Post-Operative Scar Comparison With Supraorbital Eyebrow and Upper Blepharoplasty Approach in the Management of Zygomaticomaxillary Complex Fractures

Abstract

:Introduction

Patients and Methods

Inclusion Criteria

- Patients with clinically and radiographically diagnosed tripod/tetrapod fracture of ZMC

- Patients in the age group of 18–60 years.

- The time gap between the day of trauma to hospital admission should be <3 weeks

- Subject consent to participate.

Exclusion Criteria

- Medically compromised patients unfit for major surgery

- Previously treated frontozygomatic process fractures

- Infected frontozygomatic process fractures

- Frontozygomatic process fractures with associated open wound

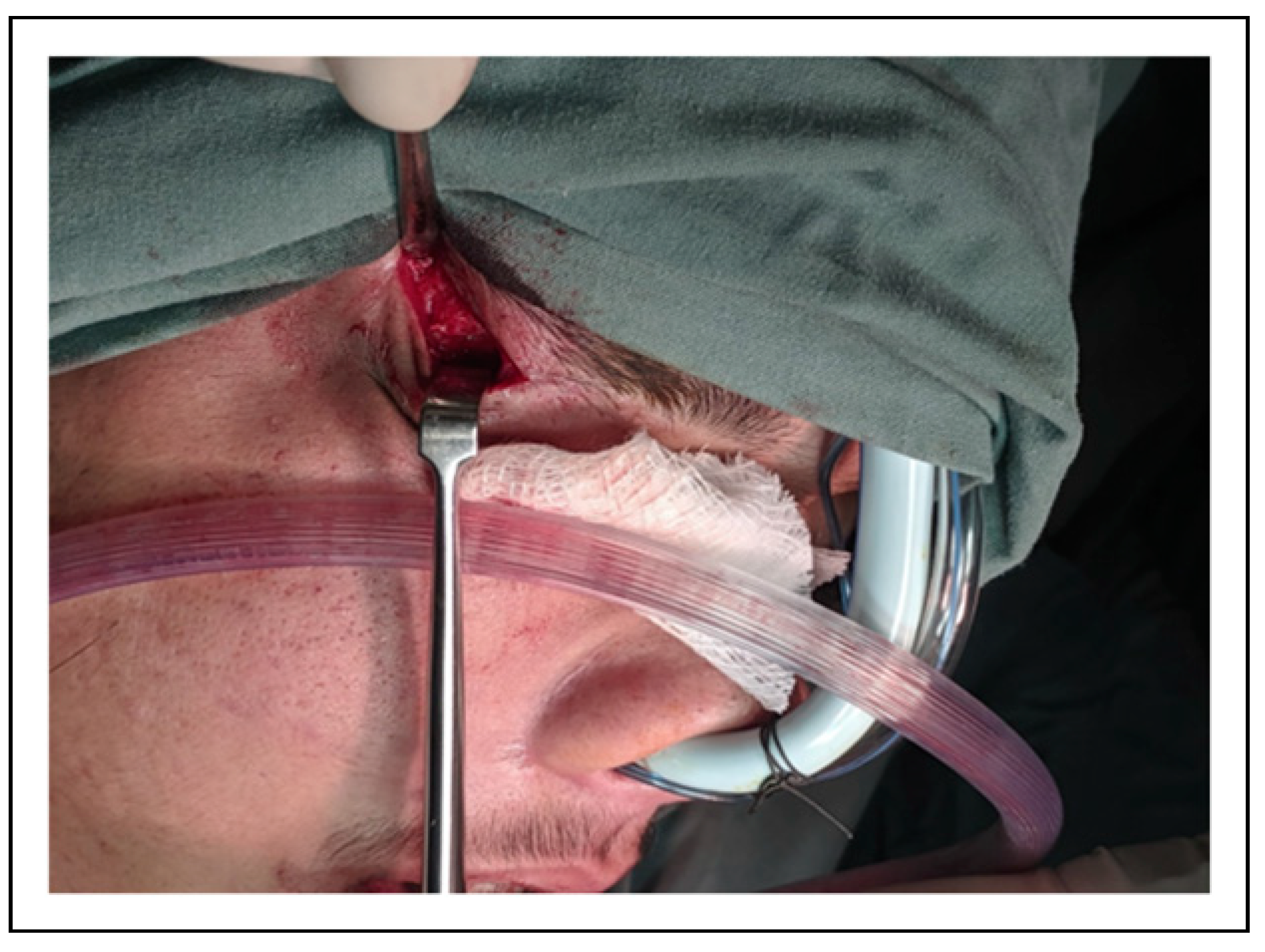

Surgical Procedure

Results

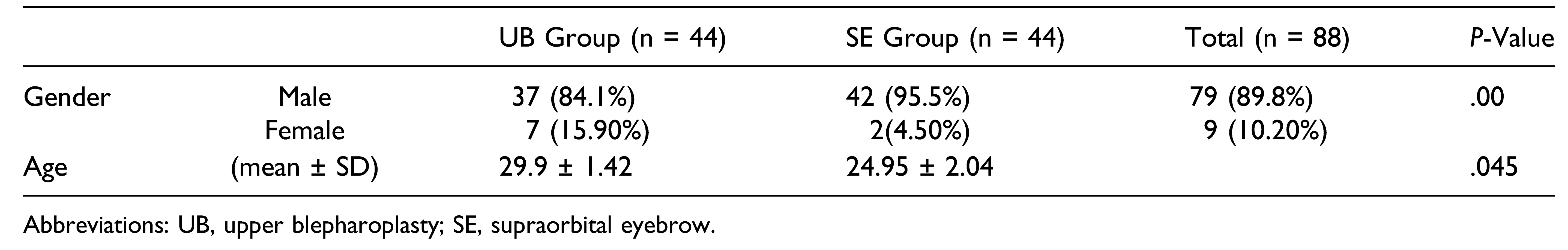

Demographic Results

Clinical Results

Discussion

Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Modabber, A.; Rana, M.; Ghassemi, A.; et al. Three-dimensional evaluation of postoperative swelling in treatment of zygo- matic bone fractures using two different cooling therapy methods: a randomized, observer-blind, prospective study. Trials. 2013, 14, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Udeabor, S.; Akinmoladun, V.I.; Olusanya, A.; Obiechina, A. Pattern of midface trauma with associated concomitant in- juries in a Nigerian referral centre. Niger J Surg. 2014, 20, 26–29. [Google Scholar]

- Noor, M.; Ishaq, Y.; Anwar, M.A. Frequency of infra-orbital nerve injury after a Zygomaticomaxillary complex fracture and its functional recovery after open reduction and internal fixation. Int Surg J. 2017, 4, 685–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barta, R.J.; Schubert, W. Ratio of simple versus comminuted lateral wall fractures of the orbit. Craniomaxillofacial Trauma Reconstr. 2013, 6, 241–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zingg, M.; Laedrach, K.; Chen, J.; et al. Classification and treatment of zygomatic fractures: a review of 1, 025 cases. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1992, 50, 778–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinho, R.O.M.; Freire-Maia, B. Management of fractures of the zygomaticomaxillary complex. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin 2013, 25, 617–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thangavelu, K.; Ganesh, N.S.; Kumar, J.A.; Sabitha, S. Evaluation of the lateral orbital approach in management of zygomatic bone fractures. J Nat Sci Biol Med. 2013, 4, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.T.; Go, D.H.; Jung, J.H.; Cha, H.E.; Woo, J.H.; Kang, I.G. Comparison of 1-point fixation with 2-point fixation in treating tripod fractures of the zygoma. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2011, 69, 2848–2852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raschke, G.F.; Rieger, U.M.; Bader, R.D.; et al. The zy- gomaticomaxillary complex fracture–an anthropometric ap- praisal of surgical outcomes. J Cranio Maxillofac Surg. 2013, 41, 331–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golan, S.; Goldberg, R.A. Time course analysis of upper blepharoplasty complications. Dermatol Surg. 2017, 43, 307–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 11. Candamourty, R.; Narayanan, V.; Baig, M.; Muthusekar, M.; Jain, M.K.; Babu, R.M. Treatment modalities in zygomatic complex fractures: A prospective short clinical study. Dent Med Res. 2013, 1, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strong, E.B.; Gary, C. Management of zygomaticomaxillary complex fractures. Facial Plast Surg Clin. 2017, 25, 547–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rallis, G.; Stathopoulos, P.; Igoumenakis, D.; Krasadakis, C.; Mourouzis, C.; Mezitis, M. Treating maxillofacial trauma for over half a century: how can we interpret the changing patterns in etiology and management? Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2015, 119, 614–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markiewicz, M.R.; Gelesko, S.; Bell, R.B. Zygoma reconstruc- tion. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin. 2013, 25, 167–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kochhar, A.; Byrne, P.J. Surgical management of complex midfacial fractures. Otolaryngol Clin. 2013, 46, 759–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, N.; Goyal, M.; Mishra, B.; Dhasmana, S. Zygomatic complex fracture: a comparative evaluation of stability using titanium and bio-resorbable plates as one point fixation. Natl J Maxillofac Surg. 2013, 4, 181. [Google Scholar]

- Monstrey, S.; Middelkoop, E.; Vranckx, J.J.; et al. Updated scar management practical guidelines: non-invasive and invasive measures. J Plast Reconstr Aesthetic Surg. 2014, 67, 1017–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.A.; Feldstein, S.I.; Shumaker, P.R.; Krakowski, A.C. A review of scar assessment scales. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2015, 34, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gankande, T.; Wood, F.; Edgar, D.; et al. A modified vancouver scar scale linked with TBSA (mVSS-TBSA): inter-rater re- liability of an innovative burn scar assessment method. Burns. 2013, 39, 1142–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ud-Din, S.; Bayat, A. Non-invasive objective devices for monitoring the inflammatory, proliferative and remodelling phases of cutaneous wound healing and skin scarring. Exp Dermatol. 2016, 25, 579–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sofie Pinney, D. Perioperative management of painful scars. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Son, D.; Harijan, A. Overview of surgical scar prevention and management. J Kor Med Sci. 2014, 29, 751–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishida, K. Evolution of the surgical approach to the orbitozy- gomatic fracture: From a subciliary to a transconjunctival and to a novel extended transconjunctival approach without skin in- cisions. J Plast Reconstr Aesthetic Surg. 2016, 69, 497–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

|

|

© 2022 by the author. The Author(s) 2022.

Share and Cite

Mirza, H.H.; Ahmed, F.; Rahber, M.; Rana, Z.A. Post-Operative Scar Comparison With Supraorbital Eyebrow and Upper Blepharoplasty Approach in the Management of Zygomaticomaxillary Complex Fractures. Craniomaxillofac. Trauma Reconstr. 2023, 16, 268-274. https://doi.org/10.1177/19433875221124406

Mirza HH, Ahmed F, Rahber M, Rana ZA. Post-Operative Scar Comparison With Supraorbital Eyebrow and Upper Blepharoplasty Approach in the Management of Zygomaticomaxillary Complex Fractures. Craniomaxillofacial Trauma & Reconstruction. 2023; 16(4):268-274. https://doi.org/10.1177/19433875221124406

Chicago/Turabian StyleMirza, Hamza H., Faheem Ahmed, Murtaza Rahber, and Zahoor A. Rana. 2023. "Post-Operative Scar Comparison With Supraorbital Eyebrow and Upper Blepharoplasty Approach in the Management of Zygomaticomaxillary Complex Fractures" Craniomaxillofacial Trauma & Reconstruction 16, no. 4: 268-274. https://doi.org/10.1177/19433875221124406

APA StyleMirza, H. H., Ahmed, F., Rahber, M., & Rana, Z. A. (2023). Post-Operative Scar Comparison With Supraorbital Eyebrow and Upper Blepharoplasty Approach in the Management of Zygomaticomaxillary Complex Fractures. Craniomaxillofacial Trauma & Reconstruction, 16(4), 268-274. https://doi.org/10.1177/19433875221124406