Abstract

This paper provides a comprehensive analysis of the development, implementation, and evolution of the circular economy indicator (CEI) in the context of hydroelectric turbine refurbishment over the past five decades. By systematically examining publications indexed in the Web of Science database between 1975 and 2025, the study traces the conceptual origins of the CEI, highlights methodological advances, and analyzes practical applications. The analysis focuses on key aspects such as material circularity, energy efficiency, including the share of renewable sources, and the extension of operational lifetime achieved through refurbishment. The paper also identifies persistent methodological gaps, in particular regarding the integration of social and governance dimensions, as well as the lack of standardization across projects, proposing strategies to increase the reliability and applicability of the indicator. The results provide guidance for integrating circular economy principles into hydroelectric refurbishment processes, outline good practices, and set priorities for future research oriented towards more holistic and multidimensional assessments of circularity.

1. Introduction

Hydroelectric turbine refurbishment is a crucial component in the drive towards sustainability, as it combines the technical need to increase the efficiency and durability of installations with the imperatives of the circular economy (CE), such as reducing the consumption of virgin materials, using renewable energy, and extending operational life cycles. Hydropower is generally classified as a renewable energy source due to its reliance on naturally replenished water flows; however, debates persist regarding its sustainability, particularly in relation to ecological impacts, material consumption, and infrastructure longevity [1,2,3]. Hydroelectric turbine refurbishment involves the deep transformation of their components in order to restore technical performance, extend operating life, and improve reliability under variable operating conditions, which raises numerous technical and material challenges. Turbines, especially the components exposed to the water flow (vanes, runners, nozzles, injectors), undergo constant degradation, such as erosion caused by sediments, chemical corrosion, suspended solids, cavitation, repeated mechanical stresses, and load and flow variations [4,5,6]. Integrating the CE perspective into hydroelectric turbine refurbishment highlights the importance of minimizing virgin material use, extending operational life, and optimizing energy efficiency, thus aligning technical interventions with broader sustainability goals [7,8].

Refurbishment interventions must begin with a clear diagnosis of the component’s condition, which involves visual inspection, non-destructive testing, hydraulic performance analyses, and numerical simulations. An example in this regard is given by the study conducted by Quaranta and Hunt [9] which discusses modernization strategies that include optimizing existing systems, adapting the runner or blades according to the current geometry of the exhaust pipes, replacing or strengthening worn components, and integrating modern control technologies [4,9,10,11,12].

The choice of materials also plays a central role. Studies in this direction have shown that stainless steels are frequently used due to their corrosion resistance, but their advanced degradation requires special coatings, surface treatments, or composite materials with superior properties [13,14,15,16]. In this regard, the study by Kashyzadeh et al. [17] brings valuable insights into how nanocoating can extend service intervals, reduce repair costs, and improve resistance to corrosion, wear, and erosion. The use of innovative materials has become a notable trend, as composites, advanced polymers, and superhydrophobic materials can reduce component weight, hydraulic head losses, and friction, thereby improving operational efficiency. For example, a recent study suggests that equivalent steel components can be replaced with composites that reduce weight by 50–80%, resulting in hydraulic losses of between 4 and 20%, depending on the type of material and fluids. However, initial costs, material availability, and compatibility with legacy infrastructure are often significant obstacles [18].

Refurbishment processes also include surface treatments, which can be applied after thermal spraying, through cermet coating techniques, nanolayers, or other methods designed to combat corrosion, erosion, and cumulative effects such as cavitation. In addition, delicate geometric adaptations are also an integral part of the reconditioning process; any modification to the vane profile, runner, nozzles, or exhaust components must be made to match the existing structural and hydraulic conditions. Modifications that ignore these restrictions can generate turbulence, increased viscosity, pressure losses, or additional stresses that can cause cracks, vibrations, or accelerated wear [19,20,21].

In addition to these aspects, economic taxation, material supply logistics, spare parts availability, downtime costs, and qualified maintenance personnel are factors that seriously influence refurbishment decisions. The choice between local repairs and complete replacement depends on the ratio of initial costs to long-term benefits, as well as the availability of advanced technology and materials in the region. Turbine refurbishment is not just a technical intervention, but involves holistic optimizations, such as mechanical engineering, materials engineering, hydraulics, digital control, economic evaluation, and sustainable operation [22,23,24].

In other words, the refurbishment of hydroelectric turbines aims to recover or improve performance through multiple interventions, to reduce losses and degradations associated with exploitation, and to manage materials and wear in a technically sound and sustainable manner. Success depends on the initial diagnosis, the materials used, the techniques applied, the compatibility with the infrastructure, and the availability of technological resources.

In this context, circular economy indicators appear as an integrative method that can quantify the evolution of the circularity of a complex system such as refurbishment. These indicators are essential analytical tools for assessing the performance of industrial processes from the perspective of efficient use of resources and reduction in environmental impact. In the context of hydroelectric turbine refurbishment, they provide a comprehensive framework through which the benefits of rehabilitation can be quantified and compared to complete replacement of equipment. Unlike traditional indicators, focused exclusively on energy efficiency or costs, circular economy indicators capture multiple dimensions of sustainability, reflecting both material and energy aspects, as well as social and governance impacts.

Circular economy indicators focuses on the material dimension of refurbishment, which refers to the proportion of materials reused, reconditioned, or from secondary sources in the rehabilitation process, as well as the reduction in the amount of waste generated. Thus, the indicators can quantify the ratio between the total mass of repaired components and that of new components, revealing the degree to which rehabilitation contributes to the conservation of primary resources. Complementarily, the energy dimension focuses on the assessment of the energy consumption associated with the repair, processing, and transport processes compared to the energy required to manufacture and install a new turbine. The relevance of this level is amplified by the integration of renewable sources, which allows the estimation of the climate benefits of refurbishment [25,26,27,28].

Another important dimension is the extended life of the equipment. Circular economy indicators can highlight the number of years added to the operating cycle of a turbine through rehabilitation and, implicitly, the resulting resource and energy savings. This approach allows for the justification of refurbishment investments in terms of long-term benefits and not just immediate costs [29,30,31].

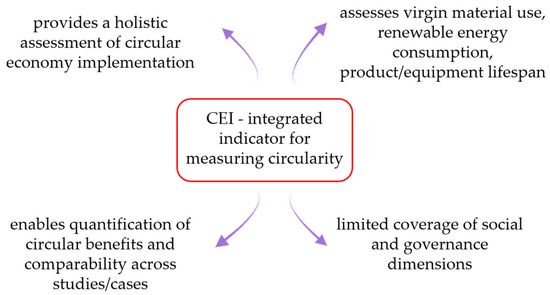

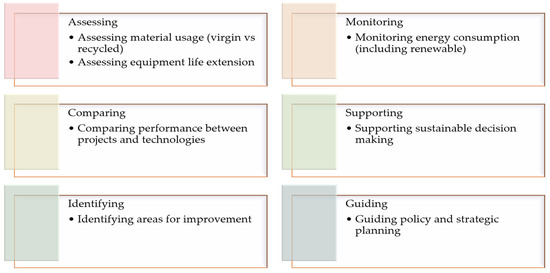

In the context of urgent transformations in production and consumption patterns, the circular economy has emerged as a key paradigm for achieving sustainable development [32]. Among the emerging approaches, the circular economy indicator (Figure 1) is gaining relevance and is being used to measure the evolution of circularity in a holistic manner. A critical, but insufficiently explored, aspect is the application of these indicators in complex processes, such as the refurbishment of hydroelectric turbines, where specific challenges arise related to material sustainability, energy consumption, and the extension of operational life cycles.

Figure 1.

Role of the CEI in the circular economy; CEI—circular economy indicator.

In the literature, the term CEI is used to describe metrics assessing circularity performance, often referred to as the circular economy index in some studies. In this study, we adopt the term CEI while circular economy indicators such as MCI (material circularity indicators), LCA (life cycle assessment), or MFA (material flow analysis) are discussed for comparison. While previous reviews have classified the CEI and discussed its general applications, this study specifically addresses the hydropower sector, focusing on turbine refurbishment processes. Unlike prior syntheses, it evaluates the relevance of indicators not only for material and energy efficiency but also for life extension and integration into decision-making frameworks. A brief comparison of scope and sector focus is provided in Table 1, highlighting both methodological differences and identified gaps. This allows for a clear identification of the specific contribution of this analysis to the field of hydropower plant renovation.

Table 1.

Methodological differences identified by current study.

The need for such a study derives from the fact that the hydropower sector, although based on a renewable source, involves technical processes with considerable impact on material resources and critical infrastructure. Turbine refurbishment is an essential step for increasing efficiency, reducing the ecological footprint, and extending the lifespan of installations, but its assessment from the perspective of the circular economy is still fragmentary. Therefore, the CEI can provide an integrative framework for quantifying the consumption of virgin materials, the renewable energy used, and the benefits generated by extending the life cycle, thus creating premises for a more robust sustainability assessment. However, the literature indicates the existence of significant methodological gaps, especially regarding the inclusion of social and governance dimensions [33,34,35]. In addition, the evolution of the CEI over the last five decades raises a number of fundamental scientific questions, such as: How has the CEI methodology changed since its introduction? To what extent does this indicator truly reflect the principles of the circular economy in the hydropower context? What are the advantages and limitations of its use in turbine refurbishment?

The main aim of this study is to examine hydroelectric turbine refurbishment through the lens of the circular economy, by assessing the applicability and methodological evolution of the circular economy indicator in this context. Specifically, the review traces the conceptual development of the CEI, evaluates its implementation in hydropower refurbishment, identifies methodological limitations, and formulates recommendations for enhancing its robustness and policy relevance.

The roadmap of this paper is structured as follows: Section 2 presents the methodology and search strategy; Section 3 summarizes the main findings on CEI applications in hydropower refurbishment; Section 4 discusses implications for decision-making and sustainable modernization; Section 5 concludes with practical and policy-oriented recommendations.

2. Methodology of Research

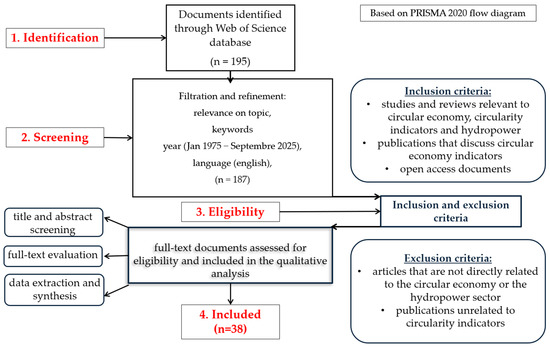

To ensure a systematic and comprehensive review of the literature, the Web of Science (WoS) database was selected as the main source due to its extensive journal coverage and multidisciplinary relevance. The search strategy was independently designed, and its reporting followed the PRISMA 2020 guidelines; it was designed to capture publications related to the development and application of the circular economy indicator in the context of hydropower turbine refurbishment processes. Database queries were formulated by combining key terms and controlled vocabulary terms to maximize the accuracy of the results. The search strategy was refined to ensure methodological accuracy. The final Boolean query was formulated as (“Circular Economy Indicator” OR “CEI”) AND (hydropower OR “turbine refurbishment”), applied to the Topic (TS—circular economy indicator) field in the Web of Science Core Collection, and restricted to article and review document types. The search was conducted on 12 September 2025, and the full set of records was exported as a file. These queries yielded a total of 195 articles. Because database hit counts are non-stationary and may vary with indexing updates, deduplication, or query refinements, the reported figure of 195 initial records corresponds to this date-specific snapshot. Future searches may yield different counts. The selection of studies was carried out independently by two evaluators, and the degree of concordance was verified by Cohen’s kappa coefficient, to ensure the transparency and reproducibility of the screening process regarding the energy transition and circular economy indicators.

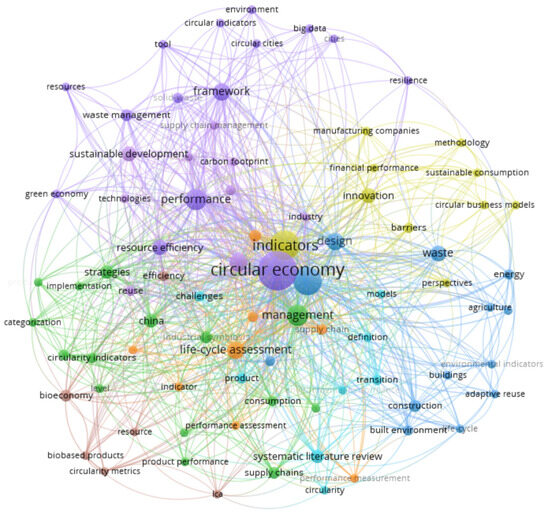

Subsequently, these publications were selected for keyword analysis to evaluate terms related to the circular economy; the documents were integrated into the VOSviewer software (version 1.6.20), setting a minimum threshold of two occurrences. Thus 84 keywords met these criteria (Figure 2). In the keyword analysis, a minimum occurrence threshold of two terms was established to eliminate informational noise associated with rare terms and to highlight recurring concepts with high thematic relevance in the literature on energy transition and circular economy indicators.

Figure 2.

Selection and co-occurrence analysis of terms related to the circular economy in VOSviewer software.

The methodology adopted in this study is summarized in Figure 3, which illustrates the main stages of the research process, from literature review to analysis of the CEI in hydroelectric turbine refurbishment. An adapted PRISMA 2020 flow diagram was used to structure and visualize the literature selection process. The adaptation was necessary to align the PRISMA framework with the specific scope of hydropower refurbishment and the size of the final corpus.

Figure 3.

Methodology of research.

The time interval was an extended one and it included publications published between January 1975 and September 2025, in order to track both the conceptual origins of the indicator and recent methodological developments and applications. An additional filter in this context was the language of publication (English), which brought a total of 187 publications. The time interval selected was deliberately extended to capture both the conceptual origins of circular economy approaches and the more recent emergence of circularity indicators and CEI frameworks after 2010. To ensure that early publications did not dilute the signal of more relevant recent literature, a sensitivity analysis was conducted focusing on the 2010–2025 interval. This additional analysis confirmed that the vast majority of CEI-related developments occurred after 2010, reinforcing the relevance of the recent time window.

Inclusion criteria in the analysis involved studies and reviews relevant to the circular economy, circularity indicators, and hydropower, respectively, and publications that directly or indirectly discuss CEI or other circular economy indicators in the context of renewable energy and refurbishment processes, as well as open access (OA) documents. The latter was not an inclusion criterion. However, OA publications were frequently retrieved due to their higher visibility and accessibility. This characteristic did not affect the inclusion process, which was strictly based on thematic and methodological relevance.

Exclusion criteria called for articles that were not directly related to the circular economy or the hydropower sector, respectively, and publications that only deal with technical aspects of turbine design or maintenance, unrelated to circularity indicators. By applying these criteria, the final selection included a number of 38 articles, and through their analysis, the aim was to obtain a relevant and robust corpus of literature, allowing for the critical evaluation of the CEI and its role in the refurbishment processes of hydroelectric turbines (Figure 3).

After applying the queries to the Web of Science database, all results were exported and centralized for processing. The selection process was carried out in three successive stages. In the first stage, a title and abstract screening was performed, and all identified publications were initially evaluated based on their title and abstract to determine relevance to the study objectives. Articles that did not refer to the circular economy, CEI, or hydroelectric refurbishment processes were eliminated. The second stage consisted of full-text evaluation, and the publications remaining after the first screening were read in full to confirm methodological and conceptual relevance, and information related to the evolution of CEI, scope, methodology used, and reported results was extracted. The third stage included data extraction and synthesis, and thus relevant data were analyzed to identify patterns of CEI evolution, methodological gaps, and opportunities for improvement.

This systematic approach ensures transparency and replicability, providing a solid basis for critical evaluation of the CEI and for formulating recommendations on integrating circularity into hydroelectric turbine refurbishment processes.

3. Results

3.1. The Evolution and Development of CEI

The concept of a circular economy emerged as a response to the limitations of the traditional linear economic model (extract–produce–consume–dispose), which leads to the depletion of natural resources and increasing pressure on the environment. The first ideas associated with circularity can be found in the 1960s and 1970s, with the emergence of works that warned of the incompatibility between unlimited economic growth and the planet’s finite resources [36,37,38,39].

The circular economy is a paradigm shift, a development model that aims to maintain the value of materials, products, and resources in the economy for as long as possible, while reducing waste generation and environmental impact. Unlike one-way recycling approaches, the circular economy proposes a systemic approach, which includes designing products for durability, repair and reuse, remanufacturing and refurbishment, as well as the recovery and reintegration of materials into productive cycles [40,41,42].

Implementing the circular economy brings a series of major benefits. Among these, we mention the ecological benefits from reducing the consumption of virgin resources, decreasing CO2 emissions, protecting biodiversity; the economic benefits from increasing resource efficiency, reducing production costs, stimulating innovation in product design and supply chain management; and the social benefits from creating green jobs and stimulating a resilient economy by diversifying sources of raw materials [43,44,45,46,47].

In recent years, the circular economy has become a central pillar of global sustainability policies aimed at transforming production and consumption models through integrated strategies, circularity standards, and progress indicators [43,48,49,50]. By implementing circularity principles in complex industrial sectors, such as energy and infrastructure, substantial improvements can be achieved, such as extending the life of equipment, reducing the carbon footprint, optimizing the use of materials, and reducing the costs associated with replacements. These benefits justify the need for robust measurement tools, such as the circular economy integrated indicators, that can allow for monitoring progress and comparability across different processes and industries [51,52,53,54,55].

The concept of the circular economy indicators emerged in response to the need to measure the degree of circularity in an integrative way, going beyond fragmented approaches based on unidimensional indicators. In the 1970s and 1980s, the first attempts to quantify circularity focused on recycling, reuse, and waste reduction rates as key indicators of the performance of material flows. These initiatives were part of broader debates on waste and resource management, which were gaining increased interest in response to the environmental challenges of the time [56]. For instance, in their study, Blomsma and Brennan [56] found that various resource and waste management strategies under the umbrella of the circular economy concept had taken on a new dimension and a new framework. Although some concepts did not represent an element of novelty, being framed within the set of methods, indicators, and methodologies of the circular economy, they drew attention to their importance, implicitly supporting their application in order to extend the life of resources.

Later, with the popularization of the circular economy as both a theoretical and political paradigm, the scientific literature deepened the evaluation tools, developing indicators capable of capturing the entire life cycle of products. Conceptually, processes such as recycling, reuse, remanufacturing, but also energy sustainability and renewable resources, were integrated, reflecting an orientation towards decoupling economic growth from resource consumption [57].

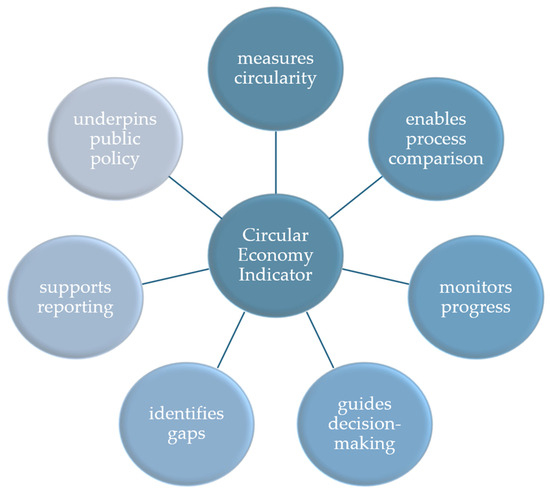

The CEI (Figure 4) represents a synthesis of these developments recorded over time during the evolution of the circular economy, offering a unified framework that correlates the use of virgin materials, the consumption of renewable energy, and the extension of the life span of products and equipment through refurbishment and remanufacturing processes [58]. Recent literature highlights the fact that the number of circular economy indicators has increased significantly, with over 60 indicators identified and grouped at micro, meso and macro levels. In this context, the CEI can be valuable because it integrates several dimensions of circularity into a single score, facilitating comparability between studies and industries [33,49,59].

Figure 4.

Role of the circular economy indicator in the circular economy context.

Another important aspect of the evolution of the CEI is the methodological refinement, from simple percentage calculations to weighted indicators, integrated into methodologies such as life cycle assessment (LCA) and material flow analysis (MFA), which allows the assessment of the impact over the entire life span of the analyzed system [33,34,49,60,61,62].

However, the literature highlights that the CEI remains predominantly technical, with limited coverage of social and governance dimensions, which reduces its ability to fully reflect the principles of the circular economy. Also, the lack of international standardization makes it difficult to compare results across regions and industrial sectors. Thus, the evolution of the CEI can be seen as a process of methodological maturation, from simple, material-focused indicators to complex analytical tools integrated into multi-criteria assessments. This transition creates the premises for the use of the CEI in critical sectors such as hydropower, where the potential for optimizing circularity is significant, and the resulting data can guide both technical decisions and public policies [63,64,65,66,67].

3.2. Circular Economy Indicators in Hydropower Turbine Refurbishment Processes

The refurbishment of hydroelectric turbines offers a unique opportunity to integrate circular economy principles into renewable energy infrastructure, optimizing resource use, extending equipment lifetime, and reducing environmental impact. In this context, circular economy indicators are essential tools for quantifying, monitoring, and guiding sustainable decisions throughout the rehabilitation process.

A first important category is the material circularity indicators (MCI), which assess the degree of circularity of the materials used, measuring the proportion of recycled or reused components and materials in relation to virgin materials. These indicators provide information on the reduction in raw material extraction, waste reduction, and the associated environmental impact. This category also uses the concept of circular material use, which effectively quantifies the amount of materials reused in the refurbishment process. This indicator allows the monitoring of the progress of implementing the principles of the circular economy and provides a concrete measure of the materials that return to the productive circuit [68,69,70,71].

Energy circularity indicators measure the total energy consumption during the rehabilitation activities and the share of renewable energy used, being essential for assessing the contribution of the refurbishment to the energy sustainability objectives and for optimizing the performance of the equipment [4,72,73].

Another category is represented by lifecycle assessment indicators, which evaluate the extension of the service life of the turbines and their components following the refurbishment. These indicators provide information on the long-term resource savings and the reduction in greenhouse gas emissions. They are complemented by environmental impact indicators and measurements, which quantify the effects on the environment, and economic performance indicators, which measure the economic benefits of the reuse and remanufacturing of components [73,74,75,76].

Applicability of the CEI in Hydroelectric Turbine Refurbishment

The refurbishment process of hydroelectric turbines represents an essential step in maintaining the functionality and efficiency of the facilities, ensuring the continuity of renewable energy production and reducing the costs associated with the complete replacement of equipment [4,23]. Although hydropower is considered a clean source, reconditioning operations involve significant consumption of materials and energy, and their impact must be assessed from a sustainability perspective. In this context, the circular economy indicator can provide an integrative analysis framework, capable of objectively quantifying the degree of circularity associated with these processes [58,77,78] (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

The main functions and benefits of the circular economy indicator that can be brought to the refurbishment of hydroelectric turbines.

By applying the CEI, both the quantities of virgin materials used and the proportion of recycled or recovered materials can be assessed, thus providing a clear picture of resource efficiency. The indicator also allows the monitoring of energy consumption, with a focus on renewable energy used during operations, and highlights the benefits of extending the turbine lifetime, which contributes to reducing the carbon footprint and reducing pressure on natural resources. The use of integrated metrics, such as the CEI, facilitates the comparability of refurbishment projects carried out in different regions or technological contexts, contributing to the dissemination of good practices and to making decisions based on solid data [78,79,80]. However, the application of the CEI in the hydropower sector is not without challenges. Collecting the necessary data can be difficult, especially in the case of older infrastructures where information on material composition or maintenance history is not fully documented. In addition, the indicator, although complex, insufficiently integrates social and governance dimensions, which limits its ability to fully reflect the sustainability of processes. The lack of international standardization for the calculation of the CEI can lead to methodological differences between studies, reducing the comparability of results and their relevance for policy formulation.

Despite these limitations, there is interest in using a circular economy indicator in hydroelectric power plant modernization projects. The positive impact of refurbishment on extending the life of equipment is highlighted, as well as reducing the amount of virgin materials needed and optimizing energy consumption. These findings confirm that the CEI can be not only a theoretical assessment tool, but also a practical guide that supports decision-makers in choosing the most efficient technical and managerial solutions, thus contributing to strengthening the transition to a circular economy in the energy sector [66,81].

3.3. Gaps, Perspectives, and Recommendations for Future Research

While the general circular economy indicator provides a framework for assessing circularity, its direct application in hydropower turbine refurbishment requires sector-specific adaptation. This includes defining which parameters to measure, the methods for data collection at plant level, and how the CEI can be integrated with life cycle assessment (LCA) and multi-criteria decision analysis (MCDA) to support decision-making. Although the concept of the circular economy index represents an important step towards measuring circular performance, the literature indicates several gaps that limit its applicability in the field of hydropower turbine refurbishment. First, most existing studies focus on technical and environmental indicators, while social and governance dimensions are rarely included. This lack of a holistic approach reduces the relevance of the index in contexts where modernization decisions need to consider the impact on local communities, social acceptability, and long-term economic implications. Second, there is significant methodological diversity in the definition and calculation of the indicators, which makes it difficult to compare results across projects and regions. Standardizing the formulas, weights, and types of data used would be an essential step towards the validation and widespread use of this indicator [82,83,84].

From a future research perspective, it is necessary to develop unified methodological frameworks that integrate not only technical and environmental performance indicators, but also socio-economic and governance parameters. A promising direction would be to combine LCA with MCDA to generate a robust score [85,86]. Recommendations for future research include the development of comparative studies between rehabilitated and new plants to quantify the real circularity gains and carbon footprint reduction. It would also be beneficial to create a set of practical guides for hydropower companies, explaining how to implement the CEI in the planning, execution, and reporting processes. Strengthening a community of practice, through collaborations between academia, industry, and regulatory bodies would accelerate the adoption of this tool and allow its refinement based on field experiences [86,87,88,89,90]. Finally, a major strategic direction remains the integration of the CEI into public policies and financing mechanisms, so that the modernization of hydropower plants is evaluated not only in terms of energy efficiency, but also in terms of their contribution to the transition to a circular economy [87,91]. In Table 2 we have summarized the main gaps, limitations, and future perspectives related to circular economy indicators and their implementation in hydropower turbine refurbishment.

Table 2.

Gaps, limitations, and perspectives in the circularity of hydroelectric turbine refurbishment.

In Table 3 we propose a mini checklist with the main elements that should be collected and monitored in hydropower turbine refurbishment projects. The list includes material and energy consumption, environmental impact, component lifetime extension, social and governance aspects, data sources, and how to integrate the methodology into the LCA/MCDA framework, thus providing a practical guide for decision-makers.

Table 3.

Checklist for data collecting and monitoring in hydropower turbine refurbishment projects.

4. Discussion

The literature review indicates that the CEI is a promising tool for assessing the degree of circularity in hydroelectric turbine refurbishment processes, but their use remains fragmented and uneven. A first observation is that the currently available indicators focus predominantly on technical and environmental dimensions, such as virgin material consumption, renewable energy share, and CO2 emission reduction, which limits their ability to reflect the socio-technical complexity of modernization projects [82,100,101,102]. There is also a lack of consensus on the methods of calculation and data normalization, which generates large variations between published studies and hinders comparability at the national and international level [25,84,103].

Another relevant aspect in this context is the low adoption of the CEI in concrete refurbishment projects. Although projects such as RevHydro [104] have started to propose integrated methodologies to quantify circularity in the hydropower sector, there is still a gap between the theoretical development of indicators and their implementation in practice. This gap can be explained by the complexity of data collection at plant level, the lack of standardized protocols, and organizational resistance to the adoption of new assessment tools [49,105,106]. For refurbishment projects, key metrics include material inputs (virgin vs. recycled), energy consumption during refurbishment, water usage, emissions, and expected lifetime extension of turbines. Data can be sourced from maintenance records, equipment specifications, on-site measurements, and suppliers’ environmental declarations. Integrating these parameters within an LCA/MCDA framework allows assigning weights to environmental, economic, and social criteria, generating a robust composite CEI score to guide investment and technical decisions.

A key aspect is the enormous potential that digitalization can bring to this area. The use of technological processes (such as digital twins for turbine life cycle simulation, combined with IoT data collected in real time), could transform the CEI into a dynamic and predictive tool, capable of guiding maintenance decisions and investment planning. This would lead to a higher level of circular performance optimization and cost reduction in the long term [107,108,109,110,111,112].

On the other hand, a brief and critical comparison with other industrial sectors shows that the hydropower sector is still at an early stage of circular economy integration. The automotive and electronics industries have already developed robust standards for assessing circularity and implemented large-scale remanufacturing schemes, suggesting that knowledge transfer from these areas could accelerate progress in the hydropower sector [113,114,115]. Furthermore, including social and governance dimensions in the CEI would provide a more complete perspective on the benefits and trade-offs associated with refurbishment, thus strengthening the legitimacy of investment decisions in the eyes of stakeholders [116,117]. To provide a clearer overview of how circular economy indicators are applied across some of the most important renewable energy sectors, a short comparative summary is presented below (Table 4). This synthesis enhances the understanding of cross-sectoral patterns, highlights common benefits, and identifies specific focuses for each energy source.

Table 4.

Overview of how circular economy indicators are applied across different renewable energy sectors.

Beyond industrial examples, relevant parallels can also be drawn with other renewable energy technologies, which provide valuable insights into scaling up circularity practices in hydropower refurbishment. In addition to comparisons with other industrial sectors, it is also relevant to highlight differences and commonalities between hydropower refurbishment and other renewable energy fields. For instance, in wind energy, blade remanufacturing initiatives have advanced rapidly in recent years, supported by clear standardization pathways and well-defined end-of-life strategies, which enable the recovery of materials and the reduction in lifecycle impacts [118,119,120]. Similarly, in pumped-storage hydropower, lifetime extension projects have been systematically integrated with predictive maintenance and performance optimization strategies, resulting in measurable improvements in asset circularity [121,122,123]. These examples show that cross-sectoral knowledge transfer and the adoption of standardized circularity protocols can significantly accelerate the maturity of CEI applications in hydropower refurbishment, while preserving the specificities of this sector in terms of infrastructure scale, regulatory context, and operational lifetime.

Overall, the CEI can be a valuable tool, but it is at a stage of partial maturity, requiring both methodological refinements and a clear strategy for integration into practice. It is evident that future research should be oriented towards standardization, digitalization, and multidimensionality so that these tools can truly support the transition to a circular economy in the hydropower sector.

5. Conclusions

The present study highlights that the CEI can be a key tool for quantifying circular performance in hydroelectric turbine refurbishment processes. The analysis of their evolution shows a clear transition from unidimensional indicators, focused on recycling and reuse, to complex methodological frameworks, capable of capturing the entire life cycle of equipment and material flows. This conceptual maturation provides the premises for a more rigorous assessment of the impact of hydrotechnical rehabilitations on resource consumption and long-term sustainability.

The applicability of the CEI in the hydropower sector may prove promising but is still limited by methodological heterogeneity and the lack of standardization of indicators. Research projects under development demonstrate the feasibility of integrating circular economy principles into plant modernization, but also the need for clear data collection and analysis protocols. Furthermore, the inclusion of social and governance dimensions remains underdeveloped, which may reduce the relevance of the results for decision-makers and affected communities.

In light of these findings, the main conclusion is that the CEI needs to evolve towards multidimensional, standardized, and digitalized tools, capable of providing real-time information and allowing comparisons between projects, regions, and technologies. The development of robust methodological frameworks, supported by digital technologies such as digital twins and IoT systems, could transform the CEI into a dynamic strategic management tool. At the same time, collaboration between academia, industry, and regulators is essential to accelerate the adoption and validation of this type of indicator.

Finally, the CEI has the potential to become a fundamental benchmark for the transition of the hydropower sector towards a circular economy. Its systematic implementation could not only optimize resource use and reduce environmental impact but also ensure better social acceptability and economic sustainability of refurbishment projects. Thus, this study contributes to the foundation of a research and action agenda, aimed at transforming circularity indicators from simple reporting tools into true drivers of strategic decisions in the field of renewable energy. Based on the findings, this study recommends that policymakers, regulators, and industry stakeholders implement specific economic and policy instruments to accelerate the circular transition of the hydropower sector. These include economic incentives, such as tax credits or green financing schemes, to encourage the use of secondary and advanced materials in turbine retrofits; another recommendation calls for regulatory frameworks that require standardized data collection and CEI-based performance reporting for retrofit projects. It also recommends implementing public–private partnerships that support innovation in digital monitoring and circular design practices, as well as including the CEIs in investment and licensing decisions, to ensure that funding and policy priorities align with measurable sustainability outcomes. Such coordinated measures can increase resource efficiency, reduce life cycle costs, and strengthen the socio-economic viability of hydropower retrofits. In this way, the CEI becomes not only a sustainability indicator, but also a decision-making support tool for steering energy policy and financing towards circularity and long-term resilience.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.L.R., E.S.L., L.-I.C., and R.A.M.; methodology, A.L.R., E.S.L., L.-I.C., G.M., M.B., S.F., L.S., and R.A.M.; software A.L.R., G.M., M.B., and S.F.; validation, A.L.R., E.S.L., L.-I.C., L.S., and R.A.M.; formal analysis, A.L.R., G.M., M.B., and S.F.; investigation, A.L.R., G.M., M.B., and S.F.; resources, E.S.L. and L.-I.C.; data curation, A.L.R., E.S.L., L.-I.C., G.M., M.B., S.F., L.S., and R.A.M.; writing—original draft preparation, A.L.R., E.S.L., L.-I.C., and R.A.M.; writing—review and editing G.M., M.B., S.F., and L.S.; visualization A.L.R., G.M., M.B., and S.F.; supervision, A.L.R., E.S.L., L.-I.C., L.S., and R.A.M.; project administration, A.L.R., E.S.L., and L.-I.C.; funding acquisition, L.-I.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Horizon Europe project Revolutionary Refurbishment for an Efficient and Eco-Friendly Hydropower—REVHYDRO, Grant Agreement ID 101172857, Funded under Climate, Energy and Mobility. Funding Scheme: HORIZON-CL5-2024-D3-01-07, HORIZON Research and Innovation Actions.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Killingtveit, Å. Hydropower. In Managing Global Warming; Letcher, T.M., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2019; pp. 265–315. ISBN 978-0-12-814104-5. [Google Scholar]

- Darmawi; Sipahutar, R.; Bernas, S.M.; Imanuddin, M.S. Renewable Energy and Hydropower Utilization Tendency Worldwide. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2013, 17, 213–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frey, G.W.; Linke, D.M. Hydropower as a Renewable and Sustainable Energy Resource Meeting Global Energy Challenges in a Reasonable Way. Energy Policy 2002, 30, 1261–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahi, O.P.; Chandel, A.K. Refurbishment and Uprating of Hydro Power Plants—A Literature Review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 48, 726–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, K.; Saini, R.P. A Review on Operation and Maintenance of Hydropower Plants. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2022, 49, 101704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanbhag, V.V.; Kandukuri, S.T.; Olimstad, G.; Schlanbusch, R. Predictive Maintenance of Critical Components in Hydroelectric Turbines: A Review. IEEE Sens. J. 2025, 25, 31959–31979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klemeš, J.J.; Foley, A.; You, F.; Aviso, K.; Su, R.; Bokhari, A. Sustainable Energy Integration within the Circular Economy. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2023, 177, 113143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klemeš, J.J.; Varbanov, P.S.; Walmsley, T.G.; Foley, A. Process Integration and Circular Economy for Renewable and Sustainable Energy Systems. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2019, 116, 109435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quaranta, E.; Hunt, J. Chapter 9—Retrofitting and Refurbishment of Hydropower Plants: Case Studies and Novel technologies. In Renewable Energy Production and Distribution; Jeguirim, M., Ed.; Advances in Renewable Energy Technologies; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2022; Volume 1, pp. 301–322. ISBN 978-0-323-91892-3. [Google Scholar]

- de Santis, R.B.; Gontijo, T.S.; Costa, M.A. Condition-Based Maintenance in Hydroelectric Plants: A Systematic Literature Review. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part O J. Risk Reliab. 2022, 236, 631–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betti, A.; Crisostomi, E.; Paolinelli, G.; Piazzi, A.; Ruffini, F.; Tucci, M. Condition Monitoring and Predictive Maintenance Methodologies for Hydropower Plants Equipment. Renew. Energy 2021, 171, 246–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W. Research on Predictive Maintenance for Hydropower Plant Based on MAS and NN. In Proceedings of the 2008 Third International Conference on Pervasive Computing and Applications, Alexandria, Egypt, 6–8 October 2008; Volume 2, pp. 604–609. [Google Scholar]

- Sathish, K.; Nithyanandhan, T.; Ravishankar, P.; Rohith, S.; Malathi, L.K. Material Characteristics and Its Performance Measures in Turbine: A Review. AIP Conf. Proc. 2024, 3221, 020020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Overman, N.; Smith, C.; Ross, K. Microstructure, Hardness and Cavitation Erosion Resistance of Different Cold Spray Coatings on Stainless Steel 316 for Hydropower Applications. Mater. Today Commun. 2020, 25, 101305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Tiwari, S.K.; Mishra, S.K. Cavitation Erosion in Hydraulic Turbine Components and Mitigation by Coatings: Current Status and Future Needs. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2012, 21, 1539–1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, A.K.; Goel, D.B.; Prakash, S. Erosion Behaviour of Hydro Turbine Steels. Bull. Mater. Sci. 2008, 31, 115–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reza Kashyzadeh, K.; Ridha, W.K.M.; Ghorbani, S. The Influence of Nanocoatings on the Wear, Corrosion, and Erosion Properties of AISI 304 and AISI 316L Stainless Steels: A Critical Review Regarding Hydro Turbines. Corros. Mater. Degrad. 2025, 6, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quaranta, E.; Davies, P. Emerging and Innovative Materials for Hydropower Engineering Applications: Turbines, Bearings, Sealing, Dams and Waterways, and Ocean Power. Engineering 2022, 8, 148–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darweesh, S.Y.; Rasheed, R.A.; Abdullah, M.A. Treatment of Failures in Turbine Blades by Cermet Coatings. J. Fail. Anal. Prev. 2023, 23, 2461–2470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Li, H.; Lei, Q.; Fu, Q.; Ma, C.; Yao, D.; Wang, Y.; Sun, C.; Wei, J.; Han, Z. Effect of Spraying Power on Microstructure and Bonding Strength of MoSi2-Based Coatings Prepared by Supersonic Plasma Spraying. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2011, 257, 5566–5570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munteanu, C.; Paleu, V.; Istrate, B.; Dascălu, A.; Cîrlan Paleu, C.; Bhaumik, S.; Ancaş, A.D. Tribological Behavior and Microstructural Analysis of Atmospheric Plasma Spray Deposited Thin Coatings on Cardan Cross Spindles. Materials 2021, 14, 7322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurup, P.; Remo, T.W.; Jenne, S.D.; O’Connor, P.; Cotrell, J. Analysis of Supply Chains and Advanced Manufacturing of Small Hydropower Systems; National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL): Golden, CO, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Rahi, O.P.; Kumar, A. Economic Analysis for Refurbishment and Uprating of Hydro Power Plants. Renew. Energy 2016, 86, 1197–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogayar, B.; Vidal, P.G.; Hernandez, J.C. Analysis of the Cost for the Refurbishment of Small Hydropower Plants. Renew. Energy 2009, 34, 2501–2509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elia, V.; Gnoni, M.G.; Tornese, F. Measuring Circular Economy Strategies through Index Methods: A Critical Analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 142, 2741–2751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avdiushchenko, A.; Zając, P. Circular Economy Indicators as a Supporting Tool for European Regional Development Policies. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherwood, J.; Gongora, G.T.; Velenturf, A.P.M. A Circular Economy Metric to Determine Sustainable Resource Use Illustrated with Neodymium for Wind Turbines. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 376, 134305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gennitsaris, S.; Sagani, A.; Sofianopoulou, S.; Dedoussis, V. Integrated LCA and DEA Approach for Circular Economy-Driven Performance Evaluation of Wind Turbine End-of-Life Treatment Options. Appl. Energy 2023, 339, 120951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontana, A.; Barni, A.; Leone, D.; Spirito, M.; Tringale, A.; Ferraris, M.; Reis, J.; Goncalves, G. Circular Economy Strategies for Equipment Lifetime Extension: A Systematic Review. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellet-Viciano, L.; Hernández-Chover, V.; Hernández-Sancho, F. The Benefits of Circular Economy Strategies in Urban Water Facilities. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 844, 157172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosa, P.; Sassanelli, C.; Urbinati, A.; Chiaroni, D.; Terzi, S. Assessing Relations between Circular Economy and Industry 4.0: A Systematic Literature Review. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2020, 58, 1662–1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, A.; Skene, K.; Haynes, K. The Circular Economy: An Interdisciplinary Exploration of the Concept and Application in a Global Context. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 140, 369–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Pascale, A.; Arbolino, R.; Szopik-Depczyńska, K.; Limosani, M.; Ioppolo, G. A Systematic Review for Measuring Circular Economy: The 61 Indicators. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 281, 124942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saidani, M.; Yannou, B.; Leroy, Y.; Cluzel, F.; Kendall, A. A Taxonomy of Circular Economy Indicators. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 207, 542–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moraga, G.; Huysveld, S.; Mathieux, F.; Blengini, G.A.; Alaerts, L.; Van Acker, K.; de Meester, S.; Dewulf, J. Circular Economy Indicators: What Do They Measure? Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 146, 452–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meadows, D.; Meadows, D.; Randers, J.; Behrens, W., III. The Limits of Growth; Universe Books NEW YORK: New York, NY, USA, 1972; ISBN 0-87663-165-0. [Google Scholar]

- Winans, K.; Kendall, A.; Deng, H. The History and Current Applications of the Circular Economy Concept. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 68, 825–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stahel, W.R. History of the Circular Economy. The Historic Development of Circularity and the Circular Economy. In The Circular Economy in the European Union: An Interim Review; Eisenriegler, S., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 7–19. ISBN 978-3-030-50239-3. [Google Scholar]

- Korhonen, J.; Honkasalo, A.; Seppälä, J. Circular Economy: The Concept and Its Limitations. Ecol. Econ. 2018, 143, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greyson, J. An Economic Instrument for Zero Waste, Economic Growth and Sustainability. J. Clean. Prod. 2007, 15, 1382–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Z.; Bi, J.; Moriguichi, Y. The Circular Economy: A New Development Strategy in China. J. Ind. Ecol. 2006, 10, 4–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, D.W.; Turner, R.K. Economics of Natural Resources and the Environment; JHU Press: Baltimore, ML, USA, 1989; ISBN 978-0-8018-3986-3. [Google Scholar]

- Ogunmakinde, O.E.; Sher, W.; Egbelakin, T. Circular Economy Pillars: A Semi-Systematic Review. Clean Technol. Environ. Policy 2021, 23, 899–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation. The Business Opportunity of a Circular Economy. In An Introduction to Circular Economy; Liu, L., Ramakrishna, S., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2021; pp. 397–417. ISBN 978-981-15-8510-4. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, J. Circular Cities: What Are the Benefits of Circular Development? Sustainability 2021, 13, 5725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, K. A Circular Economy Is About the Economy. Circ. Econ. Sustain. 2021, 1, 115–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, A.; Mukhuty, S.; Kumar, V.; Kazancoglu, Y. Blockchain Technology and the Circular Economy: Implications for Sustainability and Social Responsibility. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 293, 126130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hina, M.; Chauhan, C.; Sharma, R.; Dhir, A. Circular Economy Business Models as Pillars of Sustainability: Where Are We Now, and Where Are We Heading? Bus. Strategy Environ. 2023, 32, 6182–6209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, C.T.; Oliveira, G.G.A. What Circular Economy Indicators Really Measure? An Overview of Circular Economy Principles and Sustainable Development Goals. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2023, 190, 106850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X.; Ogunseitan, O.A.; Nakamura, S.; Suh, S.; Kral, U.; Li, J.; Geng, Y. Reshaping Global Policies for Circular Economy. Circ. Econ. 2022, 1, 100003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munonye, W.C.; Ajonye, G.O. Energy-Driven Circular Design in the Built Environment: Rethinking Architecture and Infrastructure. Front. Sustain. Cities 2025, 7, 1569362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikulėnas, M.; Šeduikytė, L. Circularity and Decarbonization Synergies in the Construction Sector: Implications for Zero-Carbon Energy Policy. Energies 2025, 18, 1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, D. Evaluating and Prioritizing Strategies to Reduce Carbon Emissions in the Circular Economy for Environmental Sustainability. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 373, 123446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinina, O.; Kirsanova, N.; Nevskaya, M. Circular Economy Models in Industry: Developing a Conceptual Framework. Energies 2022, 15, 9376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walmsley, T.G.; Ong, B.H.Y.; Klemeš, J.J.; Tan, R.R.; Varbanov, P.S. Circular Integration of Processes, Industries, and Economies. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2019, 107, 507–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blomsma, F.; Brennan, G. The Emergence of Circular Economy: A New Framing Around Prolonging Resource Productivity. J. Ind. Ecol. 2017, 21, 603–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigamonti, L.; Mancini, E. Life Cycle Assessment and Circularity Indicators. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2021, 26, 1937–1942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Hashemizadeh, A. Circular Economy-Based Assessment Framework for Enhancing Sustainability in Renewable Energy Development with Life Cycle Considerations. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2023, 103, 107289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacurariu, R.L.; Vatca, S.D.; Lakatos, E.S.; Bacali, L.; Vlad, M. A Critical Review of EU Key Indicators for the Transition to the Circular Economy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2021, 18, 8840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinho, V.J.P.D. Insights into Circular Economy Indicators: Emphasizing Dimensions of Sustainability. Environ. Sustain. Indic. 2021, 10, 100119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allesch, A.; Brunner, P.H. Material Flow Analysis as a Decision Support Tool for Waste Management: A Literature Review. J. Ind. Ecol. 2015, 19, 753–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laner, D.; Rechberger, H.; Astrup, T. Systematic Evaluation of Uncertainty in Material Flow Analysis. J. Ind. Ecol. 2014, 18, 859–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rincón-Moreno, J.; Ormazábal, M.; Álvarez, M.J.; Jaca, C. Advancing Circular Economy Performance Indicators and Their Application in Spanish Companies. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 279, 123605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, M.; Miguel, M.; van Langen, S.K.; Ncube, A.; Zucaro, A.; Fiorentino, G.; Passaro, R.; Santagata, R.; Coleman, N.; Lowe, B.H.; et al. Circular Economy and the Transition to a Sustainable Society: Integrated Assessment Methods for a New Paradigm. Circ. Econ. Sustain. 2021, 1, 99–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Antón, J.M.; Rubio-Andrada, L.; Celemín-Pedroche, M.S.; Ruíz-Peñalver, S.M. From the Circular Economy to the Sustainable Development Goals in the European Union: An Empirical Comparison. Int. Environ. Agreem. Polit. Law Econ. 2022, 22, 67–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patino-Alonso, C.; Espejo, F.; Zazo, S.; Molina, J.-L. Introducing the Circularity Index for Dams/Reservoirs (CIDR). Water 2023, 15, 2268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jishkariani, M.; Ghosh, S.K.; Didbaridze, K. Energy and Economic Indicators Influencing Circular Economy in Georgia. In Circular Economy: Recent Trends in Global Perspective; Ghosh, S.K., Ghosh, S.K., Eds.; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2021; pp. 331–358. ISBN 978-981-16-0913-8. [Google Scholar]

- González, A.; Sendra, C.; Herena, A.; Rosquillas, M.; Vaz, D. Methodology to Assess the Circularity in Building Construction and Refurbishment Activities. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. Adv. 2021, 12, 200051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niero, M.; Kalbar, P.P. Coupling Material Circularity Indicators and Life Cycle Based Indicators: A Proposal to Advance the Assessment of Circular Economy Strategies at the Product Level. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 140, 305–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, C.; Gonçalves, G. A Systematic Review on Life Extension Strategies in Industry: The Case of Remanufacturing and Refurbishment. Electronics 2021, 10, 2669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, P.; Cervantes, G.C.; Zaragoza-Benzal, A.; Byrne, A.; Karaca, F.; Ferrández, D.; Salles, A.; Bragança, L. Circular Material Usage Strategies and Principles in Buildings: A Review. Buildings 2024, 14, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cusenza, M.A.; Novi, A.; Daddi, T.; Girardi, P.; Iraldo, F. A Multidimensional and Multi-Criteria Framework for Measuring the Circularity of Energy Generation Systems at National Level. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 448, 141578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, S.; Coleman, N.; Hodgson, P.; Collins, N.; Brimacombe, L. Evaluating the Environmental Dimension of Material Efficiency Strategies Relating to the Circular Economy. Sustainability 2018, 10, 666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luangphon, S.; Shen, J.; Huang, X.; Ramirez, J.; Han, Y.; Ruan, X. Evaluation of the Environmental Effects from Hydropower Plants Using Life Cycle Assessment: A Review. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2025, 223, 108530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, M.; Zhang, L.; Wang, C.; Liu, G. Environmental Life Cycle Assessment of a Small Hydropower Plant in China. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2015, 20, 796–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McManamay, R.A.; Parish, E.S.; DeRolph, C.R.; Witt, A.M.; Graf, W.L.; Burtner, A. Evidence-Based Indicator Approach to Guide Preliminary Environmental Impact Assessments of Hydropower Development. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 265, 110489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nika, C.E.; Vasilaki, V.; Expósito, A.; Katsou, E. Water Cycle and Circular Economy: Developing a Circularity Assessment Framework for Complex Water Systems. Water Res. 2020, 187, 116423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maio, F.D.; Rem, P.C. A Robust Indicator for Promoting Circular Economy through Recycling. J. Environ. Prot. 2015, 6, 1095–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preisner, M.; Smol, M.; Horttanainen, M.; Deviatkin, I.; Havukainen, J.; Klavins, M.; Ozola-Davidane, R.; Kruopienė, J.; Szatkowska, B.; Appels, L.; et al. Indicators for Resource Recovery Monitoring within the Circular Economy Model Implementation in the Wastewater Sector. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 304, 114261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gureva, M.A. Conservation and Rational Use of Natural Resources: Methods of Circular Economy Assessment. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 828, 012010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Summers, S.; Jones, J.W.; Reid, J.F. A Scalable Index for Quantifying Circularity of Bioeconomy Systems. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2024, 210, 107821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iofrida, N.; Spada, E.; Gulisano, G.; De Luca, A.I.; Falcone, G. The Social Impacts of Circular Economy: Disclosing Epistemological Stances and Methodological Practices. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drofenik, J.; Seljak, T.; Novak Pintarič, Z. A Multi-Level Approach to Circular Economy Progress: Linking National Targets with Corporate Implementation. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 493, 144902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Werf, L.; Colletis, G.; Negny, S.; Montastruc, e.L. Toward a Generic Method to Help Develop Circular Economy Indicators. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 494, 144678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdirahman, A.A.; Asif, M.; Mohsen, O. Circular Economy in the Renewable Energy Sector: A Review of Growth Trends, Gaps and Future Directions. Energy Nexus 2025, 17, 100395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J. Embracing Circular Economy Concepts in Hydropower Generation: A Review of Sustainable Practices and Future Prospect. Appl. Comput. Eng. 2024, 85, 242–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandpal, V.; Jaswal, A.; Santibanez Gonzalez, E.D.R.; Agarwal, N. Challenges and Opportunities for Sustainable Energy Transition and Circular Economy. In Sustainable Energy Transition: Circular Economy and Sustainable Financing for Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) Practices; Kandpal, V., Jaswal, A., Santibanez Gonzalez, E.D.R., Agarwal, N., Eds.; Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 307–324. ISBN 978-3-031-52943-6. [Google Scholar]

- Baral, B.; Kharel, B.; Dawadi, A.; Timsina, S.; Bhattarai, S.; Joshi, R. Sustainable Manufacturing Practices in the Hydropower Industry: A Review. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2024, 1385, 012017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandpal, V.; Jaswal, A.; Santibanez Gonzalez, E.D.R.; Agarwal, N. Policy Framework for Sustainable Energy Transition and the Circular Economy. In Sustainable Energy Transition: Circular Economy and Sustainable Financing for Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) Practices; Kandpal, V., Jaswal, A., Santibanez Gonzalez, E.D.R., Agarwal, N., Eds.; Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 217–238. ISBN 978-3-031-52943-6. [Google Scholar]

- Tleuken, A.; Tokazhanov, G.; Jemal, K.M.; Shaimakhanov, R.; Sovetbek, M.; Karaca, F. Legislative, Institutional, Industrial and Governmental Involvement in Circular Economy in Central Asia: A Systematic Review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegab, H.; Shaban, I.; Jamil, M.; Khanna, N. Toward Sustainable Future: Strategies, Indicators, and Challenges for Implementing Sustainable Production Systems. Sustain. Mater. Technol. 2023, 36, e00617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogan, T.W.; Cada, G.F.; Amaral, S.V. The Status of Environmentally Enhanced Hydropower Turbines. Fisheries 2014, 39, 164–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moraga, G.; Huysveld, S.; De Meester, S.; Dewulf, J. Development of Circularity Indicators Based on the In-Use Occupation of Materials. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 279, 123889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogiantzi, C.; Tserpes, K. On the Definition, Assessment, and Enhancement of Circular Economy across Various Industrial Sectors: A Literature Review and Recent Findings. Sustainability 2023, 15, 16532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quaranta, E.; Pérez-Díaz, J.I.; Romero–Gomez, P.; Pistocchi, A. Environmentally Enhanced Turbines for Hydropower Plants: Current Technology and Future Perspective. Front. Energy Res. 2021, 9, 703106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, G.; Wang, S.; Teng, Q.; Zuo, J.; Tan, X.; Wang, H.; Liu, Z. The Sustainable Future of Hydropower: A Critical Analysis of Cooling Units via the Theory of Inventive Problem Solving and Life Cycle Assessment Methods. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 142, 2446–2453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagnon, L.; Klimpt, J.-É.; Seelos, K. Comparing Recommendations from the World Commission on Dams and the IEA Initiative on Hydropower. Energy Policy 2002, 30, 1299–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoka, M.; Korez Vide, R. Circular Economy Implementation in the Electric and Electronic Equipment Industry: Challenges and Opportunities. Sustainability 2025, 17, 7700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdmouleh, Z.; Alammari, R.A.M.; Gastli, A. Review of Policies Encouraging Renewable Energy Integration & Best Practices. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 45, 249–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermann, R.R.; Pansera, M.; Nogueira, L.A.; Monteiro, M. Socio-Technical Imaginaries of a Circular Economy in Governmental Discourse and among Science, Technology, and Innovation Actors: A Norwegian Case Study. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2022, 183, 121903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gembali, V.; Kumar, A.; Sarma, P.R.S. Analysis and Influence Mapping of Socio-Technical Challenges for Developing Decarbonization and Circular Economy Practices in the Construction and Building Industry. Ann. Oper. Res. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandpal, V.; Jaswal, A.; Santibanez Gonzalez, E.D.R.; Agarwal, N. Sustainable Energy Transition, Circular Economy, and ESG Practices. In Sustainable Energy Transition: Circular Economy and Sustainable Financing for Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) Practices; Kandpal, V., Jaswal, A., Santibanez Gonzalez, E.D.R., Agarwal, N., Eds.; Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 1–51. ISBN 978-3-031-52943-6. [Google Scholar]

- Kuzma, E.L.; Sehnem, S.; Lopes de Sousa Jabbour, A.B.; Campos, L.M.S. Circular Economy Indicators and Levels of Innovation: An Innovative Systematic Literature Review. Int. J. Product. Perform. Manag. 2021, 71, 952–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- What We Do—RevHydro. Available online: https://revhydro.eu/ (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- Jerome, A.; Helander, H.; Ljunggren, M.; Janssen, M. Mapping and Testing Circular Economy Product-Level Indicators: A Critical Review. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2022, 178, 106080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghisellini, P.; Cialani, C.; Ulgiati, S. A Review on Circular Economy: The Expected Transition to a Balanced Interplay of Environmental and Economic Systems. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 114, 11–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pepe, C.; Zanoli, S.M. Digitalization, Industry 4.0, Data, KPIs, Modelization and Forecast for Energy Production in Hydroelectric Power Plants: A Review. Energies 2024, 17, 941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Chover, V.; Castellet-Viciano, L.; Bellver-Domingo, Á.; Hernández-Sancho, F. The Potential of Digitalization to Promote a Circular Economy in the Water Sector. Water 2022, 14, 3722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vagnoni, E.; Gezer, D.; Anagnostopoulos, I.; Cavazzini, G.; Doujak, E.; Hočevar, M.; Rudolf, P. The New Role of Sustainable Hydropower in Flexible Energy Systems and Its Technical Evolution through Innovation and Digitalization. Renew. Energy 2024, 230, 120832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Tang, X.; Gaidai, O.; Wang, F. Digital Twin Real Time Monitoring Method of Turbine Blade Performance Based on Numerical Simulation. Ocean Eng. 2022, 263, 112347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, R.; Chen, M.; Liu, W.; Jian, H.; Shi, Y. Digital Twin Technologies for Turbomachinery in a Life Cycle Perspective: A Review. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabir, M.R.; Halder, D.; Ray, S. Digital Twins for IoT-Driven Energy Systems: A Survey. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 177123–177143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geist, H.; Balle, F. A Circularity Engineering Focused Empirical Status Quo Analysis of Automotive Remanufacturing Processes. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2024, 201, 107328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saari, L.; Valkokari, K.; Martins, J.T.; Acerbi, F. Circular Economy Matrix Guiding Manufacturing Industry Companies towards Circularity—A Multiple Case Study Perspective. Circ. Econ. Sustain. 2024, 4, 2505–2530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaustad, G.; Krystofik, M.; Bustamante, M.; Badami, K. Circular Economy Strategies for Mitigating Critical Material Supply Issues. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 135, 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, N. Circular Economy Perspectives: Challenges, Innovations, and Sustainable Futures. Discov. Sustain. 2025, 6, 738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terra dos Santos, L.C.; Giannetti, B.F.; Agostinho, F.; Liu, G.; Almeida, C.M.V.B. A Multi-Criteria Approach to Assess Interconnections among the Environmental, Economic, and Social Dimensions of Circular Economy. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 342, 118317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deeney, P.; Leahy, P.G.; Campbell, K.; Ducourtieux, C.; Mullally, G.; Dunphy, N.P. End-of-Life Wind Turbine Blades and Paths to a Circular Economy. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2025, 212, 115418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cieślewicz, N.; Pilarski, K.; Pilarska, A.A. End-of-Life Strategies for Wind Turbines: Blade Recycling, Second-Life Applications, and Circular Economy Integration. Energies 2025, 18, 5182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishnaevsky, L. Sustainable End-of-Life Management of Wind Turbine Blades: Overview of Current and Coming Solutions. Materials 2021, 14, 1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Díaz, J.I.; Chazarra, M.; García-González, J.; Cavazzini, G.; Stoppato, A. Trends and Challenges in the Operation of Pumped-Storage Hydropower Plants. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 44, 767–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.-F.; Oh, U.-J.; Park, J.-C.; Park, E.S.; Im, H.-B.; Lee, K.Y.; Choi, J.-S. A Review of World-Wide Advanced Pumped Storage Hydropower Technologies. IFAC-Pap. 2022, 55, 170–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasir, J.; Javed, A.; Ali, M.; Ullah, K.; Kazmi, S.A.A. Capacity Optimization of Pumped Storage Hydropower and Its Impact on an Integrated Conventional Hydropower Plant Operation. Appl. Energy 2022, 323, 119561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).