A Holistic Framework for Optimizing CO2 Storage: Reviewing Multidimensional Constraints and Application of Automated Hierarchical Spatiotemporal Discretization Algorithm

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Technical constraints encompass subsurface policies and engineering limits designed to safeguard storage integrity and security. For example, pressure buildup during injection can induce mechanical stress on the caprock or reactivate faults and fractures, posing significant containment risks [16,17]. To mitigate these risks, operators embed such constraints into injection strategy design—often adopting conservative measures such as limiting injection rates or wellhead pressures—which can underutilize pore space and reduce overall storage capacity [18].

- Commercial constraints arise from long-term contractual obligations mandating consistent CO2 intake over project lifespans, often exceeding a decade. Storage operators commit to delivery agreements with capture facilities based on uninterrupted injection profiles that typically match the capture rate. Consequently, well control strategies—manual or otherwise—must align with these commercial commitments.

- Operational constraints stem from the physical and mechanical limitations of the injection infrastructure. Parameters such as surface facility capacity (e.g., brine or CO2 treatment) in brownfield developments, offshore throughput limitations, tubing diameter, and wellbore integrity define strict operational envelopes that further complicate the design of optimal injection strategies [18].

- Economic constraints introduce trade-offs between pressure management and project cost. While strategies such as brine extraction can enhance injectivity by reducing formation pressure, they entail significant capital and operating expenditures [19]. Minimizing unintended CO2 recycling is equally critical to maximize net storage and reduce costs, adding another layer of financial complexity.

- Regulatory constraints reflect the legal imperative to contain the CO2 plume within the permitted storage site. Any migration beyond these boundaries—whether toward the broader storage complex or outside it—triggers compliance violations and costly corrective actions as stipulated in the CO2 storage permit. Such outcomes can delay operations, increase financial burden, threaten permit revocation, and erode stakeholder confidence [12].

- (1)

- It systematically maps the multidimensional constraints—technical, commercial, operational, economic, and regulatory—that govern well control strategies in geological CO2 storage projects, with particular attention to how these constraints interact across spatial and temporal scales.

- (2)

- It introduces a novel computational framework, titled Automated Optimization of Well Control Strategies Through Dynamic Time–Space Discretization. This framework integrates reservoir engineering fundamentals with advanced optimization techniques to automate the design of well control strategies. It is adaptable to site-specific complexities and is designed to co-optimize CO2 storage capacity and overall field-scale performance. By enhancing injection efficiency under cost and commercial constraints, the framework enables operators to accommodate high-volume emitters and deliver economically viable, large-scale storage solutions.

- Automated and industry-ready integration: The framework automatically updates well control strategies in response to changing subsurface models, operational constraints or business priorities. Fully compatible with commercial reservoir simulators, it integrates seamlessly into existing industrial workflows, enabling deployment without disrupting established workflows.

- Dynamic adaptability to operational cadence: A hierarchical greedy optimization process runs over discretized time–space domains, accommodating any field management approach—from coarse, infrequent rate adjustments to fine, high-frequency well-by-well changes. This modular structure supports interruptible, resumable runs that align with actual operational decision cycles.

- Embedded, real-world constraints: Technical, operational, commercial, and economic limits are incorporated directly into the optimization logic, hard bounds, logical conditions, or penalized soft constraints—ensuring that every computed strategy is both computationally optimal and practically deployable.

2. Multidimensional Constraints in Well Control Strategies

2.1. Geological Storage Principles

2.2. Multidimensional Constraints in CO2 Storage Well Control Strategies

2.2.1. Technical Constraints: Subsurface

Pressure Build-Up and Geomechanical Complications

Geological Storage Security: Improving Residual and Solubility Trapping

2.2.2. Commercial Constraint: Constant Field Intake

2.2.3. Operational Constraint: Feasible Injection Rates and Well Control Adjustments

2.2.4. Economics Constraints

- (i)

- balancing brine production to control costs while preserving injectivity and integrity;

- (ii)

- minimizing CO2 recycling, which directly affects storage efficiency and operational expenditures.

Balanced Brine Production and Cost Optimization

Minimizing CO2 Recycling for Efficiency and Cost Reduction

2.2.5. Regulatory Constraint: Ensuring CO2 Containment Within Licensed Boundaries

2.2.6. Interconnection of Key Constraints in Well Control Strategies

- Injectivity versus containment and economics (e.g., recycling);

- Short-term performance versus long-term commercial deliverability;

- Operational feasibility versus infrastructure limitations.

3. Methodology: Optimization Framework

3.1. Optimization Architecture

3.2. Objective Functions

3.3. Core Optimization Algorithm: Modified Genetic Algorithm

3.4. Constraints

3.5. Key Anchors of the Framework

3.5.1. Automation & Industry Ready Integration

3.5.2. Dynamic Adaptability to Operational Cadence

3.5.3. Multidimensional Constraint: Matching Reality (Simulation to Field)

4. Case Study: Implementation & Results

4.1. Model Setup

4.2. Well Configuration and Operation

4.3. Optimization Constraints

- Within the reservoir simulator, acting directly on physical responses such as pressure and fluid flow;

- Within the optimization algorithm, shaping the evolution and selection of the control variables (i.e., injection rates).

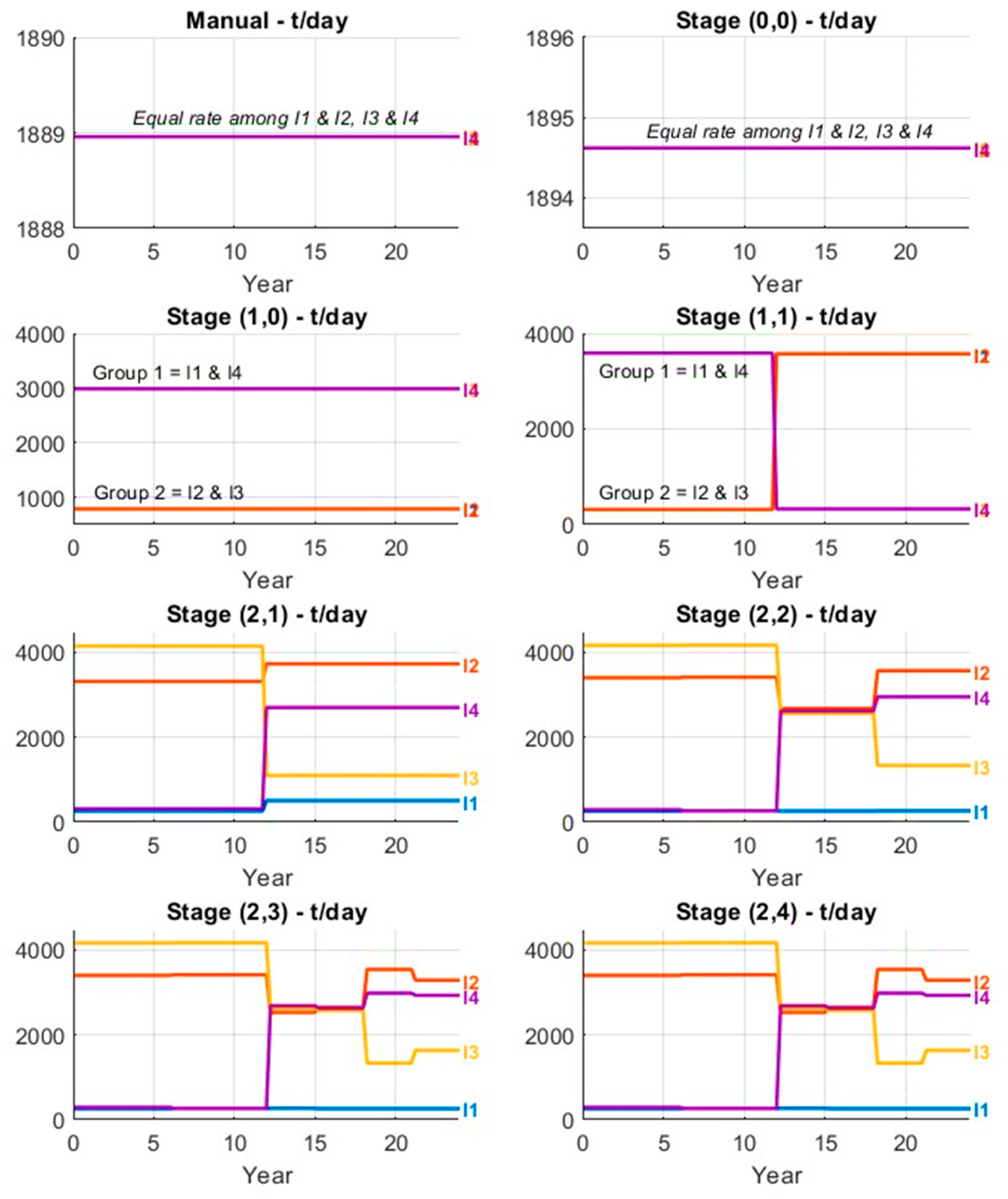

4.4. Hierarchical Refinement Strategy in Space and Time

- Spatial refinement is limited by the number of injectors, with a maximum of two spatial cuts allowing control at either the group or individual well level’

- Temporal refinement introduces up to four successive time cuts, each doubling the number of control intervals to enhance temporal resolution.

4.5. Results

4.5.1. Engineering Perspective

- (Field Gas Injection Total) represents the total CO2 injected over the project life;

- (Field Gas Production Total) represents the cumulative CO2 produced back to surface, either via intentional brine producers or breakthrough.

- ▪

- Maximize Absolute CO2 Retention (): ; this represents the net CO2 retained underground. Increasing FGIP improves storage capacity utilization and reservoir pore space efficiency, a primary technical performance indicator.

- ▪

- Maximize Relative CO2 Retention (Injection Efficiency): defined by . This metric measures how effectively injected CO2 is retained. Simply increasing FGIT is insufficient if accompanied by proportionally high FGPT. The objective rewards increased injection that is not offset by excessive recycling.

- ▪

- Minimize CO2 Recycling Volume: The penalty term discourages early and excessive CO2 breakthrough, promoting sweep efficiency and reducing operational challenges associated with surface CO2 handling and recycling.

- CO2 Retention (% of Injected Mass): Defined as FGIP/FGIT, this metric quantifies the fraction of injected CO2 that remains permanently stored. Higher retention reflects more efficient injection and improved sweep performance.

- Produced CO2 Volume (Million Tonnes): Represented by FGPT, this measures the cumulative CO2 recycled to the surface. Reducing this volume minimizes operational recycling costs and potential penalties, aligning with the objective function’s recycling penalty term.

- Storage Capacity Increase Over Manual (%): This is expressed relative to the baseline manual schedule results. The manual schedule serves as a practical engineering benchmark, balancing injectivity with acceptable recycling. This percentage indicates the proportional improvement in stored CO2 mass.

- Additional Stored Mass Over Manual (Million Tonnes): Complementing the percentage increase, this absolute measure shows the net extra CO2 stored due to optimization, highlighting tangible operational and commercial benefits.

- Field Gas Injection Rate (Mtpa): This constant rate, maintained over the project lifetime, represents the maximum sustainable injection capacity within reservoir and operational constraints, ensuring commercial feasibility.

- Actual Field Gas Injection Rate (Mtpa): After accounting for CO2 recycling and re-injection, this reflects the net effective injection volume delivered to emitters or clients, directly influencing the economic value of storage operations.

4.5.2. Financial Perspective

- —total CO2 permanently retained/stored in the reservoir over the project lifetime (Field Gas In-Place);

- —total CO2 injected regardless of retention (Field Gas Injected Total);

- —cumulative CO2 produced back to surface for recycling/re-injection (Field Gas Produced Total);

- —cumulative brine production requiring treatment/disposal (Field Water Produced Total);

4.5.3. Comparative Analysis: Engineering vs. Financial

5. Discussion, Conclusions and Final Remarks

- Constraint integration ensures that operational limits, safety margins, and commercial commitments are respected from the outset, reducing the risk of infeasible solutions emerging late in project planning.

- Hierarchical refinement allows the optimizer to progressively target the most sensitive control variables, achieving significant performance gains without the computational cost of full-resolution optimization from the start.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Friedlingstein, P.; O’SUllivan, M.; Jones, M.W.; Andrew, R.M.; Hauck, J.; Landschützer, P.; Le Quéré, C.; Li, H.; Luijkx, I.T.; Olsen, A.; et al. Global Carbon Budget 2024. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2025, 17, 965–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maguire, G. Asia’s Yawning Renewables Lead May Only Grow from Here. Reuters News, 15 January 2025. Available online: https://www.reuters.com/business/energy/asias-yawning-renewables-lead-may-only-grow-here-maguire-2025-01-15/ (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Paltsev, S.; Morris, J.; Kheshgi, H.; Herzog, H. Hard-to-Abate Sectors: The role of industrial carbon capture and storage (CCS) in emission mitigation. Appl. Energy 2021, 300, 117322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Zhang, M.; Jin, L.; Xu, M.; Li, J. Advancing carbon capture in hard-to-abate industries: Technology, cost, and policy insights. Clean Technol. Environ. Policy 2024, 26, 2077–2094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global CCS Institue. GLOBAL STATUS OF CCS 2024; Global CCS Institue: Melbourne, Australia, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Bukar, A.M.; Asif, M. Technology readiness level assessment of carbon capture and storage technologies. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2024, 200, 114578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEA. CCUS in Clean Energy Transitions; IEA: Paris, France, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Halliburton: Shelagh Baines, Kate Evans, Montse Portet, Benjamin Panting, Krzysztof Drop and GCSI: Aishah Hatta, Joey Minervini. “CO2 Storage Resource Catalogue–Main Report,” July 2024. Available online: https://www.ogci.com/ccus/co2-storage-catalogue/ (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Ismail, I.; Gaganis, V. Carbon Capture, Utilization, and Storage in Saline Aquifers: Subsurface Policies, Development Plans, Well Control Strategies and Optimization Approaches—A Review. Clean Technol. 2023, 5, 609–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajiabadi, S.H.; Bedrikovetsky, P.; Borazjani, S.; Mahani, H. Well Injectivity during CO2 Geosequestration: A Review of Hydro-Physical, Chemical, and Geomechanical Effects. Energy Fuels 2021, 35, 9240–9267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pernin, N.; Reiser, C.; Mueller, E. Integrated workflow for characterization of CO2 subsurface storage sites. In Proceedings of the Second International Meeting for Applied Geoscience & Energy, Houston, TX, USA, 28 August–1 September 2022; Society of Exploration Geophysicists and American Association of Petroleum Geologists: Houston, TX, USA, 2022; pp. 449–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Union. Directive 2009/31/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council on the Geological Storage of Carbon Dioxide; European Union: Luxembourg, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Directorate General for Climate Action EUROPEAN COMMISSION. Guidance Document 2: Characterisation of the Storage Complex, CO2 Stream Composition, Monitoring and Corrective Measures; European Union: Luxembourg, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Fotias, S.P.; Ismail, I.; Gaganis, V. Optimization of Well Placement in Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS): Bayesian Optimization Framework under Permutation Invariance. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 3528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, I.; Gaganis, V. Well Control Strategies for Effective CO2 Subsurface Storage: Optimization and Policies. Mater. Proc. 2023, 15, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutqvist, J.; Birkholzer, J.; Tsang, C.-F. Coupled reservoir–geomechanical analysis of the potential for tensile and shear failure associated with CO2 injection in multilayered reservoir–caprock systems. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2008, 45, 132–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, E.; Liu, S.; Li, Z.; Zhang, D.; Wu, H.; Di, Y. Geomechanical Analysis of Caprock and Fault Stability in a Full 3D Field Model During CO2 Geological Storage. In Proceedings of the 2024 Carbon Capture, Utilization, and Storage Conference, Tulsa, OK, USA, 11–13 March 2024; American Association of Petroleum Geologists: Tulsa, OK, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, J.A.; Chiaramonte, L.; Ezzedine, S.; Foxall, W.; Hao, Y.; Ramirez, A.; McNab, W. Geomechanical behavior of the reservoir and caprock system at the In Salah CO2 storage project. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 8747–8752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Lau, H.C.; Chen, Z. Extension of CO2 storage life in the Sleipner CCS project by reservoir pressure management. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2022, 108, 104814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Reedy, M.A. Introduction to Offshore Structures. In Offshore Structures; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haupt, R.L.; Haupt, S.E. Practical Genetic Algorithms; John Willey & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, D.E.; Holland, J.H. Genetic Algorithms and Machine Learning. Mach. Learn. 1988, 3, 95–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannis, S.; Lu, J.; Chadwick, A.; Hovorka, S.; Kirk, K.; Romanak, K.; Pearce, J. CO2 Storage in Depleted or Depleting Oil and Gas Fields: What can We Learn from Existing Projects? Energy Procedia 2017, 114, 5680–5690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, X.; Zhu, C. CO2 Storage in Deep Saline Aquifers. In Novel Materials for Carbon Dioxide Mitigation Technology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; pp. 299–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadian, E.; Jan, B.M.; Azdarpour, A.; Hamidi, H.; Othman, N.H.B.; Dollah, A.; Hussein, S.N.B.C.M.; Sazali, R.A.B. CO2 -EOR/Sequestration: Current Trends and Future Horizons. In Enhanced Oil Recovery Processes—New Technologies; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.-Y.; Ren, B.; Li, H.-Y.; Yang, Y.-Z.; Wang, Z.-Q.; Wang, B.; Xu, J.-C.; Agarwal, R. CO2 storage with enhanced gas recovery (CSEGR): A review of experimental and numerical studies. Pet. Sci. 2021, 19, 594–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbad, N.; Watson, M.; Emadi, H.; Eyitayo, S.; Leggett, S. Strategic Qualitative Risk Assessment of Thousands of Legacy Wells within the Area of Review (AoR) of a Potential CO2 Storage Site. Minerals 2024, 14, 383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torsæter, M.; Bello-Palacios, A.; Borgerud, L.K.; Nygård, O.K.; Frost, T.K.; Hofstad, K.H.; Andrews, J.S. Evaluating Legacy Well Leakage Risk in CO2 Storage. SSRN Electron. J. 2024, 5062896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gassara, O.; Estublier, A.; Garcia, B.; Noirez, S.; Cerepi, A.; Loisy, C.; Le Roux, O.; Petit, A.; Rossi, L.; Kennedy, S.; et al. The Aquifer-CO2Leak project: Numerical modeling for the design of a CO2 injection experiment in the saturated zone of the Saint-Emilion (France) site. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control. 2021, 104, 103196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Høyer, A.; Sandersen, P.; Andersen, L.; Madsen, R.; Mortensen, M.; Møller, I. Evaluating the chain of uncertainties in the 3D geological modelling workflow. Eng. Geol. 2024, 343, 107792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanakaki, E.M.; Ismail, I.; Gaganis, V. Accelerating Numerical Simulations of CO2 Geological Storage in Deep Saline Aquifers via Machine-Learning-Driven Grid Block Classification. Processes 2024, 12, 2447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanakaki, E.M.; Fotias, S.P.; Gaganis, V. Application of an Automated Machine Learning-Driven Grid Block Classification Framework to a Realistic Deep Saline Aquifer Model for Accelerating Numerical Simulations of CO2 Geological Storage. Processes 2025, 13, 2658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAl Hameli, F.; Belhaj, H.; Al Dhuhoori, M. CO2 Sequestration Overview in Geological Formations: Trapping Mechanisms Matrix Assessment. Energies 2022, 15, 7805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindeberg, E.; Wessel-Berg, D. Vertical convection in an aquifer column under a gas cap of CO2. Energy Convers. Manag. 1997, 38, S229–S234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McPherson, B.; Cole, B. Multiphase CO2 flow, transport and sequestration in the Powder River Basin, Wyoming, USA. J. Geochem. Explor. 2000, 69–70, 65–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Ozah, R.C.; Noh, M.H.; Pope, G.A.; Bryant, S.L.; Sepehrnoori, K.; Lake, L.W. Reservoir Simulation of CO2 Storage in Deep Saline Aquifers. SPE J. 2005, 10, 336–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juanes, R.; Spiteri, E.J.; Orr, F.M.; Blunt, M.J. Impact of relative permeability hysteresis on geological CO2 storage. Water Resour. Res. 2006, 42, W12418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metz, B.; Davidson, O.; De Coninck, H.C.; Loos, M.; Meyer, L. IPCC Special Report on Carbon Dioxide Capture and Storage; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Matter, J.M.; Kelemen, P.B. Permanent storage of carbon dioxide in geological reservoirs by mineral carbonation. Nat. Geosci. 2009, 2, 837–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Birkholzer, J.T.; Tsang, C.-F.; Rutqvist, J. A method for quick assessment of CO2 storage capacity in closed and semi-closed saline formations. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control. 2008, 2, 626–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Economides, M.J.; Ehlig-Economides, C.A. Sequestering Carbon Dioxide in a Closed Underground Volume. In Proceedings of the SPE Annual Technical Conference and Exhibition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 4–7 October 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicot, J.-P. Evaluation of large-scale CO2 storage on fresh-water sections of aquifers: An example from the Texas Gulf Coast Basin. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control. 2008, 2, 582–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birkholzer, J.; Zhou, Q.; Tsang, C. Large-scale impact of CO2 storage in deep saline aquifers: A sensitivity study on pressure response in stratified systems. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control. 2009, 3, 181–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szulczewski, M.; MacMinn, C.; Juanes, R. How pressure buildup and CO2 migration can both constrain storage capacity in deep saline aquifers. Energy Procedia 2011, 4, 4889–4896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonenko, Y.; Keith, D.W. Reservoir Engineering to Accelerate the Dissolution of CO 2 Stored in Aquifers. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2008, 42, 2742–2747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassanzadeh, H.; Pooladi-Darvish, M.; Keith, D.W. Accelerating CO2 Dissolution in Saline Aquifers for Geological Storage—Mechanistic and Sensitivity Studies. Energy Fuels 2009, 23, 3328–3336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nghiem, L.; Shrivastava, V.; Kohse, B.; Hassam, M.; Yang, C. Simulation and Optimization of Trapping Processes for CO2 Storage in Saline Aquifers. J. Can. Pet. Technol. 2010, 49, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafaei, M.J.; Abedi, J.; Hassanzadeh, H.; Chen, Z. Reverse gas-lift technology for CO2 storage into deep saline aquifers. Energy 2012, 45, 840–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmusson, K.; Rasmusson, M.; Tsang, Y.; Niemi, A. A simulation study of the effect of trapping model, geological heterogeneity and injection strategies on CO2 trapping. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control. 2016, 52, 52–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyewunmi, T. Offtake and Transportation Agreements for U.S. Carbon Capture Projects; Kleinman Center for Energy Policy: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- The Key Elements of CO2 Storage Agreements. Wikborg Rein. Available online: https://www.wr.no/en/news/the-key-elements-of-co2-storage-agreements?tab=about (accessed on 5 July 2025).

- Fattouh, B.; Muslemani, H.; Jewad, R. An Overview of CCS Business Models; The Oxford Institute for Energy Studies: Oxford, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- CLIMIT Secretariat. Standard Agreements for Purchase and Sale of Bulk Captured CO2 in CCS Chains. GASSNOVA. Available online: https://climit.no/en/project/standard-agreements-for-purchase-and-sale-of-bulk-captured-co2-in-ccs-chains/ (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Injection Strategies for CO2 Storage Sites. June 2010. Available online: https://www.scribd.com/document/916505105/2010-04-Injection-Strategies-for-CO2-Storage-Sites (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Okwen, R.; Dessenberger, R. A workflow for estimating the CO2 injection rate of a vertical well in a notional storage project. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control. 2024, 137, 104216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, P.; Morris, J.P.; Walsh, S.D.; Iyer, J.; Carroll, S. Effect of thermal stress on wellbore integrity during CO2 injection. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control. 2018, 77, 14–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilarrasa, V.; Rutqvist, J. Thermal effects on geologic carbon storage. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2017, 165, 245–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanin, E.; Garagash, I.; Boronin, S.; Zhigulskiy, S.; Penigin, A.; Afanasyev, A.; Garagash, D.; Osiptsov, A. Geomechanical risk assessment for CO2 storage in deep saline aquifers. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 2025, 17, 1986–2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buscheck, T.A.; Bielicki, J.M.; White, J.A.; Sun, Y.; Hao, Y.; Bourcier, W.L.; Carroll, S.A.; Aines, R.D. Pre-injection brine production in CO2 storage reservoirs: An approach to augment the development, operation, and performance of CCS while generating water. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control. 2016, 54, 499–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, S.T.; Jahediesfanjani, H. Estimating the potential costs of brine production to expand the pressure-limited CO2 storage capacity of the Mount Simon Sandstone. In Proceedings of the U.S. Association for Energy Economics and International Association for Energy Economics North American Conference, Tulsa, OK, USA, 23–26 September 2018; United States Association for Energy Economics/International Association for Energy Economics: Fort Worth, TX, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Schmelz, W.J.; Hochman, G.; Miller, K.G. Total cost of carbon capture and storage implemented at a regional scale: Northeastern and midwestern United States. Interface Focus 2020, 10, 20190065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santibanez-Borda, E.; Govindan, R.; Elahi, N.; Korre, A.; Durucan, S. Maximising the Dynamic CO2 storage Capacity through the Optimisation of CO2 Injection and Brine Production Rates. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control. 2019, 80, 76–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, C.; Liu, H.; Hou, Z.; Mehmood, F.; Liao, J.; Feng, W. A Review of CO2 Storage in View of Safety and Cost-Effectiveness. Energies 2020, 13, 600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartholomew, T.V.; Mauter, M.S. Energy and CO2 Emissions Penalty Ranges for Geologic Carbon Storage Brine Management. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 55, 4305–4313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajayi, T.; Gomes, J.S.; Bera, A. A review of CO2 storage in geological formations emphasizing modeling, monitoring and capacity estimation approaches. Pet. Sci. 2019, 16, 1028–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, C.; Pestman, P.; Carragher, P.; Constable, R. Long-term risk assessment of subsurface carbon storage: Analogues, workflows and quantification. Geoenergy 2024, 2, geoenergy2024-014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frattini, L.; Becattini, V.; Mazzotti, M. Main current legal and regulatory frameworks for carbon dioxide capture, transport, and storage in the European Economic Area. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control. 2024, 136, 104172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabir, M.A.; Ahmed, F.; Islam, M.; Ahmed, R. Python for Data Analytics: A Systematic Literature Review of Tools, Techniques, And Applications. Acad. J. Sci. Technol. Eng. Math. Educ. 2024, 4, 134–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, N.; Ostermeier, A. Completely Derandomized Self-Adaptation in Evolution Strategies. Evol. Comput. 2001, 9, 159–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blank, J.; Deb, K. Pymoo: Multi-Objective Optimization in Python. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 89497–89509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen, A.F.; Sandve, T.H.; Bao, K.; Lauser, A.; Hove, J.; Skaflestad, B.; Klöfkorn, R.; Blatt, M.; Rustad, A.B.; Sævareid, O.; et al. The Open Porous Media Flow reservoir simulator. Comput. Math. Appl. 2021, 81, 159–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goswami, S.; Chouhan, T.S. Artificial Lift to Boost Oil Production. Int. J. Eng. Trends Technol. 2015, 26, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benguigui, A.; Yin, Z.; MacBeth, C. A method to update fault transmissibility multipliers in the flow simulation model directly from 4D seismic. J. Geophys. Eng. 2014, 11, 025006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Constraint Category | Constraint Type | Description & Rationale | Enforcement Location | Value/Limit (Case-Specific) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Technical | Bottom-Hole Pressure | Limits BHP below fracture pressure to prevent reservoir and wellbore damage. Producer wells use BHP control to maintain reservoir pressure within safe limits. This indirectly limits pressure buildup in the reservoir below the BHP threshold set for injectors. | Reservoir Simulator | Max 6000 psi per injector Min 3000 psi per producer |

| Commercial | Constant Field Injection Rate | Enforces a fixed total CO2 injection volume over the project lifetime, reflecting contractual storage obligations and quota commitments. Implemented as a linear equality constraint. | Optimization Algorithm | Fixed total field intake/injection volume over 24 years |

| Operational | Feasible Injection Rate per Well | Ensures injection rates remain within mechanical and thermal limits related to tubing, well integrity, and operational safety. | Optimization Algorithm | Max 1.5 Mtpa per well |

| Economic | Field Brine Production | Limits brine production to surface facility capacity and disposal constraints, maintaining cost-effective voidage replacement and pressure management. | Reservoir Simulator | Max field production: 65,000 bbl./day. |

| Economic | Field CO2 Production (Breakthrough) | Penalizes CO2 recycling to reduce operational costs and improve storage efficiency; incorporated as a penalty term in the objective function. | Optimization Algorithm | Penalized through objective function |

| Regulatory | Plume Migration | Ensures the CO2 plume remains within licensed boundaries. Not explicitly enforced due to the closed-system model; in open systems, this would be actively constrained or penalized if the plume migrated beyond limits. | Implicit (Closed System) | Confined system; no out-of-bound migration |

| Refinement Stage (Space Cuts, Time Cuts) | Space Cuts | Time Cuts | Time Intervals | Decision Variables | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stage 0 (0,0) | 0 | 0 | 1 (0–24 yrs) | 1 | Global control: all injectors follow a single shared injection schedule (industry standard) |

| Stage 1 (1,0) | 1 | 0 | 1 (0–24 yrs) | 2 | Two-group control: Group 1 = I1 & I4; Group 2 = I2 & I3. |

| Stage 2 (1,1) | 1 | 1 | 2 (0–12, 12–24 yrs) | 4 | Time-varying control per group with low temporal granularity |

| Stage 3 (2,1) | 2 | 1 | 2 (0–12, 12–24 yrs) | 8 | Independent, time-varying control per well (I1–I4) |

| Stage 4 (2,2) | 2 | 2 | 4 (6-year intervals) | 16 | Higher-frequency, well-level control. |

| Stage 5 (2,3) | 2 | 3 | 8 (3-year intervals) | 32 | High-resolution control with well-level schedules segmented into 3-year intervals. |

| Stage 6 (2,4) | 2 | 4 | 16 (1.5-year interval) | 64 | Maximum resolution: full spatiotemporal optimization per well and time segment |

| Economic Elements | Value (€) | Unit | Source | Final Coefficient |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CO2 Storage Tariff | 50 | €/tonne | Porthos Tariff and EU Benchmarks (Average) | 2.61 €/Mscf |

| CO2 Injection Cost | 15 | €/tonne | Sleipner Project Injection Cost | 0.783 €/Mscf |

| CO2 Recycling and Re-injection Cost | 40 | €/tonne | High-end CCS cost estimates | 2.088 €/Mscf |

| Brine production & Treatment | 5 | €/m3 | Industry average disposal cost | 0.7949 €/bbl |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ismail, I.; Fotias, S.P.; Gaganis, V. A Holistic Framework for Optimizing CO2 Storage: Reviewing Multidimensional Constraints and Application of Automated Hierarchical Spatiotemporal Discretization Algorithm. Energies 2025, 18, 5926. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18225926

Ismail I, Fotias SP, Gaganis V. A Holistic Framework for Optimizing CO2 Storage: Reviewing Multidimensional Constraints and Application of Automated Hierarchical Spatiotemporal Discretization Algorithm. Energies. 2025; 18(22):5926. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18225926

Chicago/Turabian StyleIsmail, Ismail, Sofianos Panagiotis Fotias, and Vassilis Gaganis. 2025. "A Holistic Framework for Optimizing CO2 Storage: Reviewing Multidimensional Constraints and Application of Automated Hierarchical Spatiotemporal Discretization Algorithm" Energies 18, no. 22: 5926. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18225926

APA StyleIsmail, I., Fotias, S. P., & Gaganis, V. (2025). A Holistic Framework for Optimizing CO2 Storage: Reviewing Multidimensional Constraints and Application of Automated Hierarchical Spatiotemporal Discretization Algorithm. Energies, 18(22), 5926. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18225926