Abstract

Study Design: A retrospective cohort study was conducted using the Kids’ Inpatient Database from 2000 to 2014. Subjects were included if they were 18 years and younger and suffered any type of facial fracture. Objective: The purpose this study was to determine the risk factors for incurring panfacial fractures among the pediatric population. Methods: The primary predictor variables were a set of heterogenous variables that included patient characteristics, injury characteristics, hospitalization outcomes. The primary outcome variable was panfacial fracture. Logistic regression was used to determine the independent risk factors for panfacial fractures. Results: Relative to infants and toddlers, teenagers were nearly three times more likely to sustain panfacial fractures (P < .01). Relative to no chronic conditions, patients with one or more chronic conditions were more likely to incur panfacial fractures. Motorcycle accidents were over three times more likely (P < .01) to result in panfacial fractures while car accidents were over two times more likely (P < .01) to result in panfacial fractures. Falls were less likely (OR, .39; P < .01) to result in panfacial fractures. Conclusions: Motor vehicle accidents was a major risk factor for panfacial fractures. Teenagers are also found to have an increased risk for panfacial fractures relative to infants and toddlers. Each additional chronic condition was a significant risk factor for suffering panfacial fractures relative to not having any chronic condition at all. In contrast, falls independently decreased the risk of incurring a panfacial fractures. Special attention should be given to safety precautions when occupying a motor vehicle.

Introduction

Panfacial fractures are defined as fractures that involve the upper (frontal bone), middle (malar bone & maxilla, orbital floor), and lower thirds of the face (mandible).[1] Coupled with the awareness that pediatric facial fractures are often associated with significant injury, panfacial trauma can be very difficult to treat among children.[2,3] Surgeons must account for biological factors such as pediatric anatomy and bony facial growth. Therefore, treatment modalities might be more conservative, such as closed treatment with arch bars, to account for these variables.[2]

There is less literature on pediatric panfacial trauma compared to adult panfacial trauma. This is not surprising, as pediatric patients constitute only about 15% of all facial fractures.[4] This is largely because of features unique to the pediatric craniomaxillofacial skeleton—high degree of bone elasticity, unpneumatized paranasal sinuses, unerupted dentition supporting the jaws, and prominent buccal fat pads shielding the malar bones.[5,6] In addition, adults participate in activities that could result in facial trauma to a greater extent than children, who are not fully independent and still under adult care. Adults are much more likely to use a motor vehicle as part of their occupation and are thus naturally predisposed to motor vehicular accidents, the leading cause of facial trauma.[7] Hence, the authors intend to shore the literature deficiency surrounding pediatric facial trauma.

The purpose of the following study is to answer the following clinical question: what are the risk factors for incurring panfacial fractures among the pediatric population? Based on the literature, we hypothesize that motor vehicle accidents (MVAs) would be a major risk factor. More specifically, the authors sought to compare the incidence of panfacial fractures across demographic variables (i.e., sex), past medical history (i.e., number of chronic conditions), hospitalization outcomes (i.e., admission type), mechanisms of injury (i.e., fall), and other miscellaneous patient characteristics (i.e., alcohol abuse). The authors also planned to compute independent risk factors ratios for incurring panfacial fractures.

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Sample Selection

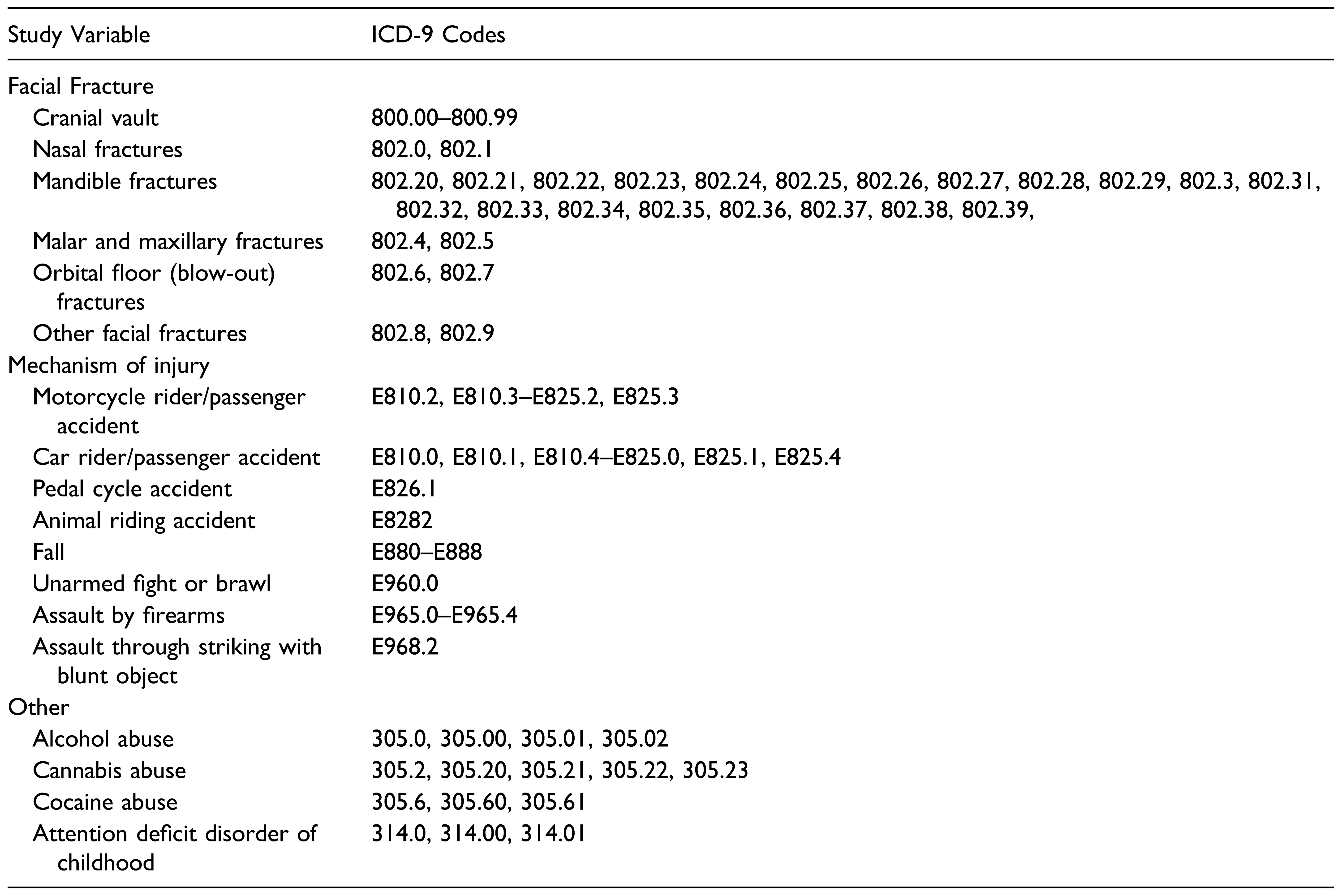

This is a retrospective cohort study that was conducted using the Kids’ Inpatient Database (KID). The KID is developed for the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) and is the largest publicly available all-payer pediatric inpatient care database in the United States. It includes information on roughly three million pediatric discharges each year.[8] Patients from the 2000–2012 KID datasets were included in the study if they were 18 years and younger and suffered any type of facial fracture. Table 1 illustrates all the diagnostic and procedure ICD-9 codes used to identify the study sample of interest and variables of interest.

Table 1.

ICD-9 codes used to identify subjects and define variables.

Variables

The study variables included patient characteristics, injury characteristics, hospitalization outcomes. Patient characteristics included age group (0–2, 3–5, 5–12, 13–18 years), sex (male or female), race (White, Black, Hispanic, Asian, or other), median household income, location, payer information, number of chronic conditions, miscellaneous patient characteristics. Injury characteristics include panfacial fracture and mechanism of injury. Hospitalization outcomes include admission type, hospital region, hospital transfer (into/out), and hospitalization year (2000–2002, 2003–2005, 2006–2008, 2009–2011, 2012–2014).

The primary predictor variables were a set of heterogenous variables that were grouped into the forementioned study variable groups above (patient characteristics, injury characteristics, hospitalization outcomes). The primary outcome variable was panfacial fracture. Median household income was a categorical variable of income quartiles (Q1, Q2, Q3, and Q4) that was based on the patient’s ZIP Code. Location was a three-category scheme that classified counties according to their population size and whether they were urban or rural. Payer information indicates the primary payer of treatment (Medicare/Medicaid, private, or selfpay). Number of chronic conditions was a categorical variable (one, two, three, four or more). The miscellaneous patient characteristics included whether patients were alcohol abusers, cannabis abusers, cocaine abusers, or had attention deficit disorder of childhood.

Panfacial fractures were defined as fractures that involved the upper (frontal bone), middle (malar bone & maxilla, orbital floor), and lower thirds of the face (mandible). The ICD9 coding system codes for the cranial vault, which constitutes the upper third of the face (frontal bone). The mechanism of injury studied included motorcycle accidents, car accidents, pedal cycle accidents, animal riding accidents, falls, unarmed fights/brawls, assault by firearms, assault through striking with blunt object. Admission type is binary (elective or not elective). Hospital region is a 4-category variable (Northeast, Midwest, South, West).

Data Analyses

Descriptive statistics (mean, frequency, range, standard deviations) were computed for all study variables when possible. Bivariate analyses (chi square) were conducted to determine potential associations between the primary predictor variables and the primary outcome variable (panfacial fracture). Independent sample t test and ANOVA were used to determine significant differences between groups for continuous variables. Binary logistic regression was used to determine independent risk factors for panfacial fractures. A P value of less than .05 was considered statistically significant. We used SPSS version 28 for Mac (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) to perform all statistical analyses. Since the KID is a database that is both publicly available and anonymized, we did not require institutional board review consistent with our medical center’s policy.

Results

The 2000–2012 KID database consisted of 15,235,214 pediatric patients who were hospitalized for various reasons. After filtering for patients aged 18 years or less who suffered facial fracture(s), a final study sample comprised of 50,434 patients was achieved, of whom 670 (1.33%) suffered panfacial fractures. The mean age of the study sample was 9.72 years (SD, 6.84 years). Most subjects were White (55.8%) teenagers (46.1%) who lived in large metro areas (60.2%). Subjects were evenly distributed across median household income quartiles. Most subjects didn’t have any chronic condition (63.8%). As the number of chronic conditions increased, the frequency of subjects having facial fractures decreased. The most common mechanism of injury was falls (22.08%), followed by car accidents (17.85%).

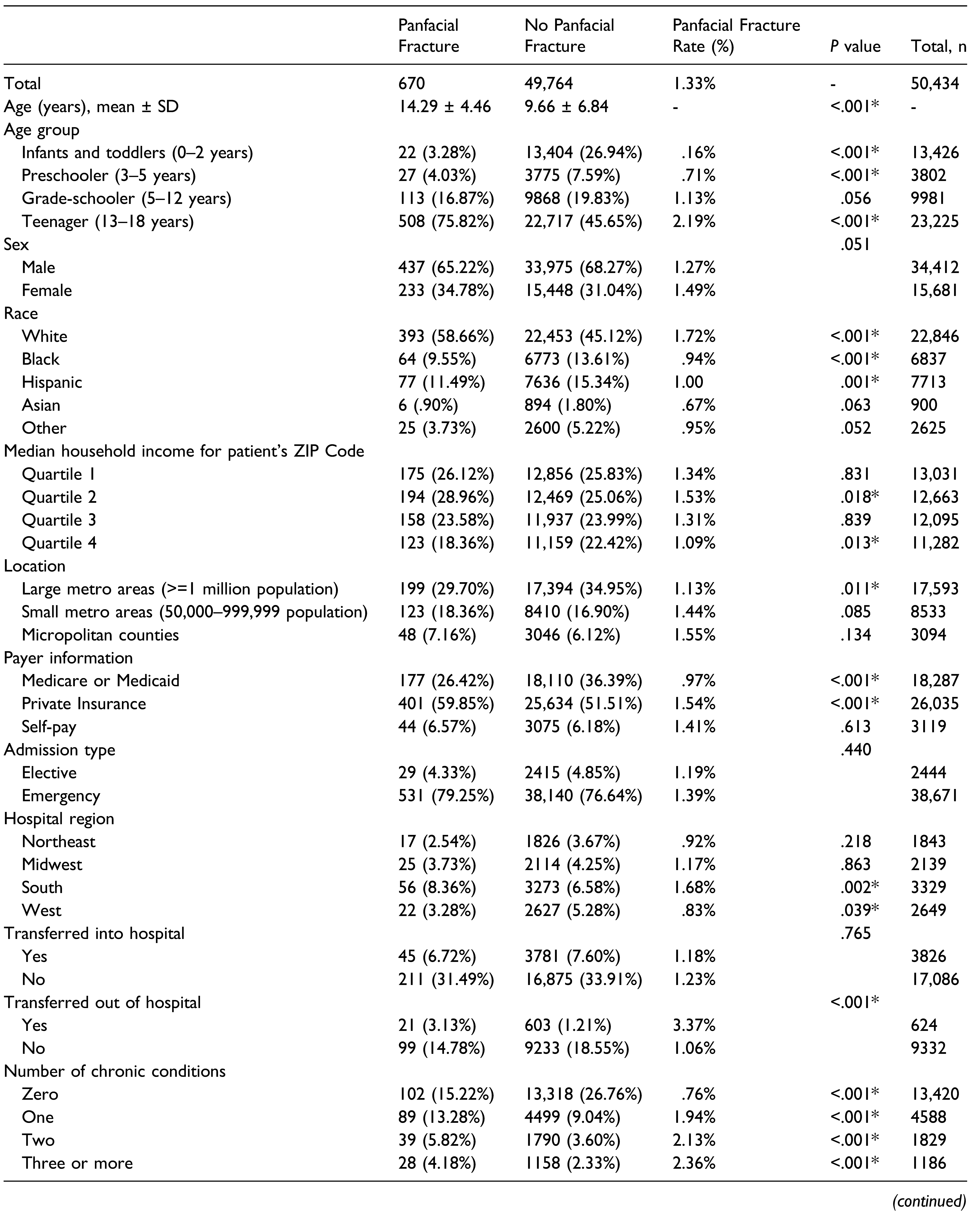

Table 2 illustrates the distribution of subject characteristics, hospitalization outcomes, and mechanism of injury across panfacial fracture. Subjects who suffered panfacial fractures (14.29 years) were significantly older (P<.001) than subjects who did not (9.66 years). Panfacial fractures were more likely to occur among teenagers (75.82% vs. 45.65%; P<.01) and less likely to occur among infants and toddlers (3.28% vs. 26.94%; P < .01) and preschoolers (4.03% vs. 7.59%; P < .01). Panfacial fractures were more common among White subjects (58.66% vs. 45.12%; P < .01) and less common among Black (9.55% vs. 13.61%; P < .01) and Hispanic subjects (11.49% vs. 15.34%; P < .01). With respect to income status, panfacial fractures were more common among subjects within the second income quartile (29.96% vs. 25.06%; P < .05) and less common among subjects within the fourth income quartile (18.36% vs. 22.42%; P < .05). With regards to geographical location, panfacial fractures were less likely to occur among subjects residing in large metro areas (29.70% vs. 34.95%; P < .05). Panfacial fractures were more common among privately insured subjects (59.85% vs. 51.51%; P < .01) and less common among Medicare/Medicaid patients (26.42% vs. 36.39%; P < .01). Hospital region-wise, panfacial fractures were common in the south (8.36% vs. 6.58%; P < .01) and less common in the west (3.28% vs. 5.28%; P < .05). Subjects who incurred panfacial fractures were more likely to be transferred out to another hospital or healthcare facility (3.13% vs. 1.21%; P < .01). Panfacial fractures were less common among individuals with no chronic conditions (15.22% vs. 26.76%; P < .01) and more common among subjects with one (13.28% vs. 9.04%; P < .01), two (5.82% vs. 3.60%; P < .01), and three or more (4.18% vs. 2.33%; P < .01) chronic conditions (Table 2).

Table 2.

Subject characteristics, hospitalization outcomes, and mechanism of injury across panfacial fracture.

Panfacial fractures were more common in 2006–2008 (24.48% vs. 21.29%, P<.05) and more likely to result from motorcycle accidents (3.73% vs. 1.31%; P < .01), car accidents (43.28% vs. 17.50%; P < .01), and car accidents among intoxicated (alcohol) subjects (2.39% vs. .66%; P < .01). They were less likely like to result from falls (3.43% vs. 22.33%; P < .01) and unarmed fights/brawls (1.49% vs. 5.79%; P < .01). Finally, panfacial fractures were more likely among alcohol abusers (3.88% vs. 2.43%; P < .01) (Table 2).

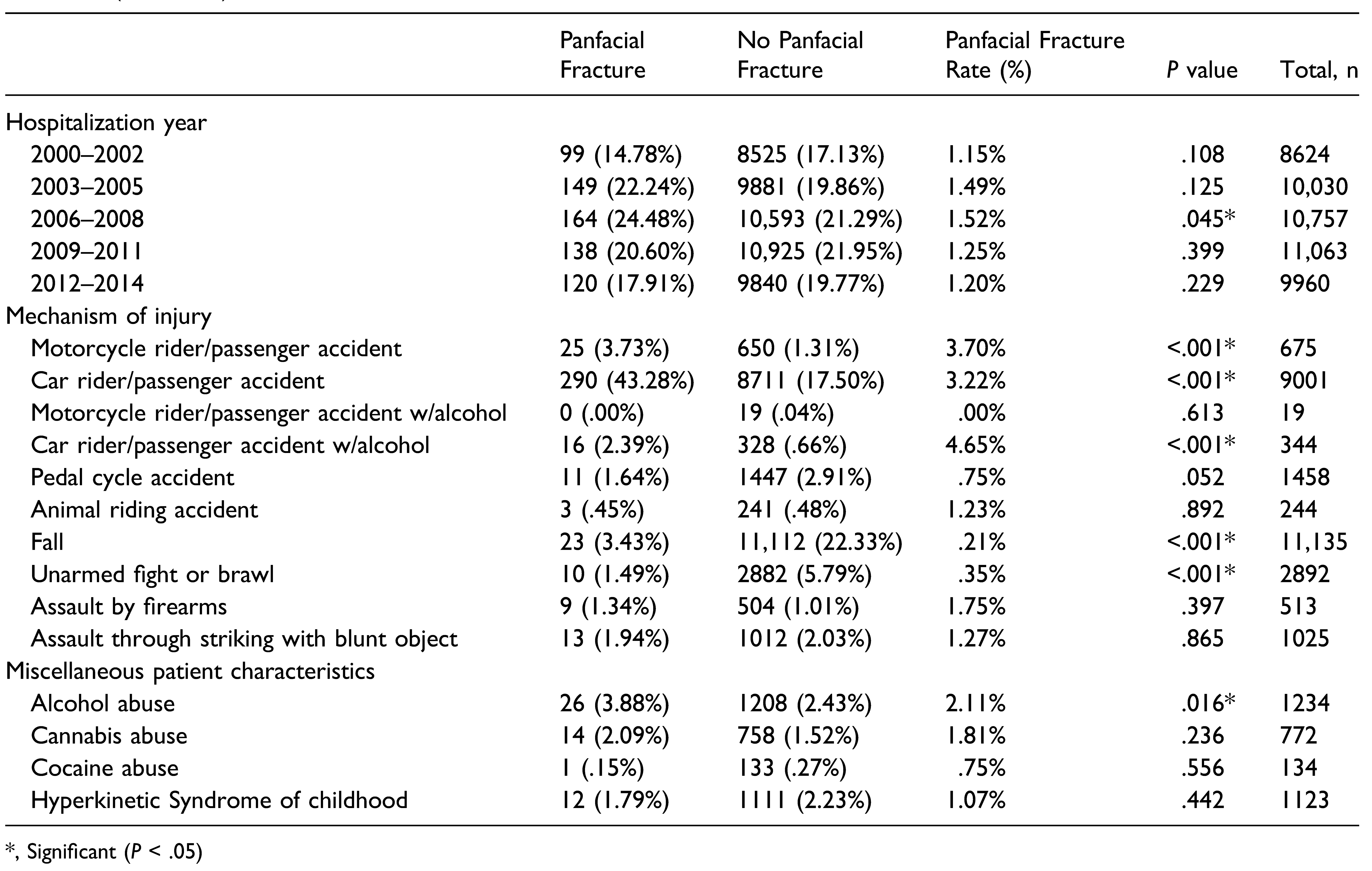

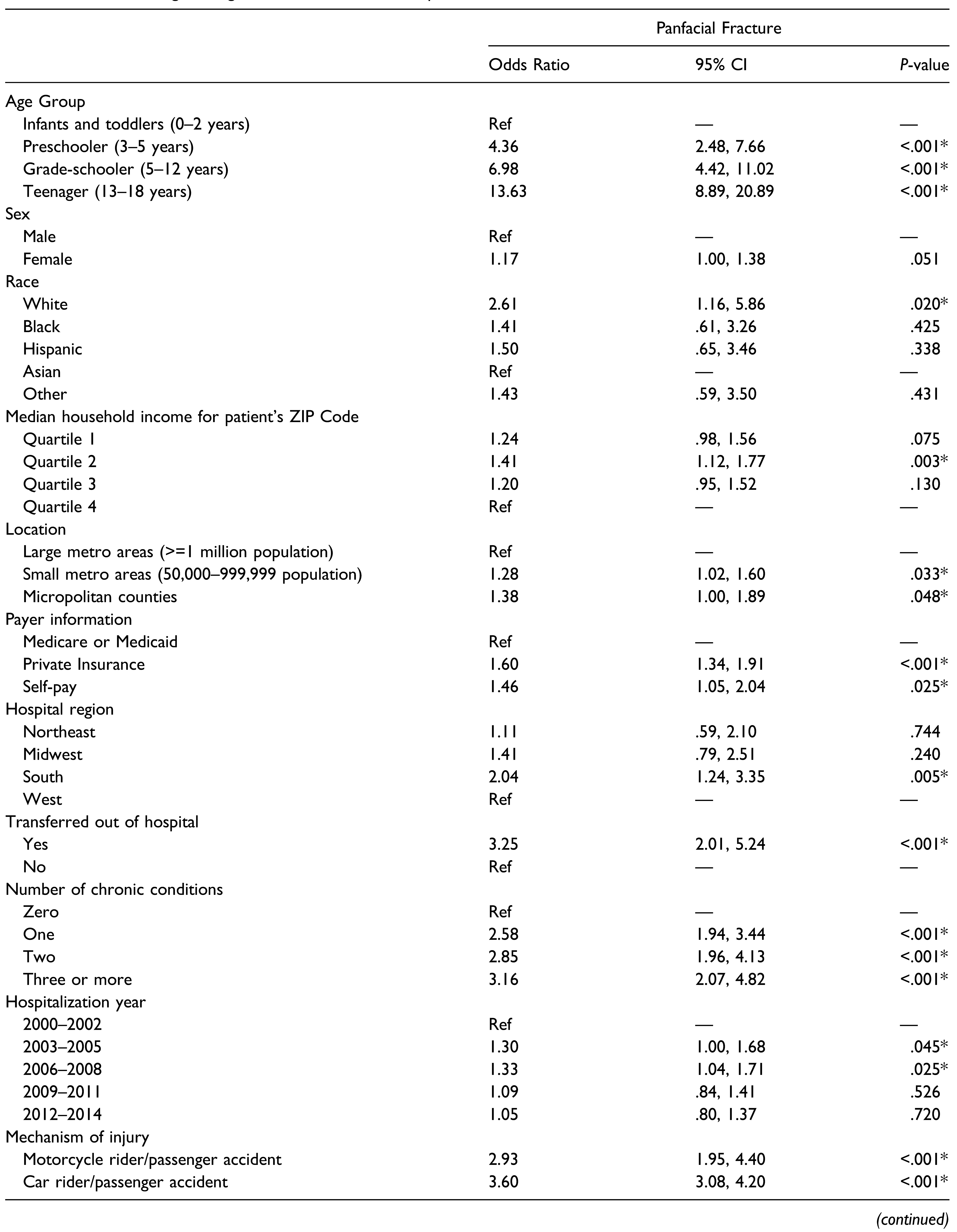

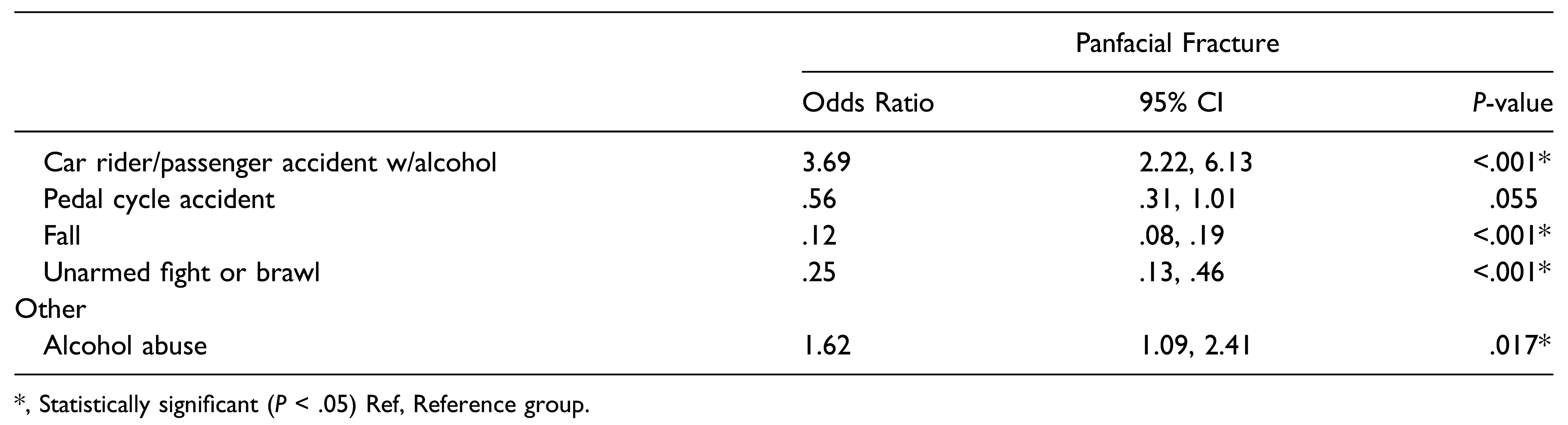

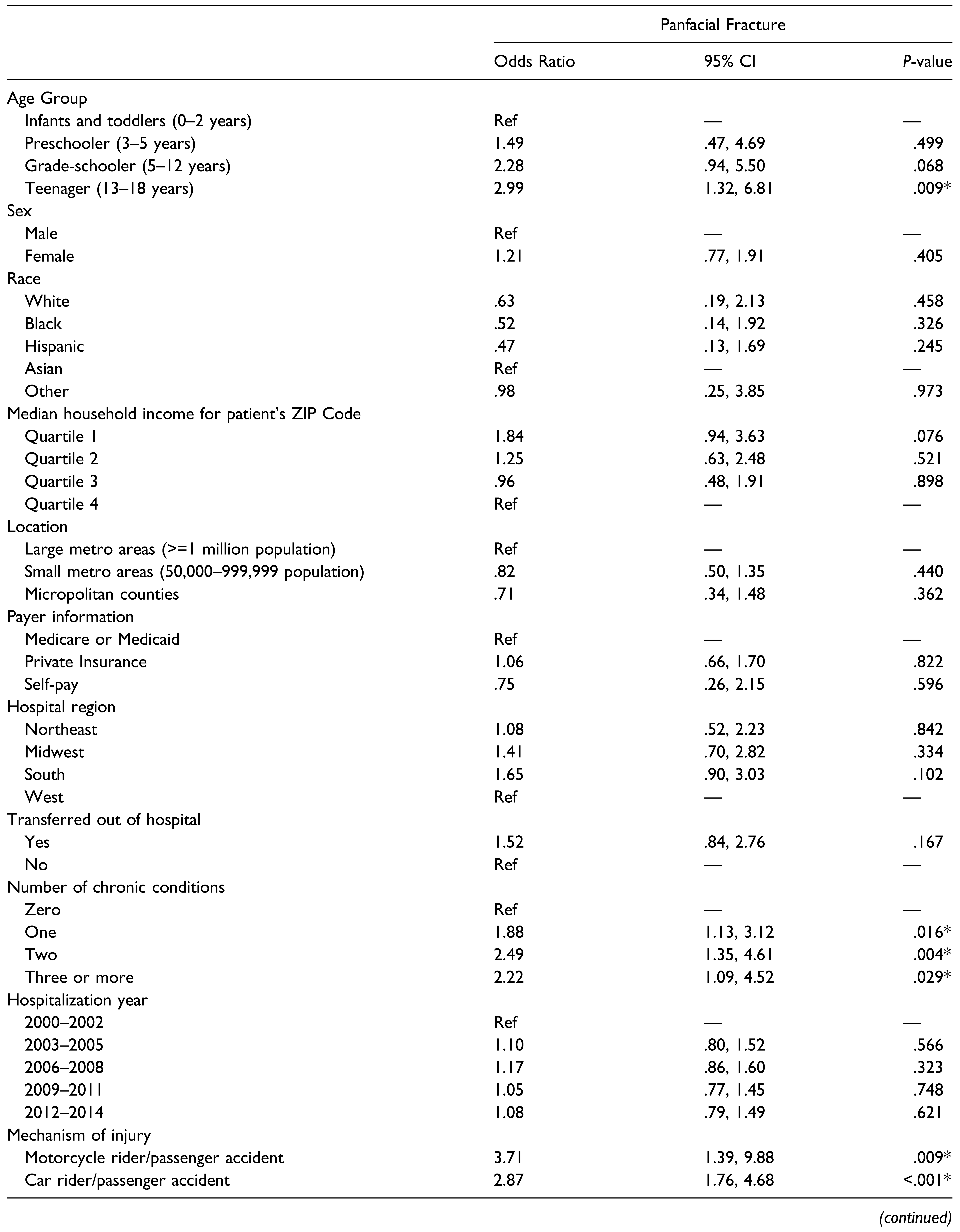

Age group, race, median household income, location, payer information, hospital region, patients transferred out, number of chronic conditions, motorcycle accidents, car accidents, falls, unarmed fights, and alcohol abuse were all significant predictors (P < .01) of panfacial fractures. Sex, calendar year, and pedal cycle accidents were near significant predictors (P < .20) and, hence, were also added to the regression model. Univariate logistic regression was conducted to determine independent risk factors for incurring panfacial fractures (Table 3). After controlling for all potential covariates, multiple logistic regression was conducted. Relative to infants and toddlers, teenagers were nearly three times more likely to sustain panfacial fractures (P < .01). Relative to subjects with no chronic condition, subjects with one chronic condition (OR, 1.88; P < .05), two chronic conditions (OR, 2.49; P < .01), and three or more chronic conditions (OR, 2.22; P < .05) were each independent risk factors for incurring panfacial fractures. Motorcycle accidents were over three times more likely (P < .01) to result in panfacial fractures while car accidents were over two times more likely (P < .01) to result in panfacial fractures. Falls were less likely (OR, .39; P < .01) to result in panfacial fractures (Table 4).

Table 3.

Univariate logistic regression model for odds of panfacial fracture.

Table 4.

Multivariate logistic regression model for odds of panfacial fracture.

Discussion

The purpose this study was to investigate which factors increased the risk of incurring panfacial fractures among the pediatric population. Based on the literature, the authors hypothesized that motor vehicle accidents would be a risk factor for panfacial fractures. More specifically, the authors sought to compare the incidence of panfacial fractures across demographic variables (i.e., sex), past medical history (i.e., number of chronic conditions), hospitalization outcomes (i.e., admission type), mechanisms of injury (i.e., fall), and other miscellaneous patient characteristics (i.e., alcohol abuse).

The results of the study indicated that subjects who suffered from panfacial fractures (14.29 years) were significantly older than subjects who suffered from one or more facial fractures (9.66 years). Furthermore, the results also showed that panfacial fractures were more likely to occur in teenagers compared to infants, toddlers, and preschoolers. Our results are consistent with the literature, which illustrates that the incidence of pediatric facial fractures is most common in the adolescent stage. Vyas et al. reported that 55.9% of all pediatric facial fractures are within the 15–17 year group.[4] Additional investigations by Grunwaldt et al. and Imahara et al. support this finding, revealing that the largest incidence of facial fractures occurred in the 12–18 and the 15–18 groups, respectively.[3,9] The authors speculate that this could be since teenage adolescents are more likely to be unsupervised compared to younger children. Younger children tend to be under close supervision of an adult(s), whereas adolescents may independently engage in sports, driving, and risky activities that predispose them to facial injury and ultimately panfacial fractures. The adult population, with developed frontal cortices and significant experience, often make safer decisions which decrease their chances of bodily injury for themselves and their younger supervisees. The absence of an adult may lead to a higher likelihood of a traumatic event resulting in a panfacial fracture.

Panfacial fractures were more likely to result from motorcycle accidents and car accidents. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, there is only one other paper dedicated to the topic of pediatric panfacial fractures, by Delana et al. This group reported that motor vehicle accidents (MVAs) were among the most common etiologies of pediatric panfacial fractures seen at an urban, level 1 trauma center.[10] These results are in line with our hypothesis that MVAs are a major risk factor for panfacial fractures. Furthermore, many sources state that most facial fractures (both panfacial and non-panfacial) among children result from MVAs.[3,11,12,13,14,15,16] From these well-established facts, it is feasible to assume that the severity of MVAs as an etiology for pediatric facial fractures may also apply to pediatric panfacial fractures. Cars and motorcycles are popular methods of transportation yet may lead to deadly consequences if used incorrectly or accidently. MVAs may commonly cause injuries such as brain trauma, internal bleeding, and spinal cord damage. The human body was not designed to withstand the transfer of kinetic energy that transpires during collisions with other motor vehicles or standing objects. As such, it is not surprising that panfacial fractures may also result from these accidents.

Compared to non-panfacial fractures, panfacial fractures were less likely to result from falls. The authors speculate that falling victims are able to cushion their fall with an outstretched arm, leading to a relative lower occurrence of panfacial fractures. Additionally, falls entail a significantly smaller amount of kinetic energy relative to a MVA and, thus, often do not yield enough force to exceed the threshold for panfacial fractures.

Each additional chronic condition conferred a significant risk for incurring panfacial fractures. Most notably, patients with two chronic conditions were 2.5 times more likely to suffer panfacial fractures. Common chronic childhood diseases include asthma, diabetes, cystic fibrosis, obesity, and developmental disabilities. As of 2018–2019, approximately 40% of school-aged children and adolescents have at least one chronic health condition, and 20–25% have two or more chronic health conditions in the United States.[17] A reasonable explanation concerning the link between chronic conditions and the risk for incurring panfacial fractures is that chronic conditions result in a physically delicate body. For example, children who suffer from malnutrition, physical deformities, or hormonal imbalances may have a fragile maxillofacial complex, explaining the heightened risk of panfacial fractures. Furthermore, conditions such as neurodevelopmental disorders or obesity may interfere with the body’s ability to protect oneself from violence, accidents, or falls. Future, separate investigations into this area may yield more fruitful analysis.

Generalized panfacial fractures (including both pediatric and non-pediatric populations) are predominantly caused by MVAs, lending credibility to the results of this study.[18,19,20] Motorcycle accidents were over three times more likely (P < .01) to result in panfacial fractures, which was greater than the risk imposed by car accidents. This can be reasoned by understanding that motorcyclists are particularly vulnerable, due to the lack of a protective barrier and being at the mercy of blind spots. Furthermore, advancements in car safety may explain this difference. In fact, the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration reports that motorcyclists are four times more likely to be injured compared to a car occupant per vehicle mile traveled.[21]

The findings in this study are not without limitations. This study pulls information from a database which only records facial fractures as they pertain to inpatient care. Therefore, this database may not accurately depict the full pediatric population which suffers from facial fractures, as some may have been handled in an outpatient setting or not received medical attention at all. Since the type of fracture which can be treated in an outpatient setting is likely to be minor than not, it is possible that the data underrepresents non-panfacial fractures. Despite this limitation, it should be noted that this study pulls data from a national database, as opposed to data from a single institution or geographic region. As such, this study presents strong external validity. The results of this study confirm the hypothesis that MVAs are a major risk factor for panfacial fractures in the pediatric population. In contrast, falls independently decreased the risk of incurring panfacial fractures. Teenagers are at risk for panfacial fractures relative to infants and toddlers. Finally, each additional chronic condition was a significant risk factor for suffering panfacial fractures relative to not having any chronic condition at all. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, this study investigates the largest group of pediatric panfacial fractures to date in the United States. Moving forward, there should be a conscious effort among the adult population to reduce the frequency of predictors of panfacial fractures in the pediatric population. Specifically, there must be special attention given to safety precautions when occupying a motor vehicle.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Ali, K.; Lettieri, S.C. Management of Panfacial Fracture. Semin Plast Surg. 2017, 31, 108–117. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, T.L.; Xue, A.S.; Maricevich, R.S. Differences in the Management of Pediatric Facial Trauma. Semin Plast Surg. 2017, 31, 118–122. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Imahara, S.D.; Hopper, R.A.; Wang, J.; Rivara, F.P.; Klein, M.B. Patterns and outcomes of pediatric facial fractures in the United States: a survey of the National Trauma Data Bank. J Am Coll Surg. 2008, 207, 710–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vyas, R.M.; Dickinson, B.P.; Wasson, K.L.; Roostaeian, J.; Bradley, J.P. Pediatric facial fractures: current national incidence, distribution, and health care resource use. J Craniofac Surg. 2008, 19, 339–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamamoto, K.; Matsusue, Y.; Horita, S.; Murakami, K.; Sugiura, T.; Kirita, T. Maxillofacial fractures in children. J Craniofac Surg. 2013, 24, 153–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fonseca, R.J. Oral & maxillofacial trauma. 4th ed. St. Louis, Mo: Saunders; 2013.

- Montovani, J.C.; de Campos, L.M.; Gomes, M.A.; de Moraes, V.R.; Ferreira, F.D.; Nogueira, E.A. Etiology and incidence facial fractures in children and adults. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2006, 72, 235–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- KID Database Documentation; 2021. Accessed www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/db/nation/kid/kiddbdocumentation.jsp.

- Grunwaldt, L.; Smith, D.M.; Zuckerbraun, N.S.; et al. Pediatric facial fractures: demographics, injury patterns, and associated injuries in 772 consecutive patients. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011, 128, 1263–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalena, M.M.; Liu, F.C.; Halsey, J.N.; Lee, E.S.; Granick, M.S. Assessment of Panfacial Fractures in the Pediatric Population. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2020, 78, 1156–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, F.K.; Adams, S.; Coates, T.J.; Hudson, D.A. Pediatric Facial Fractures. J Craniofac Surg. 2016, 27, 128–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, P.C.; Barbosa, J.; Braga, J.M.; Rodrigues, A.; Silva, A.C.; Amarante, J.M. Pediatric Facial Fractures: A Review of 2071 Fractures. Ann Plast Surg. 2016, 77, 54–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moffitt, J.K.; Wainwright, D.J.; Bartz-Kurycki, M.; et al. Factors associated with surgical management for pediatric facial fractures at a level one trauma center. J Craniofac Surg. 2019, 30, 854–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sherick, D.G.; Buchman, S.R.; Patel, P.P. Pediatric facial fractures: a demographic analysis outside an urban environment. Ann Plast Surg. 1997, 38, 578–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Posnick, J.C.; Wells, M.; Pron, G.E. Pediatric facial fractures: evolving patterns of treatment. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1993, 51, 836–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alcala-Galiano, A.; Arribas-Garcia, I.J.; Martin-Perez, M.A.; Romance, A.; Montalvo-Moreno, J.J.; Juncos, J.M. Pediatric facial fractures: children are not just small adults. Radiographics. 2008, 28, 441–461 quiz 618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- HRSA. National Survey of Children’s Health (NSCH); 2018. https://mchb.hrsa.gov/data-research/national-survey- childrens-health. Accessed December 15, 2021.

- Erdmann, D.; Follmar, K.E.; Debruijn, M.; et al. A retrospective analysis of facial fracture etiologies. Ann Plast Surg. 2008, 60, 398–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdelrahman, T.; Abdelmaaboud, A.; Hamody, A. Challenge and management outcome of panfacial fractures in Sohag University hospital, Egypt. Int Surg J. 2018, 5, 126–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D. A clinical study of panfacial fractures. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1999, 28, 41. [Google Scholar]

- NHTSA. Motorcycle Safety. https://www.nhtsa.gov/road- safety/motorcycles. Accessed November 28, 2021.

© 2022 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the AO Foundation. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).