Abstract

Biomass has long been a major source of energy for residential heating and, in recent decades, has regained attention as a renewable alternative to fossil fuels. This review explores the current state and prospects of domestic biomass-based heating technologies, including biomass-fired boilers, local space heaters, and hybrid systems that integrate biomass with complementary renewable energy sources to deliver heat, electricity, and cooling. The review was conducted to identify key trends, performance data, and innovations in conversion technologies, fuel types, and efficiency enhancement strategies. The analysis highlights that biomass is increasingly recognized as a viable energy carrier for energy-efficient, passive, and nearly zero-energy buildings, particularly in cold climates where heating demand remains high. The analysis of the available studies shows that modern biomass-fired systems can achieve high energy performance while reducing environmental impact through advanced combustion control, optimized heat recovery, and integration with low-temperature heating networks. Overall, the findings demonstrate that biomass-based technologies, when designed and sourced efficiently and sustainably, can play a significant role in decarbonizing the residential heating sector and advancing nearly zero-energy building concepts.

1. Introduction

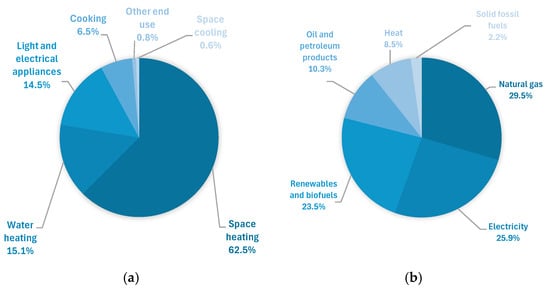

The inhabitants of Earth are facing climate change, which affects them through rising average global temperatures and more frequent extreme weather events. One of the main reasons responsible for the situation is the emission of greenhouse gases and other pollutants into the atmosphere. The European Union (EU) bodies decided to react and established challenging goals for the first half of the 21st century. The target for 2030 was to reduce net greenhouse gas emissions by at least 55% by 2030 compared to 1990 levels [1]. The European Commission proposed an amendment to the EU Climate Law, setting a new 2040 goal: a 90% reduction in net greenhouse gas emissions relative to 1990 levels. The ultimate goal is to achieve climate neutrality by 2050. Such action will lead not only to a less polluted atmosphere and reduced negative climate effects, but also to the diversification of heating systems for citizens and their independence from fossil fuel supplies. Apart from emission reduction, the objectives of the EU Climate Law are to monitor progress on the actions taken and take further action if needed, provide predictability for investors and other economic actors, and ensure that the transition to climate neutrality is irreversible [1]. The assumptions and motives behind the EU legislation are clear; however, the evolving nature of the restrictions and the pace of their implementation can be particularly challenging for end-users and manufacturers of heating systems. In EU countries, the residential sector accounted for 26.2% of final energy consumption [2]. The majority of household energy use was attributed to space heating (62.5%) and domestic hot water preparation (15.1%). Natural gas and electricity were the dominant energy sources, accounting for 29.5% and 25.9% of residential demand, respectively. Renewable energy sources accounted for 23.5%, petroleum products for 10.3%, and derived heat for 8.5%. Solid fossil fuels made up the smallest share, at just 2.2% of the sector’s energy use (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Final energy consumption in the residential sector by usage (a) and fuel (b) in 2023 (adopted from [2]).

When adapting to new regulations and reducing fossil fuel use, the only way forward is to implement systems powered by renewable energy sources (RES), including biomass, solar, wind, geothermal, and combined systems. Since biomass is considered a zero-carbon dioxide-emissions fuel option, it plays a key role in the energy sector’s decarbonization. In the EU, almost a quarter of the final energy consumption in the residential sector in 2023 came from renewables and biofuels [2]. In less developed countries, the importance of biomass is even greater. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), over three billion people in developing countries use solid biomass for cooking and heating [3]. In 2020, over 11 million households in the U.S. (almost 9%) used wood as a fuel, mostly for heating [4].

The term “biomass” is broad and encompasses a wide range of fuels. Biomass is produced by plants and animals as organic matter. Vassilev et al. [5] divided biomass into six main groups:

- Wood and woody biomass;

- Herbaceous and agricultural biomass;

- Aquatic biomass;

- Animal and human biomass wastes;

- Contaminated biomass and industrial biomass wastes (semi-biomass);

- Biomass mixtures.

The primary biomass sources include agricultural and forestry residues, animal residues, sewage, algae, and aquatic crops [6]. Among the biomass fuels used in residential applications, the most common are wood logs, pellets (and briquettes), wood chips, straw, husks, and shells, as shown in Figure 2. The decisive factor in choosing fuel is price and availability, as well as ease of storage and preparation.

Figure 2.

Typical biomass fuels used in residential applications: (a) wood logs, (b) pellets, (c) wood chips, (d) straw, (e) shells, and (f) husks. Source: Author’s own elaboration, created in Canva (based on materials provided under the Canva License Agreement).

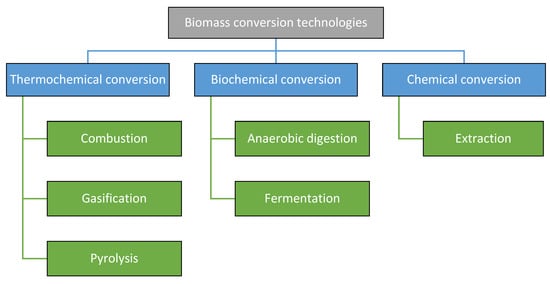

Biomass can be converted into energy, fuels, and chemicals through several thermochemical processes, notably combustion, pyrolysis, and gasification (see Figure 3). Combustion involves the complete oxidation of biomass in the presence of excess oxygen, producing heat, carbon dioxide, and water, making it an ideal process for direct energy generation. In contrast, pyrolysis is the thermal decomposition of biomass in the absence of oxygen, yielding a mixture of solid char, liquid bio-oil, and gaseous products. This method is versatile and supports bio-refinery applications, depending on whether slow or fast pyrolysis is employed. Gasification operates under limited oxygen conditions at high temperatures to convert biomass into syngas—a mixture of carbon monoxide, hydrogen, and methane—which can be used for electricity generation, heat production, or as a precursor for chemical synthesis [7].

Figure 3.

Biomass conversion technologies (adopted from [8]).

The Global Bioenergy Statistics Report (11th edition) [9] noted that in 2022, renewable energy sources, including biofuels, accounted for 14.3% of the global energy supply. In 2021, bioenergy contributed 96% of renewable heat, mostly in Europe (80%). The global domestic supply of biomass reached almost 54 EJ [GBS], and the IRENA report [10] predicts that by 2030, the global total biomass supply in primary energy terms will range from 97 to 147 EJ/year, primarily from agricultural residues and wastes. The supply potential of forest products, including forestry residues, is 27–43 EJ/year. From the EUBIA (European Biomass Industry Association) report: the technical potential for the EU-27 is estimated at around 200 Mtoe/year (i.e., ~8.4 EJ/year) in the short term (2020), with the possibility of doubling this to 400 Mtoe/year (~16.8 EJ/year) by 2050 [11]. Biomass is a fuel available in almost every inhabited region of the world. Due to its high moisture content (when harvested fresh) and relatively low calorific value, it is used locally, thereby ensuring energy security and independence from other energy carriers.

This review summarizes the current state of the art in biomass technologies used for residential heating. It presents the developed technologies and new directions for development, including mixed systems that combine traditional biomass use with other energy systems to produce not only heat but also electricity, cooling, and desalinated water. In this context, biomass can also be considered a part of energy-saving, passive, and nearly zero-energy buildings (NZEBs), especially in cold regions. NZEBs are defined as buildings with very high energy performance whose nearly zero or very low remaining energy demand is covered to a very significant extent by on-site or nearby renewables [12]. They represent a key strategy for mitigating the environmental footprint of the built environment. To support their development, building optimization has emerged as a powerful tool for evaluating design alternatives and identifying configurations that achieve zero-energy performance. This approach involves formulating and minimizing objective functions that encompass energy metrics (e.g., thermal demand, renewable energy yield, and efficiency gains), environmental indicators (e.g., CO2 emissions), and economic criteria (e.g., life-cycle cost, net present value, and capital investment) [13]. Consequently, NZEBs integrate advanced energy-efficient systems—including HVAC, lighting, and appliances—alongside renewable energy technologies to meet their operational demands sustainably. Given the high share of heating in final energy consumption in buildings, integrating biomass-fired sources into NZEBs is a promising option for meeting building energy demands with minimal environmental impact. Biomass, as a controllable and carbon-neutral energy source, serves as an effective complement to variable renewables, such as solar and wind—especially in regions with pronounced seasonal fluctuations and during periods of high thermal demand. To enhance operational flexibility and overall system efficiency, biomass is increasingly being integrated into hybrid configurations that primarily combine solar thermal collectors, electric heat pumps, and thermal energy storage (TES). Against this backdrop, the present article is original in relation to the extant literature, offering a new approach to the issues surrounding nearly zero-energy buildings.

2. Methodology

This review aims to provide a comprehensive examination of the current state of research on biomass-fired heating systems, technological progress, and the potential for their integration into nearly zero-energy buildings through combining them with other systems. To ensure credibility and clarity, a systematic approach was adopted to select and analyze the literature. The review was organized into three stages: gathering and retrieving the literature, analyzing its content, and discussing domain knowledge.

2.1. Criteria Applied to Ensure the Credibility and Clarity of the Review

The literature was collected from leading academic databases, including Scopus, Web of Science, ScienceDirect, IEEE Xplore, and EBSCO, and was further supplemented with information from carefully selected, topic-relevant websites. The following criteria were applied to refine the literature selection:

- Peer-reviewed sources (journal articles and conference proceedings) were preferred—116 (92.1% of all references);

- Studies published within the last ten years were primarily considered, including 107 Articles: 77 from 2020 to 2025 and 30 from 2015 to 2019;

- Articles from well-established publishers were mainly cited, including Elsevier, MDPI, IEEE, Wiley, Springer Nature, Frontiers, and IOPscience.

2.2. The Main Stages of the Literature Review Process

The review spans a broad temporal scope, with an emphasis on recent publications to accurately reflect the current state of the art. A limited number of earlier studies were also included to provide essential historical and conceptual context. The literature review process was conducted in several stages:

- Initial screening—titles and abstracts were reviewed to assess the relevance of each work to the research topic;

- Evaluation—full-text articles were analyzed to identify significant scientific and technical contributions, methodologies, and findings;

- Classification and usage—key insights were categorized into thematic groups and integrated into the corresponding sections of the review.

2.3. Keyword Selection

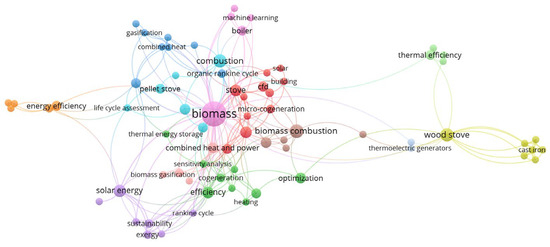

To conduct a comprehensive literature search across the selected databases, a set of keywords and their combinations was formulated using Boolean operators (“AND”, “OR”) to ensure precision and coverage. The selected terms included the following: residential heating, biomass, biofuel, pellet, wood, straw, biomass combustion, biomass-fired boilers, pellet boilers, wood boilers, wood chip boilers, logwood gasification boilers, straw-fired boilers, local space heaters, wood stove, biomass hybrid systems, emission reduction, combustion optimization, automation, control systems, CFD modelling, micro-CHP, cogeneration, thermoelectric generators, TEG, Stirling engines, NZEB, nearly zero-energy buildings, renewable energy integration, solar–biomass hybrid systems, heat pump integration, among others. These terms were combined and refined iteratively to capture a broad yet relevant range of studies related to domestic biomass-based heating technologies, including biomass-fired boilers, local space heaters, and hybrid systems that integrate biomass with complementary renewable energy sources to deliver heat, electricity, and cooling. Furthermore, Figure 4 shows the co-occurrence visualization created from keywords identified in the cited references. Based on occurrence, the keywords with the highest weight are as follows: biomass, biomass combustion, and wood stove.

Figure 4.

Keyword co-occurrence visualization (map generated in VOSviewer 1.6.20).

2.4. Limitations of the Review

The following limitations were identified during the literature collection and review process:

- Language bias—the review focuses exclusively on publications written in English and may therefore omit relevant studies published in other languages;

- Source scope—mainly peer-reviewed scientific papers were included, potentially excluding valuable insights from technical reports and other non-academic sources;

- Search methodology—reliance on keyword-based searches may have unintentionally excluded certain relevant studies due to variations in terminology and indexing practices.

3. Biomass-Fired Heating Systems—State of the Art

Biomass-fired heating systems are the oldest and most common technologies in use. However, new solutions and applications emerge in industry and the literature every year. Biomass is considered CO2-neutral and readily available, making it an attractive and important source of heat. Wood and other woody biomass were burned in ineffective stoves, fireplaces, and kitchens for many years. In most cases, the heat was transferred directly via infrared radiation and convection. According to Garrison [14], the first central-heating systems appeared in Germany in the 1870s. The majority of appliances used at present can be divided into boilers and local space heaters (including stoves and fireplaces). Because the first group of heating systems are located in the utility room, they also serve an aesthetic function. The second group can be characterized by higher efficiency and fewer emissions, as the combustion process can be easily controlled and automated when pellets and wood chips are used. Boilers transfer heat only to the water, while local space heaters can employ different methods of heat transfer, including water heat exchangers. Today, these systems are being developed and are becoming increasingly effective and emitting less pollution.

3.1. Pellet Boilers

Pellets are made of compressed solid biomass, usually in the form of small cylindrical rods with a diameter of 6 mm. Such a structure enables effective and stable transport (with a retort feeder or a gutter feeder) and provides good control of the combustion process. The moisture and ash contents are low, and the pellets meet the required standards. Their repeatable shape and composition make supply and operation easier. The primary disadvantage of using pellets as a fuel source is the associated cost of biomass milling, compression, packaging, and other related processes.

Pellet boilers are biomass heating systems that use wood pellets as a renewable fuel, offering a sustainable alternative to fossil-fuel boilers in residential, commercial, and district heating applications. The technology has undergone significant development in recent decades, driven by concerns over energy security, climate policies, and the push toward low-carbon heating solutions [15]. At present, automatic pellet boilers are gaining popularity among homeowners of detached homes, thanks to their straightforward design and ease of use. These systems typically feature a pellet storage tank and a heat exchanger equipped with a burner, linked together by a fuel delivery mechanism. The most common type of feeder is the screw feeder, which transports pellets into the combustion chamber using a rotating spiral. An alternative is the piston feeder, which delivers a fixed quantity of fuel with each stroke. Piston feeders offer greater versatility, as they can accommodate a wider range of fuel types—including pellets, granular coal, shredded straw, and wood chips [16]. An example of a pellet-fired boiler is shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

An example of the pellet boiler tested at the Centre of Sustainable Development and Energy Saving AGH WGGiOŚ “Miękinia” [17].

Pellet boilers, among the cleanest solid-fuel heating systems, produce the lowest levels of air pollutants among boiler types. Nevertheless, the complete elimination of harmful substances in flue gases remains unattainable. Most pellet boilers currently available fall into the fifth class—the highest category—under the PN-EN 303-5:2012 standard [18]. For a 20 kW unit in this class, the minimum required efficiency is 88%. According to PN-EN 303-5:2012, the maximum permissible emissions for automatic biomass boilers are as follows (adjusted to 10% oxygen concentration in flue gas): carbon monoxide (CO) at 500 mg/m3, organic gaseous carbon (OGC) at 20 mg/m3, and particulate matter at 40 mg/m3. These boilers also comply with the Ecodesign directive and are rated A+ for energy efficiency under Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) No 811/2013. In terms of nominal heating capacity, pellet boilers achieve efficiencies exceeding 90% [16,17].

Considering their functional advantages, pellet boilers are increasingly used in hybrid systems (e.g., combined with solar thermal collectors or heat pumps) and in district heating networks. In the context of Positive Energy Districts (PEDs), pellet boilers can complement heat pumps and other renewable energy sources, such as wind and solar, by providing dispatchable thermal energy.

3.2. Wood Chip Boilers

Wood chips differ significantly from pellets because of their irregular shape and size, and their variable moisture, ash, and heating value contents. These features also pose challenges for the fuel supply mechanism and combustion process control, resulting in higher emissions (especially particulate matter, or PM) and lower efficiency. Despite this, automatic fuel feeding is still possible due to their small size and fragmentation. Wood chips are significantly cheaper than pellets and more easily accessible, as they can be produced independently.

Wood chip boilers are a mature form of biomass combustion technology that are widely applied in district heating systems, public buildings, and industrial facilities, particularly across Europe and North America. Unlike pellet boilers, which rely on standardized, densified fuel, wood chip boilers use locally sourced, less-processed biomass, often originating from forestry residues, thinning operations, or sawmill by-products. Modern wood chip boilers employ moving grate or stoker combustion systems, combined with multi-stage air injection and flue gas cleaning technologies (e.g., cyclones, electrostatic precipitators). Efficiency typically ranges between 85% and 94%, but emissions remain highly dependent on fuel properties and operational settings [19,20]. Therefore, emissions control remains a central challenge. Rector et al. [21] found particulate emissions from a chip boiler to be significantly higher those from an oil boiler, while Trojanowski et al. [22] demonstrated that pre-treating chips via hot water extraction reduced particulate emissions considerably. These findings have underscored the importance of fuel preparation, automation, and emissions control systems in enhancing environmental performance. An example of a 50 kW boiler and fuel storage used by Tucki et al. [23] for the combustion of wood chips is shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

An example of a 50 kW boiler and a fuel storage with a mixer, filled with pine chips [23].

3.3. Logwood Gasification Boilers

Logwood fuel refers to natural firewood logs that are cut, split, and seasoned. It is one of the oldest and most traditional heating fuels, valued for its wide availability and ability to produce a steady, high heat output when properly prepared. Hardwoods such as oak, ash, and beech are generally preferred due to their higher energy density and cleaner combustion. The quality of logwood fuel depends heavily on its moisture content. Freshly cut wood must be dried for one to two years until it reaches a moisture content of approximately 20% or less. Well-seasoned logs burn more efficiently, release more heat, and produce less smoke and creosote buildup in chimneys.

Logwood gasification boilers are biomass combustion systems designed to convert solid wood logs into combustible gas (syngas) before final combustion. This process enhances efficiency and reduces emissions compared to conventional basic wood boilers. Gasification involves the partial oxidation of wood at high temperatures, generating gases such as CO, H2, and CH4, which are then combusted in a secondary combustion zone. These systems typically employ a two-stage combustion process: a gasification stage (pyrolysis and partial oxidation) that produces combustible gases and a combustion stage where these gases are burned with excess air to achieve complete oxidation. This configuration enables the more complete combustion of volatile components released from the wood, thereby significantly reducing unburned volatile emissions and particulate matter. As a result, logwood gasifiers emit lower levels of volatile organic compounds (VOCs), carbon monoxide (CO), and particulates compared to simple wood boilers—especially under optimal operating conditions. Real-world emissions studies of modern biomass boilers have shown that newer designs produce lower levels of CO, organic gases, and total suspended particles than older units [24]. In well-engineered systems, thermal efficiencies can be significantly higher than those of basic wood boilers. However, actual performance depends strongly on wood moisture, load conditions, and the sophistication of the control systems [25]. An example of a 23 kW logwood gasification boiler used in the tests described by Valicek et al. [25] is shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

An example of a boiler for the gasification of wood pieces with a nominal heat output of 23 kW, used in tests conducted by Valicek et al. [25].

3.4. Straw Boilers

Straw, the residual stalks of cereal crops (e.g., wheat, barley, rice, oat), is an abundant agricultural biomass resource, especially in agricultural regions. As a low-cost, regionally available fuel, straw has been explored as a feedstock for boilers and combustion systems aiming to provide heat or combined heat and power. However, its combustion presents distinct challenges due to its high ash, alkali, silica, and chlorine contents, as well as its low bulk density. Although environmental aspects are considered, the high ash content poses a significant risk of deposits and corrosion in the boiler and ducts. Straw ash has a low softening temperature, and it is crucial not to exceed this temperature during operation.

Straw-fired boilers currently available on the market include several types: batch boilers designed for the periodic, cyclic combustion of baled straw; systems that utilize ground straw combustion through the “burning cigar” method for continuous operation; and automatic units capable of burning chopped straw into 5–10 cm pieces, also operating continuously. The typical power output of batch straw-fired boilers ranges from 40 to 700 kW, making them well-suited for generating low-temperature heat for space heating and domestic hot water systems, as well as for specialized settings such as greenhouses, drying facilities, and distilleries. In such cases, beyond conventional heating boilers, oil-fired air heaters are also commonly employed, using thermal oil as the working medium, heated to 150–200 °C [26]. An example of a 100 kW straw-fired cogeneration boiler is shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

An example of a 100 kW straw boiler adapted to an experimental CHP system [27].

3.5. Local Space Heaters

Local space heaters, i.e., stoves and fireplaces, are the most popular home heating appliances, as most of them do not require electricity and their operation is entirely user-dependent. By acquiring inexpensive fuel, users become completely independent of external energy sources, bringing them closer to the original use of fire. Local space heaters hearths can be divided into those with and without a grate. Hearth grates are typically used in fireplaces and freestanding stoves (and boilers), and allow for continuous ash removal but result in lower combustion temperatures and, consequently, lower efficiency. Fuel loads in fireplaces are frequent, occurring approximately once per hour, and are small, ranging from 1 to 3 kg. In grateless hearths found in heat-storage stoves and traditional tiled stoves, the combustion temperature is significantly higher, and the accumulative mass of the appliance allows for heat storage, significantly increasing efficiency. Wood loads are large, typically 5–20 kg, and infrequent, occurring once to three times per day. An example of wood stoves with a heating power of up to 20 kW, used in studies conducted by Motyl et al. [28], is shown in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

An example of wood stoves with a heating power of up to 20 kW, used in studies conducted by Motyl et al. [28].

3.6. Summary of the Available Biomass-Fired Appliances and Future Perspectives

The biomass-fired appliances discussed are widely deployed and contribute significantly to energy security and independence. A general comparison of pellet boilers, gasification boilers, wood chip boilers, straw boilers, and local space heaters is presented in Table 1. However, to enhance the efficiency and environmental performance of biomass utilization, further technological advancements are essential, particularly those aimed at reducing air pollution and minimizing fuel waste. Reducing air pollution is critical to meet the emission requirements in Table 2. In this context, Section 4 explores several strategies to improve the biomass-fired appliances, including the optimization of combustion chamber geometry, refinement of combustion process control, implementation of technologies to reduce solid and gaseous emissions, and integration of combined heat and power (CHP) solutions. Section 5 shifts focus to the incorporation of biomass technologies within nearly zero-energy buildings, emphasizing synergies with heat pumps and solar thermal systems. These integrated approaches enable more effective energy use in residential applications.

Table 1.

General summary of the available biomass-fired appliances.

Table 2.

Emission requirements for biomass-fired appliances.

4. Technological Advances in Biomass-Fired Heating Systems

To meet stringent EU regulations and evolving societal expectations, biomass-based heating systems must become increasingly safe for both human health and the environment, while also offering greater versatility and user convenience. This presents a significant challenge for manufacturers and researchers. Due to its heterogeneous structure and composition, biomass fuel tends to emit relatively high levels of solid and gaseous pollutants, prompting intensive efforts to develop effective technologies for reducing emissions.

A growing trend in the sector is the automation of biomass appliances, which enhances user control while minimizing direct contact with hot surfaces or open flames—an important factor in improving safety and usability. One promising direction in local space heater design is the integration of heat-storing materials. While this concept has historical roots in traditional tiled stoves, modern materials and configurations are being developed to better align with the thermal characteristics of contemporary, well-insulated buildings. Furthermore, biomass heating appliances are increasingly integrated into hybrid energy systems that provide not only space heating, but also electricity generation, cooling, and even water desalination. Biomass appliances demonstrate strong potential in micro-scale cogeneration systems, particularly when combined with thermoelectric generators (TEGs), Stirling engines (SEs), Organic Rankine Cycle (ORC) units, and internal combustion engines (ICEs). On the other hand, in the context of nearly zero-energy buildings, particular attention is given to the combination of biomass-fired appliances with solar thermal systems and heat pumps, which are already widely adopted in the residential sector.

4.1. Emission Reduction Technologies

Pollutants emitted during biomass combustion can be divided into two groups: gaseous and particulate. Gaseous pollutants include CO, NOx, and hydrocarbons (HC), including polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs). Increased CO and HC emissions result from incomplete fuel combustion and poor process organization. Flame cooling, on the other hand, increases PAH levels in flue gases. NOx produced during biomass combustion comprises approximately 90% NO and 10% NO2. The majority of these are fuel nitrogen. NOx produced during the thermal mechanism is negligible due to the low combustion temperature (<1600 °C).

Solid pollutants include inorganic pollutants (such as ash) and organic pollutants (including soot, coke, organic condensates, tar, and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, or PAHs). A short residence time in the combustion chamber is considered the primary cause of organic particle emissions. A distinction is also made between primary particles, formed in the combustion chamber, and secondary particles, produced by gas-phase condensation or atmospheric reactions, such as secondary organic aerosols (SOA). A significant characteristic that distinguishes solid pollutants is their size: PM10 (diameter ≤ 10 µm), PM2.5 (diameter ≤ 2.5 µm), PM1 (diameter ≤ 1 µm), and ultrafine particles (UFP) (diameter ≤ 0.1 µm). The smaller the particles, the deeper they can reach in the human respiratory system.

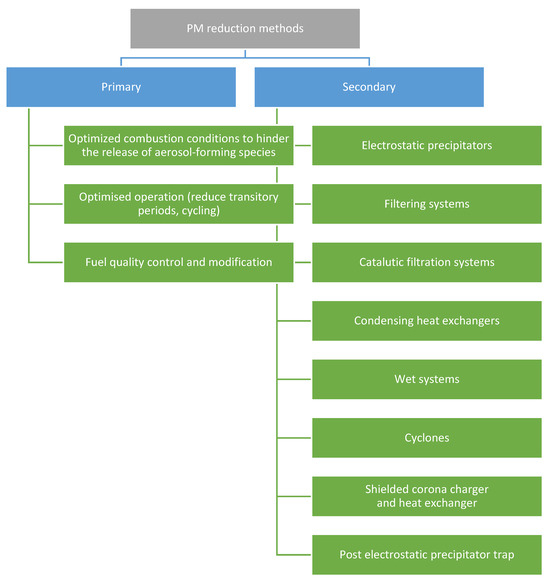

4.1.1. Particle Emission Reduction

An important part of developing biomass technologies for residential heating is considering external factors that influence pollutant emissions, such as filters, collectors, and catalysts. Suhonen et al. [30] designed a high-temperature electric soot collector to reduce particle emissions in a logwood-fired masonry heater. The device was an insulated high-voltage electrode that generates an electric field and is installed in a firebox. Particles with electrical charges were collected on the electrode and oxidized at high temperatures, leading to a reduction in fine particle emissions (of 45% in this case). Moreover, this construction could be implemented in existing appliances. Kantová et al. [31] tested different fuel (pellet) dosage-to-supply/standmill ratios in an automatic pellet boiler. The authors also designed a four-tube precipitator to improve particle separation ability. The dosage system did not significantly affect emissions; however, the precipitator achieved a high collection efficiency of 79–90% across all dosage settings. A novel PM emission reduction system, the passive cyclone abatement system (PCAS), was designed by Coccia et al. [32] for residential pellet stoves. The system could capture PM with quantities exceeding 10 mg/MJ and diameters mostly exceeding 10 μm. The PCAS was considered versatile and could be mounted on other residential heating appliances. Bianchini et al. [33] achieved a particulate matter removal efficiency of 95%. The device applied for this purpose was a bubble-column scrubber integrated with a biomass boiler for residential heating. A similar solution dedicated to a pellet boiler was proposed by Blumberga et al. [33]. The ‘fog unit’ was supposed to capture PM, and water was recirculated. The authors claimed that the PM removal efficiency depends on inlet water temperature, outlet gas temperature, droplet velocity, and droplet holdup. Butcher and Trojanowski [34] proposed a method to reduce particulate emissions from residential wood pellet boilers by adding external thermal storage. Such a solution enabled elongation of the total cycle period of the boiler from 23 to 228 min. This resulted in an efficiency increase from 56% to 74% and a 66% reduction in particulate emissions. A Thermal Energy Storage (TES) tank in combination with a biomass boiler was also studied by Wang et al. [35]. A broad range of boiler nominal outputs and heat demand profiles was investigated, and the authors found a linear correlation between the optimized TES tank volume and the boiler’s nominal capacity. Moreover, it was stated that the average building heat demand is around 45% of the boiler’s nominal capacity. Considering methods for reducing particulate matter emissions, Ozgen et al. [36] discussed various options for pellet boilers. A summary of these methods is provided in Figure 10.

Figure 10.

Division of particulate matter emission reductions from pellet boilers, according to Ozgen [36].

4.1.2. Methods for the Reduction of Gaseous Pollutant Emissions

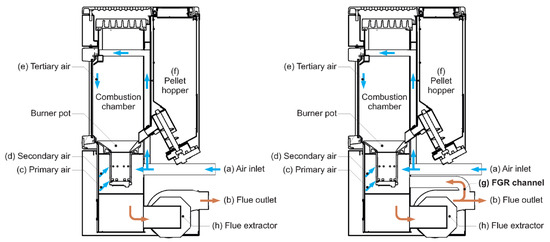

Since reducing air pollutant emissions (especially PM, but also CO and NOx) remains of high interest, the authors develop a broad range of methods to achieve this goal. Many of them focus on dividing the inlet air entering the combustion chamber into primary and secondary air. Different placements and designs of air nozzles are studied. The researchers attempt to divide the entire combustion process into two separate stages: gasification and combustion of the generated gas. Moreover, automatic control of the combustion process and appliance operation is investigated; however, this is not straightforward in batch log combustion, where conditions are less steady than in pellet boilers. Energy storage is a possible way to reduce emissions per unit of energy. More direct solutions are, for instance, flue gas recirculation or dosing the reductive agent. In this context, Lamberg et al. [37] proposed a hybrid slow heat-release stove for residential heating that can burn both wood logs and wood pellets. The work focused on particle and gaseous emissions, reporting 92% reductions in fine particle emissions and 65% reductions in CO emissions from pellets compared to wood logs. Moreover, it was noted that most particle emissions occur at the beginning of the combustion process, whereas CO emissions are observed at its end. An intelligent model to control the combustion process was developed by Loprete et al. [38]. This controlled incoming air to improve stove performance. The system considered stove temperature, weight, and airflow rates to estimate instantaneous efficiency, stoichiometry, and the moisture content of the wood. The control algorithm used these parameters to optimize the air input. Eo et al. [39] improved the thermal efficiency of the wood pellet boiler by optimizing the inlet air flow and quality. To improve contact between fuel and oxygen and increase the reaction rate, a nozzle-type burner pin was designed. The vortex generator was applied to enhance mixing in the combustion chamber and achieve higher temperatures. A system using a LiBr solution for air dehumidification and preheating was developed. When both solutions were applied together, the boiler’s efficiency increased from 73.11% to 78.89%. The inlet air parameters for the wood pellet boiler were also investigated by Zadravec et al. [40]. The authors studied the primary air/secondary air (PA/SA) ratio, infiltration ratio, and global excess air. It was found that, for reducing gaseous emissions, the optimal PA/SA ratio was 0.53, with an O2 concentration of 5.26%. Deng et al. [41] analyzed the relationship between inlet air (primary and secondary) and the performance and pollutant emissions of the biomass stove. The authors created an air supply control system with different parameters set for airflow rate and PA/SA ratios. The results showed that the optimal air supply was 184 L/min, with a PA/SA ratio ranging from 4:6 to 6:4. Furthermore, Polonini et al. [42] tested a flue gas recirculation (FGR) system in a pellet stove to reduce combustion emissions (see Figure 11). The inclusion of that system resulted in 80% lower CO2 emissions, 45% lower PM emissions, and 11% lower NOx emissions. The authors emphasized the FGR system’s ability to reduce emissions, particularly with extreme O2 contents.

Figure 11.

Scheme of the pellet stove without FGR system (left) and scheme of the pellet stove with FGR system (right) [42].

Kardaś et al. [43] tested a two-stage pellet combustion process: first, gasification, and second, oxidation of the gasification products in a boiler. The authors tested different constructions for pellet burners with high- and low-secondary-air nozzles and compared them with a typical retort burner. The version with low-secondary-air nozzles resulted in 74% lower CO emissions compared to the retort burner and 36% lower PM emissions. It was noted that the distance from the secondary nozzles to the gasifying section is crucial for the burner’s operation and its ability to reduce pollutant emissions. Carvalho et al. [44] mounted an external chimney component around the existing chimney of a traditional wood stove for preheating one of two air inlet streams. This division helped increase efficiency and reduce CO. Horvat et al. [45] performed experimental and numerical tests of a biomass domestic boiler using a combustion intensifier (CI) within the conventional combustion system and rotary pellet burner. Two variants of CI were tested: honeycomb-structured ceramic CI and a parallel V-corrugated metal plate CI. The authors noted a 30% reduction in CO emissions in both experimental and simulated tests. Lower dust and NOx emissions, as well as higher efficiency, were also reported. The solution was recognized as suitable for installation in almost every residential heating appliance. A selective non-catalytic reduction mechanism was applied by Ciupek [46]. This work aimed to reduce NOx emissions from a biomass boiler by utilizing an aqueous urea solution. The solution was dosed into the combustion chamber, and a flue gas analysis was performed. The authors observed a 43% decrease in NOx at the highest dosing rate. However, an increase in CO emissions was observed due to process cooling and incomplete oxidation. The optimal dosing conditions were evaluated to minimize PM and NOx emissions simultaneously. Sturmlechner et al. [47] investigated the potential to reduce pollutant emissions through user training. The results are promising, and the desired reduction was observed across all parameters studied, especially BaP. The authors suggest repeating the training in reasonable intervals.

Several solutions for biomass-fired heating in a single-family house were simulated in TRNSYS by Marigo et al. [48]. They considered a gas boiler system with radiators as terminal units, a pellet stove (with and without an air-ducting system), a wood-log stove, and a mix of the above seven configurations. The energy analysis was evaluated based on ideal space heating needs, final energy demand, and primary energy consumption. The authors claimed that biomass stoves, especially wood-burning stoves, are often oversized for the rooms they are located in due to difficulties controlling thermal output. A pellet stove, a gas boiler, and a radiator system provide similar final energy levels, and the wood stove provided an increase of 21% for the electric heater and 9% for the gas boiler. In the case of primary energy, combining the gas heating with wood stoves was similar to a gas boiler system.

On the other hand, Szramowiat-Sala et al. [49] studied emissions from wood combustion in domestic heating units, focusing on PM and gaseous pollutants across three combustion phases: firing, combustion, and post-combustion. Measurements included fuel mass loss, gas concentrations (CO2, CO, O2, SO2), and PM sampling for chemical analysis. The use of an accumulation layer reduced emissions of NO, NOx, and SO2, but increased CO and PM levels. PAH analysis revealed that acenaphthene and benzo[a]pyrene (BaP) were most prevalent, with BaP concentrations peaking during the post-combustion phase. The accumulation layer helped lower BaP emissions during ignition, highlighting its potential for emission control. Ozgen et al. [50] highlighted key factors influencing NOx emissions from biomass combustion in domestic heating. As was discussed, NOx formation was primarily driven by fuel-bound nitrogen (fuel-N), with higher fuel-N content leading to lower conversion efficiency. Non-woody biomass, typically rich in fuel-N, requires effective emission control strategies. However, applying NOx reduction techniques to small-scale systems was challenging due to technical limitations and high costs. Air staging is commonly used, but it may increase CO emissions, requiring careful balancing. Operational parameters, such as air distribution, residence time, and temperature, also play a crucial role in this context; however, small appliances often lack sufficient chamber size for optimal NOx reduction. Compared to fossil fuels, biomass systems emit more NOx and particulate matter, underscoring the need for LCA. In this context, NOx emissions from small wood-burning room heaters were investigated using CFD modeling of a 5 kW natural-draft stove by Bugge et al. [51]. In the analyzed setup, primary air was introduced through bottom slots, secondary air through rear wall openings, and flushing air was directed vertically above the front glass window. Unlike conventional boiler air staging, this configuration allowed for secondary air injection before the complete mixing of fuel gases with primary air. The study demonstrated a notable reduction in NOx emissions at a primary excess air ratio of 0.8, suggesting that staged air combustion can effectively lower NOx emissions, even in compact residential stoves. Another study examined the performance of a lambda-sensor-controlled 15 kW pellet boiler. The authors discussed lambda control as an efficient way to reduce NOx emissions, especially for non-woody biomass fuels, without compromising complete combustion [52]. Vodička et al. [53] presented an experimental study on reducing NOx emissions through staged oxygen injection during the oxy-fuel combustion of lignite and wood pellets in a 30 kW bubbling fluidized bed. By varying the ratio of secondary to primary oxygen while maintaining constant flue gas oxygen levels and bed temperature, the authors achieved up to 50% NOx reduction at ratios of 0.5 for lignite and 1.0 for wood. The staged injection also significantly increased freeboard temperatures, reaching a maximum of 950 °C. The findings confirmed that oxygen staging is an effective strategy for NOx mitigation and may support the use of non-selective catalytic reduction in fluidized bed systems. A summary of the literature positions discussed in this review, focusing on gaseous pollutants and effectiveness improvement, is presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Summary of cited items considering gaseous pollutants and effectiveness improvements.

Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) is a valuable tool that reduces the cost of experimental facilities, tests, and work time. Researchers use this tool for various purposes, including simulating combustion and heat transfer processes in biomass heating appliances. Scharler et al. [54] developed a 3D model of a wood stove, accompanied by a 1D model of a wood log. The authors report a satisfactory reconstruction of wood batch combustion, including CO emissions, O2 content in the flue gas, and chimney temperatures. Szubel et al. [55] demonstrated a validated CFD model for optimizing straw-fired batch boilers. The developed model successfully identified repeatable combustion stages, enabling the observation of phenomena that are difficult to measure directly, such as the dynamics of straw gasification. It revealed that primary air distribution has a strong impact on the heterogeneous burnout rate of straw. In contrast, secondary air injection plays a crucial role in shaping combustion dynamics and must be considered in chamber design and control algorithms. Among the tested configurations, the variant with centrally positioned secondary air inlets proved the most effective, reducing stack losses by up to 33% compared to other configurations. In this case, incomplete combustion losses were reduced experimentally by 43% and in simulations by 18.2% compared to the worst-performing variant, while thermal efficiency improved by 45.7%. These improvements also enabled a reduction in blower fan power, resulting in lower energy consumption and reduced emissions. Furthermore, Bianco et al. [56] employed CFD analysis to design an air manifold for a biomass-fired batch boiler, thereby improving combustion. The proposed solutions were based on minimizing the entropy generation rate by rounding manifold corners. Design improvements have enhanced air velocity distribution, resulting in more uniform conditions within the combustion chamber. Chen et al. [57] and Luo et al. [58] investigated soot formation in wood stoves. The papers noted that the quantity of soot depends on the number of logs and the distance between them, as well as on the air inlet parameters and the construction. Zlateva et al. [59] investigated the combustion of mixed biomass pellets in a domestic boiler, combining experimental flue gas measurements with CFD simulations. The simulations provided insights into temperature distribution, flue gas flow, and turbulence behavior within the combustion chamber. A key focus was the influence of primary-to-secondary air ratios on combustion quality, emissions, and thermal performance. Optimizing air distribution proved effective in improving combustion and reducing pollutant emissions. Findings showed that a 60/40 air distribution ratio enhances combustion efficiency and significantly reduces emissions—CO by 12% and NOx by 27%. The results underscored the viability of mixed biomass pellets as a sustainable fuel alternative, contingent on the precise control of combustion parameters.

4.2. Combustion and Control Advances

Conventional biomass appliances typically rely on manual operation, with the operator’s experience guiding adjustments. This method is labor-intensive and often results in inefficient resource use. To address the specific operational dynamics of biomass appliances, various attempts have been made to develop efficient control strategies for different types of biomass-fired units. In addition to control strategies, various measures are being implemented to enhance the efficiency and environmental performance of boilers and local space heaters. These include the use of thermal storage systems and integration with broader building infrastructure.

4.2.1. Automatic Control for Biomass-Fired Appliances

Álvarez-Murillo et al. [60] designed a control system using a programmable logic controller (PLC) to improve combustion in biomass stoves. PLC-controlled air and pellet supply systems provide higher efficiency and lower CO emissions. Different types of biomass fuels have been investigated. The highest power output was achieved with poplar pellets (8.77 kW) and the lowest with holm oak pellets (5.66 kW). The combination of automatic air supply control with an oxidizing catalyst was applied to the commercial fireplace and tested by Zhang et al. [61]. The authors burned batches of wood logs, and the control system operated based on signals: catalyst temperature, residual oxygen concentration, and CO/HC content in the exhaust. Motor-driven shutters controlled the inlet air streams. The results are very promising—the solutions provided reduced CO and PM emissions and increased efficiency. The same effect was achieved by Illerup et al. [62] after developing an automatically controlled system. The control parameters were oxygen concentration, flue gas temperature, and room temperature. In this case, air was supplied by three separate ducts and controlled with valves. Mižáková et al. [63] explored advanced methods for monitoring and controlling biomass combustion in small and medium-scale boilers, emphasizing not only O2 concentration in flue gas but also CO emission trends. The developed control algorithms dynamically assessed the relationship between CO and O2 levels, aiming to minimize oxygen concentration and reduce energy losses while keeping CO emissions within legal limits. The system proved effective with wood chips containing 35–45% moisture and up to 50% across various wood types, such as fir, beech, and oak. The authors in Ref. [64] investigated methods to reduce CO emissions during wood combustion in an accumulation-type stove-fireplace (SFA). The study first compared the combustion characteristics of beech wood of varying quality and then tested different control strategies for SFA operation. A prototype controller was developed using O2 and CO signals to regulate air throttles. The results confirmed that the system can meet the performance criteria set by BImSchV 2 and Ecodesign standards. Ye et al. [65] developed an advanced biomass boiler controller that utilizes embedded and wireless communication technologies, enabling local and remote control, data archiving, and signal monitoring. Designed for practical use, this system employed a fuzzy PID control strategy to enhance energy efficiency and real-time performance. Extensive testing confirmed the reliability of its electronics and software. The solution also proved cost-effective by reducing labor, time, and resource demands, indicating strong potential for widespread practical application. Pitel and Mižák [66] introduced new control algorithms for woodchip-fired boilers to achieve complete combustion with minimal excess air. Cost-effective CO and O2 sensors were selected to enable application in small-scale systems. Monitoring results from two boiler types confirmed the successful design and implementation of the automated biomass combustion control strategy. Miranda et al. [67] proposed a system that provided reliable and precise data, enabling a detailed analysis of combustion variables across different fuels and operating regimes. Its modular design enabled the integration of additional sensors (e.g., CO2 and incomplete combustion probes), making it a versatile tool for future studies on adapting conventional boilers for multi-fuel use. He et al. [68] introduced a predictive model, FOD-BP-ACO, designed to optimize control parameters in biomass boilers. The model used k-means clustering to classify operational states based on boundary parameters, including steam drum pressure, feedwater flow rate, and unit load. One of the key improvements was the application of delay parameter compensation, which reduced the model’s average relative error by 25.78%, demonstrating a significant enhancement in prediction accuracy. Numerical simulation and experimental validation of a pellet boiler were performed by Chen et al. [69]. The authors explored the optimal operating parameters. The balanced particle diameter and inlet air temperature were noted. The optimal negative pressure was set at 50 Pa. The effect of inlet air relative humidity was also investigated, reaching the optimal value at 50%.

4.2.2. Heat Accumulation

Despite numerous advantages, heat production in residential appliances—fireplaces and stoves—brings some challenges due to their discontinuous operation and, thus, transient heat emissions from the appliance or heat exchangers. The solution to this problem is to introduce heat storage. Heat storage materials based on fireclay have been known for centuries and are still in use, especially in Europe. Thus, stove-fireplaces with heat accumulation systems (SFA)—which blend the aesthetics of fireplaces with the functionality of traditional storage stoves—are gaining popularity. These systems store the heat generated from wood combustion in an accumulation heat exchanger, releasing it gradually for up to 12 h after the fire has gone out. Their thermal efficiency reaches around 90%, largely due to automated combustion control. Advanced optimizers regulate both the air supply to the furnace and the flue gas temperature within the exchanger, helping to prevent tar condensation, which can occur with low exhaust temperatures. Airflow is managed through one or more proportionally opening choke valves, which are adjustable from 0% to 100%. The air enters through multiple inlets, ensuring the thorough mixing of wood gasification byproducts with oxygen, resulting in clean and efficient biomass combustion [70]. An example of a stove-fireplace with heat accumulation is shown in Figure 12.

Figure 12.

An example of a stove-fireplace with heat accumulation [71].

Szubel et al. [72] performed both an experimental and a numerical analysis of an accumulative heat exchanger connected to a residential heating fireplace. Apart from insignificant divergences, the proposed model can be applied to heating appliance design. The ability and effectiveness of the accumulative heat exchanger in improving efficiency and reducing heat losses were highlighted. Furthermore, the study conducted by Żołądek et al. [73] identified operational differences among the accumulative wood stove, the steel stove with accumulation, and the traditional steel wood stove. Comparative analysis focused on the temperature distribution across the external surfaces of each unit and the corresponding energy transfer to the heated space. The surface temperature analysis revealed that the average temperature of a traditional steel stove was approximately 1.5 times higher than that of a steel stove equipped with an accumulation layer, and nearly three times higher than that of an accumulative stove. However, in terms of total heat transfer through the side walls, the accumulative stove demonstrated the highest output, at 14.6 MJ. In comparison, the steel stove with accumulation yielded the lowest, at 7.4 MJ. These findings were particularly relevant for energy-efficient and passive buildings, where minimizing overheating and maintaining thermal comfort are critical. On the other hand, as house insulation levels increase, there is a need to develop materials or other solutions that maintain stable heat release. Such a solution in the form of latent heat storage (LHS) has been proposed by Kristjansson et al. [74]. The authors simulated the use of phase change materials (PCMs) with different properties in combination with a wood stove using a numerical model. It was found that LHS predominates over sensible heat storage when stable heat release is required. Skreiberg et al. [75] used Erythritol as a PCM in a simulation of a cast iron stove to improve heat release performance. A 43% reduction in average (53% reduction in peak) heat emission was reported during the combustion cycle. Sevault et al. [76] performed a simulation using the same PCM. Still, they were located between the walls of coaxial cylinders placed above the outlet of the flue gases from the wood stove. The material released the heat over 6–10 h. The authors highlighted the potential issue of material degradation when burning multiple consecutive batches. Cablé et al. [77] performed a numerical analysis of a system combining a wood and a pellet stove, equipped with a heat exchanger and mechanical ventilation with heat recovery. Scenarios for different climate conditions were considered. The proposed solution significantly increased comfort in the rooms. Moreover, the heat exchanger recovered up to 611 kWh from the wood stove and up to 1281 kWh from the pellet stove over the space-heating season. An innovative heat exchanger was developed by Gallardo et al. [78]. The introduced solution could be applied in domestic heating and hot water appliances. The computational model of the heat exchanger showed increases in turbulent intensity, flue gas velocity, and residence time, leading to a higher total heat transfer rate.

4.2.3. Combined Heat and Power Generation

Biomass serves as a viable fuel source for combined heat and power (CHP) technologies, which not only deliver heat and electricity simultaneously but also significantly enhance process efficiency—from 30–35% up to 80% [79]. A range of micro-scale CHP technologies is discussed in the literature, including thermoelectric generators (TEGs), Stirling engines (SEs), Organic Rankine Cycle (ORC), fuel cells (FCs), and internal combustion engines (ICEs) [80].

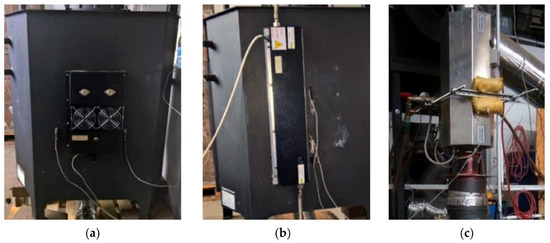

Thermoelectric Generators: One way to use the heat produced by residential appliances (fireplaces and stoves) is to generate electricity with thermoelectric generators (TEGs). This topic seems to be interesting, especially for off-grid areas and suburbs. Moreover, such a solution is a good answer for power outages during the heating season, as it can keep them operating or facilitate a safe shutdown. TEGs are devices that capture waste heat and transform part of it into usable electrical energy. Their operation is based on the Seebeck effect—a phenomenon where a temperature difference between two dissimilar metals or semiconductors generates a voltage. When these materials are connected in a closed circuit, the resulting voltage drives a continuous electric current through the system. TEGs can be used in various applications, including biomass-fired appliances. They can be mounted on the bodies of stoves and boilers, or on a flue gas channel, and utilize waste heat that would otherwise be removed to the atmosphere (see Figure 13). In this context, implementing TEGs can improve the energy efficiency of biomass-fired devices.

Figure 13.

A view of the steel stove with TEGs mounted on its rear wall (a,b) and flue gas channel (c) [81].

Najjar and Kseibi [82] carried out an analysis of a multi-purpose stove integrated with 12 TE modules. Their design featured an aerodynamically optimized combustor, a finned TEG base plate, a cooker, and a water heater for space heating. The system achieved a peak power output of approximately 7.88 W using fuels such as wood, manure, or peat, with an average overall stove efficiency of around 60%. Patowary and Baruah [83] conducted preliminary tests on a TEG-equipped cookstove, demonstrating its ability to produce 2.7 W of electrical power—sufficient to light a 3 W LED bulb. Guoneng et al. [84] developed and tested a micro-CHP system based on a TEG capable of delivering over 200 W of electrical power and more than 9.8 kW of thermal energy. The authors integrated a strategy encompassing heat collection, TEG wiring, power conditioning and storage, and temperature regulation. The system achieved a heat-collection efficiency of 34.16%, power-generation efficiency of 0.87%, and thermoelectric efficiency of 2.49%. Manfrida and Talluri [85] performed an exergy analysis of a thermoelectric wood fireplace, revealing an overall efficiency of 36.2%, with flue gases contributing the most to useful exergy. Sensitivity analysis revealed that a higher heat input improved exergy efficiency, whereas increasing the fireplace height reduced it due to a lower flame temperature. The number of TE modules had minimal impact, as electricity accounted for only 2% of total exergy output. Sornek et al. [86] studied three types of TEGs—one with air and two with water cooling types, with matched output powers of 45, 100, and 350 W, respectively. The highest power was achieved by a 100 W water-cooled TEG, yielding 31.2 W; however, an air-cooled 45 W TEG had the highest power-to-nominal power ratio, reaching 41.7%. Moreover, the authors claimed that water cooling is recommended due to the lower temperatures of TEG’s cold side. Tambunan et al. [87] also mounted an air-cooled TEG on the wall of the biomass stove. During the experiments, various types of biomass were tested, and for each, the electrical voltage generated was measured. The results showed that the electricity generated is not proportional to the fuel’s heating value. TEG with a matched power of 28.8 W was constructed and mounted on the flue gas chimney by Sornek and Papis-Frączek [88]. The tests were conducted in a wood-fired stove, with a fuel load of 8 kg of pinewood. The maximum power recorded was 15.9 W. The authors noted that the tested TEG version can enable self-sufficient stove operation. The same conclusion was reached in the work of Obernberger et al. [89]. In both works, the authors also performed CFD simulations. Baldini et al. [90] designed a heat flux concentrator to intensify heat transfer to the TEG modules using water cooling in the fireplace. In a 26 kW fireplace, 140 W of thermoelectric power could be produced. A CHP system consisting of TEG modules and a solid-fuel stove was also applied by Montecucco et al. [91]. TEG modules were located on the top of the stove and charged a lead-acid battery. However, the average electricity production was 27 W, and the TEG efficiency was around 5%. Another combination of TEG modules with a biomass-fired heating appliance was studied by Usón et al. [92]. In this work, a biomass boiler was equipped with TEG modules installed in its upper part. The maximum generated power during the test was almost 70 W (tap-water cooling). The authors identified ash deposition on TEG modules, resulting in significantly lower temperatures and power output.

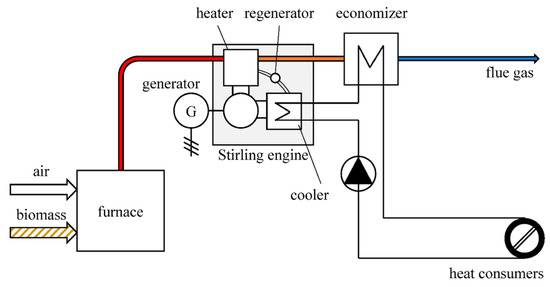

Stirling Engines: A Stirling engine is a closed heat engine in which the working medium (usually a gas, such as helium, hydrogen, or air) circulates between hot and cold zones. The following heating and cooling compress and expand the gas, causing the piston to move and generating mechanical work. A characteristic element of the design is a regenerator—a heat exchanger that temporarily stores thermal energy and returns it, increasing the cycle’s efficiency. A Stirling engine can utilize any external heat source (e.g., biomass combustion, solar concentrators, or waste heat), operates very quietly, and has a potentially high efficiency approaching the limits of the Carnot cycle. In this context, a proposed method for integrating a Stirling engine with a biomass-fired unit is shown in Figure 14.

Figure 14.

A biomass cogeneration unit with a Stirling engine [93].

Considering practical examples, Cardozo and Malmquist [94] tested a facility comprising a commercial wood pellet burner (20 kW), a prototype Stirling engine (1 kW), and a residential boiler (20 kW). The fuels used were wood and sugar cane bagasse pellets. Bagasse pellets produced more ash, which accumulates on the heat exchanger, thereby decreasing the efficiency of a Stirling engine CHP system compared to wood pellets. Kramens et al. [95] conducted experiments with a solid-biomass micro-CHP unit using a Stirling engine. The results showed that, from 1 kg of wood, 2.23 kWh of thermal energy and 7.84 kWh of electrical energy can be generated. Voronca et al. [93] tested the biomass Stirling micro-cogeneration device to assess its performance. Three heat transfer fluid flow rates and three thermal power outputs were set during the experiments. In the tested micro-CHP system, the DHW temperature was set to 60 °C. An increase in this temperature prevented the medium from absorbing the full thermal power. This caused the device to heat to 75 °C, triggering partial-load mode and reducing electricity production. Furthermore, an improved system—a biomass (wood pellet)-fueled micro-CHP unit—was tested by Borisov et al. [96]. This consisted of a Stirling engine, a two-stage vortex combustion chamber, an enhanced recuperator, and a waste heat-utilizing heat exchanger. The vortex application enhanced mixing in the combustion chamber and improved afterburning in the secondary chamber. The enlarged recuperator area led to a more uniform temperature field and a higher gas temperature. The proposed modifications enabled a 75% increase in the efficiency of a micro-CHP unit, while the Stirling engine achieved 14.8%.

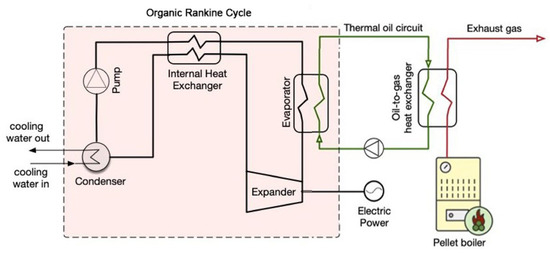

Organic Rankine Cycles: The Organic Rankine Cycle (ORC) is a modification of the classic Rankine Cycle that uses an organic fluid with a lower boiling point instead of water and steam. This enables the efficient conversion of low-temperature heat, such as that from biomass, geothermal energy, exhaust gases, or waste heat, into electricity. In the ORC, the working fluid is heated in a heat exchanger until it reaches its boiling point, at which point it subsequently evaporates. The steam then drives a turbine coupled to a generator, after which it is condensed and returned to the pump, completing the cycle. ORC technology is characterized by high reliability, quiet operation, and the ability to utilize moderate-temperature distributed heat sources, making it an attractive option in renewable energy and energy recovery applications, including biomass-fired appliances. A simplified layout of the biomass-boiler micro-ORC system is shown in Figure 15.

Figure 15.

Simplified layout of the biomass-boiler micro-ORC system [97].

Algieri and Morrone [98] investigated a biomass boiler-driven ORC for domestic use as a micro-scale CHP generation system. Three organic fluids were examined, and the feasibility of regeneration was evaluated. The results showed that the choice of organic working fluid is a crucial factor for system performance. The authors achieved a thermal power of over 14.8 kW (including electric power of 2.2–5.0 kW) for cogeneration. The system was considered a promising solution for small-scale residential applications. Villarino et al. [99] tested four different types of residual biomass in the 60 kW boiler combined with an ORC module. The net electrical power obtained during the test ranged from 3.33 to 3.60 kW, depending on the fuel. The authors report cogeneration yields of nearly 96% under the applied conditions. Furthermore, Falbo et al. [97] performed experimental studies on the energy performance of a biomass-fired recuperative ORC system. The highest net electric power was 2.3 kW (the highest pump speed was 2000 rpm, and the thermal oil temperature was 152.2 °C). The maximum electric efficiency of 8.55% was achieved at a pump speed of 1000 rpm, resulting in a net power output of 1.37 kW. The authors claimed that adjusting the pump speed is crucial for maximizing ORC performance and ensuring proper superheating of the working fluid.

Internal Combustion Engines: Gasification is a thermo-chemical process during which the initial fuel (biomass) is converted into gaseous fuels or chemical feedstock. The reaction is endothermic (requires heat) and takes place in a reducing (oxygen-deficient) atmosphere. Depending on costs and desired products, various media can be used in the process, including air, oxygen, subcritical steam, and mixtures [100].

Among other examples, the system proposed by Wang et al. [101] was driven by a gas-fired boiler, with gas generated from biomass in a biomass gasifier. The water vapor produced in the boiler was used in the CCHP system, which comprised a pumpless power cycle for electricity, a diffusion–absorption refrigeration cycle for cold energy, and heat exchangers for supplying domestic heat. The results indicated that the system is sufficient to meet the energy requirements of a single-family household, with power, cooling, and heating capacities ranging from 400 to 650 W, 500 to 900 W, and 1000 to 5000 W, respectively. The highest obtained energy efficiency was 55.26%. As the heat source temperature increases and the ambient temperature decreases, the system’s thermal efficiency improves, resulting in lower costs and reduced CO2 emissions. The optimal distribution ratios for cooling, heating, and power were studied, and in winter, the highest efficiency was achieved with a 0:5:5 ratio. In the summer, the worst-case scenario was 1.5:1.7.5. Similarly, Sunil et al. [102] developed a hot-water generation system based on a gasifier. The system significantly reduced pollutant emissions and achieved a thermal efficiency twice that of a conventional system with a gasifier and a separate hot water generator. The authors stated that this solution has high potential for residential applications. A single-family house with an area of 240 m2 was studied by Malaguti et al. [103]. The simulation, conducted using TRNSYS 17, features a small-scale gasifier power plant with 15 kW of electrical power and 20 kW of thermal power. The house has a diesel oil boiler, and a simulation was performed to validate the dynamic model. After that, the biomass boiler and, finally, the two micro-CHP gasifiers were simulated. A biomass boiler is more efficient than diesel oil and costs approximately one-third as much. The micro-CHP gasifier system has lower thermal efficiency due to energy consumption for gasification. It also has a higher fuel cost and consumes electrical energy. On the other hand, it is possible to sell the electrical energy to the electrical grid and heat the house without additional costs. Furthermore, Caliano et al. [104] designed a biomass-fired trigeneration system with thermal energy storage, comprising a CHP unit, an absorption chiller, an auxiliary gas boiler, and electrical chillers. The model referred to a residential multi-apartment building that provided electricity to the external grid, hot water for domestic use, and heating or cooling, depending on the season. The authors evaluated the impact of the incentive for electricity generation on the results, finding that it significantly influences the size of the thermal energy storage system, the absorption chiller, and the cold thermal energy storage system. However, unlike the absorption chiller, the size of the thermal energy storage system did not significantly affect the economic efficiency of the CCHP process. The authors considered integrating a cold thermal energy storage system as a viable economic solution.

The examples discussed demonstrate the high potential of biomass appliances as a heat source for combined heat and power generation. For small-scale applications, these systems can be used in residential, off-grid, and agricultural and commercial settings. The advantages and disadvantages of biomass-driven CHP systems are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Comparison of technologies integrated with biomass-driven CHP.

5. Integration of Biomass into NZEBs

The transition toward NZEBs requires integrating renewable energy sources and high-efficiency thermal systems to meet building energy demands with minimal environmental impact. Biomass, as a dispatchable, carbon-neutral energy carrier, offers a valuable complement to intermittent renewables such as solar and wind, particularly in climates with significant seasonal variability and during peak thermal demand. To enhance system flexibility and performance, biomass is increasingly deployed in hybrid configurations alongside solar thermal collectors, electrically driven heat pumps, and TES. These multivalent systems enable dynamic load management, improved combustion conditions, and higher shares of renewable energy. In particular, bivalent-parallel and bivalent-series arrangements allow for strategic operation: the former prioritizes heat pumps above a switchover temperature with biomass support during peak loads, while the latter utilizes heat pumps for preheating and biomass for final temperature elevation or thermal pasteurization. Effective integration requires the careful selection of bivalence points, weather-compensated control algorithms, and stratified storage design to minimize cycling losses, enhance overall system efficiency, and reduce pollutant emissions associated with frequent ignition or idle phases of solid-fuel appliances.

5.1. Integration of Biomass Appliances with Heat Pumps

Integrating biomass boilers with electrically or thermally driven heat pumps leverages the high seasonal efficiency of heat pumps operating at low supply temperatures while preserving the flexibility of biomass systems to cover peak demand and cold-weather conditions. Two main configurations are commonly used. In bivalent-parallel systems, the heat pump operates as the primary heat source above a defined switchover temperature, with the biomass boiler supplementing during peak loads. In bivalent-series systems, the heat pump preheats a stratified thermal buffer, and the biomass unit raises the temperature to the final setpoint or performs thermal pasteurization. Optimizing the bivalence point, applying weather-compensated control strategies, and using stratified thermal storage help minimize cycling of both units, enhance overall system efficiency, and reduce pollutant emissions typically associated with frequent ignition or idle phases of solid-fuel appliances.

Bellos et al. [105] investigated a biomass-driven absorption heat pump for heating and cooling a simulated 400 m2 residential building in Athens, Greece. The system was based on a single-effect LiBr–H2O absorption chiller, modified to provide winter heating, and was coupled, for the first time, with a biomass boiler. Compared with conventional oil boiler and electric heat pump setups, the proposed system achieved 10.8% lower operational costs, a 4.8% reduction in primary energy demand, and notable reductions in CO2 emissions. An experimental facility consisting of a pellet boiler and a hydrothermal heat pump was developed by Lee et al. [106] for smart farm heating. In comparison with a pellet boiler alone, the hybrid system offers higher thermal efficiency and lower operating costs. Uche et al. [107] simulated several systems—including an air-to-water heat pump, a biomass boiler, and their integration—for a residential building of 150 m2 in Spain. The hybrid system was found to be more effective in terms of energy efficiency, economics, and environmental considerations. The authors also studied different configurations of hybrid heat pump systems. In a serial system, an 8 kW pump yields the best results, while in a parallel system, a 4 kW pump performs better. The pump size also affects the number of on/off cycles for both the pump and the biomass boiler. In Ref. [108], the previous system was further analyzed, highlighting its dependence on the climate zone. Moreover, the authors emphasized the importance of building insulation in reducing costs.

Hebenstreit et al. [109] evaluated an active condensation system designed to recover heat from biomass boiler flue gases by integrating a quench unit with a compression heat pump. The system was modeled using mass and energy balances and assessed across four Austrian-based test cases: two pellet boilers (10 kW and 100 kW) and two wood chip boilers (100 kW and 10 MW). The results indicated reductions in operating costs of 2% to 13% and improvements in primary energy efficiency of 3% to 21%. Westerlund et al. [110] tested a novel energy recovery method that also reduces particulate emissions from flue gas in small biofuel boilers. By integrating an open absorption system into the heat production unit, both environmental impact and thermal efficiency were improved. Over a 2-year experimental period, the system achieved a 33–44% reduction in flue gas particle emissions compared to conventional setups. Additionally, when using wet biofuels, heat output increased by 40%, demonstrating the dual benefit of enhanced performance and lower emissions.

Although there are few studies on single houses, there are a few on district-scale solutions. For example, Drofenik et al. [111] examined a hybrid energy system that combines a micro-CHP unit (16 kW thermal power, 6.5 kW electrical power) fueled by biogas from local food waste with a heat pump (6.5 kW electrical input, 28.5 kW thermal output). Designed for integration into existing heating networks in Slovenian communities of up to 40,000 households, the system primarily targets DHW supply while replacing fossil-based sources. A simulation of a 3300-household community conducted with Aspen Plus showed that the hybrid setup can deliver more than twice the thermal output compared to the standalone micro-CHP. Economic analysis revealed a payback period of 7.2 years at a heat price of 80 EUR/MWh, which could be reduced to 3 years when scaled to serve 40,000 households. Hou et al. [112] conducted a performance and cost analysis of a centralized hybrid heating system serving a rural community in eastern China, with an annual heating demand of approximately 2 GWh. The system comprises a 310 kW geothermal heat pump, a 251 kW air-source heat pump, a 500 kW biomass boiler, and a thermal storage tank. Using TRNSYS simulations, the study compared the hybrid configuration to the standalone operation of each device. Over a one-year simulation, the heat supply distribution was 47% from the geothermal heat pump, 35% from the BB, and 18% from the air-source heat pump. The hybrid system demonstrated superior economic and energy performance, reducing operating costs by 9.6%, 14.2%, and 11.7% compared to the standalone geothermal heat pump, air-source heat pump, and biomass boiler, respectively. It also achieved the lowest power consumption, requiring only 34.3% of the biomass fuel compared to the standalone biomass boiler. Carotenuto et al. [113] developed a hybrid energy model for a low-temperature district heating and cooling system in Pozzuoli, Italy, integrating solar thermal, geothermal energy, and a wood-chip biomass boiler as an auxiliary source. The system was evaluated on both energy and economic grounds. Energy analysis revealed that the combined use of geothermal and solar sources is sufficient to meet winter heating demands. However, during summer, the biomass boiler becomes essential to achieve the elevated set-point temperatures required to operate an adsorption chiller for cooling. The system demonstrated solar thermal efficiency exceeding 40% and achieved primary energy savings of up to 75%.

5.2. Integration of Biomass Appliances with Solar Energy