Does Cardiopulmonary Bypass Affect Outcomes in Nephrectomy with Level III/IV Caval Thrombectomy for Renal Cell Carcinoma?

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

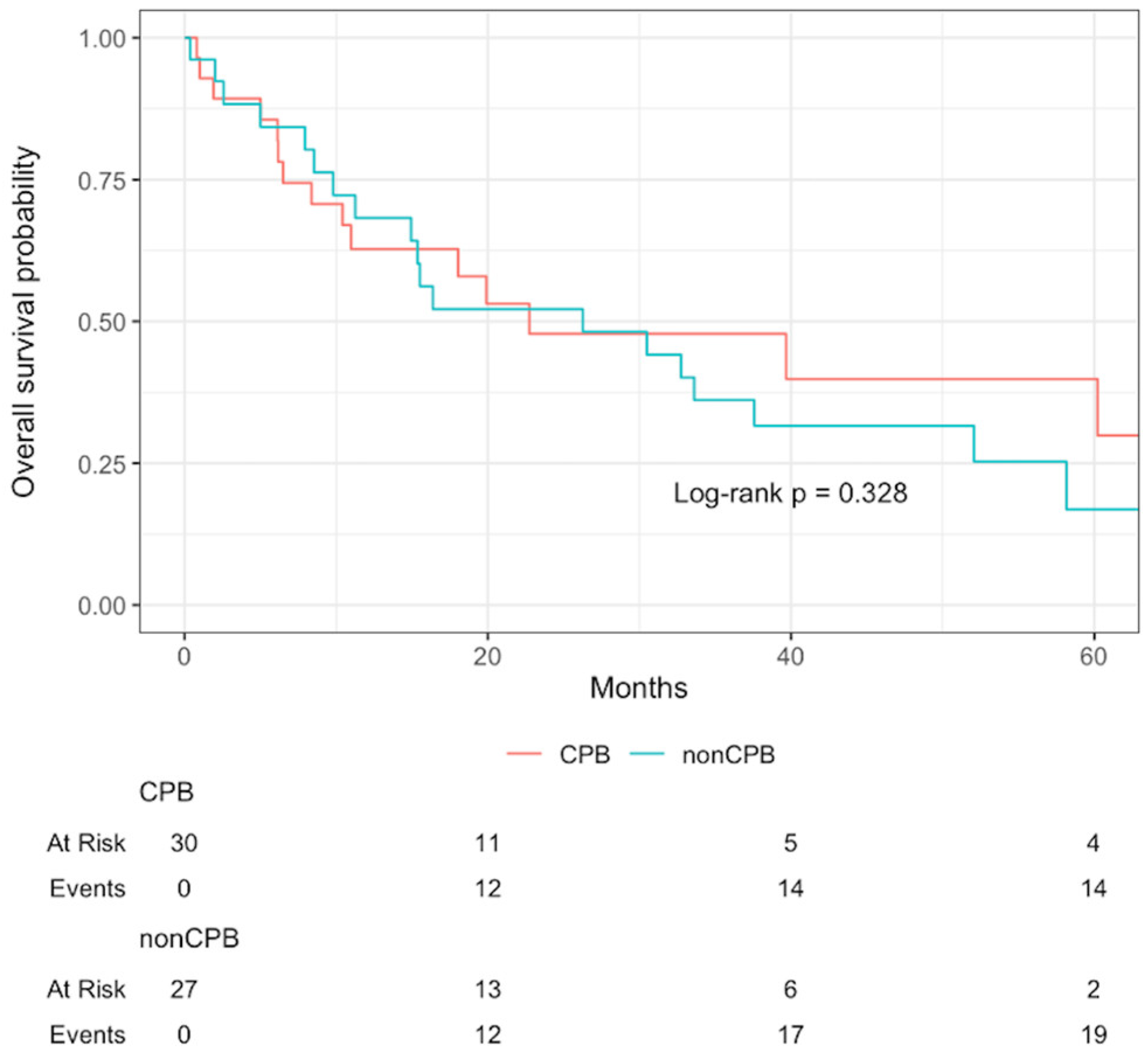

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| CCI | Charlson Comorbidity Index |

| CPB | Cardiopulmonary Bypass |

| IVC | Inferior Vena Cava |

| HR | Hazard Ratio, OR: Odds Ratio |

| RCC | Renal Cell Carcinoma |

| SVC | Superior Vena Cava |

References

- Martínez-Salamanca, J.I.; Huang, W.C.; Millán, I.; Bertini, R.; Bianco, F.J.; Carballido, J.A.; Ciancio, G.; Hernández, C.; Herranz, F.; Haferkamp, A.; et al. Prognostic impact of the 2009 UICC/AJCC TNM staging system for renal cell carcinoma with venous extension. Eur. Urol. 2011, 59, 120–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reese, A.C.; Whitson, J.M.; Meng, M.V. Natural history of untreated renal cell carcinoma with venous tumor thrombus. Urol. Oncol. Semin. Orig. Investig. 2013, 31, 1305–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciancio, G.; Manoharan, M.; Katkoori, D.; De Los Santos, R.; Soloway, M.S. Long-term survival in patients undergoing radical nephrectomy and inferior vena cava thrombectomy: Single-center experience. Eur. Urol. 2010, 57, 667–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almatari, A.L.; Sathe, A.; Wideman, L.; Dewan, C.A.; Vaughan, J.P.; Bennie, I.C.; Buscarini, M. Renal cell carcinoma with tumor thrombus: A review of relevant anatomy and surgical techniques for the general urologist. Urol. Oncol. Semin. Orig. Investig. 2023, 41, 153–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suk-Ouichai, C.; Huang, M.M.; Neill, C.; Mehta, C.K.; Ross, A.E.; Kundu, S.D.; Perry, K.T., Jr.; Pham, D.T.; Patel, H.D. Utilization of cardiopulmonary bypass at radical nephrectomy for renal cell carcinoma with tumour thrombus. BJUI Compass 2025, 6, e460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuch, B.; Crispen, P.L.; Leibovich, B.C.; Larochelle, J.C.; Pouliot, F.; Pantuck, A.J.; Liu, W.; Crepel, M.; Schuckman, A.; Rigaud, J.; et al. Cardiopulmonary bypass and renal cell carcinoma with level IV tumour thrombus: Can deep hypothermic circulatory arrest limit perioperative mortality? BJU Int. 2011, 107, 724–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elahi, M.M.; Khan, J.S.; Matata, B.M. Deleterious effects of cardiopulmonary bypass in coronary artery surgery and scientific interpretation of off-pump’s logic. Acute Card. Care 2006, 8, 196–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.G.; Tilki, D.; Dall’Era, M.A.; Durbin-Johnson, B.; Carballido, J.A.; Chandrasekar, T.; Chromecki, T.; Ciancio, G.; Daneshmand, S.; Gontero, P.; et al. Cardiopulmonary Bypass has No Significant Impact on Survival in Patients Undergoing Nephrectomy and Level III–IV Inferior Vena Cava Thrombectomy: Multi-Institutional Analysis. J. Urol. 2015, 194, 304–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciancio, G.; Shirodkar, S.P.; Soloway, M.S.; Livingstone, A.S.; Barron, M.; Salerno, T.A. Renal Carcinoma with Supradiaphragmatic Tumor Thrombus: Avoiding Sternotomy and Cardiopulmonary Bypass. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2010, 89, 505–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, M.B.; Montez, J.; Loh-Doyle, J.; Cai, J.; Skinner, E.C.; Schuckman, A.; Thangathurai, D.; Skinner, D.G.; Daneshmand, S. Level III–IV inferior vena caval thrombectomy without cardiopulmonary bypass: Long-term experience with intrapericardial control. J. Urol. 2014, 192, 682–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorin, M.A.; González, J.; Garcia-Roig, M.; Ciancio, G. Transplantation techniques for the resection of renal cell carcinoma with tumor thrombus: A technical description and review. Urol. Oncol. Semin. Orig. Investig. 2013, 31, 1780–1787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neves, R.J.; Zincke, H. Surgical treatment of renal cancer with vena cava extension. Br. J. Urol. 1987, 59, 390–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dindo, D.; Demartines, N.; Clavien, P.A. Classification of surgical complications: A new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann. Surg. 2004, 240, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simon, R.M.; Kim, T.; Espiritu, P.; Kurian, T.; Sexton, W.J.; Pow-Sang, J.M.; Sverrisson, E.; Spiess, P.E. Effect of utilization of veno-venous bypass vs. cardiopulmonary bypass on complications for high level inferior vena cava tumor thrombectomy and concomitant radical nephrectomy. Int. Braz. J. Urol. 2015, 41, 911–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granberg, C.F.; Boorjian, S.A.; Schaff, H.V.; Orszulak, T.A.; Leibovich, B.C.; Lohse, C.M.; Cheville, J.C.; Blute, M.L. Surgical management, complications, and outcome of radical nephrectomy with inferior vena cava tumor thrombectomy facilitated by vascular bypass. Urology 2008, 72, 148–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; Zhao, G.; Chen, Y.; Wu, P.; Li, S.; Peng, C.; Liu, K.; Yu, H.; Gao, Y.; Xiao, C.; et al. Robotic Level IV Inferior Vena Cava Thrombectomy Using an Intrapericardial Control Technique: Is It Safe Without Cardiopulmonary Bypass? J. Urol. 2023, 209, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abel, E.J.; Thompson, R.H.; Margulis, V.; Heckman, J.E.; Merril, M.M.; Darwish, O.M.; Krabbe, L.M.; Boorjian, S.A.; Leibovich, B.C.; Wood, C.G. Perioperative outcomes following surgical resection of renal cell carcinoma with inferior vena cava thrombus extending above the hepatic veins: A contemporary multicenter experience. Eur. Urol. 2014, 66, 584–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nini, A.; Capitanio, U.; Larcher, A.; Dell’Oglio, P.; Dehò, F.; Suardi, N.; Muttin, F.; Carenzi, C.; Freschi, M.; Lucianò, R.; et al. Perioperative and Oncologic Outcomes of Nephrectomy and Caval Thrombectomy Using Extracorporeal Circulation and Deep Hypothermic Circulatory Arrest for Renal Cell Carcinoma Invading the Supradiaphragmatic Inferior Vena Cava and/or Right Atrium. Eur. Urol. 2018, 73, 793–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casey, R.G.; Raheem, O.A.; Elmusharaf, E.; Madhavan, P.; Tolan, M.; Lynch, T.H. Renal cell carcinoma with IVC and atrial thrombus: A single centre’s 10 year surgical experience. Surgeon 2013, 11, 295–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddad, A.Q.; Leibovich, B.C.; Abel, E.J.; Luo, J.-H.; Krabbe, L.-M.; Thompson, R.H.; Heckman, J.E.; Merrill, M.M.; Gayed, B.A.; Sagalowsky, A.I.; et al. Preoperative multivariable prognostic models for prediction of survival and major complications following surgical resection of renal cell carcinoma with suprahepatic caval tumor thrombus. Urol. Oncol. Semin. Orig. Investig. 2015, 33, 388.e1–388.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, X.; Huang, J.; Yao, X.; Qian, H.; Zhang, J.; Kong, W.; Wu, X.; Huang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Xue, W. Cognitive Function After Cardiopulmonary Bypass and Deep Hypothermic Circulatory Arrest in Management of Renal Cell Carcinoma with Vena Caval Thrombus. Urology 2022, 167, 144–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ripoll, J.G.; Bittner, E.A.; Zaremba, S.; Nabzdyk, C.S.; Seelhammer, T.G.; Wieruszewski, P.M.; Chang, M.G.; Ramakrishna, H. Analysis of 2024 EACTS/EACTAIC/EBCP Guidelines on Cardiopulmonary Bypass in Adult Cardiac Surgery. J. Cardiothorac. Vasc. Anesthesia 2025, 39, 1853–1865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabbara, M.M.; González, J.; Ciancio, G. The surgical evolution of radical nephrectomy and tumor thrombectomy: A narrative review. Ann. Transl. Med. 2023, 11, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowal, P.; Ratajczyk, K.; Bursiewicz, W.; Trzciniecki, M.; Marek-Bukowiec, K.; Rogala, J.; Kowalskyi, V.; Dragasek, J.; Botikova, A.; Kruzliak, P.; et al. Differentiation of solid and friable tumour thrombus in patients with renal cell carcinoma: The role of MRI apparent diffusion coefficient. Adv. Med. Sci. 2024, 69, 434–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khene, Z.E.; Bhanvadia, R.; Tachibana, I.; Issa, W.; Graber, W.; Trevino, I.; Woldu, S.L.; Gaston, K.; Zafar, A.; Hammers, H.; et al. Surgical Outcomes of Radical Nephrectomy and Inferior Vena Cava Thrombectomy Following Preoperative Systemic Immunotherapy: A Propensity Score Analysis. Clin. Genitourin. Cancer 2025, 23, 102307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freifeld, Y.; Woldu, S.L.; Singla, N.; Clinton, T.; Bagrodia, A.; Hutchinson, R.; Lotan, Y.; Margulis, V. Impact of Hospital Case Volume on Outcomes Following Radical Nephrectomy and Inferior Vena Cava Thrombectomy. Eur. Urol. Oncol. 2019, 2, 691–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| CPB (n = 30) | Non-CPB(n = 27) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (median [IQR]) | 64 [59, 67] | 66 [61, 71] | 0.1 |

| Sex = Male, n (%) | 18 (60.0) | 20 (74.1) | 0.399 |

| BMI (kg/m2) (median [IQR]) | 29.3 [25.5, 32.2] | 27.9 [25.5, 30.9] | 0.532 |

| Preop Hemoglobin (g/dL), (median [IQR]) | 9.9 [8.8, 12.4] | 11.6 [9.8, 12.7] | 0.127 |

| Preop Creatinine (mg/dL), (median [IQR]) | 1.20 [1.02, 1.30] | 1.30 [1.10, 1.90] | 0.339 |

| Smoking (current/former), n (%) | 18 (60) | 18 (67) | 0.806 |

| CCI, n (%) | |||

| 0 | 22 (73) | 12 (44) | 0.033 |

| ≥1 | 8 (27) | 15 (56) | |

| Laterality, n (%) | |||

| Left | 12 (40) | 9 (33) | 0.806 |

| Right | 18 (60) | 18 (67) | |

| Thrombus Level, n (%) | |||

| 3 | 9 (30) | 27 (100) | <0.001 |

| 4 | 21 (70) | 0 (0) | |

| Metastasis, n (%) | 10 (33) | 7 (26) | 0.749 |

| Preop Angioembolization, n (%) | 8 (27) | 6 (22) | 0.935 |

| Year of surgery, n (%) | |||

| 2000–2011 | 6 (20) | 13 (48) | 0.049 |

| 2012–2023 | 24 (80) | 14 (52) |

| CPB (n = 30) | Non-CPB (n = 27) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Operative time (min), (median [IQR]) | 466 [386, 512] | 317 [271, 405] | <0.001 |

| Intraop Transfusion (mL), (median [IQR]) * | 2300 [1300, 3400] | 1400 [0, 2863] | 0.193 |

| Pathologic size (cm), (median [IQR]) | 12.0 [10.0, 13.8] | 10.6 [7.6, 15.0] | 0.397 |

| Pathologic T stage, n (%) | |||

| T3 | 28 (93) | 24 (89) | 0.902 |

| T4 | 2 (7) | 3 (11) | |

| Pathologic N stage, n (%) | |||

| N0/Nx | 23 (77) | 24 (89) | 0.388 |

| N1 | 7 (23) | 3 (11) | |

| 90-day post-op complications | 15 (50) | 13 (48) | 1 |

| Low (Clavien 1–2) | 8 (53) | 7 (54) | |

| High (Clavien 3–4) | 7 (47) | 6 (46) | |

| LOS (days), (median [IQR]) | 8.5 [7.0, 13.0] | 8.0 [6.0, 10.5] | 0.193 |

| 90-day mortality, n (%) | 3 (10) | 3 (11) | 1 |

| HR | 95% CI | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| CPB | |||

| No | - | - | |

| Yes | 1.34 | 0.65, 2.78 | 0.41 |

| Pre-op Hgb (g/dL) | 0.88 | 0.75, 1.05 | 0.17 |

| Metastasis | 2.31 | 1.05, 4.93 | 0.038 |

| pTstage | |||

| T3 | - | - | |

| T4 | 2.5 | 0.83, 7.54 | 0.1 |

| Pre-op sCr (mg/dL) | 1.38 | 0.99, 1.83 | 0.54 |

| OR | 95% CI | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| CPB | |||

| No | - | - | |

| Yes | 0.55 | 0.13, 2.12 | 0.4 |

| Operative Time | 1.01 | 1.0001, 1.01 | 0.030 |

| Pre-operative Creatinine | 1.59 | 0.86, 4.77 | 0.14 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dudinec, J.V.; Ghoreifi, A.; Refugia, J.; Deivasigamani, S.; Ivey, M.; Hunter, A.E.; Moghaddam, F.S.; Benkert, A.R.; Fantony, J.J.; Williams, A.R.; et al. Does Cardiopulmonary Bypass Affect Outcomes in Nephrectomy with Level III/IV Caval Thrombectomy for Renal Cell Carcinoma? Curr. Oncol. 2025, 32, 671. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32120671

Dudinec JV, Ghoreifi A, Refugia J, Deivasigamani S, Ivey M, Hunter AE, Moghaddam FS, Benkert AR, Fantony JJ, Williams AR, et al. Does Cardiopulmonary Bypass Affect Outcomes in Nephrectomy with Level III/IV Caval Thrombectomy for Renal Cell Carcinoma? Current Oncology. 2025; 32(12):671. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32120671

Chicago/Turabian StyleDudinec, John V., Alireza Ghoreifi, Justin Refugia, Sriram Deivasigamani, Michael Ivey, Alexandra E. Hunter, Farshad S. Moghaddam, Abigail R. Benkert, Joseph J. Fantony, Adam R. Williams, and et al. 2025. "Does Cardiopulmonary Bypass Affect Outcomes in Nephrectomy with Level III/IV Caval Thrombectomy for Renal Cell Carcinoma?" Current Oncology 32, no. 12: 671. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32120671

APA StyleDudinec, J. V., Ghoreifi, A., Refugia, J., Deivasigamani, S., Ivey, M., Hunter, A. E., Moghaddam, F. S., Benkert, A. R., Fantony, J. J., Williams, A. R., Shah, A., & Abern, M. R. (2025). Does Cardiopulmonary Bypass Affect Outcomes in Nephrectomy with Level III/IV Caval Thrombectomy for Renal Cell Carcinoma? Current Oncology, 32(12), 671. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32120671