Abstract

Coronary angiography is the gold standard for diagnosis of coronary artery disease. Though it is a relatively safe procedure, complications can occur. We present an unusual case of a dehisced radio opaque ring from the diagnostic angiography catheter into the left circumflex artery. It was successfully retrieved with a guidewire and a balloon catheter and revascularization was done in the same setting.

Introduction

Coronary angiography is a relatively safe procedure. Though coronary catheter fractures have been reported before, the exact incidence during diagnostic angiography is unknown. We present a case, wherein the radio opaque tip of the diagnostic angiography catheter broke of and embolized into the left circumflex coronary artery (LCX). It was successfully retrieved and revascularization was completed in the same setting.

Case report

A 45-year-old diabetic male presented with history of typical effort angina of six months duration. His resting electrocardiogram and echocardiogram were normal. As the stress test was positive for inducible ischemia at a work load of 7 METS, he was taken for selective coronary angiography.

A 7F, Judkins left (JL) 3.5 diagnostic catheter (Cordis Corp., Miami Lakes, Florida) was selected to cannulate the left coronary artery through a 8F femoral sheath. This catheter had been used before and was sterilized using ethylene oxide. Before the first shoot could be taken a radio opaque object was seen within the LCX artery (Figure 1A). It appeared to be the broken soft tip of the diagnostic catheter. Immediately the catheter was withdrawn and examined. The soft ring on the tip of the catheter was found missing.

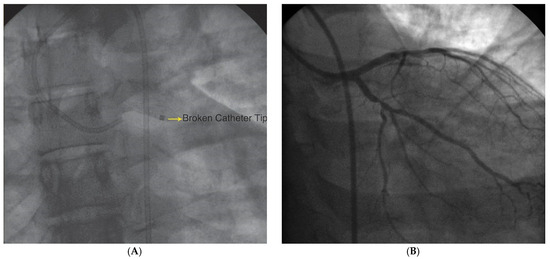

Figure 1.

(A) Cine film demonstrating the broken radio opaque tip of the diagnostic catheter that has embolized to the left circumflex coronary artery. (B) Coronary angiogram showing an 80% stenosis in the left circumflex artery proximal to the origin of obtuse marginal artery. Distal embolization of the broken catheter tip was prevented by this stenosis.

An 8F, JL 3.5 guiding catheter (Cordis Corp., Miami Lakes, Florida) was introduced into the left coronary artery. The detached tip of the diagnostic catheter was seen sitting in the LCX artery, proximal to a tight lesion (Figure 1B). A 0.014” floppy guidewire (Abbott Vascular, Santa Clara, California) was manipulated to go through the catheter tip and positioned in the distal LCX artery (Figure 2A). A 2.0 × 10 mm Sprinter balloon (Medtronic, Inc., Minneapolis, Minnesota) was advanced over the guidewire through the lumen of the broken catheter tip. There was no distal migration of the catheter tip during the introduction of balloon into LCX artery. The balloon was kept distal to the catheter tip and was inflated to 2 atm (Figure 2B). An attempt was made to pull back the balloon with the broken piece into the guiding catheter. It was getting stuck at the tip of the guide catheter. Hence the guiding catheter was pulled out along with the inflated balloon, guidewire and the catheter tip as an assembly.

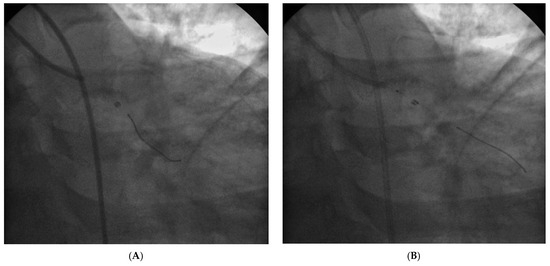

Figure 2.

(A) A 0.014″ floppy wire is being introduced into the circumflex artery, such that it passes through the lumen of the dehisced catheter. (B) A 2.0 x 10 mm Sprinter balloon being positioned across the broken catheter and is inflated to 2 atmospheres.

Diagnostic angiogram done after retrieval, showed 80% lesion in the proximal LCX and insignificant left anterior descending artery disease. The right coronary artery was normal. The LCX lesion was crossed with a floppy guidewire and a 2.75 × 15 mm bare metal stent was deployed at 12 atmospheres. The final angiogram showed no residual lesion, thrombus or dissection (Figure 3). There was no elevation in the level cardiac biomarkers post procedure. Patient was discharged on the 3rd day and is asymptomatic at one year follow up.

Figure 3.

Angiogram done after angioplasty and stenting of the circumflex coronary artery showing no residual stenosis, dissection or thrombosis.

Discussion

The components retained in the coronary tree include twisted/dehisced catheter tips [1,2,3] broken guidewire [4], entrapped balloons and undeployed stents [5]. Most of these complications occur during PTCA and stenting, as the procedure involves excessive manipulation and traction forces during various stages of the procedure. The incidence of broken retained PCI equipments is 0.1–0.8% [6]. Though there are several reports of fractured angioplasty guidewires, fracture of coronary catheters is extremely uncommon and only few case reports exists [7,8,9]. The factors contributing to fracture of catheters include excessive torquing, forceful withdrawal of catheter which is entrapped in arterial spasm, inappropriate handling of catheters, reuse, manufacturing flaws, inadvertent passage of large catheter through smaller sized access site sheaths, polymer aging or a combination of factors could lead to fracture of diagnostic angiography catheter tip [10]. In our case utilization of ethylene oxide sterilized catheter could have caused the fracture.

As the broken tip in the coronary artery might serve as nidus for thrombus formation, acute occlusion, myocardial infarction and arrhythmias, removal of the broken fragment is mandatory. Transcatheter removal is the most appealing and least invasive treatment option. Devices used for intra-coronary retrieval includes snares, cardiac bioptome and balloon catheter [1].

In our case a balloon catheter was used to retrieve the broken catheter tip. It was possible for two reasons, namely the broken tip of the catheter was seated coaxially so that the guidewire could be passed through it easily and there was a tight lesion in the proximal LCX artery, which prevented the downward slipping of the catheter tip during balloon advancement. Another factor that enabled successful retrieval is the adequately sized guiding catheter. Trying to retrieve a broken catheter which is not coaxial, by this technique increases the chance of coronary dissection and perforation. Snares and bioptomes can be used alternatively to remove such fragments, but adds to the procedural costs. The twin guidewire technique described by Gurley et al. may also be effective in retrieving the foreign body. Trehan et al. had described retrieval of broken balloon catheter along with its shaft by inflating another balloon within lumen of guiding catheter so that the broken shaft is anchored between the inflated balloon and guiding catheter. The report described by us is different in the sense we retrieved a broken diagnostic catheter tip by passing a guidewire through the broken fragment and anchoring it with inflated balloon [11].

Surgery should be used, when percutaneous retrieval fails. As there is a possibility of angiographically invisible dissection at the site of catheter manipulation, revascularization should be done when required in the same setting.

Conclusion

Fracture of diagnostic angiography catheter with embolization to coronary artery is a rare complication of coronary angiography. The etiology of such catheter fracture is multifactorial. When diagnostic catheter fractures, it can be retrieved from coronary circulation using an appropriately sized balloon catheter. It is preferable to perform revascularization of underlying coronary artery disease in the same sitting.

Funding/Potential Competing Interests

No financial support and no other potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

- Chen, Y.; Fang, C.C.; Yu, C.L.; Jao, Y.T.; Wang, S.P. Intracoronary retrieval of the dehisced radiopaque ring of a guiding catheter: an unusual complication of coronary angioplasty. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2002, 55, 262–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosario, P.G.; Donahoo, J.S. Coronary artery endarterectomy for retrieval of entrapped percutaneous angioplasty catheter. Ann Thorac Surg. 1996, 61, 218–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Ghamry Sabe, A.A.; Ettinger, S.M. Retrieval of directional coronary atherectomy guiding catheter with angioplasty balloon catheter. Cathet Cardiovasc Diagn. 1995, 35, 237–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, P.K.; Alber, G.; Schistek, R.; Unger, F. Rupture of guide during percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1989, 97, 467–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rozenman, Y.; Burstein, M.; Hasin, Y.; Gotsman, M.S. Retrieval of occluding unexpanded Palmaz-Schatz stent from a saphenous aorto-coronary vein graft. Cathet Cardiovasc Diagn. 1995, 34, 159–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartzler, G.O.; Rutherford, B.D.; McConahay, D.R. Retained percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty equipment components a nd their management. Am J Cardiol. 1987, 60, 1260–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reddy, C.V.; Khan, R.; Feit, A.; Gordon, D.; El Sherif, N. Catheter separation during coronary angiography. Cathet Cardiovasc Diagn. 1983, 9, 417–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kyriakides, Z.S.; Bellenis, I.P.; Caralis, D.G. Catheter separation during cardiac catheterization and coronary angiography. A report of four incidents and review of the literature. Angiology 1986, 37, 762–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazicioglu, D.L.; Kaya, D.K.; Aral, D.A.; Ozyurda, D.ü. Surgical removal of entrapped broken coronary angioplasty catheter in left main and circumflex coronary artery. Gulhane Med J. 2003, 45, 361–362. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, R.M.; Fornes, R.E.; Stuckey, W.C.; Gilbert, R.D.; Peter, R.H. Fracture of a polyurethane cardiac catheter in the aortic arch: a complication related to polymer aging. Cathet Cardiovasc Diagn. 1983, 9, 197–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trehan, V.; Mukhopadhyay, S.; Yusuf, J.; CRamgasetty, U.; Mukherjee, S.; Arora, R. Intracoronary fracture and embolization of a coronary angioplasty balloon catheter: retrieval by a simple technique. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2003, 58, 473–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2011 by the author. Attribution - Non-Commercial - NoDerivatives 4.0.