Enhanced Three-Phase Inverter Control: Robust Sliding Mode Control with Washout Filter for Low Harmonics

Abstract

1. Introduction

- The study introduces a hybrid control structure that integrates Sliding Mode Control (SMC) with a Washout Filter to improve the performance of three-phase inverters. This method offers enhanced robustness against disturbances and load variations, and achieves lower harmonic distortion compared to traditional SMC and PID control methods. The approach is particularly effective for inverters operating under variable RL, unbalanced, and nonlinear loads, producing a pure sine waveform with reduced harmonics, an area not widely covered in existing literature.

- The proposed controller requires only one parameter for implementation, simplifying use while achieving performance similar to PID control. It is independent of system parameters, unlike other controllers. Simulations show it is robust to load parameter variations, with no need for new settings.

- The proposed method offers robustness to external disturbances such as short circuits and power fluctuations by maintaining stable inverter output. A systematic methodology for tuning the control gain and filter cutoff frequency is established to balance transient speed and steady-state smoothness. A formal Lyapunov-based stability analysis is provided for the integrated control law.

2. Materials and Methods

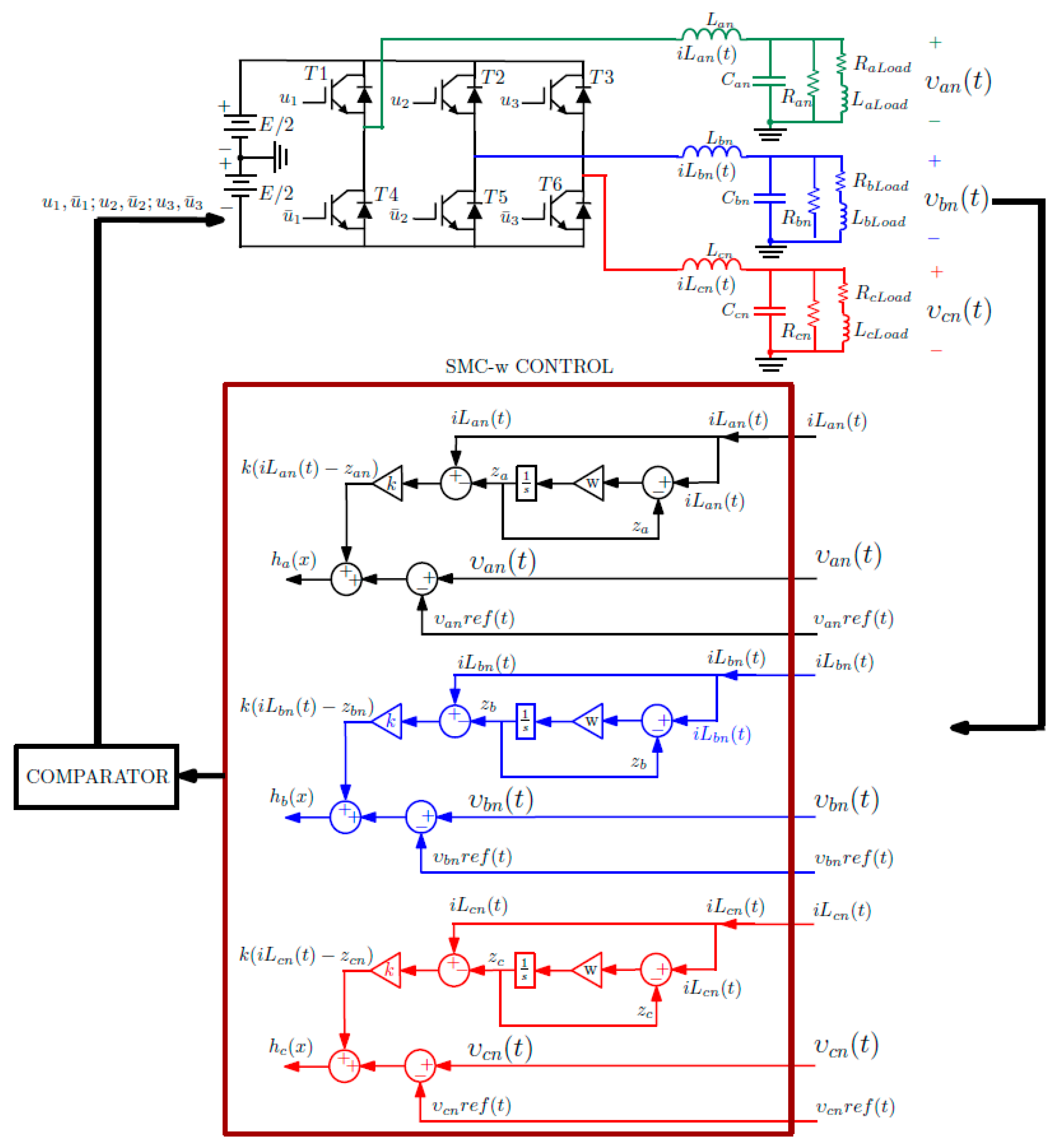

2.1. Three-Phase DC-AC Inverter

2.2. Washout Filter

2.3. Sliding Mode Control

2.4. Parameters and Signals

2.4.1. Selection of the Sliding Gain ()

2.4.2. Influence of the Washout Filter Frequency ()

3. Results

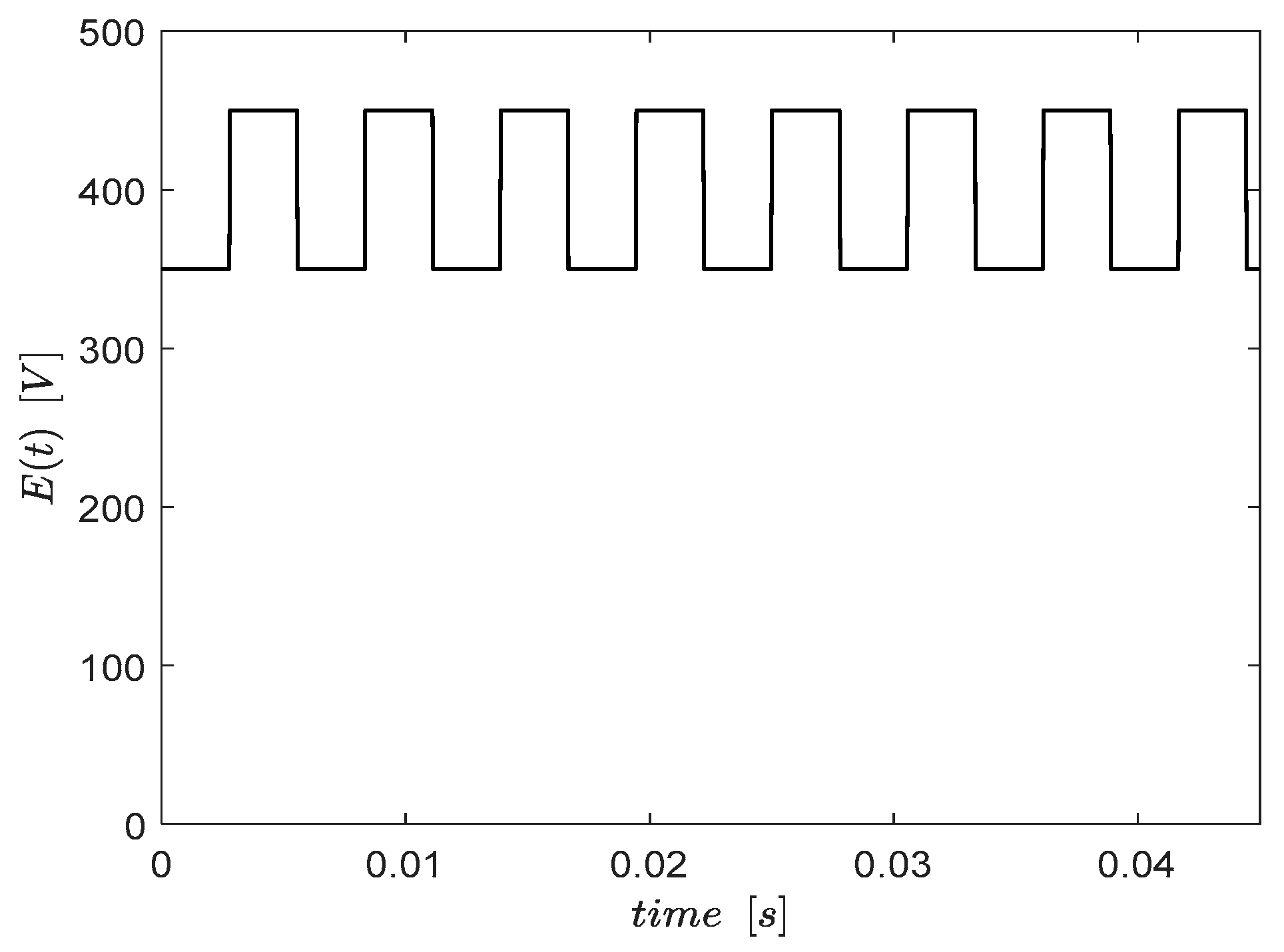

3.1. Parameters for the Tests

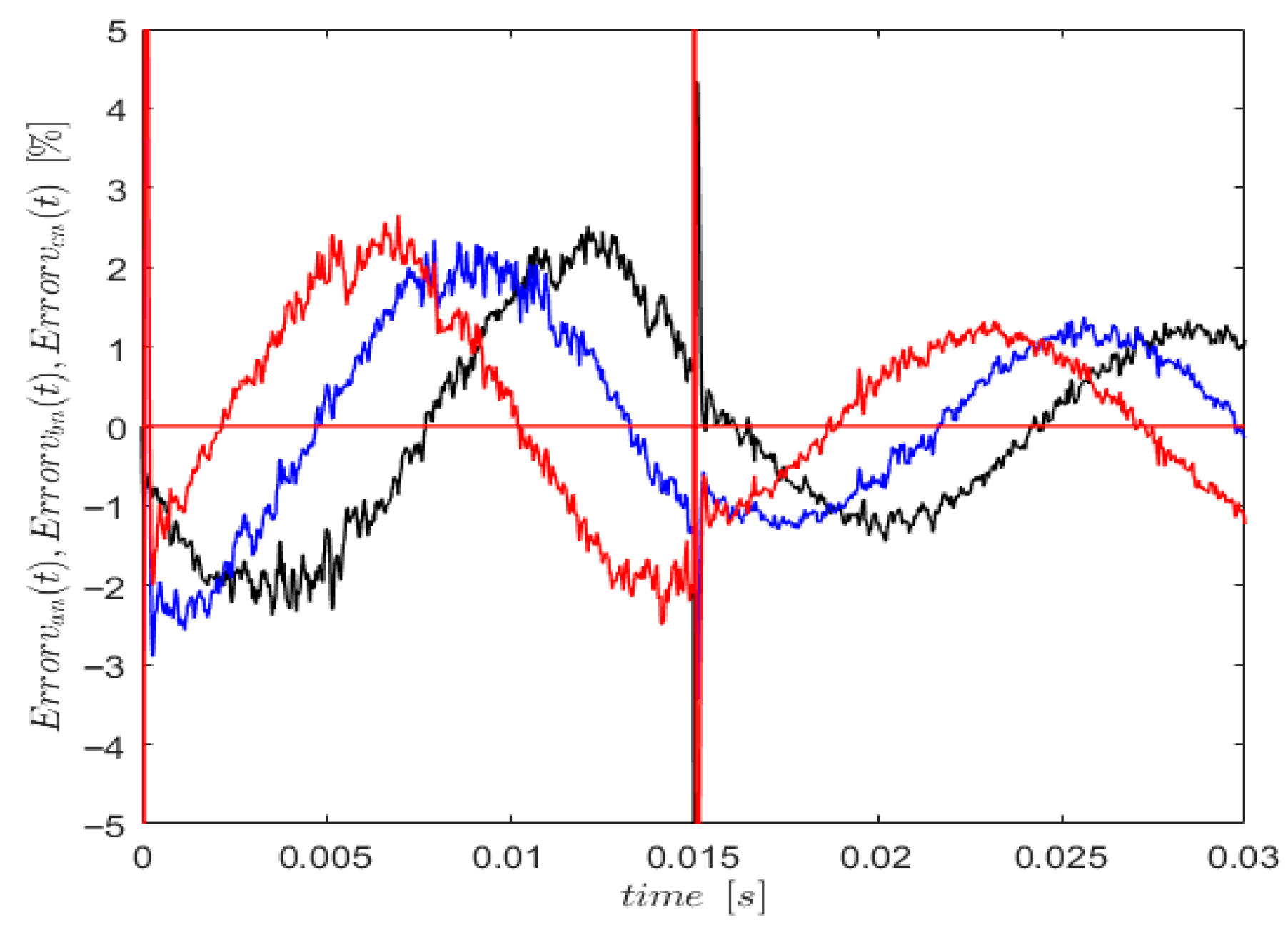

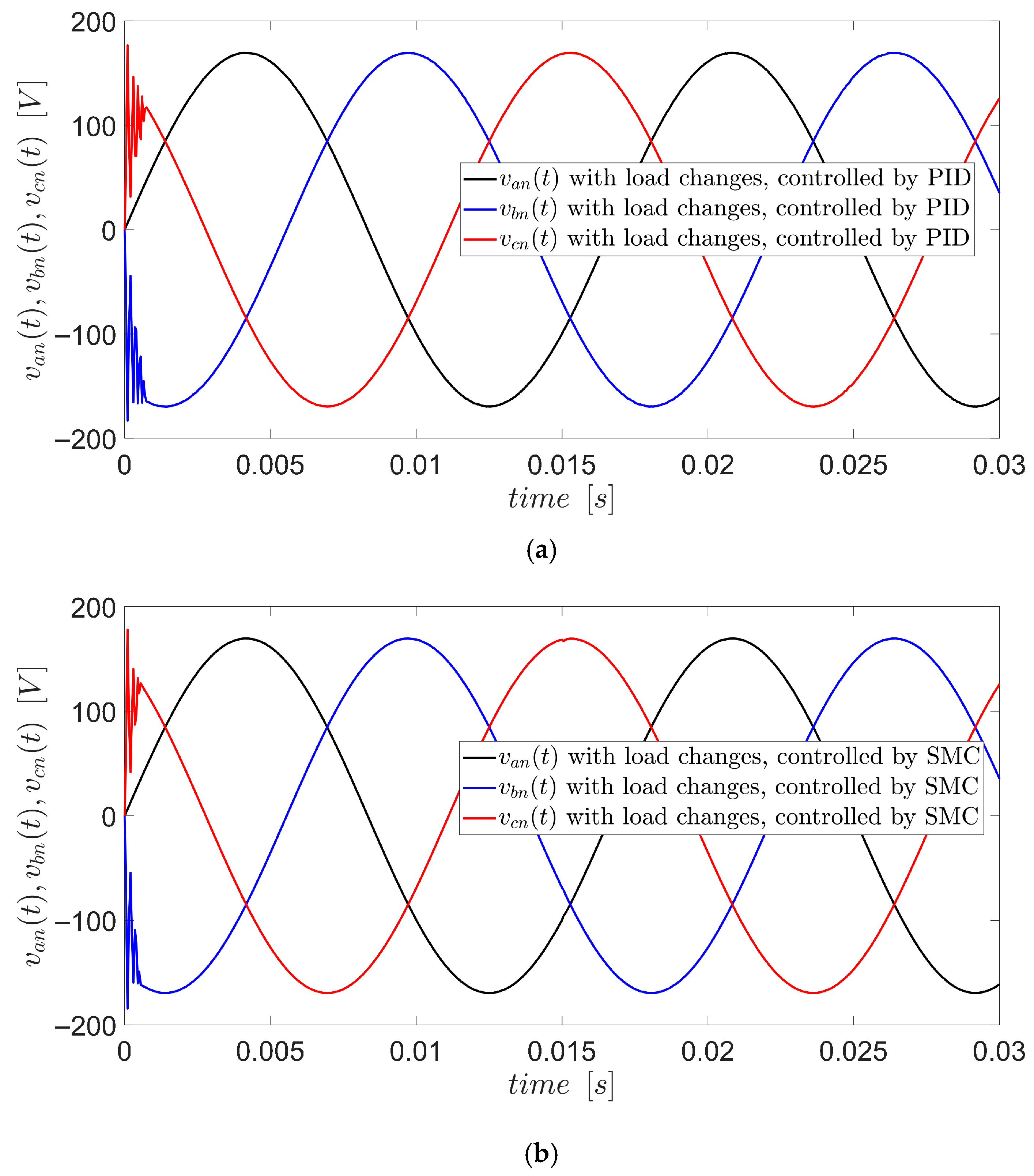

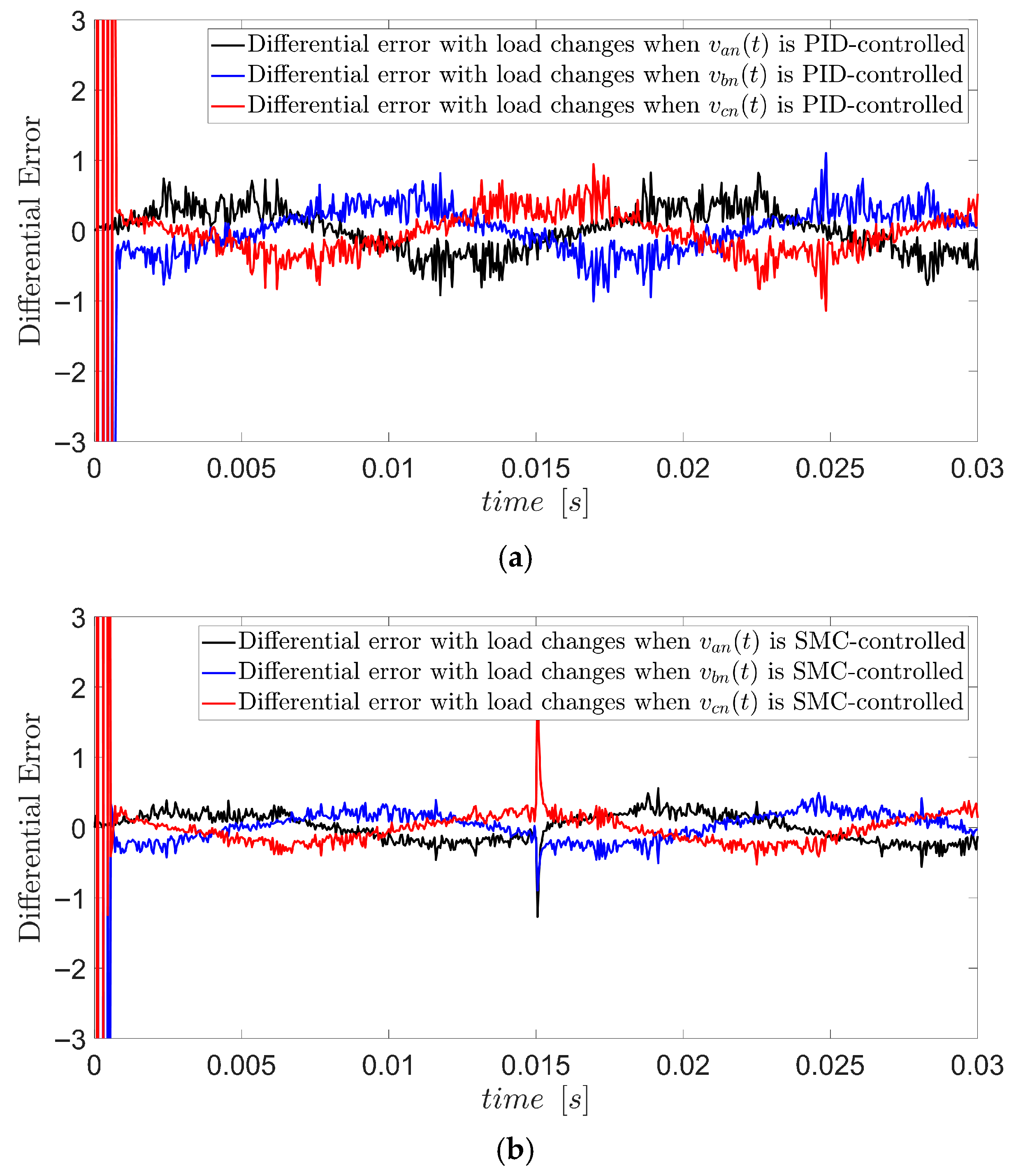

3.2. Load Change

3.3. Frequency Change in the Reference Signal

3.4. Voltage Amplitude Change

3.5. Comparison of Performance Between SMC-w and PID-Controlled Systems Under Load Variations (RL)

3.6. Computational Complexity and Implementation Feasibility (SMC–Washout vs. PID)

3.6.1. Operation Count at 20 kHz

3.6.2. Memory Footprint and Latency

3.6.3. Practical Implications

3.7. Behavior of the System Controlled with SMC Under Short Circuits

3.8. SMC-w Controlled System Response to Unbalanced Loads in a Three-Phase System

3.9. SMC-w Controlled System Response to Unbalanced Nonlinear Load Transitions in a Three-Phase System

4. Conclusions

- The SMC controller demonstrated superior robustness compared to the PID controller, particularly under abrupt inductive load variations. This enhanced performance is attributed to its ability to adapt rapidly to system changes without depending on the exact mathematical model.

- During the ground fault tests, the SMC-w effectively maintained the overall system stability, mitigated adverse effects, and quickly restored normal operating conditions. This capability underscores its suitability for applications requiring resilience to severe faults, where minimal disruption to the system performance is critical.

- A comparative analysis of the SMC-w and PID controllers highlighted the advantages of the proposed approach. The PID controller required precise tuning and exhibited longer settling times under rapid load variations, and the SMC-w provided faster stabilization and superior steady-state performance with fewer control parameters. The robustness of the SMC also enables it to handle complex disturbances, such as ground faults and input voltage perturbations, with minimal impact on the system output.

- The results showed that the SMC-w maintained stable performance under unbalanced nonlinear loads. Despite the abrupt load change, the voltages remained constant in all three phases at 120 VRMS and 60 Hz, with a voltage error of less than 3%. Although the currents exhibited different magnitudes and waveforms because of the unbalanced and nonlinear nature of the loads, the voltages remained stable. This shows that the system is robust and effective in controlling the voltages. This highlights the capability of the SMC-w to maintain efficient and stable control under complex and dynamic load conditions.

- The SMC-w control strategy not only ensured stability under RL load conditions but also demonstrated outstanding performance under more demanding scenarios. This capability guarantees the applicability of the system in industrial and renewable energy environments, where load conditions are rarely ideal, thereby strengthening the practical relevance of the proposed approach. The controller design, which requires only a reduced number of parameters and is oriented toward current digital technologies, is easily implementable in microprocessors or DSPs of any architecture. This reduces implementation complexity, minimizes hardware costs, and accelerates the transfer of the system from the simulation environment to practical industrial applications.

- The Lyapunov-based analysis confirmed that the SMC–washout filter combination guarantees asymptotic stability of the controlled inverter, ensuring convergence of the sliding surface and robustness under disturbances.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

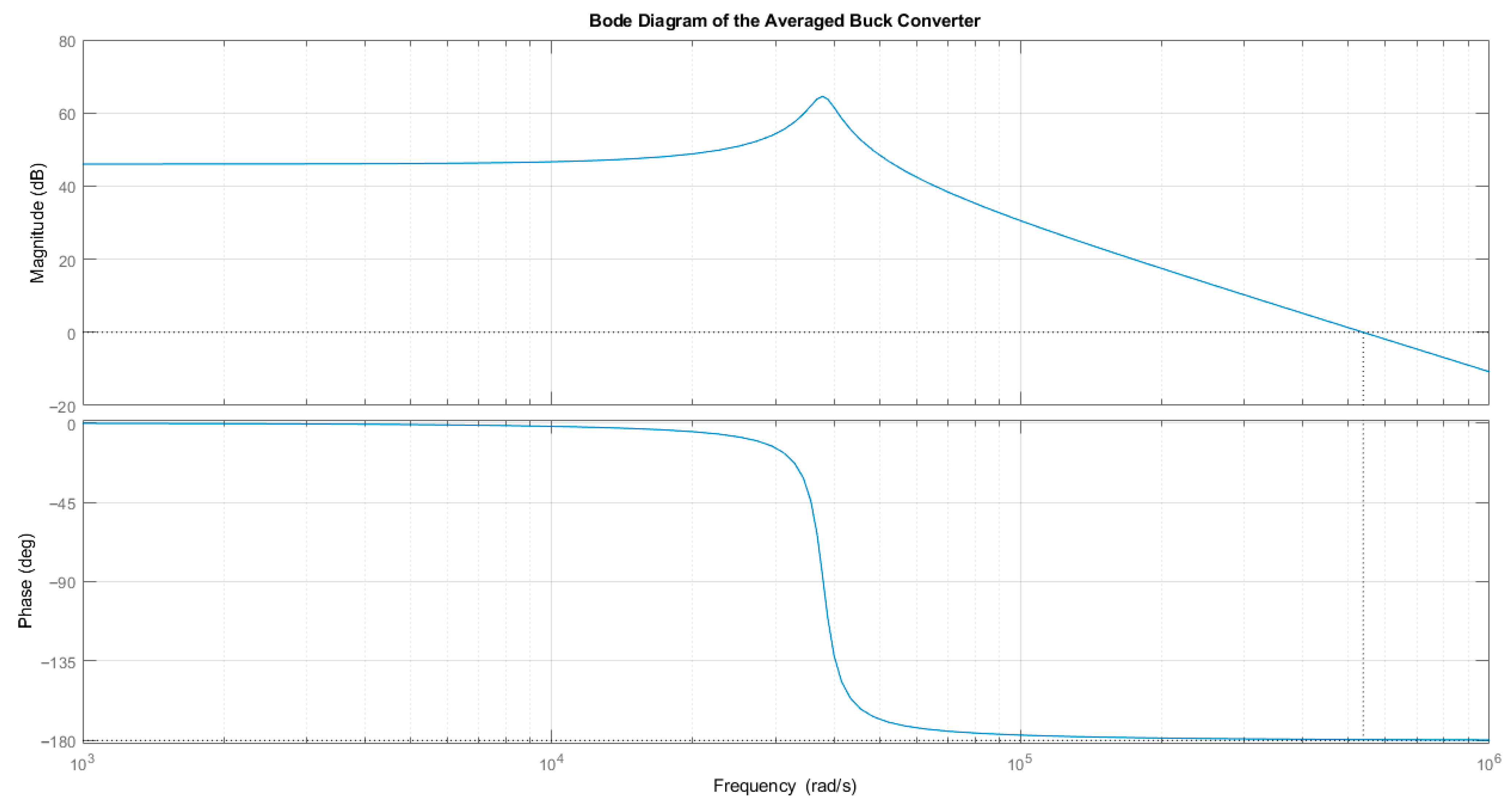

Appendix A. Frequency-Domain Analysis of the Averaged Buck Converter

- Discussion

Appendix B. Stability Analysis of the Closed Loop System

Appendix C. Chattering and Subharmonic Mitigation Analysis of the Proposed SMC–w

- (a,b) Sliding surface : The conventional SMC shows oscillations exceeding ±30 V, while the SMC–w limits them to within ±4 V, indicating a strong damping of high-frequency chatter.

- (c,d) Duty-cycle : The conventional SMC displays irregular and dense switching; the SMC–w generates a faster yet smoother PWM pattern, confirming stable modulation and precise control action.

- (e,f) Output phase voltages : The conventional SMC outputs contain subharmonic and low-frequency components that distort the waveform, while the SMC–w delivers nearly sinusoidal voltages with greatly reduced ripple and harmonic distortion.

References

- Usman, H.M.; Mahmud, M.; Saminu, S.; Ibrahim, S. Harmonic mitigation in inverter circuits through innovative LC filter design using PSIM. J. Ilm. Tek. Elektro Komput. Inform. 2024, 10, 138–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousefpoor, N.; Fathi, S.H.; Farokhnia, N.; Abyaneh, H.A. THD minimization applied directly on the line-to-line voltage of multilevel inverters. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2012, 59, 373–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, G.; Mohamed, F.; Nosier, M. Power quality improvement of sugar factories dc motor drive using hybrid filter. Egypt. Sugar J. 2019, 12, 112–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plakhtii, O.; Nerubatskyi, V.; Sushko, D.; Hordiienko, D.; Khoruzhevskyi, H. Improving the harmonic composition of output voltage in multilevel inverters under an optimum mode of amplitude modulation. East.-Eur. J. Enterp. Technol. 2020, 2, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usha, S.; Subramani, C.; Geetha, A. Performance analysis of H-bridge and T-bridge multilevel inverters for harmonics reduction. Int. J. Power Electron. Drive Syst. (IJPEDS) 2018, 9, 231–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseinpour, M.; Dejamkhooy, A. Control and power sharing among parallel three-phase three-wire and three-phase four-wire inverters in the presence of unbalanced and harmonic loads. IEEJ Trans. Electr. Electron. Eng. 2018, 13, 1027–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, M.; Kang, Y. PID controller design for UPS three-phase inverters considering magnetic coupling. Energies 2014, 7, 8036–8055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz-Rodriguez, I.D.; Oliveira, V.A.; Bhattacharyya, S.P. Modern design of classical controllers: Digital PID controllers. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE 24th International Symposium on Industrial Electronics (ISIE), Buzios, Brazil, 3–5 June 2015; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahfoud, S.; Derouich, A.; Ouanjli, N.E.L.; Mahfoud, M.E.L.; Taoussi, M. A new strategy-based PID controller optimized by Genetic Algorithm for DTC of the Doubly Fed Induction Motor. Systems 2021, 9, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Li, B.; Zhang, Y.; Jiang, Q.; Liu, T. The LCC type DC grids forming method and fault ride-through strategy based on fault current limiters. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2025, 170, 110843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdolrasol, M.G.M.; Hannan, M.A.; Hussain, S.M.S.; Ustun, T.S. Optimal PI controller based PSO optimization for PV inverter using SPWM techniques. Energy Rep. 2022, 8, 1003–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Liang, Z.; Li, W.; Wang, X. Harmonic suppression strategy in single-phase SPWM based on mixed integer nonlinear programming. Mod. Appl. Sci. 2019, 13, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristi, A.A.; Susanto, B.; Risdiyanto, A.; Junaedi, A.; Muqorobin, A.; Rachman, N.A.; Santosa, H.P. Selection method of modulation index and frequency ratio for getting the SPWM minimum harmonic of single phase inverter. EMIT. Int. J. Eng. Technol. 2021, 9, 75–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.J. Analysis and suppression strategy of harmonics for SPWM inverter. Adv. Mat. Res. 2012, 588–589, 454–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; Yang, J.; Zeng, F. Three-phase current reconstruction for PMSM drive with modified twelve sector space vector pulse width modulation. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2022, 37, 15209–15220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meraj, S.T.; Yahaya, N.Z.; Hasan, K.; Lipu, M.S.H.; Masaoud, A.; Ali, S.H.M.; Hussain, A.; Othman, M.M.; Mumtaz, F. Three-phase six-level multilevel voltage source inverter: Modeling and experimental validation. Micromachines 2021, 12, 1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittal, A.; Janardhan, K.; Ojha, A. Multilevel inverter based Grid Connected Solar Photovoltaic System with Power Flow Control. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference on Sustainable Energy and Future Electric Transportation (SEFET), Hyderabad, India, 21–23 January 2021; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bimazlim, M.A.S.B.; Ismail, B.; Aihsan, M.Z.; Mazalan, S.K.; Walter, M.S.M.A.; Rohani, M.N.K.H. Comparative study of optimization algorithms for SHEPWM five-phase multilevel inverter. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Conference on Power and Energy (PECon), Penang, Malaysia, 7–8 December 2020; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gueye, D.; Ndi, A.; Di, A. Design and implementation of a robust ANN-PID corrector to improve high penetrations photovoltaic solar energy connected to the grid. J. Energy Syst. 2023, 7, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, C.; Zhang, X.; Qie, T.; Chau, T.K.; Ye, J.; Yu, Y.; Iu, H.H.C.; Fernando, T. A novel deep deterministic policy gradient assisted learning-based control algorithm for three-phase DC/AC inverter with an RL load. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Power Electron. 2023, 11, 5529–5539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, A.K.V.K.; Narayana, K.V.L. Optimal total harmonic distortion minimization in multilevel inverter using improved whale optimization algorithm. Int. J. Emerg. Electr. Power Syst. 2020, 21, 20200008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, S.; Xie, K.; Chen, G.; Liu, M.; Wu, Z.-G. Extended dissipative sliding-mode control for discrete-time piecewise nonhomogeneous Markov jump nonlinear systems. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2022, 52, 9219–9229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, C.; Wang, S.; Yu, H. Finite-time sliding mode control based on unknown system dynamics estimator for nonlinear robotic systems. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II Express Briefs. 2023, 70, 2535–2539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haroon, F.; Aamir, M.; Waqar, A. Second-order rotating sliding mode control with composite reaching law for two level single phase voltage source inverters. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 60177–60188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellanos-Cárdenas, D.; Posada, N.L.; Orozco-Duque, A.; Sepúlveda-Cano, L.M.; Castrillón, F.; Camacho, O.E.; Vásquez, R.E. A review on data-driven model-free sliding mode control. Algorithms 2024, 17, 543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, W.; Qiu, J.; Lam, H.-K. Fuzzy-affine-model-based sliding-mode control for discrete-time nonlinear 2-D systems via output feedback. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2023, 53, 979–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.; Li, H.; Wu, W.; Chen, B.; Blaabjerg, F. Model-based discrete sliding mode control with disturbance observer for three-phase LCL-filtered grid-connected inverters. IEEJ Trans. Electr. Electron. Eng. 2020, 15, 1520–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alattas, K.A.; Vu, M.T.; Mofid, O.; El-Sousy, F.F.M.; Alanazi, A.K.; Awrejcewicz, J.; Mobayen, S. Adaptive nonsingular terminal sliding mode control for performance improvement of perturbed nonlinear systems. Mathematics 2022, 10, 1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anjum, W.; Husain, A.R.; Aziz, J.A.; Abbasi, M.A.; Alqaraghuli, H. Continuous dynamic sliding mode control strategy of PWM based voltage source inverter under load variations. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0228636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monsalve-Rueda, M.; Candelo-Becerra, J.E.; Hoyos, F.E. Second-order sliding-mode control applied to microgrids: DC & AC buck converters powering constant power loads. Energies 2024, 17, 2701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pichan, M.; Rastegar, H. Sliding-mode control of four-leg inverter with fixed switching frequency for uninterruptible power supply applications. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2017, 64, 6805–6814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Liu, J.; Vazquez, S.; Mazumder, S.K. Sliding mode control in power converters and drives: A review. IEEE/CAA J. Autom. Sin. 2022, 9, 392–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Wang, D.; Li, Z. Design of optimal sliding mode control system for PMLSM. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2024, 2918, 012015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Feng, Y.; Man, Z. Terminal sliding mode control—An overview. IEEE Open J. Ind. Electron. Soc. 2021, 2, 36–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grgić, I.; Bašić, M.; Vukadinović, D.; Marinović, I. Novel space-vector PWM schemes for enhancing efficiency and decoupled control in quasi-Z-source inverters. Energies 2024, 17, 1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, M.; Man, C.; Zhou, T. Mid-point potential balancing in three-level inverters. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2023, 2479, 012023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhou, H. High performance of three-level T-type grid-connected photovoltaic inverter system with three-level boost maximum power point tracking converter. Adv. Mech. Eng. 2019, 11, 168781401984336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masoudian, A.; Farjah, E. Nine-switch three-level z-source inverter. In Proceedings of the 4th Annual International Power Electronics, Drive Systems and Technologies Conference, Tehran, Iran, 13–14 February 2013; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wang, W. Global fast terminal sliding mode control for wind energy conversion system. Adv. Mat. Res. 2012, 463–464, 1616–1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, T.D.; Kang, H.-J.; Suh, Y.-S. Chattering-free neuro-sliding mode control of 2-DOF planar parallel manipulators. Int. J. Adv. Robot. Syst. 2013, 10, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Fei, J. Dynamic sliding mode control of active power filter with integral switching gain. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 21635–21644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monsalve-Rueda, M.; Candelo-Becerra, J.; Hoyos, F.E. Dynamic behavior of a sliding-mode control based on a washout filter with constant impedance and nonlinear constant power loads. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 4548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velasco-Muñoz, H.; Candelo-Becerra, J.E.; Hoyos, F.E.; Rincón, A. Speed regulation of a permanent magnet DC motor with sliding mode control based on washout filter. Symmetry 2022, 14, 728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inayat, I.; Amin, R.U.; Ali, M.M. Hardware-in-the-loop flight motion simulation of flexible variable sweep aircraft. Aircr. Eng. Aerosp. Technol. 2018, 90, 1428–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Gao, X.; Sun, L.; Zheng, D.; Shi, H.; Lei, C.; Hu, L.; Zong, Y. The adaptive neural network fuzzy sliding mode control for the 3-RRS parallel manipulator. Adv. Mech. Eng. 2022, 14, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.Y.; Tseng, C.L.; Lin, S.C.; Chou, J.H.; Chang, Y.S.; Sung, W.T. Hybrid fuzzy-sliding control with fuzzy self-tuning for vector controlled drive systems. Appl. Mech. Mater. 2013, 418, 96–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagano, D.J.; Ponce, E. On the robustness of the DC-DC boost converter under washout SMC. In Proceedings of the 2009 Brazilian Power Electronics Conference, Bonito, MS, Brazil, 27 September–1 October 2009; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahim, A.P.N.; Pagano, D.J.; Heldwein, M.L.; Ponce, E. Control of interconnected power electronic converters in dc distribution systems. In Proceedings of the XI Brazilian Power Electronics Conference, Natal, Brazil, 11–15 September 2011; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponce, E.; Pagano, D.J. Sliding dynamics bifurcations in the control of boost converters. IFAC Proc. 2011, 44, 13293–13298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velasco, F.E.H.; García, N.T.; Gómez, Y.A.G. Numerical and experimental comparison of the control techniques quasi-sliding, sliding and PID, in a DC-DC buck converter. Sci. Tech. 2018, 23, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trujillo, O.A.; Toro-García, N.; Hoyos, F.E. PID controller using rapid control prototyping techniques. Int. J. Electr. Comput. Eng. (IJECE) 2019, 9, 1645–1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velasco, F.E.H.; García, N.T.; Gómez, Y.A.G. Adaptive control for buck power converter using Fixed Point Inducting Control and Zero Average Dynamics strategies. Int. J. Bifurcat. Chaos 2015, 25, 1550049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Description | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Fc | Commutation frequency | 40 kHz |

| E | Input voltage | 400 VDC |

| Inductor current phase A | Variable (A) | |

| Inductor current phase B | Variable (A) | |

| Inductor current phase C | Variable (A) | |

| Voltage output phase A | Variable (V) | |

| Voltage output phase B | Variable (V) | |

| Voltage output phase C | Variable (V) | |

| Reference voltage phase A | Variable (V) | |

| Reference voltage phase B | Variable (V) | |

| Reference voltage phase C | Variable (V) | |

| Inductance of each phase | 62.5 (H) | |

| Capacitance of each phase | 11.11 (F) | |

| Resistance of each phase | ||

| Control signals for switches | 0 or 1 | |

| Complementary control signals | 1 or 0 | |

| Cut-off frequency for a high-pass filter | 26,563 | |

| Control parameter | 0.1, 1 or 4 |

| No. Event | Perturbation | From | To | Time [s] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Load change | R = 20 ohm | R = 5 ohm | 0.0225 |

| 2 | Frequency change | f = 60 Hz | f = 180 hz | 0.015 |

| 3 | Voltage amplitude change | 120 Vrms | 60 Vrms | 0.015 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hoyos, F.E.; Candelo-Becerra, J.E.; Rincón, A. Enhanced Three-Phase Inverter Control: Robust Sliding Mode Control with Washout Filter for Low Harmonics. Energies 2025, 18, 5889. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18225889

Hoyos FE, Candelo-Becerra JE, Rincón A. Enhanced Three-Phase Inverter Control: Robust Sliding Mode Control with Washout Filter for Low Harmonics. Energies. 2025; 18(22):5889. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18225889

Chicago/Turabian StyleHoyos, Fredy E., John E. Candelo-Becerra, and Alejandro Rincón. 2025. "Enhanced Three-Phase Inverter Control: Robust Sliding Mode Control with Washout Filter for Low Harmonics" Energies 18, no. 22: 5889. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18225889

APA StyleHoyos, F. E., Candelo-Becerra, J. E., & Rincón, A. (2025). Enhanced Three-Phase Inverter Control: Robust Sliding Mode Control with Washout Filter for Low Harmonics. Energies, 18(22), 5889. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18225889