652–2669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.Y.; Lin, X.X.; Su, W.; Ding, R.C.; Liang, Y.R. Thermo-Economic Potential of Carnot Batteries for theWaste Heat Recovery of Liquid-Cooled Data Centers with Different Combinations of Heat Pumps and Organic Rankine Cycles. Energies 2025, 18, 1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coker, A. Ludwig’s Applied Process Design for Chemical and Petrochemical Plants; Gulf Professional Publishing: Woburn, MA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Li, F.H.; Xing, L.L.; Su, W.; Lin, X.X.; Liang, Y.R.; Shi, W.J. An idea to construct integrated energy systems of data center by combining CO2 heat pump and compressed CO2 energy storage. J. Energy Storage 2024, 75, 109581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homepage of NIST Reference Fluid Thermodynamic and Transport Properties Database. Available online: https://www.nist.gov/srd/refprop (accessed on 6 September 2025).

- Mohan, S.; Sinha, A. Elitist non-dominated sorting directional bat algorithm (ENSdBA). Expert. Syst. Appl. 2023, 227, 120292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Li, J.; Yang, F.; Yang, Z.; Duan, Y. How to design organic Rankine cycle system under fluctuating ambient temperature: A multi-objective approach. Energy Convers. Manag. 2020, 224, 113331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirazi, A.; Najafi, B.; Aminyavari, M.; Rinaldi, F.; Taylor, R.A. Thermal–economic–environmental analysis and multi-objective optimization of an ice thermal energy storage system for gas turbine cycle inlet air cooling. Energy 2014, 69, 212–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadni, F.E.; Salhi, I.; Belhora, F.; Hajjaji, A. Multi-objective optimization of energy and exergy efficiencies in ORC configurations using NSGA-II and TOPSIS. Therm. Sci. Eng. Prog. 2025, 63, 103606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).