Energy Communities, Renewables, and Electric Mobility in the Italian Scenario: Opportunities and Limitations in Historic Town Centers

Highlights

- What are the main findings?

- Analysis of renewable energy communities’ potential in Italian towns.

- Overview of photovoltaic and electric mobility integration in historic districts.

- What are the implications of the main findings?

- Limitations and benefits analysis in European and Italian context.

- Assistance to researchers, energy providers, and policymakers in REC spread in Italy.

Abstract

1. Introduction

Methodology and Approach of the Literature Review

2. Italian Scenario for Energy Transition

2.1. The Territorial Context

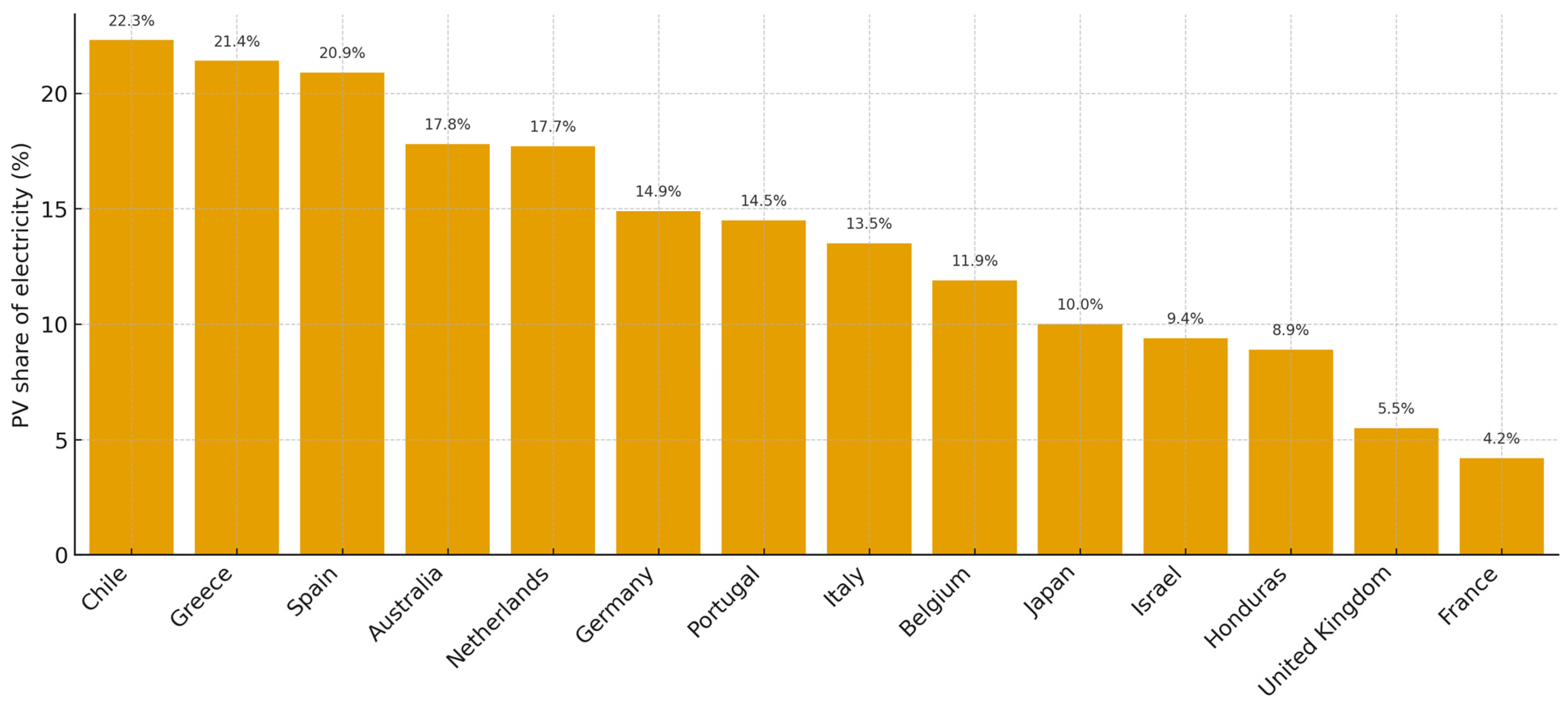

2.2. Photovoltaic Diffusion: Challenges and Limitations in Small Villages

2.3. Electric Vehicles in Italy: Dispositions and Opportunities for Development

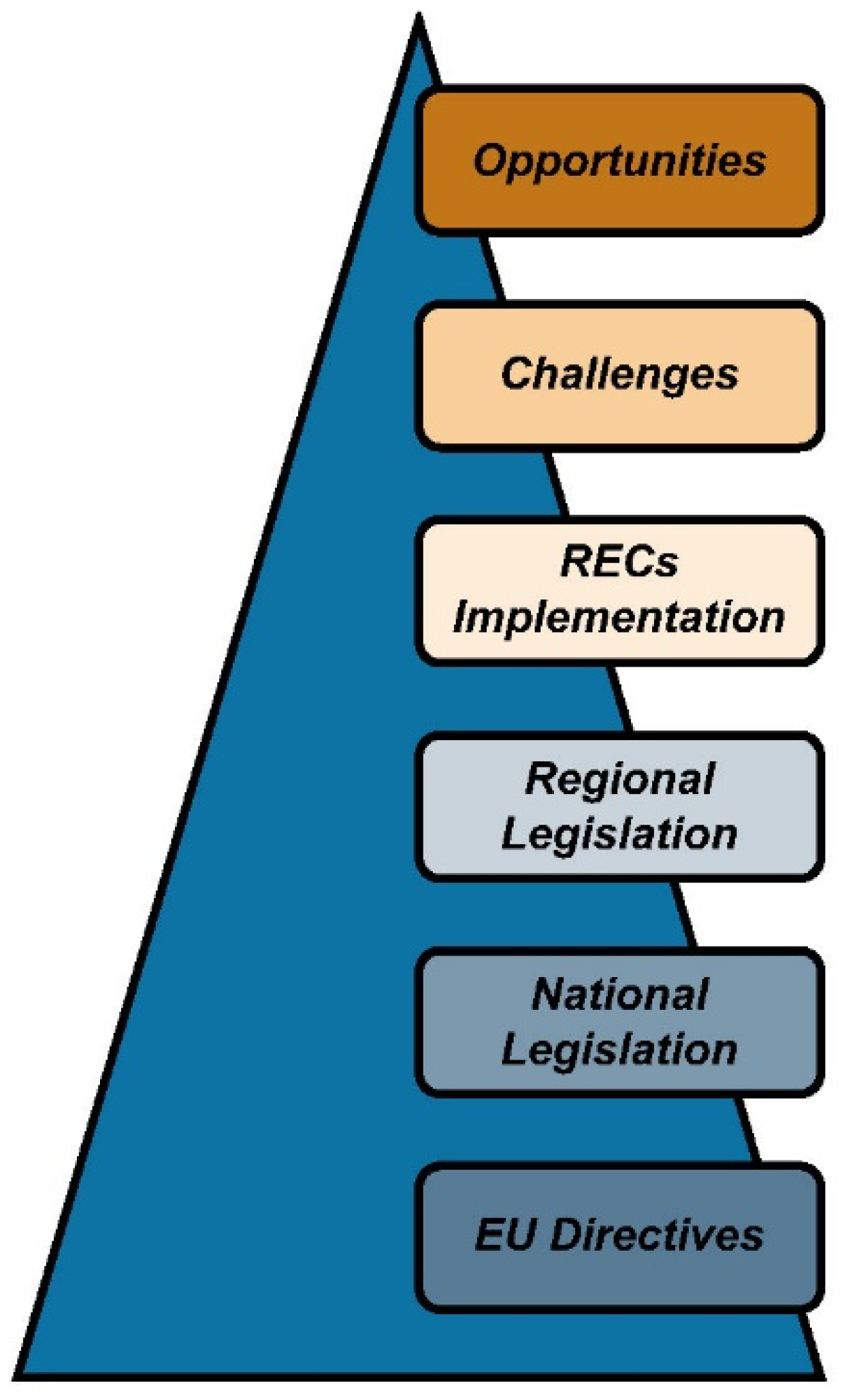

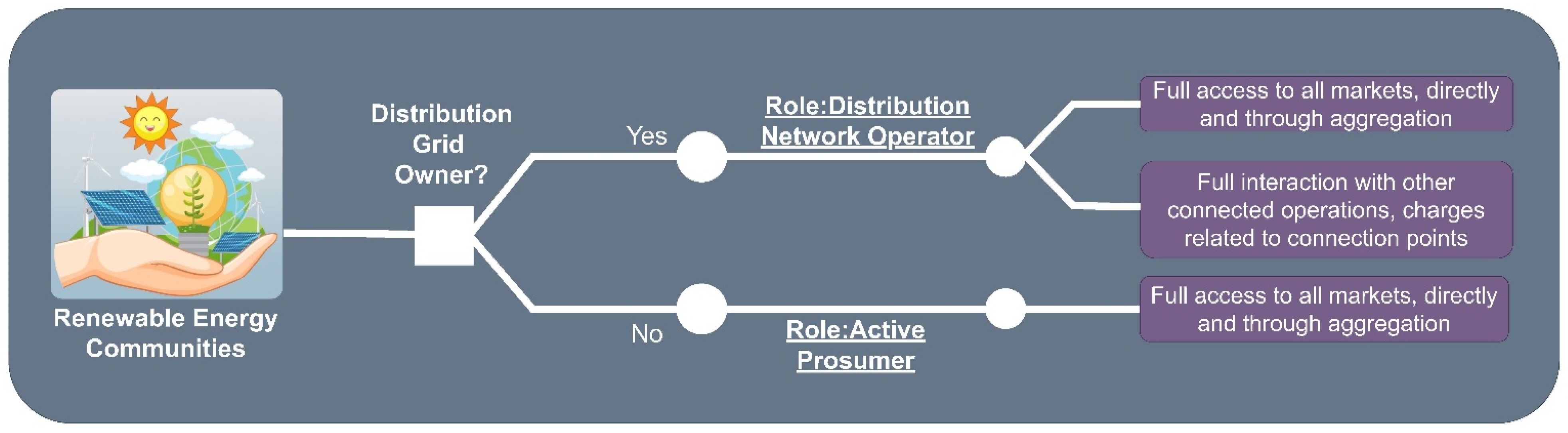

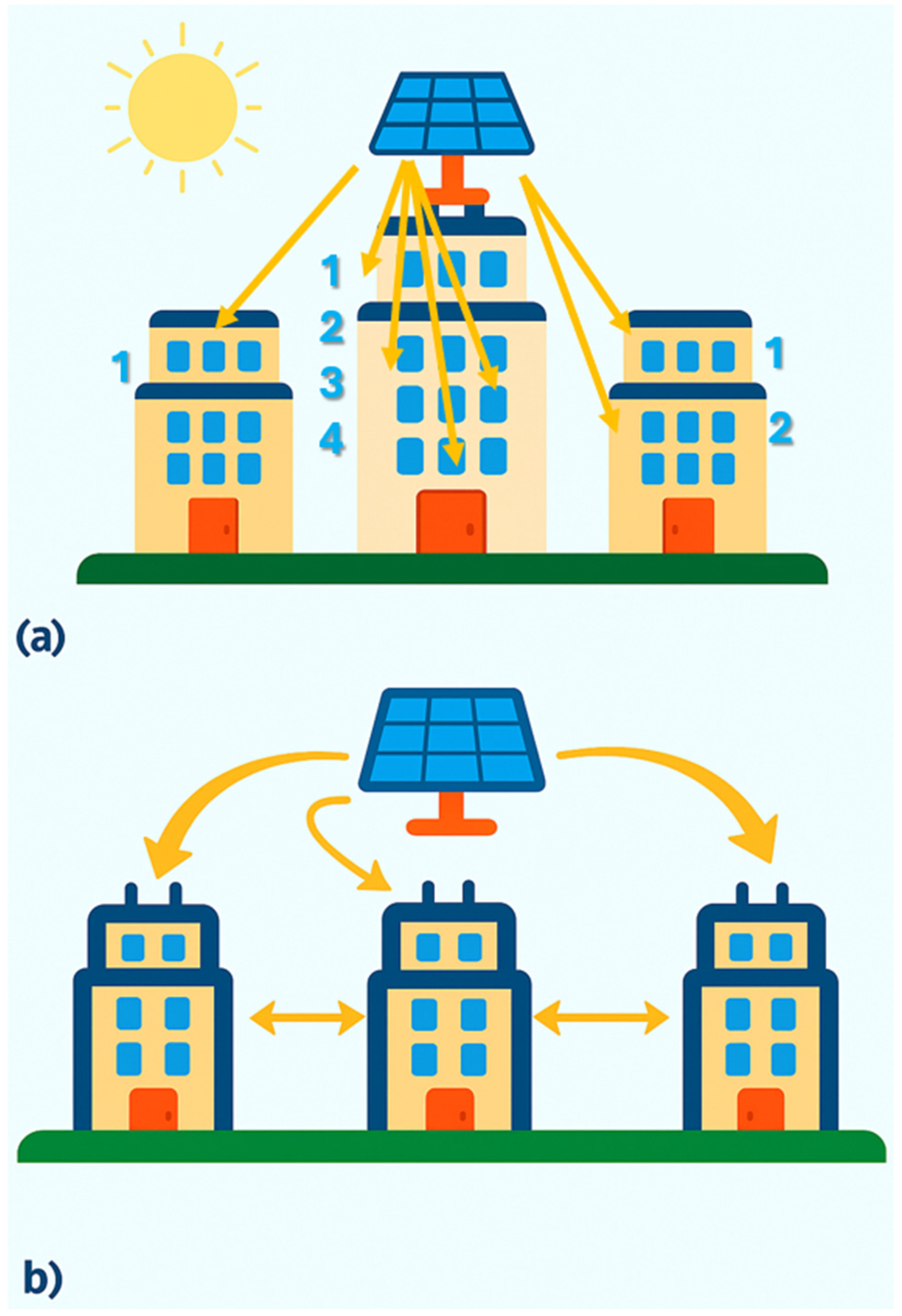

3. Renewable Energy Communities in Italy

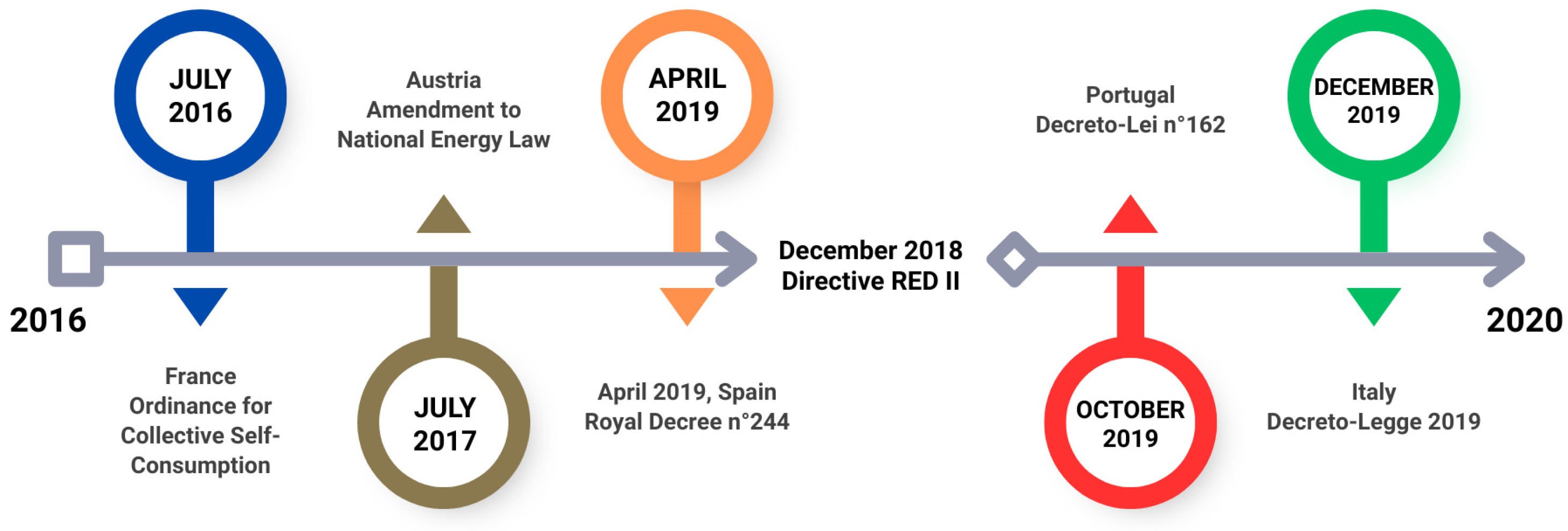

3.1. Regulations and Receipt of EU Directives

3.2. Legislative Framework and Implementation in Italy

3.2.1. European Union Directives and Italian Adaptation

Legislative Decree 199/2021

Final Directives Approved in 2024

3.2.2. Regional and Local Legislation

- Emilia-Romagna:

- Lombardy:

- Tuscany:

- Sardegna:

- Umbria:

| Region | Specific Measures | Examples of Implementation |

|---|---|---|

| Emilia Romagna | Financial incentives, technical support, regulatory facilitation | REC projects in Bologna, Modena |

| Lombardy | Grants for feasibility studies, support for pilot projects | REC initiatives in Milan, Brescia |

| Tuscany | Integration of RECs in regional energy plans, public awareness campaigns | REC projects in Florence, Pisa |

| Sardegna | Public funding for REC development and collaboration between local municipalities and technical support organizations | REC in Ussaramanna involving 61 members and a 71 kW PV plant, and REC in Borutta with PV installations on public buildings such as the town hall and schools |

| Umbria | A bottom-up participatory approach, community engagement, and involvement in planning and support from academic institutions (e.g., University of Catania) | CommON Light project in Ferla with a 20 kW PV system funded by European Regional Development Funds |

3.3. Comparison with Other European Countries

| EU Country | EU Directive Transposal Status | Aggregation Forms | Number of RECs | Main Types of Renewable Energy Plants |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Germany | Good practice | Energy Cooperative; Microgrids; Positive Energy Districts | 4848 | wind power, bioenergy, solar PV |

| Netherlands | Good practice | Citizen Energy Communities; Microgrids; Positive Energy Districts | 987 | wind power, biogas |

| Denmark | Good practice | Citizen Energy Communities; Microgrids; Positive Energy Districts | 633 | wind power, biogas |

| Ireland | In progress | Renewable Energy Communities | 545 | |

| Austria | Good practice | Citizen Energy Communities; Renewable Energy Communities; Positive Energy Districts | 384 | wind power, biogas, solar PV |

| France | In progress | Renewable Energy Communities; Self-Consumption Collective Agreement; Microgrids; Positive Energy Districts | 343 | wind power, biogas, solar PV |

| Sweden | Substantial deficiencies | Renewable Energy Communities; Positive Energy Districts | 329 | wind power, solar PV, geothermal energy |

| Spain | In progress | Renewable Energy Communities; Positive Energy Districts | 235 | solar PV |

| Italy | Good practice | Renewable Energy Communities; Self-Consumption Collective Agreement | 198 | solar PV |

| Greece | In progress | Citizen Energy Communities | 168 | solar PV |

| Finland | Substantial deficiencies | Renewable Energy Communities; Self-Consumption Collective Agreement; Positive Energy Districts | 83 | wind power, hydro-power, bioenergy |

| Poland | Substantial deficiencies | Renewable Energy Communities | 82 | wind power, solar PV, geothermal energy |

| Luxembourg | In progress | Renewable Energy Communities | 66 | solar PV, bioenergy |

| Czech Republic | In progress | Renewable Energy Communities | 35 | wind power, solar PV |

| Slovakia | In progress | Renewable Energy Communities | 23 | hydro-power, wind power, solar PV, bioenergy |

| Lithuania | Substantial deficiencies | Renewable Energy Communities | 19 | wind power, solar PV |

| Croatia | Substantial deficiencies | Energy Cooperative; Renewable Energy Communities | 12 | wind power, solar PV |

| Portugal | In progress | Local Energy Communities; Positive Energy Districts | 11 | solar PV |

| Slovenia | In progress | Renewable Energy Communities | 8 | solar PV |

| United Kingdom | Good practice | Renewable Energy Communities; Self-Consumption Collective Agreement; Microgrids | 400 | wind power, solar PV |

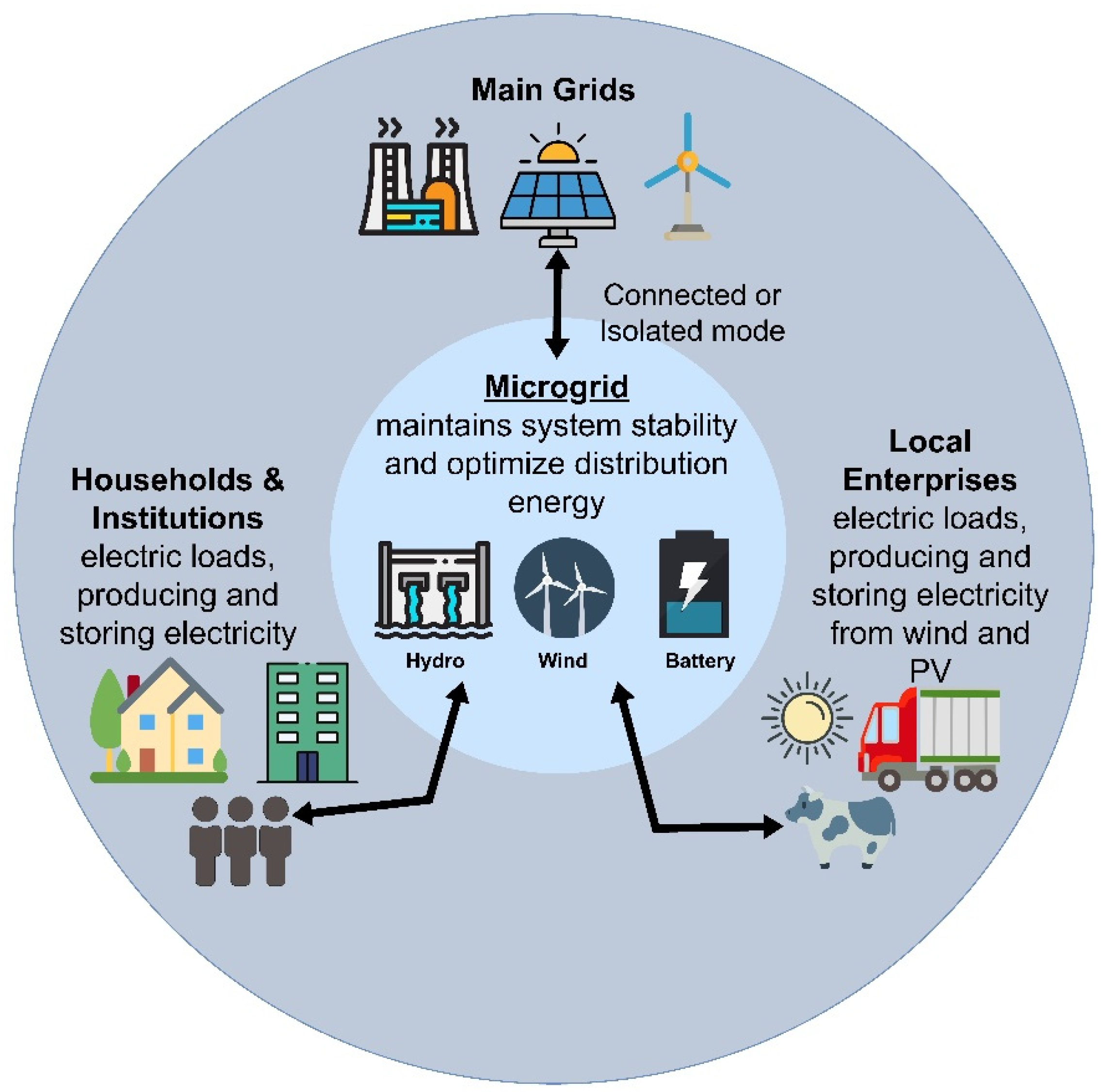

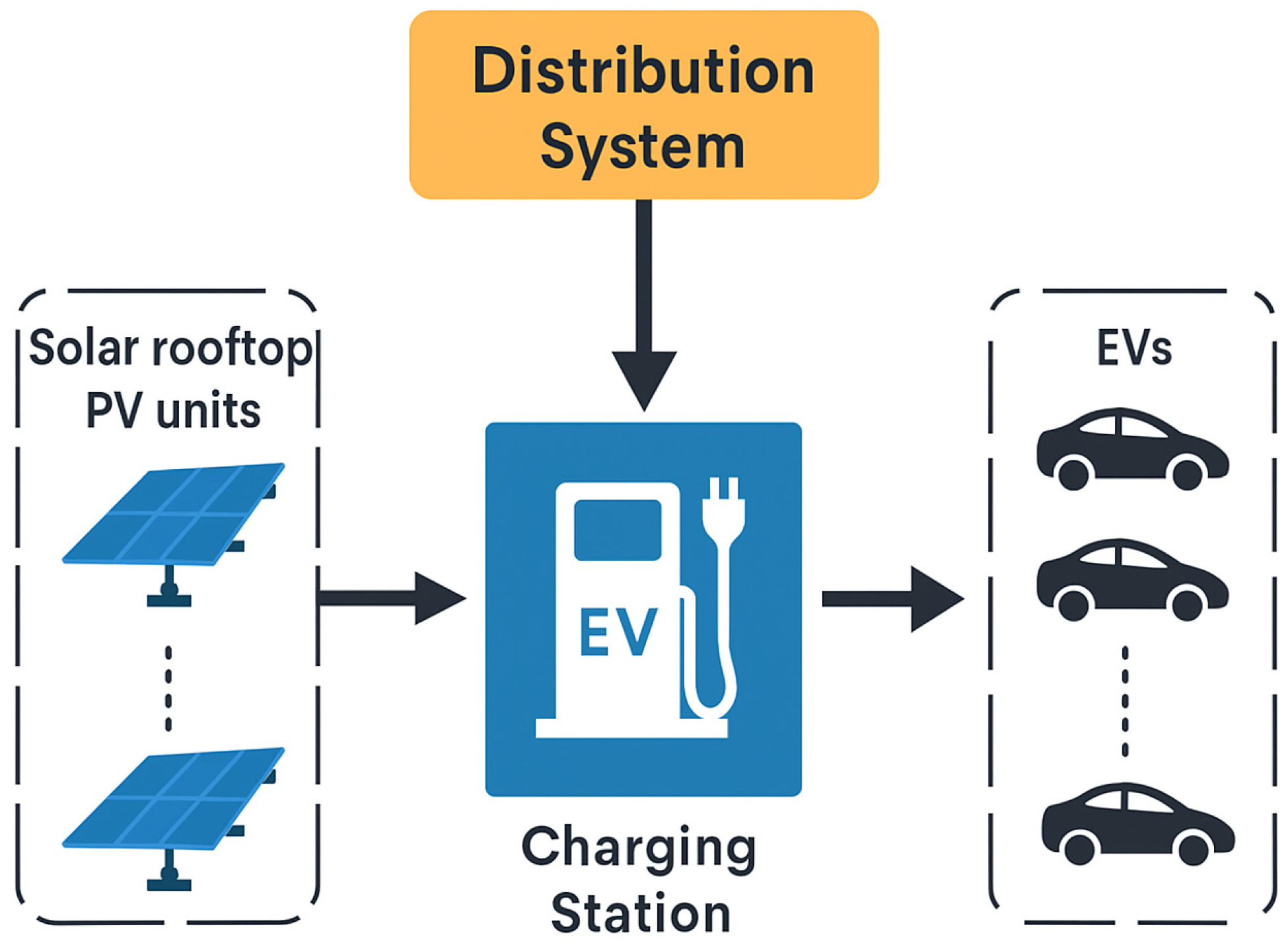

4. Photovoltaics, Electric Mobility, and RECs: Interaction with Power Systems and Electricity Market

4.1. Electric Mobility in Italy

4.2. Integration of Photovoltaics in Historic Contexts

4.2.1. Challenges of Integrating Photovoltaics in Historic Sites

4.2.2. Regulatory Framework and Guidelines

4.2.3. Technological Innovations for Seamless Integration

4.3. Benefits of Photovoltaic Integration in Historic Buildings

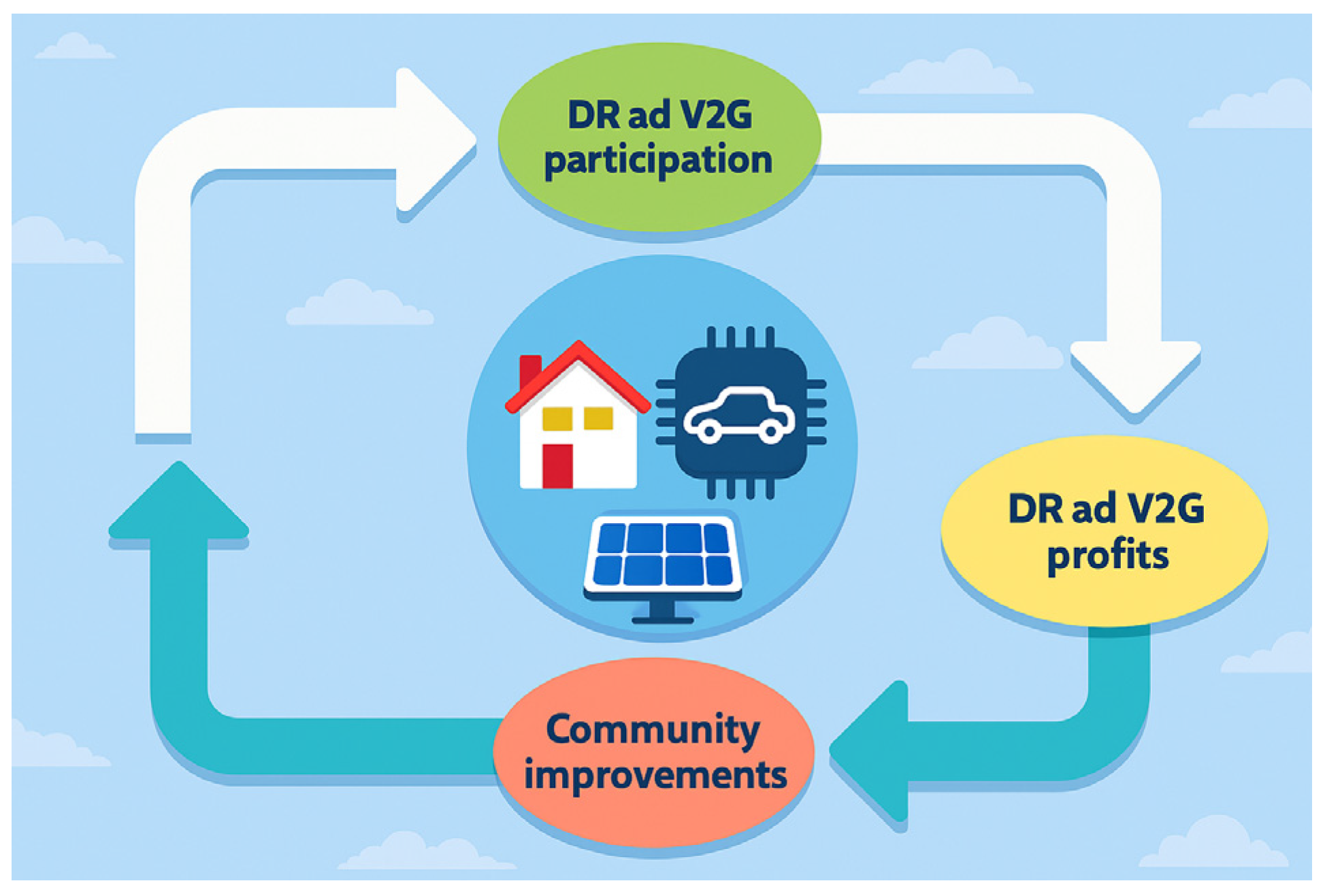

4.4. Synergies Between Electric Mobility and Renewable Energy Communities

4.4.1. The Role of Electric Vehicles in Renewable Energy Communities

4.4.2. Economic and Environmental Benefits of Integration

4.4.3. Technological Advancements and Smart Energy Management

4.4.4. Enhancing Energy Security and Resilience

5. Case Studies

5.1. Renewable Energy Communities in Naples (Southern Italy)

5.1.1. Results

5.1.2. Challenges and Opportunities

5.2. Energy City Hall, Magliano Alpi, Piedmont (Northern Italy)

5.2.1. Results

5.2.2. Challenges and Opportunities

5.3. CommON Light, Ferla, Sicily (Southern Italy)

5.3.1. Results

5.3.2. Challenges and Opportunities

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Neska, E.; Kowalska-Pyzalska, A. Conceptual design of energy market topologies for communities and their practical applications in EU: A comparison of three case studies. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 169, 112921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Silvestre, M.L.; Ippolito, M.G.; Sanseverino, E.R.; Sciumè, G.; Vasile, A. Energy self-consumers and renewable energy communities in Italy: New actors of the electric power systems. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 151, 111565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaouali, I.; Ben Jebli, M.; Ghazouani, T. Investigating the dynamic effects of service value added on CO2 emissions: Novel insights from a non-parametric approach. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 365, 121553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trevisan, R.; Ghiani, E.; Pilo, F. Renewable energy communities in positive energy districts: A governance and realisation framework in compliance with the Italian regulation. Smart Cities 2023, 6, 563–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods, 6th ed.; Sage: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, W.S. The logical structure of analytic induction. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1951, 16, 812–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starman, A.B. The case study as a type of qualitative research. J. Contemp. Educ. Stud. 2013, 16, 28–43. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbert, M.; Ruigrok, W.; Wicki, B. What passes as a rigorous case study? Strateg. Manag. J. 2008, 29, 1465–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauckner, H.; Paterson, M.; Krupa, T. Using constructivist case study methodology to understand community development processes. Qual. Rep. 2012, 17, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- European Union. Directive (EU) 2019/944 of the European Parliament and of the Council on common rules for the internal market for electricity. Off. J. Eur. Union 2019, 158, 125–199. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32019L0944 (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Italian Ministry for the Environment, Land and Sea. National Integrated Plan for Energy and Climate. 2021. Available online: https://www.mase.gov.it/portale/energia-e-clima-2030 (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- European Commission. Clean Energy for All Europeans. Off. J. Eur. Union 2019. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:52016DC0860 (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Italian Government. Decreto Legislativo 8 November 2021, n. 199—Attuazione della Direttiva (UE) 2018/2001 Sulla Promozione dell’uso dell’energia da Fonti Rinnovabili. Gazzetta Ufficiale 2021. Available online: https://www.normattiva.it/uri-res/N2Ls?urn:nir:stato:decreto.legislativo:2021-11-08;199 (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- De Laurentis, C.; Pearson, P.J. Policy-relevant insights for regional renewable energy deployment. Energy Sustain. Soc. 2021, 11, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavallaro, E.; Sessa, M.R.; Malandrino, O. Renewable energy communities in the energy transition context. Int. J. Energy Econ. Policy 2023, 13, 408–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowitzsch, J.; Hoicka, C.E.; van Tulder, F.J. Renewable energy communities under the 2019 European clean energy package–Governance model for the energy clusters of the future? Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2020, 122, 109489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunha, F.B.F.; Carani, C.; Nucci, C.A.; Castro, C.; Silva, M.S.; Torres, E.A. Transitioning to a low carbon society through energy communities: Lessons learned from Brazil and Italy. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2021, 75, 101994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Union. Directive (EU) 2018/2001 of the European Parliament and of the Council on the promotion of the use of energy from renewable sources. Off. J. Eur. Union 2018. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32018L2001 (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Italian Government. Decreto-Legge 30 Dicembre 2019, n. 162—Disposizioni Urgenti in Materia di Proroga di Termini Legislativi, di Organizzazione Delle Pubbliche Amministrazioni, Nonché di Innovazione Tecnologica. Gazzetta Ufficiale 2019. Available online: https://www.normattiva.it/uri-res/N2Ls?urn:nir:stato:decreto.legge:2019-12-30;162 (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Italian Government. Legislative Decree 199/2021. Off. Gaz. Ital. Repub. 8 December 2021. Available online: https://www.normattiva.it/uri-res/N2Ls?urn:nir:stato:decreto.legislativo:2021-12-08;199 (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Barbaro, S.; Napoli, G. Energy communities in urban areas: Comparison of energy strategy and economic feasibility in Italy and Spain. Land 2023, 12, 1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comodi, G.; Caresana, F.; Salvi, D.; Pelagalli, L.; Lorenzetti, M. Local promotion of electric mobility in cities: Guidelines and real application case in Italy. Energy 2016, 95, 494–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safarzadeh, H.; Ebrahimzadeh Sarvestani, M.; Enayati, M.; Di Maria, F. Hourly energy demand impacts of battery electric vehicle adoption in Italy: A grid simulation and policy analysis. Renew. Energy Focus 2026, 56, 100761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frieden, D.; Tuerk, A.; Neumann, C.; D’Herbemont, S.; Roberts, J. Collective Self-Consumption and Energy Communities: Trends and Challenges in the Transposition of the EU Framework; COMPILE Project Report; REScoop: Graz, Austria, 2020; Available online: https://share.google/FH1Be20etrZoeHttx (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Eder, J.M.; Mutsaerts, C.F.; Sriwannawit, P. Mini-grids and renewable energy in rural Africa: How diffusion theory explains adoption of electricity in Uganda. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2015, 5, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallah, N.; Fitzpatrick, C.; Killian, S.; Johnson, M. End-of-life electric vehicle battery stock estimation in Ireland through integrated energy and circular economy modelling. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 174, 105753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasqui, M.; Felice, A.; Messagie, M.; Coosemans, T.; Bastianello, T.T.; Baldi, D.; Carcasci, C. A new smart batteries management for renewable energy communities. Sustain. Energy Grids Netw. 2023, 34, 101043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frieden, D.; Tuerk, A.; Antunes, A.R.; Athanasios, V.; Chronis, A.G.; d’Herbemont, S.; Gubina, A.F. Are we on the right track? Collective self-consumption and energy communities in the European Union. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Yu, H.; Peng, Z.; Feng, Y. Planning community energy system in the industry 4.0 era: Achievements, challenges and a potential solution, renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 78, 710–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ARERA TIAD—Testo Unico per l’Autoconsumo Diffuso, Resolution 727/2022/R/eel. 2022. Available online: https://www.arera.it/it/docs/22/727-22.htm (accessed on 21 December 2024).

- Zhu, Y.; Salvalai, G.; Zangheri, P. Italian renewable energy communities: Status and prospect development analysis. Energy Build. 2025, 348, 116404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministero dell’Ambiente e della Sicurezza Energetica, Piano Nazionale Integrato per l’Energia e il Clima (PNIEC). 2023. Available online: https://www.mase.gov.it/portale/-/pubblicato-il-testo-definitivo-del-piano-energia-e-clima-pniec- (accessed on 14 October 2024).

- Cirone, D.; Bruno, R.; Bevilacqua, P.; Perrella, S.; Arcuri, N. Techno-economic analysis of an energy community based on PV and electric storage systems in a small mountain locality of South Italy: A case study. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutani, G.; Todeschi, V.; Tartaglia, A.; Nuvoli, G. Energy communities in Piedmont region (IT): The case study in Pinerolo territory. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Telecommunications Energy Conference (INTELEC), Torino, Italy, 7–11 October 2018; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2018; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DECRETO CACER e TIAD—Regole Operative per L’accesso al Servizio per L’autoconsumo Diffuso e al Contributo PNRR. 2024. Available online: https://www.mase.gov.it/portale/documents/d/guest/20250715_allegato_1_ro_cacer_rev2dggefim_clean_final-pdf (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Fioriti, D.; Frangioni, A.; Poli, D. Optimal sizing of energy communities with fair revenue sharing and exit clauses: Value, role and business model of aggregators and users. Appl. Energy 2021, 299, 117328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cielo, A.; Margiaria, P.; Lazzeroni, P.; Mariuzzo, I.; Repetto, M. Renewable energy communities business models under the 2020 Italian regulation. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 316, 128217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayat, M.A.; Shahnia, F.; Shafiullah, G.M.; Samu, R. Homogenising the design criteria of a community battery energy storage for better grid integration. Sustainability 2022, 14, 733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanke, F.; Lowitzsch, J. Empowering vulnerable consumers to join renewable energy communities towards an inclusive design of the clean energy package. Energies 2020, 13, 1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnani, N.; Vaona, A. Regional spillover effects of renewable energy generation in Italy. Energy Policy 2013, 56, 663–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belloni, E.; Fioriti, D.; Poli, D. Optimal design of renewable energy communities (RECs) in Italy: Influence of composition, market signals, buildings, location, and incentives. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2024, 235, 110895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belloni, E.; Fioriti, D.; Poli, D.; Tumiati, A. Electric mobility integrated in renewable energy communities: Technical/economic modelling and performance analysis. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 22nd Mediterranean Electrotechnical Conference (MELECON), Porto, Portugal, 25–27 June 2024; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 938–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellini, M.; D’Alpaos, C.; Pioletti, M.; Moretto, M. The Role of Regional Funding Policies in the Creation of Renewable Energy Communities in Italy. In AESOP Annual Congress Proceedings (Paris); 2024; Volume 36, p. 59586. Available online: https://proceedings.aesop-planning.eu/index.php/aesopro/article/view/1498 (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Musolino, M.; Maggio, G.; D’Aleo, E.; Nicita, A. Three case studies to explore relevant features of emerging renewable energy communities in Italy. Renew. Energy 2023, 210, 540–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Juan-Vela, P.; Alic, A.; Trovato, V. Monitoring the Italian transposition of the EU regulation concerning renewable energy communities and the relevant policies for battery storage. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 425, 138937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belloni, E.; Ferrucci, T.; Fioriti, D.; Tumiati, A.; Poli, D. Global diffusion and key features of Energy Communities with a main focus on building loads modelling and management: A review. Appl. Energy 2025, 399, 126461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azarova, V.; Cohen, J.; Friedl, C.; Reichl, J. Designing local renewable energy communities to increase social acceptance: Evidence from a choice experiment in Austria, Germany, Italy, and Switzerland. Energy Policy 2019, 132, 1176–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dóci, G.; Gotchev, B. When energy policy meets community: Rethinking risk perceptions of renewable energy in Germany and the Netherlands. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2016, 22, 26–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taromboli, G.; Soares, T.; Villar, J.; Zatti, M.; Bovera, F. Impact of different regulatory approaches in renewable energy communities: A quantitative comparison of European implementations. Energy Policy 2024, 195, 114399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gjorgievski, V.Z.; Velkovski, B.; Minuto, F.D.; Cundeva, S.; Markovska, N. Energy sharing in European renewable energy communities: Impact of regulated charges. Energy 2023, 281, 128333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunelli, L.; Belloni, E.; Pigliautile, I.; Cardelli, R.; Pisello, A.L.; Cotana, F. A novel methodology for accessible design of multi-source renewable energy community: Application to a wooded area in central Italy. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2025, 165, 110496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoicka, C.E.; Lowitzsch, J.; Brisbois, M.C.; Kumar, A.; Camargo, L.R. Implementing a just renewable energy transition: Policy advice for transposing the new European rules for renewable energy communities. Energy Policy 2021, 156, 112435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- L’Europa delle Comunità Energetiche (In Italian). Available online: https://www.balcanicaucaso.org/cp_article/leuropa-delle-comunita-energetiche/ (accessed on 9 November 2025).

- Gabrielli, P.; Gazzani, M.; Martelli, E.; Mazzotti, M. Optimal design of multi-energy systems with seasonal storage. Appl. Energy 2018, 219, 408–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Share of Electricity Production from Solar—Our World in Data. 2025. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/share-electricity-solar?mapSelect=~ESP (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Lanjewar, T.R.; Mounica, M.; Rajpathak, B.A. Application of piecewise-smooth droop control in solar PV based electric vehicle charging station. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE Renewable Energy and Sustainable E-Mobility Conference (RESEM), Nagpur, India, 2–4 June 2023; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandora, M.A.; Ifrim, V.C.; Artiom, M. Battery balancing system for electric vehicles solar power assisted. In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Modern Power Systems (MPS), Cluj-Napoca, Romania, 21–23 June 2023; pp. 1–5. Available online: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/10187487 (accessed on 10 August 2024).

- Duan, C.; Wang, C.; Li, Z.; Chen, J.; Wang, S.; Snyder, A.; Jiang, C. A Solar Power-Assisted Battery Balancing System for Electric Vehicles. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrif. 2018, 4, 432–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battaglia, V.; Vanoli, L.; Zagni, M. Economic benefits of renewable energy communities in smart districts: A comparative analysis of incentive schemes for NZEBs. Energy Build. 2024, 305, 113911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battaglia, V.; Massarotti, N.; Vanoli, L. Urban regeneration plans: Bridging the gap between planning and design energy districts. Energy 2022, 254, 124239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Italian Government. Decree-Law 162/2019, “Milleproroghe Decree-Law”. Gazzetta Ufficiale 2019. Available online: https://www.normattiva.it/uri-res/N2Ls?urn:nir:stato:decreto.legge:2019-12-30;162 (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Brummer, V. Community energy—Benefits and barriers: A comparative literature review of community energy in the UK, Germany, and the USA. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 94, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anna, Z.; Mikolaj, S.; Andrzej, B. Cooperation of the process of charging the electric vehicle with the photovoltaic cell. In Proceedings of the 2018 Applications of Electromagnetics in Modern Techniques and Medicine (PTZE), Racławice, Poland, 9–12 September 2018; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2018; pp. 285–288. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, D.; Yuan, Z.L.; Bai, Z.; Wu, Z.; Chen, S.; Zhou, M. Optimal operation of geothermal-solar-wind renewables for community multi-energy supplies. Energy 2022, 249, 123672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceglia, F.; Esposito, P.; Faraudello, A.; Marrasso, E.; Rossi, P.; Sasso, M. An energy, environmental, management and economic analysis of energy efficient system towards renewable energy community: The case study of multi-purpose energy community. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 369, 133269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartolini, A.; Carducci, F.; Muñoz, C.B.; Comodi, G. Energy storage and multi-energy systems in local energy communities with high renewable energy penetration. Renew. Energy 2020, 159, 595–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisner, A.; Neumann, C.; Manner, H. Exploring sharing coefficients in energy communities: A simulation-based study. Energy Build. 2023, 297, 113447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casalicchio, V.; Manzolini, G.; Prina, M.G. From investment optimization to fair benefit distribution in renewable energy community modelling. Appl. Energy 2021, 310, 118447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Tang, H.; Xu, Y. Distributed cooperative optimal control of energy storage systems in a microgrid. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Power and Energy Society General Meeting (PESGM), Boston, MA, USA, 17–21 July 2016; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2016; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastore, L.M.; Basso, G.L.; Quarta, M.N.; de Santoli, L. Power-to-gas as an option for improving energy self-consumption in renewable energy communities. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2022, 47, 29604–29621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piazza, G.; Bracco, S.; Delfino, F.; Di Somma, M.; Graditi, G. Impact of electric mobility on the design of renewable energy collective self-consumers. Sustain. Energy Grids Netw. 2023, 33, 100963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angizeh, F.; Jafari, M.A. Pattern-based integration of demand flexibility in a smart community network operation. Sustain. Energy Grids Netw. 2024, 38, 101320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velkovski, B.; Gjorgievski, V.Z.; Markovski, B.; Cundeva, S.; Markovska, N. A framework for shared EV charging in residential renewable energy communities. Renew. Energy 2024, 231, 120897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Rezgui, Y.; Luo, Z.; Jiang, B.; Zhao, T. Simultaneous community energy supply demand optimization by microgrid operation scheduling optimization and occupant-oriented flexible energy-use regulation. Appl. Energy 2024, 373, 123922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanvettor, G.G.; Fochesato, M.; Casini, M.; Lygeros, J.; Vicino, A. A stochastic approach for EV charging stations in demand response programs. Appl. Energy 2024, 373, 123862. [Google Scholar]

- Zanvettor, G.G.; Casini, M.; Giannitrapani, A.; Paoletti, S.; Vicino, A. Optimal management of energy communities hosting a fleet of electric vehicles. Energies 2022, 15, 8697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connolly, D. EnergyPLAN Cost Database: Version 4; EnergyPLAN, 2018. Available online: https://www.energyplan.eu (accessed on 10 August 2024).

- Ahmed, A.; Ge, T.; Peng, J.; Yan, W.-C.; Tee, B.T.; You, S. Assessment of the renewable energy generation towards net-zero energy buildings: A review. Energy Build. 2022, 256, 111755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jank, R. Annex 51: Case studies and guidelines for energy-efficient communities. Energy Build. 2017, 154, 529–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piselli, C.; Salvadori, G.; Diciotti, L.; Fantozzi, F.; Pisello, A.L. Assessing users’ willingness-to-engagement towards net zero energy communities in Italy. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 152, 111627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backe, S.; Korpås, M.; Tomasgard, A. Heat and electric vehicle flexibility in the European power system: A case study of Norwegian energy communities. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2021, 125, 106479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.; Ali, A.; Ciocia, A.; D’Angola, A. Technological Elements behind the Renewable Energy Community: Current Status, Existing Gap, Necessity, and Future Perspective—Overview. Energies 2024, 17, 3100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastore, L.M.; Lo Basso, G.; Ricciardi, G.; de Santoli, L. Synergies between power-to-heat and power-to-gas in renewable energy communities. Renew. Energy 2022, 198, 1383–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISTAT. Enterprises. Available online: http://dati.istat.it/Index.aspx?QueryId=21145&lang=en (accessed on 10 August 2024).

| Criteria | Renewable Energy Communities Under RED II | Citizen Energy Communities, as Defined in IEMD |

|---|---|---|

| Eligibility |

| In principle, open to all types of entities |

| Primary Membership Purpose |

| “Community benefits”, including environmental, economic, or social advantages for shareholders/members or for places where it operates, as opposed to financial gains; membership is voluntary and available to all prospective members based on non-discriminatory standards |

| Ownership and control |

|

|

| Directive | Description | Key Provisions Relevant to RECs |

|---|---|---|

| RED II (2018/2001) [18] | Promotes the use of energy from renewable sources | Encourages member states to establish frameworks for RECs, supports prosumers, and ensures grid access |

| Electricity Market Directive (2019/944) [10] | Regulates the internal electricity market | Mandates member states to allow RECs to operate within their energy markets and supports local energy generation and consumption |

| Peak Power of the Plants | Incentive (EUR/MWh) | Increase in Premium Tariffs (EUR/MWh) |

|---|---|---|

| <200 kW | 80–120 * | 0 for southern regions |

| 200 kW–600 kW | 70–110 * | +4 for central regions |

| >600 kW and ≤1 MW | 60–100 * | +10 for northern regions |

| No. | Name of the REC | Town | Region | Number of People Involved | Players | Partnerships | Current Status | BU/TD | Technologies | Funds |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | GECO (Green Energy Community) | Pilastro-Roveri district (Bologna) | Emilia Romagna | The development area is divided into three sections: a residential zone with 7500 residents (including 1400 in social housing, or ACERT), a commercial zone with two shopping centers and an agri-food park, and an industrial zone with the Bologna-CAAB agri-food center. | Emilia-Romagna Region, Municipality of Bologna, Agenzia locale di Sviluppo Pilastro Distretto Nord Est, Centro Commerciale Pilastro, ACER Bologna, Centro Agroalimentare di Bologna-CAAB | Fondazione FICO, Bastelli HTS S.r.l., Nute Partecipazioni S.p.A., ZR Experience, FRI—Fashion Research Institute, AESS, University of Bologna, ENEA | Under implementation | Top down | 14 MW PV plant, storage system and 50 kW biogas plant | European funds |

| 2 | Condominio “Green” | Scandiano (Reggio Emilia) | Emilia Romagna | A total of 48 units (20 owned by individuals and 28 by the Scandiano Municipality) | Municipality of Scandiano, ACER Reggio Emilia, ART-ER S.c.p.a. | ENEA, University of Bologna, ENEL X | Under implementation | Top down | PV plants | Private funds |

| 3 | Comunità di Energia Rinnovabile (CER) Collinare del Friuli | San Daniele del Friuli (Udine) | Friuli Venezia Giulia | San Daniele School for Primary Students and the San Daniele Municipality | Municipality of San Daniele del Friuli, Friuli-Venezia Giulia Region (funding body) | Polytechnic of Turin, Comunità Collinare del Friuli | Implemented | Top down | 54.40 kW PV plants | Regional funds |

| 4 | Monticello Green Hill | Monticello Brianza (Lecco) | Lombardy | There are around 4000 people living in the region. A total of 12 individual consumers make up the energy community | Energy Saving Management Consultants S.p.A. | NO | Implemented | Top down | 10 kW PV plants | Private funds |

| 5 | Comunità Energetica Alpina di Tirano | Tirano, and Sernio (Sondrio) | Lombardy | 1200 families | Municipalities of Tirano and Sernio, Teleriscaldamento Cogenerazione Valtellina Valchiavenna Valcamonica (TCVVV S.p.A.), Reti Valtellina Valchiavenna (ReVV S.r.l.) | NO | Under implementation | Top down | Cogenerative district heating by biomass (20 MW), PV plants | Unspecified |

| 6 | Comunità Energetica “Solisca” | Turano Lodigiano (Lodi) | Lombardy | A small town with a population of around 1600 people. Nine homes, which will eventually number 23 in the parish, and nine municipal utilities make up the energy community. | Municipality of Turano Lodigiano, Sorgenia S.p.A. | NO | Implemented | Top down | 47 kW PV plants on the covered areas of the sports field and of the gym | Private funds |

| 7 | Comunità Energetica del Pinerolese | Cantalupa, Frossasco, Roletto, San Pietro Val Lemina, Scalenghe, and Vigone (Turin) | Piedmont | Unspecified | Municipality of Scalenghe, ACEA Pinerolese Industriale, Consorzio Pinerolo Energia | Polytechnic of Turin | Under implementation | Top down | 450 kW hydroelectric plant, biogas plant, PV plants | Public, private, and equity crowdfunding |

| 8 | Comunità Energetica Rinnovabile “Energy City Hall” | Magliano Alpi (Cuneo) | Piedmont | 2184 inhabitants of the small rural municipality of Magliano Alpi | Municipality of Magliano Alpi, Energy Center Lab of Polytechnic of Turin | Polytechnic of Milan, University of Bologna, University of Trento, University of Modena-Reggio Emilia, University of Udine | Implemented | Top down | 20 kW PV panels on the roof of the town hall | Public and private funds |

| 9 | Comunità Energetica “Nuove Energie Alpine” | Municipalities of the Maira and Grana valleys (Cuneo) | Piedmont | 22 municipalities (about 40,000 inhabitants) | Associazione “Comunità Energetica Valli Maira e Grana” (promoter), Municipalities of the Maira and Grana valleys, Azienda Cuneese dell’Acqua S.p.A. | Enerbrain S.r.l. (technical support) | Under implementation in three municipalities (Busca, Villar San Costanzo, Pradleves) | Top down | Hydroelectric plant, PV and biomass | Public and private funds |

| 10 | Comunità Energetica della Valle Susa (CEVS) | Valle Susa (Turin) | Piedmont | Unspecified | Unione Montana Valle Susa, Unione Montana Alta Valle Susa, Consorzio forestale Alta Val di Susa, ACSEL S.p.A., Cooperativa forestale La Foresta, Replant (startup) | NO | Under implementation | Top down | 2 MW PV plants, 7 MW biomass plant, solar heating | Public and private funds |

| 11 | Comunità Energetica Primiero-Vanoi | Canal San Bovo, Imer, Mezzano, Primiero San Martino di Castrozza, and Sagron Mis (Trento) | Trentino Alto Adige | The number of members of the energy community is 100 | Municipal Services Consortium Company S.p.A. (ACSM) | NO | Under implementation | Top down | 90 MW hydroelectric plant, 2 district heating plants fired by wood biomass, 1 MW PV plants | Public funds |

| 12 | Energia Agricola a km 0 | Municipalities of Veneto Region | Veneto | There are already 514 companies who are participating, including both electricity producers and customers that own renewable energy facilities. | ForGreen S.p.A., Coldiretti Veneto, Coldiretti Puglia | NO | Under implementation | Top down | PV plants | Private funds |

| 13 | CERossini | Montelabbate (Pesaro and Urbino) | Marche | There are around 7000 people living in the region. A total of 10 individuals make up the energy community: the “G. Rossini” School Institute (a prosumer), 6 individual households, and 3 businesses. | Municipality of Montelabbate | NO | Implemented | Top down | 15 kW PV plants | Public funds |

| 14 | Comunità Energetica Rinnovabile di Biccari | Biccari (Foggia) | Apulia | About 70 families | Municipality of Biccari | ARCA Capitanata (regional agency for public housing), èNOSTRA | Under implementation | Top down | PV plants | Public |

| 15 | Comunità Energetica di Roseto Valfortore | Roseto Valfortore (Foggia) | Apulia | There are 1066 people living in the region. A total of 30 individuals make up the energy community. | Municipality of Roseto Valfortore, Friendly Power S.r.l. | Creta Energie Speciali S.r.l. (spin-off enterprise from the University of Calabria) | Implemented | Top down | Installation of smart meters and nanogrids | Public funds |

| 16 | Comunità Energetica Rinnovabile e Solidale “Critaro” | San Nicola da Crissa (Vibo Valentia) | Calabria | There are 1253 people living in the region. A total of 15 households (prosumer) in the San Nicola da Crissa municipality (30 households when fully functioning) | Municipality of San Nicola da Crissa | 3E Environment Energy Economy S.r.l. | Implemented | Top down | 66.8 kW PV plants | Private funds with a tax deduction of 50% in the “Building renovation bonus”, fifteen-year fixed-rate bank loan |

| 17 | Comunità Energetica e Solidale di Napoli Est | San Giovanni a Teduccio (Naples) | Campania | The Fondazione Famiglia di Maria, 40 households in the San Giovanni a Teduccio neighborhood | Fondazione Famiglia di Maria, 3E S.r.l. (for the realization of the plant), Legambiente | Fondazione con il Sud | Implemented | Bottom up | 53 kW PV panels on the roof of the Fondazione Famiglia di Maria | Private funds |

| 18 | AMARES | Ripalimosani (Campobasso) | Molise | Number of members: three | Amaranto’s group, Società Cooperativa “A.RE.S.” A.r.l., “Amaranto Software Factory S.r.l.” (Amaranto’s group), Society “Energia Prima Services S.r.l.” (Amaranto’s group) | NO | Implemented | Bottom up | 37.15 kW PV plant | European funds |

| 19 | Comunità Energetica di Borutta | Borutta (Sassari) | Sardinia | Mountain town of 254 inhabitants | Municipality of Borutta | NO | Under implementation | Top down | PV plants in the city center (town hall, sport facilities, schools, museum, street lighting, etc.) | Unspecified |

| 20 | Comunità Energetica di Ussaramanna | Ussaramanna (Medio Campidano) | Sardinia | A total of 61 individuals, including those involved in various economic endeavors (such as a hair salon, a store, and the gas station “Onnis Ombretta & C. Plant”) | Municipality of Ussaramanna | Énostra (technical support) | Implemented | Top down | 71 kW PV plant | Public funds |

| 21 | Comunità Energetica Biddanoa E′ Forru | Villanovaforru (Medio Campidano) | Sardinia | A total of 34 members including 1 commercial activity (Funtana Noa hotel) | Municipality of Villanovaforru | Énostra (technical support) | Implemented | Top down | 44.3 kW PV plant | Public funds |

| 22 | CommON Light | Ferla (Syracuse) | Sicily | Municipality of Ferla, five citizens and a company | University of Catania, ENEA | NO | Implemented | Top down | 20 kW PV system | European Regional Development Funds (PO FESR Sicily 2014–2020) |

| 23 | Comunità Energetica e Solidale di Fondo Saccà | Messina | Sicily | Six inhabitants | Fondazione di Comunità di Messina | Fondazione con il Sud | Implemented | Bottom-up | PV plants | Public funds |

| 24 | Comunità Energetica Agricola di Ragusa | Ragusa | Sicily | Several farms of about 60 ha | Municipality of Ragusa, MACS S.r.l. | NO | Under implementation | Top down | 200 kW PV system | Public (regional) and private funds |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jawad Ul Hassan, M.; Belloni, E.; Faba, A.; Cardelli, E. Energy Communities, Renewables, and Electric Mobility in the Italian Scenario: Opportunities and Limitations in Historic Town Centers. Energies 2025, 18, 5999. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18225999

Jawad Ul Hassan M, Belloni E, Faba A, Cardelli E. Energy Communities, Renewables, and Electric Mobility in the Italian Scenario: Opportunities and Limitations in Historic Town Centers. Energies. 2025; 18(22):5999. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18225999

Chicago/Turabian StyleJawad Ul Hassan, Muhammad, Elisa Belloni, Antonio Faba, and Ermanno Cardelli. 2025. "Energy Communities, Renewables, and Electric Mobility in the Italian Scenario: Opportunities and Limitations in Historic Town Centers" Energies 18, no. 22: 5999. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18225999

APA StyleJawad Ul Hassan, M., Belloni, E., Faba, A., & Cardelli, E. (2025). Energy Communities, Renewables, and Electric Mobility in the Italian Scenario: Opportunities and Limitations in Historic Town Centers. Energies, 18(22), 5999. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18225999