Abstract

This paper presents an evaluation of the use of deep learning architectures for forecasting electrical energy consumption in residential environments. The main contribution of this study lies in the development and assessment of a hybrid forecasting framework that integrates multiscale temporal analysis and weather data, enabling evaluation of predictive performance across different temporal granularities, forecast horizons, and aggregation levels. Single and hybrid models were compared, trained with high-resolution data from a single residence, both considering only endogenous variables and including exogenous variables (weather data). The results showed that, among all models tested in this study, the hybrid LSTM + GRU model achieved the highest predictive performance, with R2 values of 94.62% using energy data and 95.25% when weather variables were included. Intermediary granularities, particularly the 6 steps, offered the best balance between temporal detail and predictive robustness for the tests performed. Furthermore, short-time windows aggregation (1 to 5 min) showed better accuracy, while the inclusion of weather data in scenarios with larger aggregation windows and longer horizons provided additional gains. The results reinforce the potential of hybrid deep learning models as effective tools for forecasting residential electricity consumption, with possible practical applications in energy management, automation, and integration of distributed energy resources.

1. Introduction

The growing demand for electricity, driven by urbanization, changing consumption patterns, and the intensive use of electrical equipment and thermal comfort systems, has placed the electricity sector under intense pressure to operate more efficiently, sustainably, and resiliently. In this scenario, residential consumption represents a significant portion of the total load of electrical systems and is strongly influenced by behavioral, economic, and climatic factors [1]. The increased expansion of photovoltaic (PV) systems, electric vehicle (EV) charging, domestic storage, and participation in demand response (DR) programs contributes to making the residential consumption profile increasingly dynamic and nonlinear [2].

Given this complexity, accurately forecasting residential electrical energy consumption, also known as electricity consumption, becomes a fundamental component for operational planning, efficient management of distributed energy resources (DERs), decision-making support in intelligent systems, and policy formulation [3]. However, forecasting electrical energy consumption in residential environments presents additional challenges, as consumption patterns exhibit strong temporal variability, are highly sensitive to external factors (such as temperature and weather conditions), and reflect the specific habits of each user or residence. Nevertheless, the main problems hampering the accuracy of residential electricity consumption forecasting are the lack of a solid database.

To improve the quality of residential electricity consumption forecasting, different data processing strategies have been employed in the literature. In [4], a short-term residential load forecasting model was developed that evaluated the spatial and temporal characteristics of the data, the irregularity of consumption patterns, and the recurrent occurrence of demand peaks to improve the overall quality of future load consumption forecasts. Similarly, Refs [5,6,7] developed models for forecasting building load, residential load, and residential and regional load, respectively, all in the short-term horizon. These studies adopted a two-stage approach, in which the data initially underwent a preprocessing step, followed by the application of a hybrid architecture to identify spatial and temporal dependencies. Already in [8], the segmentation of long sequences into multiple subsequences was proposed, aligning them on the temporal axis, to structure them as input vectors for the short-term residential load forecasting model. Furthermore, baselines were extracted from these subsequences, aiming to improve data representation in the modeling process.

Missing data and measurement inconsistencies are aggravating factors in data quality. One alternative to address this problem is their removal, as performed by [9]. In the study presented in [10], data processing and analysis were performed, including the elimination of outliers and the imputation of missing values, to improve the forecasting of renewable energy consumption and generation for individual customers, each embedded in a real-time demand side management (DSM) controller.

It is worth noting that prior data analysis is necessary and can have a significant impact on the forecasting result. However, by using a complete database, this step can be omitted, which is beneficial in situations where processing capacity is limited and a rigorous data collection and storage process is required for real-time operations, such as in embedded Artificial Intelligence (AI) systems with Internet of Things (IoT) devices. In this context, ref. [11] developed a forecasting system for residential consumers using smart home IoT devices with minimal preprocessing, while [12] implemented a DSM framework on a Raspberry Pi platform for load forecasting and data acquisition in greenhouses, also without prior data treatment.

Database selection and quality are important for forecasting model performance, given the high variability of residential electricity consumption [13], which is influenced by multiple factors. Different studies have enhanced predictive modeling by combining consumption history with complementary information such as climate variables and occupancy patterns. Thus, ref. [14] incorporated climate parameters, occupancy profiles, and historical demand, while [13,15] used both total household and individual appliance consumption data to predict residential electricity demand, based on datasets by [16].

Following this approach, ref. [17] used only historical household consumption data, incorporating time of day, weekday, and holiday indicators for single-stage forecasting. Similarly, ref. [18] applied historical energy, calendar, and weather data for DSM forecasting. In [19], for residential load forecasting, consumers were selected from a big dataset, based on the hot water usage criterion, using the historical electricity consumption of these households.

The diversity of data used in previous studies underscores the complexity of residential consumption forecasting, demanding models capable of integrating multiple databases, with consumption history as the main reference for predictive modeling. Several forecasting techniques have been explored, including statistical, machine learning (ML), and deep learning (DL) approaches [20]. DL, a subset of ML, employs multi-layer neural networks to automatically learn complex, nonlinear, and hierarchical patterns in large datasets [21,22,23]. Moreover, DL-based approaches in hybrid models have proven to be especially effective at learning nonlinear and complex patterns, as well as efficiently extracting spatiotemporal features from data [7]. Recent advances in these models have led to notable improvements in time series modeling, surpassing the limitations of traditional statistical models.

In this context, various techniques for forecasting residential load and energy consumption are found in the literature. To predict the load of a residence, ref. [3] developed a hybrid model that combines Convolutional Neural Network (CNN), Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory (BiLSTM), and Self-Attention (SA) mechanisms (CNN-BiLSTM-SA), while [24] applied CNN-BiLSTM model was used to forecast electrical energy consumption in individual residences. Similar applications, such as CNN and Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) models (CNN-LSTM), were employed by [9,17,25] for residential contexts, and by [7,26,27] for both residential and commercial buildings. In turn, the hybrid CNN and Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU) model (CNN-GRU) used by [6] outperformed other simple and hybrid architectures in residential load forecasting, a result corroborated by [20], where CNN-GRU achieved the best performance in smart home consumption prediction using different data granularities based on weather and energy data.

Expanding on these hybrid approaches, ref. [28] proposed a convolutional long-short-term memory (ConvLSTM) with BiLSTM architecture for forecasting residential and commercial electrical energy consumption, while [22] employed an LSTM-based architecture with a self-attention mechanism (LSTM-Attention), incorporating explicit temporal coding to predict active and reactive energy consumption in residential environments. Recent advances have also incorporated the self-attention mechanism inspired by the Transformer model, as in [29,30], where CNN and Fourier Transform-combined Transformer frameworks were applied to short-term load forecasting and large-scale energy forecasting and management, respectively, demonstrating the ability to capture local and global temporal dependencies in complex consumption patterns.

However, DL techniques have also been applied to residential electrical energy consumption forecasting problems using simple architectures, yielding satisfactory results. In [21,31], LSTM-based models achieved high accuracy in forecasting residential load and energy consumption, particularly when weather and appliance data were included as inputs, emphasizing the importance of exogenous information. Similarly, in [32], short-term load forecasting was performed using real consumption data from a distribution company and compared Recurrent Neural Network (RNN), LSTM, and GRU models, with GRU showing higher predictive accuracy and lower errors. Transformer-based approaches have also been extended to broader contexts, as shown in [14,33], where hierarchical and sparse attention mechanisms effectively modeled both cross-dependencies between different buildings and long-term temporal relationships, enhancing interpretability and scalability in residential electrical energy forecasting.

In analyzing the studies evaluated, the LSTM and GRU models have wide application due to their ability to capture long-term temporal dependencies. Similarly, the CNN model has been successfully explored with temporal data, while newer architectures such as the Transformer offer computational advantages and flexibility in managing complex sequences. In particular, combinations of these models, especially the CNN-LSTM model, have demonstrated the best results for forecasting residential energy load and consumption.

Despite these advances, studies assessing the performance of different architectures in residential electrical energy consumption are still limited, especially considering scenarios with and without integrated weather data, different forecast horizons, and varying temporal resolutions. Therefore, a significant gap in the literature is identified regarding the robust analysis of the applicability and generalizability limits of a forecasting framework for a single residence with high data variability and nonlinearity.

In this context, this paper presents a hybrid forecasting framework that integrates multiscale temporal analysis with weather data, aiming to compare the performance of different DL models in forecasting residential electrical energy consumption and to assess predictive performance across multiple temporal granularities, forecast horizons, and aggregation levels. The analysis was performed using a high-resolution (1 min) dataset, considering different combinations of forecast horizons, input windows, and whether or not to include weather variables as exogenous data. The results obtained not only highlight the limits and advantages of each approach in terms of accuracy and computational effort but also demonstrate that the developed framework provides a scalable solution for forecasting residential electrical energy consumption, contributing to the advancement of intelligent demand management and smart grid applications.

2. Methods

The work developed for forecasting electrical energy consumption focused on a single residence, thus providing different predictions and accuracy analyses for different forecast horizons. The models were developed in Python (version 3.12.7) and implemented in the Spyder 5 IDE of the ANACONDA package (Anaconda, Inc., Austin, TX, USA). The models were processed on a PC with an Intel Core Ultra 7 155H processor (Intel Corporation, Santa Clara, CA, USA) (3.8 GHz), 32 GB of RAM (5600 MHz), a GeForce RTX 4060 GPU (NVIDIA Corporation, Santa Clara, CA, USA; driver version 32.0.15.7683), and Microsoft Windows 10 Pro (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA). The libraries used to develop the forecast models were: Pandas (version 2.1.4), NumPy (version 1.26.4), TensorFlow (version 2.19.0), Matplotlib (version 3.7.5), and Scikit-learn (version 1.4.2).

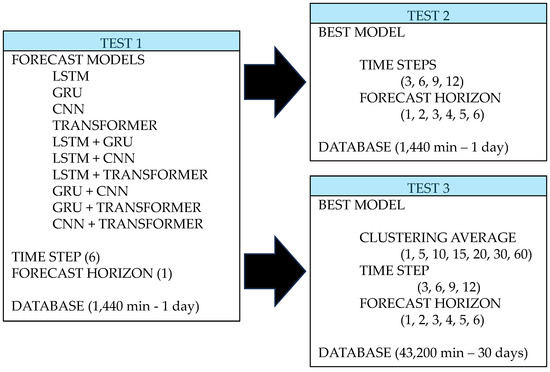

The methodology developed was structured into three tests, each consisting of training and validation stages. Figure 1 presents the macro-scheme of the tests performed.

Figure 1.

Macro-scheme of the methodology developed for electrical energy consumption forecasting tests for individual residences.

Test 1 aimed to identify the best-performing model for a full-day time series, with a 6 min time step and a 1 min forecast horizon. Based on the selected model, Tests 2 and 3 were conducted. Test 2 sought to evaluate the model’s performance when trained with different temporal granularities, using a dataset lasting 1440 min (equivalent to one day), the same database as in Test 1. In this regard, datasets with 3, 6, 9, and 12 time steps were considered, with multiple forecast horizons ranging from 1 to 6 min ahead. This stage aimed to verify the model’s sensitivity to the temporal resolution of the input data and to explore the generalization capability of the proposed framework under different update frequencies. Additionally, in [34], minute-by-minute energy consumption forecasting enhances efficiency by reducing waste and costs, while [35] highlights that very short-term (1 min) residential load forecasting captures the most recent load dynamics, with delayed entries (10 min).

Finally, Test 3 focused on assessing the robustness of the proposed framework to temporal data variability, simulating scenarios in which measurement granularity may be compromised by collection, transmission, or storage limitations. To achieve this, clustering was performed by calculating the data mean, resulting in the variable , considering different time windows () of 5, 10, 15, 20, 30, and 60 min, from the original database with a 1 min time step. For the 1 min clustering, it was not necessary to calculate the average, as the data with original resolution is already in compliance. This step allowed us to verify the model’s behavior when faced with loss of temporal resolution and its forecasting performance in contexts with less frequent data. The tests were conducted with aggregated data, using the same time step criteria and multiple forecast horizons adopted in Test 2, but at different time scales based on the different time windows. The database used in this stage corresponded to a period of 30 consecutive days, totaling 43,200 min of records.

Therefore, the proposed methodology is based on assessing the predictive capacity of models under different scenarios of temporal granularity and data variability. The three stages tested allow us to evaluate not only performance under ideal conditions but also the resilience of models under practical constraints on data collection and sampling frequency. The following section presents a detailed characterization of the database used, which is essential for the development, training, and validation of the proposed forecasting approaches.

2.1. Database

For the proposed study, the “H3_Wh” database available in [36] and mentioned in [37], was selected. It provides minute-by-minute data from a single residence in Ireland with a PV generation system, battery storage, and connection to the electrical grid. It should be noted that this database was selected because it presents good data consistency. The original “H3_Wh” database includes the following data:

- “Date”—Timestamps in 1 min intervals (Year 2020);

- “Discharge(Wh)”—Battery discharge;

- “Charge(Wh)”—Battery charge;

- “Production(Wh)”—PV energy production;

- “Feed-in(Wh)”—Energy injected into the electrical grid;

- “From grid(Wh)”—Energy supplied by the electrical grid;

- “State of Charge(%)”—Battery charge status;

- “Consumption(Wh)”—Energy consumption.

Additionally, to aggregate information and enable performance evaluation of the forecasting framework with the exogenous data, weather information was added, with minute-by-minute temporal resolution, also mentioned in the study by [37] and available in [36]. This database, called “Weather,” originally presents the following data:

- “Date”—Timestamps in 1 min intervals (Year 2020);

- “Speed”—Wind speed (knots);

- “Dir”—Wind direction (degrees);

- “Drybulb”—Drybulb temperature (degrees Celsius);

- “Cbl”—Atmospheric pressure (hPa);

- “Soltot”—Solar radiation (J/cm2);

- “Rain”—Rainfall (mm).

However, for the proposed study, only the variables “Discharge(Wh)”, “Charge(Wh)”, “Production(Wh)”, “Feed-in(Wh)”, “From grid(Wh)”, and “Consumption(Wh)” were selected from the “H3_Wh” database, and the variables “Speed”, “Drybulb”, and “Soltot” were selected from the “Weather” database. The database, considering the endogenous consumption and energy data of the residence, and the exogenous data represented by the weather data, was split into 80% for training and 20% for validation, for all tests performed. The data period used in this study comprises 30 days, limited to the interval from 00:00:00 on 13 March 2020 to 23:59:00 on 11 April 2020. Furthermore, to avoid magnitude problems, the database was normalized by Equation (1), similar to [20,21], and available in the Skit-Learn library [38,39].

where is the normalized variable, is the original variable, is the maximum value in the data, and is the minimum value in the data range.

It should be noted that no data imputation was performed, as there were no missing data in the database. However, zero values (“0”) were identified and retained as such, given that in real situations, this could occur due to some data collection error. Thus, the database used allows a comprehensive analysis of residential electrical energy demand, considering both consumption factors and external weather conditions. Careful data selection and processing guarantee the quality of information used to train and validate forecasting models. Below is a description of the models, highlighting the main adjustments made to optimize their performance in residential electrical energy consumption forecasting tests.

2.2. Deep Learning Models for Forecasting

The forecasting models implemented and tested in this study were selected based on their ability to handle the diversity and complexity of the dataset used. The forecasting architectures include LSTM, GRU, CNN, Transformer, and hybrid combinations of all these models. Additionally, the hybrid models are connected sequentially, with further details provided in Appendix A of the manuscript.

The models chosen for residential electrical energy consumption forecasting, based on historical household data and weather information, were selected to take advantage of the characteristics of each architecture. The LSTM is particularly effective at modeling long-term dependencies, which is essential for time series such as electricity consumption, where past patterns directly impact future predictions. Its ability to store important information over the long term is useful for capturing seasonal or behavioral fluctuations in consumption, especially when these patterns repeat over time [40,41,42]. Similarly, GRU maintains the ability to capture long-term temporal relationships, but with fewer parameters, making it faster to train without significantly compromising accuracy, offering benefits in terms of computational efficiency [32,34]. For weather data, such as temperature and solar radiation, where behavior can change quickly, GRU provides a good balance between accuracy and computational performance.

Alternatively, the CNN model has demonstrated great potential in recognizing temporal patterns in nonlinear datasets, such as electrical energy consumption [7,8,25]. This architecture is especially effective in scenarios with localized variations, such as demand peaks caused by weather changes, and can extract spatial and temporal features, which help improve forecast accuracy. Finally, the Transformer, with its attention mechanism, can handle large volumes of data and identify relationships in the long term without the limitations of sequential processing [29,33]. Its ability to focus on the most relevant ranges of input data makes it very effective at capturing complex, nonlinear interactions between electrical energy consumption and weather conditions, such as unexpected temperature changes that directly impact consumption behavior.

Additionally, hybridizing these models combines the strengths of each approach [6,41,43], resulting in a robust framework that can manage the complexity and uncertainty of residential consumption and weather data. Thus, the combination of pairwise architectures between all models, LSTM, GRU, CNN, and Transformer, allows the hybrid model to capture both long-term and short-term temporal dependencies, in addition to being able to deal with nonlinear data and complex interactions.

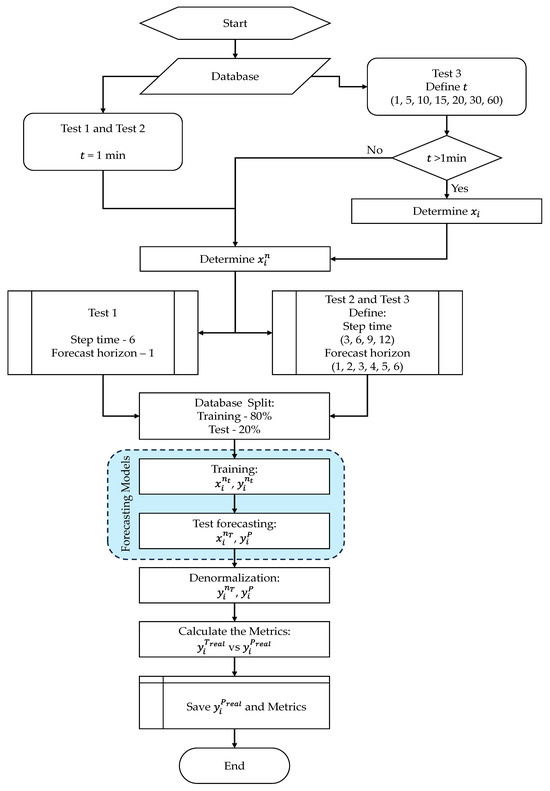

To enable replicability of the developed methodology, the parameters of each model used in this study are described in Appendix A in Table A1 attached to this document. Similarly, to illustrate the residential electrical energy consumption forecasting framework processes, Figure 2 demonstrates all the steps involved. It is noteworthy that the activation function used in all models was Gaussian Error Linear Units (GELUs), according to [44], and the K-fold technique was employed to split the database for training and testing. This method divides the database into random subsets to avoid bias in model evaluation. To preserve the temporal order of the data series, K-fold cross-validation was applied only after the input sequences were created, ensuring that the model always learned from past values to predict future ones. Thus, each fold maintained the real temporal series (e.g., the first six samples used for training and the 7th for the target sample), as mentioned in [45]. Other standardized parameters for all forecasting models related to the training stage are listed below in Table 1. Additional information regarding hyperparameter settings is provided in Appendix A of the manuscript. For other settings not mentioned, the model’s defaults were used.

Figure 2.

Operational flowchart of the residential electrical energy consumption forecasting framework.

Table 1.

Training parameters of the forecasting models.

This information details the variables in Figure 2:

- is the selected time window;

- are the real variables;

- are the normalized variables;

- is the normalized input variable for training;

- is the normalized target variable for training;

- is the normalized input variable for testing;

- is the normalized target variable for testing;

- is the forecast result;

- is the real target data for testing;

- is the forecast result (denormalized).

In addition to the methodology described, the performance of the forecasting models was evaluated using statistics widely used in the literature. The metrics included the mean absolute error (MAE), the mean squared error (MSE), the root mean squared error (RMSE), the mean absolute percentage error (MAPE), and the coefficient of determination (R2), respectively, in Equations (2)–(6).

where is the real target data for testing, is the forecast result denormalized, is the total samples, and is the mean of the samples of the . However, an adjustment to the MAPE calculation was necessary because there was data with a zero value for , which would result in an error due to division by zero being undefined. Therefore, it was considered that, if , then was used as the denominator in Equation (5), which represents the original MAPE function. However, if , then the value of was considered as the denominator. This prevents errors when processing divisions by zero and eliminates gross distortions caused by dividing by very low values of , which could also cause a significant increase in the MAPE value.

Furthermore, the processing times of each model were recorded to provide a more realistic representation of the computational effort required to run the tests. This approach enabled a detailed evaluation of the models’ performance, considering both their forecast accuracy and their computational efficiency. Thus, the extensive tests performed aimed to identify the model’s forecast limits under different scenarios, including variations in data temporal aggregation, changes in the forecast horizons, and modifications to the sampling intervals used as model input. Furthermore, all these combinations were evaluated in scenarios with and without the inclusion of weather data related to the electrical energy consumption of a single residence, allowing for a comprehensive evaluation of the impact of adding exogenous variables on forecast accuracy.

3. Results and Discussions

To present the results obtained in this study, this section was divided into three stages, which follow the same structure described in the methodology. Initially, the results of Test 1 are discussed, in which different forecasting model architectures were compared using high-resolution data and a 1 min forecast horizon to determine the best model for forward testing. Next, Test 2 evaluated the performance of the best-performing model across different combinations of time steps and forecast horizons, to identify its sensitivity to data granularity. Finally, using the best model from Test 1, Test 3 analyzes the effects of temporal aggregation over an extended period of 30 consecutive days.

All tests were conducted under two conditions. The first involved only endogenous variables, which included household electrical energy consumption and operating data. The second also incorporated exogenous variables, represented by weather data. This approach aimed to evaluate the effect of incorporating external variables on the accuracy of the forecast. The results were analyzed using widely used statistical metrics (MAE, MSE, RMSE, MAPE, and R2), along with the computational processing time for each model and test, to evaluate not only the forecast accuracy but also the efficiency and robustness of the models in the different scenarios tested. Additionally, the proposed framework was developed and validated using data from a single residence, which limits the generalizability of the findings to broader residential contexts.

3.1. Comparative Evaluation of Deep Learning Models for Residential Electrical Energy Consumption Forecasting—Test 1

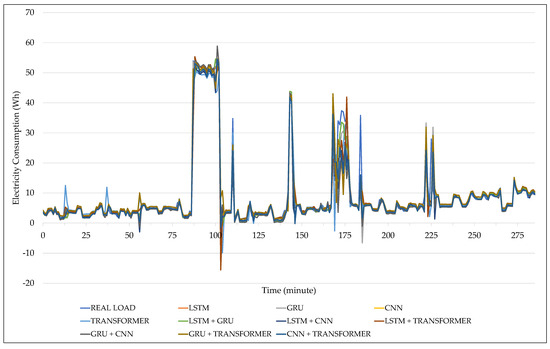

Test 1 was conducted to identify the DL model with the best performance in forecasting short-term residential electrical energy consumption, considering a single residence. To this end, the tests were initially performed using a database containing only endogenous variables, and subsequently, with the inclusion of exogenous variables. The database used in this test corresponds to a full day, with a 1 min temporal resolution. The models simulated included LSTM, GRU, CNN, Transformer, and hybrid pairwise combinations of these models. The graphical results for Test 1 are shown in Figure 3 for the endogenous data and in Figure 4 for the addition of exogenous data.

Figure 3.

Results of Test 1 with the endogenous database.

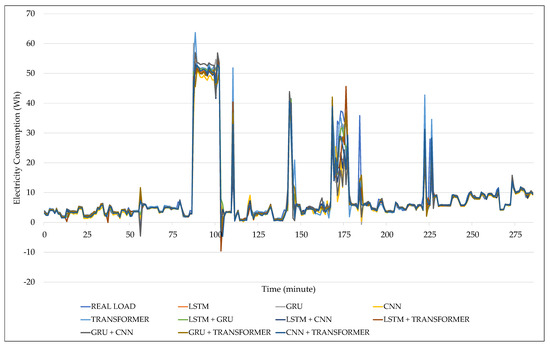

Figure 4.

Results of Test 1 with the endogenous and exogenous database.

As observed in Figure 3, the results obtained by each DL architecture in forecasting residential electrical energy consumption over time, considering exclusively endogenous variables, are presented. In general, it is observed that hybrid models outperform single architectures in most cases, exhibiting greater forecast capacity for the real load profile, especially during periods of high variability and consumption peaks. Among the models tested, the LSTM + GRU combination demonstrated the best forecast accuracy, with an estimated trajectory that closely matches the observed load profile, both during stable periods and abrupt transitions. This result contradicts the studies by [7,9,17,25], which found the hybrid CNN + LSTM model to perform best, as well as the studies by [6,20], which identified the CNN + GRU model as the best.

Additionally, Figure 4 expands this analysis by considering the impact of including exogenous variables on the performance of the evaluated DL models. It can be seen that the introduction of these attributes, such as air temperature, solar radiation, and wind speed, contributed to an overall improvement in forecasts, with noticeable reductions in deviations between real and estimated load, especially during short-term fluctuations and peak periods. The addition of weather variables proved particularly effective in the hybrid model LSTM + GRU, as well as in single architecture, GRU and LSTM models, which demonstrated a superior ability to anticipate abrupt variations.

The comparative analysis of the results in Figure 3 and Figure 4 shows that incorporating exogenous variables yielded consistent predictive gains in almost all architectures tested. This improvement was especially significant in models with recurrent structures, such as LSTM and GRU, which demonstrated greater sensitivity to temporal variations and, consequently, a better ability to adapt to the weather data. The results indicate that, even with a reduced time step (6 min) and forecast horizon (1 min), integrating exogenous variables provides an effective strategy for improving forecast accuracy in residential contexts.

To complement the graphical analysis, Table 2 presents the combined values of the error metrics and execution times for the tests with endogenous data. Among the single architectures, the GRU model presented the lowest values of MAE (0.8998), MSE (8.8624), and RMSE (2.9770), in addition to a competitive MAPE (9.96%), which is slightly higher than the value observed for LSTM (9.79%). It also obtained the best R2 (94.23%), even surpassing several hybrid models. However, the LSTM + GRU model stood out for achieving the lowest overall values among all the tested models for MAE (0.8994), MSE (8.2580), RMSE (2.8737), the lowest MAPE (10.86%) among the hybrids, and the highest overall R2 (94.62%), although with higher processing time. On the other hand, the CNN architecture, although it presented the shortest execution time (00:00:53:876), achieved lower predictive performance across all error metrics.

Table 2.

Results of models in Test 1 using only endogenous variables.

Table 3, which presents the results obtained by integrating exogenous variables, shows a generalized improvement in the evaluation metrics compared to tests with exclusively endogenous data. The LSTM + GRU model once again demonstrated high performance by achieving the best overall results, with the lowest values for MAE (0.8318), MSE (7.2917), RMSE (2.7003), and the highest R2 value (95.25%). Among the single models, GRU obtained the best results for MAE (0.8773), MSE (7.8017), RMSE (2.7931), and the highest R2 value (94.92%). The lowest overall value for MAE in Test 1 was achieved by the LSTM model (8.84%), followed by the hybrid LSTM + GRU architecture (9.61%) and the GRU model (10.36%). In terms of execution time, CNN continued to present the shortest processing time (00:00:52:214), but, as in the test with endogenous data, its predictive performance was worse.

Table 3.

Results of models in Test 1 with the integration of exogenous variables.

Therefore, given the results obtained in Test 1, the superiority of the hybrid LSTM + GRU model in forecasting short-term residential electrical energy consumption was confirmed, presenting the lowest error values for MAE, MSE, and RMSE, and the highest for R2 among all the architectures tested, both with endogenous variables and with the addition of exogenous data. Although associated with longer processing times, this model demonstrated greater adaptability to complex patterns and abrupt variations in the time series. This superior performance can be attributed to the complementary nature of the two architectures, since LSTM captures long-term dependencies through its gated memory structure, while GRU simplifies these mechanisms, allowing for faster convergence and less overfitting. When combined, the hybrid model benefits from LSTM’s ability to retain long-term temporal information and GRU’s efficiency in adapting to short-term fluctuations, resulting in more balanced and robust predictive behavior.

Furthermore, the single architectures based on GRU and LSTM also obtained good forecasting accuracy and greater computational efficiency, making them viable alternatives in scenarios with time or resource constraints. The integration of weather variables contributed significantly to reducing errors and improving accuracy in practically all tested configurations, especially in recurrent networks. Based on these findings, Tests 2 and 3 will be conducted exclusively with the LSTM + GRU model, in order to investigate its sensitivity to different temporal granularities and its robustness to data clustering variability over extended horizons.

3.2. Analysis of Sensitivity to Temporal Granularity in Predictive Performance—Test 2

Test 2 aimed to assess the performance of the LSTM + GRU model at different temporal granularities, using a 1440 min dataset (equivalent to one day), which is the same dataset as used in Test 1. Datasets with time steps of 3, 6, 9, and 12 min and forecast horizons of 1 to 6 min ahead, represented as H1 to H6, respectively, were considered. This approach aimed to verify the model’s sensitivity to the temporal resolution of the input data and to explore its generalization capability under different update intervals. The numerical results of the evaluated metrics and processing times for Test 2 are provided in Appendix B of this document.

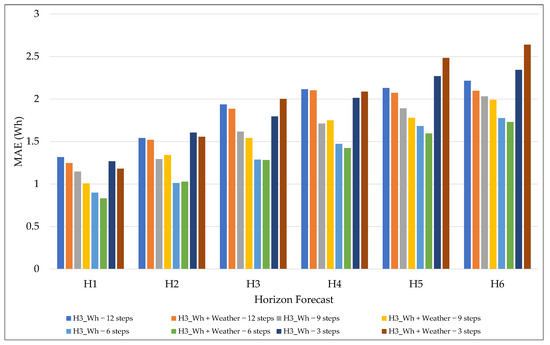

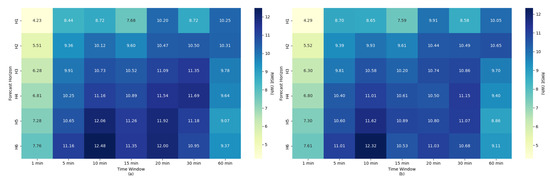

Regarding MAE, the results demonstrate that the 6-step granularity presented the best overall performance among all the configurations evaluated, regardless of the forecast horizon, as shown in Figure 5. For all horizons, this configuration resulted in consistently lower MAE values, particularly in the shorter horizons (H1 to H3), where the advantage was more significant. The integration of exogenous variables (energy and weather scenarios) further improved this performance, with particularly significant MAE reductions at the 6-step granularity for H1 to H3, highlighting the role of climate information in enhancing forecasting accuracy.

Figure 5.

MAE results for different granularities and forecast horizons.

As the granularity increased to 12 steps, a negative impact on performance was observed, with MAE exceeding 2 Wh for horizons H4, H5, and H6, even in the presence of exogenous variables. This degradation is associated with a loss of temporal resolution, which compromises the model’s ability to identify rapid variations in demand. On the other hand, models with a small granularity, such as 3 steps, although presented competitive results in the initial horizons, suffered a sharp increase in error in the longer horizons, indicating the need to balance temporal detail and generalization capability.

Overall, increasing the forecast horizon resulted in a gradual increase in MAE across all granularities, reinforcing that more distant forecasts present greater uncertainty. Even so, intermediate configurations, especially the 6-step configuration, combined with exogenous variables, maintained superior performance and greater stability across different horizons, standing out as the most suitable choice for residential energy consumption forecasting applications that demand high responsiveness and accuracy.

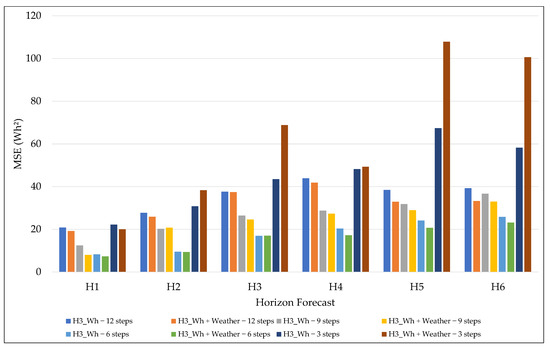

In the case of MSE, the 6-step configuration again demonstrated the most consistent performance, followed by the 9 steps, which maintains low values across nearly all forecast horizons, as shown in Figure 6. This behavior was even more evident when the model included exogenous variables (Energy + Weather), in which the MSE results associated with the 6 steps remained below those of the others, particularly for short and medium horizons (H1 to H4). The 3-step configuration presented the worst results across all horizons, suffering rapid degradation as the horizon increased, reaching significant error peaks, especially when combined with exogenous variables for more extended forecasts, which differs from the other temporal resolutions analyzed.

Figure 6.

MSE results for different granularities and forecast horizons.

In contrast, the higher granularity, 12 steps, resulted in a progressive increase in MSE up to H4, reducing errors for H5 and H6, especially when exogenous variables were added. Overall, the analysis reaffirms that the combination of intermediate windows, highlighted by using 6 steps, with exogenous variables provides the best balance between temporal detail and model robustness, ensuring consistently lower MSEs across different forecast horizons.

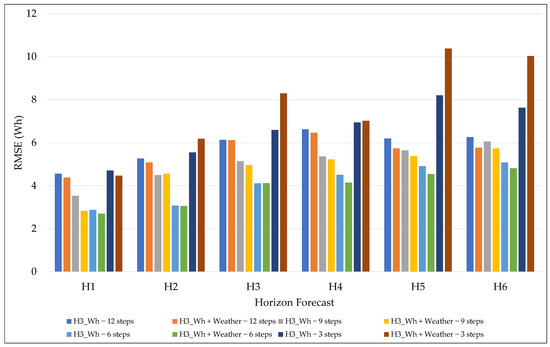

When analyzing the RMSE metric, as shown in Figure 7, the 6-step granularity remained the most efficient configuration for all horizons, presenting consistently lower values in both the scenario with only endogenous variables and in the scenario combined with exogenous variables. The presence of weather data in the model reinforced this trend, providing noticeable error reductions even for longer horizons, where the loss of accuracy is usually more pronounced, except for the 3-step granularity.

Figure 7.

RMSE results for different granularities and forecast horizons.

An interesting aspect is that, although short horizons naturally show lower RMSE values, the error growth rate over the horizon was less pronounced for the 6-, 9-, and 12-step granularities, especially for the 12 steps when combined with exogenous variables, with a reduction in RMSEs for H5 and H6 compared to H4, as also seen with MSE in Figure 6. This suggests a greater ability of the model to preserve predictive stability as the forecast interval increases, thereby avoiding the explosive growth of errors observed in the 3-step approach. Another relevant point is the atypical behavior of the 3-step granularity with exogenous variables, which recorded high RMSE peaks from horizon H2 onward. This pattern indicates that, although a high update frequency can capture instantaneous variations efficiently, the excess noise incorporated hinders extrapolation to more distant forecasts and prevents generalization.

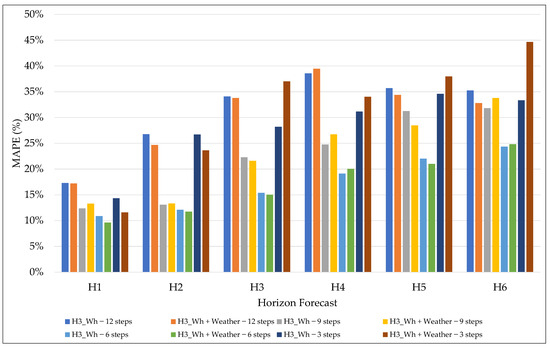

Regarding the MAPE shown in Figure 8, the 6- and 9-step granularities again proved to be the most consistent in maintaining low percentage errors, especially in the H1 to H2 horizons. Moreover, adding exogenous variables for 6 steps decreased the percentage error rate, especially for the H1 forecast horizon, compared to using only endogenous variables. This combination demonstrated greater flexibility in adapting to sudden changes in residential electrical energy consumption, resulting in more stable forecasts that are less susceptible to relative errors.

Figure 8.

MAPE results for different granularities and forecast horizons.

However, as the forecast horizon increases, as seen in H3 to H6, it is observed that, except for the 6-step granularity, the other scenarios show an increase in MAPE, reflecting the greater uncertainty associated with more extended forecasts. Even so, the 6-step configuration maintained high performance compared to the others, with more controlled errors even over long horizons. In contrast, for 3-step granularity showed a significant increase in MAPE from horizon H2 to H6, evidencing a loss of robustness as the forecast moves away from the observation point. Additionally, broader granularities, such as 12 steps, failed to reduce the percentage error to competitive levels for short and longer horizons. Therefore, the MAPE analysis corroborates the fact that intermediate granularities, particularly the 6-step granularity associated with exogenous data, offer the best balance between responsiveness and percentage stability across different horizons.

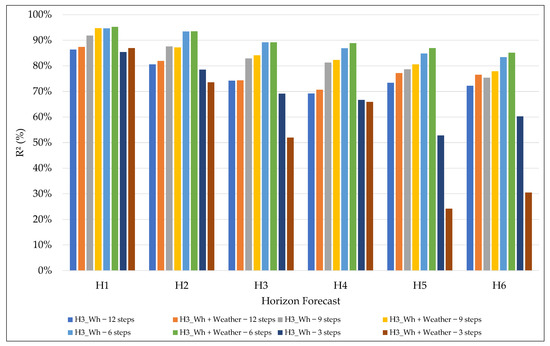

Finally, regarding the coefficient of determination R2, the results in Figure 9 denote a consistent trend, in which higher values are associated with short horizons (H1 and H2) and intermediate granularities of 6 and 9 steps, particularly the 6 steps configuration, both in the scenario with only endogenous variables (94.62%) and in the one that includes exogenous variables (95.25%). It is also observed that the inclusion of weather variables has brought significant improvement in the results for horizons H4 to H6 over 6 steps, indicating a strong capacity of the model to explain the variability in energy consumption.

Figure 9.

R2 results for different granularities and forecast horizons.

However, it was observed that as the forecast horizon increases, there is a progressive decline in R2 for all granularities, reflecting the model’s greater difficulty in maintaining high explanatory power for longer forecast horizons. This effect is more pronounced at extreme granularities, as in a 12-step configuration, the performance loss is notable, while 3-step granularities present abrupt horizons for long horizons, especially when combined with exogenous variables. This behavior is possibly related to overfitting at short horizons and difficulty generalizing to more distant time windows. This behavior also helps explain why the 6-step granularity achieved superior performance, which can be attributed to the typical dynamics of residential energy consumption. This interval captures short-term variations caused by appliance operation cycles (e.g., showers, lighting, and thermal comfort equipment), while filtering out instantaneous fluctuations that occur at very short time resolutions.

The results reinforce that the 6-step granularity with exogenous variables offers the best compromise between high explanatory power and stability over different horizons. This balance suggests that, for residential applications requiring reliable forecasts, choosing this configuration provides stability with relatively minor errors, preserving accuracy even when the forecast extends into the future.

In this sense, the set of analyses performed shows that the 6-step granularity presented the best predictive performance across all metrics evaluated (MAE, MSE, RMSE, MAPE, and R2), both in the scenario with only endogenous variables and in the scenario with the inclusion of exogenous variables. Therefore, the subsequent analysis, referred to as Test 3, will be conducted exclusively with the 6-step configuration to investigate its behavior and potential practical applications further. It should be noted that the complete results for all granularities will be made available as Supplementary Material, ensuring the transparency of the study and allowing other researchers to explore them in specific or comparative contexts.

3.3. Impact of Temporal Aggregation on Multi-Horizon Predictive Performance—Test 3

Test 3 aimed to investigate the impact of temporal aggregation on the predictive performance of the LSTM + GRU model, considering different time windows aggregation applied to the input data for forecasting electrical energy consumption for a single household. Based on the results of Test 2, which indicated that the 6-step granularity was the most efficient across all evaluated metrics, this experiment was restricted exclusively to this configuration to further assess the effect of temporal aggregation. To this end, aggregation windows of 1, 5, 10, 15, 20, 30, and 60 min were evaluated, with forecast horizons ranging from H1 to H6, corresponding to 1 to 6 steps ahead, respectively. The processing time results for the Test 3 simulations are available in Appendix C of this document.

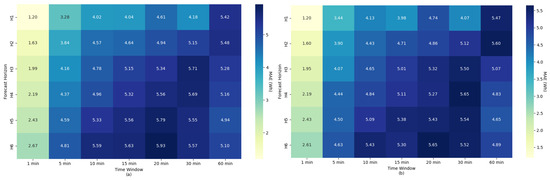

The following analysis is organized by performance metric, starting with MAE and followed by MSE, RMSE, MAPE, and R2. For each metric, the patterns observed across different time windows aggregation and forecast horizons are discussed, highlighting the role of including exogenous variables (Energy + Weather scenario) in modulating the results. In this sense, the results presented in Figure 10 illustrate the MAE, which increases as the temporal aggregation window increases, both in the scenario with endogenous data only Figure 10a and in the scenario combined with exogenous variables Figure 10b. In both cases, the smallest aggregation window (1 min) presented the best performance for all forecast horizons, with MAE varying between 1.20 Wh (H1) and 2.67 Wh (H6) in scenario Figure 10a, and between 1.20 Wh (H1) and 2.61 Wh (H6) in scenario Figure 10b.

Figure 10.

Results of MAE for different time windows aggregation and forecast horizons, with (a) only for energy data and (b) for the integration of weather data.

The integration of exogenous variables in scenario Figure 10b provided noticeable reductions in MAE across various time windows and horizon combinations, particularly for intermediate and long horizons. In the analysis of 15 min windows and horizons H4 to H6, the difference between the two scenarios was up to 0.3 Wh, indicating that weather information helped explain demand variations even with the loss of temporal resolution caused by aggregation. In contrast, for very short windows (1 and 5 min), the gain from adding exogenous variables was less pronounced, suggesting that in these cases, endogenous data already provide sufficient information to capture the patterns of energy consumption.

Another relevant aspect is the impact of high aggregation (30 and 60 min), which resulted in a sharp increase in the MAE, reaching 5.48 Wh in scenario Figure 10a and 5.60 Wh in scenario Figure 10b for H2. This increase reflects excessive data smoothing, which compromises the model’s sensitivity to short-term variations, reducing its forecasting ability over multiple horizons. Even under these conditions, the presence of exogenous variables helped mitigate the error at some horizons, as observed at 60 min for H3 to H6.

Next, in Figure 11, which illustrates the results of the MSE analysis, a behavior similar to that observed in the MAE was identified, with a consistent increase as the aggregation window widens, regardless of the forecast horizon. In both scenarios evaluated, endogenous data only Figure 11a and combined with exogenous variables Figure 11b, the lowest MSE values are concentrated in the shorter windows (1 and 5 min), especially in the H1 and H2 horizons, indicating that greater temporal resolution is necessary for capturing rapid variations in residential electrical energy consumption and minimizing large forecast deviations.

Figure 11.

Results of MSE for different time windows aggregation and forecast horizons, with (a) only for energy data and (b) for the integration of weather data.

However, the integration of exogenous variables in scenario Figure 11b brought improvements to the variations in medium and long horizons, especially in aggregation windows longer than 10 min. In cases such as H3 to H6, with windows of 15 to 30 min, the reduction in MSE was greater in many cases than in the 5 and 10 min configuration for scenario Figure 11a, indicating that weather information plays a compensatory role in the loss of temporal detail.

The progressive increase in data windows denotes the impact of data aggregation, with the MSE exceeding 100 Wh2 in the H1 and H2 horizons for 60 min, even in the scenario with exogenous variables. This trend reinforces that larger aggregations tend to compromise the model’s ability to react to abrupt fluctuations in electrical energy consumption. However, for horizons H3 to H6 for the 60 min time window, the MSE results decreased with each step, which differs from the results for the other aggregation windows. This may have occurred because the aggregation smoothed out the random consumption peaks that are more pronounced at lower temporal resolutions. Nevertheless, in an overall analysis of the MSE results, compared to scenario Figure 11a, it is observed that the forecast considering climate variables maintains slightly more controlled errors for all configurations.

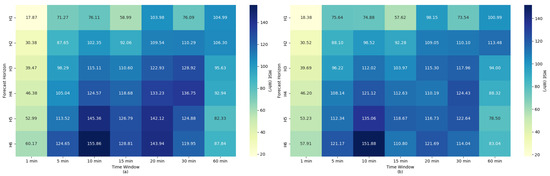

Another analysis, performed and demonstrated in Figure 12, shows that the RMSE behavior follows the trend observed in the MSE, with lower values concentrated in the time windows of less aggregation (1 and 5 min) and in the shorter horizons (H1 and H2). In the scenario with only endogenous variables Figure 12a, the error evolved gradually as the forecast horizon increased, reaching peaks above 12 Wh for combinations of long windows and distant horizons (H5 and H6).

Figure 12.

Results of RMSE for different time windows aggregation and forecast horizons, with (a) only for energy data and (b) for the integration of weather data.

As in previous analyses, the inclusion of exogenous variables Figure 12b provided consistent reductions in RMSE in almost all cases, highlighting forecast horizons H3 to H6 and windows of 15 to 30 min, where the decrease was sufficient to approximate the results of higher temporal resolution configurations. Although the general behavior is an increase in RMSE with the expansion of the time windows and forecast horizons, it is observed that the scenario with exogenous variables smooths this increase, especially at longer horizons, reducing the difference between the 1 min and 60 min windows. Thus, the RMSE corroborates the conclusion that the use of complementary data contributes to preserving accuracy under less ideal temporal granularity conditions.

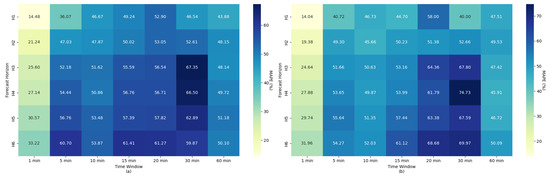

However, it was identified that MAPE presents greater sensitivity between the different aggregation levels and forecast horizons when compared to the previous metrics, as observed in Figure 13. In the scenario with only endogenous variables Figure 13a, the smallest percentage errors are concentrated in the 1 min window combined with H1 and H2 horizons, reaching values of 14.48% and 21.24%, respectively. As the aggregation time window widens in scenario Figure 13a, the percentage error increases significantly, exceeding 60% for long horizons and 30 min aggregations, which indicates a considerable loss of proportionality between predicted and observed values.

Figure 13.

Results of MAPE for different time windows aggregation and forecast horizons, with (a) only for energy data and (b) for the integration of weather data.

The integration of exogenous variables Figure 13b resulted in significant reductions in several configurations, particularly for horizons in H3 and H4, as well as windows of 5 to 15 and 60 min, indicating that weather information helps mitigate the effects of temporal resolution loss. Even so, across several horizons and with the different time windows tested, the percentage improvement was moderate, possibly due to MAPE’s greater sensitivity to small deviations at low electrical energy consumption values.

Another important point to highlight was the occurrence of localized peaks, such as in the 20 and 30 min time windows for medium and long horizons, which maintained high MAPE values even in scenario Figure 13b with exogenous variables, revealing that there are limits to the gains provided by including additional data when the granularity is reduced. Overall, the MAPE results suggest that the combination of short and medium windows with exogenous information results in better percentage performance, while configurations with high aggregation tend to compromise the proportionality of the improvements.

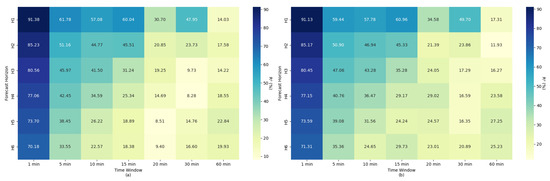

Finally, the analysis of the R2 results, illustrated in Figure 14, shows that the coefficient of determination’s performance strongly depends on both the forecast horizon and the time granularity. In the scenario with only endogenous variables Figure 14a, the highest R2 values are concentrated in short windows (1 and 5 min) and initial horizons of H1 and H2, reaching up to 91.38% for H1 and 1 min aggregation. As the horizon increases, a sharp decline in explanatory power is observed, especially for high aggregations (≥15 min), where values often fall below 25%.

Figure 14.

Results of R2 for different time windows aggregation and forecast horizons, with (a) only for energy data and (b) for the integration of weather data.

The inclusion of exogenous variables Figure 14b in the residential electrical energy consumption forecasting test yielded specific performance gains, highlighting for horizons H3 to H6 and time windows aggregations of 5 to 60 min (except H4 for 5 min), mitigating the loss of explanatory power under these conditions. However, even with weather variables, the model was unable to maintain a high R2 in scenarios with low temporal resolution and long horizons, indicating that the signal degradation due to excessive aggregation cannot be fully offset by additional information.

Therefore, the contrast between short and long windows is striking, where, while the former preserve greater variability and allow for more accurate model adjustment, the latter tend to oversmooth the series, making it challenging to capture fluctuations relevant to forecasting. This tendency is evidenced by the relative difference between scenarios Figure 14a,b, where the advantage of exogenous variables is more visible in configurations with intermediate and long aggregation, but less pronounced at extremes of granularity.

Thus, Test 3 demonstrated that the performance of the model applied to residential electrical energy consumption forecasting is strongly conditioned by the choice of the time window aggregation and the forecast horizons. The analyses revealed that short windows (1 to 5 min) offer a significant advantage in capturing rapid variations, as reflected in lower MAE, MSE, RMSE, and MAPE values, along with higher R2 values, particularly for short horizons (H1 and H2). In addition, the integration of exogenous variables contributed to additional performance gains in almost all scenarios, similarly to that obtained by [31], mitigating the degradation observed in longer horizons and, in some cases, partially compensating for the loss of temporal detail associated with moderate aggregation windows (15 to 30 min). However, even with such additional information, very extensive aggregations (≥30 min) associated with distant forecasts (H5 and H6) resulted in sharp reductions in explanatory power and significant increases in errors, demonstrating that there is a limit to mitigating the losses imposed by low temporal resolution.

4. Conclusions

Electricity demand in residential environments has become a subject of study, and anticipating demand has become essential to improve energy management. Therefore, this study investigated the use of DL architectures to forecast electrical energy consumption in a single household, considering different time granularities, forecast horizons, and the inclusion of exogenous variables. The main objective was to evaluate the ability of a forecasting framework to anticipate demand patterns in high-variability scenarios, assessing forecast accuracy and computational efficiency.

Therefore, the comparison between architectures in Test 1 highlighted the superiority of the hybrid LSTM + GRU model, which performed better across all metrics evaluated, both with endogenous and exogenous variables. Despite the higher computational cost, the model demonstrated greater adaptability to complex patterns and abrupt variations, justifying its selection for subsequent tests. In Test 2, when evaluating different granularities (3, 6, 9, and 12 steps), the 6-step configuration stood out as the most efficient, reconciling temporal detail and predictive robustness, and was adopted as the reference for Test 3.

Finally, in Test 3, a longer-term dataset, totaling 30 days of continuous data, showed that short windows (1 to 5 min) offer superior performance, reflected in lower MAE, MSE, RMSE, and MAPE values, and higher R2 values, especially for short horizons (H1 and H2). The inclusion of weather variations reduced errors in almost all scenarios, especially in specific aggregations (15 to 30 min) and medium-term variations (H3 and H4). However, extensive aggregations (≥30 min) combined with long forecast horizons (H5 and H6) resulted in a significant loss of accuracy and reduced explanatory power, demonstrating that excessive smoothing limits the predictability of residential electrical energy consumption.

In conclusion, the results presented confirm that residential electrical energy consumption forecasting with DL depends critically on the choice of temporal granularity and forecast horizon. The LSTM + GRU model proved to be the most suitable for the tests performed, intermediate granularities (6 steps) provided the best balance between responsiveness and stability, and the inclusion of weather variables increased predictive robustness over long horizons. It should be acknowledged that the framework was designed and validated using data from a single household, and therefore, its applicability to broader residential scenarios remains to be further explored. As a proposal for future research directions, the results obtained provide support for the development of intelligent demand forecasting systems in residential environments, with applications in DSM, home automation, and integration with DERs, in addition to establishing guidelines for future research focused on the scalability of models for multiple homes and microgrids.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/en18225885/s1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.K.H. and M.V.H.R.; methodology, B.K.H., M.V.H.R. and A.d.S.L.; software, B.K.H. and A.d.S.L.; validation, B.K.H., M.V.H.R. and A.d.S.L.; formal analysis, B.K.H., L.M.I., H.B.S. and R.J.R.; investigation, H.B.S., D.P.C. and P.L.; resources, M.K. and R.J.R.; data curation, M.V.H.R., A.d.S.L., L.M.I. and H.B.S.; writing—original draft preparation, B.K.H. and M.V.H.R.; writing—review and editing, A.d.S.L., L.M.I., H.B.S., D.P.C., P.L., M.K. and R.J.R.; visualization, L.M.I., D.P.C., P.L., M.K. and R.J.R.; supervision, M.K. and R.J.R.; project administration, L.M.I., D.P.C. and P.L.; funding acquisition, M.K. and R.J.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work has been fully funded by the project DSM—Previsão Descentralizada de Demanda de Energia Fotovoltaica com Machine Learning supported by Future Grid—Centro e Competência Embrapii Lactec em Smart Grid e Eletromobilidade, with financial resources from the PPI HardwareBR of the MCTI grant number 054/2023, signed with EMBRAPII.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study might be available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| PV | Photovoltaic |

| EV | Electric Vehicle |

| DR | Demand Response |

| DERs | Distributed Energy Resources |

| DSM | demand side management |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| DL | Deep Learning |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| BiLSTM | Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory |

| SA | Self-Attention |

| LSTM | Long Short-Term Memory |

| GRU | Gated Recurrent Unit |

| ConvLSTM | Convolutional Long-Short-Term Memory |

| RNN | Recurrent Neural Network |

| GELU | Gaussian Error Linear Units |

| MAE | Mean Absolute Error |

| MSE | Mean Squared Error |

| RMSE | Root Mean Squared Error |

| MAPE | Mean Absolute Percentage Error |

| R2 | Coefficient of Determination |

Appendix A

Table A1.

Forecasting model configurations.

Table A1.

Forecasting model configurations.

| Forecast Model | Layer | Description |

|---|---|---|

| LSTM | Input | Temporal sequence with time steps and the total number of variable features at each step |

| Hidden | 3 LSTM layers (128 → 256 → 128 neurons) with GELU activation and 20% Dropout between them | |

| 1 dense intermediate layer with 64 neurons and GELU activation | ||

| Output | Dense layer with variable neurons according to the forecast horizon | |

| GRU | Input | Temporal sequence with time steps and the total number of variable features at each step |

| Hidden | 3 GRU layers (128 → 256 → 128 neurons) with GELU activation and 20% Dropout between them | |

| 1 dense intermediate layer with 64 neurons and GELU activation | ||

| Output | Dense layer with variable neurons according to the forecast horizon | |

| CNN | Input | Temporal sequence with time steps and the total number of variable features at each step |

| Hidden | 1 convolutional layer with 128 filters, kernel size 3, and GELU activation | |

| 1 pooling layer with a window size of 2 | ||

| 1 layer of flatten to transform the output into a one-dimensional vector | ||

| 1 dense intermediate layer with 64 neurons and GELU activation | ||

| Output | Dense layer with variable neurons according to the forecast horizon | |

| Transformer | Input | Temporal sequence with time steps and the total number of variable features at each step. |

| Hidden | 1 Transformer block with 16 attention heads (multi-head attention), embedding dimension equal to the number of features, and a feedforward layer with 128 neurons and GELU activation | |

| 1 layer of flatten to transform the output into a one-dimensional vector | ||

| 1 dense intermediate layer with 64 neurons and GELU activation | ||

| Output | Dense layer with variable neurons according to the forecast horizon | |

| LSTM + GRU | Input | Temporal sequence with time steps and the total number of variable features at each step |

| Hidden | 2 LSTM layers (128 → 256 neurons) with GELU activation and 20% Dropout between them | |

| 2 GRU layers (128 → 256 neurons) with GELU activation and 20% Dropout between them | ||

| 1 dense intermediate layer with 64 neurons and GELU activation | ||

| Output | Dense layer with variable neurons according to the forecast horizon | |

| LSTM + CNN | Input | Temporal sequence with time steps and the total number of variable features at each step. |

| Hidden | 1 convolutional layer with 128 filters, kernel size 3, and GELU activation | |

| 1 pooling layer with a window size of 2 | ||

| 3 LSTM layers (128 → 256 → 128 neurons) with GELU activation and 20% Dropout between them | ||

| 1 dense intermediate layer with 64 neurons and GELU activation | ||

| Output | Dense layer with variable neurons according to the forecast horizon | |

| LSTM + Transformer | Input | Temporal sequence with time steps and the total number of variable features at each step. |

| Hidden | 1 Transformer block with 16 attention heads (multi-head attention), embedding dimension equal to the number of features, and a feedforward layer with 128 neurons and GELU activation | |

| 3 LSTM layers (128 → 256 → 128 neurons) with GELU activation and 20% Dropout between them | ||

| 1 dense intermediate layer with 64 neurons and GELU activation | ||

| Output | Dense layer with variable neurons according to the forecast horizon | |

| GRU + CNN | Input | Temporal sequence with time steps and the total number of variable features at each step. |

| Hidden | 1 convolutional layer with 128 filters, kernel size 3, and GELU activation | |

| 1 pooling layer with a window size of 2 | ||

| 3 GRU layers (128 → 256 → 128 neurons) with GELU activation and 20% Dropout between them | ||

| 1 dense intermediate layer with 64 neurons and GELU activation | ||

| Output | Dense layer with variable neurons according to the forecast horizon | |

| GRU + Transformer | Input | Temporal sequence with time steps and the total number of variable features at each step. |

| Hidden | 1 Transformer block with 16 attention heads (multi-head attention), embedding dimension equal to the number of features, and a feedforward layer with 128 neurons and GELU activation | |

| 3 GRU layers (128 → 256 → 128 neurons) with GELU activation and 20% Dropout between them | ||

| 1 dense intermediate layer with 64 neurons and GELU activation | ||

| Output | Dense layer with variable neurons according to the forecast horizon | |

| CNN + Transformer | Input | Temporal sequence with time steps and the total number of variable features at each step |

| Hidden | 1 convolutional layer with 128 filters, kernel size 3, and GELU activation | |

| 1 pooling layer with a window size of 2 | ||

| 1 Transformer block with 16 attention heads (multi-head attention), embedding dimension equal to the number of features, and a feedforward layer with 128 neurons and GELU activation | ||

| 1 layer of flatten to transform the output into a one-dimensional vector | ||

| 1 dense intermediate layer with 64 neurons and GELU activation | ||

| Output | Dense layer with variable neurons according to the forecast horizon |

Appendix B

Table A2.

Numerical results of Figure 5, Figure 6, Figure 7, Figure 8 and Figure 9, for residential energy consumption data.

| Energy—12 steps | ||||||

| Horizon Forecast | H1 | H2 | H3 | H4 | H5 | H6 |

| MAE | 1.3174 (14.87%) | 1.5424 (17.51%) | 1.9368 (21.83%) | 2.1160 (23.88%) | 2.1304 (23.91%) | 2.2153 (24.96%) |

| MSE | 20.8255 (26.52%) | 27.7129 (35.70%) | 37.6520 (47.85%) | 43.8723 (55.90%) | 38.4228 (48.40%) | 39.2594 (49.83%) |

| RMSE | 4.5635 (51.49%) | 5.2643 (59.75%) | 6.1361 (69.17%) | 6.6236 (74.77%) | 6.1986 (69.57%) | 6.2657 (70.59%) |

| MAPE | 17.30% | 26.78% | 34.10% | 38.57% | 35.70% | 35.25% |

| R2 | 86.32% | 80.58% | 74.17% | 69.22% | 73.33% | 72.23% |

| Time | 00:10:30:951 | 00:10:29:373 | 00:10:39:721 | 00:10:40:661 | 00:10:50:646 | 00:10:23:778 |

| Energy—9 steps | ||||||

| Horizon Forecast | H1 | H2 | H3 | H4 | H5 | H6 |

| MAE | 1.1467 (13.04%) | 1.2942 (14.45%) | 1.6177 (18.18%) | 1.7114 (19.23%) | 1.8908 (21.34%) | 2.0332 (22.93%) |

| MSE | 12.4555 (16.10%) | 20.2158 (25.20%) | 26.4176 (33.37%) | 28.7642 (36.32%) | 31.7958 (40.51%) | 36.6626 (46.62%) |

| RMSE | 3.5292 (40.12%) | 4.4962 (50.20%) | 5.1398 (57.77%) | 5.3632 (60.27%) | 5.6388 (63.65%) | 6.0550 (68.28%) |

| MAPE | 12.36% | 13.09% | 22.28% | 24.76% | 31.25% | 31.82% |

| R2 | 91.80% | 87.55% | 82.90% | 81.30% | 78.63% | 75.38% |

| Time | 00:08:10:146 | 00:08:16:371 | 00:08:08:898 | 00:08:13:986 | 00:08:11:975 | 00:08:21:995 |

| Energy—6 steps | ||||||

| Horizon Forecast | H1 | H2 | H3 | H4 | H5 | H6 |

| MAE | 0.8994 (9.92%) | 1.0124 (11.45%) | 1.2876 (14.41%) | 1.4724 (16.56%) | 1.6830 (18.89%) | 1.7760 (19.96%) |

| MSE | 8.2580 (10.05%) | 9.4775 (12.13%) | 16.9428 (21.21%) | 20.3304 (25.71%) | 24.1114 (30.37%) | 25.8469 (32.66%) |

| RMSE | 2.8737 (31.70%) | 3.0786 (34.83%) | 4.1162 (46.06%) | 4.5089 (50.70%) | 4.9103 (55.11%) | 5.0840 (57.15%) |

| MAPE | 10.86% | 12.11% | 15.40% | 19.11% | 22.03% | 24.35% |

| R2 | 94.62% | 93.39% | 89.22% | 86.88% | 84.82% | 83.40% |

| Time | 00:06:10:455 | 00:06:13:285 | 00:06:11:716 | 00:06:08:578 | 00:06:17:545 | 00:06:10:152 |

| Energy—3 steps | ||||||

| Horizon Forecast | H1 | H2 | H3 | H4 | H5 | H6 |

| MAE | 1.2689 (14.60%) | 1.6052 (18.63%) | 1.7960 (20.88%) | 2.0143 (23.13%) | 2.2703 (26.15%) | 2.3434 (26.69%) |

| MSE | 22.2060 (29.40%) | 30.8062 (41.49%) | 43.4758 (58.79%) | 48.1991 (63.56%) | 67.3599 (89.40%) | 58.1981 (75.51%) |

| RMSE | 4.7123 (54.22%) | 5.5503 (64.41%) | 6.5936 (76.67%) | 6.9426 (79.72%) | 8.2073 (94.55%) | 7.6288 (86.89%) |

| MAPE | 14.33% | 26.72% | 28.21% | 31.17% | 34.60% | 33.34% |

| R2 | 85.43% | 78.52% | 69.11% | 66.67% | 52.81% | 60.26% |

| Time | 00:03:33:740 | 00:03:29:392 | 00:03:39:514 | 00:03:38:849 | 00:03:33:208 | 00:03:40:101 |

Table A3.

Numerical results of Figure 5, Figure 6, Figure 7, Figure 8 and Figure 9, for residential energy consumption and weather data.

| Energy + Weather—12 steps | ||||||

| Horizon Forecast | H1 | H2 | H3 | H4 | H5 | H6 |

| MAE | 1.2469 (14.07%) | 1.5195 (17.25%) | 1.8864 (21.27%) | 2.1025 (23.73%) | 2.0735 (23.27%) | 2.0967 (23.62%) |

| MSE | 19.1663 (24.40%) | 25.8796 (33.34%) | 37.4359 (47.58%) | 41.8260 (53.29%) | 32.9472 (41.50%) | 33.2866 (42.25%) |

| RMSE | 4.3779 (49.40%) | 5.0872 (57.74%) | 6.1185 (68.98%) | 6.4673 (73.00%) | 5.7400 (64.42%) | 5.7695 (65.00%) |

| MAPE | 17.22% | 24.66% | 33.79% | 39.46% | 34.37% | 32.80% |

| R2 | 87.41% | 81.89% | 74.31% | 70.67% | 77.15% | 76.51% |

| Time | 00:09:00:488 | 00:09:30:617 | 00:09:51:674 | 00:09:58:480 | 00:09:55:099 | 00:09:44:538 |

| Energy + Weather—9 steps | ||||||

| Horizon Forecast | H1 | H2 | H3 | H4 | H5 | H6 |

| MAE | 1.0078 (11.46%) | 1.3422 (14.99%) | 1.5415 (17.33%) | 1.7504 (19.67%) | 1.7806 (20.10%) | 1.9909 (22.45%) |

| MSE | 8.0206 (10.36%) | 20.7760 (25.90%) | 24.5893 (31.07%) | 27.2895 (34.46%) | 28.9462 (36.88%) | 32.9725 (41.93%) |

| RMSE | 2.8321 (32.19%) | 4.5581 (50.89%) | 4.9588 (55.74%) | 5.2239 (58.70%) | 5.3802 (60.73%) | 5.7422 (64.75%) |

| MAPE | 13.28% | 13.31% | 21.61% | 26.75% | 28.46% | 33.79% |

| R2 | 94.72% | 87.21% | 84.09% | 82.27% | 80.56% | 77.88% |

| Time | 00:07:24:313 | 00:07:02:224 | 00:07:37:443 | 00:08:01:785 | 00:07:43:025 | 00:07:37:736 |

| Energy + Weather—6 steps | ||||||

| Horizon Forecast | H1 | H2 | H3 | H4 | H5 | H6 |

| MAE | 0.8318 (9.18%) | 1.0287 (11.64%) | 1.2836 (14.36%) | 1.4245 (16.02%) | 1.5968 (17.92%) | 1.7311 (19.46%) |

| MSE | 7.2917 (8.87%) | 9.3498 (11.97%) | 16.9896 (21.27%) | 17.1974 (21.75%) | 20.6872 (26.06%) | 23.1488 (29.25%) |

| RMSE | 2.7003 (29.79%) | 3.0577 (34.60%) | 4.1218 (46.12%) | 4.1470 (46.63%) | 4.5483 (51.05%) | 4.8113 (54.08%) |

| MAPE | 9.61% | 11.74% | 15.03% | 20.05% | 21.01% | 24.82% |

| R2 | 95.25% | 93.51% | 89.22% | 88.86% | 86.96% | 85.12% |

| Time | 00:05:06:929 | 00:05:04:387 | 00:05:18:982 | 00:05:35:450 | 00:05:46:969 | 00:05:48:939 |

| Energy + Weather—3 steps | ||||||

| Horizon Forecast | H1 | H2 | H3 | H4 | H5 | H6 |

| MAE | 1.1816 (13.59%) | 1.5559 (18.06%) | 2.0030 (23.29%) | 2.0884 (23.98%) | 2.4843 (28.62%) | 2.6407 (30.08%) |

| MSE | 19.9696 (26.44%) | 38.2848 (51.56%) | 68.8629 (93.11%) | 49.2743 (64.98%) | 107.8569 (143.14%) | 100.6340 (130.56%) |

| RMSE | 4.4687 (51.42%) | 6.1875 (71.81%) | 8.2984 (96.50%) | 7.0196 (80.61%) | 10.3854 (119.64%) | 10.0316 (114.26%) |

| MAPE | 11.58% | 23.64% | 37.01% | 34.03% | 37.98% | 44.67% |

| R2 | 86.90% | 73.54% | 51.92% | 65.88% | 24.16% | 30.46% |

| Time | 00:04:14:218 | 00:04:46:575 | 00:03:26:652 | 00:03:18:366 | 00:03:24:518 | 00:03:41:967 |

Appendix C

Table A4.

Test 3 processing times for residential energy consumption data.

Table A4.

Test 3 processing times for residential energy consumption data.

| Horizon | H1 | H2 | H3 | H4 | H5 | H6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Window | |||||||

| 60 min | 04:19:42:650 | 04:17:09:746 | 04:18:23:244 | 04:20:50:484 | 04:18:27:641 | 04:19:58:776 | |

| 30 min | 00:54:38:419 | 00:56:30:970 | 00:55:29:367 | 00:57:55:684 | 00:57:49:139 | 00:57:36:833 | |

| 20 min | 00:29:19:080 | 00:29:36:200 | 00:28:45:420 | 00:28:31:612 | 00:29:24:372 | 00:28:28:851 | |

| 15 min | 00:09:48:314 | 00:11:00:902 | 00:11:05:216 | 00:11:35:486 | 00:11:43:568 | 00:11:17:877 | |

| 10 min | 00:07:42:988 | 00:08:05:618 | 00:07:47:488 | 00:07:54:815 | 00:08:04:402 | 00:07:40:313 | |

| 5 min | 00:05:51:416 | 00:05:58:479 | 00:05:51:141 | 00:05:54:464 | 00:06:00:164 | 00:06:06:339 | |

| 1 min | 00:03:18:091 | 00:03:15:255 | 00:03:22:423 | 00:03:11:999 | 00:03:09:263 | 00:03:20:628 | |

Table A5.

Test 3 processing times for residential energy consumption and weather data.

Table A5.

Test 3 processing times for residential energy consumption and weather data.

| Horizon | H1 | H2 | H3 | H4 | H5 | H6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Window | |||||||

| 60 min | 04:42:18:532 | 04:45:54:680 | 04:39:54:860 | 04:39:25:421 | 04:39:23:861 | 04:42:49:879 | |

| 30 min | 00:46:35:265 | 00:55:48:720 | 00:57:20:826 | 00:59:00:203 | 00:56:50:836 | 00:55:14:577 | |

| 20 min | 00:25:01:655 | 00:27:50:862 | 00:27:42:582 | 00:27:54:861 | 00:27:51:686 | 00:27:53:312 | |

| 15 min | 00:11:02:021 | 00:11:34:373 | 00:09:58:552 | 00:09:53:987 | 00:10:11:814 | 00:09:59:662 | |

| 10 min | 00:08:55:962 | 00:07:58:126 | 00:07:52:185 | 00:08:05:517 | 00:08:12:003 | 00:08:09:754 | |

| 5 min | 00:05:37:861 | 00:05:47:894 | 00:05:11:229 | 00:05:15:895 | 00:05:41:041 | 00:06:03:201 | |

| 1 min | 00:03:23:510 | 00:03:23:178 | 00:03:19:360 | 00:03:26:151 | 00:03:22:166 | 00:03:15:723 | |

References

- Bai, Z. Residential Electricity Prediction Based on GA-LSTM Modeling. Energy Rep. 2024, 11, 6223–6232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, K. Adaptive Bi-Directional LSTM Short-Term Load Forecasting with Improved Attention Mechanisms. Energies 2024, 17, 3709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.P.; Wu, F. Predicting Residential Electricity Consumption Using CNN-BiLSTM-SA Neural Networks. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 71555–71565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aouad, M.; Hajj, H.; Shaban, K.; Jabr, R.A.; El-Hajj, W. A CNN-Sequence-to-Sequence Network with Attention for Residential Short-Term Load Forecasting. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2022, 211, 108152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alanazi, M.D.; Saeed, A.; Islam, M.; Habib, S.; Sherazi, H.I.; Khan, S.; Shees, M.M. Enhancing Short-Term Electrical Load Forecasting for Sustainable Energy Management in Low-Carbon Buildings. Sustainability 2023, 15, 16885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajjad, M.; Khan, Z.A.; Ullah, A.; Hussain, T.; Ullah, W.; Lee, M.Y.; Baik, S.W. A Novel CNN-GRU-Based Hybrid Approach for Short-Term Residential Load Forecasting. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 143759–143768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, Z.A.; Ullah, A.; Ul Haq, I.; Hamdy, M.; Maria Maurod, G.; Muhammad, K.; Hijji, M.; Baik, S.W. Efficient Short-Term Electricity Load Forecasting for Effective Energy Management. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2022, 53, 102337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, W.; Liu, H.; Zhang, X.; Zeng, Y.; Ling, X. Short-Term Residential Load Forecasting Based on the Fusion of Customer Load Uncertainty Feature Extraction and Meteorological Factors. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.Y.; Cho, S.B. Predicting Residential Energy Consumption Using CNN-LSTM Neural Networks. Energy 2019, 182, 72–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balakumar, P.; Vinopraba, T.; Chandrasekaran, K. Deep Learning Based Real Time Demand Side Management Controller for Smart Building Integrated with Renewable Energy and Energy Storage System. J. Energy Storage 2023, 58, 106412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gozuoglu, A.; Ozgonenel, O.; Gezegin, C. CNN-LSTM Based Deep Learning Application on Jetson Nano: Estimating Electrical Energy Consumption for Future Smart Homes. Internet Things 2024, 26, 101148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswal, S.R.; Choudhury, T.R.; Panda, B.; Mishra, S. An Improved IoT Based Hybrid Predictive Load Forecasting Model for a Greenhouse Integrated with Demand Side Management. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 108446–108465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, N.; Yang, F.; Mo, Y.; Zeng, Y.; Zhou, X.; Yan, K.; Ma, X. Highly Accurate Energy Consumption Forecasting Model Based on Parallel LSTM Neural Networks. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2022, 51, 101442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moveh, S.; Merchán-Cruz, E.A.; Abuhussain, M.; Dodo, Y.A.; Alhumaid, S.; Alhamami, A.H. Deep Learning Framework Using Transformer Networks for Multi Building Energy Consumption Prediction in Smart Cities. Energies 2025, 18, 1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masood, Z.; Gantassi, R.; Ardiansyah; Choi, Y. A Multi-Step Time-Series Clustering-Based Seq2Seq LSTM Learning for a Single Household Electricity Load Forecasting. Energies 2022, 15, 2623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, J.; Knottenbelt, W. The UK-DALE Dataset, Domestic Appliance-Level Electricity Demand and Whole-House Demand from Five UK Homes. Sci. Data 2015, 2, 150007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhussein, M.; Aurangzeb, K.; Haider, S.I. Hybrid CNN-LSTM Model for Short-Term Individual Household Load Forecasting. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 180544–180557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irankhah, A.; Yaghmaee, M.H.; Ershadi-Nasab, S. Optimized Short-Term Load Forecasting in Residential Buildings Based on Deep Learning Methods for Different Time Horizons. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 84, 108505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, W.; Dong, Z.Y.; Jia, Y.; Hill, D.J.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, Y. Short-Term Residential Load Forecasting Based on LSTM Recurrent Neural Network. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2019, 10, 841–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhoj, N.; Singh Bhadoria, R. Time-Series Based Prediction for Energy Consumption of Smart Home Data Using Hybrid Convolution-Recurrent Neural Network. Telemat. Inform. 2022, 75, 101907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Severiche-Maury, Z.; Uc-Rios, C.E.; Arrubla-Hoyos, W.; Cama-Pinto, D.; Holgado-Terriza, J.A.; Damas-Hermoso, M.; Cama-Pinto, A. Forecasting Residential Energy Consumption with the Use of Long Short-Term Memory Recurrent Neural Networks. Energies 2025, 18, 1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mubarak, H.; Stegen, S.; Bai, F.; Abdellatif, A.; Sanjari, M.J. Enhancing Interpretability in Power Management: A Time-Encoded Household Energy Forecasting Using Hybrid Deep Learning Model. Energy Convers Manag. 2024, 315, 118795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]